1. Introduction

The operation of buildings is an extremely

energy-consuming process, constituting around 40% of the world-produced energy [1]. Most of the operational energy demand (around

75%) is influenced by the thermal performance of the building envelope. i.e.,

summer heat gain and winter heat loss [2]. The

fully glazed facades, in this respect, neither meet the requirement of energy

efficiency nor sustainability [3]. Studies [4–6] have shown that fully glazed façades consume

up to 60% more energy for heating, cooling, and lighting than buildings with

the optimal window-to-wall ratio.

A vertical greening systems (VGS), including green

walls and living walls, offers a more sustainable, energy-efficient, and

biophilic solution for the building envelope. Several studies have demonstrated

that the VGS may not only increase the energy efficiency of buildings [7,8] but also sequester carbon dioxide [9], act as an air filter capturing small

particulate matter [10], and contribute to the

physiological health and well-being of residents [11].

Unfortunately, the existing VGS (e.g., hydroponic

felt-based or pre-vegetated modular panel systems) are extremely expensive,

with average installation costs of 750 EUR/m2 [12]. As a result, practical applications of living

walls are scarce, except for specific luxury projects. To simplify the

installation of VGS and reduce maintenance costs, an alternative idea has been

introduced: growing microorganisms and lowering plants directly on a concrete

surface [13,14]. Such biological growth on

concrete is analogous to the organisms found in the cryptogramic ground covers

(CGC) and cryptogramic plant covers (CPC): bacteria, fungi, algae, lichens, and

non-vascular plants (bryophytes; liverworts, hornworts, mosses) [15]. These photoautotrophic communities can fix

atmospheric CO2 and N2, producing carbon and

nitrogen-containing organic compounds. Cryptogamic covers were estimated to

correspond to 7% of net primary carbon and almost 50% of nitrogen uptake by

terrestrial vegetation [16]. Thus, the

extension of cryptogamic covers on the building envelope would transform the

city landscape into a more natural environment and contribute to global carbon

and nitrogen sequestration.

The life-sustaining concrete must possess a

specific aptitude to be colonized by living organisms without undergoing

bio-deterioration, also called bioreceptivity [17].

Most natural building materials, such as bricks, stones, timber, or concrete,

possess certain primary or secondary bioreceptivity [18,19].

The primary bioreceptivity is characteristic of the surface with the initial

mechanical, physical, and chemical properties. The exposed surface is affected

by environmental and biological actions and gradually acquires secondary

bioreceptivity [20]. While most of the new

concrete structures show imperceptible biological growth, the weathered,

carbonated, and leached concrete may host life for bacteria and even lower

plants [21]. Despite the numerous benefits and

potential impact on the sustainability of buildings, only a few studies have

explored the practical applicability of bioreceptive concrete in façades [22–24]. Most concrete bioreceptivity studies were

limited only to laboratory tests using single-species model microorganisms [25–32]. Although the accelerated laboratory tests

may give a quick tentative bioreceptivity property of the material, the

real-world biological colonization, driven by the volatile environmental and

functional interplay between multiple species, may be significantly different [33,34]. A few field studies did not prove that the

bioreceptive concrete is capable of forming attractive, visible growth

patterns, either with the quick degradation of laboratory-developed biofilm [23] or no visible growth of microorganisms [35].

The Present study aims to analyze the biological

growth on concrete in the terrestrial environment, highlighting the limitations

of the currently performed research on concrete bioreceptivity. We also report

interim field test results on long-term biological colonization of Layered

Living Concrete (LLC) panels. By demonstrating concrete's relatively quick and

controlled greening, we advocate the broader use of bioreceptive materials in

the building envelope. Such nature-integrated solutions would emphasize the

aging buildings' beauty while offering clear, practical benefits and

aesthetically pleasant looks.

2. Biological Growth on Concrete

Externally exposed concrete surfaces offer an

extremely abiotic terrestrial environment with minimal water and nutrients,

quick water evaporation, and intense UV radiation. In addition, subaerial

mineral substrates are constantly subjected to rapid temperature, moisture

level, and relative humidity changes. Therefore, only specific stress-tolerant

microorganisms may colonize the mineral-based substrates by scavenging

nutrients from the atmosphere and rainwater, using residues of plants, dust, or

waste products of other microbes [36].

Typically, the phototrophic carbon and

nitrogen-fixing species (such as Cyanobacteria and Green algae)

are pioneering microorganisms that begin the colonization of concrete surfaces [37,38]. At first, gravity- or advection-driven

cells attach to the hard surface, initiating the first stage of biological

colonization [39] (Figure 1A). These autotrophic microorganisms

are capable of converting inorganic carbon (atmospheric CO2) into

organic, biologically available carbon or molecular dinitrogen (atmospheric N2)

into ammonia (NH3) [40,41]. Then,

the attached cells produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), mostly

composed of microbial biopolymers (proteins, exopolysaccharides, nucleic acids,

and lipids) [42]. The EPS reinforces the cell

adhesion to the substrate via hydrogen bonding and protects the microbial

community from toxic compounds (e.g., bactericides) [43,44].

As a result, a highly structured biofilm starts to form, in which the cells

encase themselves into the self-produced EPS matrix [43].

Besides the binding and protective functions, EPS serves as energy and carbon

sinks for the cells and acts as a water retention and communication tool [45]. Once the adhesive-protective EPS coating is

established, it eases the colonization of other microorganisms and further

production of EPS.

Figure 1.

Representation of possible mechanisms involved in biological colonization of concrete surface. At Stage 1 (

A), gravity-driven phototrophic bacteria start to form initial biofilms and irreversibly attach to the concrete surface. At favorable environmental conditions (Stage 2), the fungal biofilms start to develop, which may also be accompanied by the growth of lichens (

B). At Stage 3, the accumulated deposits of atmospheric dust, small particulate matter, and organic carbon from the dead microorganism cells allow for the growth of first plants, typically bryophytes (

C). Adopted from [

36,

38,

69,

70,

71]. Not to scale.

Figure 1.

Representation of possible mechanisms involved in biological colonization of concrete surface. At Stage 1 (

A), gravity-driven phototrophic bacteria start to form initial biofilms and irreversibly attach to the concrete surface. At favorable environmental conditions (Stage 2), the fungal biofilms start to develop, which may also be accompanied by the growth of lichens (

B). At Stage 3, the accumulated deposits of atmospheric dust, small particulate matter, and organic carbon from the dead microorganism cells allow for the growth of first plants, typically bryophytes (

C). Adopted from [

36,

38,

69,

70,

71]. Not to scale.

The single species may initiate the formation of

biofilm. Due to the relative simplicity and ease of control, single-species

biofilms are mostly studied under laboratory conditions [41,43,46]. Contrarily, in the natural environment,

self-sustaining microbial communities form a complex patchy biofilm containing

different autotrophic and heterotrophic bacteria, algae, fungi, and lichens [37,47]. These microorganisms commonly form

mutualistic interactions between autotrophs and heterotrophs, allowing for an

efficient exchange of nutrients, functional interplay, and increased survival

capability. As such, phototrophic microorganisms are commonly distributed at

the upper biofilm layers, collecting the sun's energy and shieling the

heterotrophic microorganisms at the bottom layers [48].

The neighboring heterotrophic species recycle the photorespiration byproducts,

thus effectively increasing the biomass of the phototroph-heterotroph

consortium [42]. A complex interplay between

the different bacterial species was demonstrated in [49].

A full nitrogen cycle was observed on the relatively small-scale stone-based

subaerial biofilm (SUB) with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (that convert

molecular nitrogen N2 into ammonia NH3), nitrifying

bacteria (converting ammonia NH3 into the nitrite NO2-

and then to nitrate NO3-) as well as denitrifying

bacteria, that close the nitrogen cycle (turning nitrogen oxides back to

nitrogen gas N2). Lichens, a symbiosis of phototrophic algae (or

cyanobacteria), heterotrophic fungi, and bacteria are another prominent example

of mutualistic interactions [38]. The

phototropic partner in such symbiosis produces the organic energy via carbon

dioxide fixation, whereas the fungal partner offers the sheltering structures

and sustains the moisture level [50].

Generally, the naturally growing biofilms form complex, highly stratified,

self-organized structures where collectively organized species improve the

ability to acquire nutrients from the environment and increase survivability

under extreme conditions [42].

Villa et al. [37]

suggested a trait-based approach for the life-history analysis of sub-aerial

biofilms (SUBs) in analogy to vascular plants' survival and colonization

strategies. The underlying idea was to separate microorganisms into three

groups according to their metabolic activity rate, survival strategy, and

response to disturbance: (1) competitors, (2) stress tolerators, and (3)

ruderals. Competitors are adapted to quickly consume available resources and

engage in long-term site occupation. Hyphomycetes and Microcolonial

fungi are typical competitors in the subaerial biofilms. Stress tolerators,

such as Green algae and Cyanobacteria, have high resource-use

efficiency and can survive in a harsh environment (temperature fluctuations, UV

radiation, low moisture levels). Finally, ruderals can produce a copious amount

of low-cost biomass and quickly colonize a new surface after a major disturbance

(such as fire, drought, or storm). Actinobacteria was classified as a

typical ruderal microorganism in a subaerial biofilm.

The microbiological composition of the SUB strongly

depends on the dominant bacteria life strategy (competition, stress-toleration,

or ruderal colonization), which, in turn, is governed by environmental

conditions. For example, slow-growing, stress-tolerant species such as Cyanobacteria

and Green algae will dominate in areas likely to face prolonged

stresses (constant UV radiation with limited precipitation). The predominance

of algal biofilms is a typical scenario in hot and warm-summer Mediterranean

climate zones (Csa and Csb, according to Köppen climate classification), where

green bio-patina is commonly found on building facades and stone monuments [46,47]. Contrarily, competitor microorganisms

dominate with the extensive development of fungi and lichens in humid

continental and tropical climate zones [51,52].

As shown in Fig. 1B, the development of

fungi-dominated biofilms denotes the second stage of biological colonization.

At this stage, fungal hyphae penetrate microcracks and open concrete pores,

commonly forming stable layers of mineral crust (mostly carbonates, phosphates,

oxides, and oxalates [36]). At favorable

environmental conditions, the growth of fungal biofilms may be accompanied by

the development of lichens. Similarly to bacterial phototroph-heterotroph

consortiums, lichens may store nutrients from the surrounding environment and

resist extreme environmental conditions [38]

(prolonged periods of drought, intense UV radiation, and temperature

fluctuations). Lichens actively affect the concrete substrate by penetrating

the open pores and surface cracks, producing organic carboxylic acids, and

initiating various bio-mineralization pathways [36,38].

As a result, a stable layer of biological crust may form on the concrete

surface that may have both bio-deteriorative and bio-protective effects [53,54].

The matured bacterial-fungi-lichen crust

accumulates atmospheric dust, small particulate matter, decaying plants, and

animal feces. In addition, dead cells of bacteria and fungi enrich the crust

with organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus [52].

These deposits serve as an initial substrate suitable for the first pioneer

plants [38], thus starting the third stage of

biological colonization (Fig. 1C). Most commonly, nonvascular spore-forming

bryophytes (typically mosses) are the first plants that can survive on the

concrete surface [55]. Mosses do not have

roots and attach themselves to the surface using rhizoids. Remarkably, mosses

are poikilohydric plants, meaning water status completely depends on their

environment [56]. As such, mosses can tolerate

desiccation and resume their metabolism after rewetting. In addition, some moss

species can transport atmospheric nitrogen to the soil by forming a mutualistic

relationship with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria [57,58].

Such unique features make mosses a promising plant for bioreceptive and living

concrete walls [59–61]. The next Section will

discuss a broader perspective on the potentiality of mosses in urban

ecosystems.

3. Laboratory and Field Testing of Concrete Bioreceptivity

Due to concrete's complex and relatively slow

biological colonization, simplified and accelerated laboratory tests are

commonly employed for bioreceptivity evaluation [62].

An overview of the studies related to the bioreceptivity testing of concrete is

presented in Table 1. Most commonly,

biological growth is stimulated by inoculating a single species of

microorganisms [25–32]. Using this approach,

biological growth may be strictly controlled by applying suitable nutrients and

imposing the required temperature, humidity, and UV radiation [47]. Studying the growth of individual community

members is in sharp contrast to the formation of natural SUB. The natural

formation of multiple species biofilms is driven by the external environment,

which provides nutrients, moisture, space, and physical and chemical stressors [41]. As such, complex and highly stratified

biological structures form on the surface of concrete, where different species

enhance the survivability rate by mutualistic relationships and functional

interlay.

The laboratory studies of a single species biofilm

formation have another inherent deficiency: it may instead show the ability of

the studied microorganism to colonize the concrete surface rather than the

aptitude of concrete to be colonized [47]. For

example, a broad experimental program on concrete bioreceptivity using Chlorella

vulgaris model organisms was reported in [27].

The accelerated laboratory algal fouling tests have shown that specimens

produced with magnesium phosphate cement (MPC) had a noticeably higher

percentage of fouling area than ordinary Portland cement specimens (OPC). It

was concluded that due to lower pH and more suitable chemical composition,

MPC-based specimens had a higher bioreceptivity [27,33].

Nevertheless, when the specimens of the same concrete mix composition were

tested in the natural environment, no visible growth was found on any specimens

[35]. The previously used Chlorella

vulgaris model organism was not even detected on the concrete surface.

Similarly, Tran et al. [34] argued that the

experimental conditions of accelerated tests are far different from the real

ones. It was shown that concrete's initial surface pH, porosity, and roughness

have much less correlation with biological colonization in field exposure in

comparison to the accelerated laboratory tests [34].

These examples support the statement that the ability of the specific

microorganism to grow under laboratory conditions does not necessarily impose

that the material has the aptitude to be colonized in the natural environment.

After experimenting with the bioreceptive façade

panels, Veeger et al. [23] highlighted another

issue with the laboratory-developed biofilm. The algal biofilm showed a stable

development and quick greening of horizontally placed façade panels under

optimal growing conditions: panels were kept in water with the waterline just

below the concrete surface, at constant room temperature, 90% humidity, and 12h

cycle artificial lighting. However, biofilm completely lost its integrity after

the real-world exposure, with only slight recovery signs after 5 months of

field testing. The authors argued that such quick disruption of

laboratory-developed biofilm may be attributed to the lack of EPS, which helps

to mediate the extreme environmental actions. As the laboratory specimens were

kept under constant and favorable conditions, the cell energy was directed to

the production of biomass rather than EPS [23].

Based on these observations, specific cultivation-adaptation regimes are being

tested for the bioreceptive concrete façade panels [21].

To summarize, accelerated laboratory tests may give

the material a quick tentative bioreceptivity property. The real-world

biological colonization, driven by the volatile environmental and functional

interplay between multiple species, may differ significantly. Even though field

tests are generally labor-intensive, prolonged, and hardly controllable, the

gathered knowledge on biofilm formation may provide invaluable data on the

long-term survivability and aesthetical view of colonized concrete, which is

especially relevant in building facades. The next section provides insights

into the natural concrete colonization of existing buildings and reports on the

current status of our long-term test results on the development of

bio-receptive façade panels.

Table 1.

Bioreceptivity studies of concrete*.

Table 1.

Bioreceptivity studies of concrete*.

| Reference |

Organisms |

Duration |

Test set-up |

Main results |

|

| [27] |

Green algae: Chlorella vulgaris

|

10 - 17 weeks (depending on the specimen) |

The accelerated algal fouling test, using modular water run-off. Algal cultures were sprayed on 45° inclined concrete panels every 12h for 90 min. |

After 4 weeks of testing, visual algal biofilm formed on both Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) and Magnesium phosphate cement (MPC) specimens. The MPC specimens had a noticeably higher percentage of fouling area. It was concluded that MPC-based specimens were the most suitable for stimulating colonization of Chlorella vulgaris in laboratory conditions. |

|

| [23] |

Existing algal biofilm from the exterior wall |

20 weeks |

After inoculation, prototype façade panels were kept horizontally in the distilled water bath with a water line just below the concrete surface. |

Under optimal growing conditions, a biofilm developed on the panels within two weeks. However, the biofilm quickly degraded after exposure to the natural environment. After five months of field exposure, no visible regrowth of biofilm was observed. |

|

| [28] |

Existing algal biofilm from the exterior walldata |

8 weeks |

Concrete samples (50x50x30mm) were biofouled by adding drops of the liquid biofilm using a pipette. After inoculation, the samples were placed in a container with distilled water. |

Concrete samples that contained bone ash (a source of phosphorus) demonstrated enhanced bioreceptivity. Similarly, a positive effect on bioreceptivity was observed when the crushed expanded clay particles changed the coarse aggregate. |

|

| [30] |

Green algae: Chlorophyceae and Cyanophyceae

|

14 weeks |

Concrete specimens (50x50x10 mm) were tilted at 45° in a polycarbonate transparent chamber. Water pumps intermittently applied a water-algae mixture (1h or 3h/day) to the surface of the specimens. |

The growth areas of algae became visible after 5-6 weeks, whereas full algal coverage was obtained after 14 weeks. It was concluded that the W/C ratio (and consequently, the porosity of the specimens) appeared to be an essential parameter only for short-term algal colonization. In the long term, concrete composition (specifically the W/C ratio) had a minor role in biological colonization. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| [31] |

Fungus:

Alternaria, Cladosporium, Epicoccum, Fusarium, Mucor, Penicillium, Pestalotiopsis, Trichoderma

|

1 week |

Sterile concrete samples (60x60x4 mm) were placed into incubation chambers and inoculated with 100 μl aliquots of each fungal isolate. A liquid nutrient solution was sprinkled over 6-h on/off time intervals. |

The growth of fungi resulted in robust fouling that ranged in color from green to dark grey. Adding fly ash, slag, silica fume, or metakaolin did not significantly affect biofouling. Similarly, surface roughness also had a minor influence on the fungal growth. It was hypothesized that fungal isolates may initially colonize and foul concrete structures by using rainwater and form-release oil as a nutrient source. |

|

| [32] |

Green algae: Chlorella vulgaris

|

12 weeks |

A water run-off modular setup was used. Concrete specimens (10×80×160 mm) were placed in a wooden frame with a 45° inclination angle. Algal cultures were circularly sprayed on the specimens by means of sprinkling rail and aquarium pump (every 12 h, for 90 min) |

It was found that the surface treatment's performance depended on the bioreceptivity of the concrete. As such, most of the tested concrete mixtures developed an algal biofilm within the time frame of this research, even those treated with biocides or water repellents. The study has shown that an algal biofilm may develop on most cementitious materials under favorable conditions. |

|

| [35] |

Four bacterial and 12 fungal genera were identified from the environmental samples |

1 year |

Vertically and horizontally oriented bioreceptive concrete samples (80×80×20 mm) were kept in the natural environment in different locations: Barcelona city, Natural Park of Montseny (60 km from Barcelona), and Ghent city in Belgium. |

All specimens contained bacterial and fungal microorganisms. Ghent presented a higher biodiversity and number of fungi than the other two locations. However, the Specimens did not show any visual colonization, indicating that environmental conditions have a greater impact on biological colonization than intrinsic material properties. |

data |

data |

data |

|

| [34] |

Green algae: Klebsormidium,

flaccidum

|

Laboratory tests – 8 weeks

Field tests –

1.5 years |

Laboratory specimens (80×20×10 mm) were tested under a run-off set-up, placing them in the incubation chambers and periodically (90 min every 12 h) sprinkling them with algal suspension. Field specimens were kept at a 45° inclination angle, facing north. Only natural inoculation was involved in field conditions. |

Concrete porosity had no significant effect on fouling intensity in the laboratory conditions. However, field tests have shown that high porosity favors biological colonization. The results of field testing showed no impact on initial carbonization. Biological colonization started 11-12 months after exposure for all field-tested specimens. After such a period, concrete aged and weathered by leaching and natural carbonation. Consequentially, similar surface pH was detected in both carbonated and uncarbonated specimens (pH = 8). |

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion: Potentiality of Bioreceptive Concrete in Building Facades

The natural colonization of concrete surfaces is a long-term process. The aesthetical appearance of a SUB on a building facade is controlled by the material intrinsic parameters (bioreceptivity) and the environmental conditions. North-faced, commonly wet facades with rough texture show rapid signs of colonization, whereas south-facing smooth concrete façades may show no signs of biological fouling for decades. As was shown in

Section 2, the colonization starts with the irreversible attachment of autotrophic bacteria. The initial biological activity of the autotrophic bacteria commonly does not result in the development of significant biomass and discoloration of the surface [

35]. Only at colonization stage 2, with the more intense development of fungi or algae, the first signs of visible discoloration occur [

31]. In practice, in a favorable growth condition, it takes approximately one year to see the first visible growth and 2-5 years to develop an intense algal cover [

29,

34]. Depending on the dominating microorganisms, the building facades are typically tinted with green (as a result of

Cyanobacteria and

Green-algae dominated biofilms), black-grey (as a result of

fungal domination), or red stains (caused by

Red microalgae) [

63,

64]. The typical discoloration pattern of 9 years north-facing concrete wall in the humid continental climate zone (Vilnius, Lithuania) is presented in Fig. 2. The available moisture principally controls the biological growth on this wall: the top part of the wall collects the water from the horizontal surface, whereas the bottom part primarily obtains the moisture by capillary suction. As a result, well-visible fungal and algal stains have developed, proceeding to the second stage of biological colonization.

It should be noted, however, that such uncontrolled discoloration may negatively impact the visual aesthetics of the façade and provoke a special antibacterial treatment [

52,

65]. Contrarily, the growth of lichens and bryophytes on the walls is generally tolerated and even considered pleasant. The visitor opinion survey on the perception of biological growth on historic buildings in Oxfordshire [

66] has indicated that the majority of the public and experts felt positive about the look of moss growth on historic walls (90% of experts and 77% of visitors agreed with the statement “I enjoy the look of mosses on historic buildings”). Thus, only at the third concrete colonization stage (Fig. 1c) the bioreceptive concrete wall may become tolerable and acceptable by the general public.

Figure 2.

Biological stains on a 9-year-old concrete wall. Black, green, and red discolorations are caused by the biological activity of microalgal and fungal species.

Figure 2.

Biological stains on a 9-year-old concrete wall. Black, green, and red discolorations are caused by the biological activity of microalgal and fungal species.

Although mosses can grow on vertical concrete surfaces, their growth pattern is irregular and mostly concentrated at surface indentations, cracks, and other irregularities. Similarly to algal and fungal biofilms, moss growth can only be observed in water-available regions.

Figure 3 exemplifies the initiation of the third colonization stage in the same 9-year-old concrete wall. As may be noticed, moss mostly grows on the corner regions and can hardly attach to the smooth vertical surface.

Figure 3.

The signs of the third stage of biological colonization on a 9-year-old concrete wall: growth of lichens and mosses starts at the corners, cracks, and surface irregularities.

Figure 3.

The signs of the third stage of biological colonization on a 9-year-old concrete wall: growth of lichens and mosses starts at the corners, cracks, and surface irregularities.

To accelerate the growth of bryophytes on a concrete wall, a Layered Living Concrete (LLC) façade panel system was previously designed by the Author [

67]. The underlying idea was to shorten the time required for the natural growth of mosses from several decades to several years. The LLC panel consists of three main elements: (1) high-performance synthetic fiber reinforced concrete (HPFRC) that ensures the durability and structural integrity of the panel; (2) light-weight pervious concrete (LWPC), that provides rough, bio-receptive, and highly permeable surface ; (3) biological booster (BB), that directly serves as a growing substrate at the initial colonization stages (Fig. 4).

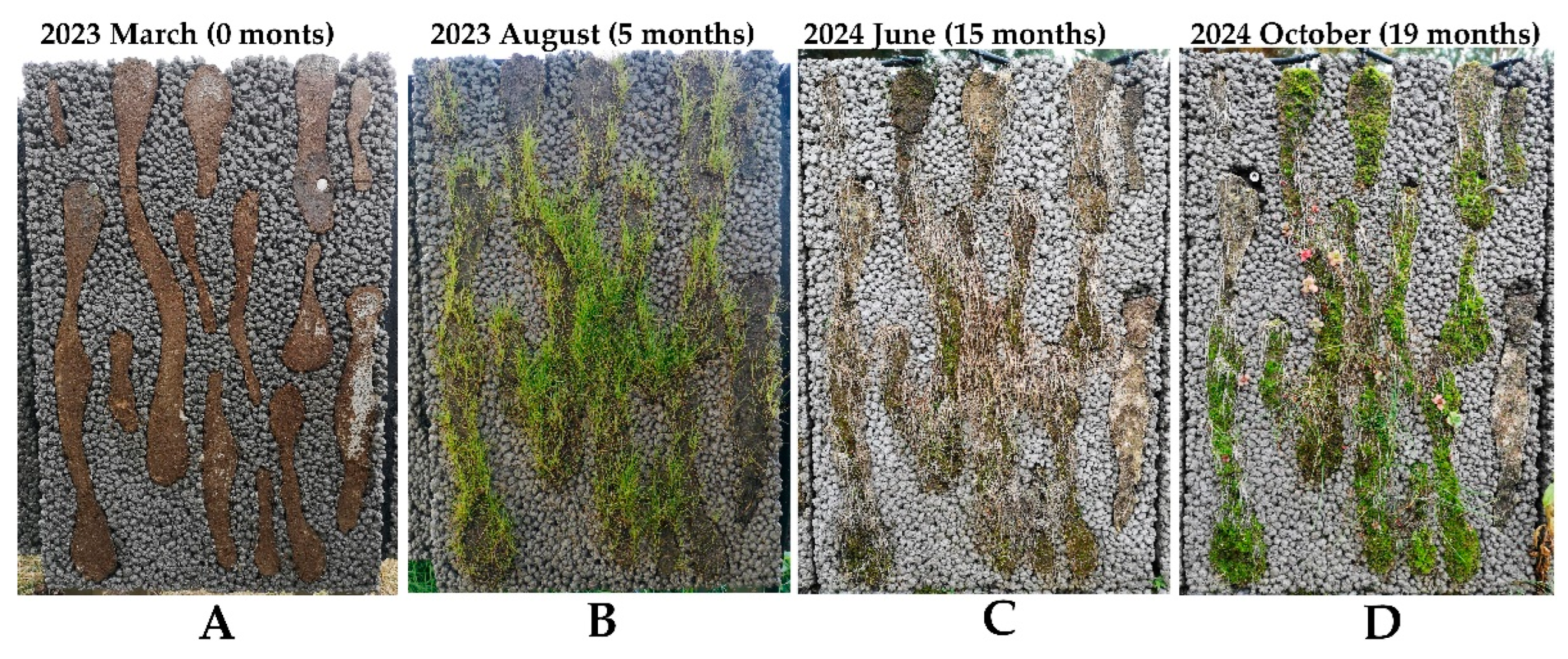

Figure 4.

The composition and biological growth on the Layered Living Concrete (LLC) façade panels: the biological growth on the 5-month-old LLC panels is hardly noticeable (A), whereas well-developed moss can be seen on 19-month-old panels (B).

Figure 4.

The composition and biological growth on the Layered Living Concrete (LLC) façade panels: the biological growth on the 5-month-old LLC panels is hardly noticeable (A), whereas well-developed moss can be seen on 19-month-old panels (B).

The rational composition of all materials, as well as the optimal distribution of biological boosters, is still the subject of ongoing investigations. Our initial results have shown [

67,

68] that the thin-walled panels may be produced when the compressive and residual tensile strength of the HPFRC layer exceeds 100 MPa and 1.5 MPa, respectively. For the uniform distribution of an irrigation water, the infiltration rate of the LWPC layer should exceed 2.5 cm/s. The biological booster, composed of recycled paper pulp and a soil crust, should have at least 50% of the active component (soil crust).

Several long-term experimental campaigns examining the biological growth on the LLC panels are ongoing under natural environmental conditions (Fig. 4). The first test series began in March 2021, with the installation of four 400 × 600 mm differently faced (East-West, North-South) panels. The second series of LLC panel field tests began in April 2023 with 12 additional 400 × 600 mm panels. Finally, the third experimental series started in July 2024, examining the biological growth on 48 LLC panels (300 × 300 mm). Several important insights were gathered from the long-term field observations:

The biological booster allows for a significantly faster greening of concrete surfaces: colonization stage 3 starts several months after panel installation with germination of mosses and fungi (Fig. 5A). We recommend the production of biological boosters from the local soil crust, as it naturally contains indigenous bacteria, spores of mosses, fungi, and lichens. Those species are adapted to the local climate and require only several months of latency.

After two years of field exposure, no visible signs of biological colonization by algal or fungal microorganisms were observed on the pervious concrete surface. This confirms that the natural colonization of concrete is a long-term process, taking several years to several decades [

29]. Regarding the application of bioreceptice concrete in building facades, such a lag between the installation and the visible biological growth may be unacceptable. Thus, a BB may solve this problem by offering a relatively quick growth of mosses (Fig. 5B).

Irrigation water should be supplied for quicker biological growth. In all tested LLC panels, the BB was kept wet, providing water from the drip irrigation system. Although such a living wall may not be considered a self-sustained system, supplied water not only accelerated the growth of mosses but also initiated the development of some vascular plants (mostly sedums). The supplied irrigation water also resulted in a more pleasant appearance of LLC during prolonged drought periods.

During field tests, we attempted to grow some drought-resistance vascular plants (Sedum acre, Sedum spurium, Saxifraga arendsii, Festuca rubra commutata, Festuca trichophytic). Although some vascular plants (Festuca rubra commutata, Festuca trichophytic) showed a quick initial greening, most of them did not survive the first winter (Fig. 6). In the long-term perspective, domination of mosses on all panels was observed.

The BB allows quicker biological colonization and control of the aesthetical appearance of the façade. As such, the BB may be distributed in rhythmic, repetitive, or flowing patterns for both aesthetics and the optimized water retention capacity.

The shape and distribution of BB within the LLC panel are crucial for both anchoring ability and water retention capacity. Fig. 6D shows an example of poor water distribution on the panel: the desiccated and shrank BB at the side edges of the panel could not support the moss growth. Based on the water retention tests and a long term field observations, continuous diagonal shape of BB was proposed for optimal greening performance [

68].

Figure 5.

Biological growth on the LLC: after three months of field exposure the initial growth of fungi and mosses start to be visible on panels of test Series 3 (A) and growth evolution in 6 – 18 months period on panels of test Series 2 (B).

Figure 5.

Biological growth on the LLC: after three months of field exposure the initial growth of fungi and mosses start to be visible on panels of test Series 3 (A) and growth evolution in 6 – 18 months period on panels of test Series 2 (B).

Figure 6.

Growth evolution on a LLC panel of test Series 2: (A) initial view just after panel installation; (B) germination and growth of grasses (Festuca rubra commutata, Festuca trichophylla) five months after panel exposure; (C) desiccation of grasses after the first winter; (D) moss domination 19 months after panel exposure.

Figure 6.

Growth evolution on a LLC panel of test Series 2: (A) initial view just after panel installation; (B) germination and growth of grasses (Festuca rubra commutata, Festuca trichophylla) five months after panel exposure; (C) desiccation of grasses after the first winter; (D) moss domination 19 months after panel exposure.

The ongoing field tests allow us to examine the ability of concrete to host biological growth, changes in the aesthetical appearance, and the durability of concrete façade panels in real time. Although field tests were previously highly prioritized [

34,

35], to the Author’s knowledge, this is one of few ongoing experimental programs on long-term concrete bioreceptivity. By implementing broad experimental programs (currently, 64 LLC panels are being tested), we advocate the broader use of bioreceptive concrete in the building’s envelope. The bioreceptive and living concrete may not only offer a natural-looking cryptogramic cover for buildings but also sequester carbon dioxide, filter air, reduce urban noise, and mitigate the effect of the heat islands. We believe that the gradual replacement of modern fully-glazed facades with natural, more economical, and ecological living concrete panels will enrich the biodiversity in densely populated cities, improve the mental health of residents, and save a considerable part of the building's operational energy.

5. Concluding Remarks

Bioreceptive concrete has the potential to become a nature-inspired alternative to modern glass or aluminum facades. Besides the natural, environmentally controlled aesthetics that closely resemble cryptogamic ground covers, bioreceptive concrete living walls also possess superior thermal, air-cleaning, and noise-reduction performance compared to glass or aluminum facades. In addition, concrete surface microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, algae, lichens, and mosses) can fix atmospheric nitrogen and sequester carbon dioxide.

The current research on concrete bioreceptivity was mainly performed under laboratory conditions, simulating the accelerated colonization of concrete by single-species microorganisms. Such tests may give the material a quick tentative bioreceptivity property; however, the real-world biological colonization, driven by the volatile environmental and functional interplay between multiple species, may be significantly different. Laboratory tests, performed under ideal conditions, may commonly show the ability of the selected microorganism to colonize the concrete rather than the intrinsic property of concrete to be colonized by different microorganisms. Thus, field tests may not only reveal the long-term aesthetical look of the receptive concrete wall but also stimulate the growth of resistant and resilient colonies of microorganisms.

Our ongoing long-term field tests of LLC panels have shown that concrete's visible, controlled greening may be achieved in several years. In contrast, several decades may be required to form the natural biological crust on hard surfaces, like stone monuments or concrete walls. Still, such uncontrolled natural growth may result in irregular discolorations and compromise the structure's aesthetics. By incorporating the biologically active regions in the LLC wall, we stimulate the quick germination and growth of lower plants, control the aesthetic of the wall panel, and facilitate the further colonization of the wall panel by microorganisms.

Incorporating cryptogamic covers for a building envelope renders the central principle of biophilic design: visual connection with nature. As such, bioreceptive concrete has great potential to increase biodiversity in our cities. In addition, by actively participating in the carbon and nitrogen cycles, biologically active cryptogamic covers have the potential to considerably reduce the buildings' environmental impact.

We urgently need more field studies in different climatic regions. The bioreceptive concrete exposed to natural environmental conditions would allow us to examine the long-term survivability of microorganisms and document the changes in the aesthetics of aging concrete. The refined look of naturally developed biofilms may encourage developers and architects to consider the cryptogamic covers for the building envelope.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Azari, R. (2019). Life cycle energy consumption of buildings; embodied+ operational. In Sustainable construction technologies (pp. 123-144). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Venkatraj, V., Dixit, M. K., Yan, W., & Lavy, S. (2020). Evaluating the impact of operating energy reduction measures on embodied energy. Energy and Buildings, 226, 110340. [CrossRef]

- Butera, F. M. (2005). Glass architecture: is it sustainable. Passive and Low Energy Cooling for the Built Environment, 1.

- Aksamija, A., & Peters, T. (2017). Heat transfer in facade systems and energy use: Comparative study of different exterior wall types. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 23(1), C5016002. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, R., Giovanardi, M., Guglielmo, G., & Micono, C. (2017). Embodied energy and operational energy evaluation in tall buildings according to different typologies of façade. Energy Procedia, 134, 224-233. [CrossRef]

- Goia, F. (2016). Search for the optimal window-to-wall ratio in office buildings in different European climates and the implications on total energy saving potential. Solar energy, 132, 467-492. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zheng, B., Shen, W., Xiang, Y., Chen, X., & Qi, Z. (2019). Cooling and energy-saving performance of different green wall design: A simulation study of a block. Energies, 12(15), 2912. [CrossRef]

- Susca, T., Zanghirella, F., Colasuonno, L., & Del Fatto, V. (2022). Effect of green wall installation on urban heat island and building energy use: A climate-informed systematic literature review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 159, 112100. [CrossRef]

- Jozay, M., Zarei, H., Khorasaninejad, S., & Miri, T. (2024). Maximising CO2 Sequestration in the City: The Role of Green Walls in Sustainable Urban Development. Pollutants, 4(1), 91-116. [CrossRef]

- Srbinovska, M., Andova, V., Mateska, A. K., & Krstevska, M. C. (2021). The effect of small green walls on reduction of particulate matter concentration in open areas. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123306. [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, M., Balderrama, A., Arztmann, D., & Pottgiesser, U. (2023). Green walls and health: An umbrella review. Nature-Based Solutions, 3, 100070. [CrossRef]

- Manso, M., Teotónio, I., Silva, C. M., & Cruz, C. O. (2021). Green roof and green wall benefits and costs: A review of the quantitative evidence. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 135, 110111. [CrossRef]

- Manso, S., & Aguado, A. (2016). The use of bio-receptive concrete as a new typology of living wall systems. Matériaux & Techniques, 104(5), 502. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M., & Beckett, R. (2016). Bioreceptive design: A novel approach to biodigital materiality. Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 20(1), 51-64. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. L., Strullu-Derrien, C., Sykes, D., Pressel, S., Duckett, J. G., & Kenrick, P. (2021). Cryptogamic ground covers as analogues for early terrestrial biospheres: Initiation and evolution of biologically mediated proto-soils. Geobiology, 19(3), 292-306. [CrossRef]

- Elbert, W., Weber, B., Burrows, S., Steinkamp, J., Büdel, B., Andreae, M. O., & Pöschl, U. (2012). Contribution of cryptogamic covers to the global cycles of carbon and nitrogen. Nature Geoscience, 5(7), 459-462. [CrossRef]

- Guillitte, O. (1995). Bioreceptivity: a new concept for building ecology studies. Science of the total environment, 167(1-3), 215-220. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Z., Sanmartín, P., Pereira-Pardo, L., Dionísio, A., Sáiz-Jiménez, C., Macedo, M. F., & Prieto, B. (2012). Bioreceptivity of building stones: A review. Science of the total environment, 426, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Perini, K., Castellari, P., Giachetta, A., Turcato, C., & Roccotiello, E. (2020). Experiencing innovative biomaterials for buildings: Potentialities of mosses. Building and Environment, 172, 106708. [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, P., Miller, A. Z., Prieto, B., & Viles, H. A. (2021). Revisiting and reanalysing the concept of bioreceptivity 25 years on. Science of The Total Environment, 770, 145314. [CrossRef]

- Veeger, M., Nabbe, A., Jonkers, H., & Ottelé, M. (2023). Bioreceptive concrete: State of the art and potential benefits. Heron, 68(1), 47-76.

- Cruz, M. (2021). Design for Ageing Buildings: An Applied Research of Poikilohydric Living Walls. In The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Architectural History (pp. 452-468). Routledge.

- Veeger, M., Prieto, A., & Ottelé, M. (2021). Exploring the possibility of using bioreceptive concrete in building façades. Journal of Facade Design and Engineering, 9(1), 73-86.

- Mustafa, K. F., Prieto, A., & Ottele, M. (2021). The role of geometry on a self-sustaining bio-receptive concrete panel for facade application. Sustainability, 13(13), 7453. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J., Tonon, C., Stohl, L., & von Werder, J. (2024). Assessment of concrete bioreceptivity and model organism performance for use in algal biofilm green facade systems. In 11. Jahrestagung des DAfStb mit 63. Forschungskolloquium der BAM-Beiträge zum 63. Forschungskolloquium Green Intelligent Building am 16. und 17. Oktober 2024 (pp. 159-166). Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und-prüfung (BAM).

- Elgaali, H. H., Lopez-Arias, M., & Velay-Lizancos, M. (2024). Accelerated CO2 exposure treatment to enhance bio-receptivity properties of mortars with natural and recycled concrete aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, 449, 138423. [CrossRef]

- Manso, S., De Muynck, W., Segura, I., Aguado, A., Steppe, K., Boon, N., & De Belie, N. (2014). Bioreceptivity evaluation of cementitious materials designed to stimulate biological growth. Science of the Total Environment, 481, 232-241. [CrossRef]

- Veeger, M., Ottelé, M., & Prieto, A. (2021). Making bioreceptive concrete: Formulation and testing of bioreceptive concrete mixtures. Journal of Building Engineering, 44, 102545. [CrossRef]

- Escadeillas, G., Bertron, A., Blanc, P., & Dubosc, A. (2007). Accelerated testing of biological stain growth on external concrete walls. Part 1: Development of the growth tests. Materials and structures, 40, 1061-1071. [CrossRef]

- Escadeillas, G., Bertron, A., Ringot, E., Blanc, P. J., & Dubosc, A. (2009). Accelerated testing of biological stain growth on external concrete walls. Part 2: Quantification of growths. Materials and structures, 42, 937-945. [CrossRef]

- Giannantonio, D. J., Kurth, J. C., Kurtis, K. E., & Sobecky, P. A. (2009). Effects of concrete properties and nutrients on fungal colonization and fouling. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 63(3), 252-259. [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, W., Ramirez, A. M., De Belie, N., & Verstraete, W. (2009). Evaluation of strategies to prevent algal fouling on white architectural and cellular concrete. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 63(6), 679-689.

- Blanco, S. M., de Cea, A. A., Pérez, I. S., & De Belie, N. (2014). Bioreceptivity optimisation of concrete substratum to stimulate biological colonisation (Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya).

- Tran, T. H., Govin, A., Guyonnet, R., Grosseau, P., Lors, C., Damidot, D., ... & Ruot, B. (2014). Influence of the intrinsic characteristics of mortars on their biofouling by pigmented organisms: Comparison between laboratory and field-scale experiments. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 86, 334-342. [CrossRef]

- Manso, S., Calvo-Torras, M. Á., De Belie, N., Segura, I., & Aguado, A. (2015). Evaluation of natural colonisation of cementitious materials: Effect of bioreceptivity and environmental conditions. Science of the Total Environment, 512, 444-453. [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G. M., & Dyer, T. D. (2017). Bioprotection of the built environment and cultural heritage. Microbial biotechnology, 10(5), 1152-1156. [CrossRef]

- Villa, F., Stewart, P. S., Klapper, I., Jacob, J. M., & Cappitelli, F. (2016). Subaerial biofilms on outdoor stone monuments: changing the perspective toward an ecological framework. Bioscience, 66(4), 285-294. [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, A., Adamo, P., Bonanomi, G., & Motti, R. (2022). The role of lichens, mosses, and vascular plants in the biodeterioration of historic buildings: A review. Plants, 11(24), 3429. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, K., Stoodley, P., Goeres, D. M., Hall-Stoodley, L., Burmølle, M., Stewart, P. S., & Bjarnsholt, T. (2022). The biofilm life cycle: expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20(10), 608-620. [CrossRef]

- Tenore, A., Wu, Y., Jacob, J., Bittermann, D., Villa, F., Buttaro, B., & Klapper, I. (2023). Water activity in subaerial microbial biofilms on stone monuments. Science of The Total Environment, 900, 165790. [CrossRef]

- Villa, F., & Cappitelli, F. (2019). The ecology of subaerial biofilms in dry and inhospitable terrestrial environments. Microorganisms, 7(10), 380. [CrossRef]

- Parrilli, E., Tutino, M. L., & Marino, G. (2022). Biofilm as an adaptation strategy to extreme conditions. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali, 33(3), 527-536. [CrossRef]

- Cheah, Y. T., & Chan, D. J. C. (2021). Physiology of microalgal biofilm: a review on prediction of adhesion on substrates. Bioengineered, 12(1), 7577-7599. [CrossRef]

- Moreno Osorio, J. H., Pollio, A., Frunzo, L., Lens, P. N. L., & Esposito, G. (2021). A review of microalgal biofilm technologies: definition, applications, settings and analysis. Frontiers in Chemical Engineering, 3, 737710.

- Kanematsu, H., & Barry, D. M. (2020). Formation and control of biofilm in various environments.

- Fuentes, E., Vázquez-Nion, D., & Prieto, B. (2022). Laboratory development of subaerial biofilms commonly found on buildings. A methodological review. Building and Environment, 223, 109451. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Nion, D., Rodríguez-Castro, J., López-Rodríguez, M. C., Fernández-Silva, I., & Prieto, B. (2016). Subaerial biofilms on granitic historic buildings: microbial diversity and development of phototrophic multi-species cultures. Biofouling, 32(6), 657-669. [CrossRef]

- Morris, P. A., & Brigmon, R. L. (2010, December). Minerals and Microorganisms in Evaporite Environments. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (Vol. 2010, pp. P13B-1379).

- Zanardini, E., May, E., Purdy, K. J., & Murrell, J. C. (2019). Nutrient cycling potential within microbial communities on culturally important stoneworks. Environmental microbiology reports, 11(2), 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Carr, E. C., Harris, S. D., Herr, J. R., & Riekhof, W. R. (2021). Lichens and biofilms: common collective growth imparts similar developmental strategies. Algal Research, 54, 102217. [CrossRef]

- Udawattha, C., Galkanda, H., Ariyarathne, I. S., Jayasinghe, G. Y., & Halwatura, R. (2018). Mold growth and moss growth on tropical walls. Building and Environment, 137, 268-279. [CrossRef]

- Komar, M., Nowicka-Krawczyk, P., Ruman, T., Nizioł, J., Konca, P., & Gutarowska, B. (2022). Metabolomic analysis of photosynthetic biofilms on building façades in temperate climate zones. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 169, 105374. [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, J. P. M., Warke, P. A., & Smith, B. J. (2013). Lichen-induced biomodification of calcareous surfaces: bioprotection versus biodeterioration. Progress in Physical Geography, 37(3), 325-351. [CrossRef]

- Favero-Longo, S. E., & Viles, H. A. (2020). A review of the nature, role and control of lithobionts on stone cultural heritage: Weighing-up and managing biodeterioration and bioprotection. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 36(7), 100. [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, R., Giancola, E., Osman, A., Asawa, T., & Mahmoud, H. (2022). Review of key factors that affect the implementation of bio-receptive façades in a hot arid climate: Case study north Egypt. Building and Environment, 214, 108920. [CrossRef]

- Green, T. G. A., & Lange, O. L. (1995). Photosynthesis in poikilohydric plants: a comparison of lichens and bryophytes. In Ecophysiology of photosynthesis (pp. 319-341). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Calabria, L. M., Petersen, K. S., Bidwell, A., & Hamman, S. T. (2020). Moss-cyanobacteria associations as a novel source of biological N 2-fixation in temperate grasslands. Plant and Soil, 456, 307-321. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., Clasen, L. A., & Rousk, K. (2024). Short-term fate of nitrogen fixed by moss-cyanobacteria associations under different rainfall regimes. Basic and Applied Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Marsaglia, V., Guido, B., & Paoletti, I. (2023). Moss as a multifunctional material for technological greenery systems. THE PLAN JOURNAL, 8, 85-114. [CrossRef]

- Perini, K., Castellari, P., Gisotti, D., Giachetta, A., Turcato, C., & Roccotiello, E. (2022). MosSkin: A moss-based lightweight building system. Building and Environment, 221, 109283. [CrossRef]

- Julinova, P., & Beckovsky, D. (2019). Perspectives of moss species in urban ecosystems and vertical living-architecture: A review. Advances in Engineering Materials, Structures and Systems: Innovations, Mechanics and Applications, 2370-2375.

- Stohl, L., Manninger, T., von Werder, J., Dehn, F., Gorbushina, A., & Meng, B. (2023). Bioreceptivity of concrete: A review. Journal of Building Engineering, 107201. [CrossRef]

- Piontek, M., & Lechów, H. (2018). Biodeterioration Due to Improper Exploitation of External Facades. Civil and Environmental Engineering Reports, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S. (2011). Biological growth on rendered façades. [Doctoral Thesis (compilation), Division of Building Materials]. Lund University, Division of Building Materials.

- Cardellicchio, F., Bufo, S. A., Mang, S. M., Camele, I., Salvi, A. M., & Scrano, L. (2022). The bio-patina on a hypogeum wall of the matera-sassi rupestrian church “San Pietro Barisano” before and after Treatment with Glycoalkaloids. Molecules, 28(1), 330. [CrossRef]

- Jang, K. M. (2020). Moss on Rocks: Evaluating biodeterioration and bioprotection of bryophytic growth on stone masonry (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford).

- Jakubovskis, R., Malaiškienė, J., & Gribniak, V. (2023). Bio-colonization layered concrete panel for greening vertical surfaces: A field study. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 19, e02394. [CrossRef]

- Jakubovskis, R. (2023). Concrete for Living Walls: Current Status and a New Design Recommendation. Buildings, 13(12), 3067. [CrossRef]

- Carr, E. C., Harris, S. D., Herr, J. R., & Riekhof, W. R. (2021). Lichens and biofilms: common collective growth imparts similar developmental strategies. Algal Research, 54, 102217. [CrossRef]

- Morris, P. A., & Brigmon, R. L. (2010, December). Minerals and Microorganisms in Evaporite Environments. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (Vol. 2010, pp. P13B-1379).

- Roldán, M., & Hernández-Mariné, M. (2009). Exploring the secrets of the three-dimensional architecture of phototrophic biofilms in caves. International Journal of Speleology, 38(1), 5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).