1. Introduction

Traditional research-grade electroencephalography (EEG) systems are known for their high temporal resolution, reliability, and multi-channel capabilities. Despite their valuable contributions to neuroscience research, these EEG systems present limitations that hinder broader application and inclusivity [

1]. For instance, the relatively high upfront costs (from around

$10,000 to over

$80,000 for a new research-grade EEG setup) and the need for specialized training restrict access to academic institutions with limited resources. Furthermore, reliance on laboratory-based data collection limits the ecological validity of research findings and poses logistical challenges for participants. The time commitment involved in research participation and the inconvenience of traveling to a research facility can create barriers for potential participants, particularly those from marginalized communities who may face challenges accessing transportation to the research facilities or balancing research participation with other responsibilities. In addition, the design of electrode headsets, most commonly an elastic cap, may inadvertently exclude individuals with diverse hairstyles or cultural practices (e.g., wearing a headscarf or protective hairstyles), raising concerns about equity and representation in EEG research [

1,

2]. These limitations thus highlight the need for EEG systems that are both more accessible and inclusive, enabling real-world data collection from a broader range of participants, especially with the growing interest in utilizing EEG for diverse applications like brain-computer interfaces, neurofeedback, and mobile health monitoring.

The emergence of consumer-grade EEG devices, such as the InteraXon Muse 2, a four-channel EEG headband designed for neurofeedback during mindfulness exercises, has opened new possibilities for brainwave monitoring research. These affordable and portable devices have the potential to democratize research by enabling larger-scale studies, reaching diverse populations, and facilitating data collection in real-world settings [

3]. However, using consumer-grade EEG for event-related potential (ERP) research, a specialized EEG analysis technique that examines neural responses time-locked to specific stimuli [

2], presents unique challenges. Accurately capturing and interpreting these responses with low-cost, non-standard research-grade equipment requires careful consideration. Synchronization of experimental events with the continuous EEG data stream is crucial for ERP analysis, and low-cost systems may lack robust mechanisms for precise marking of stimulus onset. Additionally, ensuring sufficient data quality, including sampling rates and minimizing noise and artifacts, which can be amplified due to less precise electrode placement and fewer channels, is essential for the reliable identification of ERP components.

Despite these challenges, the InteraXon Muse 2 has gained traction within the scientific community due to its compatibility with the Lab Streaming Layer (LSL) protocol [

3,

4]. This open-source system allows for precise synchronization of EEG data with stimulus presentation software like PsychoPy [

5] and other Python-based packages, a crucial step in ERP research. While the Muse has been successfully implemented in various EEG research paradigms, including mindfulness, emotion classification, and substance use [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], its use in ERP research, particularly for language-related components, remains limited. The existing literature has reported successful measurement of large ERP components like the N200 and P300 [

13,

14], which are more consistently elicited across different individuals and paradigms as they can be evoked by relatively simple stimuli and tasks. However, the device’s limited electrode configuration raises concerns about its sensitivity to capture language-related ERP components [

15], which are typically smaller in amplitude and more susceptible to variations in linguistic stimuli and individual differences in language processing [

16]. This limitation is particularly relevant for investigating the N400 component, a key marker of semantic processing [

17].

This study aimed to address this gap in the literature by examining the efficacy of Muse 2 for measuring the N400 component, a negativity occurring between 250 and 600 ms post-word onset, peaking around 400 ms. The amplitude of the N400 is sensitive to the degree of expectation associated with a word in a given; less expected words elicit larger N400 amplitudes, while more expected words elicit smaller ones [

17]. The N400 provides insight into how the brain constructs meaning from language, highlighting its critical role in integrating information and forming expectations. The N400 is the most widely studied ERP component in language research, and it holds potential for clinical applications as a biomarker for a range of learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia [

18]) as well as neurological and psychiatric disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease [

19], Schizophrenia [

20]). To assess the Muse’s capability for capturing the N400 effect, we used a Semantic Relatedness Judgment Task (SRJT) because it is a well-established and reliable paradigm [

21]. In this task, participants read pairs of words and judged their semantic relatedness while EEG data were recorded with the Muse headset. We hypothesized that if the Muse is sufficiently sensitive, target words unrelated to their primes (e.g., “icing-bike”) will elicit a larger N400 response compared to related targets (e.g., “pedal-bike”), consistent with established findings [

21,

22,

23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty-seven first-year college students participated in the study for course credits (see

Table 1 for demographic information). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no reported hearing deficits. This study was approved by the MTSU Institutional Review Board, and written consent was obtained from each participant.

2.2. Stimuli

The task consisted of 112 trials, during which participants viewed 56 related and 56 unrelated word pairs presented in random order. All word pairs used in this experiment were adapted from a previous SRJT study [

23]. Lexical frequency for each word was quantified using log-transformed HAL frequencies obtained from the English Lexicon Project website, which provides norms derived from the HAL corpus [

24]. The log HAL frequency for prime words was 8.70 (SD = 1.94), and for the target words was 10.50 (SD = 1.28). To assess the semantic relatedness between prime and target words, we used the Gensim python library [

25] to access the pre-trained word embedding model “fasttext-wiki-news-subwords-300” [

26] and compute cosine similarity. This model represents words as dense vectors in a 300-dimensional space, capturing semantic relationships based on their co-occurrence patterns in a large text dataset. Cosine similarity, computed between the vector representations of each word pair, ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater similarity. The mean cosine similarity for related word pairs was 0.67 (SD = 0.11) and for unrelated word pairs was 0.30 (SD = 0.08).

2.3. Experimental Procedure

Participants were seated in a quiet room and fitted with a Muse headset. They were allowed to place the headset on themselves or receive assistance from the researcher. The headset’s position was adjusted to optimize the EEG signal quality, which was monitored in real-time using a custom MATLAB [

27] visualizer. Word pairs were presented on a Windows 10 laptop running the open-source software PsychoPy [

5]. The laptop screen was positioned 3 feet from the participant at a visual angle of approximately four degrees. An external monitor connected to the laptop allowed the researcher to monitor the EEG data concurrently. Participants were instructed to judge each word pair’s semantic relatedness and press “R” for related and “U” for unrelated. They first completed eight practice trials. Then, the main task consisted of two blocks of 56 trials, separated by a short break. Each trial began with a prime word displayed for 500 ms, followed by a 500 ms blank screen before the target word presentation. The target word remained on the screen until the participant responded. Two alternative sets of 112 word pairs were created and counterbalanced across participants to ensure that all target words appeared in both the related and unrelated conditions, while preventing any word from being repeated within a participant’s set. The entire experimental session lasted approximately 10 minutes, including the setup of the Muse headset.

2.4. EEG Data Acquisition

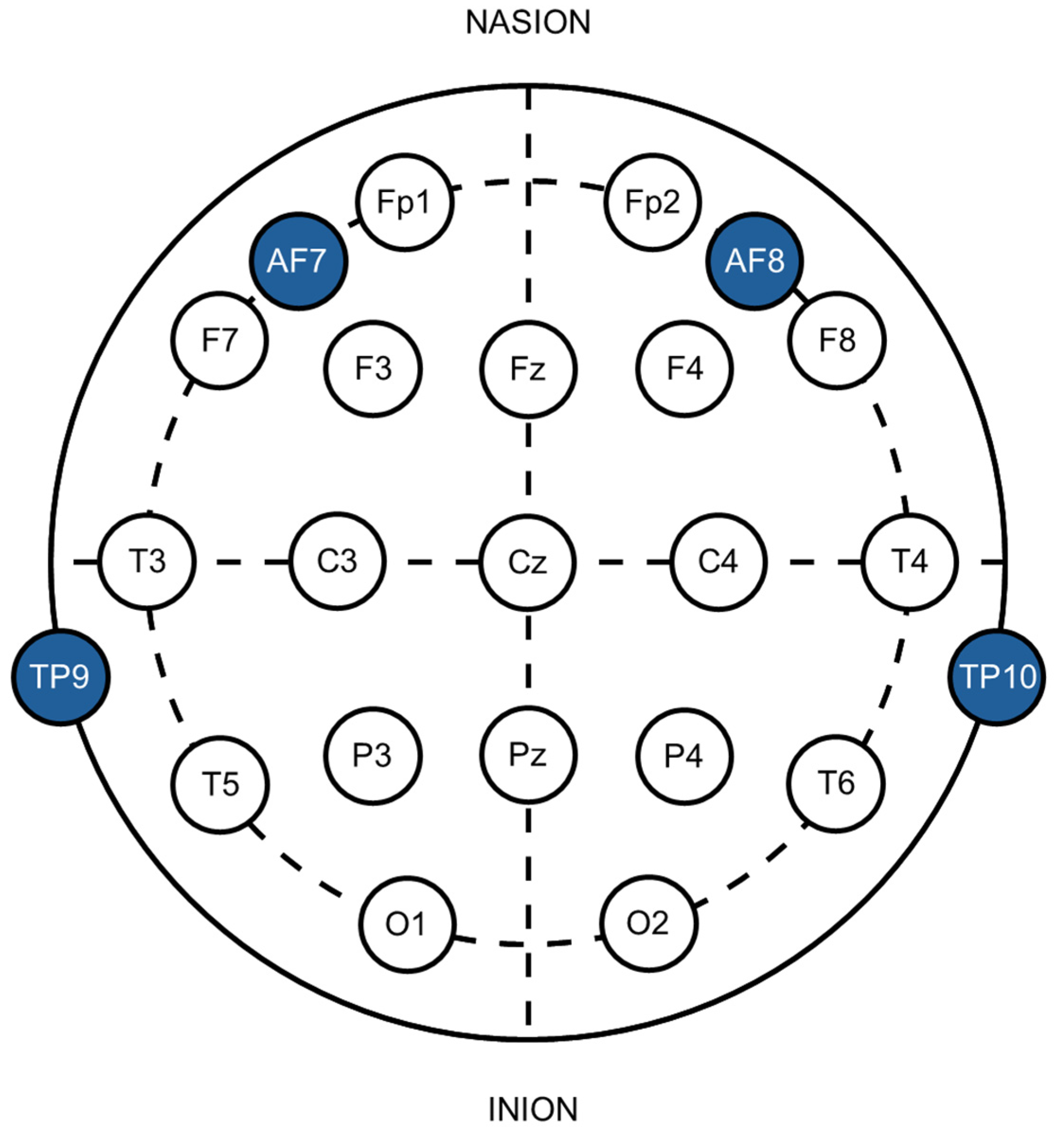

The Muse 2 headband was positioned on the participant’s head, resting across the mid-forehead and fitting over the ears. It includes two sensors located behind the ears (TP9 and TP10), an electrode on each side of the forehead (AF7 and AF8), and a reference electrode situated in the center of the forehead (FPz). These electrode placements correspond to the 10-20 International system [

28] commonly used in wired EEG systems (see

Figure 1). The open-source BlueMuse software linked the Muse to a laptop via Bluetooth [

29] to facilitate connectivity. BlueMuse was also responsible for streaming the raw EEG data using the LSL protocol.

ERP research requires the ability to time-lock precise EEG recordings with stimulus presentation. PsychoPy was selected to present stimuli due to its capacity for streaming LSL timestamp markers and its GUI’s flexibility for incorporating custom Python code. We added code to calculate the exact screen refresh rate, monitor each frame, and send timestamped markers (via LSL) representing the target word onset and condition (Custom codes available on OSF:

https://osf.io/u6y9g/). The incoming LSL data streams from BlueMuse and PsychoPy were then saved into a single time-synchronized Extensible Data Format (XDF) file via LabRecorder (stream capture application included in the LSL ecosystem).

2.5. EEG Data Processing

Data processing was performed in MATLAB [

27] using the EEGLAB toolbox [

30]. The raw EEG signal was high-pass filtered at 0.1 Hz to minimize slow drift and low-pass filtered at 30 Hz to reduce excess noise. N400 studies typically use sensors placed on the mastoids (i.e., part of the skull right behind the ears) as references [

31]. The data was thus re-referenced offline to the average of the two temporoparietal sensors (TP9 and TP10) due to their proximity to the mastoids. EEG epochs were extracted from -100 ms to 900 ms relative to the word onset to analyze single-trial ERPs elicited by the target words. A baseline correction was performed by averaging data from 100 ms to 0 ms pre-onset and subtracting this average from the rest of the time points. Epochs containing extreme values exceeding ±75 µV were rejected. Data from one participant were excluded from further analyses because no epoch survived the rejection threshold in one condition. In line with standard practice in N400 research, only trials with correct responses were included in the final analyses.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Behavioral Data Analysis

Behavioral responses were analyzed to assess participants’ attention to the stimuli and task performance. Accuracy rates, calculated as the proportion of correct responses from the total number of trials per participant, were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a binomial distribution and a logit link function. This approach is suitable for binary data and allows for accurate modeling of accuracy rates. Response times (calculated for correct responses only) were analyzed using a GLMM with a Gamma distribution and a log link function to account for the typically skewed distribution of reaction times and the potential for multiplicative effects of semantic relatedness on processing speed. For both analyses, the fixed effect was condition (related vs. unrelated), and participants were included as a random effect with a random intercept. Statistical analyses were conducted in Jamovi version 2.5 [

32].

2.6.2. ERP Reliability Analysis

To assess the internal consistency of the Muse N400 data, we calculated dependability, the Generalizability theory (G theory) counterpart to reliability. Unlike Classical Test Theory (CTT), G theory provides a framework for evaluating dependability by accounting for various sources of measurement error [

33]. G theory also offers the advantages of accommodating unbalanced data and analyzing nonparallel forms (i.e., those without equal means, variances, and covariances). This acceptance of unbalanced data is particularly beneficial in ERP research, as ERP data is often inherently imbalanced due to the removal of epochs with poor quality during preprocessing [

34].

We used the ERP Reliability Analysis (ERA) Toolbox v0.4.5 [

34] to compute dependability estimates for each experimental condition in the 250-600 ms range, which encompasses the typical latency of the N400 response. Trial cutoffs (the minimum trials needed to include a participant’s data in dependability analyses) were determined at a reliability threshold of 0.70 based on previously established guidelines [

35]. Overall dependability values were then calculated based on these trial cutoffs. Participants with fewer trials than the cutoff for a given condition were excluded from further analysis. To assess the quality of our ERP data, we used the root mean square (RMS) of the standardized measurement error (SME), as recommended by Luck et al. [

36]. The SME for each participant was calculated as the standard deviation of the single-trial mean amplitudes divided by the square root of the number of trials. Subsequently, the RMS of these individual SME values was computed across all participants to obtain the RMS-SME, a global measure of data quality. A lower RMS-SME indicates higher data quality, reflecting less variability in the N400 mean amplitude across the sample.

2.6.3. N400 Effect of Semantic Relatedness

We implemented hierarchical linear modeling with the LIMO EEG plug-in for EEGLAB [

37]. A general linear model was first implemented to estimate the beta parameter representing the effect of the semantically related and semantically unrelated conditions using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to account for within-subject variability across single trials. The within-subject model of each single-trial data at each time point and electrode has the general form Y = β0 + β1X1 + β2X2 + ε with Y the single trial measurement (ie., voltage amplitude), β0 the intercept, β1 and β2 the beta coefficients to be estimated for each experimental condition, X1 and X2 the coding for each column corresponding to the type of stimulus in the design matrix, and ε the error term. Yuen’s robust paired t-tests were computed on the beta estimates at the group level. A non-parametric temporal clustering approach was used to correct for multiple testing, controlling the family-wise error rate at an alpha level of 0.05 [

38]. Null distributions were estimated using a permutation procedure with 1,000 iterations [

38,

39] to derive univariate p-values and cluster-forming thresholds. Cluster-based inference was implemented using a cluster-sum statistic based on squared t-values [

37,

38].

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Data

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for behavioral performance on the Semantic Relatedness Judgment Task. Overall, accuracy rates were high in both the related and unrelated word pair conditions (exceeding 97%), suggesting that participants were attentive and engaged and that the task was a valid measure of semantic processing. The GLMM analysis revealed no significant difference in accuracy rates between the related and unrelated word pair conditions, χ

2 = 1.46, p = 0.22, indicating that the two conditions were equivalent in terms of task difficulty.

A separate GLMM analysis conducted on response times (calculated for correct responses only) revealed a significant difference in response times, χ

2 = 195, p < 0.001, with longer response times observed for semantically unrelated word pairs compared to related pairs (see

Table 2). This finding aligns with prior literature reporting a facilitating effect of semantic relatedness [

40], further supporting the validity of the task developed to test the effectiveness of the Muse headset in measuring the N400.

3.2. EEG Data

3.2.1. Internal Consistency

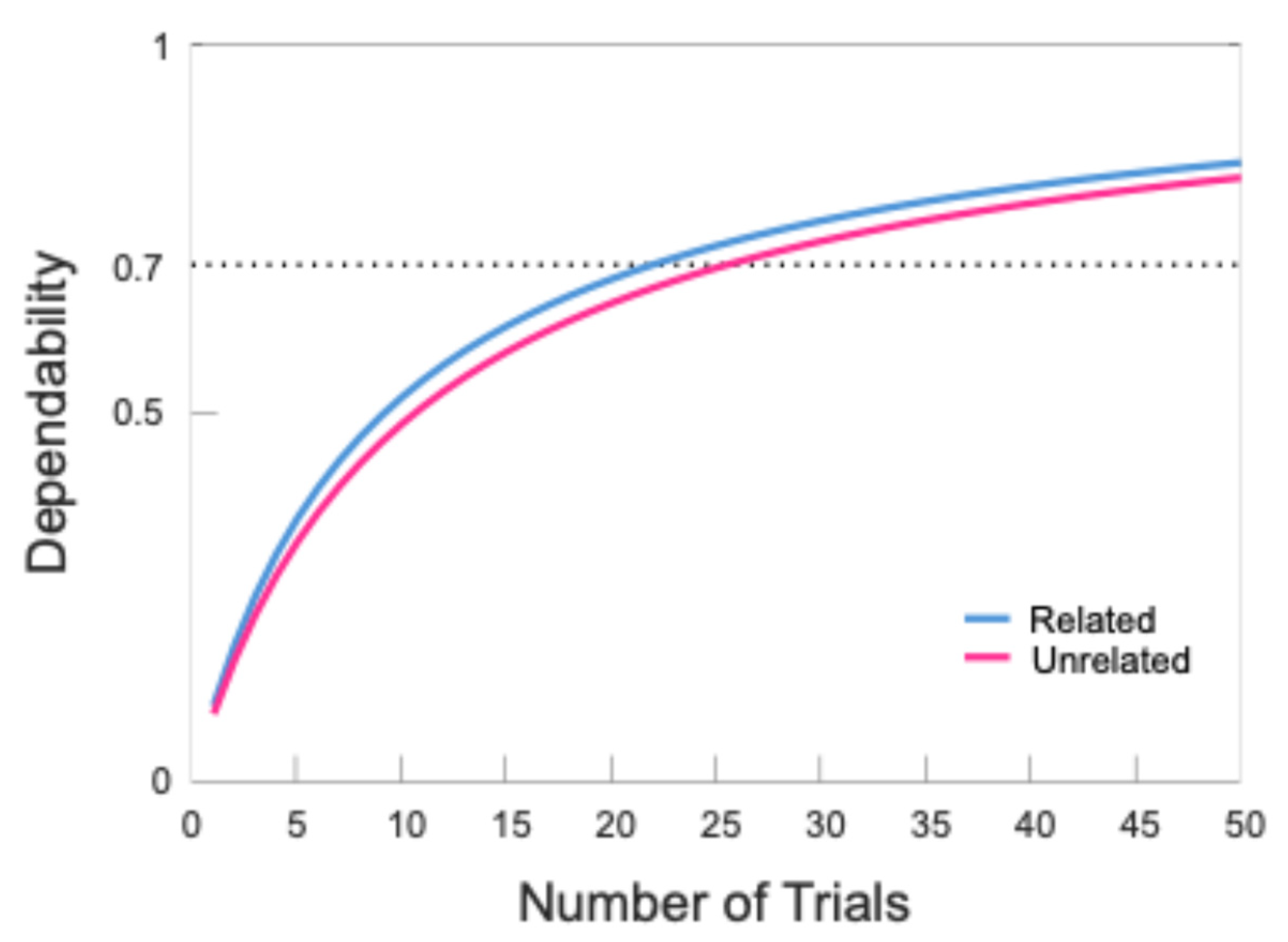

To ensure reliable ERP data, we used the ERA toolbox to determine the number of trials needed to achieve a dependability point estimate of .70, a measure of internal consistency analogous to Cronbach’s alpha. Following the recommendations of Clayson and Miller [

35], we used trial cutoffs derived from dependability analyses to determine participant inclusion. Results indicated that 24 trials were needed for the semantically related condition and 27 trials for the semantically unrelated condition. The data for all but 7 participants met these cutoffs, with an average of 43.17 trials in the semantically related condition and 42.93 trials in the semantically unrelated condition. The overall internal consistency of the included data was high (semantically related = 0.82, semantically unrelated = 0.80).

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the number of trials and the internal consistency of the N400 time window in both the semantically related and unrelated conditions, and

Table 4 shows summary information regarding the number of trials retained for each participant after implementing the cutoffs.

Table 3.

Overall dependability estimates.

Table 3.

Overall dependability estimates.

| Condition |

Threshold |

N |

Dependability |

Trials |

| |

|

Included |

Excluded |

|

M |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Match |

.70 |

29 |

7 |

0.82 CI [0.71 0.90] |

43.17 |

9.04 |

24 |

55 |

| Mismatch |

.70 |

29 |

7 |

0.80 CI [0.67 0.89] |

42.93 |

8.29 |

27 |

54 |

Data quality estimates are presented in

Table 4. The total SD (i.e., SD of the mean amplitude in the 250-600 ms time window across all trials and participants) represents the overall variability in the data, including both true signal and noise, while the SME represents the noise component. When the RMS of the SME is smaller than the total SD, it thus suggests that a significant portion of the observed variability in the data is due to actual differences between conditions rather than just measurement noise.

3.2.2. N400 Analysis

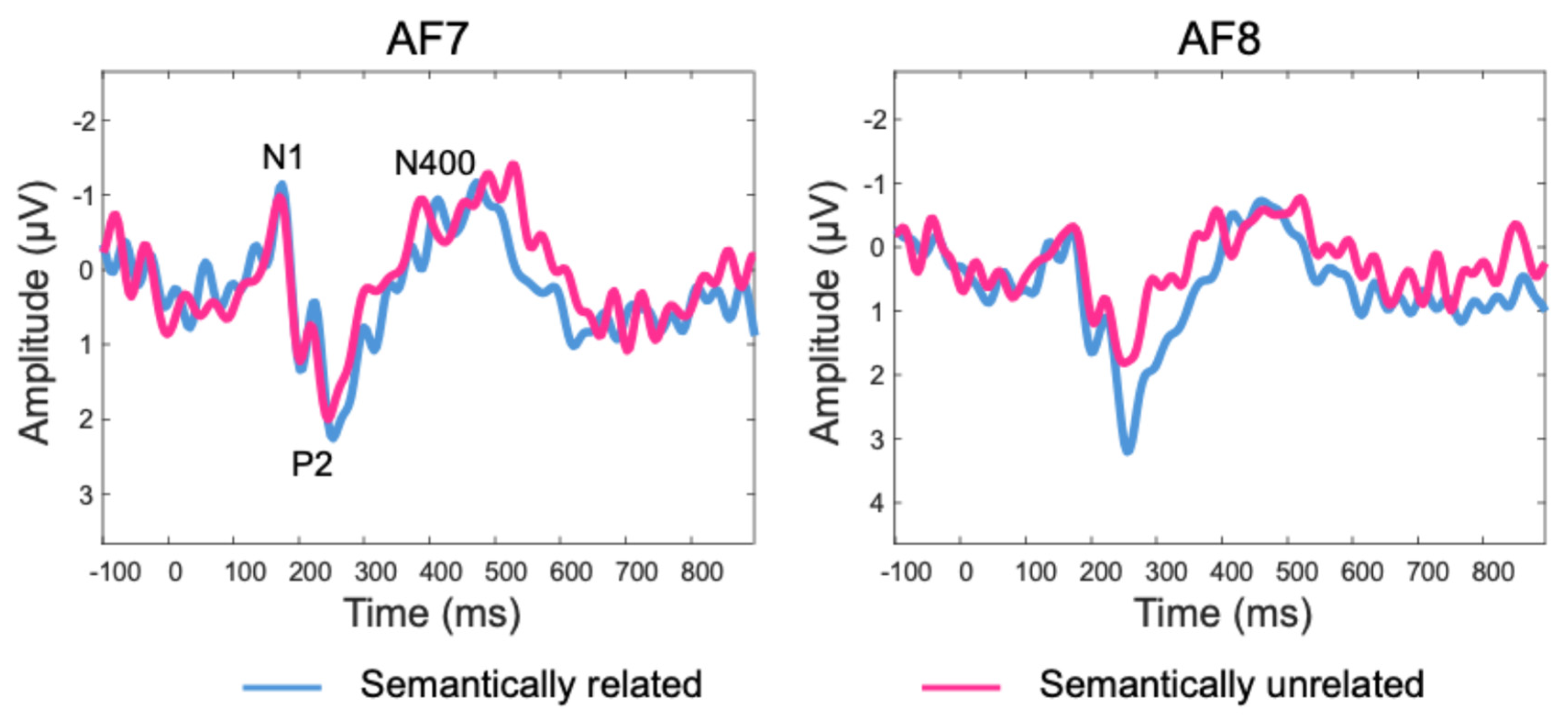

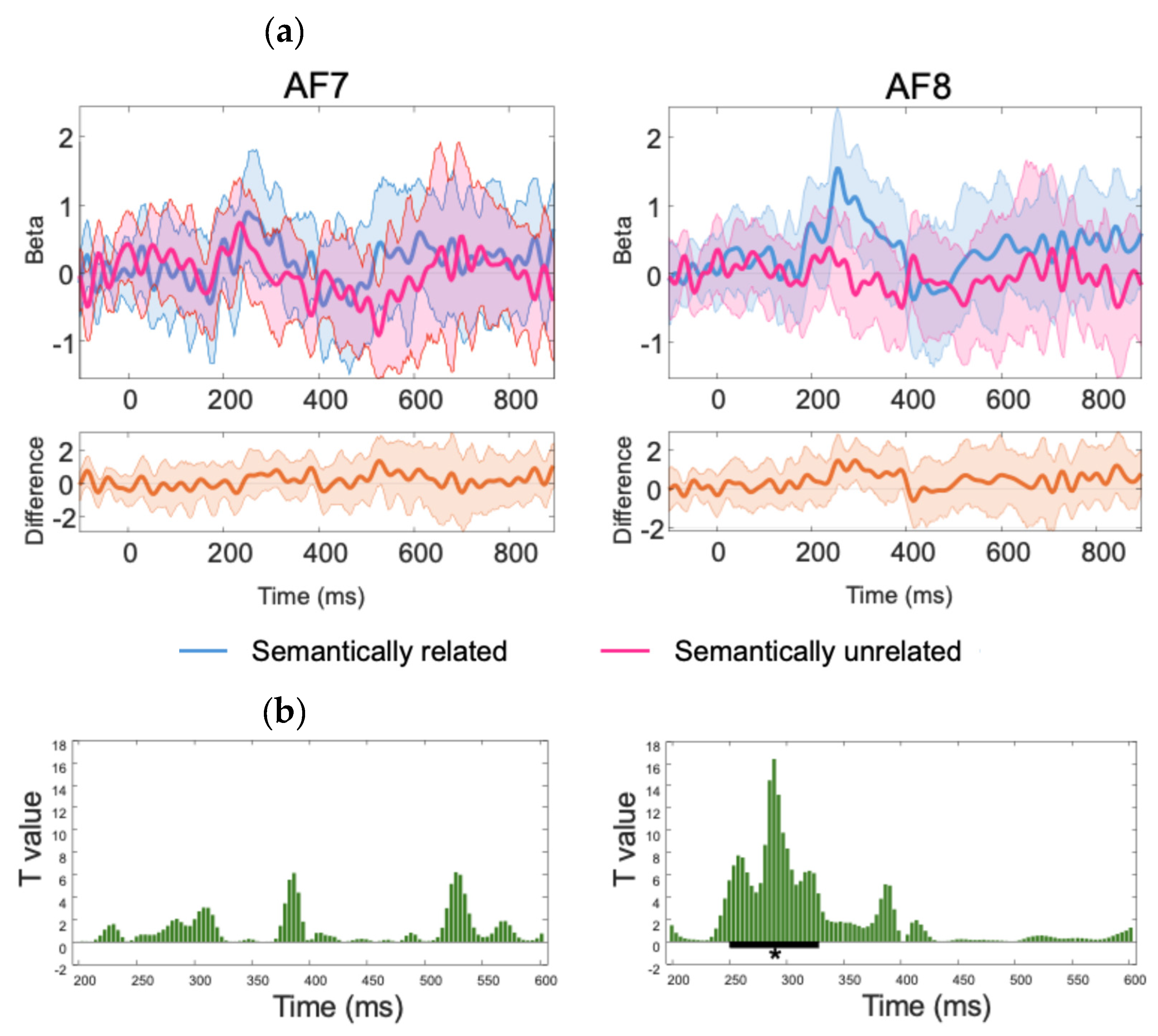

The grand average of mean subject-level single-trial ERP data is depicted in

Figure 3. Several ERP components (N1, P2, N400) can be clearly identified and align well with the existing ERP literature. Additionally, the ERPs time-locked to the onset of the target words showed a more negative deflection in the semantically unrelated condition than the related condition around the N400 time window. This effect was confirmed by the results of the statistical analyses revealing a significant difference over sensor AF8 for a cluster starting at 250 ms and ending at 328 ms (mean difference between semantically unrelated and related conditions = -1.13 microvolts), after correction for multiple comparisons using temporal clustering with a cluster forming threshold of p = 0.05 (See

Figure 4 for details on the statistical analysis and significance testing).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the efficacy of the Muse 2, a consumer-grade EEG headset, for measuring the N400 component, a language-related ERP associated with semantic processing [

17]. Our findings provide compelling evidence that the Muse 2 can reliably capture the N400 effect in a semantic relatedness judgment task, even with its limited electrode configuration. This outcome has important implications for increasing the accessibility and inclusivity of EEG research, particularly in the domain of language and cognition.

4.1. Validation of the Muse 2 for N400 Research

Consistent with previous research using traditional EEG systems, we observed a significant N400 effect, with a larger negativity elicited by semantically unrelated word pairs compared to semantically related ones. This effect was evident over the right frontal electrode (AF8), aligning with findings from prior studies showing a slight right-hemisphere bias for the N400 elicited by written words [

17]. The successful capture of this effect with the Muse 2 suggests that this affordable and portable device can be a viable tool for investigating semantic processing in language. Note that the high accuracy rates observed in both conditions of the SRJT indicate that participants were attentive and engaged in the task. Moreover, the lack of significant differences in accuracy between conditions confirms that the task difficulty was well-balanced, ensuring that the observed N400 effect was driven by semantic relatedness rather than variations in task demands. In conjunction with the ERP findings, the behavioral results thus provide strong support for the validity of the SRJT paradigm implemented with the Muse 2 headset to measure the semantic N400 effect.

The reliability analysis further strengthens our confidence in the Muse 2’s capability for ERP research. The dependability estimates obtained for the N400 data indicate acceptable internal consistency, suggesting that the Muse 2 can produce reliable ERP waveforms [

35], and highlighting its potential suitability for individual differences research. This finding is particularly encouraging given the inherent challenges of using consumer-grade EEG devices for ERP research, such as potential signal quality and noise reduction limitations [

3]. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that despite the promising results, consumer-grade devices like the Muse 2 may require more rigorous pre-processing and analysis procedures to account for potential artifacts and lower signal-to-noise ratios than research-grade systems. Furthermore, while Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is a common technique for artifact correction in EEG research [

41], its effectiveness on data from the Muse 2 has not yet been systematically established [

42].

4.2. Expanding Access and Inclusion in EEG Research

The Muse poses solutions to common EEG challenges of equity and inclusion. For instance, a potential benefit is the opportunity to reach previously inaccessible populations. Studies conducted in a university laboratory are often limited to undergraduate students seeking class credit or community members seeking compensation. Restricting studies to these demographics limits the scope of research on literacy, learning disabilities, and development, creating a significant barrier to generalizability. A researcher using the Muse can collect data at a school and reach a desirable sample size of a population that is difficult to reach in a relatively short period of time. In addition to schools, Muse studies can be conducted at locations with greater access to target and marginalized populations such as adult literacy centers and English as a Second Language programs. People of color are disproportionately underrepresented in ERP research, which is due in part to barriers and assumptions associated with hair type and style [

43]. Because the sensors contact hairless locations, the Muse can easily be donned by individuals with various hairstyles and textures. Participants do not have to worry about wetting their hair or removing conductive gel, as these ultra-portable EEG devices are less invasive, more comfortable, and easier to adjust compared to a traditional EEG net or cap. This could also make the headband preferable for individuals with sensory issues or those averse to touch.

The Muse also offers the opportunity to democratize language ERP research. Researchers without the funding necessary to purchase a traditional EEG system can use the Muse as an effective alternative to wired systems. This can offer early-career researchers in fields with less funding for neuroscience research the ability to conduct language ERP research without being limited by financial and logistical barriers. Similarly, the Muse offers a straightforward alternative for students who lack the experience or the timeframe to conduct EEG studies with a wired system independently.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the promising results, it is essential to acknowledge some limitations. First, while the Muse 2 offers affordability and portability, it has a limited number of electrodes compared to research-grade EEG systems, which restricts its ability to capture the full spatial distribution of ERP components. However, the Muse 2’s limited electrode configuration may not be a significant barrier in specific research contexts. For instance, when investigating ERP components with well-known and focused scalp distributions, such as the frontal N400 demonstrated in this study or the parietal P300, the Muse 2 can effectively capture these effects. Additionally, if the research question primarily concerns the timing and amplitude of ERP components rather than their precise spatial location, the Muse 2 can provide valuable insights, particularly in studies examining cognitive training or language learning where temporal dynamics are prioritized.

Additionally, our study focused on the N400 component; further research is needed to assess the Muse 2’s sensitivity to other language-related ERPs, such as the ELAN and P600 related to morpho-syntactic processing [

44], as well as its applicability to different experimental paradigms. Indeed, this study focused on a relatively simple semantic judgment task. Future research could explore the use of the Muse 2 in more complex language processing paradigms, such as those involving sentence processing [

45], discourse comprehension [

46], or bilingual language processing [

47].

Finally, future studies should directly compare the Muse 2 with research-grade EEG systems (ideally with a simultaneous recording setup) to further validate its capabilities and identify any systematic differences in the data obtained from the two types of devices.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of the Muse 2 to expand the accessibility and inclusivity of EEG research. Its affordability and portability make it a promising tool for researchers with limited resources, allowing them to conduct EEG studies that might not be feasible with traditional systems. Moreover, the Muse 2’s user-friendly design and ability to be used in real-world settings can facilitate the inclusion of diverse participant populations, including children, older adults, and individuals with mobility impairments, who may face barriers to participating in laboratory-based research. This can potentially enhance the generalizability and ecological validity of EEG research findings. By demonstrating the feasibility of using the Muse 2 to measure the N400 effect, this study opens new avenues for research in language and cognition. Future studies could utilize this approach to investigate individual differences in semantic processing, assess language comprehension in clinical populations, and explore the neural correlates of language learning and development. By making EEG technology more accessible, we can accelerate discoveries in language and cognition and promote a more inclusive and equitable approach to brain research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and C.M.; methodology, H.H. and C.M.; software, H.H.; validation, H.H; formal analysis, H.H. and C.M.; investigation, H.H. & C.M.; resources, C.M.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H. & C.M.; writing—review and editing, H.H. & C.M.; visualization, H.H.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, H.H..; funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation grant number 1926736 awarded to C.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Middle Tennessee State University (IRB-FY2023-173 05/31/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the Muse Validation for ERP Repository at

https://osf.io/u6y9g/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Casson, A. Wearable EEG and Beyond. Biomedical Engineering Letters 2019, 9, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, S.J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique, Second Edition; 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, 2014; ISBN 978-0-262-52585-5.

- Niso, G.; Romero, E.; Moreau, J.T.; Araujo, A.; Krol, L.R. Wireless EEG: A Survey of Systems and Studies. NeuroImage (Orlando, Fla.) 2023, 269, 119774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothe, C.; Shirazi, S.Y.; Stenner, T.; Medine, D.; Boulay, C.; Grivich, M.I.; Mullen, T.; Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. The Lab Streaming Layer for Synchronized Multimodal Recording. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, J.; Gray, J.R.; Simpson, S.; MacAskill, M.; Höchenberger, R.; Sogo, H.; Kastman, E.; Lindeløv, J.K. PsychoPy2: Experiments in Behavior Made Easy. Behav Res 2019, 51, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillani, S.F.; Saeed, S.M.U.; Monis, Z.U.A.E.D.A.; Shabbir, Z.; Habib, F. Prediction of Perceived Stress Scores Using Low-Channel Electroencephalography Headband. 2021 International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technologies (IBCAST), Applied Sciences and Technologies (IBCAST), 2021 International Bhurban Conference on 2021, 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Hawley, L.L.; Rector, N.A.; DaSilva, A.; Laposa, J.M.; Richter, M.A. Technology Supported Mindfulness for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Self-Reported Mindfulness and EEG Correlates of Mind Wandering. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2021, 136, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.J.; Manso, L.J.; Ribeiro, E.P.; Ekart, A.; Faria, D.R. A Study on Mental State Classification Using EEG-Based Brain-Machine Interface. 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Intelligent Systems (IS), 2018 International Conference on 2018, 795–800. [CrossRef]

- Nanthini, K.; Pyingkodi, M.; Sivabalaselvamani, D.; Kaviya EEG Signal Analysis for Emotional Classification. 2022 3rd International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), 2022 3rd International Conference on 2022, 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Pu, L.; Lion, K.M.; Todorovic, M.; Moyle, W. Portable EEG Monitoring for Older Adults with Dementia and Chronic Pain—A Feasibility Study. Geriatric Nursing 2021, 42, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengmolee, W.; Chaisaen, R.; Autthasan, P.; Rungsilp, C.; Sa-Ih, N.; Cheaha, D.; Kumarnsit, E.; Wilaiprasitporn, T. Consumer-Grade Brain Measuring Sensor in People With Long-Term Kratom Consumption. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 6088–6097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.E.; Ouda, H.T.; Azab, M. MUSE: A Portable Cost-Efficient Lie Detector. 2018 IEEE 9th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), 2018 IEEE 9th Annual 2018, 242–246. [CrossRef]

- Krigolson, O.E.; Williams, C.C.; Norton, A.; Hassall, C.D.; Colino, F.L. Choosing MUSE: Validation of a Low-Cost, Portable EEG System for ERP Research. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigolson, O.E.; Hammerstrom, M.R.; Abimbola, W.; Trska, R.; Wright, B.W.; Hecker, K.G.; Binsted, G. Using Muse: Rapid Mobile Assessment of Brain Performance. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, N.T.; Meshi, D.; Bente, G.; Schmälzle, R. Media Neuroscience on a Shoestring: Examining Electrocortical Responses to Visual Stimuli via Mobile EEG. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cocquyt, E.; Van Laeken, H.; Van Mierlo, P.; De Letter, M. Test–Retest Reliability of Electroencephalographic and Magnetoencephalographic Measures Elicited during Language Tasks: A Literature Review. Eur J of Neuroscience 2023, 57, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M.; Federmeier, K.D. Thirty Years and Counting: Finding Meaning in the N400 Component of the Event-Related Brain Potential (ERP). Annual Review of Psychology 2011, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basma, B.; Savage, R.; Luk, G.; Bertone, A. Reading Disability in Children: Exploring the N400 and Its Associations with Set-For-Variability. Developmental Neuropsychology 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyal, M.; Groleau, C.; Bouchard, C.; Wilson, M.A.; Fecteau, S. Semantic Processing in Healthy Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of the N400 Differences. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, S.; Spencer, K.M.; Onitsuka, T.; Hirano, Y. Language-Related Neurophysiological Deficits in Schizophrenia. Clin EEG Neurosci 2020, 51, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, P.J.; Neville, H.J. Auditory and Visual Semantic Priming in Lexical Decision: A Comparison Using Event-Related Brain Potentials. Language and Cognitive Processes 1990, 5, 281–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentin, S.; McCarthy, G.; Wood, C.C. Event-Related Potentials, Lexical Decision and Semantic Priming. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 1985, 60, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.F.; Weber, K.; Gramfort, A.; Hämäläinen, M.S.; Kuperberg, G.R. Spatiotemporal Signatures of Lexical–Semantic Prediction. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balota, D.A.; Yap, M.J.; Hutchison, K.A.; Cortese, M.J.; Kessler, B.; Loftis, B.; Neely, J.H.; Nelson, D.L.; Simpson, G.B.; Treiman, R. The English Lexicon Project. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řehůřek, R.; Sojka, P. Software Framework for Topic Modelling with Large Corpora. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Grave, E.; Bojanowski, P.; Puhrsch, C.; Joulin, A. Advances in Pre-Training Distributed Word Representations 2017.

- The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB 2023.

- Milnik, V. Instruction of Electrode Placement to the International 10-20-System. Neurophysiologie-Labor 2006, 28, 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, J.; Bacon, R.; Blaizot, J.; Boissier, S.; Boselli, A.; NicolasBouché; Brinchmann, J.; Castro, N.; Ciesla, L.; Crowther, P.; et al. BlueMUSE: Project Overview and Science Cases. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An Open Source Toolbox for Analysis of Single-Trial EEG Dynamics Including Independent Component Analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soskic, A.; Jovanovic, V.; Styles, S.J.; Kappenman, E.S.; Kovic, V. How to Do Better N400 Studies: Reproducibility, Consistency and Adherence to Research Standards in the Existing Literature. Neuropsychology review 2022, 32, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The jamovi project Jamovi.

- Webb, N.M.; Shavelson, R.J.; Haertel, E.H. 4 Reliability Coefficients and Generalizability Theory. In Handbook of Statistics; Elsevier, 2006; Vol. 26, pp. 81–124 ISBN 978-0-444-52103-3.

- Clayson, P.E.; Miller, G.A. ERP Reliability Analysis (ERA) Toolbox: An Open-Source Toolbox for Analyzing the Reliability of Event-Related Brain Potentials. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2017, 111, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayson, P.E.; Miller, G.A. Psychometric Considerations in the Measurement of Event-Related Brain Potentials: Guidelines for Measurement and Reporting. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2017, 111, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, S.J.; Stewart, A.X.; Simmons, A.M.; Rhemtulla, M. Standardized Measurement Error: A Universal Metric of Data Quality for Averaged Event-related Potentials. Psychophysiology 2021, 58, e13793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, C.R.; Chauveau, N.; Gaspar, C.; Rousselet, G.A. LIMO EEG: A Toolbox for Hierarchical LInear MOdeling of ElectroEncephaloGraphic Data. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2011, 2011, e831409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, C.R.; Latinus, M.; Nichols, T.E.; Rousselet, G.A. Cluster-Based Computational Methods for Mass Univariate Analyses of Event-Related Brain Potentials/Fields: A Simulation Study. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2015, 250, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenveld, R.; Fries, P.; Maris, E.; Schoffelen, J.-M. FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive Electrophysiological Data. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2011, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, M.; Revonsuo, A. Cognitive Representations Underlying the N400 Priming Effect. Brain research. Cognitive brain research 2001, 12, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Sejnowski, T.; Makeig, S. Enhanced Detection of Artifacts in EEG Data Using Higher-Order Statistics and Independent Component Analysis. NeuroImage 2007, 34, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Martin, J.A. Automated Data Cleaning for the Muse EEG. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); IEEE: Houston, TX, USA, December 9 2021; pp. 1–5.

- Lees, T.; Ram, N.; Swingler, M.M.; Gatzke-Kopp, L.M. The Effect of Hair Type and Texture on Electroencephalography and Event-related Potential Data Quality. Psychophysiology 2024, 61, e14499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederici, A.D. Towards a Neural Basis of Auditory Sentence Processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2002, 6, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magne, C.; Besson, M.; Robert, S. Context Influences the Processing of Verb Transitivity in French Sentences: More Evidence for Semantic−syntax Interactions. Language and Cognition 2014, 6, 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, C.; Astésano, C.; Lacheret-Dujour, A.; Morel, M.; Alter, K.; Besson, M. On-Line Processing of “Pop-Out” Words in Spoken French Dialogues. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2005, 17, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, J.; Osterhout, L.; Kim, A. Neural Correlates of Second-Language Word Learning: Minimal Instruction Produces Rapid Change. Nat Neurosci 2004, 7, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).