6.1.2. Simulation Result Analysis

Design 5 cases to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method:

Case 1: Do not connect PV, EV, UV, DESS.

Case 2: Connect PV, EV, UV without joining DESS.

Case 3: Do not connect PV, EV, UV, join DESS.

Case 4: Connect PV, EV, UV, DESS, and configure DESS in sequence using the voltage sensitivity method described in reference[

12].

Case 5: Connect PV, EV, UV, DESS, and use the CPFSV mentioned in this article to configure DESS in sequence.

According to the above case division, the simulation results of DESS optimization configuration in this article are listed in

Table 1.

Table 2.

Simulation results in different cases.

Table 2.

Simulation results in different cases.

| Case |

Location |

EB(MWh) |

PB(MW) |

Cost (¥) |

| 1 |

— |

— |

— |

686472.83 |

| 2 |

— |

— |

— |

1676429.73 |

| 3 |

18/33 |

1.06/0.79 |

0.3/0.3 |

2374831.42 |

| 4 |

18/33/21 |

1.26/1.17/1.13 |

0.3/0.3/0.3 |

3286697.74 |

| 5 |

17/31/21 |

1.46/1.43/1.39 |

0.3/0.3/0.3 |

2411175.19 |

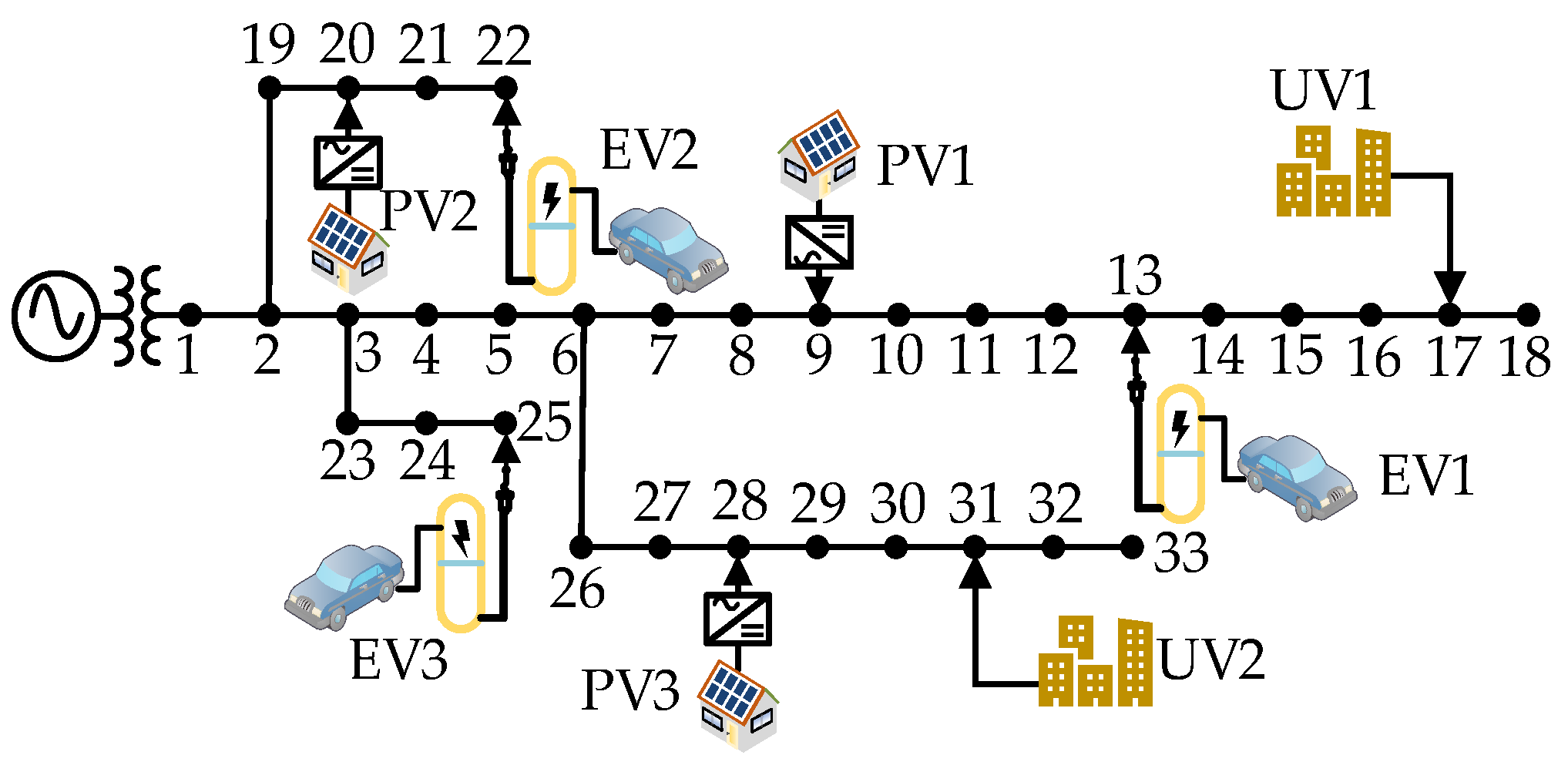

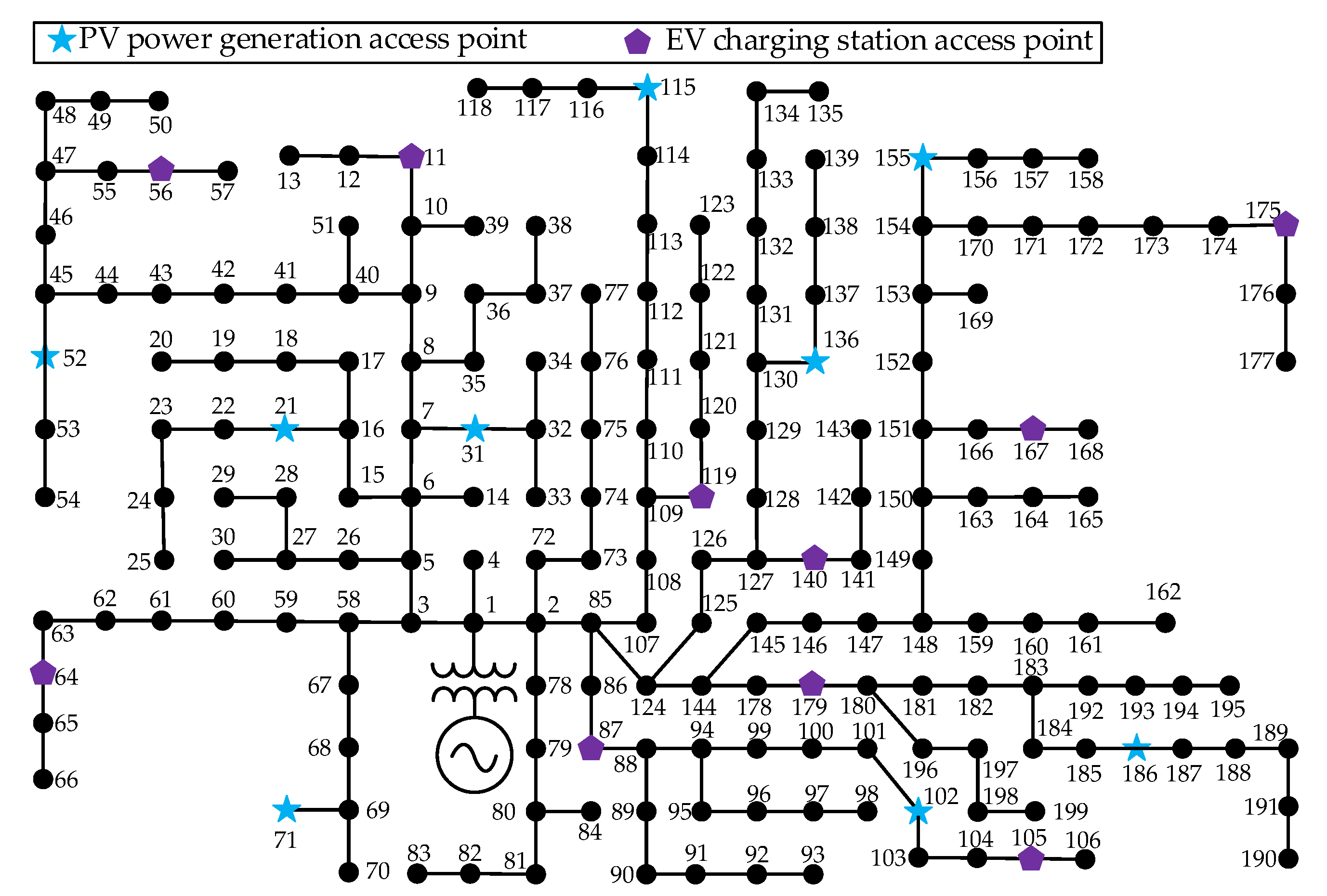

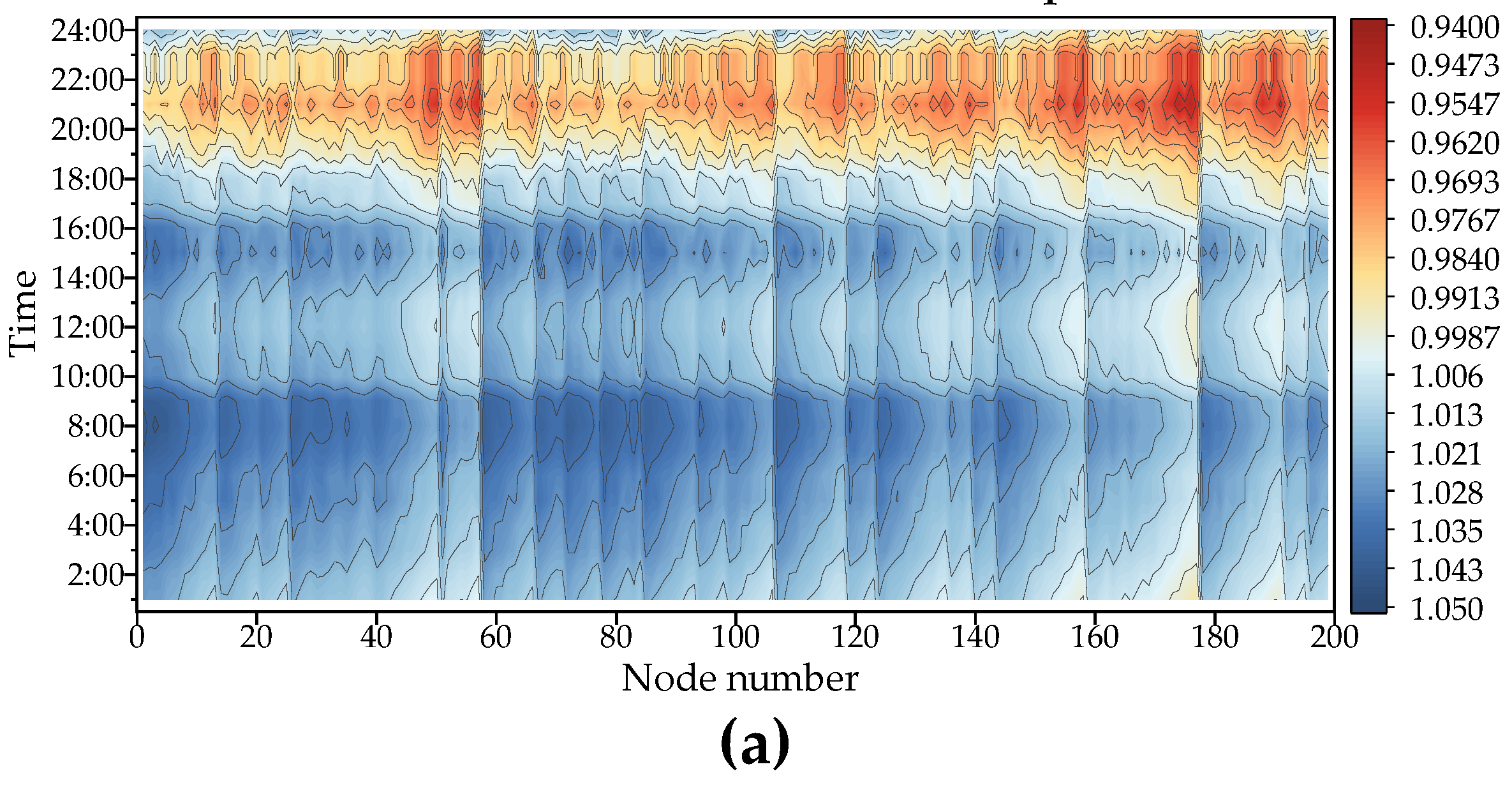

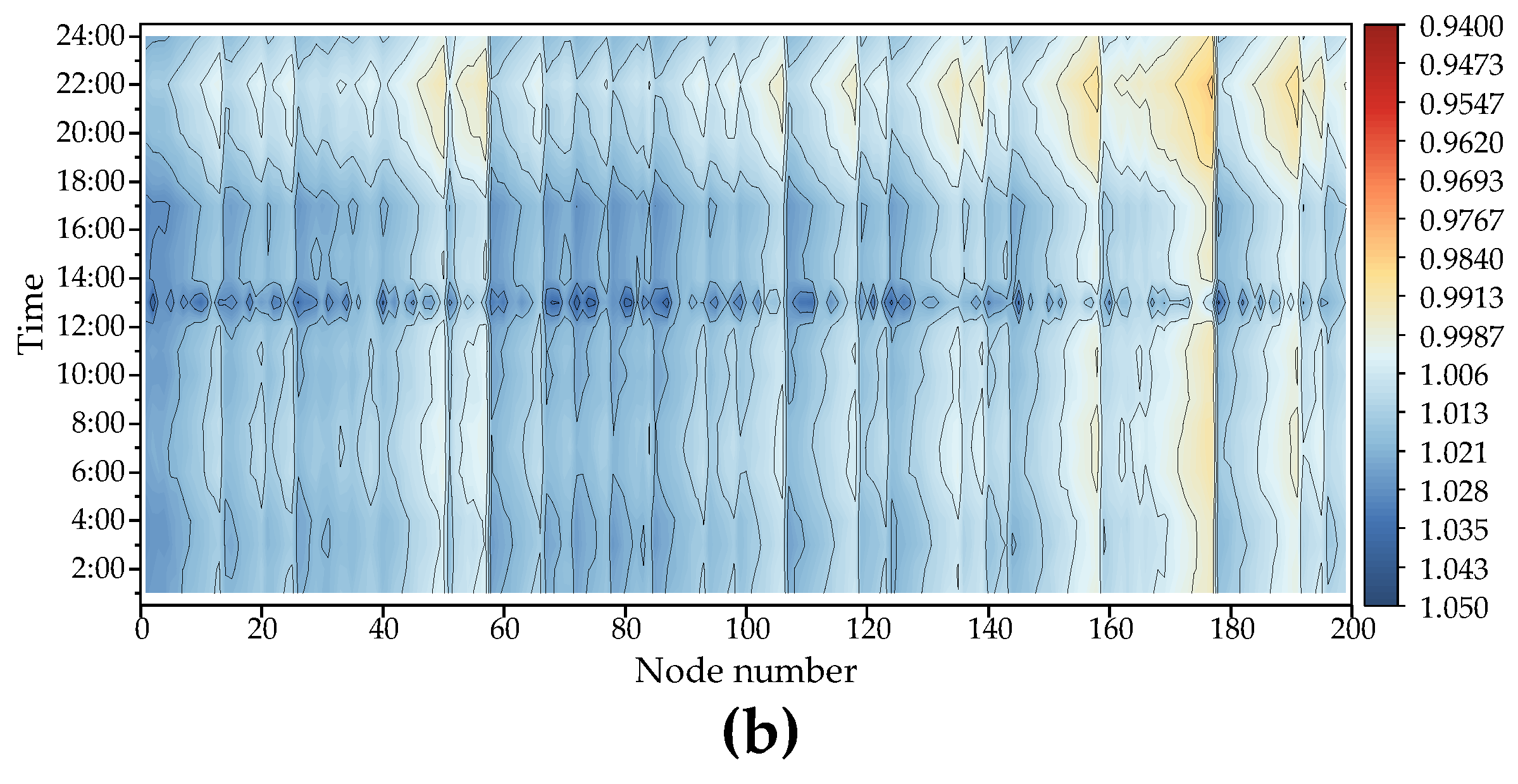

According to

Table 1, each node is limited to connecting one set of DESS, so during high load periods, DESS needs to operate at full power to restore bus voltage. In terms of location: Case 3 is the original system, and nodes 18 and 33 located at the end of the long feeder line are selected as the locations for energy storage access. The method used in case 4 only considers the influence of voltage and selects nodes that have better improvement effects on the low voltage problem of the system. Case 5 is the method proposed in this article, and the energy storage access node selected through the CPFSV strategy is a node that has a good effect on reducing line losses and improving system low voltage problems.

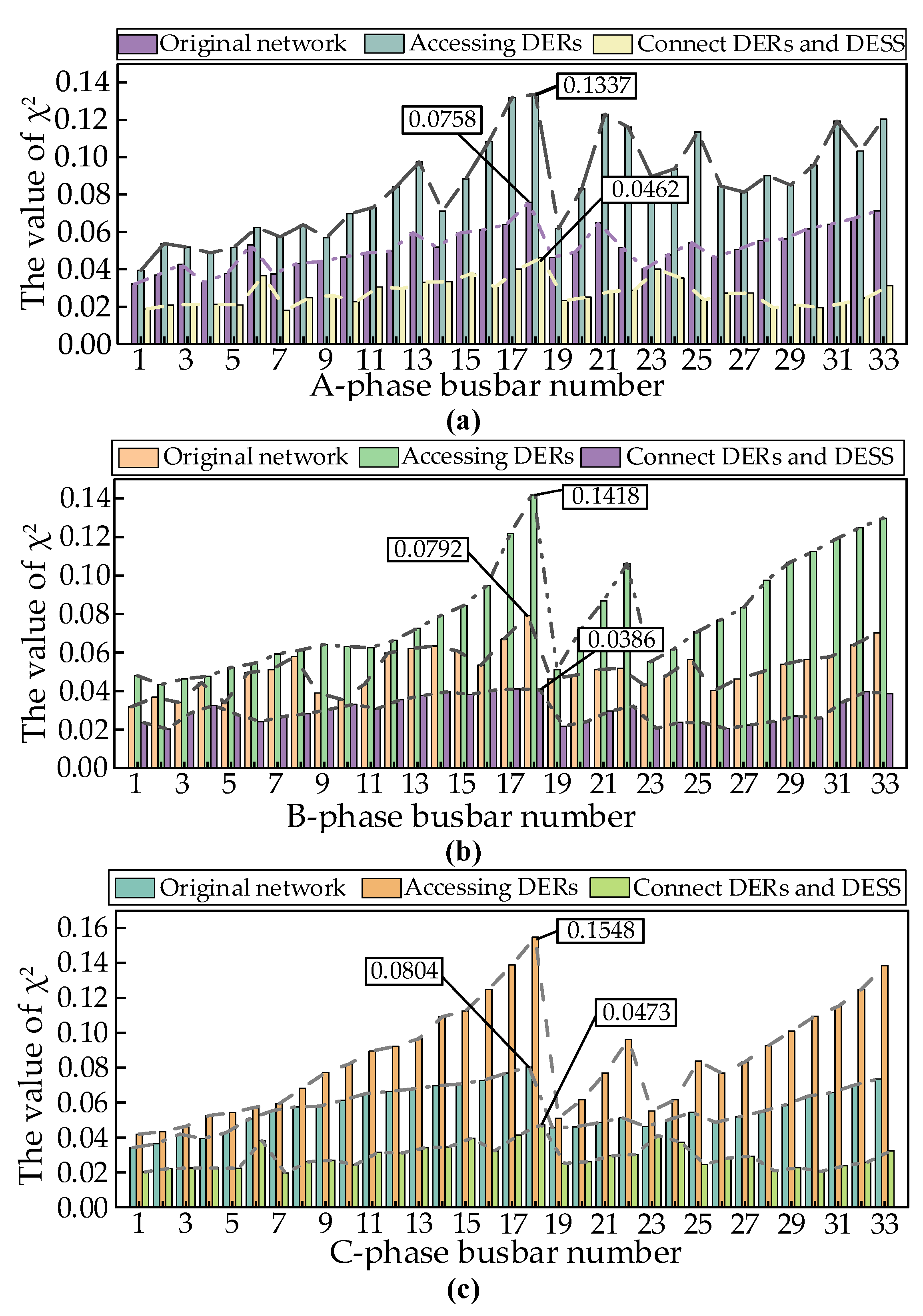

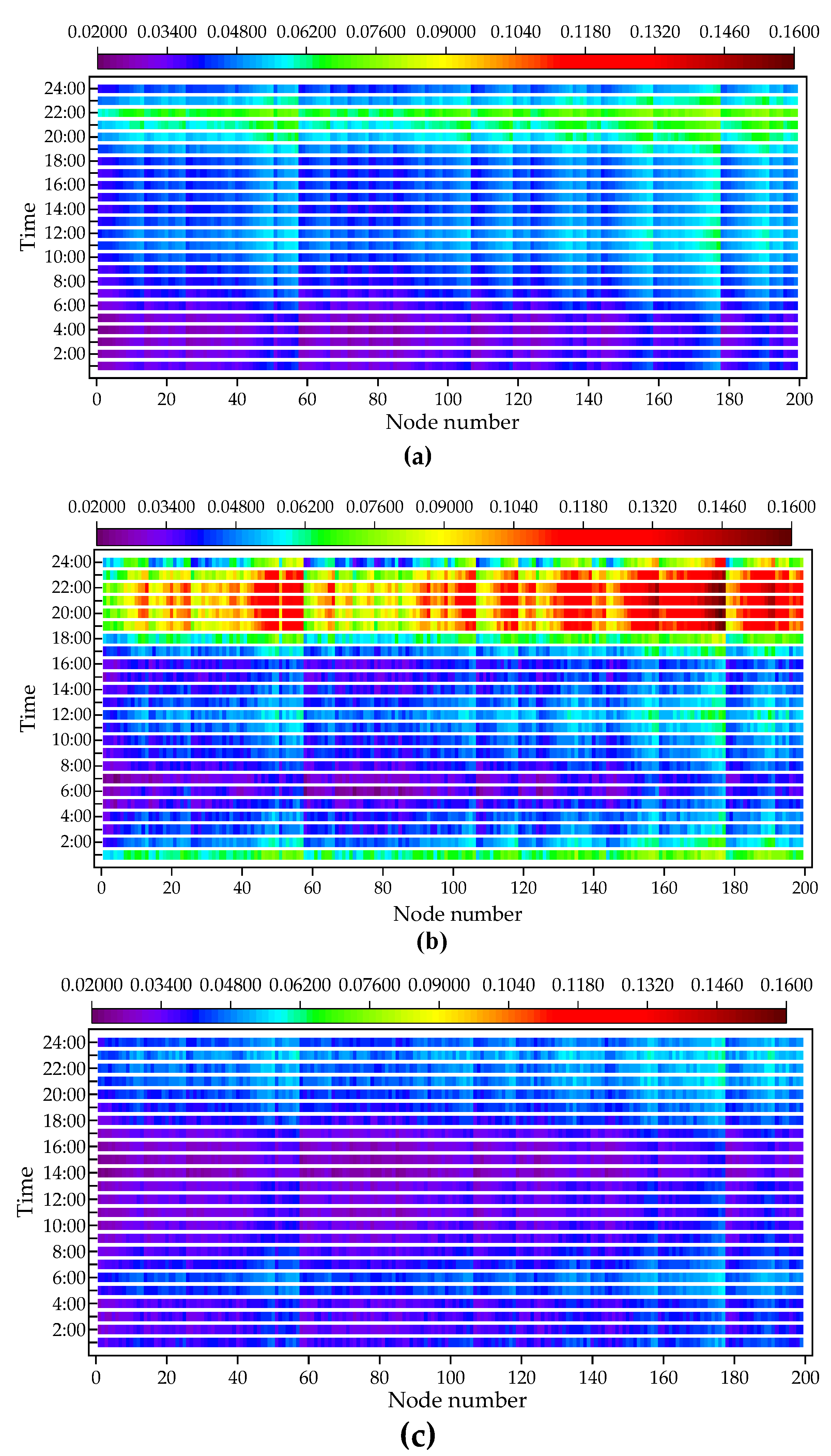

To demonstrate that the configured energy storage can significantly improve the power flow of each bus in the system, the average comprehensive power flow sensitivity variance of each node in cases 1 (original system), 2 (after connecting DERs), and 5 (connecting DERs and DESS) for 24 hours was compared. The results are shown in

Figure 6:

From

Figure 6, it can be seen that the maximum values of

in cases 1, 4, and 5 are 0.0804, 0.1548, and 0.0473, respectively, all located on the 18th bus of phase C; After connecting to DERS in case 4, the increase rate of bus

compared to case 1 is 92.5%; After connecting energy storage in case 5, the value reduction rate of bus

is 41.2% compared to case 1, and the value reduction rate of

is 69.4% based on case 4. From this, it can be inferred that the integration of DERS will increase system network losses and exacerbate voltage fluctuations at nodes; By configuring DESS at the largest node of CPFSV, the impact of a large number of DERs on system voltage can be effectively solved, and line losses can be reduced.

Table 3 shows the proportion of each target value in the optimal solution of energy storage capacity planning for five cases.

From

Table 3, it can be seen that the costs of cases 1 and 2 mainly come from network loss costs and voltage deviation costs, with voltage deviation costs exceeding 50%; However, the access of DERs in case 2 leads to an increase in transmission power, resulting in a significant increase in network loss and voltage deviation costs; Case 3: Due to the addition of only DESS, the operation and investment costs of energy storage have approached half, and the peak valley difference of the load curve has been improved to a certain extent, with a slight decrease in voltage deviation costs; Cases 4 and 5 are affected by the integration of DERs, which affects the energy storage charging and discharging strategy. In order to achieve the expected goals, an additional set of DESS is required, resulting in increased investment and operation costs for energy storage. Although the method used in case 4 has a poor effect on improving the peak valley difference and line loss of the load curve, and the total cost is relatively high; Case 5 adopts the CPFSV configuration strategy, which considers the role of energy storage in improving voltage quality and reducing network losses. It has a good effect on improving voltage quality and effectively reducing line losses, with a much lower total cost compared to Case 4.

Table 4 shows the distribution of energy storage costs in cases 3, 4, and 5.

The following conclusions can be drawn from

Table 4:

(1)In terms of electricity price arbitrage benefits (CPA), case 4 has a low energy storage utilization rate, resulting in less electricity price dividends during valley time, while case 5 is not affected and has higher returns;

(2)In terms of annual operation and maintenance costs (COM) for energy storage, case 5 adopts the CPFSV method to guide the operation of energy storage, which has high utilization efficiency and relatively more maintenance times, resulting in higher costs compared to case 4;

(3)In terms of line loss cost (CLOSS), cases 3 and 4 have low energy storage utilization efficiency, resulting in high transmission power for a long time and high line loss cost. Case 5 adopts the CPFSV analysis method, with high energy storage utilization and significantly reduced line loss costs;

(4)In terms of annual average investment cost (CIN), cases 4 and 5 have an additional set of energy storage compared to case 3, resulting in a significant increase in investment cost ratio.

(5)In terms of total cost (CTOTAL), compared to case 3, case 5 still has a similar total cost even with an additional set of energy storage, due to its high energy storage utilization efficiency, significant reduction in network loss costs, and significant increase in electricity price arbitrage benefits. Compared to case 4, the CPFSV planning method used in case 5 has a high energy storage utilization rate, reduces network loss costs, and has a good effect on cost savings.

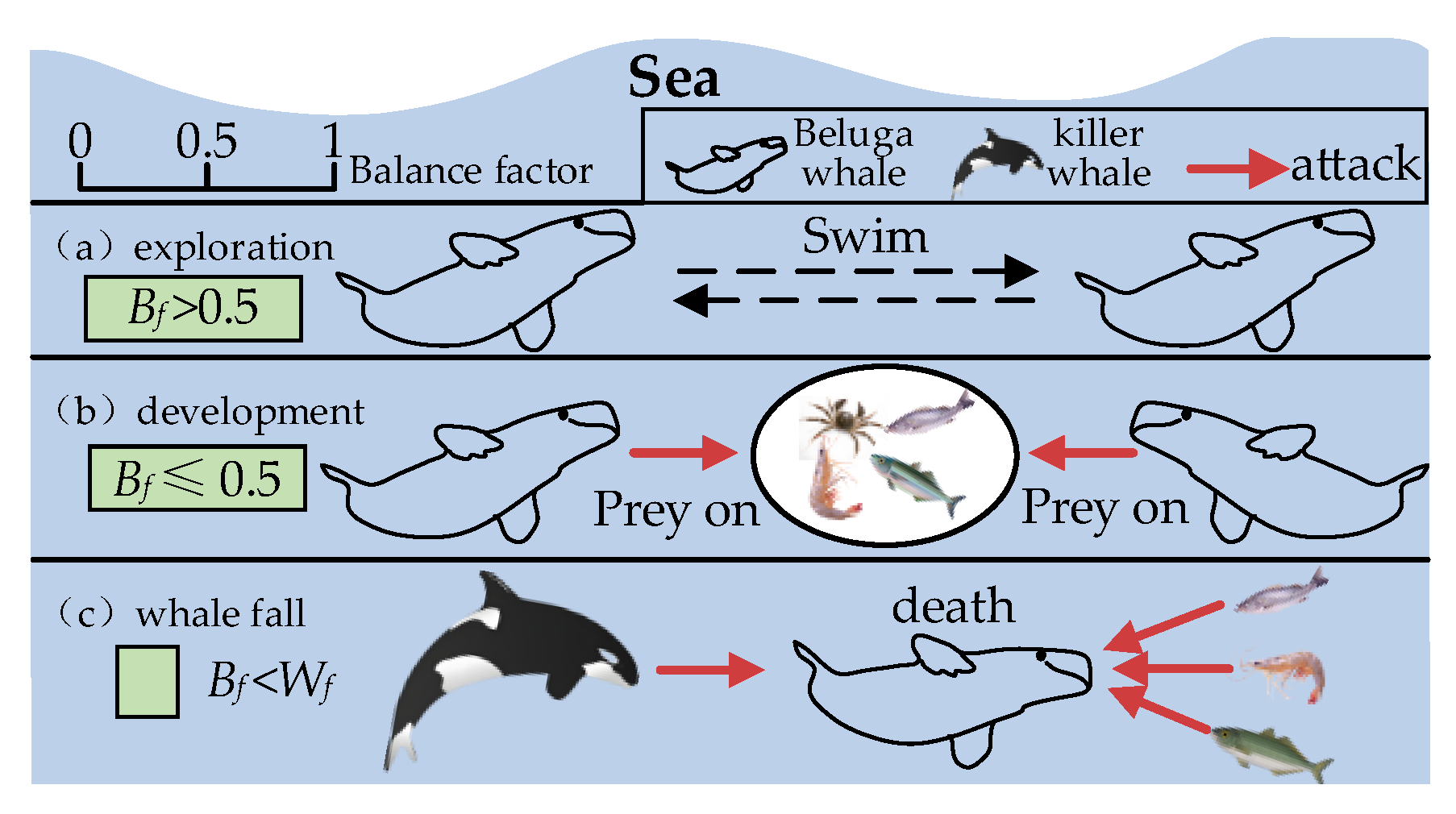

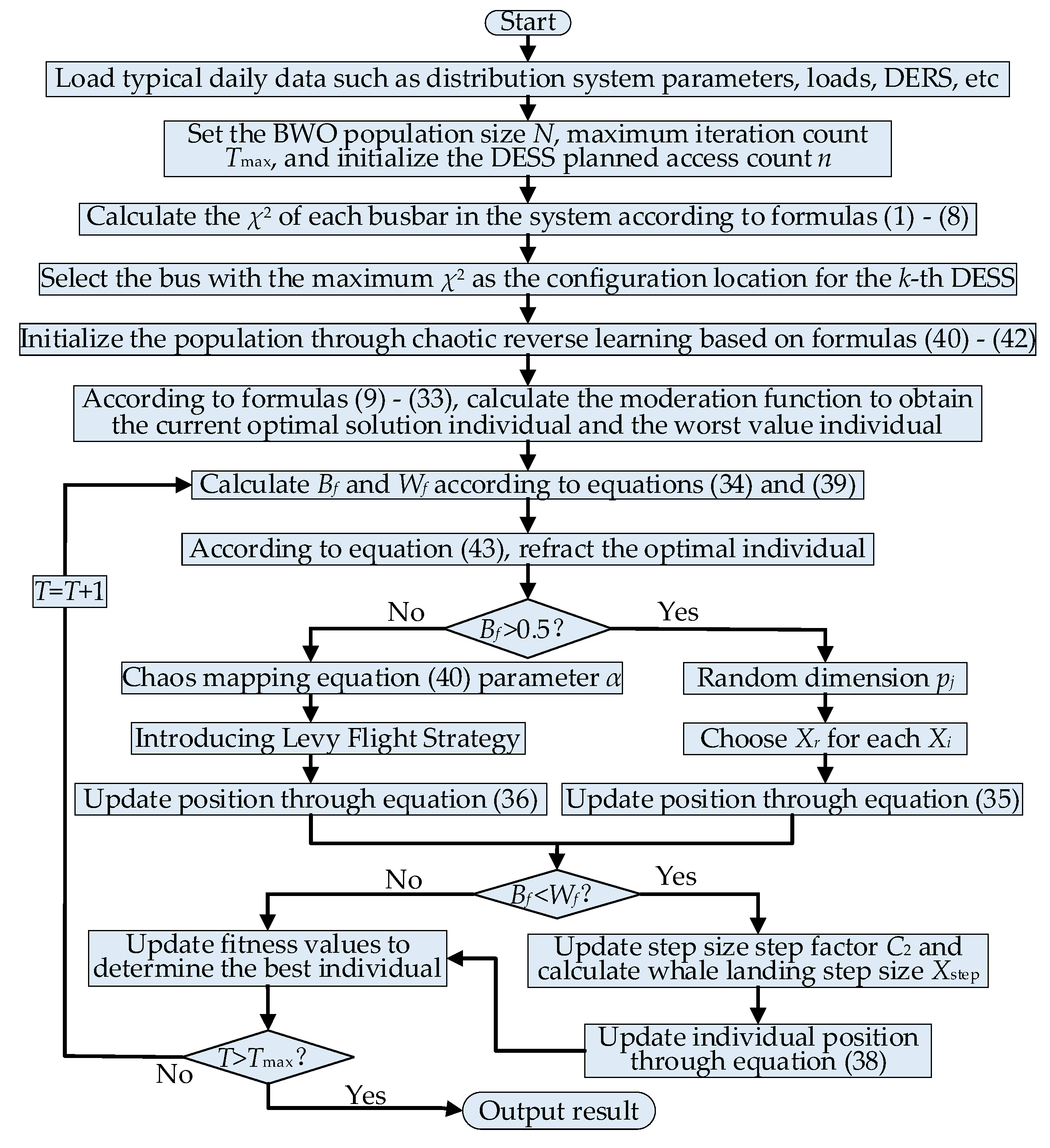

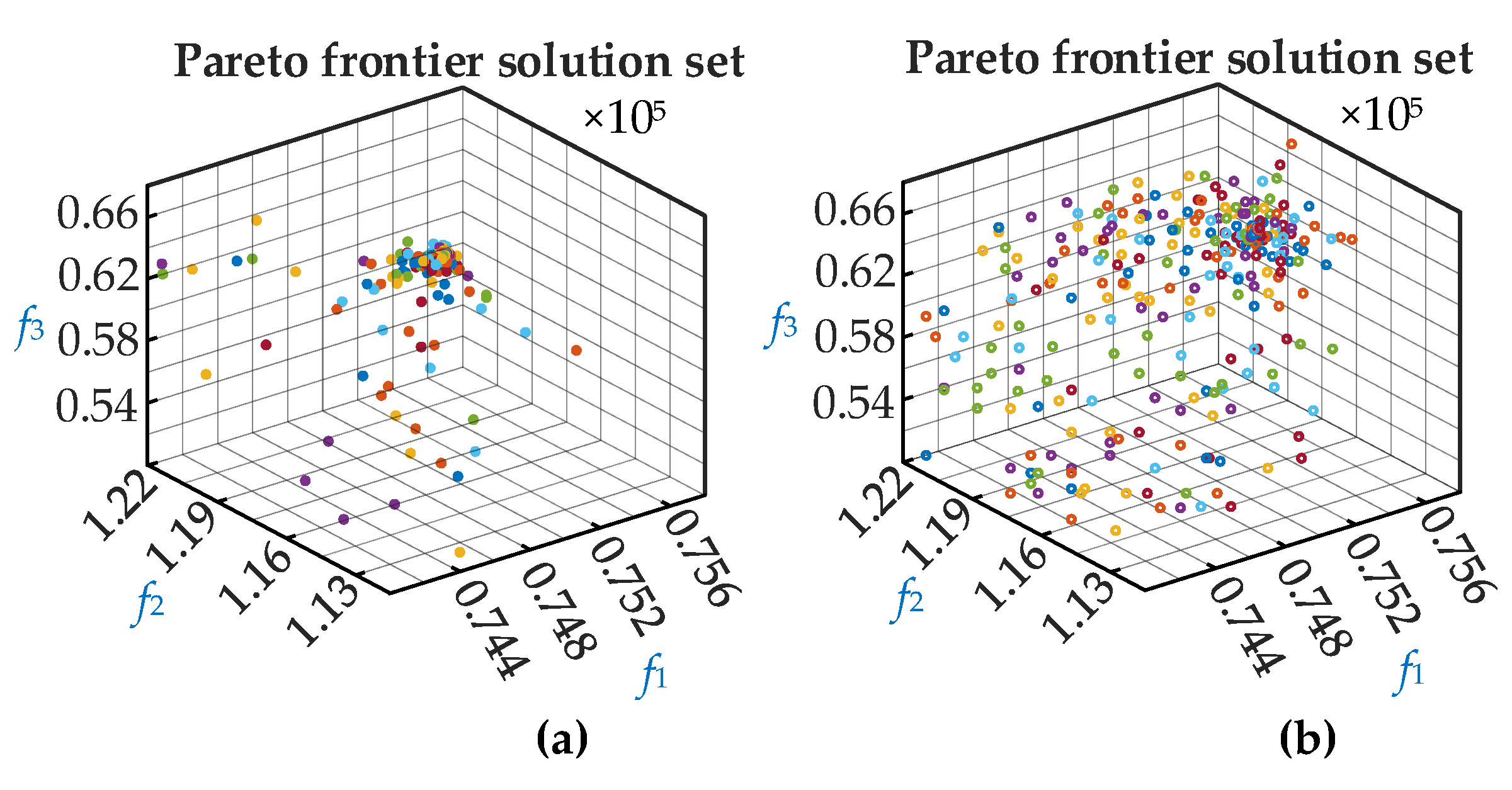

To demonstrate the superiority proposed in this article,

Figure 7 compares the Pareto solution sets of TWBWO algorithm and BWO algorithm. It can be seen that the TWBWO algorithm has better diversity in the solution set, more uniform distribution of solutions, and stronger ability to search for the global optimal variable.

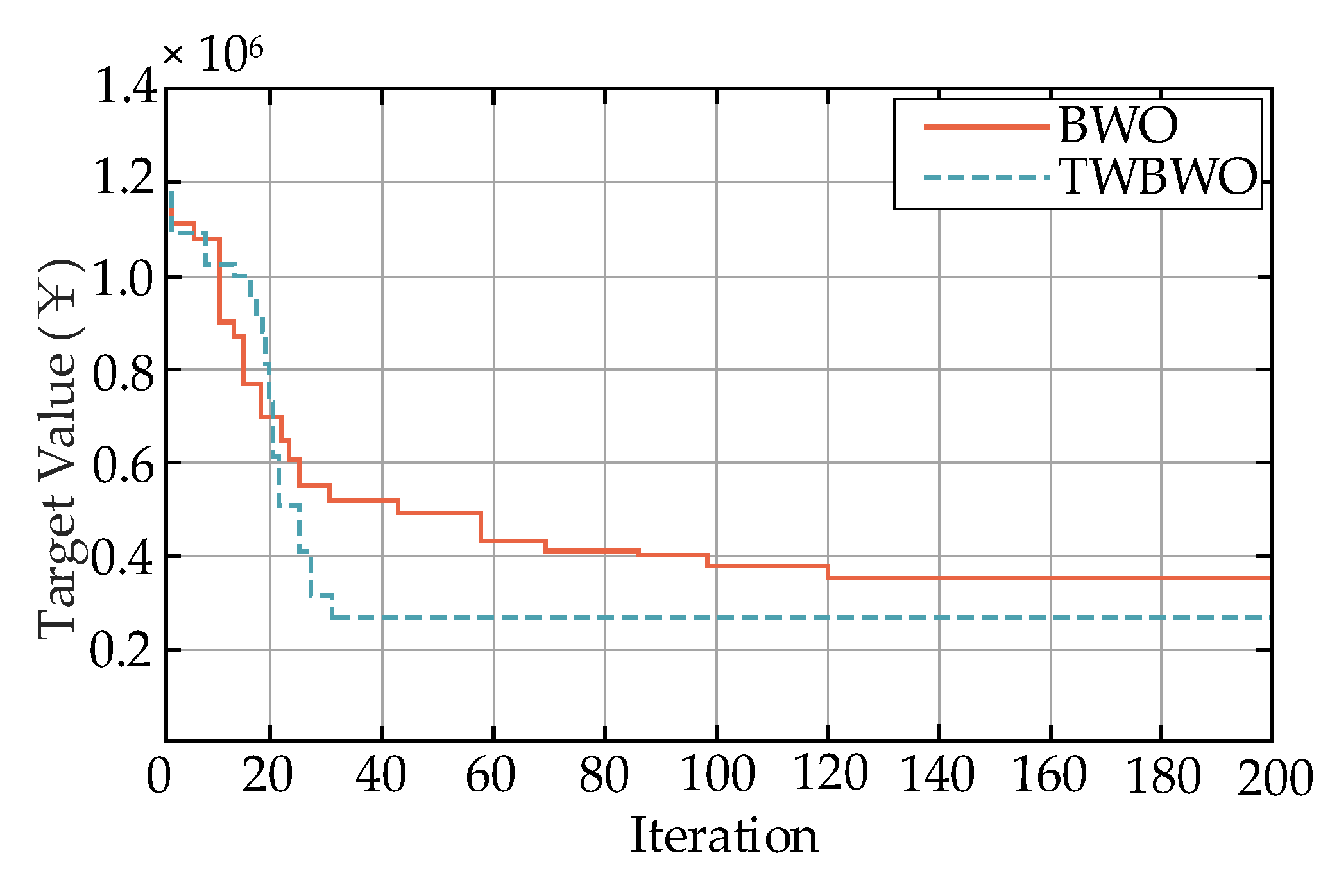

Comparing the iteration speed and convergence of two algorithms, the results are shown in

Figure 8. It can be seen that the TWBWO algorithm converges slower than the BWO algorithm in the early stages of iteration, because the TWBWO algorithm needs to perform chaotic reverse learning to initialize the population and the optimal individual refracted by water waves, resulting in slower initial search speed and direction determination. After the optimal individual is determined, both the convergence speed, search ability, and convergence results in the middle and later stages are better than the BWO algorithm.

Using the TWBWO algorithm to run case 5 100 times, the TOPSIS method was used to select the top 5 solutions with the best performance, as shown in

Table 2:

From

Table 5, it can be seen that the three objective functions cannot achieve optimal results simultaneously. Therefore, the optimal values for energy storage cost, voltage deviation cost, and load characteristic improvement can be selected based on specific needs.

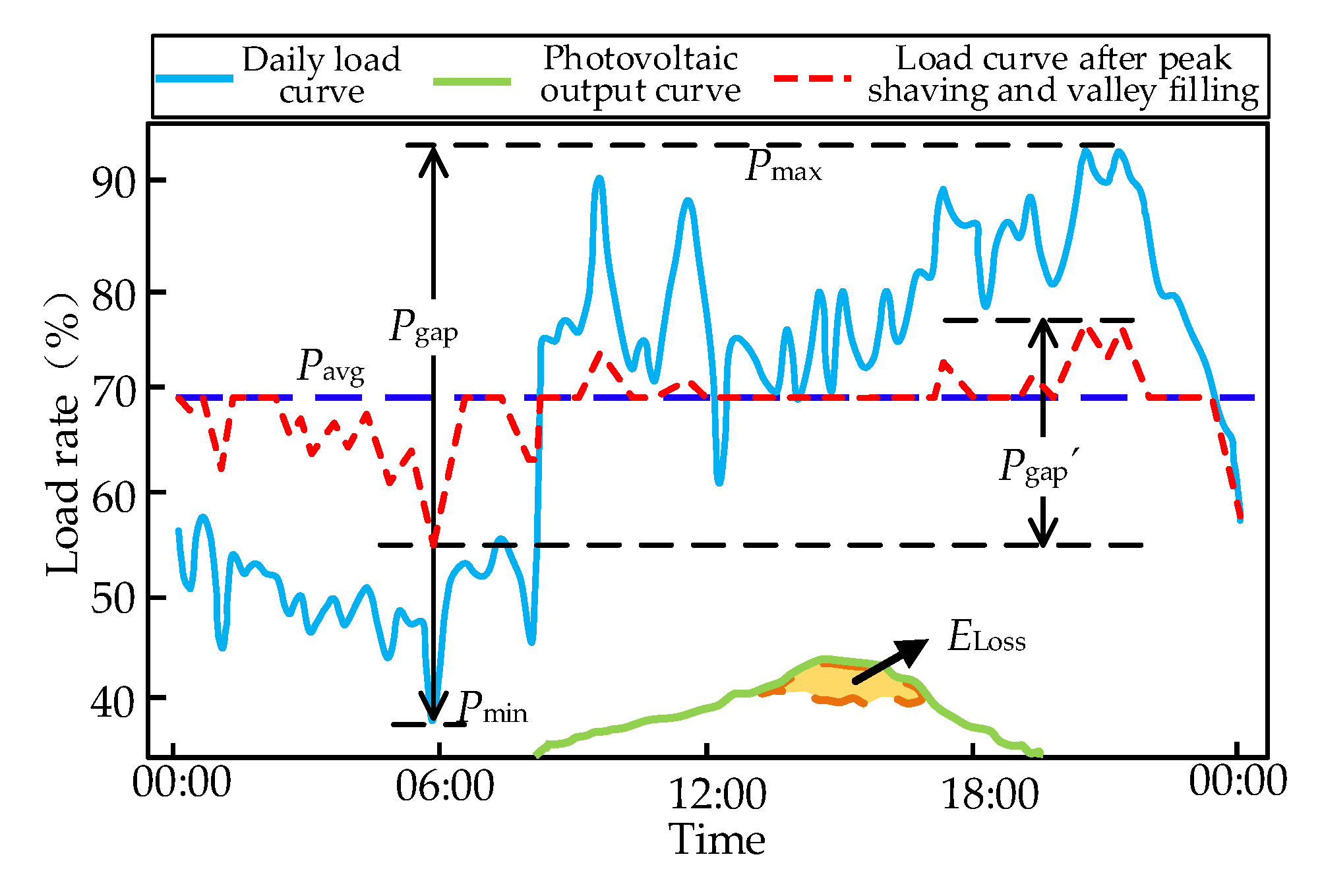

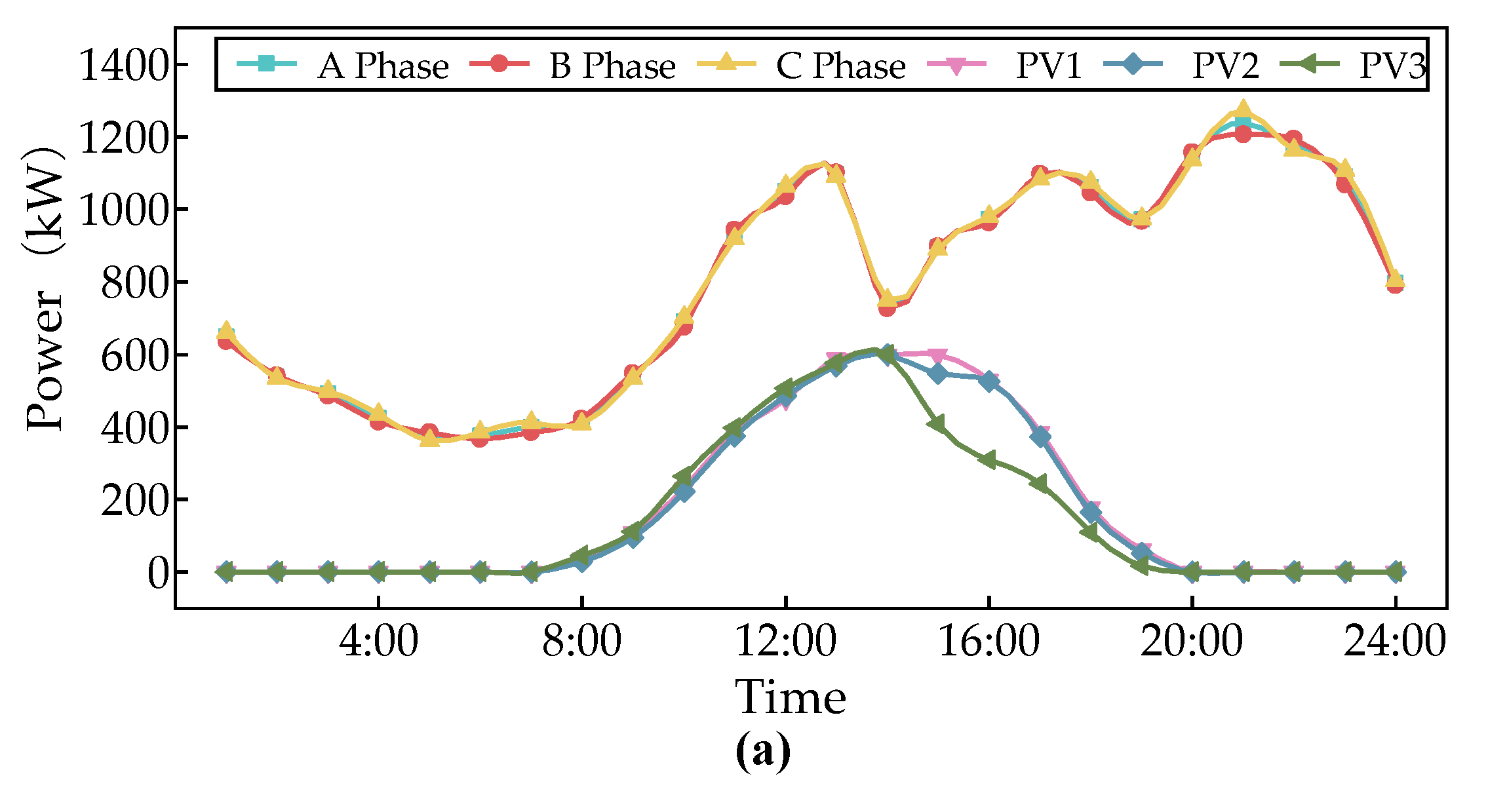

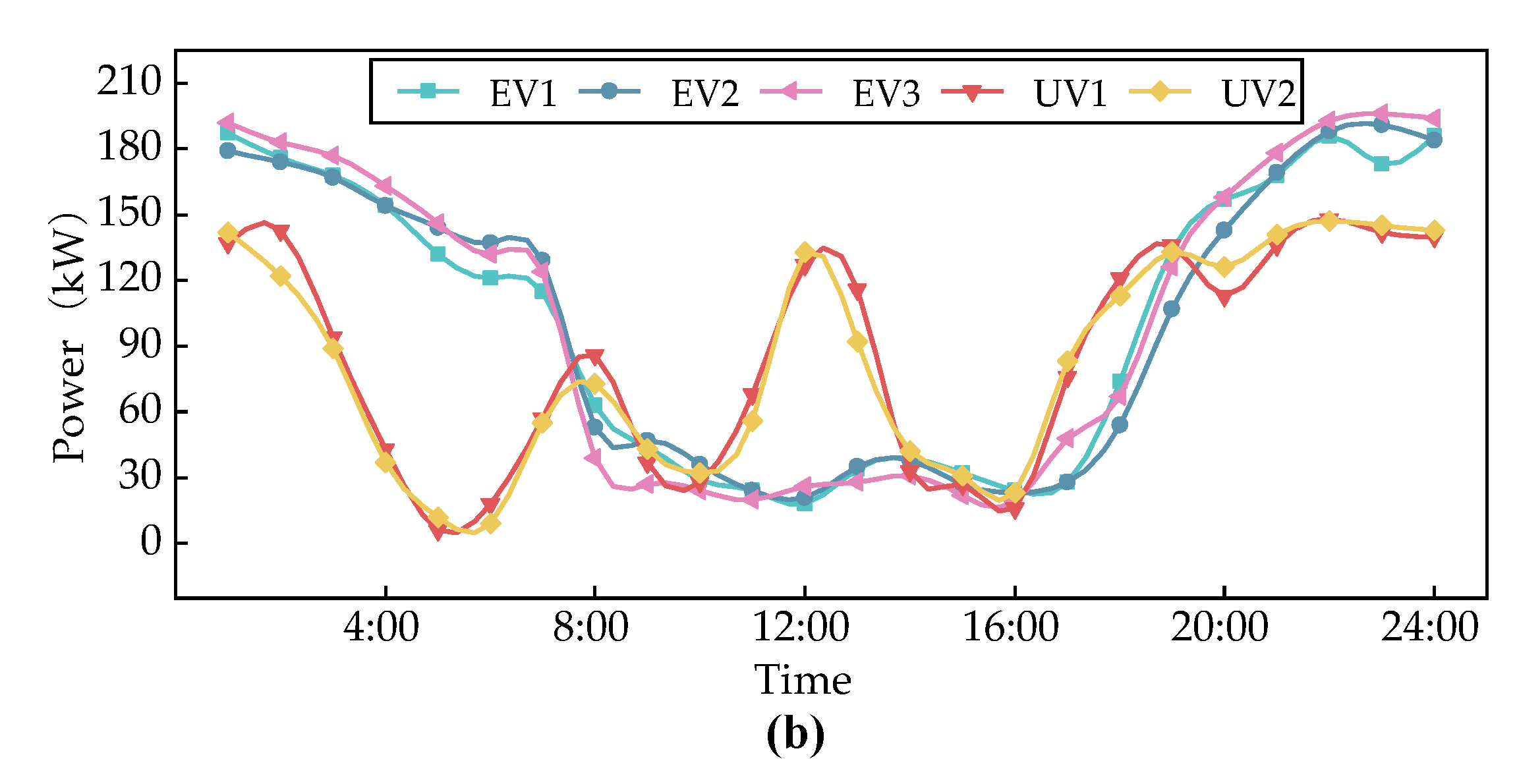

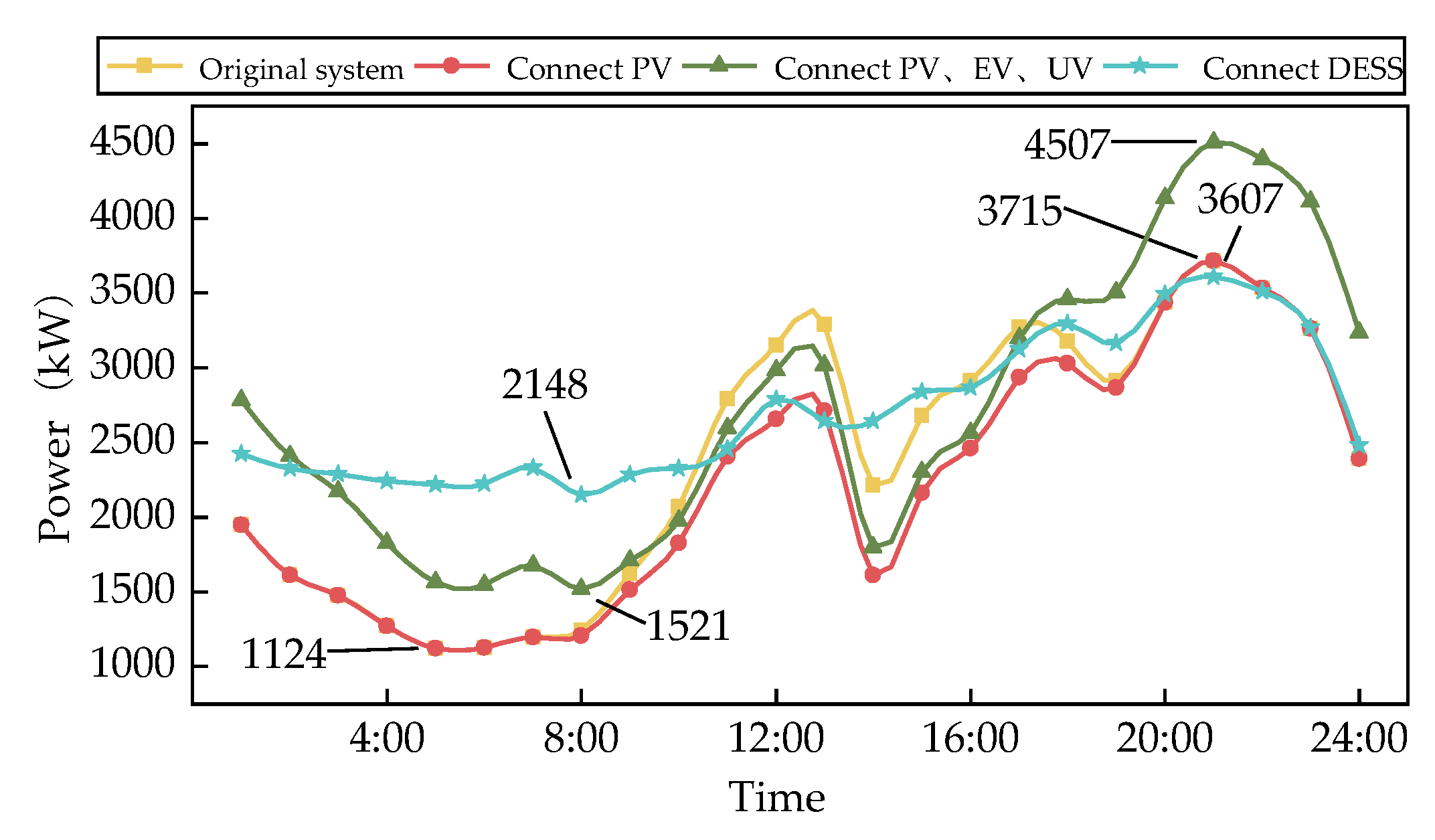

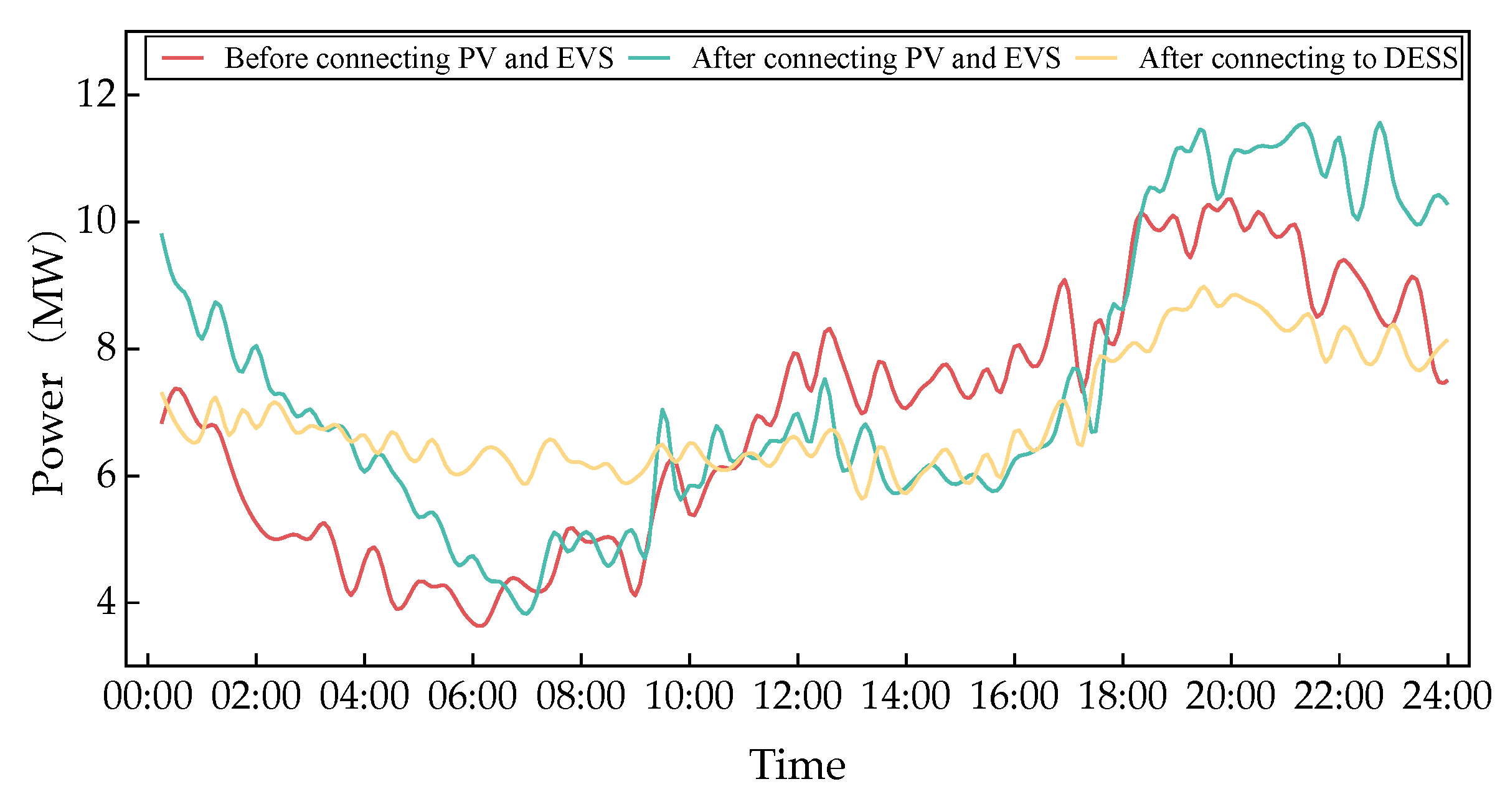

Figure 9 shows the system load curve after adding different resources.

From

Figure 9, it can be seen that after a large number of EVs and UVs were connected, the peak load of the system increased from 3715kW to 4507kW, an increase of 21.3%, causing the system to experience overload and overload cases. The integration of PV has to some extent alleviated the load of the system from 12:00-18:00, but it cannot alleviate the overload problem during the evening rush hour. After adding DESS, the peak load of the system decreased from 4507kW to 3607kW, a decrease of 20%; The peak valley difference decreased from 2591kW in the original system and 2986kW with PV, EV, and UV added to 1459kW, with a decrease of 43.7% and 51.1%, respectively. It can be seen that DESS can significantly reduce the peak load of adding a large number of EVs and UVs, smooth the load curve, alleviate the burden during peak periods of system electricity consumption, and improve the load rate during low periods of system electricity consumption. It can also shift the PV output and increase its penetration rate.

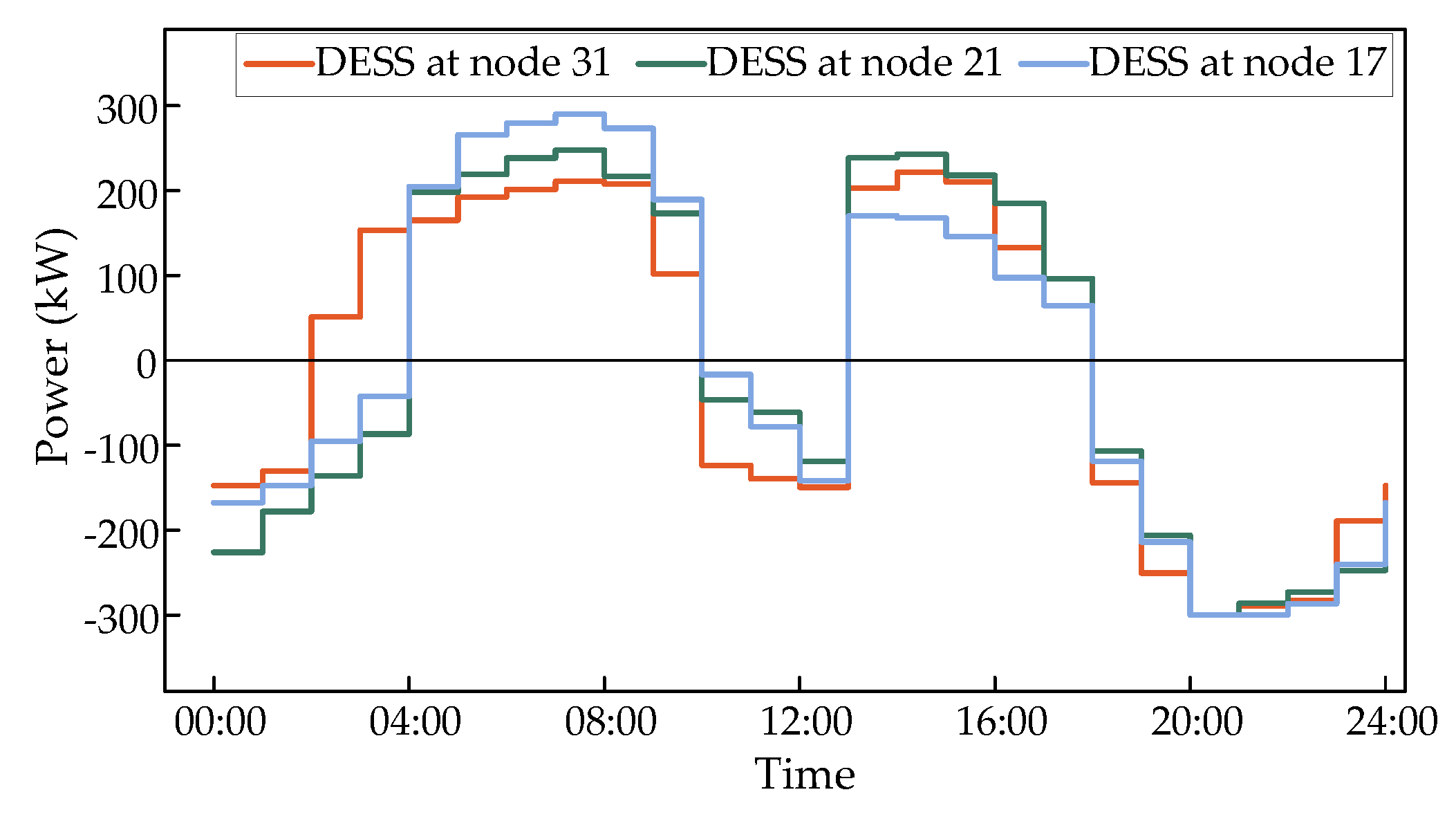

To explore the working conditions of DESS in case 5, the charge discharge curves of its three groups of DESS are shown in

Figure 10. A value greater than 0 indicates charging, while a value less than 0 indicates discharging.

As shown in

Figure 10, the charging and discharging processes of the three groups of DESS are all in a 2-charging and 2-discharging state. 13: From 00:00 to 16:00, DESS charges and shifts the photovoltaic output to ensure that the voltage of each bus does not exceed the upper limit; 20: From 00:00 to 22:00, all three groups of DESS are fully discharged to meet the load demand, alleviate system overload, and reduce network losses.

However, the DESS of node 17 is far away from the power supply point and the PV power generation access point, and the bus is close to the urban villages and the points where a large number of electric vehicles are connected. Therefore, its energy storage is discharged at maximum power for two consecutive hours from 20:00 to 22:00, and is affected by electric vehicles. It does not start charging until after 4am, and the power absorbed by photovoltaic power generation in the afternoon is not as good as the other two groups. There are two sets of EVs connected near the DESS of node 21, which are adjacent to photovoltaic power generation. They are also affected by electric vehicles and do not start charging until after 4am. In the afternoon, they absorb photovoltaic power with a larger charging power. The DESS of node 33 is less affected and starts charging after 2:00. Therefore, the charging and discharging situation of the three groups of DESS configured is relatively reasonable.