1. Introduction

Arterial diseases (AD), which include coronary artery disease (CAD) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD), are a significant public health concern with high mortality and serious morbidity [

1,

2,

3]. Angioplasty has made substantial progress in achieving vascular patency. However, restenosis remains a challenge primarily due to negative vascular remodeling and elastic recoil after angioplasty [

4]. In recent years, stents have played a crucial role in the interventional treatment of vascular occlusions [

5]. While the bare-metal stents (BMSs) have reduced the effects of elastic recoil and negative remodeling, they have also led to neointimal hyperplasia and eventually in-stent restenosis due to vascular response to stent-related injury [

6].

To address restenosis, various endovascular intervention strategies have been developed using different platforms with varying designs, such as drug-eluting stents (DES) and drug-coated balloons (DCB). Despite significant progress, the issue of restenosis has not been fully resolved [

7]. Additionally, the release of antiproliferative drugs from these devices has raised safety concerns, including the risk of death [

8,

9]. It has also been observed that durable stent structures, like stainless steel and cobalt chrome, cause chronic inflammation, disrupt reendothelialization, increase the likelihood of late stent thrombosis, and delay arterial recovery [

10,

11]. Moreover, these permanent stents hinder any subsequent interventions. In response to these challenges, bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) that dissolve over time and are excreted by the body have been developed [

11]. BVSs are expected to not only prevent restenosis but also avoid the long-term side effects of permanent implants [

5].

The aim of this narrative review is to provide an overview of the use of biodegradable stents in the endovascular treatment of vascular stenosis.

2. Fundamental Characteristics of Biodegradable Stents

For a stent to be considered ideal, it should possess optimal characteristics in terms of deliverability, efficacy and safety. To elaborate further, an ideal stent should be biocompatible, flexible, deliverable and have good radial strength and fracture resistance. It should also promote vascular reendothelialization, healing and remodeling, while causing minimal inflammatory reactions and low rates of neointimal hyperplasia and stent thrombosis in long-term follow-up [

12,

13,

14,

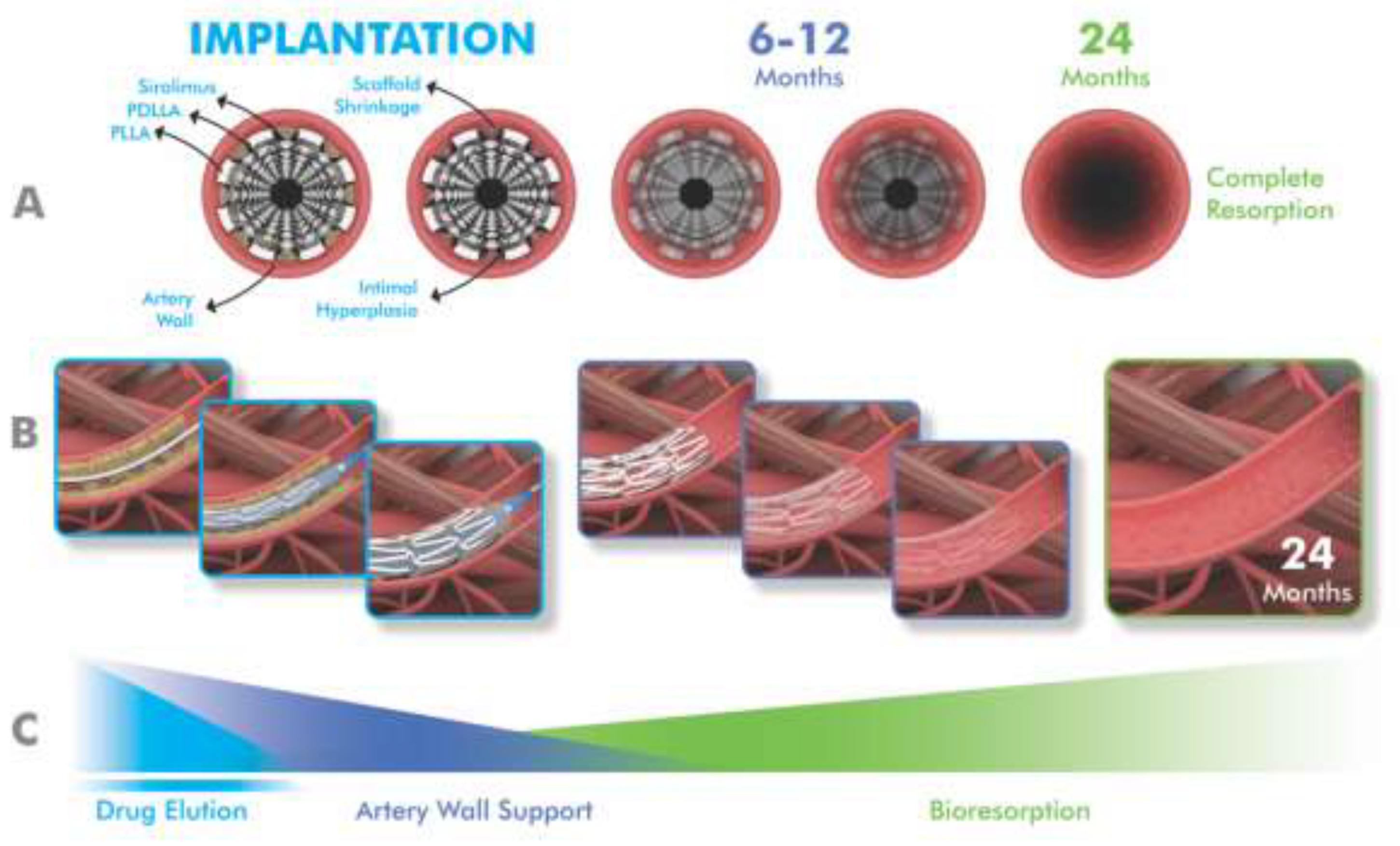

15]. In this context, drug-eluting BVSs have attracted interest as an alternative to drug-eluting stents because they are designed to provide early mechanical support and normalize vascular structure and function by completely resorbing over the next few years and to prevent very late adverse events [

16,

17,

18,

19] (

Figure 1).

The most studied bioresorbable scaffold is Absorb BVS (Abbott Vascular). The strut part consists of a balloon-expandable poly-L-lactide structure coated with a thin layer of bioresorbable poly-D, L-lactide capable of releasing everolimus [

20]. Various synthesized polymeric materials such as poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), poly(lactide-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly glycolic acid (PGA), and poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) have been widely used for the biodegradable polymeric stent struts [

21]. In addition to polymers, biodegradable stent struts are also manufactured from metals such as magnesium, zinc or iron or their alloys, providing stronger radial strength and compression resistance [

5]. Compared to metallic stents, those with synthetic polymer struts can be easily adapted to various structures and shapes [

21]. However, they have lower radial strength than the metallic biodegradable stents [

22]. On the other hand, the radial strength and compression resistance of BVSs are overall lower than that of permanent stents such as stainless steel and CoCr alloy [

5,

23].

Table 1 outlines the basic features of some selected commercial biodegradable stents.

BRS primarily addresses overcoming potential limitations of DES application, such as permanent vascular caging, vasomotion limitation, adaptive vascular remodeling, and very late stent thrombosis [

24]. One of the most significant drawback of BVS is the stent thickness, which is meant to compensate for decreased tensile and radial strength [

23]. The use of thicker stents can lead to placement difficulties, especially in small-diameter vessels, as well as thrombosis and other clinical issues. Other concerns such as polymer and scaffold degradation have also been linked to stent thrombosis [

20,

25]. Among all BVSs, the iron bioresorbable scaffolds (i.e. IBS, LifeTech Scientific) have the thinnest scaffold thickness, with similar support strength to other metallic scaffolds [

23]. Additionally, they are expected to reduce shear stress and thrombosis due to improved reendothelialization [

20]. These stents should be easily monitored with imaging methods for proper placement [

23].

The PLLA-based Absorb BVS and the magnesium-based DREAMS 2G are the most representative BRS devices and have similar scaffold thicknesses [

24]. Both products have been successful in humans for up to 2 years in terms of efficacy, with low rates of adverse events, primarily TLF, and restoration of vasomotion and late lumen expansion [

26,

27]. Unfortunately, increased scaffold thrombosis, higher late lumen loss, and an increased risk of target lesion revascularization have limited the use of BVSs in long-term follow-up [

5,

17]. In recent porcine models by Gao et al, iron-based BVS struts remained intact at 6 months, and corrosion was detected at 9 months. 5-year results demonstrated efficacy and safety comparable to contemporary metal-based DES without iron artifact, intra-scaffold restenosis or thrombosis, lumen collapse, aneurysm formation, and chronic inflammation [

24].

Absorb BVS (Abbott Vascular) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016. However, it was withdrawn in 2017 after scaffold thrombosis was revealed in several trials and meta-analyses and it is no longer commercially available anywhere [

28]. Although there are currently several commercial BVS products with European Conformity (CE) approval, there is no FDA approved BVS for coronary arteries [

20,

29]. It is noteworthy that Esprit BTK (Abbott Vascular) was approved by the FDA in 2024 [

30].

3. Biodegradable Stents in Coronary Arteries

BVSs were originally developed with the idea of restoring vasomotor function and reducing the risk of device thrombosis in permanent DESs. To achieve this goal, these products have been designed by combining the advantages of ensuring the effectiveness of drug-eluting stents during implantation while not leaving a foreign body behind [

19]. In this concept, BVSs initially function in terms of drug-eluting and supporting the vascular wall similarly to DES and then dissolve months to years after implantation, which may lead to the restoration of vasomotor function. Once dissolved, they allow the artery to maintain its integrity and return to its physiological properties [

17,

18,

29].

Although early reports suggested BVS were superior to DES, results from larger populations and longer-term studies have raised concerns, primarily regarding the increased risk of thrombosis, as well as major adverse cardiac events and lower radial power [

5,

17,

19].

The first data on BVS performance are from the ABSORB I study. The 5-year data from cohorts A and B of this study were reported to be promising, with no scaffold thrombosis (ScT) observed and the rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death) being 3.4% and 11%, respectively [

31,

32]. However, the ABSORB II study, a non-inferiority study for ABSORB BVS, showed that it was associated with a two-fold increased risk of TLF compared with Xience V (which is a DES, Abbott Vascular) at 3-year follow-up (10% vs 5%; p = 0.0425) [

26]. The 3-year data from the ABSORB III study also showed that ABSORB BVS was inferior to DES in terms of overall ST (2.4% vs. 0.6%) and TLF (11.7% vs. 8.1%) [

33,

34]. However, there were decreases in TLF and ScT, particularly between 3 and 5 years, compared with the 0 to 3-year time period (hazard ratios 0.83 vs. 1.35 for TLF and 0.26 vs. 3.23 for ScT, respectively). This coincides with complete scaffold resorption [

35]. The 30-day results of the ABSORB IV study revealed a lower acute device success rate (94.6% vs. 99.0%), higher risk of TLF (5.0% vs. 3.7%), and a higher ischemia-induced target vessel revascularization (ID-TVR) rate (1.2% vs. 0.2%) [

36]. In the 5-year follow-up data from the Absorb IV study, there was no significant difference in the rates of TVF and MACE between patients treated with BVS and those treated with CoCr-EES; there was also no significant difference in the rates of device thrombosis at 5 years after BVS and CoCr-EES (1.7% events vs. 1.1% events). The 5-year rates of TLF were reported to remain higher with BVS than with CoCr-EES (17.5% vs 14.5%, p=0.03), increasing slightly from 3-year follow-up [

37].

In a large-scale study with a 12-month follow-up between durable polymer drug-eluting stents (DP-DES) and biodegradable polymer drug-eluting stents (BP-DES) groups in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock, Jang et al. [

11] found no significant difference in clinical outcomes (1.3% vs. 1.6% for ScT and 34.2% vs. 28.5% for TVF, respectively). They also noted that they did not observe any effect of polymer technology on clinical outcomes. In patients with acute myocardial infarction, Iglesias et al [38) reported the primary composite endpoint of TLF was much higher in the DP-DES group than in the BP-DES group in 12-month follow-up (6% vs 4%: absolute risk difference −1.6%). During this period, the rates of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial reinfarction indicating clinically indicated target lesion revascularization, and definite stent thrombosis were similar between the two treatment groups. What is noteworthy in their study is that the frequency of TLR was much higher in the DP-DES group, emphasizing the benefits of complete polymer degradation that reduces thrombogenicity and facilitates reendothelialization. Kim et al [

39] reported that the risk of patient-oriented clinical outcomes was similar between the DP-DES and BP-DES groups (5.2% vs 6.4%: absolute risk difference −1.2%), with excellent safety and efficacy profiles at 12 months for both groups. However, when the risk of device-driven clinical outcomes was assessed, there was a slight increase in the incidence of TLR in the BP-DES group (2.6% vs 3.9%: hazard ratio, 0.67). The researchers attributed this to the properties of BP-DESs to resemble bare metal stents after polymer degradation, thus increasing the risk of late restenosis. The EVERBIO-2 trial comparing BVS and DES revealed that rates of clinical device-oriented composite events (29% vs 28%, respectively) and patient-oriented composite events (49% vs 55%, respectively, p=0.43) were not statistically significant between two groups at 10-year follow-up. On the other hand, DES was superior for some individual outcomes. For instance, the rate of target vessel myocardial infarction was 5% in the BVS group and 0% in the DES group, and the rate of possible stent thrombosis was 3% and 0% in the BVS and DES groups, respectively [

17].

4. Biodegradable Stents in Peripheral Arteries

Stents play an important role in interventional therapy not only in cardiovascular diseases but also in peripheral arterial diseases, which affect more than 230 million people [

36]. The off-label use of coronary drug-eluting stents in PAD has been a glimmer of hope [

5]. However, in below-knee lesions, BMSs failed to prove superiority over angioplasty. DES was only successful in short lesions (<40 mm), and usually two or more stents need to be used [

40,

41]. Additionally, permanent stents resulted in higher rates of in-stent restenosis (ISR), making them harder to re-channelize or re-dilate [

42].

Although polymer-based BVSs have been found to be sufficient for the patency of short lesions in the infrapopliteal artery, their use has been limited due to their shorter length and larger support thickness [

43]. Although iron-based BVSs show better radial strength, pure iron generally has significant disadvantages such as slow corrosion and bio-resorption [

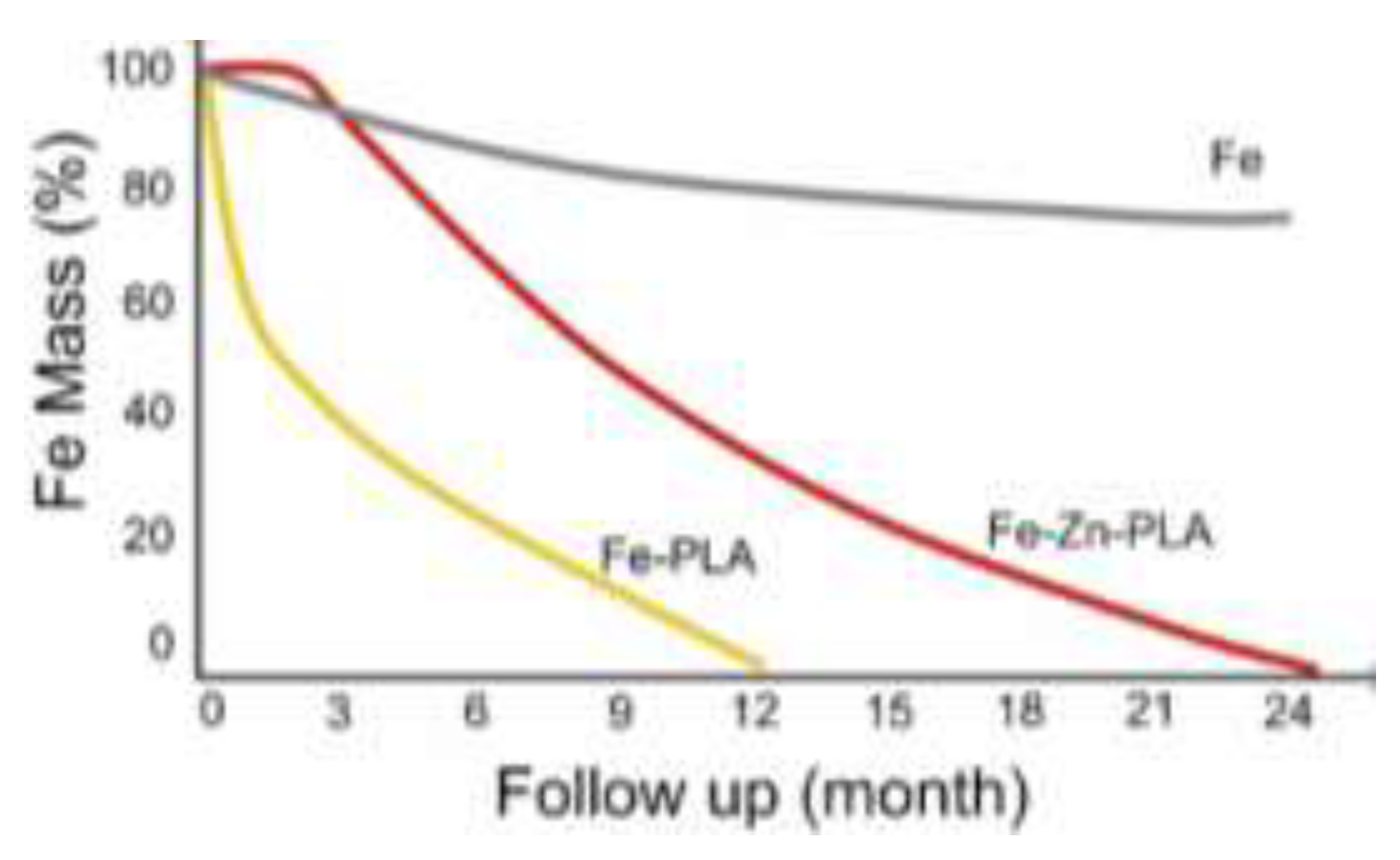

44]. Zhang et al. [

5] used long biodegradable sirolimus-eluting stents (LBSs) with nitrided and PLA coated ironin BTK lesions, which have a higher fragility than other lower extremity vascular segments.. They reported that LBSs with 70 μm support thickness and lengths up to 118 mm were safe and feasible according to 13-month follow-up results. They also reported that proper iron nitriding improved the mechanical performance of the metal, while PLA coating accelerated its degradation (

Figure 2)[

5,

44].

The LIFE-BTK (pivotaL Investigation of saFety and Efficacy of drug-eluting resorbable scaffold treatment-Below The Knee) trial, is an RCT designed to prospectively evaluate the premarket evaluation of Esprit BTK drug-eluting absorbable scaffold (Abbott Vascular) for the treatment of patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) and infrapopliteal artery disease. Initial results have revealed that the LIFE-BTK is superior to angioplasty in the primary efficacy endpoint for BTK lesions (74% vs 44%: 95% CI, p<0.001) at 1-year follow-up. Additionionally, the primary safety endpoint (freedom from major adverse limb events and perioperative death at 6 months) was non-inferior to angioplasty (with an absolute difference of -3 percentage points: 95% CI, p<0.001) [

40]. In 2024, Esprit BTK was approved by the FDA for BTK, and currently, it is the only BVS approved by the FDA worldwide [

28]. This approval perhaps keeps the hope of the bioresorbable scaffold concept alive.

5. Future Perspective

Although BVSs have various advantages, they also face some difficulties. First, they exhibit insufficient mechanical strength. Second, the degradation time of the stent is not always compatible with that of vascular remodeling. Finally, the implantation method presents challenges for some diseased areas [

21].

Good mechanical properties and stent stability until intima formation in the neovascularization wall are sought in an ideal stent. However, current BVSs generally have disadvantages of stent thickness and scaffold disintegration, leading to stent thrombosis [

45]. Therefore, BVSs need to have mechanical properties that perform at least as well as DES in the short term and better than DES in the long term. Additionally, the use of technologies such as 3D printing as a manufacturing technique opens the door to patient-specific devices that can meet the precise requirements of each individual. When these ideal characteristics are achieved, challenges such as immunogenicity, inflammation, fibrous tissue formation, material degradation, and cytotoxicity can be addressed more easily.

Stents that can locally deliver anti-coagulant or anti-inflammatory drugs will provide significant benefits in terms of greater efficacy and reduced off-target effects. The stent should also be visible for monitoring during and after the intervention. Finally, smart stents that are easy to deploy and adapt well to the target could prevent restenosis while simultaneously offering the ability to monitor post-implantation outcomes.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Although the comparison of DP-DES with BP-DES showed contradictory results, overall, DP-DES was not inferior to BP-DES in terms of TVF, and no additional clinical benefit was observed from BP-DES compared to DP-DES during the follow-up periods [

46]. On the other hand, in some studies, the high adverse event rates of BVS have been attributed to the inadequate mechanical properties of the first-generation scaffold and the inadequate implantation technique. Bengueddache et al [

17] analyzed the EverBio-2 study over a 10-year follow-up, which was the first published evaluation over 10 years on BVS. They noted that the initial analysis showed comparable clinical outcomes for DESs and BVSs at 9 months, followed by subsequent studies showing no significant difference in clinical outcomes at 2 and 5 years. They also found that over 10 years, device-oriented composite events and patient-oriented composite events rates were similar between the BVS and DES groups. When looking at individual adverse events, possible stent thrombosis was found to be higher in the BVS group after 10 years. These researchers also evaluated the results of other notable studies on BVS, such as ABSORB-JAPAN, ABSORB-III, and ABSORB-IV. In these studies, the 5-year stent thrombosis rate ranged from 1% to 3.8% in the BVS groups. This rate was significantly higher than in the DES group only in the ABSORB-III study comparing the Everolimus eluting stent group (BVS = 2.5%, EES = 1.1%; p = 0.03) [

17].

It was suggested that the situation would improve with enhancements in these features [

16,

37]. In this regard, the development of thinner struts, improved placement technique and the ideal period of disintegration in the human body (especially for iron scaffolds) may reduce shear stress and thrombosis, resulting in improved reendothelialization [

5,

20].

Based on current experience, it is not recommended to implant BVSs in vessels with reference vessel diameters <2.25 mm and >3.75 mm. This is because BVSs tend to have thicker and wider scaffolds, increasing the risk of ScT [

23]. Although iron-based scaffolds are thinner and more durable, they take longer to corrode completely, up to 5-6 years [

44].

When comparing the advantages and disadvantages of DES and BVS, DES offers benefits in terms of stent thrombosis, strut thickness and dismantling. On the other hand, DESs have potential drawbacks compared to BVSs in terms of late and very late stent thrombosis, very late strut fracture and neoatherosclerosis [

20].

The strut thickness of Absorb (>150 μm) resulted in greater luminal protrusion and turbulent flow, delayed reendothelialization, and increased neointimal hyperplasia. Thinner BVS scaffolds with superior mechanical performance are expected to offer potential improvement [

16]. Firesorb (MicroPort) BRS is a thinner-supported (100-125 μm) PLLA-based sirolimus-eluting BRS designed to reduce luminal protrusion and enhance blood flow dynamics. This product demonstrated nearly the same 1-year angiographic intra-segment late loss and tissue srut coverage as CoCr-EES without scaffold thrombosis in the FUTURE-II randomized trial [

47]. Esprit, a PLLA-based scaffold, has a support thickness of <100 μm and has been approved by the FDA for BTK based on favorable results [

16,

28]. Preclinical evaluations of the iron-based BVS scaffold with a support thickness of 70 μm showed promising results [

24,

48]. It is recommended that BRS be implanted under intravascular imaging guidance, as BRS failure has been largely attributed to suboptimal implantation technique in addition to thick strut [

49]. Ali et al and Cassese et al conducted two different meta-analysis studies comparing BVS and DES. Ali et al. [

50] found that BVS resulted in higher 3-year TLF rates compared with CoCr-EES (11.7% vs 8.1%; RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.10-1.73; P=0.006). Similarly, results from the study by Cassese et al. [

51] showed a higher risk of TLF in BVS compared with EES (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.11-1.65; p=0.0028). The higher rates in the BVS group were mainly due to target vessel myocardial infarction in both groups. Both studies also reported higher rates of ScT in the BVS group. In contrast, Lu et al.'s [

52] meta-analysis with 5-year follow-up found that BP-BES was associated with lower rates of TLR (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.62-0.96) and ScT (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.84) and MACE (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71-0.97).

In conclusion, the superiority of BVS over DES has not been demonstrated in a randomized trial, and DES devices are still the first choice for most arterial disease cases. These results have drawn significant attention to the safety of BTSs, leading to a decrease in the initial appeal of BVSs. Late scaffold thrombosis is the main adverse event and the ongoing limitation of their preference. The FDA's approval of Esprit BTK for use in below-knee lesions may be a promising light for the use of BVS in other vascular events.

The decrease in scaffold thrombosis rates observed simultaneously with the complete resorption of BVS and the reduction in the risk of early BVS by improving the scaffold design and placement technique may be important guiding data to produce refined new BVSs. To further elucidate the usability of BVSs, future large-scale and longer-follow-up comparative studies are needed to assess their effectiveness and safety.

Author Contributions

Rasit Dinc: Designed, conceptualized, wrote, and finalized the article. Evren Ekingen: supervised, re-reviewed, interpreted and designed.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Competing Interest

RD is the president of Invamed Company (Ankara, Turkey). EE has no conflict of interest.

References

- Aliman O, Ardic AF (2023) The Usability, Safety, Efficacy and Positioning of the Atlas Drug-Eluting Coronary Stent: Evaluation the Preliminary Perioperative Results. RRJ Pharm Pharm Sci 12:002. [CrossRef]

- Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1329-1340. [CrossRef]

- Kohn CG, Alberts MJ, Peacock WF, Bunz TJ, Coleman CI. Cost and inpatient burden of peripheral artery disease: Findings from the National Inpatient Sample. Atherosclerosis. 2019;286:142-146. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal J, Serruys PW. Revascularization strategies for patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Intern Med. 2014;276(4):336-51. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Gao X, Zhang H, et al. Maglev-fabricated long and biodegradable stent for interventional treatment of peripheral vessels. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7903. [CrossRef]

- Burzotta F, Brancati MF, Trani C, et al. INtimal hyPerplasia evAluated by oCT in de novo COROnary lesions treated by drug-eluting balloon and bare-metal stent (IN-PACT CORO): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:55. [CrossRef]

- Dinc R, Yerebakan H. Atlas Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents Inhibit Neointimal Hyperplasia in Sheep Modeling. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2024;40(5):585-594. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa G, Finn AV, Vorpahl M, Ladich ER, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Coronary responses and differential mechanisms of late stent thrombosis attributed to first-generation sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(4):390-398. [CrossRef]

- Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Kitrou P, Krokidis M, Karnabatidis D. Response to Letter by Bonassi on Article, "Risk of Death Following Application of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons and Stents in the Femoropopliteal Artery of the Leg: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(10):e012172. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa G, Finn AV, Joner M, et al. Delayed arterial healing and increased late stent thrombosis at culprit sites after drug-eluting stent placement for acute myocardial infarction patients: an autopsy study. Circulation. 2008;118(11):1138-1145. [CrossRef]

- Jang WJ, Park IH, Oh JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of durable versus biodegradable polymer drug-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6301. [CrossRef]

- Scafa Udriște A, Niculescu AG, Grumezescu AM, Bădilă E. Cardiovascular Stents: A Review of Past, Current, and Emerging Devices. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(10):2498. [CrossRef]

- Dola J, Morawiec B, Muzyk P, Nowalany-Kozielska E, Kawecki D. Ideal coronary stent: Development, characteristics, and vessel size impact. Ann. Acad. Med. Silesiensis 2020;74:191–197. [CrossRef]

- Watson T, Webster MWI, Ormiston JA, Ruygrok PN, Stewart JT. Long and short of optimal stent design. Open Heart. 2017 Oct 30;4(2):e000680. [CrossRef]

- Blake Y. Biocompatible materials for cardiovascular stents. Zenodo. 2020;1:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Stone GW, Biensock SW, Neumann FJ. Bioresorbable coronary scaffolds are ready for a comeback: pros and cons. EuroIntervention. 2023;19(3):199-202. [CrossRef]

- Bengueddache S, Cook M, Lehmann S, et al. Ten-year clinical outcomes of everolimus- and biolimus-eluting coronary stents vs. everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffolds-insights from the EVERBIO-2 trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1426348. [CrossRef]

- Revathi K, Swathilakshmi U, Shailaja P, Ratna JV, Daniel BA. A Review on Coronary Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold System. Journal of Cardiology & Cardiovascular Therapy. 2017;6(3):128-33. [CrossRef]

- Jeżewski MP, Kubisa MJ, Eyileten C, et al. Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffolds-Dead End or Still a Rough Diamond?. J Clin Med. 2019;8(12):2167. [CrossRef]

- Leesar MA, Feldman MD. Thrombosis and myocardial infarction: the role of bioresorbable scaffolds. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2023;3(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Yu X, Cui J, et al. Development of Biodegradable Polymeric Stents for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomolecules. 2022;12(9):1245. [CrossRef]

- Mostaed E, Sikora-Jasinska M, Ardakani MS, et al. Towards revealing key factors in mechanical instability of bioabsorbable Zn-based alloys for intended vascular stenting. Acta Biomater. 2020;105:319-335. [CrossRef]

- Peng X, Qu W, Jia Y, Wang Y, Yu B, Tian J. Bioresorbable Scaffolds: Contemporary Status and Future Directions. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:589571. [CrossRef]

- Gao YN, Yang HT, Qiu ZF, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety and biocompatibility of a novel sirolimus eluting iron bioresorbable scaffold in a porcine model. Bioact Mater. 2024;39:135-146. Published 2024 May 18. [CrossRef]

- Räber L, Brugaletta S, Yamaji K, et al. Very Late Scaffold Thrombosis: Intracoronary Imaging and Histopathological and Spectroscopic Findings. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(17):1901-1914. [CrossRef]

- O'Riordan M. FDA Approves Bioresorbable Scaffold for BTK Lesions. Daily News (April 29, 2024). Available at: https://www.tctmd.com/news/fda-approves-bioresorbable-scaffold-btk-lesions#:~:text=The%20US%20Food%20and%20Drug,announcement%20today%20from%20manufacturer%20Abbott.

- Sabaté M, Alfonso F, Cequier A, et al. Magnesium-Based Resorbable Scaffold Versus Permanent Metallic Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The MAGSTEMI Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2019;140(23):1904-1916. [CrossRef]

- Capodanno D. Bioresorbable Scaffolds in Coronary Intervention: Unmet Needs and Evolution. Korean Circ J. 2018;48(1):24-35. [CrossRef]

- FDA. Premarket Approval (PMA). (September 23, 2024) Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P230036.

- Onuma Y, Dudek D, Thuesen L, et al. Five-year clinical and functional multislice computed tomography angiographic results after coronary implantation of the fully resorbable polymeric everolimus-eluting scaffold in patients with de novo coronary artery disease: the ABSORB cohort A trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(10):999-1009. [CrossRef]

- Serruys PW, Ormiston J, van Geuns RJ, et al. A Polylactide Bioresorbable Scaffold Eluting Everolimus for Treatment of Coronary Stenosis: 5-Year Follow-Up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Feb 23;67(7):766-76. [CrossRef]

- Serruys PW, Chevalier B, Sotomi Y, et al. Comparison of an everolimus-eluting bioresorbable scaffold with an everolimus-eluting metallic stent for the treatment of coronary artery stenosis (ABSORB II): a 3 year, randomised, controlled, single-blind, multicentre clinical trial. 2017 Feb 25;389(10071):804. [CrossRef]

- Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Metzger C, et al. 3-Year Clinical Outcomes With Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Coronary Scaffolds: The ABSORB III Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(23):2852-2862. [CrossRef]

- Ali ZA, Serruys PW, Kimura T, et al. 2-year outcomes with the Absorb bioresorbable scaffold for treatment of coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven randomised trials with an individual patient data substudy. Lancet. 2017;390(10096):760-772. [CrossRef]

- Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Metzger DC, et al. Clinical Outcomes Before and After Complete Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Scaffold Resorption: Five-Year Follow-Up From the ABSORB III Trial. Circulation. 2019;140(23):1895-1903. [CrossRef]

- Stone GW, Ellis SG, Gori T, et al. Blinded outcomes and angina assessment of coronary bioresorbable scaffolds: 30-day and 1-year results from the ABSORB IV randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1530-1540. [CrossRef]

- Stone GW, Kereiakes DJ, Gori T, et al. 5-Year Outcomes After Bioresorbable Coronary Scaffolds Implanted With Improved Technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(3):183-195. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias JF, Muller O, Heg D, et al. Biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stents versus durable polymer everolimus-eluting stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (BIOSTEMI): a single-blind, prospective, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10205):1243-1253. [CrossRef]

- Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al. Durable Polymer Versus Biodegradable Polymer Drug-Eluting Stents After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: The HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS Trial. Circulation. 2021;143(11):1081-1091. [CrossRef]

- Varcoe RL, DeRubertis BG, Kolluri R, et al. Drug-Eluting Resorbable Scaffold versus Angioplasty for Infrapopliteal Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(1):9-19. [CrossRef]

- Spreen MI, Martens JM, Knippenberg B, et al. Long-Term Follow-up of the PADI Trial: Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Versus Drug-Eluting Stents for Infrapopliteal Lesions in Critical Limb Ischemia. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(4):e004877. [CrossRef]

- Varcoe RL, Paravastu SC, Thomas SD, Bennett MH. The use of drug-eluting stents in infrapopliteal arteries: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int Angiol. 2019;38(2):121-135. [CrossRef]

- Dia A, Venturini JM, Kalathiya RJ, et al. Two-year follow-up of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds in severe infra-popliteal arterial disease. Vascular. 2021;29(3):355-362. [CrossRef]

- Joner M, Klosterman G, Byrne RA. Novel bioresorbable scaffolds and lessons from recent history. EuroIntervention. 2023;19(3):193-195. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto A, Jinnouchi H, Torii S, Virmani R, Finn AV. Understanding the Impact of Stent and Scaffold Material and Strut Design on Coronary Artery Thrombosis from the Basic and Clinical Points of View. Bioengineering (Basel). 2018;5(3):71. [CrossRef]

- Buccheri S, James S, Lindholm D, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes of bioabsorbable vs. permanent polymer drug-eluting stents in Sweden: a report from the Swedish Coronary and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). Eur Heart J. 2019;40(31):2607-2615. [CrossRef]

- Song L, Xu B, Chen Y, et al. Thinner Strut Sirolimus-Eluting BRS Versus EES in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: FUTURE-II Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(13):1450-1462. [CrossRef]

- Zheng JF, Xi ZW, Li Y, et al. Long-term safety and absorption assessment of a novel bioresorbable nitrided iron scaffold in porcine coronary artery. Bioact Mater. 2022;17:496-505. Published 2022 Jan 11. [CrossRef]

- Leesar MA, Feldman MD. Thrombosis and myocardial infarction: the role of bioresorbable scaffolds. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2023;3(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Ali ZA, Gao R, Kimura T, et al. Three-Year Outcomes With the Absorb Bioresorbable Scaffold: Individual-Patient-Data Meta-Analysis From the ABSORB Randomized Trials. Circulation. 2018;137(5):464-479. [CrossRef]

- Cassese S, Byrne RA, Jüni P, et al. Midterm clinical outcomes with everolimus-eluting bioresorbable scaffolds versus everolimus-eluting metallic stents for percutaneous coronary interventions: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. EuroIntervention. 2018;13(13):1565-1573. [CrossRef]

- Lu P, Lu S, Li Y, Deng M, Wang Z, Mao X. A comparison of the main outcomes from BP-BES and DP-DES at five years of follow-up: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14997. Published 2017 Nov 3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).