Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Development of an intelligent system dedicated to monitoring occupant stress and identifying stress levels in smart building environments using an FL approach.

- Introduction of a lightweight, edge-deployable ANN-based stress level recognition system, suitable for real-time applications, integrating wearable sensors to gather diverse health parameters.

- Evaluation of the proposed method on the SaYoPillow dataset, specifically developed for stress level classification tasks.

- Demonstration of high effectiveness, achieving an impressive accuracy rate of 99.95%, precision rate of 99.95%, recall of 99.93%, F1-score of 99.94%, a minimal loss value of 0.0019%, and low communication cost of 0.08Mb.

2. Federated Learning

2.1. Horizontal FL

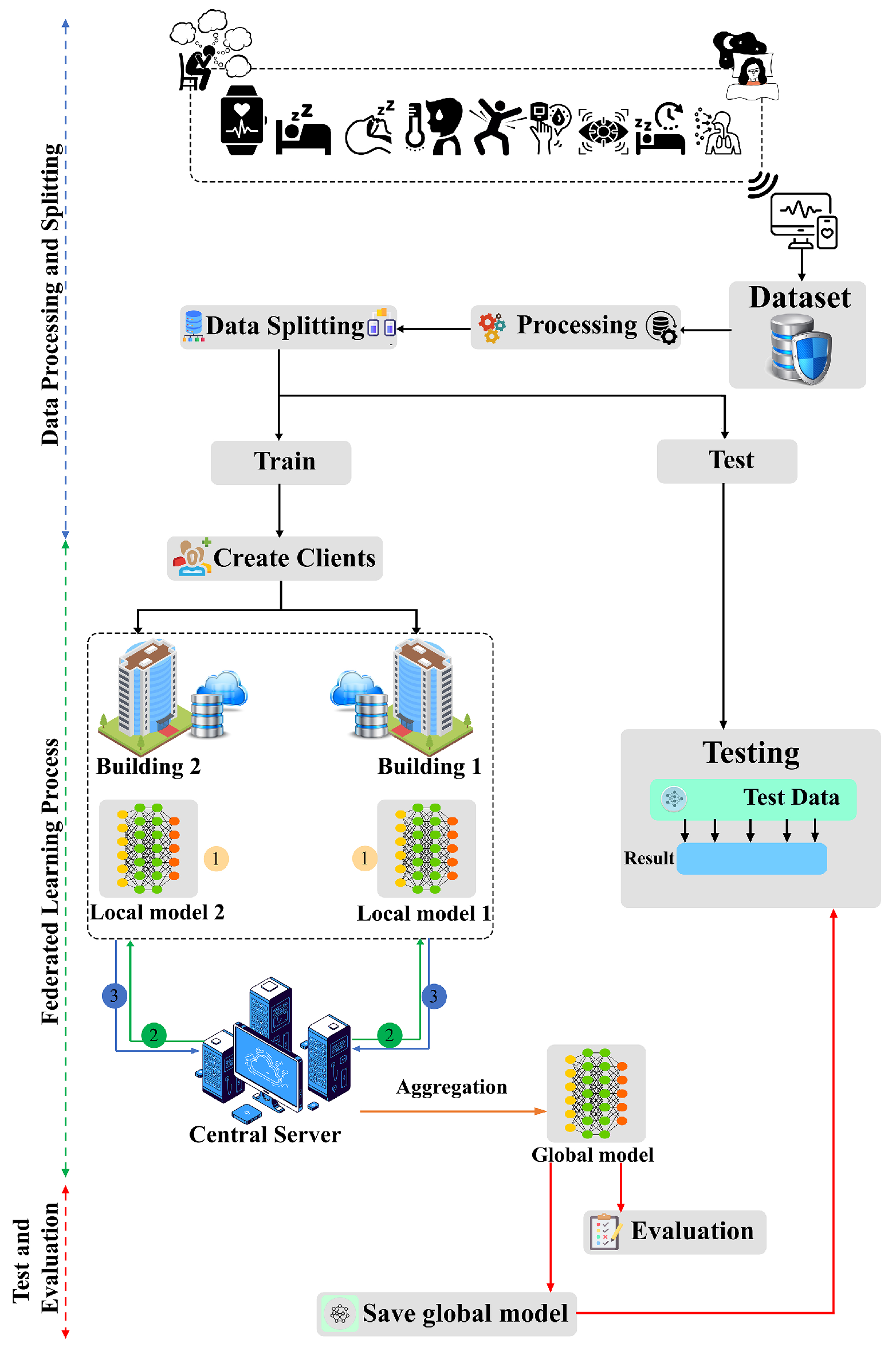

3. Proposed Methodology

3.1. Data Processing

3.2. Create Clients

3.3. Central Server

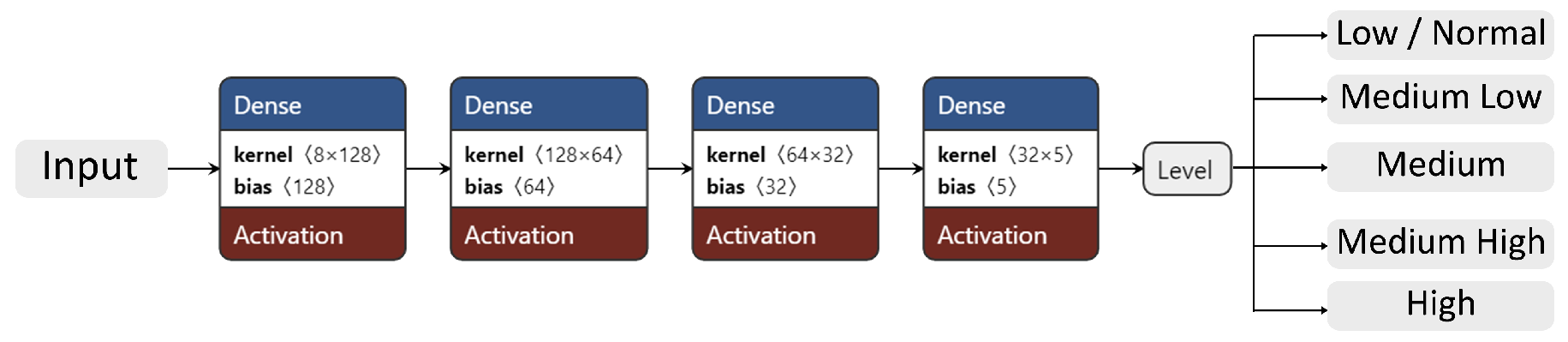

3.4. Local Model

3.5. Aggregation

4. Experimentation and Result Discussion

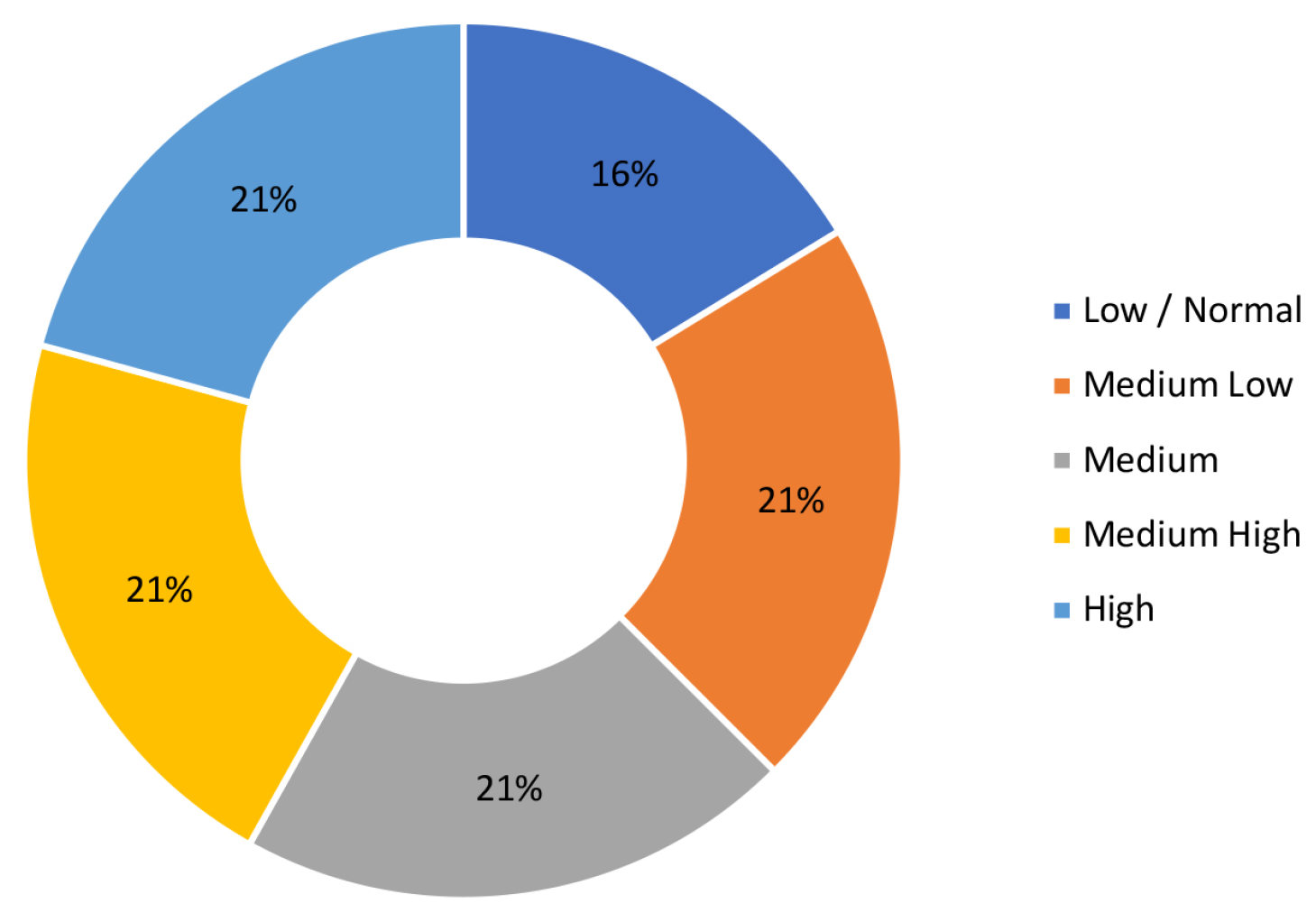

4.1. Dataset

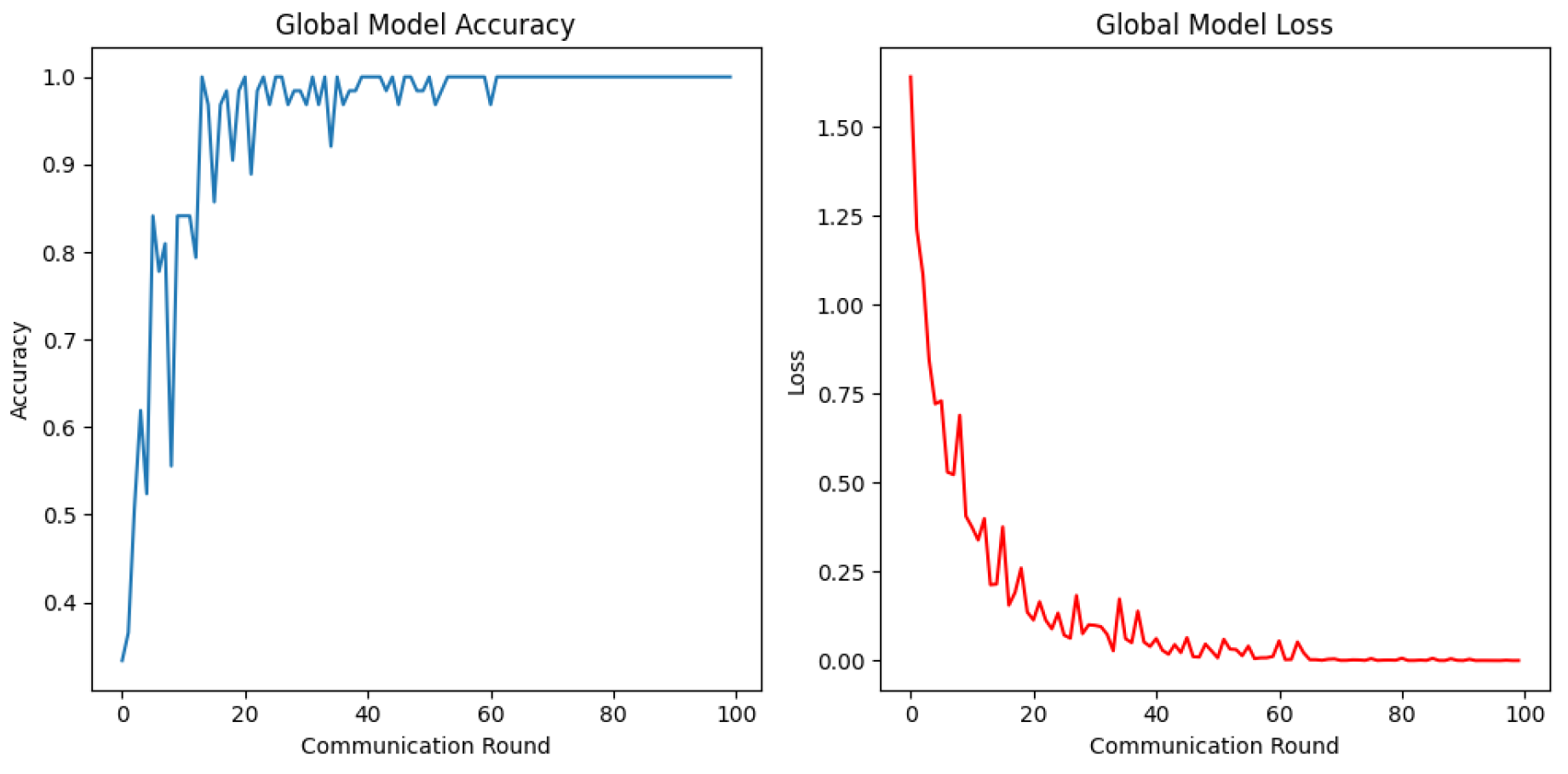

4.2. Accuracy and Loss Graph

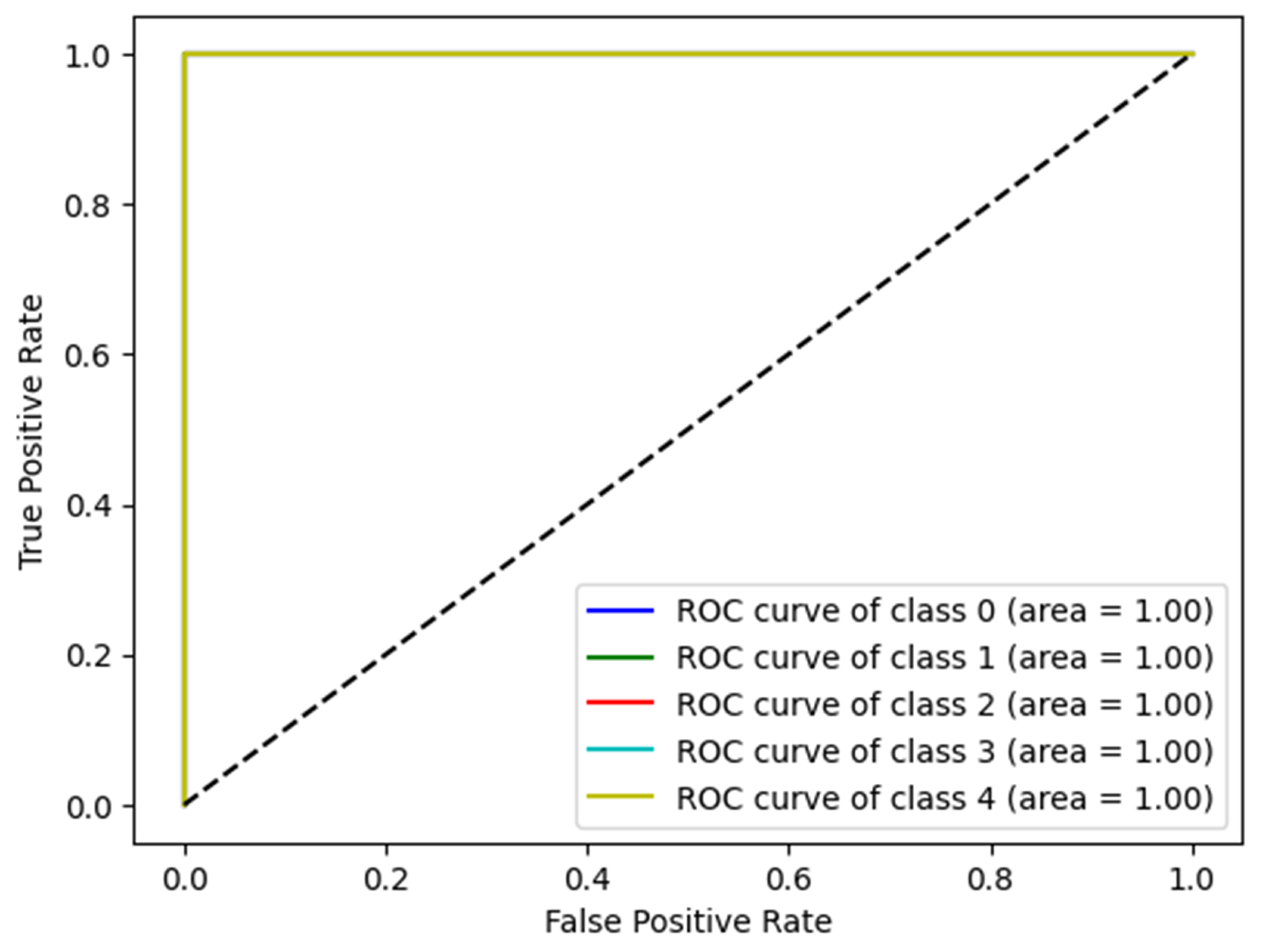

4.3. Roc curve

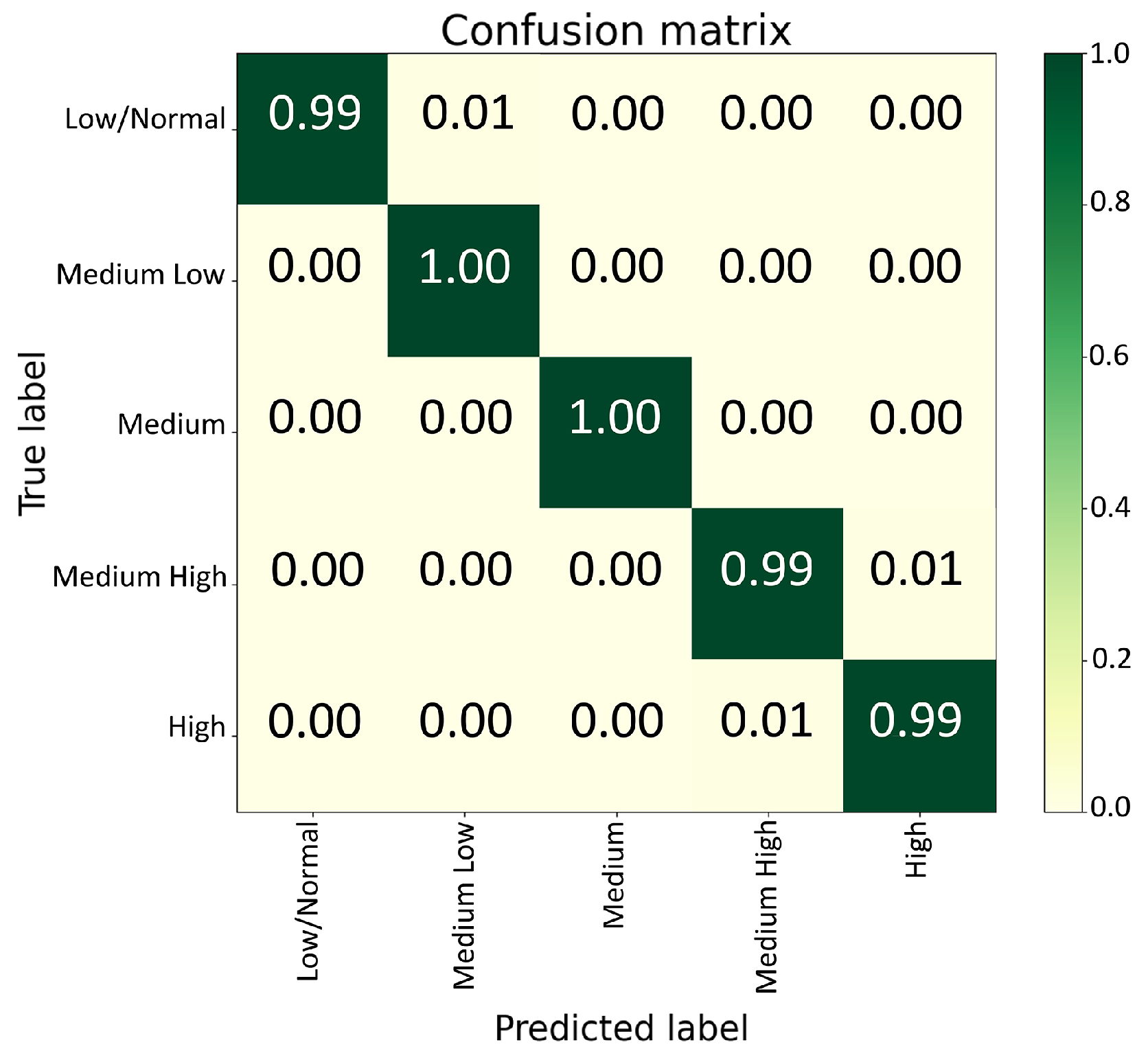

4.4. Confusion Matrix

4.5. Model Performance Across Clients

4.6. Comparison with New Related Works

| Work | Year | Model | Aggregation | Loss (%) | Accuracy (%) | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32] | 2024 | Naive Bayes | ✗ | ✗ | 91.27 | SaYoPillow |

| [33] | 2023 | FFNN | ✗ | ✗ | 99.90 | SaYoPillow |

| [34] | 2024 | ML | ✗ | ✗ | 99.50 | SaYoPillow |

| [35] | 2023 | KNN RF | ✗ | ✗ | 99.00 | SaYoPillow |

| [36] | 2024 | Decision Tree | ✗ | ✗ | 93.27 | SaYoPillow |

| [10] | 2020 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 96.00 | SaYoPillow |

| [37] | 2023 | RF | ✗ | ✗ | 97.63 | SaYoPillow |

| Our | 2024 | ANN | ✗ | 0.13 | 99.97 | SaYoPillow |

| Our | 2024 | FedWell | FedAvg | 0.0019 | 99.95 | SaYoPillow |

5. Conclusion

References

- Medikonda, J.; others. A clinical and technical methodological review on stress detection and sleep quality prediction in an academic environment. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2023, 235, 107521. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Li, K.; Liao, X.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, N. Real-time detection of acute cognitive stress using a convolutional neural network from electrocardiographic signal. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 42710–42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Elnour, M.; Fadli, F.; Meskin, N.; Petri, I.; Rezgui, Y.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A. AI-big data analytics for building automation and management systems: a survey, actual challenges and future perspectives. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 4929–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahoon, J.L.; Garcia, L.A. Continuous Stress Monitoring for Healthcare Workers: Evaluating Generalizability Across Real-World Datasets. Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Chouchane, A.; Bessaoudi, M.; Boutellaa, E.; Ouamane, A. A new multidimensional discriminant representation for robust person re-identification. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2023, 26, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammari, M.; Chouchane, A.; Ouamane, A.; Bessaoudi, M. ; others. Kinship Verification Using Multiscale Retinex Preprocessing and Integrated 2DSWT-CNN Features. 2024 8th International Conference on Image and Signal Processing and their Applications (ISPA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Sadruddin, S.; Khairnar, V.D.; Vora, D.R. Issues and Challenges in Detecting Mental Stress from Multimodal Data Using Machine Intelligence. SN Computer Science 2024, 5, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchane, A. Analyse d’images d’expressions faciales et orientation de la tête basée sur la profondeur. PhD thesis, Université Mohamed Khider-Biskra, 2016.

- Chouchane, A.; Belahcene, M.; Ouamane, A.; Bourennane, S. 3D face recognition based on histograms of local descriptors. 2014 4th International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA). IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–5.

- Rachakonda, L.; Bapatla, A.K.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E. SaYoPillow: Blockchain-integrated privacy-assured IoMT framework for stress management considering sleeping habits. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2020, 67, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, R.; Gunanandhini, S.; Srikanth, G.U.; Sujatha, V. Human Stress Detection in and Through Sleep Patterns Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series B 2024, pp. 1–23.

- Chouchane, A.; Ouamane, A.; Himeur, Y.; Mansoor, W.; Atalla, S.; Benzaibak, A.; Boudellal, C. Improving CNN-based Person Re-identification using score Normalization. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2890–2894.

- Khammari, M.; Chouchane, A.; Bessaoudi, M.; Ouamane, A.; Himeur, Y.; Alallal, S.; Mansoor, W. ; others. Enhancing kinship verification through multiscale retinex and combined deep-shallow features. 2023 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 178–183.

- Harshini, V.; Kuresan, H.; Kancharlawar, O.; Madhan, V.; Balamithra, S. Human Stress Detection in and through Sleep using Machine Learning. 2024 International Conference on Recent Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Ubiquitous Communication, and Computational Intelligence (RAEEUCCI). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–7.

- Bessaoudi, M.; Belahcene, M.; Ouamane, A.; Chouchane, A.; Bourennane, S. A novel hybrid approach for 3d face recognition based on higher order tensor. Advances in Computing Systems and Applications: Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Computing Systems and Applications 3. Springer, 2019, pp. 215–224.

- Chouchane, A.; Bessaoudi, M.; Ouamane, A.; Laouadi, O. Face kinship verification based vgg16 and new gabor wavelet features. 2022 5th International Symposium on Informatics and its Applications (ISIA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Bessaoudi, M.; Chouchane, A.; Ouamane, A.; Boutellaa, E. Multilinear subspace learning using handcrafted and deep features for face kinship verification in the wild. Applied Intelligence 2021, 51, 3534–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammari, M.; Chouchane, A.; Ouamane, A.; Bessaoudi, M.; Himeur, Y.; Hassaballah, M.; others. High-order knowledge-based discriminant features for kinship verification. Pattern Recognition Letters 2023, 175, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Berkani, M.R.A.; Chouchane, A.; Himeur, Y.; Ouamane, A.; Amira, A. An Intelligent Edge-Deployable Indoor Air Quality Monitoring and Activity Recognition Approach. 2023 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 184–189. [CrossRef]

- Rebiai, M.; Berkani, M.R.A.; Bentegri, M.Y.; Seghir, M.T. Mathematical Morphology-Based Envelope Detection for Cardiac Disease Classification from Phonocardiogram Signals. 2024 8th International Conference on Image and Signal Processing and their Applications (ISPA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Varlamis, I.; Sardianos, C.; Chronis, C.; Dimitrakopoulos, G.; Himeur, Y.; Alsalemi, A.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A. Using big data and federated learning for generating energy efficiency recommendations. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 2023, 16, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Varlamis, I.; Kheddar, H.; Amira, A.; Atalla, S.; Singh, Y.; Bensaali, F.; Mansoor, W. Federated learning for computer vision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.13558 2023.

- Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Tse, M.; Lin, K.Y. A review of applications in federated learning. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 149, 106854. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, P.; Chiaro, D.; Guzzo, A.; Ianni, M.; Fortino, G.; Piccialli, F. Model aggregation techniques in federated learning: A comprehensive survey. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhang, W. A survey on federated learning: challenges and applications. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2023, 14, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronis, C.; Varlamis, I.; Himeur, Y.; Sayed, A.N.; Al-Hasan, T.M.; Nhlabatsi, A.; Bensaali, F.; Dimitrakopoulos, G. A survey on the use of Federated Learning in Privacy-Preserving Recommender Systems. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2024.

- Ammar, C.; Mebarka, B.; Abdelmalik, O.; Salah, B. Evaluation of histograms local features and dimensionality reduction for 3D face verification. Journal of information processing systems 2016, 12, 468–488. [Google Scholar]

- Chouchane, A.; Ouamanea, A.; Himeur, Y.; Amira, A. ; others. Deep Learning-Based Leaf Image Analysis for Tomato Plant Disease Detection and Classification. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 2923–2929.

- Belahcene, M.; Chouchane, A.; Mokhtari, N. 2D and 3D face recognition based on IPC detection and patch of interest regions. 2014 International Conference on Connected Vehicles and Expo (ICCVE). IEEE, 2014, pp. 627–628.

- Bengherbia, B.; Berkani, M.R.A.; Achir, Z.; Tobbal, A.; Rebiai, M.; Maazouz, M. Real-Time Smart System for ECG Monitoring Using a One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network. 2022 International Conference on Theoretical and Applied Computer Science and Engineering (ICTASCE). IEEE, 2022, pp. 32–37.

- Belahcene, M.; Chouchane, A.; Benatia, M.A.; Halitim, M. 3D and 2D face recognition based on image segmentation. 2014 International Workshop on Computational Intelligence for Multimedia Understanding (IWCIM). IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–5.

- Papishetti, S.; Kain, B.; Narayana, G. Stress Detection Based on Human Sleep Cycle. MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2024, Vol. 392, p. 01073.

- Altaf, H.; Yadav, P.K. Human Stress Detection in and through Sleep–A Deep Learning Approach. 2023 International Conference on Next Generation Electronics (NEleX). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Singh, K.K.; Mahapatra, M.; Dixit, G.K. Stress prediction through sleep parameters using a feature engineering approach. 2024 4th International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Jeelani, E. Detection Of Stress And Its Levels Through Sleep Using AI. Tuijin Jishu/Journal of Propulsion Technology 2023, 44, 1549–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, S. HUMAN STRESS LEVEL IDENTIFICATION USING MACHINE LEARNING ALGORITHMS BASED ON SLEEPING PATTERNS. INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT 2024, 08, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Islam, A.M.; Miah, J.; Ahmad, S.; Mamun, M. sleepWell: Stress Level Prediction Through Sleep Data. Are You Stressed? 2023 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT). IEEE, 2023, pp. 0229–0235.

| No of Client | Accuracy | Recall | F1-Score | Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 99.95% | 99.93% | 99.94% | 0.0019% |

| 3 | 99.94% | 99.93% | 99.93% | 0.0021% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).