Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

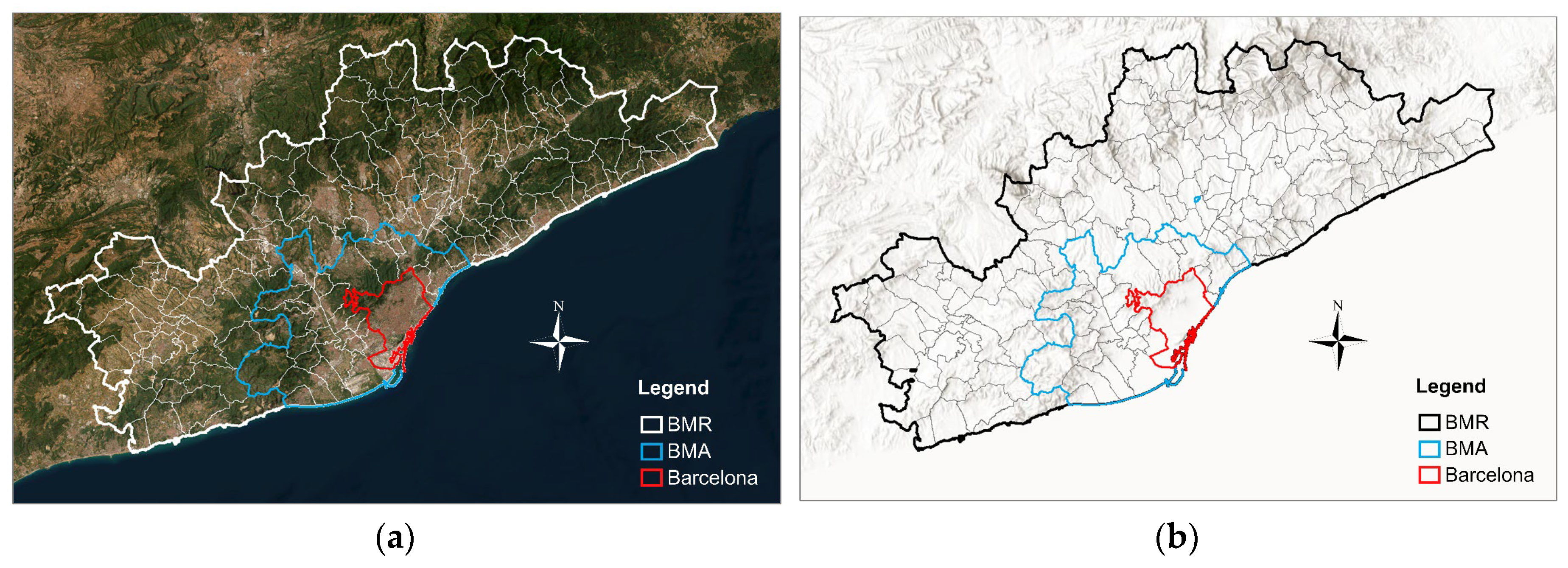

2.1. The Field of Study

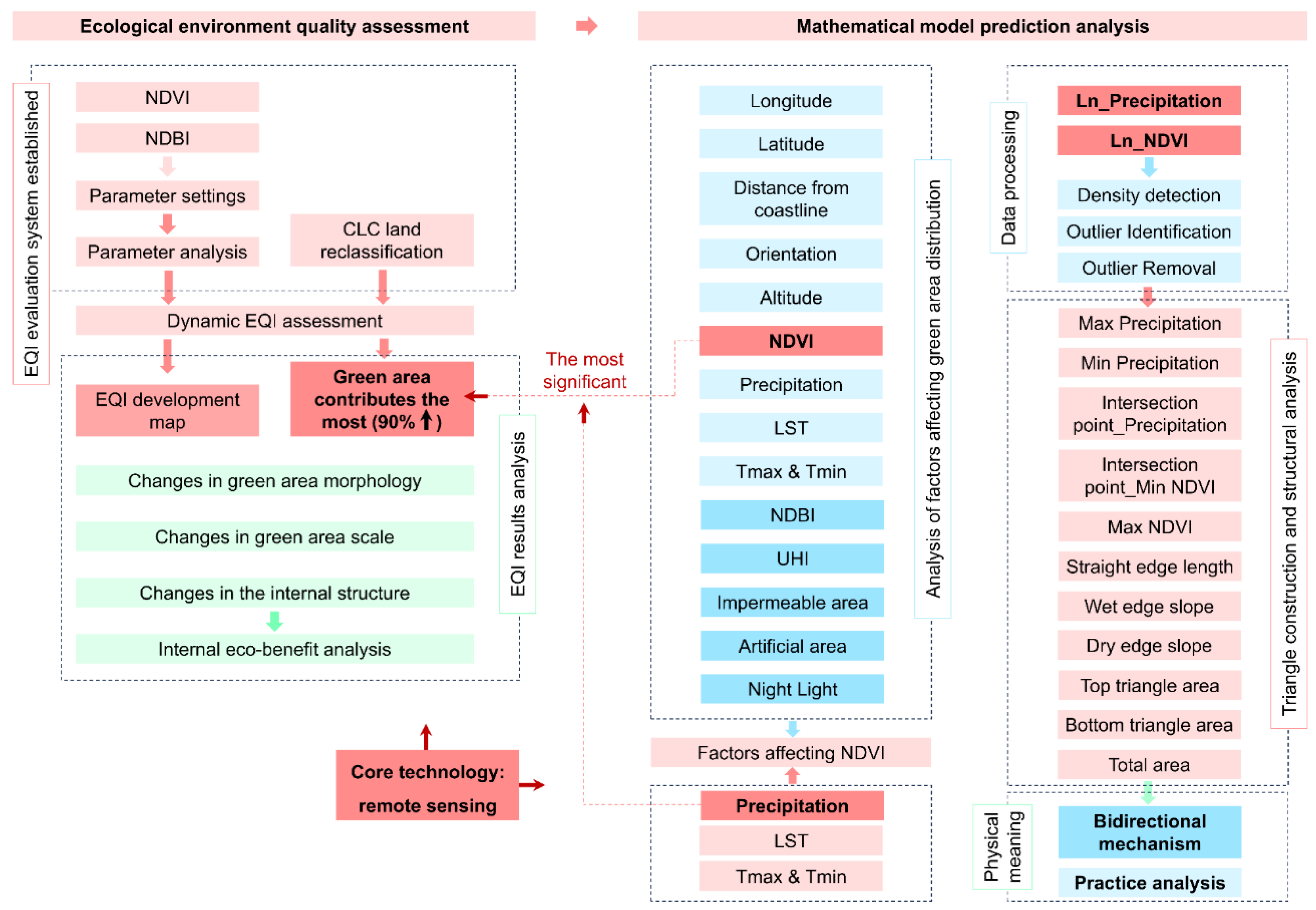

2.2. Methodology

- First of all, evaluate the Ecological Environment Quality Index (EQI) of BMR. We try to find a more scientific and reasonable indicator system to evaluate the ecological environment quality of metropolises, which can adapt to changes in time and the evaluated regions. To complete this evaluation, we need to achieve the following aspects.

- For the convenience of analysis, we classified the land use coverage of BMR according to the land type classification of CLC.

- Then, we extracted the difference (NDVIaverage-NDBIaverage) of the annual average values of NDVI and NDBI for each type of land in 2006, 2012 and 2018 after reclassification. The MODIS_MOD13Q1 (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v006/) dataset provides relevant remote sensing image data with a resolution of 250 meters.

- Set EQI evaluation parameters. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is the best indicator of regional ecological environmental vulnerability. In previous studies, the authors believed that the tall tree canopy in summer would make the NDVI estimate higher than the actual value, while the long-wave radiation from the ground in winter was not significantly affected by the tree canopy [37]. Therefore, this study hopes to determine the ecological quality weights of different land uses by using the NDVI in summer and winter.

- Finally, I evaluated the BMR’s annual EQI index based on formula (2).

- It is important to pay attention to the land use types that have a greater impact or contribution to the evaluation results when evaluating the ecological environment quality of urban areas. It is the key land use to control the ecological quality of BMR.

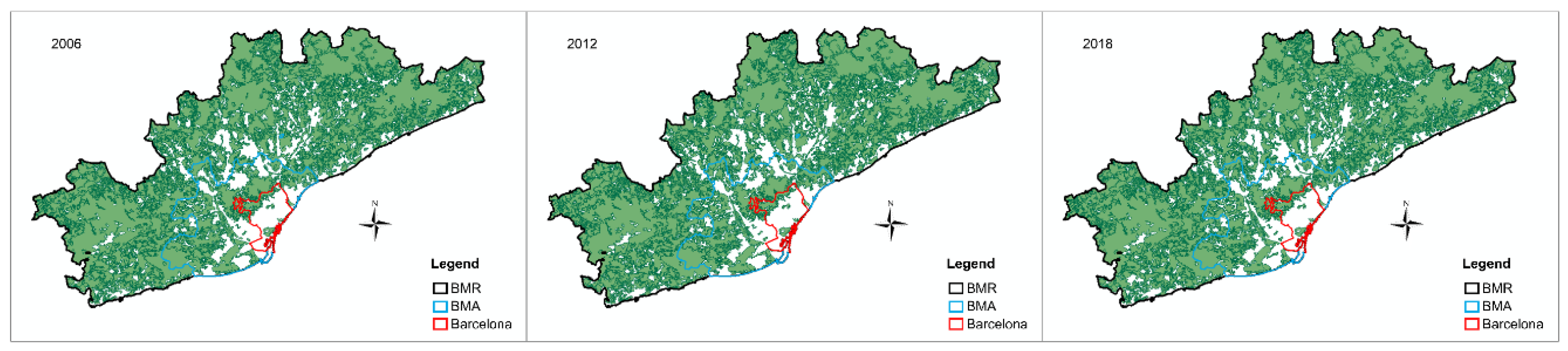

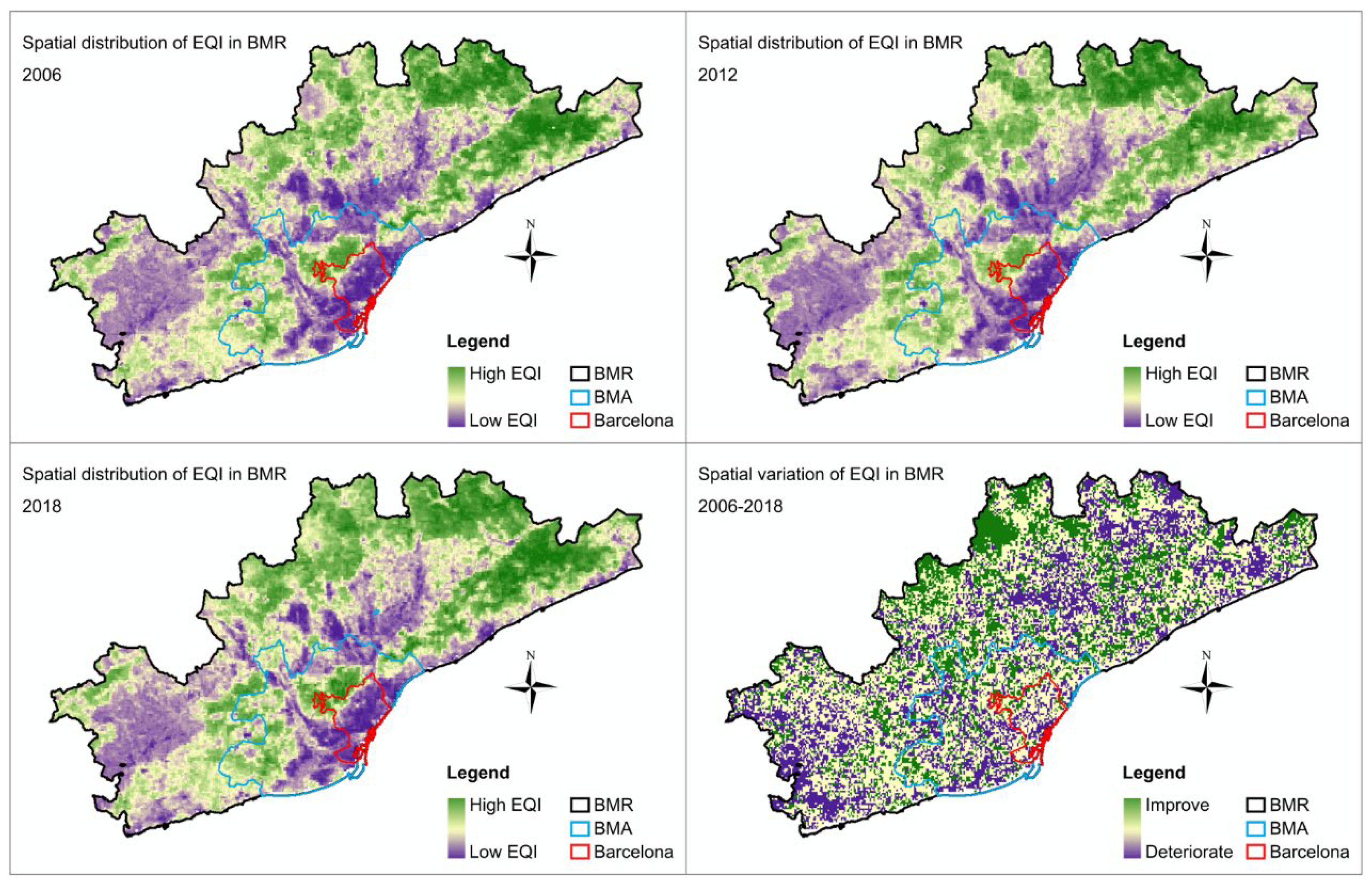

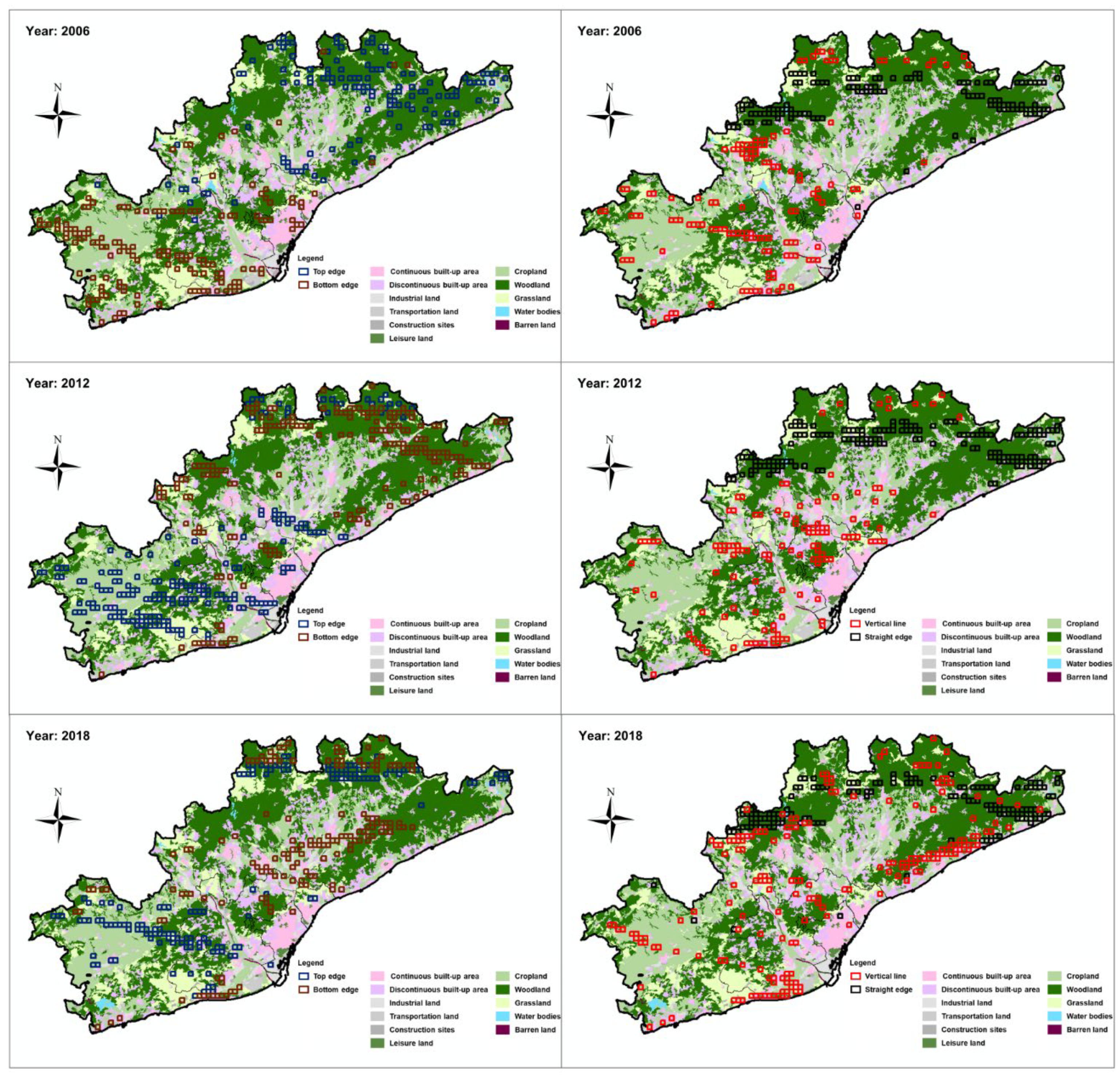

- In addition, we also need to draw the distribution map of the annual evaluation results of the ecological environment quality index of BMR and the change map of the results from 2006 to 2018 to analyze the distribution and evolution direction of the ecological quality of BMR from a spatial perspective, and determine the areas where the ecological quality of BMR continues to improve.

- 2.

- Then, we need to study the relationship between the key land use distribution and various possible influencing factors that affect the assessment results. The various types of data listed in the table need to be collected. MODIS can provide land surface temperature (LST). The urban heat island effect (UHI) will be expressed as the urban-rural temperature difference, that is, the difference in the average surface temperature between the urban built-up area and the rural area based on land cover data. Subtracting the average surface temperature of the daytime and nighttime in the rural area each year can get the approximate intensity distribution of the urban heat island effect. The larger the value, the greater the intensity of the urban heat island effect. DEM terrain data comes from SRTM (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/sensors/srtm), with a resolution of 30m. Impervious ground data comes from GlobeLand 30 (https://www.webmap.cn/commres.do?method=globeIndex), with a resolution of 30 meters. E-obs can provide annual European precipitation grid data, as well as daily maximum temperature (T_max) and minimum temperature (T_min), but the resolution is 1°, which is very large (https://surfobs.climate.copernicus.eu/dataaccess/access_eobs.php). Therefore, we used the kriging interpolation method based on the E-obs data to reconstruct the relevant climate map of BMR with a resolution of 1km. The night light data is divided into two parts. The data from 1992 to 2013 come from DMSP data with a resolution of 30 arc seconds and a numerical range of 0-63. The night light data after 2013 are provided by VIIRS with a resolution of 15 arc seconds, which is more accurate and very different from DMSP. In the previous work of the authors, the two datasets were calibrated and unified using the stepwise calibration method, which will not be repeated here [38]. After obtaining the above data, we established a 1km grid within the BMR range, extracted the proportion of key land use area in the grid each year as the dependent variable, and established an OLS model to analyze their importance.

- 3.

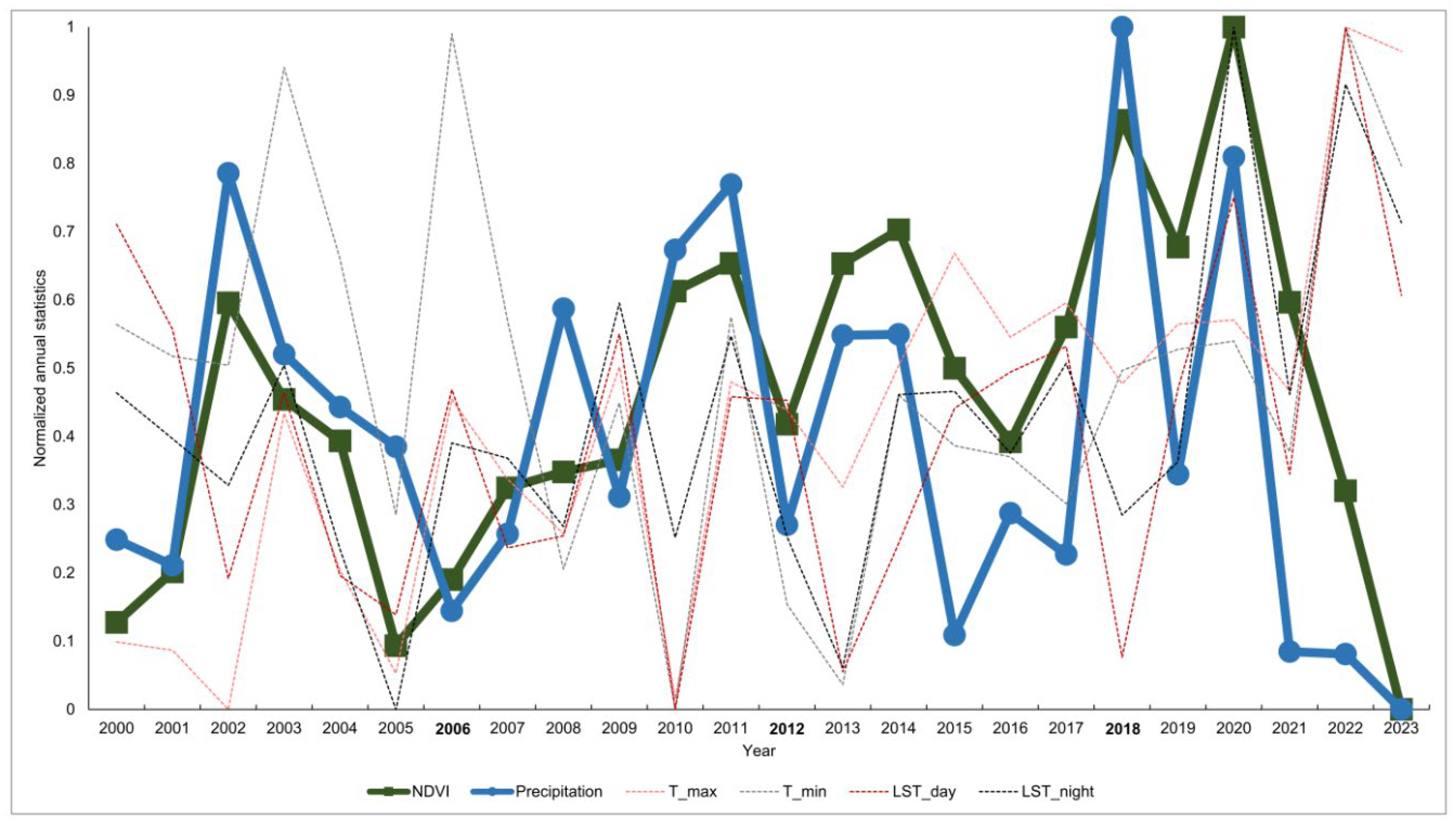

- Once it is clear that there is a clear interaction between NDVI and the distribution of key land uses that affect EQI assessment results, we must analyze the climate factors that can affect NDVI to discover the indirect impact of climate change on ecological quality. We established a climate database from 2000 to 2023, using the annual average NDVI as the dependent variable and multiple climate data as explanatory variables to analyze the strength of the correlation between them.

- 4.

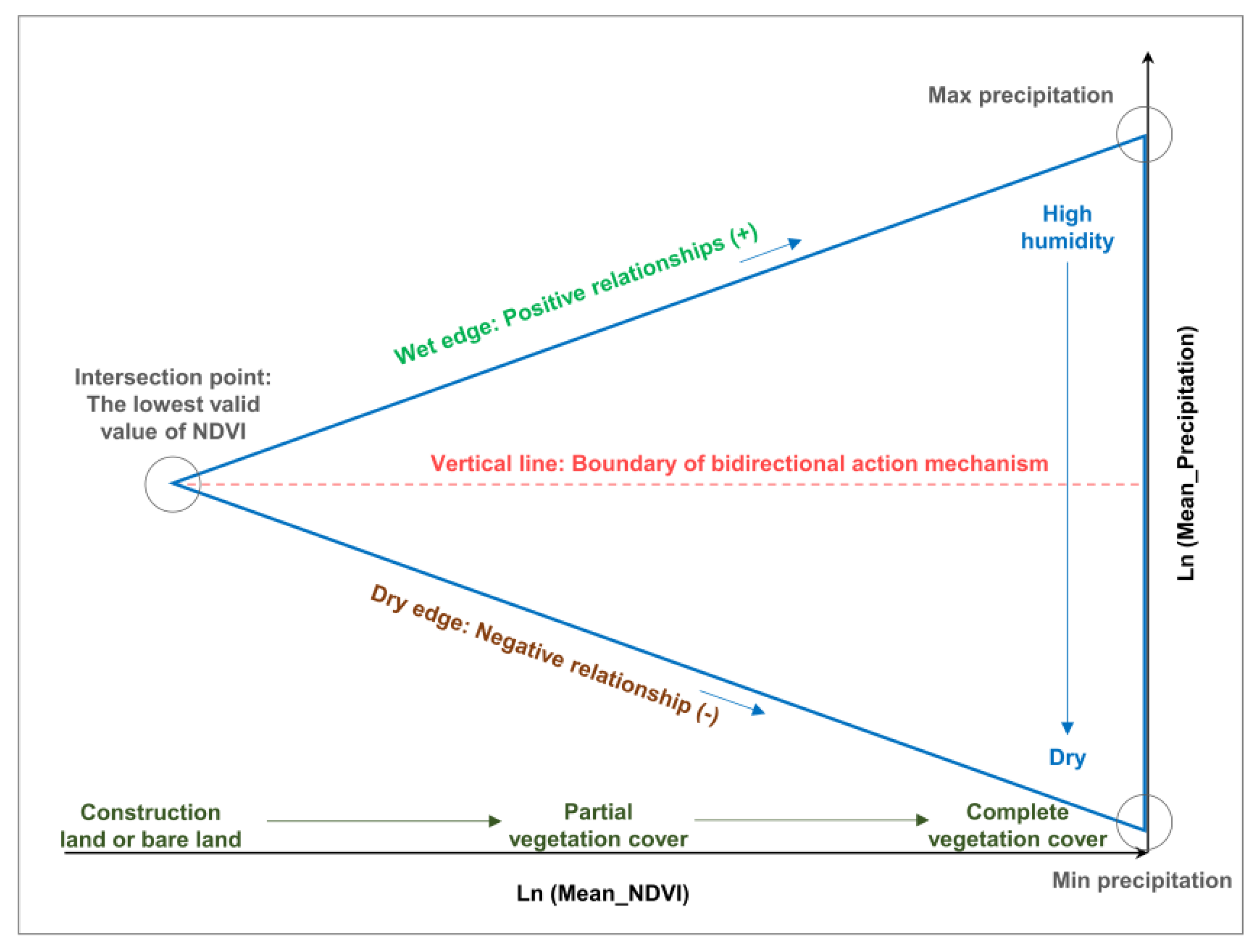

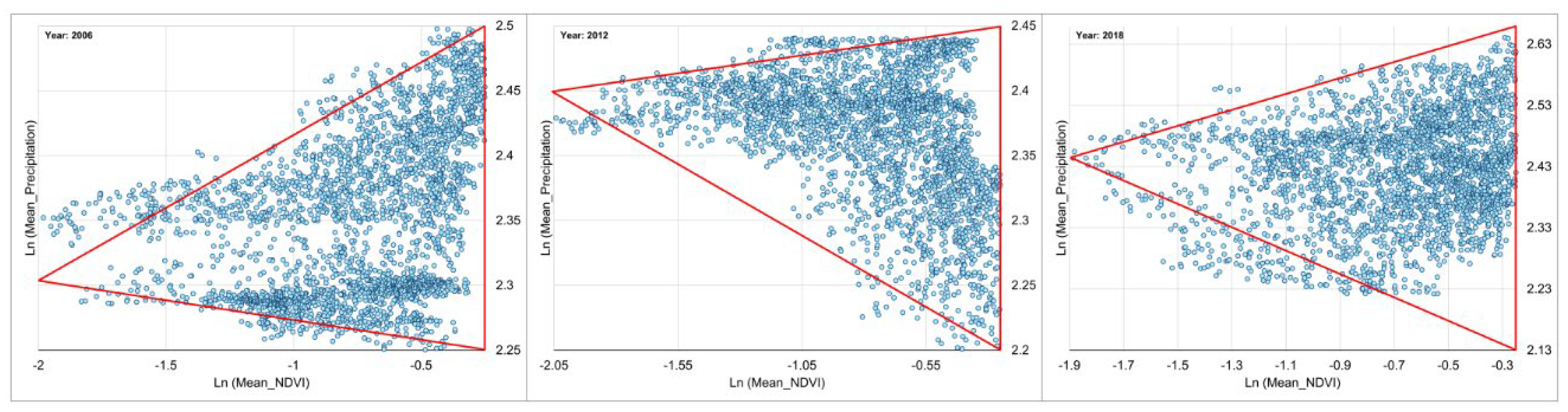

- In the previous study, the authors found that precipitation is a highly complex control factor [27], and there is an unresolved and strong interaction between it and NDVI, but this complex relationship is difficult to explain through ordinary regression models. Therefore, we try to use the precipitation-NDVI characteristic triangle space to analyze this mechanism.

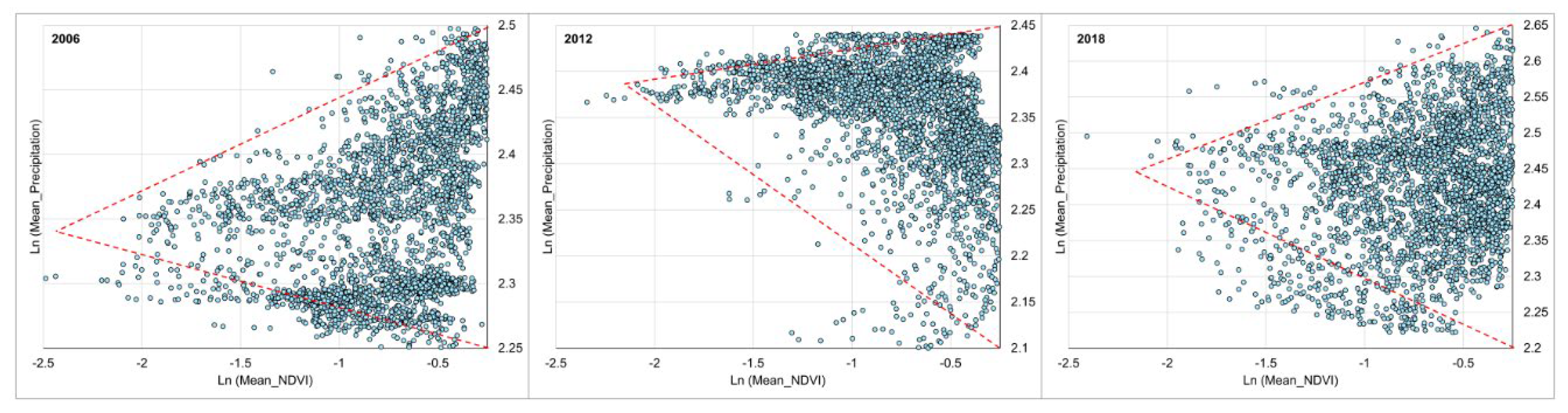

- Firstly, for each year, a precipitation-NDVI scatter plot was established. In order to facilitate the analysis of the physical meaning of each side of the triangle, we used NDVI as the X-axis and precipitation as the Y-axis. Since the numerical ranges of the two values are quite different, the spatial characteristics of the established scatter plot are not obvious, so we calculated the Ln log function for both NDVI and precipitation.

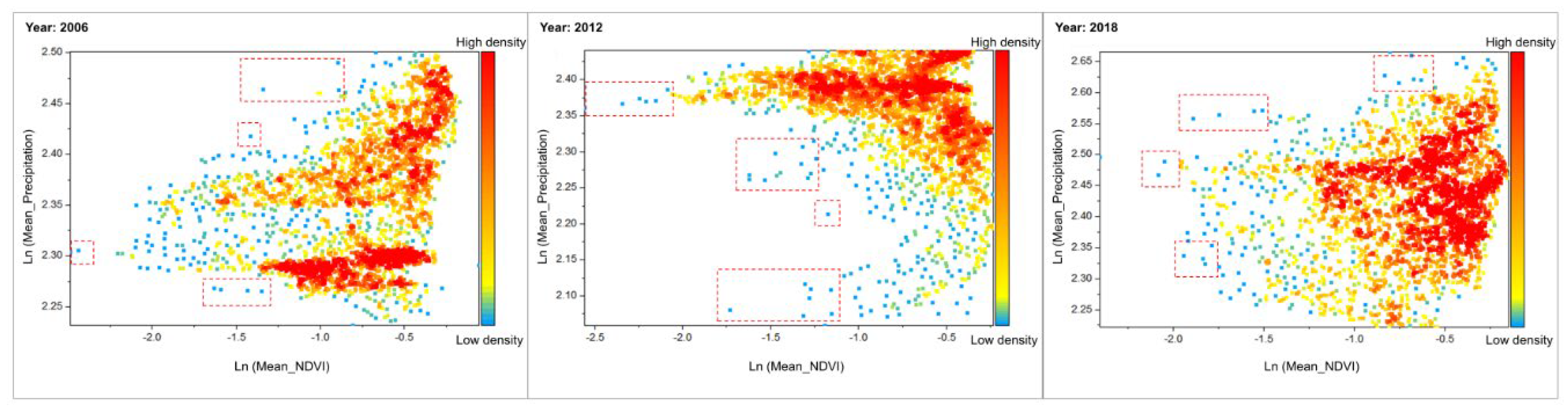

- Then, the density characteristics of the scatter plot are analyzed using nonparametric kernel density estimation (KDE). Kernel density estimation is a nonparametric method used in probability theory to estimate the probability density kernel function of an unknown random variable, proposed by Rosenblatt [39] and Emanuel [40]. Kernel density estimation can infer the overall data distribution based on a limited sample and analyze the regional location of data aggregation. It does not rely on the overall distribution and its parameters, but instead obtains structural relationships through direct estimation and derivation based on sample data [41]. This study uses Qrigin 2021 for kernel density estimation analysis.

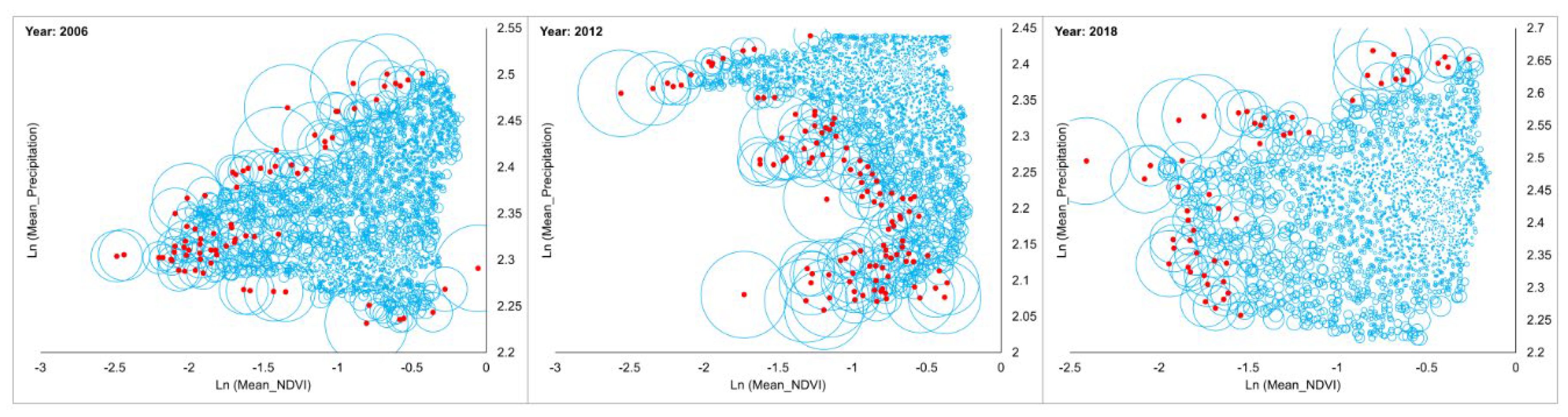

- If it is found that the scattered points are unevenly distributed and there are scattered points with low density distribution around the cluster, we need to perform local outlier factor detection (LOF). This detection method is a density-based outlier detection algorithm, which mainly determines whether it is abnormal by calculating the outlier factor of the sample and comparing whether it is far away from the dense data [42]. Outliers usually appear relatively isolated, so samples with large LOF values have low density and are considered abnormal. In the recognition process, it is considered that when the ratio between the distribution density of the point and the overall average density is much greater than 1, it is more likely to be an outlier [43].

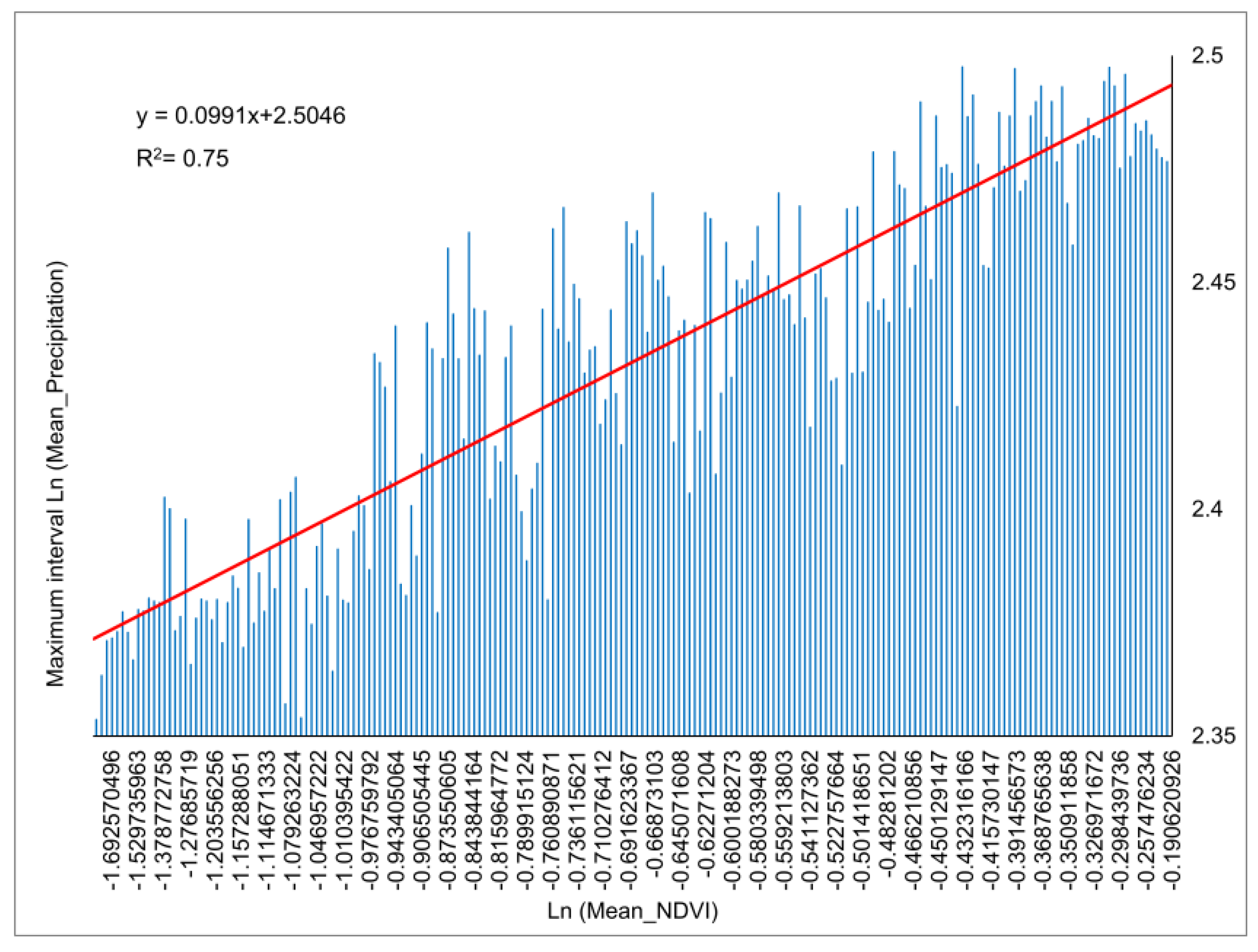

- After removing the abnormal outliers, we can determine the sides of the characteristic triangle. The maximum NDVI value among the retained scattered points will be used as the straight edge. For the hypotenuse, we use 0.01 as a minimum interval and find the maximum and minimum precipitation values in each interval. Then use the least squares method to perform a linear fit with Equation (3) to obtain the hypotenuse of the triangle.

- Finally, after completing the most critical triangle fitting, we can analyze the physical meaning of each side of the precipitation-NDVI characteristic triangle and the space, and further analyze the relationship between NDVI and precipitation. This allows us to indirectly understand the impact of precipitation on the green space system.

3. Results

3.1. BMR Ecological Environment Quality Assessment

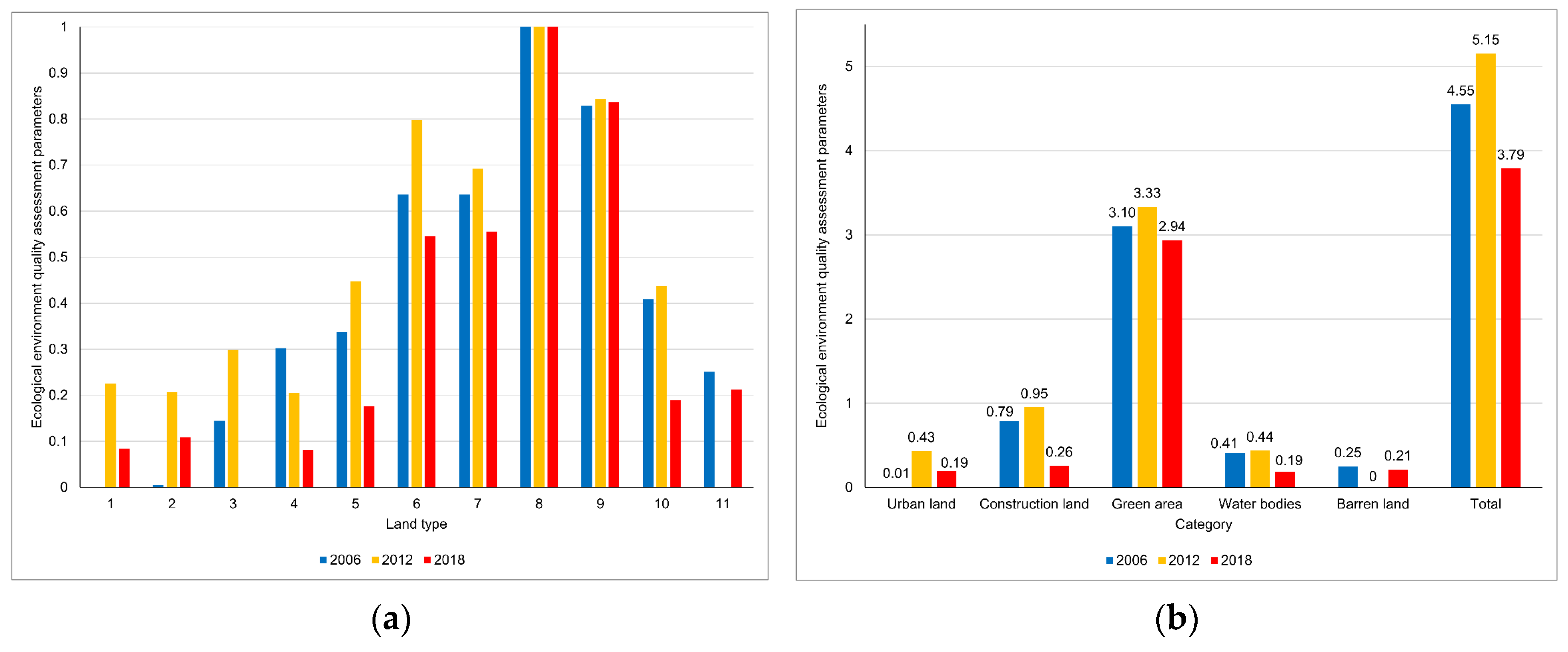

3.1.1. Green Area Is the Key Land Use that Provides Ecological Benefits

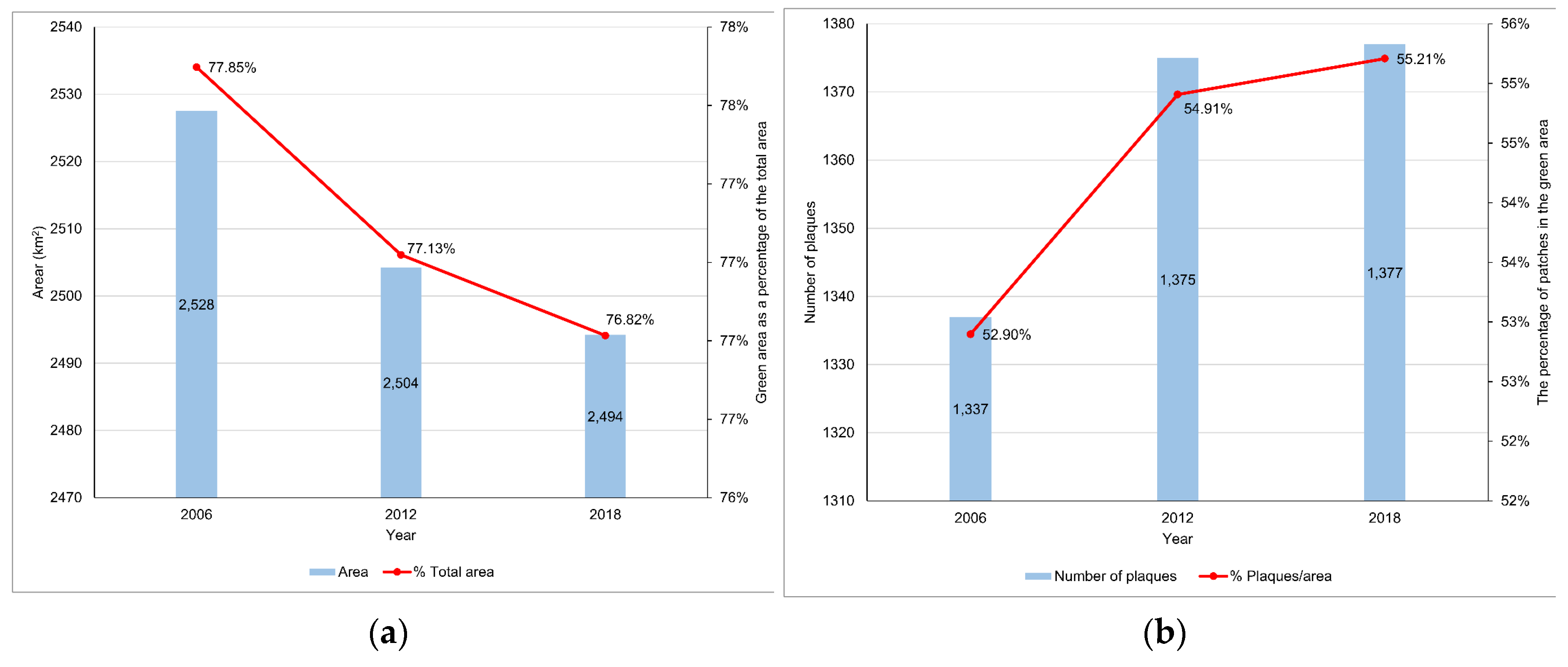

3.1.2. The Green Area Is Shrinking but Becoming More Fragmented

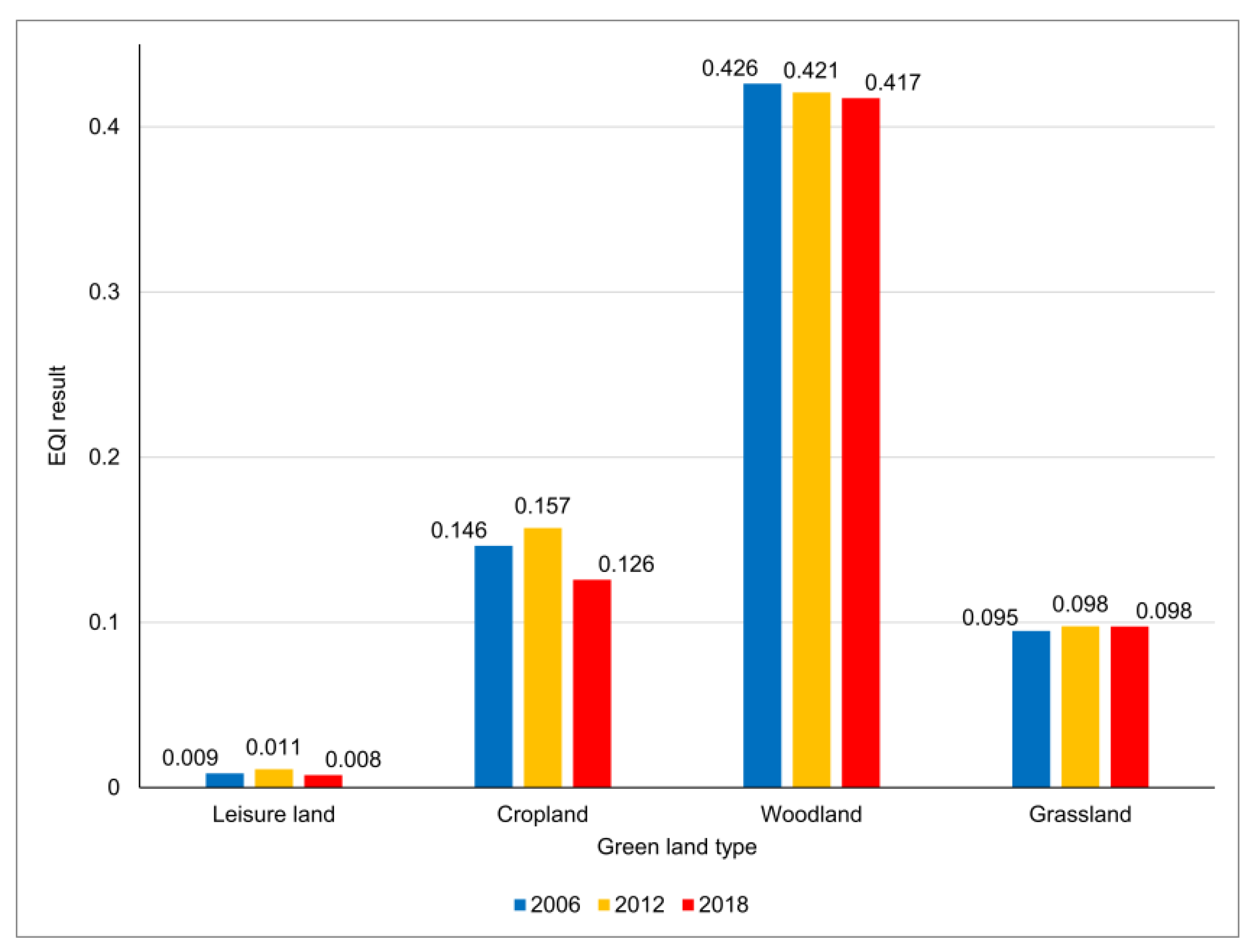

3.1.3. The Ecological Quality Results of BMR Are Generally Appreciable, with Green Area Making the Largest Contribution

3.1.4. The EQI of Forests Cannot Be Ignored

3.1.5. BMR Ecological Environment Quality Distribution Needs to Be Improved

3.2. Analysis of Factors Affecting Green Area Distribution

3.3. Analysis of Climate Factors Affecting NDVI Evolution

3.4. Spatial Analysis of Precipitation/NDVI Characteristic Triangle

3.4.1. Spatial Definition of Precipitation/NDVI Characteristic Triangle

3.4.2. Construction of the Triangular Spatial Structure of the Precipitation/NDVI Scatter Plot

3.4.3. Analysis of the Physical Meaning of the Triangular Space of the Precipitation/NDVI Scatter Plot

- Analysis of parameters of spatial structure of precipitation/NDVI characteristic triangle

- Practical analysis of spatial structure of precipitation/NDVI characteristic triangle

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Classification results | CLC land use description | Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Continuous built-up area | Continuous urban fabric | Urban land |

| 2 | Discontinuous built-up area | Discontinuous urban fabric | |

| 3 | Industrial land | Industrial or commercial units | Construction land |

| 4 | Transportation land | Road and rail networks and associated land | |

| Port areas | |||

| Airports | |||

| 5 | Mine, dump and construction sites | Mineral extraction sites | |

| Dump sites | |||

| Construction sites | |||

| 6 | Leisure land | Green urban areas | Green area |

| Sport and leisure facilities | |||

| 7 | Cropland | Non-irrigated arable land | |

| Permanently irrigated land | |||

| Rice fields | |||

| Vineyards | |||

| Fruit trees and berry plantations | |||

| Olive groves | |||

| Pastures | |||

| Annual crops associated with permanent crops | |||

| Complex cultivation patterns | |||

| Land principally occupied by agriculture, with significant areas of natural vegetation | |||

| Agro-forestry areas | |||

| 8 | Woodland | Broad-leaved forest | |

| Coniferous forest | |||

| Mixed forest | |||

| 9 | Grassland | Natural grasslands | |

| Moors and heathland | |||

| Sclerophyllous vegetation | |||

| Transitional woodland-shrub | |||

| Inland marshes | |||

| Peat bogs | |||

| Salt marshes | |||

| 10 | Barren land | Beaches, dunes, sands | Barren land |

| Bare rocks | |||

| Sparsely vegetated areas | |||

| Burnt areas | |||

| Glaciers and perpetual snow | |||

| Salines | |||

| Intertidal flats | |||

| 11 | Water bodies | Water courses | Water bodies |

| Water bodies | |||

| Coastal lagoons | |||

| Estuaries | |||

| Sea and ocean | |||

| NODATA |

Appendix B

| Code | EQI_2006 | EQI_2012 | EQI_2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0.009219 | 0.003457 |

| 2 | 0.000535 | 0.021722 | 0.011454 |

| 3 | 0.007083 | 0.015654 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.003032 | 0.002596 | 0.001035 |

| 5 | 0.002876 | 0.003089 | 0.001127 |

| 6 | 0.008674 | 0.011114 | 0.0076 |

| 7 | 0.146374 | 0.157215 | 0.125857 |

| 8 | 0.426103 | 0.42076 | 0.417397 |

| 9 | 0.094843 | 0.097719 | 0.097545 |

| 10 | 0.00164 | 0.001237 | 0.000914 |

| 11 | 0.000504 | 0 | 0.000353 |

| Total | 0.691664 | 0.740324 | 0.666741 |

Appendix C

| Var | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 1 | 1 | -.058** | .176** | .268** | .090** | .448** | .212** | .679** | .114** | -.463** | -.549** | -.124** | -.300** | -.421** | .307** | -.536** | -.463** | -.549** | -.947** | -.982** | -.514** |

| 2 | -.058** | 1 | .705** | -.283** | .049** | 0.003 | .036* | .312** | .884** | -.261** | .331** | -.501** | .212** | -.379** | .693** | -.384** | -.261** | .331** | .067** | .063** | .068** |

| 3 | .176** | .705** | 1 | .459** | .053** | .480** | .136** | .405** | .863** | -.428** | -.245** | -.291** | -.379** | -.788** | .733** | -.427** | -.428** | -.245** | -.142** | -.179** | -.279** |

| 4 | .268** | -.283** | .459** | 1 | 0.012 | .609** | .129** | .144** | 0.033 | -.267** | -.692** | .181** | -.775** | -.531** | .046* | -.103** | -.267** | -.692** | -.246** | -.281** | -.412** |

| 5 | .090** | .049** | .053** | 0.012 | 1 | .124** | .068** | .140** | .085** | -.098** | -.089** | -.045* | -.111** | -.086** | 0.021 | -.124** | -.098** | -.089** | -.084** | -.087** | -.122** |

| 6 | .448** | 0.003 | .480** | .609** | .124** | 1 | .206** | .554** | .355** | -.659** | -.722** | -.217** | -.755** | -.712** | .307** | -.523** | -.659** | -.722** | -.420** | -.452** | -.734** |

| 7 | .212** | .036* | .136** | .129** | .068** | .206** | 1 | .409** | .102** | -.229** | -.113** | -.168** | -.100** | -.131** | .091** | -.187** | -.229** | -.113** | -.141** | -.192** | -.141** |

| 8 | .679** | .312** | .405** | .144** | .140** | .554** | .409** | 1 | .447** | -.804** | -.328** | -.638** | -.263** | -.513** | .467** | -.930** | -.804** | -.328** | -.644** | -.683** | -.526** |

| 9 | .114** | .884** | .863** | 0.033 | .085** | .355** | .102** | .447** | 1 | -.422** | -0.022 | -.435** | -.178** | -.686** | .770** | -.496** | -.422** | -0.022 | -.087** | -.108** | -.238** |

| 10 | -.463** | -.261** | -.428** | -.267** | -.098** | -.659** | -.229** | -.804** | -.422** | 1 | .409** | .790** | .364** | .524** | -.389** | .807** | 1.000** | .409** | .434** | .471** | .565** |

| 11 | -.549** | .331** | -.245** | -.692** | -.089** | -.722** | -.113** | -.328** | -0.022 | .409** | 1 | -.235** | .689** | .580** | -.183** | .243** | .409** | 1.000** | .511** | .558** | .673** |

| 12 | -.124** | -.501** | -.291** | .181** | -.045* | -.217** | -.168** | -.638** | -.435** | .790** | -.235** | 1 | -.075** | .168** | -.291** | .696** | .790** | -.235** | .119** | .126** | .150** |

| 13 | -.300** | .212** | -.379** | -.775** | -.111** | -.755** | -.100** | -.263** | -.178** | .364** | .689** | -.075** | 1 | .670** | -.038* | .218** | .364** | .689** | .289** | .307** | .576** |

| 14 | -.421** | -.379** | -.788** | -.531** | -.086** | -.712** | -.131** | -.513** | -.686** | .524** | .580** | .168** | .670** | 1 | -.767** | .475** | .524** | .580** | .382** | .427** | .666** |

| 15 | .307** | .693** | .733** | .046* | 0.021 | .307** | .091** | .467** | .770** | -.389** | -.183** | -.291** | -.038* | -.767** | 1 | -.453** | -.389** | -.183** | -.265** | -.310** | -.401** |

| 16 | -.536** | -.384** | -.427** | -.103** | -.124** | -.523** | -.187** | -.930** | -.496** | .807** | .243** | .696** | .218** | .475** | -.453** | 1 | .807** | .243** | .508** | .539** | .468** |

| 17 | -.463** | -.261** | -.428** | -.267** | -.098** | -.659** | -.229** | -.804** | -.422** | 1.000** | .409** | .790** | .364** | .524** | -.389** | .807** | 1 | .409** | .434** | .471** | .565** |

| 18 | -.549** | .331** | -.245** | -.692** | -.089** | -.722** | -.113** | -.328** | -0.022 | .409** | 1.000** | -.235** | .689** | .580** | -.183** | .243** | .409** | 1 | .511** | .558** | .673** |

| 19 | -.947** | .067** | -.142** | -.246** | -.084** | -.420** | -.141** | -.644** | -.087** | .434** | .511** | .119** | .289** | .382** | -.265** | .508** | .434** | .511** | 1 | .945** | .492** |

| 20 | -.982** | .063** | -.179** | -.281** | -.087** | -.452** | -.192** | -.683** | -.108** | .471** | .558** | .126** | .307** | .427** | -.310** | .539** | .471** | .558** | .945** | 1 | .515** |

| 21 | -.514** | .068** | -.279** | -.412** | -.122** | -.734** | -.141** | -.526** | -.238** | .565** | .673** | .150** | .576** | .666** | -.401** | .468** | .565** | .673** | .492** | .515** | 1 |

| Var | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 1 | 1 | -.060** | .178** | .272** | .090** | .456** | .214** | .677** | -.184** | -.454** | -.529** | -.176** | -.316** | -.335** | .197** | -.553** | -.454** | -.529** | -.953** | -.981** | -.510** |

| 2 | -.060** | 1 | .705** | -.283** | .049** | 0.003 | .036* | .284** | -.681** | -.223** | .047* | -.303** | -.430** | -.353** | .112** | -.366** | -.223** | .047* | 0.02 | 0.032 | .049** |

| 3 | .178** | .705** | 1 | .459** | .053** | .480** | .136** | .405** | -.596** | -.439** | -.527** | -.160** | -.745** | -.873** | .588** | -.485** | -.439** | -.527** | -.149** | -.163** | -.282** |

| 4 | .272** | -.283** | .459** | 1 | 0.012 | .609** | .129** | .185** | .096** | -.323** | -.741** | .132** | -.413** | -.706** | .660** | -.211** | -.323** | -.741** | -.194** | -.218** | -.393** |

| 5 | .090** | .049** | .053** | 0.012 | 1 | .124** | .068** | .142** | -0.015 | -.097** | -.132** | -0.025 | -.112** | -.051** | -0.033 | -.135** | -.097** | -.132** | -.058* | -.072** | -.128** |

| 6 | .456** | 0.003 | .480** | .609** | .124** | 1 | .206** | .593** | -.186** | -.745** | -.815** | -.327** | -.672** | -.632** | .296** | -.613** | -.745** | -.815** | -.364** | -.418** | -.735** |

| 7 | .214** | .036* | .136** | .129** | .068** | .206** | 1 | .433** | -.036* | -.228** | -.125** | -.188** | -.084** | -.157** | .154** | -.249** | -.228** | -.125** | -.142** | -.181** | -.146** |

| 8 | .677** | .284** | .405** | .185** | .142** | .593** | .433** | 1 | -.360** | -.802** | -.441** | -.662** | -.467** | -.441** | .207** | -.922** | -.802** | -.441** | -.665** | -.709** | -.566** |

| 9 | -.184** | -.681** | -.596** | .096** | -0.015 | -.186** | -.036* | -.360** | 1 | .360** | .181** | .308** | .647** | .443** | -0.035 | .368** | .360** | .181** | .156** | .165** | .318** |

| 10 | -.454** | -.223** | -.439** | -.323** | -.097** | -.745** | -.228** | -.802** | .360** | 1 | .565** | .812** | .560** | .460** | -.146** | .811** | 1.000** | .565** | .364** | .406** | .635** |

| 11 | -.529** | .047* | -.527** | -.741** | -.132** | -.815** | -.125** | -.441** | .181** | .565** | 1 | -0.022 | .629** | .729** | -.484** | .448** | .565** | 1.000** | .475** | .518** | .664** |

| 12 | -.176** | -.303** | -.160** | .132** | -0.025 | -.327** | -.188** | -.662** | .308** | .812** | -0.022 | 1 | .234** | .042* | .165** | .668** | .812** | -0.022 | .087** | .108** | .301** |

| 13 | -.316** | -.430** | -.745** | -.413** | -.112** | -.672** | -.084** | -.467** | .647** | .560** | .629** | .234** | 1 | .756** | -.163** | .503** | .560** | .629** | .232** | .261** | .592** |

| 14 | -.335** | -.353** | -.873** | -.706** | -.051** | -.632** | -.157** | -.441** | .443** | .460** | .729** | .042* | .756** | 1 | -.769** | .475** | .460** | .729** | .285** | .321** | .432** |

| 15 | .197** | .112** | .588** | .660** | -0.033 | .296** | .154** | .207** | -0.035 | -.146** | -.484** | .165** | -.163** | -.769** | 1 | -.223** | -.146** | -.484** | -.199** | -.226** | -.075** |

| 16 | -.553** | -.366** | -.485** | -.211** | -.135** | -.613** | -.249** | -.922** | .368** | .811** | .448** | .668** | .503** | .475** | -.223** | 1 | .811** | .448** | .532** | .565** | .540** |

| 17 | -.454** | -.223** | -.439** | -.323** | -.097** | -.745** | -.228** | -.802** | .360** | 1.000** | .565** | .812** | .560** | .460** | -.146** | .811** | 1 | .565** | .364** | .406** | .635** |

| 18 | -.529** | .047* | -.527** | -.741** | -.132** | -.815** | -.125** | -.441** | .181** | .565** | 1.000** | -0.022 | .629** | .729** | -.484** | .448** | .565** | 1 | .475** | .518** | .664** |

| 19 | -.953** | 0.02 | -.149** | -.194** | -.058* | -.364** | -.142** | -.665** | .156** | .364** | .475** | .087** | .232** | .285** | -.199** | .532** | .364** | .475** | 1 | .942** | .355** |

| 20 | -.981** | 0.032 | -.163** | -.218** | -.072** | -.418** | -.181** | -.709** | .165** | .406** | .518** | .108** | .261** | .321** | -.226** | .565** | .406** | .518** | .942** | 1 | .389** |

| 21 | -.510** | .049** | -.282** | -.393** | -.128** | -.735** | -.146** | -.566** | .318** | .635** | .664** | .301** | .592** | .432** | -.075** | .540** | .635** | .664** | .355** | .389** | 1 |

| Var | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 1 | 1 | -.049** | .192** | .280** | .088** | .461** | .213** | .688** | .125** | -.547** | -.576** | -.303** | -.305** | -.376** | .242** | -.589** | -.547** | -.576** | -.944** | -.978** | -.560** |

| 2 | -.049** | 1 | .705** | -.283** | .049** | 0.003 | .036* | .334** | -.039* | -.136** | -0.008 | -.172** | -.409** | -.312** | -0.018 | -.370** | -.136** | -0.008 | .070** | .060** | 0.002 |

| 3 | .192** | .705** | 1 | .459** | .053** | .480** | .136** | .442** | -.207** | -.464** | -.509** | -.241** | -.784** | -.858** | .431** | -.473** | -.464** | -.509** | -.145** | -.186** | -.349** |

| 4 | .280** | -.283** | .459** | 1 | 0.012 | .609** | .129** | .174** | -.127** | -.449** | -.616** | -.146** | -.515** | -.732** | .585** | -.184** | -.449** | -.616** | -.251** | -.283** | -.420** |

| 5 | .088** | .049** | .053** | 0.012 | 1 | .124** | .068** | .145** | .074** | -.065** | -.138** | 0.014 | -.123** | -.060** | -.065** | -.145** | -.065** | -.138** | -.088** | -.088** | -.081** |

| 6 | .461** | 0.003 | .480** | .609** | .124** | 1 | .206** | .554** | .152** | -.806** | -.741** | -.522** | -.715** | -.670** | .193** | -.587** | -.806** | -.741** | -.430** | -.465** | -.759** |

| 7 | .213** | .036* | .136** | .129** | .068** | .206** | 1 | .425** | .042* | -.226** | -.112** | -.215** | -.104** | -.165** | .150** | -.391** | -.226** | -.112** | -.194** | -.202** | -.179** |

| 8 | .688** | .334** | .442** | .174** | .145** | .554** | .425** | 1 | .229** | -.768** | -.456** | -.675** | -.479** | -.466** | .155** | -.948** | -.768** | -.456** | -.659** | -.692** | -.595** |

| 9 | .125** | -.039* | -.207** | -.127** | .074** | .152** | .042* | .229** | 1 | -.264** | -.062** | -.300** | -.054** | .111** | -.273** | -.275** | -.264** | -.062** | -.145** | -.125** | -.204** |

| 10 | -.547** | -.136** | -.464** | -.449** | -.065** | -.806** | -.226** | -.768** | -.264** | 1 | .649** | .840** | .631** | .590** | -.168** | .776** | 1.000** | .649** | .509** | .553** | .770** |

| 11 | -.576** | -0.008 | -.509** | -.616** | -.138** | -.741** | -.112** | -.456** | -.062** | .649** | 1 | .132** | .650** | .750** | -.427** | .427** | .649** | 1.000** | .536** | .585** | .722** |

| 12 | -.303** | -.172** | -.241** | -.146** | 0.014 | -.522** | -.215** | -.675** | -.300** | .840** | .132** | 1 | .359** | .234** | .086** | .705** | .840** | .132** | .281** | .304** | .488** |

| 13 | -.305** | -.409** | -.784** | -.515** | -.123** | -.715** | -.104** | -.479** | -.054** | .631** | .650** | .359** | 1 | .829** | -.077** | .504** | .631** | .650** | .279** | .308** | .609** |

| 14 | -.376** | -.312** | -.858** | -.732** | -.060** | -.670** | -.165** | -.466** | .111** | .590** | .750** | .234** | .829** | 1 | -.621** | .464** | .590** | .750** | .330** | .385** | .556** |

| 15 | .242** | -0.018 | .431** | .585** | -.065** | .193** | .150** | .155** | -.273** | -.168** | -.427** | .086** | -.077** | -.621** | 1 | -.118** | -.168** | -.427** | -.197** | -.255** | -.138** |

| 16 | -.589** | -.370** | -.473** | -.184** | -.145** | -.587** | -.391** | -.948** | -.275** | .776** | .427** | .705** | .504** | .464** | -.118** | 1 | .776** | .427** | .564** | .592** | .575** |

| 17 | -.547** | -.136** | -.464** | -.449** | -.065** | -.806** | -.226** | -.768** | -.264** | 1.000** | .649** | .840** | .631** | .590** | -.168** | .776** | 1 | .649** | .509** | .553** | .770** |

| 18 | -.576** | -0.008 | -.509** | -.616** | -.138** | -.741** | -.112** | -.456** | -.062** | .649** | 1.000** | .132** | .650** | .750** | -.427** | .427** | .649** | 1 | .536** | .585** | .722** |

| 19 | -.944** | .070** | -.145** | -.251** | -.088** | -.430** | -.194** | -.659** | -.145** | .509** | .536** | .281** | .279** | .330** | -.197** | .564** | .509** | .536** | 1 | .946** | .536** |

| 20 | -.978** | .060** | -.186** | -.283** | -.088** | -.465** | -.202** | -.692** | -.125** | .553** | .585** | .304** | .308** | .385** | -.255** | .592** | .553** | .585** | .946** | 1 | .571** |

| 21 | -.560** | 0.002 | -.349** | -.420** | -.081** | -.759** | -.179** | -.595** | -.204** | .770** | .722** | .488** | .609** | .556** | -.138** | .575** | .770** | .722** | .536** | .571** | 1 |

Appendix D

| NDVI | Precipitation | T_max | T_min | LST_day | LST_night | |

| NDVI | 1 | 0.684** | 0.053 | -0.283 | -0.236 | 0.131 |

| Precipitation | 0.684** | 1 | -0.388 | -0.256 | -0.484* | -0.168 |

| T_max | 0.053 | -0.388 | 1 | 0.433* | 0.593** | 0.670** |

| T_min | -0.283 | -0.256 | 0.433* | 1 | 0.563** | 0.555** |

| LST_day | -0.236 | -0.484* | 0.593** | 0.563** | 1 | 0.817** |

| LST_night | 0.131 | -0.168 | 0.670** | 0.555** | 0.817** | 1 |

References

- Liu, T. Evaluation of Guilin’s urban ecological environment based on remote sensing data. Master’s Thesis, Guilin University of Technology, Guangxi, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ramez, A.B.; Hooi, H.L.; Jeremy, C. The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: A critical literature survey. Resources Policy 2017, 51, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Wu, Z.; Guo, G. Research on the relationship between built environment and urban biodiversity in high-density urban areas: Taking Century Avenue in Pudong New Area, Shanghai as an example. Urban Development Research Research 2018, 025, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, K.; Li, J.; Long, M. Characteristics and key issues of soil and water loss in typical karst rocky desertification control areas. Chinese Journal of Geography 2012, 67, 878–888. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, J.; Arellano, B. Effects of urban greenery on health. A study from remote sensing. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Nice, France, 11 June 2022.

- Xu, Z.; Blanca, A. Urban sprawl and warming—research on the evolution of the urban sprawl of chinese municipalities and its relationship with climate warming in the past three decades. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Nice, France, 2022.

- Wang, F.; Liang, R.; Yang, X.; Chen, M. Research on ecological water demand in northwest China—theoretical analysis of ecological water demand in Arid and Semi-arid Regions. Journal of Natural Resources 2002, 01, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Chahannaoer basin based on improved remote sensing ecological index. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Anhui, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lavorel, S.; Flannigan, M.D.; Lambin, E.F. Vulnerability of land systems to fire: interactions among humans, climate, the atmosphere, and ecosystems. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2007, 12, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.S.; Peters, C.D.; Watts, J.M. Estimating soil moisture at the watershed scale with satellite-based radar and land surface models. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2004, 30, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Kumar, P.; Pathan, S.K. Urban Neighborhood Green Index—A measures of green spaces inutban areas. Landscape and Urban Planning 2012, 105, 0–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, J.D.; Jones, K.B. Environmental auditing, An Integrated Environmental Assessment of the US Mid-Atlantic Region. Environment Manage 1999, 24, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivits, E; Cherlet, M; Mehl, W; Sommer, S. Estimating the ecologic status and change of riparian zones in Andalusia assessed by multi-temporal AVHHR data. Ecol Indie 2009, 9, 422–431. [CrossRef]

- Manill, J.; Pino, J.; Mallarach, J.M. A land suitability index for strategic environmental assessment in metropolitan areas. Landscape & Urban Planning 2017, 201, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H. Remote sensing evaluation index of regional ecological environment change. China Environmental Science 2013, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar]

- Yifeng, H.; Yaning, C.; Jianli, D.; Zhi, L.; Yupeng, L.; Fan, S. Ecological impacts of land use change in the arid tarim river basin of chinal. Remote Sensing, 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. Study on Vegetation Cover Change and Its Response to Climate in Qilian Mountains from 2000 to 2012. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Gansu, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Yu, K.; Liu, J. Spatial and temporal evolution of ecological vulnerability in areas with severe soil erosion in southern China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2016, 27, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jinlong, H. Research on forest aboveground biomass regeneration method based on BEPS model and remote sensing. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University, Jiangsu, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miaomiao, C.; Hong, J.; Jian, C. Study on vegetation cover change in Hotan area of Xinjiang based on Landsat data. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences 2009, 37, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.; Mysterud, A. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels, K.; Prince, S.; Frost, P. Assessing the effects of human-induced land degradation in the former homelands of northern south africa with a 1 km AVHRR NDVI time-series. Remote sensing of environment 2004, 91, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Laurance, W.; O’Brien, T. Satellite remote sensing for applied ecologists: opportunities and challenges. Journal of applied ecology 2014, 51, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goward, S.; Prince, S. Transient effects of climate on vegetation dynamics: satellite observations. Journal of biogeography 1995, 22, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, S.; Brouwer, L.; Riezebos, H. Effects of grazing on vegetation and erosion in the chaco boreal, paraguay. Geoderma 1999, 88, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, R. Study on the evolution and driving force of surface ecological environment in western lli basin based on NDVI. Master’s Thesis, College of Disaster Prevention Technology, Hebei, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Arellano, B.; Roca, J. Study on factors influencing forest distribution in Barcelona metropolitan region. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tucker, C.; Kaufmann, R.K. Variations in northern vegetation activity inferred from satellite data of vegetation index during 1981 to 1999. Journal of geophysical research 2006, 106, 20069–20083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shang, S.; Mao, Q. Impact of soil moisture on vegetation growing condition and climate change over the Tibetan plateau. Journal of geophysical research: atmospheres 2012, 117, 15205–15215. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Niu, Z.; Tang, Q. Impact of topography on vegetation dynamics in a mountain-oasis-desert system in Xinjiang, China. Remote sensing 2018, 10, 946. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z. Responses of vegetation activity to multi-factor influences in different sub-regions of northeast China. Remote sensing 2014, 6, 5866–5887. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; Peters, A. Assessing vegetation response to drought in the northern great plains using vegetation and drought indices. Remote sensing of environment 2003, 87, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J. Response of temporal and spatial changes of vegetation in Heilongjiang Province to climate factors from 2000 to 2020. Forest engineering 2024, 40, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, S.; Li, J.; Chen, Y. Spatial and temporal variation characteristics of vegetation coverage in Inner Mongolia from 2001 to 2010. Acta geographica sinica 2012, 67, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Van Dijk, A.; De Jeu, R. Recent reversal in loss of global terrestrial biomass. Nature climate change 2015, 5, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Q.; Li, H.; Wu, H. Spatial-temporal evolution characteristics of NDVI and analysis of its climate driving factors in Nanchang. Forest engineering 2024, 40, 8023. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, B.; Roca, J. Modelling nighttime air temperature from remote sensing imagery and GIS data. Proceedings of SPIE, Space, Satellites, and Sustainability II, Glasgow, United Kingdom, 2021.

- Xu, Z.; Roca, J.; Arellano, B. Research on the expansion of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei China’s Capital metropolitan agglomeration based on night lighting technology. Proceedings of SPIE, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 19 October 2023.

- Rosenblatt, M. Remarks on some nonparametric estimates of a density function. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1956, 27, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, P. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Epanechnikov, A. Non-Parametric Estimation of a multivariate probability density. Theory of Probability & Its Applications 1969, 14, 153–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kun, X.; Qiang, D.; Hongmei, Z. Chiller fault detection based on isolation forest and KDE-LOF. Computer Applications and Software 2023, 40, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Breunig, M.; Kriegel, H. LOF: Identifying density-based local outliers. ACM SIGMOD record 2000, 29, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z. The triangular feature space between nighttime light intensity and vegetation index and its applications. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sandholt, I.; Rasmussen, K.; Andersen, J. A simple interpretation of the surface temperature/vegetation index space for assessment of surface moisture status. Remote Sensing of environment 2002, 79, 213–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengxin, W.; Jianya, G.; Xiaowen, L. Conditional vegetation temperature index and its application in drought monitoring. Journal of Wuhan University (Information Science Edition) 2001, 5, 412–8. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, B.; Roca, J.; Qianhui, Z. Spain: Towards a drier and warmer climate? Analysis of climate change effects on precipitation and temperature trends in spain. European meteorological society annual meeting, Barcelona, Spain, 2, September 2024.

| Type | Factors |

|---|---|

| Natural factors | Longitude |

| Latitude | |

| Distance from coastline | |

| Orientation | |

| Altitude | |

| NDVI | |

| Precipitation | |

| LST | |

| LST_day- LST_night | |

| T_max | |

| T_min | |

| T_max-T_min | |

| Human activity | NDBI |

| Urban heat island effect | |

| Impermeable area | |

| Artificial area | |

| Nighttime light data |

| Code | Reclassification | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Continuous built-up area | Urban land |

| 2 | Discontinuous built-up area | |

| 3 | Industrial land | Construction land |

| 4 | Transportation land | |

| 5 | Construction sites | |

| 6 | Leisure land | Green area |

| 7 | Cropland | |

| 8 | Woodland | |

| 9 | Grassland | |

| 10 | Water bodies | Water bodies |

| 11 | Barren land | Barren land |

| Categories | 2006 | 2012 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQI | % of total | EQI | % of total | EQI | % of total | |

| Urban land | 0.001 | 0.08% | 0.031 | 4.18% | 0.015 | 2.24% |

| Construction land | 0.013 | 1.88% | 0.021 | 2.88% | 0.002 | 0.32% |

| Green area | 0.676 | 97.73% | 0.687 | 92.77% | 0.648 | 97.25% |

| Water bodies | 0.002 | 0.24% | 0.001 | 0.17% | 0.001 | 0.14% |

| Barren land | 0.001 | 0.07% | 0.000 | 0 | 0.0003 | 0.05% |

| Overall | 0.692 | 100.00% | 0.740 | 100.00% | 0.667 | 100.00% |

| Independent variable b | Model_2006 a | Model_2012 a | Model_2018 a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Beta | t | Sig. | B | Beta | t | Sig. | B | Beta | t | Sig. | |

| Constant | -1719.33 | -6.00 | 0.00 | -1534.85 | -4.79 | 0.00 | -2681.47 | -5.75 | 0.00 | |||

| Longitude | 0.00 | -0.17 | -7.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.12 | -4.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.16 | -3.86 | 0.00 |

| Latitude | 0.00 | 0.19 | 5.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 4.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 5.49 | 0.00 |

| Distance from coastline | 0.00 | -0.13 | -5.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.08 | -4.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.06 | -2.13 | 0.03 |

| Orientation | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.13 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.76 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.74 | 0.46 |

| Altitude | 0.00 | -0.02 | -2.13 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.86 |

| Slope | 2.78 | 0.04 | 8.59 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 1.61 | 0.02 | 4.22 | 0.00 |

|

NDVI_ MEAN |

6.77 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 5.98 | 0.03 | 1.89 | 0.06 | 5.45 | 0.03 | 1.73 | 0.08 |

| Precipitation | 1.21 | 0.03 | 1.42 | 0.16 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 2.13 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 3.89 | 0.00 |

| LST_DAY- LST_NIGHT |

0.22 | 0.02 | 2.01 | 0.04 | -0.12 | -0.01 | -0.82 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 1.30 | 0.20 |

| T_max | 0.50 | 0.01 | 1.38 | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 1.53 | 0.13 | 4.03 | 0.14 | 8.05 | 0.00 |

| T_max-T_min | -1.03 | -0.03 | -3.18 | 0.00 | -0.76 | -0.03 | -1.95 | 0.05 | -3.55 | -0.09 | -7.83 | 0.00 |

| NDBI | -1.90 | -0.01 | -0.87 | 0.38 | -1.92 | 0.02 | 1.61 | 0.11 | -1.00 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.25 |

| UHIE_ NIGHT |

-0.02 | 0.00 | -0.13 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 2.28 | 0.02 | -0.27 | -0.01 | -1.08 | 0.28 |

| Impermeable area | -15.53 | -0.15 | -12.84 | 0.00 | -25.96 | -0.25 | -17.79 | 0.00 | -15.74 | -0.15 | -10.93 | 0.00 |

| Artificial area | -80.61 | -0.83 | -64.97 | 0.00 | -72.64 | -0.75 | -49.37 | 0.00 | -81.32 | -0.83 | -56.55 | 0.00 |

| Night Light | -0.03 | -0.02 | -2.55 | 0.01 | -0.02 | -0.01 | -1.33 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.62 |

| Independent variable | R2 | B | Beta | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.68 | 4.40 | 0.00 |

| T_max | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.81 |

| T_min | 0.08 | -0.01 | -0.28 | -1.39 | 0.18 |

| LST_day | 0.06 | 0.00 | -0.24 | -1.14 | 0.27 |

| LST_night | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| Year | Top edge | R2 | Bottom edge | R2 | Straight edge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | y=0.0991x+2.5046 | 0.7510288 | y=-0.0258x+2.2563 | 0.1790952 | x=-0.1705 |

| 2012 | y=0.0261x+2.4428 | 0.2359837 | y=-0.0841x+2.2153 | 0.5709729 | x=-0.2341 |

| 2018 | y=0.113x+2.6567 | 0.375945 | y=-0.1641x+2.1339 | 0.6198449 | x=-0.3823 |

| Year | 2006 | 2012 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Precipitation | 2.49 | (12.01) | 2.44 | (11.43) | 2.64 | (14.00) |

| Min Precipitation | 2.26 | (9.59) | 2.24 | (9.35) | 2.16 | (8.67) |

| Intersection point_Precipitation | 2.31 | (10.05) | 2.39 | (10.90) | 2.44 | (11.51) |

| Intersection point_Min NDVI | -1.99 | (0.14) | -2.06 | (0.13) | -1.89 | (0.15) |

| Max NDVI | -0.19 | (0.83) | -0.24 | (0.79) | -0.16 | (0.85) |

| Straight edge length | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.48 | |||

| Wet edge slope | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.11 | |||

| Dry edge slope | -0.03 | -0.08 | -0.16 | |||

| Top triangle area | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.17 | |||

| Bottom triangle area | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.24 | |||

| Total area | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.41 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).