1. Introduction

As the global push for sustainability gains accelerates, it has become increasingly clear that individual efforts, though valuable, are insufficient for achieving comprehensive sustainable development. Communities are critical in this transition, as collective action and shared resources provide the foundation for large-scale change [

1,

2]. Initiatives such as car-sharing programs, cycling infrastructure, bringing nature into cities, making city centres car-free and community-led heating networks offer eco-friendly alternatives, improve energy efficiency, and reduce emissions. However, these initiatives can only succeed through collective effort, which highlights the indispensable role of communities in achieving sustainability goals.

Despite this, the shift toward sustainable practices at the community level faces significant challenges [

3]. Resistance to change is common, as established habits are difficult to alter [

4]. Moreover, polarisation often emerges due to conflicting perspectives on what sustainable development should entail [

5]. This polarisation is further exacerbated by underlying social issues such as income inequality, job insecurity, and disparities in access to necessities [

6]. These factors deepen societal divides, making achieving consensus on sustainability initiatives more difficult. Additionally, the uncertainty surrounding the long-term impacts of new initiatives and the need to balance immediate community needs with environmental goals can lead to hesitation in adopting sustainable practices. Therefore, fostering inclusive participation and engaging a broad spectrum of voices is essential to ensure that sustainable solutions are equitable and supported by the community [

7].

In this context, Agent-Based modelling (ABM) offers a promising approach to understanding and addressing the complex dynamics within communities. ABM has been proven effective in simulating opinion dynamics, where individual agents’ behaviours and interactions give rise to collective phenomena such as polarisation, conformity, and decision-making [

8,

9,

10]. By modelling the influence of social networks and community behaviour, ABM sheds light on how collective opinions form and how the spread of polarised information can intensify divisions within networks [

11].

Recent studies underscore the potential of ABM to tackle these societal challenges. For instance, by simulating scenarios in which strong conformity may silence vulnerable groups, ABMs can help us understand how certain voices are excluded, and how diversity, new information, as well as minority voices affect the decision-making processes [

12]. Research has also explored the interplay between conformity and anti-conformity, highlighting how these dynamics can polarise society and complicate democratic decision-making [

13]. This focus on understanding polarisation is crucial to developing strategies that promote inclusivity and social cohesion in the context of sustainability.

While research on opinion dynamics and polarisation has made significant strides, a critical gap remains in translating these insights into practical solutions for community-level democratic processes. Törnberg et al. highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the root causes of polarisation to foster greater social cohesion [

14]. Addressing this challenge requires tools that not only analyse polarisation but also provide actionable insights for communities. Agent-based modelling (ABM) presents an ideal solution by offering a virtual environment where various scenarios can be tested without real-world risks. Through these simulations, stakeholders can visualise complex social dynamics and assess the potential outcomes of policy interventions, leading to more informed and collaborative decision-making [

15].

The evolution of ABM has also allowed researchers to simulate community interactions in increasingly realistic settings. For example, models now account for thousands of individuals, enabling researchers to explore the complex behaviours that shape community dynamics and the policy implications [

16]. These simulations provide policymakers with a controlled environment in which to test interventions, supporting evidence-based decision-making [

15].

Moreover, a growing body of literature underscores the utility of ABMs in various domains, including social-ecological systems, community democracy, and participatory governance [

17,

18]. Systematic reviews have highlighted ABMs’ value in real-world case studies, particularly in analysing the interactions between social and ecological components, offering critical insights into sustainable community practices [

17]. By modelling individuals or organisations as agents whose interactions produce broader social outcomes, ABMs effectively capture community-level dynamics, making them invaluable for understanding how local interactions shape democratic processes and governance [

18].

Building on these insights, our study aims to utilise the potential of ABM to develop a dialogue tool that fosters inclusive and cooperative decision-making within communities [

19]. By simulating the interactions of diverse stakeholders and groups, this tool will facilitate open dialogue, enabling individuals to visualise how their decisions impact others. This transparency encourages a cooperative approach rather than a competitive one. Additionally, the tool will raise awareness by illustrating how individual actions influence collective outcomes, thereby promoting empathy and shared understanding within the community.

Through this novel application of ABM, our study seeks to uncover an accessible way in the root causes of polarisation, assess its impact on social cohesion, and explore strategies to enhance inclusivity in democratic processes. By doing so, we hope to provide a meaningful contribution to both the theory and practice of sustainable community governance.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Role of Democracy in Sustainability

Democracy plays a crucial role in advancing sustainability by fostering transformative practices across various societal dimensions. The effectiveness of democratic processes can either facilitate or hinder sustainability transformations, encompassing institutional, social, economic, technological, and epistemic aspects [

20].

Democratic innovation (DI) is essential to address sustainability challenges and involve the development of new practices to enhance citizen engagement and deliberation within governance frameworks [

21]. Active citizen involvement in decision-making can promote inclusive and transparent dialogues among diverse interest groups [

22].

Traditional governance models often struggle to respond effectively to sustainability issues due to the interdependent nature of ecological and social systems [

23]. In contrast, democratic innovations—such as participatory budgeting and citizen assemblies—offer promising alternatives by actively engaging a wide array of voices in decision-making [

24].

By integrating democratic principles into sustainable development efforts, communities can collaborate on solutions that reflect their unique needs and values. Additionally, creating opportunities for meaningful participation enables citizens to voice their priorities and concerns, potentially resulting in more effective and realistic policies.

2.2. ABM Enhancing Participation in the Democratic Process

Complementing democratic innovation (DI) is the concept of participatory modelling (PM), which emphasises the active participation of stakeholders in the modelling process. PM provides a dynamic platform that allows stakeholders to integrate local knowledge, insights, and preferences, thereby promoting collaborative learning and more accurate representations of social and ecological dynamics [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The relationship between PM and DI is symbiotic [

29], as both approaches aim to empower citizens and stakeholders to participate in governance processes.

Among the approaches used in participatory modelling (PM), Agent-Based modelling (ABM) stands out [

30]. ABM simulates system behaviours and changes over time by modelling individual behaviours and the interactions among them, thereby revealing macro-level patterns [

31]. The advantage of ABM is that it allows stakeholders to visualise complex social dynamics and evaluate the impact of different policy interventions or decisions under various scenarios. This scenario exploration capability makes ABM very effective in facilitating constructive dialogue among different stakeholders, allowing them to understand how individual behaviours and decisions affect collective outcomes. In addition, ABM’s ability to model and simulate potential outcomes under various conditions provides a dynamic platform for interactive discussions, which may promote a shared understanding of challenges and opportunities in democratic systems. This not only promotes more informed decision-making but also collective growth, as stakeholders can gain a deeper understanding of the interconnections between their actions and broader social dynamics [

32,

33].

By combining ABM with democratic innovation, gaps in understanding between stakeholders can be bridged and communication can be facilitated by providing a neutral, evidence-based platform to explore complex issues, prevent or reduce polarisation, and promote collaboration [

34]. Through this process, ABM also supports ongoing policy development and research on social dynamics [

17,

35].

In sum, the use of ABM in democratic innovation provides a path to a more inclusive democracy by allowing stakeholders to collaboratively explore scenarios and engage in informed discussions. Our goal is to use ABM as a tool to promote constructive dialogues during decision-making in local democratic processes.

2.3. HUMAT as an Architecture of the Dialogue Tool

Agent-based modelling (ABM) offers a robust framework for researchers to simulate individual agents with diverse characteristics and behaviours, enabling an investigation into how micro-level interactions contribute to macro-level phenomena such as group polarisation [

9].

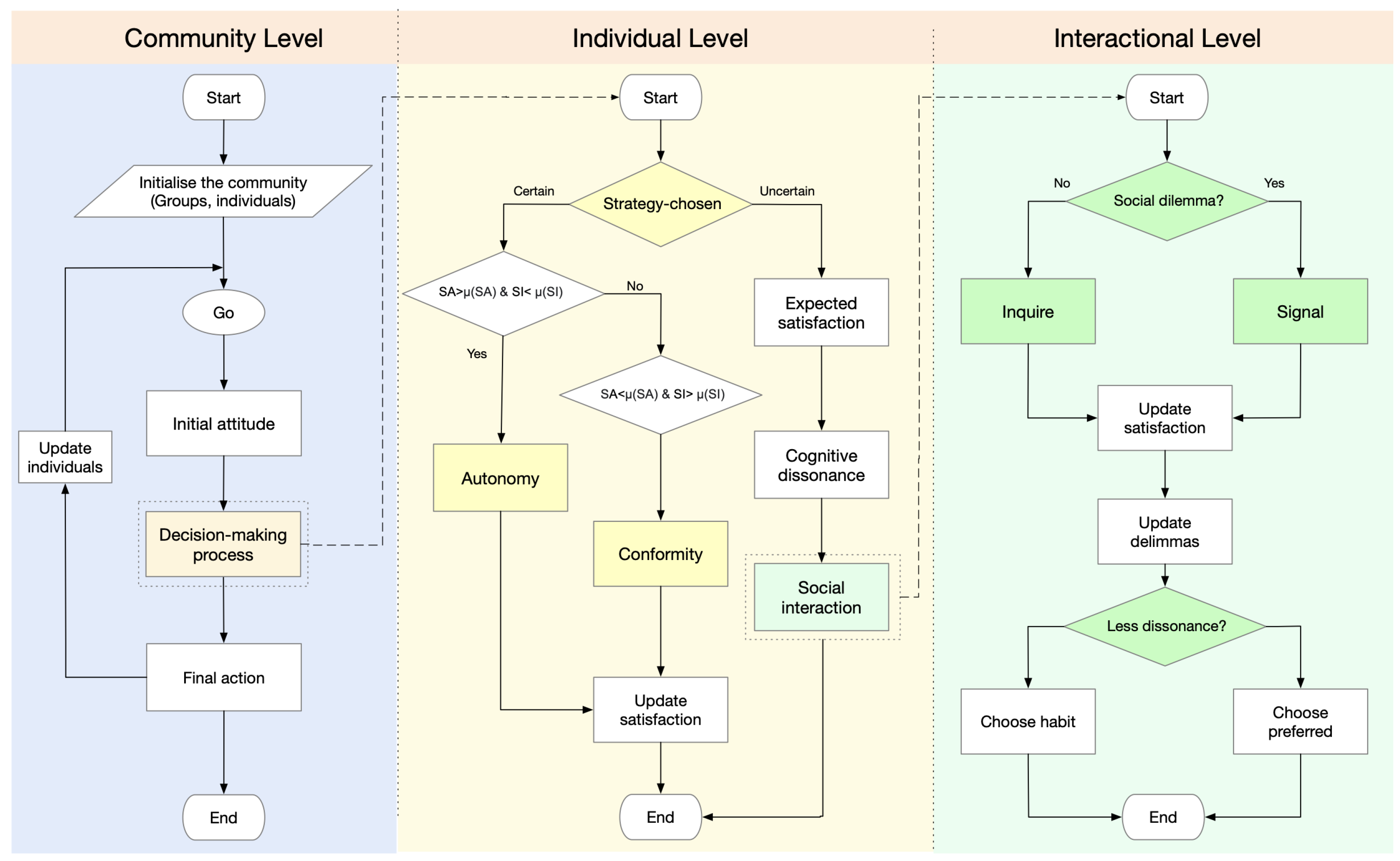

At the core of our dialogue tool is the HUMAT agent-based framework, which serves as a foundational architecture for constructing artificial populations and modelling social dynamics with agent-based simulations. The HUMAT framework emphasises the complexities of agent cognition, decision-making processes, and social interactions grounded in social scientific theory [

36]. It allows for the simulation of social phenomena such as social innovations, opinion dynamics, and behavioural transitions [

37].

In this framework, agents act within social networks and make decisions that are influenced by their personal experiences, the information they share, prevailing societal norms [

38], and deeply held values. The interaction of these factors leads to the formation of opposing opinion groups and ultimately to a tipping point that favours a particular norm.

The initiation of agent activity within the HUMAT architecture unfolds through multiple stages, based on the satisfaction or dissatisfaction derived from various behavioural alternatives. These alternatives are categorised into short-term experiential needs, social needs [

39], and more stable intrinsic values. This categorisation introduces the potential for trade-offs among different groups of needs, affecting the cognitive dissonance experienced by agents and shaping their information processing and subsequent actions [

40,

41]. When agents evaluate the satisfaction levels among the available alternatives, HUMAT promotes the selection of the most satisfying option. In situations where alternatives produce similar levels of satisfaction, HUMAT considers the cognitive dissonance that each option may induce.

HUMATs tend to choose the option that requires the least cognitive effort to mitigate dissonance. Ongoing cognitive dissonance drives agents to explore their social networks, seeking additional information to resolve the dissonance or find better alternatives. In the context of opinion dynamics, agents experiencing dissonance have two main strategies to mitigate this tension: they may try to persuade relevant agents to adopt their view (signalling) or seek information from relevant agents to support their view (inquiring). HUMATs maintain cognitive representations of past evaluations of potential alternatives, resulting in a dynamic personal ranking of these options. The evolution of the memory stack is influenced by experience satisfaction, outcome weighting, the addition of new outcomes, and current focus demands. This evolving memory system provides comprehensive insights into how HUMATs capture and process information in response to decision dynamics, ultimately providing a more sophisticated understanding of how local democratic processes unfold.

The HUMAT framework has been and is being used in multiple projects to address empirical cases of community dynamics. Initially, HUMAT was developed within the EU SMARTEES project to address the dynamics of local social innovation [

42]. Different empirical applications have been implemented [

37,

43].

In summary, the dialogue tool based on the HUMAT framework leverages ABM to model complex interactions and decision-making processes within communities. By understanding the cognitive and social dynamics therein, the tool aims to promote inclusive dialogue and informed decision-making, thereby increasing the effectiveness of democratic processes at the community level.

2.4. Individual Opinion and Group Categorisation

In order to develop a dialogue tool that can effectively promote open dialogues among diverse groups and strengthen community-based democracy, it is essential to extend the HUMAT architecture to incorporate not only individual opinions but also the dynamics of group categorisation. The evolution of individual opinions and the categorisation of groups play a crucial role in shaping collective behaviours and interactions, which in turn influence community decision-making and democratic processes. Understanding community dynamics requires attention to how individual opinions evolve and how people categorise themselves and others into social groups.

Group categorisation is rooted in Social Identity Theory, which describes the division of oneself and others into social groups based on shared characteristics [

44]. This cognitive process creates boundaries between in-groups (the group with which an individual identifies) and out-groups (groups that are viewed as different) [

45]. Such categorisation influences attitudes and behaviours, often leading to favouritism toward in-groups and devaluation of out-groups, which can lead to conflict, stereotyping, and discrimination within communities.

As for the evolution of individual opinions, Vande et al. highlight how personal attitudes transform over time and are influenced by social interactions, information processing, and the opinions of others [

46,

47]. Central to this understanding is Social Influence Theory, which posits that individuals adapt their opinions through channels such as persuasion, conformity, and seeking similarity with peers. Simulation models can help study these dynamics and understand how individuals contribute to consensus-building [

48].

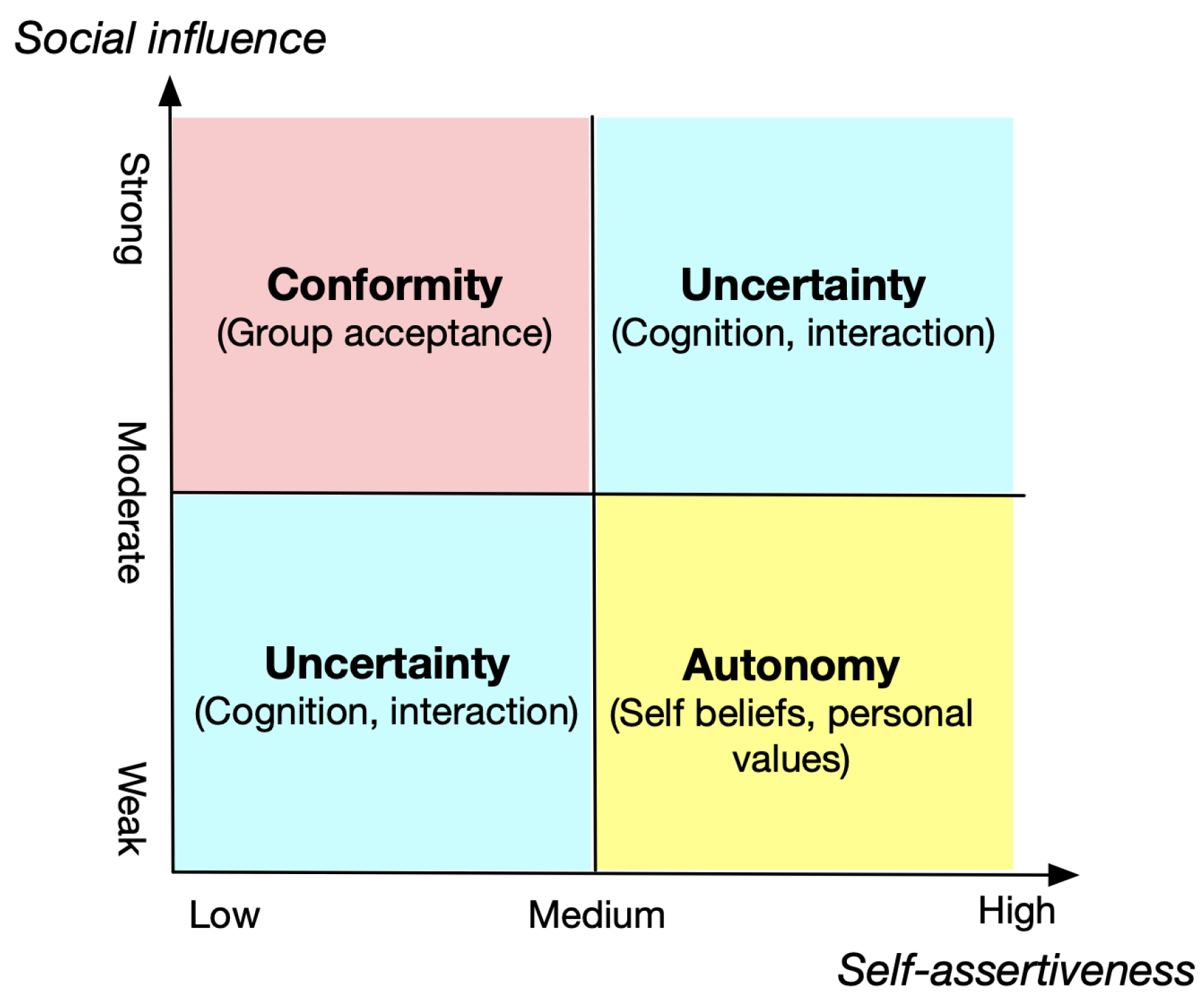

In contrast, self-assertiveness is an important counterpart to social influence. This concept refers to an individual’s capacity to confidently express their opinions and advocate for their needs while respecting others’ autonomy [

49]. The relationship between social influence and self-assertiveness is complex; assertive people can face social pressure while maintaining their independence, which is critical for cultivating personal autonomy in social interactions, enabling individuals to constructively participate in community dialogue.

Our overarching goal in extending the HUMAT architecture is to create a dialogue tool that captures key aspects of the complex dynamics of individual opinion evolution and group categorisation. This tool will account for the interplay between social influence, self-assertiveness, and cognitive processes that shape group dynamics. By integrating individual characteristics with group properties, the extended HUMAT framework will provide valuable insights into interactions among groups in communities. This approach aims to deepen theoretical understanding while providing practical applications for fostering inclusive dialogue across diverse contexts. Ultimately, our goal is to enable communities to harness their dynamics and contribute to more cohesive and participatory democratic processes.

4. Results

4.1. Investigation with the Dialogue Tool

4.1.1. Simulation Design

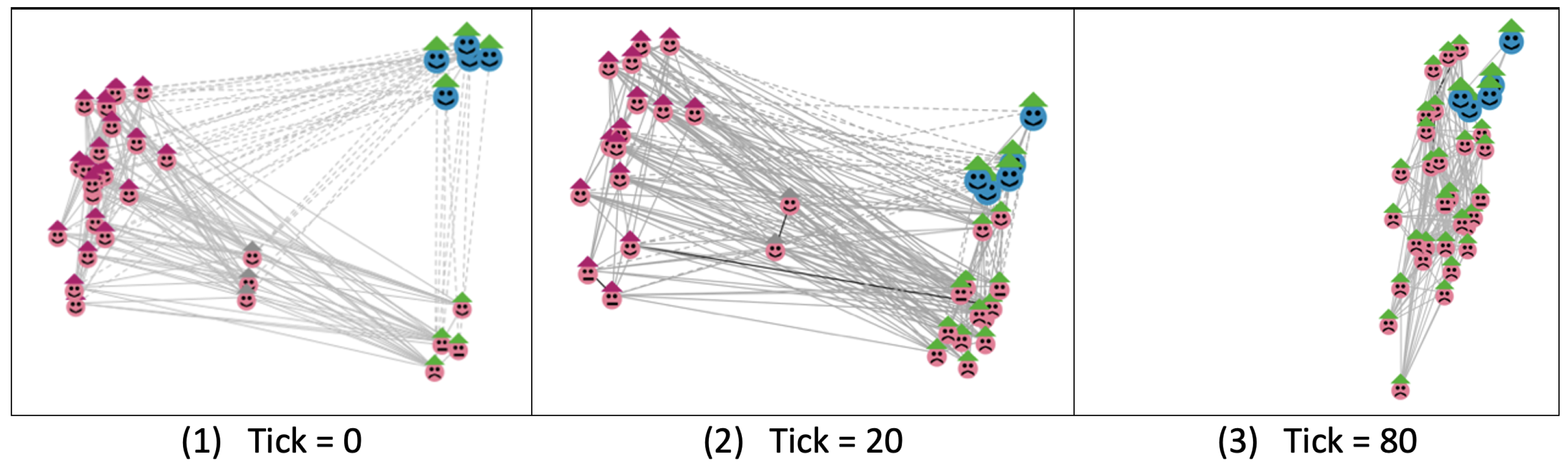

In a hypothetical scenario, a local government proposes the construction of a wind farm, prompting the surrounding community to engage in a participatory decision-making process. This proposal initiates a debate involving several considerations, including experiential needs such as noise, shade patterns and safety, as well as values such as aesthetics, emission reductions () and ecological impacts (bird fatalities). As a result, individuals within the community take different positions on the wind farm project, ranging from support, and neutrality to opposition, depending on their expected experiences (noise, profit), values, and the opinions of their friends and neighbours.

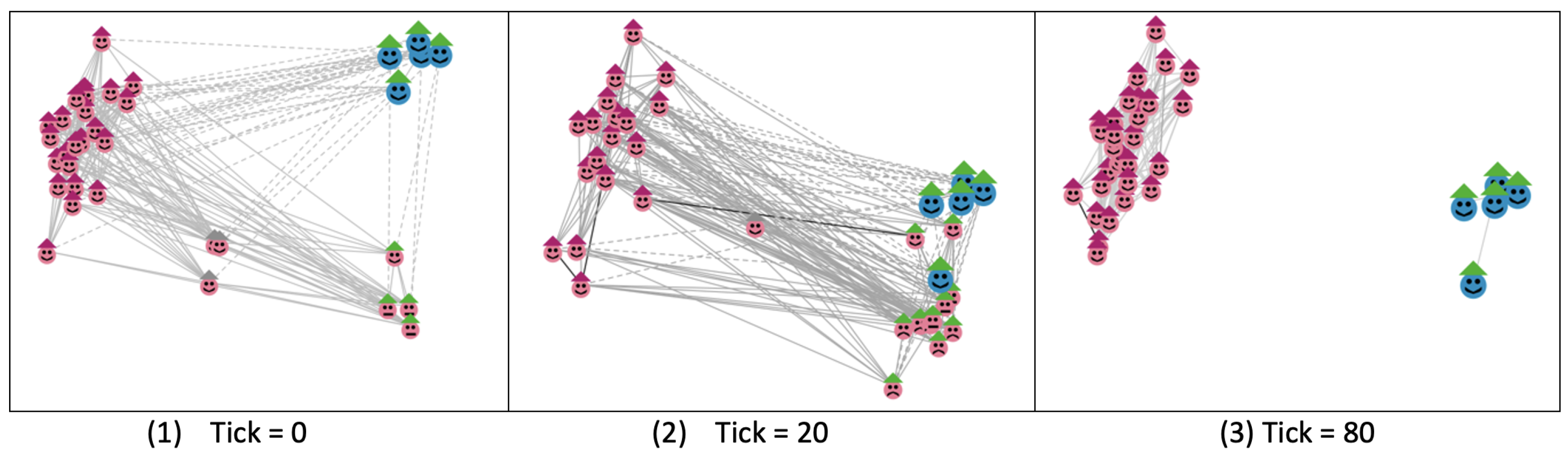

Our experiments aim to simulate diverse community dynamics, where individuals (represented by heads) exhibit unique attributes and engage in decision-making regarding a proposed wind farm. In this simulation, individuals express their opinions with the colour of their hats as follows: Green for support, Grey for neutrality, and Red for opposition. Facial expressions represent their emotional state, indicating satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or indifference, while the size of their heads indicates the varying levels of vocal expression.

The relationships between individuals are visually represented through connecting lines: Dashed lines signify relationships between members of different groups. Solid lines represent connections within the same group. The strength of these connections evolves, reflecting the frequency of interactions: Darker lines indicate more frequent interactions. Lighter lines represent less frequent engagement. Lines may even disappear altogether if no interaction occurs over a long period.

As individuals interact and influence one another, their positions within the community shift based on two factors: The

horizontal position reflects the extent of support for the wind farm, with individuals moving further to the right as they become more supportive. The

vertical position represents satisfaction, with individuals positioned higher up as they become more satisfied (see

Figure 3).

By using visual elements such as facial expressions, head sizes, and connecting lines, we can effectively examine how relationships and interactions shape the overall consensus or division within the community. This model allows us to explore how individuals influence each other and the resulting shifts in opinion over time.

We specifically investigate the following scenarios: 1) Unsatisfied Supporting Community: A situation where individuals support the wind farm but remain dissatisfied; 2) Divided Community: A polarised community with stark divisions between supporters and opponents. 3) Reconciled Community: A community where interactions lead to convergence and consensus.

4.1.2. Calibration of Group Attributes and Individual Variables

In our community representation, we delineate two distinct groups. Each individual holds the right to participate in decision-making. The community consists of 35 individuals, divided into Group Pink (depicted by

pink faces) and Group Blue (depicted by

blue faces), as detailed in

Table 1.

The simulation spans 80 rounds and reflects the temporal evolution of the voting process. Individuals are encouraged to participate in discussions, aiming to sway others towards their perspectives. Group Blue employs more assertive and persuasive methods, contrasting with the initially reserved approach of Group Pink.

To configure individual variables, including the importance of different needs and initial satisfaction of experiential needs and values (Antosz, 2019), we use "Openness to Change" (see

Section 3.1.1) as a key parameter. This parameter reflects the group’s overall initial attitude toward the wind farm proposal. The

Openness to Change parameter is scaled between 0 and 1: values below 0.5 signify opposition to the wind farm, while values above 0.5 indicate support for it.

By normalising this parameter, we can quantify the degree of opposition or support for the proposed change within each group. A normal distribution is then applied to evaluate the initial satisfaction levels of each individual in a specific group. These satisfaction levels are influenced by the normalised values that represent support or opposition, as well as the degree of vocalisation among group members.

According to the community setting (

Table 1). Group Pink (

Openness-to-change = 0.2) exhibits higher satisfaction with opposing the wind farm and lower satisfaction with supporting it. The against-value (

) reflects the extent of opposition and is calculated using the following equation:

= (0.5 -

Openness-to-change) / 0.5 = 0.6. For this group,

represents the average individual satisfaction regarding experiential needs and values related to opposition, with a standard deviation of 0.5. Conversely, the satisfaction associated with the support value of this group has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

In contrast, Group Blue (Openness-to-change = 1) shows greater satisfaction with supporting the wind farm and lower satisfaction with opposing it. The for-value () illustrates the extent of support for the change and is also normalised according to the Openness to Change parameter, calculated using the equation: = (Openness-to-change - 0.5) / 0.5 = 1. For this group, represents the average individual satisfaction regarding experiential needs and values associated with the support, also with a standard deviation of 0.5. In contrast, the satisfaction associated with the opposition value has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

The detailed settings of initial satisfaction and importance for different needs for individuals in Groups 1 and 2 are outlined in

Table 2.

4.2. Scenario 1: Individual Silence Results in “Silencing” of Opposing Opinions

In the initial setup of the simulation, members of Group Pink (depicted by pick faces) exhibited low assertiveness, reflected in a self-assertiveness parameter of 0.1. This limited assertiveness made them more susceptible to conforming to group norms, leading to a weaker commitment to their original viewpoints. Accompanied by a vocalisation score of 0.1, their opinions were less effectively communicated. In contrast, individuals in Group Blue (depicted by blue faces) displayed significantly higher levels of assertiveness, characterised by a self-assertiveness parameter of 1. This heightened determination allowed them to maintain their positions firmly, supported by a vocalisation score of 1, ensuring their voices were heard clearly.

The results of the simulation are depicted in

Figure 3, illustrating the evolution of community support for the wind farm proposal across three key time points: ticks 0, 20, and 80. At the start of the simulation (tick 0), Group Pink was predominantly opposed to the wind farm, while Group Blue exhibited strong support. This initial stage showcased a stark contrast between the groups, with Group Pink resisting the change advocated by Group Blue. As the simulation progressed, a notable shift occurred, with many individuals from Group Pink transitioning to support the wind farm proposal, reflecting the influence of Group Blue’s assertiveness and vocalisation.

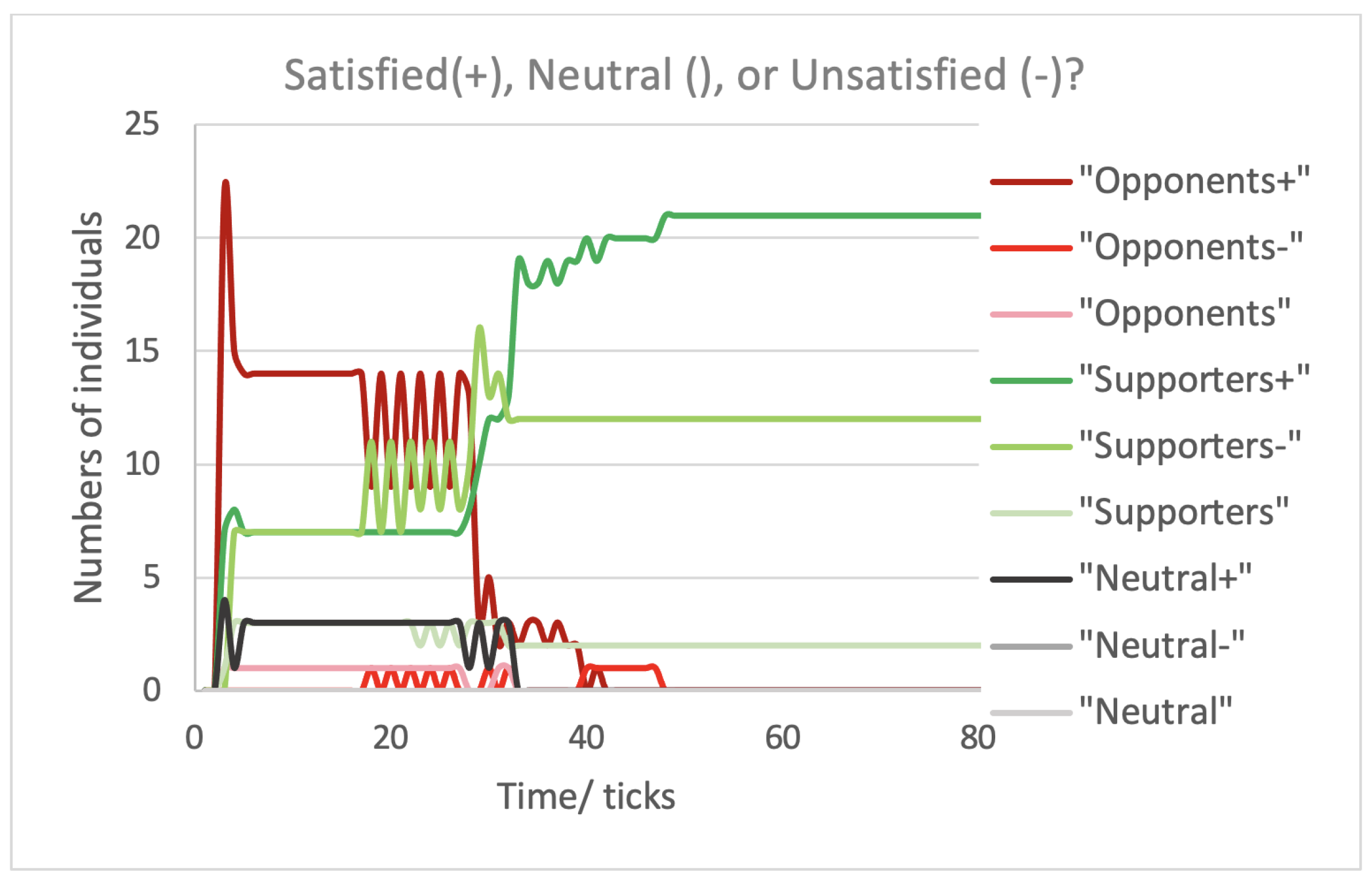

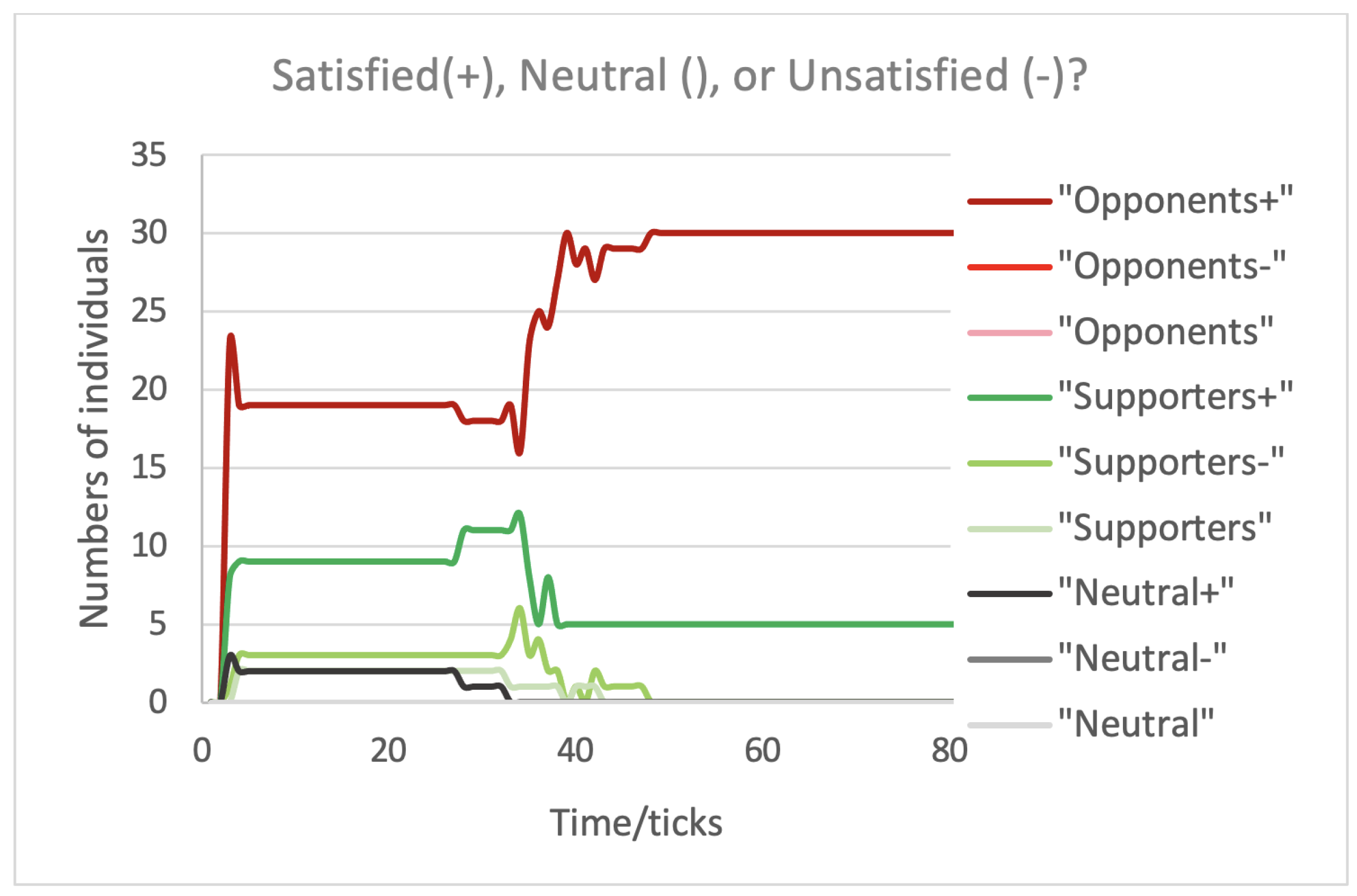

By the end of the simulation (tick 80), as illustrated in

Figure 4, the transformation within the community was complete: all members of Group Pink had adopted a supportive stance toward the wind farm.

Figure 4 further illustrates the distribution of

satisfied (+),

neutral and

unsatisfied (-) individuals over time. Notably, there was an intense period of change between ticks 20 and 40, during which many agent states fluctuated rapidly. Although the simulation concluded with unanimous support for the wind farm, it is crucial to highlight that a significant minority—34.3% of the population—reported dissatisfaction with the project.

The findings indicate that this dissatisfaction suggests a lack of genuine belief in the wind farm proposal among many supporters. Instead, their alignment appears to stem more from social conformity rather than authentic belief. This social dynamic process highlights a critical distinction between superficial consensus and genuine support, emphasising the importance of understanding the underlying satisfaction levels within the community.

Moreover, the results highlight the impact of assertiveness and vocalisation in shaping community dynamics. Members of Group Blue, due to their higher assertiveness, were able to maintain their positions despite pressure from the larger, initially opposing group.

Ultimately, these simulation results emphasise the necessity for deeper engagement and dialogue among community members to understand true satisfaction levels and foster meaningful participation in decision-making processes. Addressing the complexities of community dynamics is essential for achieving authentic outcomes, and ensuring that all voices are heard and valued. The simulation serves as a reminder that while community consensus may appear achieved, underlying dissatisfaction and conformity can complicate the true dynamics at play.

4.3. Scenario 2: Self-Assertiveness May Lead to Polarisation

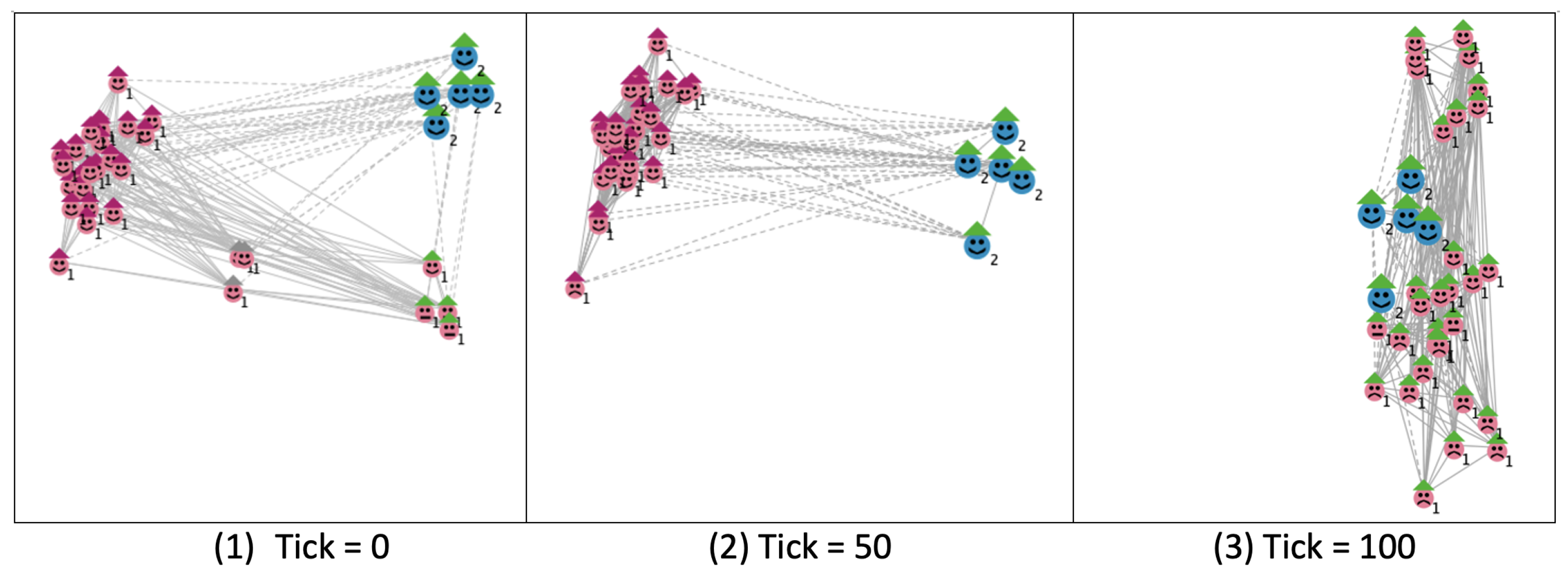

In the second scenario, we explored how a slight increase in individual assertiveness would influence community dynamics. The setup remained consistent with the previous experiment, except for a small adjustment—Group Pink’s assertiveness was increased to 0.2, while Group Blue’s parameters remained unchanged.

At the outset of the simulation, most of Group Pink opposed the wind farm proposal, while Group Blue members strongly supported it. However, as time passed, the community transitioned into a distinctly divided state. Group Pink, with its increased assertiveness, solidified its opposition to the proposal, while Group Blue maintained its strong support. This stark division between the groups became evident, as depicted in

Figure 5, where each group entrenched itself in its initial stance.

The key observation in this scenario was that a slight increase in assertiveness among Group Pink resulted in a marked reduction in the fluctuation of individual opinions. This stabilisation of viewpoints contributed to an unintended consequence: the polarisation of the community. As members of Group Pink grew more assertive, they became increasingly resistant to external influences, leading them to confine themselves within their own social bubbles. Consequently, they interacted primarily with others who shared their perspectives, reinforcing their existing beliefs and creating a more insular environment.

As the simulation progressed, Group Pink emerged as "

satisfied opponents", content within their own group dynamics (see

Figure 6). They found comfort in the reinforcement of their shared opposition to the wind farm proposal. This internal satisfaction was characterised by a solidified identity and a sense of belonging, despite the ongoing discussions surrounding the wind farm. In contrast, Group Blue remained as "

satisfied supporters", actively advocating for the wind farm and maintaining their connections with like-minded individuals. The assertiveness of Group Blue continued to reflect their strong support, further deepening the divide between the two groups.

It is essential to note that these observations occurred before the ultimate decision regarding the wind farm proposal. The simulation did not take into account the post-voting dynamics that would arise once a collective decision was made. The satisfaction levels of both groups would be directly influenced by whether the wind farm plan was implemented or rejected. The potential outcomes for Group Pink and Group Blue could create a scenario where Group Blue would feel validated as "winners" if the proposal passed, while Group Pink might experience dissatisfaction as "losers".

While this scenario strengthened group solidarity, as illustrated in

Figure 5, the overall impact on the community was negative (

Figure 6). The polarisation created a sharp divide between the groups, with limited interaction or exchange of ideas between them. This division undermined community cohesion and made collaboration and mutual understanding more difficult. In turn, the polarised state hindered the potential for collective decision-making and impeded progress on the wind farm proposal and other communal issues.

The simulation highlights the potential consequences of increased assertiveness in community dynamics. While such assertiveness can strengthen in-group solidarity, it simultaneously fosters polarisation and the formation of isolated social bubbles. This dynamic poses a threat to the overall well-being of the community by reducing opportunities for dialogue, cooperation, and common understanding.

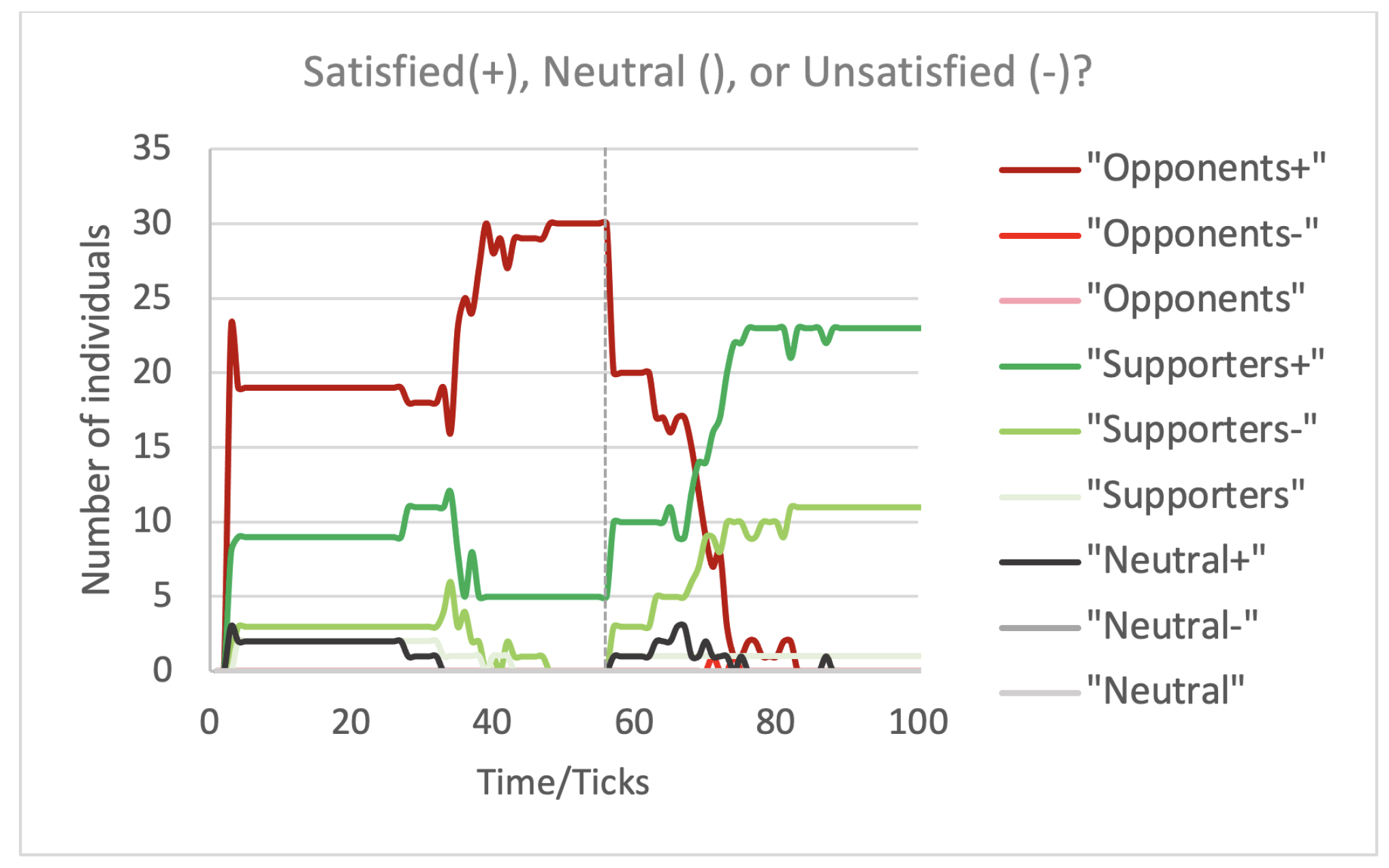

4.4. Scenario 3: From Polarisation to Reconciliation

In the third scenario, we aimed to explore methods for reconciling a divided community around the wind farm proposal. Imagine that, at a certain point, the government takes action by providing community education on wind farm safety and involving residents in decisions about the placement and visual aspects of the wind farm. These actions were intended to improve Group Pink’s (depicted by pink faces) experiential and value satisfaction, encouraging more interaction and communication within the community.

In the simulation, we utilised the dialogue tool while maintaining the same community setup as in the previous scenario: Group Pink had lower openness to change, while Group Blue was more open. However, at tick 50, we introduced an intervention aimed at enhancing Group Pink’s (labelled as “1”) satisfaction for supporting the change, while keeping their assertiveness low. This intervention was designed to address their concerns, extend the decision-making process, create opportunities for dialogue, and foster more meaningful interactions between Group Pink and Group Blue.

As shown in

Figure 7, the initial simulation mirrored the previous scenario, where Group Pink was predominantly opposed to the wind farm, and Group Blue was strongly supportive. By tick 50, the community had become deeply divided, with both groups firmly entrenched in their opposing views. At this stage, we implemented the intervention, which involved addressing Group Pink’s concerns and facilitating communication between the two groups.

Following the intervention, we observed a significant shift in community dynamics. Beginning around tick 60, individuals in Group Pink began to reconsider their opposition and gradually shifted towards supporting the proposal. The intervention helped increase satisfaction and communication, leading more members of Group Pink to align with Group Blue’s supportive stance. By the end of the simulation, all members of Group Pink had adopted a supportive position (see

Figure 8).

However, despite this consensus, not all individuals were fully satisfied. Some members of Group Pink expressed support for the wind farm due to social conformity rather than genuine belief in the project. Although they conformed to the majority view within their group, their experiential and value-based needs remained unmet, leading to lingering dissatisfaction even in the presence of overall agreement.

This outcome highlights the partial effectiveness of targeted interventions in reducing polarisation and promoting community cohesion. While the intervention succeeded in bringing about consensus, it also revealed the risk of superficial agreement, where individuals align with the group without truly addressing their personal concerns.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Simulation Results

The simulation results across the three scenarios—unsatisfied community, divided community, and reconciled community—provide critical insights into the dynamics of community engagement and decision-making, particularly in the context of contentious developments where different groups in a community can have different perspectives and will experience different outcomes depending on if and how a plan, e.g., the placing of a wind farm, is implemented. By examining the interactions among community members with varying openness to change, levels of assertiveness and vocalisation, this simulation illuminates the factors that influence community satisfaction, cohesion, and consensus.

In the unsatisfied community scenario, Group Pink (depicted in pink faces) displayed low assertiveness, predominantly opposing the wind farm proposal. The findings highlighted that individuals with limited vocalisation tend to conform to prevailing group norms, resulting in dissatisfaction and a sense of marginalisation. Despite Group Blue (depicted in blue faces)’s strong support for the proposal, the lack of acknowledgement of Group Pink’s concerns created underlying tensions, emphasising the necessity for inclusive decision-making processes that respect and validate all community voices.

The divided community scenario illustrated a significant polarisation in community dynamics. An increase in Group Pink’s assertiveness resulted in entrenched positions, with Group Pink becoming more determined to oppose the proposal while Group Blue maintained its support. This scenario demonstrated how heightened assertiveness can restrict individual opinion fluctuations, leading to social isolation and a lack of collaboration. Such polarisation undermines collective decision-making, underscoring the urgent need for strategies that foster cross-group communication and understanding.

In the reconciled community scenario, targeted interventions were introduced to address Group Pink’s concerns and enhance their satisfaction. The simulation indicated that these interventions effectively facilitated dialogue and interaction between the two groups, leading to a gradual shift in Group Pink’s stance toward support for the proposal. However, the presence of "support without satisfaction" among some Group Pink members highlighted the complexities involved in achieving true consensus. Their alignment with Group Blue was often driven by social conformity rather than genuine belief, emphasising the importance of addressing deeper emotional needs.

Community dynamics can be both fluid and volatile. While there may be an initial convergence toward consensus, this can swiftly revert to division without continuous engagement and acknowledgement of individual concerns [

59]. It is important to recognise that, whether using a dialogue tool or in real-life situations, once a vote is cast, the results are typically fixed. However, individual opinions may still fluctuate between opposition and support after the voting process, although our focus does not delve into those dynamics here.

Our findings underscore the essential need for inclusive strategies that empower all community members to voice their aspirations and anxieties. These insights are invaluable for policymakers and community leaders navigating the complex landscape of community decision-making.

5.2. Reflection on the Investigation with the Dialogue Tool

The primary objective of the dialogue tool is not to perfectly replicate real-life scenarios but to create diverse simulations that illustrate community dynamics and potential outcomes under specific conditions [

19]. This approach fosters meaningful discussions regarding the implications of various community dynamics and decision-making processes.

Our study sheds light on the intricate dynamics of opinion formation, emphasising the interplay between individual opinions, group dynamics, and social influences [

60]. It reveals how social pressure can shift individuals from opposition to support, revealing instances of silent dissent and the potential suppression of alternative viewpoints among less vocal participants. Notably, ongoing dissatisfaction among supporters highlights the need to differentiate between surface-level conformity and genuine belief. This distinction emphasises the importance of addressing the deeper experiential and value-based needs of community members.

Additionally, our findings illuminate the detrimental effects of polarisation on community cohesion and progress [

61]. While initial group solidarity may seem beneficial, it ultimately hinders collaborative efforts and collective decision-making.

Importantly, our observations suggest that interventions aimed at increasing satisfaction and mitigating emotional responses can facilitate reconciliation within polarised communities [

62]. The introduction of targeted strategies—such as educational programs, and workshops—has shown promise in bridging divides and reducing polarisation [

63]. This indicates that consensus is more likely to emerge when interventions actively promote dialogue and address community concerns [

64,

65].

In terms of modelling and experimentation, our approach serves not only as an empirical validation tool but also as a theoretical exploration of complex opinion dynamics. While the model is still undergoing empirical calibration, its consistent alignment with established theoretical expectations and social patterns confirms its reliability. Its adaptable design allows for generalisability in different community settings, making it a valuable resource for simulating real-world opinion formation processes. In addition, the dialogue tool has great potential for educational use, providing a unique perspective on social pressure, conformity, and public opinion dynamics. Our experience with the tool demonstrates its practical value in raising awareness of the complex social dynamics that emerge in community discussions. Through quick, intuitive simulations, it engages participants in thoughtfully thinking about how their decisions affect the broader community, especially marginalised groups that are often overlooked in these processes.

During workshop sessions, participants can configure community dynamics and define group properties, which allows for the simulation of various scenarios. This customisable framework facilitates the observation of potential outcomes, enables the identification of risks associated with unfavourable scenarios, and fosters the development of strategies to mitigate these risks.

Our first experiences using the dialogue tool with students, policymakers at the municipality level and citizens involved in a community plan are promising. Whereas the NetLogo interface of the dialogue tool is not the most appealing, users were capable of operating the dialogue tool very quickly using the available instructive material. Especially of interest was the citizen group, which succeeded in representing their case in the dialogue tool in a session of an hour, and reporting a heightened awareness of the critical role of in particular the neutral citizens in their case. Whereas for most users the cases of polarisation were recognisable, the situation where many unhappily support a plan for social reasons was an eye-opener for many users, prompting them to be more aware of reflecting on the outcomes for in particular the less vocal and more vulnerable citizens in their community. As such the dialogue tool seems to support the democratic process. Further testing of the dialogue tool in citizen assemblies is projected in the INCITE-DEM project [

66].

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

The current implementation of the dialogue tool is built on agent-based simulations, which, while powerful, come with inherent limitations. One key limitation is the abstraction of real-life complexity into simplified assumptions [

67]. While this helps illustrate broad patterns of behaviour and interaction, it may not capture the full range of human emotions, social networks, and the socio-political contexts or other external factors that influence decision-making in real communities. These simplifications limit the model’s capacity to represent the full complexity of decision-making processes in the real world. However, it should be noted that relatively simple simulations are easier to use and understand, and as such may be more effective in conveying knowledge regarding social dynamics in communities. As a consequence of that, we develop a very simple interface for citizens to play with and a more elaborate interface for policy-makers having a deeper interest in testing a larger variety of cases.

Another challenge is the tool’s empirical calibration. The underlying HUMAT framework has been and is being used in several projects to study empirical cases of community dynamics [

66,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72]. The model’s behaviour aligns with theoretical expectations and has been tested against real-world data. However, regarding validation, we emphasise that this remains a challenge in the context of complex social dynamics, and in particular the predictive use of models in such situations is fundamentally limited [

73]. Hence, it remains unclear how closely the simulated dynamics reflect actual community behaviours and attitudes, particularly in contentious situations such as wind farm development or other contentious public decisions. Although the dialogue tool is not designed to predict specific outcomes but to foster discussion and insight, this limitation is important to emphasise, considering that many practitioners expect models to provide predictions of future developments and potential impacts of policies. Hence in using the dialogue tool, it should be emphasised that the simulations provide a perspective of possible opinion dynamics, which are first and foremost aimed at supporting a constructive dialogue between (groups of) people having different perspectives and interests.

Additionally, the current tool focuses on short-term interactions leading up to a decision but does not account for long-term shifts in public opinion after policies are implemented. It does not include post-decision dynamics regarding how community satisfaction or dissent might evolve. However, people often adapt to new situations, and while the original implementation of a plan may have faced opposition, they tend to grow accustomed to the changes over time. For example, the closure of a park for car traffic in Groningen was very contested (the pro-closure group won a referendum by 50.9%), but 25 years later a massive majority (almost 94%) indicated to be in favour of a car-free park [

43]. For direct dialogues in communities, such a long-term perspective might be less relevant to discuss, as speculating on how people will perceive a plan in 25 years does not contribute to a fruitful discussion about the present. However, for policymakers reflecting on long-term developments, it may be interesting to have a tool that helps to envisage such long-term dynamics.

Expanding the scope of the tool to include long-term simulations and post-decision scenarios would further enhance its usefulness. Simulating how public opinion and community cohesion evolve—especially in response to ongoing interventions or changing sociopolitical conditions—would provide insights into how to maintain consensus and resolve emerging conflicts. This long-term perspective would make the tool an even more powerful resource for decision-makers involved in democratic planning processes.

Given the limitations of simulation models, particularly the relative simplicity of the dialogue tool, it may be beneficial to incorporate additional variables to better capture real-world complexity. For instance, introducing external influences such as media, expert testimony, or leadership roles would enhance the understanding of how these factors shape public opinion and influence consensus-building or polarisation. By incorporating such variables, the tool could offer a more comprehensive analysis of the forces that drive community decision-making. However, a drawback of such an extension would be the difficulty of working with the dialogue tool. As the dialogue tool is developed to be used by practitioners, a balance between usability and realism should guide decisions on what to include and exclude from both the model and the interface.

5.4. Conclusions

In transitioning towards a more sustainable society, many plans will have to be implemented at the community level. Examples of such plans are the development of a wind farm, district heating projects, banning cars (transit traffic) from neighbourhoods and city centres, investing in cycling infrastructure, creating space for nature and planting trees against heat stress in cities. Such plans can elicit heated discussions and may cause conflicts in communities, highlighting the importance of having good community dialogues where the interests of different citizens – in particular, the more vulnerable – are acknowledged, and plans are developed in a more co-creative manner.

The transition to a more sustainable society requires numerous initiatives at the community level. For example, developing wind farms, district heating projects, banning traffic from neighbourhoods and city centres, investing in cycling infrastructure, creating green spaces, and planting trees to mitigate urban heat stress. These initiatives often elicit heated debates and can lead to conflicts within communities. This highlights the urgent need for effective community dialogues that recognise the diverse interests of all citizens, especially those of disadvantaged groups. By promoting more inclusive and co-creative planning processes, such dialogues can help ensure that sustainable development initiatives are not only technically sound, but also socially fair and widely supported.

The dialogue tool, despite its current limitations, provides significant value as a theoretical exploration of community dynamics and decision-making processes. While it is not a predictive model, it holds the potential for stimulating reflective discussions and fostering a deeper understanding of how community interactions unfold in contentious situations. Moving forward, the tool’s development should focus on enhancing its empirical grounding, expanding its scope to include long-term and post-decision scenarios, and incorporating more complex variables. By doing so, it could become a more robust tool for policymakers, empowering citizens, and fostering inclusive dialogue that enhances both community satisfaction and collective decision-making.