Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

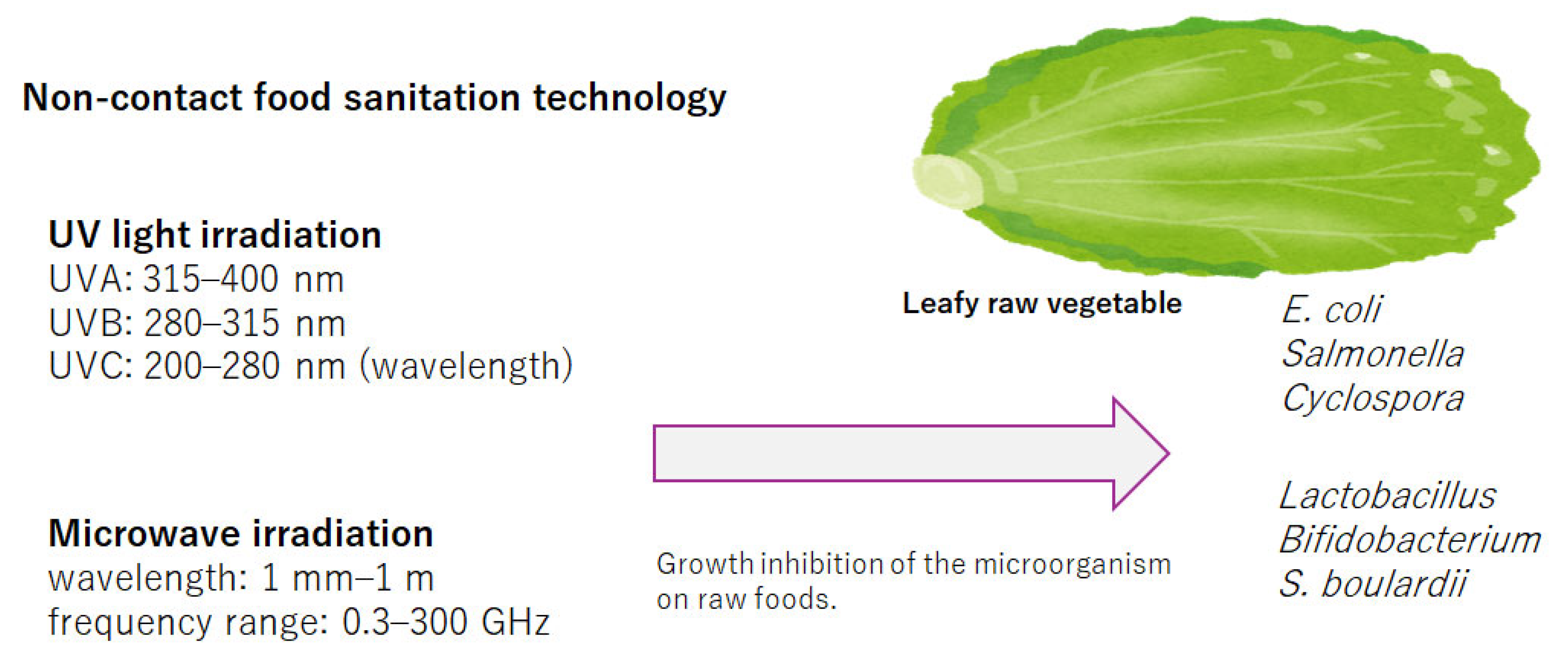

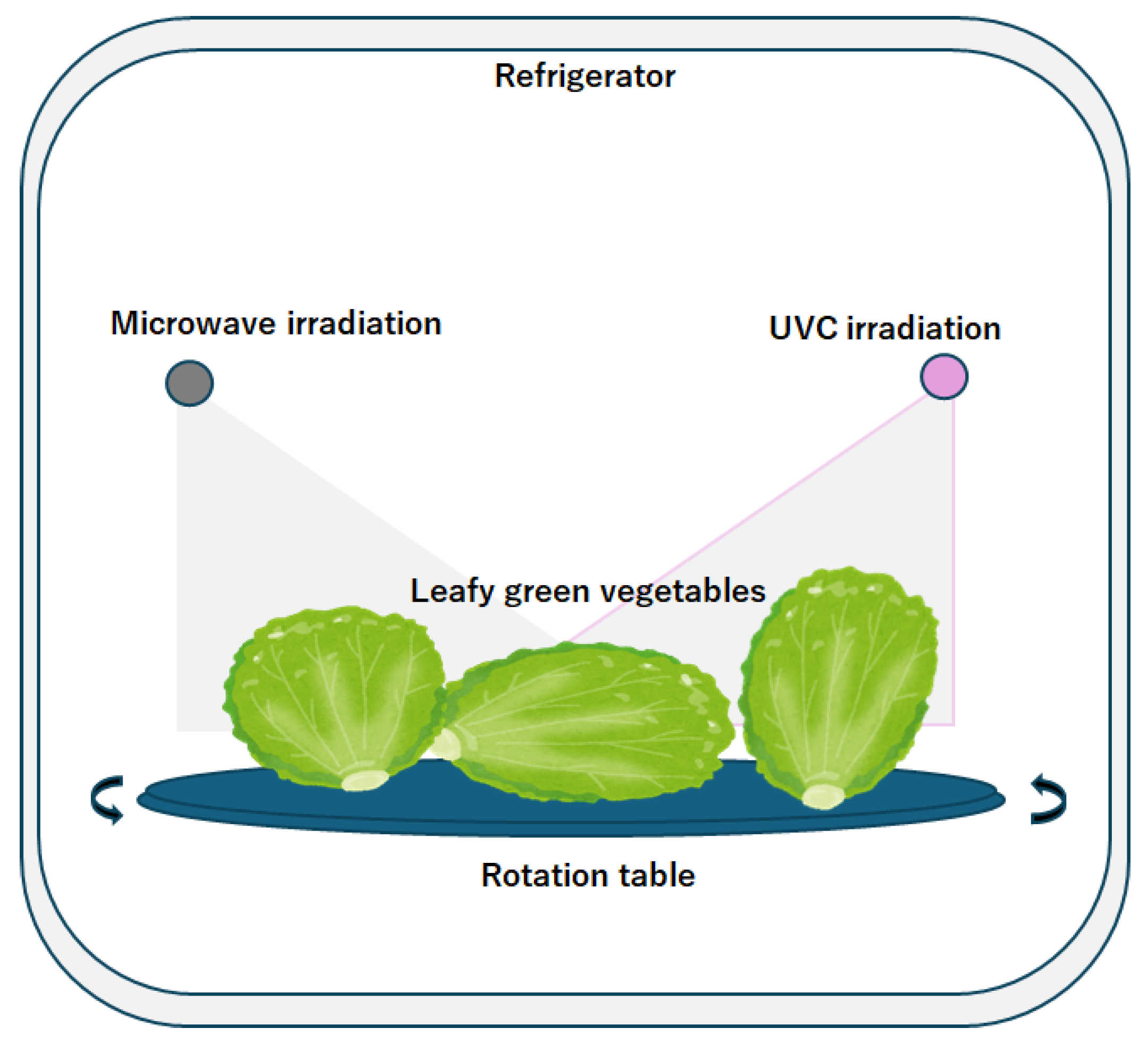

2. Ultraviolet Light Irradiation

3. Microwave Irradiation

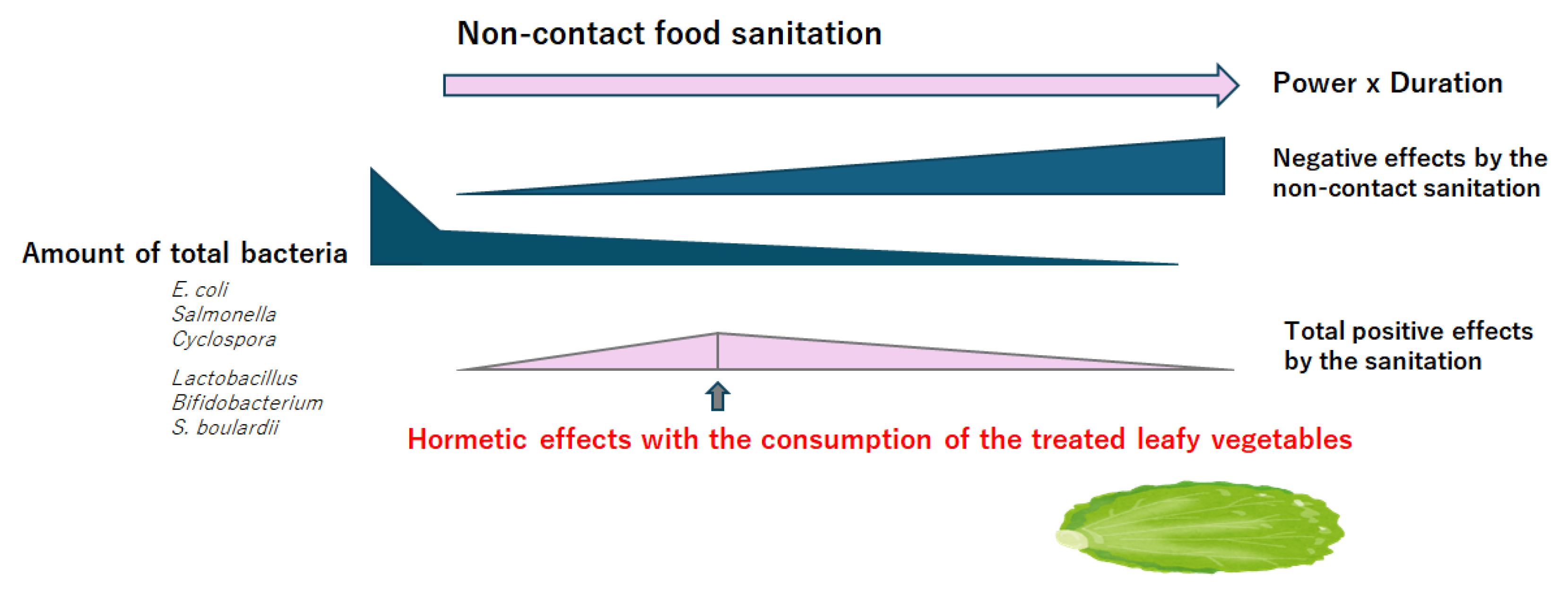

4. Hormesis Concept with a Positive Gut Microbiota

5. Hormesis Beneficial for Human Health

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFU | colony-forming units |

| LED | light-emitting diode |

| QOL | quality of life |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| UV | ultraviolet |

| UVA | ultraviolet-A |

| UVB | ultraviolet-B |

| UVC | ultraviolet-C |

References

- Cardinale, M.; Grube, M.; Erlacher, A.; Quehenberger, J.; Berg, G. Bacterial networks and co-occurrence relationships in the lettuce root microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 239–252. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.R.; Moyne, A.L.; Harris, L.J.; Marco, M.L. Season, irrigation, leaf age, and Escherichia coli inoculation influence the bacterial diversity in the lettuce phyllosphere. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e68642. [CrossRef]

- Machado-Moreira, B.; Richards, K.; Brennan, F.; Abram, F.; Burgess, C.M. Microbial contamination of fresh produce: what, where, and how? Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1727–1750. [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Tan, B.Z.; Dakwa, V.; D’Agnese, E.; Stanley, R.A.; Sassi, H.; Lai, Y.W.; Deaker, R.; Bowman, J.P. Effect of pre-harvest sanitizer treatments on Listeria survival, sensory quality and bacterial community dynamics on leafy green vegetables grown under commercial conditions. Food Res Int. 2023, 173, 113341. [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Holley, R.A. Factors influencing the microbial safety of fresh produce: a review. Food Microbiol. 2012, 32, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Paramithiotis, S.; Drosinos, E.H.; Skandamis, P.N. Microbial ecology of fruits and fruit-based products. In Sant’Ana ADS (ed), Quantitative microbiology in food processing: modeling the microbial ecology. 2016, 358–381.

- Rose, D.; Bianchini, A.; Martinez, B.; Flores, R. Methods for reducing microbial contamination of wheat flour and effects on functionality. Cereal Foods World. 2012, 57, 104. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.B.H.; Khodaparast, M.H. Efficacy of ozone to reduce microbial populations in date fruits. Food. Control. 2009, 20, 27–30. [CrossRef]

- Winter, H.; Wagner, R.; Ehlbeck, J.; Urich, T.; Schnabel, U. Deep Impact: Shifts of Native Cultivable Microbial Communities on Fresh Lettuce after Treatment with Plasma-Treated Water. Foods. 2024, 13, 282. [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, U.; Handorf, O.; Winter, H.; Weihe, T.; Weit, C.; Schäfer, J.; Stachowiak, J.; Boehm, D.; Below, H.; Bourke, P. The effect of plasma treated water unit processes on the food quality characteristics of fresh-cut endive. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 627483. [CrossRef]

- Ngolong, Ngea, G.L.; Qian, X.; Yang, Q.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Ianiri, G.; Ballester, A.R.; Zhang, X.; Castoria, R.; Zhang, H. Securing fruit production: Opportunities from the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of postharvest fungal infections. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 2508–2533. [CrossRef]

- Gombas, D.; Luo, Y.; Brennan, J.; Shergill, G.; Petran, R.; Walsh, R.; Hau, H.; Khurana, K.; Zomorodi, B.; Rosen, J.; Varley, R.l.; Deng, K. Guidelines to validate control of cross-contamination during washing of fresh-cut leafy vegetables. J Food Prot. 2017, 80, 312–330.

- Luo, Y.G.; Nou, X.W.; Millner, P.; Zhou, B.; Shen, C.L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.P.; Wang, Q.; Feng, H.; Shelton, D. A pilot plant scale evaluation of a new process aid for enhancing chlorine efficacy against pathogen survival and cross-contamination during produce wash. Int J Food Microbiol 2012, 158, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.R.; Ha, S.; Park, B.; Yang, J.S.; Dang, Y.M.; Ha, J.H. Effect of Ultraviolet-C Light-Emitting Diode Treatment on Disinfection of Norovirus in Processing Water for Reuse of Brine Water. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 885413. [CrossRef]

- Patz, S.; Witzel, K.; Scherwinski, A.C.; Ruppel, S. Culture Dependent and Independent Analysis of Potential Probiotic Bacterial Genera and Species Present in the Phyllosphere of Raw Eaten Produce. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3661. [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Selma, M.V.; Suslow, T.; Jacxsens, L.; Uyttendaele, M.; Allende, A. Pre- and postharvest preventive measures and intervention strategies to control microbial food safety hazards of fresh leafy vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 453–468. [CrossRef]

- Kerry, R.G.; Patra, J.K.; Gouda, S.; Park, Y.; Shin, H.S.; Das, G. Benefaction of probiotics for human health: A review. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 927–939. [CrossRef]

- Doron, S.; Snydman, D.R. Risk and safety of probiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, S129–S134. [CrossRef]

- Ayala D.I.; Cook, P.W.; Franco, J.G.; Bugarel, M.; Kottapalli, K.R.; Loneragan, G.H.; Brashears, M.M.; Nightingale, K.K. A systematic approach to identify and characterize the effectiveness and safety of novel probiotic strains to control foodborne pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1108. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Palmer, J.; Loo, T.; Shilton, A.; Petcu, M.; Newson, H.L.; Flint, S. Investigation of UV light treatment (254 nm) on the reduction of aflatoxin M1 in skim milk and degradation products after treatment. Food Chem. 2022, 390, 133165. [CrossRef]

- Chatterley, C.; Linden, K. Demonstration and evaluation of germicidal UV-LEDs for point-of-use water disinfection. J. Water Health. 2010, 8, 479–486. [CrossRef]

- Korovin, E.; Selishchev, D.; Besov, A.; Kozlov, D. UV-LED TiO2 photocatalytic oxidation of acetone vapor: effect of high frequency controlled periodic illumination. Appl Catal B. 2015, 163, 143–149. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. A.; MacAdam, J.; Autin, O.; Jefferson, B. Evaluating the impact of LED bulb development on the economic viability of ultraviolet technology for disinfection. Environ.Technol. 2014, 35, 400–406. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, M. Effects of ultraviolet-c treatment on growth and mycotoxin production by Alternaria strains isolated from tomato fruits. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 311, 108333. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.C. Mitigating fungal contamination of cereals: The efficacy of microplasma-based far-UVC lamps against Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium graminearum. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114550. [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, F.; Liu, H.; Neugart, S. Nutritional and physiological effects of postharvest UV radiation on vegetables: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9951–9972. [CrossRef]

- Akhila, P.P.; Sunooj, K.V.; Aaliya, B.; Navaf, M.; Sudheesh, C.; Sabu, S.; Sasidharan, A.; Mir, S.A.; George, J.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Application of electromagnetic radiations for decontamination of fungi and mycotoxins in food products: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 399–409. [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.M.; Chen, N.Z.; Ning, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.B.; Wei, L.M. Degradation of aflatoxin B1 in peanut oil by ultraviolet LED cold-light technology. China Oils Fats. 2019, 44, 83–88.

- Nicolau-Lapeña, I.; Rodríguez-Bencomo, J.J.; Colás-Medà, P.; Viñas, I.; Sanchis, V.; Alegre, I. Ultraviolet applications to control patulin produced by Penicillium expansum CMP-1 in apple products and study of further patulin degradation products formation and toxicity. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 804–823. [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.H.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, D.U.; Chun, H.S.; Ha, S.D. Effect of UV-C irradiation on inactivation of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus and quality parameters of roasted coffee bean (Coffea arabica L.) Food Addit. Contam. Part A. 2020, 37, 507–518.

- Martin, N.; Carey, N.; Murphy, S.; Kent, D.; Bang, J.; Stubbs, T.; Wiedmann, M.; Dando, R. Exposure of fluid milk to LED light negatively affects consumer perception and alters underlying sensory properties. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4309–4324. [CrossRef]

- Soro, A.B.; Shokri, S.; Nicolau-Lapeña, I.; Ekhlas, D.; Burgess, C.M.; Whyte, P.; Bolton, D.J.; Bourke, P.; Tiwari, B.K. Current challenges in the application of the UV-LED technology for food decontamination. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 131, 264–276. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, X.; Dong, X.; Dong, S.; Xiang, Q.; Bai, Y. Effects of UVC light-emitting diodes on microbial safety and quality attributes of raw tuna fillets. LWT. 2021, 139, 110553. [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Koubaa, M.; Bals, O.; Vorobiev, E. Recent insights in the impact of emerging technologies on lactic acid bacteria: A review. Food Res Int. 2020, 137, 109544. [CrossRef]

- Brugnini, G.; Rodríguez, S.; Rodríguez, J.; Rufo, C. Effect of UV-C irradiation and lactic acid application on the inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and lactic acid bacteria in vacuum-packaged beef. Foods. 2021, 10, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Pankaj, S.K.; Shi, H.; Keener, K.M. A review of novel physical and chemical decontamination technologies for aflatoxin in food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 71, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Luan, D. Study the synergism of microwave thermal and non-thermal effects on microbial inactivation and fatty acid quality of salmon fillet during pasteurization process. LWT. 2021, 152, 112280. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.R.; Wu, R.Z.; Rao, J.Y.; Yang, M.J.; Han, G.Q. Advances in the application of microwave and combined sterilization technology in foods. J. Microbiol. 2023, 43, 113–120.

- Cao, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Z.; Battino, M.; El-Seedi, H.; Guan, X. Mechanistic insights into the changes of enzyme activity in food processing under microwave irradiation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2465–2487. [CrossRef]

- Patil, H.; Shah, N.; Hajare, S.; Gautam, S.; Kumar, G. Combination of microwave and gamma irradiation for reduction of aflatoxin B1 and microbiological contamination in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) World Mycotoxin J. 2019, 12, 269–280.

- Lee, H.J.; Ryu, D. Worldwide Occurrence of Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Public Health Perspectives of Their Co-occurrence. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7034–7051. [CrossRef]

- Knox, O.G.G.; McHugh, M.J.; Fountaine, J.M.; Havis, N.D. Effects of microwaves on fungal pathogens of wheat seed. Crop Prot. 2013, 50, 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Popelářová, E.; Vlková, E.; Švejstil, R.; Kouřimská, L. The effect of microwave irradiation on the representation and growth of moulds in nuts and almonds. Foods. 2022, 11, 221. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.C.; Li, S.F. Multi-feed microwave heating temperature control system based on numerical simulation. IEEE J. Microw. 2019, 35, 92–96.

- Zheng, X.Z.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, C.H.; Shen, L.Y.; Zhao, X.L.; Xue, L.L. Research progress in the microwave technologies for food stuffs and agricultural products. TCSAE. 2024, 40, 14–28.

- Geedipalli, S.S.R.; Rakesh, V.; Datta, A.K. Modeling the heating uniformity contributed by a rotating turntable in microwave ovens. J. Food Eng. 2007, 82, 359–368. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Jiang, H. Effect of salt and sucrose content on dielectric properties and microwave freeze drying behavior of re-structured potato slices. J. Food Eng. 2011, 106, 290–297. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Chen, J.; Lv, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X. Domestic cooking methods affect the phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of purple-fleshed potatoes. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1264–1270. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.P.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S. Vacuum frying of carrot chips. Dry. Technol. 2005, 23, 645–656. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.A.; Bano, K.S.; Vyas, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Singh, P.; Mehdi, M.M. The dynamic crosslinking between gut microbiota and inflammation during aging: reviewing the nutritional and hormetic approaches against dysbiosis and inflammaging. Biogerontology. 2024, 26, 1. [CrossRef]

- Tap, J.; Mondot, S.; Levenez, F.; Pelletier, E.; Caron, C.; Furet, J.P.; Ugarte, E.; Muñoz-Tamayo, R.; Paslier, D.L.; Nalin, R. Towards the human intestinal microbiota phylogenetic core. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2574–2584. [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Wolters, M.; Weyh, C.; Krüger, K.; Ticinesi, A. The effects of lifestyle and diet on gut microbiota composition, inflammation and muscle performance in our aging society. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2045. [CrossRef]

- du, Toit, L.; Sundqvist, M.L.; Redondo-Rio, A.; Brookes, Z.; Casas-Agustench, P.; Hickson, M.; Benavente, A.; Montagut, G.; Weitzberg, E.; Gabaldón, T.; Lundberg, J.O.; Bescos, R. The Effect of Dietary Nitrate on the Oral Microbiome and Salivary Biomarkers in Individuals with High Blood Pressure. J Nutr. 2024, 154, 2696-2706.

- Dogra, S.K.; Doré, J.; Damak, S. Gut Microbiota Resilience: Definition, Link to Health and Strategies for Intervention. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 572921. [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P. Dietary factors, hormesis and health. Ageing Res. Rev. 2008, 7, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; Verbeke, K.; Reid, G. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Doar, N.W.; Samuthiram, S.D. Qualitative Analysis of the Efficacy of Probiotic Strains in the Prevention of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea. Cureus. 2023, 15, e40261. [CrossRef]

- Rangel, L.I.; Leveau, J.H.J. Applied microbiology of the phyllosphere. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 211. [CrossRef]

- Pogreba-Brown, K.; Austhof, E.; Armstrong, A.; Schaefer, K.; Villa, Zapata, L.; McClelland, D.J.; Batz, M.B.; Kuecken, M.; Riddle, M.; Porter, C.K.; Bazaco, MC. Chronic Gastrointestinal and Joint-Related Sequelae Associated with Common Foodborne Illnesses: A Scoping Review. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2020, 17, 67-86. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Giron, M.J.; Kim, J.N.; Schott, E.; Tahmin, C.; Ishoey, T.; Mincer, T.J.; DeWalt, J.; Toledo, G. The edible plant microbiome represents a diverse genetic reservoir with functional potential in the human host. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.O.; Leveau, J.H.J.; Marco, M.L. Abundance, diversity and plant-specific adaptations of plant-associated lactic acid bacteria. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2020, 12, 16–29. [CrossRef]

- Vitali, B.; Minervini, G.; Rizzello, C.G.; Spisni, E.; Maccaferri, S.; Brigidi, P.; Gobbetti, M.; Di, Cagno, R. Novel probiotic candidates for humans isolated from raw fruits and vegetables. Food Microbiol. 2012, 31, 116–125. [CrossRef]

- Bombaywala, S.; Purohit, H.J.; Dafale, N.A. Mobility of antibiotic resistance and its co-occurrence with metal resistance in pathogens under oxidative stress. J Environ Manage. Nov. 2021, 297, 113315. [CrossRef]

- Guerbette, T.; Boudry, G.; Lan, A. Mitochondrial function in intestinal epithelium homeostasis and modulation in diet-induced obesity. Mol. Metab. 2022, 63, 101546. [CrossRef]

- Zam, W. Gut microbiota as a prospective therapeutic target for curcumin: A review of mutual influence. J. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 2018, 1367984. [CrossRef]

- Tauffenberger, A.; Fiumelli, H.; Almustafa, S.; Magistretti, P.J. Lactate and pyruvate promote oxidative stress resistance through hormetic ROS signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 653. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Dhawan, G.; Kapoor, R.; Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, V. Hormesis: Wound healing and fibroblasts. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 184, 106449. [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Beneficial Effects of Red Wine Polyphenols on Human Health: Comprehensive Review. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023, 45, 782-798. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.A.; Bano, K.S.; Vyas, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Singh, P.; Mehdi, M.M. The dynamic crosslinking between gut microbiota and inflammation during aging: reviewing the nutritional and hormetic approaches against dysbiosis and inflammaging. Biogerontology. 2024, 26, 1. [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, W.A.; Reisenhofer-Graber, T.; Erschen, S.; Kusstatscher, P.; Berg, C.; Krause, R.; Cernava, T.; Berg, G. Phyllosphere-associated microbiota in built environment: do they have the potential to antagonize human pathogens? J Adv Res. 2023, 43, 109–121. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, F.; Zhao, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xie, J. Kaempferol Alleviates Murine Experimental Colitis by Restoring Gut Microbiota and Inhibiting the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB Axis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679897. [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, A.; Ziemichód, W.; Herbet, M.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. The Role of Diet as a Modulator of the Inflammatory Process in the Neurological Diseases. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 1436. [CrossRef]

- Westfall, S.; Caracci, F.; Estill, M.; Frolinger, T.; Shen, L.; Pasinetti, G.M. Chronic Stress-Induced Depression and Anxiety Priming Modulated by Gut-Brain-Axis Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 670500. [CrossRef]

- Bambury, A.; Sandhu, K.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Finding the needle in the haystack: Systematic identification of psychobiotics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 4430–4438. [CrossRef]

- Mörkl, S.; Butler, M.I.; Holl, A.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Probiotics and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Focus on Psychiatry. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Asemi, Z.; Daneshvar, Kakhaki, R.; Bahmani, F.; Kouchaki, E.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Hamidi, G.A.; Salami, M. Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Cognitive Function and Metabolic Status in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind and Controlled Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 256. [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Thanos, P.K.; Wang, G.J.; Febo, M.; Demetrovics, Z.; Modestino, E.J.; Braverman, E.R.; Baron, D.; Badgaiyan, R.D.; Gold, M.S. The Food and Drug Addiction Epidemic: Targeting Dopamine Homeostasis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 23, 6050–6061.

- Calabrese, E.J.; Pressman, P.; Hayes, A.W.; Dhawan, G.; Kapoor, R.; Agathokleous, E.; Baldwin, L.A.; Calabrese, V. The chemoprotective hormetic effects of rosmarinic acid. Open Med (Wars). 2024, 19, 20241065. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.W.; Kruger, C.L. (Eds.). Hayes' Principles and Methods of Toxicology (6th ed.). CRC Press. 2014, 89–140.

- Calabrese, E.J.; Kozumbo, W.J. The hormetic dose-response mechanism: Nrf2 activation. Pharm Res. 2021, 167, 105526. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J. Hormesis: Why it is important to toxicology and toxicologists. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008, 27, 1451–1474. [CrossRef]

- Scuto, M.; Modafferi, S.; Rampulla, F.; Zimbone, V.; Tomasello, M.; Spano', S.; Ontario, M.L.; Palmeri, A.; Trovato, Salinaro, A.; Siracusa, R.; Di, Paola, R.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Calabrese, E.J.; Wenzel, U.; Calabrese, V. Redox modulation of stress resilience by Crocus sativus L. for potential neuroprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory applications in brain disorders: From molecular basis to therapy. Mech Ageing Dev. 2022, 205, 111686.

- Scuto, M.; Rampulla, F.; Reali, G.M.; Spanò, S.M.; Trovato, Salinaro, A.; Calabrese, V. Hormetic Nutrition and Redox Regulation in Gut-Brain Axis Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024, 13, 484. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Yu, B.; Sun, X. Recent Advances in Non-Contact Food Decontamination Technologies for Removing Mycotoxins and Fungal Contaminants. Foods. 2024, 13, 2244. [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, E.; Khoshtaghaza, M.H.; Banakar, A.; Ebadi, M.T.; Hamidi-Esfahani, Z. Continuous decontamination of cumin seed by non-contact induction heating technology: Assessment of microbial load and quality changes. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e25504. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Nguyen, T.L.; Roh, H.; Kim, A.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kang, Y.R.; Kang, H.; Sohn, M.Y.; Park, C.I.; Kim, D.H. Mechanisms underlying probiotic effects on neurotransmission and stress resilience in fish via transcriptomic profiling. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 141, 109063. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Jung, S.; Hwang, G.S.; Shin, D.M. Gut microbiota indole-3-propionic acid mediates neuroprotective effect of probiotic consumption in healthy elderly: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial and in vitro study. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1025–1033. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).