Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Gesture Recognition Techniques

3.1. Wearable IMU- Machine Learning on the Cloud

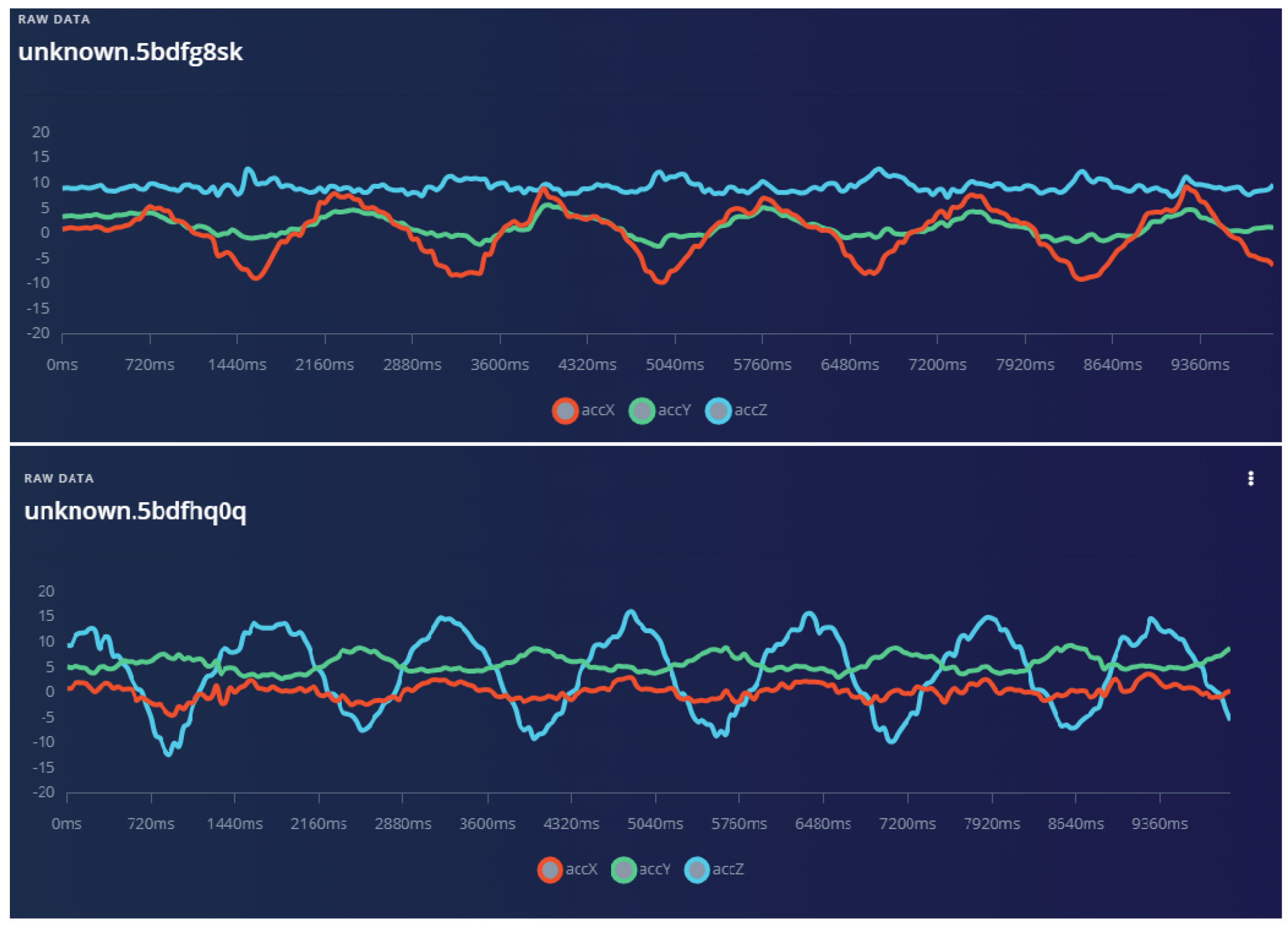

3.1.1. Training Data Collection

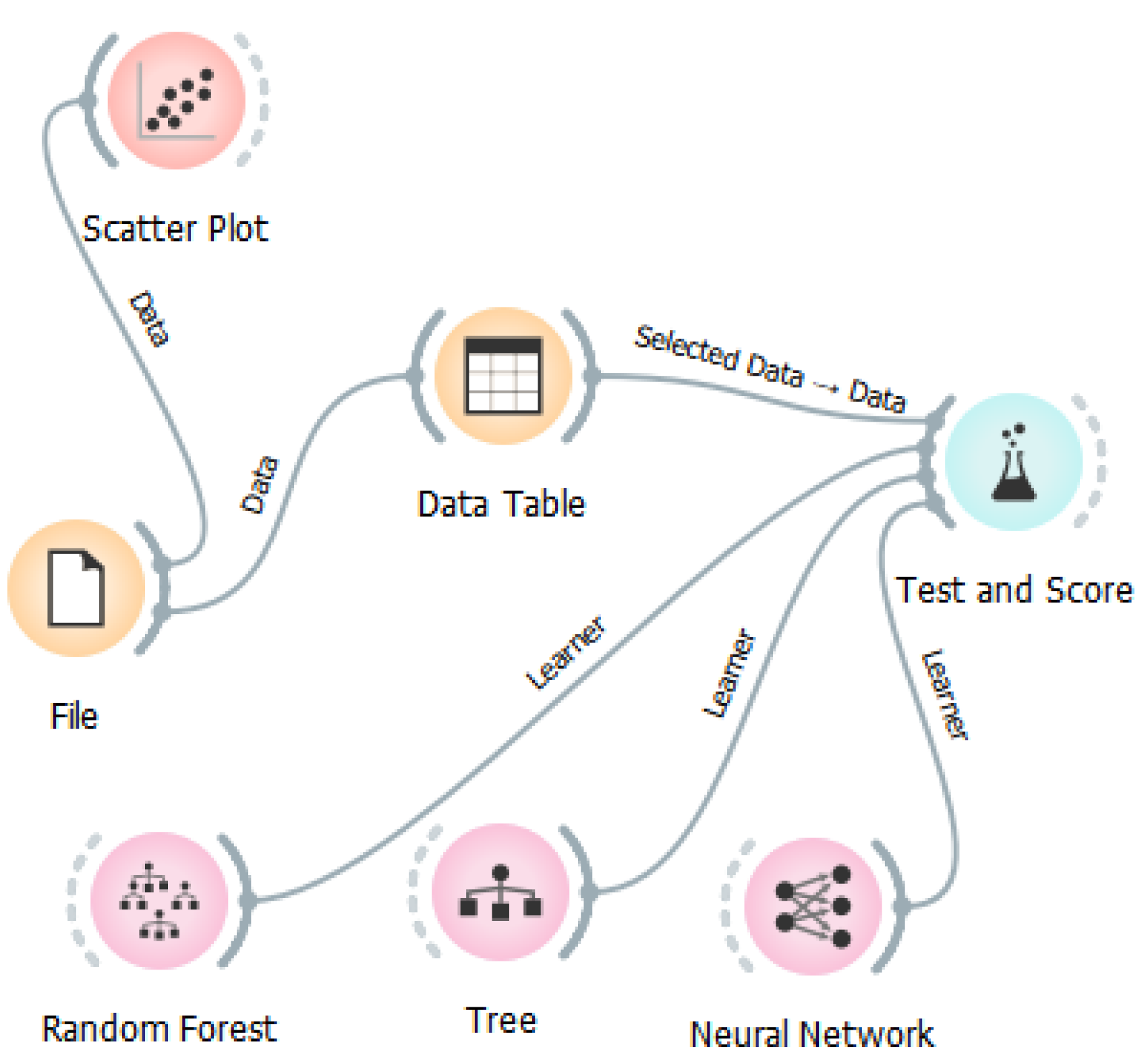

3.1.2. Training Process

3.2. Wearable IMU- Machine Learning on Device

3.2.1. Training Data Collection

3.2.2. Data Preprocessing, Feature Extraction, and Training

3.2.3. Machine Learning Model Creation and Accuracy Evaluation

3.2.4. Machine Learning on Device

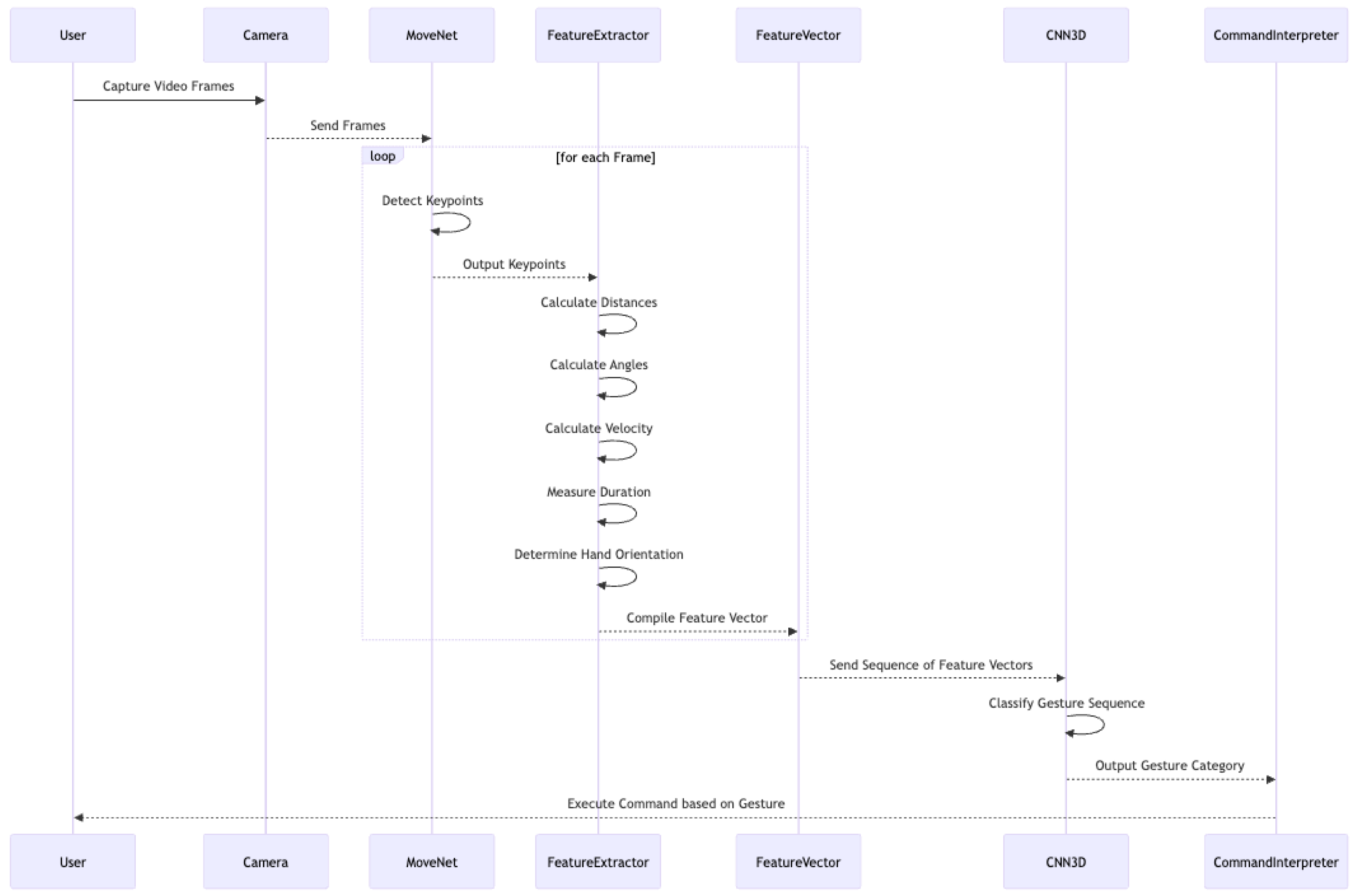

3.3. Vision Based

- Efficiency: By using keypoints instead of raw images, the computational load on the CNN is significantly reduced, enabling faster processing times.

- Robustness: Keypoint-based representations are less sensitive to variations in lighting and background conditions, leading to more consistent gesture recognition performance.

- Real-Time Performance: MoveNet’s ability to run at over 30 frames per second ensures that the system can provide immediate feedback, which is crucial for interactive applications.

3.3.1. Feature Extraction

-

Distance Between Keypoints: Calculating the Euclidean distances between keypoints (e.g., between hands or from hands to shoulders) helps identifying specific gestures based on the spatial relationships of body parts. First, Euclidean distances are calculated between specific pairs of keypoints, such as between the hands or from hands to shoulders, helping to identify gestures based on the spatial relationship of body parts.For three-dimensional space, if the keypoints are represented as and , the formula extends to:

-

Angle Between Joints: The angles formed at joints (e.g., elbow and shoulder angles) are indicative of certain gestures, such as waving or pointing Joint angles are calculated by examining specific body joints, such as at the fingers or arm and shoulder, which can help recognize gestures that involve particular arm movements, like waving or pointing.To calculate the angle at a joint formed by three keypoints , , and , we used the cosine rule. The lengths of the sides formed by these points are given by:- Length - Length - LengthUsing the cosine rule:Thus,

-

Velocity of Movement: Tracking the speed at which keypoints move differentiate between slow gestures (like a gentle wave) and fast movements (like a quick swipe), enhancing gesture recognition accuracy. The velocity of each keypoint is then assessed by tracking positional changes across consecutive frames, allowing for differentiation between slow and rapid gestures, such as a gentle wave versus a fast swipe.The velocity of a keypoint can be calculated by tracking its position over time. If the position of a keypoint at time is , then the velocity between two consecutive frames can be expressed as:where , , and is the time interval between frames.

-

Gesture Duration: The time taken to perform a gesture as a distinguished feature. For instance, holding a hand in a specific position for an extended period might indicate a different command than a quick motion. Gesture duration is also measured by tracking the consistency of a gesture over a sequence of frames, distinguishing longer, held gestures from quicker motions.Gesture duration is measured by counting the number of frames in which a gesture is consistently detected. If a gesture is detected in frames from to :

-

Hand Orientation: The orientation of the hand, e.g., palm facing up or down The orientation of each hand is determined based on the relative positions of keypoints on the wrist, hand, and fingers, which helps recognize gestures with specific hand orientations, such as a palm facing upward or downward. For example, if we have keypoints for the wrist , index finger tip , and middle finger tip , we can calculate the orientation vector as:The angle of orientation relative to a reference axis (e.g., horizontal axis along x-axis) can be calculated using:

3.3.2. Deep Learning Approach

- Input Layer: The input layer receives pre-processed images of hand gestures. These images are resized to a consistent dimension (224 × 224 pixels) to ensure uniformity across the dataset.

- Convolutional Layers: The initial layers consist of convolutional filters that extract low-level features such as edges and textures from the input images. This is followed by activation functions (ReLU) to introduce non-linearity into the model.

- Fire Modules: SqueezeNet employs fire modules that consist of a squeeze layer (1x1 convolutions) followed by an expand layer (1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolutions). This structure allows the network to learn the set of features while keeping the model size small.

- Pooling Layers: Max pooling layers are interspersed throughout the network to downsample feature maps, reducing dimensionality and computational load while retaining important spatial information.

- Dropout Layers: To prevent overfitting during training, dropout layers are added and randomly set a fraction of input units to zero at each update during training time.

- Fully Connected Layers: After the convolutional and pooling layers, the output is flattened and passed through one fully connected layer that perform high-level reasoning about the features extracted by the previous layers.

- Output Layer: The final layer uses a softmax activation function to classify the gestures into predefined categories (e.g., "lights on," "lights off," "find mobile," "activate locks").

3.3.3. Training Pipeline

3.3.4. Inference Pipeline

| Gesture | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lights On | 96.5% | 97.0% | 95.8% | 96.4% |

| Lights Off | 95.2% | 95.6% | 94.7% | 95.1% |

| Find Mobile | 94.8% | 95.3% | 93.9% | 94.6% |

| Activate Locks | 97.0% | 97.5% | 96.5% | 96.9% |

4. Discussion and Future Work Challenges

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Muneeb, M.; Rustam, H.; Jalal, A. Automate appliances via gestures recognition for elderly living assistance. 2023 4th International Conference on Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICACS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Stephan, J.J.; Khudayer, S. Gesture Recognition for Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). Int. J. Adv. Comp. Techn. 2010, 2, 30–35.

- Nooruddin, N.; Dembani, R.; Maitlo, N. HGR: Hand-gesture-recognition based text input method for AR/VR wearable devices. 2020 IEEE international conference on systems, man, and cybernetics (SMC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 744–751.

- Spournias, A.; Faliagka, E.; Skandamis, T.; Antonopoulos, C.; Voros, N.S.; Keramidas, G. Gestures detection and device control in AAL environments using machine learning and BLEs. 2023 12th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Faliagka, E.; Skarmintzos, V.; Panagiotou, C.; Syrimpeis, V.; Antonopoulos, C.P.; Voros, N. Leveraging Edge Computing ML Model Implementation and IoT Paradigm towards Reliable Postoperative Rehabilitation Monitoring. Electronics 2023, 12, 3375. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, S.; Zhu, C.; Balle, M.; Zhang, B.; Ran, L. Hand gesture recognition for smart devices by classifying deterministic Doppler signals. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2020, 69, 365–377. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Hasan, O. Wearable technologies for hand joints monitoring for rehabilitation: A survey. Microelectronics Journal 2019, 88, 173–183. [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.D.; Nguyen, L.T. Recognizing postures in Vietnamese sign language with MEMS accelerometers. IEEE sensors journal 2007, 7, 707–712. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Thang, N.D.; Kim, T.S. 3-D hand motion tracking and gesture recognition using a data glove. 2009 IEEE international symposium on industrial electronics. IEEE, 2009, pp. 1013–1018.

- Kim, S.Y.; Han, H.G.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, S.; Kim, T.W. A hand gesture recognition sensor using reflected impulses. IEEE Sensors Journal 2017, 17, 2975–2976. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Castelo, J.J.; Capobianco-Uriarte, M.d.L.M.; Piedra-Fernandez, J.A.; Ayala, R. A Survey on Intelligent Gesture Recognition Techniques. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 87135–87156. [CrossRef]

- Oudah, M.; Al-Naji, A.; Chahl, J. Hand gesture recognition based on computer vision: a review of techniques. journal of Imaging 2020, 6, 73. [CrossRef]

- Köpüklü, O.; Gunduz, A.; Kose, N.; Rigoll, G. Real-time hand gesture detection and classification using convolutional neural networks. 2019 14th IEEE international conference on automatic face & gesture recognition (FG 2019). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–8.

- Neethu, P.; Suguna, R.; Sathish, D. An efficient method for human hand gesture detection and recognition using deep learning convolutional neural networks. Soft Computing 2020, 24, 15239–15248. [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.Y.; Chung, Y.L.; Tsai, W.F. An efficient hand gesture recognition system based on deep CNN. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT). IEEE, 2019, pp. 853–858.

- Sen, A.; Mishra, T.K.; Dash, R. A novel hand gesture detection and recognition system based on ensemble-based convolutional neural network. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 40043–40066. [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Chandrasegar, V.K.; Koh, J. Accuracy enhancement of hand gesture recognition using CNN. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 26496–26501. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jin, L.; Zhen, L.; Huang, J. Gesture recognition based on 3D accelerometer for cell phones interaction. APCCAS 2008-2008 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Circuits and Systems. IEEE, 2008, pp. 217–220.

- Erdaş, Ç.B.; Atasoy, I.; Açıcı, K.; Oğul, H. Integrating features for accelerometer-based activity recognition. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 98, 522–527. [CrossRef]

- Avola, D.; Cinque, L.; Fagioli, A.; Foresti, G.L.; Fragomeni, A.; Pannone, D. 3D hand pose and shape estimation from RGB images for keypoint-based hand gesture recognition. Pattern Recognition 2022, 129, 108762. [CrossRef]

- Votel, R.; Li, N. Next-Generation Pose Detection with MoveNet and TensorFlow.js. TensorFlow Blog 2021.

| Random Forest | Tree | Neural Network |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Trees:19 | Min Number of Instances in leaves:2 | Max number of iterations:200 |

| - | Do not split subsets smaller than:9 | Neurons in hidden layers:100 |

| - | Limit the maximal tree depth to:100 | Activation:Logistic |

| - | Stop when majority reaches:95% - |

| Random Forest | Tree | Neural Network | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 0,996 | 0,994 | 0,995 |

| F1 | 0,997 | 0,991 | 0,992 |

| Precision | 0,998 | 0,899 | 0,996 |

| Recall | 0,999 | 0,887 | 0,996 |

| 0 |

| Number of training cycles | 50 |

| Learning rate | 0.0005 |

| Validation set size | 20 |

| Sampling frequency | 62.5 (Hz) |

| Input layer | 33 features |

| First dense layer | 20 neurons |

| Second dense layer | 10 neurons |

| Gesture 1 | Gesture 2 | Gesture 3 | Gesture 4 | Overall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 99,8% | 99,7% | 96,5% | 94,9% | 97,73% | 97,64% |

| Classification | 100% | 100% | 97,5% | 98,9% | 99,1% | 98,92% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).