1. Introduction

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) is crucial for the functioning of the immune system and has significant implications for neurodegenerative disorders. These disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), are characterised by progressive neuronal damage and loss. HLA class II loci that encode proteins are essential for antigen presentation. They are expressed in microglial cells, which are involved in both phagocytising pathological protein deposits and producing proinflammatory factors that accelerate neuronal death. This dual role underscores the importance of HLA in neurodegeneration [

1]. The genetic overlap between neurodegenerative disorders suggests that HLA regions are common genetic risk factors for neurodegenerative disorders. This highlights the shared genetic aetiology and the role of HLA in these diseases [

2].

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s disease, characterised by a high prevalence of sporadic cases [

3,

4]. The risk of developing PD is higher in men than in women [

5]. The prevalence of PD rises with age, with a significant increase above the age of 60 years [

6]. The main motor clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease include bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor at rest. PD also has non-motor manifestations that may develop years before the classic motor symptoms. These include sleep disturbances, autonomic dysfunction (constipation and urgency to urinate during the day), hyposmia, or psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety [

7].

The aetiology of PD is multifactorial, involving environmental and genetic factors [

8]. PD is neuropathologically characterised by the loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in the

substantia nigra and the formation of intracellular Lewy body inclusions. However, neurodegeneration also affects cells in other regions of the neural network [

9]. Various molecular mechanisms are involved in the pathogenesis of PD, such as proteostasis disruption, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, calcium homeostasis dysregulation, and axonal transport alterations [

10,

11].

The association of specific HLA alleles with PD can vary significantly across different populations, highlighting the importance of considering ethnic and geographic diversity in genetic studies. Protective and risk HLA alleles show variations that are specific to different populations and not universally consistent [

12]. However, in the Baltic countries, including Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, there is a notable lack of studies examining the association between HLA alleles and PD. Studies in these countries have primarily focused on the broader epidemiological and clinical aspects of neurodegenerative diseases rather than detailed genetic associations. This lack of research means that there is limited information on HLA alleles conferring an increased risk or protection against PD in Baltic populations. This knowledge underscores the need for more comprehensive genetic studies in these regions to identify potential population-specific genetic markers for PD.

Our pilot study aimed to identify potential protective and risk alleles for PD in a Latvian cohort and to identify candidate alleles for future research. We provide a comprehensive characterisation of our cohort, including blood biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain (NfL), S100 calcium-binding protein A9 (S1000A9), kynurenic acid (KYNA), and glutamate decarboxylase (GAD1), which are widely discussed in the literature for their relevance to neurodegenerative diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

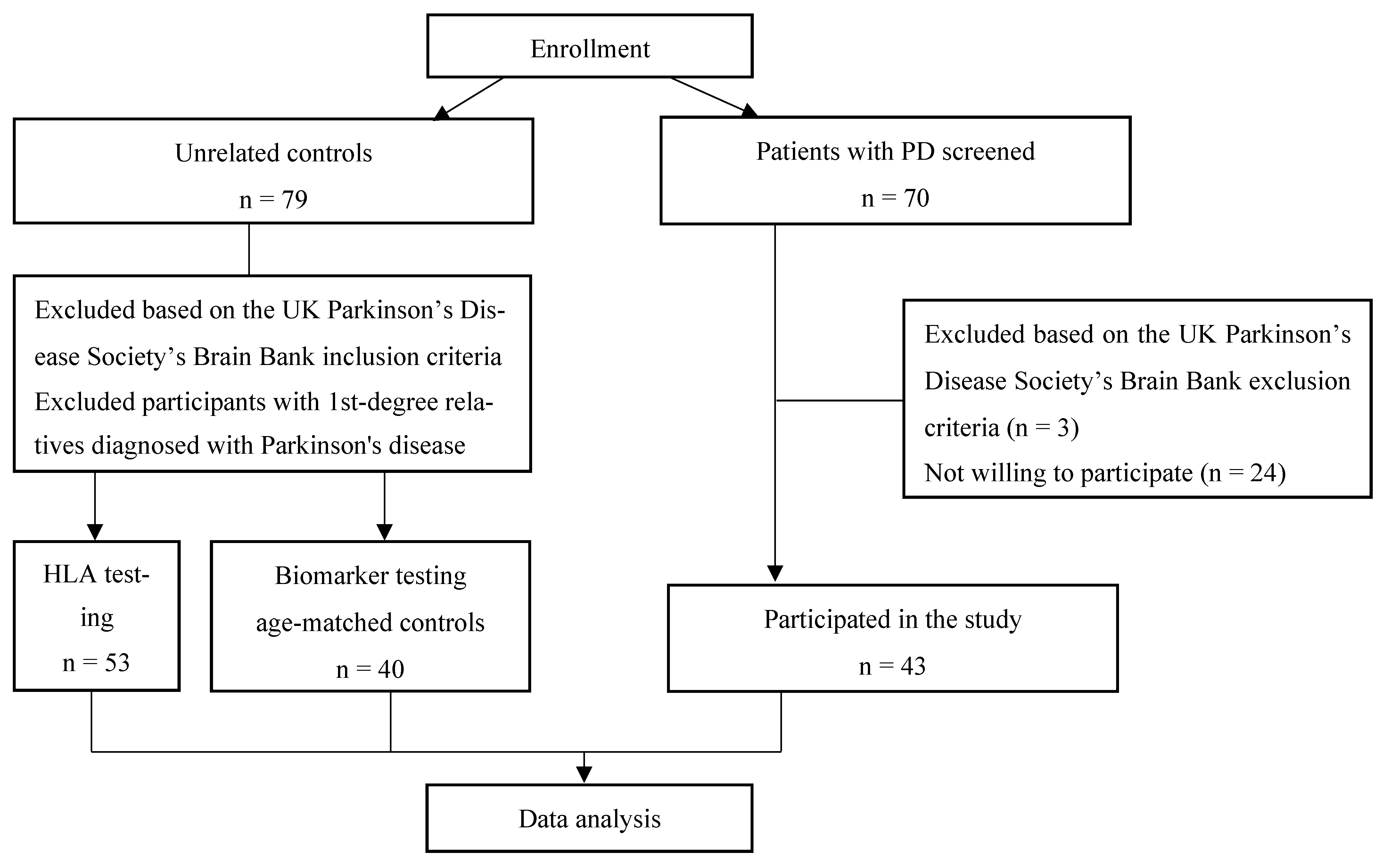

For this study, 43 PD patients and 79 unrelated controls were enrolled. All the participants were recruited from the Gaiļezers Clinic of Riga East University Hospital, Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, from 2019 to 2020 (

Figure 1). All the PD patients were diagnosed with PD according to the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria [

13] and recruited into the study at the time of diagnosis. The control group consisted of individuals without PD who presented to a neurologist for other disorders, and those with first-degree relatives diagnosed with PD were excluded.

Demographic variables, including sex, age, age at disease onset, disease duration, and clinical type, were recorded for all the PD participants. Age at onset was based on medical records and the patients’ recollections of their first symptoms. The worldwide prevalence rates of PD vary by age group [

14]. Therefore, for the evaluation of alleles, the PD patients were divided into two groups: 1) those with an onset age <60 years and 2) patients with an onset age ≥60 years. According to the classification of clinical phenotypes, the participants were divided into the tremor-dominant (TD), postural instability/gait difficulty (PIGD), and mixed phenotypes of PD [

15]. Professionally trained and qualified neurologists evaluated the patients.

The PD patients were evaluated using the Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) during the ON condition. Disease severity was evaluated using the Hoehn and Yahr scale (staging 1–5) [

16,

17].

The study protocol was approved by the Science Department of the Riga East University Hospital Clinic Gaiļezers and the Central Medical Ethics Committee of Latvia. All participants provided written informed consent. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (2008).

Peripheral blood samples were taken from the PD patients and unrelated controls. Two 5 mL blood samples were obtained from each participant. The samples were stored at +4 °C and delivered to the laboratory within 2 h.

To detect HLA class II alleles, 5 mL volumes of the peripheral blood samples were placed in tubes with anticoagulant EDTA, then frozen at −20 °C, and stored in the laboratory until testing. The analysis included human DNA extraction from blood and HLA gene typing with a low-resolution polymerase chain reaction. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from leukocytes using a QIAamp® DNA Blood Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, GE). The gene typing method included the detection of alleles of the HLA-DRB1, -DQA1, and -DQB1* genes, using specific primers according to the manufacturer's instructions (DNA-Technology, Moscow, RU). Amplification was performed using a programmed thermocycler (DTlite, DNA-Technology).

To detect biomarkers, 5 mL volumes of the peripheral blood samples were placed in tubes with the anticoagulant EDTA and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min; the supernatant was aspirated and aliquoted, frozen at −20 °C, and stored in the laboratory until testing.

NfL and KYNA levels were measured in the serum using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Abbexa Ltd., Cambridge, UK). The method of determination was based on sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology. The measuring range was 15.6 pg/mL–1000 pg/mL for NfL and 2.47 ng/mL to 200 ng/mL for KYNA.

The GAD1 and S1000A9 levels in the serum were measured with a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (chemiluminescence) (NOVUS Biologicals, LLC, Centennial, CO, USA). The method of determination was based on the sandwich-CLIA principle. The measuring range was 0.31 ng/mL–20 ng/mL for GAD1 and 0.16 ng/mL to 10 ng/mL for S100A9.

The data distribution was assessed by inspecting a normal Q-Q plot and using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Mean values and standard deviations are used to report normally distributed data, the medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are used to summarise non-normally distributed data, and frequencies and percentages are used to describe nominal data. Allele frequency was defined as the number of participants with homozygote or heterozygote allele presentations. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the frequency distribution between the PD and control groups. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the NfL, S100A9, and GAD1 levels, and the independent-samples t test was used to compare the kynurenic acid levels between the PD and control groups. Statistical significance was only accepted at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics 28.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and Jamovi Version 2.5.3.

3. Results

Of the 43 patients with sporadic PD, 23 (53.5%) were female and 20 (46.5%) were male. The mean age of the patients was 65 years (±8.9 SD), and the average disease duration was 6 years. The most common comorbidities were arterial hypertension and thyroid gland disorders (hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism), followed by cancer and diabetes mellitus. Among the patients with oncological diseases, none had brain cancer. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the PD group are presented in

Table 1.

We extensively analysed HLA polymorphism, including 12 HLA-DRB1 alleles, 7 HLA-DQA1 alleles, and 10 HLA-DQB1 alleles.

Of all 12 HLA-DRB1 alleles identified in the PD group, 7 occurred at a frequency ≥10%. The allele frequencies were as follows: HLA-DRB1*01—23.3%; -DRB1*04—37.2%; -DRB1*07—37.2%; -DRB1*11—20.9%; -DRB1*13—18.6%; -DRB1*15—23.3%; and -DRB1*17—16.3%. We found that the PD patients presented a statistically significant higher frequency of the HLA-DRB1*04 allele than controls (p < 0.001). In contrast, HLA-DRB1*01 was found at a lower frequency in the PD patients than in the controls (p = 0.032). The statistical analysis of HLA-DRB1*04 showed a wide confidence interval, which may affect the reliability of the results. Moreover, we excluded the HLA-DRB1*08 allele from further investigation because its confidence interval crossed 1.

Among the HLA-DQA1 alleles in the PD group, almost all were observed at a frequency greater than 10%. A statistically significant difference between groups was observed only for the HLA-DQA1*01:03 (p < 0.001), -DQA1*02:01 (p = 0.03), -DQA1*03:01 (p = 0.003), and -DQA1*05:01 alleles (p = 0.023). An analysis of the HLA-DQA1*01:03 allele revealed a vast confidence interval; therefore, we excluded it from further evaluation.

Of the ten HLA-DQB1 alleles identified, frequencies ≥ 10% were observed for HLA-DQB1*02:01:02, -DQB1*03:01, -DQB1*03:03, -DQB1*05:01, -DQB1*05:02:04, and -DQB1*06:02:08. There were no statistically significant differences between the PD and control groups (

p > 0.05). We excluded the HLA-DQB1*03:04 allele because its confidence interval crossed 1. The frequencies of the HLA class II alleles are summarised in

Table 2.

Alleles with statistically significant differences between the PD group and controls were further investigated. We analysed the frequency of allele polymorphism according to age at disease onset. All the PD patients were divided into two subgroups (age < 60 and age ≥ 60). The HLA-DQA1*02:01 allele was statistically significantly more frequent in the PD group with disease onset at 60 years or older (

p = 0.033). An analysis of the other alleles did not show statistically significant differences in the PD subgroups < 60 years old and 60 years or older (

p > 0.05). The frequencies of HLA-DRB1*01,*04 and HLA-DQA1*02:01, *03:01, and *05:01 allele polymorphism in the PD subgroups are shown in

Table 3.

We assessed the levels of blood biomarkers in all patients in the PD group and in 40 age-matched participants in the control group; both groups were also similar in terms of gender distribution. NfL levels were higher in the PD group, but the difference was not statistically significant (

p > 0.05). GAD1 levels were similar in the PD patients and their age-matched controls. The KYNA levels in the PD group were statistically significantly lower than those in the controls (

p = 0.005). Furthermore, S100A9 levels were statistically significantly higher in the PD patients than in the controls (

p = 0.005). The levels of the blood biomarkers analysed in the PD patients and age-matched controls are shown in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

Our pilot study aimed to identify alleles that could potentially serve as protective or risk factors for PD in a Latvian cohort and to pinpoint candidate alleles for further research. We provided a detailed characterisation of our cohort, including an analysis of biomarkers such as NfL, S100A9, kynurenic acid (KYNA), and GAD1, all of which are well documented in the literature for their importance in neurodegenerative diseases.

The HLA loci are the most polymorphic in the human genome. The association of HLA polymorphism with PD was first reported more than ten years ago [

18]. Previous studies have found an association between the HLA-DRB1, -DQA1, and -DQB1 loci and PD [

19,

20], and polymorphisms at the HLA-DRB1 locus have most often been studied.

In the current study, we thoroughly analysed the HLA region and examined its association with PD in a Latvian cohort. We found that the PD patients in our cohort had a statistically significantly higher frequency of the HLA-DRB1*04 allele, suggesting that it is a potential risk factor for PD. Our results are in contrast to those of several studies where the HLA-DRB1*04 allele was shown to play a protective role [

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, some studies suggest that the HLA-DRB1*04 allele has a risk association [

20] and that different subtypes may have different positive or negative associations with PD [

12]. Moreover, HLA-DRB1*01 was statistically significantly less frequently detected in the PD patient group in the current study. Unlike several previous studies that either did not find an association between the HLA-DRB1*01 allele and PD [

22] or showed an association between the HLA-DRB1*01:01 allele subtype and an increased risk of PD [

25], our study observed a possible protective role for this allele. This discrepancy underscores the importance of considering ethnic and geographic diversity in genetic studies.

This study found statistically significant differences between the PD group and controls when evaluating allelic polymorphism at the HLA-DQA1 locus. Both HLA-DQA1*03:01 and HLA-DQA1*02:01 were statistically more prevalent in the PD group. In addition, HLA-DQA*02:01 was statistically significantly more frequently detected in the PD group with disease onset at 60 years or older. That emphasizes the involvement of the immune system in neurodegeneration. The association of the HLA DQA1*02:01 allele with PD has not been widely discussed in previous studies. The results of our research suggest that HLA-DQA1*02:01 is a risk allele and may have a specific association with late-onset PD, warranting further investigation. An association between the HLA DQA1*03:01 allele and PD was observed in previous studies; however, in contrast to the results of our research, negative associations were obtained in these studies [

23,

24]. At the same time, we found that the HLA-DQA1*05:01 allele was negatively associated with PD, and, thus, it may offer a protective effect against the disease in the Latvian cohort. The current study highlights the potential role of HLA-DQA1 alleles polymorphism in the pathogenesis of PD.

The role of S100A9 in the pathogenesis of PD has been extensively studied. Histologically, S100A9 has been found in the brain tissue of patients with PD in co-aggregation with α-synuclein [

26]. Regarding blood biomarkers, our study showed that S100 calcium-binding protein A9 levels were statistically significantly higher in the PD patients than in the controls, indicating its potential as a biomarker for PD. Elevated levels of S100A9 have been associated with neuroinflammation, and this increase has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases [

27]. This finding supports previous research suggesting the involvement of S100A9 in PD. Overall, our results highlight the potential of S100A9 as a blood biomarker and provides further evidence of its potential involvement in the inflammatory processes associated with PD.

The potential effects of the metabolites of the kynurenine pathway on neuroinflammation in PD are mainly based on the neurotoxic role of quinolinic acid and the neuroprotective role of kynurenic acid in the brain [

28]. In our study, the KYNA levels were statistically significantly lower in the PD group than in the controls. KYNA is a neuroactive metabolite of the kynurenine pathway, and it has been implicated in neuroprotection [

29,

30,

31]. The reduced kynurenic acid levels in the PD patients may reflect the dysregulation of this pathway and contribute to neurodegenerative processes. This observation aligns with that of other studies that reported alterations in the kynurenine pathway in PD [

32,

33].

GAD1 is an essential enzyme for the conversion of glutamate to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a key inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain [

34,

35]. GABA has also been identified as an important gastrointestinal neurotransmitter that is potentially involved in both secretory and motor gastrointestinal functions [

36]. Although research indicates that changes in the GABAergic system are involved in PD, our study did not find significant differences in GAD1 blood levels between the PD patients and controls, suggesting that it may not be a reliable biomarker for the disease. While this parameter alone may not be a definitive marker, its role within the broader GABAergic system warrants further investigation to elucidate its potential utility in diagnosing and monitoring PD.

NfL is a widely studied biomarker for PD and other neurological disorders. It is a blood biomarker indicating neuroaxonal damage. Previous research indicates that the blood levels of NfL are higher in PD patients than in controls [

37,

38]. We investigated the NfL levels in patients with PD and age-matched controls. However, although the NfL levels were higher in the PD group, they did not show a statistically significant difference. One potential reason for the lack of statistical significance is the sensitivity of the ELISA method used. Although widely used, an ELISA may not be as sensitive as other methods, such as a single-molecule array (Simoa) or electrochemiluminescence immunoassays. These alternative methods have been shown to detect NfL at lower concentrations and with higher accuracy [

39]. The ELISA method has a higher limit of detection than more sensitive assays such as Simoa, which can measure NfL levels at subpicogram per millilitre concentrations, providing more precise and reliable measurements [

40].

Our pilot study provides valuable insights into PD’s genetic and biomarker profiles in a Latvian cohort, identifies potential risk and protective HLA alleles for PD, and highlights the relevance of certain blood biomarkers. These findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on PD genetics and emphasise the importance of considering population-specific variations.

Despite this study’s inclusion of both genetic predisposition and potential blood biomarkers for disease, it has several limitations. First, the small number of participants restricted the statistical analysis, resulting in some ambiguous findings. Second, for some of the testing methods discussed in the results, we could not employ more precise techniques, which may have impacted the accuracy of the findings. More sensitive methods, such as Simoa, are recommended for determining the level of NfL in the blood. Further studies with a larger number of patients and more centers are needed to evaluate HLA alleles in the Latvian population.

However, the strengths of this study are that it estimates the prevalence of alleles among patients with PD and highlights potential risk and protective alleles. Additionally, it is the first study to examine the HLA II class alleles and blood biomarkers in PD patients in Latvia.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the relationship between HLA II class alleles, potential blood biomarkers, and PD. The findings demonstrate that the HLA-DRB1*01 and -DRB1*04 alleles and HLA-DQA1*02:01, -DQA1*03:01, and -DQA1*05:01 alleles are associated with PD. Furthermore, the study provides additional evidence that S100A9 and KYNA can be considered potential blood biomarkers for PD. Despite some limitations, the findings of this study improve our understanding of the genetic factors underlying PD in a Latvian cohort and offer new ideas for further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, software, and validation, V.Ķ., G.K., and O.M.; formal analysis, O.M. and M.Z.; investigation, O.M.; resources, O.M.; data curation, O.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.; writing—review and editing, V.Ķ., M.Z., and G.K.; visualisation, O.M.; supervision, V.Ķ., M.Z., and G.K.; project administration, O.M.; funding acquisition, O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU), Doctoral Study Grant, Grant number No. 12-8/1/2019; Grant number No. 2020/15/ZD-AK, Grant number No. 6-DN-20/1/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Science Department of the Riga East University Hospital Clinic Gaiļezers (protocol code ZD/08-07/-19/14, 28 June 2019) and the Latvian Central Medical Ethics Committee (protocol code 1/19-06-26, 26 June 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical restrictions, they are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge persons with Parkinson’s disease and volunteers who participated in this study. We want to thank the members of the laboratory of Rīga Stradiņš University who tested the samples used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aliseychik, M.P.; Andreeva, T.V.; Rogaev, E.I. Immunogenetic Factors of Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Role of HLA Class II. Biochemistry 2018, 83, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wightman, D.P.; Savage, J.E.; Tissink, E.; Romero, C.; Jansen, I.E.; Posthuma, D. The genetic overlap between Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2023, 127, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lau, L.M.; Breteler, M.M. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbaz, A.; Carcaillon, L.; Kab, S.; Moisan, F. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 172, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldereschi M, Di Carlo A, Rocca WA, Vanni P, Maggi S, Perissinotto E, et al. Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism in a longitudinal study: two-fold higher incidence in men. ILSA Working Group. Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neurology. 2000, 55(9), 1358-1363. [CrossRef]

- Pringsheim, T.; Jette, N.; Frolkis, A.; Steeves, T.D. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.K.; Tanner, C.M.; Brundin, P. Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, W.R.; Lees, A.J. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Xie, X.X.; Liu, R.T. The Role of α-Synuclein Oligomers in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, M.K.; Damotte, V.; Hollenbach, J.A. The immunogenetics of neurological disease. Immunology 2018, 153, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.J.; Daniel, S.E.; Kilford, L.; Lees, A.J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: A clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1992, 55, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Su, D.; Zhao, D.; Wang, A.; Feng, T. Temporal trends in the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease from 1980 to 2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, e464–e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebbins, G.T.; Goetz, C.G.; Burn, D.J.; Jankovic, J.; Khoo, T.K.; Tilley, B.C. How to identify tremor dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty groups with the movement disorder society unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale: Comparison with the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 668–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S.; Elton, R.L.; Members, U.P. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease; Fahn, S., Marsden, C.D., Calne, D., Goldstein, M., Eds.; Macmillan Health Care Information: Florham Park, NJ, USA, 1987; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Satake, W.; Ogawa, K.; Suzuki, K.; Hirata, J.; Foo, J.N.; Tan, E.K.; Toda, T.; Okada, Y. Trans-Ethnic Fine-Mapping of the Major Histocompatibility Complex Region Linked to Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Tamouza, R.; Delord, M.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Tzourio, C.; Mulot, C.; Nacfer, M.; Lambert, J.C.; Beaune, P.; Laurent-Puig, P.; et al. Association between Parkinson’s disease and the HLA-DRB1 locus. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi, S.; Chinniah, R.; Sevak, V.; Ravi, P.M.; Raju, M.; Vellaiappan, N.A.; Karuppiah, B. Association of HLA-DRB1, DQA1 and DQB1 alleles and haplotype in Parkinson’s disease from South India. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 765, 136296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guen, Y.; Luo, G.; Ambati, A.; Damotte, V.; Jansen, I.; Yu, E.; Nicolas, A.; de Rojas, I.; Peixoto Leal, T.; Miyashita, A.; et al. Multiancestry analysis of the HLA locus in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases uncovers a shared adaptive immune response mediated by. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2302720120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wei, L.; Luo, F.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, F.; Kang, P.; Xu, R.; Xiao, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. HLA-DRB1 alleles are associated with the susceptibility to sporadic Parkinson’s disease in Chinese Han population. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissemann, W.T.; Hill-Burns, E.M.; Zabetian, C.P.; Factor, S.A.; Patsopoulos, N.; Hoglund, B.; Holcomb, C.; Donahue, R.J.; Thomson, G.; Erlich, H.; et al. Association of Parkinson disease with structural and regulatory variants in the HLA region. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 93, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.; Ambati, A.; Andersen, M.S.; Krohn, L.; Estiar, M.A.; Saini, P.; Senkevich, K.; Sosero, Y.L.; Sreelatha, A.A.K.; Ruskey, J.A.; et al. Fine mapping of the HLA locus in Parkinson’s disease in Europeans. NPJ Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenbach, J.A.; Norman, P.J.; Creary, L.E.; Damotte, V.; Montero-Martin, G.; Caillier, S.; Anderson, K.M.; Misra, M.K.; Nemat-Gorgani, N.; Osoegawa, K.; et al. A specific amino acid motif of. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7419–7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Iashchishyn, I.A.; Moskalenko, R.A.; Wang, C.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Wallin, C.; Gräslund, A.; Kovacs, G.G.; Morozova-Roche, L.A. Co-aggregation of pro-inflammatory S100A9 with α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: Ex vivo and in vitro studies. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Song, R.; Wang, Z.; Jing, Z.; Ma, J. S100A8/A9 in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, D.; Iyer, M.; Narayanasamy, A.; Siva, K.; Vellingiri, B. Kynurenine pathway in Parkinson’s disease—An update. eNeurologicalSci 2020, 21, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Vakili, K.; Yaghoobpoor, S.; Tavasol, A.; Jazi, K.; Hajibeygi, R.; Shool, S.; Sodeifian, F.; Klegeris, A.; McElhinney, A.; et al. Dynamic changes in metabolites of the kynurenine pathway in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease: A systematic Review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, P.L.; Wang, E.W.; Lewis, M.M.; Krzyzanowski, S.; Capan, C.D.; Burmeister, A.R.; Du, G.; Escobar Galvis, M.L.; Brundin, P.; Huang, X.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolites Are Associated With Symptoms and Nigral Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, A.; Urbanska, E.M. Kynurenic acid in neurodegenerative disorders-unique neuroprotection or double-edged sword? CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2022, 28, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H.; Cheng, M.L.; Tang, H.Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Wu, Y.R.; Chen, C.M. Alternations of Metabolic Profile and Kynurenine Metabolism in the Plasma of Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 6319–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmans, P.; Moskvina, V.; Jones, L.; Sharma, M.; Vedernikov, A.; Buchel, F.; Saad, M.; Bras, J.M.; Bettella, F.; Nicolaou, N.; et al. A pathway-based analysis provides additional support for an immune-related genetic susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murueta-Goyena, A.; Andikoetxea, A.; Gómez-Esteban, J.C.; Gabilondo, I. Contribution of the GABAergic System to Non-Motor Manifestations in Premotor and Early Stages of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terkelsen, M.H.; Hvingelby, V.S.; Pavese, N. Molecular Imaging of the GABAergic System in Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonisms. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 22, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auteri, M.; Zizzo, M.G.; Serio, R. GABA and GABA receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: From motility to inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 93, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.; Lee, B.C.; Lin, C.H. Integrated Plasma and Neuroimaging Biomarkers Associated with Motor and Cognition Severity in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenhauer, B.; Dakna, M.; Kruse, N.; Galasko, D.; Foroud, T.; Zetterberg, H.; Schade, S.; Gera, R.G.; Wang, W.; Gao, F.; et al. Validation of Serum Neurofilament Light Chain as a Biomarker of Parkinson’s Disease Progression. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1999–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhle, J.; Barro, C.; Andreasson, U.; Derfuss, T.; Lindberg, R.; Sandelius, Å.; Liman, V.; Norgren, N.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H. Comparison of three analytical platforms for quantification of the neurofilament light chain in blood samples: ELISA, electrochemiluminescence immunoassay and Simoa. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016, 54, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dewit, N.; Jacobs, D.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; In ‘t Veld, S.G.J.G.; Coppens, S.; Quaglia, M.; Hirtz, C.; Teunissen, C.E.; Vanmechelen, E. A Novel Neurofilament Light Chain ELISA Validated in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, Frontotemporal Dementia, and Subjective Cognitive Decline, and the Evaluation of Candidate Proteins for Immunoassay Calibration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).