Introduction

Cancer is a complex, multifactorial disease characterized by intricate and profound cellular transformations at the molecular level, often triggered by genetic mutations and other biochemical alterations. These molecular changes lead to a state of uncontrolled cellular growth, proliferation, and division, a defining feature of neoplastic growth, which can cause a rapid accumulation of tissue mass [

1,

2]. Under typical conditions, senescent or damaged cells receive intercellular signals to undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis), allowing for replacement with healthy cells. However, cancer cells are able to evade apoptosis through different mechanisms such as upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins like the Bcl-2 family members, immune escape, and deficiencies in mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis pathways [

3]. As a result, cancer cells exhibit a much longer lifespan and uncontrolled proliferation, diverting essential nutrients and resources from non-tumoral cells.

The development of effective cancer therapeutics remains one of the most significant challenges in modern medicine, with researchers continuously seeking novel approaches to target cancer cells while minimizing damage to healthy tissues. Traditional chemotherapeutic agents, while effective in many cases, often lead to severe side effects due to their inability to discriminate between rapidly dividing normal cells and cancer cells [

4]. This has driven the search for more selective therapeutic approaches that exploit the unique characteristics of cancer cells, including their altered metabolism, specific surface markers, and dysregulated signaling pathways [

4,

5].

Recent advances in molecular biology and drug discovery have led to the emergence of targeted therapies that show promising results in various cancer types. These include small molecule inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and innovative drug delivery systems that can specifically target cancer cells [

6].

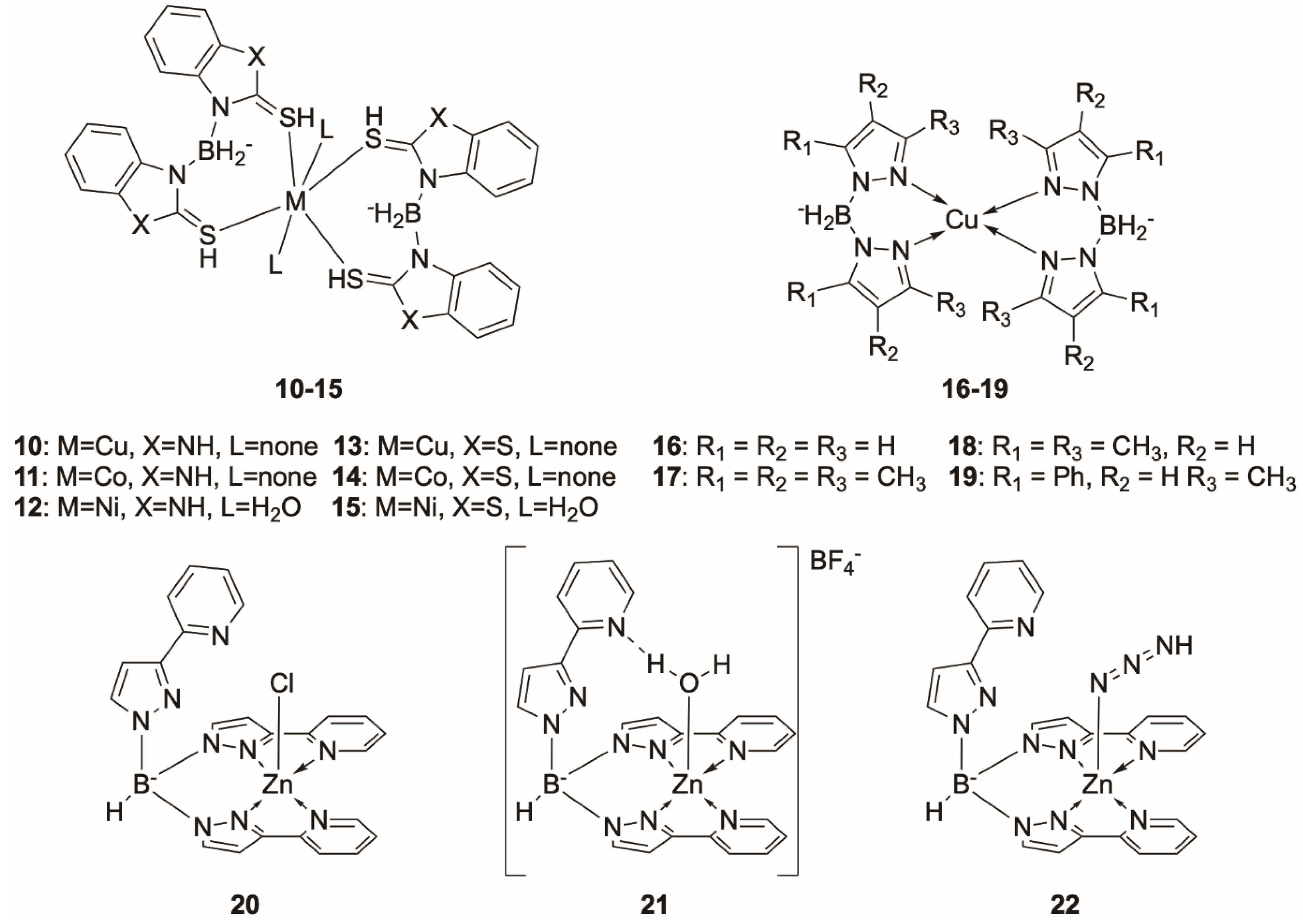

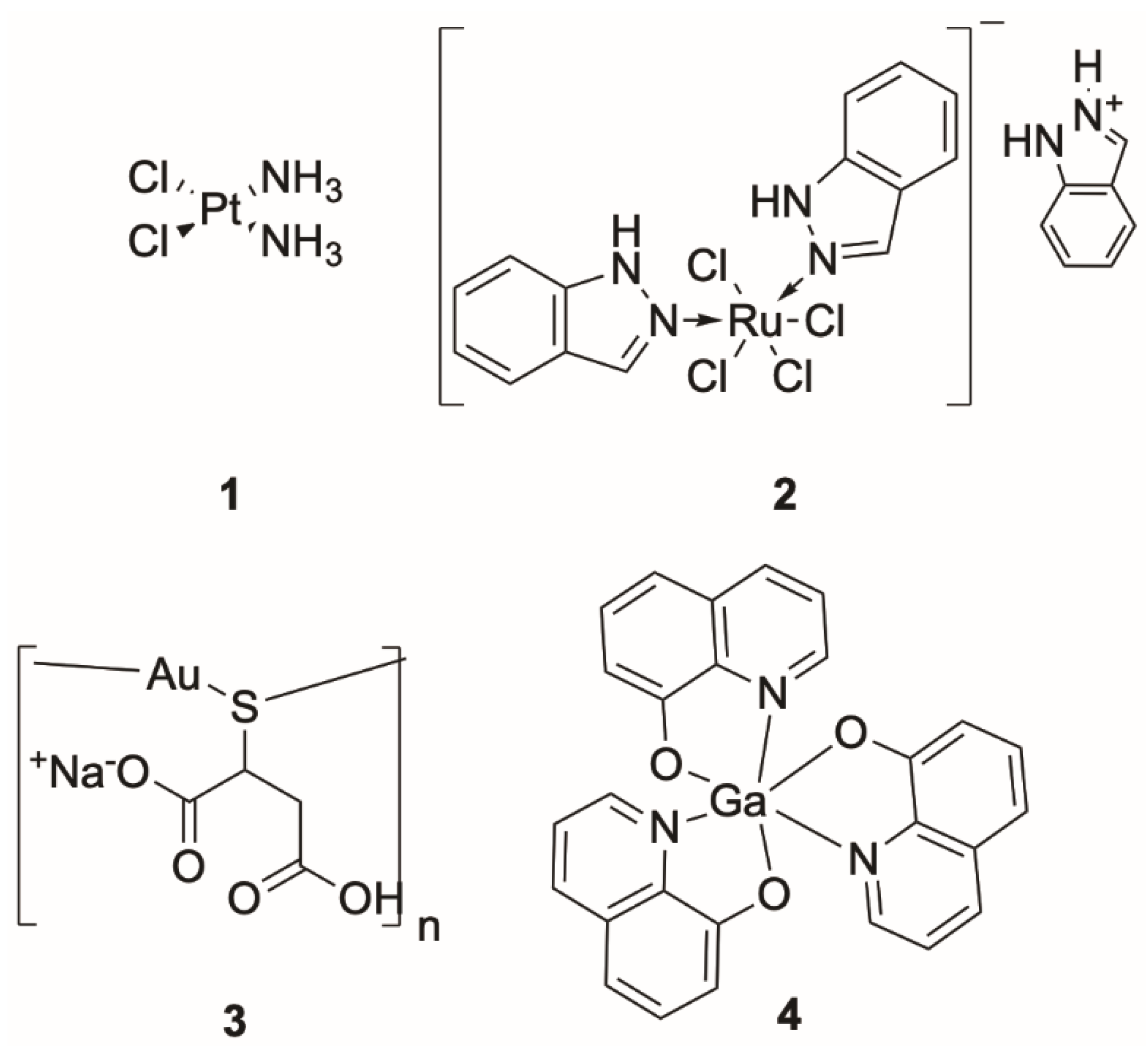

Coordination complexes such as cisplatin (

1,

cis-diamminodichloroplatinum(II)), KP1019 (

2, indazole

trans-[tetrachlorobisruthenate(III)]), aurothiomalate (

3), KP46 (

4, tris-(8-quinolinolato)gallium(III)), and many others have been already successfully used to treat different forms of cancer [

7] (

Figure 1). The successful history of cisplatin, discovered in 1966 to be a potent trans-domain cell division inhibitor and used either alone or a co-adjuvant almost as a go-to anti-cancer drug, has recently led to an intensive exploration of novel prototypical cancer drugs [

8].

Within the domain of metal complexes, some coordination compounds with the tri-dentate scorpionate ligand were found to exhibit an interesting anticancer activity [

9,

10]. The chemistry of these compounds has been studied since 1966, allowing the generation of a considerable number of scorpionate-shaped ligands and their complexation to different metal atoms [

11]. The straightforward synthesis of diverse compounds within the scorpionate family, combined with preliminary findings indicating notable anticancer potential, positions the scorpionate scaffold as a compelling focus in medicinal chemistry.

In the last years substantial progress has been made in investigating the anticancer potential of various scorpionate complexes, revealing their significant cytotoxic effects across different cancer cell lines. Herein, we discuss and underscore the promise of scorpionate-metal complexes as versatile, selective, and effective alternatives to conventional chemotherapeutic agents, suggesting their potential to form the basis of next-generation anticancer therapies.

The anticancer potential of metal complexes has been recognized since the discovery of cisplatin, a milestone that inspired extensive research into metal-based therapeutics [

12].

Essential metals such as zinc, copper, and iron play pivotal roles in numerous biological processes within the human body [

13]. A key feature of their antiproliferative properties is the capacity to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) via Fenton chemistry. Cancer cells, characterized by accelerated metabolism, accumulate ROS more rapidly than normal cells, leading to cellular stress and, ultimately, cell death as homeostasis is disrupted [

13,

14,

15]. This ROS-mediated cytotoxicity is a central mechanism in the activity of metal complexes against cancer. Similarly, scorpionate complexes have also demonstrated anticancer properties, offering promising coordination chemistry platforms for therapeutic exploration [

16,

17,

18].

Scorpionate Chemistry

Scorpionate ligands have been known for more than five decades since Trofimenko has synthesized and reported this new type of tridentate ligands in 1967 [

19]. The peculiar name the ligands got is due to the similarity between their metal-coordinating geometry and the way in which scorpions attack their prey with pincers and sting. The first synthesized family of scorpionates were the anionic hydrotris(pyrazol-1-yl)borates (Tp,

5,

Figure 2). Afterwards, different scorpionates with substituted pyrazol rings and boron atom were synthesized leading to different steric and electronic effects [

20].

Moreover, the pyrazolyl rings can be replaced with any other azolyl heterocycles that may contain nitrogen, oxygen or sulfur atoms [

21]. The replacement of one of the heterocycles with any other coordinating or non-coordinating group is possible as well, leading to the so-called heteroscorpionates (

Figure 3), that comprise the combination of different azolyl rings or its replacement by other coordinating or non-coordinating functions (e.g. hydride, alkyl or aryl, acetate, etc.), as opposed to homoscorpionates, where donor atoms come from equivalent moieties.

The central atom of the scorpionate ligands also can be changed, resulting in the several congeners (

Figure 3): tris(pyrazol-1-yl)methanes (Tpm,

6), tris(pyrazol-1-yl)phosphanes (TpP,

7) tris(pyrazol-1-yl)amines (

8) and tris(pyrazol-1-yl)silanes (TpS,

9) [

21,

22,

23,

24]. This large variety of different substituents, heterocycles, and central atoms that can be used makes scorpionates a very diverse family of ligands with different properties and activities.

All these different scorpionate ligands were reported to form different coordination compounds from alkaline to transition metals [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Moreover, tris(pyrazol-1-yl)borates were shown to complex with lanthanides and actinides [

33,

34,

35]. These coordination compounds have a widespread use starting from the applications as a catalyst for polymerization, oxidation and nitrene transfer reactions to bioorganic and medicinal chemistry for modeling enzymes, antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activity [

20,

32,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. In comparison to the great advances made on the use of scorpionates as catalysts, their activity, as anticancer agents, is still rather unexplored and far from systematized. This fact, along with the wide diversity of the scorpionates, their properties, as well as a severe need for new potent compounds with anticancer activity, makes the exploration of scorpionates potential biological activity against cancer a very promising and interesting research theme.

Poly(pyrazol-1-yl)borate Complexes

Full sandwich bis-scorpionate complexes with Cu(II), Ni(II), and Co(II) ions and 2-mercaptobenzimidazole and 2-mercaptobenzothiazole heterocycles, replacing the conventional pyrazole ligands (

10-15,

Figure 3) [

41] have been produced as these heterocycles have an established biological activity [

42,

43], but also due to sulfur’s role as a soft donor atom, which enhances coordination stability with transition metals such as copper, potentially augmenting the complexes' robustness and bioactivity.

Figure 3.

Structure of scorpionate complexes with poly(pyrazol-1-yl)borate ligands. Adapted from [

18,

41,

44].

Figure 3.

Structure of scorpionate complexes with poly(pyrazol-1-yl)borate ligands. Adapted from [

18,

41,

44].

The anticancer activity of complexes

10-

15 was assessed against colon (SW116), lung (A 549) and breast carcinoma (MCF-7) cancer cell lines, with the results compared to the established chemotherapy drug, cisplatin. Notably, the complexes exhibited the highest activity against colon cancer cells. Among these, only the copper-based scorpionates demonstrated a cytotoxicity superior to the one cisplatin had. Specifically,

10 exhibited the most potent activity, with IC

50 values of 0.65 μM, 11.44 μM, and 1.18 μM against the SW116, A549, and MCF-7 cell lines, respectively, while cisplatin exhibited IC

50 values of 8.62 μM, 33.52 μM, and 61.56 μM for the same cell lines. Moreover, complexes containing 2-mercapto-benzimidazole displayed significantly higher anticancer activity compared to those with 2-mercapto-benzothiazole. A further analysis of the mechanism of cell death revealed that the anti-proliferative/cytotoxic effect associated with compound

10 is partly mediated through apoptosis induction in cancer cells [

41].

To further evaluate the scorpionates activity, DNA interaction and genotoxicity assays by comet and mobility shift assays along with molecular docking studies were carried out. Both the comet and mobility shift assays demonstrated that the copper scorpionate 10 interacted with DNA in a manner similar to cisplatin, indicating potential DNA intercalation capabilities, predominantly at the minor groove of the DNA, involving the formation of hydrogen bonds, as suggested by molecular docking.

Recently, another investigation into the anticancer properties of copper-based full sandwich bis(pyrazolyl)borate complexes was conducted [

44]. In this study, four different copper(II) complexes (

16-

19,

Figure 3) were synthesized using pyrazolyl, 3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl, 3,4,5-trimethylpyrazol-1-yl, and 3-methyl-5-phenylpyrazol-1yl ligands.

The cytotoxic effects of these complexes were evaluated against the breast carcinoma MCF-7 cell line and compared to cisplatin. Complexes bearing more substituted and bulkier ligand exhibited reduced activity compared to the unsubstituted ones; the unsubstituted full sandwich copper(II) bis(pyrazolyl)borate complex

16 exhibited the highest activity with an IC

50 value of 25.37 μM, whereas the least active was the copper(II) bis(3,4,5-trimethylpyrazolyl)borate complex

18, with an IC

50 value almost twice higher, at 44.21 μM. Nevertheless, all the complexes demonstrated higher activity than cisplatin, with complex

16 exhibiting an activity nearly four times higher than that of cisplatin [

44]. A structure-activity approach revealed the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and dipole moment displayed a direct correlation with IC

50 value. Among these parameters, the dipole moment was the most significant, as a decrease in dipole moment increases the lipophilicity of these compounds, influencing their biological properties and anticancer activity. Molecular docking simulations also suggests that complex

17 interacts with cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2, binding energy of -7.21 kcal/mol) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, binding energy of -6.62 kcal/mol), with − 7.65 and –6.62 kcal/mol for the controls (the co-crystalized inhibitors) [

44].

Beyond copper, zinc-scorpionate complexes (

20-

22, Figure 3) bearing tris-(2-pyridyl)-(pyrazol-1-yl)borate ligands have also been found to display IC

50 values roughly half of those of cisplatin against triple-negative breast cancer lines MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, HCC1937, and Hs578T [

18].

Although zinc does not exhibit redox activity like the previous transition metals, it is still an essential element in various cellular pathways, including signaling, maintaining homeostasis, and modulating cytotoxicity [

45,

46]. These factors can ultimately influence the overall activity of these complexes.

The binding efficacy of zinc complexes with calf thymus DNA was evaluated, showing that one complex molecule binds 3 to 4 base pairs, with complex 20 demonstrating the lowest binding energy, likely due to the replacement of a chlorine group by a hydroxyl group upon cellular entry. Molecular docking studies revealed that complex 20 exhibited the lowest binding free energy, at –10.3 kcal/mol, indicating strong intercalation with DNA. Additionally, interactions with bovine serum albumin (BSA) were analyzed, revealing increased absorption intensity and significant decreases in fluorescence intensity, suggesting static quenching and confirming the complexes' interactions with BSA.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is characterized by the absence of three key receptors on cancer cells: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), making TNBC more difficult to treat. Also, TNBC is more aggressive than other types of breast cancer, tending to proliferate quickly, and being more likely to metastasize. These challenges underscore the need for novel therapeutic strategies.

Despite their redox inactivity, zinc-scorpionate complexes, being able to bind DNA and proteins, could represent a promising class of therapeutic agents for targeting cancer, particularly in challenging contexts such as triple-negative breast cancer. Their ability to interact with biological macromolecules may enhance their cytotoxic effects, providing a potential alternative to traditional chemotherapeutics.

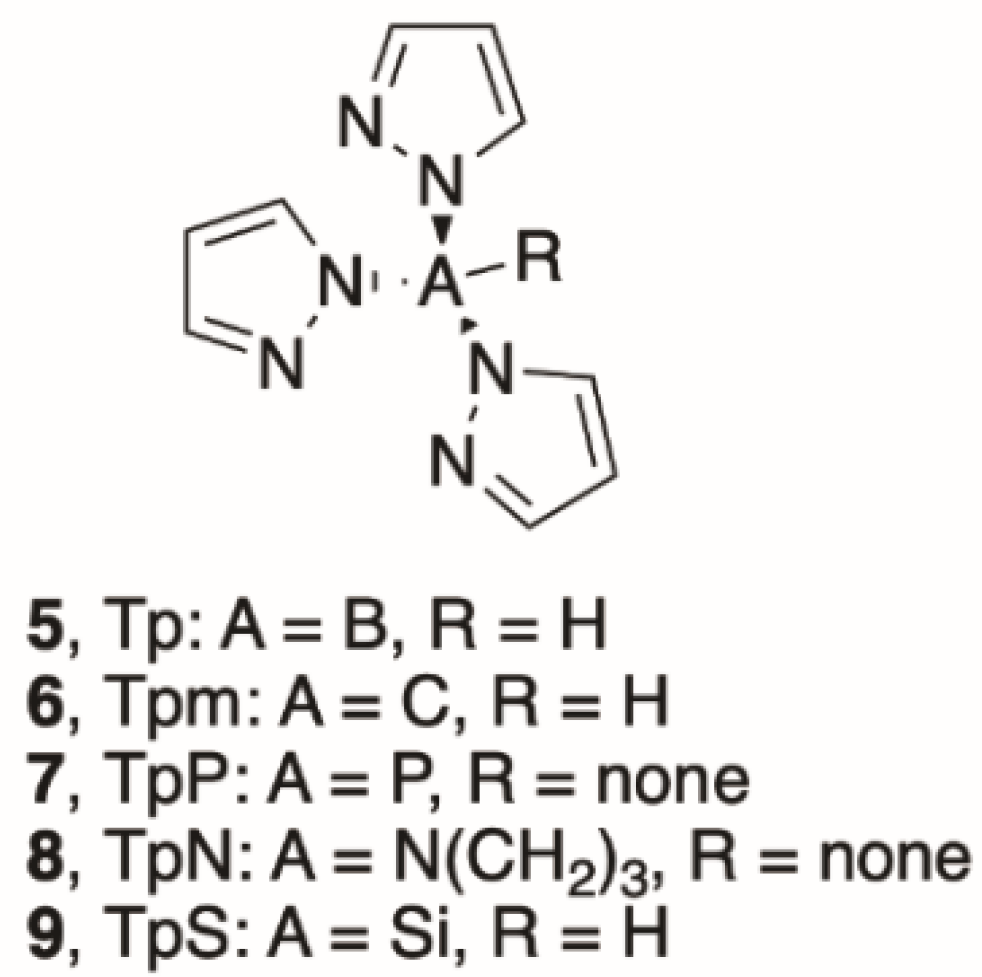

Poly(pyrazol-1-yl)methane Complexes

The ability of scorpionate-like copper(II) complexes with functionalized bis(pyrazol-1-yl)methane ligands was probed by Morelli et al. [

47], who replaced the central boron or carbon atom of the tris(pyrazol-1-yl) ligands by a carbon atom of a known antagonist of the

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (

23-

26,

Figure 4).

Certain breast cancer cell lines express the NMDAR1 and NMDAR2 receptors, which play a critical role in breast cancer progression [

51]. Aligned with this, the authors aimed to explore the potential therapeutic efficacy of combining the mechanisms of a noncompetitive NMDA antagonist with those of a copper scorpionate against a panel of human prostate (PC3), breast cancer (MCF7 and SKBR3), non-small cell lung cancer (H460), bladder cancer (T24), and renal cancer (Caki2) cell lines.

While the precursors bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetate and bis(3,5-dimethyl-pyrazol-1-yl)acetate exhibited no significant activity on their own, their conjugates with an NMDA antagonist (23-24), demonstrated enhanced activity within the micromolar range. The study revealed differences in efficacy among the conjugated derivatives. The bis-pyrazol-1-yl conjugate 23 showed lower cytotoxicity than the standalone NMDA antagonist, while the second derivative, 24, not only matched but, in some assays, surpassed the antagonist’s activity—particularly against T24 and Caki2 cell lines. Among the copper scorpionates, complex 25, which contains unsubstituted pyrazolyl rings, demonstrated moderate efficacy across various cell types. In contrast, complex 26 exhibited a significantly higher cytotoxic effect, outperforming both previous ligands and other complexes. These findings suggest that unsubstituted pyrazolyl rings may reduce anticancer activity in these complexes.

Furthermore, the mechanism of action of complex

26 against the MCF7 cell line was found to involve an increase of ROS production and induction of oxidative stress, which translated into an increase of the mitochondrial membrane potential. A Western blot analysis revealed upregulated expression of the immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein, indicating the induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. These cellular changes are characteristic of paraptosis [

52], suggesting that complex

26 may induce paraptotic cell death pathways. This is particularly relevant as breast cancer cells often exhibit resistance to apoptosis, and the ability of complex

26 to induce paraptosis highlights its potential as a novel therapeutic agent.

Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetate complexes with silver(I) (

27-

29,

Figure 4) have also been probed for their potential use as agents towards anticancer treatment [

48], using both 2D and 3D cell culture models of human colon (HCT-15), pancreatic (PSN-1), cervical (A431), breast (MDA-MB-231), ovarian (2008), cisplatin-resistant ovarian adenocarcinoma (C13), and small cell lung cancer (U1285) solid tumour cancer cell lines.

All three silver complexes demonstrated significant cytotoxic in 2D cultures in the low micromolar range, outperforming cisplatin. The U1285 and cisplatin-resistant C13 cell lines were particularly susceptible, with the silver complexes showing up to 14-fold greater potency than cisplatin in some cases. Notably, complex 28, with a 3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl ring exhibited superior activity compared to the unsubstituted pyrazolyl complex 27, although even the latter outperformed cisplatin against HCT-15, MDA-MB-231, U1285, and C13 cell lines. In the U1285 3D culture model, the three complexes have IC50 values of 63.8, 27.9 and 22.0 µM, respectively (vs. 65 µM for cisplatin). This highlights the promising potential of silver(I) scorpionate complexes as anticancer agents, especially in drug-resistant cancer cells.

Cellular uptake studies also showed that 28 and 29, the more active complexes, accumulated in higher quantities in the cell. As no significant difference at either the activity of uptake levels were found between 28 and 29, that feature, respectively, the 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane (PTA) and the triphenylphosphine (PPh3) ligands, suggests that the primary factor contributing to the uptake and efficacy of the complexes is the lipophilicity of the bidentate bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetate ligand.

Given that cancer cells often exhibit high levels of thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) to manage oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment [

53], these complexes were evaluated for their ability to inhibit TrxR activity both in cell-free systems and in U1285 cells. While in the cell-free assay these complexes displayed an activity lower than that of the reference TrxR inhibitor auranofin, in intact U1285 cells complexes

28 and

29 displayed an inhibitory activity similar to that of auranofin. The three complexes also led to increased cellular hydrogen peroxide.

In addition to inhibiting TrxR, the silver complexes 27-29 were found to be able to modulate total thiol content. In particular, the reduction of cellular sulfhydryl content obtained with 29 at the higher concentration tested (3 µM) was very similar to that induced by equimolar of auranofin. These three complexes also determined a substantial time-dependent and dose-dependent increase in cellular basal hydrogen peroxide production, which was, however, less pronounced than that elicited by antimycin, a classic inhibitor of the mitochondrial respiratory.

The impact of ROS on mitochondria was evaluated through mitochondrial membrane potential analysis, revealing that treatment with the silver complexes caused mitochondrial hypopolarization, with up to 30% hypopolarization in cells treated with complex 28. Consistent with previous trends, 28 and 29, bearing the 3,5-dimethylpyrazole moiety, exhibited higher activity. Transmission electron microscopy further confirmed the anti-mitochondrial effects, showing significant mitochondrial swelling, reinforcing the evidence of the ability of these complexes to induce mitochondrial disruption.

Tris-substituted (pyrazol-1-yl)methanes and its congeners have also been studied for their biological activity [

49]. Dichlorotris(pyrazol-1-yl)methane iron(II) (

30) and bis(2,2,2-tris(pyrazol-1-yl)ethanol)cobalt(II) (

31) (

Figure 4) were analyzed for cytotoxicity, motogenicity, and effect on the metabolome on model B16 (mouse epithelial skin melanoma) and HCT116 cancer cell lines, as well as on the non-tumoral cell line HaCaT (human immortalized keratinocyte cell line).

While complex 30, [FeCl2(Tpm)], did not exhibit any activity against HCT116 and HaCaT cancer cell lines, it promoted the B16 cell line viability increased with its presence. On the other hand, complex 31, [Co(TpmOH)2](NO3)2, exhibited low cytotoxic effects against the B16, HCT116 and HaCaT cell lines with IC50 values 88, 500 and 380 μM, respectively. The ability of the compounds to stimulate or suppress cell migration was studied through scratch assays. Unlike cytotoxicity, both complexes exhibited anti-mitogenic effects at non-toxic concentrations. The iron(II) complex was able to decrease the ability of HCT116 and HaCaT cell lines to migrate, but enhanced the migration rate of B16 cells, while the cobalt(II) complex 31 inhibited the cell migration ability for all tested cell lines. This anti-motogenic ability of 31 indicates a potential antimetastatic activity.

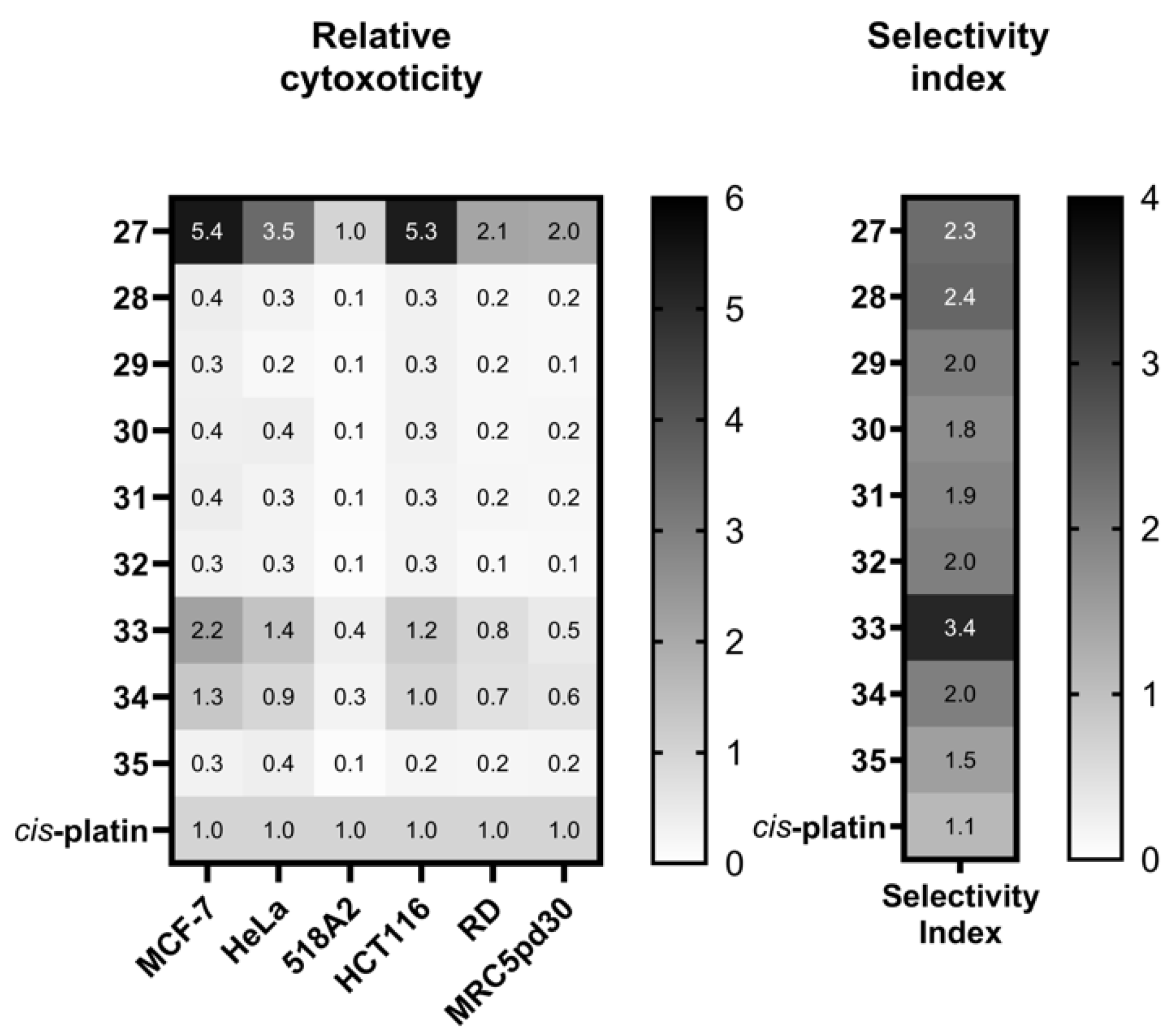

An analogue Ru(II) complex with tris(pyrazol-1-yl)methane has also been studied [

50]. The cytotoxicity of nine Ru scorpionates (

32-

40,

Figure 4) was evaluated against human cervical carcinoma (HeLa), colorectal carcinoma (HCT116), rhabdomyosarcoma (RD), breast cancer (MCF-7), and skin melanoma (518A2) cell lines, as well as against non-tumoural human fibroblasts (MRC5pd30), using cisplatin as a control. All compounds exhibited anticancer activity in micromolar range, and Ru(II) scorpionates

38 and

39 exhibited an antiproliferative activity comparable to that of cisplatin. The highest cytotoxic effect was shown by compound

32, which was 2 to 3 times higher than the one exhibited by cisplatin for four of the cancer cell lines tested. Furthermore, all the complexes have shown better selectivity towards cancerous cell lines over noncancerous one compared to cisplatin (

Figure 5).

To complement the cell viability study, the mechanism of inhibition the growth of cancer cells was also probed. The primary mechanism of action of Ru(II) Tpm complexes was found to be the disruption of calcium homeostasis, specifically by inhibiting mitochondrial calcium intake. Although ruthenium complexes are known to affect many different metabolic pathways of cells, this is the first study that establishes a direct involvement of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis regulation in the biological activity of Ru complexes against cancer cells.

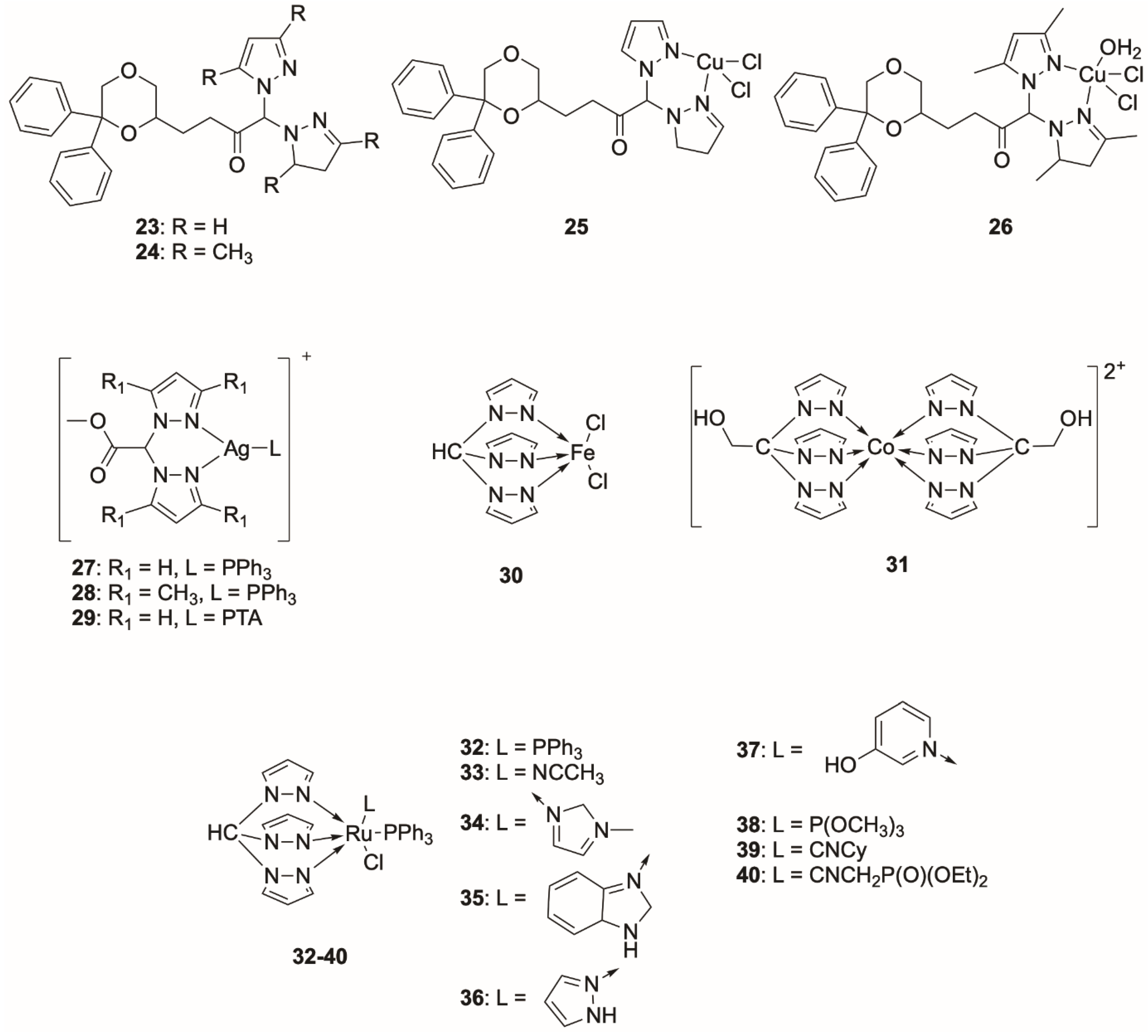

Poly(pyrazol-1-ylmethyl)amine Complexes

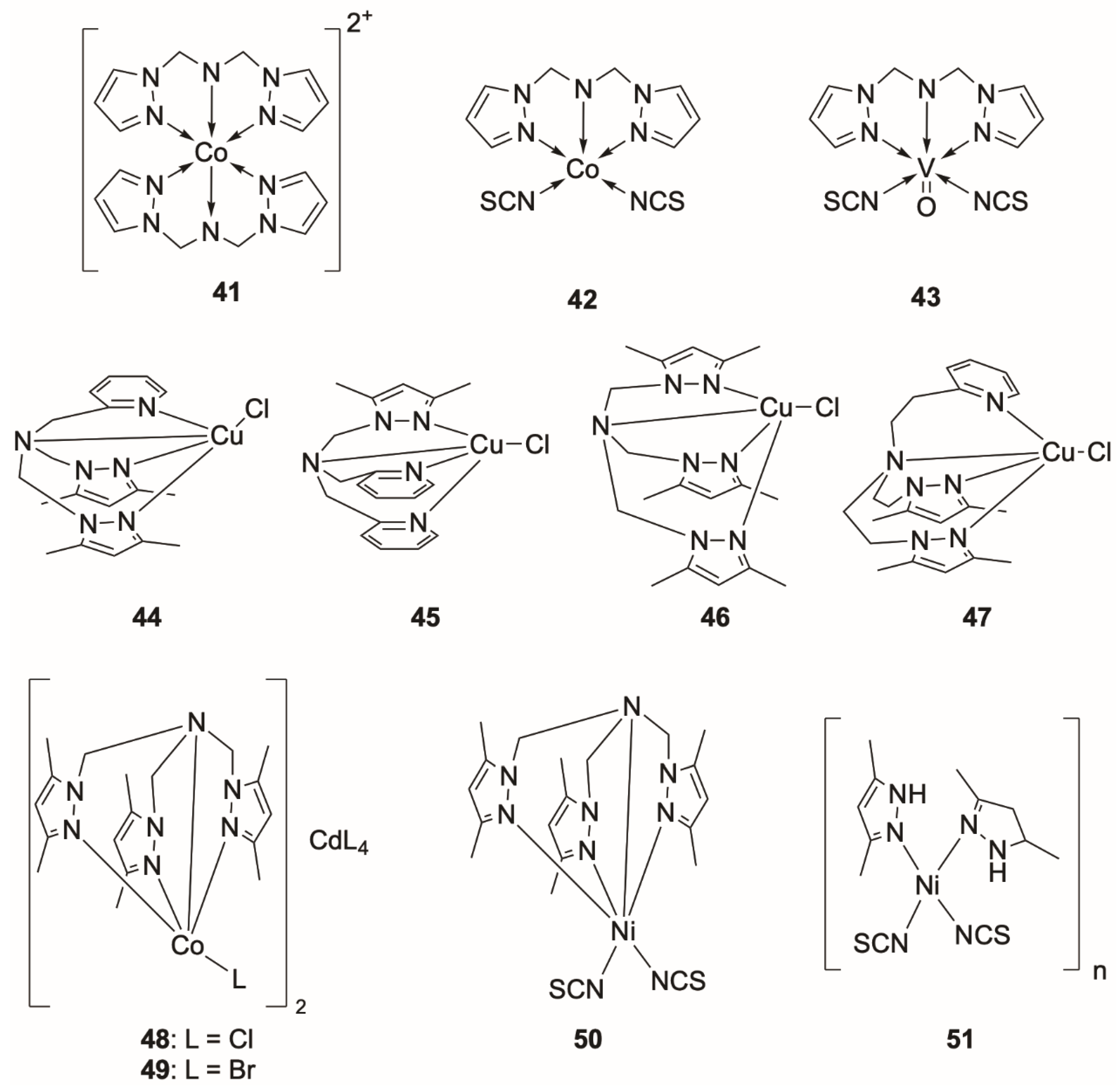

Cobalt and vanadium scorpionate complexes, with a dipolar tridentate

N,N-bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-ylmethyl)amine ligand (

41-

43,

Figure 6) has also been studied [

17] . The cytotoxic effects of the complexes were tested against human liver Hep G2cancer cell line and the non-tumoural Chinese hamster ovary cell line CHO-K1. Complexes

41 and

42 exhibited promising cytotoxicity against the Hep G2 cancer cell line, with IC

50 values of 22 µM for complex

41 (comparable to that of cisplatin, 21.3 µM) and an IC

50 value of 38 µM for complex

42. The vanadium complex

43 displayed a lower anticancer activity, with an IC

50 value of 45.6 µM, nearly twice that of cisplatin. Despite this, all the complexes exhibited better selectivity towards cancer cells than cisplatin, with antiproliferative indices of 5.5 for

41, 7.0 for

42, and 2.7 µM for

43, while cisplatin had a selectivity index of only 0.9 µM. Flow cytometry studies showed that these complexes induce cell death through different mechanisms. While cobalt complexes

41-

42 predominantly initiated cancer cell death through necrosis, complex

43 demonstrated the ability to induce apoptosis. Moreover, real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that all the complexes are able to regulate the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9, suggesting their potential in not only killing cancer cells but also in targeting mechanisms that contribute to tumour growth and metastasis.

Copper(II) complexes with similar ligands (

44-

47,

Figure 6) were also studied for their cytotoxic effects against ovarian cancer (A2780), cisplatin-resistant (A2780R), human osteosarcoma (HOS), and colon carcinoma (CaCo-2) cell lines [

54], compared to the standard chemotherapeutics cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and carboplatin.

While oxaliplatin and carboplatin showed no significant cytotoxicity against the tested lines, cisplatin demonstrated moderate activity, particularly against A2780, A2780R, and HOS, with IC50 values 20.1 μM, 45.7 μM, 47.4 μM, respectively. Complex 47 exhibited the highest activity among all tested compounds, with IC50 values as low as 1.4 μM for A2780, and significantly lower than cisplatin for A2780R and HOS, at 8.3 μM and 4.7 μM, respectively.

Further studies were conducted to assess the metabolic stability and protein interactions of the complexes 44 and 47. Complex 44 was shown to degrade in the presence of L-cysteine, losing its 3,5-dimethylpyrazolylmethane ligand, and forming a stable adduct with cytochrome c. Complex 46, on the other hand, didn’t exhibit any signs of degradation with L-cysteine or glutathione and was able to form two types of adducts with cytochrome c. This difference in stability and protein interaction is likely to reflect on the different cytotoxic activity of the complexes, offering insights into their potential therapeutic mechanisms.

Cobalt complexes with a cadmium counter ion (

48-

49,

Figure 6) were also analysed for their anticancer activity [

55] against colorectal adenocarcinoma (SW480 and SW620), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), and lung carcinoma (A549) cell lines, comparing to their effect on non-cancerous fibroblasts (BJ).

The results revealed promising anticancer activity, with both complexes displaying IC50 values in the low micromolar range: 8.2 (HepG2), 18.1 (A549), 3.3 (SW480), and 2.7 µM (SW620) for complex 48, and 3.8 (HepG2), 4.5 (A549), 4.4 (SW480), and 1.9 µM (SW620) for complex 49. Importantly, the activity of complex 49 surpassed that of cisplatin across all tested cancer cell lines, also demonstrating superior selectivity. However, both complexes displayed lower cytotoxicity than that of the isolated cadmium salts, and were nearly as toxic to non-cancerous BJ fibroblasts. This may suggest that the primary source of cytotoxicity might stem from the anionic component of the complex, prompting further developments in the synthesis of these complexes.

Nickel(II) complexes of tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-ylmethyl)amine and 3,5-dimethylpyrazole ligands (

50 and

51,

Figure 6) were also probed for their cytotoxic potential against the same cell lines [

56].

The preliminary cytotoxicity study with SW610 and BJ cell lines have shown that the Ni complex 50 is 10 times more toxic towards colorectal adenocarcinoma and at the same time 8-fold less toxic against fibroblast cell line compared to the pyrazole complex 51. Furthermore, comparison of complex 50 with cisplatin revealed that the Ni complex exhibited a cytotoxicity profile similar to that of cisplatin for SW480 and A549 cells. However, its activity against SW620 was lower than that of cisplatin, and it showed no significant effect against HepG2. Notably, complex 50 was found to be three times less toxic to fibroblasts compared to cisplatin, with IC50 values of 40.8 µM and 13.0 µM, respectively. This suggests that complex 50 possesses higher selectivity for cancer cells over non-cancerous cells, highlighting its potential as a selective anticancer agent.

Flow cytometry analysis of the SW620 cell line provided insights into the cell death mechanisms induced by both Ni complexes. Complex

50, at 100 µM, predominantly induced apoptosis, with 36.7% of cells in early apoptosis and 61.9% in late apoptosis. Conversely, the Ni pyrazole complex

51 induced necrosis in 30% of cells, with only 18% undergoing apoptosis. In comparison, cisplatin induced apoptosis in 82.1% of cells and necrosis in 15.4%. These findings suggest that complex

50 not only exhibits potent cytotoxicity but predominantly promotes apoptosis (over necrosis), a preferred mechanism for anticancer therapies [

57].

Conclusion

In this review, we sought to highlight the emerging potential of various scorpionate complexes and their ligands, particularly in the context of anticancer research. While these compounds have already demonstrated a wide range of biological activities, their full potential in biomedical applications, especially cancer therapy, remains under-explored.

Copper complexes show strong anticancer activities across various studies, indicating that their redox activity can be useful targeting cancer cells. Zinc complexes also exhibit promising activity, especially against difficult-to-treat cancers like triple-negative breast cancer. Despite being redox-inactive, zinc complexes exhibit DNA/protein interactions that may contribute to their cytotoxicity. Ruthenium complexes demonstrate selective toxicity by disrupting mitochondrial calcium homeostasis, a unique mechanism that may afford specificity to cancer cells. Silver complexes show significant potency, particularly in resistant cancer cell lines, suggesting they could be valuable in targeting drug-resistant cancers.

Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)borate ligands and derivatives with sulfur-containing heterocycles (e.g., 2-mercaptobenzimidazole) tend to increase stability and cytotoxicity in copper complexes, indicating that sulfur ligands may enhance coordination stability and bioactivity. Unsubstituted pyrazoles often yield complexes with higher cytotoxic activity than those with bulkier or substituted ligands, likely due to improved cellular uptake and interaction with biomolecules, but ligand selection is still a trial-and-error approach. Dipodal ligands such as tridentate amines confer selective cytotoxicity and, in cobalt and vanadium complexes, modulate gene expression related to metastasis, indicating potential anti-metastatic properties.

Regarding the mechanism of action, for redox-active metals like copper, complexes that facilitate ROS production and/or inhibit thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) can enhance cancer cell cytotoxicity. Designing complexes that optimize these mechanisms may improve anticancer efficacy. Selectivity may come from mechanisms such as the observed mitochondrial disruption in Ru complexes or paraptosis (an alternative to apoptosis), making these complexes valuable tools for cancers with apoptosis resistance. Targeting pathways like mitochondrial calcium regulation or inducing endoreticulum stress may enhance selectivity for cancer cells.

These ligands have shown significant success in recent studies; however, further refinement and optimization could greatly enhance their therapeutic efficacy. Continued research focusing on their structural diversity, metal coordination properties, and biological interactions could pave the way for the development of highly potent and selective anticancer agents, positioning scorpionate complexes as promising candidates in next-generation therapeutic strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviation List

| 2008 |

human ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| 518A2 |

human metastatic melanoma cell line |

| A431 |

human cervical carcinoma cell line |

| A549 |

human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line |

| A2780 |

human ovarian cancer cell line |

| A2780R |

cisplatin resistant human ovarian cancer cell line |

| B16 |

mouse melanoma cell line |

| BJ |

human fibroblast cell line |

| C13 |

cisplatin resistant human ovarian cancer cell line |

| CaCo-2 |

human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Caki-2 |

human renal carcinoma cell line |

| CHO-K1 |

chinese hamster ovary cell line |

| H460 |

human lung carcinoma cell line |

| HaCaT |

human immortalized keratinocytes cell line |

| HCC1937 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| HCT116 |

human colon cancer cell line |

| HCT-15 |

human colorectal cancer cell line |

| HeLa |

human cervical cancer cell line |

| HepG2 |

human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| HOS |

human osteosarcoma cell line |

| Hs 578T |

human breast cancer cell line |

| MCF-7 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| MDA-MB-231 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| MDA-MB-468 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| MRC5pd30 |

Medical Research Council human fibroblast cell line 5 |

| NMDA |

N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PCy3 |

tricyclohexylphosphine |

| PPh3 |

triphenylphosphine |

| PTA |

1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphadamantane |

| PSN-1 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| RD |

human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| SKBR3 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| SW620 |

human colon cancer cell line |

| SW480 |

human colon cancer cell line |

| SW116 |

human colorectal cancer cell line |

| T24 |

human bladder cancer cell line |

| TNBC |

triple-negative breast cancer |

| Tp |

tris(pyrazol-1-yl)borate |

| TrxR |

thioredoxin reductase |

| U1285 |

human breast cancer cell line |

| PC3 |

human prostate cancer cell line |

References

- Anand, U.; Dey, A.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Sanyal, R.; Mishra, A.; Pandey, D.K.; De Falco, V.; Upadhyay, A.; Kandimalla, R.; Chaudhary, A. , et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 1367–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilsed, C.M.; Fisher, S.A.; Nowak, A.K.; Lake, R.A.; Lesterhuis, W.J. Cancer chemotherapy: insights into cellular and tumor microenvironmental mechanisms of action. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 960317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safa, A.R. Drug and apoptosis resistance in cancer stem cells: a puzzle with many pieces. Cancer Drug Resist 2022, 5, 850–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurgali, K.; Jagoe, R.T.; Abalo, R. Editorial: Adverse Effects of Cancer Chemotherapy: Anything New to Improve Tolerance and Reduce Sequelae? Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, S. Is it time for a new paradigm for systemic cancer treatment? Lessons from a century of cancer chemotherapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, H.Y.; Lee, H.Y. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med 2022, 54, 1670–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, S.; Khaksar, S.; Aliabadi, A.; Panjehpour, A.; Motieiyan, E.; Marabello, D.; Faraji, M.H.; Beihaghi, M. Cytotoxicity and mechanism of action of metal complexes: An overview. Toxicology 2023, 492, 153516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.-M.; Büsselberg, D. Cisplatin as an Anti-Tumor Drug: Cellular Mechanisms of Activity, Drug Resistance and Induced Side Effects. Cancers 2011, 3, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, Z.; Ge, Q.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Z. Antitumor activity of tridentate pincer and related metal complexes. Org Biomol Chem 2021, 19, 5254–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.A.; Martins, L. Novel Chemotherapeutic Agents - The Contribution of Scorpionates. Curr Med Chem 2019, 26, 7452–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimenko, S. Polypyrazolylborates: Scorpionates. Journal of Chemical Education 2005, 82, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricker, S.P. Medical uses of gold compounds: Past, present and future. Gold Bulletin 1996, 29, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezza, M.; Hindo, S.; Chen, D.; Davenport, A.; Schmitt, S.; Tomco, D.; Dou, Q.P. Novel metals and metal complexes as platforms for cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Des 2010, 16, 1813–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Beyene, B.B.; Datta, A.; Garribba, E.; Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Silva, A.; Fernandes, A.R.; Hung, C.-H. EPR and electrochemical interpretation of bispyrazolylacetate anchored Ni(ii) and Mn(ii) complexes: cytotoxicity and anti-proliferative activity towards human cancer cell lines. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 9126–9139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroń, A.; Czerwińska, K.; Machura, B.; Raposo, L.; Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Fernandes, A.R.; Małecki, J.G.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Kula, S.; Krompiec, S. Spectroscopy, electrochemistry and antiproliferative properties of Au(iii), Pt(ii) and Cu(ii) complexes bearing modified 2,2′:6′,2′′-terpyridine ligands. Dalton Transactions 2018, 47, 6444–6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berasaluce, I.; Cseh, K.; Roller, A.; Hejl, M.; Heffeter, P.; Berger, W.; Jakupec, M.A.; Kandioller, W.; Malarek, M.S.; Keppler, B.K. The First Anticancer Tris(pyrazolyl)borate Molybdenum(IV) Complexes: Tested in Vitro and in Vivo-A Comparison of O,O-, S,O-, and N,N-Chelate Effects. Chemistry 2020, 26, 2211–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyszka-Czochara, M.; Adach, A.; Grabowski, T.; Konieczny, P.; Pasko, P.; Ortyl, J.; Świergosz, T.; Majka, M. Selective Cytotoxicity of Complexes with N,N,N-Donor Dipodal Ligand in Tumor Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwane, M.; Dorairaj, D.P.; Chang, Y.L.; Karvembu, R.; Huang, Y.H.; Chang, H.W.; Hsu, S.C.N. Tris-(2-pyridyl)-pyrazolyl Borate Zinc(II) Complexes: Synthesis, DNA/Protein Binding and In Vitro Cytotoxicity Studies. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimenko, S. Boron-pyrazole chemistry. II. Poly(1-pyrazolyl)-borates. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1967, 89, 3170–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăbăcaru, A.; Khan, R.A.; Lupidi, G.; Pettinari, C. Synthesis, Characterization and Assessment of the Antioxidant Activity of Cu(II), Zn(II) and Cd(II) Complexes Derived from Scorpionate Ligands. Molecules 2020, 25, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Fernandes, C.; Campello, M.P.C.; Paulo, A. Metal complexes of tridentate tripod ligands in medical imaging and therapy. Polyhedron 2017, 125, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazelaar, C.G.J.; Slootweg, J.C.; Lammertsma, K. Coordination chemistry of tris(azolyl)phosphines. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2018, 356, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitto, F.; Wagler, J.; Kroke, E. 3,5-Dimethylpyrazole Derivatives of (Hydrido)chlorosilanes. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2012, 2012, 2402–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adach, A. Review: an overview of recent developments in coordination chemistry of polypyrazolylmethylamines. Complexes with N-scorpionate ligands created in situ from pyrazole derivatives and zerovalent metals. Journal of Coordination Chemistry 2017, 70, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Li, J.; Easley, C.R.; Brennessel, W.W.; Loloee, R.; Chavez, F.A. Synthesis, structure, and characterization of tris(1-ethyl-4-isopropyl-imidazolyl-қN)phosphine nickel(II) complexes. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2019, 489, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, A.K.; Guard, L.M.; Hazari, N.; Luzik, E.D. Synthesis of Mg Complexes Supported by Tris-(1-pyrazolyl)phosphine. Australian Journal of Chemistry 2013, 66, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, E.E.; Rheingold, A.L.; Rabinovich, D. Methyltris(pyrazolyl)silanes: new tripodal nitrogen-donor ligands. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 1999, 2, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, E.E.; Rabinovich, D.; Incarvito, C.D.; Concolino, T.E.; Rheingold, A.L. Syntheses and Structures of Methyltris(pyrazolyl)silane Complexes of the Group 6 Metals. Inorganic Chemistry 2000, 39, 1561–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, A.; Tenia, R.; Martínez, M.; López-Linares, F.; Albano, C.; Diaz-Barrios, A.; Sánchez, Y.; Catarí, E.; Casas, E.; Pekerar, S. , et al. Iron(II) and cobalt(II) tris(2-pyridyl)phosphine and tris(2-pyridyl)amine catalysts for the ethylene polymerization. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 2007, 265, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setifi, Z.; Cubillán, N.; Glidewell, C.; Gil, D.M.; Torabi, E.; Morales-Toyo, M.; Dege, N.; Setifi, F.; Mirzaei, M. A combined experimental, Hirshfeld surface analysis, and theoretical study on fac-[tri(azido)(tris(2-pyridyl)amine)iron(III)]. Polyhedron 2023, 233, 116320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, F.A.; Albering, J.H.; Vicente, R.; Louka, F.R.; Gallo, A.A.; Massoud, S.S. Copper(II) complexes derived from tripodal tris[(2-ethyl-(1-pyrazolyl)]amine. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2011, 365, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.M.D.R.S.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Tris(pyrazol-1-yl)methane metal complexes for catalytic mild oxidative functionalizations of alkanes, alkenes and ketones. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2014, 265, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Pellei, M.; Lobbia, G.G.; Papini, G. Synthesis and Properties of Poly(pyrazolyl)borate and Related Boron-Centered Scorpionate Ligands. Part A: Pyrazole-Based Systems. Mini-Reviews in Organic Chemistry 2010, 7, 84–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.A.; Domingos, Â.; Santos, I.C.d.; Marques, N.; Takats, J. Synthesis and characterization of uranium(III) compounds supported by the hydrotris(3,5-dimethyl-pyrazolyl)borate ligand: Crystal structures of [U(TpMe2)2(X)] complexes (X=OC6H2-2,4,6-Me3, dmpz, Cl). Polyhedron 2005, 24, 3038–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliu, K.O.; Maunder, G.H.; Ferguson, M.J.; Sella, A.; Takats, J. Synthesis and structure of heteroleptic ytterbium (II) tetrahydroborate complexes. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2009, 362, 4616–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Jensen, M.P. Half-Sandwich Scorpionates as Nitrene Transfer Catalysts. Organometallics 2012, 31, 8055–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Fernández-Baeza, J.; Lara-Sánchez, A.; Sánchez-Barba, L.F. Metal complexes with heteroscorpionate ligands based on the bis(pyrazol-1-yl)methane moiety: Catalytic chemistry. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2013, 257, 1806–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.; Mark, D.S. The Bioinorganic Chemistry of Methimazole Based Soft Scorpionates. Current Bioactive Compounds 2009, 5, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Lobbia, G.G.; Santini, C.; Spagna, R.; Camalli, M.; Fedeli, D.; Falcioni, G. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of new copper(i) complexes of scorpionate and water soluble phosphane ligands. Dalton Transactions 2004. [CrossRef]

- Berasaluce, I.; Cseh, K.; Roller, A.; Hejl, M.; Heffeter, P.; Berger, W.; Jakupec, M.A.; Kandioller, W.; Malarek, M.S.; Keppler, B.K. The First Anticancer Tris(pyrazolyl)borate Molybdenum(IV) Complexes: Tested in Vitro and in Vivo—A Comparison of O,O-, S,O-, and N,N-Chelate Effects. Chemistry – A European Journal 2020, 26, 2211–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghih, Z.; Neshat, A.; Mastrorilli, P.; Gallo, V.; Faghih, Z.; Gilanchi, S. Cu(II), Ni(II) and Co(II) complexes with homoscorpionate Bis(2-Mercaptobenzimidazolyl) and Bis(2-Mercaptobenzothiazolyl)borate ligands: Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity studies. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2020, 512, 119896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.A.; Suresh, B. Biological activities of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole derivatives: a review. Sci Pharm 2012, 80, 789–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.; Chhabra, S.; Shrivastava, S.K.; Mishra, P. Benzimidazole: a promising pharmacophore. Medicinal Chemistry Research 2013, 22, 5077–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour, M.; Soltani, B.; Molavi, O.; Shayanfar, A.; Mehdizadeh Aghdam, E.; Ziegler, C.J. Copper (II) complexes based bis(pyrazolyl)borate derivatives as efficient anticancer agents: synthesis, characterization, X-ray structure, cytotoxicity, molecular docking and QSAR studies. Chemical Papers 2022, 76, 7343–7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W. Zinc in Cellular Regulation: The Nature and Significance of "Zinc Signals". Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yu, P.; Chan, W.N.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Leung, K.T.; Lo, K.W.; Yu, J.; Tse, G.M.K. , et al. Cellular zinc metabolism and zinc signaling: from biological functions to diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.B.; Amantini, C.; Santoni, G.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C.; Cimarelli, C.; Marcantoni, E.; Petrini, M.; Del Bello, F.; Giorgioni, G. , et al. Novel antitumor copper(ii) complexes designed to act through synergistic mechanisms of action, due to the presence of an NMDA receptor ligand and copper in the same chemical entity. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 11878–11887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Santini, C.; Bagnarelli, L.; Caviglia, M.; Sgarbossa, P.; De Franco, M.; Zancato, M.; Marzano, C.; Gandin, V. Novel Silver Complexes Based on Phosphanes and Ester Derivatives of Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetate Ligands Targeting TrxR: New Promising Chemotherapeutic Tools Relevant to SCLC Management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.M.G.; Pinheiro, P.F.; Camões, S.P.; Ribeiro, A.P.C.; Martins, L.; Miranda, J.P.G.; Justino, G.C. Exploring the Mechanisms behind the Anti-Tumoral Effects of Model C-Scorpionate Complexes. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervinka, J.; Gobbo, A.; Biancalana, L.; Markova, L.; Novohradsky, V.; Guelfi, M.; Zacchini, S.; Kasparkova, J.; Brabec, V.; Marchetti, F. Ruthenium(II)-Tris-pyrazolylmethane Complexes Inhibit Cancer Cell Growth by Disrupting Mitochondrial Calcium Homeostasis. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 10567–10587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, W.G.; Gao, G.; Memoli, V.A.; Pang, R.H.; Lynch, L. Breast cancer expresses functional NMDA receptors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010, 122, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Dharan, A.; P, V.J.; Pal, S.; Nair, B.G.; Kar, R.; Mishra, N. Paraptosis: a unique cell death mode for targeting cancer. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1159409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Soltani, A.; Ghahremanloo, A.; Javid, H.; Hashemy, S.I. The thioredoxin system and cancer therapy: a review. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2019, 84, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoud, S.S.; Louka, F.R.; Ducharme, G.T.; Fischer, R.C.; Mautner, F.A.; Vančo, J.; Herchel, R.; Dvořák, Z.; Trávníček, Z. Copper(II) complexes based on tripodal pyrazolyl amines: Synthesis, structure, magnetic properties and anticancer activity. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 2018, 180, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adach, A.; Daszkiewicz, M.; Tyszka-Czochara, M. Comparative X-ray, vibrational, theoretical and biological studies of new in situ formed [CoLSX]2[CdX4] halogenocadmate(II) complexes containing N-scorpionate ligand. Polyhedron 2020, 175, 114229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adach, A.; Tyszka-Czochara, M.; Bukowska-Strakova, K.; Rejnhardt, P.; Daszkiewicz, M. In situ synthesis, crystal structure, selective anticancer and proapoptotic activity of complexes isolated from the system containing zerovalent nickel and pyrazole derivatives. Polyhedron 2022, 223, 115943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, C.M.; Singh, A.T.K. Apoptosis: A Target for Anticancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).