Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein on Allergic Asthma Model Mice

2.2. Transcriptomic Results

2.2.1. RNA-Seq Results and Quality Control

| Gene | Reference sequence | Forward primer (F) | Reverse primer (R) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD28 | NM_007642.4 | AACCAGAGAAGGCCAAGATTA | TATGTGTCAAGAGGCTGACT |

| Icos | NM_017480.3 | ATGGTGTTCTCTCTCTTCAGAT | CTCACACAGAAAGGACCG |

| CD48 | NM_007649.5 | TTCATCCCTAGCAGTGTTCC | GCAGACGTTCAGTAACACATT |

| CD247 | NM_031162.4 | TTCACCTGCTGATGTCACTT | CTCGTCATGAAATGGTGGC |

| Cd40lg | NM_011616.3 | AGGCACATAGAGCTGGAATA | GGGTTGCTGTTTCAGATTGTA |

| Itgal | NM_001253872.1 | GGAGAACTCCACTCTCTATATCA | TGTTGTGGTCATAGGCAGAT |

| Itgb2 | NM_008404.5 | TGGTAGGTGTCGTACTGATT | TCCTTCTCAAAGCGCCTGTA |

| CCL5 | NM_013653.3 | AACTATTTGGAGATGAGCTAGG | GGACTAGAGCAAGCAATGAC |

| β-Actin | NM_007393.5 | GGCTCCTAGCACCATGAAGA | AGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGCC |

| Sample | Raw Reads (M) |

Raw Bases (G) |

Clean Reads (M) |

Clean Bases (G) |

Valid Bases (%) |

Q30 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 41.49 | 6.14 | 40.87 | 6.05 | 98.5 | 97.15 |

| N2 | 44.00 | 6.54 | 43.54 | 6.47 | 98.94 | 97.2 |

| N3 | 48.09 | 7.13 | 47.46 | 7.03 | 98.68 | 97.1 |

| M1 | 47.62 | 7.06 | 47.03 | 6.97 | 98.76 | 97.17 |

| M2 | 47.10 | 7.00 | 46.61 | 6.92 | 98.95 | 97.04 |

| M3 | 46.40 | 6.88 | 45.85 | 6.8 | 98.83 | 97.05 |

| T1 | 47.45 | 7.06 | 47.03 | 7.00 | 99.12 | 97.12 |

| T2 | 47.66 | 7.09 | 47.23 | 7.03 | 99.11 | 96.95 |

| T3 | 47.04 | 6.99 | 46.58 | 6.92 | 99.02 | 96.85 |

2.2.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

2.2.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis of the DEGs Between the M and N Groups

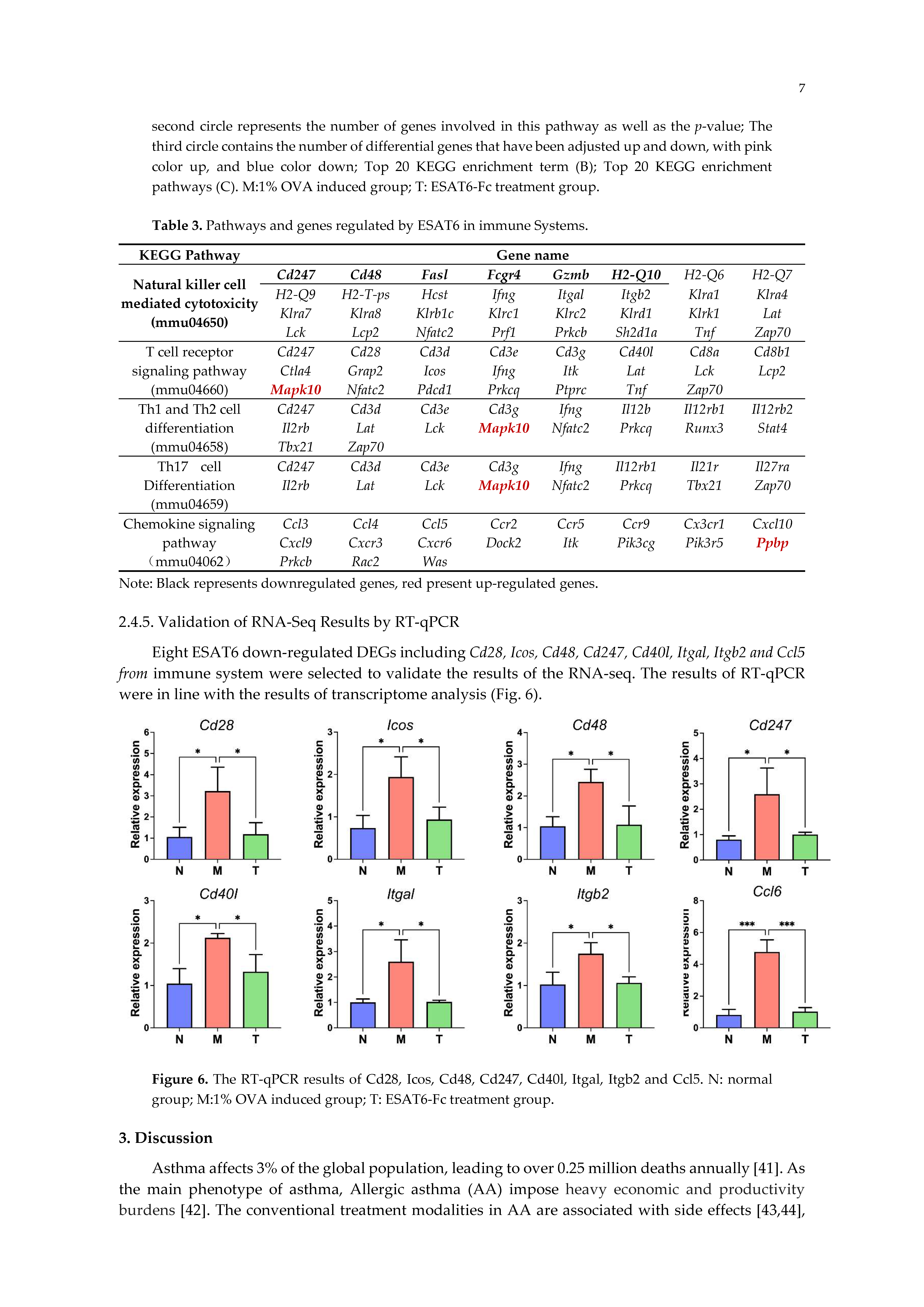

2.2.4. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Pathways and Genes Regulated by ESAT6

2.4.5. Validation of RNA-Seq Results by RT-qPCR

3. Discussion

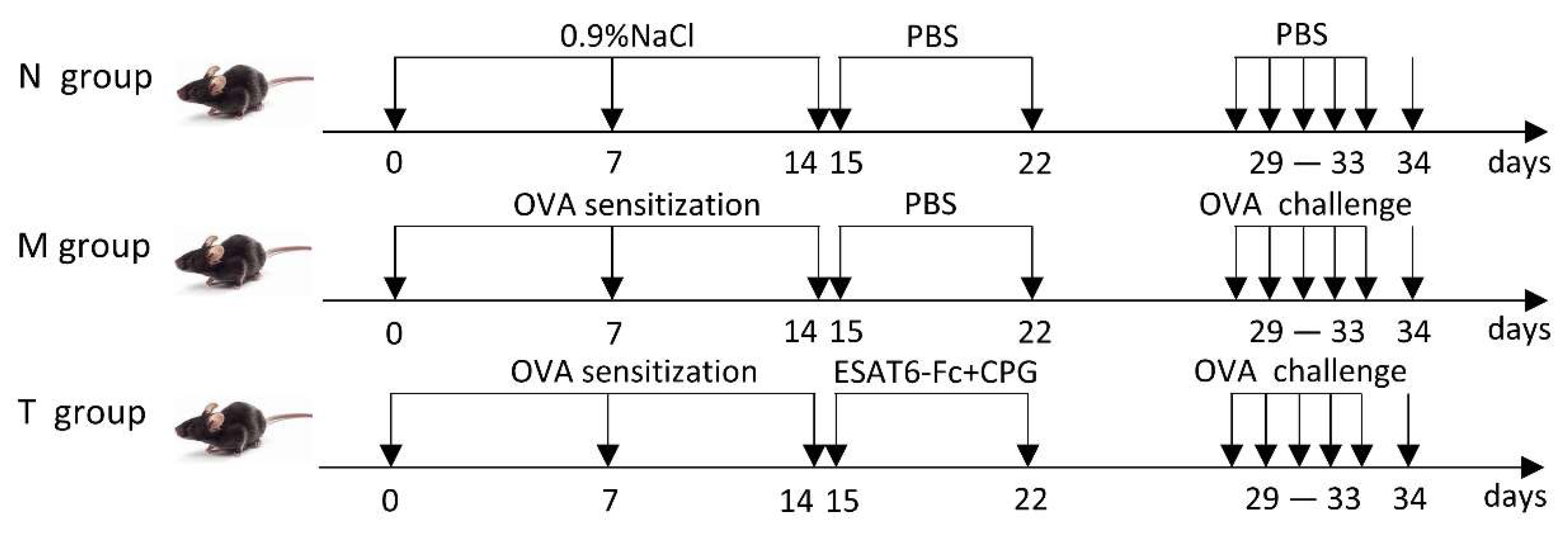

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Construction of Eukaryotic Plasmid and ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein

4.2. Animals and Grouping

4.3. Allergic Asthma Mice Model

4.4. Ag85B-Fc Fusion Protein Treatment

4.5. Flow Cytometry

4.6. Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.7. Lung Histological Analysis

4.8. cDNA Library Construction and RNA-seq Analysis

4.9. KEGG Pathways Enrichment Analysis

4.10. Validation of RNA-seq Results

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conde, E.; Bertrand, R.; Balbino, B.; Bonnefoy, J.; Stackowicz, J.; Caillot, N.; Colaone, F.; Hamdi, S.; Houmadi, R.; Loste, A.; et al. Dual vaccination against IL-4 and IL-13 protects against chronic allergic asthma in mice. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Córdova, V.; Berra-Romani, R.; Flores Mendoza, L.K.; Reyes-Leyva, J. Th17 Lymphocytes in Children with Asthma: Do They Influence Control? Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2021, 34, 147–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morianos, I.; Semitekolou, M. Dendritic Cells: Critical Regulators of Allergic Asthma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Yamane, H.; Paul, W.E. Differentiation of Effector CD4 T Cell Populations. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 28, 445–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, J.; Adir, Y.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Celis-Preciado, C.A.; Colodenco, F.D.; Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Lababidi, H.; Ledanois, O.; Mahoub, B.; Perng, D.-W.; et al. Type 2 inflammation in asthma and other airway diseases. ERJ Open Res. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Hu, J.; Xu, W.; Dong, J. ; Distinct spatial and temporal roles for Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells in asthma. Front Immunol. 2022, 12, 974066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, C.A.; Arkwright, P.D.; Brüggen, M.-C.; Busse, W.; Gadina, M.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Kabashima, K.; Mitamura, Y.; Vian, L.; Wu, J.; et al. Type 2 immunity in the skin and lungs. Allergy 2020, 75, 1582–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, K.; Ogasawara, M. The Role of Histamine in the Pathophysiology of Asthma and the Clinical Efficacy of Antihistamines in Asthma Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, Q.; Canning, B.J. Evidence for autocrine and paracrine regulation of allergen-induced mast cell mediator release in the guinea pig airways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 822, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, C.A. Does the epithelial barrier hypothesis explain the increase in allergy, autoimmunity and other chronic conditions? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Gu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Han, S.; Che, H. Effects of Fatty Acid Oxidation and Its Regulation on Dendritic Cell-Mediated Immune Responses in Allergies: An Immunometabolism Perspective. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.C.; Ownby, D.R. The infant gut bacterial microbiota and risk of pediatric asthma and allergic diseases. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalewicz-Kulbat, M.; Locht, C. BCG for the prevention and treatment of allergic asthma. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Tang, A.-Z.; Xu, M.-L.; Chen, H.-L.; Wang, F.; Li, C.-Q. Mycobacterium vaccae attenuates airway inflammation by inhibiting autophagy and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation mouse model. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 173, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anes, E.; Pires, D.; Mandal, M.; Azevedo-Pereira, J.M. ESAT-6 a Major Virulence Factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zonghai, C.; Tao, L.; Pengjiao, M.; Liang, G.; Rongchuan, Z.; Xinyan, W.; Wenyi, N.; Wei, L.; Yi, W.; Lang, B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT6 modulates host innate immunity by downregulating miR-222-3p target PTEN. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.S. Chemical and Biological Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-Specific ESAT6-Like Proteins and Their Potentials in the Prevention of Tuberculosis and Asthma. Med Princ. Pract. 2023, 32, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyzik, M.; Kozicky, L.K.; Gandhi, A.K.; Blumberg, R.S. The therapeutic age of the neonatal Fc receptor. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Gao, F.; Yu, L. The role of immunoglobulin transport receptor, neonatal Fc receptor in mucosal infection and immunity and therapeutic intervention. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 138, 112583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, R.; Zolbanin, N.M.; Rafatpanah, H.; Majidi, J.; Kazemi, T. Fc-fusion Proteins in Therapy: An Updated View. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Z. Telitacicept, a novel humanized, recombinant TACI-Fc fusion protein, for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs Today 2022, 58, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Gao, L.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Yin, H.; Lu, Q. TIGIT-Fc fusion protein alleviates murine lupus nephritis through the regulation of SPI-B-PAX5-XBP1 axis-mediated B-cell differentiation. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 139, 103087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-X.; Li, H.; Bai, L.; Yao, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.-S.; Wan, Q.-F. Bioinformatics analysis of ceRNA regulatory network of baicalin in alleviating pathological joint alterations in CIA rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 951, 175757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, R.; Michal, J.J.; Zhang, S.; Dodson, M.V.; Zhang, Z.; Harland, R.M. Whole transcriptome analysis with sequencing: methods, challenges and potential solutions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3425–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rish, A.J.; Drennen, J.K.; Anderson, C.A. Metabolic trends of Chinese hamster ovary cells in biopharmaceutical production under batch and fed-batch conditions. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 38, e3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.; Dickson, A.J. Reprogramming of Chinese hamster ovary cells towards enhanced protein secretion. Metab. Eng. 2021, 69, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böll, S.; Ziemann, S.; Ohl, K.; Klemm, P.; Rieg, A.D.; Gulbins, E.; Becker, K.A.; Kamler, M.; Wagner, N.; Uhlig, S.; et al. Acid sphingomyelinase regulates TH2 cytokine release and bronchial asthma. Allergy 2019, 75, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, T.; Rajendrakumar, A.M.; Acharya, G.; Miao, Z.; Varghese, B.P.; Yu, H.; Dhakal, B.; LeRoith, T.; Karunakaran, A. An FcRn-targeted mucosal vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myou, S.; Leff, A.R.; Myo, S.; Boetticher, E.; Tong, J.; Meliton, A.Y.; Liu, J.; Munoz, N.M.; Zhu, X. Blockade of Inflammation and Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Immune-sensitized Mice by Dominant-Negative Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase–TAT. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Masuda, T.; Tokuoka, S.; Komai, M.; Nagao, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagai, H. The effect of allergen-induced airway inflammation on airway remodeling in a murine model of allergic asthma. Inflamm. Res. 2001, 50, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemmannur, S.V.; Badhwar, A.J.; Mirlekar, B.; Malonia, S.K.; Gupta, M.; Wadhwa, N.; Bopanna, R.; Mabalirajan, U.; Majumdar, S.; Ghosh, B.; et al. Nuclear matrix binding protein SMAR1 regulates T-cell differentiation and allergic airway disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Q.; Li, K.; Song, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, H. Nitric oxide hinders club cell proliferation through Gdpd2 during allergic airway inflammation. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Netto, K.G.; Sokulsky, L.A.; Zhou, L.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; et al. Single-cell RNA transcriptomic analysis identifies Creb5 and CD11b-DCs as regulator of asthma exacerbations. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scordamaglia, F.; Balsamo, M.; Scordamaglia, A.; Moretta, A.; Mingari, M.C.; Canonica, G.W.; Moretta, L.; Vitale, M. Perturbations of natural killer cell regulatory functions in respiratory allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.; Diaz-Meco, M.T.; Moscat, J. The signaling adapter p62 is an important mediator of T helper 2 cell function and allergic airway inflammation. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3524–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumes, D.J.; Papadopoulos, M.; Endo, Y.; Onodera, A.; Hirahara, K.; Nakayama, T. Epigenetic regulation of T-helper cell differentiation, memory, and plasticity in allergic asthma. Immunol Rev. 2017, 278, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, A.; Weng, C.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, W.; Li, C. γ-Secretase Inhibitor Alleviates Acute Airway Inflammation of Allergic Asthma in Mice by Downregulating Th17 Cell Differentiation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 258168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamranvar, S.A.; Rani, B.; Johansson, S. Cell Cycle Regulation by Integrin-Mediated Adhesion. Cells 2022, 11, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Kim, M.; Hong, J.Y.; Shim, D.H.; Sol, I.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, J.M.; Sohn, M.H. Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule Stimulates the T-Cell Response in Allergic Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 994–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikovics, K.; Favier, A.-L.; Rocher, M.; Mayinga, C.; Gomez, J.; Dufour-Gaume, F.; Riccobono, D. In Situ Identification of Both IL-4 and IL-10 Cytokine–Receptor Interactions during Tissue Regeneration. Cells 2023, 12, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-H.; Han, Y.-X.; Rong, X.-J.; Shen, Z.; Shen, H.-R.; Kong, L.-F.; Guo, Y.D.; Li, J.-Z.; Xu, B.; Gao, T.-L.; et al. Alleviation of allergic asthma by rosmarinic acid via gut-lung axis. Phytomedicine 2024, 126, 155470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.G.; Miligkos, M.; Xepapadaki, P. A Current Perspective of Allergic Asthma: From Mechanisms to Management. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022, 268, 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Heffler, E.; Madeira, L.N.G.; Ferrando, M.; Puggioni, F.; Racca, F.; Malvezzi, L.; Passalacqua, G.; Canonica, G.W. Inhaled Corticosteroids Safety and Adverse Effects in Patients with Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuberi, F.F.; Haroon, M.A.; Haseeb, A.; Khuhawar, S.M. Role of Montelukast in Asthma and Allergic rhinitis patients. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2020, 36, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.K. The Role of ESX-1 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Pathogenesis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawes, B.L.; Wolsk, H.M.; Carlsson, C.J.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Følsgaard, N.; Stokholm, J.; Bønnelykke, K.; Brix, S.; Schoos, A.M.; Bisgaard, H. Neonatal airway immune profiles and asthma and allergy endpoints in childhood. Allergy 2021, 76, 3713–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellings, P.W.; Steelant, B. Epithelial barriers in allergy and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, C.; Behrendt, A.-K.; Henken, S.; Wölbeling, F.; Maus, U.A.; Hansen, G. Pneumococcal pneumonia suppresses allergy development but preserves respiratory tolerance in mice. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 164, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, A.; Mazón, A.; Nieto, M.; Calderón, R.; Calaforra, S.; Selva, B.; Uixera, S.; Palao, M.J.; Brandi, P.; Conejero, L.; et al. Bacterial Mucosal Immunotherapy with MV130 Prevents Recurrent Wheezing in Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Vera, C.; García-Betancourt, R.; Palacios, P.A.; Müller, M.; Montero, D.A.; Verdugo, C.; Ortiz, F.; Simon, F.; Kalergis, A.M.; González, P.A.; et al. Natural killer T cells in allergic asthma: implications for the development of novel immunotherapeutical strategies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1364774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnicozzi, M.; Sawyer, R.T.; Fenton, M.J. Innate immunity in allergic disease. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 242, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castan, L.; Magnan, A.; Bouchaud, G. Chemokine receptors in allergic diseases. Allergy 2016, 72, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, S.; Azuma, M. The CD28-B7 Family of Co-signaling Molecules. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019, 1189, 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.M.; A Deng, X. Considering B7-CD28 as a family through sequence and structure. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Tian, T.; Pang, W. The role of ICOS in allergic disease: Positive or Negative? Int Immunopharmacol. 2022, 103, 108394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Chang, J.; Lebel, M.; Gervais, N.; Fournier, M.; Gauthier, M.; Suh, W.; Melichar, H.J. The ICOS–ICOSL pathway tunes thymic selection. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2022, 100, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munitz, A.; Bachelet, I.; Levi-Schaffer, F. CD48 as a Novel Target in Asthma Therapy. Recent Patents Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2007, 1, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, O.; Gangwar, R.S.; Seaf, M.; Barhoum, A.; Kerem, E.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Evaluation of Soluble CD48 Levels in Patients with Allergic and Nonallergic Asthma in Relation to Markers of Type 2 and Non-Type 2 Immunity: An Observational Study. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexiu, C.; Xianying, L.; Yingchun, H.; Jiafu, L. Advances in CD247. Scand J Immunol. 2022, 96, e13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.T.; A Revez, J.; Ferreira, M.A.R. Lessons from ten years of genome-wide association studies of asthma. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2017, 6, e165–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Cheng, X.; Truong, B.; Sun, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Molecular basis and therapeutic implications of CD40/CD40L immune checkpoint. Pharmacol Ther. 2021, 219, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y. Establishment of a diagnostic model based on immune-related genes in children with asthma. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Bolduan, V.; Haist, M.; Stege, H.; Hieber, C.; Johann, L.; Schelmbauer, C.; Blanfeld, M.; Karram, K.; Schunke, J. β2 Integrins on Dendritic Cells Modulate Cytokine Signaling and Inflammation-Associated Gene Expression, and Are Required for Induction of Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Cells 2022, 11, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaus, T.; Wilson, A.; Fichter, M.; Bros, M.; Bopp, T.; Grabbe, S. The Role of LFA-1 for the Differentiation and Function of Regulatory T Cells—Lessons Learned from Different Transgenic Mouse Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantero, S.; Alessandri, G.; Spallarossa, D.; Scarso, L.; Rossi, G. LFA-1 expression by blood eosinophils is increased in atopic asthmatic children and is involved in eosinophil locomotion. Eur. Respir. J. 1998, 12, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, R.E.; Guabiraba, R.; Russo, R.C.; Teixeira, M.M. Targeting CCL5 in inflammation. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2013, 17, 1439–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandford, A.J.; Zhu, S.; Bai, T.R.; Fitzgerald, J.M.; Paré, P.D. The role of the C-C chemokine receptor-5 Delta32 polymorphism in asthma and in the production of regulated on activation, normal T cells expressed and secreted. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001, 108, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereinig, S.; Stukova, M.; Zabolotnyh, N.; Ferko, B.; Kittel, C.; Romanova, J.; Vinogradova, T.; Katinger, H.; Kiselev, O.; Egorov, A. Influenza Virus NS Vectors Expressing theMycobacterium tuberculosisESAT-6 Protein Induce CD4+Th1 Immune Response and Protect Animals against Tuberculosis Challenge. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2006, 13, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| KEGG Pathway | Gene name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity (mmu04650) |

Cd247 | Cd48 | Fasl | Fcgr4 | Gzmb | H2-Q10 | H2-Q6 | H2-Q7 |

| H2-Q9 | H2-T-ps | Hcst | Ifng | Itgal | Itgb2 | Klra1 | Klra4 | |

| Klra7 | Klra8 | Klrb1c | Klrc1 | Klrc2 | Klrd1 | Klrk1 | Lat | |

| Lck | Lcp2 | Nfatc2 | Prf1 | Prkcb | Sh2d1a | Tnf | Zap70 | |

| T cell receptor signaling pathway (mmu04660) |

Cd247 | Cd28 | Cd3d | Cd3e | Cd3g | Cd40l | Cd8a | Cd8b1 |

| Ctla4 | Grap2 | Icos | Ifng | Itk | Lat | Lck | Lcp2 | |

| Mapk10 | Nfatc2 | Pdcd1 | Prkcq | Ptprc | Tnf | Zap70 | ||

| Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation (mmu04658) |

Cd247 | Cd3d | Cd3e | Cd3g | Ifng | Il12b | Il12rb1 | Il12rb2 |

| Il2rb | Lat | Lck | Mapk10 | Nfatc2 | Prkcq | Runx3 | Stat4 | |

| Tbx21 | Zap70 | |||||||

| Th17 cell Differentiation (mmu04659) |

Cd247 | Cd3d | Cd3e | Cd3g | Ifng | Il12rb1 | Il21r | Il27ra |

| Il2rb | Lat | Lck | Mapk10 | Nfatc2 | Prkcq | Tbx21 | Zap70 | |

| Chemokine signaling pathway (mmu04062) |

Ccl3 | Ccl4 | Ccl5 | Ccr2 | Ccr5 | Ccr9 | Cx3cr1 | Cxcl10 |

| Cxcl9 | Cxcr3 | Cxcr6 | Dock2 | Itk | Pik3cg | Pik3r5 | Ppbp | |

| Prkcb | Rac2 | Was | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).