Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

ecent interest in breath methane has demonstrated considerable growth, with a 400% increase in publications per year between 2010 and 2020 compared to the previous decade. This surge has been facilitated by advancements in measurement techniques that have improved both the precision and ease of breath methane analysis. Consequently, there has been a growing appreciation for both the routes of production as well as the physiological effects of methane within the human body, shifting from a perspective of methane as an end-product of GI microbiota to viewing it as a potentially biologically active molecule with exciting potential implications for endogenous processes. The breath methane field stands at a pivotal juncture, where new technologies enable real-time, repeated measures of breath methane for the first time, paving the way for novel insights into personalized methane levels and their interplay with health. This review explores the origins, physiological effects, and measurement techniques of breath methane, highlighting potential pathways for future research.

Keywords:

Introduction

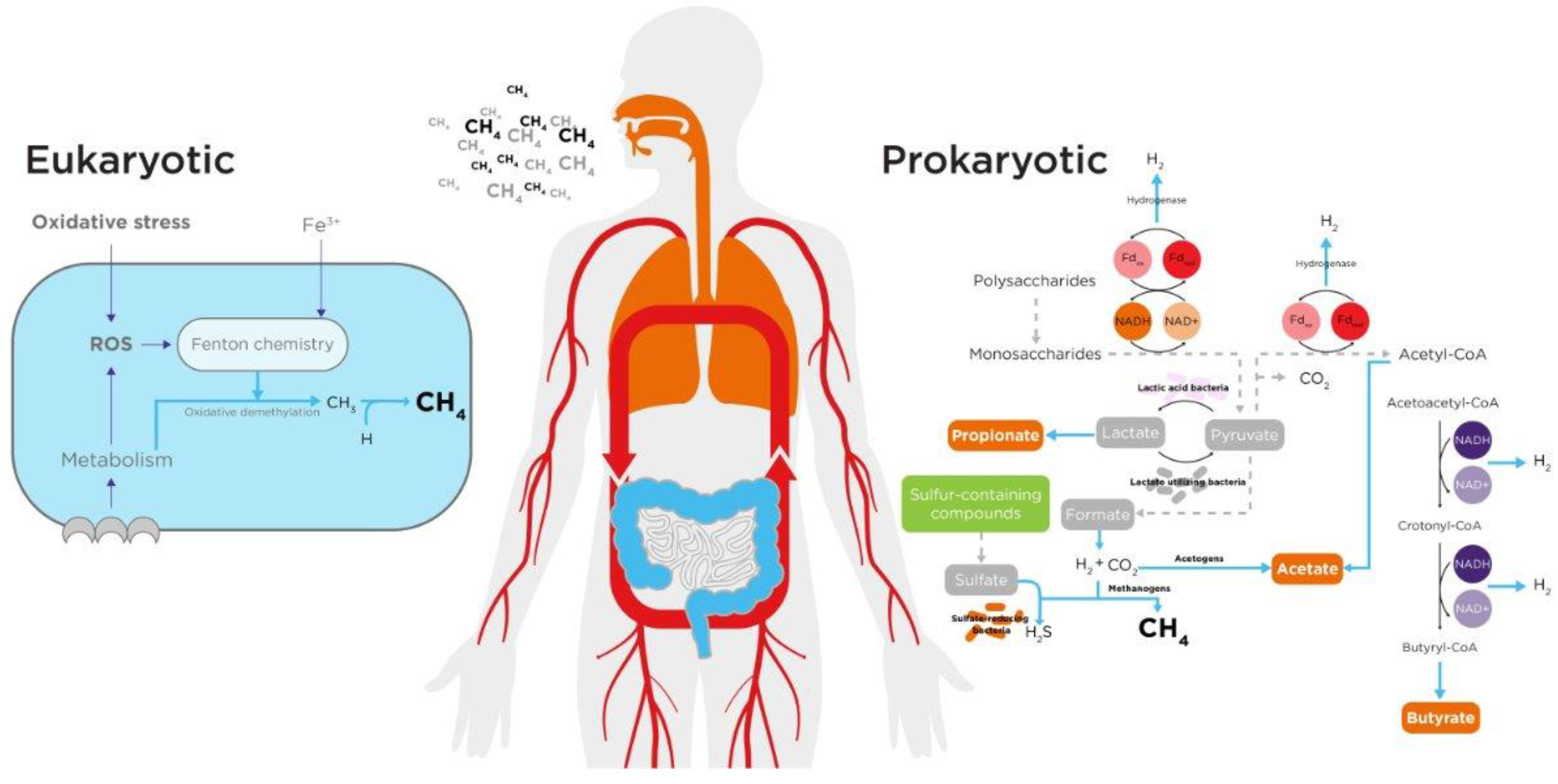

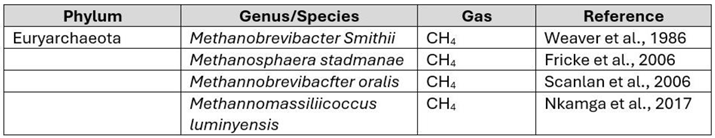

Gut Microbiome

Human Endogenous Processes

Detection and Measurement of Methane in Breath

Breath Sampling and Analytical Techniques

Potential Effects of Methane

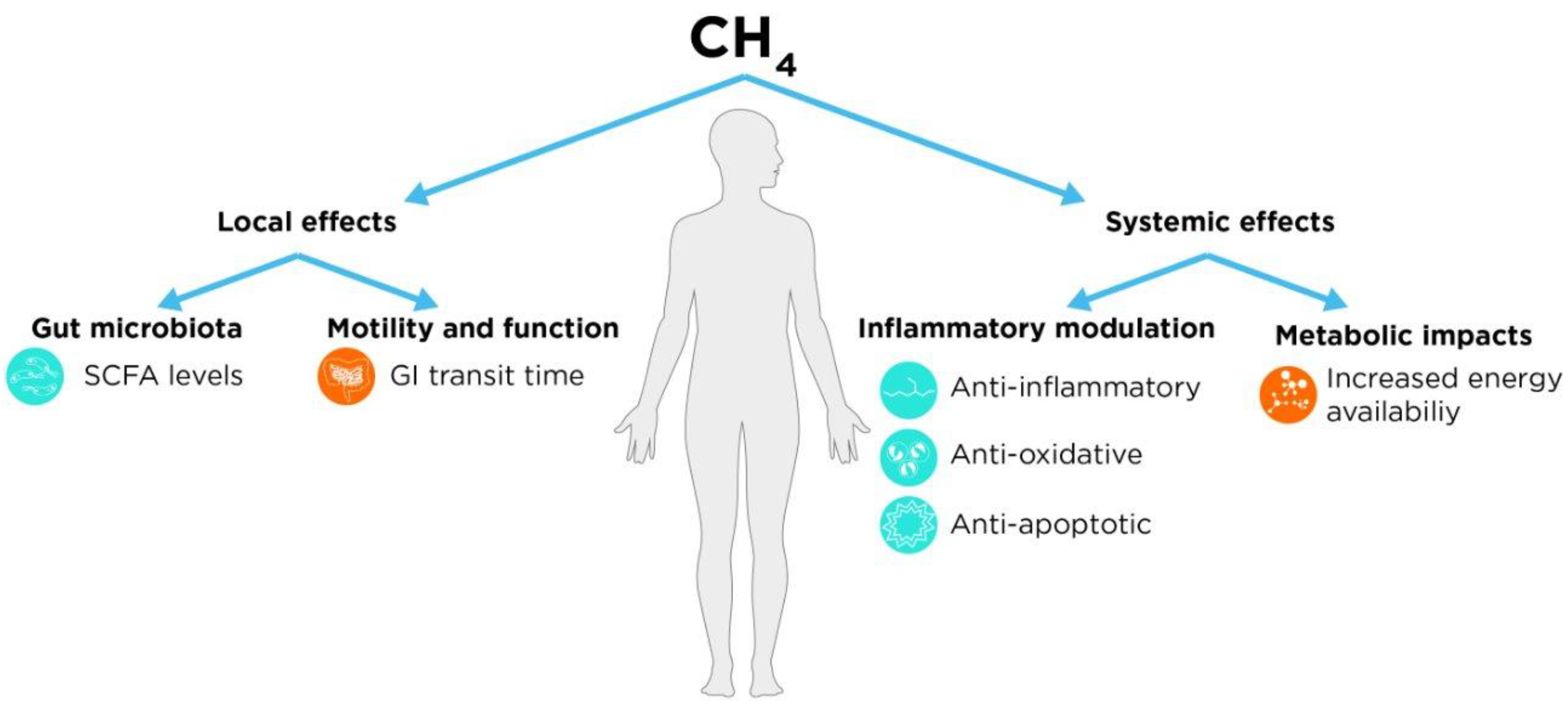

Local (GI) Effects

Motility and Function

Interaction with Gut Microbiota

Systemic Effects

Inflammatory Modulation

- Anti-inflammatory effects, that manifest as reductions in TNFα, IL-6, and IL-1B levels following intraperitoneal (IP) dosing of methane-rich saline (MRS). These effects appear to be mediated via IL-10, and upstream through the PI3K-AKT-GSK-3B pathway56–66.

- Anti-oxidative effects, presenting as reductions in MDA or 8-OHdG levels, as well as the prevention of loss of antioxidant activity (SOD/CAT levels)58–65,67–70.

- Anti-apoptotic effects, manifesting as reductions in TUNEL staining, as well as reduced caspase 3/9 activation59–63,67,68,71.

Metabolic Impacts

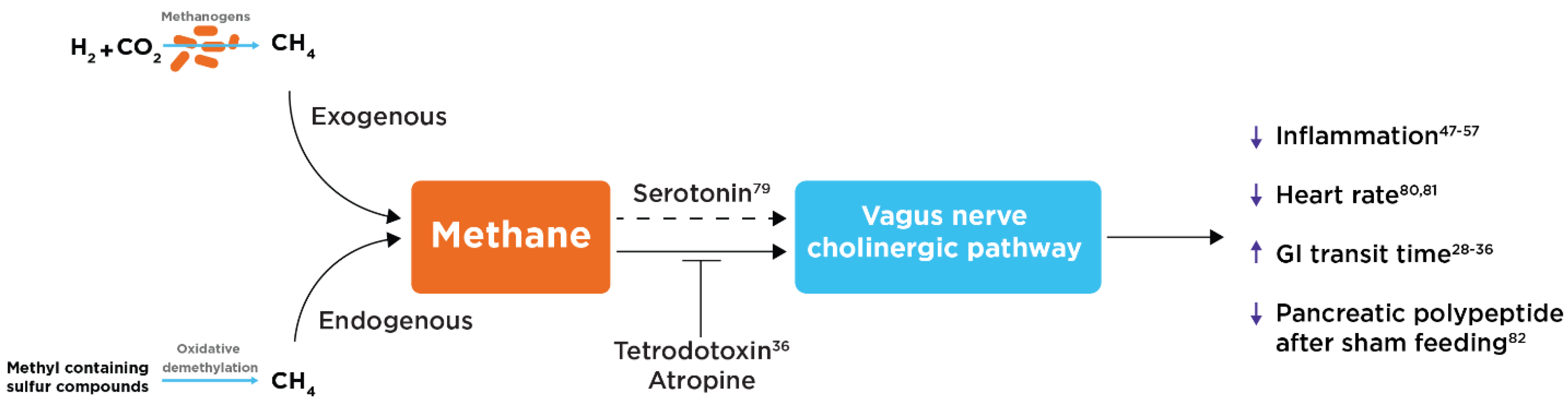

Potential Role of the Vagus Nerve and Cholinergic Pathway

Clinical Implications and Future Research

Conclusion

Declaration of Interests

References

- Cummings, J.H.; Pomare, E.W.; Branch, W.J.; Naylor, C.P.; Macfarlane, G.T. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 1987, 28, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, E.N. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol. Rev. 1990, 70, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, G.T. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, F.L.; Springfield, J.; Levitt, M.D. Identification of gases responsible for the odour of human flatus and evaluation of a device purported to reduce this odour. Gut 1998, 43, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mego, M.; Accarino, A.; Malagelada, J.; Guarner, F.; Azpiroz, F. Accumulative effect of food residues on intestinal gas production. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 27, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J.; Azpiroz, F.; Malagelada, J. Intestinal gas dynamics and tolerance in humans. Gastroenterology 1998, 115, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, F.L.; Levitt, M.D. An understanding of excessive intestinal gas. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2000, 2, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arulvasan, W.; Chou, H.; Greenwood, J.; Ball, M.L.; Birch, O.; Coplowe, S.; Gordon, P.; Ratiu, A.; Lam, E.; Hatch, A.; et al. High-quality identification of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) originating from breath. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.; González, S.; Nogacka, A.M.; Rios-Covián, D.; Arboleya, S.; Gueimonde, M.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. Microbiome: Effects of Ageing and Diet. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2020, 36, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Weaver, G.; A Krause, J.; Miller, T.L.; Wolin, M.J. Incidence of methanogenic bacteria in a sigmoidoscopy population: an association of methanogenic bacteria and diverticulosis. Gut 1986, 27, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, W.F.; Seedorf, H.; Henne, A.; Krüer, M.; Liesegang, H.; Hedderich, R.; Gottschalk, G.; Thauer, R.K. The Genome Sequence of Methanosphaera stadtmanae Reveals Why This Human Intestinal Archaeon Is Restricted to Methanol and H 2 for Methane Formation and ATP Synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkamga, V.D.; Henrissat, B.; Drancourt, M. Archaea: Essential inhabitants of the human digestive microbiota. Hum. Microbiome J. 2016, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpitsch, C.; Fischmeister, F.P.S.; Mahnert, A.; Lackner, S.; Wilding, M.; Sturm, C.; Springer, A.; Madl, T.; Holasek, S.; Högenauer, C.; et al. Reduced B12 uptake and increased gastrointestinal formate are associated with archaeome-mediated breath methane emission in humans. Microbiome 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, A.; Levinthal, D.J. UNDERSTANDING OUR TESTS: HYDROGEN-METHANE BREATH TESTING TO DIAGNOSE SMALL INTESTINAL BACTERIAL OVERGROWTH. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, T.H.; Zhu, G.; Kirk, K.M.; Martin, N.G. Shared and unique environmental factors determine the ecology of methanogens in humans and rats. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 2872–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christl, S.U.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Gibson, G.R.; Cummings, J.H. Production, metabolism, and excretion of hydrogen in the large intestine. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, J.; Kataria, R.; Malik, Z.; Parkman, H.P.; Schey, R. Elevated methane levels in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth suggests delayed small bowel and colonic transit. Medicine 2018, 97, e10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, W.; Pimentel, M.; Rao, S.; Villanueva-Millan, M.J.; Chang, C.; Morales, W.; Sanchez, M.; Torosyan, J.; Rashid, M.; Hosseini, A.; et al. A Single Fasting Exhaled Methane Level Correlates With Fecal Methanogen Load, Clinical Symptoms and Accurately Detects Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, J. Understanding the Results from Methane Breath CH4ECKTM Test. The Functional Gut Clinic https://thefunctionalgutclinic.com/blog/education/understanding-the-results-from-your-methane-breath-ch4eck-test/ (2021).

- Avvisati, R.; Bates, J.; Winter, H.; Ball, M.; Pocock, L.; Davies, H.; Pinto-Lopes, R.; Guagliardo, F.; Nash, M.; Scott, P.; et al. S2217 Development and Validation of a Portable Device for At-Home Hydrogen and Methane Breath Testing. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, S1584–S1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.A.; Chadwick, V.S.; Murray, A. Carriage, quantification, and predominance of methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria in faecal samples. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 43, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.B.; Balamurugan, R.; Ramakrishna, B.S. Molecular analysis of the human faecal archaea in a southern Indian population. J. Biosci. 2017, 42, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dridi, B.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Archaea as emerging organisms in complex human microbiomes. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghyczy, M.; Torday, C.; Boros, M. Simultaneous generation of methane, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide from choline and ascorbic acid: a defensive mechanism against reductive stress? FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2003, 17, 1124–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghyczy, M.; Torday, C.; Kaszaki, J.; Szabó, A.; Czóbel, M.; Boros, M. Hypoxia-Induced Generation of Methane in Mitochondria and Eukaryotic Cells - An Alternative Approach to Methanogenesis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 21, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.K.; DiMaio, V.J.M. Normal organ weights in men: part II-the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2012, 33, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B.; et al. The Mitochondrion. in Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition (Garland Science, 2002).

- Szabó, A.; Unterkofler, K.; Mochalski, P.; Jandacka, M.; Ruzsanyi, V.; Szabó, G.; Mohácsi. ; Teschl, S.; Teschl, G.; King, J. Modeling of breath methane concentration profiles during exercise on an ergometer. J. Breath Res. 2016, 10, 017105–017105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczuk, G.; Humeniuk, E.; Adamczuk, K.; Grabarska, A.; Dudka, J. 2,4-Dinitrophenol as an Uncoupler Augments the Anthracyclines Toxicity against Prostate Cancer Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishkerman, A.; Greiner, S.; Ghyczy, M.; Boros, M.; Rausch, T.; Lenhart, K.; Keppler, F. Enhanced formation of methane in plant cell cultures by inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010, 34, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuboly, E.; Szabó, A.; Garab, D.; Bartha, G.; Janovszky. ; Ero″S, G.; Szabó, A.; Mohácsi,.; Szabó, G.; Kaszaki, J.; et al. Methane biogenesis during sodium azide-induced chemical hypoxia in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2013, 304, C207–C214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, F.; Hamilton, J.T.G.; Braß, M.; Röckmann, T. Methane emissions from terrestrial plants under aerobic conditions. Nature 2006, 439, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, F.; Boros, M.; Polag, D. Radical-Driven Methane Formation in Humans Evidenced by Exogenous Isotope-Labeled DMSO and Methionine. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuboly, E.; Szabó, A.; Erős, G.; Mohácsi. ; Szabó, G.; Tengölics, R.; Rákhely, G.; Boros, M. Determination of endogenous methane formation by photoacoustic spectroscopy. J. Breath Res. 2013, 7, 046004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polag, D.; Keppler, F. COVID19-vaccination affects breath methane dynamics. 2022.07.27.501717 Preprint at. [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.; Godbeer, L.; Allsworth, M.; Boyle, B.; Ball, M.L. Progress and challenges of developing volatile metabolites from exhaled breath as a biomarker platform. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Lin, H.C.; Enayati, P.; Burg, B.v.D.; Lee, H.-R.; Chen, J.H.; Park, S.; Kong, Y.; Conklin, J. Methane, a gas produced by enteric bacteria, slows intestinal transit and augments small intestinal contractile activity. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, G1089–G1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, J.; Jung, I.S.; Choi, E.J.; Conklin, J.L.; Park, H. The effects of methane and hydrogen gases produced by enteric bacteria on ileal motility and colonic transit time. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 24, 185–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, L.; Low, K.; Khoshini, R.; Melmed, G.; Sahakian, A.; Makhani, M.; Pokkunuri, V.; Pimentel, M. Evaluating Breath Methane as a Diagnostic Test for Constipation-Predominant IBS. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 55, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaluri, A.; Jackson, M.; Valestin, J.; Rao, S.S. Methanogenic Flora Is Associated With Altered Colonic Transit but Not Stool Characteristics in Constipation Without IBS. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, D.; Basseri, R.J.; Makhani, M.D.; Chong, K.; Chang, C.; Pimentel, M. Methane on Breath Testing Is Associated with Constipation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 1612–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Park, S.; Low, K.; Kong, Y.; Pimentel, M. The Degree of Breath Methane Production in IBS Correlates With the Severity of Constipation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Oufir, L.; Flourie, B.; Varannes, S.B.D.; Barry, J.L.; Cloarec, D.; Bornet, F.; Galmiche, J.P. Relations between transit time, fermentation products, and hydrogen consuming flora in healthy humans. Gut 1996, 38, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.C.F.; Lederman, H.M.; Fagundes-Neto, U.; de Morais, M.B. Breath Methane Associated With Slow Colonic Transit Time in Children With Chronic Constipation. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2005, 39, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.M.; Hussain, Z.; Lee, Y.H.; Park, H. The effects and mechanism of action of methane on ileal motor function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruaud, A.; Esquivel-Elizondo, S.; de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Waters, J.L.; Angenent, L.T.; Youngblut, N.D.; Ley, R.E. Syntrophy via Interspecies H 2 Transfer between Christensenella and Methanobrevibacter Underlies Their Global Cooccurrence in the Human Gut. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høverstad, T.; Fausa, O.; Bjørneklett, A.; Bøhmer, T. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Normal Human Feces. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1984, 19, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Wolever, T.M.; Rao, A.V. Increased Serum Cholesterol in Healthy Human Methane Producers Is Confounded by Age. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.; Rao, A.V.; Wolever, T.M.S. Different Substrates and Methane Producing Status Affect Short-Chain Fatty Acid Profiles Produced by In Vitro Fermentation of Human Feces. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1932–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, T.M.S.; A Robb, P.; ter Wal, P.; Spadafora, P.G. Interaction between Methane-Producing Status and Diet on Serum Acetate Concentration in Humans. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; et al. Age, Dietary Fiber, Breath Methane, and Fecal Short Chain Fatty Acids Are Interrelated in Archaea-Positive Humans1–3. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polag, D.; Leiß, O.; Keppler, F. Age dependent breath methane in the German population. Sci. Total. Environ. 2014, 481, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yi, Y.; Yan, R.; Hu, R.; Sun, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, H.; Si, X.; Ye, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Impact of age-related gut microbiota dysbiosis and reduced short-chain fatty acids on the autonomic nervous system and atrial fibrillation in rats. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1394929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.; Gdanetz, K.; Schmidt, A.W.; Schmidt, T.M. H2 generated by fermentation in the human gut microbiome influences metabolism and competitive fitness of gut butyrate producers. Microbiome 2023, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, B.S.; Gordon, J.I. A humanized gnotobiotic mouse model of host–archaeal–bacterial mutualism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10011–10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jia, Y.; Feng, Y.; Cui, R.; Miao, R.; Zhang, X.; Qu, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Methane alleviates sepsis-induced injury by inhibiting pyroptosis and apoptosis: in vivo and in vitro experiments. Aging 2019, 11, 1226–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; et al. Methane limit LPS-induced NF-κB/MAPKs signal in macrophages and suppress immune response in mice by enhancing PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β-mediated IL-10 expression. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Fei, M.; Bao, S.; Meng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Deng, X. Methane-rich saline protects against concanavalin A-induced autoimmune hepatitis in mice through anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 470, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Chen, O.; Zhang, R.; Nakao, A.; Fan, D.; Zhang, T.; Gu, Z.; Tao, H.; Sun, X. Methane Attenuates Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rats Through Antiapoptotic, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antioxidative Actions. Shock 2015, 44, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protective Effects of Methane-Rich Saline on Rats with Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury - PMC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5434237/.

- Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Sun, A.; Yu, J.; Xie, N.; Xi, Y.; Ye, X. Methane Suppresses Microglial Activation Related to Oxidative, Inflammatory, and Apoptotic Injury during Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 2190897–2190897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Fan, D.; Zang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, K.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Gong, J. Neuroprotective effects of methane-rich saline on experimental acute carbon monoxide toxicity. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 369, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yao, Y.; He, R.; Meng, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, O.; Cui, J.; Bian, J.; et al. Methane ameliorates spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats: Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activity mediated by Nrf2 activation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 103, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Sun, X.; Lou, S. Effects of Methane-Rich Saline on the Capability of One-Time Exhaustive Exercise in Male SD Rats. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Fei, M.; Fa, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, X. Methane-rich saline alleviates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis by inhibiting inflammatory response, oxidative stress and pancreatic apoptosis in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 51, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protective effects of methane-rich saline on diabetic retinopathy via anti-inflammation in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26363454/.

- Liu, L.; Sun, Q.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Xia, F.; Fan, X.-Q. Methane attenuates retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury via anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic pathways. Brain Res. 2016, 1646, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, O.; Ye, Z.; Cao, Z.; Manaenko, A.; Ning, K.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Methane attenuates myocardial ischemia injury in rats through anti-oxidative, anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory actions. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 90, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, M.M.; Ghyczy, M.; Érces, D.; Varga, G.; Tőkés, T.; Kupai, K.; Torday, C.; Kaszaki, J. The anti-inflammatory effects of methane*. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Sun, Q.; Xia, F.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, L. Methane rescues retinal ganglion cells and limits retinal mitochondrial dysfunction following optic nerve crush. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 159, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Zhang, M.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X. Methane-rich saline attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury of abdominal skin flaps in rats via regulating apoptosis level. BMC Surg. 2015, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; et al. Methane-Rich Saline Ameliorates Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury through Anti-Inflammation, Antioxidative, and Antiapoptosis Effects by Regulating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4756846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Wang, W.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ye, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, C. Protective Effects of Methane-Rich Saline on Rats with Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7430193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An Obesity-Associated Gut Microbiome with Increased Capacity for Energy Harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I, M.N. The contribution of the large intestine to energy supplies in man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 39, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basseri, R.J.; Basseri, B.; Pimentel, M.; Chong, K.; Youdim, A.; Low, K.; Hwang, L.; Soffer, E.; Chang, C.; Mathur, R. Intestinal methane production in obese individuals is associated with a higher body mass index. . 2012, 8, 22–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murga-Garrido, S.M.; Orbe-Orihuela, Y.C.; Díaz-Benítez, C.E.; Castañeda-Márquez, A.C.; Cornejo-Granados, F.; Ochoa-Leyva, A.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Cruz, M.; Burguete-García, A.I.; Lagunas-Martínez, A. Alterations of the Gut Microbiome Associated to Methane Metabolism in Mexican Children with Obesity. Children 2022, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, S.; Cho, E.-Y.; Yang, H.; Hwang, J.; Shin, K.; Jung, S.; Kim, B.-T.; Kim, K.-N.; Lee, W. Methane gas in breath test is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Breath Res. 2024, 18, 046005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Amichai, M.; Chua, K.S.; Mirocha, J.; Barlow, G.M.; Pimentel, M. Methane and Hydrogen Positivity on Breath Test Is Associated With Greater Body Mass Index and Body Fat. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E698–E702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozato, N.; Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Katashima, M.; Tokuda, I.; Sawada, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Kakuta, M.; Imoto, S.; Ihara, K.; et al. Association between breath methane concentration and visceral fat area: a population-based cross-sectional study. J. Breath Res. 2020, 14, 026008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, C.H.; Olesen, S.S.; Materna, A.; Drewes, A.M. Breath methane concentrations and markers of obesity in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Goyal, D.; Kim, G.; Barlow, G.M.; Chua, K.S.; Pimentel, M. Methane-producing human subjects have higher serum glucose levels during oral glucose challenge than non-methane producers: a pilot study of the effects of enteric methanogens on glycemic regulation. Res. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Chua, K.S.; Mamelak, M.; Morales, W.; Barlow, G.M.; Thomas, R.; Stefanovski, D.; Weitsman, S.; Marsh, Z.; Bergman, R.N.; et al. Metabolic effects of eradicating breath methane using antibiotics in prediabetic subjects with obesity. Obesity 2016, 24, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Mundi, M.S.; Chua, K.S.; Lorentz, P.A.; Barlow, G.M.; Lin, E.; Burch, M.; Youdim, A.; Pimentel, M. Intestinal methane production is associated with decreased weight loss following bariatric surgery. Obes. Res. Clin. Pr. 2016, 10, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Tremaroli, V.; Schmidt, C.; Lundqvist, A.; Olsson, L.M.; Krämer, M.; Gummesson, A.; Perkins, R.; Bergström, G.; Bäckhed, F. The Gut Microbiota in Prediabetes and Diabetes: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverdure, R.; Mezouari, A.; Carson, M.A.; Basiliko, N.; Gagnon, J. A role for methanogens and methane in the regulation of GLP-1. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 1, e00006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, B. J. & Bordoni, B. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 10 (Vagus Nerve). in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2024).

- Pimentel, M.; Kong, Y.; Park, S. IBS Subjects with Methane on Lactulose Breath Test Have Lower Postprandial Serotonin Levels Than Subjects with Hydrogen. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004, 49, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakura, W.; Chang, C.; Pimentel, M.; Mo, G.; Torosyan, J.; Hosseini, A.; Wang, J.; Kowaleski, E.; Mathur, R.; Chang, B.; et al. Exhaled Methane Is Associated with a Lower Heart Rate. Cardiology 2021, 147, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, W.; Chang, C.; Hosseini, A.; Wang, J.; Kowalewski, E.; Mathur, R.; Rezaie, A.; Pimentel, M. S0462 The Vital Gut Microbe: The Effect of Methane on the Host's Vital Sign. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, S232–S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakura, W.; Pimentel, M.; Mathur, R.; Rezaie, A. S500 Presence of Methane in the Fasting Breath Is Associated With a Lower Rise in Pancreatic Polypeptide After Modified Sham-Feeding: An Insight into the Connection Between Vagal Dysfunction and Methane. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, S224–S224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

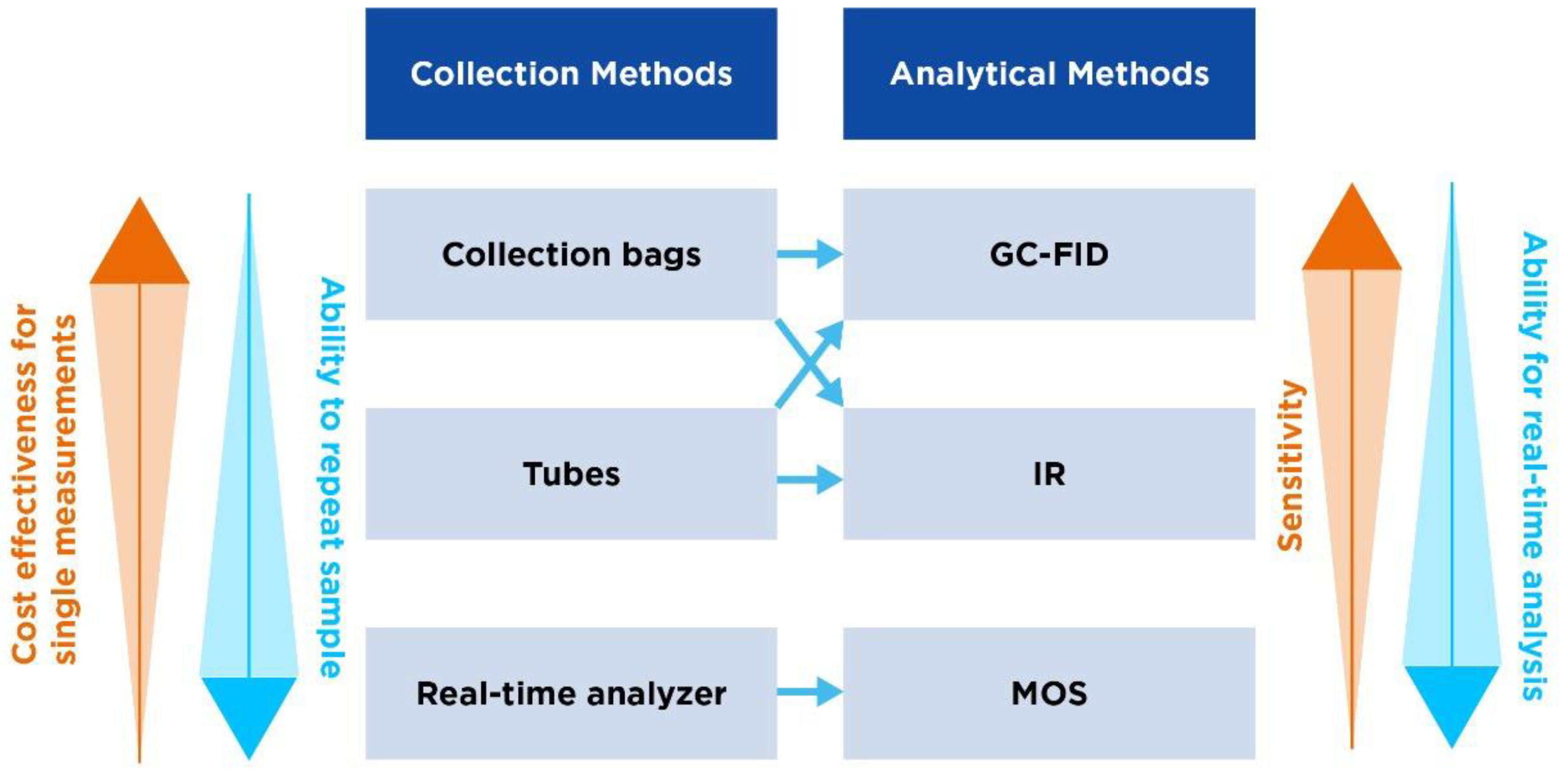

| Collection bags | Tubes | Handheld real-time analyzer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | One of the most common methods used, where patients exhale directly into a bag. | Uses tubes through which the patient exhales. Tubes are then sealed awaiting analysis. | Involves the use of portable devices that analyze breath in real-time with no need for separate sample collection/storage |

| Different forms | Mylar bags (made from a type of polyester film impermeable to gases) or Tedlar bags (made from PVF). | Vacuum tubes (draw in the breath sample automatically) or glass/plastic tubes. | The OMED device. |

| Procedure | Patients take a deep breath and exhale completely into the bag. The bag is subsequently sealed for later analysis. | The patient exhales through a mouthpiece connected to the tube, which is then sealed after collection. | Patient breathes directly into the analyzer through a mouthpiece. Gas concentrations are fed back in real-time. |

| Advantages | Simple and cost-effective. | Easy to use and transport. | Provides instant results and allows for simple repeat measures. |

| Considerations | Bags can be challenging to handle post-collection and can lead to sample contamination/loss. | Tubes may require specific storage to prevent sample degradation. | Device calibration is crucial for accurate readings. |

| GC-FID | IR | MOS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | GC-FID combines GC for separation of components of a breath sample and flame ionization detection for methane quantification. | IR measures the absorption of IR light by methane to determine its concentration. | MOS detect gases based on changes in electrical resistances of a metal oxide sensor when it interacts with methane. |

| Advantages | High sensitivity, high specificity and quantitative analysis. | Real-time analysis and easier than GC-FID. | Cost-effective, durable and provides real-time analyses. |

| Limitations | Complexity and cost, requiring sophisticated equipment and trained personnel. Time-consuming, requiring lab prep. | Unlikely to reach the level of GC-FID for low concentrations. Subject to interference from other gases/water vapor if not properly calibrated. | Unlikely to reach the level of GC-FID for low concentrations. Requires appropriate calibration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).