Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

3. Clinical Presentations

3.1. Lesion Characteristics

3.2. Common Sites (Table 1)

- Genital Area: The genital area has a lower rate of misdiagnosis, possibly due to more thorough evaluations being conducted because of the anatomical sensitivity. Lesions in this region typically prompt careful examination, which aids in correct identification [29].

4. Diagnostic Challenges (Table 2)

4.1. Misdiagnosis

- Vascular Lesions: DFSP often presents with a reddish or purplish hue, which can easily lead clinicians to suspect vascular anomalies, such as hemangiomas or vascular malformations [30,31]. These benign conditions are common in infants, and DFSP’s similar coloration and presentation can result in inappropriate initial management or conservative follow-up, which delays proper treatment [32].

- Benign Proliferative Lesions: Conditions like hypertrophic scars, keloids, and fibromas are also frequently considered due to their appearance and benign nature [11,20,21]. These lesions are often characterized by localized skin thickening or growth, which may closely resemble DFSP, particularly in its plaque or nodular form. Misclassification as a benign proliferative lesion can lead to an underestimation of the potential seriousness of the condition, delaying the necessary surgical intervention [11,20,21,24].

- Dermatofibromas and Birthmarks: Dermatofibromas are common benign fibrous lesions of the skin, and congenital DFSP may present in a similar manner, with slow-growing plaques or nodules. Birthmarks present from birth can also confuse the diagnosis, particularly when the lesions are not rapidly changing [33]. DFSP lesions present at birth are often assumed to be benign congenital nevi or vascular birthmarks, leading to diagnostic errors [5,33].

4.2. Factors Contributing to Misdiagnosis

4.3. Importance of Early Diagnosis

- Increased Tumor Size: Due to its indolent but steady growth, congenital DFSP that is not recognized early can grow significantly in size before proper treatment is initiated. As the lesion increases in size, it becomes more complex to treat, often involving deeper invasion into underlying tissues, including muscle and sometimes even bone [7,8].

- More Extensive Surgery: Early diagnosis allows for a more conservative approach to surgical excision. However, as the lesion grows larger, wider excision becomes necessary to ensure complete removal and prevent recurrence. The larger the surgical excision, the more tissue must be sacrificed, which can lead to greater functional limitations, increased morbidity, and a more noticeable cosmetic defect [7,8,9].

- Higher Risk of Recurrence: DFSP is locally aggressive, with a high tendency to recur if not entirely removed. The risk of recurrence is increased significantly if initial surgical excision is incomplete, which can occur more frequently when the diagnosis is delayed. Early, precise surgical management, particularly using techniques like Mohs micrographic surgery, is key to minimizing recurrence [7,8,10].

- Psychological Impact: The need for larger surgeries and the potential for recurrence have significant psychological consequences, particularly in pediatric patients. Visible scars and potential disfigurement can have a lasting impact on a child’s self-esteem and quality of life. This highlights the importance of early, precise intervention that minimizes scarring and preserves as much healthy tissue as possible [16].

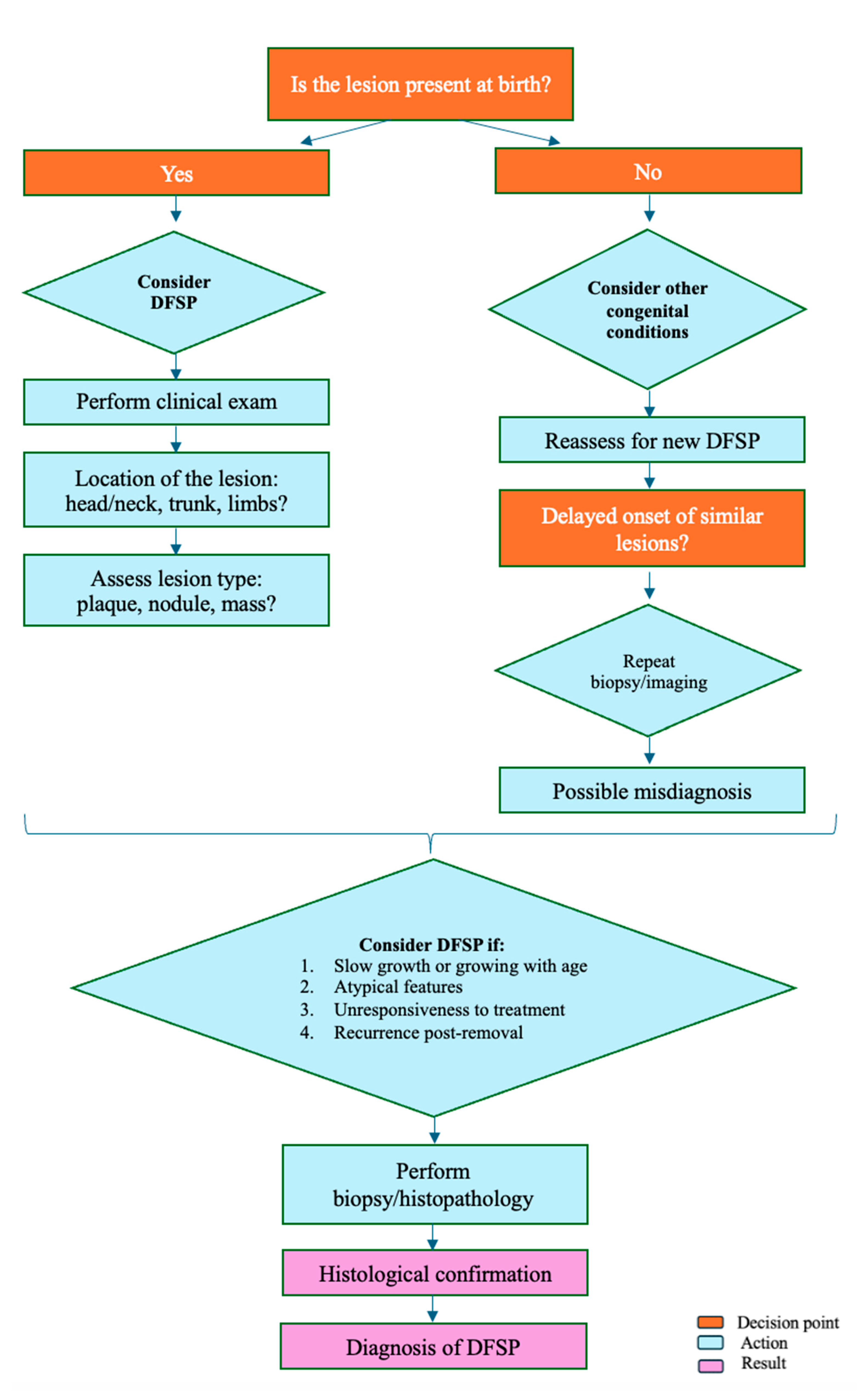

5. Diagnostic Approach (Figure 1)

- 20)Clinical Evaluation: The diagnostic approach to congenital DFSP begins with a thorough clinical evaluation. A high index of suspicion is paramount, particularly when clinicians encounter congenital skin lesions that exhibit atypical features or fail to respond to conventional treatments. Congenital DFSP often mimics benign lesions, such as hemangiomas or dermatofibromas, making a cautious and investigative approach essential [30,31,33]. Clinicians should be alert to slow-growing, firm plaques or nodules, especially those that do not resolve or behave atypically over time [6,36]. A detailed patient history and examination are also critical components of clinical evaluation [11]. Assessing the growth rate, characteristics of the lesion (e.g., color, firmness, location), and noting any changes over time can help differentiate DFSP from more common benign conditions. The presence of a lesion at birth that slowly grows, remains persistent, or becomes more irregular should prompt further investigation [3,9,34].

- Biopsy and Histopathology: An early biopsy is recommended for any congenital lesion that appears atypical or shows no response to initial treatments. A biopsy provides definitive information regarding the nature of the lesion [7]. Histopathologically, DFSP is characterized by spindle-shaped cells arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern, an important distinguishing feature [12]. Immunohistochemistry is also valuable; DFSP usually shows strong CD34 positivity, which serves as a useful diagnostic marker to differentiate it from other skin conditions [12]. Additionally, molecular testing can be instrumental in confirming a DFSP diagnosis. The detection of the COL1A1-PDGFB fusion gene—resulting from a characteristic chromosomal translocation—confirms the diagnosis and can aid in planning targeted therapy in advanced cases [12,13].

- Imaging Studies: For a comprehensive assessment of the lesion, imaging studies like MRI and CT scans may be utilized, particularly when the lesion involves complex anatomical areas or deeper tissue layers. MRI provides detailed images that can help evaluate the extent of soft tissue involvement, while CT scans can be useful in assessing the depth of invasion and involvement of surrounding structures. These imaging modalities are essential for surgical planning, especially in cases where the lesion is extensive or involves critical areas such as the head, neck, or extremities. Imaging helps delineate the tumor margins, providing crucial information that guides the extent of surgical excision needed to achieve negative margins and minimize recurrence risk [7,15].

6. Treatment

6.1. Surgical Management

6.2. Adjuvant Therapies

6.3. Multidisciplinary Approach

6.4. Prognosis and Follow-Up

7. Recommendations for Clinicians

- Maintain Vigilance:

- Early Intervention:

- Patient Education:

- Optimize Surgical Outcomes:

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whittle C, Andrews A, Coulon G, Castro A. Different sonographic presentations of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Ultrasound. 2024;27(1):61-65. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen R, Tang Z, Liu S. A Rare Malignant Disease, Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans of the Breast: A Retrospective Analysis and Review of Literature. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8852182. Published 2020 Nov 9. [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2503-2508. [CrossRef]

- Rubio GA, Alvarado A, Gerth DJ, Tashiro J, Thaller SR. Incidence and Outcomes of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans in the US Pediatric Population. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(1):182-184. [CrossRef]

- Dehner LP, Gru AA. Nonepithelial Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of the Skin and Subcutis in Children. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21(2):150-207. [CrossRef]

- Han HH, Lim SY, Park YM, Rhie JW. Congenital Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: A Case Report and Literature Review. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27(5):597-600. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Fort MK, Meier-Schiesser B, Niaz MJ, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: The Current State of Multidisciplinary Management. Skinmed. 2020;18(5):288-293. Published 2020 Oct 1.

- Rust DJ, Kwinta BD, Geskin LJ, Samie FH, Remotti F, Yoon SS. Surgical management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Surg Oncol. 2023;128(1):87-96. [CrossRef]

- Lindner NJ, Scarborough MT, Powell GJ, Spanier S, Enneking WF. Revision surgery in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the trunk and extremities. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25(4):392-397. [CrossRef]

- Loghdey MS, Varma S, Rajpara SM, Al-Rawi H, Perks G, Perkins W. Mohs micrographic surgery for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP): a single-centre series of 76 patients treated by frozen-section Mohs micrographic surgery with a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(10):1315-1321. [CrossRef]

- Cheon M, Jung KE, Kim HS, et al. Medallion-like dermal dendrocyte hamartoma: differential diagnosis with congenital atrophic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(3):382-384. [CrossRef]

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: Update on the Diagnosis and Treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1752. Published 2020 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Yang JH, Hu WH, Li F, et al. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2003;32(5):409-412.

- Marcoval J, Moreno-Vílchez C, Torrecilla-Vall-Llosera C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: A Study of 148 Patients. Dermatology. 2024;240(3):487-493. [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba B, Wang F, Taher A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: Pathological and Imaging Review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021;50(2):236-240. [CrossRef]

- Gurevitch D, Kirschenbaum SE. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Salvaging quality of life using two approaches to treatment. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1996;86(9):439-446. [CrossRef]

- Penel N, El Bedoui S, Robin YM, Decanter G. Dermatofibrosarcome : prise en charge [Dermatofibrosarcoma: Management]. Bull Cancer. 2018;105(11):1094-1101. [CrossRef]

- Kreicher KL, Kurlander DE, Gittleman HR, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Bordeaux JS. Incidence and Survival of Primary Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans in the United States. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42 Suppl 1:S24-S31. [CrossRef]

- Kim JW, Kim JE, Song HJ, Oh CH. Congenital Bednar’s tumour. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(5):e85-e87. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein JM, Drolet BA, Esterly NB, et al. Congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: variability in presentation. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(2):207-211. [CrossRef]

- Thornton SL, Reid J, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Childhood dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: role of preoperative imaging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1):76-83. [CrossRef]

- Bouaoud J, Fraitag S, Soupre V, et al. Congenital fibroblastic connective tissue nevi: Unusual and misleading presentations in three infantile cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(5):644-650. [CrossRef]

- Jafarian F, McCuaig C, Kokta V, Laberge L, Ben Nejma B. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in childhood and adolescence: report of eight patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(3):317-325. [CrossRef]

- Kutzner H, Mentzel T, Palmedo G, et al. Plaque-like CD34-positive dermal fibroma ("medallion-like dermal dendrocyte hamartoma"): clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 5 cases emphasizing its distinction from superficial, plaque-like dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(2):190-201. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki D, Kobayashi R, Yasuda K, et al. Congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in a newborn infant with a massive back tumor: favorable effects of oral imatinib on the control of residual tumor growth. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(7):e304-e306. [CrossRef]

- Bernárdez C, Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Bednar Tumor Mimicking Congenital Melanocytic Nevus. Tumor de Bednar simulando nevus melanocítico congénito. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(6):523. [CrossRef]

- Karagianni P, Lambropoulos V, Stergidou D, Fryssira H, Chatziioannidis I, Spyridakis I. Recurrent giant cell fibroblastoma: Malignancy predisposition in Kabuki syndrome revisited. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A(5):1333-1338. [CrossRef]

- Tallegas M, Fraitag S, Binet A, et al. Novel KHDRBS1-NTRK3 rearrangement in a congenital pediatric CD34-positive skin tumor: a case report. Virchows Arch. 2019;474(1):111-115. [CrossRef]

- Eisner BH, McAleer SJ, Gargollo PC, Perez-Atayde A, Diamond DA, Elder JS. Pediatric penile tumors of mesenchymal origin. Urology. 2006;68(6):1327-1330. [CrossRef]

- Checketts SR, Hamilton TK, Baughman RD. Congenital and childhood dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(5 Pt 2):907-913. [CrossRef]

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(5):e74-e77. [CrossRef]

- Kunimoto K, Yamamoto Y, Jinnin M. ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies and Molecular Biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2358. Published 2022 Feb 21. [CrossRef]

- Gu W, Ogose A, Kawashima H, et al. Congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous and myxoid change. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(9):984-986. [CrossRef]

- Cabral R, Wilford M, Ramdass MJ. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans associated with trauma: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2020;13(5):51. [CrossRef]

- Reddy C, Hayward P, Thompson P, Kan A. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in children. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(6):819-823. [CrossRef]

- Menon G, Brooks J, Ramsey ML. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; April 18, 2024.

- Henry OS, Platoff R, Cerniglia KS, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors versus radiation therapy in unresectable dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP): A narrative systematic review. Am J Surg. 2023;225(2):268-274. [CrossRef]

- Alshaygy I, Mattei JC, Basile G, et al. Outcome After Surgical Treatment of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans (DFSP): Does it Require Extensive Follow-up and What is an Adequate Resection Margin?. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30(5):3106-3113. [CrossRef]

- Cassalia F, Cavallin F, Danese A, et al. Soft Tissue Sarcoma Mimicking Melanoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jul 12;15(14):3584. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassalia F, Danese A, Cocchi E, et al. Misdiagnosis and Clinical Insights into Acral Amelanotic Melanoma-A Systematic Review. J Pers Med. 2024 May 13;14(5):518. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Farsi A, Al-Brashdi A, Al-Salhi S, et al Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans Mimicking Primary Breast Neoplasm: A case report and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020 Aug;20(3):e368-e371. Epub 2020 Oct 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharif TH, Gronfula A, Alanazi AT, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans of the Scalp Mimicking Trichilemmal Cyst: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 May 21;15(5):e39315. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyama T, Yokoyama M, Matsushima J, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberance with a unique appearance mimicking neurofibroma arising from a conventional area. Int Cancer Conf J. 2024 Jun 15;13(4):382-386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa Y, Furuta J, Kawachi Y. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans mimicking cutaneous sarcoidosis in a patient with lung sarcoidosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;24(2):276-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014 May;53(5):e320-2. Epub 2013 Nov 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyuk E, Saracoğlu ZN, Arık D. Cutaneous Leiomyoma Mimicking a Keloid. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020 Aug;28(2):116. [PubMed]

| Lesion Type | Description | Differential Diagnoses | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plaques | Flat or slightly raised, firm areas | Dermatofibromas, keloids, hypertrophic scars | 11,20,21 |

| Nodules | Firm, well-circumscribed masses | Lipomas, cysts, neurofibromas | 22,23,24 |

| Masses | Larger, more prominent growths | Sarcomas, deep-seated lipomas | 22,23,25 |

| Pigmented Lesions | Darker-colored lesions resembling melanocytic nevi or melanoma | Pigmented nevi, melanoma | 19,26 |

| Category of Misdiagnosis | Reason for Misdiagnosis | Clinical Implications | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Lesions:- Hemangiomas - Vascular Malformations | Similar coloration (reddish, purplish, bluish), common in neonates and infants | Inappropriate initial management. Delayed diagnosis of malignant potential | 30,31 |

| Benign Lesions:- Hypertrophic Scars - Keloids Fibromas | Similar appearance as firm, raised growths, benign nature often leads to underestimation of severity | Assumption of non-malignancy results in delayed treatment and potential lesion growth | 20,21 |

| Dermatofibromas | Slow-growing, firm plaques resembling benign congenital skin lesions | Misinterpretation as a common benign lesion can prevent timely biopsy and histopathological confirmation | 11 |

| Pigmented Lesions | Presence of pigmentation resembling other benign or even malignant pigmented lesions | Delayed accurate diagnosis due to misclassification as benign nevi or melanoma | 19,26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).