Introduction

Primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCL) are a subset of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) characterised by the monoclonal proliferation of malignant lymphocytes within the skin.[

1] Around three-quarters of these cases fall under the category of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL), with mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) being the most common subtypes.[

2]

Classic MF, first detailed by Jean Alibert and Ernest Bazin, typically begins with an early phase marked by scaly, erythematous patches or thin plaques of varying shapes and sizes, often appearing in sun-protected regions. Over time, the disease may evolve into an advanced stage, frequently characterised by the development of tumours.[

3] SS is a rare, aggressive leukemic variant, with differences from MF, of CTCL characterised by erythroderma, lymphadenopathy, and leukemic involvement of the peripheral blood[

4,

5].

They are rare, with an estimated annual incidence of 0.5 to 1 case per 100,000 individuals [

6,

7,

8,

9] and a prevalence of over 6 cases per 100.000 in europe[

10]

(pp1998–2016). The disease predominantly affects adults, with a median age of onset between 55 and 60 years, although cases in younger individuals have been reported with a slight male predominance. Geographically, incidence rates vary, with higher prevalence reported in Western countries compared to Asian populations, possibly due to genetic and environmental factors[

11].

While the exact aetiology remains unclear, potential risk factors for developing CTCLs include chronic antigenic stimulation, persistent immune dysregulation, exposure to infectious agents such as human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and specific genetic susceptibilities. Some reports suggest that exposure to pesticides, industrial solvents, and other environmental toxins may increase the risk, although definitive causal relationships have yet to be established.

Biochemical developments of CTCL are complex, involving specific cytokines that regulate the inflammatory response and vary across different disease stages, influencing its dynamics: specifically, early-stage MF is characterised by a Th1-dominant cytokine profile, involving pro-inflammatory mediators such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-12 which play key roles. These cytokines drive the recruitment of T-cells and macrophages, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage and as the disease progresses, there is a shift toward a Th2 cytokine profile, marked by increased production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [

12,

13]. This change promotes tumour cell survival and suppresses effective immune responses, contributing to the persistence and spread of malignant cells. The interaction between these cytokine profiles drives the inflammatory microenvironment in MF, resulting in cutaneous histopathological alterations that often resemble other dermatoses. Consequently, clinical manifestations such as erythematous patches, plaques, and scaling can be misleading, making differential diagnosis challenging without specific immunohistochemical and molecular studies.

The diagnosis of MF relies on a combination of clinical, histological, and immunophenotypic criteria, given its diverse presentations and overlap with inflammatory and neoplastic conditions⁷. Histological evaluation remains essential for confirming the diagnosis, assessing the disease phase, and classifying MF subtypes, but early-stage MF often mimics a broad spectrum of reactive dermatoses and cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders, making a definitive diagnosis and also therapy challenging⁷[

14]. In the earliest phases, histopathological findings may be subtle and non-specific, leading to delays in diagnosis or misclassification, particularly in patch-stage MF, where differentiation from chronic dermatitis, psoriasis, or parapsoriasis can be difficult⁷.

To improve diagnostic accuracy in early MF, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) has developed a diagnostic algorithm that integrates clinical, histopathological[

15], and immunohistochemical findings, along with T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement studies in cases with equivocal features[

16]. This structured approach aims to enhance diagnostic specificity by incorporating molecular and immunophenotypic parameters, particularly in borderline cases where histological findings alone may be insufficient.

However, while the ISCL algorithm has demonstrated diagnostic utility, several studies have reported its specificity and accuracy limitations, especially in distinguishing early MF from inflammatory mimickers. Overlap in histological patterns, variability in TCR gene rearrangement analysis, and differences in interpretation across pathologists contribute to diagnostic uncertainty. Additionally, the algorithm does not fully account for the dynamic progression of MF, meaning that longitudinal clinical and histological follow-up remains crucial in ambiguous cases.

Given these challenges, non-invasive diagnostic tools, such as dermoscopy, have gained attention as potential adjunctive methods to support early detection and differentiation of MF. By providing real-time visualisation of vascular, pigmentary, and scaling patterns, dermoscopy may offer additional insights into the morphological characteristics of MF lesions, helping to bridge the gap between clinical and histopathological evaluation[

17].

Dermoscopy, a non-invasive diagnostic technique initially developed for assessing pigmented lesions, has expanded its use to various dermatological conditions, including cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders like MF[

18]. By visualising subsurface skin structures, dermoscopy bridges clinical and histopathological evaluations, revealing features like vascular changes and scaling that may help distinguish MF from benign dermatoses. Dermoscopic evaluation is integrated into the standard diagnostic workflow, combining patient history and clinical examination to assess lesion number, distribution, and morphology. As its application broadens, dermoscopy continues to evolve, contributing to the diagnostic framework for various skin disorders, including those previously not considered within its scope[

19].

Despite its potential, the diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy in MF remains debated, with studies reporting inconsistent findings.

This study evaluates dermatoscopic patterns observed in patients with histologically confirmed MF and SS. Specifically, this research seeks to determine whether certain dermatoscopic features correlate with disease stage or clinical presentation, potentially enhancing the utility of dermoscopy in the diagnostic workup of CTCLs. Therefore, this study will test the above criteria regarding standard diagnostic accuracy measures (DAMs) and inter-observer reproducibility.

Material and Methods

This study was conducted as an observational, monocentric, retrospective analysis at a specialised cutaneous lymphoma clinic. Patients included in the study had histologically confirmed diagnoses of MF or SS and were treated between January and December 2019. All patients provided written consent, and the study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (MF.Tox.Isto19).

Patient Selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histologically confirmed diagnoses of MF or SS, (2) availability of high-quality dermatoscopic Figures across multiple disease stages, and (3) follow-up data sufficient to assess disease progression. Patients were excluded if they had incomplete clinical records or dermatoscopic Figures of insufficient quality.

Dermatoscopic Evaluation

Dermatoscopic Figures were obtained using digital dermatoscopy with magnifications of up to 40x. All photos were standardised with consistent lighting conditions and uniform acquisition protocols. The analysis focused on specific dermatoscopic features, including the presence or absence of pigmentation, vessel morphology (e.g., linear, serpentine, clod, or dotted vessels), vessel distribution patterns (e.g., clustered, serpiginous), background colouration, scaling characteristics, and the type and presence of keratin plugs.

Statistical Analysis

The dermatoscopic features were correlated with clinical stages of MF/SS using the EORTC staging[

16]. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test to evaluate associations between dermatoscopic features and TNMB stages. The analysed features included vessel morphology, distribution, background colouration, scaling, and keratin plugs. The analysis aimed to identify potential correlations between these dermatoscopic characteristics, TNMB stages, lesion types (patches, plaques, nodules), and disease progression

An automatic two-step cluster analysis was also performed to identify patterns within the dermatoscopic features potentially associated with specific lesion types or disease stages. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS software (version 26.0), with descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and frequencies, used to summarise the dermatoscopic features across clinical stages. Graphical data representation was generated using Chat Gpt-4o.

Literature Review and Article Selection

For a synthetic narrative review of the literature, manuscript research on PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science was conducted to identify studies on dermoscopic features of MF and SS published between 2013 and 2025. Articles were included if they analysed histologically confirmed cases, correlated dermoscopy with disease stage, and included at least 10 patients.

Key dermoscopic features extracted have been reassumed, described and discussed in the context of our results.

Results

The study included 30 patients with histologically confirmed mycosis fungoides (MF) or Sézary syndrome (SS), comprising 19 males and 11 females, with a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 32–93). The patients presented with clinical lesions, including patches, plaques, and nodules, spanning various TNMB stages, from early-stage I A to advanced-stage IV A 1 [

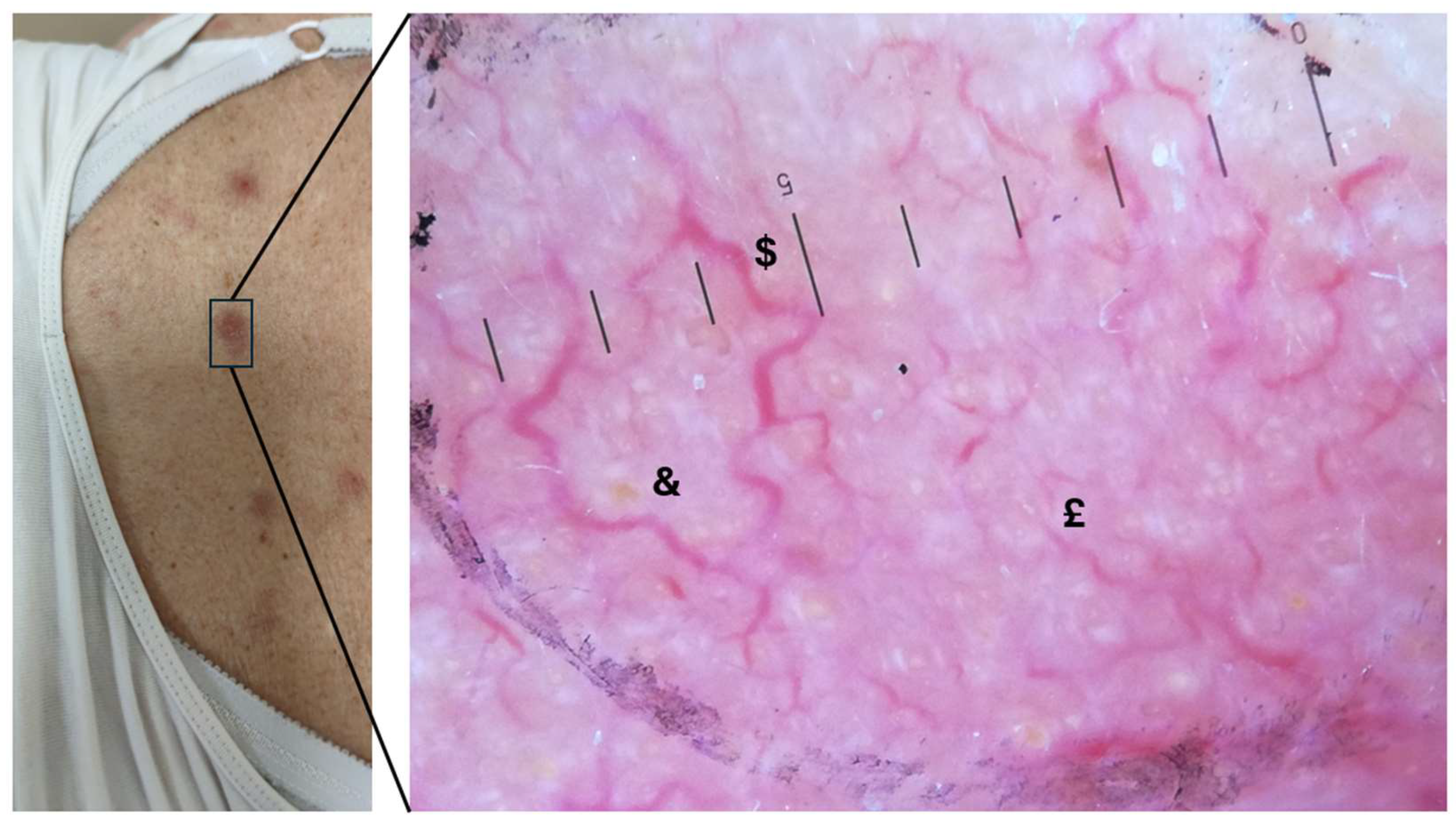

Table 1]. Dermoscopic examination commonly revealed non-pigmented MF lesions, predominantly exhibiting linear and serpiginous vascular patterns, occasionally with perifollicular distribution [

Figure 1]. While these dermoscopic features were recurrent, no consistent correlation was observed between vascular patterns, TNMB stages, or specific lesion types [

Table 2].

Dermatoscopic Findings

Across all patients, 100% of the lesions were pigment-free, and blood vessels were visible in every lesion. Vascular structures were the most prominent dermatoscopic feature, with linear vessels observed in 12 cases (40%) and serpentine vessels in 4 cases (13.3%). Other vessel morphologies included dotted vessels (11 cases, 36.7%) and clods (3 cases, 10%). Vessel distribution patterns varied, with 12 lesions (40%) showing a diffuse distribution and 11 (36.7%) showing perifollicular distribution. The predominant background colour was red, observed in 17 cases (56.7%), followed by orange in 12 cases (40%) and, in a minority of cases, brown (1 case, 3.3%). Scaling was observed in 23 patients (76.7%), with equal distribution between diffuse scaling (12 cases, 40%) and perifollicular scaling (11 cases, 36.7%). Keratin plugs were present in 12 cases (40%); when observed, they were predominantly yellow [

Table 2] [

Figure 2].

Correlation with TNMB Stages and Lesion Types

Mann-Whitney U test failed to demonstrate any statistically significant correlation between individual dermatoscopic features and TNMB stage. All p-values for vessel type, vessel distribution, background colour, scaling, and keratin plugs were higher than 0.05, suggesting no strong association between these dermatoscopic patterns and disease stage. Similarly, no significant relationship was found between specific dermatoscopic features and lesion types (patch, plaque, nodule).

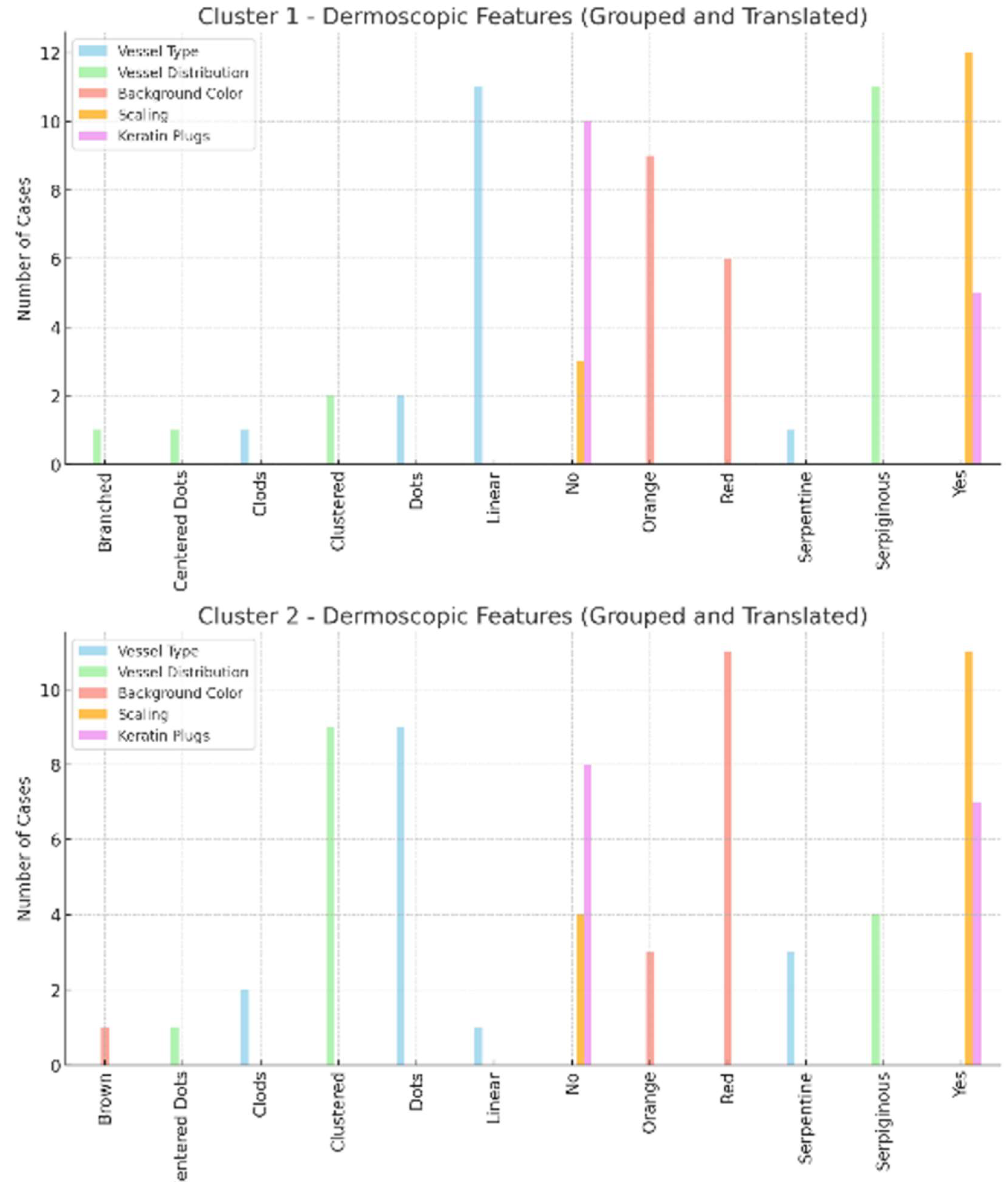

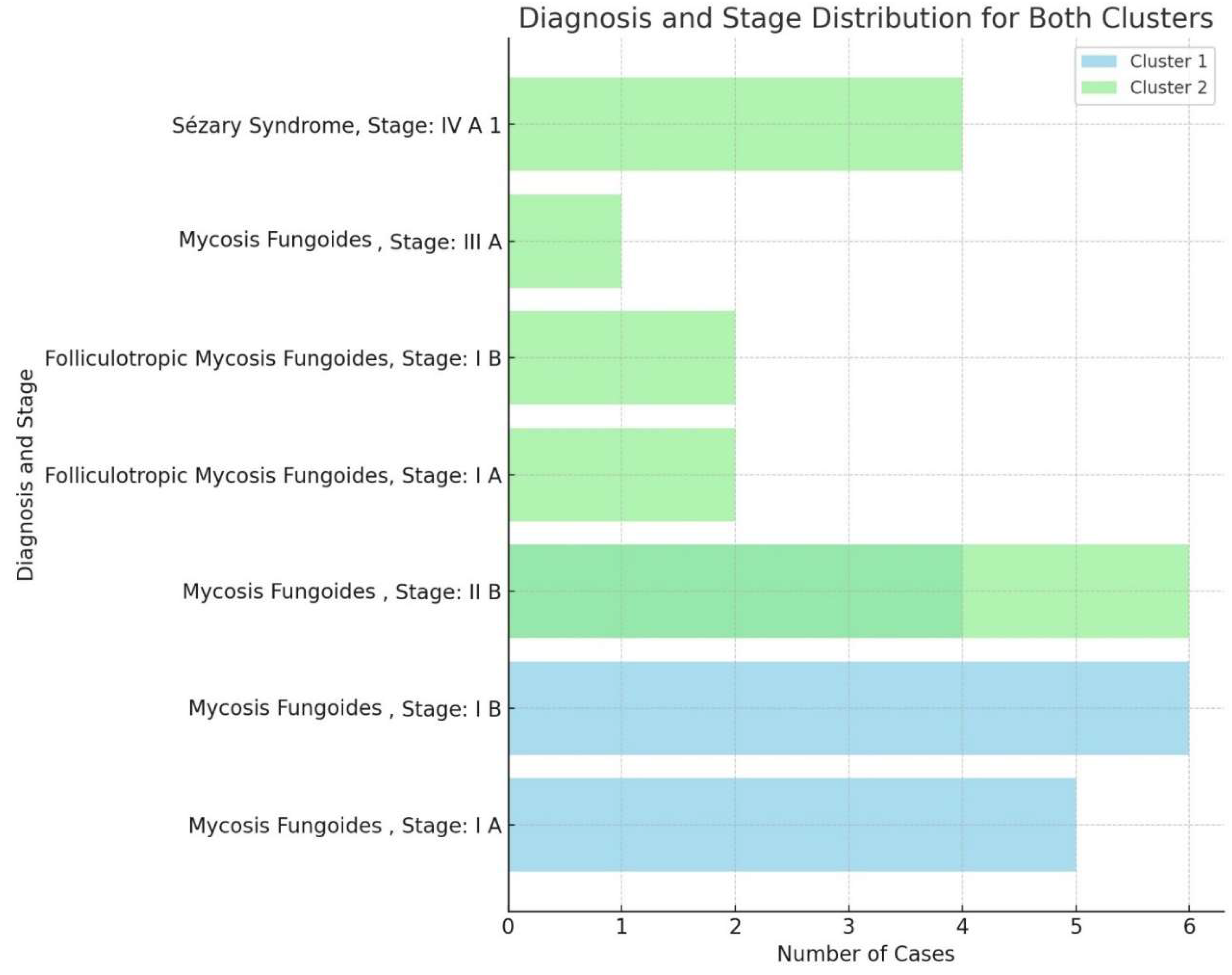

Cluster analysis identified two patient groups: Cluster 1, characterised by the presence of dots, clods, and less than 50% linear vessels, with no serpiginous distribution, predominantly associated with nodular lesions; and Cluster 2, characterised by serpentine and linear vessels with serpiginous distribution, observed in lesions at various stages. However, these clusters did not show significant subgroups nor a possible correlation with TNMB staging [

Figure 3].

Literature Review

Nine studies, including 411 patients, published between 2013 and 2025 examined the role of dermoscopy in diagnosing and staging mycosis fungoides (MF)[

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. These studies analysed dermoscopic features across different MF subtypes, variations in vascular and pigmentary structures based on skin tone, and correlations with histopathological findings.

Dermoscopy in Early-Stage MF

Most studies reported that fine, short linear vessels, spermatozoa-like structures, and an orange-yellow background are the most frequently observed dermoscopic markers in early-stage MF, particularly in the patch stage¹⁴. These features were described as having high sensitivity and specificity in differentiating patch-stage MF from clinically similar dermatoses, including eczema, psoriasis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE)¹⁵.

Repetitive dermoscopic patterns were identified in patch-stage MF, consisting of a non-homogeneous pink to the erythematous background, patchy orange-red discolouration, white scaling, and a combination of dotted, short linear, and spermatozoa-like vessels¹⁵. The presence of spermatozoa-like vessels, defined as a mixture of linear and dotted vascular patterns, was consistently noted across studies¹⁵. The vascular distribution was irregular and patchy, in contrast to the more uniform dotted vessel pattern observed in psoriasis¹⁶ exceed.

Histopathological analyses showed that linear vessels correlated with elongated and dilated capillaries in the papillary dermis, while the orange-yellow background was associated with epidermal atrophy and dermal fibrosis¹⁶. The white scaling observed in MF lesions corresponded to hyperkeratosis and focal parakeratosis¹⁶.

Vascular and Scaling Variability in Disease Progression

Several studies reported a correlation between vascular morphology and MF disease progression. Fine linear vessels were predominant in patch-stage MF, while in plaque and tumour-stage MF, branched linear vessels, ulceration, and bright white structureless areas were more frequently observed¹⁷. Bright white areas were mainly present in advanced lesions, corresponding histologically to dermal fibrosis and sclerotic changes¹⁷.

Scaling patterns varied across different MF stages. Patch-stage lesions were associated with fine, patchy white scales, whereas thicker, perifollicular, or geometric white scales were more commonly observed in plaque-stage MF¹⁸. Geometric white scales were histologically correlated with alternating parakeratosis and orthokeratosis in the stratum corneum¹⁸.

Several studies analysed vascular and scaling patterns about TNMB staging, identifying a transition from linear vessels in early MF to branched vascular structures in more advanced disease stages¹⁹. Differences in background colouration, vascular morphology, and scaling type were also noted across MF stages²⁰.Vascular and Scaling Variability in Disease Progression

Others reported a correlation between vascular morphology and MF disease progression. Fine linear vessels were predominant in patch-stage MF, while in plaque and tumour-stage MF, branched linear vessels, ulceration, and bright white structureless areas were more frequently observed. Bright white areas were mainly present in advanced lesions, corresponding histologically to dermal fibrosis and sclerotic changes.

Scaling patterns varied across different MF stages. Patch-stage lesions were associated with fine, patchy white scales, whereas thicker, perifollicular, or geometric white scales were more commonly observed in plaque-stage MF. Geometric white scales were histologically correlated with alternating parakeratosis and orthokeratosis in the stratum corneum.

Finally, vascular and scaling patterns about TNMB staging have been addressed and defined, identifying a transition from linear vessels in early MF to branched vascular structures in more advanced disease stages. Differences in background colouration, vascular morphology, and scaling type were also noted across MF stages.

Dermoscopy in MF Subtypes and Variants

Other studies analysed dermoscopic differences across MF subtypes. In stage IIA MF, the most frequently observed features were orange-yellow patches (88.2%), short fine linear vessels (82.3%), geometric white scales (70.5%), perifollicular white scales (47%), and white patches (35.2%)²¹. In contrast, in parapsoriasis (PP), dotted vessels (94.1%), diffuse lamellar white scales (88.2%), and dotted and globular vessels (70.5%) were more frequently reported²¹. Additional findings such as spermatozoa-like structures, purpuric dots, collarette white scales, and Y-shaped arborising vessels were identified in MF but were not statistically significant²¹.

In folliculotropic MF, studies consistently reported follicular keratotic plugs and perifollicular white scaling as the most characteristic dermoscopic findings²². In addition to follicular changes, dilated follicles and lack of hair structures were also observed, corresponding histologically to follicular infiltration by neoplastic T cells²².

One study analysed dermoscopy in purpuric MF and found that fine, short linear vessels and spermatozoa-like structures were significantly more common in MF, whereas pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPD) showed erythematous globules, reticular pigmentation, and dull red background²³.

A study on MF in patients with skin of colour identified white streaks and a pseudo network pattern as predominant dermoscopic features, with vascular morphology playing a less significant role compared to findings in lighter skin tones²⁴.

Hair shaft abnormalities, particularly pili torti and 8-shaped hairs, were described as a novel dermoscopic finding in patch/plaque-stage MF²⁵. These features were suggested to correlate with follicular involvement in the disease²⁵.

Study Limitations and Summary

All the reviewed studies suffered from different degrees of selection bias due to study design²⁶. Most studies had small sample sizes, and many were single-centre retrospective analyses²⁶. Additionally, standardised criteria for dermoscopic evaluation were sometimes lacking, making a direct comparison across studies difficult²⁶. Variability in Figure acquisition techniques, magnifications, and dermoscopic terminology further contributed to inconsistencies in reported findings²⁶.

Despite these limitations, the studies provide insights into recurrent dermoscopic features across MF subtypes, including variations based on disease stage, skin tone, and lesion type²⁷. The findings from the reviewed studies are summarised in

Table 3.

Discussion

MF and SS are among the primary (lymphoid-derived cancers of the skin[

31], representing the most common subtypes of CTCLs.

A broad spectrum of clinical appearances and significant variability among different patients characterises MF. Apart from the most frequent clinical pictures, it may also encompass bullous, hypopigmented, ichthyosiform, keratoderma-like, pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like, papular, poikilodermatous, psoriasiform, pustular, and verrucous morphologies[

3,

28]. The wide array of presentations can make the diagnosis of MF particularly challenging since it often mimics other dermatological conditions, thus expanding the extensive differential diagnoses, which include both benign inflammatory dermatoses and malignant diseases. Moreover, it is of note that, in early stages, MF often show subtle, non-specific histopathological findings, requiring a careful process of correlation with immunohistochemical features to reach a definitive diagnosis. [

15].

Alongside the challenges in achieving accurate MF identification, the frequent diagnostic delay in the early phase is another significant issue. Initial lesions are often misclassified as benign inflammatory conditions like eczema or psoriasis, resulting in extended treatments without a previous histological evaluation, possibly hesitating in the rapid progression of the cutaneous lymphoma.[

32,

33]. Early diagnosis of MF can significantly impact the final treatment outcomes by enabling the use of mild, non-harmful, skin-directed therapies leading to better clinical results and quality of life.[

32] Therefore, any method, tool or approach showing a potential contribution to improving the accuracy and reliability of the diagnostic process should be embraced and thoroughly studied to ensure its efficacy and applicability.

Similar to other dermatological conditions, significant efforts are being made to integrate dermoscopy into the diagnostic workflow for MF and SS to improve the accuracy of the clinical evaluation. As highlighted by various authors, dermatoscopy has become an indispensable tool in modern practice, often referred to as the dermatologist’s stethoscope.19 Dermoscopy may provide valuable diagnostic support by identifying specific patterns that correspond to histopathological alterations in the examined tissue, allowing for a noninvasive and highly informative assessment.

This study aimed to investigate dermoscopic features associated with MF and SS to identify characteristics that could be helpful in their diagnosis. However, no significant correlations were found between dermoscopic patterns, lesion types, or TNMB staging. Considering the inherent complexity of MF diagnosis due to the clinical and histological features closely resembling those of other skin conditions, it is unlikely that dermoscopic characteristics alone would be highly specific enough to narrow the differential diagnosis significantly.

An orange-erythematous background is a well-documented dermoscopic feature of the patch stage in MF, as supported by previous studies [

22,

23]. Nevertheless, this characteristic is not exclusive to MF, as it is also commonly seen in inflammatory dermatoses such as granulomatous inflammatory or infectious diseases[

34,

35], cutaneous xanthomas, pityriasis rubra pilaris[

36]

Similarly, the type and distribution of scales observed in our MF cases align with findings from earlier research[

23,

26]. However, these features are also detectable in a broad spectrum of inflammatory skin disorders, limiting their specificity for MF diagnosis.

In contrast, the literature highlights specific dermoscopic features in early-stage MF, particularly regarding vascular morphology. Previous studies have identified fine short linear vessels as a highly sensitive (93.7%) and specific (97.1%) dermoscopic feature of early-stage MF[

18,

20,

23,

25] compared to chronic dermatitis, which represents one of the most common differential diagnoses. Moreover, detecting a linear disposition of blood vessels was advocated to be more associated with the early stage of the disease. In contrast, dotted vessels and red clods seemed to correlate with later phases of the disease, possibly due to the vertical growth pattern of skin lesions29. Polymorphous vascular structures, on the other hand, are more commonly reported in CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma[

24,

25,

37].

However, our findings, as well as those of other studies in the literature, did not demonstrate a clear and robust correlation between vessel type and disease stage, suggesting that dermoscopy alone is insufficient for staging MF or SS. Our study's absence of consistent patterns emphasises the necessity of histopathological confirmation in diagnosing cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (CLDs) and CTCLs.

These results support the need for additional research to better define the potential diagnostic role of dermoscopy in early MF detection[

38]. Even in the absence of high diagnostic specificity, the description of dermoscopic patterns of MF may increase clinician awareness and potentially lead to a reduced diagnostic delay.

Spermatozoa-like vessels, a distinctive vascular structure combining dotted and linear components, have been proposed as a highly specific dermoscopic feature of MF[

23]. However, this morphology was not observed consistently or reproducibly in our study. Other authors have reported similar challenges in identifying this pattern 26. The inconsistency in these findings may be attributed to the lack of standardised terminology for describing dermoscopic patterns in MF and the unavoidable inter-operator variability. This lack of uniformity complicates the identification of recurring patterns across studies, hindering reliable confirmation of their diagnostic value[

20,

21]. Standardising dermoscopic descriptors could enhance pattern recognition and improve diagnostic accuracy. To clarify the specificity of these vascular morphologies in MF, comparative studies that analyse the dermoscopic features of MF against those of other dermatoses would be invaluable. Such research could determine whether these patterns are specific to MF or shared among other inflammatory or neoplastic conditions.

The variability in dermoscopic findings across studies may also be attributed to the heterogeneity of CLDs and their overlap with benign dermatoses. While our study did not identify significant correlations between dermoscopic features and lesion type, other research has highlighted dermoscopy's potential to reveal patterns, such as orange-yellowish patchy areas and white streaks, particularly in rarer clinical manifestations like poikilodermic MF [

39,

40]. The observation of brown pigmentation arranged in different configurations, such as dots, structureless areas and reticular lines, was also associated with the poikilodermatous variant of MF.

Pigmentary changes appear to be the main features appreciable in MF dermoscopy in the skin of colour since the vascular changes are less detectable: the classic variant has been associated with white lines and a pseudo network resulting from brown-grey clods and dots, while a weakened pigment network38 characterises the hypopigmented variant. However, no significant evidence about the reliability of dermoscopy in MF in the skin of colour is available[

27].

These findings suggest that specific MF variants may exhibit distinct dermoscopic features, although further validation is needed.

Interestingly, a recent study focused on the trichoscopy of MF lesions observed a high prevalence of hair shaft abnormalities, such as numerous pili torti and 8-shaped hairs, compared to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis[

30]

The limitations of this study include a small sample size, which may have hindered the detection of subtle correlations between dermatoscopic features and disease stages. Additionally, the retrospective design and potential variability in Figure quality could have introduced bias. Inconsistencies in the terminology used to describe dermoscopic features may have further complicated the identification of recurring patterns, highlighting the need for standardised descriptors in future research.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the limitations of using dermoscopy for diagnosing and staging MF and SS. While previous research has identified specific dermoscopic features with high sensitivity, our findings did not replicate these results, and further analysis revealed no significant correlation between dermoscopic features and clinical stages or lesion types. This discrepancy suggests that dermoscopic variability in MF may be more substantial than previously reported, potentially due to differences in imaging techniques, interobserver variability, and the retrospective nature of most studies.

Also, our dataset did not consistently observe hallmark features such as spermatozoa-like vessels, previously described as highly specific for MF. This inconsistency may be attributed to heterogeneity in dermoscopic terminology and assessment criteria, which remain non-standardized across studies. The lack of universal consensus on dermoscopic descriptors further complicates the reproducibility of findings and underscores the need for a systematic approach to dermoscopic feature classification in MF.

Despite the increasing interest in dermoscopy as a potential diagnostic tool for MF and SS, our results reinforce the necessity of clinical assessment and histopathological confirmation for an accurate diagnosis. The absence of reliable correlations between dermoscopic features and MF staging suggests that dermoscopy alone cannot replace standard diagnostic approaches, particularly in early-stage disease, where clinical and histopathological overlap with inflammatory dermatoses is common.

Future research should prioritise large-scale, multicenter prospective studies with standardised dermoscopic assessment criteria to improve diagnostic accuracy and interobserver agreement. Additionally, integrating artificial intelligence and machine learning models into dermoscopic analysis could enhance feature recognition and classification, providing a more objective and reproducible approach to MF diagnosis and monitoring. Until such advancements are established, dermoscopy should be considered a complementary tool rather than a definitive diagnostic method for MF and SS.

Ethical Approval and/or Institutional Review Board (IRB)

n° Clin.Isto. Tp.19, Bologna local ethical committee

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Feng H, Beasley J, Meehan S, Liebman TN. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. [CrossRef]

- Roccuzzo G, Mastorino L, Gallo G, Fava P, Ribero S, Quaglino P. Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides: Current Guidance and Experience from Clinical Practice. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, 1: 15, 1899. [CrossRef]

- Hodak E, Amitay-Laish I. Mycosis fungoides: A great imitator. Clin Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Cristofoletti C, Narducci MG, Russo G. Sézary Syndrome, recent biomarkers and new drugs. Chin Clin Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Pileri A, Guglielmo A, Grandi V, et al. The Microenvironment’s Role in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: From Progression to Therapeutic Implications. Cells, 2780. [CrossRef]

- Pileri A, Morsia E, Zengarini C, et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: state of the art and a focus on the Italian Marche region. Eur J Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Maguire A, Puelles J, Raboisson P, Chavda R, Gabriel S, Thornton S. Early-stage Mycosis Fungoides: Epidemiology and Prognosis. Acta Derm Venereol, 0001. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman AE, Patel K, Goyal K, et al. Mycosis fungoides: developments in incidence, treatment and survival. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV, 2288. [CrossRef]

- Ottevanger R, de Bruin D t., Willemze R, et al. Incidence of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome in the Netherlands between 2000 and 2020. Br J Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Keto J, Hahtola S, Linna M, Väkevä L. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a population-wide study on prevalence and health care use in Finland in 1998–2016. BMC Health Serv Res. [CrossRef]

- Trautinger F, Eder J, Assaf C, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome – Update 2017. Eur J Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Guglielmo A, Zengarini C, Agostinelli C, Motta G, Sabattini E, Pileri A. The Role of Cytokines in Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma: A Focus on the State of the Art and Possible Therapeutic Targets. Cells. [CrossRef]

- Zengarini C, Guglielmo A, Mussi M, et al. A Narrative Review of the State of the Art of CCR4-Based Therapies in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas: Focus on Mogamulizumab and Future Treatments. Antibodies. [CrossRef]

- Quaglino P, Maule M, Prince HM, et al. Global patterns of care in advanced stage mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome: a multicenter retrospective follow-up study from the Cutaneous Lymphoma International Consortium. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello P, Sagnelli C, Ronchi A, et al. Multidisciplinary Approach to the Diagnosis and Therapy of Mycosis Fungoides. Healthcare. [CrossRef]

- Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood, 1713. [CrossRef]

- Ryu HJ, Kim SI, Jang HO, et al. Evaluation of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoides. Cells, 2758. [CrossRef]

- Piccolo V, Russo T, Agozzino M, et al. Dermoscopy of Cutaneous Lymphoproliferative Disorders: Where Are We Now? Dermatology. [CrossRef]

- Russo T, Piccolo V, Lallas A, Argenziano G. Recent advances in dermoscopy. F1000Research. [CrossRef]

- Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardisation of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: Results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1093. [CrossRef]

- Errichetti E, Zalaudek I, Kittler H, et al. Standardization of dermoscopic terminology and basic dermoscopic parameters to evaluate in general dermatology (non-neoplastic dermatoses): an expert consensus on behalf of the International Dermoscopy Society. Br J Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Lallas A, Apalla Z, Lefaki I, et al. Dermoscopy of early stage mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. [CrossRef]

- Soliman SH, Ramadan WM, Elashmawy AA, Sarsik S, Lallas A. Dermoscopy in the Diagnosis of Mycosis Fungoides: Can it Help? Dermatol Pract Concept, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Errichetti E, Apalla Z, Geller S, et al. Dermoscopic spectrum of mycosis fungoides: a retrospective observational study by the International Dermoscopy Society. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV, 1045. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk MK, Zindancı I, Zemheri E. Dermoscopy of stage llA mycosis fungoides. North Clin Istanb. [CrossRef]

- Żychowska M, Kołcz K. Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses—Psoriasis, Nummular Eczema, Mycosis Fungoides and Pityriasis Rosea. J Clin Med. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura M, Huerta T, Williams K, Hristov AC, Tejasvi T. Dermoscopic Features of Mycosis Fungoides and Its Variants in Patients with Skin of Color: A Retrospective Analysis. Dermatol Pract Concept, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nasimi M, Bonabiyan M, Lajevardi V, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses versus purpuric mycosis fungoides: Clinicopathologic similarities and new insights into dermoscopic features. Australas J Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Ali BMM, El-Amawy HS, Elgarhy L. Dermoscopy of mycosis fungoides: could it be a confirmatory aid to the clinical diagnosis? Arch Dermatol Res. [CrossRef]

- Rakowska A, Jasińska M, Sikora M, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in erythrodermic cases may be suspected on the basis of scalp examination with dermoscopy. Sci Rep. [CrossRef]

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. [CrossRef]

- Hodak E, Geskin L, Guenova E, et al. Real-Life Barriers to Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoides: An International Expert Panel Discussion. Am J Clin Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Perez JS, Carey VJ, Odejide OO, et al. Integrative epidemiology and immunotranscriptomics uncover a risk and potential mechanism for cutaneous lymphoma unmasking or progression with dupilumab therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol, S: online , 2024, 7 November 2024. [CrossRef]

- Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermatoscopy of Granulomatous Disorders. Dermatol Clin. [CrossRef]

- Mussi M, Zengarini C, Chessa MA, Gelmetti A, Piraccini BM, Neri I. Granular parakeratosis: dermoscopic findings of an uncommon dermatosis. Int J Dermatol, 1796. [CrossRef]

- Bañuls J, Arribas P, Berbegal L, DeLeón FJ, Francés L, Zaballos P. Yellow and orange in cutaneous lesions: clinical and dermoscopic data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV, 2317. [CrossRef]

- Adya KA, Janagond AB, Inamadar AC, Arakeri S. Dermoscopy of Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Negative Large T-Cell Lymphoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. [CrossRef]

- Errichetti E, Geller S, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermatoscopy of nodular/plaque-type primary cutaneous T- and B-cell lymphomas: A retrospective comparative study with pseudolymphomas and tumoral/inflammatory mimickers by the International Dermoscopy Society. J Am Acad Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Tončić RJ, Radoš J, Ćurković D, Ilić I, Caccavale S, Bradamante M. Dermoscopy of Syringotropic and Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides. Dermatol Pract Concept, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xu P, Tan C. Dermoscopy of poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (MF). J Am Acad Dermatol. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Macroscopic and dermoscopic examination of a suspicious cutaneous lesion (10× magnification). On the left, a clinical Figure shows an erythematous lesion on the patient's back, with poorly defined margins and mild surface scaling. On the right, a magnified dermoscopic Figure reveals a predominant vascular pattern, featuring branched vessels ($) surrounding white and yellow keratin plugs, along with serpiginous vessels (£) on a heterogeneous erythematous background (&). The presence of subtle scaling may suggest concurrent inflammation (10x magnification).

Figure 1.

Macroscopic and dermoscopic examination of a suspicious cutaneous lesion (10× magnification). On the left, a clinical Figure shows an erythematous lesion on the patient's back, with poorly defined margins and mild surface scaling. On the right, a magnified dermoscopic Figure reveals a predominant vascular pattern, featuring branched vessels ($) surrounding white and yellow keratin plugs, along with serpiginous vessels (£) on a heterogeneous erythematous background (&). The presence of subtle scaling may suggest concurrent inflammation (10x magnification).

Figure 2.

Graphs of the dermoscopic features for two distinct clusters, showing the distribution of vessel type, vessel distribution, background colour, scaling, and keratin plugs across the two groups. Cluster 1 and 2 are differentiated by their dermoscopic patterns, with noticeable variations in vessel types and background colours.

Figure 2.

Graphs of the dermoscopic features for two distinct clusters, showing the distribution of vessel type, vessel distribution, background colour, scaling, and keratin plugs across the two groups. Cluster 1 and 2 are differentiated by their dermoscopic patterns, with noticeable variations in vessel types and background colours.

Figure 3.

Panel providing diagnosis and TNMB stage distribution for both clusters, highlighting the representation of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome cases across various stages (I A, I B, II B, III A, and IV A 1). The cases for each diagnosis and stage are compared between the two clusters.

Figure 3.

Panel providing diagnosis and TNMB stage distribution for both clusters, highlighting the representation of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome cases across various stages (I A, I B, II B, III A, and IV A 1). The cases for each diagnosis and stage are compared between the two clusters.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population, including age distribution, sex, diagnosis, and disease stages.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population, including age distribution, sex, diagnosis, and disease stages.

| Age |

|

70 years |

Std dev 14.56, CI. 59.29 - 69.71 |

| Sex |

Male |

19 |

|

| |

Female |

11 |

|

| Diagnosis |

|

|

|

| |

Mycosis Fungoides |

22 |

73.3 |

| |

Follicolotropic Mycosis fungoides |

4 |

13.3 |

| |

Sézary Syndrome |

4 |

13.3 |

| Stage |

IA |

7 |

23.3 |

| |

IB |

8 |

26.6 |

| |

II |

10 |

33.3 |

| |

III A |

1 |

3.33 |

| |

IV A1 |

4 |

13.3 |

Table 2.

Dermoscopy characteristics of the study population, detailing the presence of pigment, background colour, vessel distribution, vessel types, scaling types, and keratin plugs. The table includes counts, percentages, and p-values to assess the statistical significance of these features of the study's variables.

Table 2.

Dermoscopy characteristics of the study population, detailing the presence of pigment, background colour, vessel distribution, vessel types, scaling types, and keratin plugs. The table includes counts, percentages, and p-values to assess the statistical significance of these features of the study's variables.

| Dermoscopy |

Class |

Value |

Count |

Pergentace |

P Value |

| |

Pigment |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| |

|

Yes |

0 |

0 |

|

| |

|

No |

30 |

100% |

|

| |

Background colour |

|

|

|

> 0.05 |

| |

|

Red |

17 |

56.7% |

|

| |

|

Orange |

12 |

40% |

|

| |

|

Brown |

1 |

3.3% |

|

| |

Vessel Distribution |

|

|

|

> 0.05 |

| |

|

Serpiginous |

15 |

50% |

|

| |

|

Clustered |

12 |

36.6% |

|

| |

|

Centered Dots |

2 |

6.6% |

|

| |

|

Branched |

1 |

3.3% |

|

| |

Vessel Type |

|

|

|

> 0.05 |

| |

|

Linear |

12 |

40% |

|

| |

|

Serpentine |

4 |

13.3% |

|

| |

|

Dots |

11 |

36.7% |

|

| |

|

Clods |

3 |

10% |

|

| |

Scaling Type |

|

|

|

> 0.05 |

| |

|

Diffuse Scaling |

12 |

40% |

|

| |

|

Perifollicular Scaling |

11 |

36.7% |

|

| |

Keratin Plugs |

|

|

|

> 0.05 |

| |

|

Yes |

12 |

40% |

|

| |

|

No |

18 |

60% |

|

Table 3.

Summary of studies analyzing the dermoscopic features of mycosis fungoides (MF), including study details, number of patients, identified dermoscopic patterns, and key finding.

Table 3.

Summary of studies analyzing the dermoscopic features of mycosis fungoides (MF), including study details, number of patients, identified dermoscopic patterns, and key finding.

| Study |

Journal & Article Title |

Number of Patients |

Dermoscopic Features |

Findings & Relevance |

| Lallas et al. (2013) |

Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology - 'Dermoscopy of early stage mycosis fungoides' |

67 |

Fine short linear vessels, orange-erythematous background, Spermatozoa-like vessels |

Fine short linear vessels (sensitivity 93.7%, specificity 97.1%) and orange-yellowish patchy areas (sensitivity 90.6%, specificity 99.7%). For early MF. A characteristic vascular structure resembling spermatozoa was also found to be highly specific for diagnosing mycosis fungoid. |

| Ozturk et al. (2019) |

North Clinical Istanbul - 'Dermoscopy of stage IIa mycosis fungoides' |

17 (on 34) |

Orange-yellow patches, short fine linear vessels, and geometric/perifollicular white scales are key markers for stage IIA MF diagnosis. |

Specific patterns can differentiate MF from PP, but spermatozoa-like structures, purpuric dots, collarette white scales, and Y-shaped arborizing vessels were observed but not statistically significant. |

| Nakamura et al. (2021) |

Dermatology Practice & Concept - 'Dermoscopy of Mycosis Fungoides and Its Variants in Patients with Skin of Color' |

11 |

White streaks, pseudo-network in skin of colour |

Dermoscopic features of MF in patients with skin of colour are predominantly characterised by striking pigmentary alteration. Vessel morphology is not a reliable diagnostic feature |

| Errichetti et al. (2022) |

Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology - 'Dermoscopic spectrum of mycosis fungoides: a retrospective observational study by the International Dermoscopy Society' |

118 |

Linear vessels and orange structureless areas, with a higher prevalence of patchy or furrow-aligned white scaling and linear-curved vessels |

Dermoscopy helps identify classic MF, especially in the patch stage. Orange-yellow areas, spermatozoa-like vessels, and linear vessels aid in separating MF from dermatitis and psoriasis. Disease progression shifts from linear to branched vessels, with ulceration and bright white areas in tumours. |

| Soliman et al. (2023) |

Dermatology Practical & Conceptual - 'Dermoscopy in the Diagnosis of Mycosis Fungoides: Can it Help?' |

88 |

Non-homogeneous pink to the erythematous background, patchy orange-red discolouration, whitish scales, and dotted, short linear, and spermatozoa-like vessels |

Repetitive dermoscopic pattern in MF, including the cited dermoscopic features, with variations depending on the clinical variant |

| Żychowska & Kołcz (2024) |

Journal of Clinical Medicine - 'Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses' |

26 (on 139) |

Polymorphous vascular patterns include dotted, linear, and spermatozoa-like vessels, white/yellow scaling, and orange structureless areas. Variants may show perifollicular scaling, follicular plugs, and pigmentary changes. |

Dermoscopy aids in identifying classic MF, especially in the patch stage. Linear vessels and orange structureless areas are key features, while branched vessels and ulceration are seen in tumour-stage MF. Variant-specific features, such as follicular plugs in folliculotropic MF, improve diagnostic accuracy. |

| Jasińska et al. (2024) |

Dermatology & Therapy - 'Hair Shaft Abnormalities as a Dermoscopic Feature of Mycosis Fungoides: Pilot Results' |

21 (on 55) |

Hair shaft abnormalities (pili torti, 8-shaped hairs) |

Hair shaft abnormalities are an important criterion that should be considered in the dermoscopic differentiation of the patchy/plaque mycosis fungoides |

| Mohamed Ali et al. (2025) |

Archives of Dermatological Research - 'Dermoscopy of Mycosis Fungoides: Could It Be a Confirmatory Aid to the Clinical Diagnosis?' |

53 |

Fine short linear vessels, spermatozoa-like vessels, thick linear blood vessels, geometric white scales, white structureless patches, orange-yellow patches |

Linear vessels and brownish pigmentary changes suggest early-stage MF, while dotted vessels, purpuric dots, and ulcerations are linked to advanced MF. Geometric white scales and orange-yellow structureless areas lack specificity for stage |

| Nasimi et al. (2021) |

Australasian Journal of Dermatology - 'Pigmented purpuric dermatoses versus purpuric mycosis fungoides: Clinicopathologic similarities and new insights into dermoscopic features' |

28 (on 41) |

Fine short linear vessels, spermatozoa-like structures, orange-yellow background, dotted vessels, erythematous globules, reticular pigmentation |

Fine short linear vessels and spermatozoa-like structures were significantly more common in purpuric MF, while PPD showed erythematous globules, reticular pigmentation, and a dull red background. Dermoscopy aids in differentiating these |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).