Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

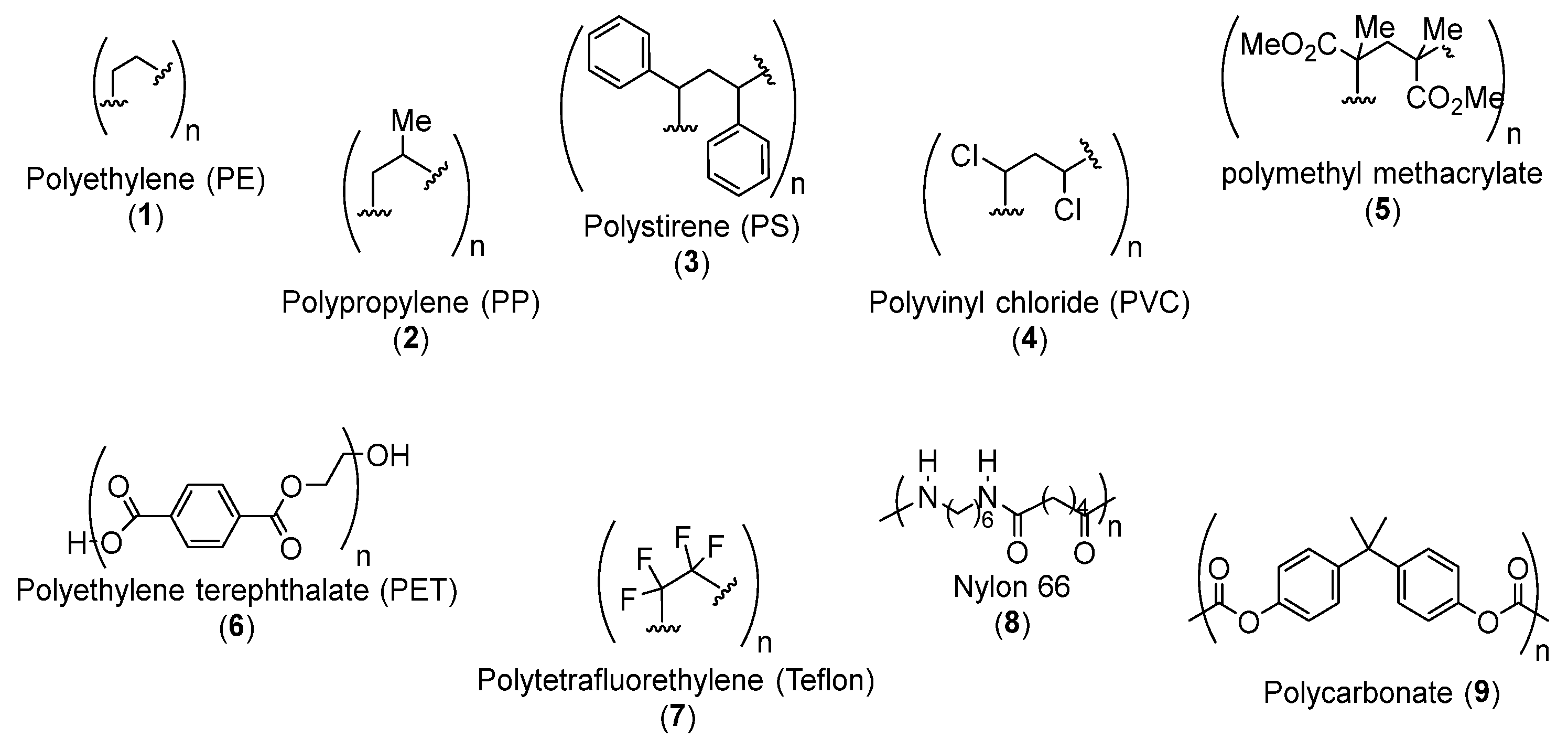

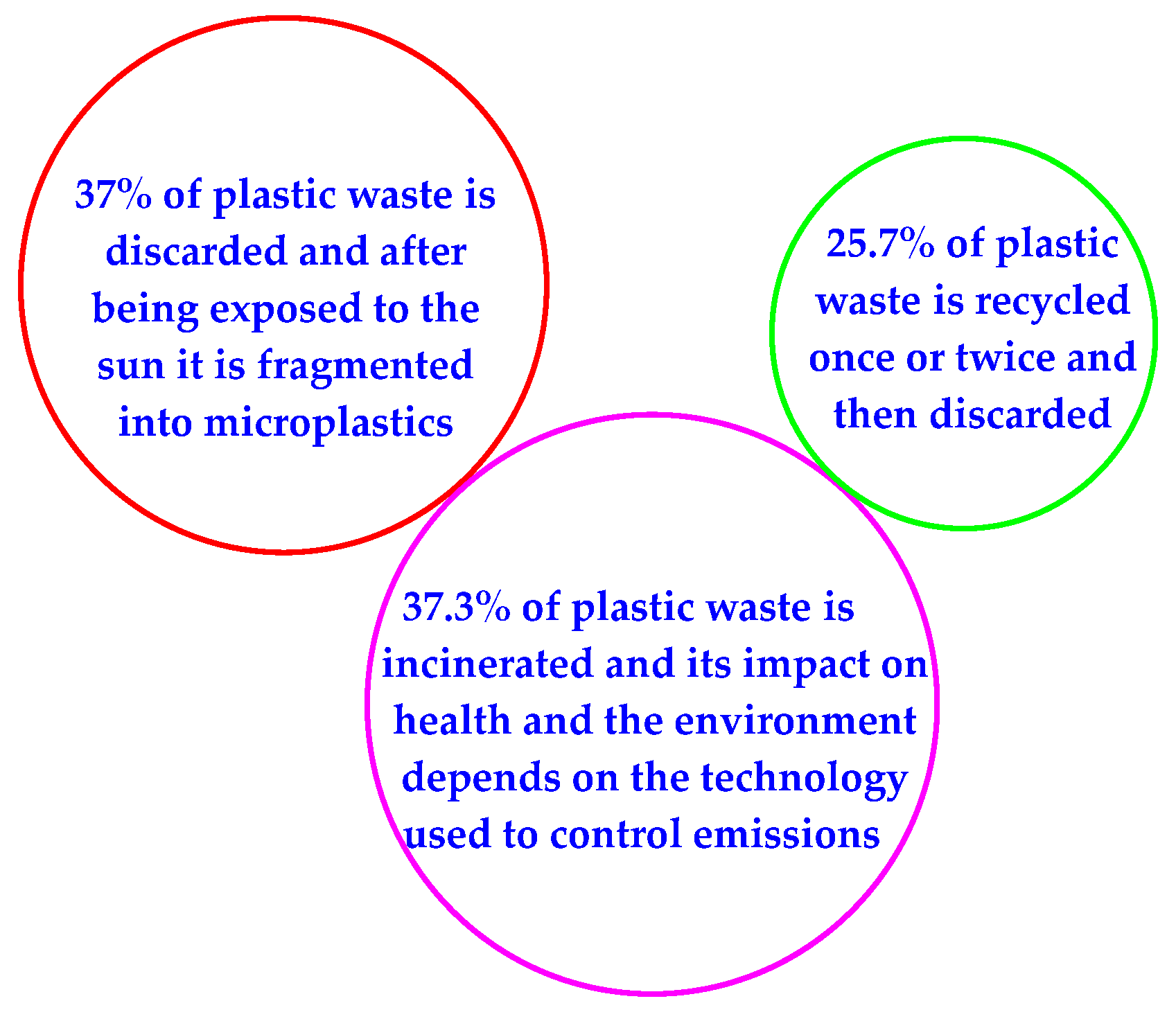

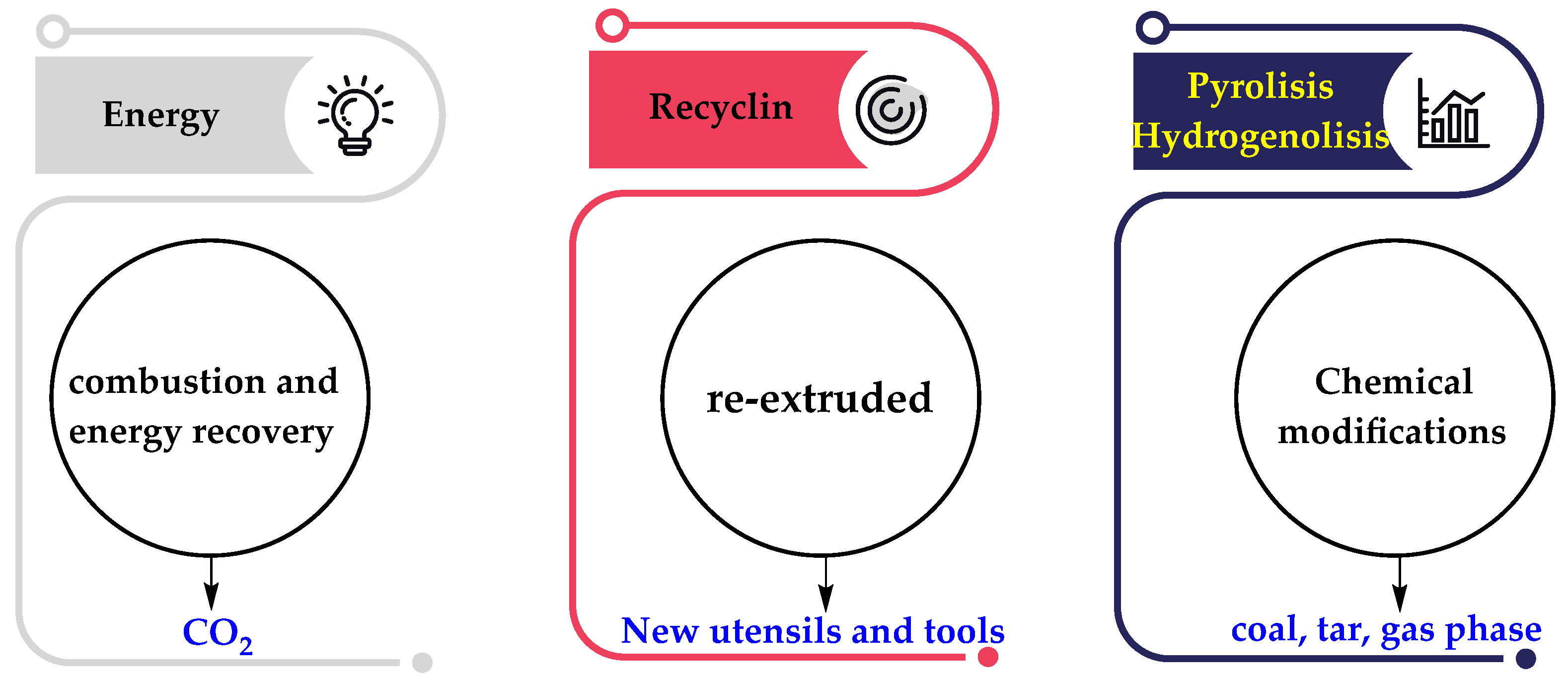

1. Introduction

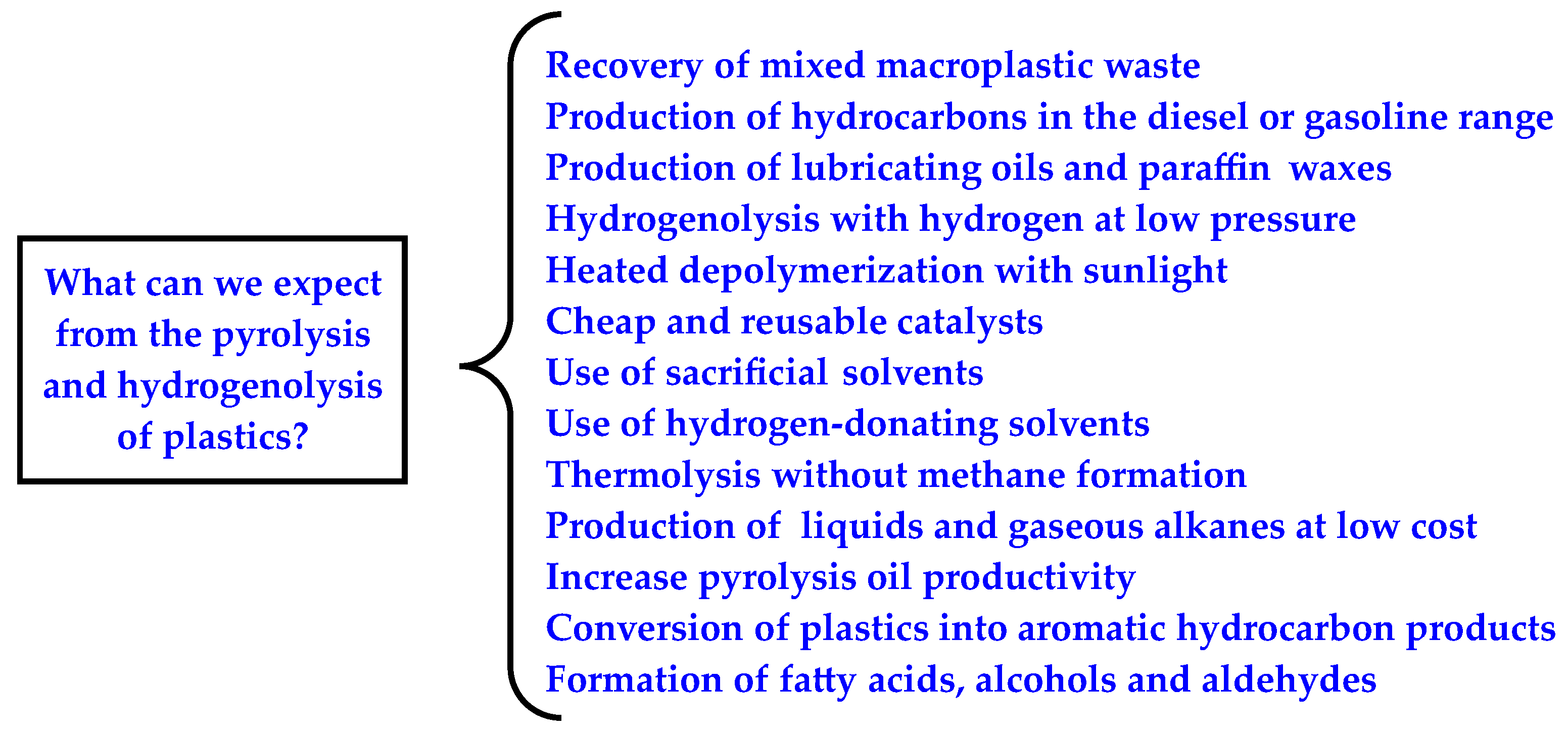

2. Pyrolysis cracking

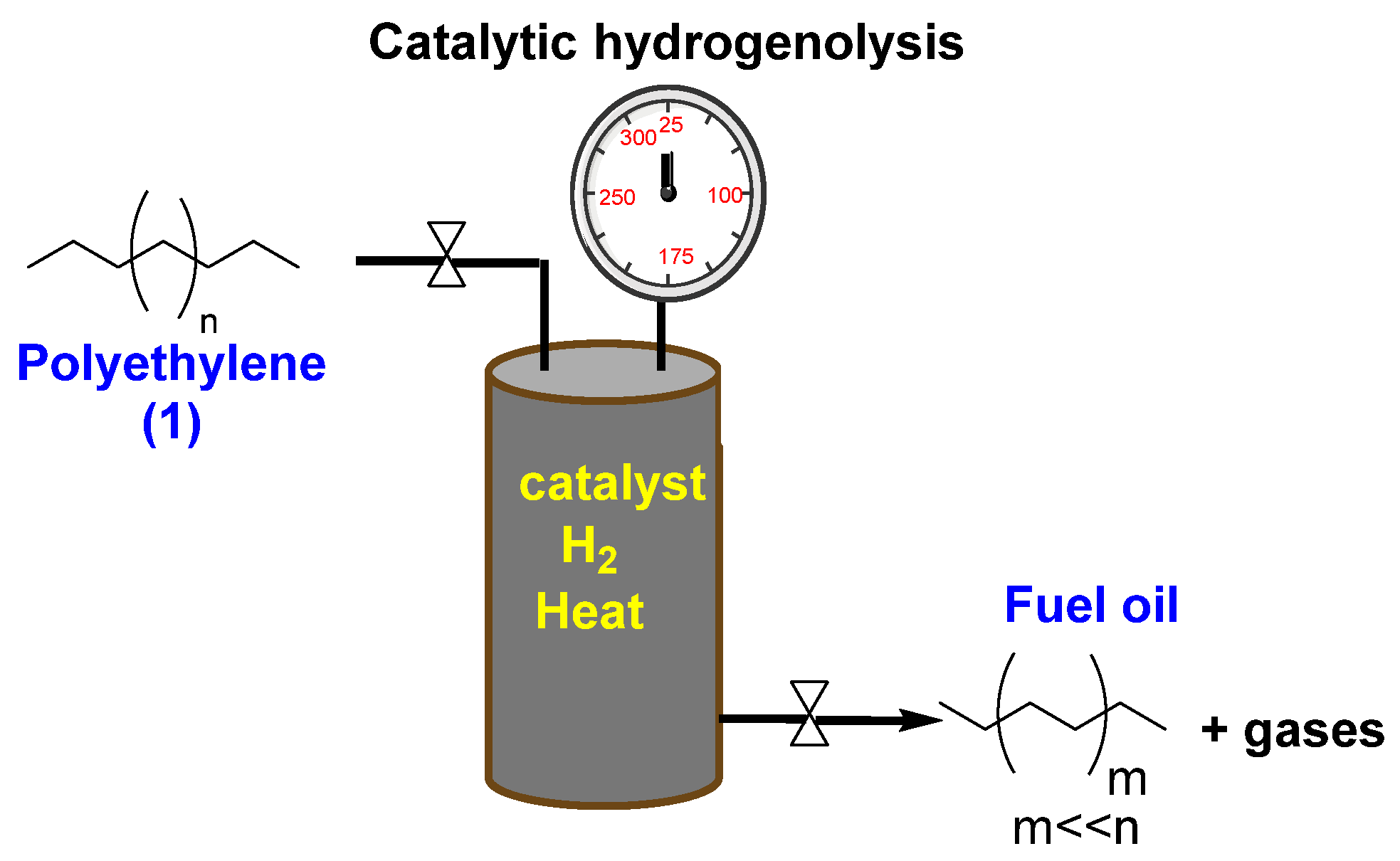

3. Cracking with Hydrogenolysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ambaye, T.G.; Djellabi, R.; Vaccari, M.; Prasad, S.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Rtimi, S. Emerging technologies and sustainable strategies for municipal solid waste valorization: Challenges of circular economy implementtion. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomollón-Bel, F. Ten Chemical Innovations That Will Change Our World: IUPAC identifies emerging technologies in Chemistry with potential to make our planet more sustainable. Chem. Int. 2019, 41, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomollón-Bel, F. IUPAC Top Ten Emerging Technologies in Chemistry 2021. Chem. Int. 2021, 43, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomollón-Bel, F.; García-Martínez, J. Emerging chemistry technologies for a better world. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUPAC Announces the 2023 top ten emerging technologies in chemistry. Available online: https://iupac.org/iupac-2023-top-ten/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Van Geem, K.M. Plastic waste recycling is gaining momentum. Science 2023, 381, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumjit, N.P.; Thomas, P.; Lai, C.W.; Johan, M.R.B.; Saravanakumar, M.P. Polymer-Recycling of Bulk Plastics. In Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials; Choudhury, I.A.; Hashmi, M.S.J., Eds.; Elsevier, 2020; pp 432-454.

- Here’s Where the World’s Plastic Wast Will End Up, by 2050. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-future-of-the-worlds-plastic/ (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Tang, G.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, F.; He, L.; Liu, M.; Huang, W.; Wu, H.; Liu, C. Waste plastic to energy storage materials: a state-of-the-art review. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 3738–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasopoulos, A.; Malinauskatie, J.; Zabnienska-Góra, A.; Jouhara, H. Life cycle assessment of plastic waste and energy recovery. Energy 2023, 277, 127576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kang, J.; Lee, B.; Hong, S.; Jeon, Y.; Bak, M.; Im, S.-K. Nonviable carbon neutrality with plastic waste-to-energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 3074–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, S.M.; Lettieri, P.; Baeyens, J. The valorization of plastic solid waste (PSW) by primary to quaternary routes: from re-use to energy and Chemicals. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Xu, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, M. Chemical recycling of polyolefins: a closed-loop cycle of waste to olefins. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, Z.O.G.; Shaver, M.P. Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, e2000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucknall, D.G. Plastics as a materials system in a circular economy. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2020, 378, 20190268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, I.; Jenks, M.J.F.; Roelands, M.C.P.; White, R.J.; van Harmelen, T.; de Wild, P.; van der Laan, G.P.; Meirer, F.; Keurentjes, J.T.F.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Beyond Mechanical Recycling: Giving New Life to Plastic Waste. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15402–15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, W.; Schlesselmann, B.; Simon, C. Olefins from polyolefins and mixed plastics by pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 1995, 32, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, B.; Kots, P.; Selvam, E.; Vlachos, D.G.; Ierapetritou, M.G. Techno-Economic and Life Cycle Analyses of Thermochemical Upcycling Technologies of Low-Density Polyethylene Waste. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 7170–7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Artetxe, M.; Amutio, M.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Thermochemical routes for the valorization of waste polyolefinic plastics to produce fuels and chemicals. A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 346–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; Delva, L.; Van Geem, K. Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burange, A.S.; Gawande, M.B.; Lam, F.L.Y.; Jayaram, R.V.; Luque, R. Heterogeneously catalyzed strategies for the deconstruction of high density polyethylene: plastic waste valorisation to fuels. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosen, M.; Mys, N.; Kusenberg, M.; Billen, P.; Dumoulin, A.; Dewulf, J.; Van Geem, K.M.; Ragaert, K.; De Meester, S. Detailed Analysis of the Composition of Selected Plastic Packaging Waste Products and Its Implications for Mechanical and Thermochemical Recycling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13282–13293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palza, H.; Aravena, C.; Colet, M. Role of the catalyst in the pyrolysis of polyolefin mixtures and used tires. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 3111–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Debbarma, S.; Maurya, P.; Anand, V. Depolymerization of waste plastics and chemicals. In Green Chemistry Approaches to Environmental Sustainability. Elsevier: 2024, pp 337-356.

- Faust, K.; Denifl, P.; Hapke, M. Recent Advances in Catalytic Chemical Recycling of Polyolefins. Chem. Cat. Chem. 2023, 15, e202300310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Konarova, M.; Foong, S.Y.; Lam, S.S.; Wagland, S.; Cao, R.; Li, Y.; Batalha, N.; et al. Retrieving back plastic wastes for conversion to value added petrochemicals: opportunities, challenges and outlooks. Appl. Energy 2023, 345, 121307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Zuo, Z.; Niu, Z. Recent advances in plastic recycling and upgrading under mild conditions. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 6949–6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusenberg, M.; Zayoud, A.; Roosen, M.; Thi, H.D.; Abbas-Abadi, M.S.; Eschenbacher, A.; Kresovic, U.; De Meester, S.; Van Geem, K.M. A comprehensive experimental investigation of plastic waste pyrolysis oil quality and its dependence on the plastic waste composition. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 227, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gala, A.; Guerrero, M.; Guirao, B.; Domine, M.E.; Serra, J.M. Characterization and Distillation of Pyrolysis Liquids Coming from Polyolefins Segregated of MSW for Their Use as Automotive Diesel Fuel. Energy & Fuels 2020, 34, 5969–5982. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Khan, M.I.; Ishaq, M.; Khan, H.; Gul, K.; Ahmad, W. Catalytic efficiency of some novel nanostructured heterogeneous solid catalysts in pyrolysis of HDPE. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 2512–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.T.; Elam, J.W.; Rabuffetti, F.A.; Ma, Q.; Weigand, S.J.; Lee, B.; Seifert, S.; Stair, P.C.; Poeppelmeier, K.R.; Hersam, M.C.; Bedzyk, M.J. Controlled Growth of Platinum Nanoparticles on Strontium Titanate Nanocubes by Atomic Layer Deposition. Small 2009, 5, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas-Abadi, M.S.; Kusenberg, M.; Zayoud, A.; Roosen, M.; Vermeire, F.; Madanikashani, S.; Kuzmanović, M.; Parvizi, B.; Kresovic, U.; De Meester, S.; Van Geem, K.M. Thermal pyrolysis of waste versus virgin polyolefin feedstocks: The role of pressure, temperature and waste composition. Waste Manag. 2023, 165, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whajah, B.; Heil, J.N.; Roman, C.L.; Dorman, J.A.; Dooley, K.M. Zeolite Supported Pt for Depolymerization of Polyethylene by Induction Heating. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 8635–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, S.; Van Haute, M.; Manos, G.; Karam, H.J.; Constantinou, A.; Al-Salem, S.M. Hydrotreatment over the Pt/Al2O3 Catalyst of Polyethylene-Derived Pyrolysis Oil and Wax. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 16181–16185. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, S.; Deng, J.; Yang, J.; Yu, S.; Xu, B.; Ma, D. Complete hydrogenolysis of mixed plastic wastes. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Chu, M.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Cao, M.; Ivasenko, O.; Sham, T.-K.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Q.; Chen, J. Entropy Confinement Promotes Hydrogenolysis Activity for Polyethylene Upcycling. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202313174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.N.; Rorrer, J.E. Hydrogen-free catalytic depolymerization of waste polyolefins at mild temperatures. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2023, 338, 123071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machhi, D.J.; Modhera, B.; Parikh, P.A. Catalytic cracking of low-density polyethylene dissolved in various solvents: product distribution and coking behavior. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 3005–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

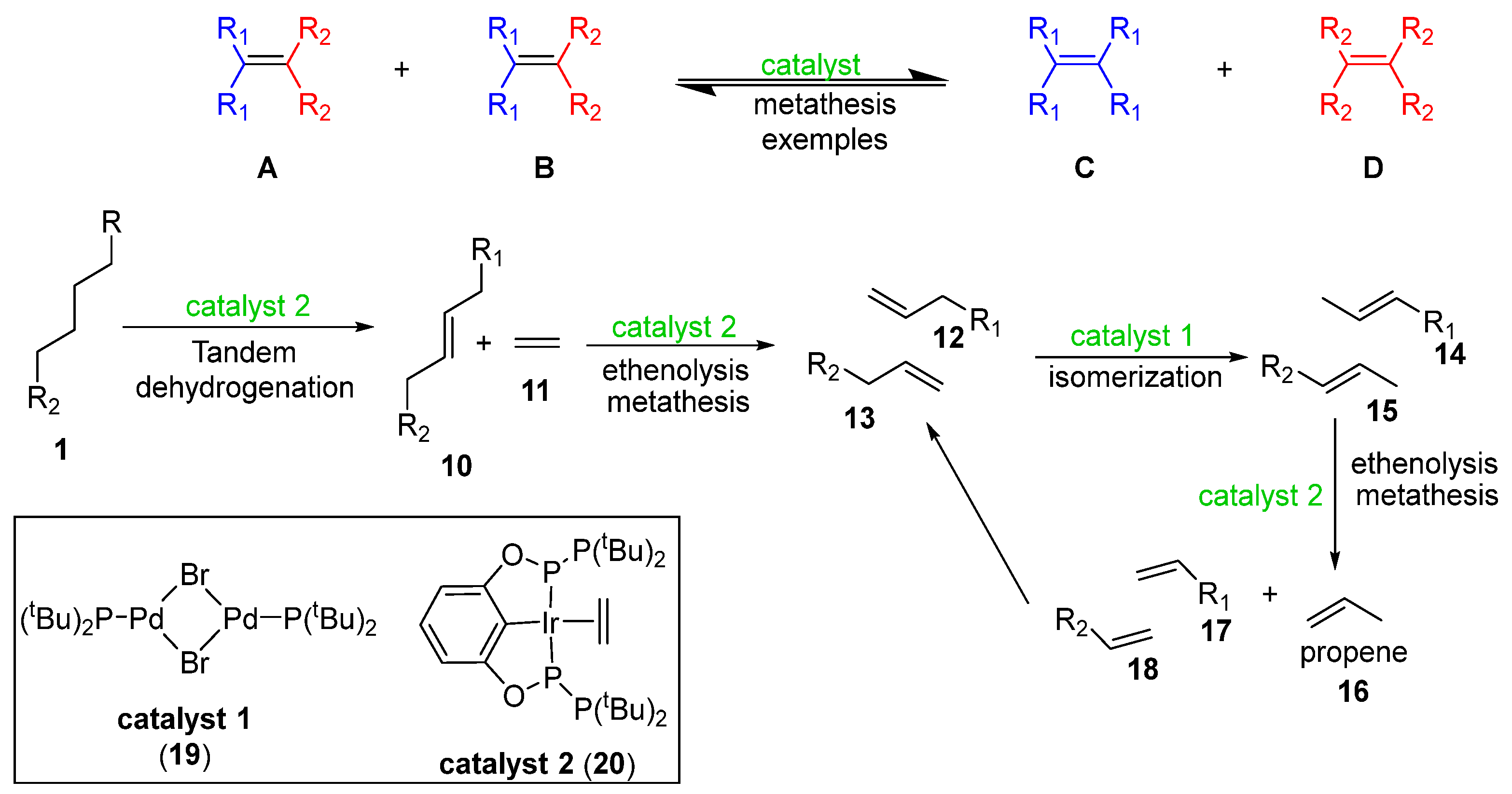

- Wang, N.M.; Strong, G.; DaSilva, V.; Gao, L.; Huacuja, R.; Konstantinov, I.A.; Rosen, M.S.; Nett, A.J.; Ewart, S.; Geyer, R.; Scott, S.L.; Guironnet, D. Chemical recycling of polyethylene by tandem catalytic conversion to propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 18526–18531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.F.; da Silva, F.C. Metátese em Síntese Orgânica e o Prêmio Nobel de Química de 2005 – Dos Plásticos à Indústria Farmacêutica. QNesc 2005, 22, 3–9. Available online: http://qnesc.sbq.org.br/online/qnesc22/a01.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

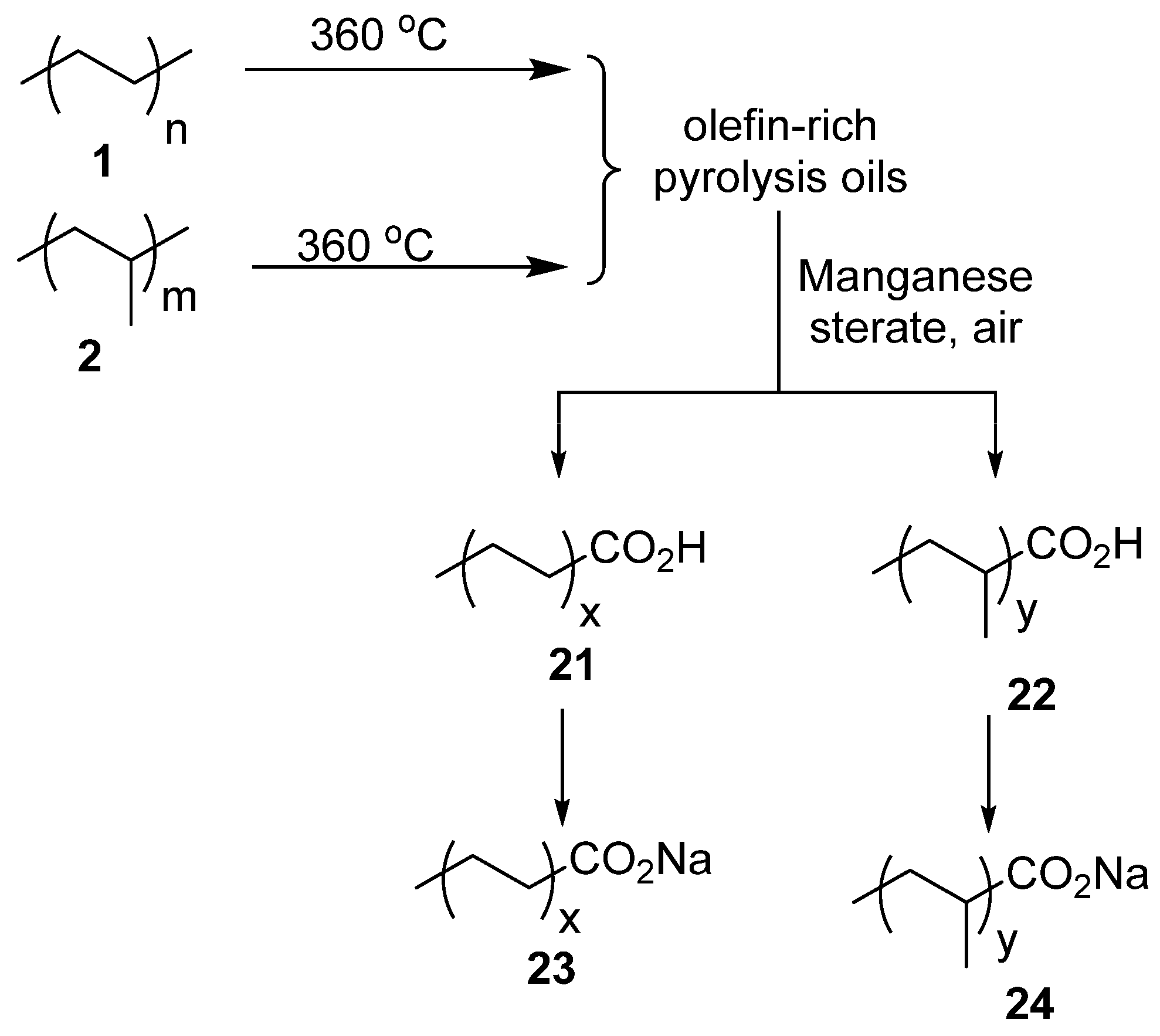

- 41 Xu, Z.; Munyaneza, N.E.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Posada, C.; Venturo, P.; Rorrer, N.A.; Miscall, J.; Sumpter, B.G.; Liu, G. Chemical upcycling of polyethylene, polypropylene, and mixtures to high-value surfactants. Science 2023, 381, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

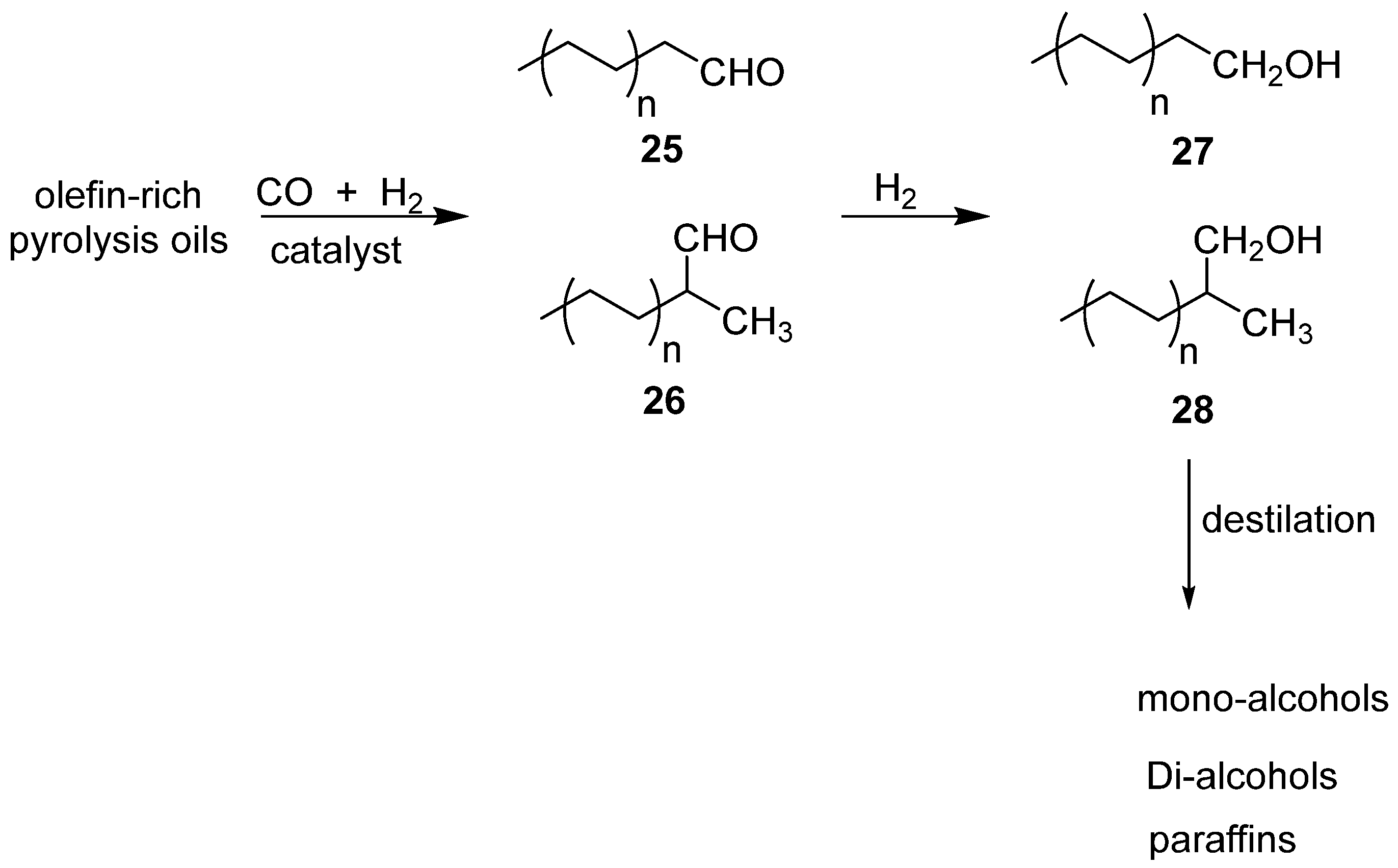

- Li, H.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, J.; Zavala, V.M.; Landis, C.R.; Mavrikakis, M.; Huber, G.W. Hydroformylation of pyrolysis oils to aldehydes and alcohols from polyolefin waste. Science 2023, 381, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, R.; Selent, D.; Börner, A. Applied Hydroformylation. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5675–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

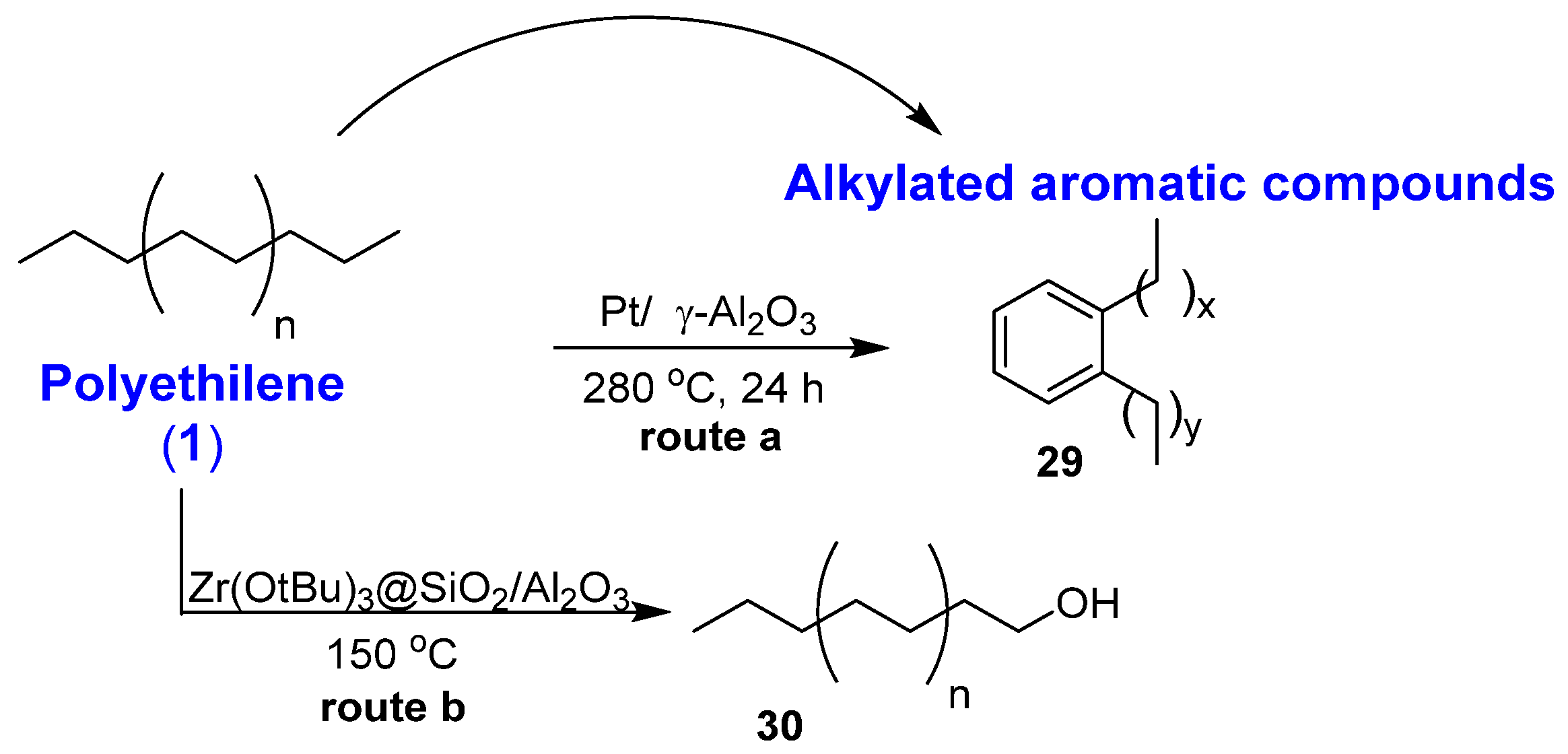

- Zhang, F.; Zeng, M.; Yappert, R.D.; Sun, J.; Lee, Y.-H.; LaPointe, A.M.; Peters, B.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Scott, S.L. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 2020, 370, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, U.; Paterson, A.L.; Rodriguez, J.; Kocen, A.L.; Yappert, R.; Hackler, R.A.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Peters, B.; Delferro, M.; LaPointe, A.M.; et al. Zirconium-Catalyzed C-H Alumination of Polyolefins, Paraffins, and Methane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2901–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, A.; Jaseer, E.A.; Barman, S.; Garcia, N. Review on Catalytic Depolymerization of Polyolefin Waste by Hydrogenolysis: State-of-the-Art and Outlook. Energy & Fuels 2024, 38, 1676–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, L.; Gu, J.; Yuan, H.; Chen, Y. Chemical recycling of plastic wastes via homogeneous catalysis: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiao, X.; Zhu, J.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y. Progress and perspective for conversion of plastic wastes into valuable chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, G.; Kennedy, R.M.; Hackler, R.A.; Ferrandon, M.; Tennakoon, A.; Patnaik, S.; LaPointe, A.M.; Ammal, S.C.; Heyden, A.; Perras, F.A.; et al. Upcycling Single-Use Polyethylene into High-Quality Liquid Products. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xie, T.; Kots, P.A.; Vance, B.C.; Yu, K.; Kumar, P.; Fu, J.; Liu, S.; Tsilomelekis, G.; Stach, E.A.; et al. Polyethylene Hydrogenolysis at Mild Conditions over Ruthenium on Tungstated Zirconia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 1, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaydev, S.D.; Martín, A.J.; Usteri, M.-E.; Chikri, K.; Eliasson, H.; Erni, R.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Consumer Grade Polyethylene Recycling via Hydrogenolysis on Ultrafine Supported Ruthenium Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorrer, J.E.; Troyano-Valls, C.; Beckham, G.T.; Román-Leshkov, Y. Hydrogenolysis of Polypropylene and Mixed Polyolefin Plastic Waste over Ru/C to Produce Liquid Alkanes. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 11661–11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang. K. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of plastic to liquid hydrocarbons over a nickel-based catalyst. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Chen, X.; Ling, Y.; Niu, T.; Guan, W.; Meng, J.; Hu, H.; Tsang, C.-W.; Liang, C. Hydrogenolysis-Isomerization of Waste Polyolefin Plastics to Multibranched Liquid Alkanes. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202202035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiao, X.; Zheng, K.; Shao, W.; Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y. Plastics-to-syngas photocatalysed by Co-Ga2O3 nanosheets. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Lu, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Pan, L.; Cai, R.; Lu, F. Ni-catalyzed carbon-carbon bonds cleavage of mixed polyolefin plastics waste. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 85, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Lou, X.; Zhang, C.; Cao, M.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Sham, T.-K.; et al. Site-Selective Polyolefin Hydrogenolysis on Atomic Ru for Methanation Suppression and Liquid Fuel Production. Research 2023, 6, 0032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomer, A.; Islam, M.M.; Bahri, M.; Inns, D.R.; Manning, T.D.; Claridge, J.B.; Browning, N.D.; Catlow, C.R.A.; Roldan, A.; Katsoulidis, A.P.; Rosseinsky, M.J. Enhanced production and control of liquid alkanes in the hydrogenolysis of polypropylene over shaped Ru/CeO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 2023, 666, 119431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, B.C.; Kots, P.A.; Wang, C.; Granite, J.E.; Vlachos, D.G. Ni/SiO2 catalysts for polyolefin deconstruction via the divergent hydrogenolysis mechanism. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2023, 322, 122138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, S.S.; Helmer, R.; Panicker, S.; Shetty, M. Investigation into the Reaction Pathways and Catalyst Deactivation for Polyethylene Hydrogenolysis over Silica-Supported Cobalt Catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 10142–10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K.E.; Peczak, I.L.; Kennedy, R.M.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Lin, J.; Wu, X.; Paterson, A.L.; Perras, F.A.; Hall, J.; Kropf, A.J.; et al. Synthesis of platinum nanoparticles on strontium titanate nanocuboids via surface organometallic grafting for the catalytic hydrogenolysis of plastic waste. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 1216–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Jahromi, H.; Roy, P.; Bhattarai, A.; Ammar, M.; Baltrusaitis, J.; Adhikari, S. Depolymerization of Household Plastic Waste via Catalytic Hydrothermal Liquefaction. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 13202–13217. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).