1. Introduction:

The development of nursing practice is considered a structure on which the processes that support health systems in the world are based. The permanence, commitment, and dedication of nurses in this scenario strengthen institutions to provide safe and quality care to people, families, and communities [

1]. Despite these considerations, in the nursing profession, there are tensions between the discourse of care and the development of professional practice in the field of the health system [

2] due to differences between the theory provided in the academic environment and the praxis in everyday life, where care professionals may encounter situations where their identity and the autonomy of their profession are questioned.

In nursing science, theory, practice, and research are mobilized and assembled to shape care processes. In the dynamics of these processes, theory illuminates practice, and practice is responsible for strengthening and enabling a process of theory validation that leads to the constitution of a relationship of continuous improvement in the nursing profession [

3].

In the health system field, there is a disparity between the theory taught in academic settings and its application in the professional practice of nursing. Limitations are seen due to different aspects that undermine the performance of nurses, a situation that generates challenges and limitations to establish care processes integrally with quality criteria [

2]. These disparities have been a cause for concern [

4] by establishing that the nursing habitus taught in the academy has restrictions to carry them out in the field of practice [

5], which leads to underestimating the cultural capital that nurses acquire specifically in the training process [

2]. Thus, cultural capital is influenced by power structures and expectations of health institutions that condition how care processes are established.

The disparities between theory and praxis development (academic habitus and professional habitus) in nursing limit the mobilization of the cultural capital of its professionals in everyday life by restricting their independence and job performance [

6], situations that lead to dissatisfaction, poor adaptation, as well as affectations in the personal identity of nurses. These situations imposed by the health field lead to a lack of recognition of the profession and limitations of the nursing role and tend to originate from the mobilization of discourses and practices from approaches that prioritize the economic-financial capital of health systems, which leads to work overload, limitations of autonomy and the strengthening of subordinate positions of professionals.

For this reason, it is important to critically analyze nurses' professional habitus in contrast to the power structures and capital relations that define their role in the field of health systems. In this way, we can obtain inputs for understanding these dynamics and propose actions to overcome the dissonances between theory and practice and strengthen nurses so that they practice their profession with greater autonomy and with the fullness of their cultural capital of care.

As a theoretical support, the research was approached from Bourdieu's theory of fields [

7]. This approach allows us to analyze how people's perceptions and practices are related and determined according to the social structures in which they are subsumed. Based on the understanding of the concepts of habitus, field, and capital, it is possible to analyze the logic of practices and relationships in social fields, as well as the practices that build and configure the current professional role.

The habitus category refers to internalized practices, that is, to the actions or behaviors that a person performs automatically because they are learned in social dynamics and define how one acts, perceives, and thinks according to the experiences and social processes that have shaped people over time. Capital refers to the resources that can generate power or advantages among people in a society; this is not limited exclusively to the economic aspect but involves cultural capital (education, skills), social (relationships), and symbolic (status, prestige). How capital is distributed defines the position of each person in society [

7]. Field refers to social scenarios where people and groups compete to achieve a type of capital and fight to reach a position of power that allows them to achieve their purposes.

In nursing practice, the dynamics of habitus, capital, and field are interpreted by the social group of health professionals, as well as the institutional and power dynamics that are mobilized in the health system field. In this context, nurses have been classified as an oppressed group that depends on the mobilization of practices of other professions to generate their care processes; this situation limits their autonomy [

8]. In this same sense, in health practice, the possession of cultural capital is configured according to institutional requirements such as academic qualifications, which determine the location of professionals in prominent profiles of the health field, where nursing professionals are usually found in a lower segment than other professionals, which generates, in many cases, relations of subordination, little authority, dependence and submission [

9]. These conditions affect nursing practices and contribute to generating a split between the theory and praxis of this discipline.

The research objective was to identify aspects that facilitate and limit the development of the theoretical component in nursing practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Particpants

The research was approached from a qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory study, with a critical hermeneutic approach from the interpretive paradigm [

10] that linked Bourdieu's field theory. This approach allows a deep and critical interpretation of people's cultural discourses and practices from understanding the meanings assigned to them by the research subjects, contrasted with social criticism to analyze the power structures and the ideologies that support them [

11].

Purposive theoretical sampling was used to select the participants [

12]. The number of participants in the study was established according to the scope of the information saturation point. The study was terminated when the data collection did not show new conceptual elements, categories, or relationships. The researchers carried out critical reflective analyses that led to considering, on the one hand, the density of the information and, on the other hand, the theoretical saturation.

Seventeen undergraduate nursing students (E), 11 nursing assistants with teaching assignments (EA), and six university professors (P) participated in the data collection process. Five groups of participants were formed (focus groups called pedagogical discussions) in which 31 people participated as follows: two pedagogical discussions with students (GF-E1 and GF-E2); two pedagogical discussions with nursing assistants (GF-EA1 and GF-EA2) and one pedagogical discussion with university professors (GFP). The focus groups had participants between five and eight. Thirty episodic interviews (ENT) were carried out.

To ensure the study's methodological rigor, the research process was developed by a group of nurses, professors, and researchers attached to the Universidad del Valle and belonging to the School of Nursing of the Faculty of Health. Their educational level is a doctorate in education, a doctorate in health, and a doctorate in anthropology; they also have training in master's degrees in education, epidemiology, and public health, respectively. Their academic career denotes experience in qualitative research. Two researchers are women, and two are men. Those who participated in the research were informed of the profiles of the researchers and knew of their interest in contributing to the generation of knowledge of the relationships between theory and practice in nursing.

The research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Valle, Colombia (act No. 151-016-21), declared minimal risk, and adopted the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [

13]. The participants gave their consent to participate in the research through a document that they read and signed describing the purpose of the study and the anonymity process to protect the information (use of codes).

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

Researchers collected data using three instruments: (a) a sociodemographic form, (b) episodic interviews [

14] and (c) focus groups. Interviews lasted, on average, 45 minutes, and focus groups 90 minutes. In the focus groups, the focused nature of the group allowed for a nuanced understanding of participants' perspectives and experiences [

15]. The sociodemographic form provided a basic profile of participants. With the consent of the participants, interviews and focus groups were recorded and then transcribed into Word® for primary data analysis. The lead author conducted a pilot interview beforehand to achieve clarity and consistency in the sequence of questions in the data collection instruments.

The analysis of the information linked a process of hermeneutic understanding based on the conceptual elements of the grounded theory of Strauss and Corbin [

16]. Reading each transcript of the episodic interviews and the pedagogical discussions incorporated a hermeneutic dialogue that allowed a comprehensive understanding of the data [

17]. The analysis had different levels of interpretation: on the one hand, the

contextualization corresponded to organizing and classifying the information in emptying matrices. On the other hand, the

categorization consists of the realization of theoretical codifications (according to pre-established categories from the theory) to identify emerging categories from the inductive codification during the analysis process. The

interpretative triangulation related to the construction of content according to the object of study [

14] and, finally, the

identification of the thematic nuclei formed according to the grouping of emerging categories.

In the analysis process, the researchers held periodic meetings to familiarize themselves with the information in the interviews and focus groups. The transcripts were coded and handed over to the researchers, who carefully avoided assigning interviews they had applied in the data collection process. Discussions were held about the main themes that emerged and the writing of the results. To represent the hermeneutic circle [

18], the dialectic between the findings that emerged and each interview was repeated from the second readings of the original transcripts, which were distributed evenly among the researchers. The authors agreed on the final primary and secondary categories to close the process.

The coding process was divided into three phases: open, axial, and selective [

16]. The researchers coded the data and identified meaning units as a whole; these units were then grouped into broader categories according to the woven relationships. From these inputs, emerging thematic cores were identified. The Atlas supported the analysis of the information. Ti 8.0 program and Bourdieu's field theory were used as an epistemological framework [

19]. In this theory, the author conceives society as a set of fields and social spaces with a certain autonomy where people compete for resources and recognition. It should be noted that each field establishes its own rules, values, and hierarchies where the subjects will position themselves, and it will be determined by the capital they possess, taking into account the concepts of habitus, field, and capital [

20].

3. Results

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Role |

Profession/gender |

Amount |

Age in years |

Level of training achieved |

Teaching experience (years) |

Teacher |

Nurse |

5 |

38-67 |

Master's degree (5)

PhD (1) |

10-30 |

| Nurse |

1 |

Nursing Assistant |

Nurse |

10 |

30-61 |

Specialization (5)

Master's degree (4)

PhD (1) |

3-27 |

| Nurse |

1 |

Students |

Women |

11 |

21-24 |

Baccalaureate |

None

|

| Man |

6 |

own elaboration

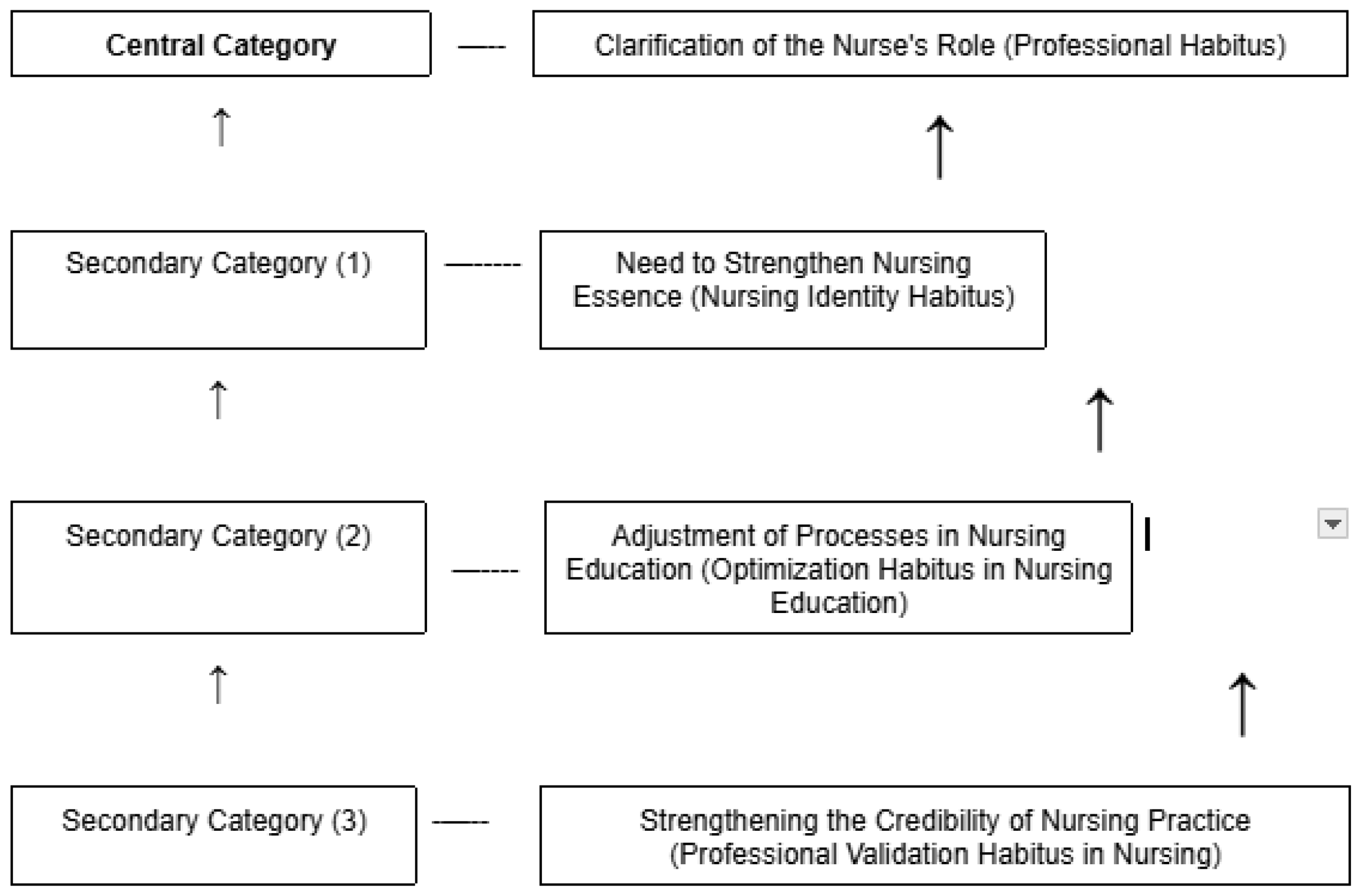

Figure 1.

Categories and subcategories that facilitate or limit the application of the theoretical component in nursing practice.

Figure 1.

Categories and subcategories that facilitate or limit the application of the theoretical component in nursing practice.

own elaboration

3.1. Core Category: Clarification of the Role of the Nurse (Professional Habitus)

According to the categorization process, professional habitus emerged as the central thematic core; the findings are described below according to the three emerging secondary categories.

3.2. Secondary Category: Need to Strengthen the Essence of Nursing (Habitus of the Nursing Identity)

3.2.1. Restrictions in the Definition of the Role of the Nurse

The nurses who participated in the research described that a good part of their professional practice is enforcing medical orders and carrying out administrative processes. These practices, to a large extent, have been determined by internalized dispositions that nurses have been involved in their social and work process ( habitus ) from their academic training and in the exercise of their professional practice. This habitus reveals the expectations of the field of the health system, as well as the hierarchical structures that are established in this field. Consequently, the cultural capital and social capital of nurses denote limitations, which originate from situations that prioritize the efficiency of the administrative process and obedience, restricting in some way professional autonomy and the approach to nursing from a critical thinking perspective.

The tension has more to do with the meaning of the role that we play in clinics, in institutions […] that has been socially believed, and that is the nurse who follows orders, checks, and is simply an administrative entity.

(GF-E1-006)

Another participant said:

The main tension arises from the possibility that I, as a teacher based on theory, must create critical thinking in the student; that is, the possibility that he has, with the theoretical bases, even if he has 70 patients, he must have the capacity to develop his role as a nurse, who is part of a multidisciplinary team and who has a voice and vote within the decisions that are made within the practice […] the main cause of the tension that exists between theory and practice is that we do not have a socially and politically defined role […].

(ENT-EA-002)

Teachers' and students' discourses reveal a restricted understanding of nursing professionals' roles, manifested by divergences in their contributions to society. This lack of clarity has implications for nurses' self-understanding and perception of their roles as the general population perceives them.

3.2.2. Limitation of the Recognition of Professional Nursing Knowledge

Participants pointed out that in the health system, where nurses carry out their professional practice and establish relationships with other health professionals, a power dynamic is observed based on their level of knowledge. In this context, nurses receive limited recognition for their knowledge from other members of the health team.

I think that power is given by knowledge […] Medicine continues to ignore nursing knowledge […] in that sense, they continue to feel like "the masters," and we want to penetrate. Still, there has also been a character of submission in us, which we have not been able to detach from that character of submission. They have a shield, and we have another shield. We have not established the sources of recognition […].

(GF-P-004)

On the other hand, the participating nurses expressed that nursing is continually compared to the medical profession. This comparison is based on the hegemonic biological and patriarchal discourse, which leads to the devaluation of the care processes that nursing mobilizes. This hegemonic discourse affects the relevance of the care processes and the perception of nursing in the social context and, therefore, the profession as a whole. One nurse expressed it this way:

Let's say that nursing as a field has its language, its codes, its own body of knowledge, and its ways of performing and producing a positive effect on society, but that is part of the hegemonic discourse, always comparing us with Medicine, in that comparison, there is a problem of devaluation of the nursing profession because they never compare us to say that we are better […], doctors are the best. However, we are different, although we have one element in common, which is the life of the subjects; each one has their field […], the hegemonic discourse is patriarchal, that is, it is from the "macho," it is not even from the masculine, it is from the man who has domination over the world […] so they do not value care, because they believe that it is innate to women, that it is domestic, there is a great distortion of the image of nursing […].

(ENT-P-002)

The participants' speeches emphasized that in health institutions, dominant positions are established mainly by male specialist doctors, stratified in upper middle classes and mature age, constituting a social hierarchy in the scenarios of the health system, while in lower segments of social stratification, there is a more significant presence of women, young people, people of low social stratification and mestizo and indigenous phenotypic characteristics.

3.2.3. Fight Against the Devaluation of the Nursing Profession in Health Services

The participating nurses highlighted the need to advocate against the devaluation of the nursing profession within the healthcare system. They believe this change must begin in academic settings, where they often perceive professors themselves drawing comparisons with the field of medical knowledge, distorting the distinct roles of the two professions. One participant expressed it this way:

Something that has bothered me since the first semester, which happens a lot here, especially in the first five semesters, is that they always compare us to Medicine in all the classes. Here, they tell us things like we are better than Medicine when, in reality, we are different. We are a team; we need each other.

(ENT-E-007)

3.2.4. Confusion of Roles Between Nursing Professionals and Technicians

The participants' accounts indicated that nursing is recognized in a limited way as a professional discipline. The habitus of nurses, shaped by their training and experiences, is in tension with the dominant habitus of other health professionals, and there is a tendency to confuse the role of the nursing professional with the work of the nursing technician.

One time, we were at a social gathering and met a group of doctor friends. Moreover, a doctor friend started to introduce us to a friend of his, and when he got to me, he stopped and stayed, no kidding, silent for 30 seconds, and I told him: I am a nurse, a university graduate.

(GF-P-007)

On the other hand, participants stated that the lack of recognition as a professional discipline means that nurses' roles, practices, and achievements in the health process are not distinguished. This leads to the symbolic and cultural capital of nurses needing to be valued to the same extent as the capital of other health professionals. This leads to an imbalance in capital distribution and promotes processes of invisibility of their roles, competencies, and contributions.

There is already a limitation because the doctor does not want to recognize the difference between a professional and a nursing assistant. When he says "nurse" to everyone […] they talk about the nurse, so I always have to tell him: but are you talking about the nursing assistant or the nurse of the service, to make him realize —no, I am talking about an assistant - ah! So, let us remember that they have different roles.

(ENT-P-002)

Another participant argues:

I have also felt that they think a nurse who is very confident and clear about things, well, "steps on their heels," so to speak, does not give her recognition. I experience this from my own experience because they always want to show off everything they do, but what the nurse does always needs to catch up. I managed much empowerment in this service, and we worked well as a team. Still, not all nurses can reach that level, so I include all those care actions to have a positive result for the patient, both from the medical and nursing point of view. They see it as very positive, and we articulate ourselves well, communicate, and work around it.

(ENT-EA-005)

Strengthening the essence of nursing

Supported by the nursing care process, participants recognize that strengthening professional development underlies the growth of nursing autonomy, supported by the essential actions of care offered comprehensively to people in their different dimensions, far from dependence on the social field of Medicine.

Nursing is a field that has to grow as the human being phenomenon grows to address other complexities, and we not only have to keep up with whether medical technology changes […] That is, the fields of nursing are all the fields that concern the condition of being human, which implies that we keep up with any knowledge, whether it be from the social sciences or biological sciences.

(GF-EA2-003)

A disturbing aspect described by the participants is that, although there has been progress in disciplinary knowledge of nursing, some academic training programs continue to concentrate their processes on biomedical content and limit subjects from humanistic and social epistemologies because they are considered to be of lesser relevance to the health training process.

3.3. Secondary Category: Process Adjustment in Nursing Training (Habitus of Optimization of Nursing Training)

3.3.1. Opening of Nursing Action Towards Different Knowledge Scenarios

The participants' stories reflect the need for nursing professionals to establish specific fields of work and, in this sense, manage to move away from the hegemonic discourse mobilized by medical specialties. One participant described it as follows:

Beyond the medical specialty, I believe we have to think about the phenomena that concern us […] right now; for example, there is an important role in nursing care for coexistence for peace. What are we going to do about that? That generates new tools and the demand to investigate and think about ourselves in a social production of health. In Latin America, we have made many gains in understanding how our communities have developed in the inequitable relationships that have led to suffering and the conditions we have today. Nursing cannot continue to be alien to this knowledge.

(GF-EA1-006)

3.3.2. Need for Adjustment of Nursing Training Processes

Nurses describe the need to adjust nursing academic program settings to categorically establish the roles that characterize the discipline. One participant expressed it this way:

It is up to us to find out what I am looking for when I provide care. I want to grow in providing better care, taking into account the patient's needs at that moment, and I have more power when I can satisfy the needs of the overwhelmed person. That is why the humanization part is very well done.

(GF-E1-009)

Another participant argued:

It is not that because of the doctor's diagnoses, we have different ways of seeing our practice. He is made to diagnose, so what is the hegemony? I am made to care; if I am doing well what I am supposed to do, there is no problem there. It is my responsibility to care as a nurse, which is my discipline: caring. That should interest us and what we have to teach our students […] I believe that we have to create another form of education.

(ENT-P-004)

3.3.3. Hard Work to Position Nursing as a Relevant Health Profession

The participants' stories show that nursing can achieve a high professional level like other disciplines, as long as effort and dedication are strengthened by strengthening the care process.

I have had the opportunity to be in different roles; I have even been on the boards. I am the only nurse who has had that opportunity here in the institution, but much to my regret, that opportunity is increasingly being lost. I feel that this is part of our responsibility because if I had had recognition, it is also because many have perceived my work as a nurse, or else, I would not have gotten there […] In most cases, we assume roles of convenience, and there is no dedication.

(ENT-EA-005)

3.4. Secondary Category: Strengthening the Credibility of Nursing Actions (Habitus of Professional Validation in Nursing)

3.4.1. Restrictions on Professional Credibility

Nursing students participating in the research described that during their training process, some professors do not provide them with input that would lead them to strengthen the credibility of the profession. One student mentioned:

We have teachers who do not value their profession, so, for example, I am writing my notes, and I want to make a nursing diagnosis related to the fact that the patient has an alteration in gas exchange. Hence, the teacher comes and tells someone: - That thing about gas exchange is from respiratory therapy, so don't go there, take it away -, and that thing about arterial blood gases? Did you analyze them? Or did you see that the doctors did it, and you copied it? -.

(GF-E2-002)

3.4.2. Designations that Distort Professional Practice

According to the participants, one aspect that limits nurses in developing their professional practice is their labeling as "bosses;" this denomination leads to professionals being associated more with administrative functions than with direct care actions.

I think it weighs heavily on us, and we must continue fighting against that view of being bosses because it is a view of the military that gives orders. Nursing leadership has to go beyond a power relationship because, often, having a staff member in charge as an auxiliary seems to be the status that we socially seek, which is different. (GF-EA1-010)

3.4.3. Limited Collaboration Between Nursing Professionals

Participants point to the need for more collaboration between nursing professionals as a limitation in strengthening the discipline.

It has to do with what we reflect from the training with the students; if a colleague does not do well with the students, how many of us are willing to ask her: what is happening? How do we support you? […] We are always in the sense of "competition," of saying, you are good, you are bad, and then, if we ourselves, as in the teaching exercise, are not supportive of the other, we are impregnating that same thing in our students.

(ENT-EA-008)

3.4.4. Restrictions on Participation in Associations of Nursing Professionals

Participants reported restrictions in strengthening nursing leadership, both in academia and in the workplace. In these settings, participation in nursing associations is weakened, limiting nursing action from associations that allow for political influence in improving the disciplinary foundations of the profession.

I am still determining the role the ANEC (National Association of Nurses of Colombia) union plays. I think there should also be, I do not know, a redefinition, a collective construction, or something that leads us to think about and build a different union […]. If we lack it, perhaps some external help from these organizations can strengthen our leadership.

(ENT-EA-008)

In the information analysis process, 275 codes emerged. From this coding, a main thematic core (central category) emerged, called

clarification of the nurse's role (professional habitus). Likewise, three secondary thematic cores emerged (secondary categories), called

the need to strengthen the nursing essence (habitus of nursing identity),

adjustment of processes in nursing training (habitus of optimization of nursing training), and, finally,

strengthening the credibility of nursing actions (habitus of professional validation in nursing) (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

Identifying aspects that facilitate and/or limit the development of the theoretical component in nursing practice is a challenge in the health system. Different challenges arise for patients to achieve optimal performance in carrying out their professional practice, determined by habitus, field, and capital.

The perception of nurses about the performance of their professional role and their

habitus in the health system field is influenced by their experience in academic training and work history. These aspects constitute a crucial resource in defining the capacity to mobilize the cultural, symbolic, and social capital of nursing in the health field. The research reveals effects on the professional performance of nurses due to an unclear definition of their professional role, aspects that coincide with previous studies [

8] where this situation leads to a devaluation of the symbolic and cultural capital [

21] that nurses have built.

On the other hand, authors [

22] have addressed this challenge in the educational process and describe nursing undergraduate applicants. However, they have broad expectations to base themselves on the scientific field, and their level of satisfaction is restricted due to the challenges they encounter in the practice of their professional exercise [

23]. This low satisfaction is explained by the limited clarification of the professional role of care in the health field, which in some way restricts the accumulation of symbolic nursing capital and the consolidation of a position within that social field.

One of the elements that influence the position of nurses in the health system field refers to the feminization of the profession. This aspect is supported by Connell [

24] when describing that the activities and practices that women carry out in different scenarios of the social field of health are relegated to positions of lesser power. This situation affects the nursing discipline if one considers that a good part of its professionals belong to the female gender. This type of sexism produces unequal gender relations, where men as a dominant group tend to generate subordination to women through the mobilization of discourses and practices that denote superiority, which leads to unfair differences that are legitimized within the social field of health and its origin comes mainly from a devaluation of the care process.

The participants argue that the nursing profession is perceived as having a subordinate identity that limits its autonomy in the exercise of care processes. This coincides with Moya et al. [

8], who affirm that the nursing profession, in its historical trajectory, has been perceived as a discipline where its professionals tend to incorporate subordinate positions. This occurs by categorically linking discursive elements with a solid biomedical, Euclidean, and positivist content in the

habitus of the profession that favors monocentric processes, undermining the sovereignty of nursing developments from the logic of humanized care.

The educational process in nursing plays a preponderant role in forming nurses' cultural and symbolic capital and defining their

habitus [

22]. It has been reported that in this scenario, dependency practices are replicated, which limits the discipline's autonomy [

25]. This issue should draw attention to current nursing students' training projections to establish the pedagogical structures that allow nursing to be emancipated from the discourses that subordinate it and lead it to assume a role of obedience.

Some models, such as "Banking Education," are examples of academic processes that encourage the perpetuation of dependency practices that limit the construction of a critical cultural capital in nursing, restricting the possibility of transforming the social field of the health system. This model is dedicated to transmitting knowledge and leaves aside the mobilization of reflexive processes that lead to criticizing the normality established in the power structures that are mobilized in the hierarchies of the health field [

26]. On the other hand, these models encourage the fragmentation of education, discarding the dynamics of the social context where realities are expressed [

27]. This situation leads to dissatisfaction in the training process by upsetting the concordance between theory and practice.

By establishing a fragmented academic practice [

28], the theoretical components suffer damages that attenuate the recognition of the holistic nature of the scenarios where life is lived, mainly if it is focused on a positivist habitus. It is precisely the fragmentation that imposes difficulties in contextualizing the challenges in health and care, limiting the possibility of understanding the meanings underlying cultural capital accumulation in nursing. However, the logic of a positivist habitus in the mobilization of care actions in the field of the health system not only leads to a devaluation of the principles of the nursing process but also reduces people to subjects that are part of a quantifiable process, which implies giving priority to the establishment of economic capital within the social health field, with severe effects on the humanism that is part of the cultural and symbolic capital of nurses [

29].

In the study, nurses perceived that in the social field where they work, there are persistent accusations from other health professionals about a limited recognition of nursing as a profession, its scope, and its roles. These findings coincide with other authors [

30], who show that the limited way of recognizing the nursing profession and its symbolic value subjects the discipline to subordination. This situation challenges the exercise of autonomous nursing that can consolidate symbolic capital within the health system field [

31], which has been permeated by an imposing biomedical prestige. In the context of the health field, the nursing role, in addition to being recognized in a limited way, is not allowed to advance and progress due to the actions of other actors in the field, who have greater power and symbolic capital [

32].

Transforming this situation that subsumes the nursing discipline in a field of knowledge with pragmatic limitations that begins from academic training requires the promotion of a critical-reflective habitus in nursing [

33] aimed at questioning the established power logics that inhabit the field of health systems in order to build processes that establish relevant symbolic and cultural capitals to achieve greater recognition and autonomy in the nursing discipline [

34]. This requires adjustments to traditional educational models, whose approach should be strengthened from the essence of care and declare resistance to administrative and bureaucratic dynamics that have somehow impacted the establishment of the cultural capital of care professionals.

As a limitation of the research, it is reported that the study was carried out on a group of nurses and nursing students in Colombia so that the stories and experiences discussed refer to a situated context. In order to obtain generalizable information, it is recommended that other scenarios be linked to the analysis and that the sample of participants be increased.

5. Conclusions

The research reveals that different elements of the social field of the health system shape the professional habitus of nursing professionals. This field is repressed by hierarchical structures that succeed in disconnecting theory from praxis. Aspects such as subordination to the hegemonic biological discourse and the medical profession, the limited appreciation of humanized care, restrictions on the recognition of the nursing process by health institutions, and limited solidarity and leadership end up conditioning the accumulation of symbolic capital and social capital of nursing, which leads to the loss of autonomy and the advancement of professional development.

To mitigate the gap between theory and practice in nursing, it is necessary to strengthen a critical nursing professional habitus that reflects from the social field of academia the imperative need to strengthen the role of nursing. On the other hand, it is necessary to strengthen the leadership of nursing associations, as well as to promote collaboration between nurses, in order to manage favorable work scenarios that involve a complete care process that values and respects autonomy, specific knowledge, and appreciation of the cultural capital of the nursing discipline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and CIAG); methodology L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and (CIAG); formal analysis (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and CIAG); investigation (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and, and CIAG); data curation (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and and CIAG); writing—original draft (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and CIAG); writing—review and editing (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and and CIAG); visualization (L.E.P.S,L.C.M.V,J.S.D and); supervision ( CIAG); project administration (L.E.P.S, L.C.M.V and J.S.D ). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee on Human Ethics (CIREH) of the Faculty of Health of the Universidad del Valle, according to act No. 151-016-21

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was written following the recommendations of the COREQ guide for qualitative research reporting (Tong, 2007).

Use of Artificial Intelligence

ChatGPT4O and Grammarly has been used for language translation, language and grammar editing

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Griffiths, P. , Recio-Saucedo, A., Dall'Ora, C., Briggs J., Maruotti A., Meredith P., Smith G. B. y Ball J. (2018). The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: A systematic review. Journal of advanced nursing, 74(7), 1474–1487. [CrossRef]

- Greenway, K. , Butt, G. y Walthall, H. (2019). What is a theory-practice gap? An exploration of the concept. Nurse education in practice, 34, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Safazadeh, S. , Irajpour, A., Alimohammadi, N. y Haghani, F. (2018). Exploring the reasons for theory-practice gap in emergency nursing education: A qualitative research. Journal of education and health promotion, 7, 132. [CrossRef]

- Aimei, M. (2015). The gap of nursing theory and nursing practice: Is it too wide to bridge? An example from Macau. Macau Journal of Nursing, 14(1), 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Salah, A. , Aljerjawy, M. y Salama, A. (2018). Gap between theory and practice in the nursing education: The role of clinical setting. JOJ Nurse Health Care, 7 (2), 555707. [CrossRef]

- Woo, B. , Zhou, W., Lim, T. y Tam, W. (2019). Practice patterns and role perception of advanced practice nurses: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Journal of nursing management, 27(5), 992–1004. [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (2007a). El sentido práctico. Madrid: Siglo XXI. 103 p.

- Moya, J. , Backes, V., Prado, M.y Sandin, M. (2010). La enfermería como grupo oprimido: las voces de los protagonistas. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem, 19 (4), 609–617. [CrossRef]

- Rouhi-Balasi, L. , Elahi, N., Ebadi, A., Jahani, S. y Hazrati, M. (2020). Professional Autonomy of Nurses: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis Study. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research, 25(4), 273–281. [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. (1987). The theory of communicative action. The critique of functionalist reason. Beacon.

- Dilthey, W. , Simmel, G., Weber, M., Freud, S., Cassirer, E. y Mannheim, K. (2003). The interpretative tradition. In: Delanty G, Strydom P, editors. Philosophies of social science: the classic and contemporary readings, part two. Maidenhead, Philadelphia: Open University Press; p. 85–206.

- Albine, M. y Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Prac. ;24(1): 9-18. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20): 2191-4. [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2002). Qualitative Sozialforschung. In: Eine Einführung. 6th ed. Reinbek (Hamburg): Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Krueger, R y Casey, M. (2015). Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 5. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Strauss, A y Corbin, J. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Binding, L. , y Tapp, D. (2008). Human understanding in dialogue: Gadamer's recovery of the genuine. Nursing Philosophy, 9(2), 121-130.

- Debesay, J. , Nåden, D. y Slettebø, A. (2008). How do we close the hermeneutic circle? A Gadamerian approach to justification in interpretation in qualitative studies. Nursing inquiry, 15(1), 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Rhynas, S. (2005). Bourdieu's theory of practice and its potential in nursing research. Journal of advanced nursing, 50(2), 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (2007b). Razones prácticas: sobre la teoría de la acción. 4a ed. Barcelona: Anagrama. 193 p.

- Ajani, K. y Moez, S. (2011). Gap between knowledge and practice in nursing. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 15:3927–3931. [CrossRef]

- Falk, K. , Falk, H. y Jakobsson, E. (2016). When practice precedes theory - A mixed methods evaluation of students' learning experiences in an undergraduate study program in nursing. Nurse education in practice, 16(1), 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, F. (2008). De la práctica de la enfermería a la teoría enfermera: Concepciones presentes en el ejercicio profesional. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Alcalá.

- Connell, R. (2012). Gender, health and theory: conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Social science & medicine, 74(11), 1675–1683. [CrossRef]

- Zohoorparvandeh, V. , Farrokhfall, K., Ahmadi, M. y Dashtgard, A. (2018). Investigating factors affecting the gap of nursing education and practice from students and instructors’ viewpoints. Future of Medical Education Journal, 8(3), 42-46. [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, P. , Özmen, G., Yavuz, M., Koçan, S. y Çilingir, D. (2023). Exploration of nursing students' views on the theory-practice gap in surgical nursing education and its relationship with attitudes towards the profession and evidence-based practice. Nurse education in practice, 69, 103624. [CrossRef]

- Varona, F. (2020). Ideas educacionales de Paulo Freire. Reflexiones desde la educación superior. MediSur, 18(2), 233-243. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1727-897X2020000200233&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Moya, J. , y Parra, S. (2006). La enseñanza de la enfermería como una práctica reflexiva. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem, 15 (2), 303–311. [CrossRef]

- Cruz Riveros, Consuelo. (2020). La naturaleza del cuidado humanizado. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados, 9(1), 21-32. Epub 01 de junio de 2020. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, S. y Cacante, J. (2020). El concepto de Reconocimiento y su utilidad para el campo de la Enfermería. Temperamentvm, 16, e12797. http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1699-60112020000100019&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Pierrotti, V. , Guirardello, E. y Toledo, V. (2020). Patrones de conocimiento de enfermería: la imagen y el papel de las enfermeras en la sociedad percibidos por los estudiantes. Revista Brasileira De Enfermagem, 73 (4), e20180959. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020). State of the World’s Nursing Report - 2020. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279.

- Estrada, K. (2019). Pensamiento crítico: concepto y su importancia en la educación en Enfermería. Index de Enfermería, 28(4), 204-208. http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962019000300009&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Sankar, M. (2024). Decolonisation of the nursing curriculum: an evidence-based perspective. Evidence-based nursing, ebnurs-2024-104180. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).