Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

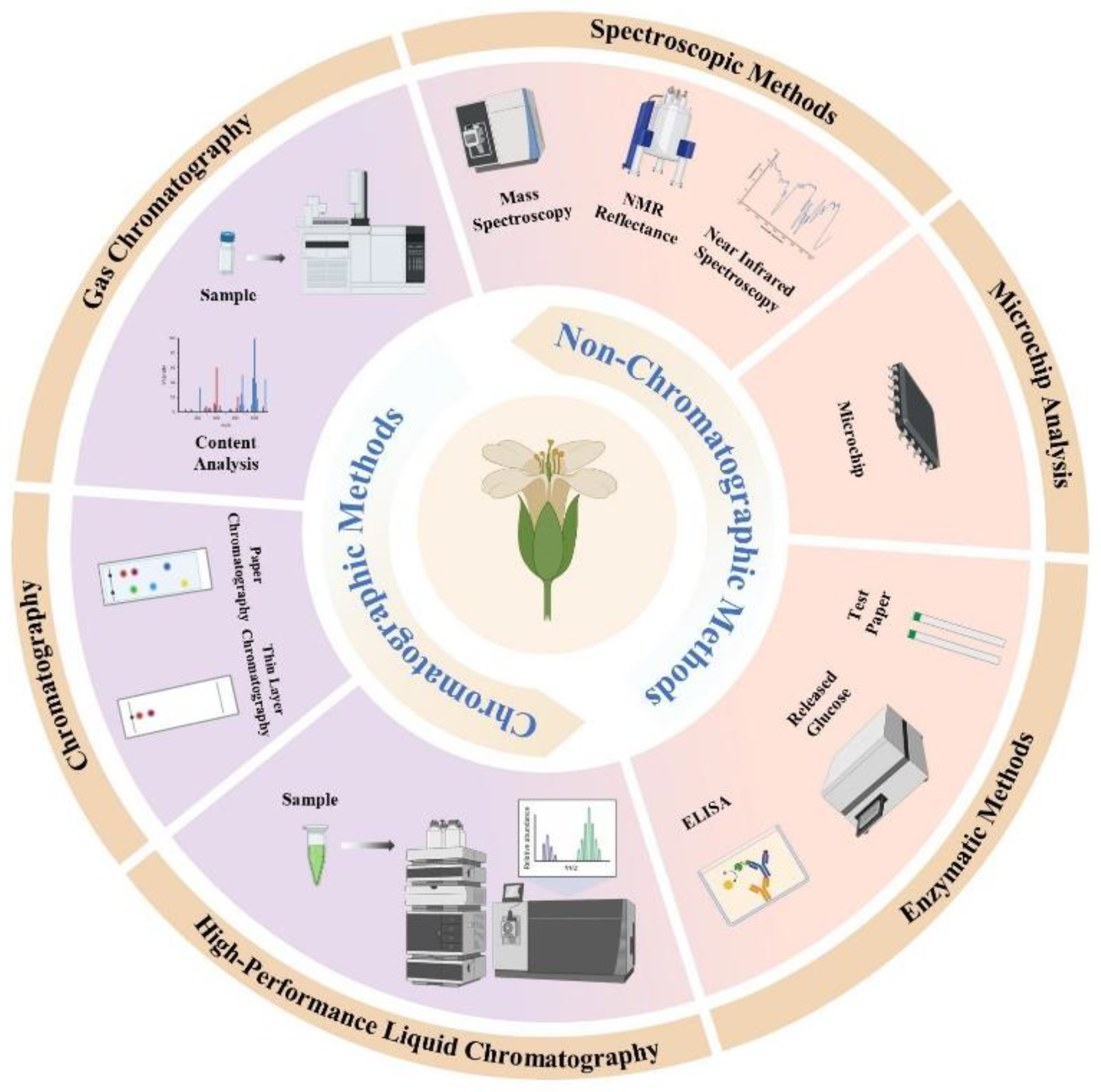

2. Analytical Techniques for the Detection of Glucosinolates

2.1. HPLC

2.2. LC-MS

2.3. ELISA

3. Sample Preparation, Extraction, and Quantification

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. Extraction

3.3. Quantification

| Family | Species | Tissues and organs | GSLs compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brassicaceae | Brassica napus | Seed, leaves, stems, roots | 6-15 |

| Brassica juncea | 7-17 | ||

| Capsella bursa - pastoris (L.) Medic. | 3-7 | ||

| Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis L. | 4-9 | ||

| Brassica rapa | 2-11 | ||

| Brassica carinata A Braun | Seed, leaves, stems | 3-8 | |

| Camelina sativa | 3-12 | ||

| Camelina rumelica subsp. rumelica | |||

| Camelina macrocarpa | |||

| Brassica oleracea L. var capitata | Seeds, leaves | 3-12 | |

| Brassica oleracea L. convar capitata var alba | Florets, seedlings | 3-14 | |

| Brassica oleracea L. var italica | Seed, leaves, stems, roots, seedlings | 7-16 | |

| Raphannus sativus L. | Roots, seeds | 6-14 | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Leaf, florets, flowers, seedlings | 3-23 |

4. Standardization and Validation of Glucosinolate Detection Methods

4.1. Standardization

4.2. Validation

5. Future Prospects

5.1. Development of New Analytical Techniques

5.2. Miniaturization and Automation

5.3. Application of Machine Learning(ML) and Artificial Intelligence

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamal, R.M.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Mohd Sukri, N.S.; Perimal, E.K.; Ahmad, H.; Patrick, R.; Djedaini-Pilard, F.; Mazzon, E.; Rigaud, S. Beneficial health effects of glucosinolates-derived isothiocyanates on cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Stewart, J.; Lopez, M.; Ioannou, I.; Allais, F. Glucosinolates: Natural occurrence, biosynthesis, accessibility, isolation, structures, and biological activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, M.-J.; Yeh, M.-C.; Tsai, M.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-L.; Wang, C.-J.; Huang, H.-P. Glucosinolates Extracts from Brassica juncea Ameliorate HFD-Induced Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta-Duch, J.; Kopec, A.; Piatkowska, E.; Borczak, B.; Leszczynska, T. The beneficial effects of Brassica vegetables on human health. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny 2012, 63. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton, S.; Marks, G. Development of a food composition database for the estimation of dietary intakes of glucosinolates, the biologically active constituents of cruciferous vegetables. British Journal of Nutrition 2003, 90, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šamec, D.; Urlić, B.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) as a superfood: Review of the scientific evidence behind the statement. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2019, 59, 2411–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanduchova, A.; Anzenbacher, P.; Anzenbacherova, E. Isothiocyanate from broccoli, sulforaphane, and its properties. Journal of medicinal food 2019, 22, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Yang, J.; He, Y.; Zhu, Z. Bioactive compounds in cruciferous sprouts and microgreens and the effects of sulfur nutrition. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2023, 103, 7323–7332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, E.L.; Sim, M.; Travica, N.; Marx, W.; Beasy, G.; Lynch, G.S.; Bondonno, C.P.; Lewis, J.R.; Hodgson, J.M.; Blekkenhorst, L.C. Glucosinolates from cruciferous vegetables and their potential role in chronic disease: Investigating the preclinical and clinical evidence. Frontiers in pharmacology 2021, 12, 767975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, M. Mechanisms underlying biological effects of cruciferous glucosinolate-derived isothiocyanates/indoles: a focus on metabolic syndrome. Frontiers in Nutrition 2020, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Cheung, C.-Y.; Ma, W.-T.; Au, W.-M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Lee, A. Determination of two intact glucosinolates in vegetables and Chinese herbs. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2004, 378, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higdon, J.V.; Delage, B.; Williams, D.E.; Dashwood, R.H. Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis. Pharmacological research 2007, 55, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennelley, G.E.; Amaye-Obu, T.; Foster, B.A.; Tang, L.; Paragh, G.; Huss, W.J. Mechanistic review of sulforaphane as a chemoprotective agent in bladder cancer. American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Urology 2023, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, T.A.; Fahey, J.W.; Wade, K.L.; Stephenson, K.K.; Talalay, P. Human metabolism and excretion of cancer chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of cruciferous vegetables. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 1998, 7, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Melim, C.; Lauro, M.R.; Pires, I.M.; Oliveira, P.J.; Cabral, C. The role of glucosinolates from cruciferous vegetables (Brassicaceae) in gastrointestinal cancers: from prevention to therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Chandran, D.; Zidan, B.R.M.; Das, R.; Mamada, S.S.; Masyita, A.; Salampe, M.; Nainu, F.; Khandaker, M.U. Cruciferous vegetables as a treasure of functional foods bioactive compounds: Targeting p53 family in gastrointestinal tract and associated cancers. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 951935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.-Q.; Mo, X.-F.; Lin, F.-Y.; Zhan, X.-X.; Feng, X.-L.; Zhang, X.; Luo, H.; Zhang, C.-X. Intake of total cruciferous vegetable and its contents of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates, glutathione S-transferases polymorphisms and breast cancer risk: a case–control study in China. British Journal of Nutrition 2020, 124, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almushayti, A.Y.; Brandt, K.; Carroll, M.A.; Scotter, M.J. Current analytical methods for determination of glucosinolates in vegetables and human tissues. Journal of Chromatography A 2021, 1643, 462060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liang, H.; Yuan, Q.; Hong, Y. Determination of glucosinolates in 19 Chinese medicinal plants with spectrophotometry and high-pressure liquid chromatography. Natural product research 2010, 24, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Li, W.; Gao, R.; Yan, L.; Wang, P.; Gu, Z.; Yang, R. Determination of glucosinolates in rapeseed meal and their degradation by myrosinase from rapeseed sprouts. Food chemistry 2022, 382, 132316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; He, H.; Zhao, X.; Liu, G.; Hu, L.; Cheng, B.; Wang, Y. Determination of 18 intact glucosinolates in Brassicaceae vegetables by UHPLC-MS/MS: comparing tissue disruption methods for sample preparation. Molecules 2021, 27, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.-M.; Xu, X.-X.; Bian, L.; Luo, Z.-X.; Chen, Z.-M. Measurement of volatile plant compounds in field ambient air by thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2015, 407, 9105–9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagar, R.; Gautam, A.; Priscilla, K.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, R. Sample Preparation from Plant Tissue for Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) we. In Plant Functional Genomics: Methods and Protocols, Volume 2; Springer: 2024; pp. 19-37.

- Mukker, J.K.; Kotlyarova, V.; Singh, R.S.P.; Alcorn, J. HPLC method with fluorescence detection for the quantitative determination of flaxseed lignans. Journal of Chromatography B 2010, 878, 3076–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, A.; Tamasi, G.; De Rocco, F.; Bonechi, C.; Consumi, M.; Leone, G.; Magnani, A.; Rossi, C. Kinetics of glucosinolate hydrolysis by myrosinase in Brassicaceae tissues: A high-performance liquid chromatography approach. Food Chemistry 2021, 355, 129634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Yang, J.; Dang, Y.-M.; Ha, J.-H. Effect of fermentation stages on glucosinolate profiles in kimchi: Quantification of 14 intact glucosinolates using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry: X 2022, 15, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; La Barbera, G.; Montone, C.M.; Piovesana, S.; Chiozzi, R.Z.; Laganà, A. Chromatographic column evaluation for the untargeted profiling of glucosinolates in cauliflower by means of ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry. Talanta 2018, 179, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, J.; Xiao, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Q. An integrated analytical approach based on enhanced fragment ions interrogation and modified Kendrick mass defect filter data mining for in-depth chemical profiling of glucosinolates by ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap high resolution mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2021, 1639, 461903. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, P. GLS-finder: a platform for fast profiling of glucosinolates in Brassica vegetables. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2016, 64, 4407–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Sumner, B.W.; Bhatia, A.; Sarma, S.J.; Sumner, L.W. UHPLC-MS analyses of plant flavonoids. Current protocols in plant biology 2019, 4, e20085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocniak, L.E.; Elkin, K.R.; Dillard, S.L.; Bryant, R.B.; Soder, K.J. Building comprehensive glucosinolate profiles for brassica varieties. Talanta 2023, 251, 123814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Wagstaff, C. Identification and quantification of glucosinolate and flavonol compounds in rocket salad (Eruca sativa, Eruca vesicaria and Diplotaxis tenuifolia) by LC–MS: Highlighting the potential for improving nutritional value of rocket crops. Food Chemistry 2015, 172, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, R.M.; Eltanany, B.M.; Pont, L.; Benavente, F.; ElBanna, S.A.; Otify, A.M. Unveiling the functional components and antivirulence activity of mustard leaves using an LC-MS/MS, molecular networking, and multivariate data analysis integrated approach. Food Research International 2023, 168, 112742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Reichelt, M.; Bisht, N.C. An LC-MS/MS assay for enzymatic characterization of methylthioalkylmalate synthase (MAMS) involved in glucosinolate biosynthesis. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: 2022; Volume 676, pp. 49-69.

- Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, D.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Z. Analysis of processing effects on glucosinolate profiles in red cabbage by LC-MS/MS in multiple reaction monitoring mode. Molecules 2021, 26, 5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongkitwitoon, B.; Sakamoto, S.; Tanaka, H.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Kinjo, J.; Morimoto, S.; Putalun, W. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for total isoflavonoids in Pueraria candollei using anti-puerarin and anti-daidzin polyclonal antibodies. Planta medica 2010, 76, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, S.; Putalun, W.; Vimolmangkang, S.; Phoolcharoen, W.; Shoyama, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Morimoto, S. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the quantitative/qualitative analysis of plant secondary metabolites. Journal of natural medicines 2018, 72, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hidalgo, I.; Moreno, D.A.; García-Viguera, C.; Ros-García, J.M. Effect of industrial freezing on the physical and nutritional quality traits in broccoli. Food Science and Technology International 2019, 25, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doheny-Adams, T.; Redeker, K.; Kittipol, V.; Bancroft, I.; Hartley, S.E. Development of an efficient glucosinolate extraction method. Plant methods 2017, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, N.; Prekalj, B.; Perković, J.; Ban, D.; Užila, Z.; Ban, S.G. The Effect of Different Extraction Protocols on Brassica olerace a var. acephala Antioxidant Activity, Bioactive Compounds, and Sugar Profile. Plants 2020, 9, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Požrl, T.; Cigić, B.; Demšar, L.; Hribar, J.; Polak, T. Mechanical Stress Results in Immediate Accumulation of Glucosinolates in Fresh-Cut Cabbage. Journal of Chemistry 2015, 2015, 963034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-H.; Huang, J.-W.; Kumar, P.V.; Jen, J.-F. Determination of sinigrin in vegetable seeds by online microdialysis sampling coupled to reverse-phase ion-pair liquid chromatography. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2010, 58, 4571–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, K.; van Dam, N.M. A straightforward method for glucosinolate extraction and analysis with high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 2017, e55425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chastain, J.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, H.H.; Iassonova, D.; Rivest, J.; You, H. Eco-efficient quantification of glucosinolates in camelina seed, oil, and defatted meal: optimization, development, and validation of a UPLC-DAD Method. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citeau, M.; Regis, J.; Carré, P.; Fine, F. Value of hydroalcoholic treatment of rapeseed for oil extraction and protein enrichment. Ocl 2019, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.M.K.; Akanbi, T.O.; Kirkman, T.; Nguyen, M.H.; Vuong, Q.V. Recovery of phenolic compounds and antioxidants from coffee pulp (Coffea canephora) waste using ultrasound and microwave-assisted extraction. Processes 2022, 10, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabrauskiene, J.; Marksa, M.; Ivanauskas, L.; Bernatoniene, J. Optimization of naringin and naringenin extraction from Citrus× paradisi L. using hydrolysis and excipients as adsorbent. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Trandafir, I.; Cosmulescu, S. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted hydroalcoholic extraction of phenolic compounds from walnut leaves using response surface methodology. Pharmaceutical biology 2016, 54, 2176–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, S.; Giustra, C.M.; Magoni, C.; Celano, R.; Fusi, P.; Forcella, M.; Sacco, G.; Panzeri, D.; Campone, L.; Labra, M. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of naturally occurring glucosinolates from by-products of Camelina sativa L. and their effect on human colorectal cancer cell line. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 901944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.T.; Chang, W.C.; Chen, P.S.; Chang, T.C.; Chang, S.T. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic antioxidants from Acacia confusa flowers and buds. Journal of Separation Science 2011, 34, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookjitsumran, W.; Devahastin, S.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Chiewchan, N. Comparative evaluation of microwave-assisted extraction and preheated solvent extraction of bioactive compounds from a plant material: a case study with cabbages. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2016, 51, 2440–2449. [Google Scholar]

- Addo, P.W.; Sagili, S.U.K.R.; Bilodeau, S.E.; Gladu-Gallant, F.-A.; MacKenzie, D.A.; Bates, J.; McRae, G.; MacPherson, S.; Paris, M.; Raghavan, V. Microwave-and ultrasound-assisted extraction of cannabinoids and terpenes from cannabis using response surface methodology. Molecules 2022, 27, 8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Shim, Y.Y.; Shen, J.; Jadhav, P.D.; Meda, V.; Reaney, M.J.T. Distribution of Glucosinolates in Camelina Seed Fractions by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2016, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, N.H.; Schierholt, A.; Möllers, C.; Becker, H.C. Pollen Genotype Effects on Seed Quality Traits in Winter Oilseed Rape. Crop Science 2015, 55, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Cheng, S.; Lv, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Glucosinolate Content, Composition and Expression Level of Biosynthesis Pathway Genes in Different Chinese Kale Varieties. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthet, V.J.; Petryk, M.W.P.; Siemens, B. Rapid Nondestructive Analysis of Intact Canola Seeds Using a Handheld Near-Infrared Spectrometer. Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 2020, 97, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Paonessa, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Ambrosone, C.B.; McCann, S.E. Total Isothiocyanate Yield From Raw Cruciferous Vegetables Commonly Consumed in the United States. Journal of Functional Foods 2013, 5, 1996–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhow, M.A.; Polat, Ü.; Gliński, J.A.; Gleńsk, M.; Vaughn, S.F.; Isbell, T.A.; Ayala-Diaz, I.; Marek, L.F.; Gardner, C. Optimized Analysis and Quantification of Glucosinolates From Camelina Sativa Seeds by Reverse-Phase Liquid Chromatography. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 43, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D. Glucosinolates, Structures and Analysis in Food. Analytical Methods 2010, 2, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, M.R.M.; Shiga, T.M.; Vianello, F.; Lima, G.P.P. Analysis of Total Glucosinolates and Chromatographically Purified Benzylglucosinolate in Organic and Conventional Vegetables. LWT 2013, 50, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amyot, L.; McDowell, T.; Martin, S.L.; Renaud, J.; Gruber, M.Y.; Hannoufa, A. Assessment of antinutritional compounds and chemotaxonomic relationships between Camelina sativa and its wild relatives. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2018, 67, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshgani, M.; Kolvoort, E.; de Jong, T. Pronounced effects of slug herbivory on seedling recruitment of Brassica cultivars and accessions, especially those with low levels of aliphatic glucosinolates. Basic and Applied Ecology 2014, 15, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Perez, F.R.; Reichelt, M.; Gershenzon, J.; Heckel, D.G. Interaction of glucosinolate content of Arabidopsis thaliana mutant lines and feeding and oviposition by generalist and specialist lepidopterans. Phytochemistry 2013, 86, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, G.; Agerbirk, N.; Losito, I.; Cataldi, T.R. Acylated glucosinolates with diverse acyl groups investigated by high resolution mass spectrometry and infrared multiphoton dissociation. Phytochemistry 2014, 100, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agerbirk, N.; Olsen, C.E. Isoferuloyl derivatives of five seed glucosinolates in the crucifer genus Barbarea. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, M.; Hara, M.; Fukino, N.; Kakizaki, T.; Morimitsu, Y. Glucosinolate Metabolism, Functionality and Breeding for the Improvement of Brassicaceae Vegetables. Breeding Science 2014, 64, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawlong, I.; Kumar, M.; Gurung, B.; Singh, K.H.; Singh, D. A Simple Spectrophotometric Method for Estimating Total Glucosinolates in Mustard De-Oiled Cake. International Journal of Food Properties 2017, 20, 3274–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Martín, E.M.; Font, R.; Obregón-Cano, S.; Bailón, A.d.H.; Villatoro-Pulido, M.; Río-Celestino, M.D. Rapid and Cost-Effective Quantification of Glucosinolates and Total Phenolic Content in Rocket Leaves by Visible/Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Molecules 2017, 22, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubej, V.; Redovniković, I.R.; Sondi, B.S.; Smolko, A.; Roje, S.; Šamec, D. Chilling and Freezing Temperature Stress Differently Influence Glucosinolates Content in Brassica Oleracea Var. Acephala. Plants 2021, 10, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblath, E.A.; Isbell, T.A.; Berhow, M.A.; Allen, B.L.; Archer, D.W.; Brown, J.; Gesch, R.W.; Hatfield, J.L.; Jabro, J.D.; Kiniry, J.R.; et al. Development of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Calibrations to Measure Quality Characteristics in Intact Brassicaceae Germplasm. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 89, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıkamış, G. Influence of Salinity on Aliphatic and Indole Glucosinolates in Broccoli (Brassica Oleracea Var. Italica). Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2017, 15, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ballesta, M.d.C.; Moreno, D.A.; Carvajal, M. The Physiological Importance of Glucosinolates on Plant Response to Abiotic Stress in Brassica. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 11607–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, T.; Soengas, P.; Velasco, P.; Rodríguez, V.M.; Cartea, M.E. Identification of Metabolic QTLs and Candidate Genes for Glucosinolate Synthesis in Brassica Oleracea Leaves, Seeds and Flower Buds. Plos One 2014, 9, e91428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, C.; He, L.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Gao, J. Identification of Key Genes Controlling Soluble Sugar and Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage by Integrating Metabolome and Genome-Wide Transcriptome Analysis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šamec, D.; Ljubej, V.; Redovniković, I.R.; Fistanić, S.; Sondi, B.S. Low Temperatures Affect the Physiological Status and Phytochemical Content of Flat Leaf Kale (Brassica Oleracea Var. Acephala) Sprouts. Foods 2022, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L. Advances in and Perspectives on Transgenic Technology and CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing in Broccoli. Genes 2024, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastenhout, K.J.; Tornberg, R.H.; Johnson, A.L.; Amolins, M.W.; Mays, J.R. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Based Method to Evaluate Kinetics of Glucosinolate Hydrolysis by Sinapis Alba Myrosinase. Analytical Biochemistry 2014, 465, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaher, C.M.; Gallaher, D.D.; Peterson, S.W. Development and Validation of a Spectrophotometric Method for Quantification of Total Glucosinolates in Cruciferous Vegetables. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2012, 60, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, N.; Dubois, M.; Goldmann, T.; Tarres, A.; Schuster, E.; Robert, F. Semiquantitative Analysis of 3-Butenyl Isothiocyanate to Monitor an Off-Flavor in Mustard Seeds and Glycosinolates Screening for Origin Identification. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2010, 58, 3700–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, C.; Fredericks, D.P.; Griffiths, C.A.; Neale, A. The Characterisation of AOP2: A Gene Associated With the Biosynthesis of Aliphatic Alkenyl Glucosinolates in Arabidopsis Thaliana. BMC Plant Biology 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chastain, J.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, H.H.; Iassonova, D.R.; Rivest, J.; You, H. Eco-Efficient Quantification of Glucosinolates in Camelina Seed, Oil, and Defatted Meal: Optimization, Development, and Validation of a UPLC-DAD Method. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, S.; Giustra, C.M.; Magoni, C.; Celano, R.; Fusi, P.; Forcella, M.; Sacco, G.; Panzeri, D.; Campone, L.; Labra, M. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Naturally Occurring Glucosinolates From by-Products of Camelina Sativa L. And Their Effect on Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Line. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshmand, K.; Fomsgaard, I.S. Analytical Methods for Quantification and Identification of Intact Glucosinolates in Arabidopsis Roots Using LC-QqQ(LIT)-MS/MS. Metabolites 2021, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Li, Z.; Shen, L.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, Z. Quantitative <sup>1</Sup>H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (qHNMR) Methods for Accurate Purity Determination of Glucosinolates Isolated From <i>Isatis Indigotica</I> Roots. Phytochemical Analysis 2020, 32, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-G.; Shim, J.-Y.; Ko, M.-J.; Chung, S.-O.; Chowdhury, M.A.H.; Lee, W.-H. Statistical Modeling for Estimating Glucosinolate Content in Chinese Cabbage by Growth Conditions. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 98, 3580–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Q. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization With Conductive Polymers. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Min, C.; Issadore, D.; Liong, M.; Yoon, T.J.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. Magnetic Nanoparticles and microNMR for Diagnostic Applications. Theranostics 2012, 2, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Yoon, T.J.; Liong, M.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. Magnetic Nanoparticles for Biomedical NMR-based Diagnostics. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2010, 1, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Thiele, B.; Santhiraraja-Abresch, S.; Watt, M.; Kraska, T.; Ulbrich, A.; Kuhn, A.J. Effects of Root Temperature on the Plant Growth and Food Quality of Chinese Broccoli (Brassica Oleracea Var. Alboglabra Bailey). Agronomy 2020, 10, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiron, D.; Iori, R.; Pilard, S.; Rajan, T.S.; Landy, D.; Mazzon, E.; Rollin, P.; Djedaïni-Pilard, F. A Combined Approach of NMR and Mass Spectrometry Techniques Applied to the A-Cyclodextrin/Moringin Complex for a Novel Bioactive Formulation †. Molecules 2018, 23, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R. Separation and Quantification of Four Main Chiral Glucosinolates in Radix Isatidis and Its Granules Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Diode Array Detector Coupled With Circular Dichroism Detection. Molecules 2018, 23, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Long, L.; Li, F.; Wu, G. Development and Validation of a 48-Target Analytical Method for High-Throughput Monitoring of Genetically Modified Organisms. Scientific Reports 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M.A.A.; Nordin, A.N.; Zulhairee, M.; Nor, A.C.M.; Noorden, M.S.A.; Muhammad Khairul Faisal Muhamad, A.; Rahim, R.A.; Zain, Z.M. Portable Electrochemical Biosensors Based on Microcontrollers for Detection of Viruses: A Review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanaga, M. High-Sensitivity High-Throughput Detection of Nucleic Acid Targets on Metasurface Fluorescence Biosensors. Biosensors 2021, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazie, M.D.; Kim, M.J.; Ku, K.M. Health-Promoting Phytochemicals From 11 Mustard Cultivars at Baby Leaf and Mature Stages. Molecules 2017, 22, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, P. GLS-Finder: A Platform for Fast Profiling of Glucosinolates in <i>Brassica</I> Vegetables. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2016, 64, 4407–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.H.; Kiraga, S.; Islam, N.; Ali, M.; Reza, N.; Lee, W.H.; Chung, S.O. Effects of Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Carbon Dioxide Concentration on Growth and Glucosinolate Content of Kale Grown in a Plant Factory. Foods 2021, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ahlawat, Y.; Liu, T.; Zare, A. Evaluation of Postharvest Senescence of Broccoli via Hyperspectral Imaging. Plant Phenomics 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glucosinolate types | Chemical Names | Common Names | Characterization Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AliphaticGSLs | Methyl GSL | Glucocapparin | MS, NMR | |

| 1-Methylethyl GSL | Glucputranjivin | UV, IR, MS, NMR | ||

| (1R)-Methyl-2-hydroxyethyl GSL | Glucosisymbrin | MS, NMR | ||

| 3-Methoxycarbonyl-propyl GSL | Glucoerypestrin | NMR | ||

| Ethyl GSL | Glucolepidiin | Thiourea-type | ||

| 4-Oxoheptyl GSL | Glucocapanglin | Deducted from IR and 5-oxooctanoic acid | ||

| 5-Oxoheptyl GSL | Gluconorcappasalin | Thiourea-type, IR compared to GSL | ||

| 5-Oxooctyl GSL | Glucocappasalin | UV, IR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| 2-Hydroxy-2-methylpropyl GSL | Glucoconringiin | MS, NMR | ||

| (1S)-1-Methylpropyl GSL | Glucocochlearin | MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| (1R)-1-(Hydroxymethyl)-propyl GSL | Glucosisaustricin | MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| (2S)-2-Methylbutyl GSL | Glucojiaputin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL and des GSL | ||

| (2S)-2-Hydroxy-2-methylbutyl GSL | Glucocleomin | NMR of desGSL | ||

| 3-(Methylsulfanyl)propyl GSL | Glucoibervirin | MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| 4-Oxoheptyl GSL | Glucocapangulin | Deduction from IR,5-oxooctanoic acid | ||

| 4-(Methylsulfanyl)butyl GSL | Glucoerucin | UV, IR, MS NMR of GSL | ||

| 5-(Methylsulfanyl)pentyl GSL | Glucoberteroin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 6-(Methylsulfanyl)hexyl GSL | Glucolesquerellin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| (R)-11-(Methylsulfinyl)-propyl glucosinolate | Glucoiberin | MS, NMR, X-Ray of GSL; UV | ||

| (R/S)-4-(Methylsulfinyl)-butyl glucosinolate | Glucoraphanin | MS, NMR of GSL, UV | ||

| (R/S)-5-(Methylsulfinyl)pentyl GSL | Glucoalyssin | MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| (R/S)-6-(Methylsulfinyl)-hexyl GSL | Glucohesperin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| (R/S)-8-(Methylsulfinyl)-octyl GSL | Glucohirsutin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL; | ||

| (R/S)-9-(Methylsulfinyl)-nonyl GSL | Glucoarabin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL; | ||

| (R/S)-10-(Methylsulfinyl)decyl GSL | Glucocamelinin | MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| 3-(Methylsulfonyl)-propyl GSL | Glucocheirolin | MS of GSL; NMR of desGSL | ||

| 4-(Methylsulfonyl)butyl GSL | Glucoerysolin | MS of GSL; MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| (R/S, 3E)-4-(Methylsulfiny1)-but-3-enyl GSL | Glucoraphenin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV,NMR of desGSL | ||

| (R)-4-(Cystein-S-yl) butyl GSL | Glucorucolamine | MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 4-(β-D-Glucopyranosyl-disulfanyl)-butyl GSL | Diglucothiobeinin | MS of GSL; MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 6-Benzoyl-4 (methylsulfanyl)butyl GSL | 6'-Benzoyl-glucoerucin | UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 6'-Benzoyl-4(methylsulfinyl)butyl GSL | 6'-Benzoyl-glucopharanin | UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| (R/S,3E)-6-Sinapoyl-4 (methylsulfinyl)but-3-enyl GSL | 6'-Sinapoyl-glucoraphenin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| Allyl glucosinolate | Sinigrin | MS, NMR, X-Ray of GSL; UV | ||

| But-3-enyl GSL | Gluconapin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, | ||

| Pent-4-enyl GSL | Glucobrassicanapin | MS of GSL | ||

| (2S)-2-Hydroxypent 4-enylGSL | Gluconapoleiferin | MS of GSL | ||

| (2R)-2-Hydroxybut 3-enylGSL | Progoitrin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| (2S)-2-Hydroxybut 3-enylGSL | Epiprogoitrin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| Glucosinolate types | Chemical Names | Common Names | Characterization Methods | |

| Aromatic GSLs | (1R)-2-Bezoyloxt-1-methylethyl GSL | Glucobenzosisymbrin | UV, IR of ITC | |

| (1R)-1-(Benzoyloxymethyl) propyl GSL | Glucobenzsisaustricin | Thiourease-type, IR compared to GSL | ||

| Benzyl GSL | Glucotropaeolin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 3-Hydroxybenzyl GSL | Glucolepigramin | MS of GSL; MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 3-Methoxybenzyl GSL | Glucolimnanthin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 4-Hydroxybenzyl GSL | Glucosinalbin | UV, MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| 4-Methoxybenzyl GSL | Glucoaubrietin | MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzyl GSL | Glucomatronalin | MS of GSL | ||

| 4-Hydorxy3-methoxybenzyl GSL | 3-Methoxysinalbin | UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 3-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzyl GSL | Glucobretschneiderin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| 4-Hydorxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzyl GSL | 3,5-Dimethoxy-sinalbin | UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 2-Phenylethyl GSL | Gluconasturtiin | NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 2-hydroxy-2-phenylethyl GSL | Glucobarbarin | MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| (2R)-2-Hydroxy-2-phenylethyl GSL | Epiglucobarbarin | MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| 2-(4-Methoxy-phenyl) ethyl GSL | Glucoarmoracin | NMR of GSL, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| (2R)-2-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl GSL | p-Hydroxy-epiglucobarbarin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| (2S)-2-Hydroxy-2(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl GSL | p-Hydroxy-glucobarbarin | UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 4-(4'-O-Acetyl-α-c-4-rhamnopyranosyloxy)-benzyl GSL | 4-Acetyl-glucomoringin | MS of GSL and ITC | ||

| 6'-Isoferuloyl-2 phenylethyl GSL | 6'-Isoferuloyl gluconasturtiin | MS of GSL, UV | ||

| 6'-Isoferuloyl-(2R) 2-hydroxy-2phenylethyl GSL | 6'-Isoferuloyl epiglucobarbarin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV | ||

| 6'-Isoferuloyl-(2S) 2-hydroxy-2phenylethyl GSL | 6'-Isoferuloyl glucobarbarin | MS, NMR of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 4-(α-L-Rhamnopyranosyloxy) benzyl GSL | Glucomorinigin | MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| Indolic GSLs | 4-Methoxyindol-3-yl GSL | Glucorapassicin A | UV, IR, MS, NMR of synthesized GSL | |

| Indol-3-ymethyl GSL | Glucobrassicin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| 4-Hydroxyindol-3-ylmethyl GSL | 4-Hydroxy-glucobrassicin | MS of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 4-Methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl GSL | 4-Methoxy-glucobrassicin | UV, MS, MS, NMR of GSL and desGSL | ||

| 1-Methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl GSL | Neoglucobrassicin | UV, IR MS, NMR of GSL; MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 1,4-Dimethoxyindol-3-ymethyl GSL | 1,4-Dimethoxy-glucobrassicin | UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

| 1-Acetylindol-3-ymethyl GSL | N-Acetyl-glucobrassicin | MS of desGSL | ||

| 1-Sulfoindol-3-ylmethyl GSL | N-Sulfo-glucobrassicin | UV, IR, MS, NMR of GSL | ||

| 6'-Isoferuloylindol-3-ylmethyl GSL | 6'-Isoferuloyl-glucobrassicin | MS of GSL; UV, MS, NMR of desGSL | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).