1. Introduction

RNA is a foundational biopolymer and a cornerstone to the central dogma of molecular biology [

1]. Having likely given rise to the earliest stages of evolution, RNA can be found in every species yet described, alongside fellow biopolymers such as DNA, proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates [

2]. While RNA plays a diverse set of biochemical roles, it has traditionally been limited to its roles in intracellular transcription and translation, while proteins, lipids, and small molecules have been the main proprietors of extracellular function.

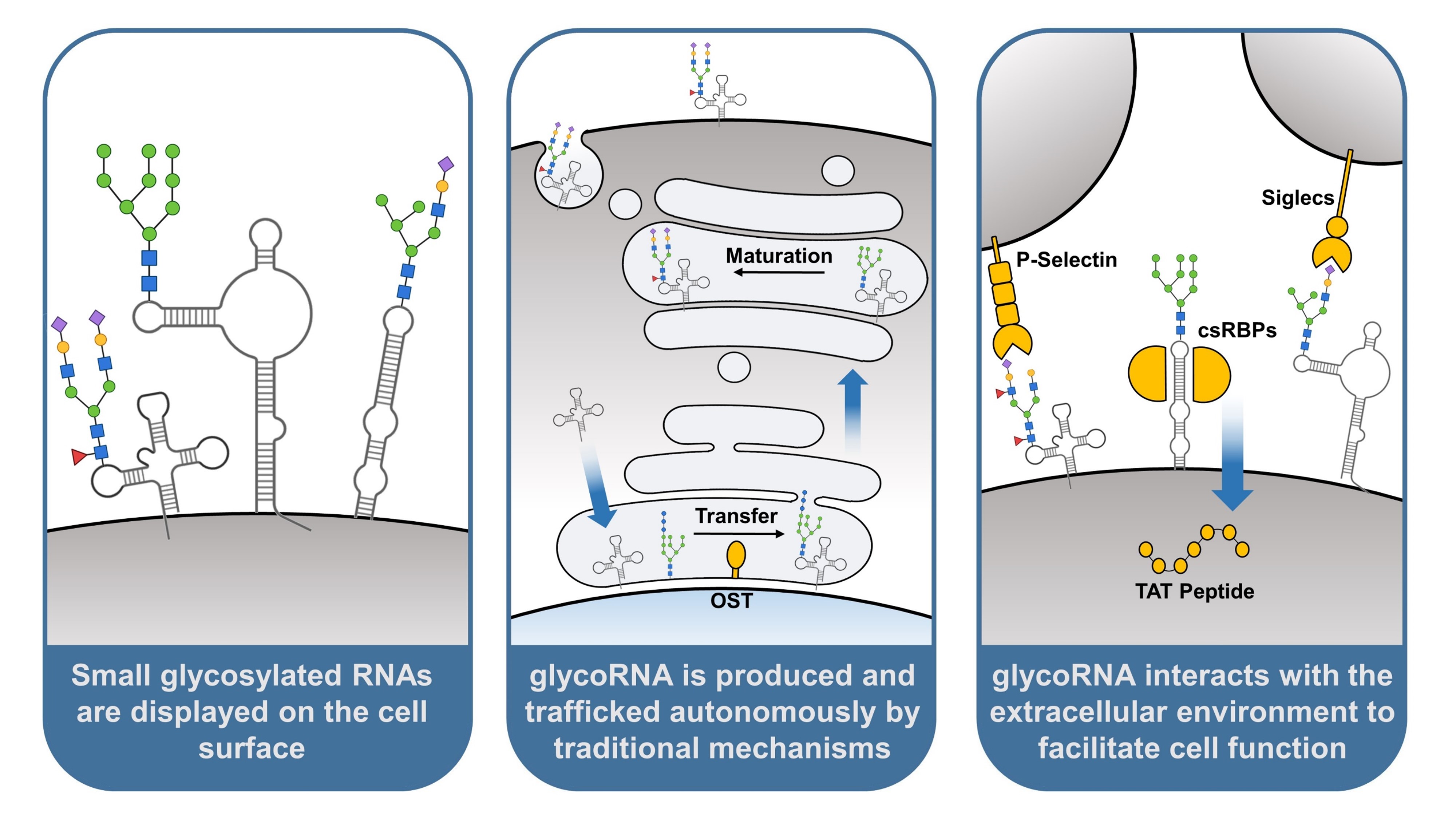

Recently, the molecular model of RNA was upended by the discovery that transcripts can be post-transcriptionally modified with canonical glycan groups, a trait previously thought to be exclusive to proteins and lipids. Equally new is the discovery that, like glycoproteins and glycolipids, glycosylated RNA (glycoRNA) is naturally displayed on the mammalian cell surface, a seldom-explored environment for RNA function [

3]. Glycans presented by glycoconjugates on the plasma membrane collectively form a sugary coating around cells called the glycocalyx, and provide inherent changes to protein and lipid structure and function [

4]. How glycoRNA contributes to the glycocalyx and what functions the post-transcriptional modification provides have become an area of intense study.

Here, we present a major milestone of this growing body of work: an early model of glycoRNA. This model identifies the glycocojugates’s defining biochemical properties, methods of trafficking and production, and how the substrate contributes to cellular function. We summarize the foundational studies responsible for this model with emphasis on the technical basis of many discoveries, and include the prevailing theories around unexplained observations. To make the reader a part of the academic discussion surrounding glycoRNA, we also highlight current challenges to its study, and point to important questions relevant to expanding this model.

As a final contribution, we provide several resources to ease study design, collating information on cell lines with detectable glycoRNA expression and on glycosylated transcripts found across multiple sequencing datasets. Through these resources and our discussion, we hope to provide a framework around which to build future glycoRNA experiments and attract new scientists to this novel branch of RNA research.

2. Small Non-Coding RNAs Can be Modified with Traditional Glycosylation

The most distinguishing feature of glycoRNA is its novel post-transcriptional modification (PTM); the attachment of canonical glycan groups. Glycan groups are polymers composed of covalently-linked monosaccharide units. Glycosylation, the process of attaching these groups to a substrate, is well-documented, and can be found in every organism yet described [

4]. Proteins and lipids are the typical substrates for glycosylation, wherein the modified glyconjugates go on to play roles in cell adhesion, immune recognition, and maintaining the biophysical structure of tissues [

5,

6,

7].

Many RNAs undergo comparatively simple post-transcriptional modifications crucial to the normal function of some transcripts, such as methylation [

8,

9]. The closest PTM to glycosylation previously observed is the incorporation of modified ribonucleosides containing mannose and galactose monosaccharides to cytosolic tRNA transcripts [

10]. The role of these modified bases is still speculative, but it would be reasonable to assume that attachment of larger glycan groups, as seen in glycoRNA, could profoundly change or interrupt the function of RNA transcripts.

glycoRNA was first described by Flynn et al, 2021. To identify whether RNA was a substrate for glycosylation, live cells were incubated with peracetylated N-azidoacetylmannosamine (Ac4-ManNAz), a metabolic precursor to the monosaccharide sialic acid. Ac4-ManNAz is metabolically processed and incorporated into resulting sialoglycoconjugates, which can be isolated and tested downstream by click chemistry-based labeling with biotin [

11]. Isolation and labeling of total RNA from incubated cells resulted in a detectable biotin-labeled compound. This detection could be abrogated by exposure to RNase or vc-sialidase, but not proteinase K, indicating the signal was due to the co-presence of RNA and sialic acid, and was not an artifact from protein contamination [

3].

While glycoRNA isolated through this method was found to migrate with large RNA bands during agarose gel electrophoresis, subsequent fractionation using length-dependent RNA precipitation consistently isolated glycoRNA within the small RNA fraction (<200 nucleotides). glycoRNA was also unable to be isolated through poly-A enrichment, suggesting only small non-coding sequences undergo glycosylation [

3]. Sequencing has found that a variety of small RNA classes comprise glycoRNA, including small nuclear RNA (snRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA),Y RNA, U RNA rRNA, and tRNA [

3,

12].

In addition to a limited subset of sequences, glycoRNA also comprises a limited subset of glycans compared to traditional substrates. For one, glycoRNA is subject solely to modification with N-glycans [

3]. N-glycans are glycan groups with a core composed of two N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) molecules, traditionally attached to glycoproteins via the nitrogen in asparagine residues. O-glycans, in comparison, have one of four different core structures, all beginning with N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), and attach to proteins via the oxygen in serine and threonine residues [

4]. Inhibition of O-glycan synthesis machinery has little impact on glycoRNA expression, and preliminary work has not yet co-isolated O-glycans with RNA [

3].

RNA-linked glycans also differ from traditional glycans in their structural diversity. Mass spectrometry of glycans released from RNA via PNGase-F digestion has been used to characterize this differential expression. In Flynn et al, 2021, glycans released from the small RNA fractions of HeLa, H9, and 293 cells are quantified in this manner. Compared to glycans released from peptide pools of the three cell lines, glycoRNA-derived glycans represented fewer unique isoforms. In HeLa and H9 cells, these isoforms were more likely to contain fucose than peptide-derived glycans, and in 293 cells, were more likely to contain sialic acid [

3]. The independence of this method from Ac4-ManNAz metabolic labeling allowed the study of asialylated glycans, making the former observation possible.

This technique was recently expanded upon to study glycoRNA from a cohort of human tissues, creating a putative atlas of glycoRNA glycans. Biobank samples of heart, lung, liver, spleen, stomach, kidney, intestine, colon, testis, fat, muscle, and brain tissue were analyzed using a similar mass spectrometry pipeline, identifying a total of 677 unique RNA-linked N-glycan structures. This atlas corroborates the earlier mass spectrometry findings relating to fucose abundance, with the majority of tissues characterized having 50% or more glycan structures containing fucose. Interestingly, glycan diversity was found to be highly tissue specific, with the number of unique glycan structures per tissue varying from 17 (heart) to 118 (spleen). Additionally, of the 677 unique glycan structures, 431 could only be found in a single organ (63.8%) [

13]. These data suggest that RNA glycosylation is selectively regulated across different tissues.

The dominant method of glycan attachment to protein and lipid substrates is a covalent bond [

4]. This is also hypothesized to be the method of attachment employed by glycoRNA. The first direct evidence of this covalent linkage was observed recently by Xie et al, 2024. In this study, glycoRNA was labeled, captured, and subject to RNA digestion to remove nucleosides not covalently linked to glycans. The remaining nucleosides were released by either PNGase-F or Endo F2 and Endo F3 digestion, the latter of which digests N-glycans between the first and second GlcNAc unit of their core [

14]. Mass spectrometry of PNGase-F-eluted bases found three modified nucleosides present consistently across all cell types tested: yW-72, yW-82, and acp3U. Material released with Endo F2 and Endo F3 also contained a mass signature that matched with a synthetic standard of acp3U-GlcNAc, confirming the modified nucleoside can naturally be covalently linked to GlcNAc [

15]. acp3U can be found in tRNA, and is synthesized in both mammalian and bacterial cells [

16]. The observation of acp3U as a covalent attachment site for N-glycans provides the most direct evidence for glycoRNA as a novel biopolymer, and opens up the possibility of glycoRNA existing outside mammalian systems.

3. GlycoRNA Is Presented on the Mammalian Cell Surface

In addition to glycobiology, glycoRNA has also contributed to the emerging field of cell surface RNA. Cell surface RNA, referred to by multiple nomenclatures such as membrane associated RNA, membrane associated extracellular RNA (maxRNA), and plasma membrane associated RNA (PMAR) has long been known to play a role in microbiology, but is only beginning to be studied in mammalian cells [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Suggestions of its existence date back as far as the 1960’s, with the observation of RNA “footprints” left on cell culture substrates after the detachment of adherent cells [

21]. Nucleic acids were later observed on the cell surface of cultured cells, but the effect was negated by washing, suggesting weak association as a product of in vitro tissue culture [

22,

23]. Robustly attached cell surface RNA was characterized on mammalian cells by Huang et al, 2020, with research ongoing to elucidate the mechanisms and functions of these transcripts [

17].

The hypothesis that glycoRNA could be displayed on the cell surface was inspired by the similar display of glycoproteins and glycolipids, as well as evidence that glycoRNA was strongly enriched in the membranous organelle portion of fractionated cells. Confirmation of this display was first achieved by the use of a N-glycan-localized peroxidase, which was able to label RNA in the vicinity of cell surface N-glycans without permeabilization of the plasma membrane. Anti-dsRNA antibodies are also capable of recognizing glycoRNA, facilitating the use of flow cytometry on live cells to broadly assess glycoRNA expression. Of note is that antibody staining can be significantly abrogated by inhibiting glycosylation machinery such as oligosaccharyltransferase (OST), confirming that binding is due in large part to glycoRNA rather than overall cell surface RNA [

3].

To further characterize the localization of glycoRNA on the cell surface, Ma et al, 2023 developed the sialic acid aptamer and RNA in situ hybridization-mediated proximity ligation assay (ARPLA). This method bridges the gap between antibody and peroxidase labeling by enabling the specific and sensitive detection of RNA only when in close proximity to sialic acid. The assay uses four DNA-based components to achieve this; a DNA aptamer that binds Neu5Ac sialic acid, a RNA in situ hybridization (RISH) probe against putative glycoRNA sequences, and two ssDNA connectors that bind trailing tails on the previous components. A sialoglycoRNA molecule will bind the sialic acid aptamer and RISH probe, bringing them in close proximity and enabling the connectors to hybridize, linking the two binding components. T4 DNA ligase is then used to circularize the connectors, the resulting region of which undergoes rolling circle amplification and is bound by a fluorochrome-conjugated probe. ARPLA is compatible with traditional methods in fluorescent microscopy, allowing the subcellular imaging of glycoRNA [

24].

Leveraging this compatibility, ARPLA was used in conjunction with antibody labeling to gain new insights into the cell surface localization of glycoRNA. Co-staining for common targets on lipid rafts showed that glycoRNA co-localizes with these regions of the cell surface [

24]. Lipid rafts are heterogeneous regions of the plasma membrane created by preferential interactions between cholesterol and saturated lipids. Biochemically, the regions are characterized by an ordered and tightly packed structure, along with increased local concentrations of GPI-anchored proteins, glycoproteins, glycolipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol [

25]. Cell surface RNAs have previously been reported to co-localize with lipid rafts, but glycosylation of the transcripts was not assayed [

19]. Further research is needed to determine the importance of this localization, as the exact biophysical characteristics and function of lipid rafts remains a contentious topic.

4. GlycoRNA Originates from Endogenous Glycosylation and Trafficking Mechanisms

With the key properties of glycoRNA established, the next step is to understand how glycoRNA is synthesized and presented. A logical beginning to this process is to ask whether glycoRNA present on a cell is autonomously trafficked to the plasma membrane, or passively captured from the environment as the product of other cells. The capture and use of environmental RNAs has been well-documented, with extracellular RNA and vesicular RNA being cases of such use [

26]. RNA is also released from cells upon apoptosis, with released ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) acting as auto-antigens in several pathologies [

27,

28].

To answer this, Zhang et al, 2024 performed a co-culture experiment with bone marrow-derived neutrophils. Neutrophils were split into two dyed groups, with one group undergoing Ac4-ManNAz metabolic labeling. Following labeling, the groups were combined and co-cultured for 72 hours, then sorted back into separate populations. RNA extracted from the separate populations showed Ac4-ManNAz content only in cells originally treated with the metabolic label, indicating glycoRNA had not spread between cells during co-culture [

12]. This supports a model in which glycoRNA is autonomously produced, rather than being captured from the environment.

The cellular machinery involved in autonomous production of glycoproteins is also involved in glycoRNA production. Oligosaccharyltransferase (OST), which plays a significant role in protein N-glycosylation, is a key component of this machinery. Located on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, OST catalyzes the transfer of pre-made N-glycans onto polypeptides as they are translated into the ER lumen [

29]. In vitro treatment of cells with NGI-1, an inhibitor of OST, has been shown to reduce the presence of glycoRNA in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that OST is also necessary for the transfer of N-glycans onto RNAs [

3,

24]. Importantly, this action may not be direct, as with protein glycosylation. It has been hypothesized that glycoproteins synthesized by OST could transfer their glycan groups onto RNA transcripts outside the ER, providing an indirect role for the enzyme. Future experiments may assess this hypothesis by determining if RNA proximity to OST is achieved, and whether this proximity is required for glycoRNA synthesis.

RNA would have to be localized to the ER lumen to be subject to the catalytic activity of OST in a direct model. Using enzyme-mediated proximity labeling, Ren et al, 2023 provide evidence for this localization. HEK293T cells were engineered to express an ER lumen-restricted peroxidase capable of covalently biotinylating nearby substrates, including RNA. Engineered cells were treated with biotin phenol and hydrogen peroxide to activate the peroxidase. Labeled RNA was extracted, enriched for biotinylation, and sequenced. Analysis of enriched sequences found that ER-localized RNA has several of the same features as glycoRNA, specifically length and function. ER-localized RNA were significantly shorter on average than total RNA, and over half of enriched transcripts belonged to non-coding RNAs. Subsequent enrichment and sequencing using only small RNA input identified 76 significantly enriched transcripts, belonging primarily to U RNA, Y RNA, and snoRNA [

30]. These are among the same groups identified in the initial characterization of glycoRNA. suggesting the presence of nascent glycoRNA in the ER lumen.

The discovery of RNA in the ER lumen is striking, as there are no currently recognized mechanisms for RNA transport into the ER. A leading candidate for this localization is SIDT, a family of transmembrane proteins. SIDT is the mammalian ortholog of the SID family in C. elegans, whose members passively transport single-stranded RNA, double-stranded RNA, and cholesterol across membranes [

31]. This activity allows C. elegans to ingest RNA from their environment and systemically incorporate it into cells [

32]. While mammals lack SID’s full abilities, SIDT proteins have been observed to import RNA from endolysosomes to the cytosol during viral infection, conserving the same basic activity as RNA transporters [

33]. SIDT is also necessary for glycoRNA production; knockdown of SIDT1 and SIDT2 in tandem has been shown to completely ablate glycoRNA content in immortalized murine bone marrow progenitor cells, on a level comparable to treatment with RNase [

12]. Given the proteins’ known functions, it is hypothesized that SIDT could be importing cytosolic RNA into the ER lumen prior to glycosylation and trafficking, with its knockdown making this cellular compartment inaccessible. Future experiments may probe this hypothesis by better characterizing the subcellular localization of SIDT, asking whether SIDT is active in the ER membrane or if its role in glycoRNA production is carried out elsewhere.

If glycoRNA are modified by the same enzymes as glycoproteins and localize to the same spaces during synthesis, it would be reasonable to ask whether they are also trafficked to the plasma membrane through the same mechanisms. Proteins destined for the plasma membrane are normally translated into the ER lumen before being shuttled to the golgi apparatus, where they are packaged into vesicles and delivered to the cell surface [

2,

34]. Using their ARPLA method, Ma et al, 2023 present evidence that glycoRNA can be found alongside a crucial protein to this latter step, the SNARE complex [

24]. SNARE is composed of two proteins, t-SNARE and v-SNARE. t-SNARE is a multimeric complex found on the surface of a target membrane, while v-SNARE is a monomeric protein attached to the outer surface of vesicles. The two components, when bonded, will bring a vesicle in close contact with the target membrane, catalyzing the fusion of the vesicle with the membrane and the release of its contents [

35]. Vesicles from the golgi apparatus leverage this complex to deliver proteins to specific cellular compartments, including the transport of transmembrane and secretory proteins to the cell surface [

34]. The finding that glycoRNA can be co-localized with the SNARE complex supports the hypothesis that glycoRNA is subject to the same vesicular trafficking mechanisms as glycoproteins.

5. GlycoRNA Selectively Interacts with Proteins to Facilitate Cell Functions

The discovery of glycoRNA immediately posed questions as to its biological function. Being on the cell surface, interest was naturally drawn to how glycoRNA may interact with proteins, small molecules, and other components of the extracellular environment. Flynn et al, 2021 broke ground on this question by assessing the binding potential of siglec receptors to glycoRNA on HeLa cells. Sialic acid binding-immunoglobulin lectin-type receptors, or siglecs, recognize sialic acid ligands on a broad but poorly characterized set of glycoconjugates, previously assumed to be proteins and lipids [

6]. Recognition of these putative ligands on pathogens mediates an immune response from the cell type expressing the receptor, typically circulating or tissue resident leukocytes [

36]. Siglecs were an ideal candidate for initial screening, as their complete set of ligands remains unknown. From a flow cytometry array of 12 commercially available siglec-Fc reagents, siglec-11 and siglec-14 were found to have RNase-sensitive binding to HeLa cells, providing evidence that RNA-bound glycans can also be targeted by these receptors, possibly facilitating cell-cell communication [

3].

The interactions between glycoRNA and another class of glycan-binding receptors, selectins, have been studied in greater depth. Selectins are cell adhesion proteins expressed on endothelial cells upon proinflammatory signaling, where they participate in recruitment of leukocytes from the bloodstream [

37]. Similar to siglecs, the glycan target base for selectins remains poorly understood. glycoRNA-selectin interaction was established in Zhang et al, 2024 while studying the role of cell surface RNA in neutrophil recruitment. P-selectin (Selp), a selectin family member, was found to have RNase-sensitive binding to murine bone marrow neutrophils using a Selp-Fc reagent for flow cytometry. Selp-Fc was then used to blot total RNA on a gel, resulting in an identically labeled band to that of Ac4-ManNAz-labeled glycoRNA. To establish glycoRNA as a ligand for Selp, murine endothelial cells were treated with biotin-labeled glycoRNA and analyzed by flow cytometry with fluorescently conjugated streptavidin. glycoRNA treatment was able to clearly label cells above background, but labeling could be significantly reduced by pre-blocking cells with an anti-Selp antibody, supporting P-selectin as a binding site for glycoRNA on endothelial cells.

The impact of glycoRNA-Selp binding is further evident at the systems level. Murine in vivo experiments initially showed that removal of cell surface RNA from primary mouse neutrophils caused a 9- to 10-fold reduction in their ability to extravasate at sites of inflammation. Intravital imaging of labeled neutrophils shows that cell surface RNA removal specifically impaired neutrophils’ ability to transition from free-flowing in the bloodstream to rolling on the endothelium [

12]. This phase of extravasation is known to be mediated by P-selectin [

38]. The results were recapitulated using a SIDT knockdown cell line in HOXB8-immortalized differentiated neutrophils, indicating the effect was specific to glycoRNA loss [

12]. Together, these findings suggest that P-selectin on endothelial cells recognizes glycoRNA on neutrophils, among other glycoconjugates, contributing to adhesion and extravasation at inflammatory sites. This expands on previous work implicating cell surface RNA as a factor in adhesion of other types of innate immune cells, including monocytes, resting macrophages, and activated macrophages [

17].

In addition to interacting with proteins outside the host cell, glycoRNA functions alongside other membrane-bound proteins. The possibility of native glycoRNA-protein binding on the cell surface arose while attempting to label cell surface RNA using 5’-bromouridine (BrU). Anti-BrU antibody was initially unable to detect labeled transcripts on the cell surface, but treatment with extracellular proteinase-K prior to detection was able to rescue binding [

12]. This indicated that cell surface RNA, including glycoRNA, may be surrounded by clusters of proteins that sterically hinder antibody binding. This theory would also help to explain the persistence of RNA on the cell surface, as proteins surrounding the transcripts could provide protection from degradation by extracellular RNases at physiological concentrations [

39].

A recent study (Perr et al, 2023) explored these cell surface glycoRNA-protein interactions in greater detail. By performing a meta-analysis of cell surface proteomics data, a putative list of 179 cell surface RNA binding proteins (csRBPs) was generated. A validated subset of csRBPs, particularly DDX21, hnRNP-U, and DNA-PKcs, were found to form nanoscale clusters on the cell surface, with other csRBPs making up a significant fraction of neighboring proteins. Cell surface RNA could be found in proximity to 8-23% of these clusters, as detected by anti-dsRNA antibody. csRBP clustering could also be interrupted by extracellular RNase treatment, reducing the number of observed clusters by up to 60%. The detected RNA was later quantified to be primarily glycoRNA, as determined by its ability to change apparent molecular weight on a gel after sialidase digestion. Overall, these results indicate that glycoRNA in part coordinates clustering of csRBPs on the cell surface [

40].

While the function of these glycoRNA-csRBP clusters is yet to be fully explored, initial work shows they may play a role in cell penetrating peptide entry. Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) are short peptides capable of internalizing through the plasma membrane, naturally leveraged for viral entry and transcription [

41]. An established mechanism for this entry is the binding of cationic CPPs to negatively charged components of the cell surface, such as sialic acid or heparan sulfate [

42]. RNA is fundamentally negatively charged, leading to the possibility that it too may be a target for CPP binding on the cell surface [

43]. This possibility was assessed using the TAT peptide, a CPP derived from HIV [

44]. TAT peptide was found to co-localize both with cell surface RNA and csRBPs prior to cell entry. Digestion of cell surface RNA could also reduce TAT binding by 30%, and entry by 47.5%. The negative charge of glycoRNA was not the sole factor impacting TAT entry. A R5K variant of TAT was created with a mutation at a critical residue to RNA binding, yet carrying the same net charge as wild-type TAT. Mutant TAT was able to bind the cell surface at similar levels as wild-type TAT, but suffered a 40% reduction in cell entry. These observations fit a model in which glycoRNA clustered with csRBPs act as ligands for the TAT peptide, whose initial binding is governed by electrostatic interactions between the substrates, but with internalization requiring a degree of epitope specificity from the peptide itself [

40].

6. Qualities of GlycoRNA Expression

RNA expression and the mechanisms that regulate it are crucial to achieve different cellular states. Simple changes to the number of accessible transcripts for a given RNA can give rise to complex phenotypes, the analysis of which has been revolutionized by transcriptomics [

45]. Just as intracellular RNAs have state-dependent expression profiles, there is mounting evidence that glycoRNA expression is similarly regulated.

glycoRNA has been detected in 18 cell lines, as well as in a variety of primary human and murine tissues, suggesting it may be a constitutive and widely expressed component of the cell surface (

Table 1) [

3,

12,

15,

24,

40,

46]. Transcriptomic analysis reveals insights into the mechanisms behind this shared expression, and why certain RNAs are chosen for glycosylation. Sequencing of glycoRNA from HeLa and H9 cell lines shows that transcripts fall into distinct patterns of enrichment or depletion compared to total RNA samples, suggesting a method of selection for glycosylation. In general, transcripts enriched in one cell line were enriched in the other at a similar rate, with few transcripts exhibiting different expression profiles [

3]. These findings were recapitulated in sequencing data gathered from multiple mouse neutrophil cell lines [

12].

Together, these transcriptomic analyses point towards a model in which RNA sequences are selected for glycosylation by a mechanism that is conserved across different species and tissues. The exact nature of this mechanism is still unknown, but is speculated to work based on abundance, hence the enrichment of common, abundant classes of non-coding RNA such as rRNA and tRNA. This is supported by data showing that a few common transcripts can make up significant fractions of the glycoRNA transcriptome. In primary mouse neutrophils, two fragments of the 45S rRNA compose over 25% of glycoRNA transcripts, and in HEK293T cells, knockout of the Y5 RNA can abrogate up to 30% of glycoRNA content [

3,

24].

Sequencing datasets are limited at the moment, prohibiting further insights into differential expression at the transcript level. The majority of measurements have been recorded using bulk means to assess the large-scale abundance of glycoRNA. However, important observations about glycoRNA abundance across cell types have been noted through these methods.

Changes in bulk glycoRNA expression have been associated with differentiation in innate immune cells. In Ma et al, 2023, glycoRNA levels on THP-1 and HL-60 leukemic cell lines were monitored during differentiation into resting macrophages and neutrophil-like cells, respectively. Expression was assessed using ARPLA targeting the U1, U35a, and Y5 transcripts, as well as in bulk through Ac4-ManNAz labeling. A trend was seen across all methods that glycoRNA expression was reduced after differentiation compared to the progenitor states, effecting both resting macrophages and neutrophil-like cells. Expanding on this experiment to study the effects of pathogen exposure, resting macrophages were activated with E. coli derived lipopolysaccharides. Activated macrophages had greater glycoRNA expression than both resting macrophages and the THP-1 progenitor cell line [

24]. These results show that glycoRNA expression is regulated in response to differentiation and activation of innate immune cells.

The increase in macrophage glycoRNA expression after activation is notable, particularly when considering the molecules’ importance in neutrophil recruitment. Upregulation of glycoRNA may assist innate immune cells in extravasating at sites of inflammation, restricting this behavior to only cells in an activated state. Selp, the protein involved in neutrophil recruitment via glycoRNA, is also known to help recruit macrophages, further suggesting the same mechanism of action could be at play in this cell type [

47]. The reliance of Ac4-ManNAz metabolic labeling and ARPLA on sialic acid incorporation into glycans also restricts these findings to sialoglycoRNA. This presents the possibility that overall quantities of glycoRNA are not changing on the cell surface, but that the glycoconjugates are reducing their sialic acid content, thereby differentially expressing the glycan rather than the RNA component.

glycoRNA expression is sensitive not only to healthy changes in cellular state, but also to changes brought on by disease. Dysregulated glycosylation is a hallmark of many pathologies, from metabolic to neurological conditions. Cancer in particular is known to leverage glycosylation, with one of the most frequent changes being hypersialylation, or the overexpression of sialic acid [

48]. The relationship between glycoRNA expression and hypersialylation was recently studied in the context of breast cancer. Cell lines representing benign, malignant, and metastatic progressions were assessed for both broad sialic acid and sialoglycoRNA expression. Surprisingly, while cells exhibited the expected hypersialylation associated with greater progression, sialoglycoRNA content was found to decrease with more advanced states [

24]. Hypersialylation is thought to benefit cancer progression by recruiting anti-inflammatory immune cells and assisting the release of circulating metastatic cells [

49]. Future functional studies may help clarify whether glycoRNA is deliberately downregulated to similarly promote tumor progression, or if its loss is a byproduct of other cellular changes.

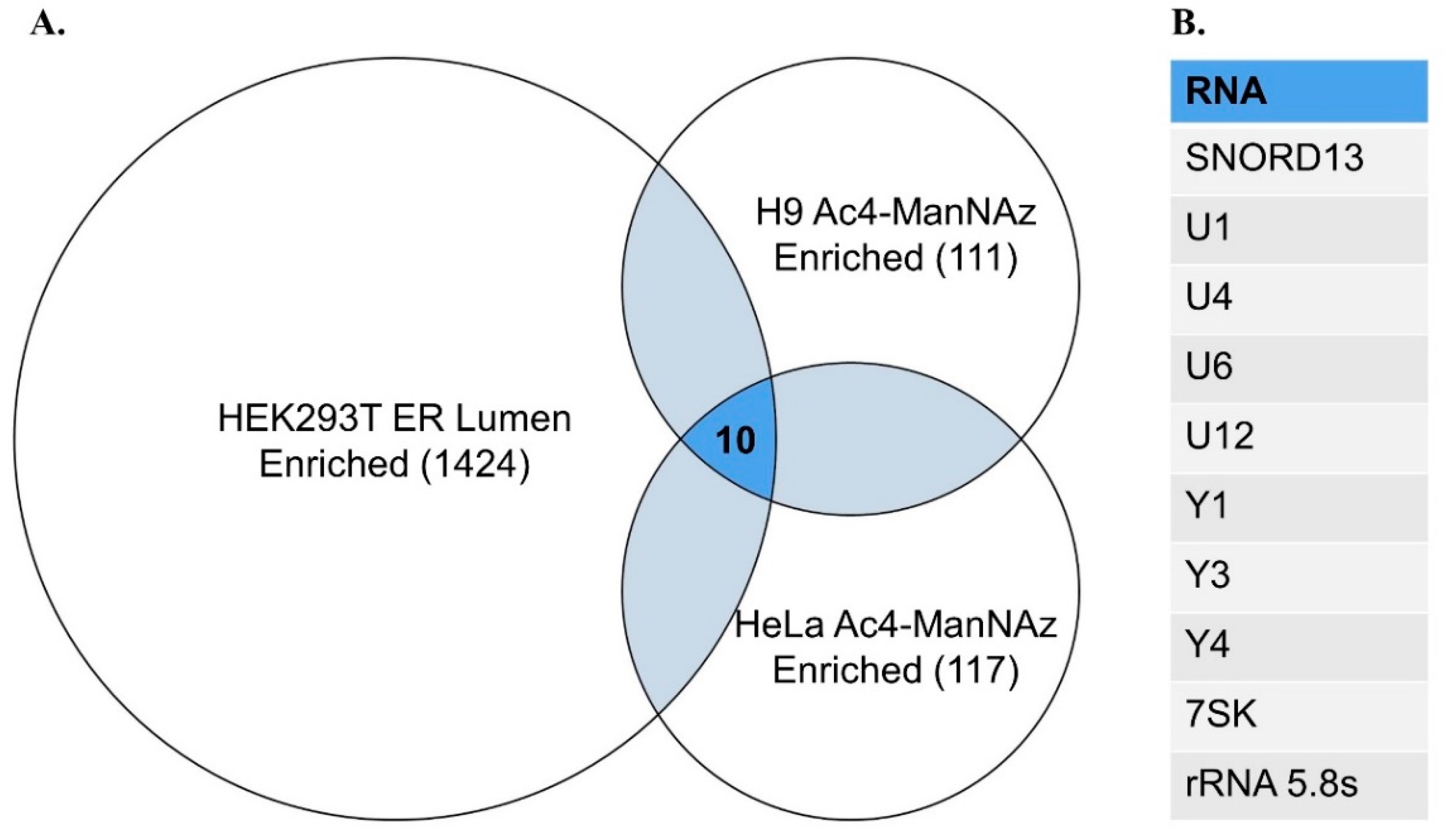

To assist future studies of glycoRNA, we have collated a list of high confidence glycosylated transcripts identified from existing sequencing analyses (

Figure 1). These high confidence sequences have been identified through Ac4-ManNAz labeling and enrichment in both HeLa and H9 cell lines, and exhibit a fold change ≥2 over total RNA samples from each cell line [

3]. Adding further utility, sequences were pruned to include only those transcripts found in a separate experiment, identifying RNAs enriched in the ER lumen of HEK293T cells to the same fold change threshold [

30]. These criteria were chosen to highlight glycoRNA sequences confirmed to be found at multiple steps of trafficking and presentation, making them ideal for a wide array of possible experiments.

7. Key Challenges

Since its discovery in 2021, glycoRNA has progressed from an oddity of glycobiology to a field of its own. Much about the biochemical properties and production of glycoRNA have already been elucidated, with new discoveries into its function and pathological significance emerging every day. This rapid pace of research, while encouraging, is still hindered by a number of key challenges to its progression. To expand as a field, glycoRNA research must overcome these challenges, which can largely be binned into those stemming from gaps in technology, and from gaps in theory.

At the forefront of technological challenges is the lack of ability to broadly detect glycoRNA regardless of glycan composition or transcript sequence. The majority of recent studies have employed click chemistry-based Ac4-ManNAz metabolic labeling for bulk glycoRNA detection. Studies often extrapolate the conclusions taken from this method as effecting global glycoRNA populations, when in fact only sialoglycoRNAs have been assayed. Mass spectrometry of glycans released from RNA isolates reveals that a large portion of glycoRNAs do not contain sialic acid, leaving many transcripts unstudied by this method [

3,

13].

Metabolic labeling also affects all sialylated polymers, making it unsuitable for microscopy due to cross-labeling on sialoglycoproteins. The development of ARPLA has addressed some of the weaknesses of metabolic labeling by requiring the dual presence of the glycan and RNA moieties in close proximity. However, ARPLA faces its own challenge by limiting glycoRNA detection to pre-determined transcripts with antisense sequences to a RISH probe. Depending on the purity of one’s RNA isolation method, metabolic labeling’s nonspecificity also increases the possibility of protein contamination. A recent method developed for isolation of sialoglycoRNAs found RNA isolates to be partially susceptible to mucinase digestion [

46]. Mucin proteins are heavily glycosylated, making them a troublesome contaminant while isolating non-protein glycoconjugates [

50]. Mucin contamination would particularly influence results based on the glycan moiety of glycoRNA, such as blotting for metabolic labels or mass spectrometry. This underscores the importance of proper quality control measures during glycoRNA experimentation.

The technological challenges facing glycoRNA are not wholly unique to this field, but are inherited from difficulties faced across glycobiology. Carbohydrates currently stand as the last biopolymer without specific methods of detection. Immunolabeling, one of the most widely used techniques for detection of proteins and small molecules, falls short against glycans. The binding domain of an antibody is only large enough to accommodate roughly 2 to 6 linear residues of a glycan, making specificity against individual glycan structures difficult to achieve [

51]. The enzymatic synthesis of glycans also presents challenges to validating antibody specificity, as individual glycans cannot be knocked out or overexpressed in vitro as proteins can. Illustrating this challenge, a recently compiled database of 1120 glycan-binding antibodies was found to recognize only 247 unique glycans out of roughly 7000 possible sequences in the mammalian glycome [

52]. Aptamers present a promising avenue to overcome this obstacle, as the DNA-based binding reagents can be rapidly generated and screened in large combinatorial libraries [

53].

The field also shares difficulties faced by small RNA researchers, particularly in sequencing. During library preparation, small RNA such as glycoRNA are more prone to over- or under-representation that long RNA, due to bias in adapter ligation [

54]. Additionally, small RNA are often repetitive or mobile within the genome, making standard alignment indices and assembly scaffolds unsuitable for mapping reads [

55]. Resources such as library preparation methods with reduced bias and specialized small RNA analysis pipelines are already being developed to address these challenges [

56,

57]. By adopting these methods and establishing standards for glycoRNA sequencing analysis, future sequencing efforts may more accurately capture the glycosylated transcriptome, and enable greater comparability between studies.

Despite technical challenges, modern techniques in molecular and cellular biology have enabled the development of a working model for glycoRNA production, presentation, and function. As discussed here, small RNA transcripts containing modified ribonucleosides are glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum, followed by transport and display on the cell surface. The next phase of glycoRNA research must expand and validate this model.

One of the most pressing questions that must be answered to complete the glycoRNA model is how does glycoRNA attach to the cell surface? Broadly speaking, there are two possible methods for this attachment: glycoRNA is either bound by proxy of another component of the cell surface or directly integrated into the plasma membrane. Precedence exists for both methods. Cell surface attachment by proxy is commonly employed by proteins to localize to the cell surface, such as beta-2-microglobulin (B2M). A component of the MHC Class I complex, B2M lacks a transmembrane domain, but achieves cell surface localization by non-covalently binding the MHC I alpha chain [

58]. glycoRNA is already known to cluster with autonomously produced csRBPs on the cell surface, providing support for a proxy model of attachment, although few csRBPs contain a transmembrane domain or GPI anchor [

40]. Additional mechanics would have to be involved for glycoRNA to attach via csRBPs.

Small RNA sequences have also been synthetically generated with phospholipid binding activity, as would be necessary for direct integration of glycoRNA into the plasma membrane. Analysis of these synthetic transcripts reveals no single conserved epitope responsible for lipid binding, but multiple transcripts contain poly-G stretches with increased local hydrophobicity, a necessary trait to integrate with the hydrophobic interior of the plasma membrane. The predicted structure of some transcripts also share structural features of common non-coding transcripts found in glycoRNA, such as hairpin regions, rigid double-helix stems, and single-stranded loops [

59].

Equally important to completing the glycoRNA model is the question of how the polymer relates to cell surface RNA as a whole. Like glycoRNA, cell surface RNA is growing into a nascent field, and preliminary research has unveiled several distinct or shared traits between the two molecules. glycoRNA and cell surface RNA differ when examining transcriptomic data. While glycoRNA is composed of small, non-coding RNAs, cell surface RNA sequencing data shows a preference for fragments of long coding and non-coding transcripts [

17,

18,

19]. Cell surface RNA expression is also more restricted than glycoRNA. Sequencing of cell surface RNA from PBMCs revealed strong expression on antigen-presenting cells, with much weaker expression on adaptive immune cells [

17]. Comparatively, glycoRNA has been found on almost every cell type yet tested.

The primary shared features between the two molecules include their localization to the cell surface and their observed function in immune cell adhesion. These traits have led some researchers to ask whether glycoRNA and cell surface RNA are separate observations of the same phenomenon. Studies focusing on cell surface RNA often fail to assess whether observed transcripts are glycosylated, leaving open the possibility that glycoRNA are in fact being studied. Similarly, many studies on glycoRNA employ extracellular RNase to remove the biopolymer from the cell surface, which affects all cell surface RNA regardless of glycosylation. Evidence that glycosylation machinery is necessary to detect RNA on the cell surface also contradicts the assertion that unmodified RNA exist in this environment [

3]. Experiments to more selectively probe the cell surface transcriptome will be needed to deconvolute past findings, explicitly asking whether cell surface RNA is an observation of glycoRNA. Making this distinction will be a crucial step toward a complete theory of glycoRNA.

8. Conclusions

The culmination of the research highlighted here is an early model of glycoRNA. In this model, small non-coding RNAs incorporate modified ribonucleosides over the course of normal synthesis [

15]. These transcripts are transported by an as-of-yet unidentified mechanism into the endoplasmic reticulum lumen, where oligosaccharyltransferase and other canonical glycosylation machinery contributes to the covalent attachment of glycan structures at modified bases [

3,

30]. Once modified, glycosylated transcripts are packaged and transported to the cell surface using vesicular trafficking [

24]. glycoRNA localizes to lipid rafts once on the cell surface, and is protected from extracellular RNase degradation by cell surface RNA binding proteins [

12,

24,

40]. These transcripts go on to interact with the extracellular environment, binding with siglec and selectin receptors through its glycan moiety to facilitate recruitment of immune cells, and acting as an entry point for cell-penetrating peptides [

3] [

12,

40]. Finally, cells regulate these activities by differentially expressing glycoRNA, as observed during immune differentiation and cancer progression [

3,

12,

24].

This model represents the limits of our current knowledge on glycoRNA, and with its development, it is an exciting time to consider the future of the field. Work within the field has so far been dominated by basic discovery research, driven by the question of what is glycoRNA and how does it function. With a model to base future studies around, research can expand to understand how the novel glycoconjugate impacts existing biological systems, and if it can be leveraged therapeutically.

We have highlighted several specific questions, hypotheses, and technical developments that are of immediate importance to expanding the model of glycoRNA, but several fields are also ripe for cross-disciplinary research. Cancer is one such area. Transcriptomic profiling has become a common tool to identify changes in gene expression during the growth and progression of cancers [

60]. By generating more diverse glycoRNA sequencing datasets from cancerous tissues and cell lines, these insights can be expanded to include changes to glycosylated transcripts. Changes in glycoRNA expression found in breast cancer bolster this possibility [

24].

Autoimmunity is another excellent candidate for cross-disciplinary research. Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) are prominent autoantigens, illiciting an immune response in disorders such as systemic lupus erethematosus [

27]. The appearance of glycoRNA in complex with csRBPs presents a new class of RNPs, one that is presumably accessible to immune surveillance due to their topology on the cell surface [

40]. The roles of glycoRNA in neutrophil recruitment and macrophage differentiation also present a possible link with autoimmunity, as many disorders originate from disregulation of innate immune cells [

12,

24,

61].

Finally, glycoRNA stands to benefit from studying its evolutionary biology. The glycoconjugate has been found in cell lines originating from human, mouse, and Chinese hamster tissues, indicating a common origin among these mammals and likely beyond [

3,

12]. The modified ribonucleosides through which glycans can covalently attach to RNA are also found in bacteria, making glycoRNA a possibility outside the animal kingdom [

16]. By identifying glycosylated transcripts in a more diverse set of species, future research may seek out the origins of glycoRNA, and expose what key functions drove its evolution.

These questions and more offer exciting avenues for future investigation. By presenting the current model of glycoRNA and providing resources on glycoRNA expression by cell line and transcript, we hope to have accelerated this research, and introduced new minds to this expanding field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ryan A. Flynn for his contributions towards this review, including comments on draft revisions, critical discussion of key studies, and sharing expert views on the outlook of the field.

Conflicts of Interest

J.V.P. was employed by Pfizer during the development of this review.

References

- Crick, F. Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molecular Biology of the Cell; Alberts, B. , Ed.; 4th ed.; Garland Science: New York, 2002; ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, R.A.; Pedram, K.; Malaker, S.A.; Batista, P.J.; Smith, B.A.H.; Johnson, A.G.; George, B.M.; Majzoub, K.; Villalta, P.W.; Carette, J.E.; et al. Small RNAs Are Modified with N-Glycans and Displayed on the Surface of Living Cells. Cell 2021, 184, 3109–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reily, C.; Stewart, T.J.; Renfrow, M.B.; Novak, J. Glycosylation in Health and Disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019, 15, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, C.A.; Horwitz, A.F. Integrin, a Transmembrane Glycoprotein Complex Mediating Cell-Substratum Adhesion. J Cell Sci Suppl 1987, 8, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, P.R.; Paulson, J.C.; Varki, A. Siglecs and Their Roles in the Immune System. Nat Rev Immunol 2007, 7, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A.; Lowe, J.B. Biological Roles of Glycans. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Freeze, H.H., Stanley, P., Bertozzi, C.R., Hart, G.W., Etzler, M.E., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor (NY), 2009 ISBN 978-0-87969-770-9.

- Boccaletto, P.; Machnicka, M.A.; Purta, E.; Piątkowski, P.; Bagiński, B.; Wirecki, T.K.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Ross, R.; Limbach, P.A.; Kotter, A.; et al. MODOMICS: A Database of RNA Modification Pathways. 2017 Update. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, D303–D307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, H.; Wu, A.; Peng, Y.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. Functions of N6-Methyladenosine and Its Role in Cancer. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmeier, M.; Wagner, M.; Ensfelder, T.; Korytiakova, E.; Thumbs, P.; Müller, M.; Carell, T. Synthesis and Structure Elucidation of the Human tRNA Nucleoside Mannosyl-Queuosine. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agard, N.J.; Prescher, J.A.; Bertozzi, C.R. A Strain-Promoted [3 + 2] Azide−Alkyne Cycloaddition for Covalent Modification of Biomolecules in Living Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15046–15047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Tang, W.; Torres, L.; Wang, X.; Ajaj, Y.; Zhu, L.; Luan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Cell Surface RNAs Control Neutrophil Recruitment. Cell 2024, 187, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming Bi; Zirui Zhang; Tao Wang; Hongwei Liang; Zhixin Tian A Draft of Human N-Glycans of glycoRNA. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.09.18.558371. [CrossRef]

- Trimble, R.B.; Tarentino, A.L. Identification of Distinct Endoglycosidase (Endo) Activities in Flavobacterium Meningosepticum: Endo F1, Endo F2, and Endo F3. Endo F1 and Endo H Hydrolyze Only High Mannose and Hybrid Glycans. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1991, 266, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Chai, P.; Till, N.A.; Hemberger, H.; Lebedenko, C.G.; Porat, J.; Watkins, C.P.; Caldwell, R.M.; George, B.M.; Perr, J.; et al. The Modified RNA Base acp3U Is an Attachment Site for N-Glycans in glycoRNA. Cell 2024, S0092867424008389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, M.; Ishiguro, K.; Akichika, S.; Miyauchi, K.; Suzuki, T. Biogenesis and Functions of Aminocarboxypropyluridine in tRNA. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, N.; Fan, X.; Zaleta-Rivera, K.; Nguyen, T.C.; Zhou, J.; Luo, Y.; Gao, J.; Fang, R.H.; Yan, Z.; Chen, Z.B.; et al. Natural Display of Nuclear-Encoded RNA on the Cell Surface and Its Impact on Cell Interaction. Genome Biol 2020, 21, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Xiao, H.; Hu, R.; Wang, G.; Niu, D.; Shao, P.-L.; Yang, J.; Jin, Z.; et al. A Novel Cell Membrane-Associated RNA Extraction Method and Its Application in the Discovery of Breast Cancer Markers. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 11706–11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.; Guo, X.; Teng, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, F.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Q.; Luo, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Discovery of Plasma Membrane-Associated RNAs through APEX-Seq. Cell Biochem Biophys 2021, 79, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.F.; Puerta-Fernandez, E.; Wallace, J.G.; Breaker, R.R. Association of OLE RNA with Bacterial Membranes via an RNA-Protein Interaction. Mol Microbiol 2011, 79, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.; Mayhew, E. The Presence of Ribonucleic Acid within the Peripheral Zones of Two Types of Mammalian Cell. Journal Cellular Physiology 1966, 68, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laktionov, P.P.; Tamkovich, S.N.; Rykova, E.Y.; Bryzgunova, O.E.; Starikov, A.V.; Kuznetsova, N.P.; Vlassov, V.V. Cell-Surface-Bound Nucleic Acids: Free and Cell-Surface-Bound Nucleic Acids in Blood of Healthy Donors and Breast Cancer Patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004, 1022, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozkin, E.S.; Laktionov, P.P.; Rykova, E.Y.; Vlassov, V.V. Extracellular Nucleic Acids in Cultures of Long-Term Cultivated Eukaryotic Cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004, 1022, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Guo, W.; Mou, Q.; Shao, X.; Lyu, M.; Garcia, V.; Kong, L.; Lewis, W.; Ward, C.; Yang, Z.; et al. Spatial Imaging of glycoRNA in Single Cells with ARPLA. Nat Biotechnol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezgin, E.; Levental, I.; Mayor, S.; Eggeling, C. The Mystery of Membrane Organization: Composition, Regulation and Roles of Lipid Rafts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, P.; Lebedenko, C.G.; Flynn, R.A. RNA Crossing Membranes: Systems and Mechanisms Contextualizing Extracellular RNA and Cell Surface GlycoRNAs. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2023, 24, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, D.R.; Zhao, Y.; Belk, J.A.; Zhao, Y.; Casey, K.M.; Chen, D.C.; Li, R.; Yu, B.; Srinivasan, S.; Abe, B.T.; et al. Xist Ribonucleoproteins Promote Female Sex-Biased Autoimmunity. Cell 2024, 187, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, E.; Patuzzo, G.; Lunardi, C. Autoantigens and Autoantibodies in the Pathogenesis of Sjögren’s Syndrome. In Sjogren’s Syndrome; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 141–156 ISBN 978-0-12-803604-4.

- Harada, Y.; Ohkawa, Y.; Kizuka, Y.; Taniguchi, N. Oligosaccharyltransferase: A Gatekeeper of Health and Tumor Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, R.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zou, P. Enzyme-Mediated Proximity Labeling Identifies Small RNAs in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Lumen. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 1844–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Cong, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, Q.; Yan, C.; Gong, D. Structural Insight into the Human SID1 Transmembrane Family Member 2 Reveals Its Lipid Hydrolytic Activity. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, E.H.; Hunter, C.P. Transport of dsRNA into Cells by the Transmembrane Protein SID-1. Science 2003, 301, 1545–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Smith, B.R.C.; Elgass, K.D.; Creed, S.J.; Cheung, S.; Tate, M.D.; Belz, G.T.; Wicks, I.P.; Masters, S.L.; Pang, K.C. SIDT1 Localizes to Endolysosomes and Mediates Double-Stranded RNA Transport into the Cytoplasm. The Journal of Immunology 2019, 202, 3483–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, D.; Gershlick, D.C. Direct Trafficking Pathways from the Golgi Apparatus to the Plasma Membrane. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2020, 107, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W. SNAREs and Traffic. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005, 1744, 120–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, N.; Daly, J.; Drummond-Guy, O.; Krishnamoorthy, V.; Stark, J.C.; Riley, N.M.; Williams, K.C.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Wisnovsky, S. The Glycoimmune Checkpoint Receptor Siglec-7 Interacts with T-Cell Ligands and Regulates T-Cell Activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2024, 300, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, S.D.; Bertozzi, C.R. The Selectins and Their Ligands. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 1994, 6, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEver, R.P.; Zhu, C. Rolling Cell Adhesion. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2010, 26, 363–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczera, P.; Martin, L.; Marx, G.; Schuerholz, T. The Ribonuclease A Superfamily in Humans: Canonical RNases as the Buttress of Innate Immunity. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan Perr; Andreas Langen; Karim Almahayni; Gianluca Nestola; Peiyuan Chai; Charlotta G. Lebedenko; Regan Volk; Reese M. Caldwell; Malte Spiekermann; Helena Hemberger; et al. RNA Binding Proteins and glycoRNAs Form Domains on the Cell Surface for Cell Penetrating Peptide Entry. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.09.04.556039. [CrossRef]

- Bottens, R.A.; Yamada, T. Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) as Therapeutic and Diagnostic Agents for Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabulo, S.; Cardoso, A.L.; Mano, M.; De Lima, M.C.P. Cell-Penetrating Peptides-Mechanisms of Cellular Uptake and Generation of Delivery Systems. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2010, 3, 961–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipfert, J.; Doniach, S.; Das, R.; Herschlag, D. Understanding Nucleic Acid-Ion Interactions. Annu Rev Biochem 2014, 83, 813–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, A.D.; Pabo, C.O. Cellular Uptake of the Tat Protein from Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Shirley, N.; Bleackley, M.; Dolan, S.; Shafee, T. Transcriptomics Technologies. PLoS Comput Biol 2017, 13, e1005457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemberger, H.; Chai, P.; Lebedenko, C.G.; Caldwell, R.M.; George, B.M.; Flynn, R.A. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Native glycoRNAs 2023.

- Yeini, E.; Ofek, P.; Pozzi, S.; Albeck, N.; Ben-Shushan, D.; Tiram, G.; Golan, S.; Kleiner, R.; Sheinin, R.; Israeli Dangoor, S.; et al. P-Selectin Axis Plays a Key Role in Microglia Immunophenotype and Glioblastoma Progression. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, S.S.; Reis, C.A. Glycosylation in Cancer: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, E.; Macauley, M.S. Hypersialylation in Cancer: Modulation of Inflammation and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.C. Mucins: Structure, Function, and Role in Pulmonary Diseases. Am J Physiol 1992, 263, L413–L429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.D. The Repertoire of Glycan Determinants in the Human Glycome. Mol. BioSyst. 2009, 5, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, E.; Flanagan, N.; Gildersleeve, J.C. Perspectives on Anti-Glycan Antibodies Gleaned from Development of a Community Resource Database. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, H.; Jacobson, O.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Niu, G.; Chen, X. Combinatorial Screening of DNA Aptamers for Molecular Imaging of HER2 in Cancer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dard-Dascot, C.; Naquin, D.; d’Aubenton-Carafa, Y.; Alix, K.; Thermes, C.; Van Dijk, E. Systematic Comparison of Small RNA Library Preparation Protocols for Next-Generation Sequencing. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, B.; Gao, X. Repetitive DNA Sequence Detection and Its Role in the Human Genome. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Lohman, G.J.S.; Guan, S. A Low-Bias and Sensitive Small RNA Library Preparation Method Using Randomized Splint Ligation. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayakin, P. sRNAflow: A Tool for the Analysis of Small RNA-Seq Data. ncRNA 2024, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berko, D.; Carmi, Y.; Cafri, G.; Ben-Zaken, S.; Sheikhet, H.M.; Tzehoval, E.; Eisenbach, L.; Margalit, A.; Gross, G. Membrane-Anchored Β2-Microglobulin Stabilizes a Highly Receptive State of MHC Class I Molecules. The Journal of Immunology 2005, 174, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khvorova, A.; Kwak, Y.G.; Tamkun, M.; Majerfeld, I.; Yarus, M. RNAs That Bind and Change the Permeability of Phospholipid Membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 10649–10654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supplitt, S.; Karpinski, P.; Sasiadek, M.; Laczmanska, I. Current Achievements and Applications of Transcriptomics in Personalized Cancer Medicine. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saferding, V.; Blüml, S. Innate Immunity as the Trigger of Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Journal of Autoimmunity 2020, 110, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).