Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

04 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

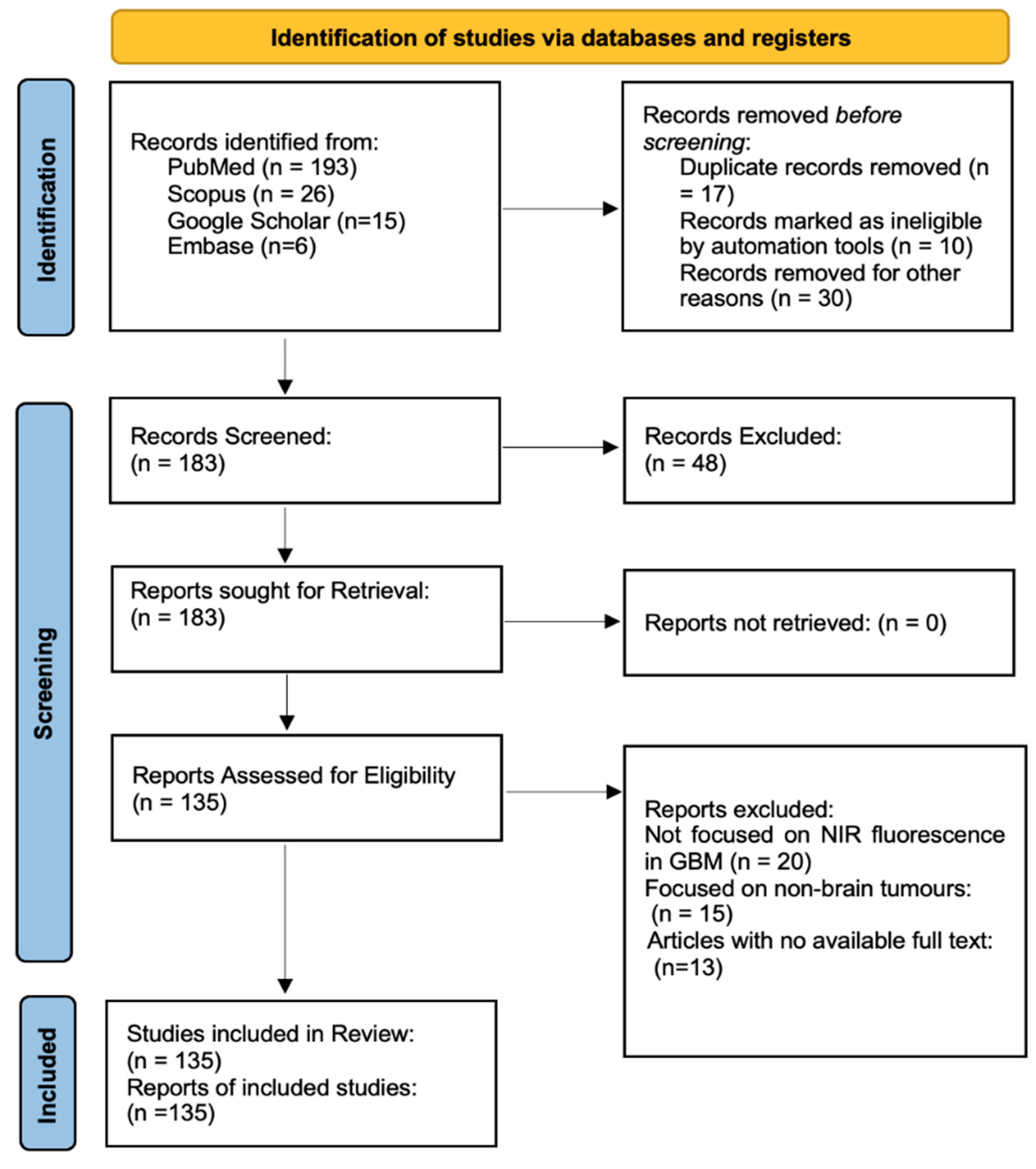

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Guidelines

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusions

- Focus on the use of NIR fluorescence imaging specifically in GBM surgery.

- Report measurable surgical outcomes, such as GTR rates or complications.

- Include patient outcomes, such as progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS).

- Provide access to full-text articles with enough data for qualitative analysis.

2.3.2. Exclusions

- Focused on tumors outside the brain or other unrelated cancers.

- Were reviews, editorials, or opinion pieces without original data.

- Lacked outcomes related to NIR-guided surgery.

- Did not provide full-text access.

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Synthesis of Results

3. Infrared Fluorescence-Guided Surgery in Glioblastoma Resection

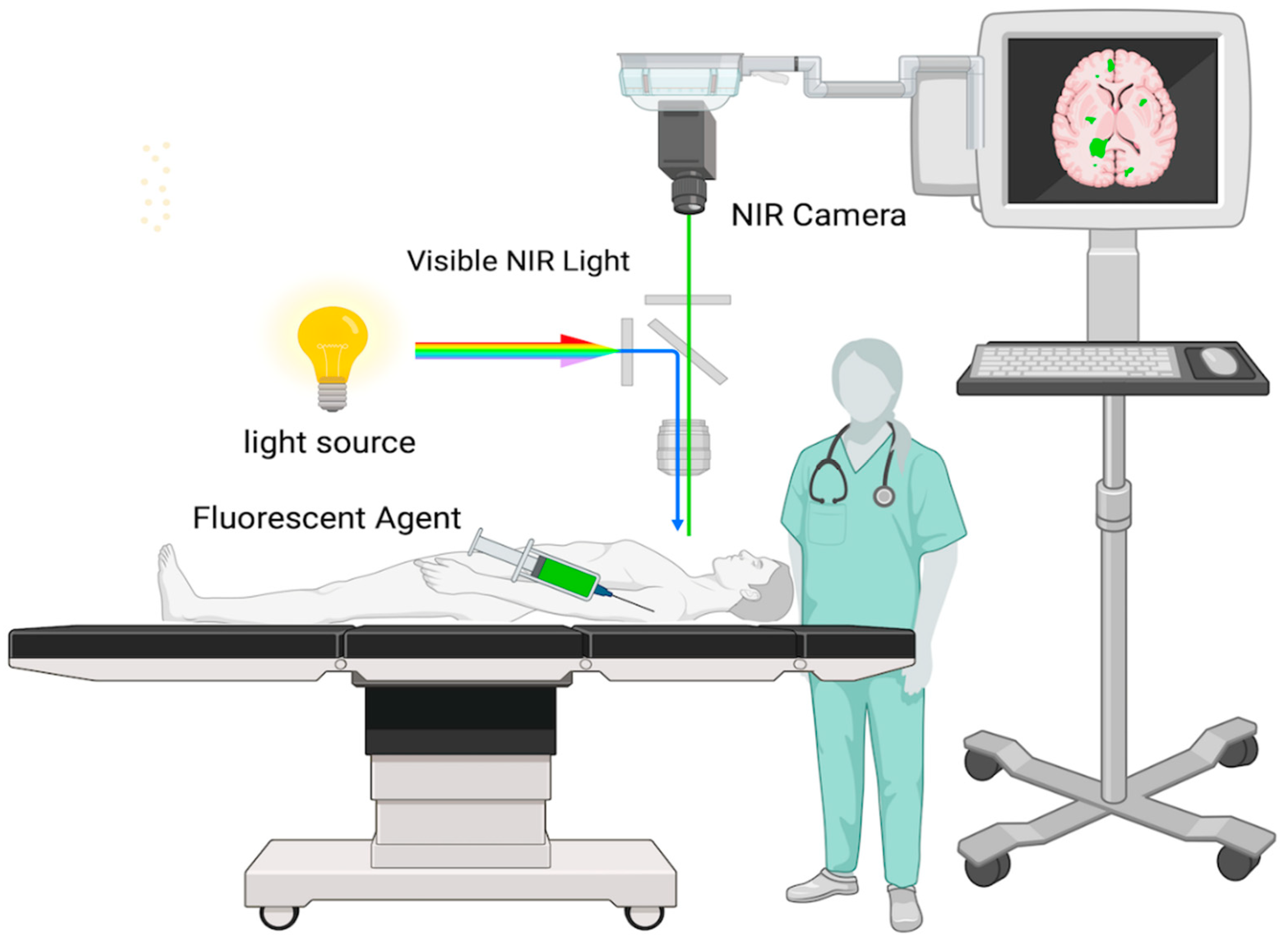

3.1. Mechanism of Action

3.2. Techniques of Infrared Fluorescence Imaging

3.3. Applications of Near-Infrared Imaging in GBM

3.4. Types of Fluorophores for Intraoperative Near-Infrared Imaging

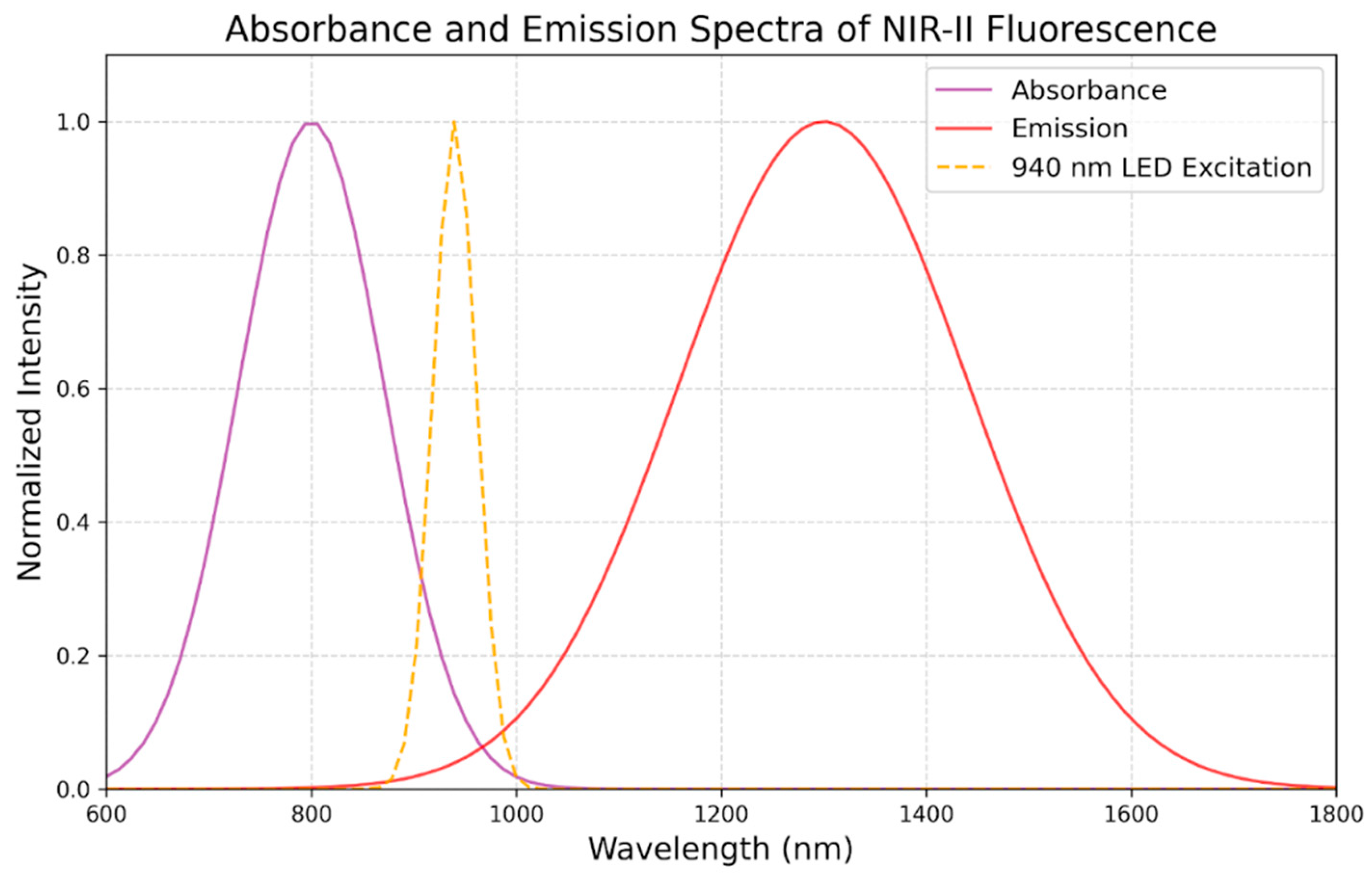

3.5. Optimal Wavelength and Technical Considerations of NIR in GBM

4. Imaging Modalities in Glioblastoma Surgery

4.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

4.2. Computed Tomography (CT)

4.3. Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

4.4. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA) Fluorescence-Guided Surgery

5. Enhancing Surgical Precision and Patient Outcomes

6. Clinical Evidence for Near-Infrared Imaging in GBM

7. Results

7.1. Improved Tumor Visualization.

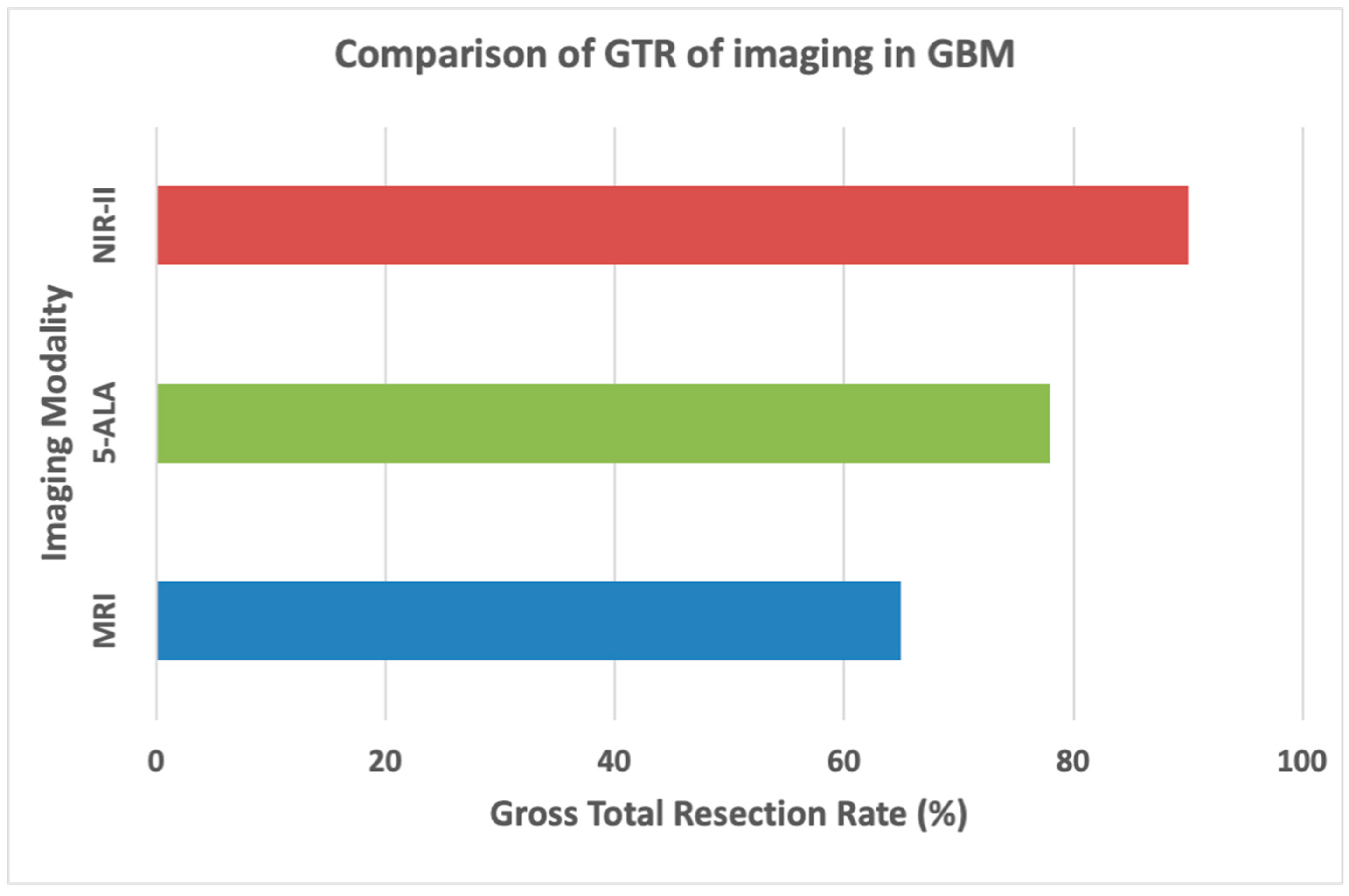

7.2. Increased Gross Total Resection (GTR) Rates

7.3. Enhanced Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS)

7.4. Reduction in Postoperative Neurological Deficits

7.5. Increased Operational Efficiency and Cost-Effectiveness

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

References

- Koshy M, Villano JL, Dolecek TA, Howard A, Mahmood U, Chmura SJ, et al. Improved survival time trends for glioblastoma using the SEER 17 population-based registries. J Neurooncol. 2012, 107, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonosi L, Marrone S, Benigno UE, Buscemi F, Musso S, Porzio M, et al. Maximal safe resection in glioblastoma surgery: A Systematic Review of advanced intraoperative image-guided techniques. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Robles P, Fiest KM, Frolkis AD, Pringsheim T, Atta C, St Germaine-Smith C, et al. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of primary brain tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2015, 17, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim J, Park Y, Ahn JW, Hwang SJ, Kwon H, Sung KS, et al. Maximal surgical resection and adjuvant surgical technique to prolong the survival of adult patients with thalamic glioblastoma. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0244325. [Google Scholar]

- Molinaro AM, Hervey-Jumper S, Morshed RA, Young J, Han SJ, Chunduru P, et al. Association of maximal extent of resection of contrast-enhanced and non-contrast-enhanced tumor with survival within molecular subgroups of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanai N, Polley M-Y, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seker-Polat F, Pinarbasi Degirmenci N, Solaroglu I, Bagci-Onder T. Tumor cell infiltration into the brain in glioblastoma: From mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Velazquez M, Al-Kharboosh R, Jeanneret S, Vazquez-Ramos C, Mahato D, Tavanaiepour D, et al. Advances in brain tumor surgery for glioblastoma in adults. Brain Sci. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Åke S, Hartelius L, Jakola AS, Antonsson M. Experiences of language and communication after brain-tumour treatment: A long-term follow-up after glioma surgery. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2023, 33, 1225–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken DJ, Schupper AJ, Lakomkin N, Malcolm J, Painton Bray D, Hadjipanayis CG. Turning on the light for brain tumor surgery: A 5-aminolevulinic acid story. Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24, S52–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipanayis CG, Widhalm G, Stummer W. What is the surgical benefit of utilizing 5-aminolevulinic acid for fluorescence-guided surgery of malignant gliomas? Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suero Molina E, Schipmann S, Stummer W. Maximizing safe resections: the roles of 5-aminolevulinic acid and intraoperative MR imaging in glioma surgery-review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2019, 42, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiesel B, Freund J, Reichert D, Wadiura L, Erkkilae MT, Woehrer A, et al. 5-ALA in suspected low-grade gliomas: Current role, limitations, and new approaches. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 699301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop CF, Veys I, Bormans A, Larsimont D, Liberale G. Fluorescence imaging for real-time detection of breast cancer tumors using IV injection of indocyanine green with non-conventional imaging: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies of perioperative imaging technologies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024, 204, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clinical implications of near-infrared fluorescence imaging in cancer. Future Oncol. 2009, 5, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu R, Jiao D, Long Q, Li X, Shan K, Kong X, et al. Highly bright aggregation-induced emission nanodots for precise photoacoustic/NIR-II fluorescence imaging-guided resection of neuroendocrine neoplasms and sentinel lymph nodes. Biomaterials. 2022, 289, 121780. [Google Scholar]

- van Manen L, de Muynck LDAN, Baart VM, Bhairosingh S, Debie P, Vahrmeijer AL, et al. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of pancreatic cancer using a fluorescently labelled anti-CEA Nanobody probe: A preclinical study. Biomolecules. 2023, 13, 618. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah Z, Roy S, Gu J, Ko Soe S, Jin J, Guo B. NIR-II fluorescent probes for fluorescence-imaging-guided tumor surgery. Biosensors (Basel). 2024, 14, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Chen Y, Wang B, Gao X, Wu M. Recent progress in second near-infrared (NIR-II) fluorescence imaging in cancer. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 1044. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li Y, Su J, Zhang L, Liu H. Progression in near-infrared fluorescence imaging technology for lung cancer management. Biosensors (Basel). 2024, 14, 501. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Johnson J, Peck A, Xie Q. Near infrared fluorescent imaging of brain tumor with IR780 dye incorporated phospholipid nanoparticles. J Transl Med. 2017, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehelgerdi M, Chehelgerdi M, Allela OQB, Pecho RDC, Jayasankar N, Rao DP, et al. Progressing nanotechnology to improve targeted cancer treatment: overcoming hurdles in its clinical implementation. Mol Cancer. 2023, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang F, Weng Y, Geng J, Zhu J. A narrative review of indocyanine green near-infrared fluorescence imaging technique: a new application in thoracic surgery. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2021, 3, 35–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho SS, Salinas R, Lee JYK. Indocyanine-green for fluorescence-guided surgery of brain tumors: Evidence, techniques, and practical experience. Front Surg. 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Lee JYK, Pierce JT, Zeh R, Cho SS, Salinas R, Nie S, et al. Intraoperative near-infrared optical contrast can localize brain metastases. World Neurosurg. 2017, 106, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho SS, Teng CW, Ramayya A, Buch L, Hussain J, Harsch J, et al. Surface-registration frameless stereotactic navigation is less accurate during prone surgeries: Intraoperative near-infrared visualization using Second Window Indocyanine Green offers an adjunct. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020, 22, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee JYK, Pierce JT, Thawani JP, Zeh R, Nie S, Martinez-Lage M, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent image-guided surgery for intracranial meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri G, Cofano F, Salvati LF, Monticelli M, Zeppa P, Perna GD, et al. Fluorescence-Guided Surgery for High-Grade Gliomas: State of the Art and New Perspectives. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021, 20, 15330338211021605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuro A, DeAngelis LM. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013, 310, 1842–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanderi T, Munakomi S, Gupta V. Glioblastoma Multiforme. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Pichlmeier U, Bink A, Schackert G, Stummer W. Resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: An RTOG recursive partitioning analysis of ALA study patients. Neuro Oncol. 2008, 10, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pepa GM, Sabatino G, la Rocca G. “enhancing vision” in high grade glioma surgery: A feasible integrated 5-ALA + CEUS protocol to improve radicality. World Neurosurg. 2019, 129, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri R, Raimondo S, Tiddia C, Sammarco D, Cofano F, Zeppa P, et al. Glioma surgery: From preservation of motor skills to conservation of cognitive functions. J Clin Neurosci. 2019, 70, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewelt C, Nemes A, Senner V, Wölfer J, Brokinkel B, Stummer W, et al. Fluorescence in neurosurgery: Its diagnostic and therapeutic use. Review of the literature. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015, 148, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri R, Zenga F, Fontanella MM, Cofano F, Agnoletti A, Spena G, et al. Glioma surgery: Technological advances to achieve a maximal safe resection. Surg Technol Int. 2015, 27, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri R, Meneghini S, Agnoletti A, Tardivo V, Vincitorio F, Prino E, et al. Intraoperative ultrasound and 5-ALA: the two faces of the same medal? J Neurosurg Sci. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White HW, Naveed AB, Campbell BR, Lee Y-J, Baik FM, Topf M, et al. Infrared fluorescence-guided surgery for tumor and metastatic lymph node detection in head and neck cancer. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 2024, 6, e230178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rocca G, Della Pepa GM, Menna G, Altieri R, Ius T, Rapisarda A, et al. State of the art of fluorescence guided techniques in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg Sci. 2020, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009, 339, b2700–b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis DG, White ML, Hayasaka S, Warren DE, Wilson TW, Aizenberg MR. Accuracy analysis of fMRI and MEG activations determined by intraoperative mapping. Neurosurg Focus. 2020, 48, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson BM, Wen PY, Cloughesy TF. Modified criteria for radiographic response assessment in glioblastoma clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2017, 14, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewelt C, Floeth FW, Felsberg J, Steiger HJ, Sabel M, Langen K-J, et al. Finding the anaplastic focus in diffuse gliomas: The value of Gd-DTPA enhanced MRI, FET-PET, and intraoperative, ALA-derived tissue fluorescence. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011, 113, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essig M, Shiroishi MS, Nguyen TB, Saake M, Provenzale JM, Enterline D, et al. Perfusion MRI: The five most frequently asked technical questions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013, 200, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink JR, Muzi M, Peck M, Krohn KA. Multimodality brain tumor imaging: MR imaging, PET, and PET/MR imaging. J Nucl Med. 2015, 56, 1554–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster M-T, Hattingen E, Senft C, Gasser T, Seifert V, Szelényi A. Navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imaging: Advanced adjuncts in preoperative planning for central region tumors. Neurosurgery. 2011, 68, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara N, Sakatani K, Katayama Y, Murata Y, Hoshino T, Fukaya C, et al. Evoked-cerebral blood oxygenation changes in false-negative activations in BOLD contrast functional MRI of patients with brain tumors. Neuroimage. 2004, 21, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstock JD, Gary SE, Klinger N, Valdes PA, Ibn Essayed W, Olsen HE, et al. Standard clinical approaches and emerging modalities for glioblastoma imaging. Neurooncol Adv. 2022, 4, vdac080. [Google Scholar]

- Martucci M, Russo R, Giordano C, Schiarelli C, D’Apolito G, Tuzza L, et al. Advanced magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of treated glioblastoma: A pictorial essay. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zikou A, Sioka C, Alexiou GA, Fotopoulos A, Voulgaris S, Argyropoulou MI. Radiation necrosis, pseudoprogression, pseudoresponse, and tumor recurrence: Imaging challenges for the evaluation of treated gliomas. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2018, 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihashi T, Dahabreh IJ, Terasawa T. Diagnostic accuracy of PET for recurrent glioma diagnosis: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013, 34, 944–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galldiks N, Stoffels G, Filss C, Rapp M, Blau T, Tscherpel C, et al. The use of dynamic O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET in the diagnosis of patients with progressive and recurrent glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Glaudemans AWJM, Enting RH, Heesters MAAM, Dierckx RAJO, van Rheenen RWJ, Walenkamp AME, et al. Value of 11C-methionine PET in imaging brain tumours and metastases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013, 40, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. O-(2-[(18)F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine. Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database (MICAD). Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2004.

- Chuanting L, Bin A, Yan L, Hengtao Q, Lebin W. Susceptibility-weighted imaging in grading brain astrocytomas. Eur J Radiol. 2010, 75, e81–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen H-J, et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischkulnig M, Roetzer-Pejrimovsky T, Lötsch-Gojo D, Kastner N, Bruckner K, Prihoda R, et al. Heme biosynthesis factors and 5-ALA induced fluorescence: Analysis of mRNA and protein expression in fluorescing and non-fluorescing gliomas. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Maragkos GA, Schüpper AJ, Lakomkin N, Sideras P, Price G, Baron R, et al. Fluorescence-guided high-grade glioma surgery more than four hours after 5-aminolevulinic acid administration. Front Neurol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko S, Suero Molina E, Sporns P, Schipmann S, Black D, Stummer W. Fluorescence real-time kinetics of protoporphyrin IX after 5-ALA administration in low-grade glioma. J Neurosurg. 2022, 136, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widhalm G, Olson J, Weller J, Bravo J, Han SJ, Phillips J, et al. The value of visible 5-ALA fluorescence and quantitative protoporphyrin IX analysis for improved surgery of suspected low-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2020, 133, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senders JT, Muskens IS, Schnoor R, Karhade AV, Cote DJ, Smith TR, et al. Agents for fluorescence-guided glioma surgery: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical results. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017, 159, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stummer W, Tonn J-C, Goetz C, Ullrich W, Stepp H, Bink A, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-derived tumor fluorescence: the diagnostic accuracy of visible fluorescence qualities as corroborated by spectrometry and histology and postoperative imaging. Neurosurgery. 2014, 74, 310–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupper AJ, Baron RB, Cheung W, Rodriguez J, Kalkanis SN, Chohan MO, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid for enhanced surgical visualization of high-grade gliomas: a prospective, multicenter study. J Neurosurg. 2022, 136, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljamel, S. 5-ALA fluorescence image guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme: A meta-analysis of the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2015, 16, 10443–10456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su X, Huang Q-F, Chen H-L, Chen J. Fluorescence-guided resection of high-grade gliomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2014, 11, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suero Molina E, Stögbauer L, Jeibmann A, Warneke N, Stummer W. Validating a new generation filter system for visualizing 5-ALA-induced PpIX fluorescence in malignant glioma surgery: a proof of principle study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020, 162, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho SS, Salinas R, De Ravin E, Teng CW, Li C, Abdullah KG, et al. Near-infrared imaging with second-window indocyanine green in newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas predicts gadolinium enhancement on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020, 22, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulos D, Strantzalis G, Gavra M, Korfias S, Karydakis P. The impact of intra-operative magnetic resonance imaging and 5-ALA in the achievement of gross total resection of gliomas: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Med Res Arch. 2022; 10. [CrossRef]

- Lai J, Deng G, Sun Z, Peng X, Li J, Gong P, et al. Scaffolds biomimicking macrophages for a glioblastoma NIR-Ib imaging guided photothermal therapeutic strategy by crossing Blood-Brain Barrier. Biomaterials. 2019, 211, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikarpov DM, Campbell DH, McRobb LS, Wu J, Lund ME, Lu Y, et al. Near-infrared molecular imaging of glioblastoma by Miltuximab®-IRDye800CW as a potential tool for fluorescence-guided surgery. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel D, Sagong B, Teh J, Zhang Y, Wagner S, Wang H, et al. Near infrared fluorescent nanoplatform for targeted intraoperative resection and chemotherapeutic treatment of glioblastoma. ACS Nano. 2020, 14, 8392–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaguno-Munive M, Villalba-Abascal W, Avilés-Salas A, Garcia-Lopez P. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging in preclinical models of glioblastoma. J Imaging. 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Kang D, Kim HS, Han S, Lee Y, Kim Y-P, Lee DY, et al. A local water molecular-heating strategy for near-infrared long-lifetime imaging-guided photothermal therapy of glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Li C, Shi X, Zhang J, Jia X, Hu Z, et al. Near-infrared II fluorescence-guided glioblastoma surgery targeting monocarboxylate transporter 4 combined with photothermal therapy. EBioMedicine. 2024, 106, 105243. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JYK, Thawani JP, Pierce J, Zeh R, Martinez-Lage M, Chanin M, et al. Intraoperative near-infrared optical imaging can localize gadolinium-enhancing gliomas during surgery. Neurosurgery. 2016, 79, 856–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller SE, Tummers WS, Teraphongphom N, van den Berg NS, Hasan A, Ertsey RD, et al. First-in-human intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging of glioblastoma using cetuximab-IRDye800. J Neurooncol. 2018, 139, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao C, Jin Z, Shi X, Zhang Z, Xiao A, Yang J, et al. First clinical investigation of near-infrared window IIa/IIb fluorescence imaging for precise surgical resection of gliomas. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2022, 69, 2404–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi X, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Cao C, Cheng Z, Hu Z, et al. Near-infrared window II fluorescence image-guided surgery of high-grade gliomas prolongs the progression-free survival of patients. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2022, 69, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsugu A, Ishizaka H, Mizokami Y, Osada T, Baba T, Yoshiyama M, et al. Impact of the combination of 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence with intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging-guided surgery for glioma. World Neurosurg. 2011, 76, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Description |

| Fluorescence Microscopy | Using this technique, the fluorescence released by the tumor during excision is seen using a surgical microscope fitted with a NIR filter. This enables the surgeon to keep an eye on the borders of the tumor while performing surgery. |

| NIR Imaging Systems | These are specific camera systems that display NIR fluorescence on an operating room screen upon detection. This allows the surgeon to see the fluorescence in real-time and can help spot tiny tumor remnants that could otherwise go undetected. |

| Handheld NIR Detectors | Certain methods view and detect near-infrared fluorescence using portable instruments. These can be helpful in confirming that there is no remaining tumor tissue following excision by scanning the operative field. |

| Fluorophore | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) | Brightness (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Strengths | Limitations |

| 5-ALA / PPIX | 405 | 635 | 400 | Good for tumor margin identification | Low brightness, limited penetration |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | 805 | 830 | 11,000 | High penetration, minimal autofluorescence | Smaller Stokes shift, needs precise calibration |

| Fluorescein | 489 | 515 | 75,000 | Excellent for surface imaging | Poor deep tissue visualization |

| Advantage | Explanation |

| Deep Tissue Penetration | Compared to visible light, NIR light at these wavelengths can enter tissues more deeply. This makes it possible to find tumors that are beneath the brain's surface, which is crucial for glioblastoma surgery because these tumors frequently invade deeper brain regions. |

| Reduced Tissue Autofluorescence | Fluorescence imaging may be hampered by autofluorescence from nearby tissues, which lessens the contrast between the tumor and healthy tissue. By reducing autofluorescence, NIR wavelengths improve the signal-to-noise ratio and tumor visualization accuracy. |

| Compatibility with Fluorophores | The NIR region is where the peak excitation and emission wavelengths of fluorophores, such as indocyanine green (ICG), oc cur. Optimizing the image clarity and achieving maximal fluorescence intensity may be achieved by matching the wavelength to the characteristics of the fluorophore. |

| Minimized Light Scattering | At NIR wavelengths, there is less light scattering, which enhances contrast and resolution in images. This is especially crucial for recognizing tiny residual tumor deposits and for picking out minute features in the tumor margins. |

| Safety | Compared to other wavelengths, such as ultraviolet or blue light, NIR light is less damaging to tissues. Because of this, using it for an extended period of time during surgery is safer and lowers the danger of phototoxicity. |

| Study | NIR Agent/Technology | Findings | Survival Impact |

| Lai et al. [68] |

MDINPs (IR-792 dye) | Clear tumor visualization, photothermal therapy, extended survival by 6-8 days | Extended median survival to 22 days |

| Polikarpov et al. [69]. |

Mituximab®-IR800 | High tumor-to-background ratio (TBR: 10.1 ± 2.8), no adverse events | High specificity and safety; supports clinical use |

| Reichel et al. [70] |

HMC-FMX / PTX/CDDP | 28-72% survival increase with HMC-FMX + PTX/CDDP | 32 to 55 days survival with combination therapy |

| Dang et al. [72] |

Nd-Yb Co-doped NPs | Reduced tumor volume by 78.9%, effective tumor ablation with 1.0 μm NIR light | Improved survival with high-resolution imaging |

| Zhao et al. [73]. |

NIR-II with MCT4 probe | High SBR (2.8 intraoperative, 6.3 postoperative), robust BBB penetration | Supports survival via photothermal therapy |

| Lee et al.[74] | Second Window ICG | SBR of 9.5 ± 0.8; improved resection accuracy through intact dura; no adverse effects | Enhanced precision and safety with ICG fluorescence |

| Miller et al. [75]. |

Fluorescently Labeled Antibodies | Safe, feasible for human use, accurate tumor margin detection | Extended PFS and reduced residual tumor |

| Cao et al. [76]. |

NIR-IIa/IIb Imaging Instruments | Improved vascular resolution, reduced blood loss | Enhanced intraoperative safety and survival |

| Shi et al. [77] |

NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging | 100% complete resection rate, superior to 5-ALA and FS | 9-10 months PFS, 19-20 months OS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).