1. Introduction

Advancements in neurosurgical oncology have continuously driven the development of novel technologies designed to improve surgical precision and patient outcomes. Among these innovations, intraoperative neuroimaging has evolved significantly, allowing for more extensive tumor resections and minimizing neurological risks [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In various brain tumor cases, the extent of tumor removal is closely associated with improved survival rates and responses to adjuvant therapies [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, refining surgical techniques to maximize tumor excision remains a key objective in neurosurgery [

8].

Various intraoperative imaging modalities are available to neurosurgeons, including intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (IOMRI), intraoperative computed tomography (IOCT), intraoperative ultrasonography (IOUS), and fluorescence-guided methods such as sodium fluorescein (SF) and 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) [

2,

4]. These imaging techniques are frequently integrated into standard neurosurgical workflows and neuronavigation systems [

4]. Each modality presents distinct advantages and limitations, and there is no universally accepted gold standard [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The selection of an imaging approach is typically influenced by a combination of surgeon preference and institutional resources [

4]. A primary challenge in achieving maximal resection is encountered in cases where tumor boundaries are poorly defined, making it difficult to differentiate tumor tissue from surrounding brain structures [

2].

Gliomas are the most common primary brain tumors in adults, with an estimated incidence of 3–5 cases per 100,000 people annually [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Although these tumors can develop at any age and in various regions of the central nervous system, they predominantly occur intracranially in individuals aged 50–60 years [

16]. The World Health Organization classifies gliomas on the basis of their cellular origin—such as astrocytic or oligodendroglial—and histological grade [

20]. Among these, high-grade gliomas (HGGs), including grade 3 and 4 tumors, are particularly aggressive and associated with poor prognoses [

19].

Despite significant advancements in neurosurgical techniques and ongoing research, glioblastomas and other HGGs remain highly lethal, with the 5-year survival rates still <5% [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Total gross resection (GTR) has been identified as a crucial factor in improving both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). However, complete tumor removal is often unachievable in cases where tumors are adjacent to or involve critical brain structures, because aggressive resection in these regions could result in severe functional impairment [

21].

Among intraoperative imaging techniques, IOUS has gained recognition as a valuable tool for real-time tumor localization and resection assessment [

22,

23,

24]. A key advantage of IOUS is its ability to provide dynamic intraoperative visualization, enabling surgeons to adjust their approach during surgery with greater accuracy [

23,

24,

25]. Compared with IOMRI and IOCT, IOUS provides remarkable practical benefits, including lower cost, ease of use, and wider accessibility, and also demonstrates effectiveness in identifying specific tumor characteristics [

23,

26,

27,

28]. Due to these advantages, IOUS has been successfully implemented in both adult and pediatric populations as a supplementary imaging tool to improve the delineation of tumor margin and the extent of resection [

23,

24,

27,

29,

30].

The present study, in addition to our previous research conducted using SF [

31], aims to further explore the effectiveness of IOUS, in addition to SF, in evaluating the completeness of tumor resection and the impact of using SF alone versus SF combined with IOUS on surgical resection and patient survival. Based on existing research, we anticipate that IOUS, when used along with SF, will significantly contribute to real-time surgical decision-making, enable more precise tumor resection, and improve clinical outcomes in neurosurgical patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics and Data Collection

This retrospective study evaluated adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with supratentorial IDH-wildtype grade 4 glioblastoma, through histopathological examination, who underwent surgical resection during 2015–2024 at the Neurosurgery Department of Kocaeli University Faculty of Medicine and the Neurosurgery Department of Derince State Hospital, Turkey. Demographic, clinical, radiological, and surgical data were retrospectively collected for these patients. The collected variables included patient age at the time of surgery, date of operation, preoperative and intraoperative imaging findings (SF, SF with IOUS, and MRI), tumor location, operative records, and postoperative imaging assessments. The presence of residual tumor was determined using intraoperative findings and postoperative MRI, as evaluated by an experienced neuroradiologist. Follow-up physician records and MRI scans conducted within 3 months postsurgery were also reviewed.

Patients included in the study underwent surgery using either SF alone or a combination of SF and IOUS for intraoperative tumor visualization. GTR was preoperatively defined as the complete removal of all T1-weighted contrast-enhancing tumor tissues on MRI. Surgical interventions were performed by two experienced neurosurgeons.

The exclusion criteria included incomplete medical records, procedures limited to intracranial biopsy or planned subtotal tumor debulking, and tumors located in deep eloquent structures such as the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem. These locations were excluded because of the inherent difficulty in achieving GTR and preserving neurological function.

2.2. Surgical Procedure

Patients were categorized into two groups based on the intraoperative imaging techniques used; one group underwent resection with SF alone, and the other group underwent a combination of SF and IOUS. Patients were excluded if they did not receive one of these two imaging approaches or if available data were insufficient to confirm intraoperative imaging use. Throughout all procedures, efforts were made to preserve eloquent brain structures and minimize neurological deficits. Whenever feasible, GTR was pursued. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring, including motor and somatosensory assessments, was used along with neuronavigation systems.

Preoperative MRI with and without contrast was conducted for all patients to assist in surgical planning. In the operating room, patients were positioned in a Mayfield head holder for stabilization and optimal surgical access. Neuronavigation was used in both groups for intraoperative guidance.

In the SF group, a 5 mg/kg intravenous dose of SF was administered after anesthesia induction, according to established protocols [

32]. Fluorescence-guided resection was performed using a surgical microscope equipped with xenon white light illumination. Initial fluorescence was observed throughout the brain parenchyma; however, over time, it remained concentrated in areas with blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption. Resection was guided by fluorescence-stained tissue, indicating tumor regions that required removal. Resection was continued until no fluorescence remained, suggesting the transition to normal brain parenchyma. Tumors were primarily excised en bloc, although piecemeal removal using an ultrasonic aspirator was utilized in some cases (

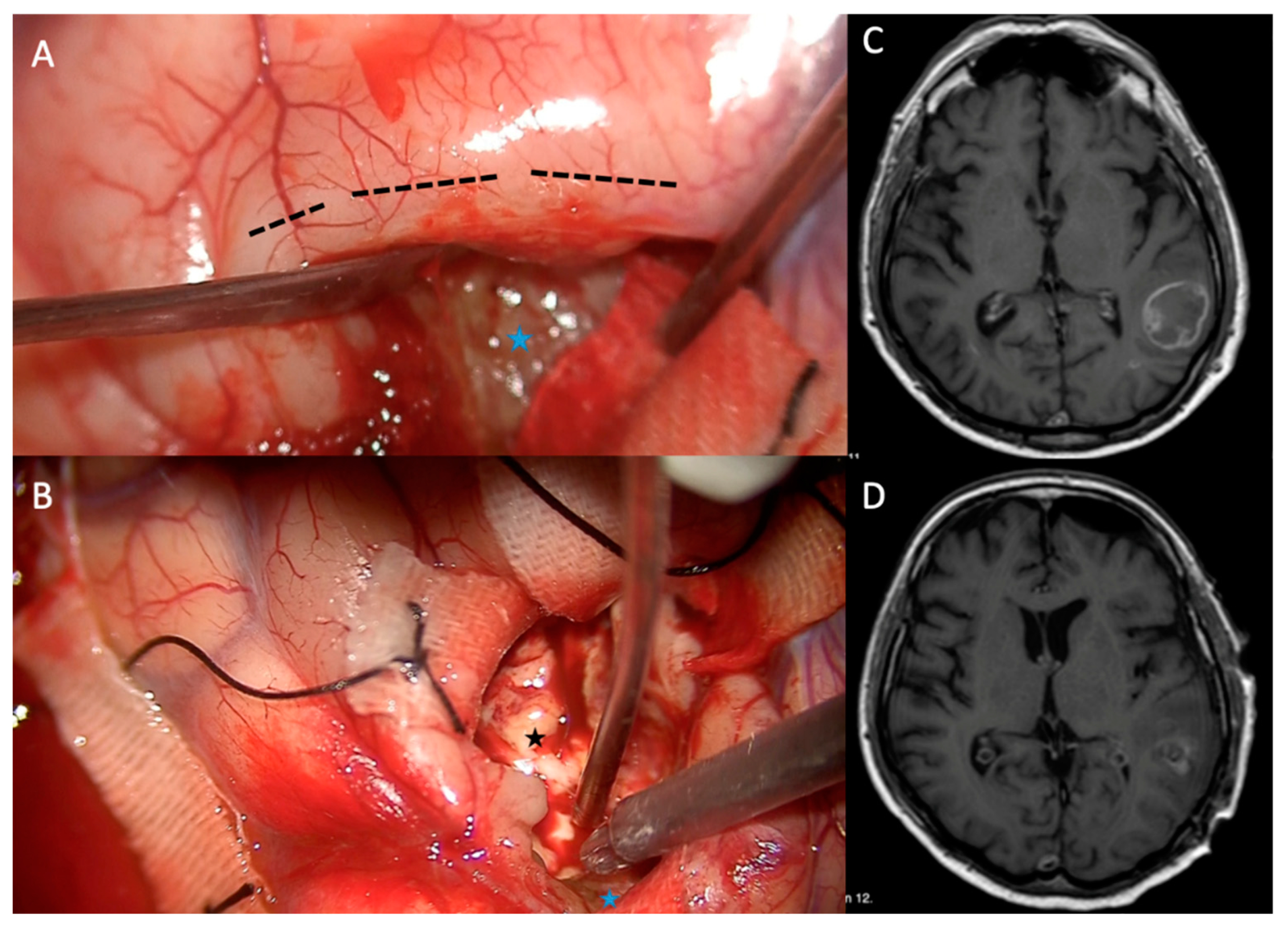

Figure 1).

In the SF with IOUS group, SF was administered as described earlier, and IOUS was used concurrently to examine the tumor cavity for residual tissue. A standard two-dimensional ultrasound probe (LOGIQ Ultrasound, GE Healthcare) was used at various stages to optimize resection. In both groups, a surgical microscope with xenon white light illumination was used, without additional filters or modifications.

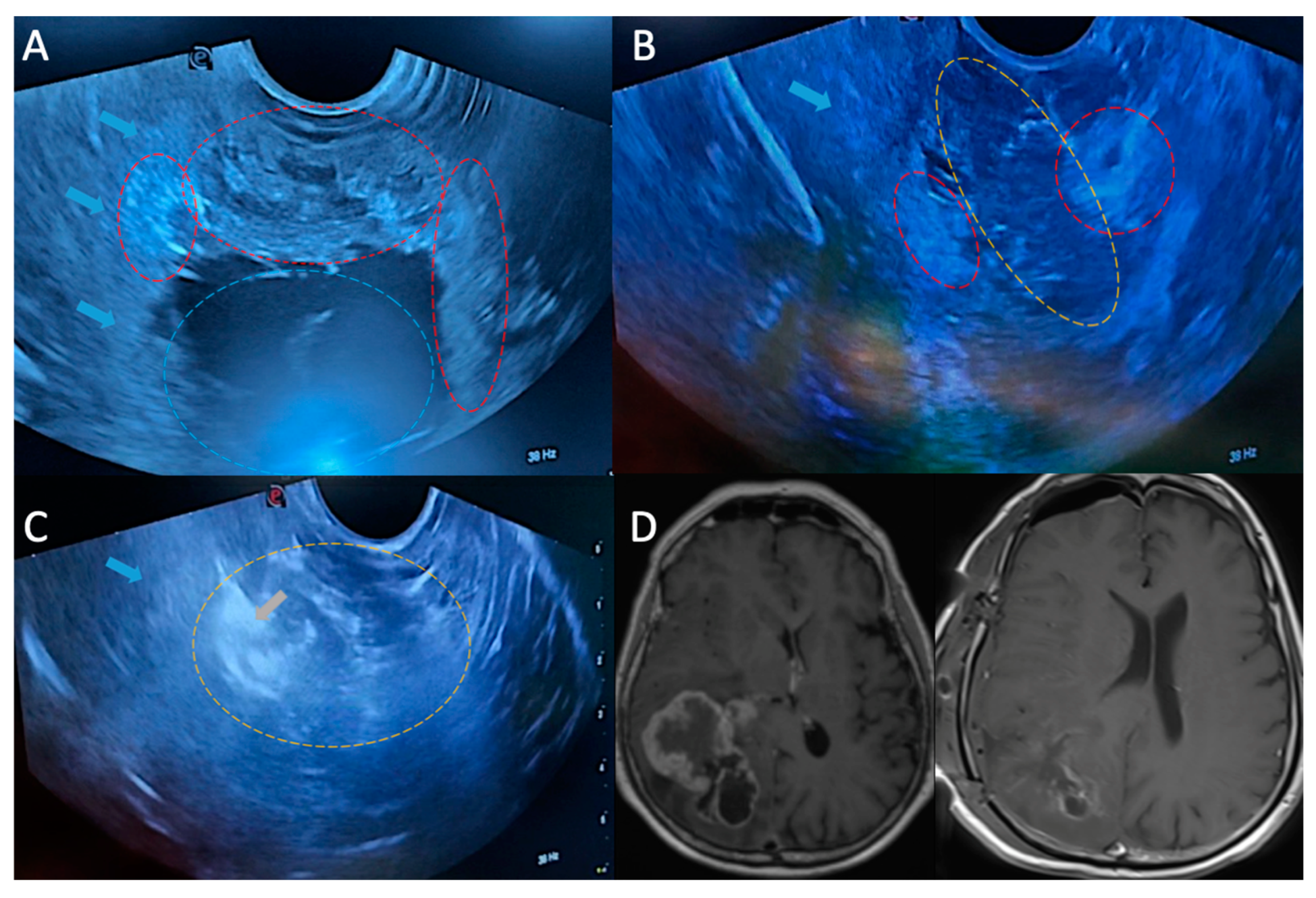

A craniotomy was performed to expose the dura, and sterile saline irrigation was applied to the surgical field to improve ultrasound transmission. Neuronavigation and IOUS were performed to confirm tumor localization and delineate margins. IOUS was periodically performed throughout the resection to evaluate progress. When the tumor was believed to be completely resected, a final IOUS scan was performed. If a residual tumor was detected in an area considered safe for further resection, additional excision was attempted. However, if the tumor was located in an eloquent region where further resection posed a high risk of neurological compromise, intentional subtotal resection was performed to preserve function. The IOUS findings were interpreted in real-time by the attending neurosurgeon to guide intraoperative decision-making (

Figure 2).

At the completion of resection, the primary intraoperative imaging modality—either SF alone or SF with IOUS—was used to examine the resection cavity for residual tumor. Postoperative MRI was considered the gold standard for confirming residual contrast-enhancing tissue. If residual tumor was detected on intraoperative imaging and further resection was deemed safe, additional excision was performed until GTR was achieved or further removal was considered high risk due to proximity to critical neurovascular structures.

2.3. Surgical Outcomes

The primary outcome measures included the extent of tumor resection, presence of residual tumor on postoperative imaging, achievement of GTR, accuracy of intraoperative imaging in detecting residual tumor, and the incidence of new postoperative neurological deficits. The extent of resection was quantified as the percentage reduction in tumor volume between preoperative and postoperative MRI scans. Residual tumor was defined as any contrast-enhancing lesion detected on postoperative MRI, as evaluated by an attending neuroradiologist. GTR was defined as the complete removal of the contrast-enhancing tumor tissue, confirmed on T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium contrast.

False-negative intraoperative assessments were identified in cases where intraoperative imaging indicated complete resection, but postoperative MRI revealed residual tumor. The development of new neurological deficits was evaluated during the initial follow-up visit, approximately 2 weeks postsurgery. Any new or worsening deficits were considered indicators of possible overresection based on intraoperative imaging guidance.

2.4. Radiographic Assessment and Follow-Up

Preoperative and postoperative MRI scans were evaluated to establish baseline tumor size and determine the extent of resection. T1-weighted contrast-enhanced sequences were used for evaluating imaging findings, with only the surgically treated lesion considered in cases with multiple contrast-enhancing foci. An experienced neuroradiologist, blinded to patient outcomes, reviewed all the imaging findings.

Routine follow-up MRI examinations were conducted at regular intervals, with shorter intervals applied in cases where findings were ambiguous or where disease progression was suspected.

2.5. Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy

At the end of surgery, SF or SF with IOUS was used to evaluate the resection cavity for any remaining tumor. Findings were compared against postoperative gadolinium-enhanced MRI, which served as the reference standard for detecting residual tumor. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for both SF alone and SF with IOUS groups to evaluate their intraoperative diagnostic accuracy.

2.6. Survival and Functional Outcomes

OS was defined as the time from primary tumor resection to death. PFS was determined as the interval from the initial resection to malignant progression, confirmed by either histopathological findings from reoperation or new contrast-enhancing lesions on follow-up MRI.

Functional status was evaluated using the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale, which was recorded both preoperatively and 1 month postoperatively. The KPS scale score ranges from 100 (normal function) to 10 (moribund state), with higher scores indicating better survival and quality of life.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were conducted to evaluate the normality assumption. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were conducted using the independent samples t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for nonnormally distributed variables. Associations between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. The Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test was used for survival analysis. Agreement analysis was conducted using Kappa’s statistic. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 97 patients (49 in the SF group and 48 in the SF with IOUS group) who were treated for IDH-wildtype grade 4 glioblastoma.

The male/female proportion of patients in the SF group was 22/27, and that in the SF with IOUS group was 30/18 (SF: 44.9%; IOUS: 62.5%; p = 0.125). The mean age of patients was 53.04 ± 8.21 years in the SF group and 57.29 ± 9.74 years in the SF with IOUS group (p = 0.022).

3.2. Clinical Presentation

The preoperative clinical features are also summarized in

Table 1. Comorbidities were detected in 17 patients (34.7%) in the SF group and 22 patients (45.8%) in the SF with IOUS group (p = 0.362). Recurrent tumors were more frequent in the SF with IOUS group than in the SF group. A total of 36 patients (73.5%) in the SF group and 34 patients (70.8%) in the SF with IOUS group had no previous history of operation (p = 0.950) (The remaining 13 (26.5%) vs 14 (29.2%) patients had undergone previous surgical procedures). The most common presenting symptoms in both groups were headache in 51/97 (52.6%) patients, seizure in 31/97 (32%) patients, paresis in 21/97 (21.6%) patients, speech impairment in 14/97 (14.4%) patients, cognitive changes in 11/97 (11.3%) patients, and visual disturbances in 4/93 (4.1%) patients.

In the SF group, 23/49 (46.9%) patients, 22/49 (44.9%) patients, and 4/49 (8.2%) patients had a preoperative KPS score of 90–100, 70–80, and <70, respectively. In the SF with IOUS group, 20/48 (41.7%) patients, 22/48 (45.8%) patients, and 6/48 (12.5%) patients had a preoperative KPS score of 90–100, 70–80, and <70, respectively (p = 0.733).

3.3. Preoperative Neuroimaging Findings and Tumor Features

The tumor characteristics and neuroimaging findings are shown in

Table 1. The most common tumor localizations were left frontal (11/49), left temporal (7/49), and left parietal (6/49) in the SF group and left frontal (8/48), left parietal (8/48), and right temporal (8/48) in the SF with IOUS group. Preoperative MRI measurements revealed a mean ± standard deviation (range) maximal diameter of the tumor of 46.94 ± 9.44 (29–68) mm in the SF group and 46.15 ± 8.98 (32–64) mm in the SF with IOUS group (p = 0.605).

3.4. Surgical Evaluation and Tumor Resection Outcomes

Table 2 shows the outcomes of patients’ surgical evaluation and tumor resection.

In total, 33/49 (67.3%) patients in the SF group and 40/48 (83.3%) patients in the SF with IOUS group had a negative result (GTR) for residual tumor according to postoperative MRI. The GTR rate was higher in the SF with IOUS group (83.3%) than in the SF group (67.3%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.112).

A total of 6/49 (12.2%) patients in the SF group (ϰ: 0.447, p = 0.001) and 4/48 (8.3%) patients in the SF with IOUS group (ϰ: 0.625, p < 0.001) had a positive result for residual tumor according to both preoperative techniques and postoperative MRI as a result of subtotal resection (STR) due to tumor invasion of eloquent anatomical locations. For detecting residual tumor, the agreement analysis was moderate in the SF group but substantial in the SF with IOUS group, according to Kappa’s statistic.

Residual tumor could be correctly identified using SF in 6/16 (37.5%) STR cases, whereas using SF with IOUS, it could be correctly identified in 4/8 (50%) STR cases, according to postoperative MRI.

Among patients with recurrent tumors, 5/13 in the SF group and 2/14 in the SF with IOUS group had false-negative results. All patients with recurrent tumors had undergone surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy previously.

3.5. Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy

Table 3 shows the sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV for predicting residual tumor preoperatively compared with postoperative MRI results in the SF and SF with IOUS groups. The respective values were 37.5% (95% CI 18.5%–61.4%), 100% (95% CI 89.6%–100%), 76.7% (95% CI 62.1%–87.1%), and 100 % (95% CI 90.9%–99.8%) in the SF group and 50% (95% CI 21.5%–78.5%), 100% (95% CI 91.2%–100%), 90.9% (95% CI 78.2%–96.9%), and 100% (95% CI 90.8%–99.8%) in the SF with IOUS group.

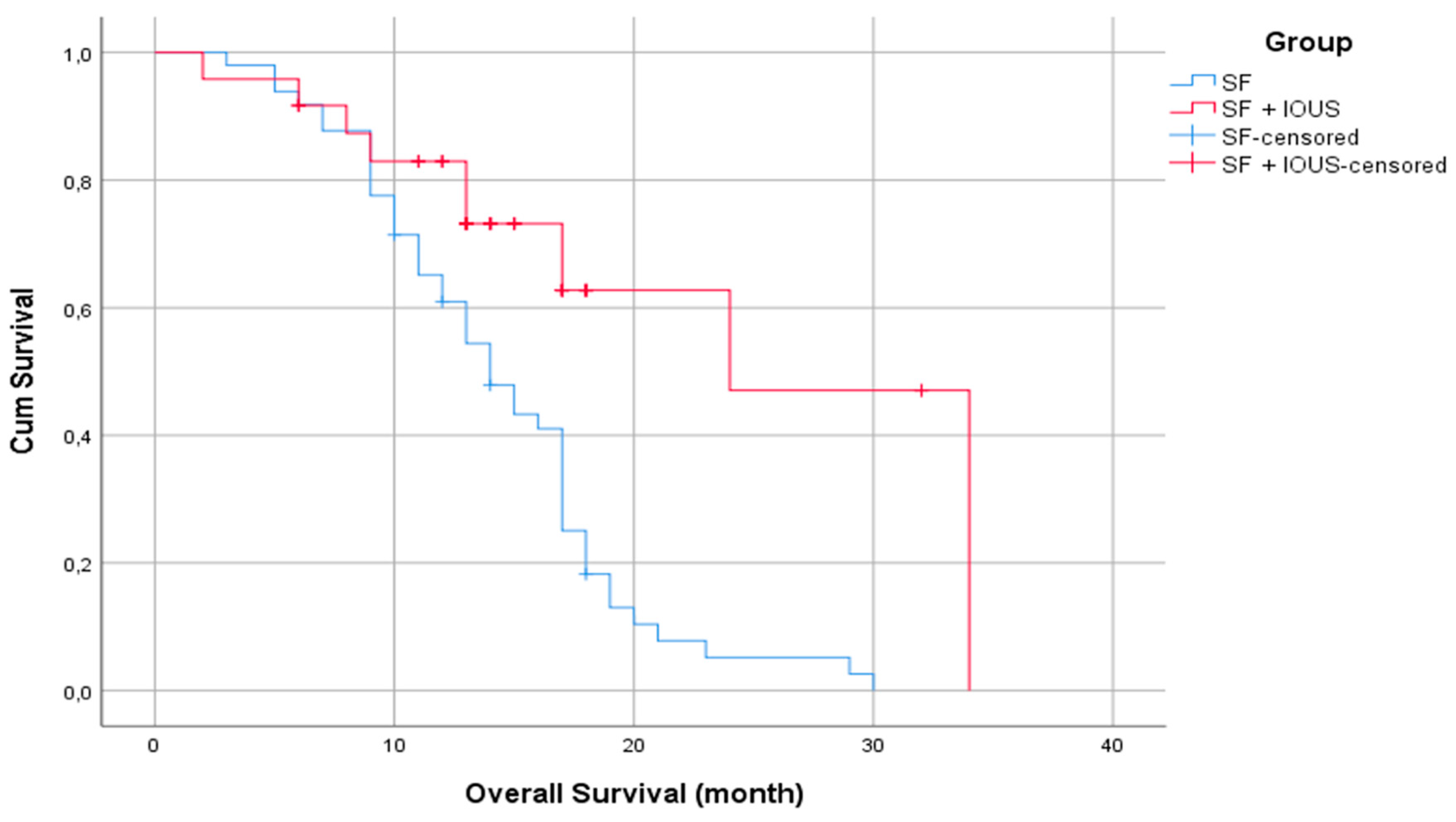

3.6. Survival Outcomes

For the entire population, the estimated 1-year OS rate was 71.6%, and the estimated 2-year OS rate decreased to 15%. The estimated mean survival time after surgery for the entire population was 17 months (standard error: 0.686). A statistically significant difference was found in the estimated mean survival time when the SF and SF with IOUS groups were compared, with 14 months (standard error: 1.236) for the SF group and 24 months (standard error: 4.103) for the SF with IOUS group (p < 0.001) (

Figure 3).

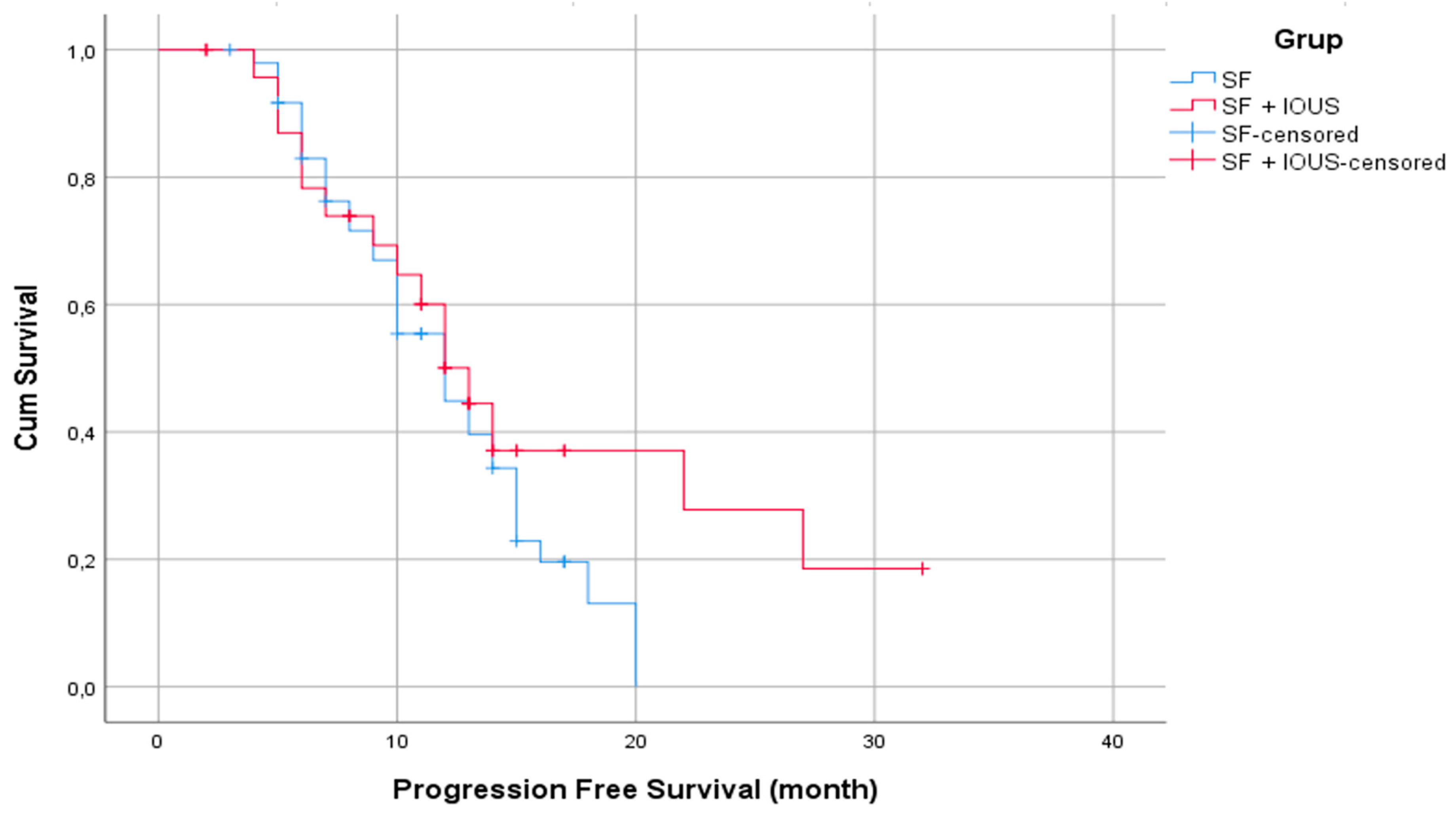

The 1-year PFS rate for the entire population was 47.5%, with a mean estimated PFS of 12 months (standard error: 0.690). However, there was no statistically significant difference in PFS durations between the two groups, with a mean PFS of 12 months (standard error: 1.456) for the SF group and 13 months (0.992) for the SF with IOUS group (p = 0.182) (

Figure 4).

3.7. Postoperative New Neurological Deficits and KPS Scores

Table 4 presents the newly developed postoperative neurological deficits and KPS scores.

Newly developed neurological deficits postoperatively were identified in 11/49 (22.4%) patients in the SF group (1 motor and 1 cognitive deficits were permanent) and 10/48 (20.8%) patients in the SF with IOUS group (1 motor deficit was permanent) (p = 1.000).

In the SF group, 21/49 (42.9%) patients, 19/49 (38.8%) patients, and 9/49 (18.4%) patients had a postoperative KPS score of 90–100, 70–80, and <70, respectively. In total, 14/49 patients experienced deterioration, 26/49 patients were stable, and 9/49 patients had improved at 1 month.

In the SF with IOUS group, 26/48 (54.2%) patients, 14/48 (29.2%) patients, and 8/48 (16.7%) patients had a postoperative KPS score of 90–100, 70–80, and <70, respectively (p = 0.525). A total of 12 patients experienced deterioration, 24 patients were stable, and 12 patients had improved at 1 month.

4. Discussion

This study emphasizes the advantages of using SF in combination with IOUS compared with SF alone for glioblastoma resection. Although the SF with IOUS group achieved a higher GTR rate (83.3%) than the SF alone group (67.3%), the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.112). Nevertheless, SF with IOUS demonstrated improved accuracy in identifying residual tumor tissue intraoperatively, as indicated by its stronger agreement with postoperative MRI findings (ϰ: 0.625 vs. 0.447) and NPV of 90.9%. Furthermore, the survival analysis revealed a significant benefit, with the SF with IOUS group showing a longer estimated mean survival (24 months) than the SF group (14 months) (p < 0.001). Postoperative neurological deficits were observed at comparable rates in both groups (22.4% vs. 20.8%, p > 0.05), suggesting that incorporating IOUS does not increase the risk of adverse effects.

Fluorescein-guided surgery is widely used because of its affordability and high intraoperative staining rates of >90% [

33,

34,

35]. However, its dependence on BBB disruption may reduce its specificity in distinguishing tumor tissue [

36,

37]. A primary challenge with SF use is that fluorescence can spread into surrounding areas over time, making it harder to delineate tumor margins accurately [

38]. Conversely, IOUS provides real-time imaging that is independent of BBB integrity, providing detailed insights into tumor depth and its relation to vital neurovascular structures [

39]. This makes IOUS a valuable addition to intraoperative imaging, applicable across various tumor types.

The increasing adoption of IOUS in neurosurgery is particularly beneficial when tumor boundaries are unclear. Unlike fluorescence-based techniques, IOUS allows for continuous intraoperative evaluation of the residual tumor, providing immediate feedback on resection progress [

27]. This is particularly advantageous when en bloc resection is not possible, because IOUS facilitates piecemeal removal and ensures maximal safe resection. Previous research has demonstrated that the performance of IOUS is comparable to that of intraoperative MRI in detecting residual tumor in pediatric brain tumors, further supporting its use in surgical planning [

39]. Moreover, another advantage of IOUS is that, compared with IOMRI and IOCT, it can be easily used in several centers due to its lower cost, ease of use, and broader accessibility.

Despite its benefits, IOUS has certain drawbacks. Image quality may be affected by artifacts caused by surgical debris, blood accumulation, and tissue distortion, potentially causing misinterpretation [

40]. Techniques such as using smaller phased array probes and alternative ultrasound-compatible fluids with acoustic properties more similar to those of brain tissue have been proposed to improve image resolution [

41]. Furthermore, IOUS is highly dependent on the operator’s experience and skill level, requiring adequate training to optimize its application. Although some institutions involve radiologists for intraoperative interpretation, in several settings, including ours, the evaluation is solely conducted by the operating neurosurgeon. Expanding IOUS training in neurosurgical education may improve its effectiveness and broader clinical application.

Accurately defining tumor margins intraoperatively is vital for maximizing safe resection, which is a major determinant of survival in patients with glioblastoma [

42]. Various intraoperative imaging techniques, including neuronavigation, intraoperative MRI, and fluorescence-guided surgery, have been introduced to improve surgical outcomes. Although 5-ALA has been demonstrated to provide high tumor specificity, SF remains a more cost-effective option, despite its lower specificity [

31]. Remarkably, previous studies suggest that SF does not significantly influence median survival, emphasizing its role as a surgical aid rather than a determinant of long-term prognosis [

31].

This study has some limitations. Computerized volumetric analysis was not performed, which could have provided a more precise quantification of tumor resection. The determination of residual tumor solely relied on contrast enhancement in postoperative MRI, without intraoperative histopathological confirmation. Furthermore, SF and IOUS interpretation was subjective and depended on the surgeon’s expertise. The retrospective nature of the study and the relatively small patient cohort introduce a potential selection bias, which may limit the generalizability of the findings.

5. Conclusions

Combining SF with IOUS may improve intraoperative tumor visualization and resection accuracy without increasing postoperative complications. Although SF facilitates rapid tumor identification based on BBB disruption, IOUS provides real-time depth evaluation and continuous monitoring throughout the surgical procedure. This complementary approach optimizes surgical decision-making and may result in better resection outcomes in patients with glioblastoma. Future studies should aim at refining imaging protocols, minimizing artifacts, and further validating the effectiveness of SF and IOUS in improving GTR rates. As intraoperative imaging continues to evolve, integrating multiple modalities may become a standard practice in neurosurgical oncology to improve patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Aykut Gokbel, Savas Ceylan. Methodology Ayse Uzuner, Aykut Gokbel; software, Ayse Uzuner, Sibel Balci validation, Aykut Gokbel, Atakan Emengen..; formal analysis, Eren Yilmaz, Ihsan Anik.; data curation, Aykut Gokbel, Ayse Uzuner; writing—original draft preparation, Aykut Gokbel, , Savas Ceylan ; writing—review and editing, Aykut Gokbel, Ayse Uzuner, Savas Ceylan ; visualization, Aykut Gokbel ; supervision Savas Ceylan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the approval provided by the relevant ethics committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

IOUS intraoperative ultrasonography

SF sodium fluorescein

GTR gross total resection

IDH-1 isocitrate dehydrogenase-1

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

IOMRI intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging

IOCT intraoperative computed tomography

5-ALA 5-aminolevulinic acid

HGGs high-grade gliomas

PFS progression-free survival

OS overall survival

BBB blood–brain barrier

PPV positive predictive value

NPV negative predictive value

KPS Karnofsky Performance Status

IQR interquartile range

CI confidence interval

References

- Sweeney JF, Rosoklija G, Sheldon BL, Bondoc M, Bandlamuri S, Adamo MA. Comparison of sodium fluorescein and intraoperative ultrasonography in brain tumor resection. J Clin Neurosci. 2022 Dec;106:141-144. Epub 2022 Oct 27. PMID: 36327792. [CrossRef]

- Bayer S, Maier A, Ostermeier M, Fahrig R. Intraoperative Imaging Modalities and Compensation for Brain Shift in Tumor Resection Surgery. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2017;2017:6028645. Epub 2017 Jun 5. Erratum in: Int J Biomed Imaging. 2019 Oct 1;2019:9249016. PMID: 28676821; PMCID: PMC5476838.https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9249016. [CrossRef]

- Belykh E, Martirosyan NL, Yagmurlu K, Miller EJ, Eschbacher JM, Izadyyazdanabadi M, Bardonova LA, Byvaltsev VA, Nakaji P, Preul MC. Intraoperative Fluorescence Imaging for Personalized Brain Tumor Resection: Current State and Future Directions. Front Surg. 2016 Oct 17;3:55. PMID: 27800481; PMCID: PMC5066076. [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson MD, Barone DG, Bryant A, Vale L, Bulbeck H, Lawrie TA, Hart MG, Watts C. Intraoperative imaging technology to maximise extent of resection for glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jan 22;1(1):CD012788. PMID: 29355914; PMCID: PMC6491323. [CrossRef]

- Karschnia P, Vogelbaum MA, van den Bent M, Cahill DP, Bello L, Narita Y, Berger MS, Weller M, Tonn JC. Evidence-based recommendations on categories for extent of resection in diffuse glioma. Eur J Cancer. 2021 May;149:23-33. Epub 2021 Apr 2. PMID: 33819718. [CrossRef]

- D'Amico RS, Englander ZK, Canoll P, Bruce JN. Extent of Resection in Glioma-A Review of the Cutting Edge. World Neurosurg. 2017 Jul;103:538-549. Epub 2017 Apr 17. PMID: 28427971. [CrossRef]

- Wykes V, Zisakis A, Irimia M, Ughratdar I, Sawlani V, Watts C. Importance and Evidence of Extent of Resection in Glioblastoma. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2021 Jan;82(1):75-86. Epub 2020 Oct 13. PMID: 33049795. [CrossRef]

- Cahill DP. Extent of Resection of Glioblastoma: A Critical Evaluation in the Molecular Era. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2021 Jan;32(1):23-29. Epub 2020 Nov 5. PMID: 33223023; PMCID: PMC7742372. [CrossRef]

- Ng PR, Choi BD, Aghi MK, Nahed BV. Surgical advances in the management of brain metastases. Neurooncol Adv Nov 2021;3(Suppl 5):v4–15. [CrossRef]

- Rivera M, Norman S, Sehgal R, Juthani R. Updates on Surgical Management and Advances for Brain Tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021 Feb 25;23(3):35. PMID: 33630180. [CrossRef]

- Eatz TA, Eichberg DG, Lu VM, Di L, Komotar RJ, Ivan ME. Intraoperative 5-ALA fluorescence-guided resection of high-grade glioma leads to greater extent of resection with better outcomes: a systematic review. J Neurooncol. 2022 Jan;156(2):233-256. Epub 2022 Jan 6. PMID: 34989964. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo C, De Laurentis C, Vetrano IG, Falco J, Broggi M, Schiariti M, Ferroli P, Acerbi F. The utilization of fluorescein in brain tumor surgery: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Sci. 2018 Dec;62(6):690-703. Epub 2018 May 22. PMID: 29790725. [CrossRef]

- Noh T, Mustroph M, Golby AJ. Intraoperative Imaging for High-Grade Glioma Surgery. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2021 Jan;32(1):47-54. Epub 2020 Nov 5. PMID: 33223025; PMCID: PMC7813557. [CrossRef]

- Dixon L, Lim A, Grech-Sollars M, Nandi D, Camp S. Intraoperative ultrasound in brain tumor surgery: A review and implementation guide. Neurosurg Rev. 2022 Aug;45(4):2503-2515. Epub 2022 Mar 30. PMID: 35353266; PMCID: PMC9349149. [CrossRef]

- Wei R, Chen H, Cai Y, Chen J. Application of intraoperative ultrasound in the resection of high-grade gliomas. Front Neurol. 2023 Oct 26;14:1240150. PMID: 37965171; PMCID: PMC10640994. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG, Deltour I, Fisher JL, Langer CE, Pekmezci M, Schwartzbaum JA, Turner MC, Walsh KM, Wrensch MR, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a "state of the science" review. Neuro Oncol. 2014 Jul;16(7):896-913. PMID: 24842956; PMCID: PMC4057143. [CrossRef]

- Stupp R, Brada M, van den Bent MJ, Tonn JC, Pentheroudakis G; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. High-grade glioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014 Sep;25 Suppl 3:iii93-101. Epub 2014 Apr 29. PMID: 24782454. [CrossRef]

- Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M, Le Rhun E, Tonn JC, Minniti G, Bendszus M, Balana C, Chinot O, Dirven L, French P, Hegi ME, Jakola AS, Platten M, Roth P, Rudà R, Short S, Smits M, Taphoorn MJB, von Deimling A, Westphal M, Soffietti R, Reifenberger G, Wick W. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021 Mar;18(3):170-186. Epub 2020 Dec 8. Erratum in: Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022 May;19(5):357-358. PMID: 33293629; PMCID: PMC7904519.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00623-3. [CrossRef]

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM, Reifenberger G, Soffietti R, von Deimling A, Ellison DW. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021 Aug 2;23(8):1231-1251. PMID: 34185076; PMCID: PMC8328013. [CrossRef]

- Brown TJ, Brennan MC, Li M, Church EW, Brandmeir NJ, Rakszawski KL, Patel AS, Rizk EB, Suki D, Sawaya R, Glantz M. Association of the Extent of Resection With Survival in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016 Nov 1;2(11):1460-1469. PMID: 27310651; PMCID: PMC6438173. [CrossRef]

- Ma R, Taphoorn MJB, Plaha P. Advances in the management of glioblastoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;92(10):1103-1111. Epub 2021 Jun 23. PMID: 34162730. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney JF, Smith H, Taplin A, Perloff E, Adamo MA. Efficacy of intraoperative ultrasonography in neurosurgical tumor resection. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018 May;21(5):504-510. Epub 2018 Feb 16. PMID: 29451454. [CrossRef]

- Chacko AG, Kumar NK, Chacko G, Athyal R, Rajshekhar V. Intraoperative ultrasound in determining the extent of resection of parenchymal brain tumours--a comparative study with computed tomography and histopathology. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003 Sep;145(9):743-8; discussion 748. PMID: 14505099. [CrossRef]

- Mair R, Heald J, Poeata I, Ivanov M. A practical grading system of ultrasonographic visibility for intracerebral lesions. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013 Dec;155(12):2293-8. Epub 2013 Sep 13. PMID: 24026229. [CrossRef]

- Roth J, Biyani N, Beni-Adani L, Constantini S. Real-time neuronavigation with high-quality 3D ultrasound SonoWand in pediatric neurosurgery. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43(3):185-91. PMID: 17409787. [CrossRef]

- Auer LM, van Velthoven V. Intraoperative ultrasound (US) imaging. Comparison of pathomorphological findings in US and CT. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1990;104(3-4):84-95. PMID: 2251948. [CrossRef]

- Hammoud MA, Ligon BL, elSouki R, Shi WM, Schomer DF, Sawaya R. Use of intraoperative ultrasound for localizing tumors and determining the extent of resection: a comparative study with magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 1996 May;84(5):737-41. PMID: 8622145. [CrossRef]

- Petridis AK, Anokhin M, Vavruska J, Mahvash M, Scholz M. The value of intraoperative sonography in low grade glioma surgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015 Apr;131:64-8. Epub 2015 Feb 11. PMID: 25704192. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich NH, Burkhardt JK, Serra C, Bernays RL, Bozinov O. Resection of pediatric intracerebral tumors with the aid of intraoperative real-time 3-D ultrasound. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012 Jan;28(1):101-9. Epub 2011 Sep 17. PMID: 21927834. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Liu X, Ba YM, Yang YL, Gao GD, Wang L, Duan YY. Effect of sonographically guided cerebral glioma surgery on survival time. J Ultrasound Med. 2012 May;31(5):757-62. PMID: 22535723. [CrossRef]

- Koc K, Anik I, Cabuk B, Ceylan S. Fluorescein sodium-guided surgery in glioblastoma multiforme: a prospective evaluation. Br J Neurosurg. 2008 Feb;22(1):99-103. PMID: 18224529. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek M, Kulesza B, Stoma F, Osuchowski J, Mańdziuk S, Rola R. Characteristics of Fluorescent Intraoperative Dyes Helpful in Gross Total Resection of High-Grade Gliomas-A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Dec 16;10(12):1100. PMID: 33339439; PMCID: PMC7766001. [CrossRef]

- Di Cristofori A, Carone G, Rocca A, Rui CB, Trezza A, Carrabba G, Giussani C. Fluorescence and Intraoperative Ultrasound as Surgical Adjuncts for Brain Metastases Resection: What Do We Know? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Mar 29;15(7):2047. PMID: 37046709; PMCID: PMC10092992. [CrossRef]

- Höhne J, Hohenberger C, Proescholdt M, Riemenschneider MJ, Wendl C, Brawanski A, Schebesch KM. Fluorescein sodium-guided resection of cerebral metastases-an update. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017 Feb;159(2):363-367. Epub 2016 Dec 23. PMID: 28012127. [CrossRef]

- Schebesch KM, Proescholdt M, Höhne J, Hohenberger C, Hansen E, Riemenschneider MJ, Ullrich W, Doenitz C, Schlaier J, Lange M, Brawanski A. Sodium fluorescein-guided resection under the YELLOW 560 nm surgical microscope filter in malignant brain tumor surgery--a feasibility study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013 Apr;155(4):693-9. h Epub 2013 Feb 21. PMID: 23430234.ttps://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-013-1643-y.

- Marbacher S, Klinger E, Schwyzer L, Fischer I, Nevzati E, Diepers M, Roelcke U, Fathi AR, Coluccia D, Fandino J. Use of fluorescence to guide resection or biopsy of primary brain tumors and brain metastases. Neurosurg Focus. 2014 Feb;36(2):E10. PMID: 24484248. [CrossRef]

- Balana C, Castañer S, Carrato C, Moran T, Lopez-Paradís A, Domenech M, Hernandez A, Puig J. Preoperative Diagnosis and Molecular Characterization of Gliomas With Liquid Biopsy and Radiogenomics. Front Neurol. 2022 May 26;13:865171. PMID: 35693015; PMCID: PMC9177999. [CrossRef]

- Bianco A, Del Maestro M, Fanti A, Airoldi C, Fleetwood T, Crobeddu E, Cossandi C. Use of fluorescein sodium-assisted intraoperative sample validation to maximize the diagnostic yield of stereotactic brain biopsy: progress toward a new standard of care? J Neurosurg. 2022 Jun 3;138(2):358-366. PMID: 36303472. [CrossRef]

- Giussani C, Trezza A, Ricciuti V, Di Cristofori A, Held A, Isella V, Massimino M. Intraoperative MRI versus intraoperative ultrasound in pediatric brain tumor surgery: is expensive better than cheap? A review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2022 Aug;38(8):1445-1454. Epub 2022 May 5. PMID: 35511271. [CrossRef]

- Moiyadi AV. Intraoperative Ultrasound Technology in Neuro-Oncology Practice-Current Role and Future Applications. World Neurosurg. 2016 Sep;93:81-93. Epub 2016 Jun 4. PMID: 27268318. [CrossRef]

- Selbekk T, Jakola AS, Solheim O, Johansen TF, Lindseth F, Reinertsen I, Unsgård G. Ultrasound imaging in neurosurgery: approaches to minimize surgically induced image artefacts for improved resection control. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013 Jun;155(6):973-80. Epub 2013 Mar 5. PMID: 23459867; PMCID: PMC3656245. [CrossRef]

- Litofsky NS, Bauer AM, Kasper RS, Sullivan CM, Dabbous OH; Glioma Outcomes Project Investigators. Image-guided resection of high-grade glioma: patient selection factors and outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 2006 Apr 15;20(4):E16. PMID: 16709021. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A. The tumor tissue stained with SF was reached after sulcal dissection. B. After tumor resection, the underlying edematous normal brain parenchyma was observed, and resection of the remaining tumor tissue stained with SF continued using an ultrasonic aspirator. C and D. Preoperative and postoperative contrast-enhanced MRI views. Black dashed line shows gyrus. Black asterisk shows edematous normal brain parenchyma after resection. Blue asterisk shows remaining tumor tissue stained with SF.

Figure 1.

A. The tumor tissue stained with SF was reached after sulcal dissection. B. After tumor resection, the underlying edematous normal brain parenchyma was observed, and resection of the remaining tumor tissue stained with SF continued using an ultrasonic aspirator. C and D. Preoperative and postoperative contrast-enhanced MRI views. Black dashed line shows gyrus. Black asterisk shows edematous normal brain parenchyma after resection. Blue asterisk shows remaining tumor tissue stained with SF.

Figure 2.

A. IOUS were performed to confirm tumor localization and delineate margins. Red dashed lines indicate the solid tumor portion, blue dashed line indicate the cystic part of the tumor. B. IOUS was performed throughout the resection to evaluate progress. In the IOUS, red dashed lines indicate the remaining solid tumor mass, yellow dashed line shows the resection cavity. C. Post-resection IOUS image. Yellow dashed line indicates the GTR surgical cavity, and gray arrow shows the hemostatic agents placed in the cavity. D. Preoperative and postoperative contrast-enhanced MRI views. Blue arrows show the edematous normal brain tissue surrounding the tumor.

Figure 2.

A. IOUS were performed to confirm tumor localization and delineate margins. Red dashed lines indicate the solid tumor portion, blue dashed line indicate the cystic part of the tumor. B. IOUS was performed throughout the resection to evaluate progress. In the IOUS, red dashed lines indicate the remaining solid tumor mass, yellow dashed line shows the resection cavity. C. Post-resection IOUS image. Yellow dashed line indicates the GTR surgical cavity, and gray arrow shows the hemostatic agents placed in the cavity. D. Preoperative and postoperative contrast-enhanced MRI views. Blue arrows show the edematous normal brain tissue surrounding the tumor.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for estimated mean survival time (months) between the SF and SF with IOUS groups.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for estimated mean survival time (months) between the SF and SF with IOUS groups.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS durations (months) between the SF and SF with IOUS groups.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS durations (months) between the SF and SF with IOUS groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics, clinical presentation and preoperative neuroimaging findings of patients. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (range), and qualitative variables are expressed as n (%). IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, NA: Not applicable.

Table 1.

Characteristics, clinical presentation and preoperative neuroimaging findings of patients. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (range), and qualitative variables are expressed as n (%). IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, NA: Not applicable.

| |

SF Group (n=49) |

SF with IOUS Group (n=48) |

pValue |

Sex

Male

Female |

22 (44.9%)

27 (55.1%) |

30 (62.5%)

18 (37.5%) |

0.125 |

| Age |

53.04 ± 8.21 (34-70) |

57.29 ± 9.74 (38-79) |

0.022 |

Comorbidities

Yes

No |

17 (34.7%)

32 (65.3%) |

22 (45.8%)

26 (54.2%) |

0.362 |

History of Operation

Yes

No |

13 (26.5%)

36 (73.5%) |

14 (29.2%)

34 (70.8%) |

0.950 |

Presenting Symptom

Headache (n=51)

Seizure (n=31)

Paresis (n=21)

Speech Impairment (n=14)

Cognitive Changes (n=11)

Visual Disturbances (n=4)

Incidental (n=3) |

21 (41.2%)

17 (54.8%)

11 (52.4%)

8 (57.1%)

6 (54.5%)

0

1 (33.3%) |

30 (58.8%)

14 (45.2%)

10 (47.6%)

6 (42.9%)

5 (45.5%)

4 (100%)

2 (66.6%) |

0.083

0.714

1.000

0.805

1.000

NA

NA |

Preoperative KPS Skore

90-100

70-80

<70 |

23 (46.9%)

22 (44.9%)

4 (8.2%) |

20 (41.7%)

22 (45.8%)

6 (12.5%) |

0.733 |

| Maximal Diameter of Tumor |

46.94 ± 9.44 (29-68) |

46.15 ± 8.98 (32-64) |

0.605 |

Table 2.

Patients surgical evaluation and tumor resection outcomes. Qualitative variables are expressed as n (%).(%). IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2.

Patients surgical evaluation and tumor resection outcomes. Qualitative variables are expressed as n (%).(%). IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

| |

SF Group (n=49) |

SF with IOUS Group (n=48) |

| |

No Residual Tumor |

Residual Tumor |

No Residual Tumor |

Residual Tumor |

Postoperative MRI

No Residual Tumor

Residual Tumor |

|

| 30 (61.2%) |

3 (6.1%) |

36 (75%) |

4 (8.3%) |

| 10 (20.4%) |

6 (12.2%) |

4 (8.3%) |

4 (8.3%) |

| |

Recurrent SF Group (n=13) |

Recurrent SF with IOUS Group (n=14) |

| |

No Residual Tumor |

Residual Tumor |

No Residual Tumor |

Residual Tumor |

Postoperative MRI

No Residual Tumor

Residual Tumor |

|

|

| 4 (30.8%) |

3 (23%) |

6 (42.8%) |

4 (28.6%) |

| 5 (38.5%) |

1 (7.7%) |

2 (14.3%) |

2 (14.3%) |

Table 3.

Comparison of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value between groups. IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, NPV: Negative predictive value, PPV: Positive predictive value, GTR: Gross total resection, CI: Confidence interval.

Table 3.

Comparison of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value between groups. IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, NPV: Negative predictive value, PPV: Positive predictive value, GTR: Gross total resection, CI: Confidence interval.

| |

SF Group (n=49) |

SF with IOUS Group (n=48) |

| Sensitivity |

0.375 (18.5%–61.4%) |

0.500 (21.5%–78.5%) |

| Specificity |

1.000 (89.6%–100%) |

1.000 (91.2%–100%) |

| NPV |

0.767 (62.1%–87.1%) |

0.909 (CI 78.2%–96.9%) |

| PPV |

1.000 (CI 90.9%–99.8%) |

1.000 (90.8%–99.8%) |

| GTR |

33 (67.3%) |

40 (83.3%) |

Table 4.

Postoperative newly developed neurological deficits and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of patients. Qualitative variables are expressed as n (%).. IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status.

Table 4.

Postoperative newly developed neurological deficits and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of patients. Qualitative variables are expressed as n (%).. IOUS: intraoperative ultrasonography, SF: sodium fluorescein, KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status.

| |

SF Group (n=49) |

SF with IOUS Group (n=48) |

p Value |

New Neurologic Deficits

Transient

Permanent |

9 (18.4%)

2 (4.1%) |

9 (18.7%)

1 (2.1%) |

1.000 |

Postoperative KPS Skore

90-100

70-80

<70 |

21(42.9%)

19 (38.8%)

9 (18.4%) |

26 (54.2%)

14 (29.2%)

8 (16.7%) |

0.525 |

Postoperative KPS Score

Improved

Stable

Deterioration |

9 (18.4%)

26 (53.1%)

14 (28.6%) |

12 (25%)

24 (50%)

12 (25%) |

0.745 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).