1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and aggressive primary malignant brain tumor in adults, characterized by rapid progression, invasiveness, and resistance to conventional therapies [

1]. The current standard of care, established by the 2005 EORTC/NCIC trial, combines maximal safe surgical resection with concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy [

2]. Despite intensive treatment, GBM patients face a poor prognosis, with a median survival of only 8 months post-diagnosis, irrespective of treatment [

1]. Over the past two decades, over 400 clinical trials have been conducted based on promising preclinical data [

3]. However, only two phase III trials – CeTeG/NO-09 (lomustine-temozolomide) [

4] and EF-14 (tumor treating fields) [

5] – reported significant survival benefit [

6], highlighting a gap between preclinical efficacy and clinical outcomes. A systematic review of phase I trials from 2006 to 2019 further illustrates this issue, showing that efficacy observed in preclinical models often fails to translate into meaningful clinical responses, likely due to the challenge of replicating human GBM complexity in animal models [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Conventional in vivo preclinical studies commonly use animal models harboring treatment-naïve tumors, thereby failing to replicate the clinical scenario where patients undergo tumor resection followed by radiation and chemotherapy to target residual disease [

8]. The therapeutic benefit of maximal safe resection on overall survival in GBM patients has been extensively documented [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Importantly, surgical intervention directly affects the recurrent disease by triggering processes such as increased cell migration, proliferation, angiogenesis, microglia infiltration, and upregulation of stem cell markers within recurrent tumors [

16,

17,

18]. Thus, replicating surgical procedures in preclinical models allows for assessing the efficacy of adjuvant therapies while accounting for subsequent alterations in the tumor microenvironment, including modifications in vascularization, immune response, and extracellular matrix remodeling. Therefore, integrating surgical interventions into preclinical models more effectively mirrors clinical reality compared to treatment-naïve models, thereby enhancing the potential for translating novel therapeutic approaches into clinical practice.

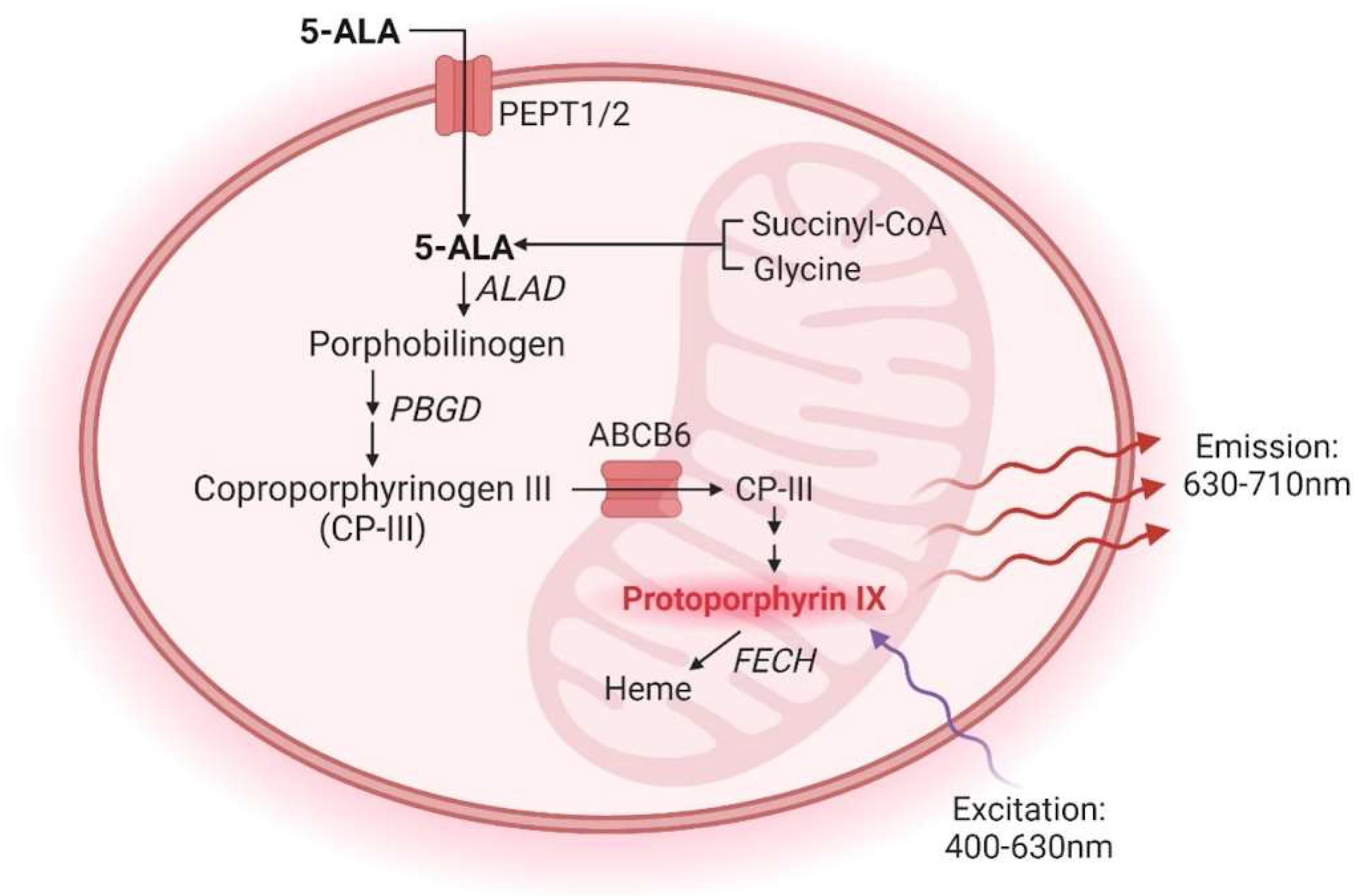

In clinical practice, using 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) during brain tumor surgery has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the extent of tumor resection and subsequently improve patient outcomes [

19]. After oral administration, 5-ALA is metabolized within GBM cells via the heme biosynthesis pathway, generating fluorescent protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). PpIX preferentially accumulates in cancer tissue due to variations in enzyme and transporter expression levels and regions of a leaky blood-brain barrier [

20,

21,

22,

23] (

Figure 1). Upon illumination with 400 nm light, PpIX emits fluorescence, which allows real-time intraoperative visualization and delineation of tumor tissue margins during surgery [

19]. Thus, fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) enables neurosurgeons to achieve maximal safe resection while sparing healthy brain tissue.

Current protocols for brain tumor resection in preclinical models, particularly those involving fluorescence-guided techniques, are scarce. Existing fluorescence-guided resection protocols rely on the use of cells labeled with fluorescent tags, such as mCherry, GFP, or RFP, which lack clinical translatability because human tumors are not inherently fluorescent [

17,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Furthermore, many of these techniques involve the implantation of tumors at shallow depths (0.5-1 mm), failing to replicate the invasive characteristics observed in human tumors. In studies demonstrating 5-ALA fluorescence in preclinical GBM models, 5-ALA imaging was used only for secondary validation of resection extent, as the tumors were resected using GFP-expressing tumor cells, or survival outcomes were not assessed [

25,

28,

29].

In the present study, we describe a protocol for the 5-ALA-guided resection of two mouse GBM models: TRP-mCherry-FLuc (TRP-mCF) and GL261 Red-FLuc. Resection of TRP-mCF tumors resulted in a significant extension of survival and a slower rate of weight loss compared to control (no procedure) and sham-resected animals. We did not observe significant differences in survival and weight loss between sham and control mice. Similarl to TRP-mCF tumors, resection of GL261 Red-FLuc tumors led to increased survival, reduced weight loss, and slower tumor growth compared to control mice. The extent of tumor resection did not significantly impact survival, as over 95% of the tumor was resected in most mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Bioware® Brite GL261 Red-FLuc cells (BW134246) were purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA) and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 1,000 mg/L glucose, 584 mg/L L-glutamine, and 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), and 2 µg/ml puromycin (BioVision, Waltham, MA, USA). TRP-mCF cells were a generous gift from Dr. Shawn Hingtgen (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA). TRP-mCF cells were maintained in DMEM containing 4,500 mg/L glucose, 584 mg/L L-glutamine, 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), and 1x penicillin-streptomycin (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA). Cells were cultured in a Heraeus HERAcell 150 CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, PA, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell morphology, proliferation, and confluence were assessed at 100x magnification with a TELAVAL 31 inverted transmitted light microscope (Zeiss, White Plains, NY, USA). Once at 80-90% confluence, cells were treated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS with 1.05 mM KH2PO4, 154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM Na2HPO4; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) for 3 minutes at 37°C. Trypsinization was stopped with 2x volume of medium. Cells were centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min and resuspended in culture medium. A Scepter 2.0 handheld automated cell counter (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) was used to count cells for experiments. Cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma using either the PCR Mycoplasma Test Kit I/C (PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, DE) or the MycoStrip™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.2. In Vitro Fluorescence Assay

For in vitro fluorescence assays with 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), 12,500 and 25,000 cells/well were plated in black clear-bottom 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. The following day, the cell culture medium was removed, and 200 µL of 5-ALA (1 mM) dissolved in phenol red-free DMEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, PA, USA) was added to each well. Fluorescence was measured every 15 min using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) for 4h (excitation: 405 nm; emission: 635 nm). Blank wells containing only 1 mM 5-ALA were averaged for each time point and subtracted from wells containing cells. Data were plotted and analyzed using GraphPad Prism® (v9).

2.3. Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #2018-2947; PI: Bauer). The University of Kentucky Division of Laboratory Animal Resources is an AAALAC-accredited institution, and experiments were carried out per the US Department of Agriculture Animal Welfare Act and by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Seven-week-old female albino B6 (B6(Cg)-

Tyrc-2J/J (Strain No: 000058) (total n = 15) and eight-week-old female homozygous J:NU (Strain No: 007850) (total n = 53) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Female mice were used because the GL261 cells are female-derived, and it is conventional to maintain consistency with the gender of the tumor host for syngeneic models [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Female mice were used for the TRP-mCF model to stay consistent between models. Mice were group-housed in cages connected to an EcoFlo ventilation system (Allentown Inc., Allentown, NJ, USA) in an AAALAC-accredited temperature- and humidity-controlled facility at the University of Kentucky (21-22°C, 30-70% humidity, 14:10 hour light:dark cycle). Mice received water and standard chow

ad libitum (Envigo Teklad Chow 2918, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

2.4. Orthotopic Mouse Glioblastoma Models

GBM cell implantations were based on previously published protocols from Carlson et al. for GL261 Red-FLuc [

34,

35,

36] and El Meskini et al. for TRP-mCF [

37]. On the day before intracranial implantations, heads of albino B6 mice (TRP-mCF model) were shaved with a cordless hair trimmer under 1.5-2.5% isoflurane. On the morning of the procedure, albino B6 (TRP-mCF model) or J:NU (GL261 Red-FLuc model) mice were injected with buprenorphine ER-LAB (1 mg/kg, s.c., ZooPharm, Laramie, WY, USA). Cells were rinsed, trypsinized, and collected as described above. Cell pellets were resuspended in PBS at 2,500 cells/µL, and the cell solutions were kept on ice during the surgeries. In an induction chamber, mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane using a SomnoSuite

® anesthesia system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA). Once under anesthesia, mice were transferred to a platform with an infrared warming pad (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA) and positioned into a stereotaxic head frame and anesthesia mask (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Isoflurane was switched from the induction chamber to the nose cone and maintained at 1-2% for the procedure. Alternating swabs of 2% chlorhexidine (Covetrus, Portland, ME, USA) and sterile saline (Covetrus, Portland, ME, USA) were used to sterilize the animal’s head. Following sterilization of the surgical area, sterile gloves were donned, a 1 cm midline incision was made using a 22-blade sterile disposable scalpel (Sklar, West Chester, PA, USA), and the skin was retracted using mini-Colibri retractors (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA). The periosteum was gently removed with cotton-tipped applicators, and bregma was visualized with 3% H

2O

2 (Ward’s Science, Rochester, NY, USA). An MH-170 rotary handpiece (Foredom Electric Company, Bethel, CT, USA) with 0.9 mm micro drill burr (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to create a burr hole at the following coordinates: 2 mm mediolateral and -2 mm anteroposterior from bregma. Cells were gently resuspended and loaded into a 5 µL Hamilton syringe with a 22sG needle (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA). The exterior of the needle was wiped with an alcohol prep pad to remove any residual cells, then positioned over the burr hole flush with the brain. After each injection, the needle was flushed with PBS.

For the TRP-mCF model, the needle was incrementally inserted into the brain at a rate of 1 mm/min to a depth of 4 mm, then removed 1 mm to create a pocket for the cells; 2 µL of the TRP-mCF cell suspension was injected over six minutes (0.33 µL/min). The needle remained for one minute before it was removed incrementally at a rate of 1 mm/min. Any leakage/blood at the injection site was removed with a cotton-tipped applicator, followed by gentle scrubbing with an EtOH-soaked cotton-tipped applicator to remove any cells that might have made it onto the skull. A piece of bone wax (Covetrus, Portland, ME, USA) was shaped into a cone (~1 mm) and placed into the burr hole to prevent any extracranial growth.

For the GL261 Red-FLuc model, the needle was slowly inserted over 10 seconds into the burr hole to a depth of 4 mm, then removed 1 mm to create a pocket for the cells; 2µL of the GL261 Red-FLuc cell suspension was injected over two minutes (1 µL/min). The needle remained for one minute before it was removed within 10 seconds. Any leakage/blood at the injection site was removed with a cotton-tipped applicator, followed by gentle scrubbing with an EtOH-soaked cotton-tipped applicator to remove any cells that might have made it onto the skull.

The burr hole was sealed with bone wax. Specifically, standard pattern forceps (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA) were heated in a Germinator 500 glass bead sterilizer (CellPoint Scientific, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and used to melt and apply bone wax over the site. The skin was closed with 9mm wound clips (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA), and the mouse was moved to a clean cage on a heating pad (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). Mice were monitored for at least 3h post-surgery until they exhibited normal behavior, including regular grooming, exploratory activity, and ambulation without signs of distress. In the days following injections, we observed the mice daily until they reached a humane endpoint, which included 25% bodyweight loss, signs of altered behavior, imbalance, head tilt, or altered respiration [

38,

39].

2.5. Bioluminescence Imaging

In vivo, bioluminescence imaging was conducted weekly to verify tumor take and monitor tumor growth of GL261 Red-FLuc mice. Mice received XenoLight® RediJect™ D-luciferin (150 mk/kg, 5 µl/g; i.p., PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. Eyes were lubricated with OptixCare® eye lube (Covetrus, Portland, ME, USA), and mice were transferred to the heated imaging stage of a Lago in vivo optical imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, AZ, USA). Ten minutes post-luciferin injection, tumor bioluminescence was determined by 2D imaging (FOV: 21.6 cm, f-stop: 2, binning: 4), and images were analyzed with Aura Imaging 4.0.7 software (Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, AZ, USA).

2.6. T2-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging

We confirmed successful TRP-mCF tumor engraftment 2 weeks post-implantation using T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI was conducted at the University of Kentucky Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy Center. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5-2% isoflurane and transferred to the platform of a 7T Bruker BioSpec small animal MRI scanner (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA, USA). Eyes were lubricated with OptixCare® eye lube (Covetrus, Portland, ME, USA), and vital signs were monitored using a respiration pad transducer and rodent rectal temperature probe. T2-weighted images were obtained with acquisition parameters as follows: repetition time (TR) of 4000 ms, echo time (TE) of 33 ms, and a field of view (FOV) measuring 20 x 20 x 8. Images were analyzed using syngo. via software (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA). Following imaging, mice were allowed to recover in a warmed cage before being returned to their home cages.

2.7. Fluorescence-Guided Tumor Resection

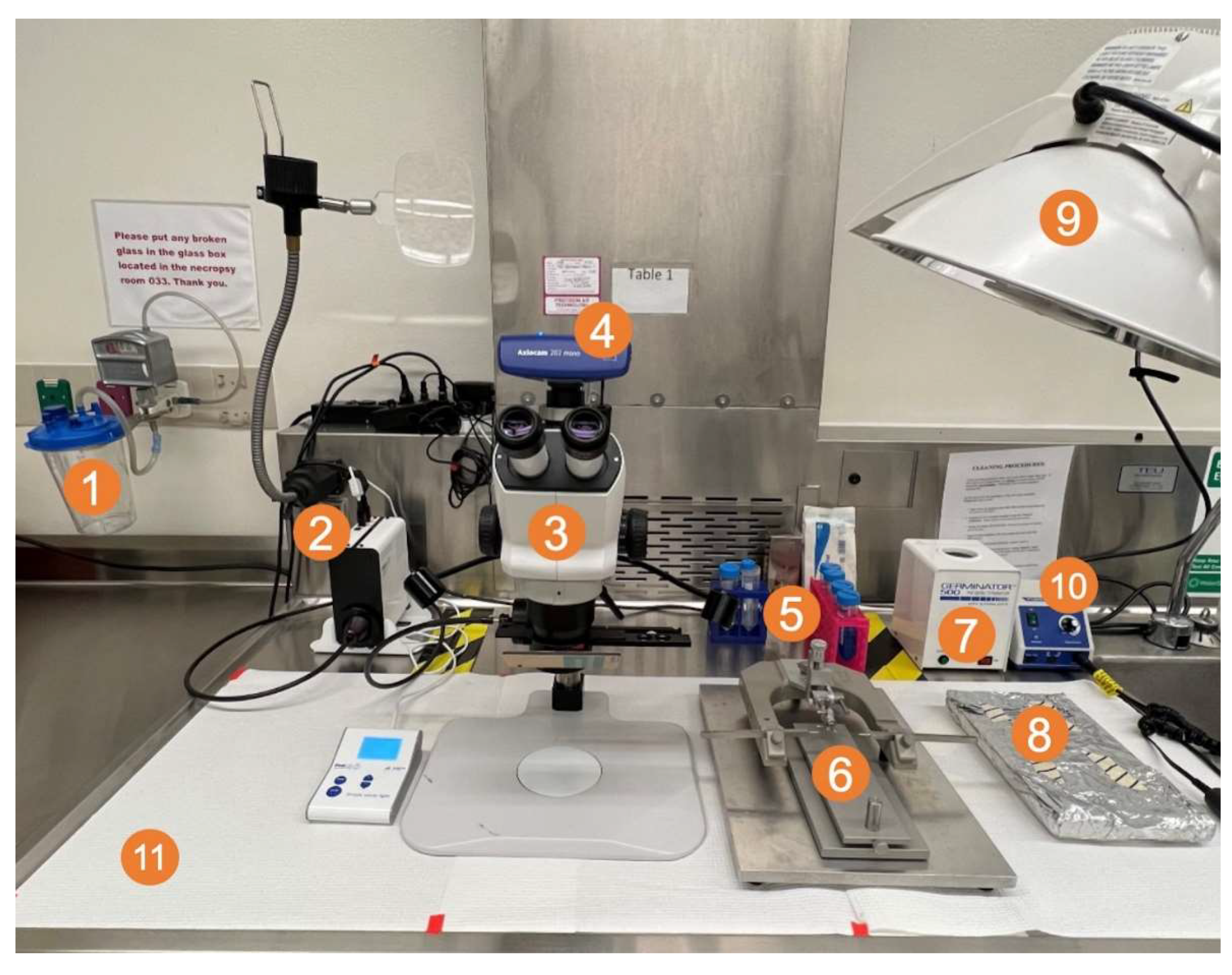

On the day before resection, tumors were verified using in vivo bioluminescence imaging (GL261 Red-FLuc) or T2-weighted MRI (TRP-mCF). Then, mice with tumors were randomized into groups (e.g., control, sham, or resection), and albino B6 mouse heads were shaved. A picture of the surgical setup and a brief schematic of the procedure are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, respectively. The preparatory and positioning procedures for the animals closely mirrored those detailed in the intracranial injection procedure. On the morning of the resection, albino B6 (TRP-mCF model; day 15 post-implantation) or J:NU (GL261 Red-FLuc model; day 14 post-implantation) mice were injected with buprenorphine ER-LAB (1 mg/kg, s.c.). Two hours before the start of the resection, mice were injected with 5-ALA (500 mg/kg; saline; i.p.). In an induction chamber, mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane using a SomnoSuite

® anesthesia system. Once under anesthesia, mice were transferred to a platform with an infrared warming pad and positioned into a stereotaxic head frame and anesthesia mask. Isoflurane was switched from the induction chamber to the nose cone and maintained at 1-2% for the procedure. Alternating swabs of 2% chlorhexidine and sterile saline were used to sterilize the animal’s head. Following sterilization of the surgical area, a 1 cm midline incision was made using a 22-blade sterile disposable scalpel, and the skin was retracted using mini-Colibri retractors (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA). The periosteum was gently removed with cotton-tipped applicators, and the previous burr hole was visualized. A circular cranial window of about 2.5 mm in diameter was created by thinning the skull with an MH-170 rotary handpiece and 0.9 mm micro drill burr. Once the skull was thin enough, 1-2 drops of saline were added before gently lifting the inner portion. Blood and excess saline were removed with sterile cotton tips. An autoclaved reusable 2 mm sample corer (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA) was inserted into the established cranial window to a depth of 2 mm. The corer was gently twisted for 10 seconds to separate the tissue and then gently removed. Using a ZEISS Stemi 508 Stereo Microscope with chroma filter set AT425/50x, AT485DC, AT655/30m (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, DE), the fluorescent tumor tissue was identified, and the biopsy was gently aspirated with a Pasteur pipette attached to a medical vacuum system (BeaconMedaes, Rock Hill, SC, USA). Remaining fluorescent tissue and blood were removed gently with suction alternating between fluorescence guidance and white light. Gentle pressure was applied over the resection site using a sterile cotton-tipped applicator until any active bleeding subsided. To recreate a closed system, the cranial window was covered with a 3 mm x 3 mm piece of Neuro-Patch

® dura substitute (Aesculap, Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA), which was sealed using veterinary surgical adhesive (Covetrus, Portland, ME, USA) and bone wax. The skin was closed with 9 mm wound clips, and the mouse was moved to a clean cage on a heating pad. A petri dish with moistened food was placed on the ground to aid recovery. Mice were closely monitored for at least 3 hours post-surgery until they exhibited normal behavior, including regular grooming, exploratory activity, and ambulation without signs of distress. Following injections, daily observations continued until they reached a humane endpoint, including a 25% bodyweight loss or signs of altered behavior, imbalance, head tilt, or respiration. Sham mice underwent the same resection procedure (administration of buprenorphine, 5-ALA, and isoflurane; craniectomy; and Neuro-Patch

® placement) except for the removal of brain tissue. Control mice received no intervention.

2.8. Data Analysis & Statistics

Data were analyzed by generalized mixed-level linear models for all data except Cox survival models were applied to survival times, and joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data [

40] were applied to mean change in body weight and mean post-resection luminescence vs time. Joint modeling was done for time points beginning on the day of resection and ending on the last day when more than one animal was alive in a group. Nakagawa’s coefficient of determination (

R2) was used [

41] for all models except for Cox models, where Nagelkerke’s

R2 [

42] was used. Comparing more than two pairwise differences was challenging since no formal method is known for such comparisons in joint models. Therefore, pairwise models were also constructed, and p values for hazard ratios and longitudinal trends were adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate [

43]. Analysis was performed with the R statistical environment [

44] and the JM [

45], lme4 [

46], performance [

47], and survival [

48] packages.

3. Results

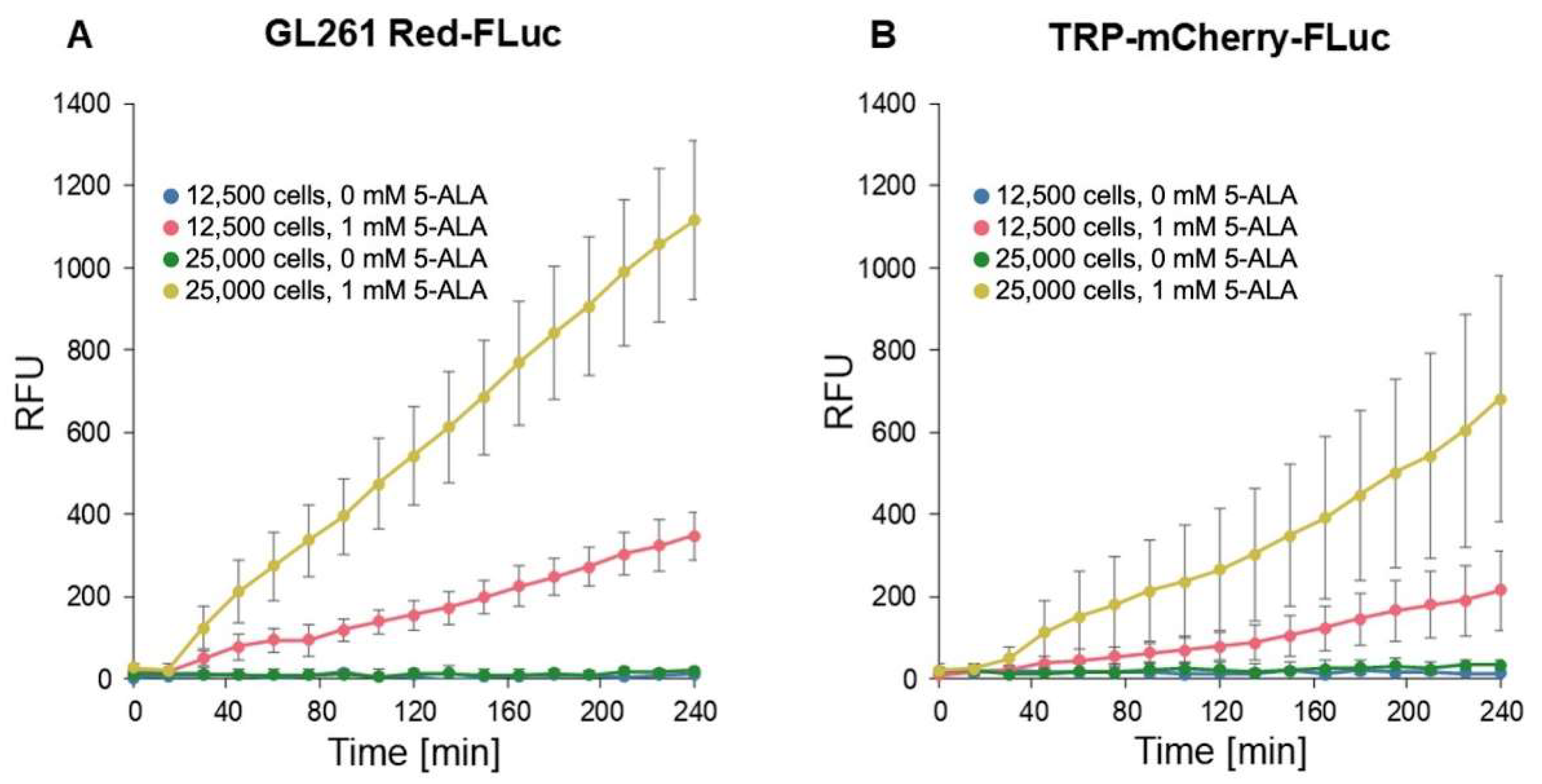

3.1. In Vitro 5-ALA-Induced Fluorescence of GL261 Red-FLuc and TRP-mCF Cells

We conducted fluorescence imaging to confirm in vitro porphyrin accumulation in GL261 Red-FLuc and TRP-mCF cells (

Figure 4). Cells were seeded at densities of 12,500 and 25,000 cells/well and allowed to settle overnight. Subsequently, 1 mM 5-ALA was added, and fluorescence intensity (RFU; Ex: 405 nm; Em: 635 nm) was measured every 15 min over 4 hours. The fluorescence intensity of wells exposed to 5-ALA exhibited a significant increase over time, as indicated by the slope of RFU/time, compared to untreated cultures (

Figure 4,

Table 1). This enhancement was observed in both cell types, and fluorescence varied significantly based on cell seeding density. We began analysis at the 15-minute timepoint due to a discernible lag in signal change between 0 and 15 minutes. Appropriate pairwise comparisons (

Table 2) showed that 5-ALA significantly enhanced signal development over time, and the initial cell count also significantly increased fluorescence. Additionally, GL261 Red-FLuc cells exhibited a higher signal compared to TRP-mCF cells.

3.2. Resection of TRP-mCF Tumors Significantly Extended Mouse Survival and Slowed Weight Loss

When evaluating the impact of resection across control, sham-resected, and resected TRP-mCF animals, we observed a significant increase in survival following resection, with median survival durations of 27, 26, and 34d, respectively (p < 0.001) (

Figure 5A). In addition, the rate of weight loss, assessed as the percent difference from day 0, was significantly slower in resected animals compared to both control and sham-operated animals (

Figure 5B). A transient decrease in mean weight was observed in mice who underwent resection for the two days following resection; however, these mice began to regain weight by the third day after the procedure. In contrast, no post-surgical weight loss was observed in the sham-operated mice. Of note, the abrupt increases in weight observed in both sham and resected mice on days 26 and 35 were attributed to the loss of mice with 25% weight loss nearing the experimental endpoint, with the remaining animals’ weights contributing to sharp rises in the group average.

3.3. Resection of GL261 Red-FLuc Tumors Extended Survival, Reduced Weight Loss, and Slowed Tumor Growth

We also resected tumors in GL261 Red-FLuc mice and monitored their survival, weight loss, and relative tumor growth (

Figure 6). Sham-operated animals were omitted from this study as there was no difference in survival or rate of body weight loss compared to controls (

Figure 5). Representative images depicting 5-ALA-induced fluorescence of tumor pre- and post-resection, along with the temporal progression of tumor bioluminescence, are illustrated in

Figure 6A and

Figure 6B, respectively. Resection resulted in a significant increase in survival compared to unresected controls (27 vs 32d; p <0.001) (

Figure 6C). Additionally, weight loss in resected animals was significantly slower than in unresected animals (

Figure 6D,

Table 3). Similar to observations in TRP-mCF mice, the abrupt increases in weight towards the end of the study were attributed to the loss of mice with 25% weight loss nearing the experimental endpoint, with the remaining animals’ weights contributing to sharp rises in the group average. Therefore, we caution from overinterpreting the predicted trend for weight change in resected animals, as median survival for resected animals was at 27 days. As time progressed, fewer animals survived, enhancing any survivor effect on the overall trend. While tumor (re)growth was slower in resected animals (

Figure 6E,

Table 4), the association coefficient was not significant, indicating that the event process (death) did not significantly influence the trajectory of the longitudinal process (luminescence) in this context. Regarding the extent of resection, bioluminescence levels on the day following resection exhibited a significant decrease compared to corresponding pre-resection values, with an average reduction in tumor bioluminescence of 91.6% (

Figure 6F). Finally, we explored whether the extent of resection impacted survival (

Figure 6G), a factor demonstrated in clinical studies [

12,

13,

14]. However, we observed no significant effect, which was anticipated given that 86% of mice underwent resection of at least 85% of the tumor, and 67% had tumor resection exceeding 95% (

Figure 6G inset). Overall, these findings emphasize the survival advantage conferred by tumor resection and reinforce the importance of surgical intervention in preclinical GBM models.

4. Discussion

The gap between promising preclinical GBM studies and their limited clinical translation remains a significant challenge in advancing patient outcomes. Despite the insights provided by preclinical models, their applicability and translatability to clinical settings often fall short [

10]. As the impact of surgery on recurrent GBM becomes increasingly evident [

16,

17,

18], incorporating surgical interventions into preclinical models, as demonstrated in our study, has the potential to narrow this gap and enhance translational efficacy.

Despite mounting evidence highlighting the significance and impact of surgery in GBM, preclinical models incorporating resection procedures remain limited. Existing protocols for punch biopsy or fluorescence-guided surgery using labeled cells offer certain advantages but also present limitations [

25,

26,

27,

49]. Punch biopsy, for instance, provides a faster but less invasive method for excising a section of tumor tissue compared to alternative approaches involving visualization paired with aspiration or microdissection [

49]. However, punch biopsy procedures result in variable amounts of residual tumor tissue, leading to inconsistencies in survival outcomes among treatment groups.

On the other hand, fluorescence-guided surgery closely simulates maximal safe surgical resection performed in patients, making it a promising technique. However, most protocols for fluorescence-guided resection in preclinical models rely on labeled cells with limited clinical relevance [

25,

26,

27]. Moreover, these procedures typically implant tumors at shallow depths (0.5 – 1 mm) and are left as open systems without closure of the craniotomy. These aspects fail to replicate the invasiveness of patient tumors [

50] and the normalization of intracranial pressure observed in clinical settings [

51,

52]. While some groups have explored the use of alternative fluorescent imaging agents, such as sodium fluorescein [

53], 5-ALA is currently the only FDA-approved imaging agent for glioma surgery [

54]. Previous studies have demonstrated the visualization of GBM tumors in preclinical models using 5-ALA, but these investigations primarily served as proof-of-principle studies and did not assess animal survival [

28,

29].

Our protocol offers several advantages, including using 5-ALA, validation across two distinct mouse GBM models with differing phenotypes, targeting deep-seated tumors, and adopting a closed system approach, which may effectively mitigate potential confounding variables. Interestingly, our protocol demonstrated a slower regrowth of recurrent tumors compared to untreated controls, contrasting with previous observations of rapid growth following resection in other studies [

17,

25]. This discrepancy could stem from differences in resection procedures, such as our use of a closed system and the resulting maintenance of intracranial pressure, the implantation of deep-seated tumors, or model-specific factors; however, further investigation would be necessary to elucidate this difference.

On the other hand, it is also important to acknowledge the limitations of our technique, including the absence of other components of the standard of care, which have also been shown to affect recurrent disease [

55,

56], and the time-intensive and invasive nature of the procedure, which may contribute to initial weight loss in animals. Furthermore, 5-ALA is considered a nonspecific imaging agent, and fluorescence could exhibit greater variability compared to labeled cells; however, studies have demonstrated an overlap between 5-ALA fluorescence and GFP-labeled tumors [

25]. Lastly, 5-ALA fluorescence was dim in deeper brain regions and challenging to distinguish in active bleeding, leading to prolonged operation times.Despite these considerations, our technique presents an innovative approach to fluorescence-guided tumor resection in preclinical models, offering valuable insights into recurrent tumor growth dynamics and informing the potential efficacy of adjuvant therapies.

5. Conclusions

Our study underscores the critical need for improved preclinical models in GBM research to bridge the gap between experimental findings and clinical outcomes. Despite the growing recognition of the pivotal role of surgery in GBM management, existing preclinical protocols for tumor resection remain limited in their translational relevance and applicability. Our innovative approach, utilizing 5-ALA-guided resection validated across two distinct mouse GBM models, addresses some limitations by targeting deep-seated tumors and adopting a closed-system approach. Our protocol offers a promising approach to studying GBM and evaluating novel therapeutic strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.R., A.M.S.H. and B.B.; methodology, L.T.R.; software, L.T.R. and B.J.M.; validation, L.T.R.; formal analysis, L.T.R. and B.J.M.; investigation, L.T.R. and B.B.; resources, A.M.S.H. and B.B.; data curation, B.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.R., B.J.M. and B.B.; writing—review and editing, L.T.R., B.J.M, A.M.S.H. and B.B.; visualization, L.T.R. and B.J.M.; supervision, A.M.S.H and B.B.; project administration, B.B.; funding acquisition, L.T.R and B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health, grant number R01NS107548 (BB); the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, grant number TL1TR001997 (LTR); and the Northern Kentucky/Greater Cincinnati UK Alumni Club Fellowship (LTR). The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the NIH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #2018-2947; PI: Bauer, approval date: 26 July 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank all Bauer and Hartz research team members for proofreading this manuscript. We especially thank Yuma Tega and Yingying Gu for their technical assistance with implantation and imaging procedures. This research was supported by the Biospecimen Procurement and Translational Pathology and Small Animal Imaging Facility Shared Resource Facilities of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558) and the University of Kentucky Light Microscopy Core and Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Price, M.; Neff, C.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2016-2020. Neuro Oncol 2023, 25, iv1-iv99. [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 987-996. [CrossRef]

- Vanderbeek, A.M.; Rahman, R.; Fell, G.; Ventz, S.; Chen, T.; Redd, R.; Parmigiani, G.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Wen, P.Y.; Trippa, L.; et al. The clinical trials landscape for glioblastoma: is it adequate to develop new treatments? Neuro Oncol 2018, 20, 1034-1043. [CrossRef]

- Herrlinger, U.; Tzaridis, T.; Mack, F.; Steinbach, J.P.; Schlegel, U.; Sabel, M.; Hau, P.; Kortmann, R.D.; Krex, D.; Grauer, O.; et al. Lomustine-temozolomide combination therapy versus standard temozolomide therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CeTeG/NOA-09): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 678-688. [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Taillibert, S.; Kanner, A.; Read, W.; Steinberg, D.; Lhermitte, B.; Toms, S.; Idbaih, A.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Fink, K.; et al. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 2306-2316. [CrossRef]

- Oster, C.; Schmidt, T.; Agkatsev, S.; Lazaridis, L.; Kleinschnitz, C.; Sure, U.; Scheffler, B.; Kebir, S.; Glas, M. Are we providing best-available care to newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients? Systematic review of phase III trials in newly diagnosed glioblastoma 2005–2022. Neuro-Oncology Advances 2023, 5, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Aldape, K.; Brindle, K.M.; Chesler, L.; Chopra, R.; Gajjar, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Gottardo, N.; Gutmann, D.H.; Hargrave, D.; Holland, E.C.; et al. Challenges to curing primary brain tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019, 16, 509-520. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.F.; Young, J.S.; Amara, D.; Berger, M.S.; Raleigh, D.R.; Aghi, M.K.; Butowski, N.A. Mouse models of glioblastoma for the evaluation of novel therapeutic strategies. Neurooncol Adv 2021, 3, vdab100. [CrossRef]

- Akter, F.; Simon, B.; Leonie de Boer, N.; Redjal, N.; Wakimoto, H.; Shah, K. Pre-clinical tumor models of primary brain tumors: Challenges and opportunities. BBA - Reviews on Cancer 2021, 1875, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Gunjur, A.; Balasubramanian, A.; Hafeez, U.; Menon, S.; Cher, L.; Parakh, S.; Gan, H.K. Poor correlation between preclinical and patient efficacy data for tumor targeted monotherapies in glioblastoma: the results of a systematic review. J Neurooncol 2022, 159, 539-549. [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W.; Reulen, H.J.; Meinel, T.; Pichlmeier, U.; Schumacher, W.; Tonn, J.C.; Rohde, V.; Oppel, F.; Turowski, B.; Woiciechowsky, C.; et al. Extent of resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: identification of and adjustment for bias. Neurosurgery 2008, 62, 564-576; discussion 564-576. [CrossRef]

- McGirt, M.J.; Chaichana, K.L.; Gathinji, M.; Attenello, F.J.; Than, K.; Olivi, A.; Weingart, J.D.; Brem, H.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A. Independent association of extent of resection with survival in patients with malignant brain astrocytoma. J Neurosurg 2009, 110, 156-162. [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, M.; Abi-Said, D.; Fourney, D.R.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Shi, W.; DeMonte, F.; Lang, F.F.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Hassenbusch, S.J.; Holland, E.; et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg 2001, 95, 190–198. [CrossRef]

- Sanai, N.; Polley, M.-Y.; McDermott, M.W.; Parsa, A.T.; Berger, M.S. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg 2011, 115, 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W.; Kamp, M.A. The importance of surgical resection in malignant glioma. Curr Opin Neurol 2009, 22, 645-649. [CrossRef]

- Alieva, M.; Margarido, A.S.; Wieles, T.; Abels, E.R.; Colak, B.; Boquetale, C.; Jan Noordmans, H.; Snijders, T.J.; Broekman, M.L.; van Rheenen, J. Preventing inflammation inhibits biopsy-mediated changes in tumor cell behavior. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 7529. [CrossRef]

- Okolie, O.; Bago, J.R.; Schmid, R.S.; Irvin, D.M.; Bash, R.E.; Miller, C.R.; Hingtgen, S.D. Reactive astrocytes potentiate tumor aggressiveness in a murine glioma resection and recurrence model. Neuro Oncol 2016, 18, 1622-1633. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, A.M.; Halle, B.; Cedile, O.; Burton, M.; Baun, C.; Thisgaard, H.; Anand, A.; Hubert, C.; Thomassen, M.; Michaelsen, S.R.; et al. Surgical resection of glioblastomas induces pleiotrophin-mediated self-renewal of glioblastoma stem cells in recurrent tumors. Neuro Oncol 2022, 24, 1074-1087. [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W.; Pichlmeier, U.; Meinel, T.; Wiestler, O.D.; Zanella, F.; Reulen, H.-J. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 2006, 7, 392-401. [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J.W.; Buitelaar, M.; Wagenaar, E.; van der Valk, M.A.; Scheffer, G.L.; Scheper, R.J.; Plösch, T.; Kuipers, F.; Elferink, R.P.J.O.; Rosing, H.; et al. The breast cancer resistance protein protects against a major chlorophyll-derived dietary phototoxin and protoporphyria. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99, 15649-15654. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.G.; Chen, X.F.; Wang, L.G.; Yang, G.; Han, D.Y.; Teng, L.; Yang, M.C.; Wang, D.Y.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.H.; et al. Increased expression of ABCB6 enhances protoporphyrin IX accumulation and photodynamic effect in human glioma. Ann Surg Oncol 2013, 20, 4379-4388. [CrossRef]

- Traylor, J.I.; Pernik, M.N.; Sternisha, A.C.; McBrayer, S.K.; Abdullah, K.G. Molecular and Metabolic Mechanisms Underlying Selective 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Induced Fluorescence in Gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, M.; Szczepanek, D.; Orzyłowska, A.; Rola, R. Analysis of Factors Affecting 5-ALA Fluorescence Intensity in Visualizing Glial Tumor Cells—Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Kauer, T.M.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Hingtgen, S.; Shah, K. Encapsulated therapeutic stem cells implanted in the tumor resection cavity induce cell death in gliomas. Nat Neurosci 2011, 15, 197-204. [CrossRef]

- Hingtgen, S.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Farrar, C.; Duebgen, M.; Martinez-Quintanilla, J.; Bhere, D.; Shah, K. Real-time multi-modality imaging of glioblastoma tumor resection and recurrence. J Neurooncol 2013, 111, 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Momiyama, M.; Hiroshima, Y.; Suetsugu, A.; Tome, Y.; Mii, S.; Yano, S.; Bouvet, M.; Chishima, T.; Endo, I.; Hoffman, R.M. Enhanced resection of orthotopic red-fluorescent-protein-expressing human glioma by fluorescence-guided surgery in nude mice. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 107-111.

- Sheets, K.T.; Bago, J.R.; Paulk, I.L.; Hingtgen, S.D. Image-Guided Resection of Glioblastoma and Intracranial Implantation of Therapeutic Stem Cell-seeded Scaffolds. J Vis Exp 2018. [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, N.L.; Georges, J.; Eschbacher, J.M.; Cavalcanti, D.D.; Elhadi, A.M.; Abdelwahab, M.G.; Scheck, A.C.; Nakaji, P.; Spetzler, R.F.; Preul, M.C. Potential application of a handheld confocal endomicroscope imaging system using a variety of fluorophores in experimental gliomas and normal brain. Neurosurg Focus 2014, 36, E16. [CrossRef]

- Belykh, E.; Miller, E.J.; Hu, D.; Martirosyan, N.L.; Woolf, E.C.; Scheck, A.C.; Byvaltsev, V.A.; Nakaji, P.; Nelson, L.Y.; Seibel, E.J.; et al. Scanning Fiber Endoscope Improves Detection of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Induced Protoporphyrin IX Fluorescence at the Boundary of Infiltrative Glioma. World Neurosurg 2018, 113, e51-e69. [CrossRef]

- Enriquez Perez, J.; Kopecky, J.; Visse, E.; Darabi, A.; Siesjo, P. Convection-enhanced delivery of temozolomide and whole cell tumor immunizations in GL261 and KR158 experimental mouse gliomas. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 7. [CrossRef]

- Garbow, J.R.; Johanns, T.M.; Ge, X.; Engelbach, J.A.; Yuan, L.; Dahiya, S.; Tsien, C.I.; Gao, F.; Rich, K.M.; Ackerman, J.J.H. Irradiation-Modulated Murine Brain Microenvironment Enhances GL261-Tumor Growth and Inhibits Anti-PD-L1 Immunotherapy. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 693146. [CrossRef]

- Renner, D.N.; Malo, C.S.; Jin, F.; Parney, I.F.; Pavelko, K.D.; Johnson, A.J. Improved Treatment Efficacy of Antiangiogenic Therapy when Combined with Picornavirus Vaccination in the GL261 Glioma Model. Neurotherapeutics 2016, 13, 226-236. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, V.E.; Lynes, J.P.; Walbridge, S.; Wang, X.; Edwards, N.A.; Nwankwo, A.K.; Sur, H.P.; Dominah, G.A.; Obungu, A.; Adamstein, N.; et al. GL261 luciferase-expressing cells elicit an anti-tumor immune response: an evaluation of murine glioma models. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 11003. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.L.; Pokorny, J.L.; Schroeder, M.A.; Sarkaria, J.N. Establishment, maintenance and in vitro and in vivo applications of primary human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) xenograft models for translational biology studies and drug discovery. In Curr Protoc Pharmacol, 2011/07/12 ed.; James Wiley & Sons: Hoboken NJ, 2011; pp. 1-14.

- Schulz, J.A.; Rodgers, L.T.; Kryscio, R.J.; Hartz, A.M.S.; Bauer, B. Characterization and comparison of human glioblastoma models. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 844. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, L.T.; Schulz Pauly, J.A.; Maloney, B.J.; Hartz, A.M.S.; Bauer, B. Optimization, Characterization, and Comparison of Two Luciferase-Expressing Mouse Glioblastoma Models. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- El Meskini, R.; Atkinson, D.; Weaver Ohler, Z. Translational Orthotopic Models of Glioblastoma Multiforme. J Vis Exp 2023. [CrossRef]

- Toth, L.A. Defining the Moribound Condition as an Experimental Endpoint for Animal Research. ILAR Journal 2000, 41, 72-79.

- Wallace, J. Humane endpoints and cancer research. ILAR J 2000, 41, 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Rizopoulos, D. Joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data: with applications in R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2012; pp. xiv, 261 p.

- Nakagawa, S.J., P. C. D.; Schielzeth, H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2017, 14. [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerke, N.J.D. A Note on a General Definition of the Coefficient of Determination. Biometrika 1991, 78, 691-692. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995, 57, 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Ihaka, R.; Gentleman, R. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 1996, 5, 299-314. [CrossRef]

- Rizopoulos, D. JM: An R Package for the Joint Modelling of Longitudinal and Time-to-Event Data. Journal of Statistical Software 2010, 35, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Statistical Software 2015, 67, 1-48. [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.S.; Patil, I.; Waggoner, P.; Makowski, D. performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. The Journal of Open Source Software 2021, 6, 3139. [CrossRef]

- Therneau, T. A package for survival analysis in R. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (accessed on April 23, 2024).

- Bianco, J.; Bastiancich, C.; Joudiou, N.; Gallez, B.; des Rieux, A.; Danhier, F. Novel model of orthotopic U-87 MG glioblastoma resection in athymic nude mice. J Neurosci Methods 2017, 284, 96-102. [CrossRef]

- de Gooijer, M.C.; Guillen Navarro, M.; Bernards, R.; Wurdinger, T.; van Tellingen, O. An Experimenter’s Guide to Glioblastoma Invasion Pathways. Trends Mol Med 2018, 24, 763-780. [CrossRef]

- Lilja-Cyron, A.; Andresen, M.; Kelsen, J.; Andreasen, T.; Petersen, L.; Fugleholm, K.; Juhler, M. Intracranial pressure before and after cranioplasty: insights into intracranial physiology. Journal of Neurosurgery 2020, 133, 1548-1558. [CrossRef]

- Lilja-Cyron, A.; Andresen, M.; Kelsen, J.; Andreasen, T.; Fugleholm, K.; Juhler, M. Long-Term Effect of Decompressive Craniectomy on Intracranial Pressure and Possible Implications for Intracranial Fluid Movements. Neurosurgery 2020, 86, 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Riva, M.; Bevers, S.; Wouters, R.; Thirion, G.; Vandenbrande, K.; Vankerckhoven, A.; Berckmans, Y.; Verbeeck, J.; Keersmaecker, K.D.; Coosemans, A. Towards more accurate preclinical glioblastoma modelling: reverse translation of clinical standard of care in a glioblastoma mouse model. bioRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gleolan. Available online: https://gleolan.com/ (accessed on April 23, 2024).

- Johnson, B.E.; Mazor, T.; Hong, C.; Barnes, M.; Aihara, K.; McLean, C.Y.; Fouse, S.D.; Yamamoto, S.; Ueda, H.; Tatsuno, K.; et al. Mutational analysis reveals the origin and therapy-driven evolution of recurrent glioma. Science 2014, 343, 189-193. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Burns, T.C. Radiation-Induced Alterations in the Recurrent Glioblastoma Microenvironment: Therapeutic Implications. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 503. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Simplified 5-ALA metabolic pathway. Exogenous 5-ALA enters cells via the transporters peptide transporter 1 (PEPT1) and peptide transporter 2 (PEPT2). Endogenous 5-ALA is synthesized from succinyl-CoA and glycine in the mitochondria. Once inside the cell, 5-ALA is converted into porphobilinogen by ALA dehydratase (ALAD). Porphobilinogen is converted into coproporphyrinogen III through a series of enzymatic reactions beginning with porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD). Coproporphyrinogen III is translocated from the cytoplasm into the mitochondria by the transporter ABCB6. Protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) is produced following a series of enzymatic reactions and converted into heme by ferrochelatase (FECH). The excitation and emission wavelengths of PPIX, approximately 400-630 nm and 630-710 nm, respectively, contribute to its utility as an optical imaging agent. Figure created with BioRender.

Figure 1.

Simplified 5-ALA metabolic pathway. Exogenous 5-ALA enters cells via the transporters peptide transporter 1 (PEPT1) and peptide transporter 2 (PEPT2). Endogenous 5-ALA is synthesized from succinyl-CoA and glycine in the mitochondria. Once inside the cell, 5-ALA is converted into porphobilinogen by ALA dehydratase (ALAD). Porphobilinogen is converted into coproporphyrinogen III through a series of enzymatic reactions beginning with porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD). Coproporphyrinogen III is translocated from the cytoplasm into the mitochondria by the transporter ABCB6. Protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) is produced following a series of enzymatic reactions and converted into heme by ferrochelatase (FECH). The excitation and emission wavelengths of PPIX, approximately 400-630 nm and 630-710 nm, respectively, contribute to its utility as an optical imaging agent. Figure created with BioRender.

Figure 2.

Surgical field setup with (1) vacuum trap; (2) CoolLED pE300 multiband LED light source; (3) ZEISS Stemi 508 stereo microscope with chroma filter set AT425/50x, AT485DC, AT655/30m; (4) ZEISS Axiocam 202 mono microscope camera; (5) sterile Pasteur pipettes, cotton-tipped applicators, and tubes of 2% chlorhexidine, saline, 70% ethanol, and 3% hydrogen peroxide; (6) small animal stereotaxic frame with ear bars and adjustable platform; (7) bead sterilizer; (8) sterile surgical equipment (scalpel, forceps, drill bit, staples, staple applicator) (9) light source; and (10) micromotor kit with rotary handpiece, control box, and foot pedal (not shown).

Figure 2.

Surgical field setup with (1) vacuum trap; (2) CoolLED pE300 multiband LED light source; (3) ZEISS Stemi 508 stereo microscope with chroma filter set AT425/50x, AT485DC, AT655/30m; (4) ZEISS Axiocam 202 mono microscope camera; (5) sterile Pasteur pipettes, cotton-tipped applicators, and tubes of 2% chlorhexidine, saline, 70% ethanol, and 3% hydrogen peroxide; (6) small animal stereotaxic frame with ear bars and adjustable platform; (7) bead sterilizer; (8) sterile surgical equipment (scalpel, forceps, drill bit, staples, staple applicator) (9) light source; and (10) micromotor kit with rotary handpiece, control box, and foot pedal (not shown).

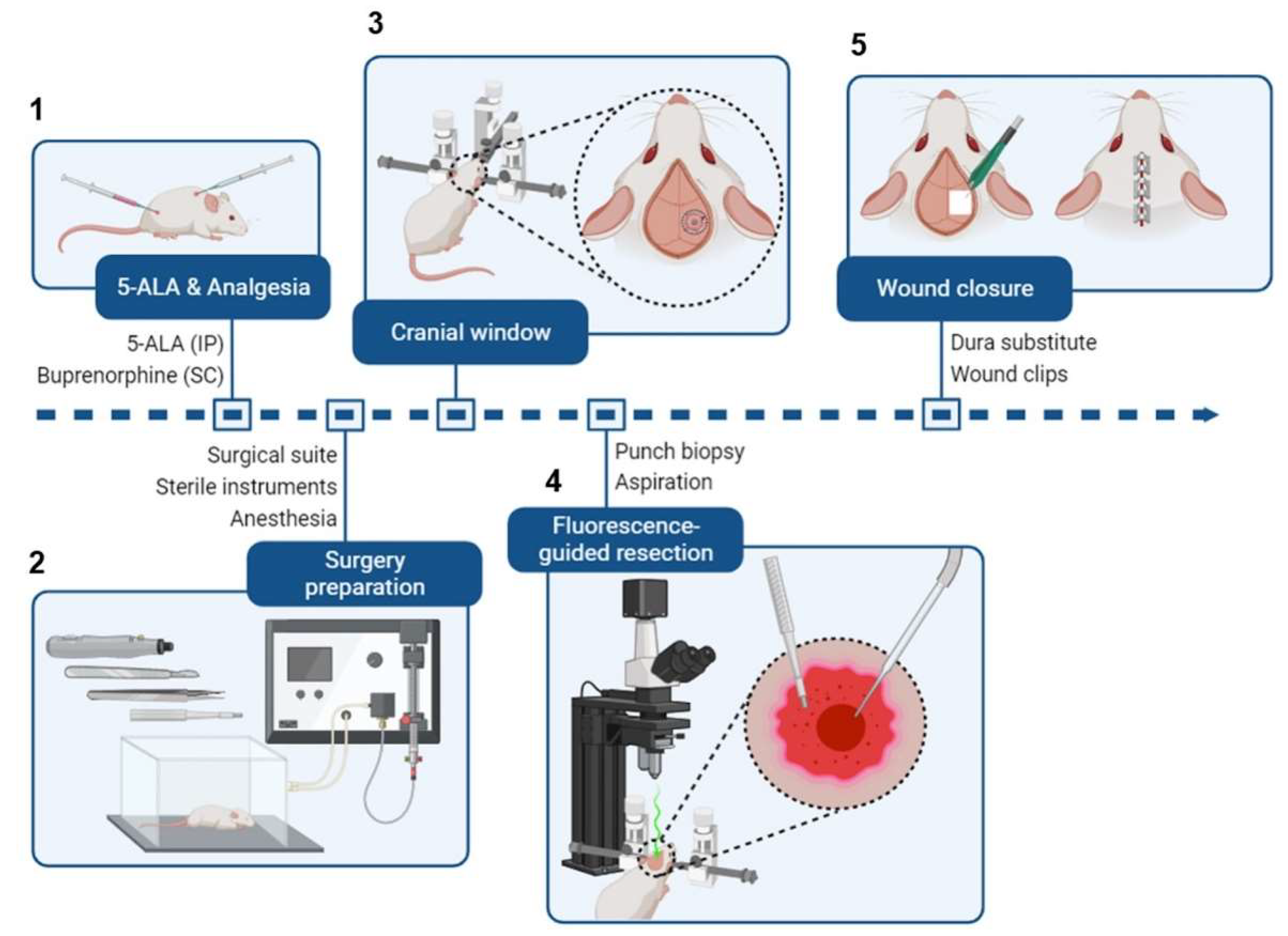

Figure 3.

Brief schematic of intracranial tumor resection from a mouse.

(A) Mice receive 5-ALA (i.p.) and buprenorphine (s.c.) 2h before surgery.

(B) Preceding the surgery, the surgical area is organized (see

Figure 2). Mice are administered isoflurane in an induction chamber.

(C) Once the mice are fully anesthetized, they are transferred to a stereotaxic frame, and the surgical site is sterilized. The scalp is cut to expose the previous burr hole, and a cranial window is created around it.

(D) A 2 mm (diameter) x 3 mm (depth) portion of the tumor is excised using a punch biopsy tool or sample corer. Then, a fluorescence-capable stereo microscope is used to detect any residual fluorescent tumor tissue, which is removed by aspiration.

(E) The cranial window is closed with a dura substitute to preserve intracranial pressure, and the wound is closed with wound clips. Figure created with BioRender.

Figure 3.

Brief schematic of intracranial tumor resection from a mouse.

(A) Mice receive 5-ALA (i.p.) and buprenorphine (s.c.) 2h before surgery.

(B) Preceding the surgery, the surgical area is organized (see

Figure 2). Mice are administered isoflurane in an induction chamber.

(C) Once the mice are fully anesthetized, they are transferred to a stereotaxic frame, and the surgical site is sterilized. The scalp is cut to expose the previous burr hole, and a cranial window is created around it.

(D) A 2 mm (diameter) x 3 mm (depth) portion of the tumor is excised using a punch biopsy tool or sample corer. Then, a fluorescence-capable stereo microscope is used to detect any residual fluorescent tumor tissue, which is removed by aspiration.

(E) The cranial window is closed with a dura substitute to preserve intracranial pressure, and the wound is closed with wound clips. Figure created with BioRender.

Figure 4.

In vitro fluorescence of GL261 Red-FLuc and TRP-FLuc following incubation with 5-ALA. (A) Quantified in vitro fluorescence of 12,500 and 25,000 GL261 Red-FLuc cells over four hours after adding either 0 mM or 1 mM 5-ALA (n = 6, 3 technical replicates; data points represent mean ± SEM). (B) Quantified in vitro fluorescence of 12,500 and 25,000 TRP-mCF cells over four hours after adding either 0 mM or 1 mM 5-ALA (n = 6, 3 technical replicates; data points represent mean ± SEM). As described in the text, 5-ALA treatment significantly increased the rate of RFU increase over time, as did higher seeding count. Errors are SEM calculated by pooled variances.

Figure 4.

In vitro fluorescence of GL261 Red-FLuc and TRP-FLuc following incubation with 5-ALA. (A) Quantified in vitro fluorescence of 12,500 and 25,000 GL261 Red-FLuc cells over four hours after adding either 0 mM or 1 mM 5-ALA (n = 6, 3 technical replicates; data points represent mean ± SEM). (B) Quantified in vitro fluorescence of 12,500 and 25,000 TRP-mCF cells over four hours after adding either 0 mM or 1 mM 5-ALA (n = 6, 3 technical replicates; data points represent mean ± SEM). As described in the text, 5-ALA treatment significantly increased the rate of RFU increase over time, as did higher seeding count. Errors are SEM calculated by pooled variances.

Figure 5.

Effects of TRP-mCF tumor resection on survival and weight change. Animals were implanted with 5,000 TRP-mCF cells on day 0, and tumors were resected in one third of the animals on day 15 (n = 5/group). (A) Survival curve of control, sham, and resection TRP-mCF mice with median survivals of 27, 26, and 34d, respectively. Analysis of survival using a Cox model demonstrated that resection enhanced median survival. The dotted line corresponds to the day of sham or resection procedures (d15). (B) Normalized (% of day 0) weight of control, sham, and resection mice. The dotted line corresponds to the day of sham or resection procedures (d15). Following tumor resection, mice exhibited initial weight loss compared to control and sham-operated groups, with subsequent weight recovery observed by day 3 post-surgery. (C) Estimated marginal trends (slopes) for weight change and hazard ratios for survival. (D) Analysis of % weight change from day 0 by joint longitudinal and time-to-event model, showing that resection significantly reduced the rate of weight loss.

Figure 5.

Effects of TRP-mCF tumor resection on survival and weight change. Animals were implanted with 5,000 TRP-mCF cells on day 0, and tumors were resected in one third of the animals on day 15 (n = 5/group). (A) Survival curve of control, sham, and resection TRP-mCF mice with median survivals of 27, 26, and 34d, respectively. Analysis of survival using a Cox model demonstrated that resection enhanced median survival. The dotted line corresponds to the day of sham or resection procedures (d15). (B) Normalized (% of day 0) weight of control, sham, and resection mice. The dotted line corresponds to the day of sham or resection procedures (d15). Following tumor resection, mice exhibited initial weight loss compared to control and sham-operated groups, with subsequent weight recovery observed by day 3 post-surgery. (C) Estimated marginal trends (slopes) for weight change and hazard ratios for survival. (D) Analysis of % weight change from day 0 by joint longitudinal and time-to-event model, showing that resection significantly reduced the rate of weight loss.

Figure 6.

Effects of GL261 Red-FLuc tumor resection on survival, weight change, and tumor growth. Animals were implanted with 5,000 GL261 Red-FLuc cells on day 0, and tumors were resected on day 14 (n = 32: control, 21: resection). (A) Representative image of fluorescent tumor tissue pre- and post-resection. (B) Representative in vivo bioluminescence images in J:NU mice intracranially injected with 5,000 GL261 Red-FLuc cells. Resections were conducted 14 days post-implantation, while control mice received no intervention. Total emission range: 2x106 to 2x109 photons/s. (C) Survival curve of control and resection GL261 Red-FLuc mice with median survivals of 27 and 32d, respectively. Survival analysis using the Cox model demonstrated that resection enhanced median survival. The dotted line corresponds to the day of sham or resection procedures (d14). One resection animal was euthanized after 12 weeks due to the absence of recurrent tumor evidence on bioluminescence imaging. (D) Normalized (% of day 0) weight of control and resection mice. The horizontal dotted line corresponds to the day of resection (d14). Analysis of % weight change from day 0 by joint longitudinal and time-to-event model showed that resection significantly reduced the rate of weight loss. (E) Average quantified tumor bioluminescence by week, demonstrating a significant difference in bioluminescence between control and resection mice beginning at week three post-implantation (one-week post-resection). (F) Quantified tumor bioluminescence on day 13 (one day pre-resection) and day 15 (one day post-resection) for resection mice, demonstrating an average resection extent of 91.6% (p < 0.001). Pink corresponds to average values. (G) Evaluation of the impact of extent of resection on survival outcomes.

Figure 6.

Effects of GL261 Red-FLuc tumor resection on survival, weight change, and tumor growth. Animals were implanted with 5,000 GL261 Red-FLuc cells on day 0, and tumors were resected on day 14 (n = 32: control, 21: resection). (A) Representative image of fluorescent tumor tissue pre- and post-resection. (B) Representative in vivo bioluminescence images in J:NU mice intracranially injected with 5,000 GL261 Red-FLuc cells. Resections were conducted 14 days post-implantation, while control mice received no intervention. Total emission range: 2x106 to 2x109 photons/s. (C) Survival curve of control and resection GL261 Red-FLuc mice with median survivals of 27 and 32d, respectively. Survival analysis using the Cox model demonstrated that resection enhanced median survival. The dotted line corresponds to the day of sham or resection procedures (d14). One resection animal was euthanized after 12 weeks due to the absence of recurrent tumor evidence on bioluminescence imaging. (D) Normalized (% of day 0) weight of control and resection mice. The horizontal dotted line corresponds to the day of resection (d14). Analysis of % weight change from day 0 by joint longitudinal and time-to-event model showed that resection significantly reduced the rate of weight loss. (E) Average quantified tumor bioluminescence by week, demonstrating a significant difference in bioluminescence between control and resection mice beginning at week three post-implantation (one-week post-resection). (F) Quantified tumor bioluminescence on day 13 (one day pre-resection) and day 15 (one day post-resection) for resection mice, demonstrating an average resection extent of 91.6% (p < 0.001). Pink corresponds to average values. (G) Evaluation of the impact of extent of resection on survival outcomes.

Table 1.

In vitro fluorescence of GL261 Red-FLuc and TRP-mCF cells with 5-ALA.

Table 1.

In vitro fluorescence of GL261 Red-FLuc and TRP-mCF cells with 5-ALA.

| Effect |

χ2 (df) |

p |

R2

|

| 5-ALA |

326 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.512 |

| Time |

1337 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.268 |

| Cells |

104 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.241 |

| Line |

28 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.085 |

| 5-ALA × Time |

1285 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.131 |

| 5-ALA × Cells |

97 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.117 |

| Time × Cells |

392 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.060 |

| 5-ALA × Line |

35 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.046 |

| Cells × Line |

9 (1) |

0.002 |

0.020 |

| Time × Line |

88 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.018 |

| 5-ALA × Time × Cells |

361 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.029 |

| 5-ALA × Cells × Line |

10 (1) |

0.002 |

0.011 |

| 5-ALA × Time × Line |

93 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.009 |

| Time × Cells × Line |

28 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.005 |

| 5-ALA × Time × Cells × Line |

33 (1) |

< 0.001 |

0.002 |

| Overall |

2282 (15) |

< 0.001 |

0.761 |

Table 2.

Relevant pairwise comparisons of the rate of in vitro fluorescence generation.

Table 2.

Relevant pairwise comparisons of the rate of in vitro fluorescence generation.

| Cells |

5-ALA |

RFU/min |

Cells |

5-ALA |

RFU/min |

t (df) |

p |

| GL261 Red-FLuc |

| 12500 |

0 |

0.001 ± 0.019 |

25000 |

0 |

0.005 ± 0.019 |

0.164 (1448) |

0.869 |

| 12500 |

0 |

0.001 ± 0.019 |

12500 |

1 |

0.276 ± 0.019 |

10.360 (1448) |

< 0.001 |

| 25000 |

0 |

0.005 ± 0.019 |

25000 |

1 |

0.935 ± 0.019 |

35.064 (1448) |

< 0.001 |

| 12500 |

1 |

0.276 ± 0.019 |

25000 |

1 |

0.935 ± 0.019 |

24.868 (1448) |

< 0.001 |

| TRP-mCF |

| 12500 |

0 |

-0.002 ± 0.042 |

25000 |

0 |

0.015 ± 0.042 |

35.064 (1448) |

0.869 |

| 12500 |

0 |

-0.002 ± 0.042 |

12500 |

1 |

0.169 ± 0.042 |

24.868 (1448) |

0.005 |

| 25000 |

0 |

0.015 ± 0.042 |

25000 |

1 |

0.537 ± 0.042 |

9.087 (36192) |

< 0.001 |

| 12500 |

1 |

0.169 ± 0.042 |

25000 |

1 |

0.537 ± 0.042 |

2.605 (36192) |

< 0.001 |

Table 3.

GL261 Red-FLuc tumor resection effects on weight.

Table 3.

GL261 Red-FLuc tumor resection effects on weight.

| Effect |

χ2

|

p |

| Longitudinal Process |

| Day |

111.85 (2) |

< 0.001 |

| Group |

134.43 (2) |

< 0.001 |

| Day × Group |

111.43 (1) |

< 0.001 |

| Event Process |

| Group |

5.48 (1) |

< 0.019 |

| Association |

35.78 (1) |

< 0.001 |

| Omnibus R2

|

|

0.105 |

Table 4.

GL261 Red-FLuc tumor resection effects on bioluminescence.

Table 4.

GL261 Red-FLuc tumor resection effects on bioluminescence.

| Effect |

χ2

|

p |

| Longitudinal Process |

| Day |

154.98 (2) |

< 0.001 |

| Group |

165.29 (2) |

< 0.001 |

| Day × Group |

111.69 (1) |

< 0.001 |

| Event Process |

| Group |

15.04 (1) |

< 0.001 |

| Association |

0.09 (1) |

0.769 |

| Omnibus R2

|

|

0.049 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).