Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Towards Concept of Pan-Pandemic Vaccines

2.1. The Beginning

2.2. The Role of BCG in Modern Vaccination Against Tuberculosis and the Need of an Improved Vaccine

2.3. Lessons from COVID-19 and Heterologous Protection Against Other Pathogens

2.3.1. Heterologous Protection Against Pathogens Induced by BCG

2.3.2. Ambiguity of COVID-19 protection data

2.3.3. Possible Reasons for Ambiguous Data

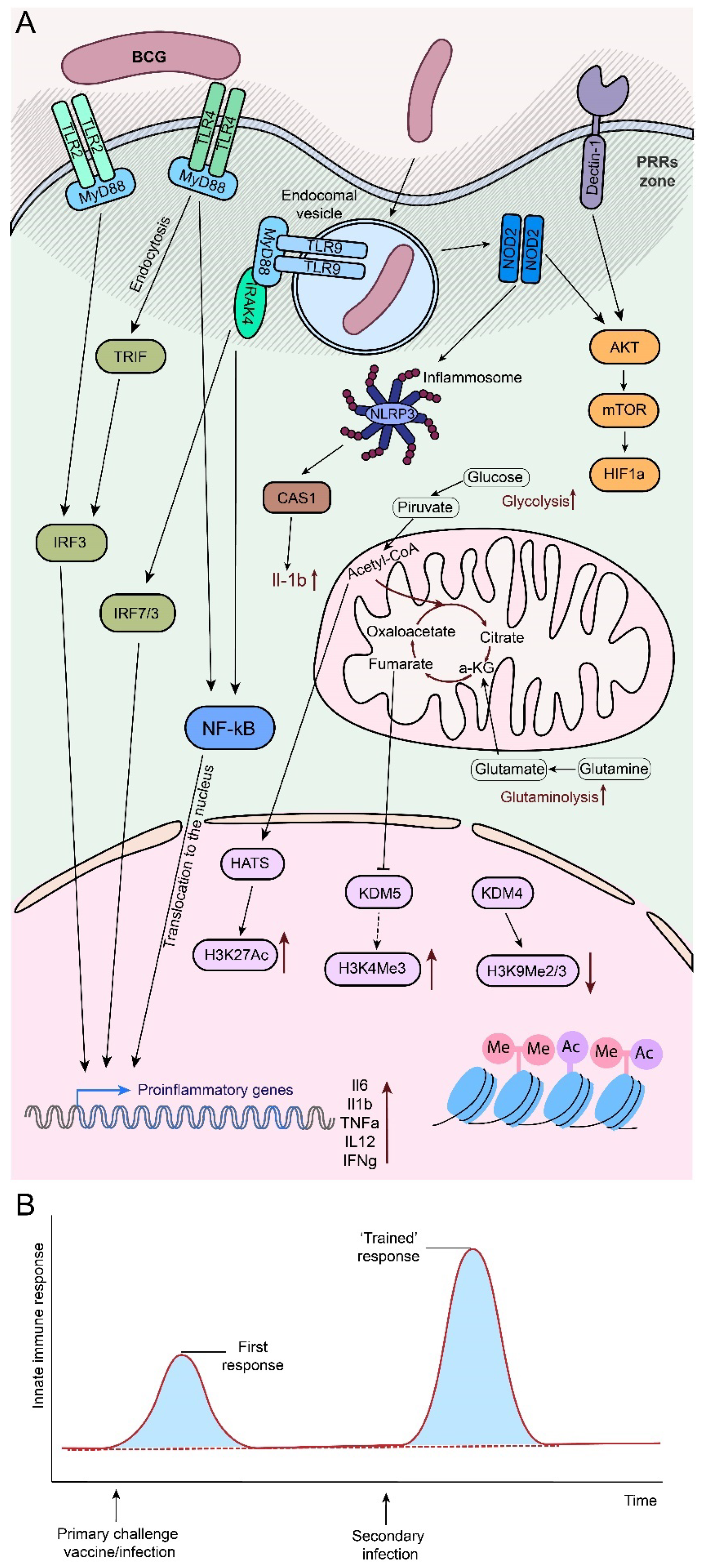

2.4. Trained Immunity and Unspecific Activation of the Immune System after BCG Administration

2.4.1. Impairing the Innate Immunity Training

2.4.2. Persistence of the Innate Immunity

2.4.3. Cells of the Immune System in the Formation of TRIM

2.4.4. Interaction of Adaptive and Innate Immune Systems in the Formation of TRIM

- Primary immune recognition by innate IS cells via PRRs and other “danger signal” receptors triggers activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which interact with naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to bridge the innate and adaptive immune systems [150].

- APCs initiate four critical signals for the induction of the adaptive immune response: 1) engagement of the T/B cell receptor (TCR/BCR) by antigenic peptides on the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), 2) ligation of immune checkpoint molecular pairs (co-stimulation and co-inhibition, e.g., CD80, CD86 and CD40), 3) cytokine stimulation, 4) recognition of “danger signals” by metabolic sensors [150,151,152].

- Activated immune cells undergo metabolic reprogramming characterized by increased glycolysis and decreased oxidative phosphorylation, leading to increased ATP production and pro-inflammatory functions. This metabolic shift is associated with epigenetic changes such as increased acetylation and decreased methylation, which contribute to the pro-inflammatory state [153].

- Metabolic reprogramming results in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [150] and activation of the NF-κB pathway, which enhances the innate immune response and promotes the differentiation of DCs into APCs. In this context, ROS are required for T and B cell activation, differentiation and survival, modulation of T cell subset differentiation, Treg functionality and maintenance of T cell homeostasis. ROS affect the expression of MHC and immune checkpoint molecules on APCs, thereby enhancing T cell activation [150].

- The interplay between APC activation and immune checkpoint responses influences the differentiation of different immune cell subsets [150]: monocytes can differentiate into anti-inflammatory (CD14+CD16- monocytes in humans, CD11b+Ly6C- monocytes in mice, CD14+CD40- monocytes and M2/Mhem macrophages), secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10), leading to tissue repair, and pro-inflammatory (CD14+CD16+ monocytes in humans, CD1b+Ly6C+ monocytes in mice, CD14+CD40+ monocytes, M1 and M4 macrophages), which promote tissue inflammation by producing TNFα, IL-1β, ROS and other inflammatory mediators [154]

- Naïve CD8+ T cells can be activated into cytotoxic T lymphocytes to kill infected and tumor cells. In contrast, naive CD4+ T cells can differentiate into a variety of effector T cells, including proinflammatory Th1/2/9/17/22 subsets, anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells [155].

2.5. The Pan-Pandemic Vaccine Concept

2.6. Reinforcement of Non-Specific BCG Protection

2.6.1. Booster Strategy as an Example

2.6.2. Recombinant BCG

3. Cancer Vaccines

3.1. Highjacking the Innate Immunity

3.2. TRIM in Cancer

3.3. Autophagy Perplexity

3.4. Merging the Antitumor Features of BCG

- Breaking cancer tolerance by inducing an innate immune response leading to theexpansion of the augmented cancer-immunity cycle, which may be at least partially based on:

- TRIM-inducing effect of BCG

- Enhancement of autophagy by specially designed rBCG

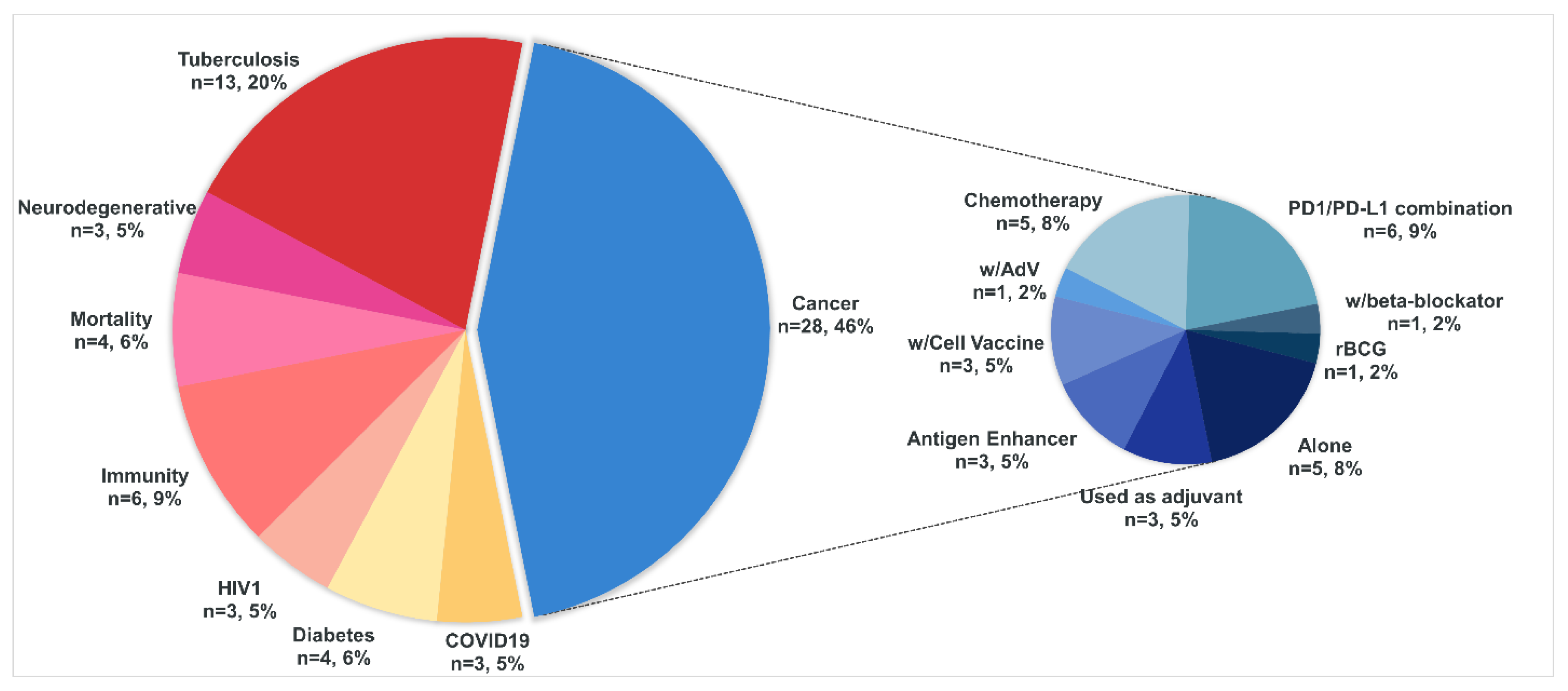

4. A Brief Overview of the Current Clinical Trials That Use BCG

4.1. Cancer

4.2. Tuberculosis

4.3. COVID-19

4.4. Diabetes

4.5. HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

4.6. Immunity

4.7. Mortality

4.8. Neurodegenerative

5. General Considerations

- 1)

-

Driven Improvement (Specific activation of different signaling pathways)rBCG improved with various cytokines may be used to improve immune activation. A particular case of such amplification could be the use of additional effectors in cells with the NOD2 pathway turned off to compensate for it, or similar solutions. However, it is possible that the use of rBCG alone may be insufficient - this conclusion is based on the observation that BCG/rBCG has been shown to be more effective in studies using it in combination with other compounds. However, as a base, such formulations may be more effective than native BCG.

- 2)

-

Adjuvant Empowerment (Unspecific amplification of TRIM)Use of adjuvants to increase the magnitude of non-specific immune response and more stable formation of TRIM (including in a larger number of cells initially). The most straightforward option is the use of alum, which has been successfully used not only in subunit vaccines but also in combination with an inactivated pathogen (see 2.6.1). With particular emphasis on cancer vaccines, a logical evolution of this approach is to replace alum with metallic nanoparticles that can themselves specifically activate TRIM [247,248] and/or have more focused immunomodulatory properties [192].

- 3)

-

Combination:The combined use of rBGC and adjuvants or nanoparticles with specific properties could make a more significant contribution with relatively simple technological solutions. Thus, depending on the development of technologies, in the easiest way adjuvants can be used not only for adsorption of BCG molecules, as in the studies of chapter 2.6.1, but also for covalent binding with biotechnologically synthesized proteins - immune activators, as in the works of the Proff. Wittrup’s group [249,250]. An optional solution could be the use of constitutively modified rBGC, which are limited by a low level of expression of the introduced genes [251], with adjuvants or nanoparticles to enhance the effect.

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2023. 2023.

- World Health, O. BCG vaccine: WHO position paper, February 2018 - Recommendations. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3408–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, S.M.; Rossman, M.D. Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Microbiology spectrum 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauer, J.M.; Moyo, N.; Tay, E.L.; Dale, K.; Ragonnet, R.; McBryde, E.S.; Denholm, J.T. Risk of Active Tuberculosis in the Five Years Following Infection... 15%? Chest 2016, 149, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzeyen, R.; Javid, B. Therapeutic Vaccines for Tuberculosis: An Overview. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 878471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki-Nakashimada, M.A.; Unzueta, A.; Berenise Gamez-Gonzalez, L.; Gonzalez-Saldana, N.; Sorensen, R.U. BCG: a vaccine with multiple faces. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2020, 16, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeki, Y.; Yokoyama, A.; Nishiyama, A.; Yoshida, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Mashima, T.; Tomiyama, C.; Shaban, A.K.; Takeishi, A.; Osada-Oka, M.; et al. Recombinant mycobacterial DNA-binding protein 1 with post-translational modifications boosts IFN-gamma production from BCG-vaccinated individuals’ blood cells in combination with CpG-DNA. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutwama, F.; Kagina, B.M.; Wajja, A.; Waiswa, F.; Mansoor, N.; Kirimunda, S.; Hughes, E.J.; Kiwanuka, N.; Joloba, M.L.; Musoke, P.; et al. Distinct T-cell responses when BCG vaccination is delayed from birth to 6 weeks of age in Ugandan infants. The Journal of infectious diseases 2014, 209, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Cords, O.; Liu, Q.; Acuna-Villaorduna, C.; Bonnet, M.; Fox, G.J.; Carvalho, A.C.C.; Chan, P.C.; Croda, J.; Hill, P.C.; et al. Infant BCG vaccination and risk of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis throughout the life course: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. The Lancet. Global health 2022, 10, e1307–e1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Eisenhut, M.; Harris, R.J.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Sridhar, S.; Habermann, S.; Snell, L.; Mangtani, P.; Adetifa, I.; Lalvani, A.; et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 2014, 349, g4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, P.; Crawford, N.W.; Garcia Croda, M.; Collopy, S.; Araujo Jardim, B.; de Almeida Pinto Jardim, T.; Marshall, H.; Prat-Aymerich, C.; Sawka, A.; Sharma, K.; et al. Safety of BCG vaccination and revaccination in healthcare workers. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2023, 19, 2239088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.; Hill, P.C.; Setiabudiawan, T.P.; Koeken, V.; Alisjahbana, B.; van Crevel, R. BCG-induced protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: Evidence, mechanisms, and implications for next-generation vaccines. Immunological reviews 2021, 301, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, T.; Khatchadourian, C.; Nguyen, H.; Dara, Y.; Jung, S.; Venketaraman, V. A review of the BCG vaccine and other approaches toward tuberculosis eradication. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2021, 17, 2454–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferluga, J.; Yasmin, H.; Al-Ahdal, M.N.; Bhakta, S.; Kishore, U. Natural and trained innate immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunobiology 2020, 225, 151951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Du, G.; Chen, X.; Sun, X. Advancedoral vaccine delivery strategies for improving the immunity. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2021, 177, 113928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, S.; Mihaescu, T. History of BCG Vaccine. Maedica 2013, 8, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, S.; Kumari, A.; Das, G.; Dwivedi, V.P. Tuberculosis vaccine: A journey from BCG to present. Life sciences 2020, 252, 117594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, L.; Cords, O.; Horsburgh, C.R.; Andrews, J.R.; Pediatric, T.B.C.S.C. The risk of tuberculosis in children after close exposure: a systematic review and individual-participant meta-analysis. Lancet 2020, 395, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Xiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Jin, K.; You, L.; Huang, J. The mechanisms and cross-protection of trained innate immunity. Virology journal 2022, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.V.; Vasilov, R.G.; Kondratyeva, L.G.; Kostrov, S.V.; Chernov, I.P.; Sverdlov, E.D. The cellular and epigenetic aspects of trained immunity and prospects for creation of universal vaccines on the eve of more frequent pandemics. Russ J Genet 2023, 59, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensballe, L.G.; Nante, E.; Jensen, I.P.; Kofoed, P.E.; Poulsen, A.; Jensen, H.; Newport, M.; Marchant, A.; Aaby, P. Acute lower respiratory tract infections and respiratory syncytial virus in infants in Guinea-Bissau: a beneficial effect of BCG vaccination for girls community based case-control study. Vaccine 2005, 23, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardhana; Datau, E. A.; Sultana, A.; Mandang, V.V.; Jim, E. The efficacy of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccinations for the prevention of acute upper respiratory tract infection in the elderly. Acta medica Indonesiana 2011, 43, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, A.; Ye, G.; Singh, R.; Afkhami, S.; Bavananthasivam, J.; Luo, X.; Vaseghi-Shanjani, M.; Aleithan, F.; Zganiacz, A.; Jeyanathan, M.; et al. Subcutaneous BCG vaccination protects against streptococcal pneumonia via regulating innate immune responses in the lung. EMBO molecular medicine 2023, 15, e17084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M.; Arts, R.J.W.; van Crevel, R.; Netea, M.G. Non-specific effects of BCG vaccine on viral infections. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2019, 25, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, I.; Bhattacharya, S.; Mishra, V.; Sarkar, T.K.; Chandra, S.; Sil, A.; Pal, S.; Kumar, D.; Saha, A.; Shome, K.; et al. Immunotherapy in viral warts with intradermal Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine versus intradermal tuberculin purified protein derivative: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing effectiveness and safety in a tertiary care center in Eastern India. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology 2017, 83, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Yassen, A.Q.; Al-Maliki, S.K.; Al-Asadi, J.N. The Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Vaccine: Is it a better choice for the treatment of viral warts? Sultan Qaboos University medical journal 2020, 20, e330–e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walk, J.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Graumans, W.; Stoter, R.; van Gemert, G.J.; van de Vegte-Bolmer, M.; Teelen, K.; Hermsen, C.C.; Arts, R.J.W.; Behet, M.C.; et al. Outcomes of controlled human malaria infection after BCG vaccination. Nature communications 2019, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.J.W.; Moorlag, S.; Novakovic, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Oosting, M.; Kumar, V.; Xavier, R.J.; Wijmenga, C.; Joosten, L.A.B.; et al. BCG Vaccination Protects against Experimental Viral Infection in Humans through the Induction of Cytokines Associated with Trained Immunity. Cell host & microbe 2018, 23, 89–100 e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.J.; Netea, M.G. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nature reviews. Immunology 2020, 20, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, L.E.; Molina-Cruz, A.; Barillas-Mury, C. BCG vaccine protection from severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 17720–17726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M.; van Deuren, R.C.; van Werkhoven, C.H.; Jaeger, M.; Debisarun, P.; Taks, E.; Mourits, V.P.; Koeken, V.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Ten Doesschate, T.; et al. Safety and COVID-19 Symptoms in Individuals Recently Vaccinated with BCG: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Cell reports. Medicine 2020, 1, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, M.K.; Yu, Q.; Salvador, C.E.; Melani, I.; Kitayama, S. Mandated Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination predicts flattened curves for the spread of COVID-19. Science advances 2020, 6, eabc1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, M.N.; Ebinger, J.E.; Wu, M.; Sun, N.; Braun, J.; Sobhani, K.; Van Eyk, J.E.; Cheng, S.; Arditi, M. BCG vaccination history associates with decreased SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence across a diverse cohort of health care workers. The Journal of clinical investigation 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaby, P.; Benn, C.S.; Flanagan, K.L.; Klein, S.L.; Kollmann, T.R.; Lynn, D.J.; Shann, F. The non-specific and sex-differential effects of vaccines. Nature reviews. Immunology 2020, 20, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Liu, Q.; Tang, D.; He, J.Q. Efficacy of BCG Vaccination against COVID-19: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of clinical medicine 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, C.M.; van Wijk, R.C.; Mockeliunas, L.; Simonsson, U.S.H.; McHarry, K.; van den Hoogen, G.; Muller, C.; von Delft, A.; van der Westhuizen, H.M.; van Crevel, R.; et al. Safety and efficacy of BCG re-vaccination in relation to COVID-19 morbidity in healthcare workers: A double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 48, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, J.; Ten Doesschate, T.; Gumbs, C.; van Werkhoven, C.H.; van der Vaart, T.W.; Janssen, A.B.; Smits, G.; van Binnendijk, R.; van der Klis, F.; van Baarle, D.; et al. BCG Vaccination of Health Care Workers Does Not Reduce SARS-CoV-2 Infections nor Infection Severity or Duration: a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. mBio 2023, 14, e0035623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Du, J. Excluding Participants With Mycobacteria Infections From Clinical Trials: A Critical Consideration in Evaluating the Efficacy of BCG Against COVID-19. Journal of Korean medical science 2023, 38, e343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilho, A.I.; De Gaspari, E. Trained-immunity and cross-reactivity for protection: insights from the coronavirus disease 2019 and monkeypox emergencies for vaccine development. Explor Immunol 2023, 3, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilika, M.; Taks, E.; Dolianitis, K.; Kotsaki, A.; Leventogiannis, K.; Damoulari, C.; Kostoula, M.; Paneta, M.; Adamis, G.; Papanikolaou, I.; et al. ACTIVATE-2: A Double-Blind Randomized Trial of BCG Vaccination Against COVID-19 in Individuals at Risk. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 873067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhtreiber, W.M.; Hostetter, E.R.; Wolfe, G.E.; Vaishnaw, M.S.; Goldstein, R.; Bulczynski, E.R.; Hullavarad, N.S.; Braley, J.E.; Zheng, H.; Faustman, D.L. Late in the US pandemic, multi-dose BCG vaccines protect against COVID-19 and infectious diseases. iScience 2024, 27, 109881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ru, H.W.; Chen, F.Z.; Jin, C.Y.; Sun, R.F.; Fan, X.Y.; Guo, M.; Mai, J.T.; Xu, W.X.; Lin, Q.X.; et al. Variable Virulence and Efficacy of BCG Vaccine Strains in Mice and Correlation With Genome Polymorphisms. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2016, 24, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, G.; Debisarun, P.A.; Alaswad, A.; Baltissen, M.P.; Lamers, L.A.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Benn, C.S.; Aaby, P.; Dijkstra, H.; Lemmers, H.; et al. Seasonal variation in BCG-induced trained immunity. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirlak, L.; Haddad, R.; Hardy, J.D.; Khaled, N.S.; Chung, M.H.; Amirlak, B. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing Covid-19 infection. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2021, 17, 3913–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuscan, P.; Kischkel, B.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G. Trained immunity: General and emerging concepts. Immunological reviews 2024, 323, 164–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothfuchs, A.G.; Bafica, A.; Feng, C.G.; Egen, J.G.; Williams, D.L.; Brown, G.D.; Sher, A. Dectin-1 interaction with Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to enhanced IL-12p40 production by splenic dendritic cells. Journal of immunology 2007, 179, 3463–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.; Ifrim, D.C.; Saeed, S.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; de Jong, D.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109, 17537–17542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisiaux, A.; Boussier, J.; Duffy, D.; Quintana-Murci, L.; Fontes, M.; Albert, M.L.; Milieu Interieur, C. Deconvolution of the Response to Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Reveals NF-kappaB-Induced Cytokines As Autocrine Mediators of Innate Immunity. Frontiers in immunology 2017, 8, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydemir, I.; Dulfer, E.A.; Netea, M.G.; Dominguez-Andres, J. Trained immunity-inducing vaccines: Harnessing innate memory for vaccine design and delivery. Clinical immunology 2024, 261, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Madsen, J.C.; Netea, M.G.; Duivenvoorden, R. Trained immunity - basic concepts and contributions to immunopathology. Nature reviews. Nephrology 2023, 19, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nabhani, Z.; Dietrich, G.; Hugot, J.P.; Barreau, F. Nod2: The intestinal gate keeper. PLoS pathogens 2017, 13, e1006177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchese, J.M.; Evans, S.; Hult, C.; Joslyn, L.R.; Wessler, T.; Millar, J.A.; Marino, S.; Cilfone, N.A.; Mattila, J.T.; Linderman, J.J.; et al. Dynamic balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals controls disease and limits pathology. Immunological reviews 2018, 285, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M.; Folkman, L.; Ter Horst, R.; Krausgruber, T.; Barreca, D.; Schuster, L.C.; Fife, V.; Matzaraki, V.; Li, W.; Reichl, S.; et al. Multi-omics analysis of innate and adaptive responses to BCG vaccination reveals epigenetic cell states that predict trained immunity. Immunity 2024, 57, 171–187 e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhong, Z.; Karin, M. NF-kappaB: A Double-Edged Sword Controlling Inflammation. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.A.; Sousa, L.P.; Pinho, V.; Perretti, M.; Teixeira, M.M. Resolution of Inflammation: What Controls Its Onset? Frontiers in immunology 2016, 7, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, N.; Zhang, G.X.; Esmaeil, N.; Rostami, A. Evaluation of the effect of GM-CSF blocking on the phenotype and function of human monocytes. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A.T.; Ostenson, C.L.; Giordano, D.; Beavo, J.A. Differentiation of human monocytes in vitro with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and macrophage colony-stimulating factor produces distinct changes in cGMP phosphodiesterase expression. Cellular signalling 2004, 16, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushach, I.; Zlotnik, A. Biological role of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) on cells of the myeloid lineage. Journal of leukocyte biology 2016, 100, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.; Kuzmich, A.; Kondratyeva, L.; Kondratieva, S.; Pleshkan, V.; Sverdlov, E. Step-by-Step Immune Activation for Suicide Gene Therapy Reinforcement. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Taghi Khani, A.; Sanchez Ortiz, A.; Swaminathan, S. GM-CSF: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer Immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 901277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, E.K. The role of sargramostim (rhGM-CSF) as immunotherapy. The oncologist 2007, 12 Suppl 2, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.K.; Koh, C.H.; Jeon, I.; Shin, K.S.; Kang, T.S.; Bae, E.A.; Seo, H.; Ko, H.J.; Kim, B.S.; Chung, Y.; et al. GM-CSF Promotes Antitumor Immunity by Inducing Th9 Cell Responses. Cancer immunology research 2019, 7, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaseen, M.M.; Abuharfeil, N.M.; Darmani, H. The role of IL-1beta during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Reviews in medical virology 2023, 33, e2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, L.; Hoffman, H.M. IL-1 and autoinflammatory disease: biology, pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting. Nature reviews. Rheumatology 2022, 18, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, A.; Wasiliew, P.; Kracht, M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Science signaling 2010, 3, cm1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, R.; Moll, L.; Grabbe, S.; Bros, M. Interleukin-1 Beta-A Friend or Foe in Malignancies? International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarreberg, L.D.; Esser-Nobis, K.; Driscoll, C.; Shuvarikov, A.; Roby, J.A.; Gale, M., Jr. Interleukin-1beta Induces mtDNA Release to Activate Innate Immune Signaling via cGAS-STING. Molecular cell 2019, 74, 801–815 e806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A. Cancer: an infernal triangle. Nature 2007, 448, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebe, C.; Ghiringhelli, F. Interleukin-1beta and Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkova, A.M.; Gubal, A.R.; Petrova, A.L.; Voronov, E.; Apte, R.N.; Semenov, K.N.; Sharoyko, V.V. Pathogenetic role and clinical significance of interleukin-1beta in cancer. Immunology 2023, 168, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ottewell, P.D. The role of IL-1B in breast cancer bone metastasis. Journal of bone oncology 2024, 46, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplanov, I.; Carmi, Y.; Kornetsky, R.; Shemesh, A.; Shurin, G.V.; Shurin, M.R.; Dinarello, C.A.; Voronov, E.; Apte, R.N. Blocking IL-1beta reverses the immunosuppression in mouse breast cancer and synergizes with anti-PD-1 for tumor abrogation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2019, 116, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platanias, L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nature reviews. Immunology 2005, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonjardim, C.A. Interferons (IFNs) are key cytokines in both innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses--and viruses counteract IFN action. Microbes and infection 2005, 7, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertowska, P.; Smolak, K.; Mertowski, S.; Grywalska, E. Immunomodulatory Role of Interferons in Viral and Bacterial Infections. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannikou, M.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Signaling by Type I Interferons in Immune Cells: Disease Consequences. Cancers 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldszmid, R.S.; Caspar, P.; Rivollier, A.; White, S.; Dzutsev, A.; Hieny, S.; Kelsall, B.; Trinchieri, G.; Sher, A. NK cell-derived interferon-gamma orchestrates cellular dynamics and the differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells at the site of infection. Immunity 2012, 36, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, D.F. Modulation of T-cell function by type I interferon. Immunology and cell biology 2012, 90, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.P.; Farrar, J.D. Regulation of effector and memory T-cell functions by type I interferon. Immunology 2011, 132, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuka, M.; De Giovanni, M.; Iannacone, M. The role of type I interferons in CD4(+) T cell differentiation. Immunology letters 2019, 215, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sun, W.; Dai, T.; Wang, A.; Wu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; et al. A Dual Role of Type I Interferons in Antitumor Immunity. Advanced biosystems 2020, 4, e1900237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, X. Double-edged effects of interferons on the regulation of cancer-immunity cycle. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1929005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolvahab, M.H.; Darvishi, B.; Zarei, M.; Majidzadeh, A.K.; Farahmand, L. Interferons: role in cancer therapy. Immunotherapy 2020, 12, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-gamma in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomarker research 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, S.; Yue, D.; Maimela, N.R.; Qu, J.; et al. Low-Dose IFNgamma Induces Tumor Cell Stemness in Tumor Microenvironment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer research 2019, 79, 3737–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beziaud, L.; Young, C.M.; Alonso, A.M.; Norkin, M.; Minafra, A.R.; Huelsken, J. IFNgamma-induced stem-like state of cancer cells as a driver of metastatic progression following immunotherapy. Cell stem cell 2023, 30, 818–831 e816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, U.G.; Pong, R.C.; Yang, D.; Gandee, L.; Hernandez, E.; Dang, A.; Lin, C.J.; Santoyo, J.; Ma, S.; Sonavane, R.; et al. IFNgamma-Induced IFIT5 Promotes Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Prostate Cancer via miRNA Processing. Cancer research 2019, 79, 1098–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalper, K.A.; Carvajal-Hausdorf, D.; McLaughlin, J.; Altan, M.; Velcheti, V.; Gaule, P.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Chen, L.; Herbst, R.S.; Rimm, D.L. Differential Expression and Significance of PD-L1, IDO-1, and B7-H4 in Human Lung Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2017, 23, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.I.; Lee, A.H.; Shin, H.Y.; Song, H.R.; Park, J.H.; Kang, T.B.; Lee, S.R.; Yang, S.H. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-alpha) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-alpha Inhibitors in Therapeutics. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, G.; Bertrand, M.J.M. Death by TNF: a road to inflammation. Nature reviews. Immunology 2023, 23, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, D.; Grant, R.; Mishra, P.; Nilubol, N. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor in Manipulating the Immunological Response of Tumor Microenvironment. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 656908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deventer, S.J. Transmembrane TNF-alpha, induction of apoptosis, and the efficacy of TNF-targeting therapies in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2001, 121, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraj, S.S.; Jalal, P.J. IL1beta, IL-6, and TNF-alpha cytokines cooperate to modulate a complicated medical condition among COVID-19 patients: case-control study. Annals of medicine and surgery 2023, 85, 2291–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, B.; Fernandez, M.C.; D’Costa, Z.; Brodt, P. The diverse roles of the TNF axis in cancer progression and metastasis. Trends in cancer research 2016, 11, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, L.F.; Keane, C.; Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, F. Molecular mechanisms of tumour necrosis factor signalling via TNF receptor 1 and TNF receptor 2 in the tumour microenvironment. Current opinion in immunology 2024, 86, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.P. TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB/Snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. British journal of cancer 2010, 102, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Tao, D.; Fang, Y.; Deng, C.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, J. TNF-Alpha Promotes Invasion and Metastasis via NF-Kappa B Pathway in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Medical science monitor basic research 2017, 23, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.R.; Kang, S.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Hong, S.C.; Kim, E.C. TNF-alpha and LPS activate angiogenesis via VEGF and SIRT1 signalling in human dental pulp cells. International endodontic journal 2015, 48, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2014, 6, a016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienz, O.; Eaton, S.M.; Bond, J.P.; Neveu, W.; Moquin, D.; Noubade, R.; Briso, E.M.; Charland, C.; Leonard, W.J.; Ciliberto, G.; et al. The induction of antibody production by IL-6 is indirectly mediated by IL-21 produced by CD4+ T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine 2009, 206, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jones, L.L.; Geiger, T.L. IL-6 Promotes T Cell Proliferation and Expansion under Inflammatory Conditions in Association with Low-Level RORgammat Expression. Journal of immunology 2018, 201, 2934–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, D.N.; Pathak, A.; Agrawal, A. IL-6 regulates induction of C-reactive protein gene expression by activating STAT3 isoforms. Molecular immunology 2022, 146, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, R.; Li, H.; Cai, S.; Liang, Z.; Shan, W.; Wang, B.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, W.; Huang, H. Interleukin-6 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Experimental & molecular medicine 2019, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Ren, H.C.; Cao, J.H. Roles of Interleukin-6-mediated immunometabolic reprogramming in COVID-19 and other viral infection-associated diseases. International immunopharmacology 2022, 110, 109005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D.T.; Appenheimer, M.M.; Evans, S.S. The two faces of IL-6 in the tumor microenvironment. Seminars in immunology 2014, 26, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskova, M.; Lacina, L.; Kejik, Z.; Venhauerova, A.; Skalickova, M.; Kolar, M.; Jakubek, M.; Rosel, D.; Smetana, K., Jr.; Brabek, J. The Role of IL-6 in Cancer Cell Invasiveness and Metastasis-Overview and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhu, G.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Hua, J.; Yang, S.; Zhuang, J.; Ye, J. IL-6 mediates the signal pathway of JAK-STAT3-VEGF-C promoting growth, invasion and lymphangiogenesis in gastric cancer. Oncology reports 2016, 35, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bent, E.H.; Millan-Barea, L.R.; Zhuang, I.; Goulet, D.R.; Frose, J.; Hemann, M.T. Microenvironmental IL-6 inhibits anti-cancer immune responses generated by cytotoxic chemotherapy. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.W.; Wang, D.; Cai, H.; Cao, M.Q.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhuang, P.Y.; Shen, J. IL-6 plays a crucial role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and pro-metastasis induced by sorafenib in liver cancer. Oncology reports 2021, 45, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkens, M.J.; Shedlock, D.J.; Jung, E.; Troy, A.; Pearce, E.L.; Shen, H.; Pearce, E.J. Th1 and Th2 cells help CD8 T-cell responses. Infection and immunity 2007, 75, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraille, E.; Leo, O.; Moser, M. TH1/TH2 paradigm extended: macrophage polarization as an unappreciated pathogen-driven escape mechanism? Frontiers in immunology 2014, 5, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, F.H.N.; Kwan, A.; Winder, N.; Mughal, A.; Collado-Rojas, C.; Muthana, M. Understanding Immune Responses to Viruses-Do Underlying Th1/Th2 Cell Biases Predict Outcome? Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, M.A.; Lee, W.T.; Sanders, V.M. IFN-gamma production by Th1 cells generated from naive CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. Journal of immunology 2001, 166, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, K.; Saio, M.; Umemura, N.; Kikuchi, A.; Takahashi, T.; Osada, S.; Yoshida, K. Th1 polarization in the tumor microenvironment upregulates the myeloid-derived suppressor-like function of macrophages. Cellular immunology 2021, 369, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lozano-Ruiz, B.; Yang, F.M.; Fan, D.D.; Shen, L.; Gonzalez-Navajas, J.M. The Multifaceted Role of Th1, Th9, and Th17 Cells in Immune Checkpoint Inhibition Therapy. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 625667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Yang, B.; Zhang, F.; Guo, X. Acetate promotes SNAI1 expression by ACSS2-mediated histone acetylation under glucose limitation in renal cell carcinoma cell. Bioscience reports 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Villa, M.; Sanin, D.E.; Buck, M.D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Ching, R.; Matsushita, M.; Grzes, K.M.; Winkler, F.; Chang, C.H.; et al. Acetate Promotes T Cell Effector Function during Glucose Restriction. Cell reports 2019, 27, 2063–2074 e2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lv, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, R.; Li, F. Fatty acid metabolism of immune cells: a new target of tumour immunotherapy. Cell death discovery 2024, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, N.; Bo, L.; Zha, Y.; Bian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, X. Acetate attenuates inflammasome activation through GPR43-mediated Ca(2+)-dependent NLRP3 ubiquitination. Experimental & molecular medicine 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; O’Connor, S.; Pniewski, K.A.; Kannan, T.; Acosta, R.; Mirji, G.; Papp, S.; Hulse, M.; Mukha, D.; Hlavaty, S.I.; et al. Acetate acts as a metabolic immunomodulator by bolstering T-cell effector function and potentiating antitumor immunity in breast cancer. Nature cancer 2023, 4, 1491–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guertin, D.A.; Wellen, K.E. Acetyl-CoA metabolism in cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer 2023, 23, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godkowicz, M.; Druszczynska, M. NOD1, NOD2, and NLRC5 Receptors in Antiviral and Antimycobacterial Immunity. Vaccines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Qin, X.; Li, B.; Han, Y. NOD2 deficiency confers a pro-tumorigenic macrophage phenotype to promote lung adenocarcinoma progression. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2021, 25, 7545–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Becker, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Advances in nutrition 2018, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, S.; Zang, D.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. Butyrate as a promising therapeutic target in cancer: From pathogenesis to clinic (Review). International journal of oncology 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcarcel-Jimenez, L.; Frezza, C. Fumarate hydratase (FH) and cancer: a paradigm of oncometabolism. British journal of cancer 2023, 129, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, C.M.; Mandler, M.D.; Lunger, J.C.; Chan, D.; Maligireddy, S.S.; Schmiechen, A.C.; Gamage, S.T.; Link, C.; Jenkins, L.M.; Chan, K.; et al. Rewiring of RNA methylation by the oncometabolite fumarate in renal cell carcinoma. NAR cancer 2024, 6, zcae004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Soga, T.; Pollard, P.J.; Adam, J. The emerging role of fumarate as an oncometabolite. Frontiers in oncology 2012, 2, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegotek, A.; Skrzydlewska, E. Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ascorbic Acid. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.C.; Quintin, J.; Cramer, R.A.; Shepardson, K.M.; Saeed, S.; Kumar, V.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Martens, J.H.; Rao, N.A.; Aghajanirefah, A.; et al. mTOR- and HIF-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science 2014, 345, 1250684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intravenous Vitamin C (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version. In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; Bethesda (MD), 2002.

- Gonzalez-Montero, J.; Chichiarelli, S.; Eufemi, M.; Altieri, F.; Saso, L.; Rodrigo, R. Ascorbate as a Bioactive Compound in Cancer Therapy: The Old Classic Strikes Back. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Liao, Y.; Na, J.; Wu, L.; Yin, Y.; Mi, Z.; Fang, S.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y. The Involvement of Ascorbic Acid in Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, H.A.; Sanusi, T.; Saldanha, G.; Brown, K.; Cooke, M.S.; Jones, G.D. Redox modulation of oxidatively-induced DNA damage by ascorbate enhances both in vitro and ex-vivo DNA damage formation and cell death in melanoma cells. Free radical biology & medicine 2024, 213, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, T.; Miyake, T.; Tani, M.; Uemoto, S. Diverse antitumor effects of ascorbic acid on cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in oncology 2022, 12, 981547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Frias, M.A.; Chatterjee, A.; Yellen, P.; Foster, D.A. The Enigma of Rapamycin Dosage. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2016, 15, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Cancer prevention with rapamycin. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repas, J.; Zupin, M.; Vodlan, M.; Veranic, P.; Gole, B.; Potocnik, U.; Pavlin, M. Dual Effect of Combined Metformin and 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose Treatment on Mitochondrial Biogenesis and PD-L1 Expression in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Cancers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroulis, I.; Ruppova, K.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.S.; Grzybek, M.; Grinenko, T.; Eugster, A.; Troullinaki, M.; Palladini, A.; Kourtzelis, I.; et al. Modulation of Myelopoiesis Progenitors Is an Integral Component of Trained Immunity. Cell 2018, 172, 147–161 e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, E.; Sanz, J.; Dunn, J.L.; Khan, N.; Mendonca, L.E.; Pacis, A.; Tzelepis, F.; Pernet, E.; Dumaine, A.; Grenier, J.C.; et al. BCG Educates Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Generate Protective Innate Immunity against Tuberculosis. Cell 2018, 172, 176–190 e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirovic, B.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Groh, L.; Blok, B.A.; Chan, J.; van der Velden, W.; Bremmers, M.E.J.; van Crevel, R.; Handler, K.; Picelli, S.; et al. BCG Vaccination in Humans Elicits Trained Immunity via the Hematopoietic Progenitor Compartment. Cell host & microbe 2020, 28, 322–334 e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jeyanathan, M.; Haddadi, S.; Barra, N.G.; Vaseghi-Shanjani, M.; Damjanovic, D.; Lai, R.; Afkhami, S.; Chen, Y.; Dvorkin-Gheva, A.; et al. Induction of Autonomous Memory Alveolar Macrophages Requires T Cell Help and Is Critical to Trained Immunity. Cell 2018, 175, 1634–1650 e1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.; Jacobs, C.; Xavier, R.J.; van der Meer, J.W.; van Crevel, R.; Netea, M.G. BCG-induced trained immunity in NK cells: Role for non-specific protection to infection. Clinical immunology 2014, 155, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintin, J.; Saeed, S.; Martens, J.H.A.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Ifrim, D.C.; Logie, C.; Jacobs, L.; Jansen, T.; Kullberg, B.J.; Wijmenga, C.; et al. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell host & microbe 2012, 12, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, C.T.; Mariuzza, R.A.; Brenner, M.B. Antigen recognition by human gamma delta T cells: pattern recognition by the adaptive immune system. Springer seminars in immunopathology 2000, 22, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Pizarro, J.C.; Holmes, M.A.; McBeth, C.; Groh, V.; Spies, T.; Strong, R.K. Crystal structure of a gammadelta T-cell receptor specific for the human MHC class I homolog MICA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011, 108, 2414–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmeier, W.; Kabelitz, D. gammadelta T cells link innate and adaptive immune responses. Chemical immunology and allergy 2005, 86, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, T.K.; Moorlag, S.; Li, W.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Koeken, V.; Mourits, V.P.; Dijkstra, H.; Lemmers, H.; Bhat, J.; Xu, C.J.; et al. BCG vaccination induces innate immune memory in gammadelta T cells in humans. Journal of leukocyte biology 2024, 115, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Saredy, J.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Innate-adaptive immunity interplay and redox regulation in immune response. Redox biology 2020, 37, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Pasare, C. Innate Control of Adaptive Immunity: Beyond the Three-Signal Paradigm. Journal of immunology 2017, 198, 3791–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nature immunology 2015, 16, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, H. Metabolic Reprogramming in Immune Response and Tissue Inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2020, 40, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, C.; Yang, X.F.; Wang, H. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomarker research 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, P.; Li, X.; Dai, J.; Cole, L.; Camacho, J.A.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.F.; Wang, H. Immune cell subset differentiation and tissue inflammation. Journal of hematology & oncology 2018, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulendran, B. Integrated organ immunity: a path to a universal vaccine. Nature reviews. Immunology 2024, 24, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Floyd, K.; Wu, S.; Fang, Z.; Tan, T.K.; Froggatt, H.M.; Powers, J.M.; Leist, S.R.; Gully, K.L.; Hubbard, M.L.; et al. BCG vaccination stimulates integrated organ immunity by feedback of the adaptive immune response to imprint prolonged innate antiviral resistance. Nature immunology 2024, 25, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zou, Y.; Hu, Z. Advances in aluminum hydroxide-based adjuvant research and its mechanism. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2015, 11, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaelen, K. Vaccine Strategies to Improve Anti-cancer Cellular Immune Responses. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Scott, M.K.D.; Wimmers, F.; Arunachalam, P.S.; Luo, W.; Fox, C.B.; Tomai, M.; Khatri, P.; Pulendran, B. A molecular atlas of innate immunity to adjuvanted and live attenuated vaccines, in mice. Nature communications 2022, 13, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, S.; Matzinger, P. Danger signals: SOS to the immune system. Current opinion in immunology 2001, 13, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, N.; Sabroe, I. Basic science of the innate immune system and the lung. Paediatric respiratory reviews 2008, 9, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annual review of immunology 1994, 12, 991–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulendran, B.; P, S.A.; O’Hagan, D.T. Emerging concepts in the science of vaccine adjuvants. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2021, 20, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamil, A.A.; Khalil, E.A.; Musa, A.M.; Modabber, F.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Zijlstra, E.E.; Sacks, D.; Smith, P.G.; Zicker, F.; et al. Alum-precipitated autoclaved Leishmania major plus bacille Calmette-Guerrin, a candidate vaccine for visceral leishmaniasis: safety, skin-delayed type hypersensitivity response and dose finding in healthy volunteers. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2003, 97, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, E.A.; Musa, A.M.; Modabber, F.; El-Hassan, A.M. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate vaccine for visceral leishmaniasis (Alum-precipitated autoclaved Leishmania major + BCG) in children: an extended phase II study. Annals of tropical paediatrics 2006, 26, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutiso, J.M.; Macharia, J.C.; Gicheru, M.M. Immunization with Leishmania vaccine-alum-BCG and montanide ISA 720 adjuvants induces low-grade type 2 cytokines and high levels of IgG2 subclass antibodies in the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops) model. Scandinavian journal of immunology 2012, 76, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvapandiyan, A.; Puri, N.; Reyaz, E.; Beg, M.A.; Salotra, P.; Nakhasi, H.L.; Ganguly, N.K. Worldwide Efforts for the Prevention of Visceral Leishmaniasis Using Vaccinations. In Challenges and Solutions Against Visceral Leishmaniasis, Selvapandiyan, A., Singh, R., Puri, N., Ganguly, N.K., Ed.; Springer, Singapore: 2024.

- Ayala, A.; Llanes, A.; Lleonart, R.; Restrepo, C.M. Advances in Leishmania Vaccines: Current Development and Future Prospects. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Mohebali, M.; Khamesipour, A.; Bahrami, F.; Darabi, H.; Khaze, V.; Riazi-Rad, F.; Habibi, G.; Ajdary, S.; Alimohammadian, M.H. Evaluation of Cellular Immune Responses in Dogs Immunized with Alum-Precipitated Autoclaved Leishmania major along with BCG and Imiquimod. Iranian journal of parasitology 2021, 16, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuizen, N.E.; Kaufmann, S.H.E. Next-Generation Vaccines Based on Bacille Calmette-Guerin. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.A.; Spratt, J.M.; Britton, W.J.; Triccas, J.A. Secretion of functional monocyte chemotactic protein 3 by recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG attenuates vaccine virulence and maintains protective efficacy against M. tuberculosis infection. Infection and immunity 2007, 75, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, W.; Scott, H.M.; Chambers, H.F.; Flynn, J.L.; Charo, I.F.; Ernst, J.D. Chemokine receptor 2 serves an early and essential role in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001, 98, 7958–7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, A.A.; Wozniak, T.M.; Shklovskaya, E.; O’Donnell, M.A.; Fazekas de St Groth, B.; Britton, W.J.; Triccas, J.A. Improved protection against disseminated tuberculosis by Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin secreting murine GM-CSF is associated with expansion and activation of APCs. Journal of immunology 2007, 179, 8418–8424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, A.A.; Nambiar, J.K.; Wozniak, T.M.; Roediger, B.; Shklovskaya, E.; Britton, W.J.; Fazekas de St Groth, B.; Triccas, J.A. Antigen load governs the differential priming of CD8 T cells in response to the bacille Calmette Guerin vaccine or Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Journal of immunology 2009, 182, 7172–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, J.K.; Ryan, A.A.; Kong, C.U.; Britton, W.J.; Triccas, J.A. Modulation of pulmonary DC function by vaccine-encoded GM-CSF enhances protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. European journal of immunology 2010, 40, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covian, C.; Fernandez-Fierro, A.; Retamal-Diaz, A.; Diaz, F.E.; Vasquez, A.E.; Lay, M.K.; Riedel, C.A.; Gonzalez, P.A.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. BCG-Induced Cross-Protection and Development of Trained Immunity: Implication for Vaccine Design. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, I.P.; Dias, W.O.; Quintilio, W.; Christ, A.P.; Moraes, J.F.; Vancetto, M.D.; Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, G.; Raw, I.; Leite, L.C. Neonatal immunization with a single dose of recombinant BCG expressing subunit S1 from pertussis toxin induces complete protection against Bordetella pertussis intracerebral challenge. Microbes and infection 2008, 10, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, A.I.; Boraschi, D.; Leite, L.C.C.; Rodriguez, D. Recombinant BCG Expressing the Subunit 1 of Pertussis Toxin Induces Innate Immune Memory and Confers Protection against Non-Related Pathogens. Vaccines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.S.; Peacock, J.W.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Frothingham, R.; Letvin, N.L.; Liao, H.X.; Haynes, B.F. Recombinant Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin elicits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-specific T lymphocytes at mucosal sites. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI 2007, 14, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.; Stutz, H.; Jacobs, W., Jr.; Shephard, E.; Williamson, A.L. Priming with recombinant auxotrophic BCG expressing HIV-1 Gag, RT and Gp120 and boosting with recombinant MVA induces a robust T cell response in mice. PloS one 2013, 8, e71601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, M.K.; Cespedes, P.F.; Palavecino, C.E.; Leon, M.A.; Diaz, R.A.; Salazar, F.J.; Mendez, G.P.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Human metapneumovirus infection activates the TSLP pathway that drives excessive pulmonary inflammation and viral replication in mice. European journal of immunology 2015, 45, 1680–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palavecino, C.E.; Cespedes, P.F.; Gomez, R.S.; Kalergis, A.M.; Bueno, S.M. Immunization with a recombinant bacillus Calmette-Guerin strain confers protective Th1 immunity against the human metapneumovirus. Journal of immunology 2014, 192, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.A.; Galvez, N.M.S.; Pacheco, G.A.; Canedo-Marroquin, G.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Induction of Protective Immunity by a Single Low Dose of a Master Cell Bank cGMP-rBCG-P Vaccine Against the Human Metapneumovirus in Mice. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2021, 11, 662714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, P.F.; Rey-Jurado, E.; Espinoza, J.A.; Rivera, C.A.; Canedo-Marroquin, G.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. A single, low dose of a cGMP recombinant BCG vaccine elicits protective T cell immunity against the human respiratory syncytial virus infection and prevents lung pathology in mice. Vaccine 2017, 35, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Luo, T.; Sun, C.; Yuan, J.; Peng, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, X.; Bao, L. PPE27 in Mycobacterium smegmatis Enhances Mycobacterial Survival and Manipulates Cytokine Secretion in Mouse Macrophages. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research 2017, 37, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liang, X.; Feng, J.; Huang, Y.; Weng, S.; Xu, Y.; Su, H. Mucosal recombinant BCG vaccine induces lung-resident memory macrophages and enhances trained immunity via mTORC2/HK1-mediated metabolic rewiring. The Journal of biological chemistry 2024, 300, 105518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.C.; de Magalhaes, M.T.Q.; Homan, E.J. Immunoinformatic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Identification of COVID-19 Vaccine Targets. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 587615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambelli, F.; Marinho, F.V.; Andrade, J.M.; de Araujo, A.; Abuna, R.P.F.; Fabri, V.M.R.; Santos, B.P.O.; da Silva, J.S.; de Magalhaes, M.T.Q.; Homan, E.J.; et al. Recombinant Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Expressing SARS-CoV-2 Chimeric Protein Protects K18-hACE2 Mice against Viral Challenge. Journal of immunology 2023, 210, 1925–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Mei, Q.; Zhao, B.; Chu, Q.; Dai, Z.; Wu, K. Exploiting innate immunity for cancer immunotherapy. Molecular cancer 2023, 22, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naletova, I.; Tomasello, B.; Attanasio, F.; Pleshkan, V.V. Prospects for the Use of Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Adjuvants for Local Cancer Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Old, L.J.; Clarke, D.A.; Benacerraf, B. Effect of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin infection on transplanted tumours in the mouse. Nature 1959, 184 (Suppl 5), 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, M.; Nishimura, N.; Oda, Y.; Owari, T.; Hori, S.; Morizawa, Y.; Gotoh, D.; Nakai, Y.; Anai, S.; Torimoto, K.; et al. Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin treatment-induced sleep quality deterioration in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: functional outcome assessment based on a questionnaire survey and actigraphy. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2022, 30, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzbeierlein, J.M.; Bixler, B.R.; Buckley, D.I.; Chang, S.S.; Holmes, R.; James, A.C.; Kirkby, E.; McKiernan, J.M.; Schuckman, A.K. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline: 2024 Amendment. The Journal of urology 2024, 211, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, W.J.M.; Ochando, J.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Fayad, Z.A.; Netea, M.G. Therapeutic targeting of trained immunity. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2019, 18, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfahlberg, A.; Kolmel, K.F.; Grange, J.M.; Mastrangelo, G.; Krone, B.; Botev, I.N.; Niin, M.; Seebacher, C.; Lambert, D.; Shafir, R.; et al. Inverse association between melanoma and previous vaccinations against tuberculosis and smallpox: results of the FEBIM study. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2002, 119, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfakianos, J.P.; Salome, B.; Daza, J.; Farkas, A.; Bhardwaj, N.; Horowitz, A. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG): Its fight against pathogens and cancer. Urologic oncology 2021, 39, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jones, M.S.; Ramos, R.I.; Chan, A.A.; Lee, A.F.; Foshag, L.J.; Sieling, P.A.; Faries, M.B.; Lee, D.J. Insights into Local Tumor Microenvironment Immune Factors Associated with Regression of Cutaneous Melanoma Metastases by Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guerin. Frontiers in oncology 2017, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, N.M.; Morales, A.; Lamm, D.L. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for genitourinary cancer. BJU international 2013, 112, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, M.E.; Kien, N.D.; Elmaraezy, A.; Abdelaziz, O.A.M.; Elsayed, A.L.; Halhouli, O.; Montasr, A.M.; Vu, T.L.; Ho, C.; Foly, A.S.; et al. Early vaccination protects against childhood leukemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 15986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, N.T.; Chang, S.; Howard, R.S.; Martinez, A.; Harrison, L.H.; Santosham, M.; Aronson, N.E. Association of BCG Vaccination in Childhood With Subsequent Cancer Diagnoses: A 60-Year Follow-up of a Clinical Trial. JAMA network open 2019, 2, e1912014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Berzofsky, J.A. Trained immunity inducers in cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology 2024, 15, 1427443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, J.S.; Sohn, D.H. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Inflammatory Diseases. Immune network 2018, 18, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Puffelen, J.H.; Novakovic, B.; van Emst, L.; Kooper, D.; Zuiverloon, T.C.M.; Oldenhof, U.T.H.; Witjes, J.A.; Galesloot, T.E.; Vrieling, A.; Aben, K.K.H.; et al. Intravesical BCG in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer induces trained immunity and decreases respiratory infections. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udagawa, M.; Kudo-Saito, C.; Hasegawa, G.; Yano, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Yaguchi, M.; Toda, M.; Azuma, I.; Iwai, T.; Kawakami, Y. Enhancement of immunologic tumor regression by intratumoral administration of dendritic cells in combination with cryoablative tumor pretreatment and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin cell wall skeleton stimulation. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2006, 12, 7465–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Lin, J.; Tan, W.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Lin, D.; Chen, T.; Zhou, J.; et al. Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) activates lymphocyte to promote autophagy and apoptosis of gastric cancer MGC-803 cell. Cellular and molecular biology 2018, 64, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, C.; Cruces, K.P.; Riestra Ayora, J.; Martin-Sanz, E.; Sanz-Fernandez, R. BCG immune activation reduces growth and angiogenesis in an in vitro model of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6395–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Morgan, M.J.; Chen, K.; Choksi, S.; Liu, Z.G. Induction of autophagy is essential for monocyte-macrophage differentiation. Blood 2012, 119, 2895–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Shi, F.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, F.; Sun, M.H.; Sun, Q.; Chen, L.; Li, D.; Jiang, C.Y.; Zhao, R.Z.; et al. M1 macrophage mediated increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) influence wound healing via the MAPK signaling in vitro and in vivo. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2019, 366, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Tumor Immunity. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 583084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Dehlaghi, F.; Mohammadi, P.; Valipour, E.; Pournaghi, P.; Kiani, S.; Mansouri, K. Autophagy: A challengeable paradox in cancer treatment. Cancer medicine 2023, 12, 11542–11569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.W.; Lee, S.H. The Roles of Autophagy in Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleyto-Seldas, N.; Efeyan, A. The mTOR-Autophagy Axis and the Control of Metabolism. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 655731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puente, C.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Jiang, X. Nutrient-regulated Phosphorylation of ATG13 Inhibits Starvation-induced Autophagy. The Journal of biological chemistry 2016, 291, 6026–6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.G.; Master, S.S.; Singh, S.B.; Taylor, G.A.; Colombo, M.I.; Deretic, V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 2004, 119, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Orozco, M.; Strong, E.J.; Paroha, R.; Lee, S. Reversing BCG-mediated autophagy inhibition and mycobacterial survival to improve vaccine efficacy. BMC immunology 2022, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Bakhru, P.; Saikolappan, S.; Das, K.; Soudani, E.; Singh, C.R.; Estrella, J.L.; Zhang, D.; Pasare, C.; Ma, Y.; et al. An autophagy-inducing and TLR-2 activating BCG vaccine induces a robust protection against tuberculosis in mice. NPJ vaccines 2019, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Sanchez, M.J.; Barrios-Payan, J.A.; Segura-Cerda, C.A.; Flores-Valdez, M.A.; Mata-Espinosa, D.; Pedroza-Roldan, C.; Yadav, R.; Saini, D.K.; de la Cruz, M.A.; Ares, M.A.; et al. BCG∆BCG1419c and BCG differ in induction of autophagy, c-di-GMP content, proteome, and progression of lung pathology in Mycobacterium tuberculosis HN878-infected male BALB/c mice. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3824–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivanainen, S.; Koivunen, J.P. Possibilities of Improving the Clinical Value of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapies in Cancer Care by Optimizing Patient Selection. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, C.; Lee, M.; Hoen, D.; Zehir, A.; Berger, M.F.; Seshan, V.E.; Chan, T.A.; Morris, L.G.T. Response Rates to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Microsatellite-Stable Solid Tumors With 10 or More Mutations per Megabase. JAMA oncology 2021, 7, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, F.; Bonfim, M.; da Silva Vasconcelos Sousa, P.; Mengel, J.; Ribeiro Castello-Branco, L.R.; Pinho, R.T. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Immunotherapy for Cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylosmaki, E.; Fusciello, M.; Martins, B.; Feola, S.; Hamdan, F.; Chiaro, J.; Ylosmaki, L.; Vaughan, M.J.; Viitala, T.; Kulkarni, P.S.; et al. Novel personalized cancer vaccine platform based on Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, K.; Melnick, K.; Mott, S.L.; Carvalho, F.L.F.; Zafar, A.; Clinton, T.N.; Mossanen, M.; Steele, G.S.; Hirsch, M.; Rizzo, N.; et al. Sequential intravesical gemcitabine/docetaxel provides a durable remission in recurrent high-risk NMIBC following BCG therapy. Urologic oncology 2023, 41, 458 e451-458 e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Chakra, M.; Packiam, V.T.; Duquesne, I.; Peyromaure, M.; McElree, I.M.; O’Donnell, M.A. Combination intravesical chemotherapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) as first-line or rescue therapy: where do we stand now? Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy 2024, 25, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentsch, C.A.; Bosshard, P.; Mayor, G.; Rieken, M.; Puschel, H.; Wirth, G.; Cathomas, R.; Parzmair, G.P.; Grode, L.; Eisele, B.; et al. Results of the phase I open label clinical trial SAKK 06/14 assessing safety of intravesical instillation of VPM1002BC, a recombinant mycobacterium Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG), in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and previous failure of conventional BCG therapy. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1748981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://newtbvaccines.org/vaccine/vpm1002/. Available online: https://newtbvaccines.org/vaccine/vpm1002/ (accessed on 26 Octomber).

- Rentsch, C.A.; Thalmann, G.N.; Lucca, I.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Wirth, G.J.; Strebel, R.T.; Engeler, D.; Pedrazzini, A.; Huttenbrink, C.; Schultze-Seemann, W.; et al. A Phase 1/2 Single-arm Clinical Trial of Recombinant Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) VPM1002BC Immunotherapy in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Recurrence After Conventional BCG Therapy: SAKK 06/14. European urology oncology 2022, 5, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhtreiber, W.M.; Tran, L.; Kim, T.; Dybala, M.; Nguyen, B.; Plager, S.; Huang, D.; Janes, S.; Defusco, A.; Baum, D.; et al. Long-term reduction in hyperglycemia in advanced type 1 diabetes: the value of induced aerobic glycolysis with BCG vaccinations. NPJ vaccines 2018, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, H.F.; Mochizuki, Y.; Kuhtreiber, W.M.; Takahashi, H.; Zheng, H.; Faustman, D.L. Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) and prevention of types 1 and 2 diabetes: Results of two observational studies. PloS one 2023, 18, e0276423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.faustmanlab.org/publications/.

- Haahr, S.; Michelsen, S.W.; Andersson, M.; Bjorn-Mortensen, K.; Soborg, B.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Melbye, M.; Koch, A. Non-specific effects of BCG vaccination on morbidity among children in Greenland: a population-based cohort study. International journal of epidemiology 2016, 45, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensballe, L.G.; Ravn, H.; Birk, N.M.; Kjaergaard, J.; Nissen, T.N.; Pihl, G.T.; Thostesen, L.M.; Greisen, G.; Jeppesen, D.L.; Kofoed, P.E.; et al. BCG Vaccination at Birth and Rate of Hospitalization for Infection Until 15 Months of Age in Danish Children: A Randomized Clinical Multicenter Trial. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2019, 8, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, M.J.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Martinon-Torres, F. Nonspecific (Heterologous) Protection of Neonatal BCG Vaccination Against Hospitalization Due to Respiratory Infection and Sepsis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2015, 60, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltz-Buchholzer, F.; Biering-Sorensen, S.; Lund, N.; Monteiro, I.; Umbasse, P.; Fisker, A.B.; Andersen, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Aaby, P.; Benn, C.S. Early BCG Vaccination, Hospitalizations, and Hospital Deaths: Analysis of a Secondary Outcome in 3 Randomized Trials from Guinea-Bissau. The Journal of infectious diseases 2019, 219, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankabirwa, V.; Tumwine, J.K.; Mugaba, P.M.; Tylleskar, T.; Sommerfelt, H.; Group, P.-E.S. Child survival and BCG vaccination: a community based prospective cohort study in Uganda. BMC public health 2015, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofrit, O.N.; Bercovier, H.; Klein, B.Y.; Cohen, I.R.; Ben-Hur, T.; Greenblatt, C.L. Can immunization with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) protect against Alzheimer’s disease? Medical hypotheses 2019, 123, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinger, D.; Hill, B.L.; Barda, N.; Halperin, E.; Gofrit, O.N.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Rappoport, N.; Linial, M.; Bercovier, H. Bladder Cancer Immunotherapy by BCG Is Associated with a Significantly Reduced Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. Vaccines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makrakis, D.; Holt, S.K.; Bernick, C.; Grivas, P.; Gore, J.L.; Wright, J.L. Intravesical BCG and Incidence of Alzheimer Disease in Patients With Bladder Cancer: Results From an Administrative Dataset. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders 2022, 36, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Praharaj, M.; Lombardo, K.A.; Yoshida, T.; Matoso, A.; Baras, A.S.; Zhao, L.; Srikrishna, G.; Huang, J.; Prasad, P.; et al. Re-engineered BCG overexpressing cyclic di-AMP augments trained immunity and exhibits improved efficacy against bladder cancer. Nature communications 2022, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xu, R. RORalpha, a potential tumor suppressor and therapeutic target of breast cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2012, 13, 15755–15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, T.V.; Chernov, I.P.; Monastyrskaya, G.S.; Kondratyeva, L.G.; Sverdlov, E.D. Cancer Stem Cells: Plasticity Works against Therapy. Acta naturae 2015, 7, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. Journal of hematology & oncology 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, R.; Mestre-Farrera, A.; Yang, J. Update on Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Cancer Progression. Annual review of pathology 2024, 19, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Xu, R. Retinoid orphan nuclear receptor alpha (RORalpha) suppresses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by directly repressing Snail transcription. The Journal of biological chemistry 2022, 298, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, G.; Matzaraki, V.; Bulut, O.; Baydemir, I.; Ferreira, A.V.; Rabold, K.; Moorlag, S.; Koeken, V.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Mourits, V.P.; et al. RORalpha negatively regulates BCG-induced trained immunity. Cellular immunology 2024, 403-404, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarenezhad, E.; Kanaan, M.H.G.; Abdollah, S.S.; Vakil, M.K.; Marzi, M.; Mazarzaei, A.; Ghasemian, A. Metallic Nanoparticles: Their Potential Role in Breast Cancer Immunotherapy via Trained Immunity Provocation. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Li, W.; Zheng, P.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; He, J.; Long, Q.; Ma, Y. A “trained immunity” inducer-adjuvanted nanovaccine reverses the growth of established tumors in mice. Journal of nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, Y.; Milling, L.E.; Chang, J.Y.H.; Santollani, L.; Sheen, A.; Lutz, E.A.; Tabet, A.; Stinson, J.; Ni, K.; Rodrigues, K.A.; et al. Intratumourally injected alum-tethered cytokines elicit potent and safer local and systemic anticancer immunity. Nature biomedical engineering 2022, 6, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, E.A.; Agarwal, Y.; Momin, N.; Cowles, S.C.; Palmeri, J.R.; Duong, E.; Hornet, V.; Sheen, A.; Lax, B.M.; Rothschilds, A.M.; et al. Alum-anchored intratumoral retention improves the tolerability and antitumor efficacy of type I interferon therapies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2022, 119, e2205983119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.V.; Santos, C.C.; Leite, L.C.; Nascimento, I.P. Characterisation of alternative expression vectors for recombinant Bacillus Calmette-Guerin as live bacterial delivery systems. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e190347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial. The ‘war on cancer’ isn’t yet won. Nature 2022, 601, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.; Zhukova, L.; Kondratyeva, L.; Buzdin, A.; Chernov, I.; Sverdlov, E. Tumor Cell Communications as Promising Supramolecular Targets for Cancer Chemotherapy: A Possible Strategy. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Effector | In immunity | In Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| GM-CSF | APC differentiation and expansion, Monocytes activation (↑HLA-DR; ↑CD86; ↑TNFα; ↑IL-1β) [56], differentiation to DC, MΦ [57,58] | Dual role in cancer progression [59,60] Myeloid DCs differentiation, enhancing Th1 responses [61] Th9 cell differentiation, antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses ↑ [62] Excessive - exhaust immune cells, cancer growth ↑; insufficient - immune surveillance ↓ [60] |

| Il-1β | Main inflammation and fever activator [63] Autoinflammatory syndromes [64] IL-1β signaling activates NF-κB and MAPK pathways, inducing expression of various inflammatory genes [65] T cell polarization towards Th1 and Th17 subtypes [66] IFNs signaling ↑, immunity against some viral infections ↑ [67] |

Resolution of acute inflammation leading to the induction of adaptive anti-tumor responses; chronic inflammatory - risk of developing cancer ↑ [68] Chronic inflammation - tumor growth ↑, metastasis ↑ [66] In TME: angiogenesis ↑, tumor growth, metastasis ↑ [69,70] Suppresses anti-tumor immune responses, metastasis ↑ [71] Immunosuppressive monocytes polarization to IL-10 MΦ, CD8+ T inhibition [72] Angiogenesis ↑, antiapoptotic ↑, MDSC ↑ [66] |

| IFNs | Induce antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory effects; enhance antigen presentation, [73]. Inflammatory cytokines production↑, anti-inflammatory ↓ [74,75] NK cytotoxic activity ↑, MΦ phagocytosis↑ and pro-inflammatory cytokines production↑; DCs maturation and activation, antigen presentation↑, T cells activation ↑ [76,77] CD4+T >> Th1; CD8+T activation↑, proliferation↑ [78,79,80] |

Persistent IFN expression can lead to immunosuppression in later stages of tumor progression [81]. Cancer-immunity cycle: antigen release, T cell activation, tumor cell killing [82]. Chronic stimulation - tumor resistance ↑ [83] IFNγ tumor angiogenesis↓; Treg apoptosis↑, proinflammatory M1 MΦ antitumor activity ↑ immunosuppression↑, T cell apoptosis↑, immune tolerance↑ [84] Cancer cell stemness ↑, metastasis ↑ [85,86]. EMT↑ [87]. >PD-L1&IDO↑ immune evasion↑ [88] |

| TNFα | Major pro-inflammatory cytokine [89,90] Activates various immune cells, including MΦs and NFs, pathogen phagocytosis ↑; inflammatory mediators ↑ [89],[91] Apoptosis ↑ [90,92] ILs ↑ (e.g., IL-1, IL-6); IFNs ↑ [89,93] Excessive activation – chronic inflammation – autoimmune diseases [89] |

Pro-inflammatory cancer permissive TME [91,94] Immunosuppressive TME [95] NF-κB activation - cancer survival ↑, apoptosis resistance ↑, invasion ↑, metastasis ↑ [96,97]. VEGF↑, angiogenesis↑ [98] |

| IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory [99] B cells activation and differentiation; Ig production; humoral immune response [100] Naive CD4+ T → Th17 cells; Treg activity modulation; prevent autoimmunity [101] C-reactive protein production [102] Hematopoiesis regulation, HSCs differentiation [103] Metabolic regulation, insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism [104] |

Dual action in TME - drives malignancy/promotes anti-tumor adaptive immunity [105] Proliferation and survival of cancer cells↑, JAK/STAT3↑, cell growth↑, apoptosis↓ [106] Lymphangiogenesis ↑, VEGF↑, tumor growth↑, invasion ↑ [107] Immune escape↑, immunosuppressive TME↑, Tregs↑, MDSCs↑ [108] N-cadherin↑ E-cadherin↓ EMT↑, metastasis↑, migration↑, invasion↑ [109] |

| Th1 polarization | Th1 - immune response against intracellular pathogens, primarily through the production of cytokines like IFNγ and TNFα MΦ activation↑, phagocytosis↑, CD8+T&NK functionality↑, Th2 response↓ [110,111,112] IFNg secretion [113] |

Th1 - anti-tumor immunity: production IFNγ↑ > cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T/NK cells↑. MΦ activation↑, >M1 MΦ phenotype pro-inflammatory, phagocytosis↑, ROS↑, tumor growth↓, angiogenesis↓, tumor immune evasion↓ [114,115] |

| Acetate/ acetyl-CoA | Acetyl-CoA - H3K27ac acetylation [116] Metabolic supply for Tcells & MΦ, Tregs differentiation, Th2 functionality, Anti-inflammatory, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokine production, anti-inflammatory M2 MΦ↑ [117,118,119] |

Acetate increase the expressions of SNAI1 and ACSS2 under glucose limitation. ACSS2 knockdown > SNAI1↓, cell migration↓; ACSS2 overexpression > SNAI1↑, histone H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac)↑, metastasis↑, migration↑ [116] ACSS2 catalyzes the conversion of acetate to acetyl-CoA [120] ACSS2 inhibition – impair tumor cell metabolism and potentiate antitumor immunity [120] Regulation of acetyl-CoA metabolic enzymes may support tumor growth and TME survival [121] |

| Factor | In immunity | In Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| NOD2-deficienсy | Fail in infection resistance Fail in TRIM formation [123] |

Pro-tumorigenic MΦ, promote lung adenocarcinoma progression [123] |

| Butyrate | Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) inhibition, HDAC3 deacetylates H3K27ac and H3K9ac – active promoter/open chromatin marks [124] | Therapeutic target in cancer [125] |

| Fumarate | Inhibitory effect to the activity of KDM5, induce enrichment of H3K4me3 on promoters [126] |

Fumarate hydratase loss is possibly pro-tumorigenic [126] Fumarate accumulation and cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer, supporting its oncometabolite role [127,128] |

| Ascorbate | Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory [129] Abrogate TRIM inhibiting HIF1a [130] |

One of the most controversial drugs, despite many articles about antitumor action, it is suggested that there is not sufficient evidence base. Thus, at the time (Apr 5, 2024), the FDA has not approved the use of IV vitamin C as a treatment for cancer [131] Facilitates tumour cell death through the generation of ROS and ferroptosis [132] Potential anti-tumor capabilities [133] Boosts DNA damage and cell death in melanoma cells [134] High concentrations triggering cell death and low amounts promoting tumor growth [135] |

| Rapamycin, 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) or metformin | Inhibition of the mTOR pathway or glycolysis [136] | Rapamycin anti-cancer role discussion [137,138]. Metformin and 2DG exhibit multiple metabolic and immunomodulatory anti-cancer effects, suppressed proliferation or PD-L1 expression [139] |

| Name | Modification | Studies | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPM1002 | Recombinant, urease C-deficient, listeriolysin expressing BCG vaccine strain generated in order to induce a broader immune response against mycobacterial antigens. Consequently, VPM1002 was formulated as VPM1002BC for intravesical immunotherapy. | NCT04387409, P3 NCT04351685, P3 NCT03152903, P2 |

[227] |

| VPM1002BC | Recombinant live BCG strain in which the urease C gene is deleted by insertion of the gene encoding the haemolysin listeriolysin (LLO). | NCT02371447,P1/2 NCT04630730; P2 |

[228] [226] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).