1. Introduction

In 1951 Richard Asher described a bizarre entity in the form of child maltreatment called “Munchausen syndrome by proxi” (MSBP), consisting in fabrication or induction of signs and symptoms, as well as alteration of laboratory tests by a caregiver. Nowadays, this psychiatric pathology is recognized as factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA) and is considered to be a very serious form of child abuse, potentially deadly. Alarm signs are frequent medical visits in numerous clinics and with numerous doctors, strange symptoms which are never objectified during hospitalization [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Even though it has been previously described as a rare disorder, these days cases are frequently encountered, one stranger than another, with serious and life-threatening presenting symptoms of the abused child [

4]. The mortality rate of children maltreated by MHBP adults reaches 10% [

6]. True prevalence of MHBP syndrome remains unknown, probably because many cases are overlooked [

1]. Less severe cases are not reported and some may remain undetected because of the hidden nature of the abuse. The maltreatment usually begins early in child’s life, the average age at diagnosis of children exposed being between 20 and 40 months [

4,

7].

The perpetrators of MHBP syndrome are usually mothers, but cases where fathers were maltreating their children have been cited in the literature [

1,

5,

6]. Caregivers are usually well-educated persons, some of them actually having medical background. This allows them to foresee physician’s questions or investigation proposals, making the diagnosis process tricky [

1,

7].

The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) defines MHBP syndrome with the following criteria, which must always be met: 1. The Perpetrator engages in the deceptive falsification of physical or psychological signs or symptoms, or of induction of injury or disease in another; 2. The Perpetrator presents the victim to others as ill, impaired or injured; 3. The deceptive behavior is present also in absence of external incentives; 4. The behavior is not better accounted for by another mental disorder (psychotic or delusional disorder) [

2,

3,

6,

8].

It is of crucial importance that a physician, having even the slightest suspicion, gathers signs of this disorder. A child with recurrent symptoms, never objectified during hospitalization, never matched by expected laboratory result should raise a red flag. Also, worsening of these symptoms every time the discharge moment approaches. Treatment course that is not clinically consistent, a mother that seems too calm despite the child’s serious illness, who welcomes even painful medical examinations for her child, should trigger suspicion among the medical staff (

Figure 1). There are more indicators of this psychiatric disorder, such as peculiar family medical background (sudden unexplained deaths), father emotionally distant or absent from child’s life and changing of declared residence every new admission [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

However, it is important to distinguish MHBP syndrome from other similar entities, such as anxiety of caregiver, who has simply excessive care for the child, but is not abusive. Poor compliance to treatment is another issue, resulting in child’s persisting or worsening of illness. Also, malingering the child with an external purpose (obtaining financial benefits for example), should be ruled out [

2,

3,

6].

Among the commonest signs and symptoms described in children with MHBP are seizures, unexplained metabolic and hydroelectrolytic disturbances, unexplained bleedings, fever with no explanation, recurrent pain in various sites, genital or skin injuries, subcutaneous emphysema or “accidental” poisoning. All conditions have one thing in common – they are easily inducible by another person. This brings us to the most severe behavior of caregivers with MHBP, as they might be capable of anything [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] (

Figure 2).

2. Case series

A 3 years 8 months old boy, first presented to our department in October 2022 for continuous fever for 21 days (daily, with pause periods no longer than 12 hours) and pain in lower limbs for 3 weeks. He had previously received at home antipyretic medication and oral antibiotic treatment, without fever remission. Initially, he did not associate cutaneous rash, pain or joint swelling, abnormal stools or reno-urinary symptoms, but his mother described episodes of nocturnal sweets which started roughly at the same time as the fever.

From the patient’ family history, it is important to be mentioned that his mother had acute lymphoblastic leukemia at age 14 and a chest tumor surgically removed at age 18. His father was in good health. Patient medical history did not reveal anything significant.

Clinical examination at admission identified no fever, normal growth, normal parameters of cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive functions, muscle pain in lower limbs, malformed ears and left testicular agenesis.

The patient underwent complex investigations to exclude different causes of prolonged fever. Infectious diseases were ruled out through peripheral bacterial cultures and blood culture, which were all negative (but we have to keep in mind that the boy received prior to admission multiple courses of antibiotics). Viral infections were excluded: Epstein-Barr (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis B Virus (HVB), Hepatitis C Virus (HVC). IgG for SARS-COV 2 came out positive, but there were no arguments for long Covid19 syndrome. Tuberculosis was excluded: negative QUANTIferon and normal radiologic imaging. Further, no inflammatory syndrome, normal values of immune blood testing, serum complementum and immune circulating complexes made an autoimmune disease improbable. Abdominal and thoracic imaging ruled out solid tumors. Blood count with peripheral blood smear without anomalies and no atypical cells detected on medullary biopsy excluded a hematological neoplasia.

Three weeks later, patient comes back with fever and left knee swelling with partial function impairment, of 24 hours onset. His mother also described, two days prior, non-itching maculo-papular cutaneous rash on chest and belly, which disappeared spontaneously. Clinical examination did not encounter anything out of the ordinary (no fever, no rash), just mild painful swelling of left knee. Laboratory investigations were also, this second time around, in normal range. Borellia infection was excluded. The orthopedic exam did not describe local inflammatory signs, joint mobility and knee X-ray were normal (

Figure 3). He received oral anti-inflammatory medication.

The patient came back every two weeks for fever. Screening for solid tumors and again autoimmune pathology came back with normal results. Again, infectious diseases were excluded through negative central and peripheral bacterial cultures, viral serologies. Repeatedly negative QUANTIferon alongside normal imaging and specific pulmonology examination ruled out tuberculosis. Malignant causes were again excluded by normal blood count and medullary aspirate, also normal ultrasounds and X-rays. Idiopathic juvenile arthritis (IJA) remained a possibility, as the patient had prolonged fever, joint pain, inflammatory syndrome with erythrocyte sedimentation rate higher than C reactive protein; he, however, did not meet the time criteria – symptoms for at least 6 weeks. Anticitrullinated protein antibodies, anti-vimentin antibodies and rheumatoid factor were negative; nevertheless, negative antibodies do not certify as exclusion criteria for IJA.

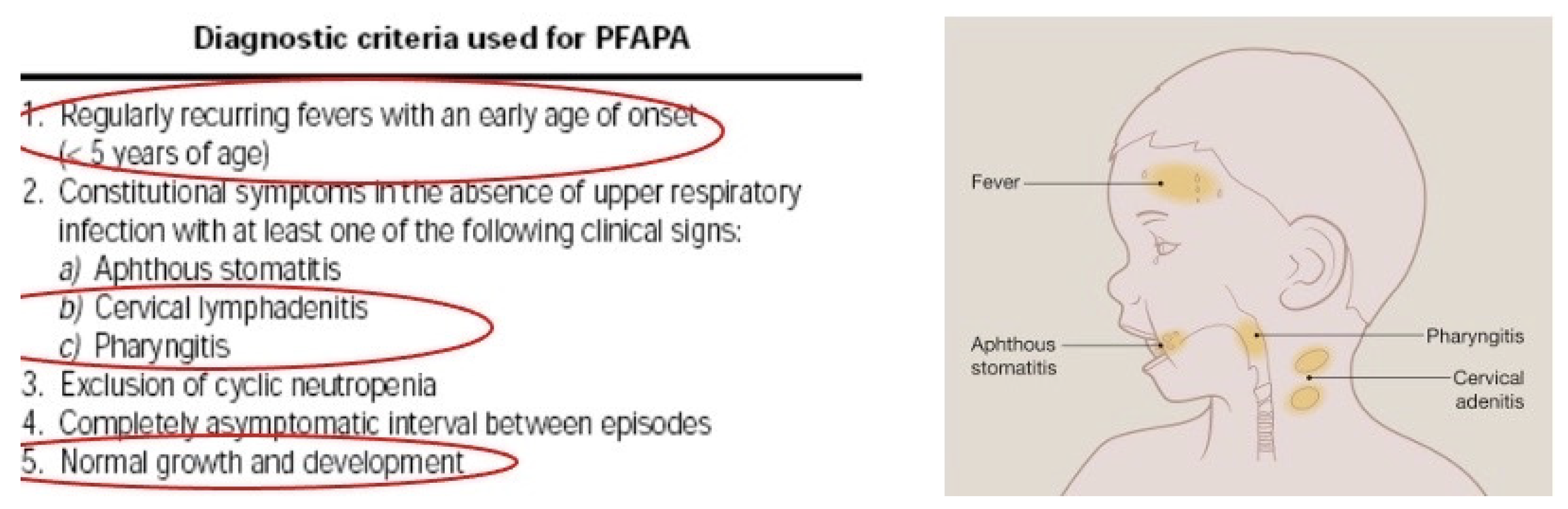

Two weeks later the patient returns to our clinic with fever and swallowed neck lymph nodes. Periodic familial fever syndrome (PFAPA) was also considered this time.

He was younger than 5 years, had recurrent fever, cervical lymphadenitis, pharyngitis, normal growth and development (

Figure 4). The therapeutic challenge was performed, a single dose of oral cortisone was administered with no response. Current lab analysis was again normal. The primary physician started to notice a pattern: declared symptoms (present at home), but never during hospitalization. Rare neoplasia was considered (cavum, brain). Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of head and neck returned normal findings. The patient continued a course of prolonged, high fever. A combined course of antibiotic and antifungal treatments was started, with good results – the fever ceased temporarily.

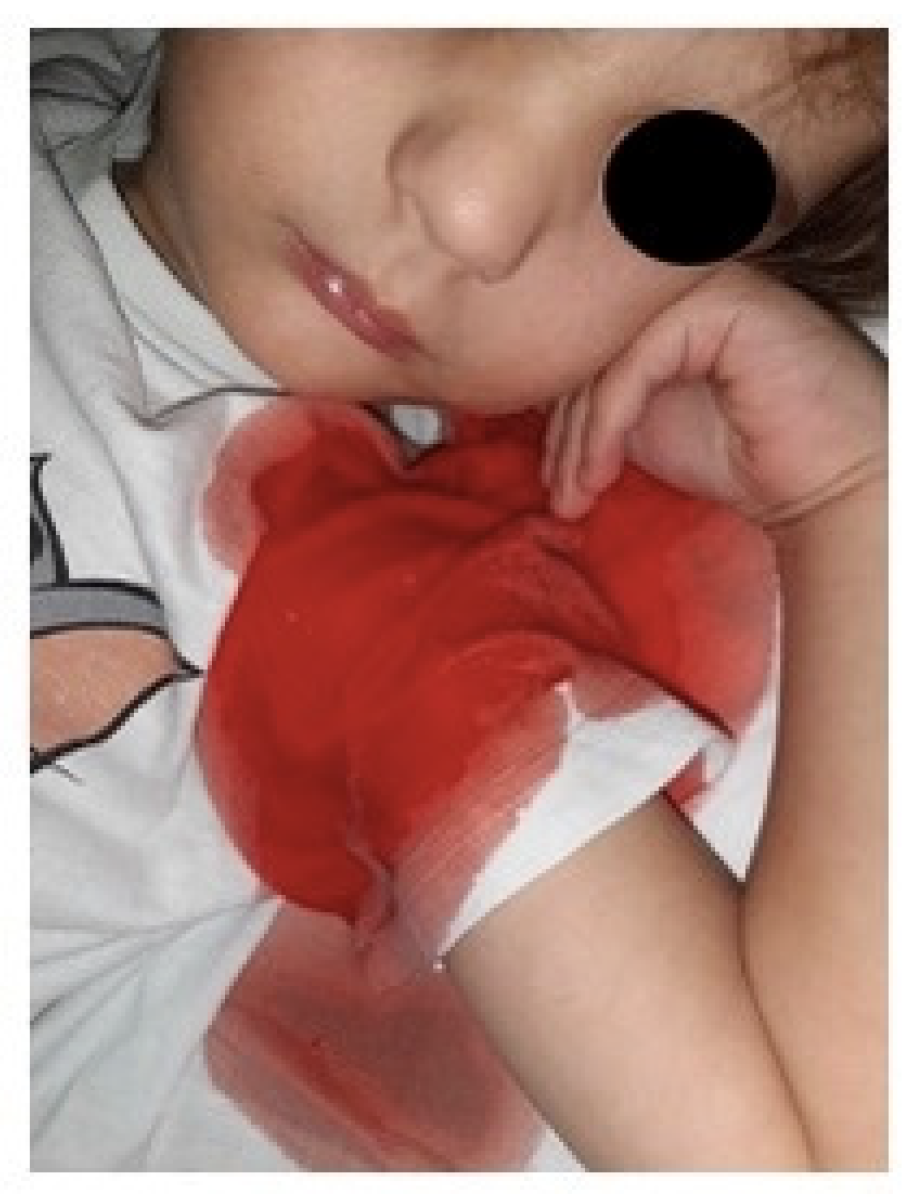

Approximately one week after the previous hospital admission, the patient returns for fever and joint pain. But this time, the mother describes a new symptom – hemoptysis. Also, the family medical history is now far more complex, abundant in various diseases: father had long-time non-investigated cytolysis, maternal grandmother lung cancer, maternal grand grandfather cerebral tumors, paternal grandfather prolonged nose bleeds with no certain cause, maternal great-grandmother gall-bladder cancer, first-line maternal cousin aged 3 was diagnosed with nephroblastoma.

This time around, tuberculosis was ruled out again (QUANTIferon, Bacillus Kock (BK) cultures and polymerase chain reaction for BK were all negative). Congenital immunodeficiency was also taken into consideration. However, the boy did not experience recurrent, severe infections, in his first three years of life; immunogram, leukocyte immunophenotyping, HIV had normal values. A full body scan computed tomography (CT) helped rule out nephroblastoma, neuroblastoma and malignant head, chest or abdominal tumors. Keeping in mind the so-called maternal line familial malignant memorabilia, genetic testing was recommended, WES testing for hematological-linked syndromes and syndromes which associate multiple malignancies. The blood test was sent for evaluation, but as we later discovered, the mother, although declared she filled in and sent the required consent forms, never did so. During this admission, the boy had numerous declared episodes of hemoptysis; the mother showed photographs on a daily basis; no medical staff actually saw the bleeding episodes (

Figure 5). Surprisingly, despite recurrent episodes of bleeding, the hemoglobin levels were always steady.

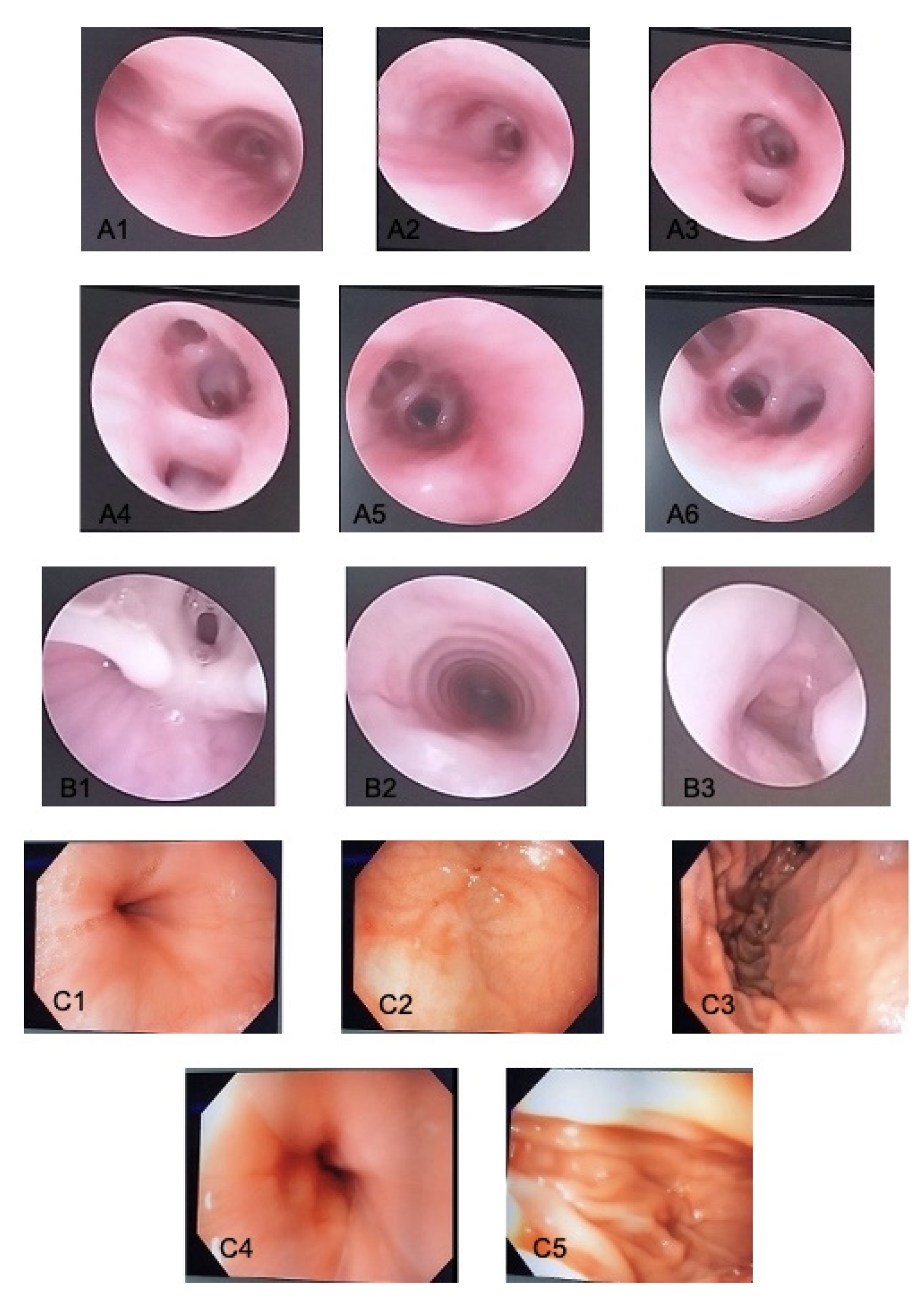

A pan-endoscopy of upper and lower respiratory tract was performed, with no signs of active or recent bleeding in the nose, cavum, bronchi (

Figure 6 A, B) and upper digestive tract (

Figure 6 C). Bronchial aspirate, gastric and bronchi lavage were negative for BK. Vascular MRI of the head, neck and chest ruled out bleeding due to vascular malformation.

With complex hemostatic therapy the hemoptysis episodes suddenly stopped. The patient was asymptomatic, with normal blood tests. In the day of discharge a new symptom emerged – gross, painless, macroscopic hematuria with dysmorphic urinary erythrocytes. Complex coagulation testing returned normal results. The hemoglobin levels were still steady regardless of severe active bleeding. The patient had normal diuresis, no edema, hypertension or nitrogen retention. Acute severe glomerulonephrytis was now considered (although complete clinical criteria were not met) and the patient was started on intravenous cortisone and transferred to a Nephrology Department for further testing and treatment. Systemic vasculitis (Goodpasture syndrome or others) were now being considered (prolonged fever, recurrent hemoptysis and hematuria). Anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (pANCA), anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-glomerular membrane antibodies were negative.

Over the 4 months course of repeated hospital admissions, the patient’s mother managed to develop an attachment relationship with the attending physician and the medical personnel. She was respectful and patient, always calm and collected despite the serious illness of her child. She took advantage of the empathic attitude of her doctor and used details she learned from her physician’s private life to gain sympathy. She had an active social media presence, took part in various profile groups, from where she constantly received validation and financial support. She constantly changed her declared home address from one admission to another. She declared being pregnant and having a difficult and complicated pregnancy, presented herself as the sole caregiver of the child, the father being away on a military mission. At some point she even declared having medical background (2 years of Medical School).

The medical personnel attitude in the Nephrology Clinic was different, perceived by the mother as “cold and distant”; as a result, in 5 days the patient’s severe acute glomerulonephritis was inexplicably cured (from gross hematuria to normal urine sample). A few hours after discharge from the Nephrology Clinic (normal clinical examination and blood tests on discharge), the mother returned to our clinic describing sudden onset abundant hematemesis. The hemoglobin level was normal. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was urgently performed, again with no signs of active or recent bleeding. This was the turning point of the story, the attending physician now put everything in a different perspective. During the 4 months period of repeated admissions, child’s symptoms were never objectified during hospitalization, never consistent with the declared symptoms and test results. Suspecting now Munchausen Syndrome by proxy, the doctor’s attitude changed suddenly from empathic to distant. The mother stopped receiving validation and sympathy, resulting in a subsequent paucity of complaints and the disappearance from follow-up.

3. Discussions

“To be or not to be…”. That was the question in our case, because every new declared symptom, every new action we took, every new investigation, new differential diagnosis failed to reveal the pathology that this child allegedly suffered from. So, we began to wonder about the truthfulness of the declared story.

MHBP represents a severe mental derange. The purpose of these adults is to fabricate diseases to their own children by inventing signs and symptoms or by continuously asking for invasive medical intervention. It is a serious form of child abuse, potentially deadly. Main alarm signs of this psychiatric pathology are multiple “rendez-vous” with different doctors in different hospitals, strange symptoms which are never objectified during admission time, but only at home under the supervision of their parent [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Laboratory investigations performed several times never seem to match with child described symptoms. The parent might bring to the doctor’s attention several medical documents with numerous diagnosis and investigations which apparently go with child’s symptoms. In our case, the mother was the only one who “caught” fever episodes and bleeding events, no medical personnel had ever experienced first-hand these symptoms. Child symptoms appeared always at home or at night-time during hospitalization and were described by the mother and “documented” with photographs.

Unfortunately, MHBP leads parents into terrible actions, such as adding fresh blood to stool or urine samples, heating-up the thermometer to mime fever, giving the child certain medication to induce symptoms (such as insulin to provoke hypoglycemia), starving the child or worse, contaminating an intravenous line to induce systemic infection [

12,

13,

14,

15,

18]. Our patient’s mother most likely spread fresh blood all over the child’s shirt during night-time and claiming the boy was coughing out blood, added fresh blood to urine samples to mimic kidney damage. She managed to make up a systemic vasculitis, the patient underwent repeated, invasive investigations and ended up receiving systemic cortisone therapy.

The DSM-5 defines MHBP with specific criteria, which we elaborated above in the Introduction section: the caregiver falsifies physical or psychological signs or symptoms, or induces injury or disease in child; parent presents the victim to others as ill, impaired or injured; the deceptive behavior is present also in absence of external incentives [

2,

3,

6,

8]. In the case presented, the mother described recurrent and inexplicable symptoms, she was always lurking for medical attention. She had developed an attachment relationship with the attending physician and other medical personnel. She proudly filled the shoes of the “heroine mother”. She embellished family medical background with every admission and described new symptoms depending on the type of questions the doctor would ask. Every time the discharge moment approached, another aggravating symptom appeared. She was particularly active on social media, where she received validation and occasionally financial support.

MHBP must not be mistaken by another psychiatric pathology such as psychotic or delusional disorder [

2,

3,

6]. The medical team involved in the case excluded step by step various differential diagnosis (

Table 1), until a turning point, when the elaborate lie became obvious. Because the mother described prolonged fever, alongside a newly emerged symptom every admission, multiple pathologies had to be ruled out: from tuberculosis to congenital immunodeficiency, from PFAPA syndrome to idiopathic juvenile arthritis, from vascular malformations to Goodpasture syndrome. Complex blood, urine, imagistic and endoscopic investigations had normal results, despite severe complaints.

In this psychiatric condition, a “love triangle” between mother-child-attending doctor is present. As a doctor, we must always preserve our clear judgment. But in some cases, when a patient becomes “a friend” of the clinic because of numerous admissions, has severe undiagnosed pathology, many physicians tend to establish an attachement connection. In such cases, doctors are at risk, because MHBP adults take advantage of the doctor’s humanity side and use it to their own best [

7]. That is exactly what the patient’s mother did and it served her well for a period of 4 months. The doctor is dragged, without his will and knowledge, into contributing to invasive investigations and unnecessary therapy. So, there’s a talk about ethical and legal issues associated with MHBP.

In Romania, this syndrome is recognized as a form of child abuse by Decision no. 49 of 19

th of January 2011: “Munchausen Syndrome by transfer (MBP) is the artificial creation of a child fake diseases by the parent; disease is induced by administration of drugs for poisoning, or by supporting the existence of symptoms in children who have never been confirmed by the specialists. In both cases, many parents require medical or surgical investigation, abusing the child repeatedly. Any functional sign can be invoked by parents to get painful and intrusive investigations and proceedings for the child” [

7,

21]. When the attending physician’s and allied health professionals’s attitude changed from empathic to distant, the mother disappeared from follow-ups.