1. Introduction

Development plans have different names in the selected countries. In South Africa they are called integrated development plans (IDPs), in Namibia they are called strategic plans, in Ghana they are called medium-term development plans (MTDPs) and in Zambia they are called integrated development plans (IDPs).

South Africa has been experiencing the impacts of climate change since the 1970s, with these effects intensifying each year [

1]. Trisos et al.’s study [

2] assert that the worst impact will be felt in Africa. Due to Africa’s socio-economic development circumstances and geographical location, it is more susceptible to the effects of climate change. Fourteen years later, the visible effects of climate change, from frequent floods and droughts to severe heat waves, are already being experienced by African countries [

2]. Given that most African countries are arid to semi-arid according to the Köppen climate classification, and experience warming at double the global average rate, the continent faces unique climate challenges. However, African country’s financial institutions are overburdened while governments are addressing historic transformation, social injustice, economic growth, and poverty eradication. Thus, climate change has not been prioritised nor are there sufficient resources available to address it [

3].

A research study by Bates et al. [

1] stated that by the 21st century, South Africa would experience diminished water resources, floods due to extreme rainfall events, prolonged droughts, high CO

2 emissions, and altered energy generation potential and demands, and this turned out to be an accurate projection. The rest of Africa has suffered the same plight. Unfortunately, sufficient mitigation actions were not put in place to circumvent these effects; had these warnings been taken seriously and acted upon, Africa would not be experiencing these harsh effects. This is why climate information and early warning systems, and their effective utilisation are critical.

Africa’s urbanisation is far exceeding that of the rest of the world, with twice as many people anticipated to be urbanised between 2020 and 2050 [

4]. This offers various economic opportunities but puts pressure on the ecosystem and its services [

4]. Due to urbanisation, most cities are becoming densely populated, with an estimated increase in the global city population from a current 55% to 70% in 2050 [

5]. This increases the strain on already frail infrastructure and a lack of sufficient energy and water capacity. Researchers have urged cities to take a proactive approach to climate change and to manage natural disasters [

6]. Ajibade [

7] states that urban planning should include land-use practices, environmental preservation, and policies enabling socio-economic development. These measures would have assisted KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, which experienced severe flooding with catastrophic impacts in 2022 and 2023. Proper use of early warning systems, adequate drainage infrastructure, healthy ecosystems and evolving urban planning could have prevented the devastation. The United Nations (UN) has emphasised the importance of building climate-resilient cities, which is reflected in its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, where cities are seen as crucial enablers in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

4]. To meet these SDGs, it is imperative that cities are managed through a systematic, sustainable approach, climate early warning systems are enhanced, and there is effective dissemination of this knowledge to prevent further harm to the planet. Whereas sustainable development is vital to preserving ecosystem services, research has shown that it is challenging to find pragmatic all-inclusive approaches to improving sustainability [

8]. There is thus an urgent need for the world to determine the most suitable way of integrating environmental sustainability into everyday life. Development plans may be the ideal instrument as they are the blueprint for managing cities.

Currently, municipal development plans are developed every four or five years; if there is a new administration, most of the projects are discontinued, as the new administration may choose to replace existing plans with their own objectives and vision [

9,

10]. For sustainable cities to exist, there should be a continuity of sustainable practices, which will stem from certain aspects of development plans being fixed. In their research, Todes [

11] argues that although development plans are crucial to enabling cities to develop sustainably, they are not in a state that can provide a planning system in which environmental sustainability can be enhanced. Thus, should environmental sustainability metrics be embedded in development plans, and these being fixed in the daily operations of the municipality, there is an opportunity for cities to enhance climate resilience [

12,

13,

14,

15]. An example of this is seen in Copenhagen. The HOFOR (Greater Copenhagen Utility) adopted the Copenhagen Climate Plan in 2012 to prioritise climate resilience and sustainable development[

16]. Skanderborg Municipality has effectively incorporated environmental sustainability metrics into its operations. It has also implemented a comprehensive set of sustainability indicators and resilience metrics to monitor and adapt to climate change [

17].

Thirty-five years after the publication of the Brundtland Report [

18], the three pillars of sustainability are still significant, and sustainability in cities is still vital to achieving sustainable development. In 1983, the UN formed the Brundtland Commission, which aimed at guiding the world to sustainable development, and the Brundtland Report titled “Our Common Future” was published in 1987. The report details how the world was moving towards a sustainable pathway by integrating development and environmental issues [

19].

Incorporating environmental sustainability into the Accra Metropolitan Assembly's (AMA’s) Medium Term Development Plan (MTDP) has been challenging due to the similar issues faced by South African cities. Accra is plagued by poor spatial planning which is exacerbated by the city's rapid and often unplanned urban expansion. Accra's growth has surpassed infrastructure development, resulting in inadequate provision of services and significant pressure on housing [

20], thus worsening the existing housing deficit [

21]. Accra's vulnerability to flooding is worsened by poor land-use planning and climate change due to its topography, characterised by low-lying areas prone to flooding, requiring robust planning and management strategies to mitigate flood risks [

22], and ensure integrated planning has environmental sustainability in mind. A research study by Karley [

23] showed that Accra’s issues are due to the lack of effective implementation and enforcement of urban planning regulations [

24]. These issues emphasise the need for a more integrated and sustained approach to urban planning and development, ensuring that environmental sustainability is a core component of Accra's growth strategy. This is key to addressing these challenges to build Accra’s resilience against climate change impacts and ensure that the city develops sustainably [

20,

21].

The city of Windhoek, much like Accra, faces challenges in integrating environmental sustainability into its strategic plan. There are significant financial constraints, a lack of resources and expertise to implement and sustain environmental sustainability measures [

25]. This includes limited funding for green infrastructure and ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) projects, which are crucial for building climate resilience [

26]. The city's governance structures are often ill-equipped to manage the integration of environmental sustainability into urban planning. Issues include a lack of effective channels for information dissemination, inadequate environmental impact assessment processes, and the absence of clear mandates for environmental management in informal settlements [

27]. Climate change exacerbates existing challenges, such as prolonged droughts and increased frequency of flash floods. The urban heat island effect further strains the city's resources and infrastructure, making it harder to maintain environmental sustainability [

26]. There is a low level of awareness among residents about the benefits of environmental sustainability and the importance of managing biodiversity. Therefore, it is crucial to have a multi-faceted approach that includes improving governance frameworks, securing financial resources, enhancing community involvement, and integrating environmentally sustainable practices into all levels of urban planning and development, which is provided for through the strategic plan.

The Lusaka City Council (LCC) faces challenges in implementing and enforcing environmental policies due to weak governance structures and institutional capacity [

28]. The LCC has acknowledged that effective planning and regulation requires better coordination among different sectors and stakeholders, which they struggled with. This would involve the need for improved land use regulation, investment direction, and enforcement of compliance with environmental standards [

29,

30]. The city recognizes the importance of urban planning that integrates environmental sustainability, strengthens governance and institutional capacities, and involves local communities to enhance resilience and improve service delivery. To effectively plan for environmental sustainability, it's crucial to involve the community, however, within the city of Lusaka, there is a lack of public awareness and engagement in environmental issues [

28]. Lusaka is plagued by prehistoric spatial planning like Windhoek, Accra, and South African cities. Lusaka’s planning frameworks still reflect colonial-era modernist approaches, emphasising physical zoning and segregation [

29].

Africa’s implementation of development plans lacks the integration of economic and ecological dimensions in city development (Grobbelaar, 2012; Pasquini et al., 2013). Even though the concept of development planning is regarded as a reliable tool for sustainable development, Todes (2006) cautions that it is not that easy to create an effective development plan, given the concern around the nature of politics and institutional dynamics in Africa, as these are support mechanisms for development plans evolving and being instruments of transformational sustainable development. All four selected cities have outdated frameworks that are not well-suited to modern needs for integrated, inclusive, and sustainable urban development. The persistence of such approaches hampers efforts to adopt more flexible and adaptive planning strategies that address current environmental challenges [

30]. Addressing the challenges faced by these African cities, heightened by climate change, requires integrating climate resilience into planning and promoting sustainable resource use and conservation.

This research saw it to be beneficial to evaluate how these cities have incorporated environmental sustainability into their development plans and draw lessons from the implementation. The research aimed to determine the barriers to development plans being a tool for advancing environmental sustainability within municipalities. This was to establish these limitations and find appropriate mechanisms for incorporating environmental sustainability into development plans in a realistic manner that can assist in turning development plans into practical robust strategic plans.

Cities play a vital role in the economic performance and prosperity of a country. Determining the limitations to successfully embedding environmental sustainability in the development plans of cities can assist Africa in moving towards becoming more climate resilient. The significance of this research is relevant not only to South Africa but to the greater African continent and could result in great strides being made in Africa towards developing more robust development plans that will enable sustainable development. Africa is trailing behind the Global North with climate adaptation and mitigation and does not have the luxury of time due to its vulnerability; this notion is supported by Shackleton et al. [

31] in their research on sub-Saharan Africa’s challenges to climate adaptation. Biesbroek et al. [

32] identified weak institutional capacity, limited prioritisation of environmental sustainability, intricate socio-ecological transition, and poor governance as some of Africa’s challenges to responding promptly to climate change. Like many African cities that are plagued by great legislation with lackluster implementation, Accra’s policies are ideally suited to support its sustainability initiatives; however, poor governance and fragile institutions are barriers [

33]. Thus, the outcomes of this research would help unlock barriers to the successful incorporation of environmental sustainability into municipal development plans and highlight enabling principles for environmental sustainability. This could be the paradigm shift that Africa needs to support the successful implementation of the African Union Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan. The African Union is committed to such pragmatic, sustainable practices; the African Union outlines how it will pursue transformative and equitable climate-resilient development pathways [

34]. These actions are highly needed in these times.

This research defines the integration of environmental sustainability into development planning as the direct inclusion of environmental sustainability projects and policies in municipal operations. It also encompasses the direct inclusion of environmental sustainability projects in municipal budgeting and planning through their development plans. The research will provide insight into the various challenges to developing climate-proof cities in Africa and how these challenges can be overcome. The research will also provide enlightenment on how governance structures within cities in the African continent can incorporate sustainable development practices. The approach of embedding environmental sustainability metrics in municipal development plans is not customary practice within the African continent [

7], nor is it an easy exercise that has been implemented successfully. The outcomes of this research could provide new methodologies for managing and operating African cities based on environmental sustainability dimensions. The research outcomes will provide a better understanding of how African countries can mainstream environmental sustainability more effectively in local municipal planning to enhance sustainable development. The research outcomes will contribute to the knowledge of development plans and their implementation in Africa as enablers of sustainable development.

3. Results

This section presents the findings of the research. The first section presents the results of the page-by-page content analysis and thematic coding of the CoT’s IDP, the CoW’s strategic plan, the AMA’s MTDP, and Zambia’s IDP guidelines for the LCC. The objective was to assess how environmental sustainability was integrated into these development frameworks, identify impediments and enablers of sustainability integration, and evaluate the municipalities' performance against the targets set for the 2017-2022 period. The analysis targeted environmentally oriented projects within the development plans to determine how each municipality institutionalised environmental sustainability. The performance of these municipalities during this period was evaluated against the environmental sustainability targets set in their respective plans. The evaluation focused on both the planning and execution stages, analysing whether environmental sustainability-focused projects were implemented after being planned and how resources were allocated. This analysis provided insights into internal and external factors that either facilitated or hindered sustainable development. Specifically, the study examined each municipality’s funding sources, budget allocation processes, and the prioritisation of environmental sustainability projects in the face of competing demands.

The second section presents the findings of the analysis of the development plans against the OECD mainstreaming framework. This framework defines the critical elements required for the effective integration of environmental sustainability into development planning and implementation processes. The assessment focused on how well the development plans of these four cities incorporated and operationalised the mainstreaming principles.

3.1. Results of the thematic content analysis

In examining the development plans, the analysis focused on environmentally orientated projects, projects that focused on how the municipalities institutionalised environmental sustainability into development planning. The analysis assessed whether the environmental sustainability projects were implemented after being planned and how resources were allocated to them. A review of the implemented projects was done to identify internal and external factors that can either facilitate or impede sustainable development. The municipality’s funding sources, and budget allocations were evaluated to determine the way in which funds were allocated to various projects and their prioritisation. Part of the development process of development plans is extensive stakeholder engagement; this is an ongoing process with specific meetings held on an annual basis when the development plans are reviewed, and performance management is conducted. The analysis examined whether engagements occurred with a wide variety of stakeholders, the level and type of engagements conducted, and the frequency of the meetings. A review of existing policies, regulations, and incentives related to environmental sustainability within the respective municipalities was conducted to determine whether there were any regulatory barriers or incentives. An evaluation was conducted to determine institutional capacities by assessing the municipality’s technical capabilities and human resources. This was to assess whether the cities had competencies within their staff to mainstream environmental sustainability. The level of public awareness and education on development planning and environmental sustainability conducted by the municipalities was assessed.

When reviewing the extent to which environmental sustainability had been integrated into the development plans of the four municipalities, the research did not focus on normal service delivery. Projects on waste removal, electricity and water supply were not considered as they form part of basic service delivery and are not regarded as being part of environmental sustainability.

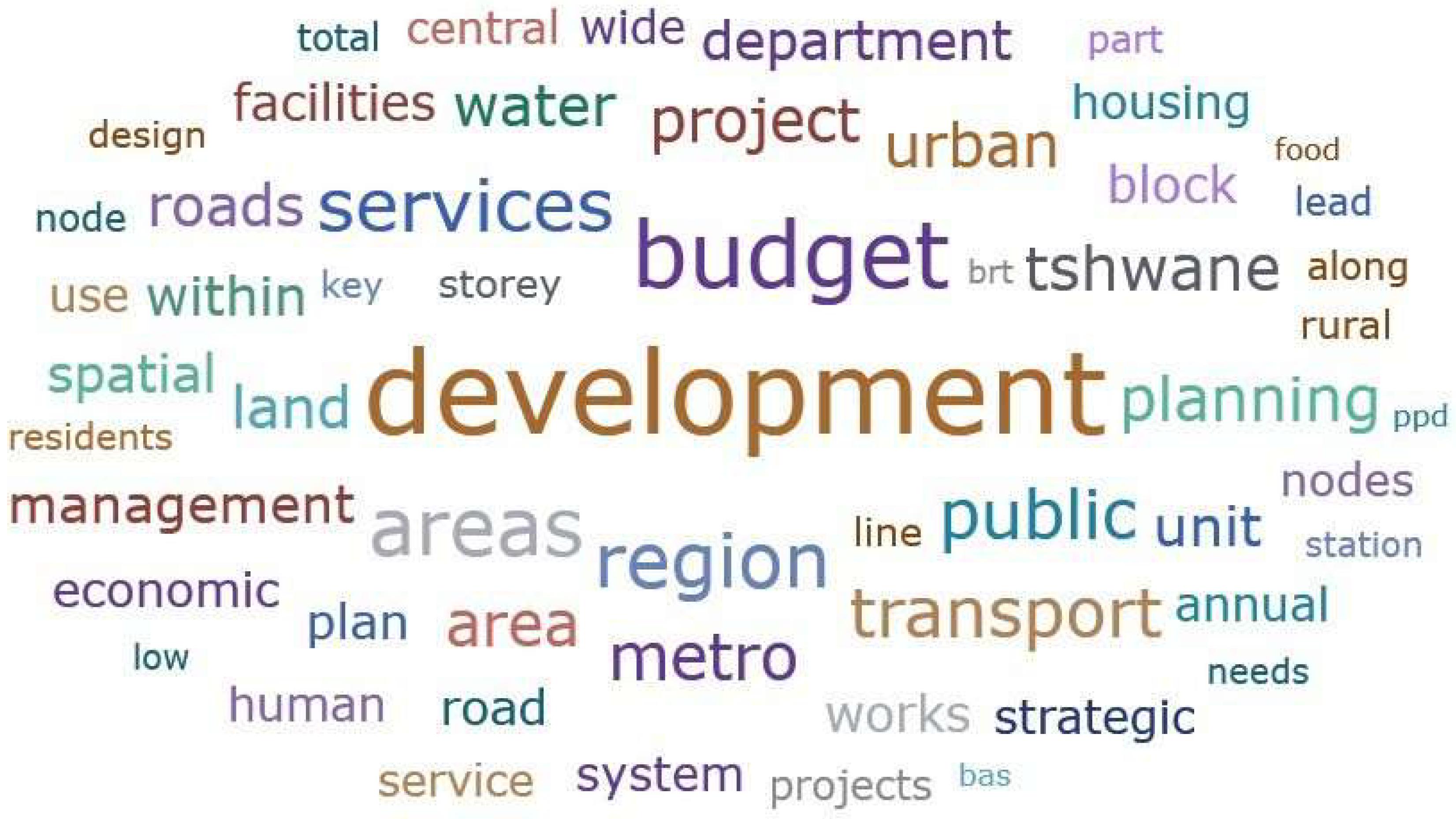

Figure 2 show the frequency of words used in all the development plans. The most frequently used word in the development plans was "development" which is to be expected as these documents are meant to enable development in the respective four cities.

The analysis reveals that the term "ecological" is mentioned nine times in the CoT 2020/2021 SDBIP, once in the AMA MTDP, and not at all in the Zambian guidelines, the CoW strategic plan, and the 2018/2019 CoT SDBIP. Additionally, the word "environmental" appears 76 times in the CoT 2020/2021 SDBIP, three times in the CoT 2017/2018 SDBIP, five times in the CoW strategic plan, 300 times in the CoT IDP, 50 times in the Zambian guidelines, and 97 times in the AMA MTDP. Finally, the term "sustainability" is mentioned twice in the CoT 2017/2018 SDBIP, 16 times in the CoT SDBIP, 22 times in the CoW strategic plan, 70 times in the CoT IDP, and eight times in the AMA MTDP.

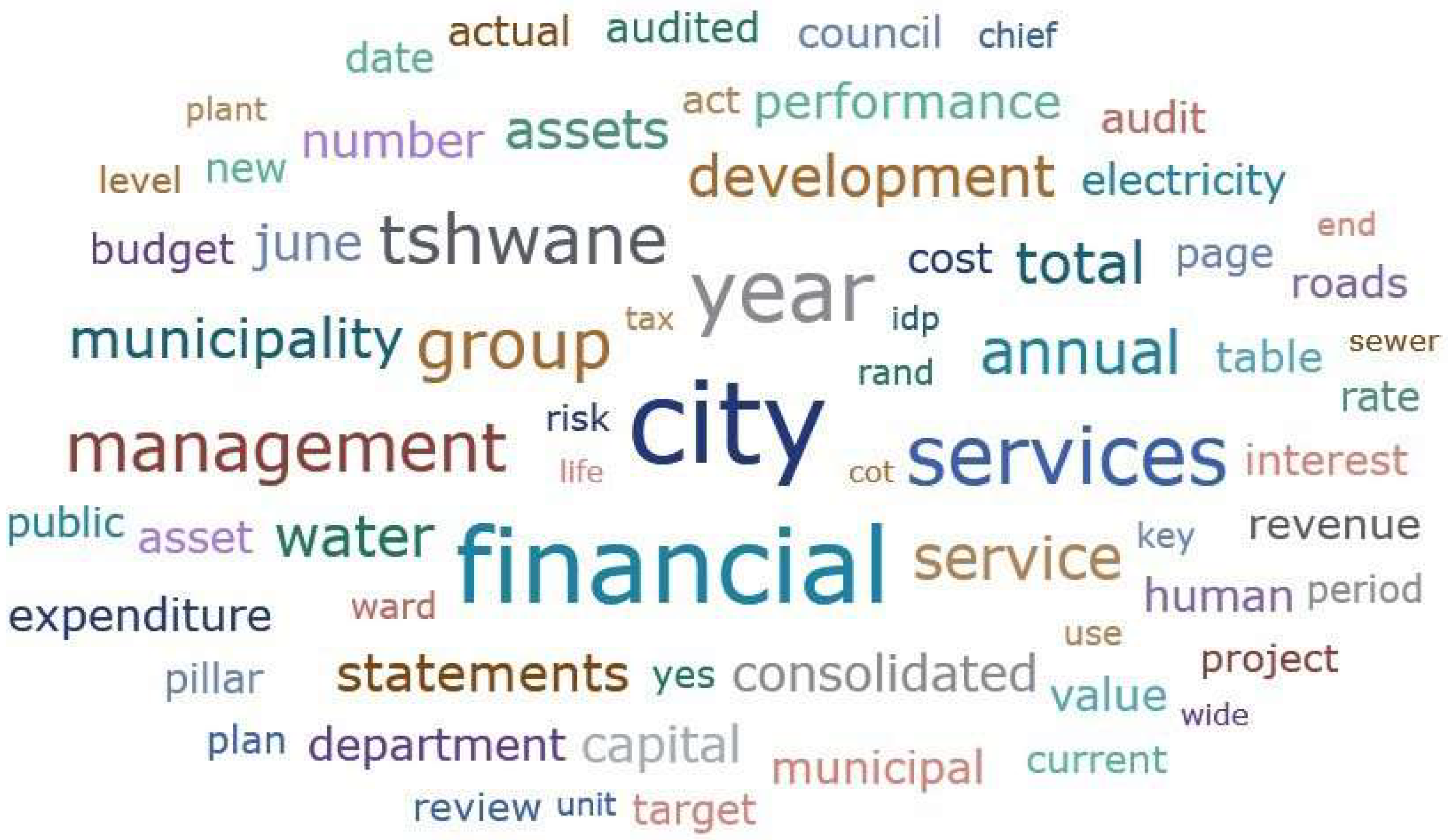

Figure 3 show the frequency of words used in all the annual reports. The words "financial" and "services" are frequently used in the annual reports. It is important to note that the words related to environmental sustainability are not frequently used in the development plans and the annual reports.

The Sankey diagram given in

Figure 4 shows the various themes that were generated from the codes in the development plans of the four cities. The themes that emerged include leadership instability, capacity-building and training, leadership gap, institutional challenges, ineffective supply chain systems, absence of key infrastructure facilities, poor stakeholder engagement, competent skilled municipal staff, governance, staff capacity constraints, partnerships and collaborations, stakeholder participation, poor project management, environmental sustainability awareness-raising, indicative budget, and multidisciplinary development plan team.

3.2. Results of the Analysis through the mainstreaming framework

The OECD framework was used to assess how the four municipalities mainstreamed environmental sustainability into their development plans. When mainstreaming environmental considerations into policies and development plans, the following aspects must be considered: The extent to which environmental sustainability risks have been taken into consideration in the formulation of the specific projects and programmes; and whether the development plans address these risks and offer opportunities for climate-proofing.

3.2.1. Intentionally taking account of environmental concerns and addressing them through specific projects and programmes in the development plan

The CoT was not explicit in addressing environmental concerns through projects. The CoT was aware of the impact of urbanisation and climate change on the environment, but there was a poor reflection of this in addressing it. The CoT listed a few projects that were not implemented. The content analysis shows that the CoT’s IDP mentions the maintenance of biodiversity and resorts, developing a green energy business strategy, reduction of landfill waste, facilitation of renewable energy and waste to energy, drafting a Green Building Development By-law, preventing illegal dumping, and stabilising the waste collection and waste disposal services as some of the main interventions that the city is committed to. However, only the maintenance of biodiversity and resorts is articulated in the actual projects.

The CoW explicitly addressed its water security risks by including the establishment of an additional Direct Portable Reuse Plant (DPRP) and expanding the aquifer recharge scheme in their projects, to address the effects of the drought. The findings show that renewable energy projects were included and implemented and a small-scale embedded generation system for the residents was introduced along with net metering policies.

The findings show that the AMA used the Potential, Opportunities, Constraints and Challenges (POCC) assessment as a tool to analyse the feasibility of implementing its projects identified as per the developmental issues. The POCC analysis is a tool used to streamline development issues and interventions before they are programmed for implementation, which is important to assist in fine-tuning development goals, objectives, policies, and strategies. The resources within the AMA’s access, which could be harnessed to enhance developments in the city, were the potential. The opportunities were other external factors that the AMA could leverage to enhance the development rate. The constraints were internal weaknesses which could impede development, and steps would have to be taken internally to address them. The challenges were external constraints hampering development, which need to be overcome. This enabled a realistic analysis of resources that the AMA had to develop projects to address environmental concerns and implement the MTDP. It enhanced the formulation of appropriate strategies for a more pragmatic plan. The AMA recognised the importance of mainstreaming climate change in their development planning and budgeting processes; they established the resilience advisory council and the climate change and resilience steering committee. In 2020, the AMA developed a comprehensive five-year Climate Action Plan, which indicated that the AMA was serious about its climate and environmental risks. The plan was the second of its kind on the African continent and is fully compatible with the 2015 Paris Agreement [

35]. The AMA plan prioritised decisive action on crucial areas such as solid waste and wastewater, buildings and industry, transportation, and land use and physical planning. This was also to ensure that climate threats are thoroughly considered and addressed in their development processes.

The analysis shows that the Zambian guidelines for IDP planning are explicit on how environmental factors should be incorporated into the IDP. The guidelines state that an assessment of the natural environment's condition as well as the effects and ramifications of population growth, settlement, and industrial development must be done. The guidelines specify that the LCC should address environmental risks and its relationship to economic activities and industrialisation through the IDP.

3.2.2. Allocating resources to environmental sustainability projects, either through municipal budget or sourcing external funding from donors and partners

The results show that the CoT did not prioritise budget allocation to environmental sustainability projects. The projects were planned, however, it can be seen in the annual reports that they were not implemented due to the lack of budget allocation. In 2019, the CoT planned to build a waste-to-energy plant; however, resources were not allocated for this project. The CoT intended to build a bicycle lane in the 2018/2019 fiscal year, but no funding was provided for the project in that year. The city subsequently set aside R10 000 000.00 for 2019/2020 and 2020/2021, respectively; however, the project was not implemented as funds were not allocated. According to the findings, the installation of gabion structures and oxygen traps as part of the wetland rehabilitation project was scheduled to begin in the third quarter of 2018. However, the 2020/2021 SDBIP reveals that the CoT was still busy conducting procurement processes.

The CoW was intentional about allocating a budget to its strategic objectives, programmes, initiatives, and projects. They also accessed funding from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) to ensure they could successfully implement the environmental sustainability projects they had planned due to the limitations of the municipal budget.

The findings show that when AMA was planning its MTDP budget, the estimated costs included all mitigation measures that would be adopted to ensure sustainability. The budget needed to successfully implement the MTDP was R6.4 billion which was sourced from internally generated funds, donor funding and funds from the national government. The analysis shows that AMA allocated R5.5 billion to the environment sustainability programmes.

Although the guidelines for Zambia reiterate that the activities in the planning process of the IDP should be conducted cost-effectively, there is no reference to prioritising budget allocations to environmental sustainability projects.

3.2.3. Implementation of the environmental sustainability projects and programmes

The results indicate that the CoT tried to prioritise the green economy and preserve ecological infrastructure and ecosystems in the 2019/2020 fiscal year, putting more of an emphasis on environmental sustainability than on the routine waste disposal and water treatment projects the city conducted as part of its regular services. The CoT only enhanced the atmospheric pollution monitoring network in that fiscal year as part of its targeted environmental sustainability projects. The CoT had intended to build a multimodal rubbish transfer facility in 2018; however, it was never implemented. The CoT used the DMRE's energy efficiency and demand side management funding to convert two hundred standard streetlights to light-emitting diode (LED) fixtures and fenced three nature reserve spruit areas during the 2018/2019 fiscal year. The CoT planned to build an agricultural park in Soshanguve in 2020–2021, but this project was never conducted because no funding was provided. The project was moved to the 2021/2022 fiscal year, with a R6 500 000.00 allocation for that year and an additional R6 500 000.00 for 2022/2023. However, the implementation of this project cannot be assessed as the 2022/2023 fiscal year falls outside the scope of this research. The CoT annual reports indicate poor implementation of environmental sustainability projects while prioritising the rehabilitation of wetlands in the Centurion area and fencing nature reserves.

The annual reports show that the CoW implemented the environmental sustainability projects as planned in the five-year term of the strategic plan. From the findings, it is clear that to lessen its dependency on the national utilities, the CoW launched energy and water initiatives. The CoW increased the capacity of its aquifer recharge scheme to allow for adaptation to variations in rainfall and temperature. This included storing water underground to prevent evaporation during high rainfall years and preserving it, along with treated water, for years when rainfall was insufficient. By using net metering for small-scale embedded generation, the CoW encouraged its citizens to use renewable energy sources. To include renewable energy sources in the city's electrical networks, the city built a waste-to-energy plant as well as solar and wind power facilities. The CoW established a second facility for the direct potable reuse of treated wastewater as a means of enhancing the region's water security. As part of the shift to using more environmentally friendly energy sources, the CoW also created a policy on renewable energy.

The annual reports show that AMA implemented energy efficiency projects by conducting energy audits and implementing the recommendations following the energy audits. To construct a sanitary landfill site, the AMA secured two hundred acres of land. Through the SMART school initiative, the AMA installed solar panels, biogas digesters and boreholes at schools they constructed. Strategies on cleaner production and consumption technology and practices were also adopted, as well as promoting waste recycling and waste-to-energy technologies. As part of its resilience strategy, the Accra Greening and Beautification Project was initiated in collaboration with private companies; the AMA partnered with the Department of Parks and Gardens, Ecobank Ghana Limited, Ghana Commercial Bank and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who funded the initiative. The project was launched in 2018 to green the open spaces within Accra. The AMA dredged three of its lagoons to increase the storage capacity of the reservoirs for water security and to prevent flooding. In addition, the AMA implemented a training programme to educate fifty vegetable farmers on green labelling and certification. This assisted farmers to attain certification which is an indication of the way in which the environmental impacts of their products are taken into consideration, and they created sustainable values for consumers as well as for the whole society which is in line with sustainable development. This project not only focused on the environmental aspects, but it created income generation for farmers and gave them access to new markets. The annual report details how AMA planted 250 000 trees per year and planted grass in open spaces to mitigate erosion.

3.2.4. Informing and influencing decision-makers through awareness-raising, stakeholder engagements and regular meetings

The annual reports show that the CoT had annual air quality environmental education and awareness sessions at several schools and communities as well as a pre-winter awareness campaign to curb air pollution, particularly for informal settlements. However, the findings of the content analysis show little engagement of the CoT in matters of environmental sustainability engagement with other IDP stakeholders, e.g., NGOs, civil society, and businesses.

The analysis shows that CoW sought input from a broad and diverse stakeholder network during the planning process for the 2017-2021 Strategic Plan, including the city’s administrative and technical staff, administrative and political representatives of the Khomas Regional Council and the city’s councillors. This approach was to ensure a collaborative planning process. The strategic plan states that the CoW considers community participation to be a key component in the implementation of its strategic plan. The CoW’s strategic plan states that “public participation promotes understanding of residents' expectations, improves the public's understanding of the city’s responsibilities, and ensures better compliance through greater ownership of a solution.’’ It goes on to say that “public participation is the cornerstone of responsive, inclusive, and caring city government because it empowers communities to best participate in issues that affect them. It also builds consensus for action on complex issues." Regular meetings were held with members of the community and stakeholders. The annual report indicates that the CoW scheduled two cycles of citizen engagement meetings, twenty-six meetings per cycle and additional meetings as needed, annually in all ten of the city's constituencies. The analysis shows that to improve participation and feedback, CoW adapted the methods of engagement and communication, recognising that different circumstances require different communication platforms. In the event of conflict, resources were made available for mediation to ensure that trust in the communities was restored.

In the development of the 2018-2021 MTDP, the AMA included community engagement sessions and stakeholder meetings where developmental issues were discussed. One of the twenty-eight primary issues identified was environmental pollution; however, this issue was not addressed from the climate risk perspective. The findings show that the AMA held nine resilience stakeholder meetings, of which four were with resilience organisations, four were for the preparation of the resilience strategy, and one was a dissemination workshop where the resilience strategy was presented and shared with stakeholders. The AMA held awareness-raising workshops to educate its residents on the hazardous effects of noise pollution by night clubs in the metropolis and on waste management and disposal. The annual reports reflected capacity-building training programmes that were organised for solid waste collection contractors. A dissemination and communication strategy was developed by the AMA as guidance on updating its stakeholders on the progress made in implementation through various channels. Through this strategy, the AMA used panel discussions, town hall meetings, community engagements and written material to disseminate information to its various stakeholders. The AMA also held numerous workshops for resilience sensitivity for community members to conscientise them on environmental issues. The analysis shows that the AMA conducted community engagements on proper disposal of waste and waste separation at source. Annually, the AMA organised seminars, training programmes and workshops on disaster prevention and specific workshops for community members in flood-prone areas.

The content analysis shows that the guidelines place a strong focus on community involvement and stakeholder engagement as an essential aspect of Zambia's IDP implementation. The guidelines emphasise how the LCC should explore different platforms for interaction, develop a participation strategy, and involve the community and stakeholder organisations in every stage of the IDP process. The findings show that, according to the guidelines, the LCC must take into consideration the best available channels for public input and ensure that all relevant stakeholder groups are represented.

3.2.5. Monitoring and evaluation of the implemented projects and programmes

The findings show that monitoring and evaluation programmes were in place in CoT, however, monitoring and evaluation was poorly implemented in the CoT.

The CoW introduced a Quality Process Results (QPR) tool, a management system to assist in monitoring progress on the performance of the implementation of the strategic plan and quarterly reporting on the implementation was also introduced.

During the implementation of the 2014-2017 MTDP, the AMA experienced some challenges and part of the lessons learnt from that term was to incorporate a rigorous monitoring and evaluation plan into the 2018–2021 MTDP. From 2018 onwards, the AMA implemented a result-based monitoring and evaluation programme with systems to assist the municipality in assessing the size of financial budgets as well as the extent of resource commitment needed to complete projects, so they could monitor the progress made in the implementation of the MTDP and review their performance. The findings show that ten district cleansing officers and five other waste management department staff members were trained in results-based supervision monitoring and evaluation, and the AMA conducted several site visits and held stakeholder meetings to monitor the progress of the projects and programmes. The annual reports indicate that monitoring and evaluation were conducted at various levels, with the AMA involving members of the town/zonal council, assembly members, traditional authorities, women and youth representatives, religious leaders, unit committees and representatives of non-governmental/community organisations to oversee specific local projects. This helped to create a sense of ownership of the projects and to keep these stakeholders informed of progress through participatory monitoring and evaluation processes. At the assembly level, the various departmental teams conducted monthly site visits to collect data and receive input from the communities.

Although the Zambian guidelines do not detail how monitoring and evaluation should be implemented, a chapter on mainstreaming climate change into the IDP is included in Volume 1, which are the guidelines on undertaking the planning survey and preparing the issue report. Part of the mainstreaming process is to develop a framework of indicators and outputs that appropriately monitors progress towards reducing risk and building resilience as well as indicators linked to key projects. This suggests that the LCC will have a framework for monitoring and evaluating its progress toward implementing the IDP.

5. Conclusions

The study reveals that all four African cities faced constraints in financial resources, human capital, technology, and expertise, limiting their ability to incorporate environmental sustainability into development plans. The CoW and the AMA demonstrated more effective implementation of environmental sustainability initiatives due to strong leadership, environmental champions, and robust institutional capacity. Despite the persistent challenges of financial constraints and limited human resources, the CoW and the AMA leveraged partnerships and knowledge networks to mitigate these limitations. Effective development plans can drive sustainable development; however, inadequate implementation, bureaucratic structures, and a lack of support hinder their potential. Integrating environmental sustainability into development plans is essential for achieving long-term, sustainable growth. Prioritising social, environmental, and economic factors can help cities foster development that is both profitable and beneficial to communities and the planet. Furthermore, a focus on environmental sustainability is crucial to building climate-resilient cities that can better withstand the impacts of climate change, which have led to frequent natural disasters in Africa [

55,

56]. Environmental sustainability integration requires a comprehensive and evolving approach, regularly reviewing and updating project implementation. Monitoring and evaluation with clear indicators are essential for tracking progress and addressing challenges [

37,

57]. The research highlights the CoW and the AMA’s prioritisation of environmental sustainability, addressing water and energy security risks, and promoting socio-economic development. In contrast, the CoT did not prioritise environmental issues, focusing instead on providing basic services and infrastructure, neglecting a long-term perspective on climate resilience [

58]. The CoT’s development plan includes a regional spatial framework for sustainability but lacks clear implementation strategies and practical environmental projects, reflecting systemic bureaucratic inertia that hampers innovative planning and sustainability inclusion [

37].

Key enablers for successfully incorporating environmental sustainability into development plans include strong political leadership, regular stakeholder engagement, capacity-building for municipal staff, inter-governmental alignment, integrated planning, and the setting of clear, measurable goals [

50]. Incentives, regulations, collaboration, and partnerships further support these initiatives, helping cities leverage external expertise and resources. A long-term multifaceted perspective is critical, ensuring that decisions made today foster resilience and sustainable development in the future. Regular monitoring, evaluation, and research, using accurate data, are fundamental for effective planning and decision-making [

59,

60,

61].

Environmental sustainability can only be successfully integrated into development plans by addressing the above factors, with an emphasis on leadership, long-term vision, and partnerships. The research and other research studies by Ruwanza & Shackleton, [

62] and Shearing & Pasquini, [

45] confirms that while the selected African cities acknowledge the impact of climate change, they have yet to fully mainstream environmental sustainability into their operations. A balance between addressing immediate needs such as access to water and energy and long-term ecological resilience is essential. This aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which require a holistic and integrated approach to development [

63]. Urban planning plays a crucial role in achieving transformational adaptation, addressing fundamental causes of sustainability risks, and requiring systemic changes in city planning and development [

61].

Achieving sustainable development goals remains a complex challenge for African cities, as they grapple with energy, water, and food security while protecting ecosystems and vulnerable communities from the environmental consequences of industrialisation and development[

64,

65,

66]. This research and research by Sachs [

55] and Allen et al., [

56] emphasise the need for innovative, evidence-based solutions to meet both immediate needs and the long-term sustainability objectives outlined in the SDGs