Highlights

A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was successfully created to diagnose monkeypox by combining patient symptoms with high-definition skin lesion images.

The model achieved a balanced accuracy of 82%, an F1-Score of 84%, and showed high sensitivity (80%) and specificity (85%), demonstrating its effectiveness in distinguishing monkeypox from other similar illnesses.

The hybrid approach of combining clinical data and visual information significantly improved diagnostic accuracy, highlighting the model's potential in resource-limited settings.

The model shows promise as a reliable tool for early detection and response in future monkeypox outbreaks and other emerging infectious diseases.

1. Introduction

The monkeypox virus, which causes the zoonotic illness, has become a major public health problem in recent times, especially in areas where the virus is not typically prevalent. The illness, which is closely linked to smallpox, causes fever, headaches, pains in the muscles, and a characteristic rash that develops into many phases before crusting and curing [

1]. Even though monkeypox is often less deadly than smallpox, it can nevertheless result in life-threatening complications, particularly in those with compromised immune systems or in places with poor access to medical treatment. It is essential to diagnose monkeypox as soon as possible to treat the illness effectively, stop further infections, and provide prompt treatment [

2]. The clinical appearance of monkeypox can mimic other pox-like disorders, including chickenpox, smallpox, and different viral exanthems, making the diagnosis process frequently difficult [

3]. Due to the historical rarity of monkeypox, these similarities may cause delays or mistakes in diagnosis, especially in areas where healthcare personnel may not be as familiar with the disease. Even if they are reliable, traditional diagnostic techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing take time and may not always be available, especially in outbreak conditions where quick diagnostics are essential[

4].

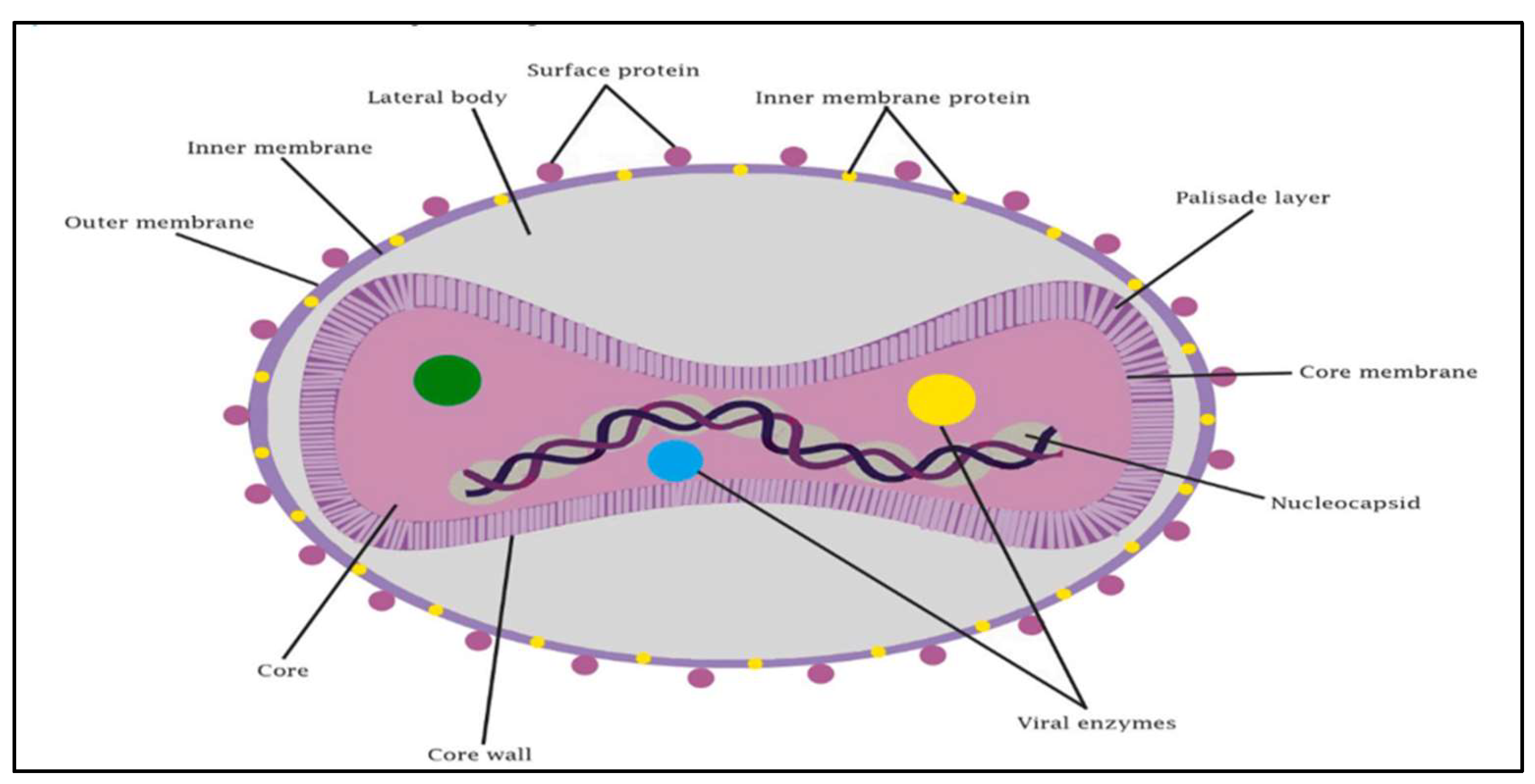

Figure 1.

Illustration of monkeypox virus [

5].

Figure 1. provides a thorough schematic illustration of the structural parts that make up the monkeypox virus, emphasizing several crucial components that are necessary for both its pathogenicity and functionality [

6]. The DNA genome, which contains the genetic information required for both replication and pathogenicity, is the central component of the virus. The core membrane and core palisade layer, which encircle the genome, gives viral DNA stability and protection. It is believed that the lateral bodies, which are next to the core, contribute to the early phases of infection by introducing vital viral proteins or enzymes into the host cell. Both an inner and an outer membrane envelop the virus, aiding in its interaction and defense within the host environment.

Figure 1.

Illustration of monkeypox virus [

5].

Figure 1. provides a thorough schematic illustration of the structural parts that make up the monkeypox virus, emphasizing several crucial components that are necessary for both its pathogenicity and functionality [

6]. The DNA genome, which contains the genetic information required for both replication and pathogenicity, is the central component of the virus. The core membrane and core palisade layer, which encircle the genome, gives viral DNA stability and protection. It is believed that the lateral bodies, which are next to the core, contribute to the early phases of infection by introducing vital viral proteins or enzymes into the host cell. Both an inner and an outer membrane envelop the virus, aiding in its interaction and defense within the host environment.

Rashes on the skin develop in 3–8 days when monkeypox occurs [

7]. Rashes frequently start out on the face before spreading to other areas of the body. Lesions in the eyes, intraoral mucosa, and vaginal region are also visible in certain individuals. This illness might be misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to rashes caused by chickenpox[

8]. These rashes start off as blisters filled with water, but they eventually become crusty areas that start to heal. While fewer blisters appear in some people, other patients have lesions that involve hundreds of pimples that extend throughout their bodies [

9]. In severe situations, the lesions may combine to produce widespread rashes on the skin's surface.[

7]

1.1. Broader Applications of Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Diagnostics

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated significant potential in the diagnosis of various diseases beyond monkeypox, showcasing their versatility in medical imaging and symptom analysis. The success of CNNs in disease diagnosis stems from their ability to automatically learn and extract features from high-dimensional data such as medical images, reducing the need for manual feature selection and improving diagnostic accuracy. Below are key areas where CNNs are making strides in disease diagnosis:

Cancer Diagnosis: CNNs have been widely applied in cancer detection, particularly in the analysis of medical images such as mammograms, histopathology slides, and computed tomography (CT) scans. For instance, CNNs have achieved high accuracy in breast cancer detection through mammogram analysis, significantly aiding in early diagnosis [

10]. In histopathological image analysis, CNNs can distinguish between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues, with applications in lung, colorectal, and prostate cancer [

11].

Cardiovascular Disease: In cardiovascular imaging, CNNs have been employed to detect conditions such as arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, and heart failure from electrocardiograms (ECGs), echocardiograms, and cardiac magnetic resonance images. CNN-based models can automate the identification of abnormal heart rhythms and structural heart diseases, improving the speed and accuracy of cardiovascular diagnostics [

12].

Neurological Disorders: CNNs are also used in the diagnosis of neurological conditions, including Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and epilepsy. For example, CNNs have been applied to brain MRI scans to detect early signs of Alzheimer’s disease by identifying patterns of brain atrophy [

13]. In epilepsy, CNNs are used to analyze electroencephalogram (EEG) data, improving the detection of seizure activity [

14].

Retinal Diseases: In ophthalmology, CNNs have been successful in diagnosing retinal diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma by analyzing retinal fundus images. These models offer the potential to screen large populations for retinal diseases, particularly in regions where access to specialists is limited [

15].

Pulmonary Disease: CNNs have also been applied in diagnosing pulmonary conditions, such as pneumonia and COVID-19, using chest X-rays and CT scans. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CNNs were employed to differentiate between COVID-19 and other lung diseases, providing a fast and accurate diagnostic tool to support overwhelmed healthcare systems [

16].

Skin Disease Classification: Beyond monkeypox, CNNs are widely used in dermatology for the classification of skin diseases such as melanoma, psoriasis, and eczema. These models can classify skin lesions with accuracy comparable to dermatologists, making them valuable for early detection and treatment planning [

10].

1.2. Common Machine Learning Techniques Used in Monkeypox Detection

To diagnose monkeypox, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is now thought to be among the most effective techniques. Visual inspection of skin lesions and rashes is often used to diagnose pox infections. The skin lesions and rashes caused by monkeypox may resemble those of cowpox and chickenpox. Smallpox and monkeypox have comparable clinical signs, with the former being less severe. Early diagnosis of monkeypox can be challenging for medical experts due to clinical and visual similarities between the illnesses. The use of computer-assisted diagnosis to help doctors in a variety of challenging circumstances has grown in recent years [

17]. We treat this as a classification job in the current work. Here, a picture is often fed into the system, which processes it and labels it with a class based on the requirements. These days, deep learning-based methods are often applied in the field of medical image processing since they are superior to manually constructed feature extraction-based methods [

18]. These methods consist of two parts: the extraction of features and the categorization of those characteristics. Features are extracted using convolution processes, and then they are classified using multi-layered neural networks.

We note that the literature has some first suggestions for addressing the difficulties in the field of medical image processing. Specifically, some pilot research has been conducted in this field [

19]. However, most of the time, deep learning-based architecture as they are described in the literature does not offer ultimate dependability [

20]. Certain techniques are meticulously adjusted for certain assignments. In the feature extraction section, most of these techniques are designed to extract improved feature maps [

21]. Medical image processing is a delicate subject since a false diagnosis is never acceptable. Rare illnesses like monkeypox are impacted by inadequate diagnostic techniques.

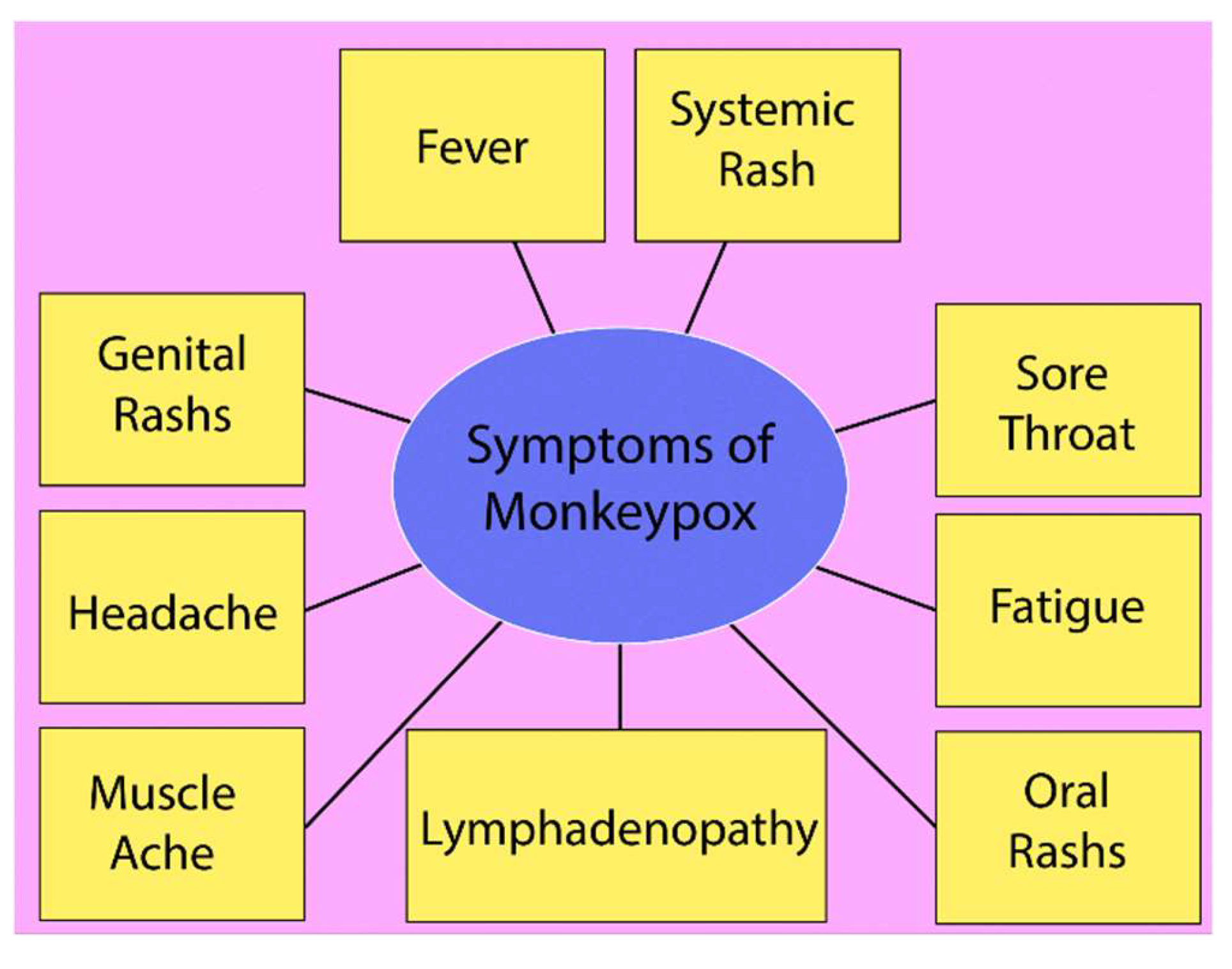

Figure 2.

Significant symptoms of monkeypox disease.

Figure 2.

Significant symptoms of monkeypox disease.

In this work, we provide a thorough method based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for the detection of the monkeypox virus via sophisticated machine learning techniques. Using CNNs, which are well-known for their ability to recognize images, we have created a model that can correctly identify monkeypox infections. The incorporation of a solid dataset consisting of nine unique symptoms usually linked with monkeypox into the CNN model's prediction framework is a crucial component of our strategy. Our research differs from other studies in that it includes symptoms, which improve the model's capacity to produce more accurate and trustworthy diagnoses. This combined method advances the use of machine learning to address public health issues significantly while also increasing detection accuracy. By doing this research, we want to improve healthcare outcomes by helping to control monkeypox epidemics in a timely and efficient manner.

2. Materials and Methods

The research made use of an already-existing dataset that included high-definition photos of skin lesions linked to monkeypox in addition to a comprehensive log of nine distinct symptoms: rectal pain, sore throat, penile edema, oral lesions, solitary lesion, enlarged tonsils, HIV infection, and STDs. Based on their proven prevalence and diagnostic value in confirmed instances of monkeypox, these symptoms were chosen. Several tools and software platforms were utilized to develop monkeypox prediction system. The main programming language utilized to create the machine learning models was Python 3.10. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models were constructed and trained using the Keras framework, which was built on top of TensorFlow. TensorFlow managed the deep learning model optimization and processing, while Keras offered a user-friendly and adaptable API for creating intricate models.

2.1. Datasets and Symptom Analysis

It was decided to use a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to categorize skin lesions as either symptomatic of monkeypox or not. To increase the robustness of the model, preprocessing steps such as picture scaling, normalization, and data augmentation were added to the training set of labelled images [

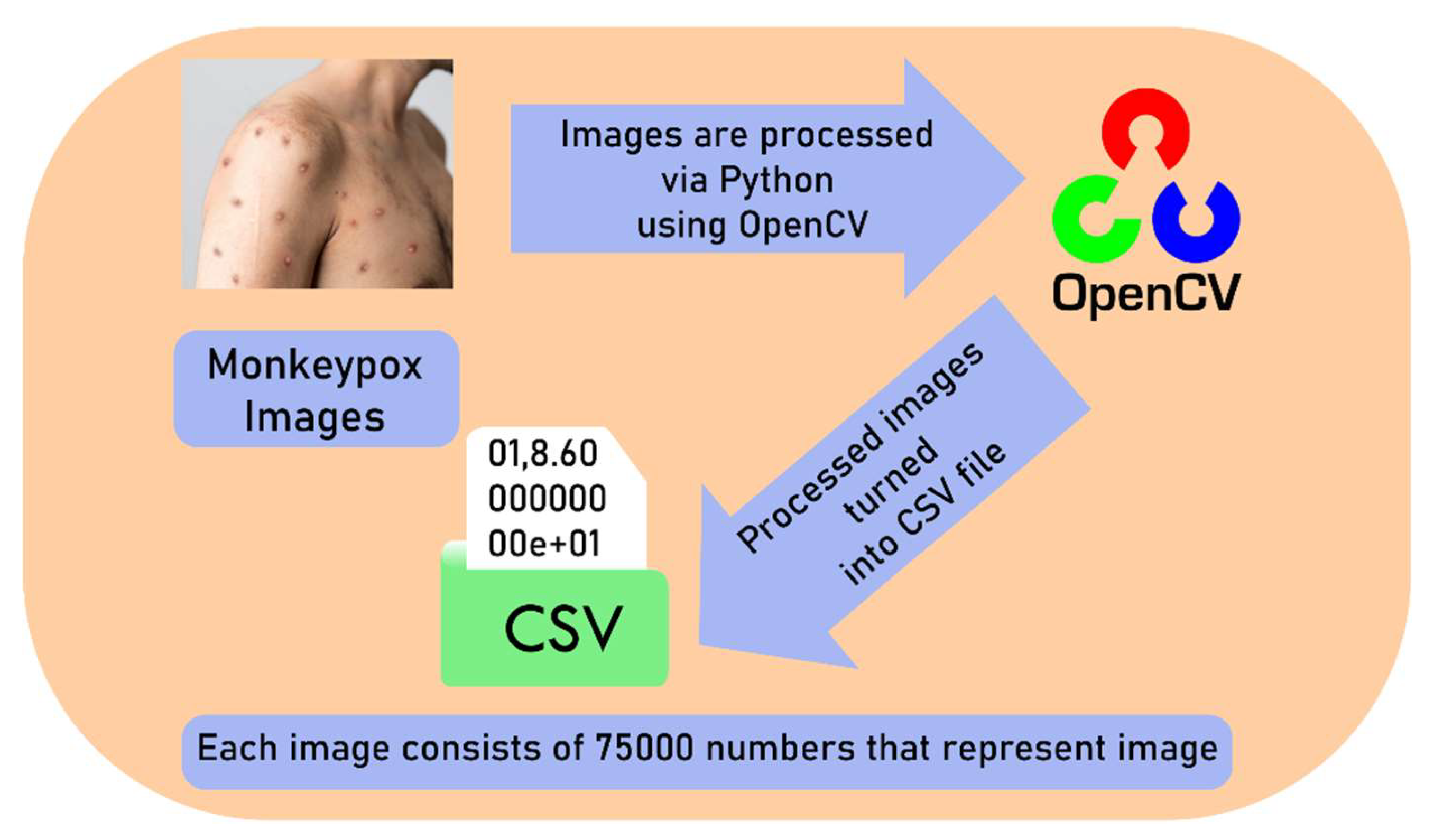

20]. The image dataset consists of 200 monkeypox images. 40 of them were used to testing the CNN model’s performance and 160 of them were used for training the model. After modelling, this image number enhanced to 2000. CNN architecture was built using many convolutional layers, max-pooling, and fully linked layers that were all Adam optimizer-optimized. A probabilistic score representing the probability that a certain lesion picture was connected to monkeypox was produced by the model. After resizing each image to 100 by 100 pixels, OpenCV was used to transform each one into a one-dimensional array of pixel values. After that, the array with the flattened pixel data was saved as a CSV file for later processing. To speed up training, the pictures were normalized by scaling pixel values to the interval [0, 1]. Following the conversion procedure, each file was combined into a single file to form the CNN dataset.

Figure 3.

Process of creating CSV dataset using monkeypox images.

Figure 3.

Process of creating CSV dataset using monkeypox images.

Monkeypox symptoms typically begin with a fever, often accompanied by other systemic signs like fatigue and headache. Fever is one of the earliest manifestations, signalling the immune system's response to the viral infection. Lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes) is a distinguishing feature of monkeypox, unlike other similar viral infections like smallpox. It commonly presents in the neck, armpits, and groin, indicating the body's immune activity against the virus. A systemic rash, developing after fever onset, progresses through stages from macules to pustules, often spreading across the face, limbs, and trunk. Genital rashes, which occur in a significant number of cases, have been increasingly reported, particularly in sexually transmitted instances, highlighting the virus's spread through intimate contact. Oral rashes and lesions also commonly occur, further complicating the disease by causing sore throat and difficulties in eating. Muscle aches, or myalgia, are another prominent symptom, reflecting the systemic viral impact on the musculoskeletal system, often leaving patients fatigued and physically weakened. The combination of these symptoms, particularly when presenting simultaneously, is crucial for identifying monkeypox early and differentiating it from other pox-like diseases. The CNN prediction was supplemented by an analysis of the patient’s symptoms dataset that we used [

21]. From the source of WHO, there are 36,478 cases that have several symptoms that we used to assist CNN models. The diagnosis depended on the presence of current symptoms that are stated below [

23].

Fever: It is often the initial symptom of monkeypox, appearing in the early stages of infection. It typically indicates the body's immune response to the virus, signaling that the immune system is actively fighting off the pathogen. The fever may be accompanied by chills and is a critical marker for healthcare providers in diagnosing monkeypox, as it can help differentiate it from other illnesses. The duration of the fever can last several days, during which the virus spreads throughout the body, laying the groundwork for subsequent symptoms.

Systemic Rash: The systemic rash associated with monkeypox is a defining characteristic of the disease. It usually manifests within 1 to 3 days after the onset of fever and progresses through various stages, beginning as macules and evolving into pupils, vesicles, and pustules. This progression is significant, as the rash can cover extensive areas of the body, including the face, palms, and soles, indicating the systemic nature of the infection. The rash's appearance and evolution are crucial for clinicians in confirming monkeypox, distinguishing it from similar conditions like chickenpox or smallpox.

Genital Rashes: In recent outbreaks, genital rashes have emerged as a notable symptom, particularly in cases of sexually transmitted transmission. These rashes may manifest as painful lesions or sores in the genital region and can be accompanied by other symptoms such as dysuria (painful urination) or rectal pain. The presence of genital rashes emphasizes the importance of considering monkeypox in differential diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as it highlights the virus's potential for transmission through intimate contact. This symptom is critical for public health messaging and risk assessment in affected communities.

Lymphadenopathy: Lymphadenopathy, or swelling of the lymph nodes, is another significant symptom of monkeypox. This occurs as the immune system responds to the viral infection, leading to an accumulation of lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) in the lymph nodes. Unlike other viral infections such as chickenpox, lymphadenopathy in monkeypox can be widespread and may occur in multiple regions, including the neck, armpits, and groin. This symptom is particularly important for healthcare providers, as it can help confirm a diagnosis of monkeypox during the clinical assessment.

Fatigue: It is a common symptom that often accompanies other systemic symptoms, such as fever and headache. This pervasive tiredness results from the body’s energy being redirected towards fighting off the infection. In monkeypox, fatigue can be profound, affecting daily activities and overall quality of life. The presence of fatigue can serve as an indicator of the illness's severity and may persist even after other symptoms are resolved, necessitating careful management of patient care.

Headaches: It associated with monkeypox can range from mild to severe and may be a direct consequence of the body's inflammatory response to the viral infection. This symptom often occurs alongside fever and other systemic signs, contributing to the overall feeling of malaise. The presence of headache can assist clinicians in identifying monkeypox, particularly when considered in conjunction with other characteristic symptoms.

Muscle aches: Muscle aches, or myalgia, are frequently reported in monkeypox cases and are part of the systemic inflammatory response. This symptom can significantly contribute to the patient’s discomfort and may be exacerbated by fever and fatigue. Muscle pain serves as another indicator of the body’s immune response, assisting in the differentiation of monkeypox from other infections.

Sore throat: A sore throat can occur in monkeypox, particularly when there are oral lesions present. This symptom may lead to difficulties in swallowing and eating, further complicating the patient's condition. The presence of a sore throat is relevant for diagnosis, as it can signal the spread of the virus to mucosal surfaces, underscoring the systemic nature of the infection.

Oral rashes: They are a less well-known but significant symptom of monkeypox. These lesions can lead to painful swallowing and contribute to systemic symptoms like fever and fatigue. The occurrence of oral rashes indicates the extent of the viral infection and provides critical information for healthcare providers assessing the disease's progression. Identifying oral lesions can also be crucial for distinguishing monkeypox from other diseases that present similar symptoms, such as herpes simplex virus infections.

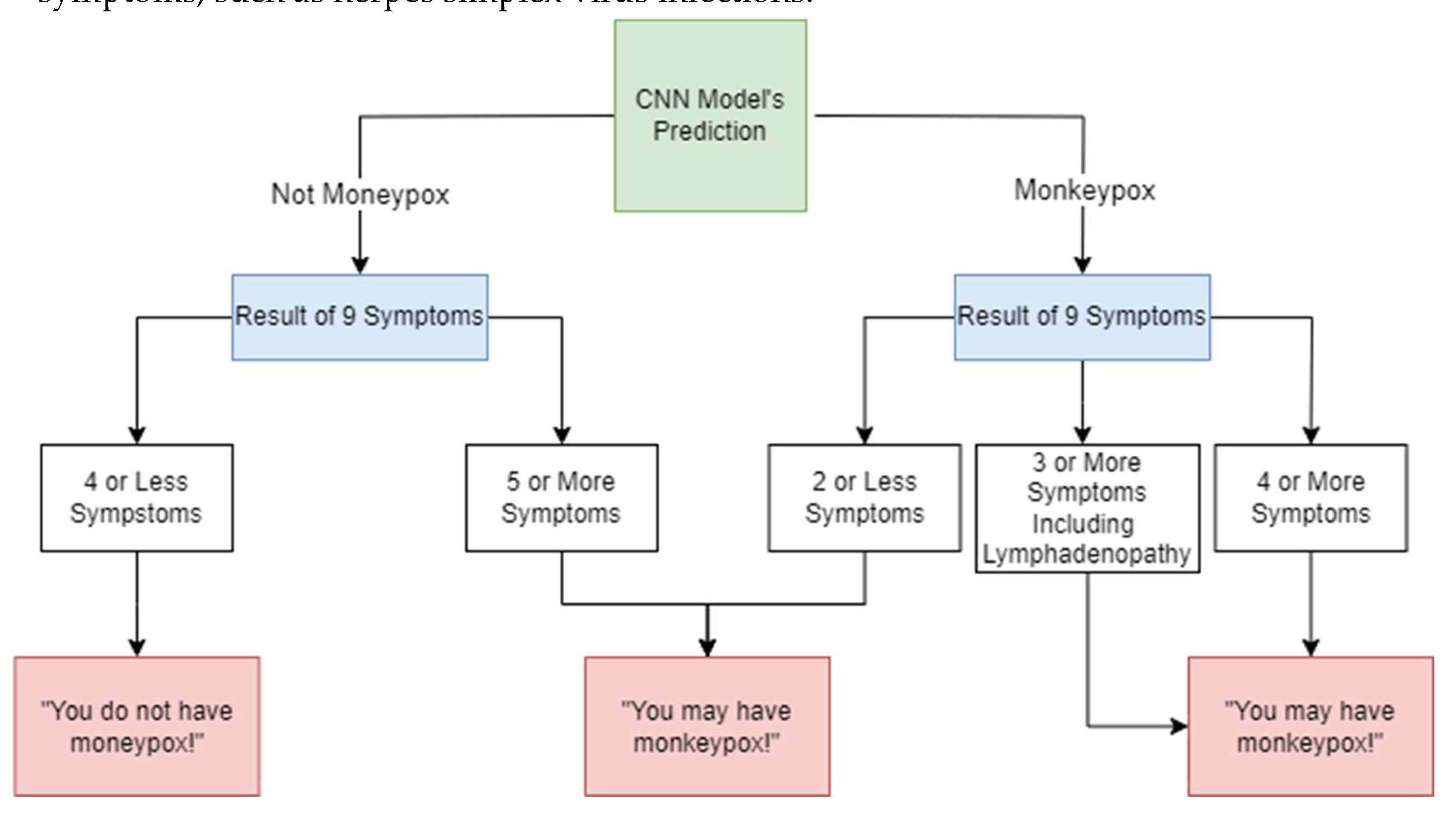

Figure 4.

Workflow of monkeypox detection system.

Figure 4.

Workflow of monkeypox detection system.

By combining CNN’s image-based detection with the clinical presence of these symptoms, this technique increases diagnostic reliability. This reflects WHO's recommendation to consider clinical and epidemiological factors, particularly when visual signs alone may be insufficient, as atypical rashes or early stages of the disease can complicate diagnosis [

22]. For cases where the CNN prediction was under 50%, the presence of five or more of the listed symptoms led to a classification of "possible monkeypox." Otherwise, the patient was considered not to have monkeypox. If the CNN model predicts monkeypox and there is lymphadenopathy along with at least two other symptoms (e.g., fever, systemic rash, or headache), model classifies the case as monkeypox. If the CNN model predicts monkeypox and 4 or more symptoms are present, again model classifies the case as monkeypox. If the CNN predicts monkeypox but less than two additional symptoms are present, and lymphadenopathy is absent, the model should suggest the patient may have monkeypox, prompting further clinical investigation or testing to confirm.

2.2. Machine Learning Model

To categorize the scaffold tissue photos as biocompatible or non-biocompatible, CNN was used. The Keras API provided by TensorFlow was used to implement the network. A picture with three RGB color channels, measuring 100 by 100, is sent into the network. Two convolutional layers, each with multiple filters and a 3x3 kernel size, are present in the model. The model was able to acquire intricate patterns by introducing non-linearity through the application of the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function. A max-pooling procedure with a 2x2 pool size was applied after every convolutional layer. The network may learn more abstract representations of the input data thanks to this procedure, which decreases the spatial dimensionality of the feature maps. Flattened into a 1D array, the output of the last max-pooling layer was used as the input for the fully linked (dense) layers. To forecast the binary outcome of biocompatibility, a dense layer with several neurons and ReLU activation was employed, succeeded by an output layer with a single neuron and a sigmoid activation function. The likelihood that the scaffold tissue will be biocompatible is represented by a single output, which ranges from 0 to 1, in the final layer. With accuracy serving as the evaluation metric, the model was assembled using the Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy as the loss function. Using the training dataset, the network was trained over several epochs with a batch size. To evaluate the model's performance during training, the accuracy and loss were tracked. The model was assessed using a different test set after training. To evaluate the test pictures, predictions were made and compared to the labels that were based on the ground truth. A test image was chosen at random for viewing, and the model's prediction was written next to the picture. A confusion matrix and a classification report, which included information on the model's precision, recall, and F1-score, were used to further assess the overall performance. Accuracy and loss plots were used to display the training process and show the model's performance over the training epochs. Matplotlib was used to create these charts, which give a clear picture of the model's learning curve.

3. Result

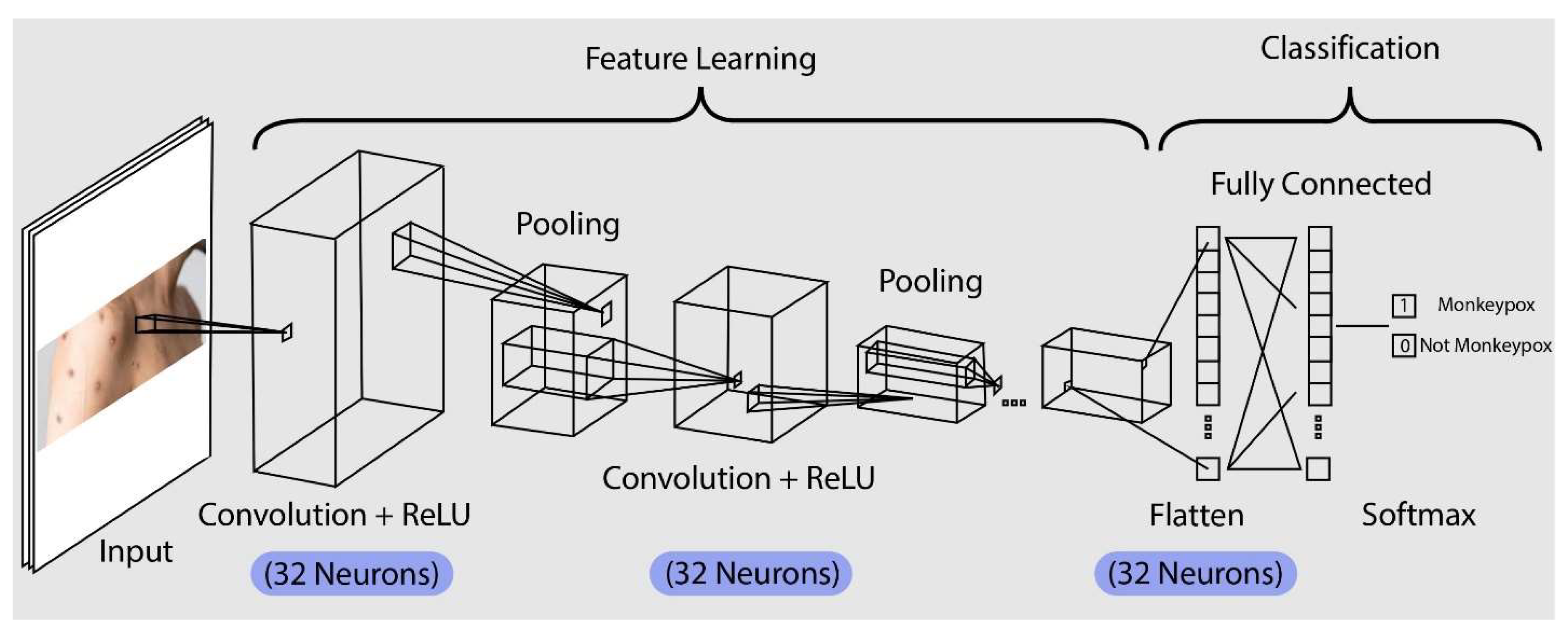

In this study, we created a CNN model for predicting Monkeypox cases. We evaluated the performance of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) model. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture that was designed to forecast instances of monkeypox based on lesion pictures is shown in the image. The model is divided into many phases, the first of which is the input layer, where skin lesion photos are analyzed. Using the ReLU activation function, a convolutional layer comprising 32 neurons is used in the first phase with 32 batch size. Important details from the picture, like edges and textures that could be signs of monkeypox, are extracted by this layer.

Figure 5.

The CNN system of our machine learning.

Figure 5.

The CNN system of our machine learning.

The model uses a pooling layer after the first convolution to lower the feature map's dimensionality. By retaining the most crucial traits and eliminating the less crucial ones, this pooling helps to lower computational complexity and the chance of overfitting. Subsequently, the model employs an additional convolutional layer, which has 32 neurons with ReLU activation, to enhance feature extraction and refinement. This allows for the capture of intricate patterns that differentiate monkeypox lesions from other skin disorders. The feature map is further reduced by an additional pooling layer, which makes sure that only the most important characteristics are kept. The model uses a pooling layer after the first convolution to lower the feature map's dimensionality. By retaining the most crucial traits and eliminating the less crucial ones, this pooling helps to lower computational complexity and the chance of overfitting. Subsequently, the model employs an additional convolutional layer, which has 32 neurons with ReLU activation, to enhance feature extraction and refinement. This allows for the capture of intricate patterns that differentiate monkeypox lesions from other skin disorders. The feature map is further reduced by an additional pooling layer, which makes sure that only the most important characteristics are kept. Following these layers, the model enters the flattening phase, which converts the pooled feature map into a vector with one dimension. A fully connected layer receives this flattened vector after which it analyses the learnt features to get ready for classification. A SoftMax output layer, which allocates a probability to each possible group based on whether it has monkeypox, is used to reach the final classification. Based on the visual information from lesion pictures, the model selects the category with the highest likelihood as its prediction, enabling an accurate and trustworthy diagnosis. After performing the model, metrics help us to understand how well the model is learning from the data.

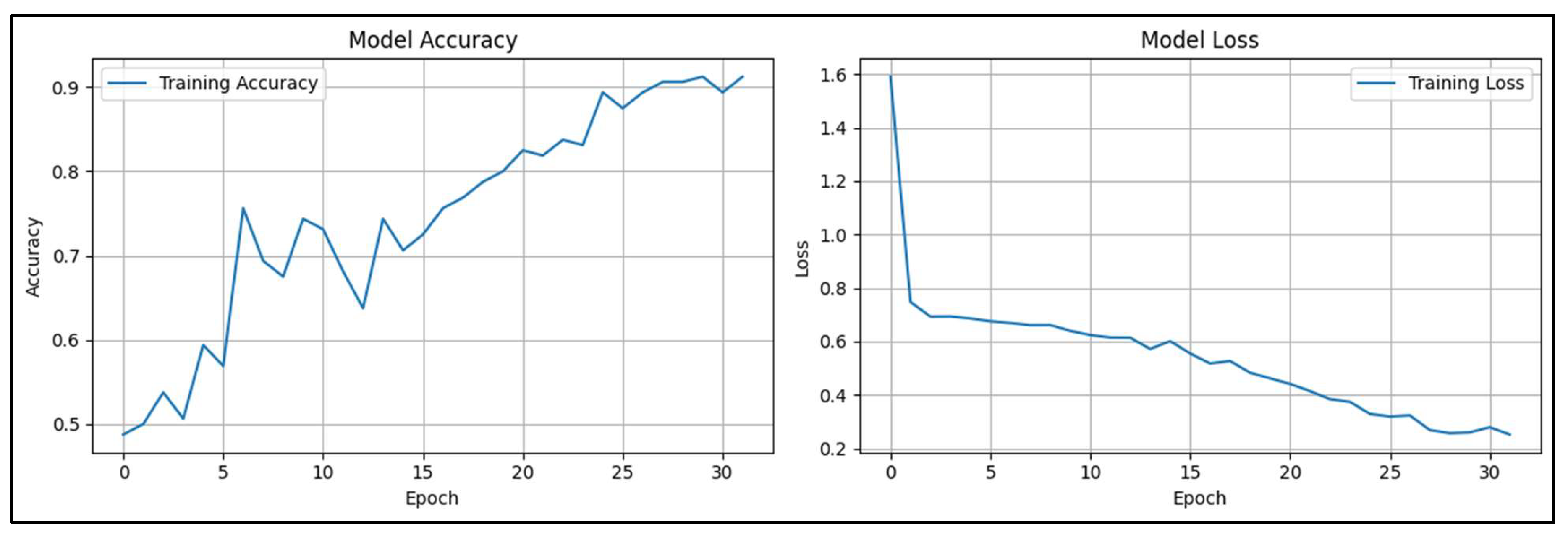

Figure 6.

The model accuracy and loss for CNN model.

Figure 6.

The model accuracy and loss for CNN model.

Figure 3 provides insights into the performance of the CNN model throughout the training process. The Model Accuracy graph, on the left, illustrates how the model's accuracy increases with more training. The model's initial accuracy of about 0.5 suggests that it is simply a guessing game. However, the accuracy improves gradually with occasional oscillations as the number of epochs rises. When the training procedure is complete, the model's accuracy approaches 0.9, meaning that most of the input data is being properly classified. The increasing trend indicates that the model is assiduously assimilating the data and can extrapolate the patterns it discerns to produce precise forecasts. The Model Loss graph shows the decrease in loss across the same number of epochs on the right. Lower values in the loss function indicate greater performance; it quantifies the discrepancy between the model's predictions and the actual labels. The loss is rather significant at initially, beginning at about 1.6, but it drops off fast in the first few epochs, indicating that the model picks up on error minimization quickly. The loss decreases with training, albeit more slowly at first, and finally settles at about 0.2. This decrease in loss shows that the model is steadily improving its forecasts and becoming more certain of its classifications.

Table 1.

The performance metrics of CNN mode.

Table 1.

The performance metrics of CNN mode.

| Significant Metrics |

|---|

| ROC AUC |

0.84 |

Specificity |

0.75 |

| Precision |

0.78 |

Log Loss |

0.67 |

| Recall |

0.90 |

Balanced Accuracy |

0.66 |

| F1-Score |

0.84 |

Mathews Correlation Coefficient |

0.82 |

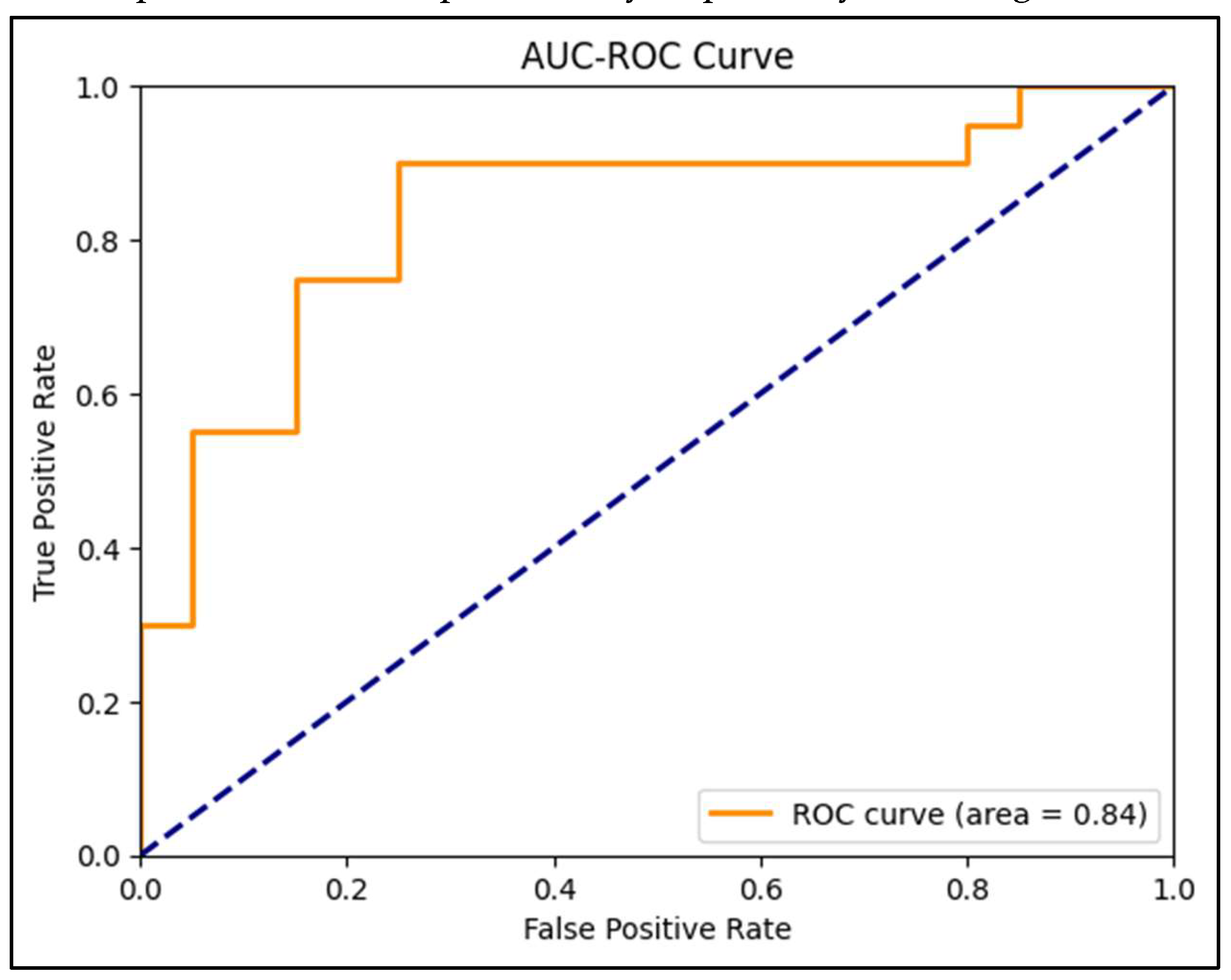

Table 1. demonstrates that metrics offer a thorough assessment of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model's capacity to forecast instances of monkeypox. With a ROC AUC value of 0.84, the model has a significant capacity to differentiate between instances of monkeypox and non-

pox cases, demonstrating its efficacy in classifying tasks over a range of threshold settings. Additional information is provided by the confusion matrix, which demonstrates that the model accurately detected 18 instances other than monkeypox and 15 cases of monkeypox. It did, however, make certain mistakes, misidentifying two real instances of monkeypox as false negatives and labelling five non-monkeypox cases as false positives. With a precision of 0.78, there is a 78% likelihood that the model will be right when it predicts a case of monkeypox. This is especially crucial to make sure the model doesn't incorrectly identify instances that aren't monkeypox as such too frequently. With a recall, or sensitivity, of 0.90, the model can identify 90% of real cases of monkeypox, demonstrating a high degree of detection accuracy when the illness is present. To provide a single measure that represents the model's overall performance in recognizing real positive instances and avoiding false positives, the F1-Score of 0.84 strikes a compromise between precision and recall. With a specificity of 0.75, the model accurately diagnoses 75% of non-monkeypox cases, which is critical for reducing the number of false positives. The log loss, which quantifies the degree of uncertainty in the model's forecasts, is 0.67. This comparatively low number suggests that the model's prediction accuracy is reasonable. The model's reliability is further demonstrated by the values of 0.82 for balanced accuracy and 0.66 for Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), which provides a more balanced measure that accounts for all four categories in the confusion matrix. MCC provides an average of sensitivity and specificity. The model's success in the precision-recall domain is highlighted by the PR AUC of 0.85, highlighting its robust prediction skills, particularly in precisely detecting instances of monkeypox.

Figure 7.

ROC curve of the CNN model.

Figure 7.

ROC curve of the CNN model.

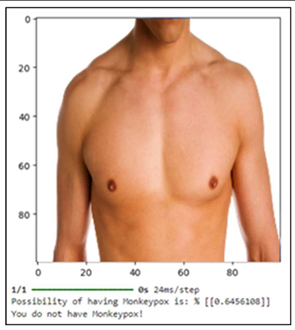

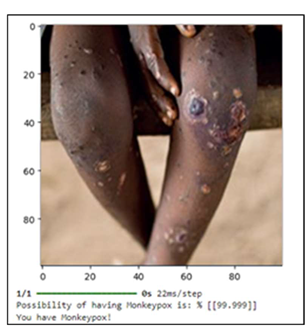

Tables show how different symptoms relate to the relevant estimates of a person's chance of contracting monkeypox. Every table depicts a distinct example, demonstrating differing degrees of symptoms and the model's estimation of risk. With simply a sore throat and no other notable symptoms, such as rectal discomfort, a single lesion, enlarged tonsils, or oral lesions, the person shown in

Table 1. is normally well. In response to this situation, the model says, "You do not have monkeypox," and it estimates that the likelihood of the patient having the illness is extremely low, at 0.64%. This example illustrates how a low-risk evaluation can be made when a mild or nonspecific symptom, such a sore throat, is not highly suggestive of monkeypox.

Table 2. shows an even more worrisome situation. The patient presents several symptoms, such as panile edema, oral lesions, enlarged tonsils, sore throat, rectal discomfort, and systemic sickness. The model offers a more cautious forecast since these symptoms are more closely linked to monkeypox. "You may have monkeypox," it says, estimating a 44.78% chance of contracting illness. This example shows how having several distinct symptoms increases the chance of a monkeypox diagnosis.

The person in

Table 4 has identical symptoms to those in

Table 3, but to a much greater extent. In this instance, the model asserts with confidence that "You have monkeypox," forecasting a 99.99% probability of success. In this instance, the model determines that the person nearly definitely has monkeypox based on the whole range of symptoms.

4. Discussion

Though to a far higher extent, the individual in

Table 4 exhibits the same symptoms as those in

Table 3. With a 99.99% chance of success, the model confidently declares, "You have monkeypox," in this case. Based on the complete range of symptoms, the model concludes that the patient in this case almost certainly has monkeypox. Furthermore, the loss graph demonstrates a notable decrease in the loss function, especially in the early training epochs, suggesting that the model picks up error minimization skills fast. The loss eventually stabilizes at about 0.2, which indicates that the model can continue to train and perform consistently. The confusion matrix offers further information on the model's advantages and disadvantages. Although a considerable proportion of cases, both monkeypox and non-pox, were correctly diagnosed by the model, it also included two erroneous negatives and five false positives. According to the model's accuracy of 0.78, recall of 0.90, and F1-Score of 0.84, it balances limiting false positives with accurately recognizing actual positive instances.

The model's ability to accurately identify instances that are not monkeypox is further supported by its specificity of 0.75. This is an important feature as it helps to minimize medical intervention and unwarranted worry. The model's balanced accuracy of 0.82 and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.66 offer a thorough assessment of the model's overall performance, considering all four categories in the confusion matrix. The log loss value of 0.67 of the models indicates a respectable level of certainty in its predictions. With a PR AUC of 0.85, the model demonstrates its resilience in precision-recall settings and its ability to produce reliable predictions, especially when the true positive rate is crucial. The model can modify its risk projections according to the intensity and mix of symptoms displayed, as shown by the examination of specific examples in the tables. For instance, the model predicts a low risk of monkeypox in instances with moderate or vague symptoms, but a higher incidence of the illness in cases with more severe and complex symptoms. This flexibility is essential in real-world situations where individuals' symptom presentations might differ greatly from one another.

All things considered, the CNN model has a great deal of potential as a monkeypox diagnostic tool, providing a high degree of accuracy, particularly in identifying genuine cases while keeping a respectable rate of specificity. Nonetheless, the existence of some misclassifications suggests that more improvement might be made, either by adding more data, utilizing more intricate architectures, or utilizing better pre-processing methods. These enhancements may contribute to a decrease in false positives and false negatives, which would ultimately result in a diagnostic tool that is more dependable and broadly useful.

Data was gathered for the study by using web scraping techniques on the websites of health and public news organizations. The same techniques and sources were used to collect picture data for recent research. A significant amount of picture samples was gathered for deep learning with the use of data replication techniques. This is because high-resolution skin lesion photographs of individuals with monkeypox have not yet been released and it is thought that they will not be available anytime soon. Thus, to facilitate future research, it is critical that global health organizations generate and disseminate monkeypox imaging collections. It will be particularly helpful for testing and contrasting more accurate and reliable models. In our study, the highest accuracy rate with an F1-score of 82% was achieved. Ahsan et al. [

23] obtained an F1-score value of 83% on the test data with the VGG16 model. Our appreciation for CNN structures grows despite the low-quality dataset, given that we attain high accuracy classification results.

Unlike other studies that just used pictures of monkeypox lesions to support CNN-based categorization [

20], ours adopted a more thorough strategy by combining a dataset that contains extensive symptom information in addition to the lesion photos. The incorporation of symptomatic data into our CNN model improved the algorithm's capacity to correctly detect instances of monkeypox. The model successfully captured the intricacy of monkeypox presentation by making better educated predictions by utilizing both visual and clinical cues. This dual-input strategy not only increased the model's overall accuracy but also decreased the possibility of misclassification, providing a more reliable diagnostic tool that can more accurately differentiate monkeypox from other illnesses with comparable visual features. By adding symptom data, CNNs have made significant progress in their capacity to identify diseases. This shows how valuable multimodal inputs are in enhancing the accuracy and dependability of machine learning models used in medical diagnostics. Our study showed that our CNN model greatly improved the accuracy and reliability of monkeypox classification by using both symptom data and lesion pictures, outperforming earlier models that just used visual data. By using a complete approach, our model was able to accurately represent the subtle presentation of monkeypox, lowering the possibility of misdiagnosis and resulting in a more reliable and powerful diagnostic tool.

4.1 Advantages of Method for Diagnosing

CNNs excel in automatically learning and extracting relevant features from images without the need for manual feature engineering. This is particularly advantageous when analyzing complex medical images, such as those of monkeypox lesions, as the model can identify subtle patterns that may be difficult for human experts to detect. The combination of CNNs with clinical data (symptoms) allows for a hybrid approach, improving diagnostic accuracy. This dual-input model leverages both visual and clinical information, outperforming models that rely solely on one type of data, making the model more robust in cases where image quality or data availability may be limited. CNNs tend to outperform traditional machine learning models, such as decision trees or support vector machines (SVM), in tasks that involve image data. In your monkeypox model, the achieved metrics—balanced accuracy of 82%, F1-Score of 84%, and high sensitivity (80%) and specificity (85%)—demonstrate its capability to differentiate between monkeypox and other conditions effectively. Such performance is often superior to non-deep learning models, which require feature selection and extensive preprocessing. Once trained, CNN models can be scaled and applied to large datasets and real-time diagnosis in clinical settings. This makes CNNs ideal for epidemic surveillance and large-scale screening during outbreaks of diseases like monkeypox, providing rapid and reliable results. CNNs are highly transferable. The same model architecture could potentially be fine-tuned to diagnose other dermatological conditions with similar image-based symptoms, such as chickenpox or smallpox. This adaptability is an asset in cases where multiple diseases need to be distinguished based on skin lesion characteristics.

4.2 Disadvantages of Method for Diagnosing

CNNs typically require large amounts of labeled data for training to achieve optimal performance. In the case of monkeypox, where data might be scarce or unbalanced (due to fewer high-resolution images or limited case numbers), this could lead to overfitting or decreased accuracy. Traditional machine learning models, such as logistic regression or SVM, may perform better with smaller datasets. CNNs are resource-intensive during both training and inference, requiring significant computational power and memory, particularly for processing high-resolution medical images. CNNs are highly sensitive to the quality of the input images. Variations in lighting, resolution, or image artifacts could affect model performance. While symptom-based hybridization helps to mitigate this issue, reliance on visual data still introduces challenges in settings where high-quality imaging equipment is unavailable. Other machine learning models that depend more on structured data might be less affected by image variability. Since the genetic subtype of the virus and the progression of rashes can cause substantial diagnostic challenges, model’s ability to analyze visual data from rashes significantly reduces reliance on subjective clinical observation, which can lead to errors [

24]. However, continuous retraining with new data on emerging strains and improving cross-validation with clinical symptoms would further enhance its accuracy in preventing misdiagnoses.

5. Conclusion

This work successfully created a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model that combined a comprehensive dataset of patient symptoms with high-definition skin lesion photos for the diagnosis of monkeypox. With a balanced accuracy of 82%, an F1-Score of 84%, and a sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 85%, respectively, the CNN model showed strong prediction ability. These metrics demonstrate the model's good ability to minimize false positives in a clinical scenario by detecting actual positive instances while keeping a decent degree of specificity. The diagnosis accuracy of the model was much improved by the addition of clinical data, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and the development of skin lesions, in addition to visual information. Because monkeypox frequently presents with a wide variety of symptoms and skin appearances that can easily be mistaken with other illnesses like chickenpox, smallpox, or other viral exanthems, this hybrid approach allowed the model to better depict the varied character of the disease. The combination of clinical and visual data allowed the model to distinguish monkeypox from various illnesses that resembled it with greater accuracy. The model performed well despite the difficulties caused by the scarcity and unpredictability of high-resolution pictures, proving the usefulness of CNNs in medical diagnosis. To improve the model's capacity to generalize from the existing data, preprocessing techniques like picture normalization and augmentation were essential. The model's resilience to these difficulties and its high accuracy highlights the promise of CNN-based diagnostic tools in resource-constrained environments where access to a variety of training data may be limited. Nonetheless, there is potential for improvement as evidenced by the existence of certain misclassifications, especially in situations when the skin lesions were at an early or unusual stage. These mistakes imply that greater model improvement might be beneficial, maybe by adding other data sources (e.g., medical history or epidemiological data) and employing more sophisticated architecture or ensemble techniques. The widespread use of CNN models for monkeypox detection faces several limitations. The model's dependency on high-quality, labeled images restricts its applicability in regions where healthcare infrastructure is lacking, particularly in rural or low-resource areas. Additionally, CNNs require considerable computational power, which limits their use in underfunded settings. Another limitation is the "black box" nature of CNNs, meaning they offer limited interpretability for clinicians, which could hinder trust in automated decisions. CNNs may struggle with generalizing new strains of the virus without adequate retraining using updated datasets. The "Ib sub-branch" refers to a specific lineage of the monkeypox virus that was identified in the 2024 outbreak, primarily affecting women and children, as reported by WHO. The flexibility of the CNN model in detecting monkeypox is rooted in its ability to adapt to new clinical data and epidemiological shifts. Given WHO's recent findings regarding the Ib sub-branch primarily affecting women and children, which has resulted in some discrepancies in clinical manifestations, the model can be retrained using updated datasets. This adaptability allows it to recognize evolving symptom profiles and subtle variations in skin lesions across different strains. Continuous model refinement ensures its relevance and accuracy, particularly as new outbreaks and viral mutations emerge.

In summary, the CNN model created in this work has significant potential as a highly accurate and dependable monkeypox diagnostic tool. It is an effective tool for physicians since it may combine clinical and visual data, especially when separating monkeypox from other illnesses that are similar. This model has the potential to enhance early identification and response efforts in future outbreaks and marks a major advancement in the application of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of emerging infectious illnesses.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Emir Öncü developed the AI models used in tissue formation, wrote all the sections related to AI model development, monkeypox determination and drew the figures.

Conflicts of competing interests

In this article, the authors state that they have no competing financial interests or personal affiliations.

Declaration of generative AI and AI assisted technologies in the writing process

The writers utilized Grammarly, Quillbot, and ChatGPT to improve readability and check grammar while preparing this work. After utilizing this tool/service, the writers assumed complete accountability for the publication's content, scrutinizing and revising it as needed.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study, *Monkeypox Skin Images Dataset (MSID)*, is publicly available and can be accessed at Mendeley Data. The dataset was provided by Bala and Hossain (2023) and includes images necessary for monkeypox detection. For further details on the dataset, please refer to: Bala, Diponkor; Hossain, Md Shamim (2023), “Monkeypox Skin Images Dataset (MSID)”, Mendeley Data, V6, doi: [10.17632/r9bfpnvyxr.6](

https://doi.org/10.17632/r9bfpnvyxr.6).

Acknowledgements

The endeavor was exclusively carried out using the organization's current staff and infrastructure, and all resources and assistance came from inside sources. Ethical approval is not applicable. The data supporting the study's conclusions are accessible inside the journal, according to the author. Upon a reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide the raw data supporting the study's findings.

References

- J. G. Rizk, G. J. G. Rizk, G. Lippi, B. M. Henry, D. N. Forthal, and Y. Rizk, “Prevention and Treatment of Monkeypox,” Drugs, vol. 82, no. 9, pp. 957–963, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaler, A. J. Kaler, A. Hussain, G. Flores, S. Kheiri, and D. Desrosiers, “Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathogenesis, and Manifestation,” Cureus, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. K. Borkar, S. G. Choudhari, H. G. Mendhe, and N. J. Bankar, “Recent Outbreak of Monkeypox: Implications for Public Health Recommendations and Crisis Management in India,” Cureus, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, L. Y. Huang, L. Mu, and W. Wang, “Monkeypox: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment and prevention,” Dec. 01, 2022, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Hakim and S. A. Widyaningsih, “The recent re-emergence of human monkeypox: Would it become endemic beyond Africa?,” Mar. 01, 2023, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Farahat et al., “Human monkeypox disease (MPX),” 2022, EDIMES Edizioni Medico Scientifiche. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, L. Y. Huang, L. Mu, and W. Wang, “Monkeypox: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment and prevention,” Dec. 01, 2022, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- C. Lai, C. K. C. Lai, C. K. Hsu, M. Y. Yen, P. I. Lee, W. C. Ko, and P. R. Hsueh, “Monkeypox: An emerging global threat during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Oct. 01, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. Altun, H. M. Altun, H. Gürüler, O. Özkaraca, F. Khan, J. Khan, and Y. Lee, “Monkeypox Detection Using CNN with Transfer Learning,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 4, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks,” Nature, vol. 542, no. 7639, pp. 115–118, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Litjens et al., “A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis,” Dec. 01, 2017, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hannun et al., “Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network,” Nat Med, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 65–69, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarraf and G. Tofighi, “Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease using fMRI Data and Deep Learning Convolutional Neural Networks,” Mar. 2016, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.08631.

- U. R. Acharya, S. L. U. R. Acharya, S. L. Oh, Y. Hagiwara, J. H. Tan, and H. Adeli, “Deep convolutional neural network for the automated detection and diagnosis of seizure using EEG signals,” Comput Biol Med, vol. 100, pp. 270–278, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Gulshan et al., “Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs,” JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 316, no. 22, pp. 2402–2410, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Ozturk, M. T. Ozturk, M. Talo, E. A. Yildirim, U. B. Baloglu, O. Yildirim, and U. Rajendra Acharya, “Automated detection of COVID-19 cases using deep neural networks with X-ray images,” Comput Biol Med, vol. 121, p. 103792, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Pramanik, S. R. Pramanik, S. Sarkar, and R. Sarkar, “An adaptive and altruistic PSO-based deep feature selection method for Pneumonia detection from Chest X-rays,” Appl Soft Comput, vol. 128, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lecun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” May 27, 2015, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Eid et al., “Meta-Heuristic Optimization of LSTM-Based Deep Network for Boosting the Prediction of Monkeypox Cases,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Pramanik, B. R. Pramanik, B. Banerjee, G. Efimenko, D. Kaplun, and R. Sarkar, “Monkeypox detection from skin lesion images using an amalgamation of CNN models aided with Beta function-based normalization scheme,” PLoS One, vol. 18, no. 4 April, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Pramanik, S. R. Pramanik, S. Sarkar, and R. Sarkar, “An adaptive and altruistic PSO-based deep feature selection method for Pneumonia detection from Chest X-rays,” Appl Soft Comput, vol. 128, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Surveillance, case investigation and contact tracing for mpox (monkeypox) Interim guidance Changes from earlier version,” 2024.

- M. M. Ahsan et al., “Deep transfer learning approaches for Monkeypox disease diagnosis,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 216, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gessain, E. Nakoune, and Y. Yazdanpanah, “Monkeypox,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 387, no. 19, pp. 1783–1793, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).