1. Introduction

In recent years, the power system has been evolving towards a new system primarily based on wind and solar energy under the overarching goal of carbon neutrality in China. This shift has led to the gradual development of power transmission equipment towards a high proportion of power electronics. Consequently, core electrical equipment in power transmission equipment, such as high-frequency transformers, are now facing challenges related to high-frequency operation. These transformers, which are connected to power electronic converters, are subjected to repetitive square wave pulse voltages characterized by short rise times, high amplitudes, and high frequencies. Additionally, high-frequency transformers are also challenged by high power density and compact, lightweight designs, resulting in reduced volume and weight compared to their counterparts with similar capacities. These compact structures make heat dissipation more difficult in transformers. Notably, power converters connected to high-frequency transformers will break through technological bottlenecks in the future, achieving frequencies up to 100 kHz or even higher [1-2]. In addition, given their excellent cooling and insulating properties, oil-immersed transformers enable the development of high-frequency transformers towards high power, high voltage, and large capacity. Aramid paper, used as the primary inter-turn insulation material in oil-immersed high-frequency transformers, is prone to partial discharge and local overheating, which are principal causes of premature failure of inter-turn insulation [3-5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop composite aramid paper with excellent resistance to high-frequency partial discharge and high temperatures.

Currently, the methods for enhancing the performance of insulating materials primarily include the preparation of intrinsic materials and filled composite materials. In the field of intrinsic insulating materials, Huang et al [

6] proposed that incorporating phenyl sulphide groups into polyimide molecular chains can effectively reduce the high-frequency dielectric loss of the modified polyimide films. Wang [

7] et al investigated the effects of vapour phase fluorination on the surface charge and space charge characteristics of oil-immersed Nomex paper. They found that vapour phase fluorination accelerates the decay rates of both positive and negative charges, and reduce the energy and density of hole and electron traps in the fluorinated samples. However, the preparation of intrinsic materials is costly and challenging to industrialize.

In the realm of filled composite materials, the primary approach involves adding high thermal conductivity and high insulation fillers to the insulating material matrix to enhance the material's overall performance, including discharge resistance, high-temperature resistance, and corona resistance. Common fillers used include one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional fillers. Duan [

8] et al utilized reduced graphene oxide (frGO) and one-dimensional multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) as mixed thermal conductive particles to increase the density of thermal conductive network within the aramid insulation paper matrix. The thermal conductivity of the aramid paper (PMIA) is effectively improved and the insulation properties of the composite insulating materials are declined due to the high conductivity of carbon materials. Liu [

9] et al incorporated functionalized two-dimensional boron nitride nanosheets (BNNS) into the polyetherimide (PEI) matrix. They found that adding an appropriate amount of BNNS enhances the breakdown strength of the matrix due to the formation of dispersed deep traps within the material. Qin [

10] et al prepared BN fiber-graphene microplatelets using the melt blending method. They found that the thermal conductivity is 4.2 times higher than that of polypropylene (PP) and electrical insulation properties is slightly improved, attributed to the unique "dual network" structure formed by GNP and BN fibres. Liu [

11] et al added two-dimensional BN to silicone rubber, achieving a 30% increase in thermal conductivity as well as improvements in electrical breakdown strength and hydrophobicity, though the mechanical performance deteriorated. Huang [

12] et al prepared three-dimensional boron nitride nanosheet/epoxy composites via radial freeze casting, resulting in composite materials with through-plane thermal conductivity of 4.02 W/(m·K) and in-plane thermal conductivity of 3.87 W/(m·K). Chen [

13] employed electrospinning to fabricate three-dimensional thermal conductive networks within polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) polymer nanocomposite films by filling them with BNNS, achieving ultra-high in-plane thermal conductivity and excellent electrical insulation properties. However, the production costs of three-dimensional fillers are high, and the preparation process is complex [

14]. Additionally, it is crucial to note that agglomeration is occurred when the nano-filler content is high or the compatibility between the filler and the matrix is poor, adversely affecting the various properties of the insulating materials [

15].

Existing research shows that the addition of coupling agents can effectively improve the compatibility between nano-fillers and the matrix. Zha [

16] et al used KH-550 silane coupling agent to modify and prepare PI/TiO

2 nanocomposite films. The coupling agent was found to effectively improve the compatibility between the nano-filler and the matrix, resulting in a more uniform dispersion in the matrix. Lv [

17] et al studied the effect of different types of silane coupling agents on the electrical properties of meta-aramid composite insulating paper with nano-TiO

2. It can be found that suitable types of silane coupling agents can effectively improve the dispersion of nano-fillers in the matrix, increasing the breakdown voltage and volume resistivity of the composite insulating paper. Additionally, these agents enhance the temperature resistance and mechanical strength of aramid fibers.

The aforementioned studies primarily focus on the thermal conductivity of modified insulating materials. However, some researchers have also investigated the changes in the high-frequency discharge resistance of modified composite insulating materials. For example, Li [

18] et al found that adding dopamine-grafted nano boron nitride to epoxy resin can effectively improve the charge dissipation rate and flashover voltage of epoxy resin composite material under high-frequency conditions. Zhao [

19] et al weakened the electron trap capture effect under high-frequency conditions by pre-impregnating GHG paper, effectively reducing the flashover voltage. Li [

20] et al studied the high-frequency partial discharge characteristics at different aging stages of epoxy resin. It can be found that the amount and number of discharges generally increase as the probability of effective initial electron generation on the surface of insulation defects changes, and the phase range of partial discharge extends towards both ends. Currently, research on the performance of composite insulating materials under high-frequency conditions is limited and requires further exploration. In view of the above results, it is found that there is still a lack of comprehensive studies on the partial discharge resistance and high-temperature characteristics of composite insulating papers under high-frequency conditions. Therefore, heat treatment and ultrasonic exfoliation methods are combined to exfoliate boron nitride nanosheets (BNNSs). BNNSs is modified by Silane coupling agent KH-550 to prepare composite aramid paper with superior comprehensive performance.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Preparation of High-Performance Composite Aramid Paper

2.1.1. Main Materials

The materials used in this study are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Preparation Process of Composite Aramid Paper

2.2.1. Preparation Process of Boron Nitride Nanosheets (BNNSs)

600 mg of h-BN (hexagonal boron nitride) is added to a round-bottom flask containing 100 ml of double-distilled water. The mixture is sonicated for 2 hours and then allowed to precipitate for 1 hour. After complete precipitation of h-BN, the h-BN was separated. The h-BN is then heat-treated at 400°C for 2 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the sample is dispersed in water for 2 hours and then allowed to precipitate for 12 hours. The upper clear liquid precipitated was BNNSs [

21]. The upper clear liquid is filtered using a polytetrafluoroethylene membrane (pore size 0.1 μm). The remaining product filtered is dried in a vacuum oven at 90°C for 20 hours, obtaining BNNSs.

- 2.

Preparation of BNNSs-OH

The BNNSs is heated to 1000°C and maintained for 1 hour. After cooling, the material is washed with hot water and dried, obtaining hydroxylated boron nitride nanosheets (BNNSs-OH) [

22].

2.2.2. Preparation Process of Composite Filler KH-550@BNNSs Particles

A 4% mass fraction of KH-550 is prepared, with the solvent being a mixture of deionized water and anhydrous ethanol in a 9/1 ratio. The mixture is reacted at 80°C for 30 minutes. Then, 200ml of a 2% BNNSs-OH solution is added. The mixed solution is magnetically stirred at 80°C for 5 hours and is washed multiple times with deionized water and anhydrous ethanol, and filtered to remove unreacted silane coupling agents. Finally, it is baked in a vacuum at 90°C for 10 hours, obtaining KH-550 modified BNNSs, denoted as K-BNNSs.

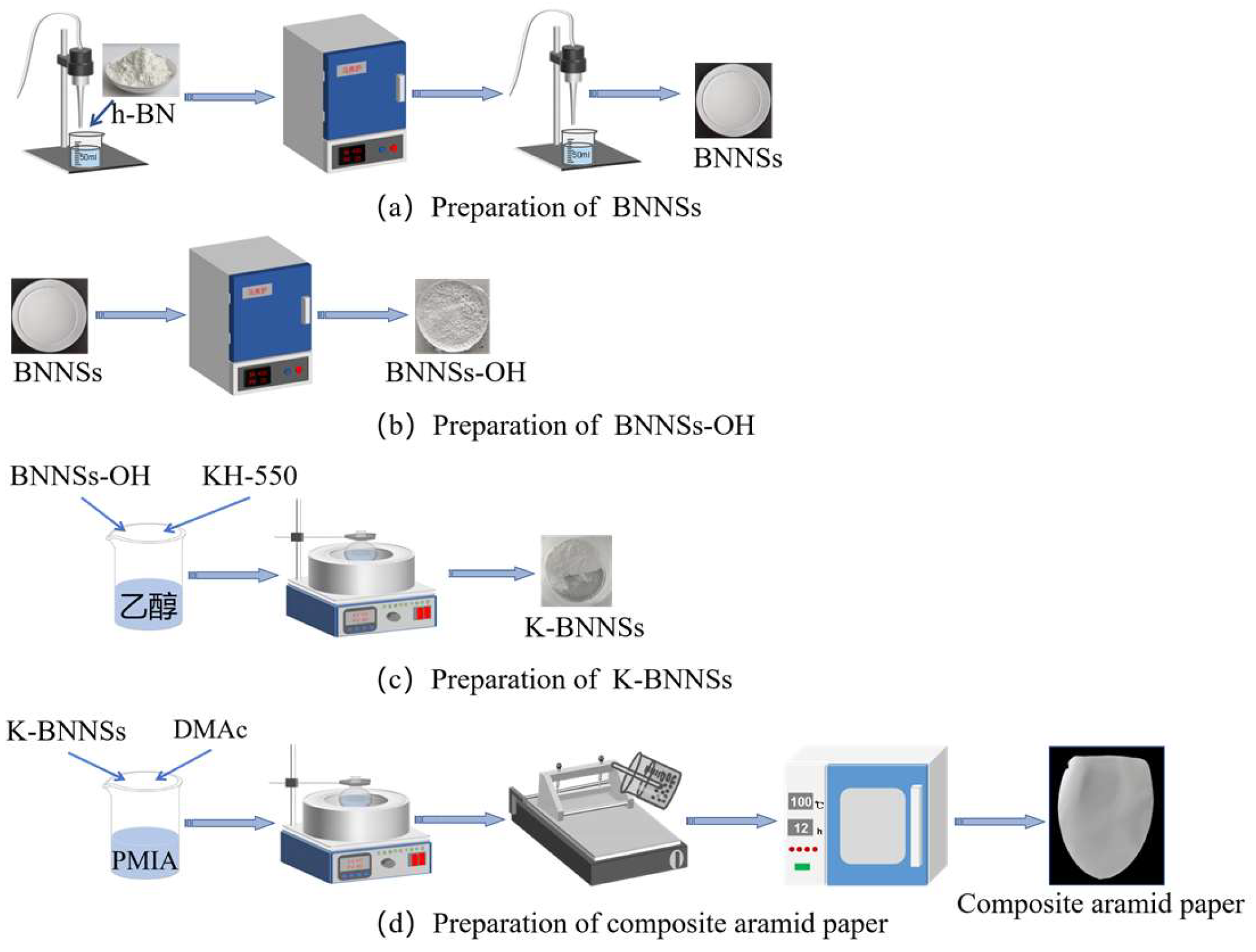

2.2.3. Preparation Process of Composite Aramid Paper

The PMIA slurry was diluted to a 12% solid content (using DMAc as the solvent). KH-550@BNNSs are dispersed in DMAc and added to the PMIA slurry. The mixture is stirred at 50°C for 6 hours and then degassed under vacuum for 1.5 hours. The KH-550@BNNSs/PMIA wet film is prepared using a coating machine. The wet film is first placed in an oven at 100°C for 16 hours, then transferred to a vacuum oven at 80°C and dried for 16 hours to completely remove the DMAc solvent. Composite aramid papers with particle contents of 0%, 5%, 8%, 10% and 13% are denoted as F-0, F-5, F-8, F-10 and F-13, respectively. The preparation process is shown in

Figure 1. Different performance tests are conducted on the composite aramid paper samples, with each test repeated five times.

3. Performance Characterization of Composite Aramid Paper

3.1. Performance Characterization of Composite Particles

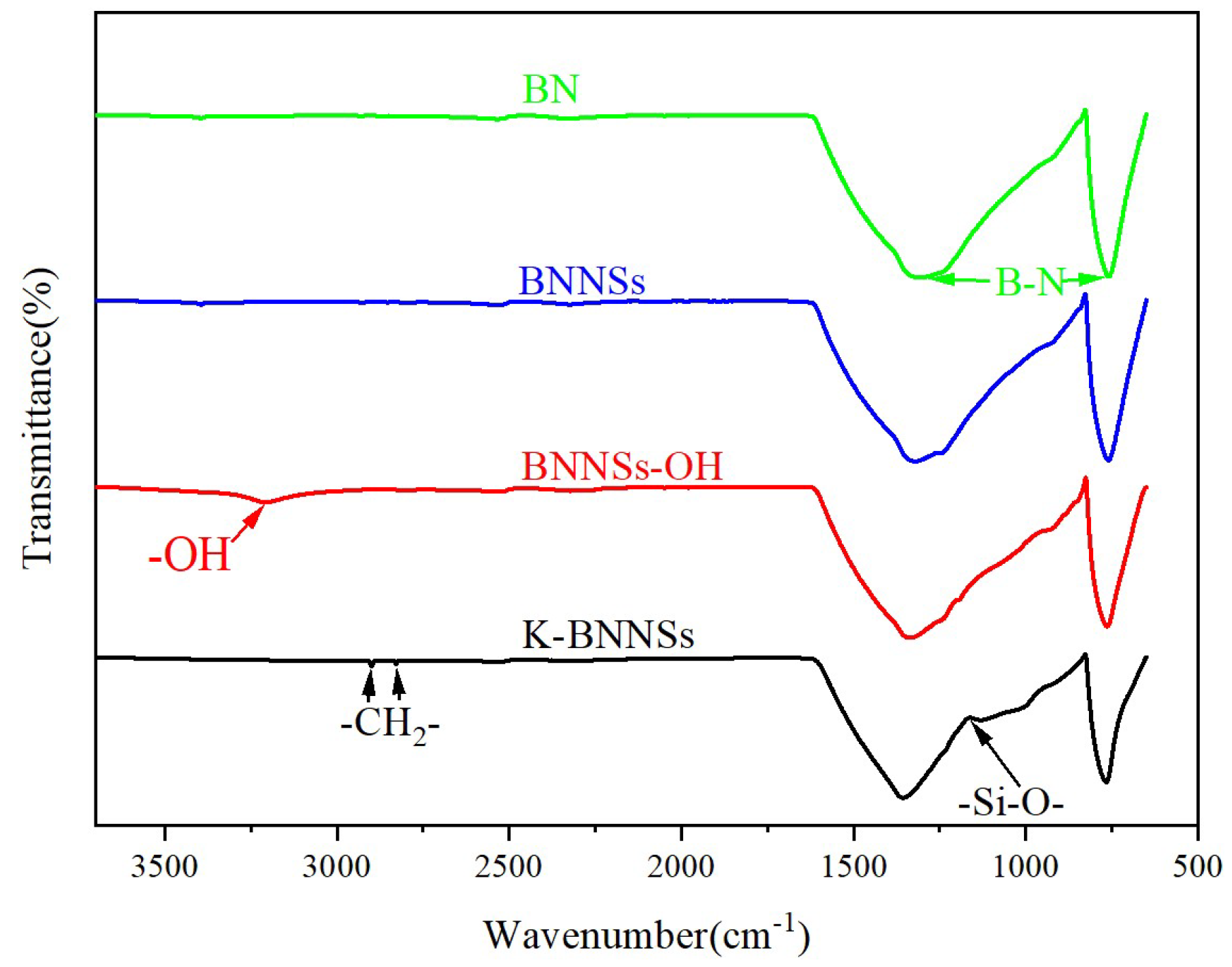

3.1.1. FTIR Analysis

FTIR is used for the chemical structure analysis of the particles. The results are shown in

Figure 2. It can be observed that the characteristic absorption peaks of B-N bonds are appeared in all four types of particles. For BNNSs-OH particles, a distinct hydroxyl (-OH) absorption peak is observed at 3208.95 cm

-1. This indicates that hydroxyl groups are successfully grafted onto the surface of BNNSs after high-temperature treatment.

In the K-BNNSs particles, the hydroxyl characteristic absorption peak is completely disappeared due to the reaction between KH-550 and the hydroxyl groups in BNNSs-OH particles. In addition, new characteristic absorption peaks of methylene (-CH2-) is appeared at 2830.38 cm-1 and 2900.58 cm-1, and a characteristic absorption peak of Si-O bonds is observed at 1131.77 cm-1. These findings confirm that the silane coupling agent KH-550 undergo coupling reactions with BNNSs-OH, successfully grafting silane onto the surface of BNNSs-OH.

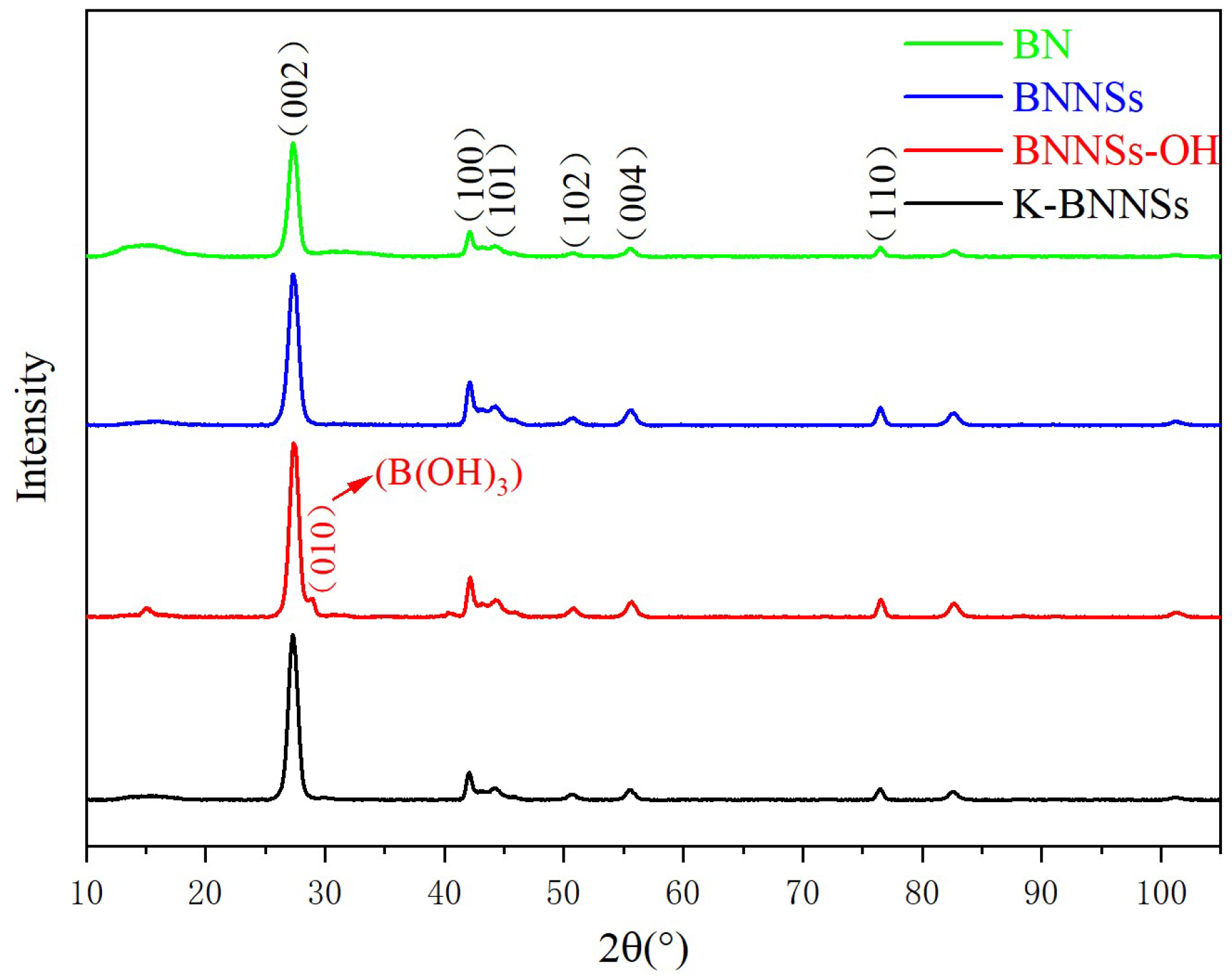

3.1.2. XRD Analysis

The crystal structures of BN, BNNSs, BNNSs-OH, and K-BNNSs are analysed by XRD. The results are shown in

Figure 3.

As seen from the figure, the XRD patterns of the four types of particles are generally similar. The characteristic peaks of BN crystals at 26.749°, 41.583°, 43.692°, 50.077°, 54.935°, and 76.082° correspond to the diffraction peaks of the (002), (100), (101), (102), (004), and (110) crystal planes, respectively. The characteristic peak intensity of BNNSs obtained by heat treatment combined with ultrasonic exfoliation, is higher than that of BN, indicating that this exfoliation method produces well-developed BNNSs crystals.

Additionally, the XRD pattern of BNNSs-OH shows a diffraction peak of B(OH)3 at the (010) crystal plane at 28.94°, suggesting successful grafting of hydroxyl groups onto the surface of BNNSs after high-temperature treatment. This finding is consistent with the FTIR analysis results.

3.1.3. TEM Analysis

TEM is used to analyse BN and BNNSs particles. The results are shown in

Figure 4. It can be seen that for BN particles, multiple layers are clearly stacked due to intermolecular forces. For BNNSs, the multilayer structure disappears as a result of heat treatment and ultrasonic exfoliation, making BNNSs appear semi-transparent. Additionally, the size of BNNSs ranging from 100 nm to 50 nm is slightly smaller compared to BN and the large-sized plate-like structures disappears. Some small nano-sheets might originate from defects in the precursor BN or be inherited from small BN fragments.

Figure 4(c) and 4(d) show that the lattice spacing of the (004) crystal plane in BN crystals is 1.63 nm, while the lattice spacing of the (110) crystal plane in BNNSs crystals is 1.27 nm. Comparing these measurements with the standard BN PDF card reveals a slight increase in lattice spacing after exfoliation. Comparing the electron diffraction patterns in the top left corners of

Figure 4(c) and 4(d), it can be concluded that exfoliation causes minor structural changes. The electron diffraction pattern in

Figure 4(c) clearly shows a six-fold symmetric structure, while the pattern in

Figure 4(d) only shows a symmetric arrangement due to layer overlap.

3.2. Performance Characterization of Composite Aramid Paper

3.2.1. SEM and EDS Analysis

Based on section 1, a cold-field emission scanning electron microscope is used to analyse composite aramid paper with different contents of highly insulating and thermally conductive particles: 0%, 10%, and 10% without KH-550 modification. The surface and cross-sectional microstructure characteristics are obtained and shown in

Figure 5.

From the figure, it is evident that the surface of F-0 is smooth, with small agglomerated protrusions on the cross-section. The surface of F-10 becomes rough, and the cross-section shows interlaced dendritic and layered structures. This indicates that the addition of K-BNNSs improves the agglomeration phenomenon during the coating and forming process of aramid pulp, leading to an interlaced, complex dendritic and layered structure. These structure make the internal matrix of aramid paper more uniform and the connections between particles tighter, facilitating the formation of a thermal conductive network within the composite aramid paper, hence increasing thermal transfer efficiency.

To demonstrate the effect of KH-550 on improving the compatibility of modified particles with the aramid paper matrix, the aramid paper with 10% unmodified particle content is observed as shown in

Figure 5(e) and 5(f). It is evident that this sample not only has voids on the surface but also shows a few voids at the interface. Additionally, severe surface agglomeration is observed and a clumped morphology is displayed in the cross-section, which may be less effective in establishing a thermal conductive network compared to the dendritic structure of F-10.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the addition of K-BNNSs particles significantly improves the microstructure of aramid paper. Not only does it result in a more uniform organization, but the interlaced dendritic and layered microstructure is also highly beneficial for establishing a thermal conductive network within the aramid paper. Moreover, the KH-550 modified BNNSs-OH greatly improves the compatibility between the thermally conductive particles and the matrix, significantly reducing agglomeration within the material and resulting in a denser and more uniform structure, leading to effective modification.

To further confirm the incorporation of K-BNNSs particles into the composite aramid paper, selected area EDS analysis is performed on the cross-section of F-10 and the results obtained are shown in

Figure 6. It can be observed that the elements of B, N, Si, and O are uniformly distributed across the cross-section. This proves that the composite aramid paper contains not only boron nitride nano-sheets but also KH-550. Thus, the successful addition of K-BNNSs particles is demonstrated.

3.2.2. Thermogravimetric and Thermal Conductivity Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is performed on composite aramid paper with different K-BNNSs contents and the results obtained are shown in

Figure 7. The TGA curves indicate that the composite aramid papers containing modified particles exhibit similar trends and better thermal stability compared to pure meta-aramid paper. Within the range of 380–430℃, small molecules within the composite aramid paper decompose. Between 430–540℃, a significant mass loss occurs in meta-aramid paper, likely due to increased molecular thermal motion as temperature rises, where impurity molecules in the air penetrate the aramid paper and react. The reaction causes cleavage of C-N and C-O bonds, and subsequent gradual thermal degradation of unstable macromolecular chains.

As the temperature further increases, molecular motion within the aramid paper becomes more pronounced, and the previously undecomposed macromolecular chains gradually degrade into small molecular chains. By 800℃, the residual rates of F-0, F-5, F-8, F-10, and F-13 are 35.57%, 43.07%, 46.56%, 48.86%, and 46.53%, respectively, with F-10 achieving the highest residual rate. This indicates that the addition of the highly thermally conductive and insulating K-BNNSs reduces the degradation rate of aramid paper throughout the thermal decomposition process, particularly mitigating fiber decomposition significantly in the range of 400–800℃. The enhanced thermal stability is primarily attributed to the exceptional thermal stability of the added composite particles, making the material less prone to decomposition at high temperatures.

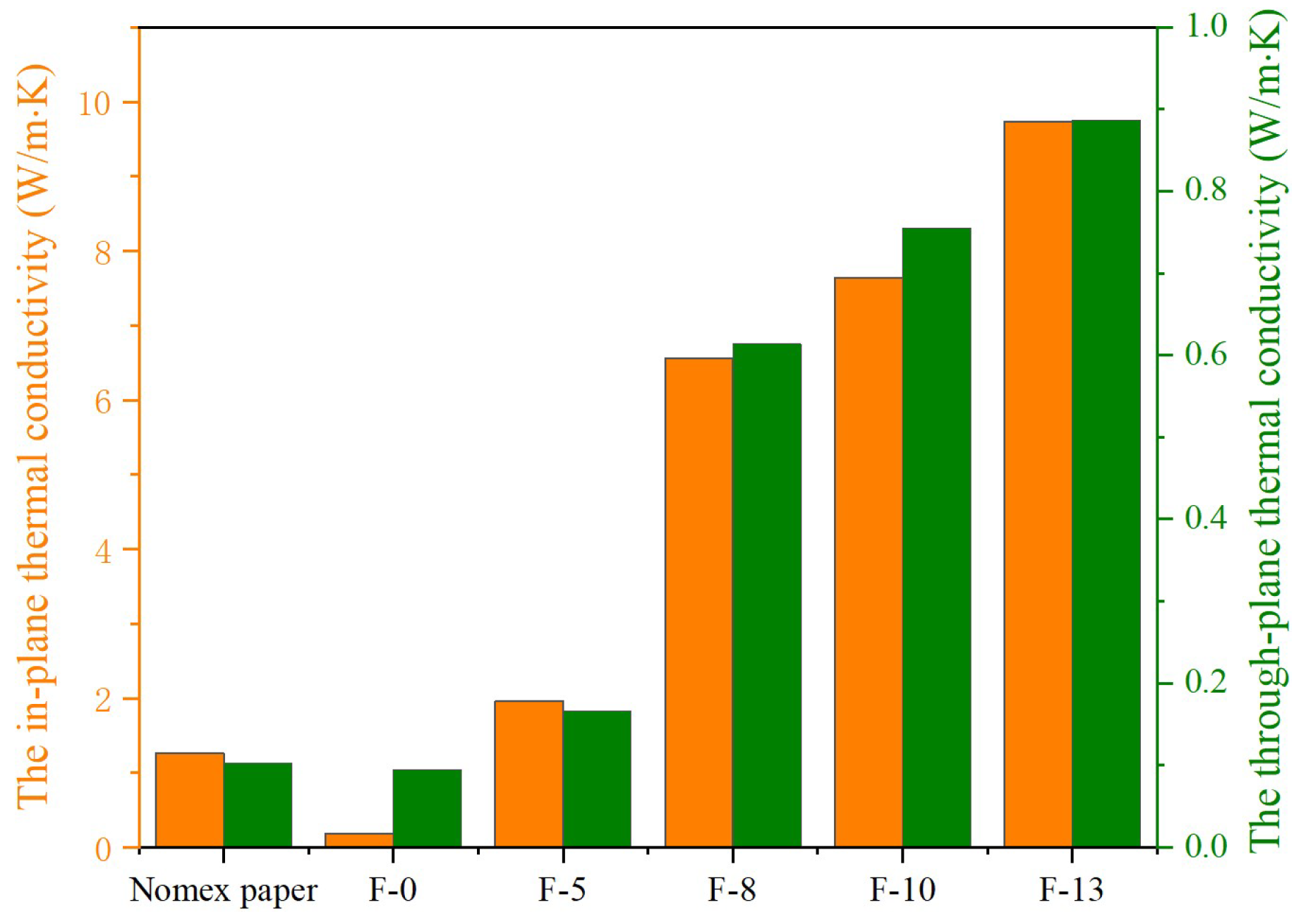

Thermal conductivity measurements are performed on composite aramid papers with varying K-BNNSs contents and Nomex paper, analyzing both in-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity. The results are shown in

Figure 8.

It can be observed that both the in-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity of the composite aramid papers containing K-BNNSs particles are superior to that of pure meta-aramid paper. Additionally, the thermal conductivity increases with the addition of nano-fillers. When the nano-filler content reaches 13%, the composite aramid paper exhibits the highest in-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity values, which are 9.73 W/(m·K) and 0.89 W/(m·K), respectively. Compared to Nomex paper, the in-plane thermal conductivity improves by 668.33%, and the through-plane thermal conductivity improves by 760.66%. Compared to other composite insulating papers prepared by existing researchers [23-27], as shown in

Table 2, the composite insulating paper prepared in this study exhibits better thermal performance at lower filler contents.

This enhancement is attributed to the good compatibility of boron nitride nano-sheets with the matrix material within the composite aramid paper, leading to the construction of thermal conductive networks within the material. When the nano-filler content is low, the conductive particles may be relatively dispersed within the material, with small, independent thermal conductive chains that do not link to form continuous pathways, thus offering limited improvement in thermal conductivity. However, with further increases in thermal conductive filler content, more thermal conductive molecular chains appear within the material. These chains begin to contact and link with each other, forming a dense, intertwined thermal conductive network that significantly enhances the thermal conductivity of the composite aramid paper.

3.2.3. Dielectric Properties Analysis

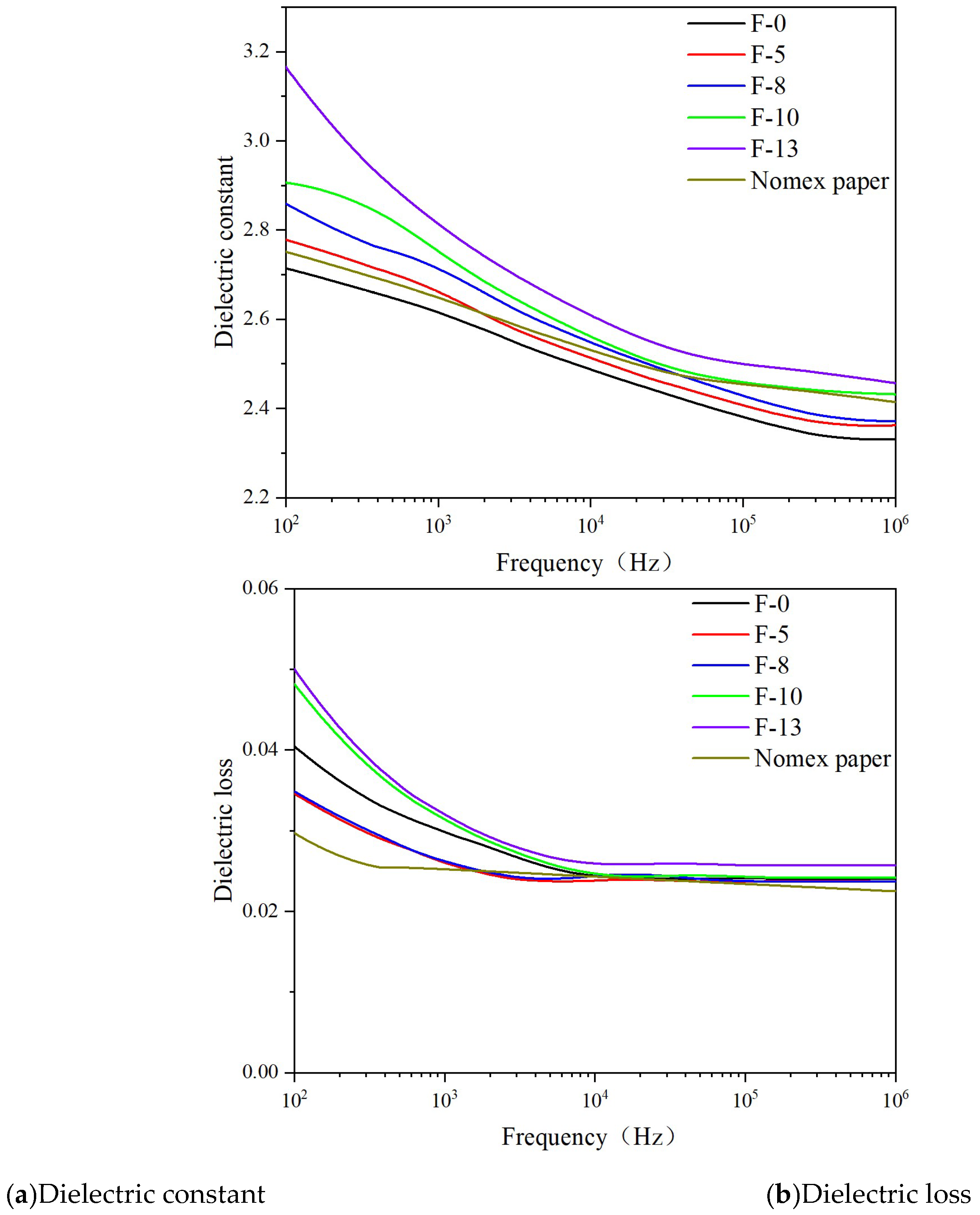

Dielectric parameters are tested using a dielectric spectrometer for different samples. The results are shown in

Figure 9.

From

Figure 9(a), it can be seen that the dielectric constant of all samples increases with the content of K-BNNSs and slightly decreases with increasing the test frequency. This may be because the intrinsic dielectric constant of BN is approximately 4, which is higher than that of PMIA. Hence, a higher K-BNNSs content significantly enhances the dielectric constant of the composite material. Additionally, the modification of BNNSs-OH particles with KH-550 increases the number of polar groups in the composite aramid paper matrix, leading to a higher dipole density and enhanced polarization capability, thus increasing the dielectric constant.

From

Figure 9(b), it is observed that the dielectric loss of the composite aramid paper decreases initially and then increases with the rise in K-BNNSs content. This trend is possibly due to the fact that the K-BNNSs particles at higher K-BNNSs content begin to contact each other within the PMIA matrix. This contact leads to relaxation polarization due to the surface polar groups, thereby increasing the dielectric loss.

3.2.4. Partial Discharge (PD) Characteristics Analysis

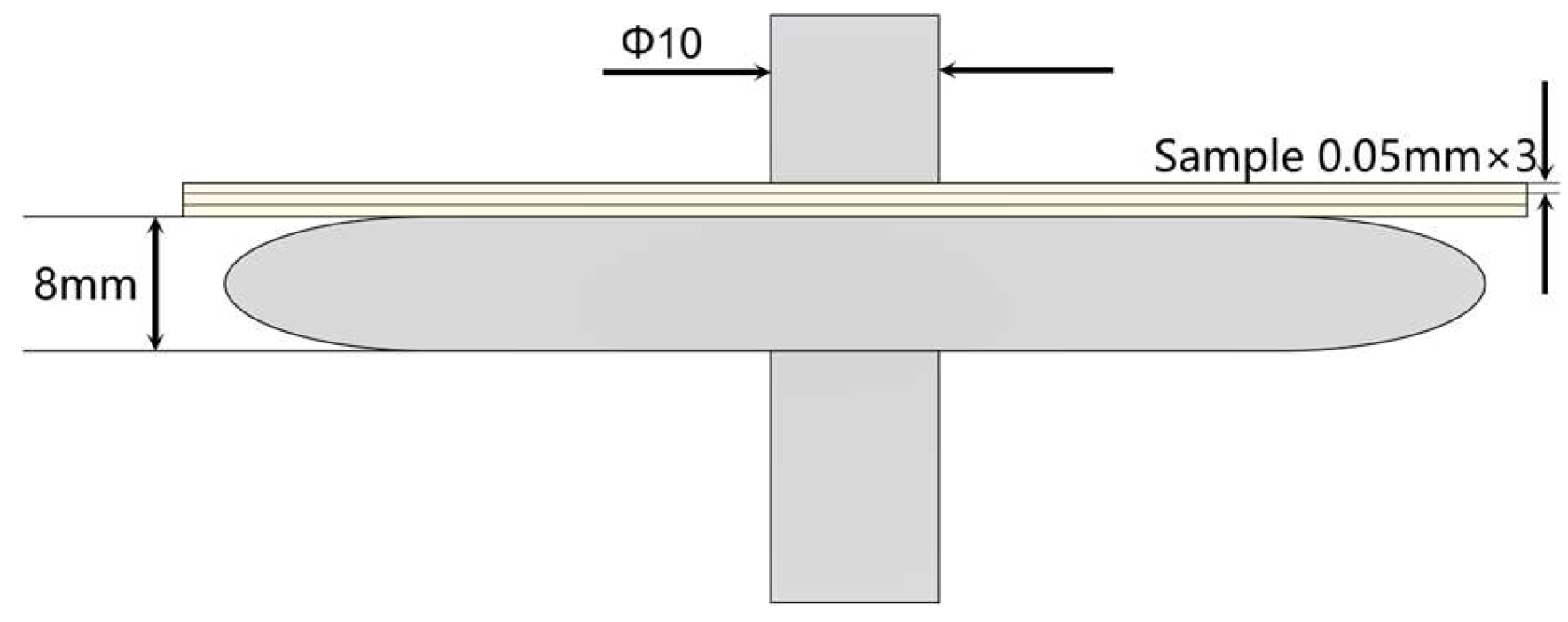

According to the standard GB/T1408.1-2006 [

28], a typical defect model of transformer is designed as shown in

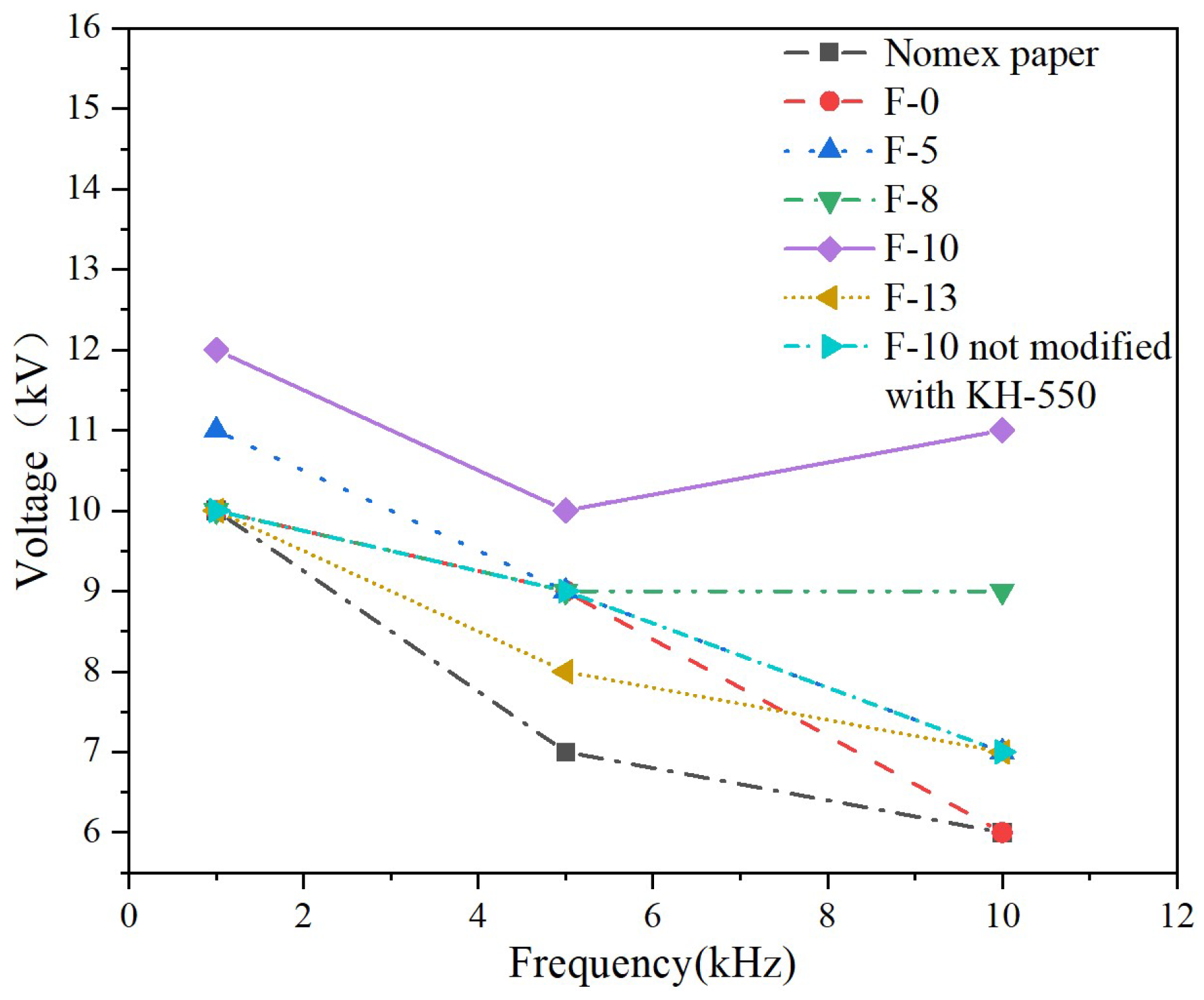

Figure 10. In this model, a step-up voltage method is applied to conduct high-frequency partial discharge tests. The results are shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

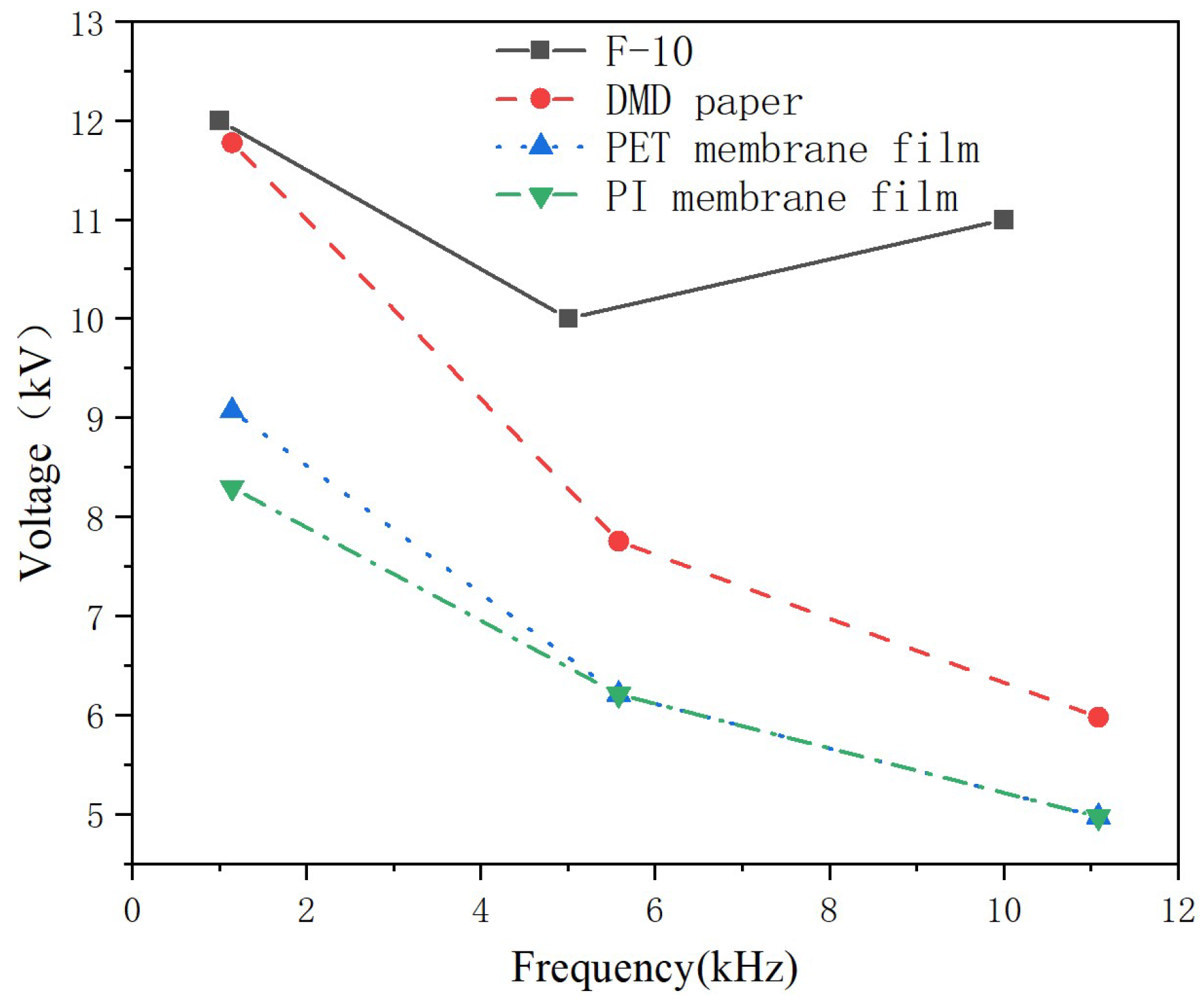

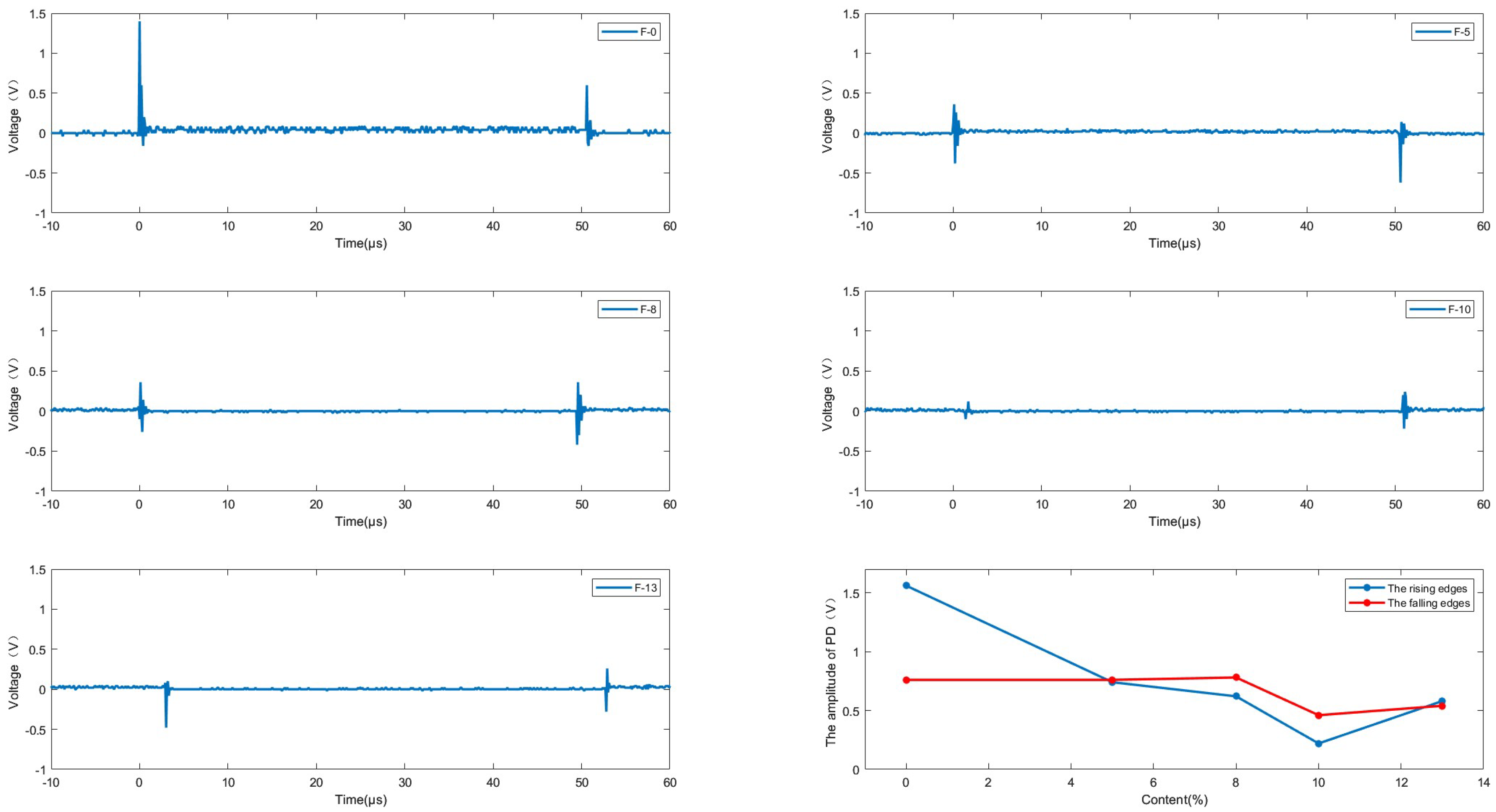

Figure 11 shows the partial discharge amplitude of composite aramid paper with different filler contents at 5kHz and 5kV. The discharge amplitude decreases initially and then increases with increasing filler content, and the discharge amplitude of F-10 sample is the smallest. This indicates that the composite aramid paper with 10% filler content has the best discharge resistance. As seen in

Figure 12, the breakdown voltage of F-10 sample at different frequencies is higher than that of other composite aramid papers. Compared to Nomex paper, the breakdown voltage is increased by an average of 48.73%. Compared with other composite materials prepared by existing researchers, as shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 13, the F-10 sample prepared in this study exhibits a significant improvement in partial discharge breakdown voltage.

Table 3.

Table 3. Insulation material parameter index[

29]

Table 3.

Table 3. Insulation material parameter index[

29]

| Insulating material |

Model number |

Nominal thickness/mm |

Heat resistance level |

Calculate the intensity of ???electric field/(kV/mm) |

| DMD paper |

6641F |

0.30 |

F |

≥30 |

| PET membrane film |

6020 |

0.125 |

E |

≥100 |

| PI membrane film |

6050 |

0.10 |

H |

60~100 |

Figure 13.

Breakdown voltage of PD in different materials[

30]

Figure 13.

Breakdown voltage of PD in different materials[

30]

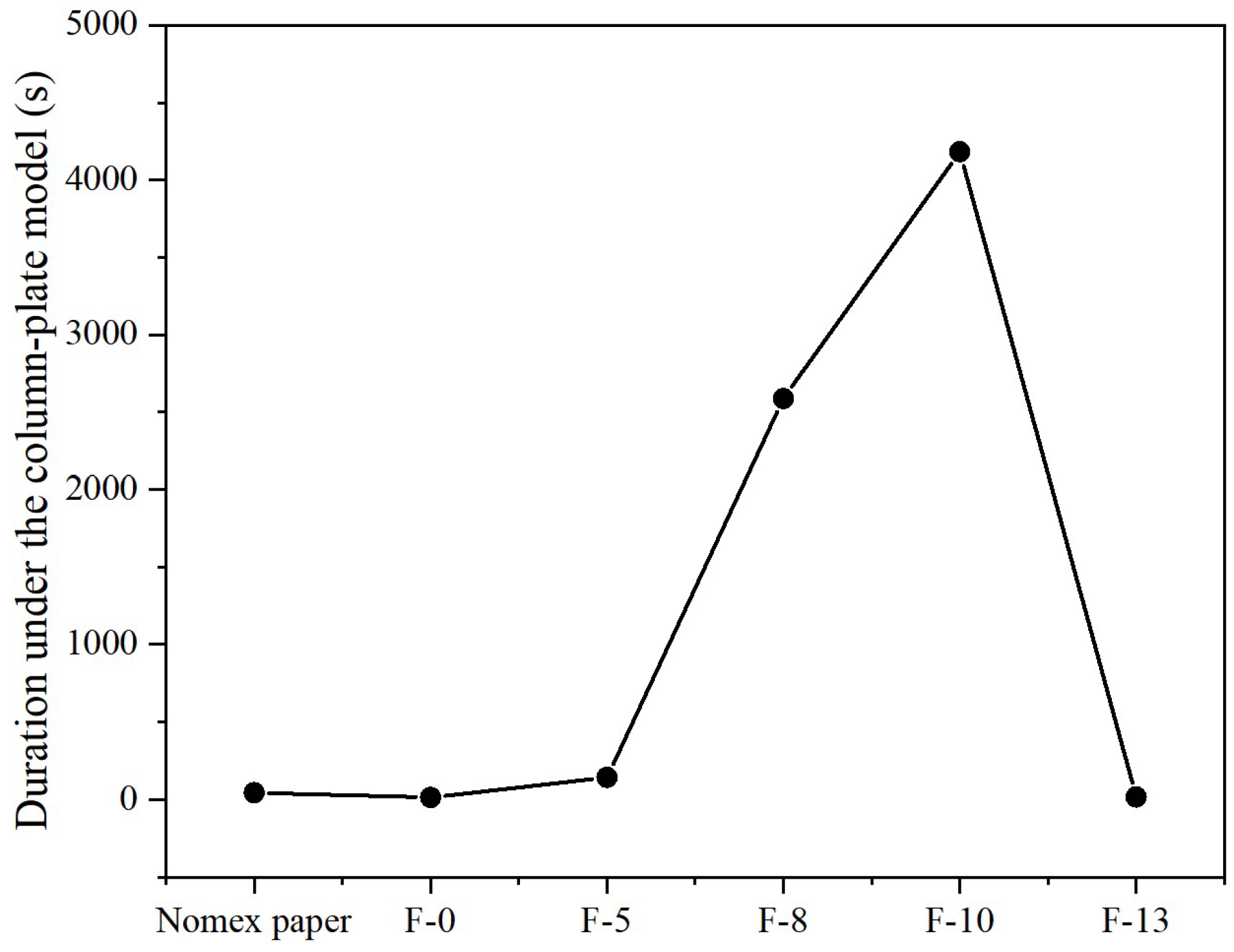

The duration of discharge resistance the composite insulation paper is tested using a constant voltage method under high frequency voltage at 20kHz and 5kV. The results are shown in

Figure 14. It is observed that the duration of discharge resistance for F-10 sample is the longest, which correlates with the results of the partial discharge breakdown voltage test.

In summary, the F-10 sample exhibits the best partial discharge resistance. This is attributed to the formation of a thermal conductive network and the improvement of interfacial bonding ability between the matrix and fillers. On the one hand, a thermal conductive network is constructed within the composite aramid paper due to high thermal conductivity insulating particles (K-BNNSs). As a result, the interfacial thermal resistance of the matrix is alerted, phonon scattering loss during transmission is reduced, the heating rate of the insulation material is declined, the trapping and de-trapping process of active electrons is slowed down. It means that the degree of electric field distortion at the insulation defect is reduced, further inhibiting the generation of partial discharge (shown in

Figure 11-

Figure 14). On the other hand, the interfacial bonding ability between the matrix and fillers increases, the internal defects and traps of the material are reduced. When the electric field strength increases, the electrons are less likely to de-trap, thereby suppressing the occurrence of partial discharge.

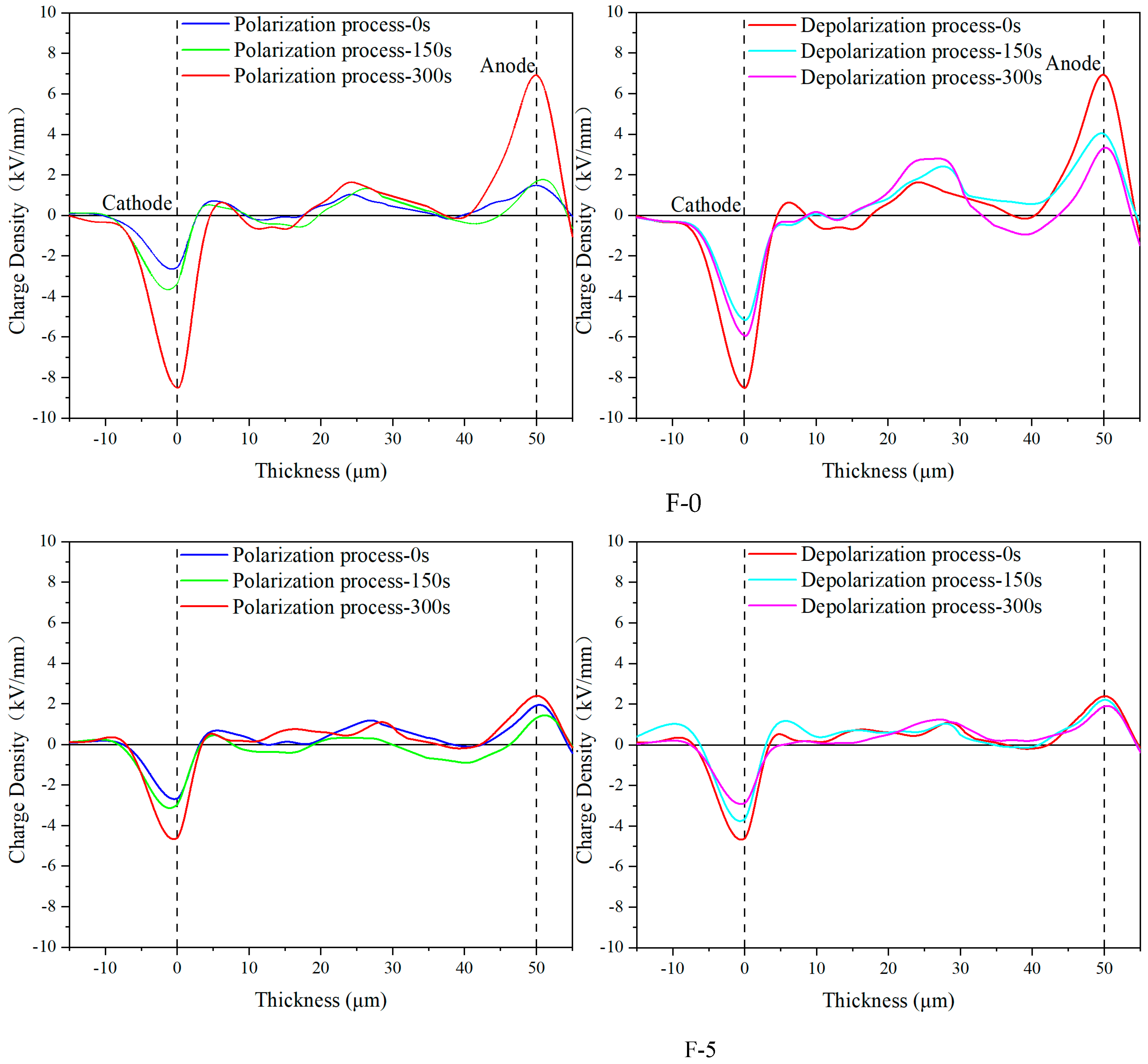

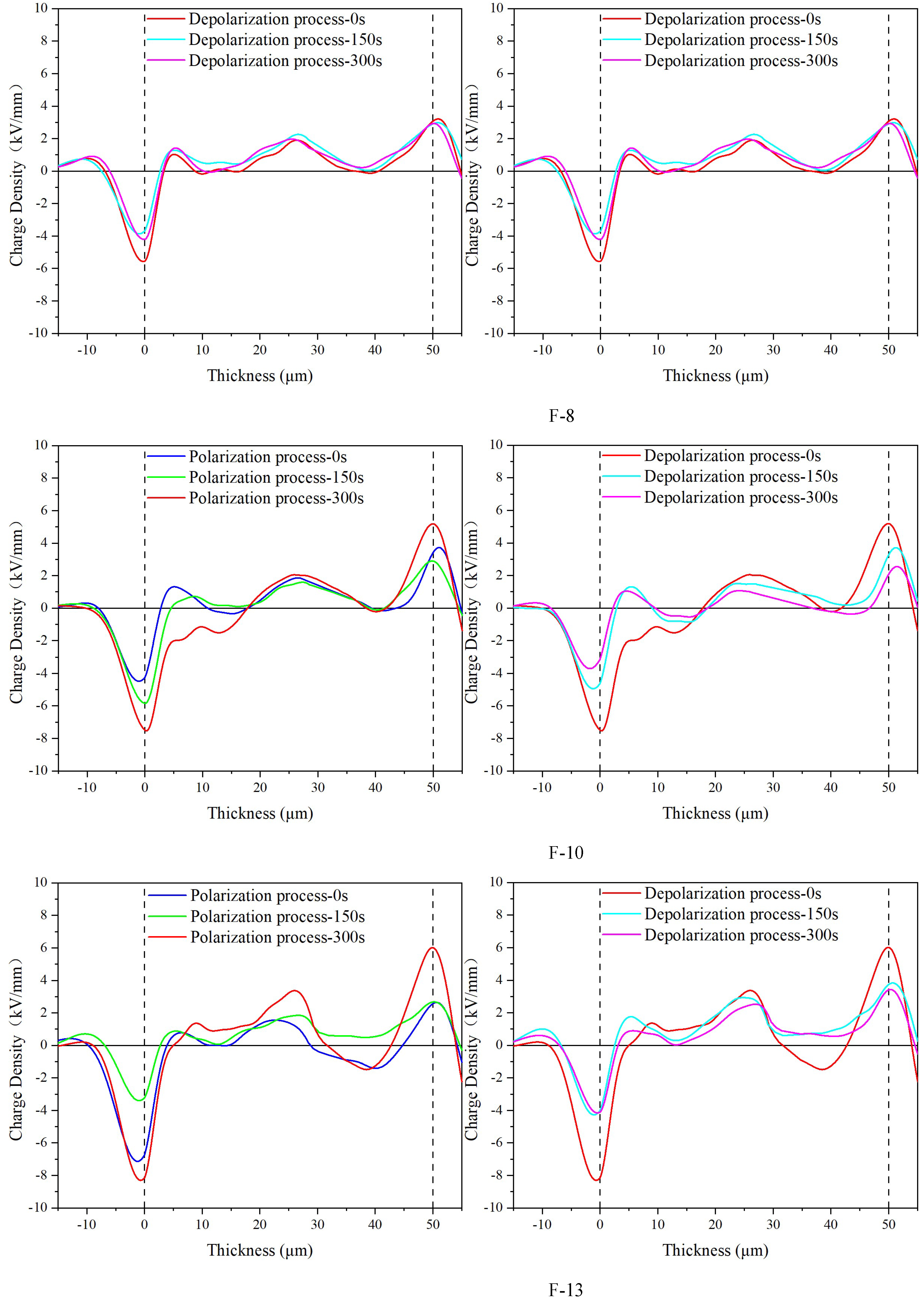

3.2.5. Analysis of space charge characteristics

In order to investigate the effect of K-BNNSs on charge migration during the polarization process of composite aramid paper, different samples are subjected to an electric field strength of 10kV/mm. The result of space charge curves obtained are shown in

Figure 15. It is observed that all samples exhibit charge injection during the polarization process, while charges migrate to the material surface and interior during the depolarization process, accompanied by recombination and dissipation processes.

During the polarization phase, the amount of charge accumulation in the composite aramid paper significantly decreases when the K-BNNSs content is relatively low (0%-8%). The charge accumulation in the F-13 sample is similar to that in the F-0 sample. During the depolarization phase, the charge dissipation also decreases. However, with an increasing content of composite particles (10%-13%), the charge accumulation during the polarization phase increases, as do the charge dissipation during the depolarization phase. This could be because K-BNNSs possess high thermal conductivity insulation properties, enhancing the heat dissipation capability of the composite aramid paper and reducing the internal heat accumulation. The above reason makes charge trapping, de-trapping and migration more difficult, which limits the charge transport process within the composite aramid paper. However, the addition of K-BNNSs increased enhances the number of polar groups within the composite aramid paper, increases the change of charge quantity during the polarization process.

3.2.6. Mechanical Performance Analysis

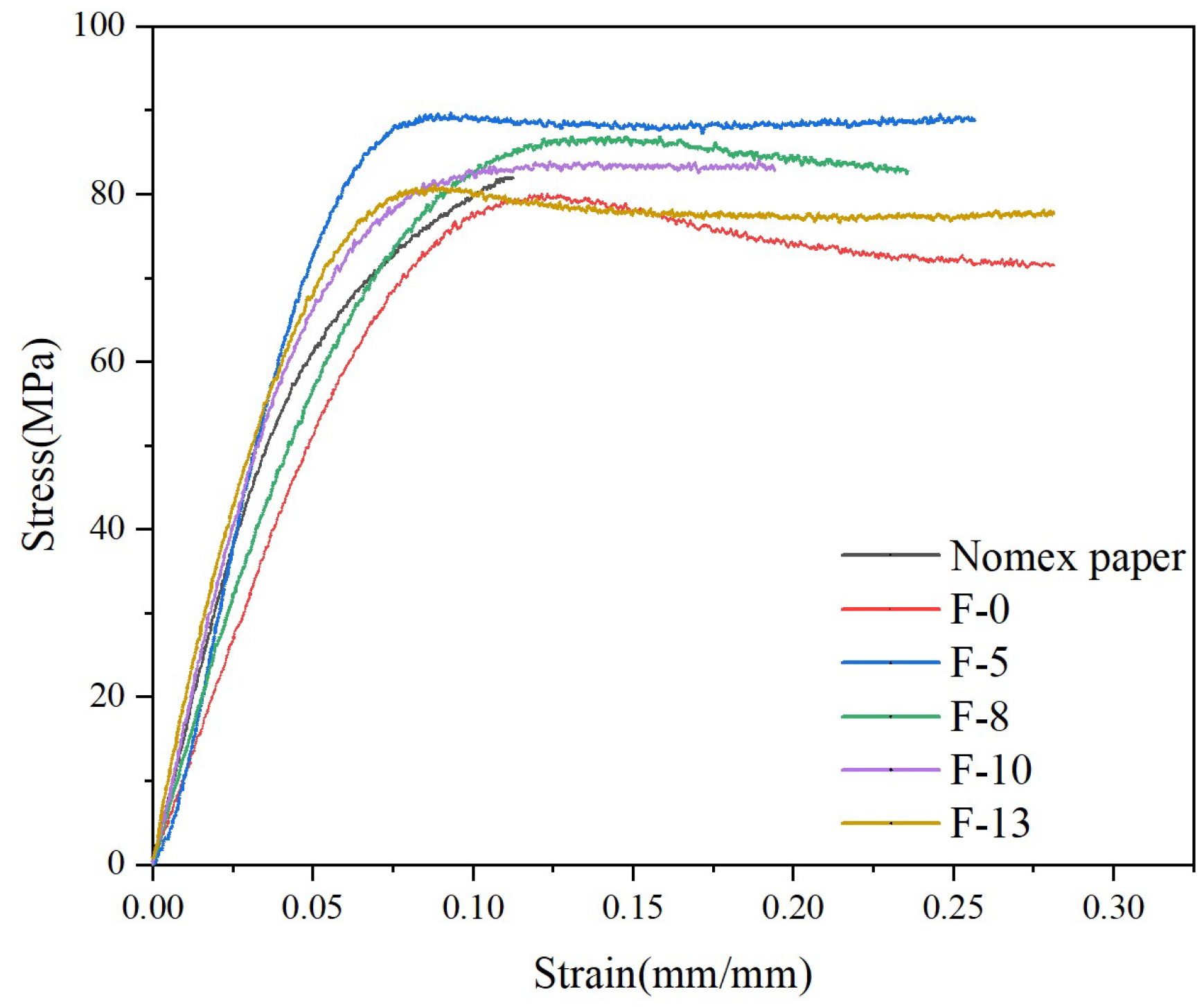

A universal testing machine is used to conduct tensile tests on different samples. The results are shown in

Figure 16.

It can be seen that the composite aramid paper with 5% K-BNNSs nano-filler exhibits the best mechanical performance, with a tensile strength of 89.69 MPa. As the nano-filler content increased, the mechanical performance gradually declines, but all samples still outperform pure meta-aramid paper. This may be attributed to the addition of minor amounts of well-compatible, small-volume second-phase particles, which can effectively improve internal defects in the matrix, such as pores and bubbles, thereby increasing the material's density. However, with the further increase of nano-filler, the volume fraction of filler particles in the material rises, leading to a rougher contact surface between the nano-filler and the matrix and a decline in mechanical performance.

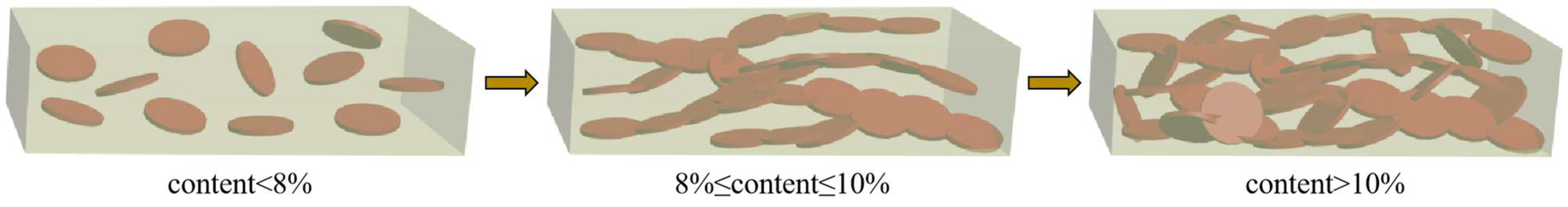

4. Mechanism Analysis

4.1. Influence of Thermal Conductive Network on the Performance of Composite Aramid Paper

As the content of the composite particles K-BNNSs increases, a complete thermal conductive network gradually forms within the composite aramid paper, as shown in

Figure 17. When the composite particle content is low (<8%), the particles cannot form thermal pathways within the matrix and are merely dispersed throughout the material. This results in a minimal improvement in the thermal conductivity of the insulating paper, which consistent with the analysis results shown in

Figure 8.

When the composite particle content is between 8% and 10%, the particles form a complete thermal conductive network within the matrix. One reason is that the composite particles show a high intrinsic thermal conductivity and constitute a complete thermal conductivity network, which is conducive to the heat propagation inside the material. This provides a path for the propagation of molecular thermal vibration phonons and improves the average free travel of phonons inside the material. It presents that the thermal conductivity increases significantly, the heat dissipation capacity of the material improves, the heat concentration inside the material reduces, and the deterioration of various materials is inhibited. The other reason is that the increased number of thermal conductive networks within the composite aramid paper decreases the interfacial thermal resistance of the matrix. This prevents excessive heat accumulation within the insulating material, partially suppressing the movement of active electrons under an external electric field. It means that the field intensity concentration is reduced and the partial discharge activity is inhibited. However, as the composite particle content exceeds 10%, particle aggregation may occur within the aramid matrix, leading to an increase in defects and promoting partial discharge, as consistent with the results shown in

Figure 12.

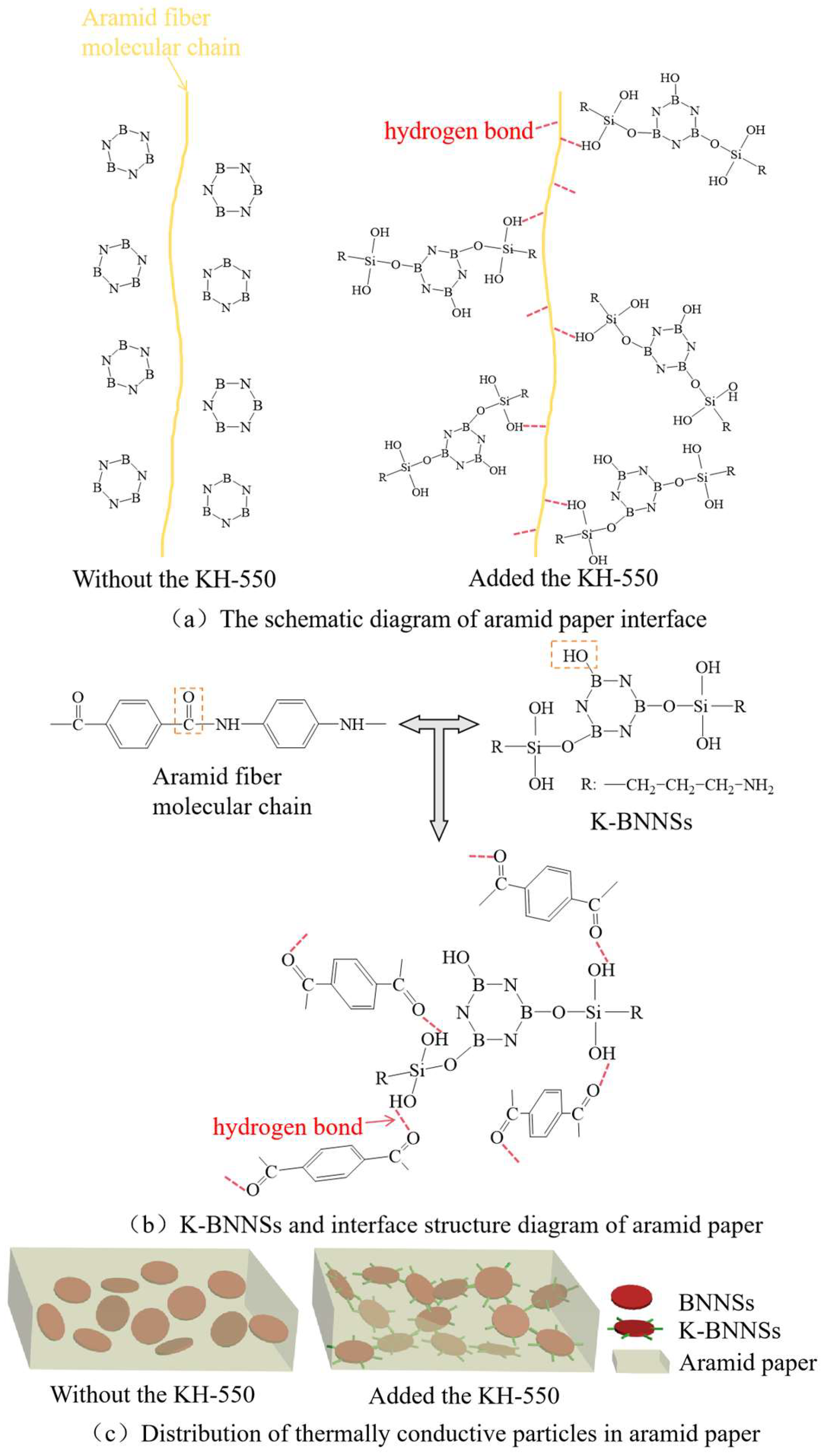

4.2. Influence of Hydrogen Bonds on the Performance of Composite Aramid Paper

Due to the absence of KH-550 modified particles, the compatibility between the composite aramid paper matrix and the composite filler particles is poor. This is evident from the lack of tight connections between the filler molecules and aramid fiber molecules, as well as among the filler particles themselves (see

Figure 18). Consequently, numerous defects are present in the composite aramid paper, as shown in

Figure 5(e). When an electric field is applied, charge carriers are easily trapped in these defects, as indicated in

Figure 19. Upon reaching the critical field strength, partial discharge readily occurs at these defect sites. Further increasing the field strength enhances the probability of trapping, de-trapping, migration and recombination of charge carriers at these defects, accelerating the generation of partial discharge as seen in

Figure 11 to

Figure 14.

By adding KH-550, the BNNSs-OH particles are functionalized, so that a large number of hydroxyl groups are filled around the composite particles. These hydroxyl groups readily form hydrogen bonds with aramid fiber molecules (see

Figure 18), enhancing the interfacial bonding force between the matrix and composite particles, and thereby reducing defects in the composite aramid paper (see

Figure 5c). When an electric field is applied, the molecular chains within the material are less likely to be disrupted, inhibiting the occurrence of partial discharge. This improvement results in higher breakdown voltage and longer the duration of discharge resistance.

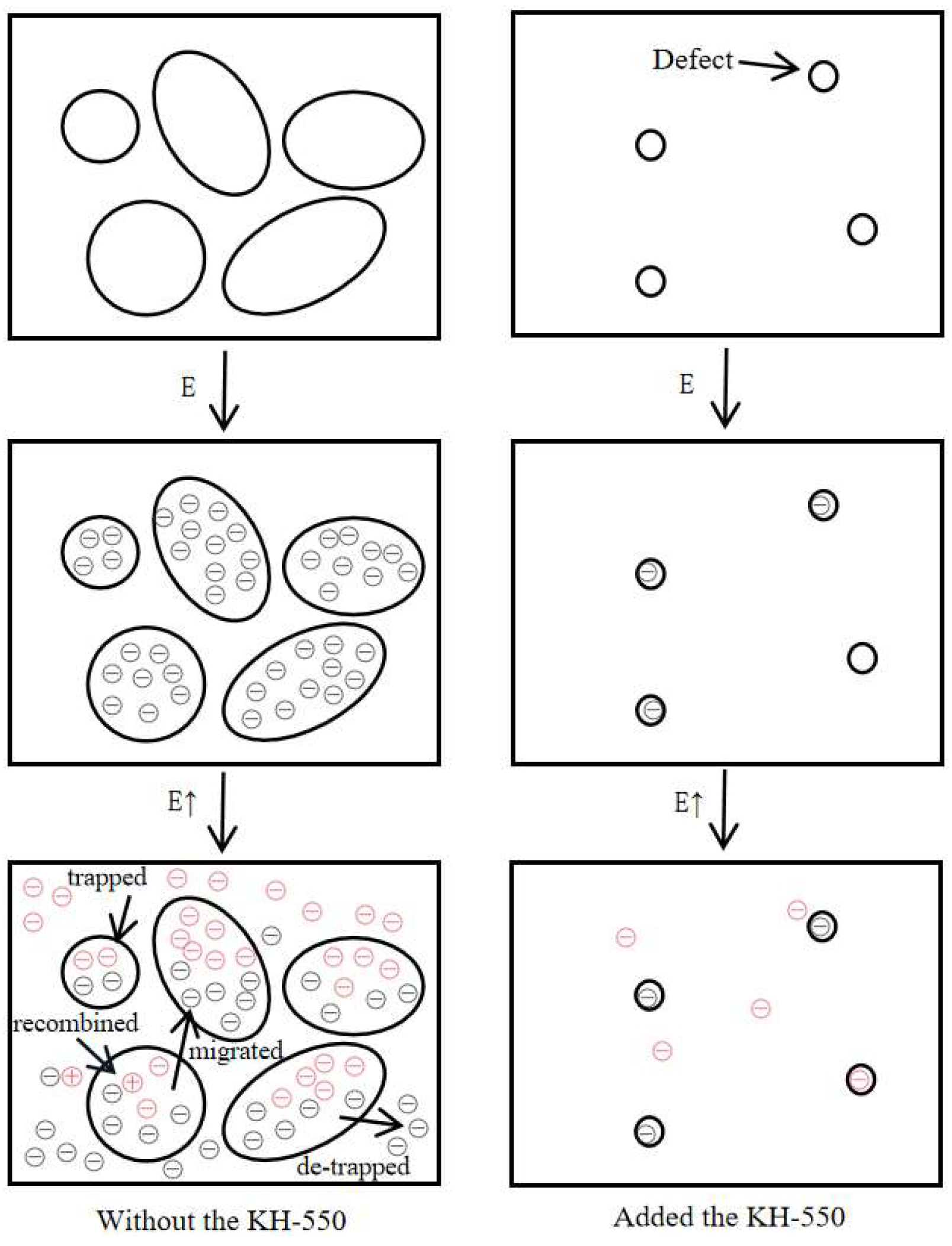

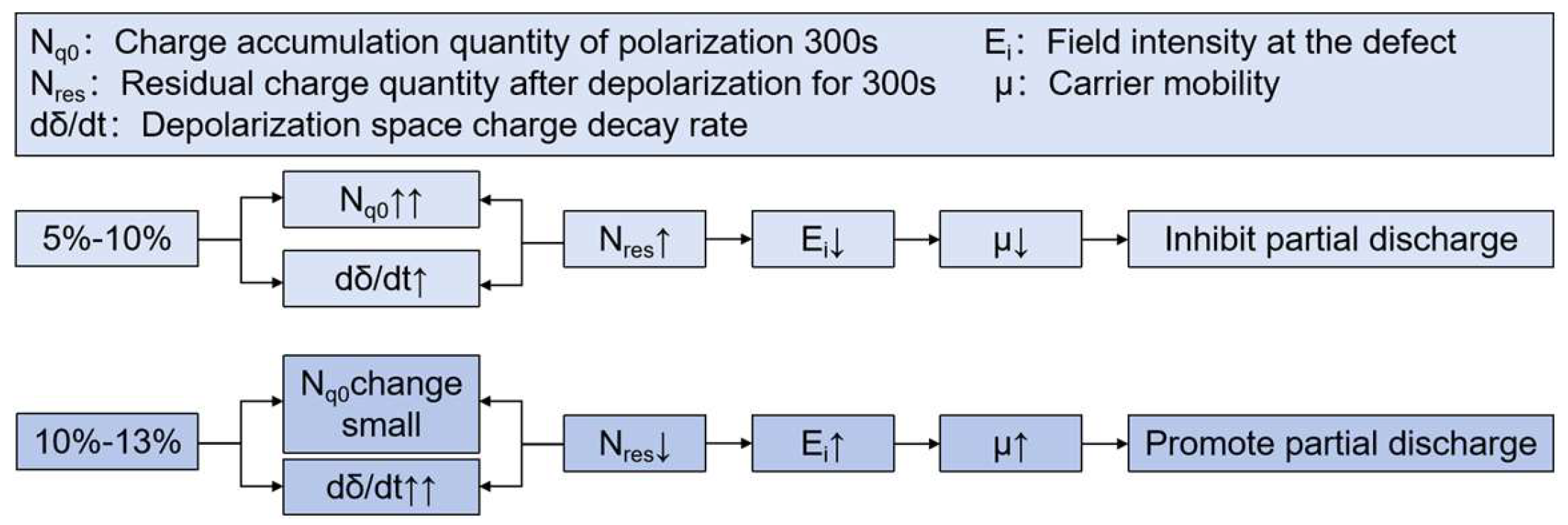

4.3. Influence of Charge Transport on the Performance of Composite Aramid Paper

The mechanism of space charge transport in composite aramid paper is analyzed in

Figure 20. When the filler particle content is between 5% and 10%, both the charge accumulation during polarization and the charge decay rate during depolarization increase with higher filler content. The increase in charge accumulation is more pronounced, leading to a higher residual charge amount. It indicates that the electric field intensity at defect is reduced, carrier mobility is decreased and partial discharge is suppressed.

When the filler particle content is between 10% and 13%, the charge accumulation during the polarization stage does not change significantly with increased filler content. However, the charge decay rate during the depolarization stage further increases, reducing the residual charge amount. It indicates that the electric field intensity at defect is increased, carrier mobility is increased and partial discharge is promoted. As a result, the amplitude of partial discharge is increased, the duration and breakdown voltage of partial discharge are lowered, which consistent with the partial discharge characteristics analysis in

Figure 11 to

Figure 14.

5. Conclusions

1) Through characterization methods such as FTIR, XRD, and TEM analysis, it has been confirmed that boron nitride nanosheets (BNNSs) have been successfully exfoliated and modified by a silane coupling agent. A comparison between composite aramid papers containing BNNSs and K-BNNSs particles reveals that the silane coupling agent KH-550 significantly improves the interfacial compatibility between composite particles and the aramid paper matrix, reducing internal defects within the composite aramid paper.

2) When the content of K-BNNSs composite particles is 10%, the composite aramid paper exhibits optimal comprehensive performance. Compared to Nomex paper, the breakdown voltage of partial discharge is increased by an average of 48.73%, thermal conductivity of plane thermal conductivity and through-plane is improved by 502.86% and 633.13%, respectively, and tensile strength is increased by 2.49%.

3) The superior performance of F-10 composite aramid paper is attributed to two main reasons. First, a complete thermal conductive network is formed within the composite aramid paper matrix at this filler content, reducing matrix interfacial thermal resistance and enhancing the thermal conductivity of the material. Second, the addition of composite particles introduces numerous hydrogen bonds, strengthening the interfacial bonding force between the aramid matrix and composite particles. It indicates that the energy barriers for charge trapping and de-trapping is increased, charge migration at defect is inhibited and the activity of partial discharge is suppressed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-N.L. and T.Q.; methodology, T.Q.; software, W.-X.Z. and Y.-B.W.; validation, X.-N.L., T.Q. and Q.W.; formal analysis, T.Q.; investigation, T.Q.; resources, X.-N.L.; data curation, T.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Q.; writing—review and editing, T.Q.; visualization, X.-N.L.; supervision, X.-N.L. and Y.-H.C.; project administration, X.-N.L.; funding acquisition, X.-N.L., K.-L.L. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52267011, 62366031), Lanzhou Talent Innovation and Entrepreneurship (2022-RC-17), the Electric Power Research Institute of State Grid Ningxia Electric Power Company (5229DK23000M), Hongliu Outstanding Young Talent of Lanzhou University of Technology (062303), Gansu Provincial Key Laboratory of Advanced Control of Industrial Processes Open Fund (2022KX06, 2022KX09), and Gansu Youth Science and Technology Fund (23JRRA835).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, A.Q.; Crow, M.L.; Heydt, G.T.; Zheng, J.P.; Dale, S.J. The Future Renewable Electric Energy Delivery and Management (FREEDM) System: The Energy Internet. Proc. IEEE 2010, 99, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Qin, T.; Liu, K.; Yang, Y.; Wu, G. Surface Degradation of Oil-Immersed Nomex Paper Caused by Partial Discharge of High-Frequency Voltage. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 52, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, X.; Huang, A.Q.; Burgos, R. Review of Solid-State Transformer Technologies and Their Application in Power Distribution Systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2013, 1, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Liu, K.; Yang, Y. Effect of high-frequency surface charge transport on partial discharge of oil-paper insulation. Chinese Journal of Electrical Engineering 2022, 42, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, T.; Zhu, M.; Wu, G. The Physical Mechanism of Frequency-Induced Inflection Point for Oil-Paper Insulation Under High-Frequency Square-Wave Voltage. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2022, 50, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Lin, J.; Wang, Z. Impact of the phenyl thioether contents on the high frequency dielectric loss characteristics of the modified polyimide films. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2018, 360, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, L.; Khan, M.Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Q.; He, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Li, J. Accelerated Charge Dissipation by Gas-Phase Fluorination on Nomex Paper. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z. Preparation of PMIA dielectric nanocomposite with enhanced thermal conductivity by filling with functionalized graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid fillers. Appl. Nanosci. 2019, 9, 1743–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Min, D.M.; GAO, Z.W. ; Study on the influence of PEI/BNNS composite dielectric trap distribution on breakdown probability and energy storage performance. Journal of Electrical Engineering 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, G.F.; Zhang, J.J.; Xu, Z.W. Effect of BN fiber on the thermal conductivity and insulation properties of graphene microchips/polypropylene composites. Journal of Composite Materials 2020, 37, 546–552. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Huang, T.; Yao, Y.; Xu, W. Effects of 2D boron nitride (BN) nanoplates filler on the thermal, electrical, mechanical and dielectric properties of high temperature vulcanized silicone rubber for composite insulators. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 774, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, L. Bi-directional high thermal conductive epoxy composites with radially aligned boron nitride nanosheets lamellae. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 198, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, B.; Jiang, P. Highly Thermally Conductive Yet Electrically Insulating Polymer/Boron Nitride Nanosheets Nanocomposite Films for Improved Thermal Management Capability. ACS Nano 2018, 13, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.Z.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, P.K. Three-dimensional boron nitride structure and its thermally conductive and insulating polymer nanocomposites. Journal of Electrical Engineering 2021, 16, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, R.J.; Lu, C.; Wu, W.Q. Insulating properties of nano-TiO2 modified insulating paper. High Voltage Technology 2014, 40(07): 1932-1939.

- Zha, J.; Chen, G.; Dang, Z.; Yin, Y. The influence of TiO2 nanoparticle incorporation on surface potential decay of corona-resistant polyimide nanocomposite films. J. Electrost. 2011, 69, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.C.; Zhu, M.Y.; Ruan, H.O. Effect of silane coupling agent types on the electrical properties of nano-TiO2/meta-aramid composite insulating paper. Insulation Materials 2023, 56, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.H.; Xie, Z.Q.; Li, Q.M. High-frequency dissipation characteristics of surface charge on the modified epoxy resin insulation surface with dopamine-grafted nano-BN. Journal of Electric Engineering Technology 2023, 38, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.K.; Zhang, G.Q.; Li, K. The influence of epoxy pre-treatment of insulation materials of high-frequency transformer on discharge characteristics. New Technologies of Electric Engineering and Energy 2020, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.M.; Liu, W.J.; Han, S. Analysis of partial discharge characteristics in combined aging of epoxy resin insulation high-frequency electrothermal. High Voltage Technology 2015, 41, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Shahram, S.; Alireza, C.N. Fabricating boron nitride nanosheets from hexagonal BN in water solution by a combined sonication and thermal-assisted hydrolysis method.Ceramics International 2020, 47, 11122-11128.

- Zhen, H.C.; J, A.O.; Jaeton, A.G. Large scale thermal exfoliation and functionalization of boron nitride. Small (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany) 2014, 10, 2352–2355. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Z.H.; Fang, G.Q. Preparation and performance research of thermally conductive boron nitride composite insulating paper. Journal of Chinese Papermaking 2019, 34, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.H.; Teng, F.L.; Zhou, R. Structural design and performance analysis of high thermal conductivity BNNS/ANF composite insulating paper. Engineering Science and Technology 2023, 55, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, B.M.; Yong, S.Z.; Kun, P.R. Highly Thermal Conductivities, Excellent Mechanical Robustness and Flexibility, and Outstanding Thermal Stabilities of Aramid Nanofiber Composite Papers with Nacre-Mimetic Layered Structures. ACS applied materials interfaces 2020, 12, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, C.Z.; Hu, F.Y.; Chi, C.L. Preparation and thermal conductivity of poly-m-phenylene isophthalamide-based composite dielectric. New Chemical Materials 2022, 50, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, G.Y.; Hu, F.Y.; Hu, Z.M. Preparation and thermal conductivity of barium titanate-boron nitride/poly(m-phenylene isophthalamide) composite dielectric. Journal of Composite Materials 2022, 39, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar]

- China National Standardization Administration Committee. GB/T 1408.1-2006 Test methods for electrical strength of insulating materials Part 1: Test at power frequency. Beijing: China Standard Press, 2006.

- Li, Y.B.; Chen, J.S. Insulation Materials Inspection Manual. Beijing, China, Electric Power Press 2010.

- Zhao, Y.K.; Zhang, G.Q.; Han, D. Method for de termining high-frequency transformer winding insulation test voltage based on material insulation life. Journal of Electrical Engineering 2020, 35, 2932–2939. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the preparation of composite aramid paper

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the preparation of composite aramid paper

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of different samples

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of different samples

Figure 3.

XRD spectra of BN, BNNSs, BNNSs-OH andK-BNNSs.

Figure 3.

XRD spectra of BN, BNNSs, BNNSs-OH andK-BNNSs.

Figure 4.

(a), (b) are TEM patterns of BN and BNNSs; (c) and (d) are electron diffraction patterns of BN and BNNSs

Figure 4.

(a), (b) are TEM patterns of BN and BNNSs; (c) and (d) are electron diffraction patterns of BN and BNNSs

Figure 5.

(a) F-0 surface; (b) F-0 cross-section; (c) F-10 surface; (d) F-10 cross-section; (e) F-10 surface not modified with KH-550; (f) F-10 cross-section not modified with KH-550

Figure 5.

(a) F-0 surface; (b) F-0 cross-section; (c) F-10 surface; (d) F-10 cross-section; (e) F-10 surface not modified with KH-550; (f) F-10 cross-section not modified with KH-550

Figure 6.

EDS analysis of F-10 composite aramid paper selection

Figure 6.

EDS analysis of F-10 composite aramid paper selection

Figure 7.

TGA curves of composite aramid paper with different contents of K-BNNSs

Figure 7.

TGA curves of composite aramid paper with different contents of K-BNNSs

Figure 8.

In-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity of different samples

Figure 8.

In-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity of different samples

Figure 9.

Dielectric constant and dielectric loss for different samples

Figure 9.

Dielectric constant and dielectric loss for different samples

Figure 10.

Typical column-plate model

Figure 10.

Typical column-plate model

Figure 11.

The amplitude of PD

Figure 11.

The amplitude of PD

Figure 12.

Breakdown voltage of PD in different samples under high-frequency voltages

Figure 12.

Breakdown voltage of PD in different samples under high-frequency voltages

Figure 14.

The duration of partial discharge voltage resistance of different materials at 20kHz

Figure 14.

The duration of partial discharge voltage resistance of different materials at 20kHz

Figure 15.

Space charge curves of different insulation papers under 10kV/mm field strength

Figure 15.

Space charge curves of different insulation papers under 10kV/mm field strength

Figure 16.

Stress-strain curves for different samples

Figure 16.

Stress-strain curves for different samples

Figure 17.

Thermal conduction network evolution

Figure 17.

Thermal conduction network evolution

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram of the interface of composite aramid paper

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram of the interface of composite aramid paper

Figure 19.

The effect mechanism of KH-550 on partial discharge

Figure 19.

The effect mechanism of KH-550 on partial discharge

Figure 20.

Charge transport mechanism

Figure 20.

Charge transport mechanism

Table 1.

The main materials.

Table 1.

The main materials.

| Material name |

Specification |

Manufacturer |

| Boron nitride(BN) |

Particle size 1μm |

Aladdin reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. |

| Polymeric m-phenylenediamine solution(PMIA) |

Solid content 20% |

Taihe New Material Group Co., Ltd. |

| N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) |

Analytical purity(AR) |

China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. |

| Double-distilled water |

|

Shuyang Kehong Trading Co., Ltd. |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene filter membrane |

Aperture 0.1μm |

German Filter New Materials Technology Co., Ltd. |

| Silane coupling agent KH-550 |

Chemically pure |

Nanjing Chuanshi Chemical Auxiliary Co., Ltd. |

Table 2.

Thermal conductivity of different composite insulating papers

Table 2.

Thermal conductivity of different composite insulating papers

| Composite aramid paper |

Composite particle content |

The in-plane thermal conductivity |

The through-plane thermal conductivity |

| NBKP/h-BN [23] |

40% |

0.682W/(m·K) |

|

| BNNS/ANF[24] |

30% |

|

5.31 W/(m·K) |

| (BNNS@PDA)/ANF[25] |

50% |

0.62 W/(m·K) |

3.94 W/(m·K) |

| BTCN/PMIA [26] |

10% |

0.62 W/(m·K) |

|

| D@BTW-fBNNSs[27] |

15% |

0.57 W/(m·K) |

|

| Sample of this article |

10% |

0.76 W/(m·K) |

7.64W/(m·K) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).