Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A unique list of heuristic criteria focused on the evaluation of systems for people with cognitive learning disabilities and additionally for older people.

- An objective numerical index of cognitive usability and accessibility evaluation.

- A case study that evaluates the cognitive usability and accessibility heuristics.

- A ranking of usable and accessible systems for people with cognitive disabilities.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Usability and Accessibility, Context and Evaluation

2.2 Usability and Accessibility Metrics and Generative AI

3. Designing a Set of Cognitive Usability and Accessibility Heuristics

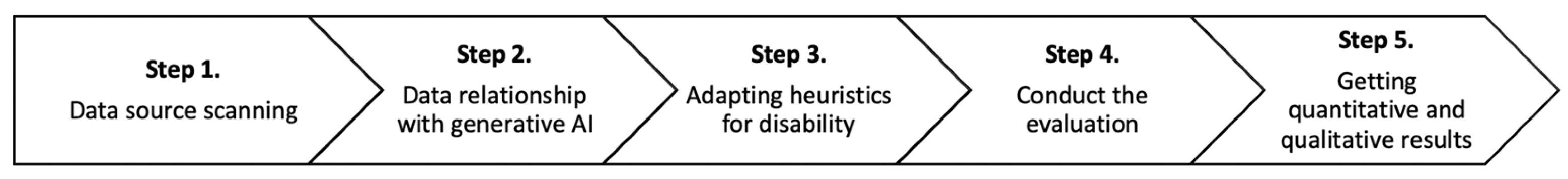

Step 1. Exploring the Data Source

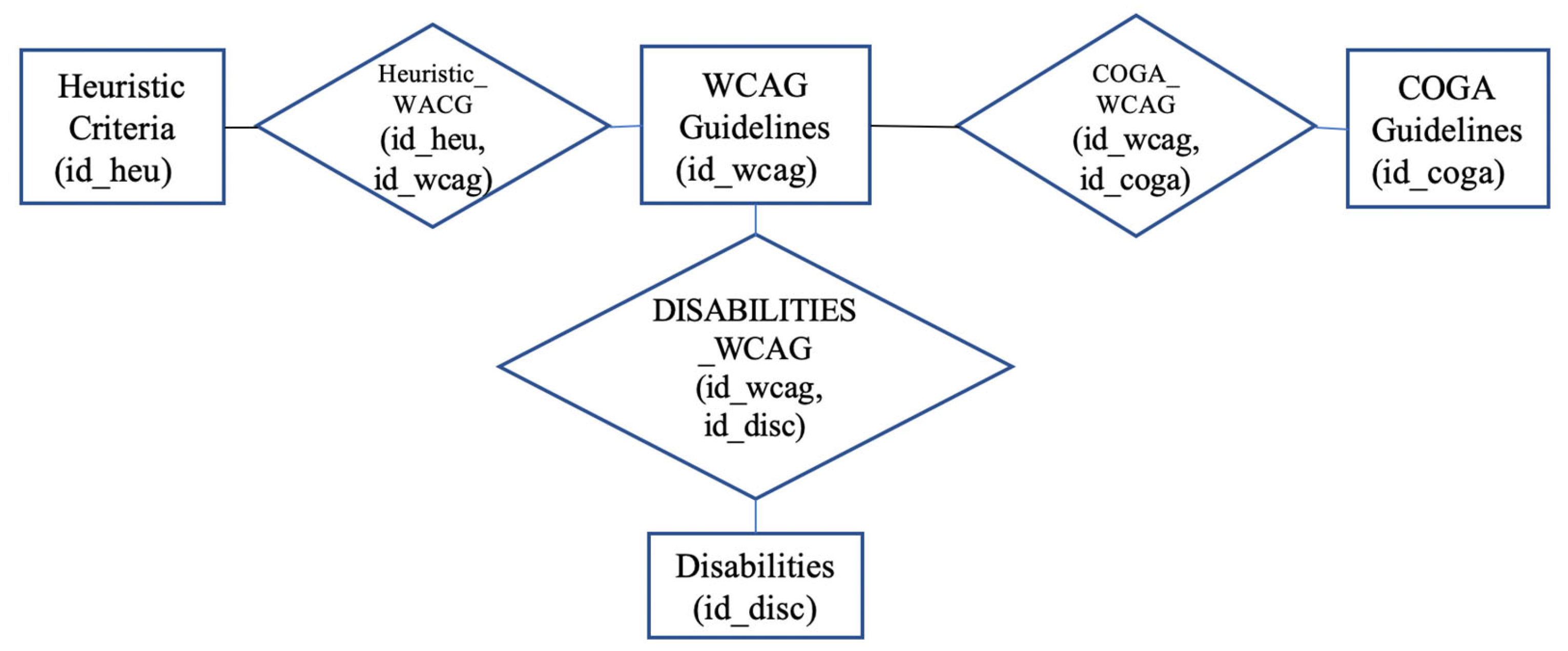

- Table: ‘Heuristic Criteria’: The heuristic principles developed by Granollers [44] were selected because they are a generic set of heuristics to evaluate interactive systems, including web pages, and generates an index that indicates the level of usability of the analyzed system.

- Table: ‘WCAG Guidelines’: WCAG 2.2 guidelines [33] were chosen as the latest W3C recommendation at the time of writing this paper.

- Table ‘COGA Guidelines’: ‘Making Content Usable for People with Cognitive and Learning Disabilities’[34] by focusing on assessment related to cognitive impairment.

- Table: ‘Disabilities’: List of disabilities contained in the WCAG 2.2 guidelines, document “understanding” [45] in order to know that WCAG 2.2 guidelines impact certain users with disabilities.

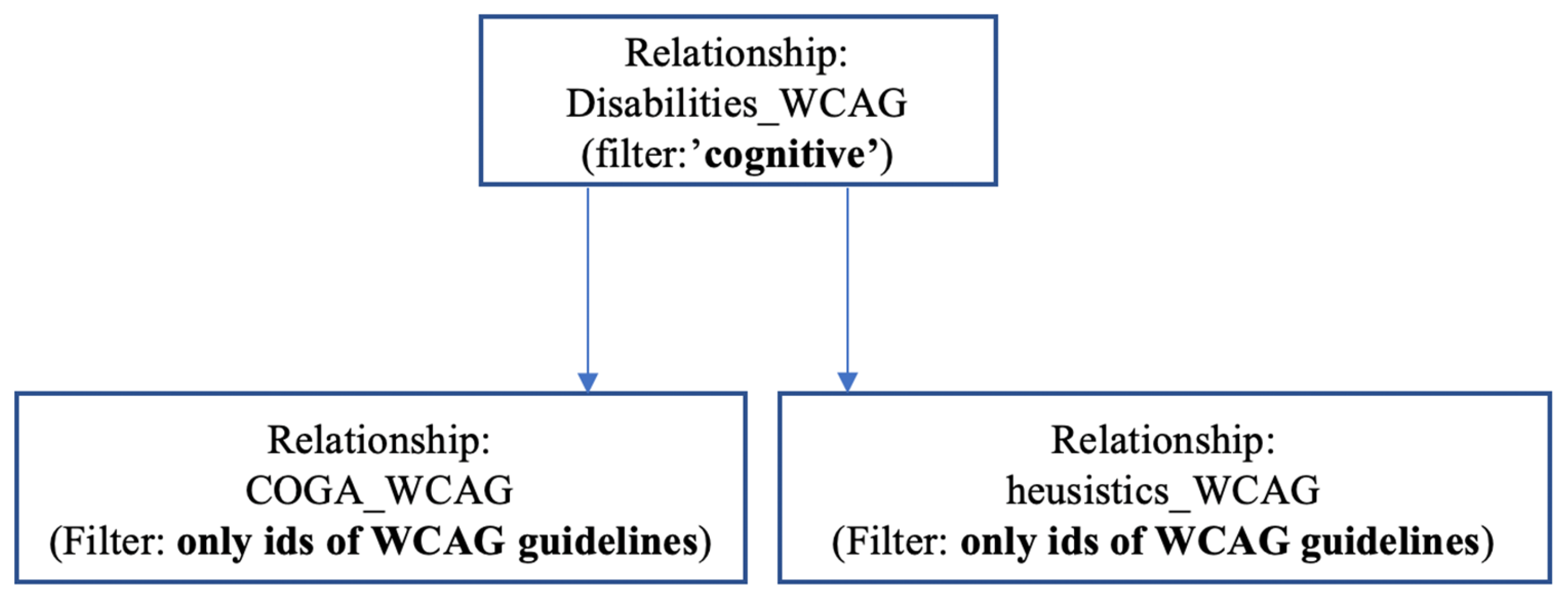

Step 2. Obtaining Criteria According to the Data Relationship with Generative AI

- Disabilities and WCAG guidelines (disabilities-WCAG relationship)

- Heuristic criteria and WCAG guidelines (Heuristic-WCAG relationship)

- COGA guidelines and WCAG guidelines (COGA-WCAG relationship)

- First, we introduce the table “Heuristics criteria” into Generative AI tool

- After, we wrote this prompt in ChatGPT:

- First, we introduced the table “COGA guidelines” into ChatGPT

- Afterwards, we wrote this prompt:

Step 3. Adapting Heuristics for Disability

Step 4. Conducting the Assessment

- ‘pass’, indicating that it is not a problem in the assessed system

- ‘fail' indicates that the assessed criteria is not met in the assessed system.

- ‘NA' indicates “not applicable” and is selected by the assessor when the criteria cannot be assessed in the system.

- ‘pass’ is a 1 when the criterion is met in the system.

- ‘fail’ is a 0 when the criterion is not fulfilled in the system.

- ‘NA’ is an empty field and will not be considered in the computation of the “U+Aindex”.

Step 5. Quantitative and Qualitative Results

4. Use Case

4.1. Scope of the study

- -

- Fundacio Viver Bell-lloc- https://www.vivelloc.cat/ca/

- -

- Fundacio auria: https://www.auria.org/

- -

- Imserso: https://imserso.es/web/imserso

- -

- Seniortic- https://www.seniortic.org/

4.2. Experimentation

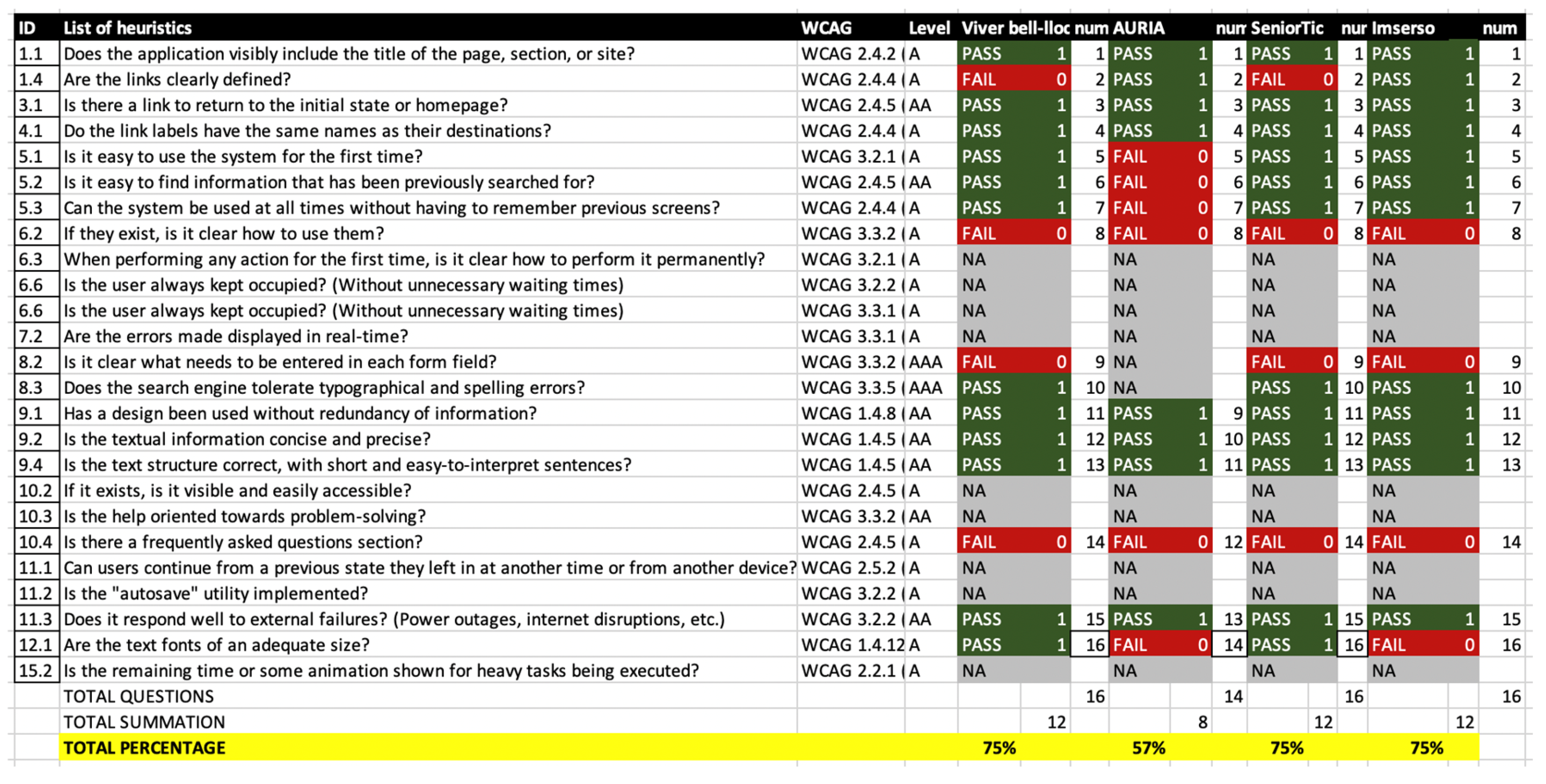

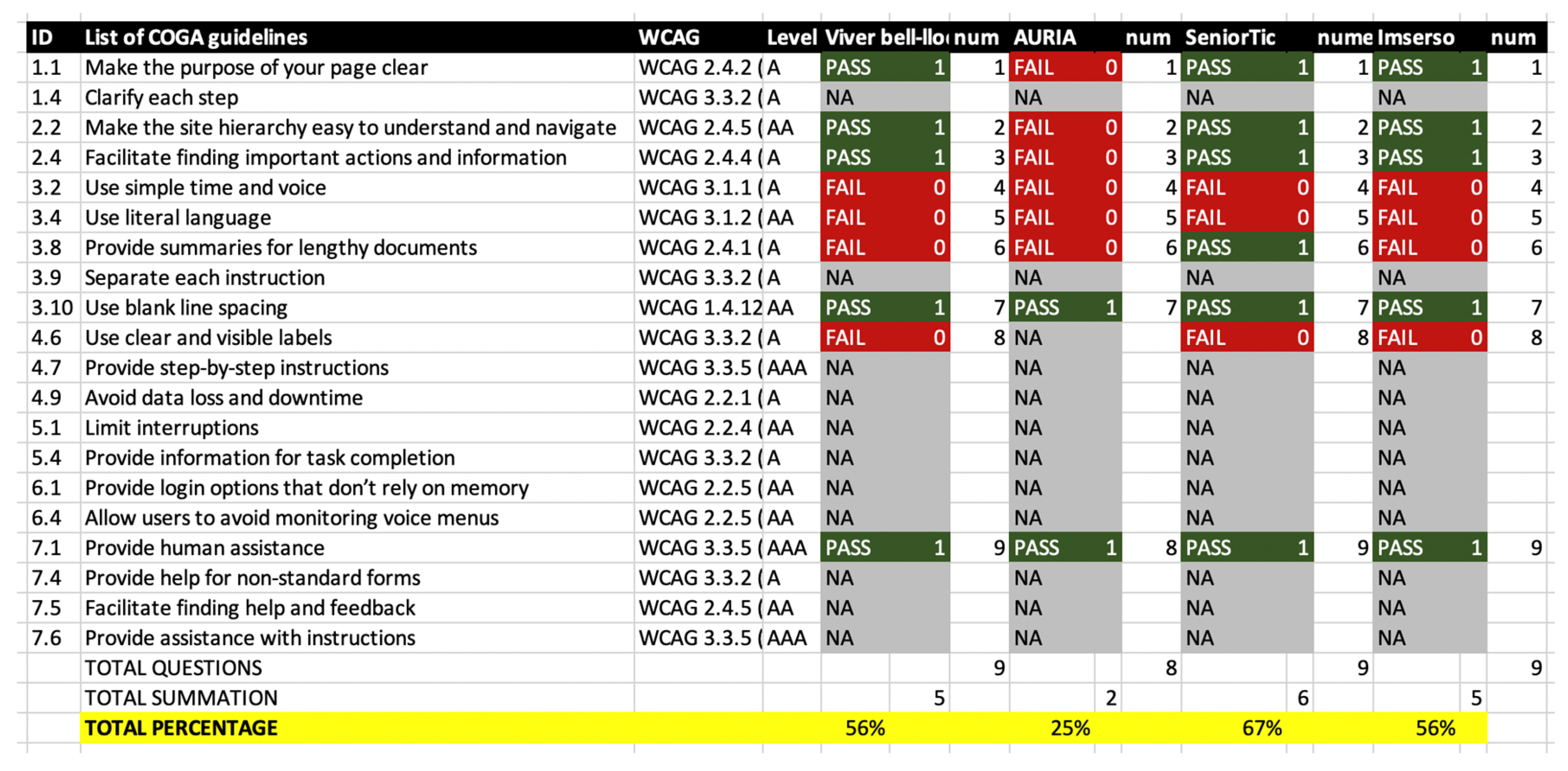

4.2.1. Selection of usability and accessibility guidelines

4.2.2 Implementation of the assessment

4.2.3 Results

| Heuristics | COGA guidelines | TOTAL | |

| Viver bell-lloc | 75% | 56% | 65,28% |

| AURIA Foundation | 57% | 25% | 41,07% |

| SeniorTic | 75% | 67% | 70,83% |

| Imserso | 75% | 56% | 65,28% |

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A

| WCAG Success Criterion | Level | Versions | Disabilities |

| 1.1.1: Non-text Content | A | Blind, Deaf, Deaf-blind | |

| 1.2.1: Audio-only and Video-only (Prerecorded) | A | Blind, Deaf, Deaf-blind, Cognitive | |

| 1.2.2: Captions (Prerecorded) | A | Deaf | |

| 1.2.3: Audio Description or Media Alternative (Prerecorded) | A | Blind | |

| 1.2.4: Captions (Live) | AA | Deaf | |

| 1.2.5: Audio Description (Prerecorded) | AA | Blind, Low vision,Cognitive | |

| 1.2.6 Sign Language (Prerecorded) | AAA | Deaf | |

| 1.2.7 Extended Audio Description (Prerecorded) | AAA | Blind, Deaf, Deaf-blind, Cognitive | |

| 1.2.8 Media Alternative (Prerecorded) | AAA | Deaf, Deaf-blind, Low Vision | |

| 1.2.9 Audio-only (Live) | AAA | Deaf | |

| 1.3.1: Info and Relationships | A | Blind, Deaf-blind | |

| 1.3.2: Meaningful Sequence | A | Blind | |

| 1.3.3: Sensory Characteristics | A | Blind, Low Vision | |

| 1.3.4: Orientation | AA | New in 2.1 | Low vision,Motor |

| 1.3.5: Identify Input Purpose | AA | New in 2.1 | Motor, Cognitive, Languaje and learning |

| 1.3.6 Identify Purpose | AAA | Cognitive, Languaje and learning | |

| 1.4.1: Use of Color | A | Low vision,color-blindness | |

| 1.4.2: Audio Control | A | Blind | |

| 1.4.3: Contrast (Minimum) | AA | Low vision,color-blindness | |

| 1.4.4: Resize text | AA | Low Vision | |

| 1.4.5: Images of Text | AA | Low vision,Cognitive | |

| 1.4.6 Contrast (Enhanced) | AAA | Low vision,color-blindness | |

| 1.4.7 Low or No Background Audio | AAA | Low Deaf | |

| 1.4.8 Visual Presentation | AAA | Low vision,Cognitive, Languaje and learning | |

| 1.4.9 Images of Text (No Exception) | AAA | Low vision,Cognitive, Languaje and learning | |

| 1.4.10: Reflow | AA | New in 2.1 | Low Vision |

| 1.4.11: Non-text Contrast | AA | New in 2.1 | Low Vision |

| 1.4.12: Text Spacing | AA | New in 2.1 | Low vision,Cognitive |

| 1.4.13: Content on Hover or Focus | AA | New in 2.1 | Low vision,Motor, Cognitive |

| 2.1.1: Keyboard | A | Blind, Low vision,hand tremors | |

| 2.1.2: No Keyboard Trap | A | Blind, Motor | |

| 2.1.3 Keyboard (No Exception) | AAA | Blind, low vision | |

| 2.1.4: Character Key Shortcuts | A | New in 2.1 | Motor, Languaje and learning |

| 2.2.1: Timing Adjustable | A | Blind, Deaf, Low vision,Motor, Cognitive, Languaje and learning, Reading disabilities | |

| 2.2.2: Pause, Stop, Hide | A | Deaf | |

| 2.2.3 No Timing | AAA | Blind, Deaf, Low vision,Motor, Cognitive, Languaje and learning | |

| 2.2.4 Interruptions | AAA | Low vision,atention deficit disorders | |

| 2.2.5 Re-authenticating | AAA | Deaf, Cognitive | |

| 2.2.6 Timeouts | AAA | Cognitive | |

| 2.3.1: Three Flashes or Below Threshold | A | Photosensitive epilepsy | |

| 2.3.2 Three Flashes | AAA | Photosensitive epilepsy | |

| 2.3.3 Animation from Interactions | AAA | Vestibular Disorder | |

| 2.4.1: Bypass Blocks | A | Low vision,Cognitive | |

| 2.4.2: Page Titled | A | visual impairments, severe mobility impairments, Cognitive, Reading disabilities, Short-term memory | |

| 2.4.3: Focus Order | A | visual impairments, Motor, Reading disabilities | |

| 2.4.4: Link Purpose (In Context) | A | visual disabilities, Motor, Cognitive | |

| 2.4.5: Multiple Ways | AA | visual impairments, Cognitive | |

| 2.4.6: Headings and Labels | AA | visual impairments, Reading disabilities, Short-term memory | |

| 2.4.7: Focus Visible | AA | Low vision,Motor, Attention limitations | |

| 2.4.8 Location | AAA | Attention limitations | |

| 2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only) | AAA | Blind, Languaje and learning | |

| 2.4.10 Section Headings | AAA | Attention limitations, Short-term memory | |

| 2.4.11 Focus Not Obscured (Minimum) | AA | New in 2.2 | Low vision,Motor, Cognitive |

| 2.4.12 Focus Not Obscured (Enhanced) | AAA | New in 2.2 | Low vision,Motor, Cognitive |

| 2.4.13 Focus Appearance | AAA | New in 2.2 | Motor, Cognitive |

| 2.5.1: Pointer Gestures | A | New in 2.1 | Motor |

| 2.5.2: Pointer Cancellation | A | New in 2.1 | Blind, Low vision,Motor, Cognitive |

| 2.5.3: Label in Name | A | New in 2.1 | Blind, Speech-input users |

| 2.5.4: Motion Actuation | A | New in 2.1 | Motor |

| 2.5.5 Target Size (Enhanced) | AAA | Low vision,Motor | |

| 2.5.6 Concurrent Input Mechanisms | AAA | Motor, Speech-input users | |

| 2.5.7 Dragging Movements | AA | New in 2.2 | Motor |

| 2.5.8 Target Size (Minimum) | AA | New in 2.2 | Motor |

| 3.1.1: Language of Page | A | Blind, Cognitive, Languaje and learning, Reading disabilities | |

| 3.1.2: Language of Parts | AA | Blind, Cognitive, Languaje and learning, Reading disabilities | |

| 3.1.3 Unusual Words | AAA | Low vision,Languaje and learning | |

| 3.1.4 Abbreviations | AAA | Low vision,Languaje and learning | |

| 3.1.5 Reading Level | AAA | Cognitive, Languaje and learning, Reading disabilities | |

| 3.1.6 Pronunciation | AAA | Cognitive, Languaje and learning, Reading disabilities | |

| 3.2.1: On Focus | A | visual, Motor, Cognitive | |

| 3.2.2: On Input | A | Blind, Low vision,intellectual disabilities, Reading disabilities | |

| 3.2.3: Consistent Navigation | AA | cognitive limitations,ow vision, intellectual disabilities, blind. | |

| 3.2.4: Consistent Identification | AA | Reading disabilities | |

| 3.2.5 Change on Request | AAA | Blind, Low vision,Cognitive, Reading disabilities, dificulty interpreting visual | |

| 3.2.6 Consistent Help | A | New in 2.2 | Cognitive, Languaje and learning |

| 3.3.1: Error Identification | A | Blind, color blind, Cognitive, Languaje and learning | |

| 3.3.2: Labels or Instructions | A | Cognitive, Languaje and learning | |

| 3.3.3: Error Suggestion | AA | Blind, impairment vision, Motor, Learning | |

| 3.3.4: Error Prevention (Legal, Financial, Data) | AA | All disabilities | |

| 3.3.5 Help | AAA | Intellectual disabilities, writing disabilities, Reading disabilities | |

| 3.3.6 Error Prevention (All) | AAA | All disabilities | |

| 3.3.7 Redundant Entry | A | New in 2.2 | Cognitive |

| 3.3.8 Accessible Authentication (Minimum) - NEW in 2.2 | AA | New in 2.2 | Cognitive |

| 3.3.9 Accessible Authentication (Enhanced) | AAA | New in 2.2 | Intellectual disabilities, writing disabilities, Reading disabilities |

| 4.1.1: Parsing | A | All disabilities | |

| 4.1.2: Name, Role, Value | A | Blind | |

| 4.1.3: Status Messages | AA | New in 2.1 | Blind |

| WCAG Success Criterion related with disabilities (cognitive) | Level | Versions |

|---|---|---|

| 1.2.1: Audio-only and Video-only (Prerecorded) | A | |

| 1.2.5: Audio Description (Prerecorded) | AA | |

| 1.2.7 Extended Audio Description (Prerecorded) | AAA | |

| 1.3.5: Identify Input Purpose | AA | New in 2.1 |

| 1.3.6 Identify Purpose | AAA | |

| 1.4.5: Images of Text | AA | |

| 1.4.8 Visual Presentation | AAA | |

| 1.4.9 Images of Text (No Exception) | AAA | |

| 1.4.12: Text Spacing | AA | New in 2.1 |

| 1.4.13: Content on Hover or Focus | AA | New in 2.1 |

| 2.2.1: Timing Adjustable | A | |

| 2.2.3 No Timing | AAA | |

| 2.2.4 Interruptions | AAA | |

| 2.2.5 Re-authenticating | AAA | |

| 2.2.6 Timeouts | AAA | |

| 2.4.1: Bypass Blocks | A | |

| 2.4.2: Page Titled | A | |

| 2.4.4: Link Purpose (In Context) | A | |

| 2.4.5: Multiple Ways | AA | |

| 2.4.11 Focus Not Obscured (Minimum) | AA | New in 2.2 |

| 2.4.12 Focus Not Obscured (Enhanced) | AAA | New in 2.2 |

| 2.4.13 Focus Appearance | AAA | New in 2.2 |

| 2.5.2: Pointer Cancellation | A | New in 2.1 |

| 3.1.1: Language of Page | A | |

| 3.1.2: Language of Parts | AA | |

| 3.2.1: On Focus | A | |

| 3.2.2: On Input | A | |

| 3.2.5 Change on Request | AAA | |

| 3.2.6 Consistent Help | A | New in 2.2 |

| 3.3.1: Error Identification | A | |

| 3.3.2: Labels or Instructions | A | |

| 3.3.5 Help | AAA | |

| 3.3.7 Redundant Entry | A | New in 2.2 |

| 3.3.8 Accessible Authentication (Minimum) | AA | New in 2.2 |

| ID | Description | Related WCAG 2.2 Criterion | Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Does the application visibly include the title of the page, section, or site? | WCAG 2.4.2 (Page Titles) | A |

| 1.4 | Are the links clearly defined? | WCAG 2.4.4 (Link Purpose) | A |

| 3.1 | Is there a link to return to the initial state or homepage? | WCAG 2.4.5 (Multiple Ways) | AA |

| 4.1 | Do the link labels have the same names as their destinations? | WCAG 2.4.4 (Link Purpose) | A |

| 5.1 | Is it easy to use the system for the first time? | WCAG 3.2.1 (On Focus) | A |

| 5.1 | Is it easy to use the system for the first time? | WCAG 3.2.2 (On Input) | A |

| 5.2 | Is it easy to find information that has been previously searched for? | WCAG 2.4.5 (Multiple Ways) | AA |

| 5.3 | Can the system be used at all times without having to remember previous screens? | WCAG 2.4.4 (Link Purpose) | A |

| 6.2 | If they exist, is it clear how to use them? | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) | A |

| 6.3 | When performing any action for the first time, is it clear how to perform it permanently? | WCAG 3.2.1 (On Focus) | A |

| 6.6 | Is the user always kept occupied? (Without unnecessary waiting times) | WCAG 3.2.2 (On Input) | A |

| 6.6 | Is the user always kept occupied? (Without unnecessary waiting times) | WCAG 3.3.1 (Error Identification) | A |

| 7.2 | Are the errors made displayed in real-time? | WCAG 3.3.1 (Error Identification) | A |

| 8.2 | Is it clear what needs to be entered in each form field? | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) | AAA |

| 8.3 | Does the search engine tolerate typographical and spelling errors? | WCAG 3.3.5 (Help Text) | AAA |

| 9.1 | Has a design been used without redundancy of information? | WCAG 1.4.8 (Visual Presentation) | AA |

| 9.2 | Is the textual information concise and precise? | WCAG 1.4.5 (Images of Text) | AA |

| 9.4 | Is the text structure correct, with short and easy-to-interpret sentences? | WCAG 1.4.5 (Images of Text) | AA |

| 10.2 | If it exists, is it visible and easily accessible? | WCAG 2.4.5 (Multiple Ways) | A |

| 10.3 | Is the help oriented towards problem-solving? | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) | AA |

| 10.4 | Is there a frequently asked questions section? | WCAG 2.4.5 (Multiple Ways) | A |

| 11.1 | Can users continue from a previous state they left in at another time or from another device? | WCAG 2.5.2 (On Focus) | A |

| 11.2 | Is the "autosave" utility implemented? | WCAG 3.2.2 (On Input) | A |

| 11.3 | Does it respond well to external failures? (Power outages, internet disruptions, etc.) | WCAG 3.2.2 (On Input) | AA |

| 12.1 | Are the text fonts of an adequate size? | WCAG 1.4.12 (Text Spacing) | A |

| 15.2 | Is the remaining time or some animation shown for heavy tasks being executed? | WCAG 2.2.1 (Timing Adjustable) | A |

| Recommendation | Description | WCAG 2.2 Guideline |

| 1.1. Make the purpose of your page clear | Clarity in the purpose of the page and its content. | WCAG 2.4.2 (Page Title) |

| 1.4. Clarify each step | Provide clear explanations about the steps involved in tasks. | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) |

| 2.2. Make the site hierarchy easy to understand | Ensure clarity in the site's structure for effective navigation. | WCAG 2.4.5 (Multiple Ways) |

| 2.4. Facilitate finding important actions/info | Place key actions in prominent locations. | WCAG 2.4.4 (Link Purpose) |

| 3.2. Use simple time and voice | Avoid complex grammatical structures. | WCAG 3.1.1 (Page Language) |

| 3.4. Use literal language | Avoid figurative or confusing language. | WCAG 3.1.2 (Language of Parts) |

| 3.8. Provide summaries for lengthy documents | Include clear summaries for long or complex documents. | WCAG 2.4.1 (Bypass Blocks) |

| 3.9. Separate each instruction | Keep instructions in separate steps. | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) |

| 3.10. Use blank line spacing | Prevent content from blending with other visual elements. | WCAG 1.4.12 (Text Spacing) |

| 4.6. Use clear and visible labels | Ensure well-visible and understandable labels for each field. | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) |

| 4.7. Provide step-by-step instructions | Offer clear and detailed instructions on how to perform a task. | WCAG 3.3.5 (Help Text) |

| 4.9. Avoid data loss and downtime | Prevent data loss when time is limited or connections fail. | WCAG 2.2.1 (Timing Adjustable) |

| 5.1. Limit interruptions | Minimize interruptions during task completion. | WCAG 2.2.4 (Interruptions Avoidable) |

| 5.4. Provide information for task completion | Include all necessary information to complete a task without overloading the user. | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) |

| 6.1. Offer login options that don’t rely on memory | Provide login options that do not require remembering a lot of information. | WCAG 2.2.5 (Authentication Help) |

| 6.4. Allow users to avoid monitoring voice menus | Do not require users to remember long lists of options. | WCAG 2.2.5 (Authentication Help) |

| 7.1. Provide human assistance | Make human assistance available when needed. | WCAG 3.3.5 (Help Text) |

| 7.4. Provide help for non-standard forms | Include clear instructions on how to use non-traditional forms. | WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions) |

| 7.5. Facilitate finding help and feedback | Include visible links to access help. | WCAG 2.4.5 (Multiple Ways) |

| 7.6. Provide assistance with instructions | Offer clear assistance for completing tasks or following instructions. | WCAG 3.3.5 (Help Text) |

References

- Digital 2024: Global Overview Report (2024). Disponible en: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-global-overview-report.

- World Report on Disability 2011 https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability.

- World Health Organization: Summary World Report on Disability (2011). Available in https://cutt.ly/ZrDBPje.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (2022) https://www.un.org/es/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

- Novak, ME y Paciello, MG (2002). La conquista de la accesibilidad de X-Windows: desarrollo para personas con discapacidades. The Paciello Group. [en línea] Disponible en: http://www.paciellogroup.com/resources/whitepapers/WPX-Windows.htm.

- Hudson, R., Weakley, R. y Firminger, P. (2005). Una frontera de accesibilidad: discapacidades cognitivas y dificultades de aprendizaje. Webusability – Servicios de accesibilidad y usabilidad. http://www.usability.com.au/resources/cognitive.php.

- ISO/CD 9241-11. Ergonomics of human-system interaction–Part 11: Guidance on usability (1998). http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=63500.

- Introduction to web accessibility (2018). Available in https://www.w3.org/standards/webdesign/accessibility.

- Evaluating Web Accessibility Overview (2020). Available in https://www.w3.org/WAI/test-evaluate/.

- Quintal, C., Macías, J.A. Measuring and improving the quality of development processes based on usability and accessibility. Univ Access Inf Soc 20, 203–221 (2021). [CrossRef]

- González, M. P., Pascual, A., & Lorés, J. (2001). Evaluación heurística. 2001). Introducción a la Interacción Persona-Ordenador. AIPO: Asociación Interacción Persona-Ordenador.

- WCAG 2 Overview (2024). https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/.

- Cockton, G. (2014, January 1). Usability Evaluation. Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/usability-evaluation.

- La Interacción Persona Ordenador (2001) Asociación en Interacción Persona Ordenador. ISBN: 84-607-2255-4. Available in https://aipo.es/educacion/material-editado-por-aipo/?id_rec=2.

- Polson P Rieman J Wharton C Olson J Kitajima M . Usability inspection methods: rationale and examples. The 8th Human Interface Symposium (HIS92). Kawasaki, Japan. 1992;1992:377–384.

- Jeffries R Miller JR Wharton C Uyeda K . User interface evaluation in the real world: a comparison of four techniques. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM. 1991;1991:119–124.

- Nielsen J . Finding usability problems through heuristic evaluation. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM. 1992;1992:373–380.

- C. Jimenez, P. Lozada and P. Rosas, "Usability heuristics: A systematic review," 2016 IEEE 11th Colombian Computing Conference (CCC), Popayan, Colombia, 2016, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.: 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design [Online Resource]. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/.

- Durães Dourado, Marcos Antonio & Canedo, E.D.. (2018). Usability Heuristics for Mobile Applications - A Systematic Review. 483-494. [CrossRef]

- Kuhail, M. A., Farooq, S., & Almutairi, S. (2023). Recent Developments in Chatbot Usability and Design Methodologies. In M. Kuhail, B. Abu Shawar, & R. Hammad (Eds.), Trends, Applications, and Challenges of Chatbot Technology (pp. 1-23). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, Estela & Silveira, Aleph & Martins, Ronei. (2019). Heuristic Evaluation on Usability of Educational Games: A Systematic Review. Informatics in Education. 18. 427-442. [CrossRef]

- Omar K, Fakhouri H, Zraqou J, Marx Gómez J. Usability Heuristics for Metaverse. Computers. 2024; 13(9):222. [CrossRef]

- González, Marta & Masip, Llúcia & Granollers, Toni & Oliva, Marta. (2008) Análisis Cuantitativo en un Experimento de Evaluación Heurística. IX Congreso Internacional Interacción,.

- Bonastre, L., Granollers, T.: A set of heuristics for user experience evaluation in Ecommerce websites. In: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions, ACHI 2014, pp. 27–34 (2014). ISBN 978-1-61208-325-.

- B. Tognazzini, “First Principles, HCI Design, Human Computer Interaction (HCI), Principles of HCI Design, Usability Testing“. [Online]. Available from: http://www.asktog.com/basics/firstPrinciples.html, 2014.

- Pascual-Almenara, Afra & Saltiveri, Toni & Navarro, Juan & Albets, Marta. (2024). Enhancing Usability Assessment with a Novel Heuristics-Based Approach Validated in an Actual Business Setting. Journal on Interactive Systems. 15. 615-631. [CrossRef]

- Onay Durdu, P. & Soydemir, Ö. N. (2022). A Systematic Review of Web Accessibility Metrics. In Y. Akgül (Ed.), App and Website Accessibility Developments and Compliance Strategies (pp. 77-108). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Firas Masri, Sergio Luján-Mora. A Combined Agile Methodology for the Evaluation of Web Accessibility. IADIS International Conference Interfaces and Human Computer Interaction 2011 (IHCI 2011), p. 423-428, Rome (Italy), July 24-26 2011. ISBN: 978-972-8939-52-6.

- Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools List (2024). https://www.w3.org/WAI/test-evaluate/tools/list/.

- Brajnik, Giorgio & Vigo, Markel. (2019). Automatic Web Accessibility Metrics: Where We Were and Where We Went. 10.1007/978-1-4471-7440-0_27.

- André P. Freire, Renata P. M. Fortes, Marcelo A. S. Turine, and Debora M. B. Paiva. 2008. An evaluation of web accessibility metrics based on their attributes. In Proceedings of the 26th annual ACM international conference on Design of communication (SIGDOC '08). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.2 (WCAG). World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) (2023). http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG22/.

- Making Content Usable for People with Cognitive and Learning Disabilities. (2021) https://www.w3.org/TR/coga-usable.

- Ana Luiza Dias, Renata Pontin de Mattos Fortes, and Paulo Cesar Masiero. Heua: A heuristic evaluation with usability and accessibility requirements to assess web systems. In Proceedings of the 11th Web for All Conference, pages 18:1–18:4, New York, NY, USA, 2014. ACM.

- Rodrigues, Sandra & Fortes, Renata. (2020). A Checklist for the Evaluation of Web Accessibility and Usability for Brazilian Older Adults. Journal of Web Engineering (JWE). 19. 63-108. [CrossRef]

- Tateo, L. (2021). Web accessibility and usability: limits and perspectives. Workshop on Technology Enhanced Learning Environments for Blended Education.

- Moreno, Lourdes & Martinez, Paloma & Ruíz-Mezcua, Belén. (2009). A Bridge to Web Accessibility from the Usability Heuristics. 290-300. [CrossRef]

- Alba Bisante, Venkata Srikanth Varma Datla, Emanuele Panizzi, Gabriella Trasciatti, and Stefano Zeppieri. 2024. Enhancing Interface Design with AI: An Exploratory Study on a ChatGPT-4-Based Tool for Cognitive Walkthrough Inspired Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces (AVI '24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 41, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- P. Acosta-Vargas, G. Acosta-Vargas, B. Salvador-Acosta and J. Jadán-Guerrero, "Addressing Web Accessibility Challenges with Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools for Inclusive Education," 2024 Tenth International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG), Lucerne, Switzerland, 2024, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Eric York. 2023. Evaluating ChatGPT: Generative AI in UX Design and Web Development Pedagogy. In Proceedings of the 41st ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (SIGDOC '23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Interactions. Volume XXXI.1 January - February 2024 https://interactions.acm.org/archive/toc/january-february-2024/https://interactions.acm.org/archive/toc/january-february-2024/.

- Pascual-Almenara, A. and Granollers-Saltiveri, T. (2021).Combining two inspection methods: Usability heuristicevaluationandwcagguidelinestoassesse-commerceweb-sites. In Ruiz, P. H., Agredo-Delgado, V., and Kawamoto,A. L. S., editors,Human-Computer Interaction, pages 1–16, Cham. Springer International Publishing.

- Granollers, T. Albets, Marta (2021). Heuristic Evaluations new proposal. https://mpiua.invid.udl.cat/evaluacion-heuristica-una-nueva-propuesta/.

- WCAG 2.2 Understanding Docs (2023). https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG22/Understanding/.

- Casare, Andréia & Guimarães da Silva, Celmar & Martins, Paulo & Moraes, Regina. (2019). Mapping WCAG Guidelines to Nielsen's Heuristics. [CrossRef]

- García Muñoz, O. Pautas de accesibilidad cognitiva web (2020). García Muñoz, O (Plena Inclusión Madrid). https://plenainclusionmadrid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Guia-Pautas-Accesibilidad-2020-final.pdf.

- M. Campoverde-Molina, S. Luján-Mora and L. V. García, "Empirical Studies on Web Accessibility of Educational Websites: A Systematic Literature Review," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 91676-91700, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J., & Tahir, M. (2001). Homepage usability: 50 websites deconstructed. New Riders Press.

- Brooke J. (1996). SUS: A ‘quick and dirty’ usability scale. In Jordan P.W., Thomas B., Weerdmeester A., McClelland I.I. (Eds.) Usability evaluation in industry, london (pp 189-194). Taylor & Francis.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).