Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

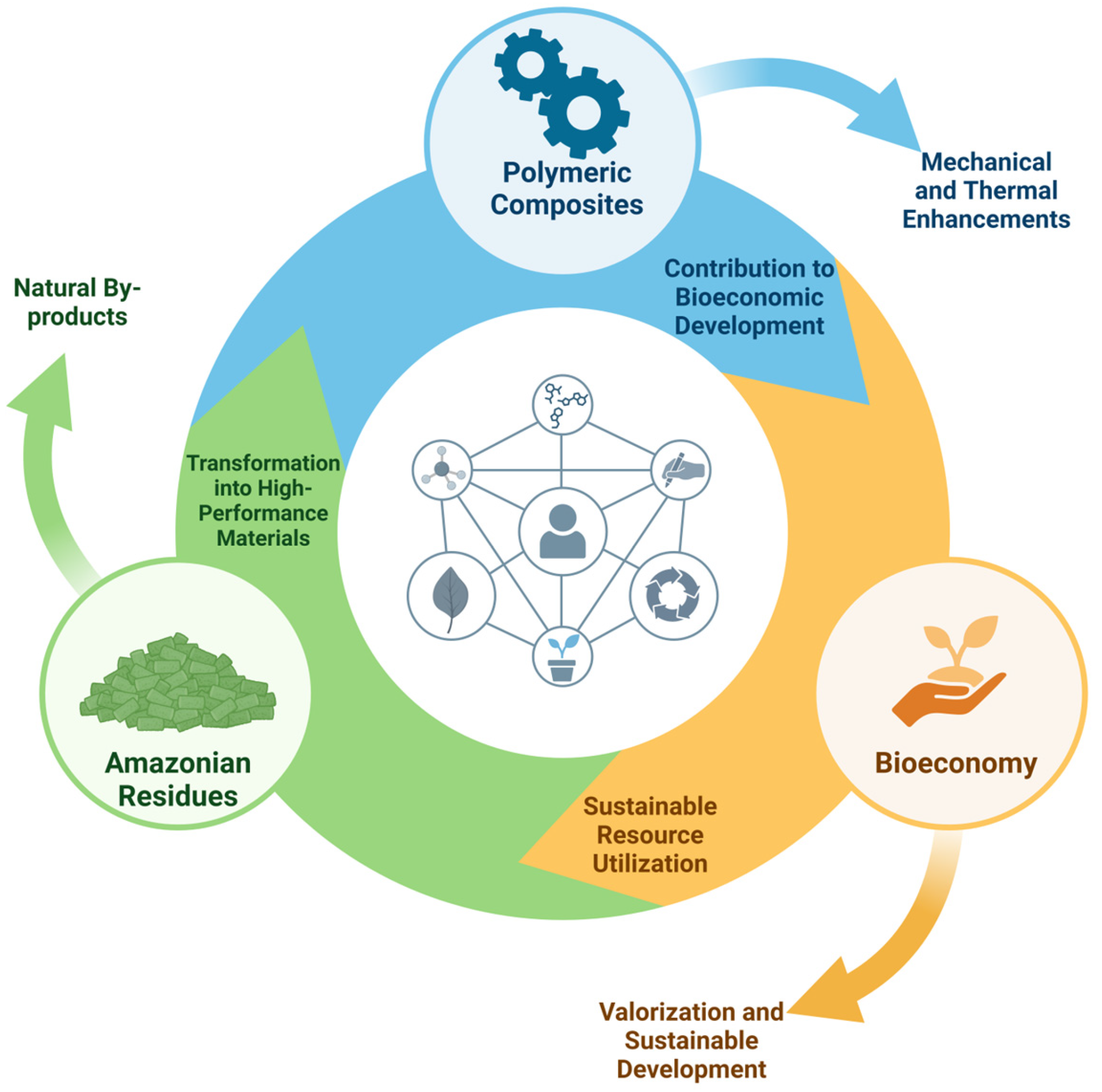

1. Introduction

2. The Amazonian Timber and Agro-Extrativism Bioindustries

2.1. General Description of the Bioindustry in the Amazon

2.2. Production and Economic Impact

2.3. Chemical Composition Impact on Polymeric Composite Properties

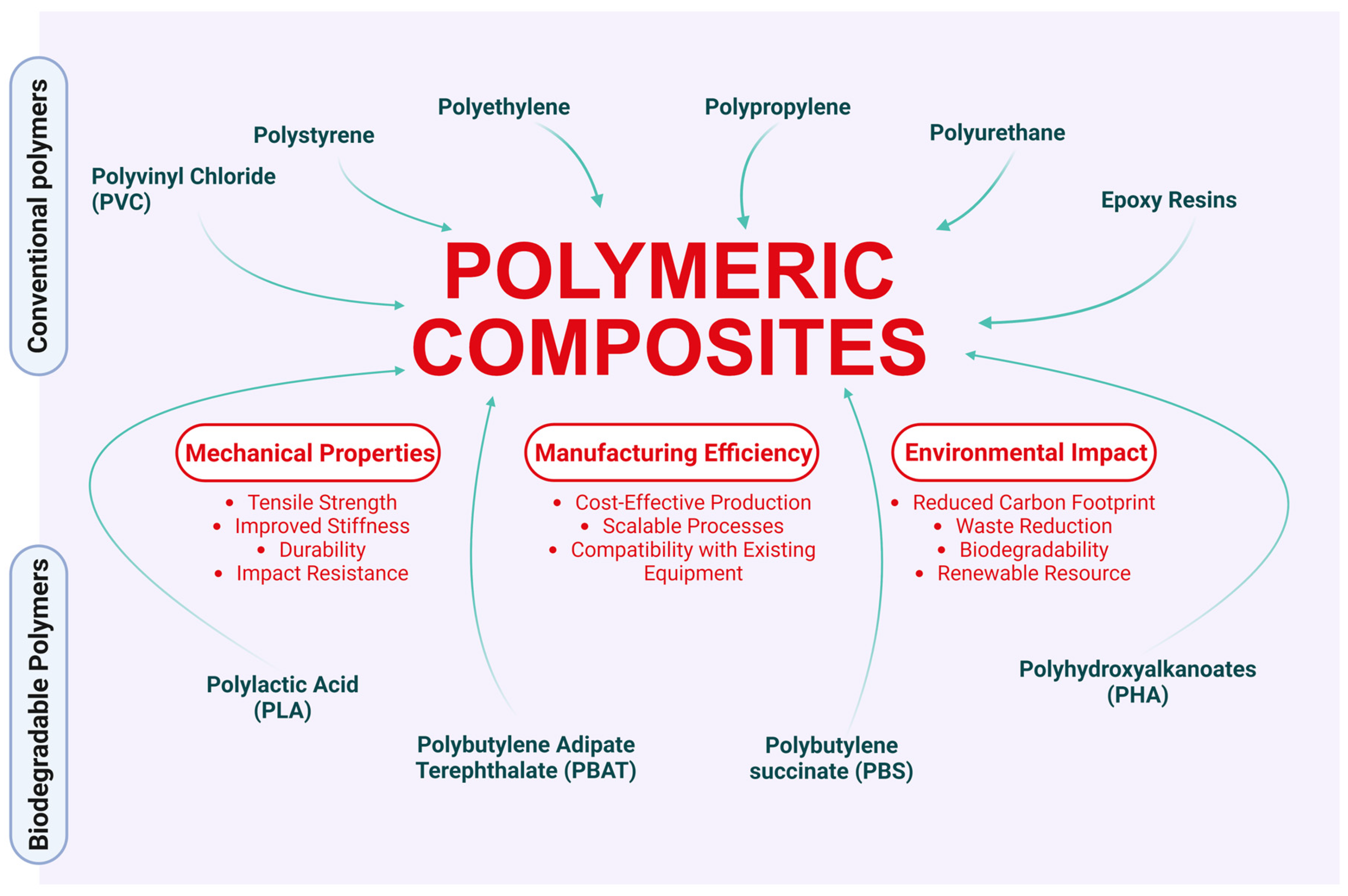

3. Types of Polymer Matrices Applicable in Composites with Residues

4. Polymeric Composites with Amazonian Timber Industry Residues

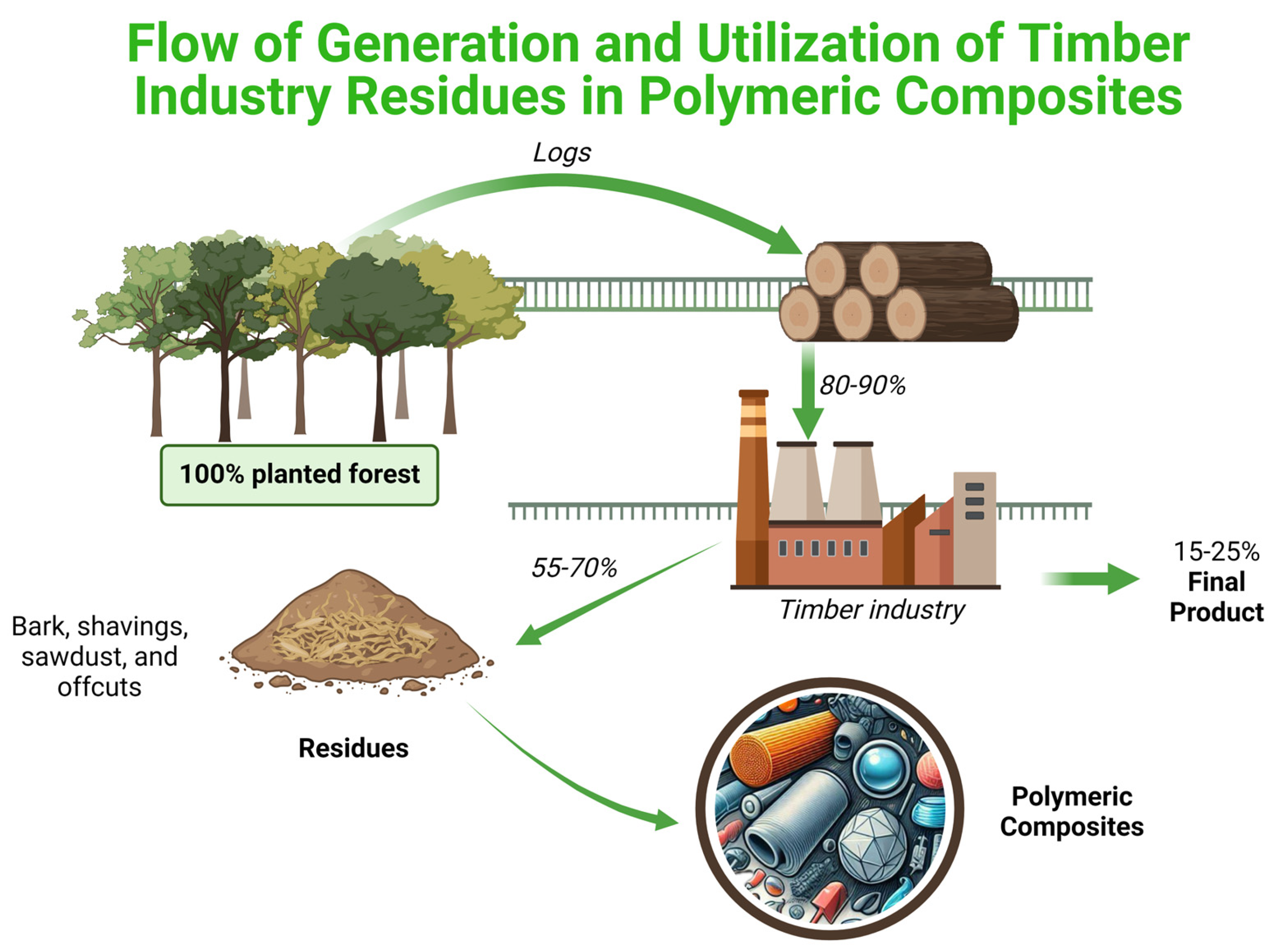

4.1. Types and Sources of Timber Residues

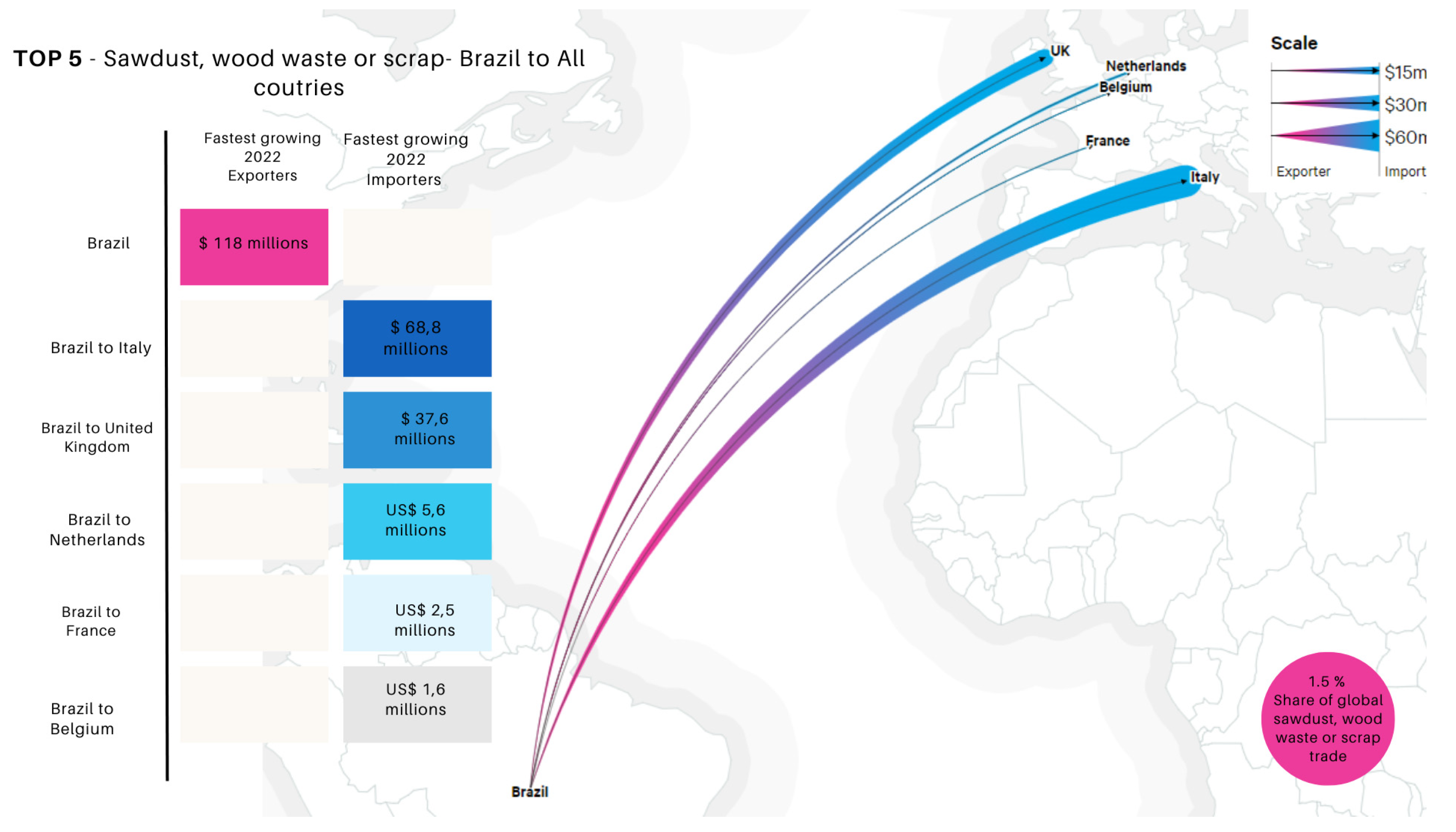

4.2. Residue Availability and Environmental Impact in the Timber Industry

4.3. Applications of Residues from the Amazon Timber Industry in Polymeric Composites

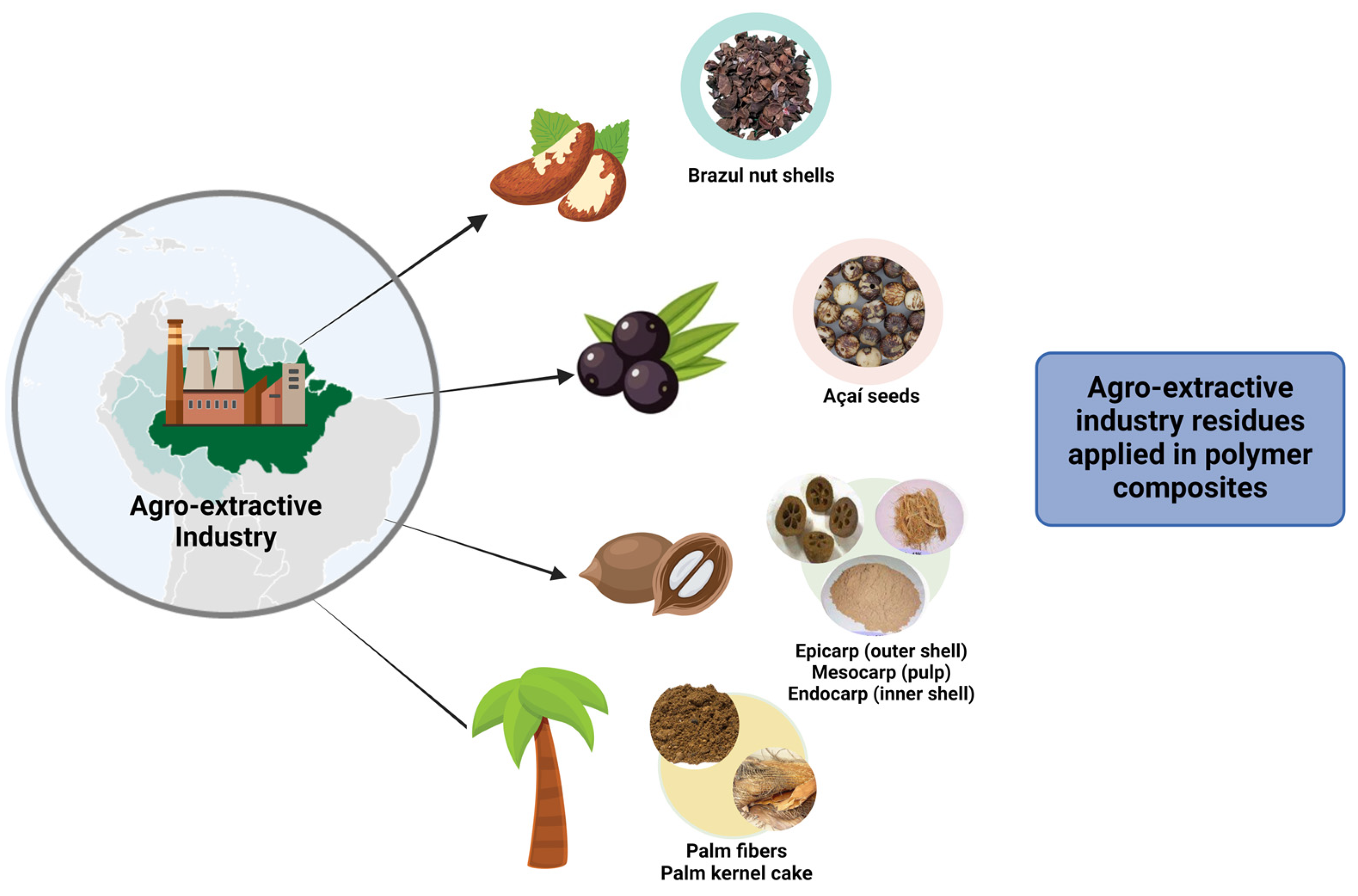

5. Polymeric Composites with Agro-Extrativism Industry Residues from the Amazon

5.1. Types and Sources of Agro-Extrativism Residues

5.2. Residue Availability and Environmental Impact in the Agro-Extrativism Industry

5.3. Applications of Agro-Extrativism Industry Residues in Polymeric Composites

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NEPSTAD:, D.; AZEVEDO-RAMOS, C.; LIMA, E.; McGRATH, D.; PEREIRA, C.; MERRY, F. Managing the Amazon Timber Industry. Conservation Biology 2004, 18, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, K. Environmental cost of deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon Rainforest: Controlling biocapacity deficit and renewable wastes for conserving forest resources. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 504, 119854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, F.P.M.; Oliveira, M.A.d.; Rocha, L.L.; Cardoso, A.; Veroneze, G.d.M. The circular economy in the perspective of sustainable joinery: a case study in the Amazon / A economia circular na perspectiva da carpintaria sustentável: um estudo de caso na Amazônia. Brazilian Journal of Development 2022, 8, 45482–45504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väisänen, T.; Haapala, A.; Lappalainen, R.; Tomppo, L. Utilization of agricultural and forest industry waste and residues in natural fiber-polymer composites: A review. Waste Management 2016, 54, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, O.; Babu, K.; Shanmugam, V.; Sykam, K.; Tebyetekerwa, M.; Neisiany, R.E.; Försth, M.; Sas, G.; Gonzalez-Libreros, J.; Capezza, A.J.; et al. Natural and industrial wastes for sustainable and renewable polymer composites. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 158, 112054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Mensah, R.A.; Försth, M.; Sas, G.; Ágoston Restás. ; Addy, C.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Neisiany, R.E.; Singha, S.; et al. Circular economy in biocomposite development: State-of-the-art, challenges and emerging trends. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021, 5, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.; Soares-Filho, B.; Souza, F.; Rajão, R.; Merry, F.; Carvalho Ribeiro, S. Mapping the socio-ecology of Non Timber Forest Products (NTFP) extraction in the Brazilian Amazon: The case of açaí (Euterpe precatoria Mart) in Acre. Landscape and Urban Planning 2019, 188, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.B.N.; Jerozolimski, A.; de Robert, P.; Magnusson, W.E. Brazil nut stock and harvesting at different spatial scales in southeastern Amazonia. Forest Ecology and Management 2014, 319, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.W.C.; Pinto, T.I.; Moreira, L.d.S.; da Ponte, M.J.M.; Lobato, T.d.C.; de Sousa, J.T.R.; Moutinho, V.H.P. The Legal Roundwood Market in the Amazon and Its Impact on Deforestation in the Region between 2009–2015. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, K.G.; Arizaga, G.G.; Wypych, F. Biodegradable composites based on lignocellulosic fibers—An overview. Progress in Polymer Science 2009, 34, 982–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego-Aguilar, K.; Sánchez-Safont, E.; Rodríguez, A.; Marín, A.; Candal, M.V.; Cabedo, L.; Gamez-Perez, J. Valorization of Agricultural Waste Lignocellulosic Fibers for Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-Valerate)-Based Composites in Short Shelf-Life Applications. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platnieks, O.; Barkane, A.; Ijudina, N.; Gaidukova, G.; Thakur, V.K.; Gaidukovs, S. Sustainable tetra pak recycled cellulose / Poly(Butylene succinate) based woody-like composites for a circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 270, 122321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.E.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C.; Ehman, N.V.; Tarrés, Q.; Mutjé, P. Nanofibrillated cellulose (CNF) from eucalyptus sawdust as a dry strength agent of unrefined eucalyptus handsheets. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016, 139, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinoj, S.; Visvanathan, R.; Panigrahi, S.; Kochubabu, M. Oil palm fiber (OPF) and its composites: A review. Industrial Crops and Products 2011, 33, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávaro, S.L.; Lopes, M.S.; Vieira de Carvalho Neto, A.G.; Rogério de Santana, R.; Radovanovic, E. Chemical, morphological, and mechanical analysis of rice husk/post-consumer polyethylene composites. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2010, 41, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.H.; Andenan, N.; Rahman, W.A.W.A.; Rusman, R.; Majid, R.A. Evaluation of rice straw as natural filler for injection molded high density polyethylene bio-composite materials. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2017, 56, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Singh, J.; Sharma, S.; Lam, T.D.; Nguyen, D.N. Fabrication and characterization of coir/carbon-fiber reinforced epoxy based hybrid composite for helmet shells and sports-good applications: influence of fiber surface modifications on the mechanical, thermal and morphological properties. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 15593–15603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.N.; Candido, V.S.; Braga, F.O.; Bolzan, L.T.; Weber, R.P.; Drelich, J.W. Sugarcane bagasse waste in composites for multilayered armor. European Polymer Journal 2016, 78, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, S.H.; Fan, M. An aggregated understanding of physicochemical properties and surface functionalities of wheat straw node and internode. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 95, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciforti, M.C.; Marinelli, A.L.; Kobayashi, M.; Ambrosio, J.D.; Monteiro, M.R.; Nobre, A.D. Wood Polymer Composites Technology Supporting the Recovery and Protection of Tropical Forests: The Amazonian Phoenix Project. Sustainability 2009, 1, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Nascimento, C.C.d.; Araujo, R.D.d. Ecological panels as an alternative for waste from mechanical processing of Amazonian species. International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 2020, 8, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoppul, S.D.; Finegan, J.; Gibson, R.F. Mechanics of mechanically fastened joints in polymer–matrix composite structures—A review. Composites Science and Technology 2009, 69, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z.M.; Yuan, J.K.; Zha, J.W.; Zhou, T.; Li, S.T.; Hu, G.H. Fundamentals, processes and applications of high-permittivity polymer–matrix composites. Progress in Materials Science 2012, 57, 660–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Advanced Materials by Design; Number OTA-E-351 in OTA Reports, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rajak, D.K.; Pagar, D.D.; Kumar, R.; Pruncu, C.I. Recent progress of reinforcement materials: a comprehensive overview of composite materials. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2019, 8, 6354–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Fu, Q.; Yan, L.; Kasal, B. Characterization of interfacial properties between fibre and polymer matrix in composite materials—A critical review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 13, 1441–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Haque, S.; Athikesavan, M.; et al. A review of environmental friendly green composites: production methods, current progresses, and challenges. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 16905–16929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taurino, R.; Bondioli, F.; Messori, M. Use of different kinds of waste in the construction of new polymer composites: review. Materials Today Sustainability 2023, 21, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Pieri, F.A. Tropical fruits: from cultivation to consumption and health benefits, fruits from the Amazon; Nova Publishers: New York, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, N.A. Óleos essenciais e desenvolvimento sustentável na Amazônia: uma aplicação da matriz de importância e desempenho. Reflexões Econômicas 2016, 2, 136–158. [Google Scholar]

- da, S. Santos, A. Óleos essenciais: uma abordagem econômica e industrial; Interciências: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Galúcio, A.V.; Prudente, A.L. Museu Goeldi: 150 anos de ciências na Amazônia; Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi: Belém, Brasil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mafra, R.Z.; Medeiros, R.L. Estudos da Bioindústria Amazonense: sustentabilidade, mercado e tecnologia; Edua: Manaus, Brasil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, J.D.; Medeiros, R.L.; Kuwahara, N.; Pauly, P.R.; Pierre Filho, M.d.Q.; Ferreira, M.A.C.; da Rocha, S.D.; da Costa, E.B.S. Selection of suppliers in a bioindustry in the Amazon using the saw, topsis and promethee II methods combined with fuzzy logic. Revista de Gestão e Secretariado 2023, 14, 20863–20890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Lasmar, D.; Mafra, R.; Kieling, A.; Albuquerque, A.; Oliveira, L.; Oliveira, S. Mapeamento das empresas e institutos de pesquisas que utilizam a biotecnologia Industrial no Estado do Amazonas. Peer Review 2023, 5, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, N.S. Boletim Científico ESMPU. Boletim Científico ESMPU 2010, 9, 199–235. [Google Scholar]

- GUAYASAMIN, J.M.; RIBAS, C.C.; CARNAVAL, A.C.; CARRILLO, J.D.; HOORN, C.; LOHMANN, L.G.; RIFF, D.; ULLOA ULLOA, C.; ALBERT, J.S. Evolution of Amazonian biodiversity: A review. Acta Amazonica 2024, 54, e54bc21360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, D.O. Desmatamento na Amazônia e influência nos produtos florestais não-madeireiros de uso econômico local. Tese de doutorado, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), São José dos Campos, SP, Brasil, 2023. Coordenação de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão (COEPE), Divisão de Biblioteca (DIBIB).

- Rocha, M.I.; Benkendorf, S.; Gern, R.M.M.; Riani, J.C.; Wisbeck, E. Desenvolvimento de biocompósitos fúngicos utilizando resíduos industriais. Matéria (Rio de Janeiro) 2020, 25, e–12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Matos, T.; de Sousa de Matos, T.; da Silva, A.C.R.; Monteiro, S.N.; Candido, V.S. Obtenção e Caracterização de Biocompósitos de Resíduo de Amido Mandioca Reforçados com Fibra de Tururi. In Proceedings of the 76º Congresso Anual da ABM—Internacional, São Paulo, Brasil; 2023; pp. 1750–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Ribeiro, K.C.; da Silva, C.A.; Freire, L.H.C. ECODESIGN VIA BIOCOMPÓSITOS POLIMÉRICOS: ENVELHECIMENTO, ANÁLISE ESTRUTURAL E RECICLAGEM. Mix Sustentável 2019, 5, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aragão, D.I.; Cardoso, P.H.M.; Lima, E.M.B.; da S., M. Thiré, R.M. Caracterização de biocompósitos de poli(3-hidroxibutirato-co-3-hidroxivalerato) (PHBV)/coproduto da agroindústria do suco de manga. Journal of Agricultural and Food Industrial Technology 2016, 5, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Meazza, K. Avaliação do beneficiamento de resíduos do pirarucu para a produção de biocompósitos a base de hidroxiapatita e fibra de colágeno. Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, Brasil, 2019. Mestrado em Ciência e Engenharia de Materiais. [CrossRef]

- Vinod, U.; Sanjay, M.; Siengchin, S.; Parameswaranpillai, J. A comprehensive review on the sustainable approach for recycling of textiles and apparel for production of biocomposites. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 248, 120978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, T.; Nazmi, A.R.; Shahri, B.; Emerson, N.; Huber, T. Mechanical and morphological properties of banana fiber reinforced polylactic acid biocomposites. Materials Today Communications 2022, 32, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.d.M.; Filgueiras, C.T.; Garcia, V.A.d.S.; Carvalho, R.A.d.; Velasco, J.I.; Fakhouri, F.M. Antimicrobial activity and GC-MS profile of copaiba oil for incorporation in Xanthosoma mafaffa Schott starch-based films. Polymers 2020, 12, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, T.R.d.; Matos, P.R.d.; Tambara Júnior, L.U.D.; Marvila, M.T.; Azevedo, A.R.G.d. Development of a biomimetic material for wound healing using poly(e-caprolactone) and andiroba seed oil. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 35, 106481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.P.d.O.; Castro, D.O.; Ruvolo-Filho, A.C.; Frollini, E. Preparation and properties of curaua fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2014, 132, 40386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Y. Biodegradable composites containing chicken feathers as matrix and jute fibers as reinforcement. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2014, 22, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, U.O.; Nascimento, L.F.C.; Garcia, J.M.; Bezerra, W.B.A.; Monteiro, S.N. Development and characterization of wood-plastic composite produced with high wood residue content. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 8, 6350–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Bringas, P.M.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of biocomposites based on Brazil nut shell waste and different starch sources. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 144869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, P.Y.; et al. Effects of electron beam irradiation on gelatin-based biocomposites reinforced with Brazil nut shell powder. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2011, 81, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.; Souza, L.; Silva, F. Autogenous self-healing capacity of curauá fiber-reinforced cement biocomposite. Procedia Engineering 2017, 200, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.; Ruvolo-Filho, A.; Frollini, E. Preparation and characterization of a biocomposite using hydroxylated polybutadiene, high-density bio-polyethylene and curauá fiber. Polymer Testing 2012, 31, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frollini, E.; Bartolucci, N.; Sisti, L.; Celli, A. Mechanical properties, water absorption, and morphology of a biocomposite using poly(butylene succinate) (PBS) and curauá fiber. Polymer Testing 2015, 43, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.; dos Santos, H.; Nunes, F.; Costa, J.; Lentini, M. Produção de madeira e diversidade de espécies arbóreas exploradas na Amazônia Brasileira: Situação atual e recomendações para o setor florestal. IMAFLORA, 2022. No. 08. Acesso em: Produzido pelo IMAFLORA em abril de 2022 no âmbito do projeto Forest Legality and Transparency in the Brazilian Amazon, apoiado pela Good Energies Foundation.

- Dionísio, L.F.S. Mid-term effects of selective logging on the growth, mortality, and recruitment of Manilkara huberi (Ducke) A. Chev. in an Amazonian rainforest. Scientia Forestalis 2020.

- Castro, T.d.C.; Carvalho, J.O.P.d. DINÂMICA DA POPULAÇÃO DE <b><i>Manilkara huberi</i></b> (DUCKE) A. CHEV. DURANTE 26 ANOS APÓS A EXPLORAÇÃO FLORESTAL EM UMA ÁREA DE TERRA FIRME NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA. Ciência Florestal 2014, 24, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.R.d.; Dacroce, J.M.F.; Rodolfo Junior, F.; Lisboa, G.d.S.; França, L.C.d.J. Lumber Yield of Four Native Forest Species of the Amazon Region. Floresta e Ambiente 2019, 26, e20160311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliprandi, N.C.; Nogueira, E.M.; Toledo, J.J.; Fearnside, P.M.; Nascimento, H.E.M. Inter-site variation in allometry and wood density of <i>Goupia glabra</i> Aubl. in Amazonia. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2016, 76, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBAMA. Report on Timber Industry Waste in the Amazon. Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Resources, 2024.

- IBGE. Systematic Survey of Agricultural Production. https://sidra.ibge.gov.br, 2022. Acesso em: 15 agosto 2024.

- Figueira, J.; Almeida, M.; Silva, R. Waste Production in Amazonian Sawmills. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 254, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz-Miret, N.; Vamos, R.; Hiraoka, M.; Montagnini, F.; Mendelsohn, R.O. The economic value of managing the açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) in the floodplains of the Amazon estuary, Pará, Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management 1996, 87, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainer, K.A.; Wadt, L.H.O.; Staudhammer, C.L. The evolving role of Bertholletia excelsa in Amazonia: contributing to local livelihoods and forest conservation. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 2018, 48, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Guerra, F. Aspectos econômicos da cadeia produtiva dos óleos de andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) e copaíba (Copaifera multijuga Hayne) na Floresta Nacional do Tapajós—Pará. Floresta 2010, 40. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.F.; Buller, L.S.; Maciel-Silva, F.W.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Berni, M.D.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Waste management and bioenergy recovery from açaí processing in the Brazilian Amazonian region: a perspective for a circular economy. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2021, 15, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.S.O.; de Campos Paraense, V. Production chain for brazil-nuts (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) at Ipaú-Anilzinho extractive reserve, municipality of Baião, Pará, Amazonian Brazil. Revista Agro@mbiente On-line 2019, 13, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Nut and Dried Fruit Council (INC). INC NUTS & DRIED FRUITS STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2022/23, 2023. Available online: https://inc.nutfruit.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Statistical-Yearbook-2022-2023.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Mafra, R.Z.; Lasmar, D.J.; Vilela, D.C. Relacionamentos Interorganizacionais na Bioindústria Amazonense na Percepção dos Empresários. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 2019, 23, 672–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Rocha, A.; Tartarotti, N. Sustainable Development as a Wicked Problem: The Case of the Brazilian Amazon Region. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Lv, Z.; Chen, G.; Peng, F. Hemicellulose: Structure, chemical modification, and application. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Green and sustainable pretreatment methods for cellulose extraction from lignocellulosic biomass and its applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.W.; Nair, S.S.; Chen, H.; Yan, N.; Farnood, R.; Li, F.Y. Thermally stable, enhanced water barrier, high strength starch bio-composite reinforced with lignin containing cellulose nanofibrils. *Carbohydr. Polym.* **2020**, *230*, 115626. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xue, J.; Yang, X.; Ke, Y.; Ou, R.; Wang, Y.; Madbouly, S.A.; Wang, Q. From plant phenols to novel bio-based polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 125, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgacem, M.N.; Gandini, A. The surface modification of cellulose fibres for use as reinforcing elements in composite materials. Compos. Interfaces 2005, 12, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, J.; Pettersson, T.; Asaadi, S.; Sixta, H.; Nypelö, T.; Mautner, A.; Konnerth, J. Adhesion properties of regenerated lignocellulosic fibres towards poly(lactic acid) microspheres assessed by colloidal probe technique. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 532, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo-Franco, S.L.; Galvis-Nieto, J.D.; Orrego, C.E. Physicochemical characterization of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea) from Colombian pacific and their potential of mannan-oligosaccharides and sugar production via enzymatic hydrolysis. Biomass Convers. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Buratto, R.T.; Cocero, M.J.; Martín, Á. Characterization of industrial açaí pulp residues and valorization by microwave-assisted extraction. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2021, 160, 108269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.F.; Miguez, I.S.; Silva, J.P.R.B.; Silva, A.S. High concentration and yield production of mannose from açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) seeds via mannanase-catalyzed hydrolysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, M.K.D.; Schmidt, F.L.; Ferreira, M.M.C. Analysis of the lignocellulosic components of biomass residues for biorefinery opportunities. Talanta 2015, 144, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millane, R.P.; Hendrixson, T.L. Crystal structures of mannan and glucomannans. Carbohydr. Polym. 1994, 25, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Várdai, R.; Schäffer, Á.; Ferdinánd, M.; Lummerstorfer, T.; Jerabek, M.; Gahleitner, M.; Faludi, G.; Móczó, J.; Pukánszky, B. Crystalline structure and reinforcement in hybrid PP composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuadi, N.A.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Ismail, K.N. Review study for activated carbon from palm shell used for treatment of waste water. In Proceedings of the Conference on Waste Water Treatment, 2012. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:136130824 (accessed on 23 October 2024); Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:136130824 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Okoroigwe, E.C.; Saffron, C.M.; Kamdem, P.D. Characterization of palm kernel shell for materials reinforcement and water treatment. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Duan, K.; Zhang, J.W.; Lu, X.; Weng, J. The influence of polymer concentrations on the structure and mechanical properties of porous polycaprolactone-coated hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 4586–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, W.A.; Bezerra, F.W.F.; Oliveira, M.S.; Andrade, E.H.A.; Santos, A.P.M.; Cunha, V.M.B.; Santos, D.C.S.; Banna, D.A.D.S.; Teixeira, E.; Carvalho Junior, R.N. Supercritical CO2 extraction and transesterification of the residual oil from industrial palm kernel cake with supercritical methanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 147, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, F.; Samper, M.D.; Carbonell-Verdu, A.; Luzi, F.; López-Martínez, J.; Torre, L.; Puglia, D. Improved toughness in lignin/natural fiber composites plasticized with epoxidized and maleinized linseed oils. Materials 2020, 13, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobre, J.; Napoli, A.; Bianchi, M.; Silva, M.; Numazawa, S. *Use of Residues of Manilkara huberi the State of Para in the Production of Activated Carbon*; 2014.

- Sonego, M.; Fleck, C.; Pessan, L.A. Mesocarp of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) as inspiration for new impact resistant materials. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2019, 14, 056002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, R.I.M.; Abreu, J.J.C.; Martins, C.S.; Santos, I.S.; Bianchi, M.L.; Nobre, J.R.C. Elementary, Chemical and Energy Characteristics of Brazil Nuts Waste (Bertholletia excelsa) in the State of Pará. Floresta Ambiente 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasca, N.; Brito, M.R.; Rambo, M.C.D.; Pedrazzi, C.; Scapin, E.; Rambo, M.K.D. Analysis of the potential of cupuaçu husks (Theobroma grandiflorum) as raw material for the synthesis of bioproducts and energy generation. Food Sci. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, D.T. Avaliação de Propriedades Tecnológicas da Madeira de Quatro Espécies da Amazônia. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido, Mossoró, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.ufersa.edu.br/handle/prefix/8280. Available online: https://repositorio.ufersa.edu.br/handle/prefix/8280 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Bimestre, T.A.; Silva, F.S.; Tuna, C.E.; dos Santos, J.C.; de Carvalho, J.A.; Canettieri, E.V. Physicochemical Characterization and Thermal Behavior of Different Wood Species from the Amazon Biome. Energies 2023, 16, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.S.; Rodrigues, D.A.; Castelo, P.A.R. Determination of Chemical Properties of Woods from Southern Amazon. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2014, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmakumar, M.; Pavithran, C.; Pillai, R.M. Coconut fibre reinforced polyethylene composites: Effect of natural waxy surface layer of the fibre on fibre/matrix interfacial bonding and strength of composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, P.; Guo, J.; Fernández-Blázquez, J.P.; Clark, J.H.; Cui, Y. On the improvement of properties of bioplastic composites derived from wasted cottonseed protein by rational cross-linking and natural fiber reinforcement. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 8642–8655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.; Morreale, M. Green composites: A brief review. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2011, 42, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Production of Sustainable and Biodegradable Polymers from Agricultural Waste. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsissou, R.; Seghiri, R.; Benzekri, Z.; Hilali, M.; Rafik, M.; Elharfi, A. Polymer composite materials: A comprehensive review. Composite Structures 2021, 262, 113640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, M.; Bairwan, R.; Khalil, H. The Role of Natural Fiber Reinforcement in Thermoplastic Elastomers Biocomposites. Fibers Polym 2024, 25, 3061–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Klingler, W.; Bifulco, A.; Polisi, C.; Huang, Z.; Gaan, S. Recyclable inherently flame-retardant thermosets: Chemistry, properties and applications. Composites Part B: Engineering 2023, 258, 110667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Murphy, R.J.; Narayan, R.; Davies, G.B.H. Biodegradable and compostable alternatives to conventional plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, A.; Ashour, F.; Hakim, A. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. npj Mater Degrad 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopanna, A.; Rajan, K.P.; Thomas, S.P.; Chavali, M. Chapter 6—Polyethylene and polypropylene matrix composites for biomedical applications. In Materials for Biomedical Engineering; Grumezescu, V., Grumezescu, A.M., Eds.; Elsevier: 2019; pp. 175–216. [CrossRef]

- Potrykus, M.; Redko, V.; Głowacka, K.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Szarlej, P.; Janik, H.; Wolska, L. Polypropylene structure alterations after 5 years of natural degradation in a waste landfill. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabri, A.; Tahir, F.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Life-Cycle Assessment of Polypropylene Production in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Region. Polymers 2021, 13, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danyluk, C.; Erickson, R.; Burrows, S.; Auras, R. Industrial Composting of Poly(Lactic Acid) Bottles. J. Test. Eval. 2010, 38, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Nattrass, L.; Alberts, G.; Robson, P.; Chudziak, C.; Bauen, A.; Libelli, I.M.; Lotti, G.; Prussi, M.; Nistri, R.; Chiaramonti, D.; López-Contreras, A.M.; Bos, H.L.; Eggink, G.; Springer, J.; Bakker, R.; van Ree, R. From the Sugar Platform to Biofuels and Biochemicals: Final Report for the European Commission Directorate-General Energy. European Commission, 2015. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/360244 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Khan, R.A.; Khan, M.A.; Sultana, S.; Nuruzzaman Khan, M.; Shubhra, Q.T.H.; Noor, F.G. Mechanical, Degradation, and Interfacial Properties of Synthetic Degradable Fiber Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Tuladhar, R.; Shanks, R.A.; Collister, T.; Combe, M.; Jacob, M.; Tian, M.; Sivakugan, N. Fiber preparation and mechanical properties of recycled polypropylene for reinforcing concrete. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, V.; Canesi, I.; Cinelli, P.; Coltelli, M.B.; Lazzeri, A. Rubber Toughening of Polylactic Acid (PLA) with Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT): Mechanical Properties, Fracture Mechanics and Analysis of Ductile-to-Brittle Behavior while Varying Temperature and Test Speed. European Polymer Journal 2019, 115, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, C.-H.; Chen, Z.-J.; Yuan, S.; Ma, Z.-L.; Wu, C.-S.; Yang, T.; Jia, C.-F.; De Guzman, M.R. The preparation and performance of poly(butylene adipate) terephthalate/corn stalk composites. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 5, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourban, P.E.; Bögli, A.; Bonjour, F.; Månson, J.-A.E. Integrated processing of thermoplastic composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1998, 58, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.; Vandi, L.J.; Pratt, S.; Halley, P.; Richardson, D.; Werker, A.; Laycock, B. Composites of Wood and Biodegradable Thermoplastics: A Review. Polymer Reviews 2018, 58, 444–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.U.; Khalid, M.Y.; Sheikh, M.F.; Zolfagharian, A.; Bodaghi, M. Biopolymeric sustainable materials and their emerging applications. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedras, X.; Piñeiro, G.; Castilla, M. Application of agroforestry residues in polymeric composite materials. Materiales Compuestos 2020, 04, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Oladele, I.O.; Okoro, C.J.; Taiwo, A.S.; Onuh, L.N.; Agbeboh, N.I.; Balogun, O.P.; Olubambi, P.A.; Lephuthing, S.S. Modern Trends in Recycling Waste Thermoplastics and Their Prospective Applications: A Review. Journal of Composites Science 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, U.K.; Chawla, K.K. Processing of fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites. International Materials Reviews 2008, 53, 185–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norizan, M.N.; Rahmah, M. A Review: Fibres, Polymer Matrices and Composites. Pertanika Journal of Science and Technology 2017, 25, 1085–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, R.D.; et al. (2015). Effect of Mercerization and Electron-Beam Irradiation on Mechanical Properties of High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) / Brazil Nut Pod Fiber (BNPF) Bio-Composites. In: Carpenter, J.S., et al. Characterization of Minerals, Metals, and Materials 2015. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.; Rodrigues, E.; Prêta, J.; Goulart, S.; Mulinari, D. Mechanical properties of HDPE/textile fibers composites. Procedia Engineering 2011, 10, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.A.C.; de Novais Miranda, E.H.; de Araújo Veloso, M.C.R.; da Silva, M.G.; Ferreira, G.C.; Mendes, L.M.; Júnior, J.B.G. Production and characterization of recycled low-density polyethylene/amazon palm fiber composites. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 201, 116833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.; Versino, F.; López, O. Biobased composites from agro-industrial wastes and by-products. Emergent Materials 2022, 5, 873–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, M.; Shekhawat, D.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J. The role of fillers to enhance the mechanical, thermal, and wear characteristics of polymer composite materials: A review. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2023, 175, 107775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Long, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.Z. Recovery of epoxy thermosets and their composites. Materials Today 2023, 64, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C.P.; Fleming, R.; Goncalves, A.M.B.; da Silva, M.J.; Prataviera, R.; Cena, C. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of epoxy/sawdust (Pinus elliottii) composites. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2021, 29, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, G.; Arvindh Seshadri, S.; Devnani, G.; Sanjay, M.; Siengchin, S.; Prakash Maran, J.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Karuppiah, P.; Mariadhas, V.A.; Sivarajasekar, N.; et al. Environment friendly, renewable and sustainable poly lactic acid (PLA) based natural fiber reinforced composites—A comprehensive review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 310, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Mohamad, F.; Ahmad, M.H.; AbdulGhani, A. Sustainability of biodegradable plastics: New problem or solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 5, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R.; Maio, A.; Sutera, F.; Gulino, E.F.; Morreale, M. Degradation and Recycling of Films Based on Biodegradable Polymers: A Short Review. Polymers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Pinheiro, I.F.; Mariano, M.; Cividanes, L.S.; Costa, J.C.; Nascimento, N.R.; Kimura, S.P.; Neto, J.C.; Lona, L.M. Environmentally friendly polymer composites based on PBAT reinforced with natural fibers from the amazon forest. Polymer Composites 2019, 40, 3351–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, I.; Morales, A.; Mei, L. Polymeric biocomposites of poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) reinforced with natural Munguba fibers. Cellulose 2014, 21, 4381–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, E.; Punhagui, K.; John, V. CO2 footprint of Amazon lumber: A meta-analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2021, 167, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, V.; Peres, C. Temporal Decay in Timber Species Composition and Value in Amazonian Logging Concessions. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, P.; Reis, A.; Moraes, M.; Christoforo, A.; Nascimento, M.; Lahr, F.; Silva, M. Determinação do processo produtivo de painéis homogêneos de partículas com resíduos amazônicos com identificação anatômica da biomassa. Caderno Pedagógico 2024, 21, e4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, W.; Ruivo, M.; Jardim, M.; Sousa, L. Geração de resíduos madeireiros do setor de base florestal na região metropolitana de Belém, Pará. Ciência Florestal 2018, 28, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Z.M.d.S.H.d.; Evangelista, W.V.; Araújo, S.d.O.; Souza, C.C.d.; Ribeiro, F.D.L.; Silva, J.d.C. Análise dos resíduos madeireiros gerados nas marcenarias do município de Viçosa—Minas Gerais. Revista Árvore 2010, 34, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham, J.; Ellis, T. Potentials of Wood for Producing Energy. Journal of Forestry 1974, 72, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhães, J. Uso da Biomassa Florestal como Fonte de Energia. Floresta e Ambiente 1994, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerhuber, P.; Welling, J.; Krause, A. Substitution potentials of recycled HDPE and wood particles from post-consumer packaging waste in Wood–Plastic Composites. Waste Management 2015, 46, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J. M. C. de S., Santos, D. T. dos, Braga, M., Onoyama, M. M., Miranda, C. H. B., Barbosa, P. F. D., & Rocha, J.D. Produção de briquetes e péletes a partir de resíduos agrícolas, agroindustriais e florestais (1ª ed., 130 p.). Embrapa Agroenergia. Brasília, DF: Embrapa Agroenergia. (Documentos / Embrapa Agroenergia, ISSN 2177-4439; n. 013). Disponível em: https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/78690/1/DOC-13.pdf. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Zapata, R.; Palma-Ramírez, D.; Flores-Vela, A.; Romero-Partida, J.; Paredes-Rojas, J.; Márquez-Rocha, F.; Bravo-Díaz, B. Structural and thermal study of hemicellulose and lignin removal from two types of sawdust to isolate cellulose. MRS Advances 2022, 7, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C.; Fleming, R.; Goncalves, A.; da Silva, M.; Prataviera, R.; Cena, C. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of epoxy/sawdust (Pinus elliottii) composites. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2021, 29, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatarajan, S.; Subbu, C.; Athijayamani, A.; Muthuraja, R. Mechanical properties of natural cellulose fibers reinforced polymer composites—2015–2020: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimestre, T.; Silva, F.; Tuna, C.; dos Santos, J.; de Carvalho, J.; Canettieri, E. Physicochemical Characterization and Thermal Behavior of Different Wood Species from the Amazon Biome. Energies 2023, 16, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuoto, M. Levantamento sobre a geração de resíduos provenientes da atividade madeireira e proposição de diretrizes para políticas, normas e condutas técnicas para promover o seu uso adequado. Projeto PNUD BRA 00/20—Apoio às Políticas Públicas na Área de Gestão e Controle Ambiental, 2009.

- da Silva Luz, E.; Soares, A.A.V.; Goulart, S.L.; Carvalho, A.G.; Monteiro, T.C.; de Paula Protásio, T. Challenges of the lumber production in the Amazon region: relation between sustainability of sawmills, process yield and logs quality. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 23, 4924–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.; Almeida, M.; Silva, R. Waste Production in Amazonian Sawmills. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 254, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

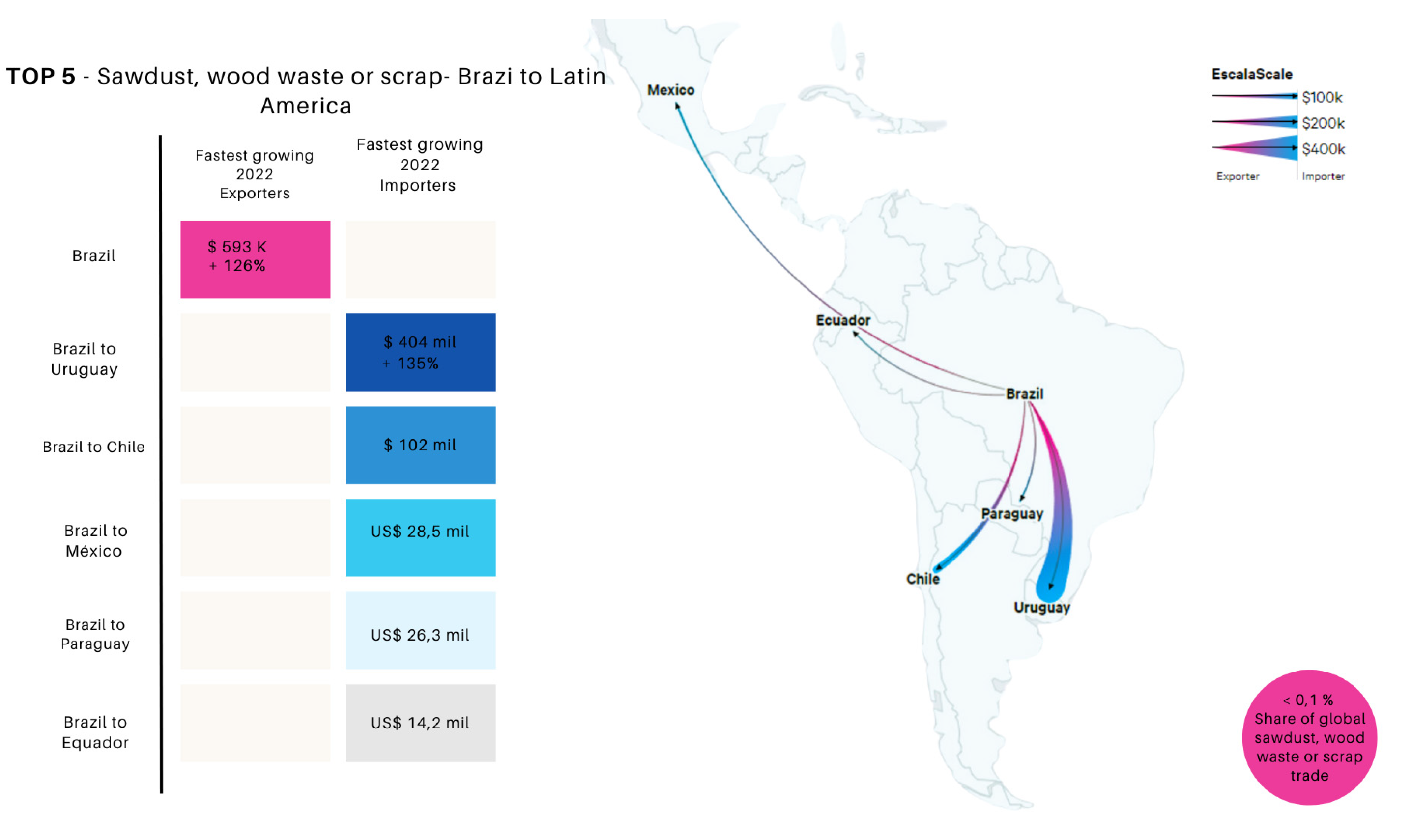

- United Nations. UN Comtrade database, 2016. Accessed on: 23 August 2024.

- Phiri, R.; Mavinkere Rangappa, S.; Siengchin, S.; Oladijo, O.P.; Dhakal, H.N. Development of sustainable biopolymer-based composites for lightweight applications from agricultural waste biomass: A review. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2023, 6, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.M.; de Araújo, A.B.S.; Giacon, V.M.; Faez, R. Does the moisture content of mercerized wood influence the modulus of rupture of thermopressed polyurethane-based composites? Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 206, 117585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surdi, P.G.; Bortoletto Júnior, G.; Castro, V.R.d.; Brito, F.M.S.; Berger, M.d.S.; Zanuncio, J.C. PARTICLEBOARD PRODUCTION WITH RESIDUES FROM MECHANICAL PROCESSING OF AMAZONIAN WOODS. Revista Árvore 2019, 43, e430102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, R.A. A comprehensive review on utilization of waste materials in wood plastic composite. Materials Today Sustainability 2024, 27, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra, S.C.; Braga, N.F.; Morgado, G.F.d.M.; Montanheiro, T.L.d.A.; Marini, J.; Passador, F.R.; Montagna, L.S. Development of new biodegradable composites materials from polycaprolactone and wood flour. Wood Material Science & Engineering 2021, 17, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.B.; de Souza, A.G.; Szostak, M.; Rosa, D.d.S. Polylactic acid/Lignocellulosic residue composites compatibilized through a starch coating. Polymer Composites 2020, 41, 3250–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, D.S.; Banna, W.R.E.; Fujiyama, R.T. Wood Residue of Jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril) and Short Fiber of Malva in Composites. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental 2023, 18, e04194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.S.B.; Luna, C.B.B.; Araújo, E.M.; Siqueira, D.D.; Wellen, R.M.R. Polypropylene/wood powder composites: Evaluation of PP viscosity in thermal, mechanical, thermomechanical, and morphological characters. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2019, 35, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Leitão, V.; Gottschalk, L.M.F.; Ferrara, M.A.; Nepomuceno, A.L.; Molinari, H.B.C.; Bon, E.P.S. Biomass Residues in Brazil: Availability and Potential Uses. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2010, 1, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xia, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H. Improvement of Rice Husk/HDPE Bio-Composites Interfacial Properties by Silane Coupling Agent and Compatibilizer Complementary Modification. Polymers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- wei Zhang, C.; Nair, S.S.; Chen, H.; Yan, N.; Farnood, R.; yi Li, F. Thermally stable, enhanced water barrier, high strength starch bio-composite reinforced with lignin containing cellulose nanofibrils. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 230, 115626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lala, S.D.; Deb, P.; Barua, E.; Deoghare, A.B.; Chatterjee, S. A comparative study on mechanical, physico-chemical, and thermal properties of rubber and walnut seed shell reinforced epoxy composites and prominent timber species. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2023, 237, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naduparambath, S.; Sreejith, M.P.; Jinitha, T.V.; Shaniba, V.; Aparna, K.B.; Purushothaman, E. Development of green composites of poly (vinyl alcohol) reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose derived from sago seed shells. Polymer Composites 2018, 39, 3033–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.; Moura, E.; Arenhardt, V.; Deliza, E.E.V.; Pedro Filho, F.d.S. Biotechnology management in the Amazon and the production of polypropylene / Brazil Nut Shell fiber biocomposite. Revista de Gestão e Secretariado 2023, 14, 10734–10748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Barbosa, A.; dos Santos, G.M.; de Melo, G.M.M.; Litaiff, H.A.; Martorano, L.G.; Giacon, V.M. Evaluation of the use of açaí seed residue as reinforcement in polymeric composite. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2022, 30, 09673911221108307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayssa, S. Lima, A.P.A.d.C.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Health from Brazilian Amazon food wastes: Bioactive compounds, antioxidants, antimicrobials, and potentials against cancer and oral diseases. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 12453–12475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.S.; Raabe, J.; Dias, L.M.; Baliza, A.E.R.; Costa, T.G.; Silva, L.E.; Vasconcelos, R.P.; Marconcini, J.M.; Savastano, H.; Mendes, L.M. Main Characteristics of Underexploited Amazonian Palm Fibers for Using as Potential Reinforcing Materials. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 3125–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhani, G.C.; dos Santos, D.F.; Koester, D.L.; Biduski, B.; Deon, V.G.; Machado Junior, M.; Pinto, V.Z. Application of Corn Fibers from Harvest Residues in Biocomposite Films. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2021, 29, 2813–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.G.; Onifade, D.V.; Ighalo, J.O.; Adeoye, A.S. A review of coir fiber reinforced polymer composites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2019, 176, 107305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cionita, T.; Siregar, J.P.; Shing, W.L.; Hee, C.W.; Fitriyana, D.F.; Jaafar, J.; Junid, R.; Irawan, A.P.; Hadi, A.E. The Influence of Filler Loading and Alkaline Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Kernel Cake Filler Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, C.; Cardoso, F.; Neumann, F.; Felix, J.; Teixeira, L. Valorização de resíduos da indústria do açaí: oportunidades e desafios. Report prepared by the SENAI Institute for Innovation in Biosynthetics and Fibers, 2021. Prepared on December 13, 2021, 2021, Rio de Janeiro.

- Araújo, S.; Santos, G.; Tolosa, G.; Hiranobe, C.; Budemberg, E.; Cabrera, F.; Silva, M.; Paim, L.; Job, A.; dos Santos, R. Acai Residue as an Ecologic Filler to Reinforcement of Natural Rubber Biocomposites. Materials Research 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.O.M. Compostos voláteis, perfil de aroma, de ácidos graxos e potencial antioxidante de óleo extraído por prensagem a frio de resíduo agroindustrial de açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). Master’s thesis, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristóvão, SE, Brasil, 2017. Dissertação de Mestrado.

- Santos, J.P.; Braga, L.F.; Ruedell, C.M.; Seben Júnior, G.d.F.; Ferbonink, G.F.; Caione, G. Caracterização física de substratos contendo resíduos de cascas de amêndoas de castanha-do-brasil (Bertholletia excelsa H. B.K.). Revista de Ciências Ambientais 2018, 12, 2813–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J.T.d. Aproveitamento de resíduos da indústria de óleos vegetais produzidos na Amazônia. Master’s thesis, Federal University of Pará, Belém, Brazil, 2014. Master’s thesis.

- Chavalparit, O.; Rulkens, W.H.; Mol, A.P.J.; Khaodhair, S. Options for Environmental Sustainability of the Crude Palm Oil Industry in Thailand Through Enhancement of Industrial Ecosystems. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2006, 8, 8–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.A.F.; Andrade, H.A.F.d.; Parra-Serrano, L.J.; Furtado, M.B.; Silva-Matos, R.R.S.d.; Farias, M.F.d.; Furtado, J.d.L.B. Technological Characterization and Use of Babassu Residue (Orbygnia phalerata Mart.) in Particleboard. Journal of Agricultural Science 2017, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, A.C.; Santana, G.P.; Santos, M.C.D.; Neto, J.C.D.M.; Pino, G.G.D.; Santos, M.D.D.; Duvoisin, S.; Panzera, T.H. Wood-plastic Composite Based on Recycled Polypropylene and Amazonian Tucumã (Astrocaryum aculeatum) Endocarp Waste. Fibers and Polymers 2021, 22, 2834–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, S.S.; Santos, G.T.A.; Tolosa, G.R.; Hiranobe, C.T.; Budemberg, E.R.; Cabrera, F.C.; Silva, M.J.; Paim, L.L.; Job, A.E.; Santos, R.J. Acai Residue as an Ecologic Filler to Reinforcement of Natural Rubber Biocomposites. Mater. Res. 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataya, C.H.; Lima, R.A.; Oliveira, R.R.; Moura, E.A.B. Mechanical, Morphological and Thermal Properties of Açaí Fibers Reinforced Biodegradable Polymer Composites. In Characterization of Minerals, Metals, and Materials 2015; Carpenter, J.S., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, V.C.; De Barros, S.; Banea, M.D.; Brede, M.; De Carvalho, L.H.; Hoffmann, R.; Costa, A.R.M.; Bezerra, E.B.; Silva, I.D.S.; Haag, K.; et al. Effect of Babassu Natural Filler on PBAT/PHB Biodegradable Blends: An Investigation of Thermal, Mechanical, and Morphological Behavior. Materials 2018, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela, T.G.R.; Costa, L.L.; Monteiro, S.N. Resistência à Tração de Compósitos Poliméricos Reforçados com Fibras Alinhadas de Buriti. In Proceedings of the 65º Congresso ABM, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 2010; pp. 3154–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Common Name (Scientific Name) | Reference | Cellulose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Extractives (%) | Ash (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palm Kernel Shell (PKS) | Fuadi et al. [85] | 29,7 | 47,7 | 53,4 | - | 1,1 |

| Palm Kernel Shell (PKS) | Okoroigwe et al. [86] | 6,92 | 26,11 | 53,85 | - | 8,68 |

| Açaí Seeds (Euterpe oleracea) | Murillo-Franco et al. [78] | 11,58 | 37,88 | 14,12 | 4,09 | 1,57 |

| Açaí Seeds (Euterpe oleracea) | Buratto et al. [79] | 8,5 | 48,1 | 16,4 | 13,1 | 0,96 |

| Brazil Nut Mesocarp (Bertholletia excelsa) | Sonego et al. [90] | 15,9 | 15,7 | 56 | 2,5 | 6,2 |

| Brazil Nut Waste (Bertholletia excelsa) | Leandro et al. [91] | - | 37,09 | 55,76 | 4,54 | 2,61 |

| Cupuaçu Husk (Theobroma grandiflorum) | Marasca et al. [92] | 49,43 | 10,13 | 11,36 | 13,94 | 2,36 |

| Maçaranduba Sawdust (Manilkara huberi) | Nobre et al. [89] | 69,41* | - | 34,68 | 7,36 | 0,33 |

| Maçaranduba Sawdust (Manilkara huberi) | Medeiros [93] | 66* | - | 29 | 5 | 0 |

| Mandioqueira Wood (Ruizterania albiflora) | Bimestre et al. [94] | 55,9 | 9,23 | 28,71 | 3,29 | 1,12 |

| Cambará Wood (Vochysia sp.) | Bimestre et al. [94] | 49,5 | 12,56 | 32,28 | 0,18 | 3,9 |

| Amescla Wood (Trattinnickia sp.) | Bimestre et al. [94] | 45,18 | 13,38 | 33,86 | 0,71 | 1,72 |

| Angelim-pedra (Hymenolobium petraeum) | Almeida et al. [95] | 73,15* | - | 23,84 | 3,01 | - |

| Study | Timber Residue | Composition | Improved Properties | Original Values | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santos et al. [151] | Louro Itaúba, Louro Gamela, Maçaranduba |

5-10% NaOH-treated wood residue |

Modulus of Rupture: Louro Gamela (16 MPa), Louro Itaúba (9 MPa), Maçaranduba (11 MPa) |

Louro Gamela (12 MPa), Louro Itaúba (2 MPa), Maçaranduba (3 MPa) |

Gamela: +33%, Itaúba: +350%, Maçaranduba: +266% |

| Rocha et al. [155] | Maçaranduba, Pinus, Sugarcane Bagasse |

PLA with 20% Maçaranduba/ Pinus residues |

Young’s Modulus: Pinus (+34%), Maçaranduba (+15%). Impact Absorption: Maçaranduba (+0.357 J/m) |

Young’s Modulus: 2.6 GPa, Impact Absorption: 0.193 J/m |

+34% (Pinus), +15% (Maçaranduba) |

| Surdi et al. [152] | Caryocar villosum, Hymenolobium excelsum, Tachigali myrmecophyla |

8% Phenol-formaldehyde resin with wood residues |

Modulus of Rupture (10.04 MPa), Modulus of Elasticity (1616.74 MPa) |

Modulus of Rupture: 8.5 MPa, Modulus of Elasticity: 1400 MPa |

Rupture: +18%, Elasticity: +15% |

| Costa et al. [156] | Jatobá + Malva Fibers | 75% Jatobá wood + 25% Malva fibers |

Tensile Strength: 26.06 MPa | Tensile Strength: 25.09 MPa | +4% |

| Ferreira et al. [157] | Jatobá Wood Powder | 40% Jatobá wood powder in PP |

Elastic Modulus: 2000 Mpa | Elastic Modulus: 800 MPa | +59% |

| Study | Timber Residue | Composition | Improved Properties | Original Values | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbosa et al. [164] | Açaí Seed | Polymer composite with 30% açaí seed | Lower water absorption (21.11%) with larger particles, better bonding strength |

Water absorption: 56.65% | -63% water absorption |

| Cionita et al. [169] | Palm Kernel Cake | Epoxy with 30% PKC | Tensile Strength: 31.20 MPa, Flexural Strength: 39.70 MPa |

Tensile Strength: 22.90 MPa, Flexural Strength: 30.50 MPa |

Tensile: +36%, Flexural: +30% |

| Kieling et al. [177] | Tucumã Endocarp | Recycled PP with 0–50 wt% Tucumã endocarp powder (TEP) | Increased tensile and flexural modulus (+28% to +30%), improved compressive strength (+134%) with 40 wt% TEP | Tensile Modulus: 0.73 GPa (PP100) Flexural Modulus: 1.13 GPa (PP100) |

Modulus: +28% (0.94 GPa with 50 wt% TEP) Flexural Modulus: +30% (1.48 GPa with 50 wt% TEP) |

| Araújo et al. [178] | Açaí Seed | Natural rubber with 0–50 phr açaí seed | Increased tensile strength, Increased Elastic Modulus | Tensile Strength: 5.2 MPa (0 phr) Elastic Modulus: 0.8 MPa (0 phr) | Tensile Strength: +65% (at 50 phr) Young’s Modulus: +127.5% (at 50 phr, 1.82 MPa) |

| Wataya et al. [179] | Açaí Seed Fiber | PBAT/PLA (50/50 wt%) with 30% açaí seed fiber | Increased elongation at break (+17%) | Elongation: 12.8% (PBAT/PLA blend) | Elongation: +17% (15.02%) |

| Beber et al. [180] | Babassu Mesocarp | PBAT/PHB (25/75, 50/50, 75/25) with 20% Babassu | Increased Young’s Modulus (+19.4%), slight increase in stiffness | Young’s Modulus: 334 MPa (50/50 blend) | Young’s Modulus: +19.4% (for 25/75 blend with Babassu) |

| Portela et al. [181] | Buriti Fiber | Epoxy (DGEBA/TETA) with 0%, 10%, 20%, 30% buriti fiber | Increased tensile strength (+22.8%), improved modulus (+57%) with 30% fiber content | Tensile Strength: 61.94 MPa (0% fiber) Modulus: 0.97 GPa (0% fiber) |

Tensile Strength: +22.8% (76.07 MPa with 30% fiber) Modulus: +57% (1.52 GPa with 30% fiber) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).