Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

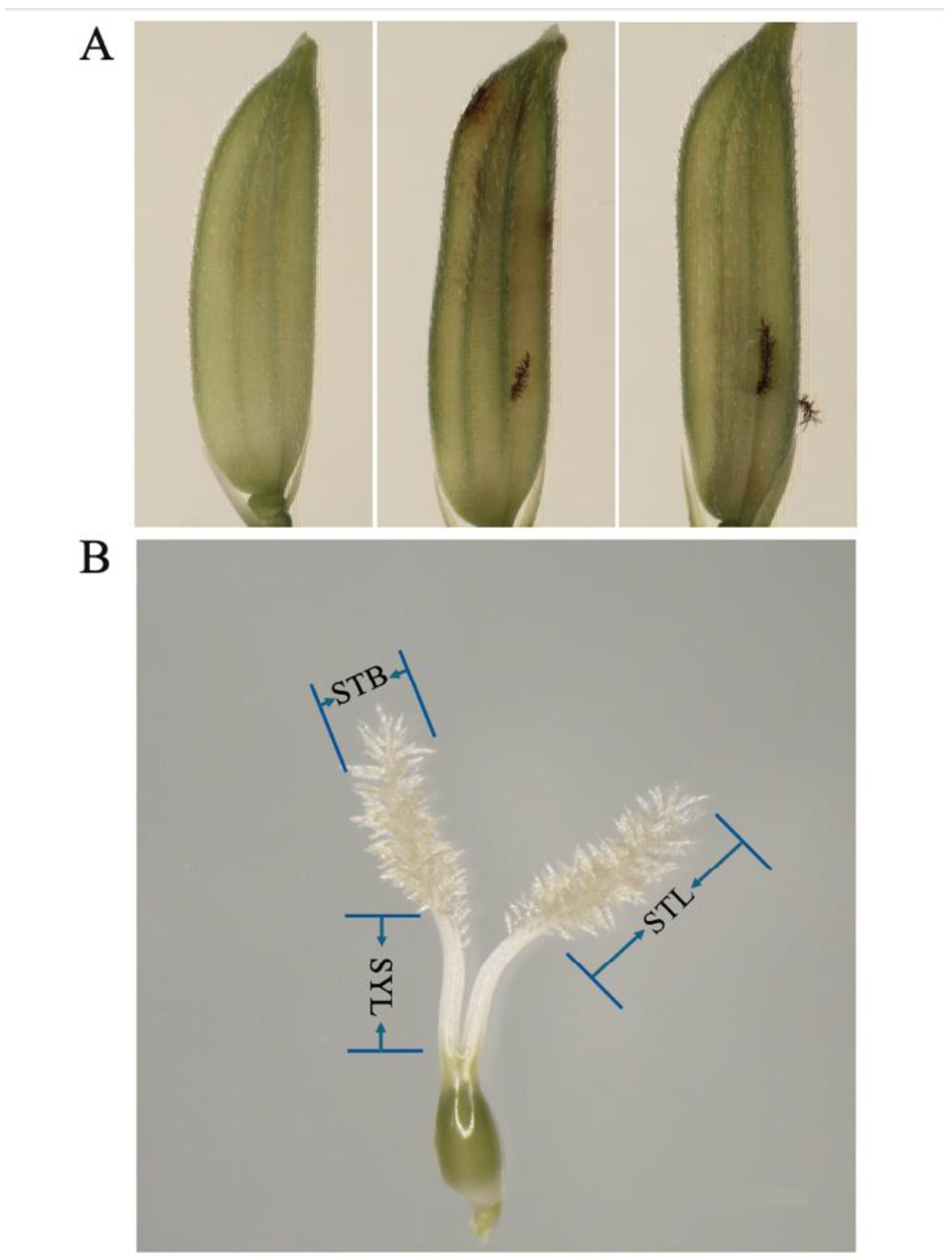

2. Rice Stigma Exposed

3. Genetic Studies on Stigma Traits in Rice

4. Correlation of Floral Organs and Stigma in Rice

5. Interspecific Variation and Stigma Exsertion in Rice

6. Identified QTL for Stigma Exsertion in Rice

7. Localization of QTL for Other Traits in Rice Stigma

8. Gene Cloning for Stigma Exsertion in Rice

9. Breeding Utilization of QTLs for Rice Stigma Exsertion

10. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, S.; Zhuang, J.; Fan, Y.; Du, J.; Cao, L. Progress in research and development on hybrid rice: a super-domesticate in China. Ann Bot. 2007, 100, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yang, D.; Zhu, Y. Characterization and Use of Male Sterility in Hybrid Rice Breeding. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, S.; Gong, J.; Zhao, Q.; Feng, Q.; Zhan, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Cheng, B.; Xia, J. Genomic architecture of heterosis for yield traits in rice. Nature 2016, 537, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y. The Advantages, Challenges and Internationalization Strategies of China’s Hybrid Rice. China Rice 2019, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, H.; Ghouri, F.; Baloch, F.S.; Nadeem, M.A.; Fu, X.; Shahid, M.Q. Hybrid Rice Production: A Worldwide Review of Floral Traits and Breeding Technology, with Special Emphasis on China. Plants 2024, 13, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Tang, Q.; Mo, W.; Ma, J. Effects of Gibberellic Acid Application after Anthesis on Seed Vigor of Indica Hybrid Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agronomy 2019, 9, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElShamey, E.A.; Hamad, H.S.; Alshallash, K.S.; Alghuthaymi, M.A.; Ghazy, M.I.; Sakran, R.M.; Selim, M.E.; ElSayed, M.A.; Abdelmegeed, T.M.; Okasha, S.A. Growth regulators improve outcrossing rate of diverse rice cytoplasmic male sterile lines through affecting floral traits. Plants 2022, 11, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hua, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Quan, Y.; Ru, H.; Yu, A.; Yao, J.; Wang, Z. Breeding and application of japonica male sterile lines with high stigma exsertion rate in rice. Hybrid Rice 2008, 23, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Purugganan, M.D.; Fuller, D.Q. The nature of selection during plant domestication. Nature 2009, 457, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidharthan, B.; Thiyagarajan, K.; Manonmani, S. Cytoplasmic male sterile lines for hybrid rice production. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2007, 3, 935–937. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L.; She, K. Increasing Outcrossing Rate of Indica Hybrid Rice. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. 2000, (03), 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Li, W.; Lu, H. Combining ability of floral characters in rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 1987, (03), 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Chen, Y. Genetic study on stigma extrusion of rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 1987, (04), 314–321. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Yang, R.; Zhang, S. Heritable and Correlation Analysis of Several Restore Line’s Floral Character. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2003, 31, 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Yan, J.; Zhang, N.; Xue, Q. Genetic analysis for some floral characters in hybridization between india and japonica rice. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis. 1994, 6, 222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam, A.; Saraswathi, R.; Ramalingam, J.; Jayaraj, T. Genetics of floral traits in cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) and restorer lines of hybrid rice (Oryza sativa L.). Pak. J. Bot. 2013, 45, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Virmani, S.S.; Athwal, D.S. Genetic variability in floral characteristics influencing outcrossing in Oryza sativa L. Crop Sci. 1973, 13, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uga, Y.; Fukuta, Y.; Cai, H.; Iwata, H.; Ohsawa, R.; Morishima, H.; Fujimura, T. Mapping QTLs influencing rice floral morphology using recombinant inbred lines derived from a cross between Oryza sativa L. and Oryza rufipogon Griff. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 107, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Z.; Song, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y. Genetic Analysis of Floral Characters in A DH Population Derived from An indica/japonica Cross of Rice. J. Wuhan Bot. Res. 2003, 21, 559–563. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Li, Y.; Agrama, H.A.; Luo, D.; Gao, F.; Lu, X.; Ren, G. Association mapping of stigma and spikelet characteristics in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Breed. 2009, 24, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Komori, T.; Nitta, N. Marker-assisted selection and evaluation of the QTL for stigma exsertion under japonica rice genetic background. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007, 114, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marathi, B.; Ramos, J.; Hechanova, S.L.; Oane, R.H.; Jena, K.K. SNP genotyping and characterization of pistil traits revealing a distinct phylogenetic relationship among the species of Oryza sativa L. Euphytica 2015, 201, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishima, H.; Hinata, K.; Oka, H.I. Comparison of modes of evolution of cultivated forms from two wild rice species, Oryza breviligulata and O. perennis. Evolution 1963, 17, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.I.; Narise, T. Studies on the breeding behavior of wild rice. Annu. Rep. Natl. Inst. Genet. 1959, 2, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, H.I.; Morishima, H. Variations in the breeding systems of a wild rice, Oryza perennis. Evolution 1967, 21, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, C.; Zhang, S. Studies on the Character of Stigma Exsertion Among Some of Oryza Species (in English). Chin J. Rice Sci. 1989, 3, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Uga, Y.; Fukuta, Y.; Ohsawa, R.; Fujimura, T. Variations of floral traits in Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) and its wild relatives (O. rufipogon Griff.). Breed Sci. 2003, 53, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Ying, C. Study on improving percentage of cross pollination in rice I. Analysis on variation of stigma exertion in Coryza sativa L. Acta Agric. Univ. Zhejiangensis. 1986, (04), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba, A.; Vivekanandan, P.; Ibrahim, S.M. Genetic variability for floral traits influencing outcrossing in the CMS lines of rice. Indian J. Agric. Res. 2006, 40, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Studies on the fertility and flowering Habits of photoperlod (thermo-) sensitive genic male-sterile rice. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 1992, 20, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, K.; Wen, H.; Luo, W. Analysis on cytoplasm-nucleus-interaction of outcrossing traits in indica rice (O. sativa L. Sip indica). J. Sichuan Agric. Univ. 1995, 13, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Xiong, C.; Zhang, H. Correlation Between Outcrossing Characteristics and Stigma Feature of 5 PTGMS Lines. Crop Res. 2015, 29, 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Khumto, S.; Sreethong, T.; Pusadee, T.; Rerkasem, B.; Jamjod, S. Variation of floral traits in Thai rice germplasm (Oryza sativa). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathi, B.; Jena, K.K. Floral traits to enhance outcrossing for higher hybrid seed production in rice: Present status and future prospects. Euphytica 2015, 201, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Liu, K.; Dai, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Q. Identification of genetic factors controlling domestication traits of rice using an F2 population of a cross between Oryza sativa and O.rufipogon. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 98, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, C.; Mu, P.; Chen, L.; Wang, X. QTL analysis of anther Length and ratio of stigma exertion, two key traits of classification for cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) and common wild rice (O.rufipogon Griff.). Acta Genet. Sinica 2001, 28, 746–751. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Dong, G.; Hu, X.; Teng, S.; Guo, L.; Zeng, D.; Qian, Q. QTL Analysis forPercentage of Exserted Stigma in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Acta Genet. Sinica 2003, 30, 637–640. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T.; Takemori, N.; Sue, N. QTL analysis of stigma exsertion in rice. Rice Genet. Newsl. 2003, 10, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Mei, H.; Luo, L.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Zou, G.; Hu, S.; Li, M.; Wu, J. Dissection of additive, epistatic effect and Q×E interaction of quantitative trait loci influencing stigma exsertion under water stress in rice. Acta Genet. Sinica 2006, 33, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Huang, L.; Jiang, J.; Hong, D. Mapping QTLs for four traits relating to outcrossing in rice(Oryza sativa L.). J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2007, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, G.; Mei, H.; Pan, B.; Lou, J.; Li, M.; Luo, L. Mapping of QTLs affecting stigma exsertion rate of Huhan1B as a CMS maintainer of upland hybrid rice. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis. 2009, 21, 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Ying, J.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, H. Mapping of QTLs for percentage of exserted stigma in rice. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. 2010, 36, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Jing, Y.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W. QTL Analysis of Percentage of Exserted Stigma in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). North Rice. 2010, 40, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Gao, F.; Zeng, L.; Li, Q.; Lu, X.; Li, Z.; Ren, J.; Su, X.; Ren, G. QTL Analysis of Rice Stigma Morphology Using an Introgression Line from Oryza Longistaminata L. Mol. Plant Breed. 2010, 8, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Hua, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Su, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y. Inheritance Analysis and Detection of QTLs for Exserted Stigma Rate in Rice. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2011, 42, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Xiao, C.; Deng, H.; Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y. Detection of QTL Related to Stigma Exsertion Rate (SER) in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by Bulked Segregant Analysis. Res. Agric. Modern. 2011, 32, 230–233. [Google Scholar]

- Takano-Kai, N.; Doi, K.; Yoshimura, A. GS3 participates in stigma exsertion as well as seed length in rice. Breed. Sci. 2011, 61, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Li, P.; Gao, G.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, L.; He, Y. QTL Analysis of Percentage of Exserted Stigma in Rice. Mol. Plant Breed. 2014, 12, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chao, Y.; Gao, G.; He, Y. Genetic mapping and validation of quantitative trait loci for stigma exsertion rate in rice. Mol. Breed. 2014, 34, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Su, G.; Feng, F.; Wang, P.; Yu, S.; He, Y. Mapping of minor quantitative trait loci (QTLs) conferring fertility restoration of wild abortive cytoplasmic male sterility and QTLs conferring stigma exsertion in rice. Plant Breed. 2014, 133, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Yue, G.; Yang, W.; Mei, H.; Luo, L.; Lu, H. Mapping QTLs influencing stigma exertion in rice. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 20, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.H.; Yu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Wu, W.; Shen, X.; Zhan, X.; Chen, D.; Cao, L.; Cheng, S. Quantitative trait loci mapping of the stigma exertion rate and spikelet number per panicle in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, gmr15048432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Qiu, F.; Gandhi, H.; Kadaru, S.; De Asis, E.J.; Zhuang, J.; Xie, F. Genome-wide association study of outcrossing in cytoplasmic male sterile lines of rice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Rahman, M.S.; Barman, H.N.; Riaz, A.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhan, X.; Cao, L. Genetic dissection of the major quantitative trait locus (qSE11), and its validation as the major influence on the rate of stigma exsertion in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, K.; Rahman, M.S.; Wu, W.; Zhan, X.; Cao, L.; Cheng, S. Genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci for the stigma exsertion rate in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sheng, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, X.; Shi, L.; Wu, Y.; Tang, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, P. QTL Mapping of japonica Rice Stigma Exsertion Rate. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2017, 31, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Li, P.; Xie, W.; Hussain, S.; Li, Y.; Xia, D.; Zhao, H.; Sun, S.; Chen, J.; Ye, H. Genome-wide Association Analyses Reveal the Genetic Basis of Stigma Exsertion in Rice. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, F.; Ge, T.; Sun, H. Genetic analysis and gene mapping of a low stigma exposed mutant gene by high-throughput sequencing. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0186942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Li, G.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, S. QTL Analysis of Exsertion Rate and Color of Stigma in Rice (Oryza sative L.). Shandong Agric. Sci. 2018, 50, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhan, X.; Anis, G.B.; Rahman, M.H.; Hong, Y.; Riaz, A.; Zhu, A.; Cao, Y.; et al. qSE7 is a major quantitative trait locus (QTL) influencing stigma exsertion rate in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakti, C.; Tanaka, J. Detection of dominant QTLs for stigma exsertion ratio in rice derived from Oryza rufipogon accession 'W0120'. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Wang, F.; Kong, D.; Li, M.; Bi, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Pan, Z.; Yu, X.; Liu, G.; Luo, L. Fine mapping a quantitative trait locus, qSER-7, that controls stigma exsertion rate in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 2019, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Tan, Y.; Qian, Q.; Shu, Q.; Huang, J. Identification of a major quantitative trait locus and its candidate underlying genetic variation for rice stigma exsertion rate. Crop J. 2019, 7, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. QTL Mapping of High Percentage of Stigma Exsertion in Rice Maintainer Line 58B. Hybrid Rice 2020, 35, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Zou, T.; Zheng, M.; Ni, Y.; Luan, X.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zeng, R.; Liu, G.; Wang, S.; Fu, X.; Zhang, G. Substitution Mapping of the Major Quantitative Trait Loci Controlling Stigma Exsertion Rate from Oryza glumaepatula. Rice 2020, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, S.; Sun, L.; He, N.; Pan, X.; Liu, Z.; Fu, X. QTLs detection and pyramiding for stigma exsertion rate in wild rice species by using the single-segment substitution lines. Mol. Breed. 2020, 40, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, L.; Xiao, M.; Hu, C.; Dang, X. Genetic analysis and QTLs identification of stigma traits in japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 2021, 217, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, C.; Luan, X.; Zheng, L.; Ni, Y.; Yang, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zeng, R.; Liu, G. Dissection of closely linked QTLs controlling stigma exsertion rate in rice by substitution mapping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 34, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tai, D.; Zhang, P.; Gao, G.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y. Mapping QTLs for Rice Stigma Exsertion Rate using Recombinant Inbred Line Population. Mol. Plant Breed. 2022, 20, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, N.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Tang, S.; An, R.; Wei, X.; Hu, S.; Tang, S.; Shao, G.; Jiao, G. Fine mapping and target gene identification of qSE4, a QTL for stigma exsertion rate in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 959859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, D.; Kong, D.; Ma, X.; Zhang, A.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Xia, H.; Liu, G.; Yu, X. Linkage mapping and association analysis to identify a reliable QTL for stigma exsertion rate in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 982240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Ni, Y.; Wu, S.; Luan, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, R. Fine Mapping of QTLs for Stigma Exsertion Rate from Oryza glaberrima by Chromosome Segment Substitution. Rice Sci. 2022, 29, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Bu, S.; Chen, G.; Yan, Z.; Chang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yang, W.; Zhan, P.; Lin, S.; Xiong, L. Reconstruction of the High Stigma Exsertion Rate Trait in Rice by Pyramiding Multiple QTLs. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 921700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Wan, H.; Gao, J.; Gu, W.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wan, J. Mapping of QTL qTSE4 for stigma exsertion rate in rice. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2023, 46, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Dan, J.; Li, X.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, S.; Song, R.; Fu, X. Fine-Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis of qSERg-1b from O. glumaepatula to Improve Stigma Exsertion Rate in Rice. Agronomy 2024, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, S.S. Heterosis and hybrid rice breeding. (Springer, Berlin). 1994.

- Uga, Y.; Siangliw, M.; Nagamine, T.; Ohsawa, R.; Fukuta, Y. Comparative mapping of QTLs determining glume, pistil and stamen sizes in cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Breed. 2010, 129, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qin, J.; Li, T.; Liu, E.; Fan, D.; Edzesi, W.M.; Liu, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Xiao, L. Fine Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis of qSTL3, a Stigma Length-Conditioning Locus in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Liu, E.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Breria, C.M.; Hong, D. QTL Detection and Elite Alleles Mining for Stigma Traits in Oryza sativa by Association Mapping. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryo, I.; Takafumi, W.; Ryo, N.; Pham, T.; Takashige, I. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci Controlling Floral Morphology of Rice Using a Backcross Population between Common Cultivated Rice, Oryza sativa and Asian Wild Rice, O. rufipogon. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 734–744. [Google Scholar]

- Khumto, S.; Pusadee, T.; Olsen, K.M.; Jamjod, S. Genetic relationships between anther and stigma traits revealed by QTL analysis in two rice advanced-generation backcross populations. Euphytica 2018, 214, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalada, G.; Marathi, B.; Vinarao, R.; Kim, S.-R.; Diocton, R.; Ramos, J.; Jena, K.K. QTL Mapping of a Novel Genomic Region Associated with High Out-Crossing Rate Derived from Oryza longistaminata and Development of New CMS Lines in Rice, O. sativa L. Rice 2021, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Gou, Y.; Heng, Y.; Ding, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, X.; Liang, C.; Wu, C.; Wang, H. Targeted manipulation of grain shape genes effectively improves outcrossing rate and hybrid seed production in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, J.; Gu, S.; Wan, X.; Gao, H.; Guo, T.; Su, N.; Lei, C.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Guo, X. Isolation and initial characterization of GW5, a major QTL associated with rice grain width and weight. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Huang, W.; Shi, M.; Zhu, M.; Lin, H. A QTL for rice grain width and weight encodes a previously unknown RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, E.; Fang, B.; Liu, Q.; She, D.; Dong, Z.; Fan, Z. SYL3-k increases style length and yield of F1 seeds via enhancement of endogenous GA4 content in Oryza sativa L. pistils. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yin, X.; Li, S.; Peng, Y.; Yan, X.; Chen, C.; Hassan, B.; Zhou, S.; Pu, M.; Zhao, J. miR167d-ARFs Module Regulates Flower Opening and Stigma Size in Rice. Rice 2022, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Fu, Q.; Liu, G.; Yu, X.; Luo, L.J. Improvement of Rice CMS Line Huhan 1A with Drought Tolerance and Water Saving in Stigma Exsertion Rate. Hybrid Rice 2016, 31, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Ma, Z.; Sun, L.; Su, J.; Wang, S. Investigation of Characters Related to Stigma Exserted Rate in Rice and Establishment of Male Sterile Line with High Stigma Exposure. Tianjin Agric. Sci. 2017, 23, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, M.; Nair, S.; Bhagwat, A.; Krishna, T.; Yano, M.; Bhatia, C.; Sasaki, T. Genome mapping, molecular markers and marker-assisted selection in crop plants. Mol. Breed. 1997, 3, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, D.; Fu, H. Improving the Percentage of Exerted Stigma in CMS Lines of Japonica Hybrid Rice by Molecular Marker-assisted Selection. Biotechnol Bull. 2016, 32, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

| Source of mapping population | Population | chromosomes | QTLs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aijiao Nante/P16 | F2 | Chr. 6 | es-1 | [35] |

| Dongxiang/Guichao2 | BC1 | Chr. 5, 8 | qPEST-5, 8 | [36] |

| Pei- kuh/W1944 | RIL | Chr. 5, 10 | qRES-5, 10 | [18] |

| Zaiyeqing8/ Jingxi17 | DH | Chr. 2, 3 | qPES-2, 3 | [37] |

| Asominori/IR24 | RIL | Chr. 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 12 | qES-3, 4 | [38] |

| Zhenshan97B/IRAT109 | RIL | Chr. 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12 | qPSES-1, 2, 5, 10, 12, qPDES-1a, 1b, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, qPES-1a, 1b, 2, 5, 9, 12 | [39] |

| Nipponbare/Kasalath | BIL | Chr. 3, 4, 5 | qPES-3, 4, 5 | [40] |

| Hoshinohikari / IR24 | F2 | Chr. 3 | qES3 | [21] |

| 90 accessions | AMP | Chr. 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 | qSSE-1, 6, 9, 10, qDSE-1, 5, 7, 8, 11, qPES-5, 7, 8, 9, 10 | [20] |

| Huhan1B/Ⅱ-32B | F2 | Chr. 3, 4, 7, 9 | qPSES-3, 7, 9, qPDES-3, 9, qPES-3, 4, 7, 9 | [41] |

| Nuo5/YouⅠB | F2 | Chr. 2, 5, 8 | qPES-2, 5, 8, qPES-2, 5, 8 | [42] |

| 50S/LianB | F2 | Chr. 3, 9, 12 | qSPES3, qPES-3, 9, 12 | [43] |

| T821B/G46B | F2 | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 7, 9 | qPES-1, 3, 7, 9, qPDES-2, 9, qPSES-1-1, 1-2, 9 | [44] |

| 60B/Liaojing9 | F2 | Chr. 1, 2, 5, 8, 9 | qPGCS-1, 8, qPGCD-8, 9, qPGCES-2,8 | [45] |

| II-32B/G46B | F2 | Chr. 1, 2, 5, 8 | qPES1, 2, 5, 8 | [46] |

| IR24/Asominori | Chr. 3 | GS3 | [47] | |

| Yuezaoxian6/II-32B | RIL | Chr. 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9 | qPDES-1, 3, 6, 7-1, 7-2, 9-1, 9-2, 9-3, qPSES-1, 5, 6, 7, 9-1, 9-2, 9-3 | [48] |

| ZX/CX29B | RIL | Chr. 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12 | qDSE-1, 6a, 6b, 10, qSSE-1, 3, 6a, 6b, 7, 9, 12 | [49] |

| Zhenshan97B/9311 | BIL | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9 | qSSE-1, 5, 9, qDSE-1, 3, 5, 7, 8, qTSE-1, 2, 3a, 3b, 5a, 5b, 7, 8, 9 | [50] |

| HuhanlB/K17B | F2 | Chr. 5, 6, 7 | qPSES-5, qPDES-5, 6, 7, qPES-6 | [51] |

| XieqingzaoB / Zhonghui9308 | RIL | Chr. 1, 6, 10, 11 | qSSE-6, 11, qDSE-1a, 1b, 10, 11, qTSE-1, 11 | [52] |

| 217 CMS line | AMP | Chr. 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12 | qDSE-5, 8, 10, 11, qTSE-3.1, 3.2, 6.1, 6.2, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 11, 12 | [53] |

| XieqingzaoB / Zhonghui9309 | NIL | Chr. 11 | qSSE11, qDSE11, qTSE11 | [54] |

| XieqingzaoB / Zhonghui9308 | CSSL | Chr. 5, 6, 10, 11 | qSSE-5, 10, 11, qDSE-10, 11, qTSE-5, 6, 10, 11 | [55] |

| DaS/D50 | F2 | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 12 | qPSES-1, 2, 3.1, 3.2, 4, 12, qPDES-1, 2.1, 2.2, 4, 6.1, 6.2, 12, qPES-2.1, 2.2, 3, 4, 6.1, 6.2, 7, 12 | [56] |

| 533 accessions | AMP | Chr. 2, 3, 5, 8, 9 | qSSE-3, 5, 9, qDSE-5, 8, qTSE-2, 3, 5 | [57] |

| 115S/93S | F2 | Chr. 10 | qLESR10 | [58] |

| Gui 2136S/Nipponbare | F2 | Chr. 3 | qPES-3, qPDES-3, qPES-3 | [59] |

| XieqingzaoB/Zhonghui9308 | CSSL | Chr. 7 | qSSE7, qDSE7, qTSE7 | [60] |

| Akidawara/W0120 | F2 | Chr. 3, 8 | qSER-3, 8 | [61] |

| Huhan1B/II-32B | NIL | Chr. 7 | qSER-7 | [62] |

| ZS616/DS552 | F3 | Chr. 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11 | qSER-3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 5.1, 6.1, 8.1, 11.1 | [63] |

| 58B/Nipponbare | F2 | Chr.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12 | qSPES-1, 2, 3, 4, 10, qDPES-1, 2, 5, 8, qPES-2, 7, 8, 12 | [64] |

| IRGC104387 | SSSL | Chr. 1, 3, 5, 9, 10 | qSER-1a, 1b, 3a, 3b, 5, 9, 10 | [65] |

| HJX74/O. rufipogon | SSSL | Chr. 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 | qSERb3-1, 5-1, 6-1, 8-1, 12-1, qSERm5-1, 6-1, 8-1, 10-1 | [66] |

| Xiushui79/C Bao | RIL | Chr. 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12 | qPES-1, 6.1, 6.2, 8, 9, 10, 12.1, 12.2 | [67] |

| IR66897B | SSSL | Chr. 2, 3 | qSER-2a, 2b, 3a, 3b | [68] |

| 1892S/Yangdao6-xuan | RIL | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 | qSSE-1, 2-1, 2-2, 4, 5, 7, 8, qDSE-1, 3, 4, 7, qTSE-1, 2, 3, 4, 7 | [69] |

| DaS/D50 | NIL | Chr. 4 | qSE4 | [70] |

| Zhenshan 97B/IRAT109 | RIL | Chr. 1, 2, 8 | qSSE-1, 2, 8, qDSE-1, 8, qTSE-1, 2, 8 | [71] |

| O. glaberrima | SSSL | Chr. 1, 3, 5, 8, 12 | qSER-1a, 1b, 3, 5, 8a, 8b, 12 | [72] |

| HJX74 | SSSL | Chr. 3 | qSER3a-sat | [73] |

| 02428/ZH464 | F2 | Chr. 2, 4 | qTSE-2, 4 | [74] |

| SG22/HJX74 | s-SSSL | Chr. 1 | qSERg-1b | [75] |

| Source of mapping population | Population | chromosomes | QTLs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pei-kuh/W1944 | RIL | Chr. 4, 6, 12 | qSTL-4, 6, qSTB-4, 12, qSYL-6 | [18] |

| 90 accessions | AMP | Chr. 3, 10 | qSTL-3, 10 | [20] |

| T821B/G46B | F2 | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 7, 9 | qSTB-6, 12, qSTL-3, 6, 7, 9-1, 9-2, qSYL-3, 6 | [44] |

| Milyang23/Akihikari | RIL | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, 12 | qSTL-1, 3, 10, 12, qSTB-1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12, qSYL-1, 4, 7 | [77] |

| Asominori/IR24 | RIL | Chr. 3, 4, 5, 7, 12 | qSTL-3-1, 3-2, 7, 12, qSTB-3, 5, 7, qSYL-3, 4 | [77] |

| Nipponbare/Kasalath | BIL | Chr. 2, 3, 7 | qSTL-2, 3, qSTB7, | [77] |

| IR64/Azucena | DHL | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 5, 9 | qSTL-3, 5, 9, qSTB-3, 5, 9, qSYL-1, 2, 3 | [77] |

| IR64 · Kinandang Patong | F2 | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 5 | qSTL-3-1, 3-2, 3-3, 5-1, 5-2, qSTB-2, 3, qSYL-1, 3 | [77] |

| Nipponbare/Kasalath | CSSL | Chr. 3 | qSTL3 | [78] |

| 48 accessions | AMP | Chr. 3, 4, 7, 10 | qSTL-3-1, 3-2, 3-3, qSYL10, qSSL-3, 7 | [22] |

| 227 accessions | AMP | Chr. 1, 2, 4, 6 | qSTL-1, 2-1, 2-2, 4, 6-1, 6-2 | [79] |

| Nipponbare/W630 | BRIL | Chr. 7, 8 | qSGL-7, 8, qSYL8 | [80] |

| 533 accessions | AMP | Chr. 3, 4, 8 | qSTL8, qSYL-3, 4 | [57] |

| SPR1/O. rufipogon Griff | BIL | Chr. 3, 8, 10 | qSTL-3A, 3S, 8A, 8S, 10S, qSTW-3S, 8S, 10S, qSTYL-8A, 10S | [81] |

| Xiushui79/C Bao | RIL | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 | qSTL-2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, qTSSL-1, 2.1, 2.2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 | [67] |

| IR64/OL | BIL | Chr. 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 11 | qSTGL-2-1, 5-1, 8, 11-1, 11-2, qSTYL-1-1, 5-2, 8-1, qSTGB-1-1, 3-1 | [82] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).