1. Introduction

The use of eco-friendly materials has become widespread over the past decade. Despite this, there are few studies analyzing composite materials service life, as well as their environmental impact [

1]. Taking into account the above, the implementation of polymer-reinforced carbon fiber composites has increased in structural applications thanks to their excellent mechanical properties. The production of this is approximately 100,000 tons per year, on which an increase of 10% to 20% is expected [

2]. On the other hand, the excessive use of these materials generates waste during their production, as well as at the end of their useful life, which, due to their chemical composition, are not biodegradable [

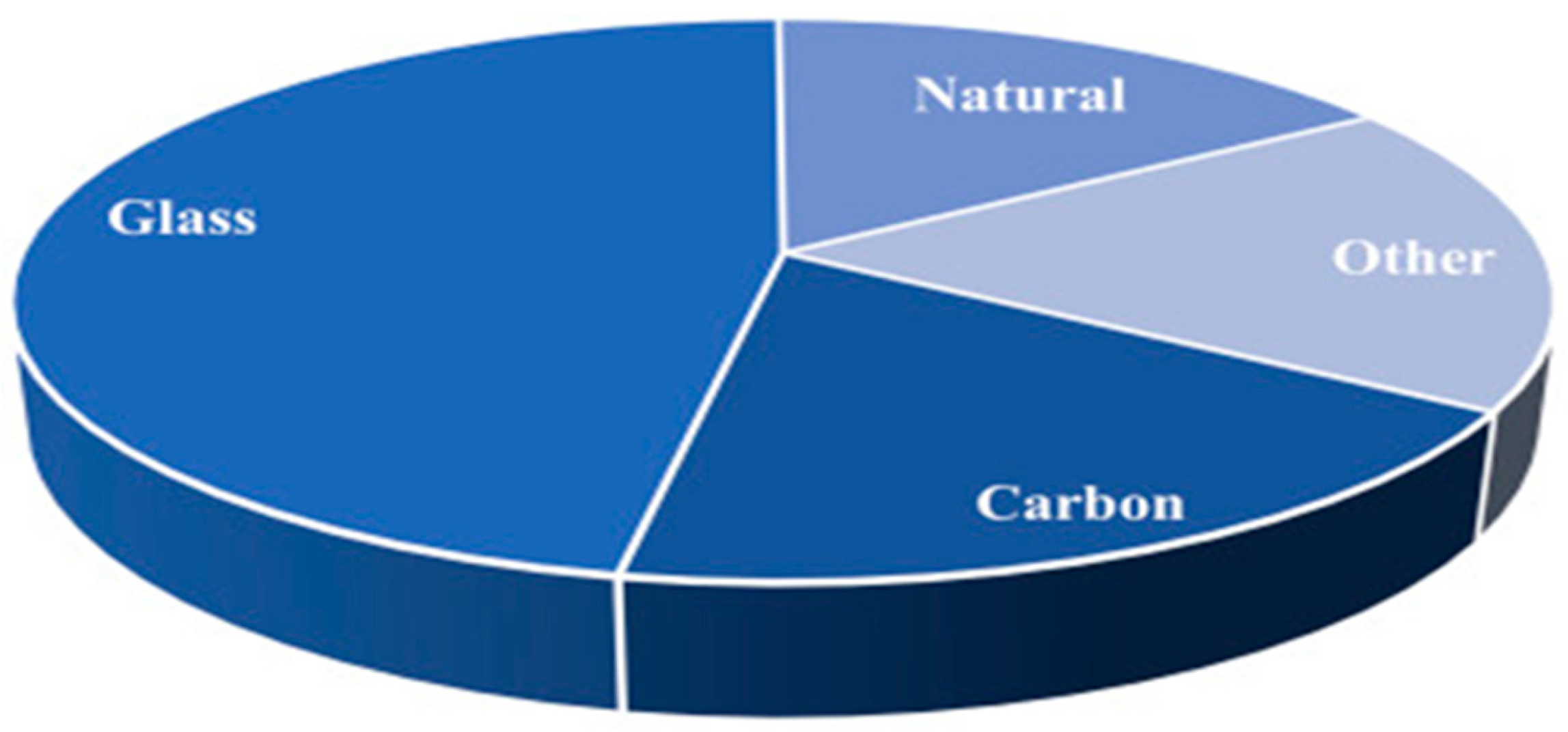

3]. Now, regarding the percentage of fibers most used worldwide in 2020, fiberglass and carbon stand out among the most used [

1], as can be seen in

Figure 1.

These synthetic fiber compounds end up in landfills because there is no proper way to dispose of them, which causes a huge problem for the population. Some reports mentioned that less than 10% of these materials are recycled [

4], which means that a large part ends up in landfills, the number of which is increasing daily [

5].

As a response to this situation, to increase recycling is proposed. In this regard, it could be said that the environmental policy for this issue is increasingly strict and it is currently mandatory to find industrial processes for the reuse of these polymeric materials [

6]. To this extent, recycling methods for composite materials are proposed, which have been developed in three categories: mechanical, thermal and chemical [

7]. These categories are described below.

Mechanical recycling: This is a process that grinds waste compounds down to the smallest particles. This can be done by crushing or grinding, with the aim of reusing them as filler material [

8]. It is important to mention that this process is not widely used in industrial terms due to its low added value [

9]. However, it is possible to work and separate portions of the original parts, using low electric current consumption [

10].

Thermal recycling: There are two types of this process: pyrolysis, which involves exposing the material to be recycled to 500 ˚C; however, this can damage the fiber by retaining some residues. It is also not always economical, so it depends on the technology used [

7].

On the other hand, there is solvolysis: through this type, clean and intact fibres are obtained, and the recovered resin can be reused [

11]. This is achieved thanks to the increase in temperature (which does not exceed the previous one), to the pressurized environment; so that these conditions allow the resin to be collected. However, a major problem with this is that a large amount of energy is used [

12,

13].

Chemical recycling: is a process carried out by means of solvolysis; however, through this process the thermosetting, epoxy and polyester matrices are damaged by using different solvents. Sometimes organic catalysts are added, all of this can be carried out at various temperatures; generally, lower than in pyrolysis and at higher pressures [

14]. In addition, the definition of solvolysis is a process that uses a reactive solvent to break the covalent bonds of a polymeric matrix. [

15]. Consequently, this solvent is mixed with the material to be recycled, causing the fibers to detach from the polymer matrix [

10].

Given the available information, this review aimed to analyze recycling techniques for polymer matrix composites from the three main groups and some variants of these, such as hybrid processes. The strengths, limitations and different parameters were analyzed; for example, the how, the ecological impact, energy consumption, reuse and cost, in order to determine an overview of the processes and trends, or areas of opportunity that have not been analyzed for these applications.

2. Method

To carry out the review, the reference framework of PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) and the prisma flowchart [

16].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The following eligibility criteria were defined for the selection of literature that was part of the extraction phase:

The types of articles used were the following: research articles and bibliographic reviews.

Publications from 2022 to date 2023.

All articles used are written in English and Spanish.

Articles must discuss or contain information about the methods used to recycle composite materials, such as mechanical, thermal, chemical.

2.2. Data Extraction

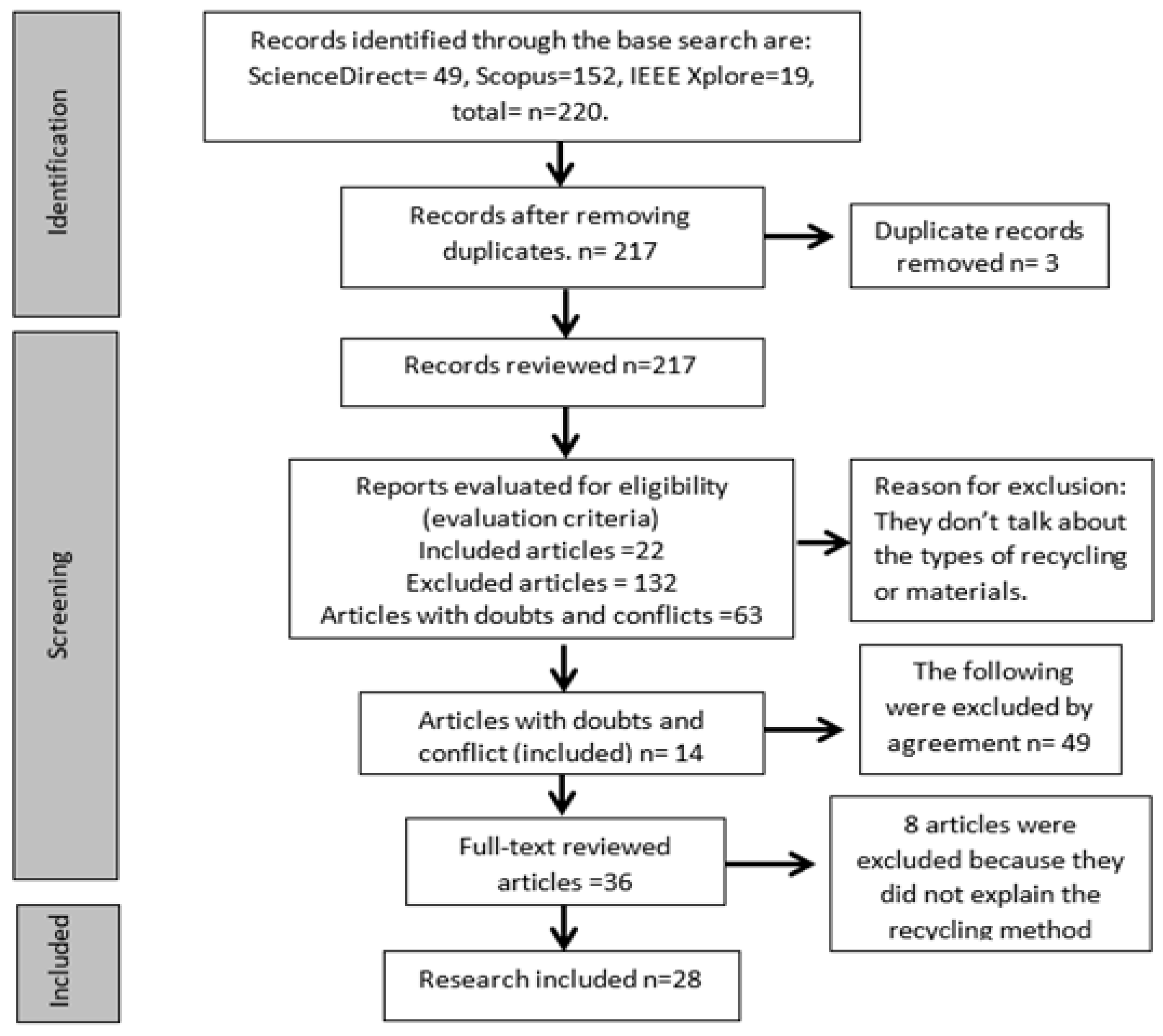

First, searches were carried out in specialized databases for data extraction. Next, citations were collected and, finally, the resulting articles were analyzed. The results obtained were the numbers reported in

Figure 2. The PRISMA reference framework was used to report the results.

Figure 2 shows the process carried out, which includes the results obtained from the literature search in the databases: SCOPUS (152), ScienceDirect (49) and IEEE Xplore (19). The entire procedure was carried out on the Rayyan platform through 220 articles. In a first run, 3 duplicates were eliminated from the remaining 217 analyzed; likewise, 132 articles were excluded for not meeting the established criteria. The rest of the articles were divided into included (22), conflict (18) and doubt (45). From the articles in conflict and doubt, were included 14 and excluded 49; as a result, 36 articles were registered to read in full text, of these 8 articles were reviewed and excluded, which mentioned some type of recycling, but did not explain the process used. Finally, only 28 articles were included.

2.3. Characteristics of the Studies

The articles that were included at the end of the review were 28, since they describe and explain one or several recycling processes with composite materials. The inclusion criteria for these articles that use the mechanical recycling process (n = 7), chemical recycling (n = 8), thermal recycling (n = 6) and hybrid recycling (n = 4), of which some articles are repeated in more than one process (n = 3).

At a global level, the findings were distributed as follows: the American continent (n = 3), Asia (n = 18), Europe (n = 7). In articles that did not report a country of origin or in which several researchers participated, the country of origin of the principal investigator was taken. It was observed that the majority of published articles that deal with these topics are found in Asia, although there is a large part of the studies that are collaborating with researchers from different continents.

2.4. Data analysis and Presentation

The objective of this exercise was to collect articles that met the inclusion criteria mentioned above, as well as to learn about the current situation regarding recycling processes for composite materials; also, to inquire about the countries or regions where these works are published and where they were developed. Likewise, the reviewed articles that reported information on composite materials were tracked, as well as information on the three types of recycling based on an ecological, economic dimension and properties or reuse of these.

2.4.1. Mechanical Recycling Process

Seven recycling articles were accepted for mechanical recycling and are described below. The results show that mechanical processes are based on machining (shredding); there are also other procedures such as high voltage separation, which are mainly applied to fiberglass, carbon or kevlar composites [

6]. Typically, most short fibers are obtained by a mechanical method [

1]. Similarly, the most common method for recycling is crushing [

8,

17]; however, this has a disadvantage: the reinforcing polymer matrix is shredded together with the material [

18]. For the production of carbon fiber, between 183 and 286

MJ of energy is required to produce 1 kg of virgin carbon fiber [

19]; therefore, to produce 1 kg of recycled fiber, 0.27

MJ of energy is consumed by mechanical processes, with which fibers of around 5 to 9 mm in length can be obtained [

20].

Other authors perform simulations by grinding materials. This is done through tests of results to compare the behavior with the original [

21]. For this purpose, recycled granulated material of carbon fiber and ABS composites was used, through direct additives, which caused a certain decrease in the mechanical properties of the pieces obtained, because it partially reduces the total fiber content, that is, it converts a percentage of the fibers into fine powders. Consequently, no degradation in the lengths of the fibers was observed in the printed pieces [

22]. In this regard, it was found that recycling by machining carbon fiber composite parts at the end of their useful life, by means of peripheral milling, generates economic and environmental benefits. Likewise, it was shown that, when using a three-edged HSS cutting tool, the cutting speed was varied. However, the chips generated were of diameters greater than 0.3 mm. From this material and epoxy resin, test tubes were made, which were subjected to mechanical tests that resulted in an increase in their rigidity (varying between 2.2 to 5.8 GPa) and resistance under bending load (varying between 77 to 111 MPa) respectively [

23].

In this order of ideas, a novel mechanical process consists of recovering layers of a laminate of materials at room temperature. This is obtained through the following steps: generation of a notch as a crack initiation zone, controlled initiation of a crack by means of an impact load; also, the propagation of the crack by means of a dynamic load similar to a shell. After, the successful separation of the layers of a laminate was carried out, and mechanical tests were applied to the recovered material, which gave the possibility of preserving its properties [

24]. Afterwards, the mechanical recycling process was simulated in the laboratory environment, where the degradation of the mechanical properties of various compounds due to the crushing and remanufacturing of these was studied. On the other hand, the use in external applications such as humidity and temperature fluctuations, which can affect the performance of these, was analyzed [

25]. In this sense, the main objective of this work was to determine the feasibility of using polymer-reinforced fiberglass powders to replace other materials. It should be mentioned that this process was carried out under laboratory conditions, and the fiberglass powders used were obtained from a

pultrusion manufacturer, which implies a mechanical method for obtaining them [

26].

2.4.2. Chemical Recycling Process

Eight articles were found that reported information on chemical recycling processes. All of these investigations were carried out in controlled laboratory environments or with specialized equipment; that is, it was not reported that they would be carried out in industry. However, there were authors who mentioned that these processes could be used in industry in the future.

As far as chemical recycling research is concerned, it was found that it uses solvents to degrade the resin, as well as a varied range of temperatures, pressures and catalysts, which use these techniques to recycle different compounds. These are used for carbon fibers, which reduces traction by 20% and 60% for fiberglass [

1]. Solvolysis is one of the most widely used processes for recycling. This process, like the previous ones, is selected based on the material to be recycled and the uses for reuse. Therefore, recycling is moving in the right direction; however, the disadvantage they present lies in the market for recycled products [

27].

The following investigation analyzed the feasibility of recycling fiberglass composites with epoxy matrix by solvolysis in ethanol. This process is successfully completed in 4 hours, through the use of a pure solvent containing 10% water at a temperature of 280 °C, when the solvent reaches the supercritical state and the process time increases to 10 hours at a temperature of 250 °C. In this regard, it is found that the process time can vary depending on the chemicals used. Additionally, the resulting fibers can be used in decorative or structural products made of polymeric composite materials [

18]. On the other hand, solvolysis was used to recover clean and intact fibers and reuse the resin. This was carried out at a temperature of 100–190 °C, in a time of 60–180 min, under a pressure of 30–60 bar in an inert atmosphere of inert N

2 at a high-pressure, high-temperature vessel with a chemical capacity of 500 ml, containing the catalyst, ethylene glycol and 1- methyl -2- pyrrolidine in a molar ratio of 1:1. For this purpose, 1 g of sample and 20 ml of solution were used; after each test, the material was filtered to remove fiber residues. Additionally, the liquid sample was analyzed by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and the solid residue from the filter was washed, dried and weighed. After weighing, the fiber was burned to analyze the ash content [

7].

Pyrolysis process for the recovery of thermoplastic parts can be carried out by dissolving resin. The glass fibers recovered by this method retain the same tensile properties as the original fibers, which reduces hardness by 12%. For this purpose, the research was carried out with mechanical recycling of truck battery caps, which were mixed with polypropylene and short and long glass fibers. These materials were then characterized through diameter measurement and combustion tests [

28]. Afterwards, the matrix is degraded by oxidation, by adding a radical initiator, in order to accelerate the process [

29].

The resin is then dissolved with a combination of potassium hydroxide and monoethanol amine. The fiber is recovered and the resulting solution can be distilled to recover the original polymer with some degradation [

30]. The recycling process is then described and reused in glass fiber separators in batteries [

31]. Sulfuric acid is also used to dissolve the matrix in the recovery of the fibers. This consequently allows the recovery of a polymer that can be used in other applications [

32]. It is then depolymerized and chemically degraded to recover fibers, as well as to maintain their integrity [

33]. Finally, a low-temperature chemical process (<150 °C) is analyzed, which serves to recover epoxy matrix carbon fibers [

20].

2.4.3. Thermal Recycling Process

For this type of process, a total of six investigations were found that reported information on the subject. The first investigation presented thermal recycling by microwave-assisted fluidized bed pyrolysis. In this way, fibers and fillers are recovered, which varies with the monomers that could be used to produce resins. For this, the temperatures used range between 450 °C and 700 °C, with the highest values being for thermoplastic and epoxy resins [

1]. The research indicated that they use a fluidized bed recycling process, which reduces a percentage of the properties of the fibers obtained. On the other hand, mixtures of fibers with binding agents were made to obtain paper strips with recycled fibers (pre-impregnated). With this, laminates were made to then perform bending tests [

3]. In this regard, it was determined that thermolysis is one of the most common methods used for recycling; therefore, this recycling method may be the most suitable for composites made of fiberglass and carbon fiber, thanks to the low cost of fiberglass and because this method damages its mechanical properties. They are usually used for important components of the resin in order to manufacture a new one [

34].

Similarly, this research analyzed the recycling of wind turbine blades by means of pyrolysis, with the objective of thermally degrading the polymeric matrix at high temperature and without oxygen [

35]. To this end, the fibers obtained are covered with carbon, which are mixed with liquids from the process; for the glass fibers, some mechanical properties are affected by the high temperatures of 450 °C [

10]. In this sense, it is observed that the oxidative liquefaction method looks promising for the recycling of glass fibers. It is found that, in the process, the pressure does not present a relevant effect, those that are relevant are the temperature, time, oxidant concentration and liquid residues. Regarding the temperature, the lowest value was 250 °C and at 300 °C, carbonization is generated, whose properties affect the process. Added to this is the increase in electrical consumption [

36].

In this research, the central design process for high-temperature pyrolysis processes for carbon fibers was adopted. In that regard, the experimental results revealed the influence of recycled carbon fiber resin and oxidation degree affecting tensile properties. The process parameters were further optimized for high-temperature pyrolysis recycling for carbon fiber composites [

37]. Additionally, pyrolysis of fibers and epoxy resin for recycling end-of-life wind turbine scrap was explored, as well as the characteristics of fibers as reinforcing components in flexible composites [

38]. Considering this information, the pyrolysis method was used to recover carbon fibers from bicycle waste, whose experimentation was conducted in a laboratory environment [

39].

2.4.4. Hybrid Recycling Process

For this type of recycling process, although it was not contemplated in the review, it was considered due to the analysis of the literature obtained. To this extent, four articles were accepted, of which they report the fusion of two or more recycling processes. Based on this, the classification was made. It is important to mention that these investigations were carried out in laboratory environments and equipment.

Solvothermal method was analyzed to degrade ester matrix composite materials. carbon fiber reinforced vinyl. Also, the degradation was carried out in a Teflon-lined autoclave at a temperature of 160 ℃ and 240 ℃ for a time of 60 min. to 180 min. For this purpose, it was used isopropanol and acetone as solvents; as a result, a degradation rate of up to was obtained 99.96 % [

9]. On the other hand, a thermo-mechanical process was analyzed for the separation of layers of laminates that are then rejoined by means of thermoforming, through thermoplastics between the recovered layers. These laminates are heated in an oven and the layers are separated with rollers [

29]. Likewise, the carbon fibers of the masks are analyzed by carbonization, in an argon atmosphere at a temperature between 1200 and 1400 ° C. Subsequently, the fibers obtained are used in batteries [

32]. Finally, the electrochemical process for the recovery of graphene oxide from carbon fiber reinforced polymers was examined; for this purpose, a NaCl solution was used as an electrolyte, which varied its concentrations, as well as tap water [

40].

2.4.5. Indicators Associated with the Methods

It was found that some of the reviewed articles reported important points, which can be of great importance in determining which recycling process has the best added value. Currently, epoxy resin fiber materials have greater value, in terms of technical and innovation in the market, since the use of these materials has increased [

38].

Regarding this, it was identified that some researchers, in agreement with the field of industry, are analyzing the development of recycling systems at an industrial level with the aim of improving the efficiency in the use of resources, reducing their consumption and the generation of waste, as a result of the environmental impact [

41].

The articles make a brief comparison regarding energy consumption, as well as the cost that this would generate. In this regard, one of these articles addressed the simplicity of the mechanical process, as well as the reduced energy consumption compared to other types of recycling, coupled with the attention to efficient management of energy and resources that is increasing among scientists and authorities around the world [

1]. In this order of ideas, energy consumption in composite materials recycling processes is an important factor to determine the economic viability of the process. For this reason, the entire process must be characterized to determine it is applicable industrially [

10]. From the information reviewed, the following table was extracted with data on the electrical consumption reported for each type of recycling process.

Table 1 shows the energy consumption for the different composite recycling processes. It was observed that the values of energy consumption are low for mechanical recycling [

8], because the energy used is less than that incorporated in the original processes [

1]. More energy is needed for chemical and thermal processes due to the greater complexity of the process [

42].

There are researchers who point out that the chemical process, carried out at low temperatures, has positive results in energy consumption compared to other variants of the same process [

43].

It was determined that the material obtained from the different pyrolysis recycling processes has better mechanical properties due to the resin remain impregnated in the fibers [

37,

38]. In addition, it was mentioned that for mechanical recycling the generated material is limited, because there are still no defined applications for it, since the mechanical properties are affected by the fibers that are short [

22,

23].

3. Discussion

This research was carried out with the aim of obtaining information and an overview of the current state of recycling processes, in order to determine if there is any trend in the research. The articles reviewed were refined from their search, in a period that included the years 2022 and 2023. Using the results obtained, a bibliography mapping was developed, in coordination with the PRISMA- Scr guide [

16], and with the support of the Rayyan platform [

44]. A total of 28 articles that met the inclusion criteria were accepted, which reported information on recycling processes. The following results were obtained from the above: 25% mechanical, 29% chemical, 21% thermal, 14% hybrid, and finally, 11% provided information on two or more types of recycling. 100% of the reviewed articles were written in English.

From the articles reviewed with controlled laboratory equipment and spaces [

20,

21,

24,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

38,

39,

40,

43,

45,

46], it was found that, although there has been significant progress in the recycling issue, there is still a lack of more information that standardizes a process and that can be applied in the industry, considering environmental, economic and legal conditions [

1,

9,

10,

18,

27]. In effect, this indicates that these are processes that are still in the early stages of the development of these technologies.

Some investigations reported hybrid methods that used two different types of technologies. For example, these investigations mixed a mechanical process with a thermal process [

29,

40]. Other researchers reported the mixed of chemical and thermal process [

32]. On the other hand, there was a lack of bibliography regarding economic and energy analysis of recycling processes, which would allow demonstrating the environmental impact of the products, as well as their economic benefit from the material obtained from recycling [

38].

From the reviewed papers, mechanical recycling is who call more attention because it is a fast and economical method. Although a better application for the obtained material needs to be developed since it is only used as filling material [

23].

In chemical recycling method, it was found that the use of sulfuric acid to dissolve the matrix allows the recovery of fibers with properties similar to the original ones, besides recovers the polymer used as matrix that can be reused in other applications achieving no waste generation, the drawback is that this process is in the laboratory phase for which specialized and expensive equipment is needed [

33].

Fluidized bed method for recycling carbon fiber materials was used, however affected the original fiber properties. Based on this a mixture of recycled material with original kevlar material was made, interspersing recycled material with a layer of original fiber and using it as a prepreg material, for possible lightweight structural applications and with emphasis on finding a balance between mechanical damping and stiffness performance [

3].

On the hybrid recycling side, it was found this one uses a hybrid process of two conventional recycling processes, this process is carried out in a first part by heating the laminates to later proceed to peel off layer by layer of the laminate with the help of a machine, the material obtained is reused using layers of plastic between each layer of recycled material, it is heated and subsequently pressed, in order to have a good union of all the materials, which have good behavior in bending tests compared to original fiber laminates [

29].

4. Conclusions

An overview of the different recycling processes for composite materials was obtained. Some processes reported to have very high efficiencies in recycling and reusing materials. However, these methods use highly specialized laboratory equipment or generate a large amount of waste, which translates into high processing costs.

For this reason, it is feasible to investigate sustainable applications for the material obtained from mechanical recycling, since this is the simplest, most economical and environmentally friendly process compared to the other processes analyzed. However, the material obtained does not have a good price on the market due to the limitations of its application.

In general, recycling processes for composite materials is a topic that is under constant research, due to technological advances and the increase in their use. In addition, the increasingly strict changes in environmental policies in the world make it necessary to thoroughly investigate recycling processes and seek new applications for the materials generated, so that they contribute to reuse and thus generate a circular approach for said materials.

It is recommended to investigate the option of reducing costs in terms of the machines or processes used, to make the use of one or another process more attractive due to its low cost. It was determined that all the processes have their benefits, only the equipment or processes are very sophisticated or expensive, the most user-friendly is the mechanical one, since you can use different machines and move large volumes of composite materials, it only remains to determine or carry out a more in-depth investigation regarding the application that can be given to the material resulting from that process, since a disadvantage of this process is the applicability of the resulting material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GJ-G. and IM-M., methodology, ES-M. and M. M-R.; investigation, ES-M and Á. G.-Á.; writing—original draft preparation, ES-M. and IM-M.; writing—review and editing, GJ-G. and Á.G.-Á. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sector.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgements

Authors are greatly grateful to the Universidad Autónoma de Baja, California for facilitating the access and use of their facilities and equipment to carry out this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- V. Lunetto, M. Galati, L. Settineri, and L. Iuliano, “Sustainability in the manufacturing of composite materials: A literature review and directions for future research,” Jan. 06, 2023, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pickering, Z. Liu, T. A. Turner, and K. H. Wong, “Applications for carbon fibre recovered from composites,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, B. Madsen, A. Biel, Y. Kusano, L. Mishnaevsky, H. Lilholt, L. P. Mikkelsen, and B. F. Sorensen, Eds., Institute of Physics Publishing, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Yaw Attahu, C. Ket Thein, K. H. Wong, and J. Yang, “Enhanced damping and stiffness trade-off of composite laminates interleaved with recycled carbon fiber and short virgin aramid fiber non-woven mats,” Compos Struct, vol. 297, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, and K. L. Law, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made,” Sci Adv, vol. 3, no. 7, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Parameswaranpillai et al., “Turning waste plant fibers into advanced plant fiber reinforced polymer composites: A comprehensive review,” Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 10, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Oliveux, L. O. Dandy, and G. A. Leeke, “Current status of recycling of fibre reinforced polymers: Review of technologies, reuse and resulting properties,” Prog Mater Sci, vol. 72, pp. 61–99, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Muzyka, S. Sobek, A. Korytkowska-Wałach, Ł. Drewniak, and M. Sajdak, “Recycling of both resin and fibre from wind turbine blade waste via small molecule-assisted dissolution,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Howarth, S. S. R. Mareddy, and P. T. Mativenga, “Energy intensity and environmental analysis of mechanical recycling of carbon fibre composite,” J Clean Prod, vol. 81, pp. 46–50, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang, Z. Deng, C. Dong, J. Fan, and Y. Ren, “A closed-loop recycling process for carbon fiber reinforced vinyl ester resin composite,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 446, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Mumtaz, S. Sobek, M. Sajdak, R. Muzyka, and S. Werle, “An experimental investigation and process optimization of the oxidative liquefaction process as the recycling method of the end-of-life wind turbine blades,” Renew Energy, vol. 211, pp. 269–278, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Hong, F. Part, and B. Nowack, “Prospective Dynamic and Probabilistic Material Flow Analysis of Graphene-Based Materials in Europe from 2004 to 2030,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 56, no. 19, pp. 13798–13809, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Vollmer et al., “Beyond Mechanical Recycling: Giving New Life to Plastic Waste,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition, vol. 59, no. 36, pp. 15402–15423, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

-

P. Liu, F. Meng, and C. Y. Barlow, “Wind turbine blade end-of-life options: An economic comparison,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 180, p. 106202, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Gałko and M. Sajdak, “Trends for the Thermal Degradation of Polymeric Materials: Analysis of Available Techniques, Issues, and Opportunities,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Cousins, Y. Suzuki, R. E. Murray, J. R. Samaniuk, and A. P. Stebner, “Recycling glass fiber thermoplastic composites from wind turbine blades,” J Clean Prod, vol. 209, pp. 1252–1263, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Tricco et al., “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation,” Ann Intern Med, vol. 169, no. 7, pp. 467–473, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

-

M. Pietroluongo, E. Padovano, A. Frache, and C. Badini, “Mechanical recycling of an end-of-life automotive composite component,” Sustainable Materials and Technologies, vol. 23, p. e00143, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Protsenko, A. N. Protsenko, O. G. Shakirova, and V. V. Petrov, “Recycling of Epoxy/Fiberglass Composite Using Supercritical Ethanol with (2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium)2[CuCl4] Complex,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 6, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. van de Werken, M. S. Reese, M. R. Taha, and M. Tehrani, “Investigating the effects of fiber surface treatment and alignment on mechanical properties of recycled carbon fiber composites,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 119, pp. 38–47, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Cheng, L. Guo, L. Zheng, Z. Qian, and S. Su, “A closed-loop recycling process for carbon fiber-reinforced polymer waste using thermally activated oxide semiconductors: Carbon fiber recycling, characterization and life cycle assessment,” Waste Management, vol. 153, pp. 283–292, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Bata, D. Nagy, and Z. Weltsch, “Effect of Recycling on the Mechanical, Thermal and Rheological Properties of Polypropylene/Carbon Nanotube Composites,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 23, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Korey et al., “Recycling polymer composite granulate/regrind using big area additive manufacturing,” Compos B Eng, vol. 256, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Durante, L. Boccarusso, D. De Fazio, A. Formisano, and A. Langella, “Investigation on the Mechanical Recycling of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers by Peripheral Down-Milling,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 4, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Imbert, P. Hahn, M. Jung, F. Balle, and M. May, “Mechanical laminae separation at room temperature as a high-quality recycling process for laminated composites,” Mater Lett, vol. 306, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Tamrakar, R. Couvreur, D. Mielewski, J. W. Gillespie, and A. Kiziltas, “Effects of recycling and hygrothermal environment on mechanical properties of thermoplastic composites,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 207, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, C. Zheng, L. Mo, H. GangaRao, and R. Liang, “Assessment of recycling use of GFRP powder as replacement of fly ash in geopolymer paste and concrete at ambient and high temperatures,” Ceram Int, vol. 48, no. 10, pp. 14076–14090, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Waghmare, S. Shelare, K. Aglawe, and P. Khope, “A mini review on fibre reinforced polymer composites,” Mater Today Proc, vol. 54, pp. 682–689, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Sözen, A. Cevahir, and S. J. Deniz, “Study on Recycling of Waste Glass Fiber Reinforced Polypropylene Composites: Examination of Mechanical and Thermal Properties,” vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 63–76, 2023.

- A. Proietti et al., “Recycling of Carbon Fiber Laminates by Thermo-mechanical Disassembly and Hybrid Panel Compression Molding,” Mater. Plast, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 44–50, 1964. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhao, L. An, C. Li, L. Zhang, J. Jiang, and Y. Li, “Environment-friendly recycling of CFRP composites via gentle solvent system at atmospheric pressure,” Compos Sci Technol, vol. 224, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma et al., “High efficient recycling of glass fiber separator for sodium-ion batteries,” Ceram Int, vol. 49, no. 14, pp. 23598–23604, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gao et al., “Recycling spent masks to fabricate flexible hard carbon anode toward advanced sodium energy storage,” Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, vol. 941, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, P. Liu, J. Yue, H. Huan, G. Bi, and L. Zhang, “Recycling glass fibers from thermoset epoxy composites by in situ oxonium-type polyionic liquid formation and naphthalene-containing superplasticizer synthesis with the degradation solution of the epoxy resin,” Compos B Eng, vol. 254, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Mowade, S. Waghmare, S. Shelare, and C. Tembhurkar, “Mathematical Model for Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient During Solar Drying Process of Green Herbs,” in Computing in Engineering and Technology, B. Iyer, P. S. Deshpande, S. C. Sharma, and U. Shiurkar, Eds., Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 867–877.

- S. Sobek and S. Werle, “Kinetic modelling of waste wood devolatilization during pyrolysis based on thermogravimetric data and solar pyrolysis reactor performance,” Fuel, vol. 261, p. 116459, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Salas et al., “Towards recycling of waste carbon fiber: Strength, morphology and structural features of recovered carbon fibers,” Waste Management, vol. 165, pp. 59–69, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen et al., “Optimisation of recycling process parameters of carbon fibre in epoxy matrix composites,” Compos Struct, vol. 315, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Du et al., “Zero–Waste Recycling of Fiber/Epoxy from Scrap Wind Turbine Blades for Effective Resource Utilization,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 24, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Y. Chin et al., “Studies on Recycling Silane Controllable Recovered Carbon Fiber from Waste CFRP,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 2, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Ling, C. Wu, F. Xing, S. A. Memon, and H. Sun, “Recycling Nanoarchitectonics of Graphene Oxide from Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer by the Electrochemical Method,” Nanomaterials, vol. 12, no. 20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, C. Wang, M. Gao, and C. Liu, “Emergy-based sustainability measurement and evaluation of industrial production systems,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 22375–22387, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Shuaib and P. T. Mativenga, “Energy demand in mechanical recycling of glass fibre reinforced thermoset plastic composites,” J Clean Prod, vol. 120, pp. 198–206, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Yu, Y. Hong, E. Song, H. Kim, I. Choi, and M. Goh, “Advanced oxidative chemical recycling of carbon-fiber reinforced plastic using hydroxyl radicals and accelerated by radical initiators,” Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, vol. 112, pp. 193–200, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. and F. Z. and E. A. Ouzzani Mourad and Hammady, “Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews,” Syst Rev, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 210, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhao et al., “Controlling degradation and recycling of carbon fiber reinforced bismaleimide resin composites via selective cleavage of imide bonds,” Compos B Eng, vol. 231, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Mu, L. An, Z. Hu, and X. Kuang, “Fast and sustainable recycling of epoxy and composites using mixed solvents,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 199, May 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).