Submitted:

28 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

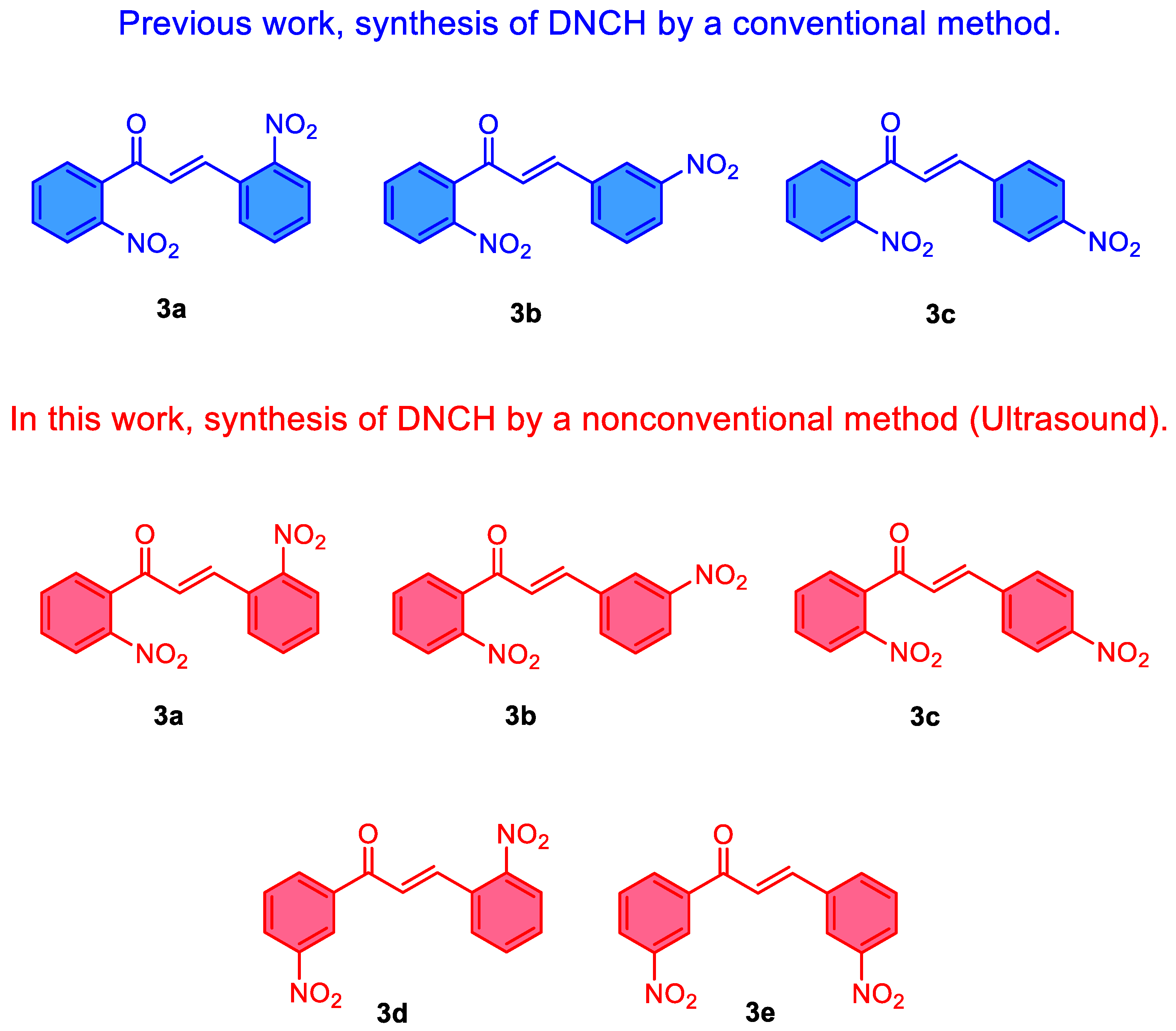

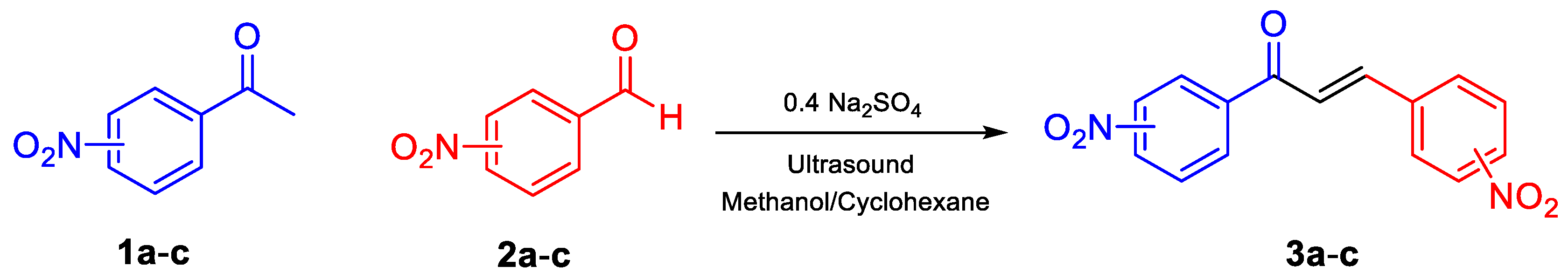

2.2. Procedure for the Synthesis of Dinitrochalcones (DNCH)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campos, K. R.; Coleman, P. J.; Alvarez, J. C.; Dreher, S. D.; Garbaccio, R. M.; Terrett, N. K.; Tillyer, R. D.; Truppo, M. D.; Parmee, E. R. The Importance of Synthetic Chemistry in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Science (80-. ). 2019, 363, eaat0805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, G.; Bhanu, D.; Aruchamy, B.; Ramani, P.; Pandurangan, N.; Bobba, K. N.; Oh, E. J.; Chung, H. Y.; Gangadaran, P.; Ahn, B.-C. Chalcone: A Promising Bioactive Scaffold in Medicinal Chemistry. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narwal, S.; Devi, B.; Dhanda, T.; Kumar, S.; Tahlan, S. Exploring Chalcone Derivatives: Synthesis and Their Therapeutic Potential. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 137554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Quispe, C.; Chamkhi, I.; El Omari, N.; Balahbib, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Bouyahya, A.; Akram, M.; Iqbal, M.; Docea, A. O. Pharmacological Properties of Chalcones: A Review of Preclinical Including Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 592654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalkova, R.; Mirossay, L.; Kello, M.; Mojzisova, G.; Baloghova, J.; Podracka, A.; Mojzis, J. Anticancer Potential of Natural Chalcones: In Vitro and in Vivo Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. S.; Hussein, R. A.; El-Sayed, W. M. Substitution at Phenyl Rings of Chalcone and Schiff Base Moieties Accounts for Their Antiproliferative Activity. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. (Formerly Curr. Med. Chem. Agents) 2019, 19, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, S.; Cardoso-Ortiz, J.; López-Luna, A.; Cuevas-Flores, M. D. R.; Flores De La Torre, J. A. The Diverse Biological Activity of Recently Synthesized Nitro Compounds. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rivera, A.; Aguilar-Mariscal, H.; Romero-Ceronio, N.; Roa-de la Fuente, L. F.; Lobato-García, C. E. Synthesis and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Three Nitro Chalcones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 5519–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, E. Chalcones: Retrospective Synthetic Approaches and Mechanistic Aspects of a Privileged Scaffold. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 2843–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, L.; Rossi, S.; Ibba, R.; Brogi, S.; Calderone, V.; Butini, S.; Campiani, G.; Gemma, S. The Green Chemistry of Chalcones: Valuable Sources of Privileged Core Structures for Drug Discovery. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 988376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, G. P.; Seca, A. M. L.; Barreto, M. do C.; Pinto, D. C. G. A. Chalcone: A Valuable Scaffold Upgrading by Green Methods. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 7467–7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T. J. Ultrasound in Synthetic Organic Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 26, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslick, K. S.; Price, G. J. Applications of Ultrasound to Materials Chemistry. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1999, 29, 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, S. Power Ultrasound and Its Applications: A State-of-the-Art Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 62, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, G.; Cintas, P. Power Ultrasound in Organic Synthesis: Moving Cavitational Chemistry from Academia to Innovative and Large-Scale Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luche, J.-L. Sonochemistry: From Experiment to Theoretical Considerations. Adv. sonochemistry 1993, 3, 85–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cravotto, G.; Cintas, P. Introduction to Sonochemistry: A Historical and Conceptual Overview. Handb. Appl. Ultrasound 2011, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Anchecta, K.; Lee, Y.-D.; Dahlgaard, J. J. A Stepwise ISO-Based TQM Implementation Approach Using ISO 9001: 2015. In Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev.; 2016; 4. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara III, W. B.; Didenko, Y. T.; Suslick, K. S. Sonoluminescence Temperatures during Multi-Bubble Cavitation. Nature 1999, 401, 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, D. J.; Suslick, K. S. Inertially Confined Plasma in an Imploding Bubble. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R. F.; Cravotto, G.; Cintas, P. Organic Sonochemistry: A Chemist’s Timely Perspective on Mechanisms and Reactivity. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 13833–13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmachari, G.; Nayek, N.; Mandal, M.; Bhowmick, A.; Karmakar, I. Ultrasound-Promoted Organic Synthesis-A Recent Update. Curr. Org. Chem. 2021, 25, 1539–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharat, N. N.; Rathod, V. K. Ultrasound-Assisted Organic Synthesis. In Green sustainable process for chemical and environmental engineering and science; Elsevier; pp. 1–41.

- Draye, M.; Chatel, G.; Duwald, R. Ultrasound for Drug Synthesis: A Green Approach. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A. Y.; Velasco, M.; Sánchez-Lara, E.; Gómez-Rivera, A.; Vilchis-Reyes, M. A.; Alvarado, C.; Herrera-Ruiz, M.; López-Rodríguez, R.; Romero-Ceronio, N.; Lobato-García, C. E. Synthesis, Crystal Structures, and Molecular Properties of Three Nitro-Substituted Chalcones. Crystals 2021, 11, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkle, P.; Gibian, H. Uber Chalkone. Chem. Ber 1961, 94, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Qunrong, W.; Liqin, D.; Aiqing, Z.; Duoyuan, W. Synthesis of Dinitrochalcones by Using Ultrasonic Irradiation in the Presence of Potassium Carbonate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2005, 12, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.; Eghbali, N. Green Chemistry: Principles and Practice. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merouani, S.; Hamdaoui, O.; Rezgui, Y.; Guemini, M. Modeling of Ultrasonic Cavitation as an Advanced Technique for Water Treatment. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 56, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S. M.; Costa, S. M. B.; Pansu, R. Structural Changes in W/O Triton X-100/Cyclohexane-Hexanol/Water Microemulsions Probed by a Fluorescent Drug Piroxicam. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 226, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Han, F.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J. Effect of Cosurfactant on Ionic Liquid Solubilization Capacity in Cyclohexane/TX-100/1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate Microemulsions. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 317, (1–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry* | Activation method | Base | Solvent | Time | Yield* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1** | Magnetic stirring | NaOH (2 Eq.) | Methanol | 120 | ---- | |

| 2 | Reflux | NaOH (2 Eq.) | Methanol | 240 | 25 | |

| 3 | Reflux | K2CO3 (0.3 Eq.) | Methanol | 240 | 29 | |

| 4 | Ultrasound | K2CO3 (0.3 Eq.) | Methanol | 60 | 22 | |

| 5 | Ultrasound | K2CO3 (0.6 Eq.) | Methanol/ cyclohexane |

60 | 49 | |

| 6 | Ultrasound | K2CO3 (0.9 Eq.) | Methanol/ cyclohexane |

60 | 44 | |

| 7 | Ultrasound | Na2CO3 (0.4 Eq.) | Methanol/ cyclohexane |

30 | 88 | |

| 8 | Ultrasound | Li2CO3 (0.4 Eq.) | Methanol/ cyclohexane |

30 | 48 | |

| 9 | Ultrasound | Cs2CO3 (0.4 Eq.) | Methanol/ cyclohexane |

15 | 80 | |

| 10 | Ultrasound | Ca2CO3 (0.4 Eq.) | Methanol/ cyclohexane |

60 | ---- | |

| DNCH | Time (min) | Temperature (°C) | Yield (%) | m.p (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 60 | 0 | 56 | 140-142 |

| 3b | 60 | 0 | 92 | 145-147 |

| 3c | 60 | 0 | 86 | 175-177 |

| 3d | 60 | 0 | 65 | 160-162 |

| 3e | 30 | 60 | 88 | 214-216 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).