Submitted:

26 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

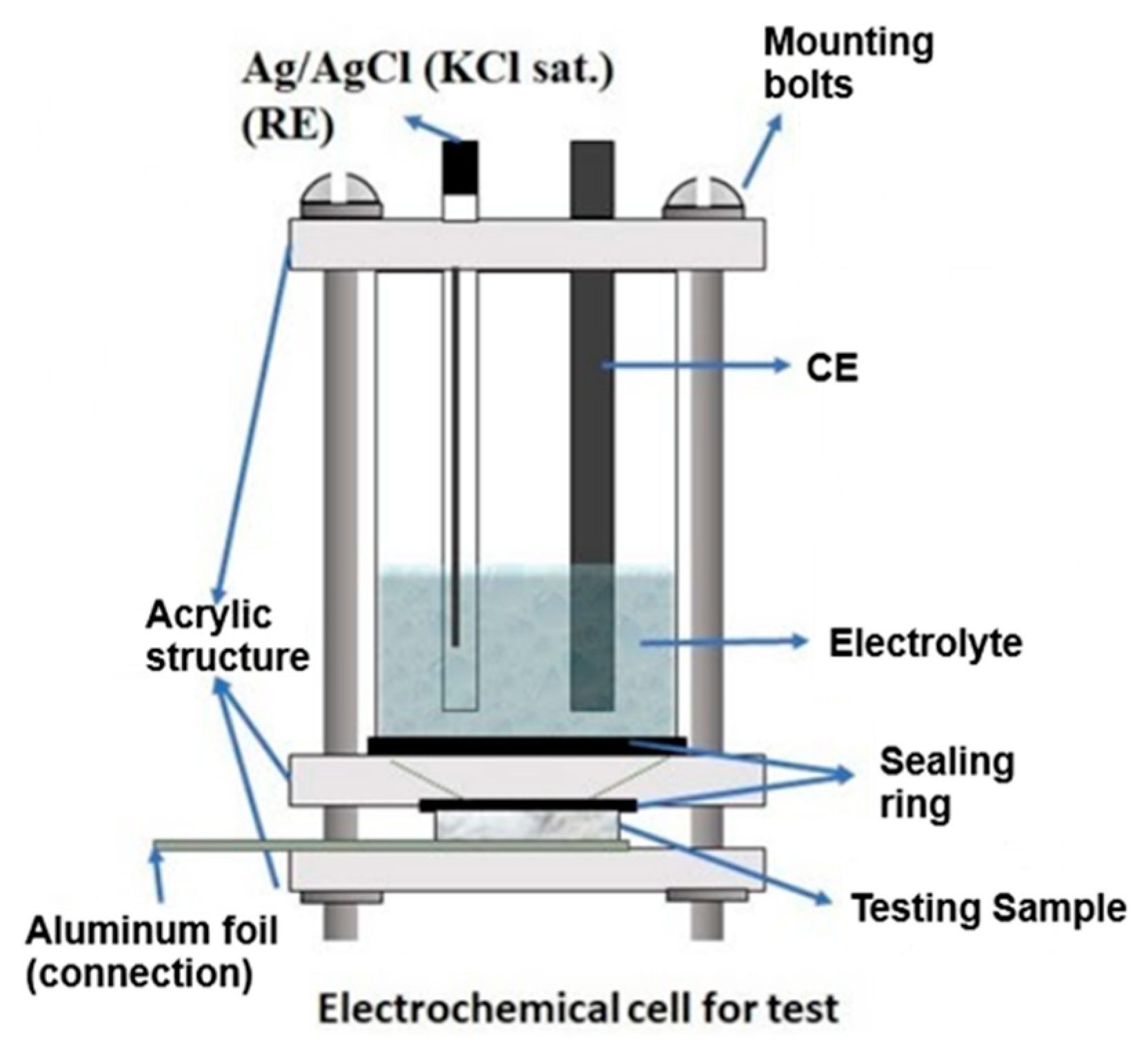

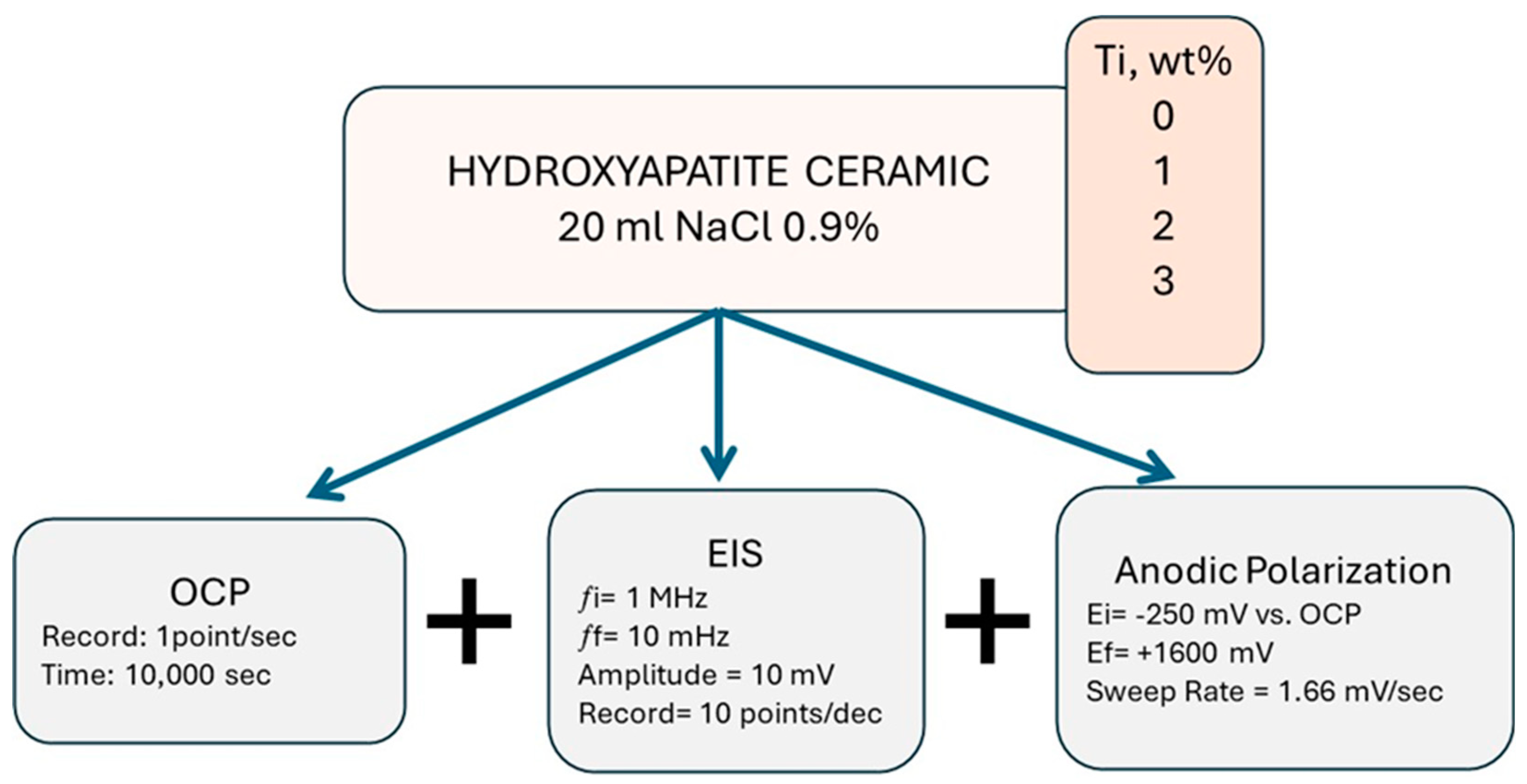

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

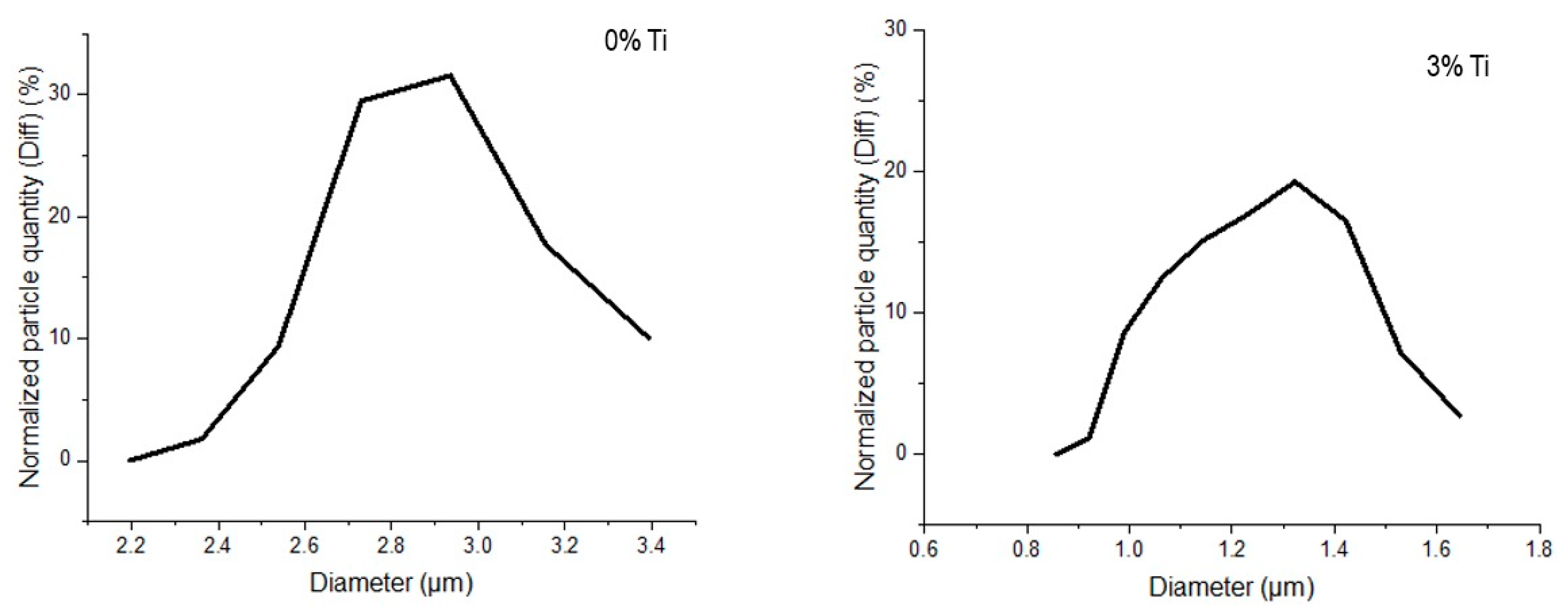

3.1. Particle Size

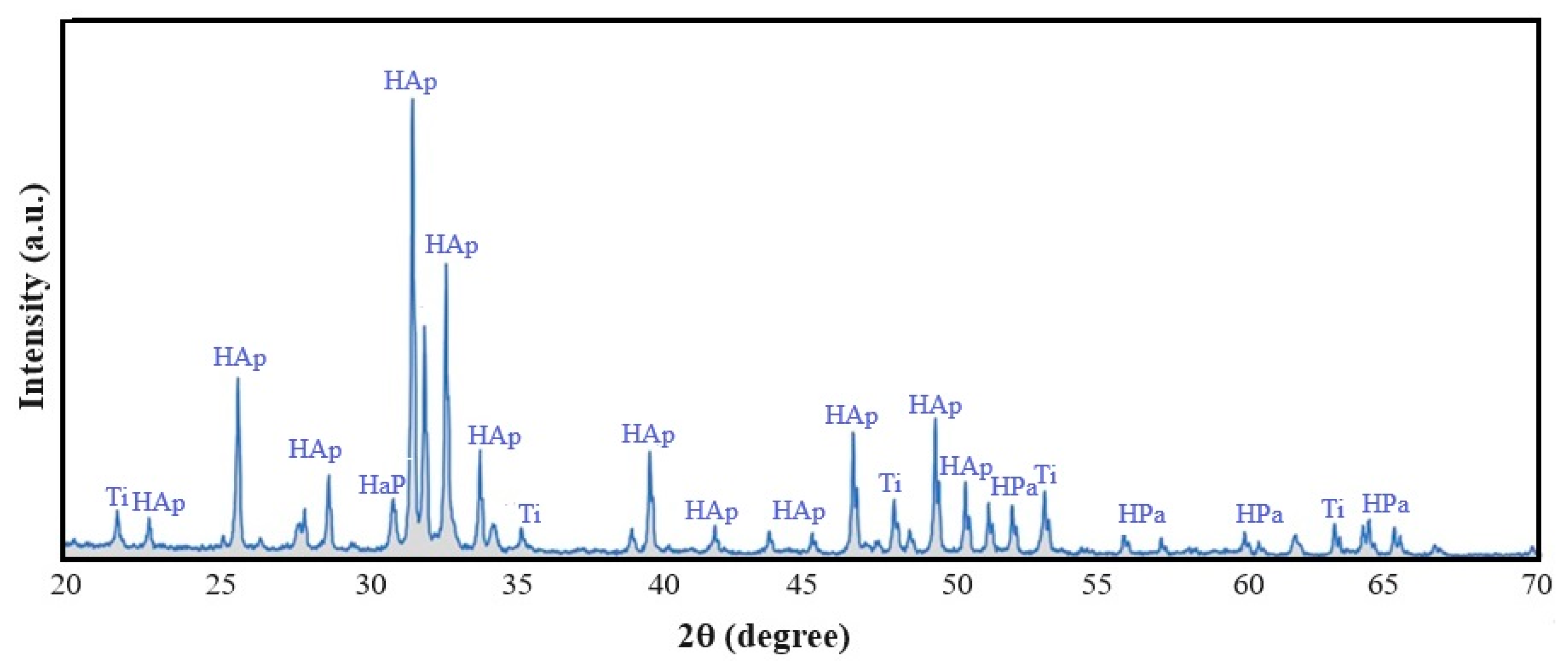

3.2. Structure

3.3. Microstructure

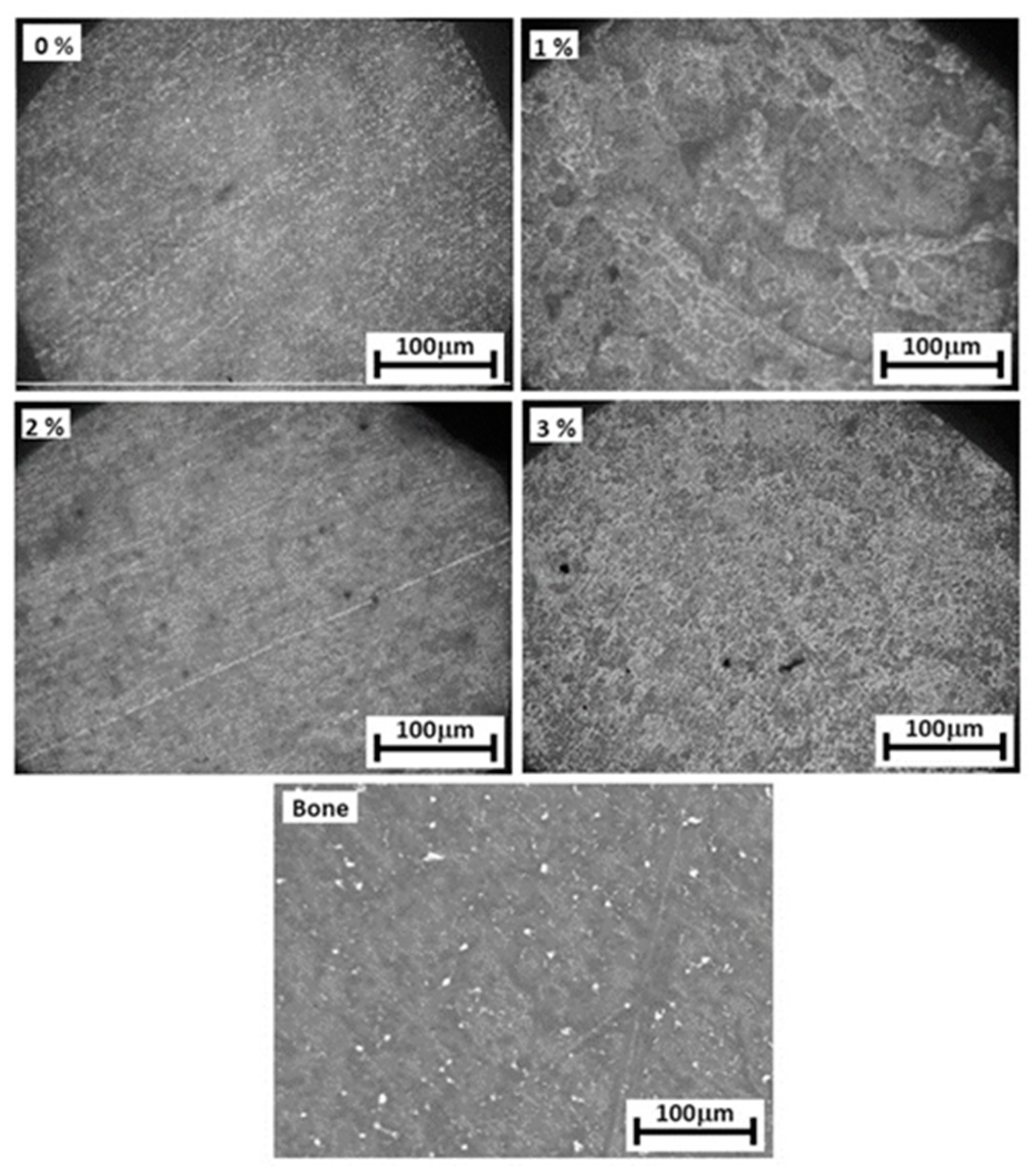

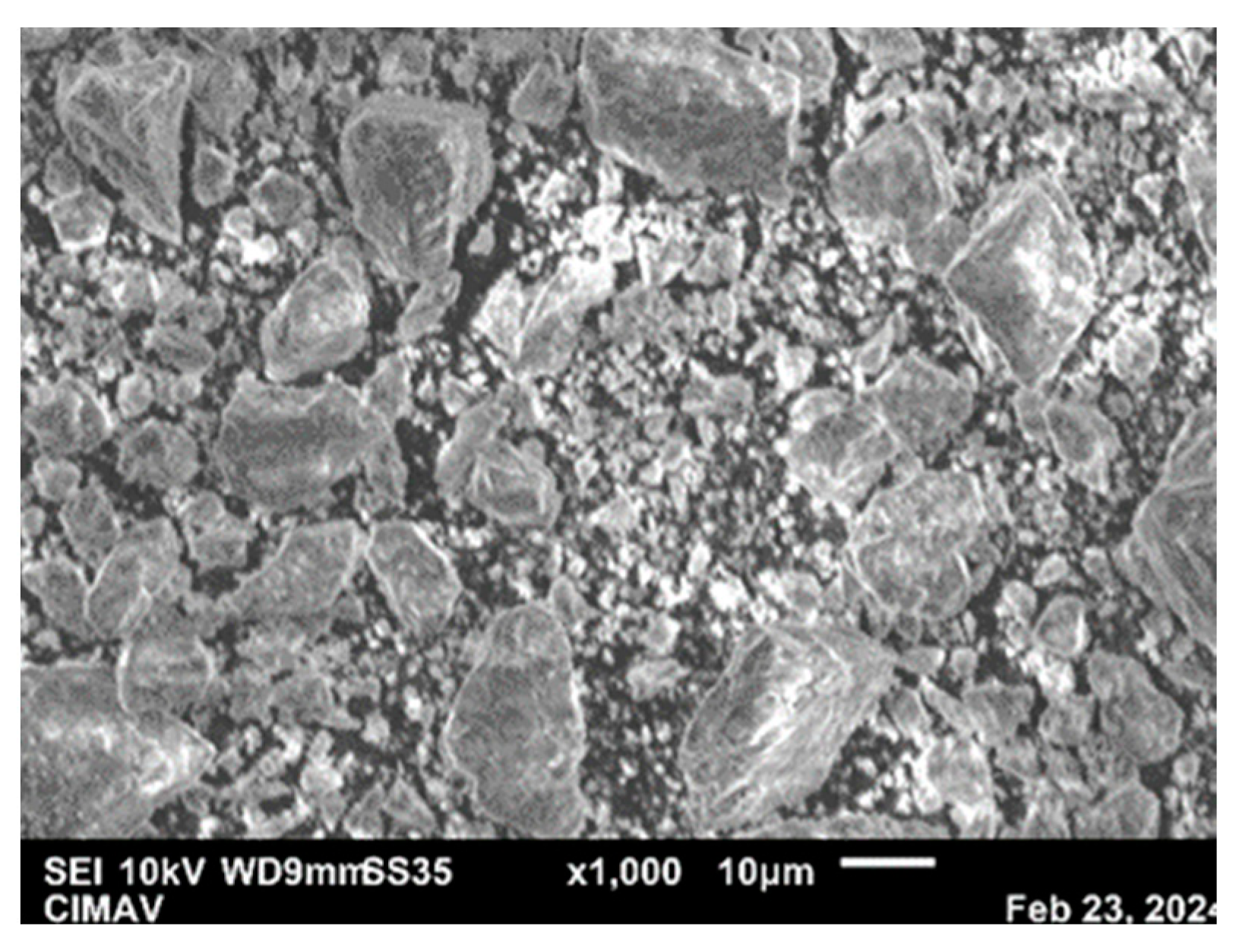

3.4. Morphology

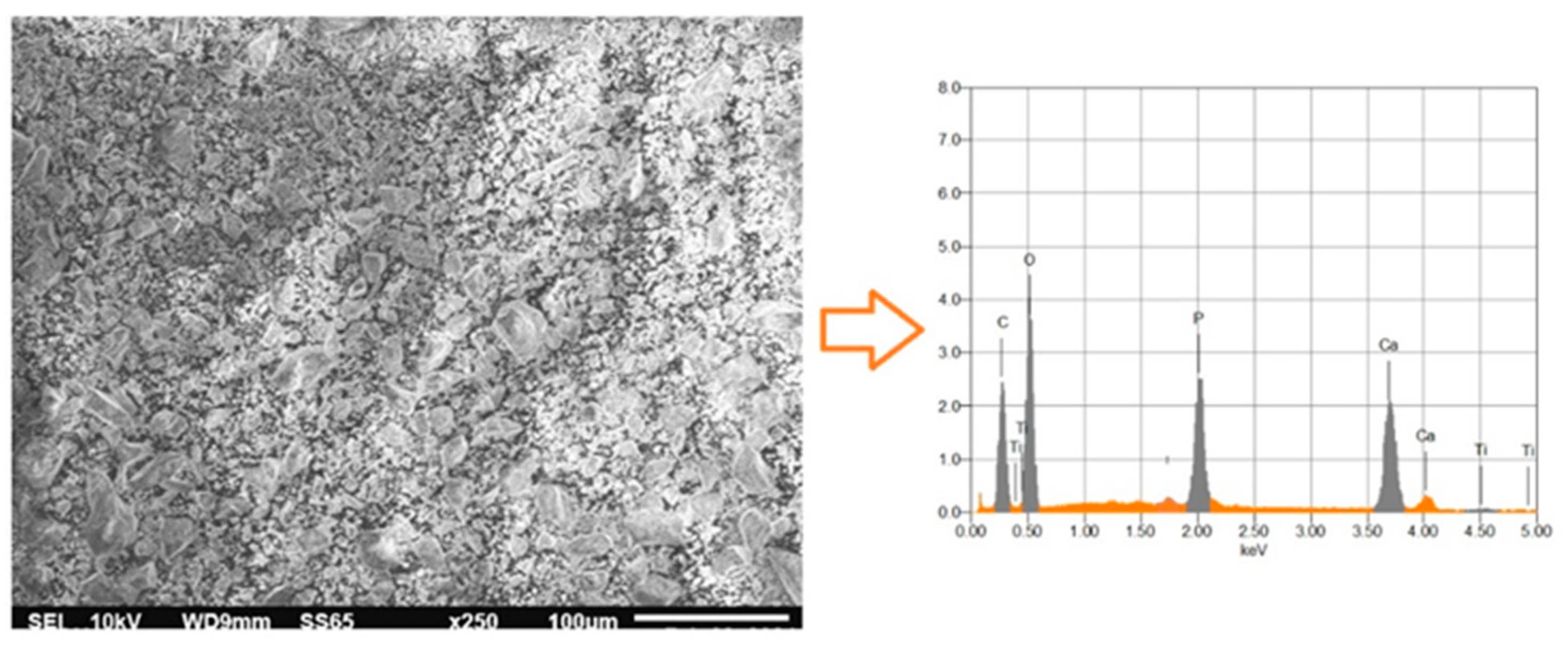

3.5. Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy

3.6. Mechanical Properties

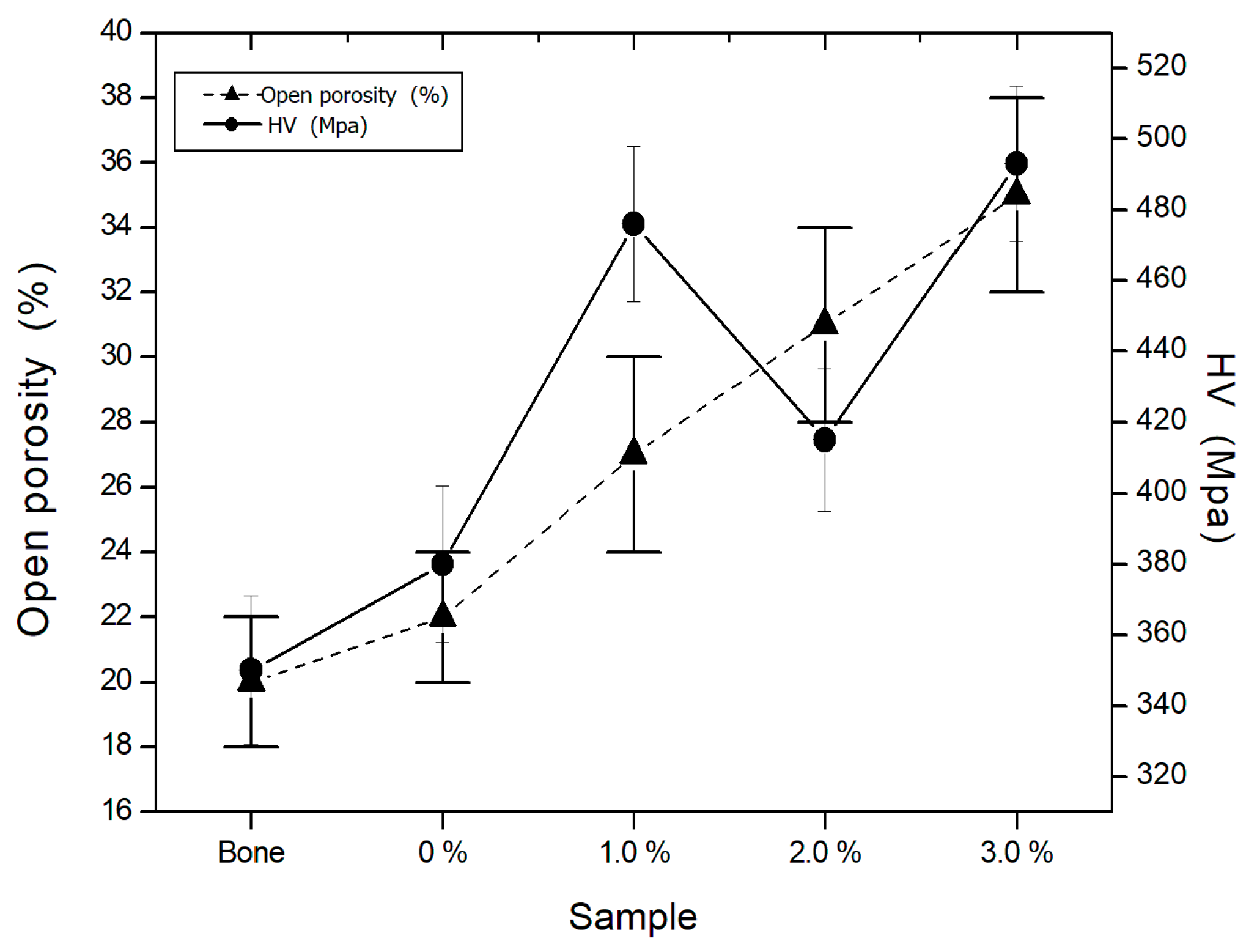

3.6.1. Open Porosity

3.6.2. Hardness

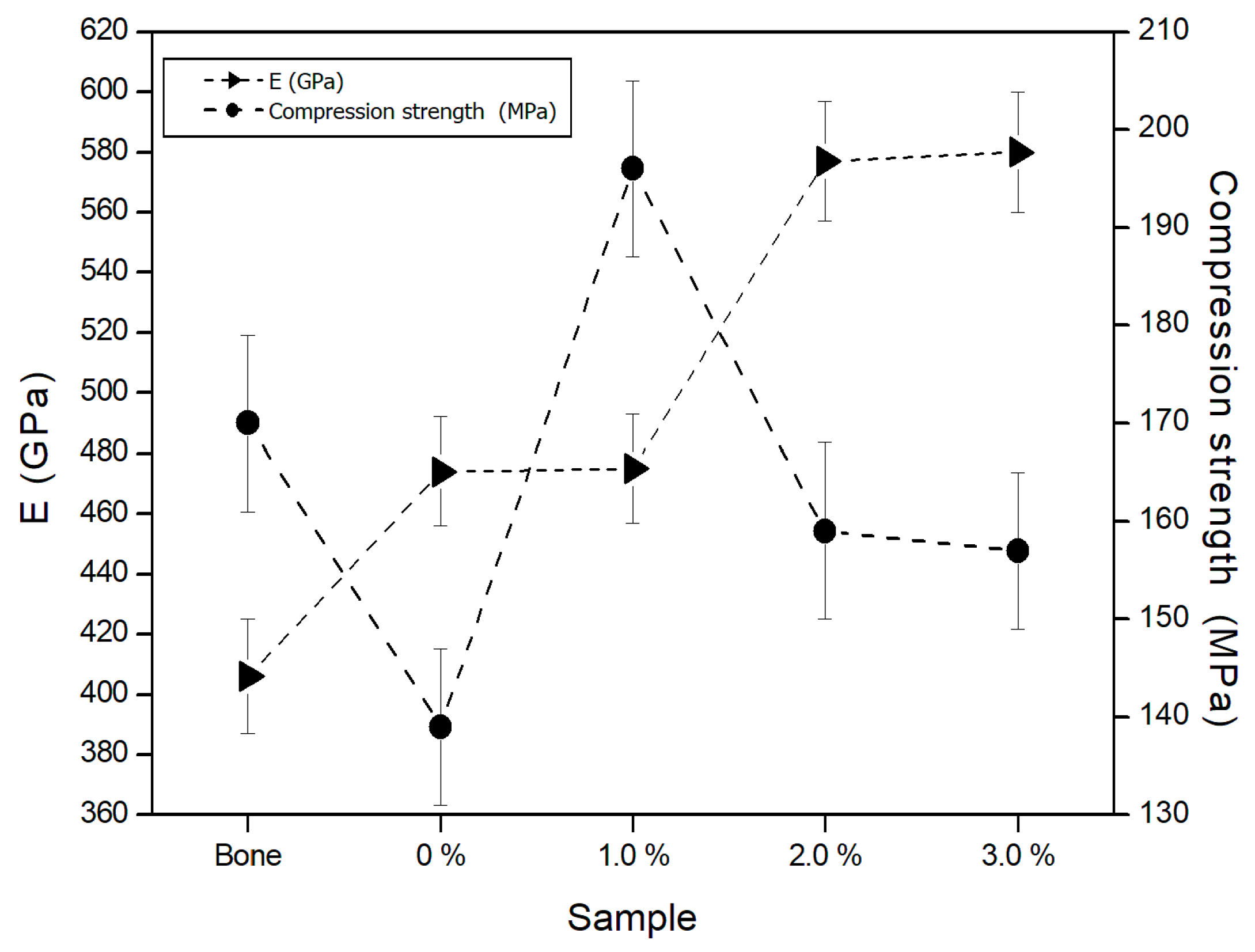

3.6.3. Elastic Modulus

3.6.4. Compression Strength

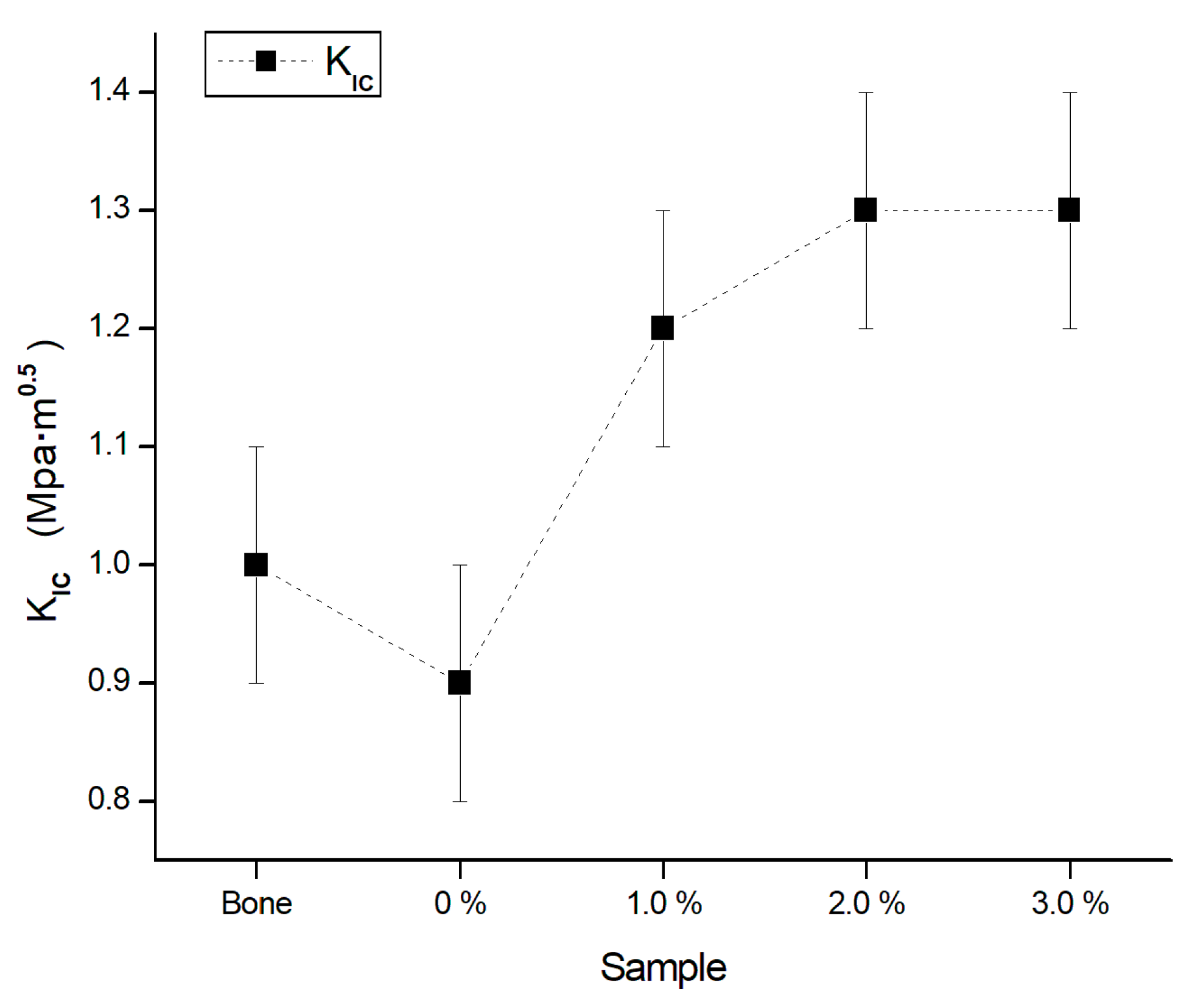

3.6.5. Fracture Toughness

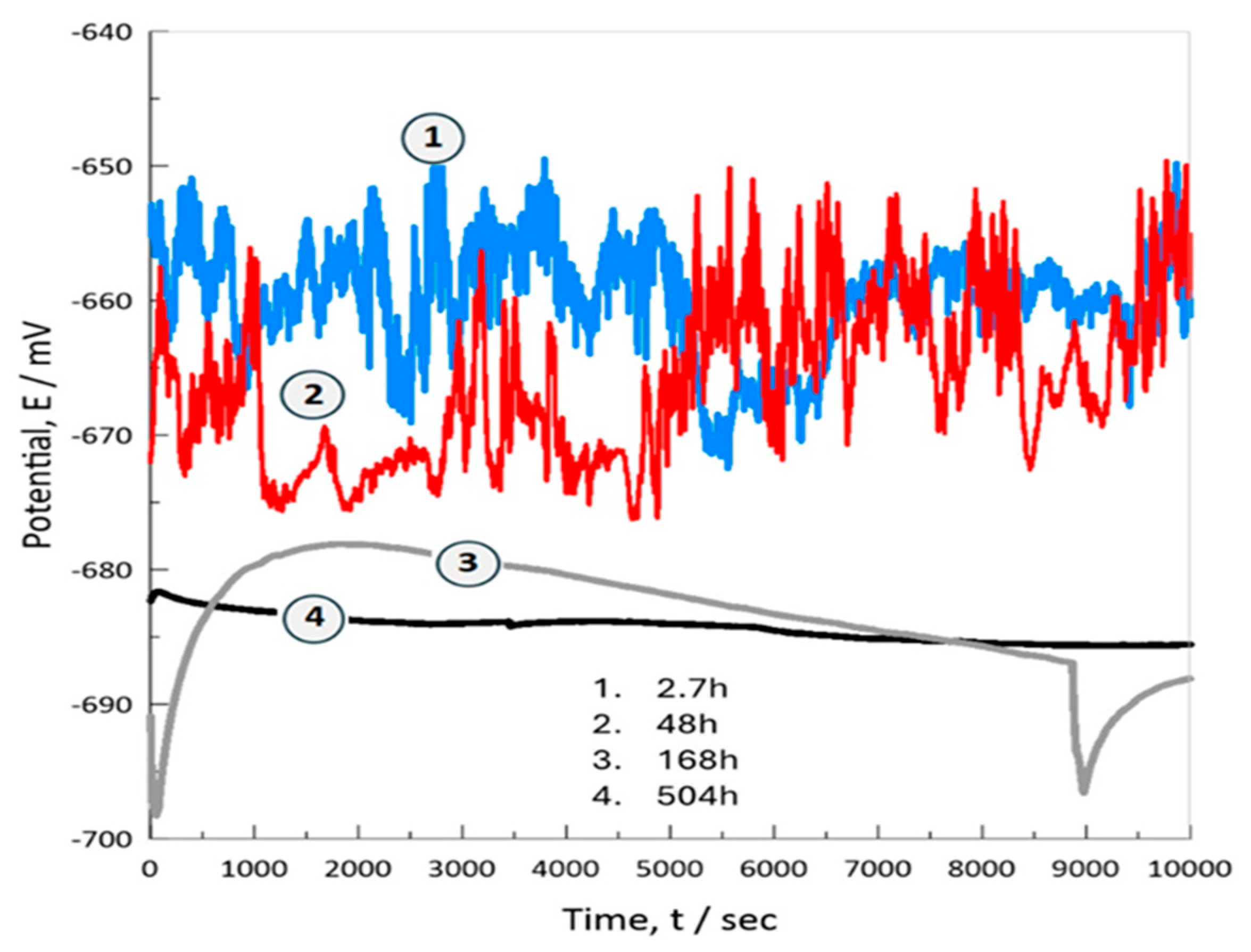

3.7. Electrochemical Characterization

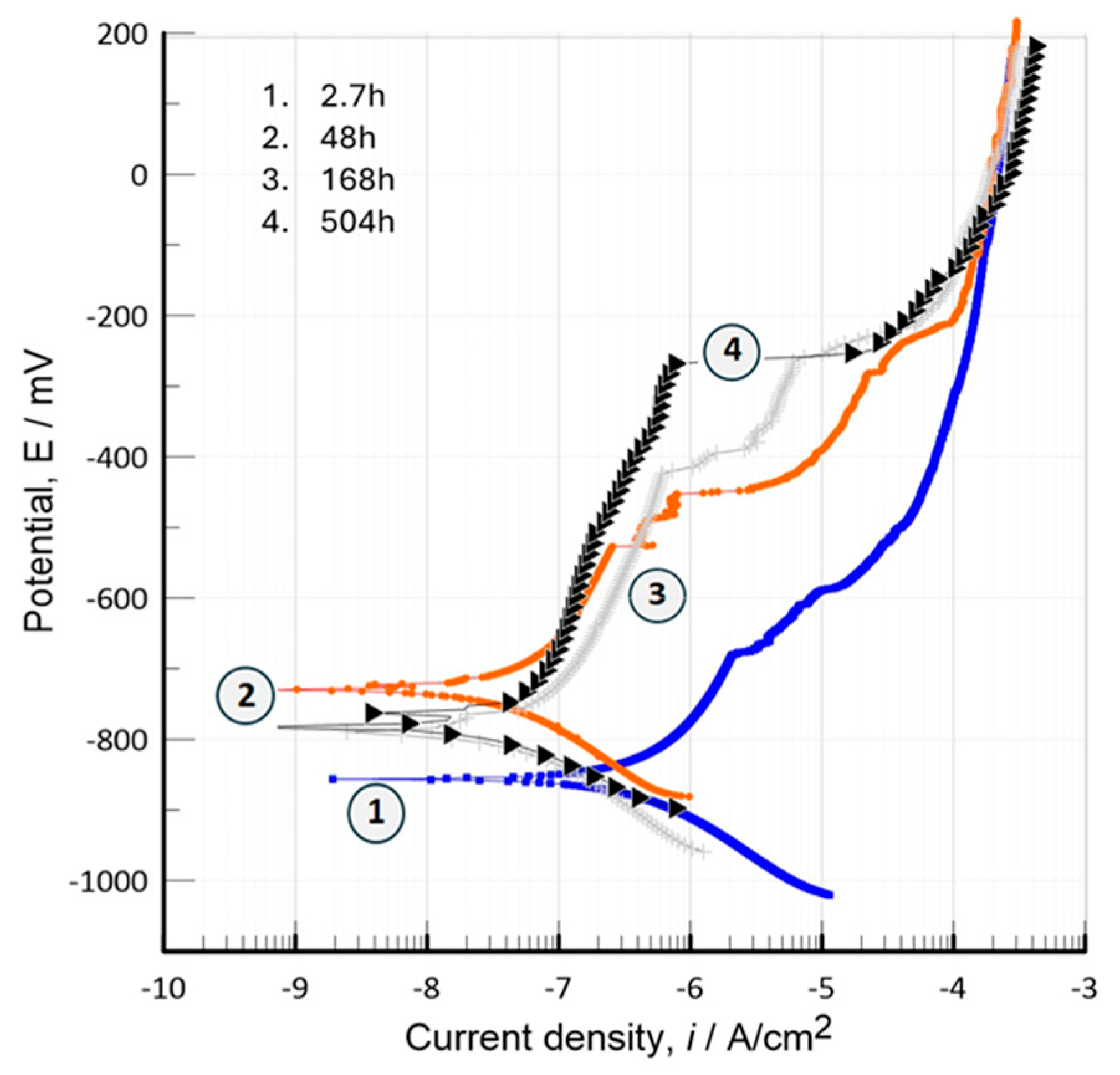

3.7.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization Curves (TAFEL)

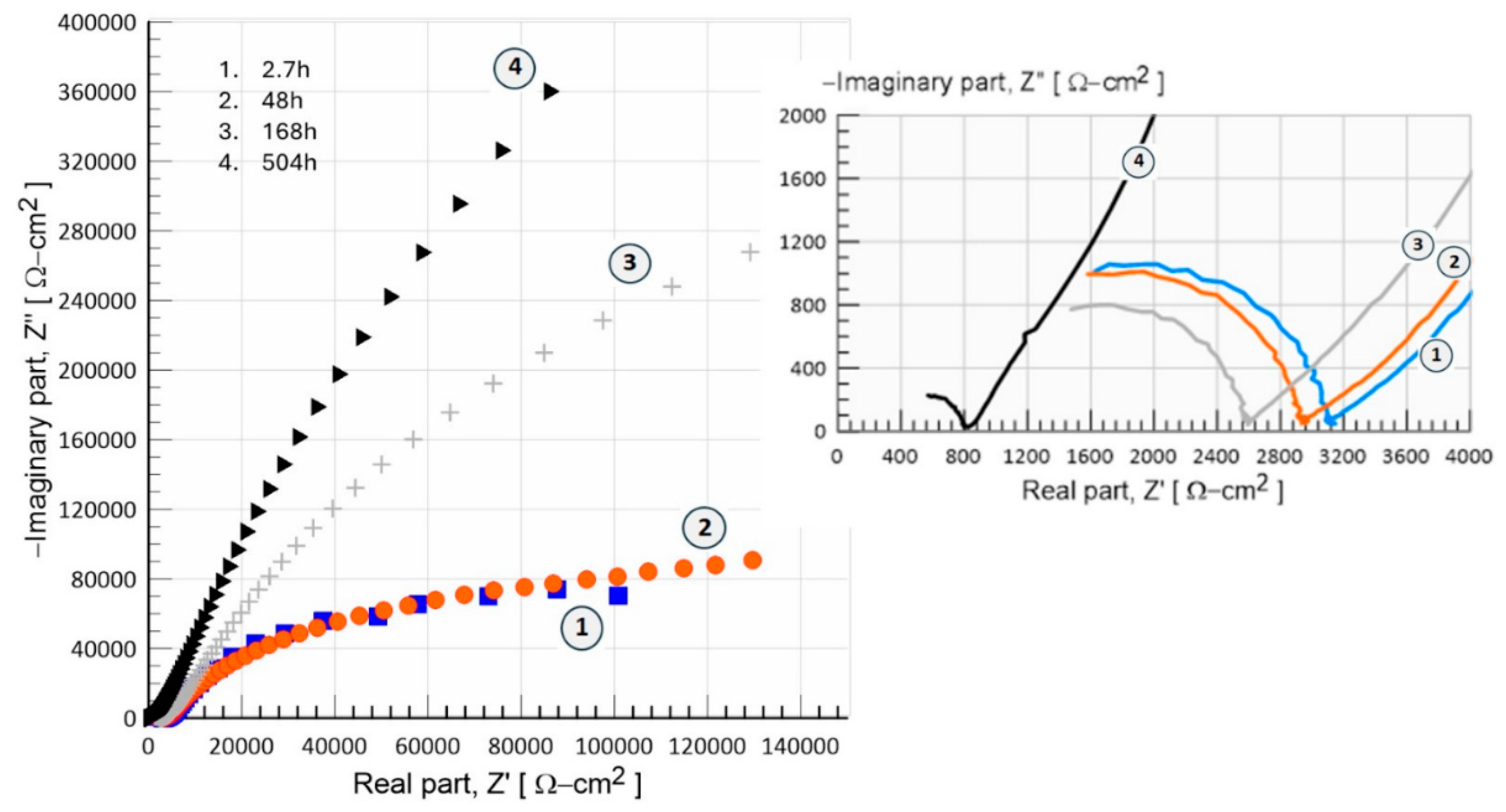

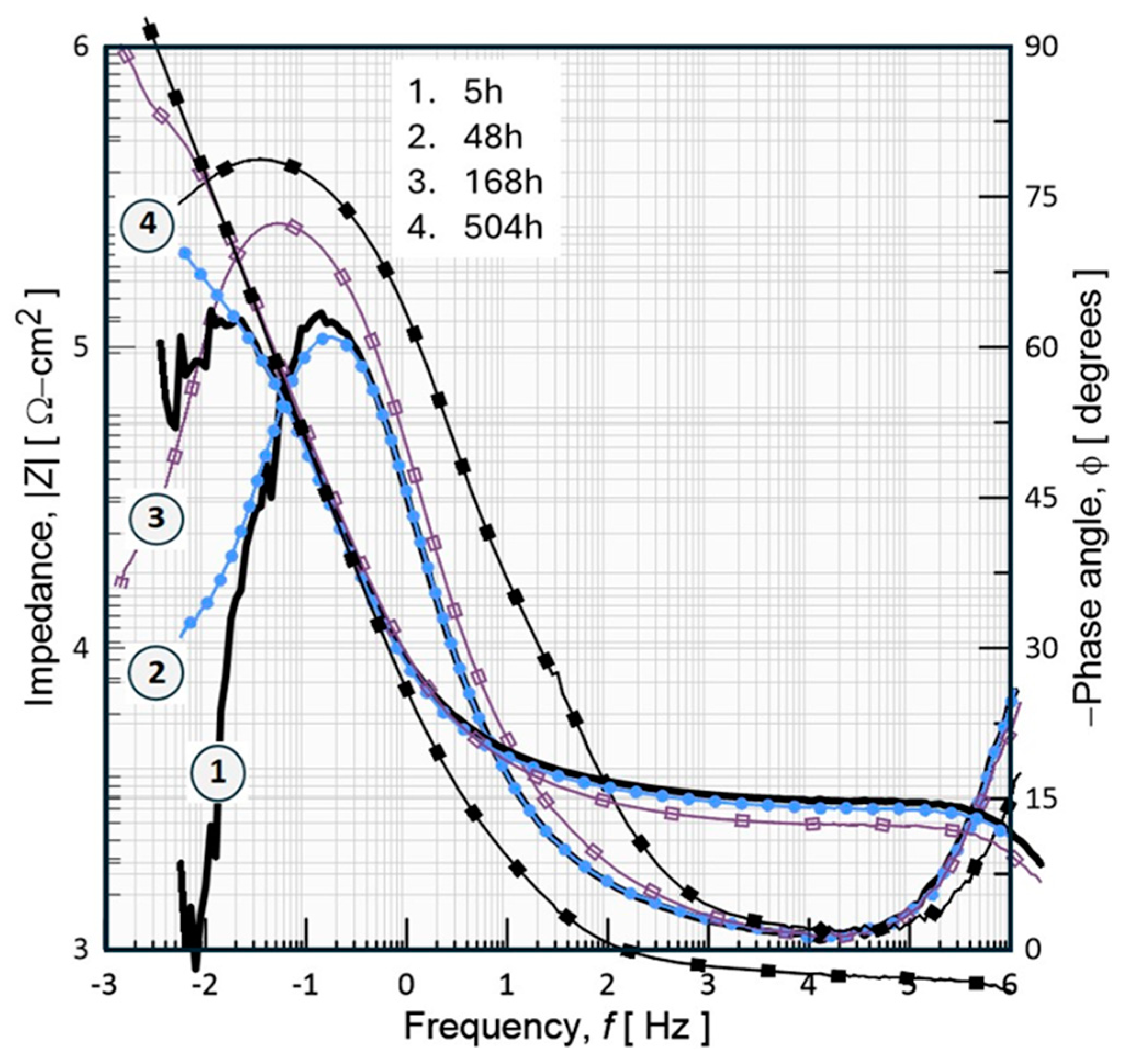

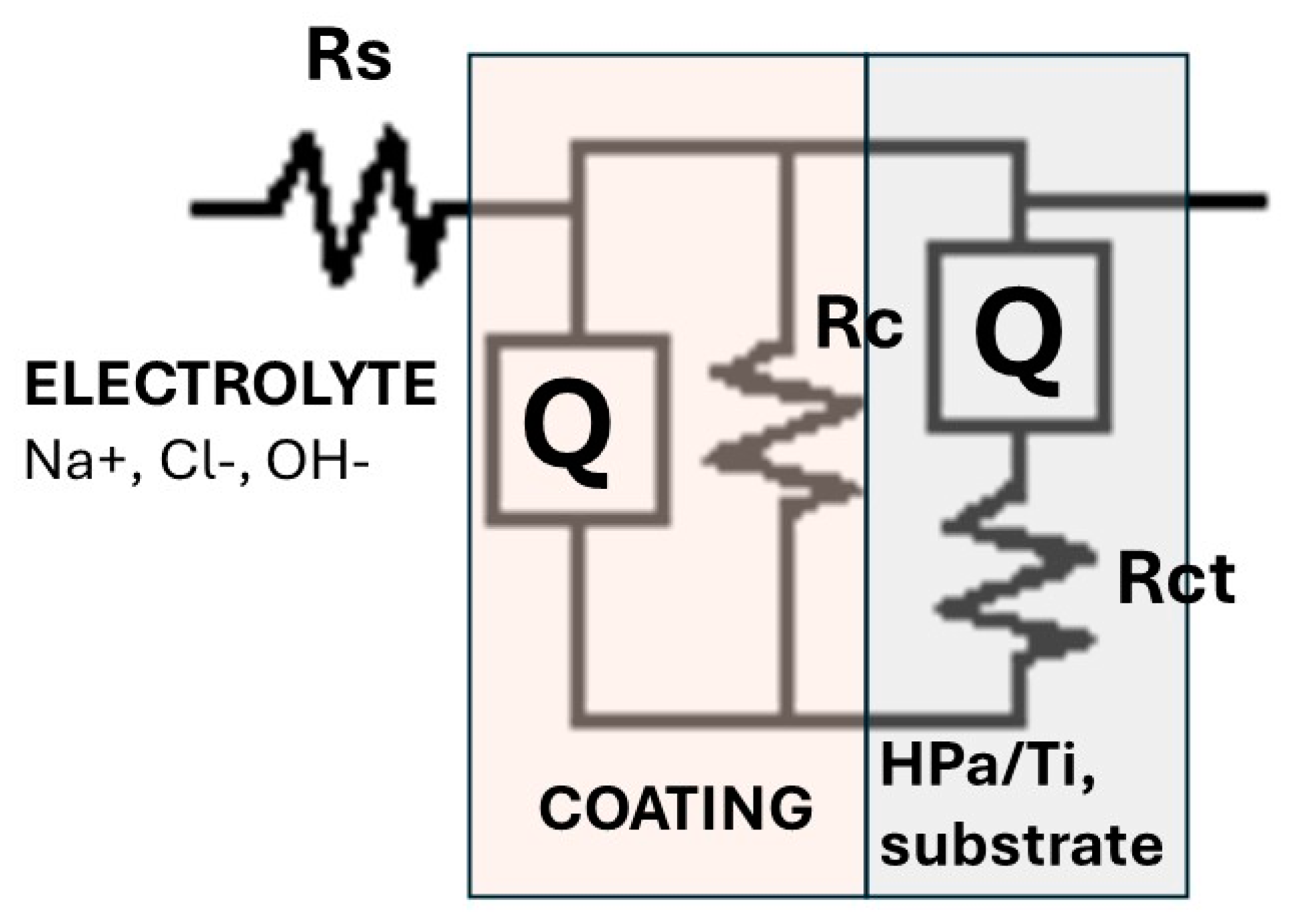

3.7.2. Electrochemical Impedance Measurements (EIS)

5. Conclusions

- ○

- Through the proposed methodology, hydroxyapatite biomaterials reinforced with titanium nanoparticles were successfully fabricated.

- ○

- The resulting biomaterial is constituted by two hexagonal compacted crystalline phases, one corresponding the hydroxyapatite ceramic matrix and a second phase that corresponds to the reinforced titanium metal.

- ○

- From the results obtained in the mechanical properties measurements, it is concluded that the biomaterial reinforced with 1 wt. % Ti, presents the best mechanical behavior.

- ○

- Electrochemical tests (OCP, anodic polarization, and EIS) show significant results in which the bioceramic is stabilized by the mechanism of chemical and physical adsorption of ions during its exposure for prolonged times (504h, 21d) in the physiological medium of 0.9%NaCl. Thus, developing bioactivity through a film formed by hydroxide compounds due to a surface sealing of the nanometric porous structure of hydroxyapatite, this phenomenon occurs at potentials close to -782.71 mV with an ionic charge transfer of about 0.43x10-9 A/cm2. This biofilm is a capacitor that stores a low ionic charge of 0.18 nF/cm2 and allows a charge transfer of 1.526x106 W-cm2 to develop its bioactivity.

- ○

- Finally, in practical applications such as insertion in a physiological medium, the biofilm plays a crucial role. It is firmly anchored to the bone and facilitates cellular osseointegration by providing biocompatibility. The Ti particles, on the other hand, contribute to mechanical strength and serve as anchoring sites to the bone.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ríos-Puerta, K.; Gutiérrez-Flores, O.D. Revista Politécnica, 2022, 18, 24–39. [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Hastings, G. Handbook of biomaterial properties, 1st ed; Springer Science & Business Media, London, UL, 1998.

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mat Sci Eng R: Rep, 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manam, N.S.; Harun, W.S.W.; Shri, D.N.A.; Ghani, S.A.C.; Kurniawan, T.; Ismail, M.H.; Ibrahim, M.H.I. Study of corrosion in biocompatible metals for implants: A review. J Alloys Compd., 2017, 701, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Garduño, M.V.; Reyes-Gasga, J. La hidroxiapatita, su importancia en los tejidos mineralizados y su aplicación bio-médica. TIP Rev Esp Cienc Quim Biol. 2006, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Deanne, K. Calcium phosphate apatites in nature. In Hydroxyapatite and related materials. eds. Browns, P.W. & Constantz, B., CRC Press, London. 2000, 46-52.

- Zapanta Legeros, R. Biological and synthetic apatites. In Hydroxyapatite and related materials. Eds. Browns, P.W. & Constantz, B. CRC Press, London, UK. 2000, 1-28.

- Fernández, J.; Gilemany, J.M.; Gaona, M. La proyección térmica en la obtención de recubrimientos biocompatibles ventajas de la proyección térmica por alta velocidad (HVOF) sobre la proyección térmica por plasma atmosférico (APS). Biomecánica. 2005, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, V.; Olivares, O.; Yépez, J.; González, A. Parámetros histológicos de la regeneración ósea guiada con hidroxiapatita FOULA en ratas BIOU: Wistar. Revista Odontológica Mexicana Órgano Oficial de la Facultad De Odontología UNAM., 2020, 23, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinschpun, L.S.; Oldani, C.R. Obtención de compuesto de Ti – HA por sinterizado a baja temperatura. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Argentina 2021, 8, 55–60. Available online: https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/FCEFyN/article/view/32233.

- Nomura, N.; Sakamoto, K.; Takahashi, K.; Kato, S.; Abe, Y.; Doi, H.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Kobayashi, E.; Kim, W.-J.; et al. Fabrication and Mechanical Properties of Porous Ti/HA Composites for Bone Fixation Devices. Mater. Trans., 2010, 51, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Ibáñez, I. Estudio de la viabilidad de adicionar magnesio a aleaciones pulvimetalúrgicas de titanio, para la obtención de productos densos y/o porosos. Universidad Politécnica de Valéncia, Spai. 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/174753.

- Barrabés, M. Optimización de las aleaciones de NiTi porosas para aplicaciones biomédicas. Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya, Spain. 2005. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2099.1/3183.

- Montañez, N.; Peña, D.; Cardozo, R.; Faria, M. Corrosión de nitinol bajo tensiones de fuerza en fluido fisiológico simulado con y sin fluoruros. Revista Facultad de Odontología. 2016, 28, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, J.F.; Han, Y.; Kim, S.; Kwon, S. CRC Materials Science and Engineering Handbook. 4th ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton., USA. 2015.

- Sánchez, A. Titanio Como biomaterial. Azul Web. 2014. Available online: https://www.azulweb.net/titanio-como-biomaterial/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Sáenz-Ramírez, A. Biomateriales. Revista Tecnología En Marcha, 2004, 17, 34–45. Available online: https://revistas.tec.ac.cr/index.php/tec_marcha/article/view/1432.

- Fendi, F.; Abdullah, B.; Suryani, S.; Raya, I.; Nilawati-Usman, A.; Tahir, D. Hydroxyapatite derived from fish waste as a biomaterial for tissue engineering scaffold and its reinforcement. AIP Conf. Proc. 2719, 020040 (2023), 8–9 September 2021, Palu, Indonesia. [CrossRef]

- Hartatiek, J.; Utomo, L.; Noerjannah, I.; Rohmah, N.Z. ; Yudyanto, Physical and mechanical properties of hydroxyap-atite/polyethylene glycol nanocomposites. Mater Today Proc, 2021, 44, 3263–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinashi, S.K.; Hussain, A.; Kumar, K.; Yadav, B.C.; Gautam, C. Synthesis and structural characterizations of HAp–NaOH–Al2O3 composites for liquid petroleum gas sensing applications, Oxford Open Materials Science, 2021, 1. [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, L.; Antoniac, A.; Manescu, V.; Robu, A.; Dinu, M.; Pana, I.; Cotrut, C.M.; Kamel, E.; Antoniac, I.; Rau, J.V.; et al. Preparation and characterization of hydroxyapatite coating by magnetron sputtering on Mg–Zn–Ag alloys for orthopaedic trauma implants, Ceram Int. 2023, 49, 26274–26288. [CrossRef]

- Youness, R.A.; Taha, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.A. Effect of sintering temperatures on the in vitro bioactivity, molecular structure and mechanical properties of titanium/carbonated hydroxyapatite nanobiocomposites. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1150, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.G.; Charles, E.A. Fracture Toughness Determination by Indentation. J Ame Ceram Soc. 1976, 59, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing Materials, ASTM E1876-22, Standard Test Method for Dynamic Young's Modulus, Shear Modulus, and Poisson's Ratio by Impulse Excitation of Vibration, 2022.

- American Society for Testing Materials, ASTM E384 – 16, Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials, 2016.

- American Society for Testing Materials, ASTM E9 – 89a, Standard Test Methods of Compression Testing of Metallic Materials at Room Temperature. (Reapproved 2000).

- García-Barea, E. Undergraduate Thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- Ighodaro, O.L.; Okoli, O.I. Fracture Toughness Enhancement for Alumina Systems: A Review. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2008, 5, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Dey, S.; Sekhar, A.P. Design of Alumina Reinforced Aluminium Alloy Composites with Improved Tri-bo-Mechanical Properties: A Machine Learning Approach. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2020, 73, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha Rangel, E. Fracture Toughness Determinations by Means of Indentation Fracture, In Nanocomposites with Unique Properties and Applications in Medicine and Industry, Ed. John Cuppoletti. IntechOpen, London, UK, 2011, 1-18. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/16971.

| Inmersión Time, [h] | Capacitance-Cc, [nF/cm2] | Coating Resistance, Rc [Ω-cm2] |

Charge Transfer Resistance, Rct [Ω-cm2] |

Ecorr / [mV] | Icorr [nA/cm2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5h | 5.27 | 3447 | 2.745x105 | −856.32 | 2.40 |

| 48h | 5.11 | 3254 | 2.939 x105 | −730.27 | 0.77 |

| 168 | 3.80 | 2963 | 3.15x105 | −789.46 | 3.06 |

| 504 | 0.18 | 810 | 1.526x106 | −782.71 | 0.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).