1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) commonly referred to as stomach cancer, continues to be a major public health problem globally and is ranked as the fifth most prevalent cancer and third most leading cause of cancer related death globally. Based on history, an indication on the trends of incidence of gastric cancer indicated that the occurrence rate had reduced since the middle of the 20th century, and it is further confirmed that countries such as the United States has been experiencing declining incidence rates for the past few decades [

1]. Nevertheless, this mortality trend is reversed by an upward trend in gastroesophageal cancers. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent variety of gastric cancer that develop in the mucosa of the abdomen, two more rare types are lymphomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) [

2]. Karimi et al., 2014 pointed out that it is important to study the incidence, survival and mortality rates of gastric cancer to tackle this cancer type [

3]. According to the GLOBOCAN 2018, GC ranks fifth among common malignant neoplasms and third in cancer mortality worldwide, mostly in males of elderly age; therefore, the need for intervention-associated prevention [

4]. Furthermore, a general review of literature shows that GC factors depend on geographical location and the set lifestyle including diet and Helicobacter pylori infection [

5]. The increasing prevalence of cardia gastric cancer, and the declining trend of non-cardia types of Gastric cancer suggest a changing pattern in the distribution of stomach cancer. These changes demand targeted preventive efforts such as changing the diet and quitting smoking [

4].

1.1. Overview of Gastric Cancer Prevalence and Mortality

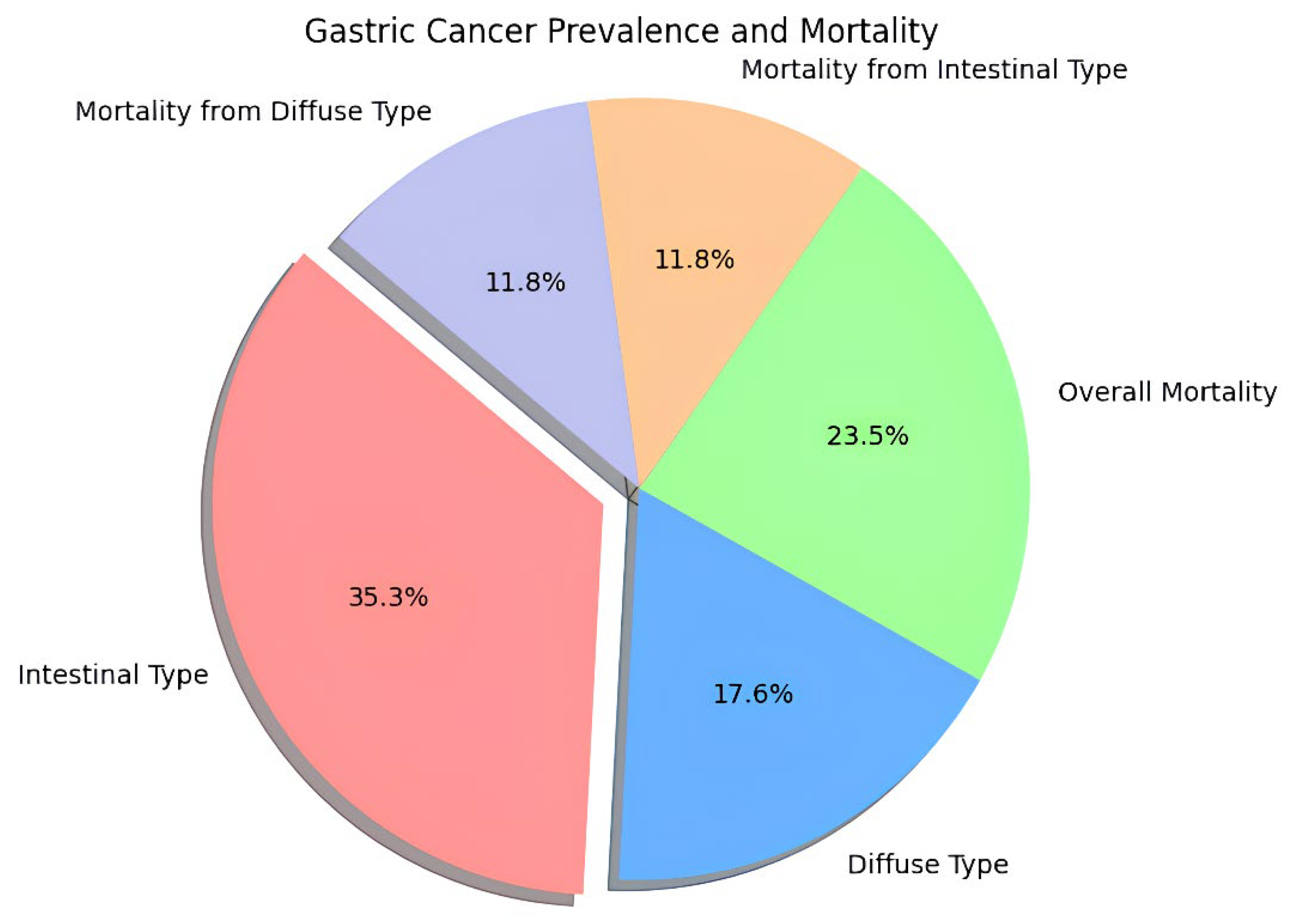

Stomach cancer is still one of the most life-threatening diseases in the world with considerable geographic distinctions in incidence and mortality figures (

Figure 1: Gastric Cancer Prevalence and Mortality). New cases in the year ended at about 1.1 million, and death toll at nearly about 770,000; hence is one of the prevalent cancer diseases globally [

6]. These incidence rates are considerably higher among males which are 15.8/100000 compared to 7.0/100000 among females, and the ranking countries being Eastern Asia particularly Japan as well as Korea [

7]. For example, the incidence rate for males is 48.1 per 100000 for Japan and it clearly illustrates the geographical inequality of gastric cancer [

6].

The mortality-to-incidence ratio (M: I is also worrisome; gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in the world with a high proportion of mortality in high incidence areas of Eastern Asia [

8]. For instance, the mortality per 100,000 in Mongolia is 36.5; that makes it even more crucial to devise efficient ways of preventing and early diagnosis in these countries. Additionally, forecasts suggest that, if the current trends will persist, the rate of new cases could increase to 1.8 million for the year 2040 with deaths of 1.3 million [

9].

In a study conducted by Miller et al. (2019) they opined that global incidence of gastric cancer is in a decline; however, mortality from the disease is still high mainly because of regions with high incidences of Helicobacter pylori bacteria [

10]. This forces a need of understanding the different epidemiology patterns related to gastric cancer as noted by Karimi et al. (2014) pointing out that risk factors for gastrointestinal cancers are as multifactorial and can include diet, genetic and immunological markers with serologic detection being important [

3]. The statistical overview of research data regarding gastric cancer is more upsetting in some directions; Miller et al., 2022 identified it as the third most lethal cancer globally with higher incidence of mortality among males aged over 60 [

11]. The emerging cases of cardia gastric cancer are worrisome and seem to change the epidermiology of gastric malignancies (Rawla & Barsouk, 2018). These changes may represent new dietary and procurement risks and constitute one of the reasons forcing a deeper investigation into these patterns [

4].

The disparities in incidence and mortality occurrences of the cancer across the world imply that the causes for gastric cancer are diverse in nature. Such things like diet systems, attitudes, and hereditary qualities affect these trends violently. For instance, Rugge et al. (2015) condense that these regional differences must be further considered when designing prevention measures [

12]. Cardia gastric cancer incidence is on the rise while the overall rate is falling and this phenomenon compels researchers to ponder over the shifts in gastric cancer epidemiology suggesting the possibility that traditional risk factors are changing or that new factors indicating risk are being discovered [

13]. Furthermore, a relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer is clear; several works suggest that it continues to be one of the factors determining high mortality rates among patients with this pathology [

14]. The discussion of serologic markers and the discussion of the precursor lesions gives future possibilities for early detection, which could enhance SC mortality rates [

3]. Risk factor assessment is important because all these measures have the potential to substantially decrease the incidence of gastric cancer.

However, several questions about gastric cancer development and progression remain poorly understood even in the light of more recent findings in the subject. Specifically, there is the lack of studies aimed at the evaluation of the effect of combining genetic testing with other preventive measures, including dietary alterations, and smoking cessation [

15]. Moreover, Miller et al., (2022) have noted that there is a need to continue providing public health initiatives that will tackle both incidence, and deaths due to gastric cancer [

11].

2. Search Methodology

When searching for articles and studies to reference the topic on immunotherapeutic strategies in gastric cancer, a search was conducted in a way that makes the articles found both relevant and of good quality. Choosing of the databases was crucial, and to ensure a variety of sources are obtained, only those from the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were selected. The search was done from the perspective of the following specific terms: gastric cancer, immunotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and adoptive cell therapy which formed the basis of the review. The inclusion criteria were formalised and focused on considering only the articles of the peer-reviewed journals, and only the clinical trials, which were published within the last five to ten years. This time was chosen to have an idea about the recent developments in study. The information was then extracted systematically bearing in mind features such as efficacy, mode of action, and effects on patients. There were specific aspects that were followed during data collection and analysis: diverse static data collection forms were utilized in each of the implemented strategies to ensure uniformity and minimize the effects of investigator-induced variability, data extraction was done independently by the different reviewers. Finally, this strict approach was designed to correlate data that might support subsequent studies and medical treatment of gastric cancer with immunotherapy.

3. Mechanisms of Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has become a promising therapeutic option in cancer management with the principle of using immune system to fight tumor development [

16]. Immune-tumor interaction remains one of the key components of this therapeutic approach to consider if the anti-cancer effect is to be achieved [

17]. The TME is underlain by diverse cell types embedded in a milieu of complementary cellular roles, such as immune cells, fibroblasts, and the ECM, all of which play a major role in modulating the immunological response to cancer. More recent work has therefore sought to reveal the multiple ways by which immunotherapy reprogrammes the TME and the consequences such changes have on treatment outcomes [

18]. These include carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the process of establishment of immunosuppressive TME especially in the case of pancreatic cancer. Samstein et al. (2019), showed that FAP+ CAFs mediate immune exclusion of T cells due to the secretion of chemokine CXCL12. These findings confirm that immunotherapeutic antibodies can be made more effective when directed at CAFs and that the identity of the TME should be considered when developing treatment plans. While the removal of FAP+ CAFs not only enables a better T cell infiltration, but also reveals which existing immunotherapies can be effective when the TME is enhanced [

19].

Moving from the effects of the CAFs, the interactions of cancer cells with the immune system through the means of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) hold the following. Ru and colleagues noted that although ICIs have revolutionized cancer treatment, resistance still poses a big problem. They have been shown to be highly dependent on the TME, which either supports or negates immune response efforts. Investigation of local immune changes after receiving ICI therapy is critical to improving treatment plans, indicating that future research on the development of function and relevance to the TME of resistance mechanisms is warranted [

20]. Furthermore, the immune contexture of tumours is shaped by different immune cells such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Bagchi et al. (2020) mentioned clearly that such cells are involved in immune suppression and tumor advancement. According to them, trying on the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) can alter macrophage behaviour for the better – for antigen presentation in addition to T cells. This result is a reminder of the need to decode the intricate TME immune cell interactions and ways to manipulate them to enhance immunotherapy efficacy [

21].

Thus, assessing cellular interactions also reveals that the physicochemical characteristics of the TME also regulates immune response. Labani-Motlagh et al. (2020) pointed out that tumor acidity prevented T cell activation that put a boundary in immunotherapeutic approaches. In their study, they show that elimination of tumor acidity improves T cell penetration and the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors, which underlines the role of TME properties manipulation for immunotherapy optimization [

22]. Moving to another dimension, recent evidence has emerged that examines the effect of microbiota on tumor immunity. Zhu et al. (2015) pointed out that individual bacterial strains can boost T cell proliferation by releasing such metabolites like inosine as to improve immunotherapy outcomes. This has underlined an unexplored strategy of developing a combination therapy by adding microbiome manipulation to existing immunotherapeutic strategies [

23].

However, these progresses seem to leave some gaps of understanding over the relations of the TME with immunoisolation and immune escape mechanisms. For example, the mechanisms by which tumors modulation PD-L1 to dampen T-cell activity is not fully defined. According to research done by Henke et al. (2020), it was shown that several pathways impact the levels of PD-L1, the implication of which is that the understanding of these signalling can provide insight into improvement of the effectiveness of anti-PD-L1 [

24]. More research on the part of the ECM should be conducted in terms of modulating immune responses as well because, according to Mager et al. (2020) the ECM has been Also, the active participation of the ECM in the tumors’ behaviour and therapy reactions should be investigated more [

25].

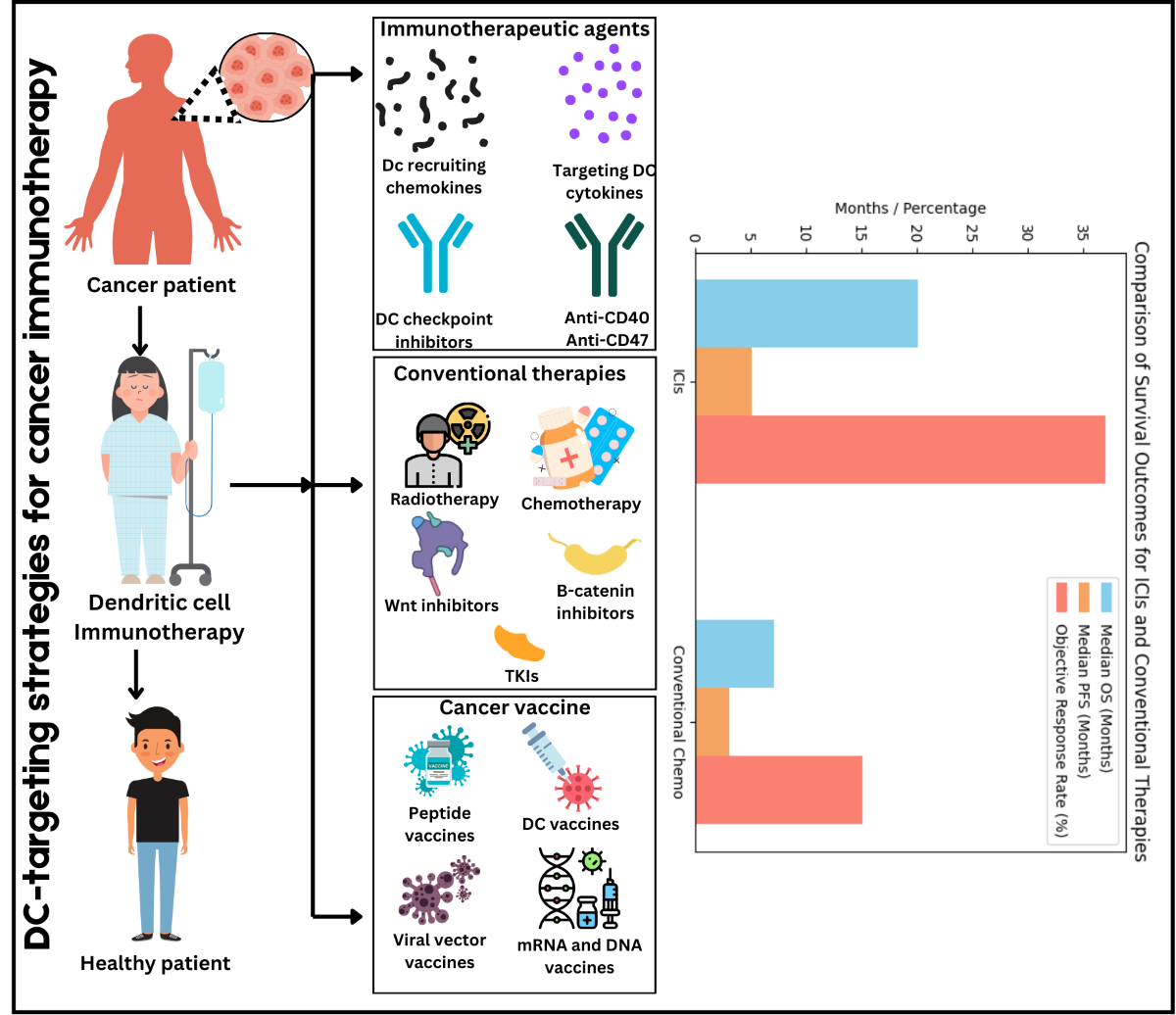

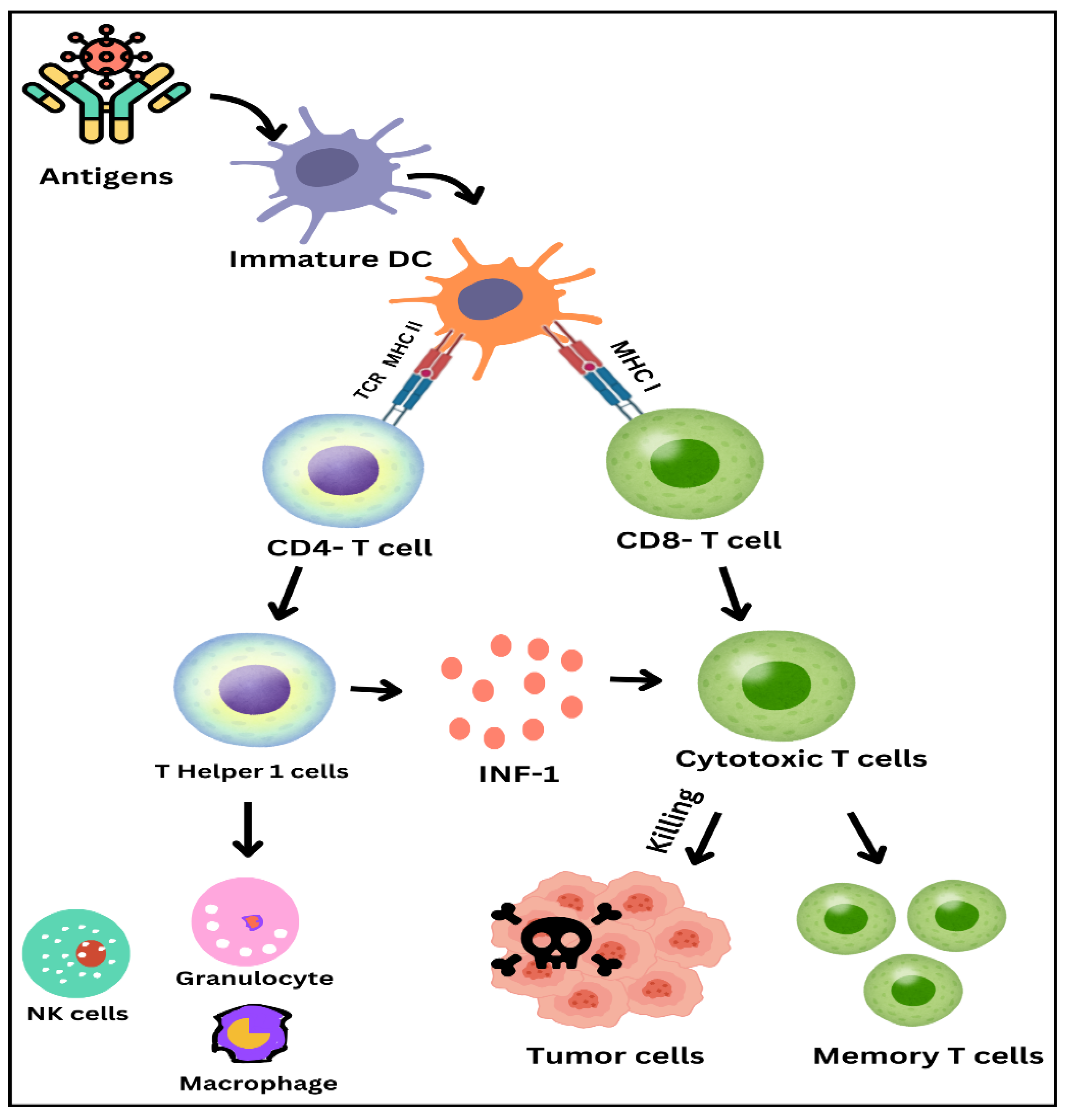

As illustrated of Immune response activation process in

Figure 2, dendritic cells and T-cells play crucial roles. It starts from antigens metic out by immature dendritic cells. These cells then mature and present the antigens to T cells in presenting the antigens, most of the maturity occurs on the dendrite. This encounter is done through the T cell receptor, and the major histocompatibility complex molecules. Ranked in importance, antigen presentation occurs through MHC II in T cells for immunoglobulin and MHC I for cytotoxic T cells in this case, T- helper 2 cells appeared from CD 4+ T cells They in turn release interferon-gamma to activate natural killer cells, granulocytes, and macrophages. CD8+ T cells further divide into cytotoxic T cell and kills these tumor cells. Also, some T cells become memory T cells with a high ability for immunity to the pathogen or foreign substance. The ‘theatre of immune response’ you see here identifies elements of the adaptive immune response and brings explanations to the actions of cell types and molecules in fighting infections and tumours.

4. Types of Immunotherapeutic Approaches

4.1. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs)

Previously known as immune-oncology agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have radically altered the approaches to cancer treatment by boosting immune system’s capacity to identify and destroy malignancies [

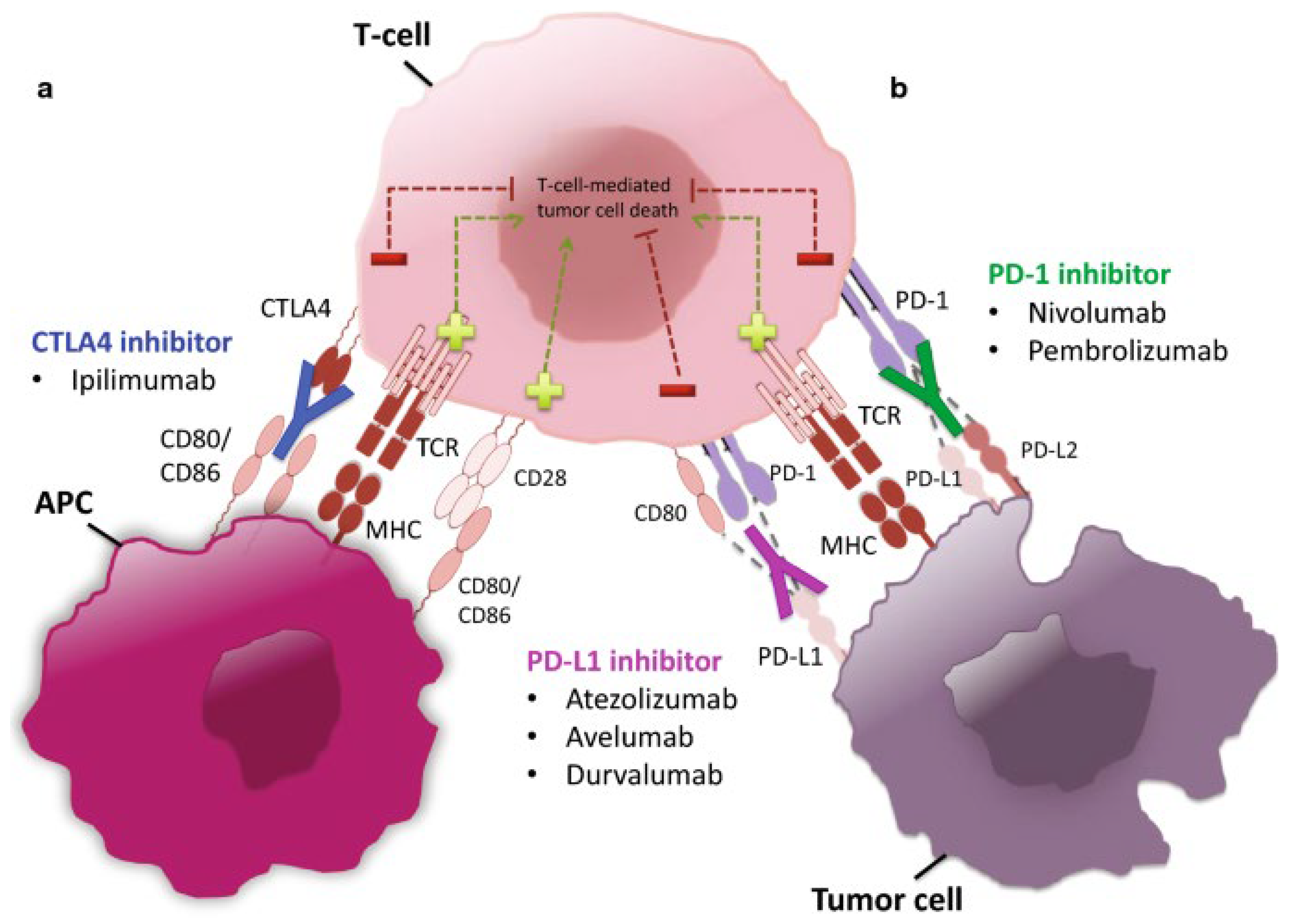

26]. The start of ICIs dates to discovery of immune checkpoints, which are regulatory mechanisms that tumors use to hide from immune system. The first major step forward occurred in 2011, when the FDA gave ipilimumab (Yervoy), an antibody against CTLA-4, the green light, signaling the start of the modern period of cancer therapy [

27]. Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab emerged next as PD-1/pD-L1 inhibitors, that have revolutionized the treatment of several types of cancer. Immune checkpoint targeting was proposed based on basic discoveries that were made in the late 1990s and the early millennium [

28]. Primer work done by James Allison and Tasuku Honjo identified CTLA-4 and PD-1 as avenues of interest to therapy [

29]. Based on the work he revealed that it was possible to strengthen anti-tumor immunity with the help of blocking CTLA-4, which led to the creation of ipilimumab. Likewise, the young Honjo built upon another researcher’s discoveries to establish subsequent PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors [

30].

Table 1 lists approved immune checkpoint inhibitors from 2010 to 2024, targets, approval year, indication, and referenced information. This text provides an outline of the current state of the art in the use of ICIs in treating cancer and points to further advancements in this area.

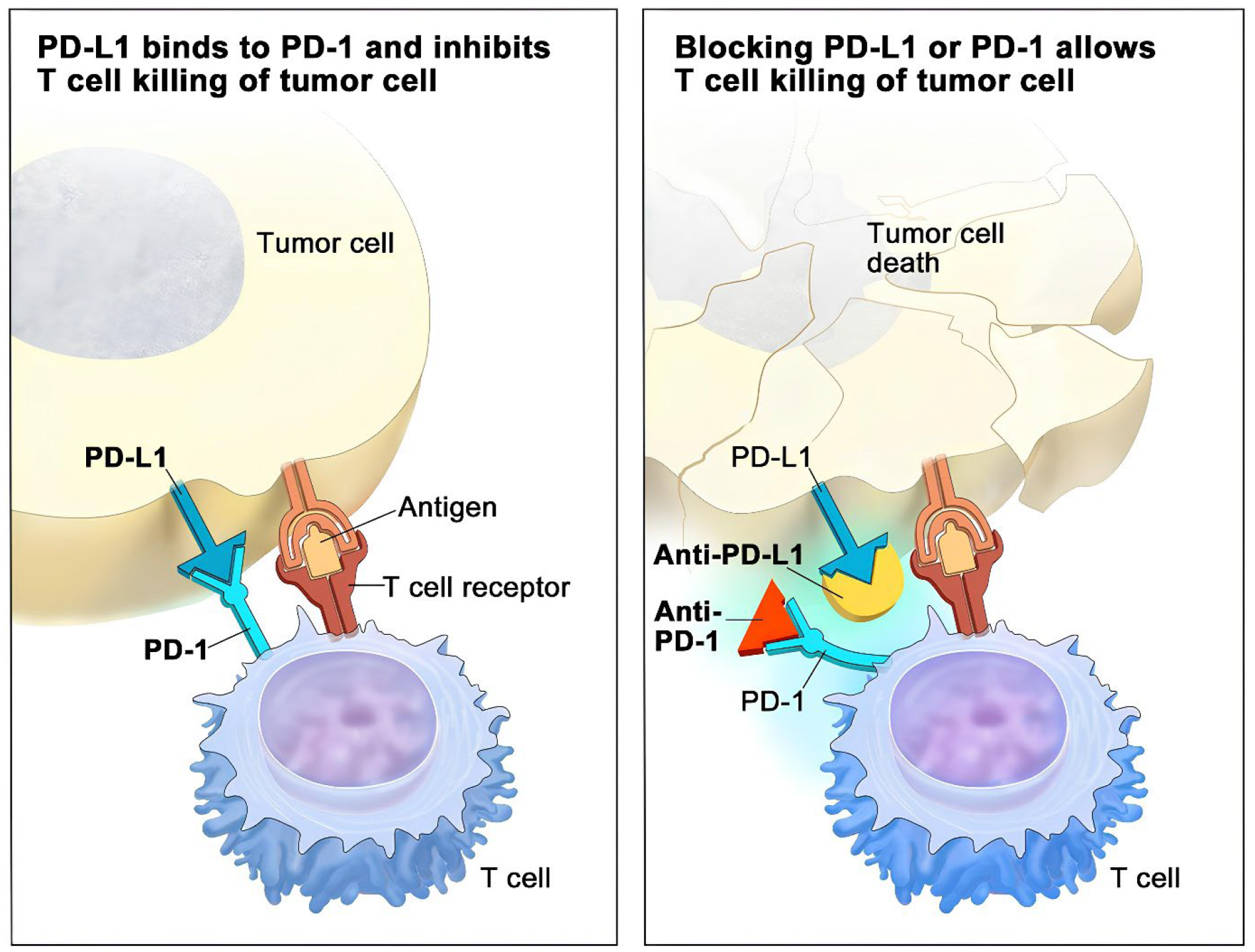

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer treatment by engaging the immune system into identifying and wiping out the cancer cells. It has been considered that the blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions is of paramount importance during this process since it abrogates the inhibitory signals that otherwise reign in the T-cell response against tumors. Small study based on multicenter phase 1 trial showcased that application of an anti-PD-L1 antibody leads to the long-term regression of the tumour mass in most of the advanced cancer patients as evidenced by the objective response that varies between 6% to 17% [

31]. The historical development of ICI describes a gradual step up from the first approval of anti-CTLA-4 for melanoma to the development of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. These ICIs have been described to wield stunning effectiveness across assorted cancers. Nonetheless, the review highlights a significant challenge: therapeutic failure, resistance to ICIs means that the number of patients who can obtain a long-lasting therapeutic benefit remains limited. Understanding the nature of this resistance is critical for modulating treatment regimes, mechanisms involved in the development of this resistance remains to be characterised. For example, present clinical trials such as KEYNOTE-649 are aimed at studying combined therapeutic approaches that potentiate PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition to further enhance survival status of the patients [

18]. A comprehensive understanding of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is crucial for the design of cancer immunotherapies. There is strong evidence that suggests this pathway as an important way through which tumors are shielded from immune recognition. The presence of the PD-L1 protein on tumor cells can inhibit T-cells leading to an immune response tolerant checkpoint with certain carcinogenesis [

32]. As highlighted by findings from this review, it is important that the treatment of this axis calls for new strategies; especially within highly metabolic cancer types such as TNBC. Integrating PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with other drugs, including MEK inhibitors, increases the assumption that the treatment efficiency and survival rates of the patients will be boosted [

33]. Combination strategies have been summarized effectively in the

Figure 3 below. And there is a new triple regimen of camrelizumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, apatinib, a newly-approved angiogenesis inhibitor and fuzuloparib, a newly-formulated PARP inhibitor has recently exhibited acceptable safety and preliminary antitumor efficacy in TNBC [

34]. The combination of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with angiogenesis inhibitors has also demonstrated activity in third-line therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), third and later lines in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and in endometrial cancer (EC). Furthermore, combining ICIs with angiogenin inhibitors and chemotherapy might overcome the problems which NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations may encounter [

35]. The FDA has approved the association of the PD-L1 inhibitors with BRAF-MEK inhibitors for the melanoma of the advanced stage with BRAFV600 [

36]. Moreover, adding the use of PD-L1 inhibitors with T-DM1 is favourable among patients with HER2-positive, PD-L1 positive advanced BC [

37]. It Also has clinically useful results when administrated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and PARP inhibitors in breast cancer patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations and ovarian cancer (OC) [

38].

There is the understanding of the TMB and PD-L1 as predictive markers of ICI treatment in many papers nowadays. TMB is associated with better clinical results and lasting clinical benefits derived from PD-1/PD-L1 agents [

54]. Consequently, these discoveries suggest that TMB and PD-L1 expression should complement the choice of predictive models to improve patient-selection in routine care. The relevance for trials such as KEYNOTE-649 is significant since it sets out the steps for selecting out the patients who are most likely to derive advantage from these advanced treatment methods. Also, the combination with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and ibrutinib also suggests another direction in intensification of antitumor immune reactions (source not provided). These combinations might enhance the outcomes in various kind of cancers because the mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade are also in agreement. The emerging data suggest that further study of the factors and pathways affecting the resistance mechanisms that might impair antigen presentation by HLA Class I molecules will limit the efficacy of ICIs [

55]. However, there remain many unknowns in this area of study including issues of the working of resistance and selecting the right patient reward profiles for different ICI treatments. Future work should focus on a better understanding of Factors dependent on tumor characteristics and immune milieu and their impact on treatment outcomes. This involves examining utilization in prognostication and treatment planning for Neoadjuvant treatment of cancer types such as Triple Negative Breast Cancer plus looking for biomarkers that may be used to forecast combination therapy reaction [

56].

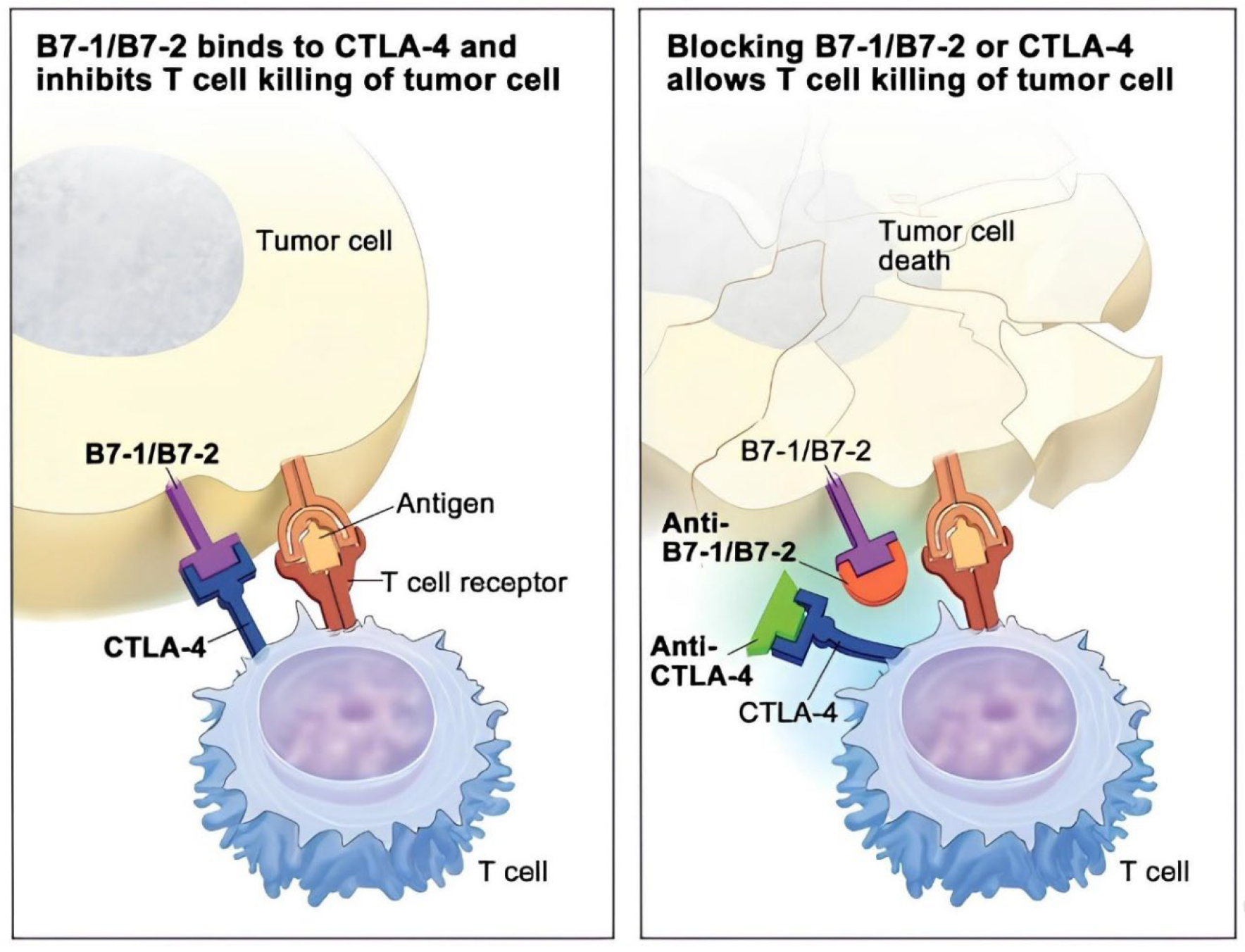

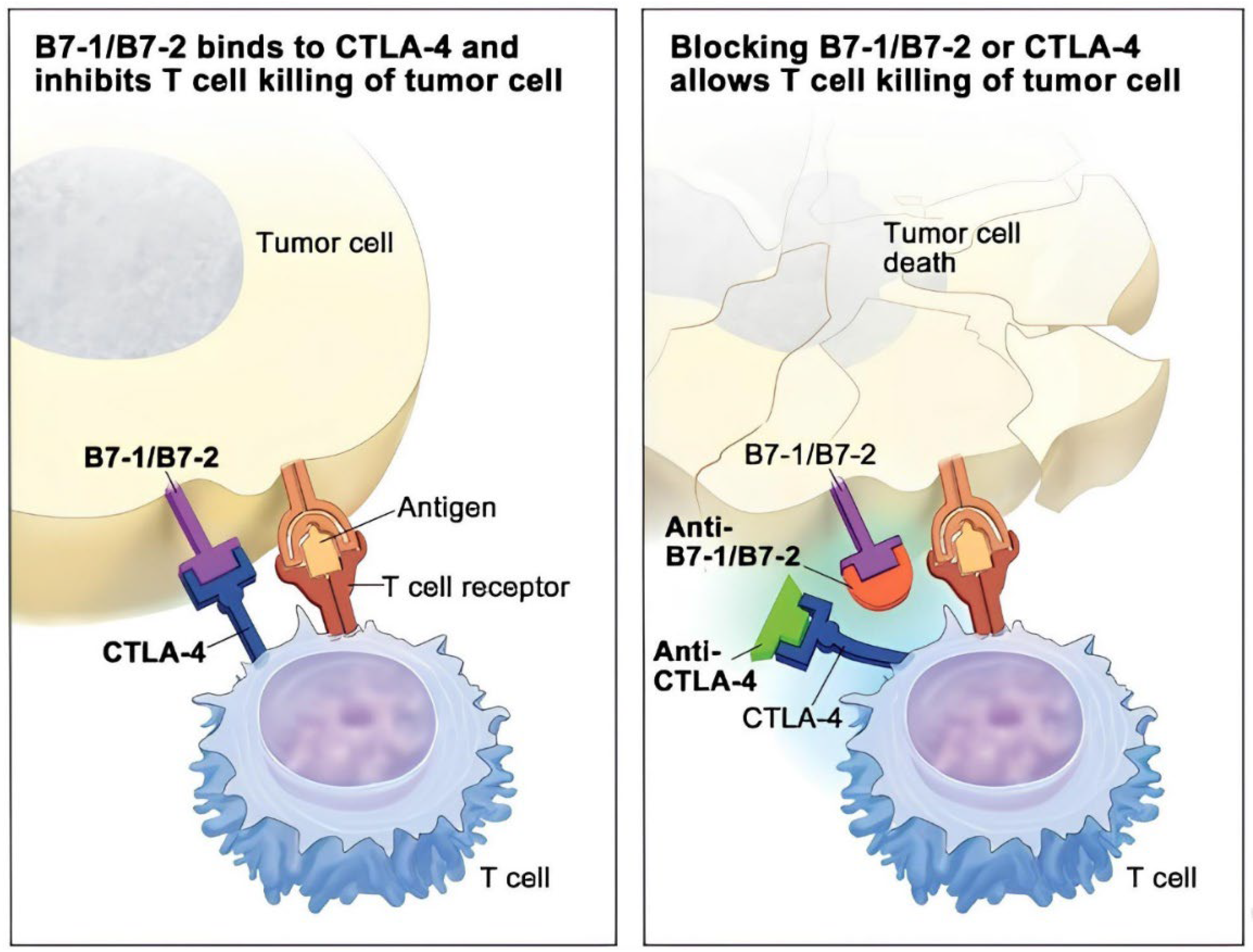

4.1.1. CTLA-4 Inhibitors

Anti-CTLA-4 like ipilimumab is a major innovation in cancer immunotherapy mainly directed at reversing the immune suppression that tumors promote. Blockade of CTLA-4, a coinhibitory receptor that negatively controls T cell activation, improves antitumor T cell activity for which it is essential to obtain lasting effects in various types of tumors [

57]. Besides, it helps the immune system to identify the tumor cell and target it; at the same time, it underlines the immunological setting in cancer therapy. Extending their scope, current papers have also discussed the impact of gut microbiome on CTLA-4 inhibitors. For example, particular class of Bacteroides has been shown to enhance antitumor effect and therefore, the authors contend that microbiota heavily influence immune reactions during CTLA-4 blockade [

58]. This discovery may open up avenues for microbiome-targeted treatments that would help to make CTLA-4 inhibitors more effective, while ushering in a new era of individual immunotherapy tailored to a patient’s microbiome.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of CTLA-4 inhibitors is tightly associated with mutations in tumor-related genes. Thus, a higher mutational burden has been shown to be associated with positive outcomes after treatment with CTLA-4 blockade, so it again became quite clear that comprehensive molecular profiling of tumors is critical to understanding the mechanisms underlying patients’ responses [

59].

Figure 4: Illustrates the nature of action of CTLA-4 inhibitors. Tumor cells express B7-1/B7-2, which bind to CTLA-4 on T cells, blocking their ability to kill the tumor cells (left). By inhibiting the effective interaction of B7-1/B7-2 using a CTLA-4 inhibitor, T cells can no longer bind to the now free CTLA-4 receptors, enabling them to kill the tumor cells (right). CTLA-4 = cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4.

However, like the other immunotherapy strategies, CTLA-4 inhibitors cannot be completely free from the immune-related toxicities; for example, the colitis can be potentially lethal. For, the timing and type of these side effects need to be understood so that patient safety can be addressed while achieving optimum therapeutic gain [

60]. Special emphasis should be placed on assessing first signs of toxity in patients treated with combination therapies, including CTLA-4 blockade, as such combinations may increase toxicity. Another layer of complexity is the tumor microenvironment because factors such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells can also represent a target for trying to overcome the resistance related to CTLA-4 therapies [

61]. This resistance highlighted the fact that combined state approach should be used targeting both CTLA-4 and MDSCs which may improve the therapeutic efficacy and the antitumor immune response. Recent improvement in cancer immunotherapy using CTLA-4 inhibitors has seen FDA approval of many monoclonal antibodies for the inhibition of CTLA-4 but there remain issues concerning patient response. An urgent requirement has been drilled to biomarkers that would help in predicting the therapy outcomes of these types of treatment hence underlining the fact that immune response to CTLA-4 blockade is nonlinear and there is therefore need for more research on probable factors that determine the immune response to the therapies [

62]. The use of CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibitors has also received attention because these agents may have synergistic effects. Whereas CTLA-4 blockade promotes T cell activation and proliferation, the add-on effect of PD-1 blockade may intensify the antitumor immunity, and therefore combining these targets would result in improved immune effector function against the tumor [

62].

4.1.2. PD-1 Inhibitors

Pembrolizumab and nivolumab, the PD-1 inhibitors, have been at the forefront of immunotherapy for cancer and NSCLC in the current world. These agents grouped according to their mechanism-label exert effectiveness based on genomic features, especially TMB. A positive correlation between TMB and response to PD-1 blockade is reported by Rizvi et al. (2015) where it showed that the higher the mutations, the more responsive the tumor is likely to be to the inhibitor. This work focus on the application of the genomic markers to the formation of the effective slug management plan at the treatment of Oncology patients with the reference to the peculiarities of the tumor. Moreover, neoantigens and T cell responses detected in the PD-1 treated patients suggest that these inhibitors act not only on the tumor cells, but also augment the immune system capabilities of cancer elimination [

63].

The findings of genomic determination are further supported in subsequent studies and depict the molecular smoking index as well as DNA repair pathway mutations as the important factors that predict the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors (Rizvi et al., 2015). This therefore supports the view that an understanding of a patient’s polygenic profile is necessary when administering PD-1 therapy in the clinical setting [

63]. Other than genomic inputs, gut microbiome has been identified as a key area of interest in terms of PD-1 inhibitors. Routy et al., (2018) have explained how, through the destruction of immune regulatory microbiota in the gut, the use of antibiotics is capable of worsening treatment results. Some bacterial species like Akkermansia muciniphila are known for courses strong correlation with therapy outcome with PD-1. Thus, these results do point towards the fact that a healthy gut microbiome could perhaps be necessary to achieve optimal results from PD-1 inhibitors, and hence opens a new direction for influencing treatment responses with microbiota modulation [

64].

Figure 5: Illustrates the targets of inhibition by PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The PD-L1 receptor is expressed on tumor cells; it latches onto the PD-1 receptor on T cells, which in turn prevents them from killing tumor cells (left). Anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors occupy PD-L1 and block it from binding to PD-1, thus freeing T cells to kill cancer cells (right). PD-1 is an abbreviation for programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, stands for programmed cell death ligand 1.

The action of PD-1 inhibitors continues to be discussed in the literature with emphasis on the functions of PD-1 and CTLA-4 as immune check points according to Buchbinder and Desai (2016). This blockade can greatly promote specific anti-tumor immunity, which represents a major shift in cancer therapy strategies. That early and late phases of immune response regulation are distinct and modulated by CTLA-4 and PD-1 offers important lessons in harnessing these agents for immunotherapies and combinations that yield maximum benefit to patients [

65]. However, only a few questions arise related to the restrictions on the use of PD-1 therapy and the problems with its effectiveness. There are some aspects which have been found to be linked to hyperprogressive disease (HPD) related to PD-1 inhibitors, important questions arise for choosing the patients and the screening analysis during the treatment. HPD is the proof of the need for further investigation and the constant development of effective treatment methods as well as prevention of essential adverse effects responsible for the decrease in therapeutic outcomes [

66]. However, the knowledge of safety profiles of PD-1 inhibitors is crucial for patients’ management as well. Side effects of these therapies may be different meaning that the treatment plans used in their management and treatment should be made to fit everyone. The systematic review of adverse events focuses on the comparison of the therapeutic effectiveness of PD-1 inhibitors with possible side effects [

66].

4.1.3. PD-L1 Inhibitors

PD-L1 inhibitors are the major subtype of ICPs that have significantly contributed to cancer immunotherapy, especially through immune checkpoint blockade, targeted at improving recognition of the tumour cells by the immune system. The exact mode of action of these inhibitors, including both anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies, relates to the regulation of the relationship between immune and cancer cells toward reversal of the immunosuppressive effects elicited by tumors. In this regard, clinical trials have established that although these inhibitors induce substantial antitumor outcomes, are usually associated with subtype specificity. This could be because PD-L1 is expressed in a variable way within the tumoral microenvironment implying that there is still a lot to learn about the actual work of PD-L1 in immune escape [

66]. Subsequent analysis has brought into focus the role of predictive biomarkers like TMB and the extent of PD-L1 expression in defining patient outcomes to PD-L1 inhibitors especially in Advanced NSCLC. It is found that TMB increases, clinical benefit enhances and therefore it can be suggested that TMB should be added into PD-L1 based models for selecting patients that will benefit from immunotherapy [

54]. The requirement for such case-based approaches is further compounded by newly identified worst-case scenario called hyperprogressive disease (HPD) where some patients witness an increased rate of tumor growth after receiving PD-L1 inhibitors. This raises the need for proper selection of patients especially the elderly for this treatment and close follow up on any of the patient’s condition [

67].

In this regard,

Figure 6 shows the types of immune limiting proteins; PD-L1, which is present on tumor cells and the PD-1 on T cells. PD-L1 forms a complex with PD-1, which inhibits T cell ability to kill tumor cells within the body (left panel). When this interaction is impaired by immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1), T cells can once again function to kill tumor cells

Furthermore, there are concern on the safety of PD-L1 inhibitors regarding their therapeutic use in the clinic. Compared to the other PD-L1 inhibitors, systematic reviews have revealed that there is inconsistency on the distributions of treatment-related AEs and thus, the need to conduct safety analysis continually to assist the clinicians in choosing the suitable drugs [

68]. The results indicate that most PD-L1 inhibitors possess favourable risk profile major types of adverse effects, thus, more studies are needed with relation to the individual cancers and agents associated with efficacy and safety. Subsequent meta-analysis studies have also supported the use of PD-L1 inhibitors irrespective of PD-L1 expression level a fact that contradicts prior belief that PD-L1 levels should be the basis for treatment choice. The body of knowledge indicates that these therapies could offer significant survival gains; thereby, there should be increased utilization in practice not based on this biomarker [

69]. This inevitably creates questions about the interaction of PD-L1 inhibitors with other therapeutic schemes, including combination treatment regimens that can potentially improve overall outcomes. In our view, one of the exciting areas of investigation concerns the use of PD-L1 inhibitors in conjunction with other modalities of treatment including, for example, IL-6 blockade, especially in difficult to treat cancers including PDAC. Previous research shows that such combinations may enhance the antitumor responses; therefore, the optimization of multiple modality treatment approaches may augment the efficacy features of PD-L1 inhibitors [

70].

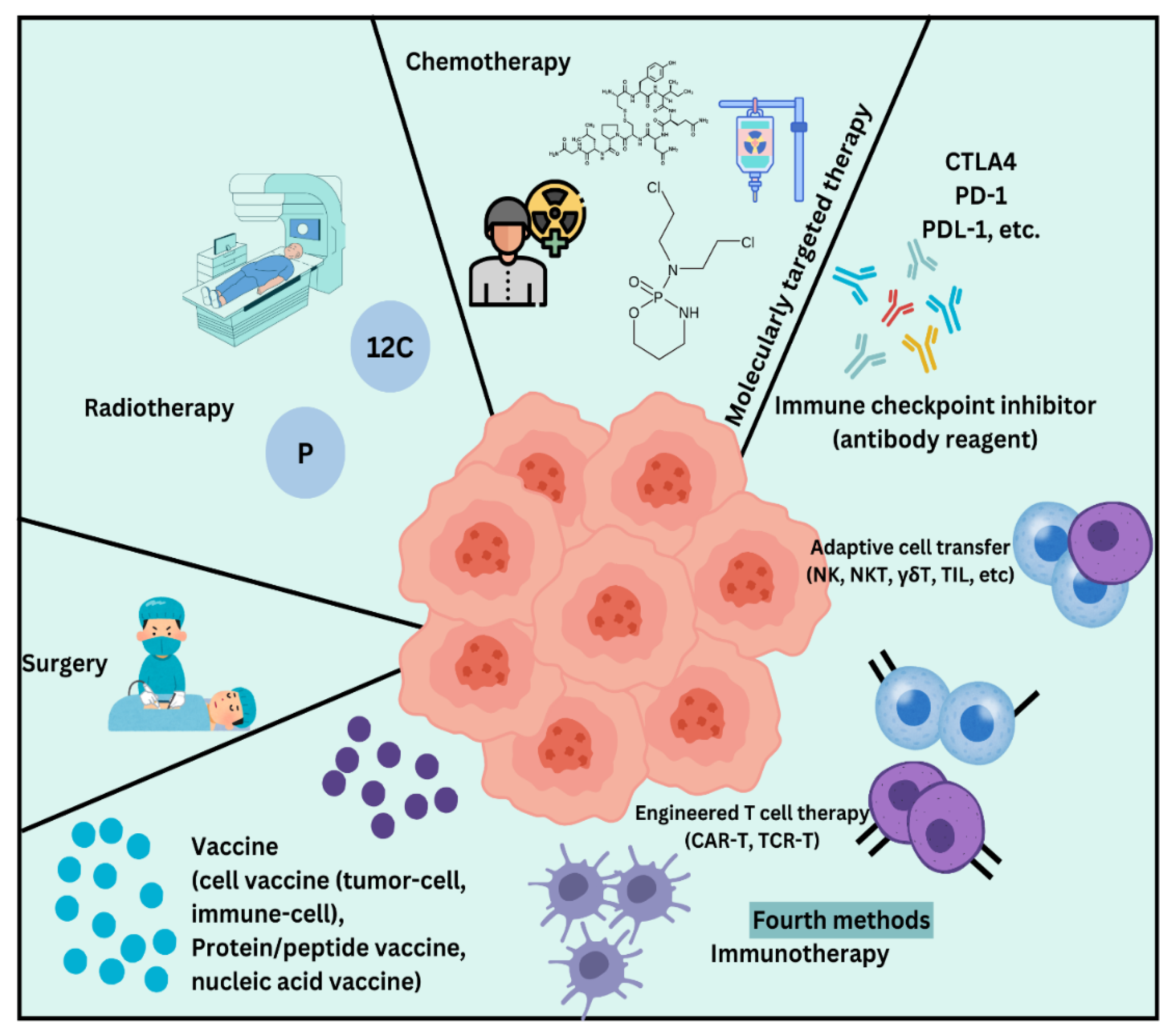

4.2. Conventional Therapy

Conventional therapy in cancer treatment primarily encompasses three main modalities: includes surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. These approaches have been standard for oncology therapy for many years and are typically used concurrently in order to improve effectiveness against tumors.[

71]. Surgery is often the initial approach assuming the tumors are localized, and they mostly are initially. The surgery for cancer aims at eradicating all the tumor mass while also taking a thin margin of healthy tissues in a bid to remove all cancer cells. Surgery is especially beneficial in stage I cancers where tumour removal is likely to remove the disease completely [

72]. But while chemotherapy relies on agents which are toxic to cancerous tissues and cells, the drugs used in chemotherapy are those that selectively target and destroy rapidly dividing cells. This treatment can be done orally or thru injection and is done either as a primary treatment or an additional treatment after surgery to eradicate cancer cells not captured by surgery [

73].

Even though, chemotherapy is effective in reducing the size of a tumour and increasing the prognosis and survival times and that it often has complications that affect the normal cells in the body such as causing nausea, fatigue and infections. In addition, challenges that come with treatment, for instance, drug resistance can be quite definitive [

74,

75]. Radiation therapy used ionizing energy, in the form of rays or particles, including X-rays to destroy cancer cells. There are some types of cancer which are confined, and the rays can be accurately aimed at the affected area. Radiation can be as an initial modal and together with surgeries and/or chemotherapy. However, like chemotherapy, it can also impact other parts of body and healthy cells which cause varied side effects. [

76,

77].

Figure 7 illustrates an overview of conventional and recent advancements in cancer treatment methods, highlighting surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy as key approaches in combating cancer.Over the past few years, there is an increased focus toward combination of focused therapies along with the immunotherapies all along with the conventional treatment plans. These modern methods try to pinpoint cancer cells or improve the body’s ability to fight tumors, thereby causing less damage to healthy cells than conventional treatment. However, conventional therapies continue to be important parts of cancer management because they form a solid foundation on which more recent approaches are based [

78].

5. Cancer Vaccines

The invention of vaccines has given a vast chance for eradication or controlling of infectious diseases, first known vaccine ever even was created by Edward Jenner in 1796 based on cowpox and protecting against smallpox. In time, vaccines were used in the treating of other illnesses, cancer included [

79]. The first type of cancer vaccines based on tumor cells and lysates appeared in 1980 targeting colorectal cancer using autologous tumor cells. The turning point came with the discovery in early 1990s of a new melanoma-associated antigen, bringing focus to development of tumor antigens for vaccines [

80]. A major break-through was achieved in 2010 when Sipuleucel-T dendritic cell-based cancer vaccine was successfully used to manage prostate cancer and there was hope in the field of cancer vaccines. The current COVID-19 vaccination has also advanced great progress in the innovation of cancer vaccines [

81]. These vaccines mainly use a concept of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) to work on the immune system and given an idea to make both the cellular as well as humeral immunity for the rejection of tumor formation and abolishing cancer cells. Now, this approach mostly presented in cancer vaccines that are still at the preclinical and clinical level and therefore require further definition of more specific antigens and more effective development platforms [

82]. Cancer vaccines differ from conventional vaccines in that their major purpose is to elicit selective immune reactions against cancer cells without the need for targeting usually foreign organisms. Currently, there are only two virus-associated cancer preventive vaccines approved by the FDA: the Hepatitis B vaccine and the HPV vaccine [

83]. In contrast to most typical immunogens where the antigens are exogenous, tumor antigens are endogenous and thus usually weak self-antigens which present low immunogenicity thereby complicating efforts to elicit immune responses. Allof these vaccines, but particularly the cancer vaccines, mainly elicit affinity for CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes and not the more familiar antibodies that are evoked by traditional vaccines [

84].

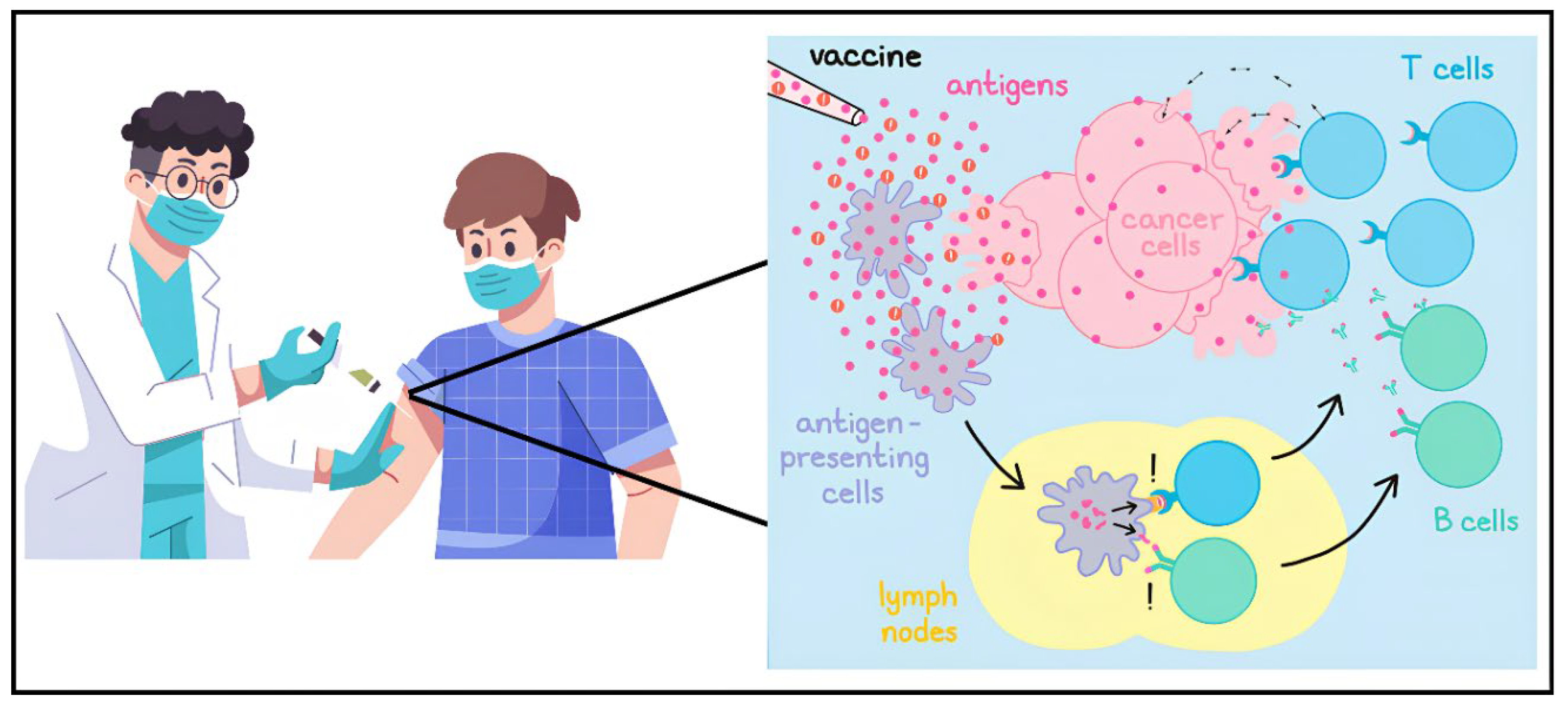

5.1. Mechanism of Cancer Vaccines

The adaptation of the current approaches and effectiveness of the cancer vaccines rests in a manner that boosts the immune system recognition of cancer. New developments have enlightened about developing approaches that can help in eradicating currently prevailing difficulties, especially those of tumor stroma and attributes of cancer stem cell.

Cancer vaccines work on a very strategic basis on the premise to elicit immune response against tumor cells through usage of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) or tumor specific antigens (TSAs). These antigens are first transported to antigen-presenting-cells (APCs) for instance dendritic cells by way of a peptide, protein or any whole tumour cells. After the APCs capture the antigens they break them down into fragments and display them on their surface by means of MHC [

85]. This presentation is important for T cell activation because T cells express their TCRs on their surface to identify these MHC-antigen overloading. Illustrated above are the interactions between T cells and the APCCs for the activation of T cells to be effective, T cell needs to recognize the MHC-antigen complex as well as receive co-stimulatory signals [

86]. Once fully activated CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are prepared to recognize and kill cancer cells exhibiting the same antigens [

87]. Similarly, helper CD4 + T cells are efficient in inducing a stronger anti tumor immune response via stimulation of cytokines that support the growth and differentiation of CTLs and in assisting B cells to produce antibodies against tumor antigen [

87]. To boost this reply, numerous cancer vaccines contain adjuvants – molecules that can boost up immuno-response by engaging additional APCs and by additionally raising co-stimulative signals. For example, certain vaccines organise Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists to stimulate innate immune signalling and overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines which reinforce adaptive immunity [

88]. However, the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) might still pose an obstruction to cancer vaccines; this may include situation where regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells recapitulate T cells [

89]. To overcome these challenges, scientists are considering using cancer vaccines together with immune checkpoint inhibitors that are molecules blocking the negative signals on the T cells (PD-1/PD-L1, or CTLA-4) [

90]. Some of these new advancements in PM have also been spurred by the development of neoantigen vaccines that are designed and developed for a particular tumor type identified in a patient to provoke a strong immune response and subsequent high clinical effectiveness [

91]. In aggregate, cancer vaccines are designed to produce an enduring anti-tumor immunity that can manage or eradicate tumors over a period, which demonstrates a shift in the immunotherapy of cancer [

92].

Figure 8 shows Cancer vaccines utilize antigens and adjuvants to activate the immune system, teaching it to identify and eliminate harmful cells.

6. Biomarkers and Patient Selection

Circulating biomarkers are vital in oncology, mainly for enrichment in patient selection and treatment strategies [

93]. These are quantitative expressions of biologic states or conditions, which may be present in blood or tissue and can give useful information on the cancer in an individual. Two of the prominent biomarkers identified are PD-L1 and MSI, the latter of which have become highly important predictors for directing therapies for several cancers, such as stomach cancers [

94].

Another typical biomarker is PD-L1 expression, and the value of such biomarkers relies in utilizing such characteristics of the tumor to guide clinicians. PD-L1 is an actual protein which can be over-expressed on the tumor cells surface, and which tells how the cancer may communicate with the immune system [

95]. In cases where the PD-L1 proteins is overexpressed, there are immunostimulatory drugs, generally known as checkpoint inhibitors, to enhance immunity against such tumors [

96]. For instance, sensitivity of antitumor immune response in stomach cancer patients with high PD-L1 may indicate better result from therapies like pembrolizumab or nivolumab targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. This understanding enables oncologists to customise treatment regimens according to the chances of response to immunotherapy and hence enhance the quality of their results while reducing on adverse effects from other unproductive therapies [

97].

Secondly, MSI status is another important prognostic biomarker for patient selection in treatment. MSI stands for Mutator phenotype associated with defects in the DNA mismatch repair system, that is a state of genetic hypermutability [

98]. Cancers that are classified as MSI-high for their high level of MSI are predicted to undergo better Immunotherapy because of the high mutation loads which create neoantigens capable of triggering immune activity. In stomach cancer, MSI status can be expressed to inform treatment directions that prioritize immunotherapy as more effective than usual chemotherapy. For instance, MSI-high tumors should be treated with pembrolizumab or other checkpoint inhibitors, but MSS tumors should be treated differently [

99].

A biomarker test can be performed on different tumour samples through different techniques including immunohistochemistry, next generation sequencing, or polymerase chain reaction among others. These tests can find targetable mutation or protein expression that can inform therapy [

100]. For example, having a biomarker of HER2 amplification following a surgery of stomach cancer may mean that this patient may require a treatment such as trastuzumab, which totally changes the treatment options for this patient [

101]. In addition, biomarkers help also in choosing the right treatment but also in anticipating the patient’s response and assessing the impact of the treatment. With the help of biomarkers that include PD-L1 and MSI status, clinicians learn how well a particular patient will likely to respond to the treatments recommended [

102]. This is a wonderful feature; it empowered the opportunity to modify the therapy upon real-time evaluations of treatment efficacy. The development of biomarker research has also given the world tumor-agnostic treatment—medical treatments for various cancer types based on molecular markers regardless of their origin [

103]. This change in thinking focuses upon biomarkers over traditional dichotomies and offers new possibilities for patients with fewer choices before. For instance, drugs developed to act on certain mutations the BRAF or NTRK can be used in many forms of cancer if these mutations exist the cancer’s origin notwithstanding [

104]. However, there are still several issues identified for the practical application of biomarker testing in clinical practice. Contamination and novel testing suggest that the oncologist should not only be well-informed of new biomarkers and tests are relevant to treatment protocols. Finally, further differences between primary tumor and metastases with respect to biomarkers exist, which can make therapy planning more challenging; For this reason, re-biopsies may sometimes be required for proper evaluation [

105].

The

Table 2 presented outlines various types of biomarkers relevant to stomach cancer, categorized into four main groups: Blood and protein biomarkers include classical tumor markers, circulating biomarkers, genetic and epicongenetic biomarkers, as well as other novel biomarkers. Every row gives information about biomarkers, their usage in clinic, and impact on stomach cancer.

7. Challenges in Immunotherapy for Gastric Cancer

7.1. Variability in Patient Responses to Immunotherapies

This study identified several limitations in immunotherapy for gastric cancer; however, one of the biggest concerns is the heterogeneity of patient responses. Such variability could be due to genetic factors, tumor related factors or even due to tumor microenvironment. For example, van der Laak et al. reported that TMB can vary among individual patients and is generally predictive of response to ICIs [

124]. It has been assumed that high TMB is associated with better outcomes because the likelihood for neoantigen generation is high; however, the relationship is not as direct. Current research has revealed that the proportion of high ITH in tumor samples implies that even high TMB can lead to poor response due to other factors such as ITH and immune-suppressive cells can exist in TME [

125].

Furthermore, the molecules including the program death-1 (PD-1) or the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) can regulate issue immune responses. These molecules can be upregulated or downregulated and can have quite different levels between patients and, sometimes, between different parts of the same tumor [

126]. This variability also threatens the ability to predict which patients will benefit from ICIs. Moreover, the identification of definite molecular profiles that could accurately be used to predict responses to treatments remains a challenge [

127]. Although many companies and scientists have been looking for such predictive biomarkers for years, none of them has been validated as ready-to-use means of choosing appropriate participants in immunotherapy; As a result, many patients receive immunotherapy that is suitable only partially or even not suitable at all [

128].

7.2. Immune Evasion and Tumor Heterogeneity

The second fundamental challenge has to do with aspects of immune escape strategies deployed by tumors. Tumour cells have developed various mechanisms by which they can avoid being recognised and killed by the immune system. The gastric cancer TME not only progresses over time but also changes in tumour immunosuppressive properties and resistance to therapy [

129].

Tumor heterogeneity worsens this scenario even further. Preclinical data highlight that gastric tumors are highly diverse within a tumor mass with genetic and immune cell subpopulations. That is why some tumour regions may have more immune cells and vice versa, as well as there may be different reactions on a particular treatment [

130]. For instance, while some subclones that arise from the same tumor mass may produce immune checkpoint ligands at high density, others may produce little to none, leaving immune presence in the tumor piecemeal. Further, the process of clonal evolution can lead to outcome-determining clones with genetically ingrained capacity for immune escape and therefore constitute a genuine threat to immunotherapeutic efficacy.

The interactions between ITH and TMB are also determinants of treatment outcomes. Although a high TMB implies that more likely neoantigens are produced that could be targeted by an immune response, the heterogeneous cancer subclones may be represented by clones dominating the tumor that are poorly recognized by immune system due to various mechanisms including the loss of antigen-processing machinery or the downregulation of neoantigens. This complexity means that it is necessary to gain a deeper insight about how these factors jointly and severally impinge on patients [

131].

7.3. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events

Another relevant factor in immunotherapy is immune related adverse events or irAES. As immunotherapies can inspire vigorous reactions against tumors, they can also cause reactivity to normal tissues with broad-range dangerous outcomes ranging from mild manifestations to life-threatening conditions [

132]. The common organ-specific irAEs are dermatological reactions, colitis, hepatitis, and endocrinopathies5. These events may occur randomly and with varying severity in some patients, depending, inter alia, on genetic factors and presence of other diseases. The management of irAEs is crucial to avoid hazardous conditions to the patient while offering the highest chance of benefit from the treatment. Perceived consequences of immunotherapeutic agents commonly act as barriers to early recognition and intervention; however, increased knowledge concerning the side effects of such agents is vital. Further, the ability to deliver a good cancer outcome while avoiding or at least limiting irAEs presents a unique challenge to oncologists. At per protocol doses some severe adverse events may require dose modification or temporary withdrawal of the therapy but this does not necessarily imply the abandonment of the protocol treatment [

133].

8. Conclusion

The paper on Innovative Immunotherapeutic Strategies for Gastric Cancer underscores the importance of developing better therapies because the disease remains fatal and experiencing changes in its epidemiology. Stomach cancer according to the global cancer statistics is the 5th most common cancer, and the 3rd most frequent cause of cancer death worldwide and therefore requires new strategies to control its progression. The present review comprehensively updates the author’s previous work, also reviewing recent literature on immunotherapy and highlighting the value of exosomes in tumor microenvironment and immune regulation particularly in cancer. Building on studies conducted over the last 15 years, it clarifies how microRNA on exosome surface may modulate the neoplastic phenotype and immune system to make exosomes attractive targets for diagnosis and treatment. Since the discovery of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) constitutes a new approach to cancer therapy, excellent advancements have been made; however, there remains the problem of therapeutic resistance. For this reason, composing a more helpful treatment performance, it is vital to grasp the principles of this kind of opposition. The review specifies that immunotherapy should be combined with nutrition changes, genetic testing, as well as prevention and early diagnostics campaigns and programs. Additionally, variation in the distributions of the risk factors for gastric cancer also point to the need for targeted programs towards differing geographical location. Moreover, concern with the ever-shifting contours of gastric cancer treatment, exosomal biology and its application in immunotherapeutic approach remains a focus of active research. The current broad study not only emphasizes the possibility of exosomes in improving the efficacy of the treatment but also highlights the need for cooperation between researchers, doctors, as well as the ministry of health in tackling the prevailing health calamity. In this respect, these insights are envisaged to create the foundation for enhanced survival and higher quality of life of patients with gastric cancer.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation List

GC: Gastric Cancer

GISTs: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

M: I: Mortality-to-Incidence ratio

CAFs: Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts

ICIs: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

TME: Tumor Microenvironment

TAMs: Tumor-Associated Macrophages

MDSCs: Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

CSF1R: Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor

PD-1: Programmed Cell Death Protein 1

PD-L1: Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1

TNBC: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

RCC: Renal Cell Carcinoma

EC: Endometrial CancerReferences

References

- S. K. R. Mukkamalla, A. Recio-Boiles, and H. M. Babiker, “Gastric Cancer,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024. Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459142/.

- C. De Martel, D. Forman, and M. Plummer, “Gastric Cancer,” Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 219–240, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Karimi, F. Islami, S. Anandasabapathy, N. D. Freedman, and F. Kamangar, “Gastric Cancer: Descriptive Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Screening, and Prevention,” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 700–713, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Rawla and A. Barsouk, “Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention,” pg, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 26–38, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Sitarz, M. Skierucha, J. Mielko, J. Offerhaus, R. Maciejewski, and W. Polkowski, “Gastric cancer: epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment,” CMAR, vol. Volume 10, pp. 239–248, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Morgan et al., “The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020–40: A population-based modelling study,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 47, p. 101404, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. C. S. Wong et al., “Global Incidence and Mortality of Gastric Cancer, 1980-2018,” JAMA Network Open, vol. 4, no. 7, p. e2118457, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Karimi, F. Islami, S. Anandasabapathy, N. D. Freedman, and F. Kamangar, “Gastric Cancer: Descriptive Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Screening, and Prevention,” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 700–713, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- J.-L. Lin et al., “Global incidence and mortality trends of gastric cancer and predicted mortality of gastric cancer by 2035,” BMC Public Health, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 1763, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Miller et al., “Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019,” CA A Cancer J Clinicians, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 363–385, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Miller et al., “Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022,” CA A Cancer J Clinicians, vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 409–436, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Rugge, M. Fassan, and D. Y. Graham, “Epidemiology of Gastric Cancer,” in Gastric Cancer, V. E. Strong, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015, pp. 23–34. [CrossRef]

- A. Ferro et al., “Worldwide trends in gastric cancer mortality (1980–2011), with predictions to 2015, and incidence by subtype,” European Journal of Cancer, vol. 50, no. 7, pp. 1330–1344, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Machlowska, J. Baj, M. Sitarz, R. Maciejewski, and R. Sitarz, “Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies,” IJMS, vol. 21, no. 11, p. 4012, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu et al., “Morbidity and Mortality of Laparoscopic Versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” JCO, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 1350–1357, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Naran, T. Nundalall, S. Chetty, and S. Barth, “Principles of Immunotherapy: Implications for Treatment Strategies in Cancer and Infectious Diseases,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 9, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Hu et al., “The Research Progress of Antiangiogenic Therapy, Immune Therapy and Tumor Microenvironment,” Front. Immunol., vol. 13, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Bilotta, A. Antignani, and D. J. Fitzgerald, “Managing the TME to improve the efficacy of cancer therapy,” Front. Immunol., vol. 13, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Samstein et al., “Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types,” Nat Genet, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 202–206, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Ru et al., “TISIDB: an integrated repository portal for tumor–immune system interactions,” Bioinformatics, vol. 35, no. 20, pp. 4200–4202, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Bagchi, R. Yuan, and E. G. Engleman, “Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Cancer: Clinical Impact and Mechanisms of Response and Resistance,” Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 223–249, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Labani-Motlagh, M. Ashja-Mahdavi, and A. Loskog, “The Tumor Microenvironment: A Milieu Hindering and Obstructing Antitumor Immune Responses,” Front. Immunol., vol. 11, p. 940, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu et al., “CSF1/CSF1R Blockade Reprograms Tumor-Infiltrating Macrophages and Improves Response to T-cell Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer Models,” Cancer Research, vol. 74, no. 18, pp. 5057–5069, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Henke, R. Nandigama, and S. Ergün, “Extracellular Matrix in the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Impact on Cancer Therapy,” Front. Mol. Biosci., vol. 6, p. 160, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Mager et al., “Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy,” Science, vol. 369, no. 6510, pp. 1481–1489, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Kon and I. Benhar, “Immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations: Current efforts and important aspects for success,” Drug Resistance Updates, vol. 45, pp. 13–29, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Sobhani, D. R. Tardiel-Cyril, A. Davtyan, D. Generali, R. Roudi, and Y. Li, “CTLA-4 in Regulatory T Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy,” Cancers, vol. 13, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Tang et al., “The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in human cancers,” Front. Immunol., vol. 13, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Colligan, “Mitigating Myeloid-Driven Pathways of Immune Suppression to Enhance Cancer Immunotherapy Efficacy,” 2022.

- K. Guzik et al., “Development of the Inhibitors That Target the PD-1/PD-L1 Interaction—A Brief Look at Progress on Small Molecules, Peptides and Macrocycles,” Molecules, vol. 24, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Brahmer et al., “Safety and Activity of Anti–PD-L1 Antibody in Patients with Advanced Cancer,” N Engl J Med, vol. 366, no. 26, pp. 2455–2465, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. K. Dermani, P. Samadi, G. Rahmani, A. K. Kohlan, and R. Najafi, “PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint: Potential target for cancer therapy,” Journal of Cellular Physiology, vol. 234, no. 2, pp. 1313–1325, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Lai and A. Friedman, “Combination therapy for melanoma with BRAF/MEK inhibitor and immune checkpoint inhibitor: a mathematical model,” BMC Syst Biol, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 70, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang et al., “A phase Ib study of camrelizumab in combination with apatinib and fuzuloparib in patients with recurrent or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” BMC Med, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 321, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Dazio, S. Epistolio, M. Frattini, and P. Saletti, “Recent and Future Strategies to Overcome Resistance to Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 11, no. 24, Art. no. 24, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, X. Zhang, G. Wang, and X. Cui, “Triple Combination Therapy With PD-1/PD-L1, BRAF, and MEK Inhibitor for Stage III–IV Melanoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Front. Oncol., vol. 11, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Stein, O. Oluoha, K. Patel, and A. VanderWalde, “Precision Medicine in Oncology: A Review of Multi-Tumor Actionable Molecular Targets with an Emphasis on Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 11, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Musacchio et al., “Combining PARP inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade in ovarian cancer patients: a new perspective on the horizon?,” ESMO Open, vol. 7, no. 4, p. 100536, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Graziani, L. Lisi, L. Tentori, and P. Navarra, “Monoclonal Antibodies to CTLA-4 with Focus on Ipilimumab,” in Interaction of Immune and Cancer Cells, M. Klink and I. Szulc-Kielbik, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 295–350. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Lipson and C. G. Drake, “Ipilimumab: An Anti-CTLA-4 Antibody for Metastatic Melanoma,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 17, no. 22, pp. 6958–6962, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Rajan, C. Kim, C. R. Heery, U. Guha, and J. L. Gulley, “Nivolumab, anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody immunotherapy: Role in advanced cancers,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 2219–2231, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Massard et al., “Safety and Efficacy of Durvalumab (MEDI4736), an Anti–Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, in Patients With Advanced Urothelial Bladder Cancer,” JCO, vol. 34, no. 26, pp. 3119–3125, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Peters, K. M. Kerr, and R. Stahel, “PD-1 blockade in advanced NSCLC: A focus on pembrolizumab,” Cancer Treatment Reviews, vol. 62, pp. 39–49, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B.A. Inman, T. A. Longo, S. Ramalingam, and M. R. Harrison, “Atezolizumab: A PD-L1–Blocking Antibody for Bladder Cancer,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 1886–1890, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Teets, L. Pham, E. L. Tran, L. Hochmuth, and R. Deshmukh, “Avelumab: A Novel Anti-PD-L1 Agent in the Treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Urothelial Cell Carcinoma,” CRI, vol. 38, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Rath, A. Plangger, and G. Hamilton, “Non-small cell lung cancer-small cell lung cancer transformation as mechanism of resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer,” Cancer Drug Resistance, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 171, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Villani et al., “Cemiplimab for the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma,” Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 21–29, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Mirza et al., “Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 388, no. 23, pp. 2145–2158, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Patel et al., “FDA Approval Summary: Tremelimumab in Combination with Durvalumab for the Treatment of Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 269–273, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Burtness, “Toripalimab Yields ‘Striking’ PFS Improvement in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma.,” Cancer Network, p. NA-NA, Jan. 2024.

- H. S. Rugo et al., “Abemaciclib in combination with pembrolizumab for HR+, HER2− metastatic breast cancer: Phase 1b study,” npj Breast Cancer, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Deng, M. Huang, R. Deng, and J. Wang, “Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adrenal hypofunction and Psoriasisby induced by tislelizumab: A case report and review of literature,” Medicine, vol. 103, no. 12, p. e37562, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Reuss, L. Gosa, and S. V. Liu, “Antibody Drug Conjugates in Lung Cancer: State of the Current Therapeutic Landscape and Future Developments,” Clinical Lung Cancer, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 483–499, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Rizvi et al., “Molecular Determinants of Response to Anti–Programmed Cell Death (PD)-1 and Anti–Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Blockade in Patients With Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Profiled With Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing,” JCO, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 633–641, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Gettinger et al., “Impaired HLA Class I Antigen Processing and Presentation as a Mechanism of Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Lung Cancer,” Cancer Discovery, vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 1420–1435, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Sibaud, “Dermatologic Reactions to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Skin Toxicities and Immunotherapy,” Am J Clin Dermatol, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 345–361, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Ribas and J. D. Wolchok, “Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6382, pp. 1350–1355, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Vétizou et al., “Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota,” Science, vol. 350, no. 6264, pp. 1079–1084, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Van Allen et al., “Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma,” Science, vol. 350, no. 6257, pp. 207–211, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Y. Wang et al., “Fatal Toxic Effects Associated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” JAMA Oncol, vol. 4, no. 12, p. 1721, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Rowshanravan, N. Halliday, and D. M. Sansom, “CTLA-4: a moving target in immunotherapy,” Blood, vol. 131, no. 1, pp. 58–67, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Qin, L. Xu, M. Yi, S. Yu, K. Wu, and S. Luo, “Novel immune checkpoint targets: moving beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4,” Mol Cancer, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 155, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Rizvi et al., “Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer,” Science, vol. 348, no. 6230, pp. 124–128, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Routy et al., “Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6371, pp. 91–97, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. I. Buchbinder and A. Desai, “CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways: Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition,” American Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 98–106, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. O. Alsaab et al., “PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome,” Front. Pharmacol., vol. 8, p. 561, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Champiat et al., “Hyperprogressive Disease Is a New Pattern of Progression in Cancer Patients Treated by Anti-PD-1/PD-L1,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 1920–1928, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., “Treatment-Related Adverse Events of PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” JAMA Oncol, vol. 5, no. 7, p. 1008, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Yi, X. Zheng, M. Niu, S. Zhu, H. Ge, and K. Wu, “Combination strategies with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: current advances and future directions,” Mol Cancer, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 28, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Akinleye and Z. Rasool, “Immune checkpoint inhibitors of PD-L1 as cancer therapeutics,” J Hematol Oncol, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 92, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Debela et al., “New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives,” SAGE Open Medicine, vol. 9, p. 20503121211034366, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Goldhirsch et al., “Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013,” Annals of Oncology, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 2206–2223, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, P. W. Kantoff, R. Wooster, and O. C. Farokhzad, “Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 20–37, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Bukowski, M. Kciuk, and R. Kontek, “Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy,” IJMS, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 3233, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Jing et al., “Role of hypoxia in cancer therapy by regulating the tumor microenvironment,” Mol Cancer, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 157, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao et al., “Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy and Its Role in Overcoming Drug Resistance,” Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, vol. 7, p. 193, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Sun, Y. S. Zhang, B. Pang, D. C. Hyun, M. Yang, and Y. Xia, “Engineered Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy,” Angew Chem Int Ed, vol. 53, no. 46, pp. 12320–12364, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Anjum et al., “Emerging Applications of Nanotechnology in Healthcare Systems: Grand Challenges and Perspectives,” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 14, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. S. Moore, J. F. Seward, and J. M. Lane, “Smallpox,” Lancet, vol. 367, no. 9508, pp. 425–435, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Hoover, M. G. Surdyke, R. B. Dangel, L. C. Peters, and M. G. Hanna, “Prospectively randomized trial of adjuvant active-specific immunotherapy for human colorectal cancer,” Cancer, vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 1236–1243, Mar. 1985. [CrossRef]

- L. Miao, Y. Zhang, and L. Huang, “mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy,” Mol Cancer, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 41, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Saxena, S. H. van der Burg, C. J. M. Melief, and N. Bhardwaj, “Therapeutic cancer vaccines,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 360–378, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Le, D. M. Pardoll, and E. M. Jaffee, “Cellular Vaccine Approaches,” Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.), vol. 16, no. 4, p. 304, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Farhood, M. Najafi, and K. Mortezaee, “CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review,” J Cell Physiol, vol. 234, no. 6, pp. 8509–8521, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Fang et al., “Cancer Cell Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles for Anticancer Vaccination and Drug Delivery,” Nano Lett., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 2181–2188, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Yada, K. Nogami, K. Ogiwara, and M. Shima, “Activated prothrombin complex concentrate (APCC)-mediated activation of factor (F)VIII in mixtures of FVIII and APCC enhances hemostatic effectiveness,” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 902–910, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Kennedy and E. Celis, “Multiple roles for CD4+ T cells in anti-tumor immune responses,” Immunological Reviews, vol. 222, no. 1, pp. 129–144, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Rossella, M. Trovato, R. Manco, D. Luciana, and D. B. Piergiuseppe, “Exploiting viral sensing mediated by Toll-like receptors to design innovative vaccines,” NPJ Vaccines, vol. 6, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Asiry et al., “The Cancer Cell Dissemination Machinery as an Immunosuppressive Niche: A New Obstacle Towards the Era of Cancer Immunotherapy,” Front. Immunol., vol. 12, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Ott, F. S. Hodi, and C. Robert, “CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade: New Immunotherapeutic Modalities with Durable Clinical Benefit in Melanoma Patients,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 19, no. 19, pp. 5300–5309, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Hargrave, A. S. Mustafa, A. Hanif, J. H. Tunio, and S. N. M. Hanif, “Recent Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy with a Focus on FDA-Approved Vaccines and Neoantigen-Based Vaccines,” Vaccines, vol. 11, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Osipov, A. Murphy, and L. Zheng, “Chapter Two - From immune checkpoints to vaccines: The past, present and future of cancer immunotherapy,” in Advances in Cancer Research, vol. 143, X.-Y. Wang and P. B. Fisher, Eds., in Immunotherapy of Cancer, vol. 143. , Academic Press, 2019, pp. 63–144. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Danila, K. Pantel, M. Fleisher, and H. I. Scher, “Circulating Tumors Cells as Biomarkers: Progress Toward Biomarker Qualification,” The Cancer Journal, vol. 17, no. 6, p. 438, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Rizzo, A. D. Ricci, and G. Brandi, “PD-L1, TMB, MSI, and Other Predictors of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Biliary Tract Cancer,” Cancers, vol. 13, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Chae et al., “Biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Therapy in Non–Small-cell Lung Cancer: Is PD-L1 Expression a Good Marker for Patient Selection?,” Clinical Lung Cancer, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 350–361, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Li and H. Tian, “Development of small-molecule immune checkpoint inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1 as a new therapeutic strategy for tumour immunotherapy,” Journal of Drug Targeting, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 244–256, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Long et al., “PD-1/PD-L blockade in gastrointestinal cancers: lessons learned and the road toward precision immunotherapy,” J Hematol Oncol, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 146, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Mas-Ponte, M. McCullough, and F. Supek, “Spectrum of DNA mismatch repair failures viewed through the lens of cancer genomics and implications for therapy,” Clinical Science, vol. 136, no. 5, pp. 383–404, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Mardis, “Neoantigens and genome instability: impact on immunogenomic phenotypes and immunotherapy response,” Genome Med, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 71, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Shimozaki et al., “Concordance analysis of microsatellite instability status between polymerase chain reaction based testing and next generation sequencing for solid tumors,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 20003, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Gomez-Martín et al., “A critical review of HER2-positive gastric cancer evaluation and treatment: From trastuzumab, and beyond,” Cancer Letters, vol. 351, no. 1, pp. 30–40, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Duffy and J. Crown, “Biomarkers for Predicting Response to Immunotherapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Patients,” Clinical Chemistry, vol. 65, no. 10, pp. 1228–1238, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Riboldi, R. Orecchia, and G. Baroni, “Real-time tumour tracking in particle therapy: technological developments and future perspectives,” The Lancet Oncology, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. e383–e391, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Danesi et al., “Druggable targets meet oncogenic drivers: opportunities and limitations of target-based classification of tumors and the role of Molecular Tumor Boards,” ESMO Open, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 100040, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Sanchez and T. Bocklage, “Precision cytopathology: expanding opportunities for biomarker testing in cytopathology,” Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 95–115, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Łukaszewicz-Zając, S. Pączek, P. Muszyński, M. Kozłowski, and B. Mroczko, “Comparison between clinical significance of serum CXCL-8 and classical tumor markers in oesophageal cancer (OC) patients,” Clin Exp Med, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 191–199, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Roessler et al., “A Unique Metastasis Gene Signature Enables Prediction of Tumor Relapse in Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients,” Cancer Research, vol. 70, no. 24, pp. 10202–10212, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sun and N. Zhang, “Clinical evaluation of CEA, CA19-9, CA72-4 and CA125 in gastric cancer patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy,” World J Surg Onc, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 397, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Lakemeyer, S. Sander, M. Wittau, D. Henne-Bruns, M. Kornmann, and J. Lemke, “Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of CEA and CA19-9 in Colorectal Cancer,” Diseases, vol. 9, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J.-X. Jing et al., “Tumor Markers for Diagnosis, Monitoring of Recurrence and Prognosis in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer,” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, vol. 15, no. 23, pp. 10267–10272, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Galle et al., “Biology and significance of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma,” Liver International, vol. 39, no. 12, pp. 2214–2229, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. He et al., “Clinicopathologic and prognostic characteristics of alpha-fetoprotein–producing gastric cancer,” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 14, p. 23817, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Madhavan et al., “Circulating miRNAs with prognostic value in metastatic breast cancer and for early detection of metastasis,” Carcinogenesis, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 461–470, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Hamam et al., “Circulating microRNAs in breast cancer: novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers,” Cell Death Dis, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. e3045–e3045, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R.-Y. Li and Z.-Y. Liang, “Circulating tumor DNA in lung cancer: real-time monitoring of disease evolution and treatment response,” Chinese Medical Journal, vol. 133, no. 20, pp. 2476–2485, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou, W. Shen, H. Zou, Q. Lv, and P. Shao, “Circulating exosomal long non-coding RNA H19 as a potential novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer,” J Int Med Res, vol. 48, no. 7, p. 0300060520934297, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Jiang, Y. Gu, Y. Du, and J. Liu, “Exosomes: Diagnostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Delivery Vehicles for Cancer,” Mol. Pharmaceutics, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 3333–3349, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Huyghe, E. Benidovskaya, P. Stevens, and M. Van den Eynde, “Biomarkers of Response and Resistance to Immunotherapy in Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer: Toward a New Personalized Medicine,” Cancers, vol. 14, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Colle et al., “Immunotherapy and patients treated for cancer with microsatellite instability,” Bulletin du Cancer, vol. 104, no. 1, pp. 42–51, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C.-Y. He et al., “Classification of gastric cancer by EBV status combined with molecular profiling predicts patient prognosis,” Clinical and Translational Medicine, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 353–362, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Shen et al., “EBV infection and MSI status significantly influence the clinical outcomes of gastric cancer patients,” Clinica Chimica Acta, vol. 471, pp. 216–221, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Yuan, Z.-Y. Xu, S.-M. Ruan, S. Mo, J.-J. Qin, and X.-D. Cheng, “Long non-coding RNAs towards precision medicine in gastric cancer: early diagnosis, treatment, and drug resistance,” Mol Cancer, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 96, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Cao et al., “Circulating long noncoding RNAs as potential biomarkers for stomach cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” World J Surg Onc, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 89, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Hegde and D. S. Chen, “Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy,” Immunity, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 17–35, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Chen, T. W. H. Shuen, and P. K. H. Chow, “The association between tumour heterogeneity and immune evasion mechanisms in hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical implications,” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 131, no. 3, p. 420, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Chowell et al., “Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6375, pp. 582–587, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Schneider et al., “Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update,” JCO, vol. 39, no. 36, pp. 4073–4126, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Gopalakrishnan et al., “Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6371, pp. 97–103, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Pagliuca, C. Gurnari, M. T. Rubio, V. Visconte, and T. L. Lenz, “Individual HLA heterogeneity and its implications for cellular immune evasion in cancer and beyond,” Front. Immunol., vol. 13, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Mitchell, A. Gandhi, D. Scott-Coombes, and P. Perros, “Management of thyroid cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines,” J. Laryngol. Otol., vol. 130, no. S2, pp. S150–S160, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Dhatchinamoorthy, J. D. Colbert, and K. L. Rock, “Cancer Immune Evasion Through Loss of MHC Class I Antigen Presentation,” Front. Immunol., vol. 12, p. 636568, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]