Submitted:

28 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. BSGs Source

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. BSG Protein Extracts

2.5. Protein Determination

2.6. SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis)

2.7. Milk-Clotting Activity of BSG1 Extract

2.8. Caseinolytic Activity of BSGs Extracts

2.9. Influence of pH and Temperature on CA

2.10. Endopeptidases Inhibition Profile

2.11. Hydrolysis of the Bovine Casein Subunits

3. Results and Discussion

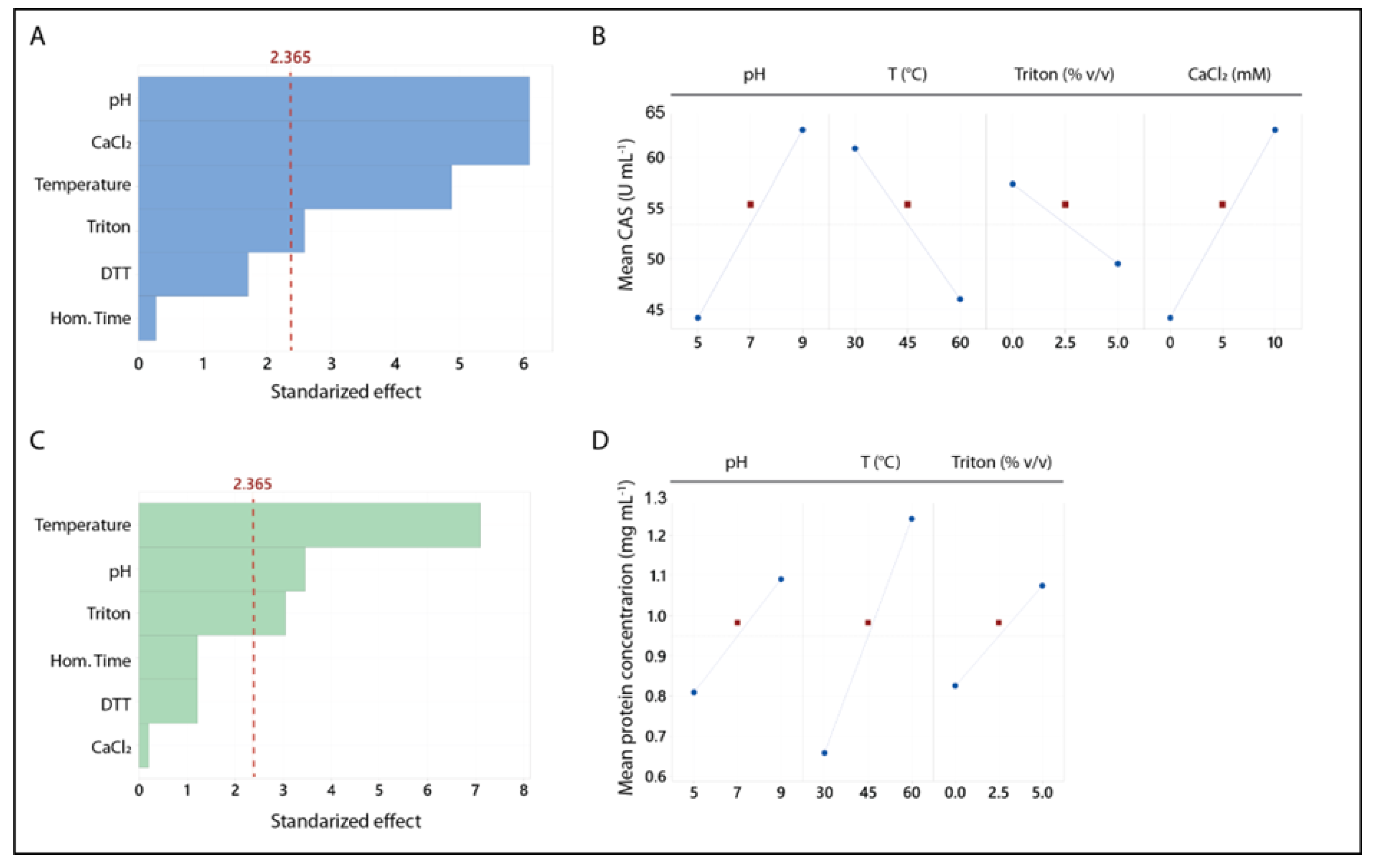

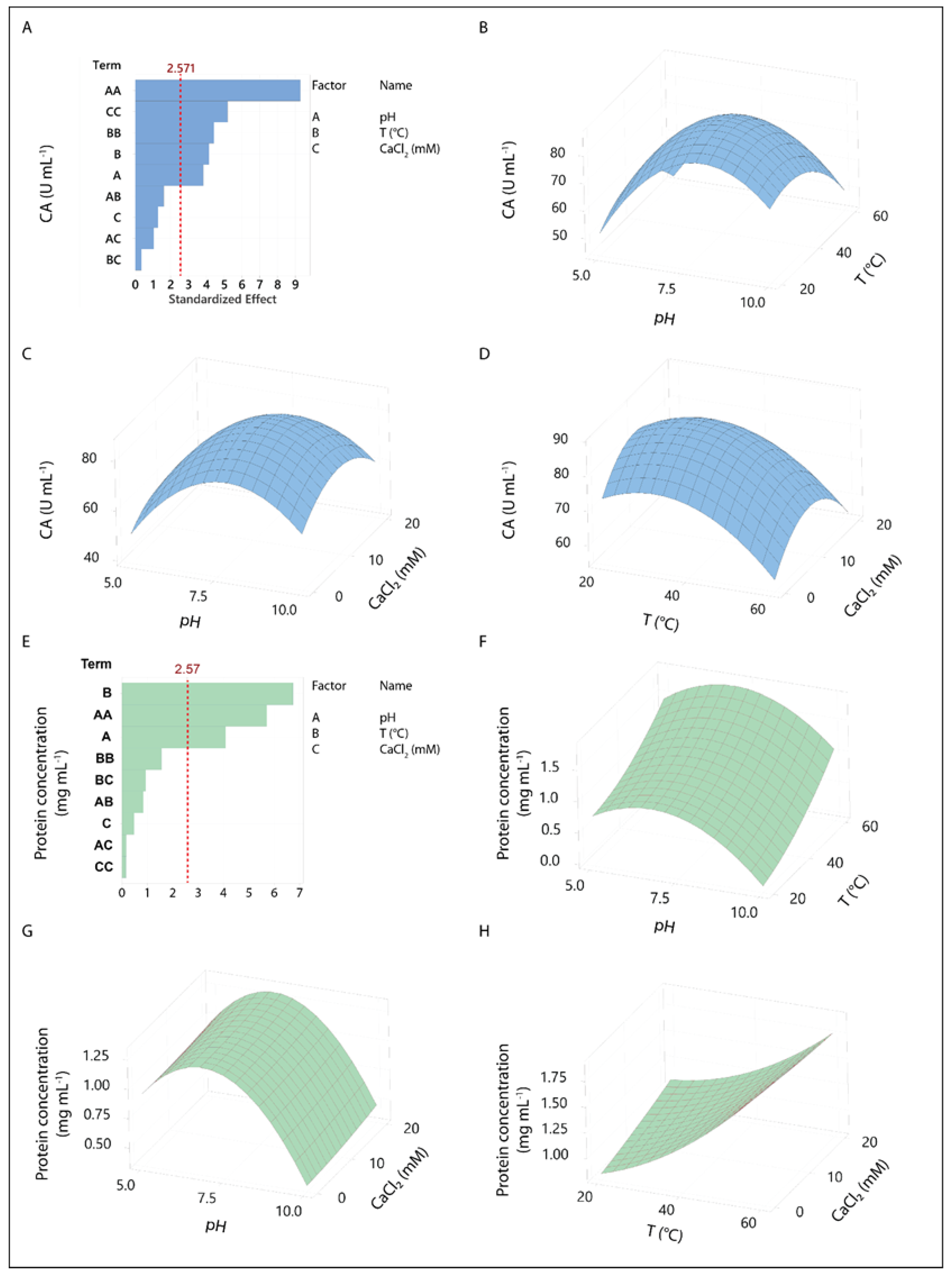

3.1. Finding Significant Variables That Affect Extraction of Endopeptidases with Caseinolytic Activity from BSG

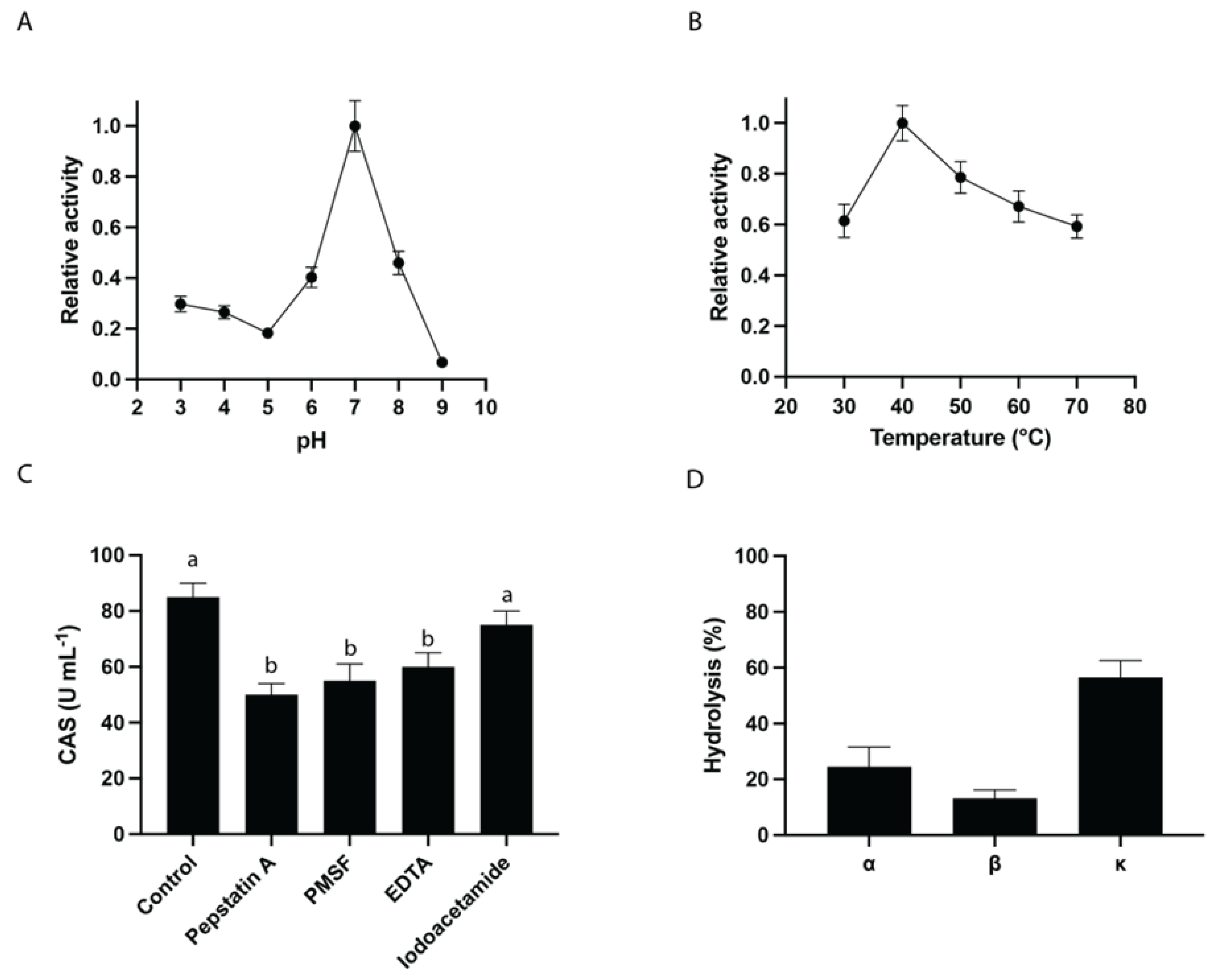

3.2. Characterization of CA of BSG1 Extract

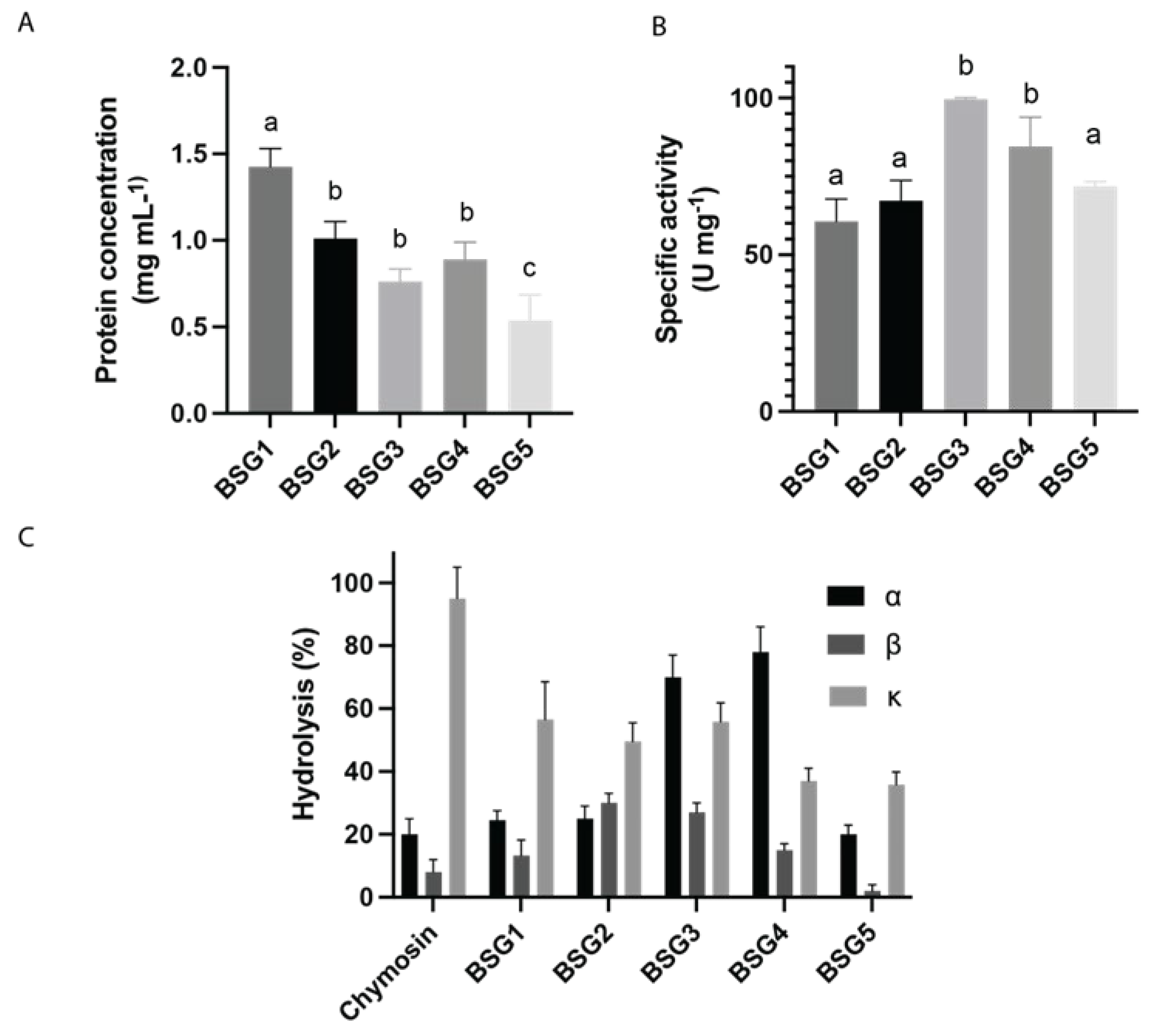

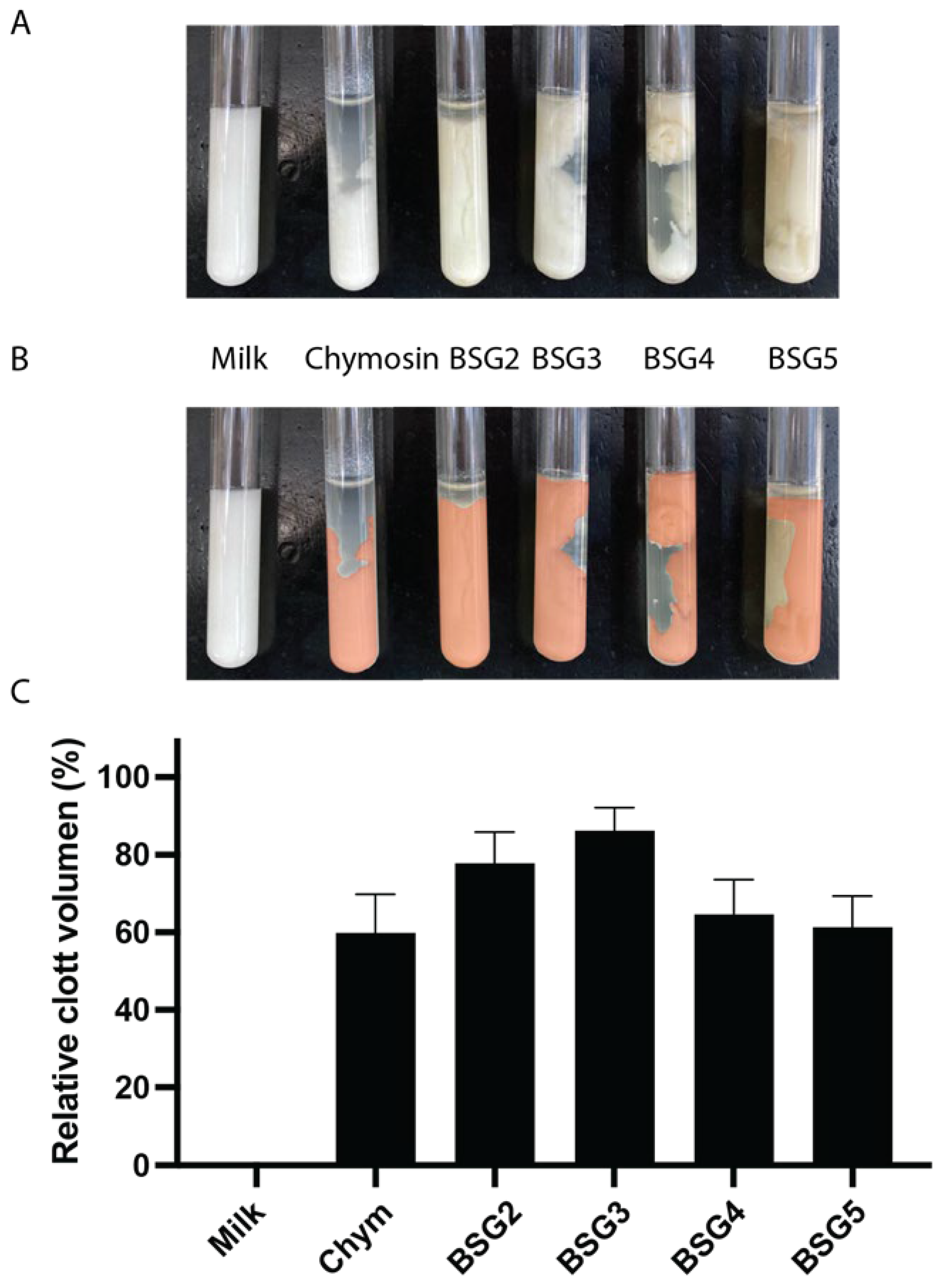

3.3. Comparative Analysis of BSGs Derived from Different Beer Styles: Impact on CA and MCA

4. Conclusions

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| BSG | brewer’s spent grain |

| BBD | box-behnken design |

| RSM | response surface methodology |

| CA | caseinolytic activity |

| MCA | milk-clotting activity |

| BCA | bicinchoninic acid |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| MWM | molecular weight markers |

| PMSF | phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| SCA | specific caseinolytic activity |

References

- Jackowski, M.; Niedźwiecki, Ł.; Kacper, O.J.; Uchańska; Trusek, A. Brewer’s Spent Grains-Valuable Beer Industry By-Product. Biomolecules. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainardis, M.; Hickey, M.; Dereli, R.K. Lifting craft breweries sustainability through spent grain valorisation and renewable energy integration: A critical review in the circular economy framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetrariu; Dabija, A. Spent grain: A functional ingredient for food applications. Foods 2023, 12, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabbathi, N.P.P.; Velidandi, A.; Pogula, S.; Gandam, P.K.; Baadhe, R.R.; Sharma, M.; Sirohi, R.; Thakur, V.K.; Gupta, V.K. Brewer’s spent grains-based biorefineries: A critical review. Fuel (Lond.) 2022, 317, 123435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, L.; Sahin, A.W.; Schmitz, H.H.; Siegel, J.B.; Arendt, E.K. Brewers’ spent grain: An unprecedented opportunity to develop sustainable plant-based nutrition ingredients addressing global malnutrition challenges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 10543–10564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Pontonio, E.; Krona, A.; Jacob, S.; Pinto, D.; Rinaldi, F.; Verardo, V.; Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Bioprocessing of brewers’ spent grain enhances its antioxidant activity: Characterization of phenolic compounds and bioactive peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.M.; Coverdale, S.M.; Cole, N.; Hamilton, S.E.; Jersey, J.; Inkerman, P.A. Characterisation and assessment of the role of barley malt endoproteases during malting and Mashing1. J. Inst. Brew. 2002, 108, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.M.H.; Beattie, A.D.; Rossnagel, B.; Scoles, G. Thermostability of barley malt proteases in western Canadian two-row malting barley. Cereal Chem. 2011, 88, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, J.H.; Goodfellow, V.; Agu, R.C.; Brosnan, J.M.; Bringhurst, T.A.; Jack, F.R. Effect of different steeping conditions on endosperm modification and quality of distilling malt. J. Inst. Brew. 2010, 116, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, J.H.; Scott, M.B.; McCafferty, K.A.; Johnston, J.A.; A, M; Raven; Thornton, J.M.; Morris, P.C.; Footitt, S. Mobilisation of energy reserves in barley grains during imbibition of water. In Distilled Spirits: New Horizons: Energy, Environment And; Independent Publishers Group, 2010; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Potokina, E.; Caspers, M.; Prasad, M.; Kota, R.; Zhang, N.; Sreenivasulu; Wang, M.; Graner, A. Functional association between malting quality trait components and cDNA array based expression patterns in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Mol. Breed. 2004, 14, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L. Endoproteases of barley and malt. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 42, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.E.; Stewart, G.G. Free Amino Nitrogen in brewing. Fermentation 2019, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laus; Endres, F.; Hutzler, M.; Zarnkow, M.; Jacob, F. Isothermal mashing of barley malt: New insights into wort composition and enzyme temperature ranges. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2022, 15, 2294–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L.; Budde, A.D. How various malt endoproteinase classes affect wort soluble protein levels. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 41, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, G.A.; Corazza, M.L.; Blanco, A.M.; Corazza, F.C. Dynamic optimization of the mashing process. Food Control 2009, 20, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viader, R.P.; Yde, M.S.H.; Hartvig, J.W.; Pagenstecher, M.; Bille, T.B.C.J.; Christensen; Andersen, M.L. Optimization of beer brewing by monitoring α-amylase and β-amylase activities during mashing. Beverages 2021, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devnani, B.; Moran, G.C.; Grossmann, L. Extraction, Composition, Functionality, and Utilization of Brewer’s Spent Grain Protein in Food Formulations, and. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Dan, M.; Zhao, G.; Wang, D. Recent advances in microbial high-value utilization of brewer’s spent grain. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 408, 131197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, A.-G.; Dragomir, C.; Untea, A.; Saracila, M.; Turcu, R.; Cismileanu, A.; Boldea, I.; Radu, G.L. The effects of brewer’s spent yeast (BSY) inclusion in dairy sheep’s diets on ruminal fermentation and milk quality parameters. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, A.T.; Adane, K.; Tikunesh, W.Z. Atalel Effects of Brewery Spent Grain Silage Based Feeding on Feed Intake, Milk Yield, Milk Efficiency, and, Proceedings of the 16th Annual Regional Conference on Completed Research Activities. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EL-Moneim, R.A.; Shamsia, S.; EL-Deeb, A.; Ziena, H. Utilization of brewers spent grain (bsg) in making functional yoghurt. Journal of Food and Dairy Sciences 2015, 6, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moneim, R.A.; Shamsia, S.; EL-Deeb, A.; Ziena, H. Utilization of brewers spent grain (BSG) in producing functional processed cheese “‘block’”. Journal of Food and Dairy Sciences 2018, 2018, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julkovski, D.J.; Sehnem, S.; da C, M. ; Ramos Circularity of resources in the craft brewery segment: An analysis supported by innovation. Environ. Qual. Manage. 2024, 33, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquet, P.-L.; Villain-Gambier, M.; Trébouet, D. By-product valorization as a means for the brewing industry to move toward a circular bioeconomy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.Z.; Norsah, E.; Marzlan, A.A.; Rahim, M.H.A.; Hussin, A.S.M. Exploring the applications of plant-based coagulants in cheese production: A review. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 148, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.A.; Mir, S.A.; Paray, M.A. Plant proteases as milk-clotting enzymes in cheesemaking: A review. Dairy Sci Technol 2014, 94, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amira, B.; Besbes, S.; Attia, H.; Blecker, C. Milk-clotting properties of plant rennets and their enzymatic, rheological, and sensory role in cheese making: A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, S76–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazorra-Manzano, M.A.; Moreno-Hernández, J.M.; Ramírez-Suarez, J.C. Milk-Clotting Plant Proteases for Cheesemaking. In Biotechnological Applications of Plant Proteolytic Enzymes; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, F.D.; Sánchez, D.A.; Ferreira, M.L. Production of Plant Proteases and New Biotechnological Applications: An Updated Review. ChemistryOpen 2022, 11, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, J.P.; Manikandan, S.; Priya, B.; Gurumoorthi, P. Box-Behnken design based multi-response analysis and optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of bioactive flavonoid compounds from tea (Camellia sinensis L.) leaves. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Team, R.C., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R.V. Response-Surface Methods in R, Using rsm. J. Stat. Soft. 2009, 32, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Krohn, R.I.; Hermanson, G.T.; Mallia, A.K.; Gartner, F.H.; Provenzano, M.D.; Fujimoto, E.K., N M; Olson; Klenk, D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985, 150, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-H.; Wong, H.-K.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-M. Evaluating the compatibility of three colorimetric protein assays for two-dimensional electrophoresis experiments. Proteomics 2008, 8, 2178–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature Publishing Group 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, N.D. Protease families, evolution and mechanism of action. In Proteases: Structure and Function; Springer Vienna: Vienna, 2013; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pontual, E.V.; Carvalho, B.E.A.; Bezerra, R.S.; Coelho, L.C.B.B.; Napoleão, T.H.; Paiva, P.M.G. Caseinolytic and milk-clotting activities from Moringa oleifera flowers. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celus; Brijs, K.; Delcour, J.A. The effects of malting and mashing on barley protein extractability. J. Cereal Sci. 2006, 44, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L.; Marinac, L. The effect of mashing on malt endoproteolytic activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, K.; Rani, R.H.S. Design of Experiments: Concept and Applications of Plackett Burman Design. Clin. Res. Regul. Aff. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, S.R.; Shirkhedkar, A.A. Application of Plackett-Burman and central composite designs for screening and optimization of factor influencing the chromatographic conditions of HPTLC method for quantification of efonidipine hydrochloride. J Anal Sci Technol 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlapudi, A.P.; Krupanidhi, S., Reddy; Md, N.B.; V. T., C. Plackett-Burman design for screening of process components and their effects on production of lactase by newly isolated Bacillus sp. VUVD101 strain from Dairy effluent. Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 2018, 7, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, A.V.; Gago, J.; García, I.; León, V.M.; Viñas, L. Plackett Burman design for microplastics quantification in marine sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 162, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cao, J.; Liu, W. Friction coefficient calibration of corn stalk particle mixtures using Plackett-Burman design and response surface methodology. Powder Technol. 2022, 396, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, K.A.M.; Amin, M.A.M. Overview on the response surface methodology (RSM) in extraction processes. Journal of Applied Science & Process Engineering 2015, 2, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yang, H.; Coldea, T.E.; Zhao, H. Modification of structural and functional characteristics of brewer’s spent grain protein by ultrasound assisted extraction. LWT 2021, 139, 110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe; Tito, F.R., Raúl. Guevara Optimization of fibrinogenolytic activity of Solanum tuberosum subtilisin-like protease (StSBTc-3) by response surface methodology. Biotechnology Reports 2019, 22, e00330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, F.R.; Pepe, A.; Tonón, C.V.; Daleo, G.R.; Guevara, M.G. Optimization of caseinolytic and coagulating activities of Solanum tuberosum rennets for cheese making. J Sci Food Agric 2023, 103, 6947–6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartino, M. Enzymes in brewing. Mbaa Tq 2015, 52, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, P.K.; Talukdar, S.A.; Promita, S.A.D.; Sayem; Mohsina, K. Optimization and partial characterization of culture conditions for the production of alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis P003. Springerplus 2013, 2, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Guan, R.; Guochao, Y.J.; Zhang, Y. Advances in research on calf rennet substitutes and their effects on cheese quality. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Vaid, S.; Bhat, B.; Singh, S.; Bajaj, B.K. Thermostable Enzymes for Industrial Biotechnology. In Advances in Enzyme Technology; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 469–495. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly; Piggott, C.O.; FitzGerald, R.J. Characterisation of protein-rich isolates and antioxidative phenolic extracts from pale and black brewers’ spent grain. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger; Zannini, E.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K. arley protein properties, extraction and applications, with a focus on brewers’ spent grain protein. Foods 2021, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.E.N.; Colpini, L.M.S. All-around characterization of brewers’ spent grain. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalor, E.; Goode, D. Brewing with Enzymes. In Enzymes in Food Technology; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bamforth, C.W. Current perspectives on the role of enzymes in brewing. J. Cereal Sci. 2009, 50, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijs, K.; Trogh, I.; Jones, B.L.; Delcour, J.A. Proteolytic Enzymes in Germinating Rye Grains. Cereal Chem 2002, 79, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, L.K.; MacGibbon, A.K.H. Some recent advances in the basic chemistry of milk proteins and lipids. Int. Dairy J. 1996, 6, 539–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.F.F.J.A. Importance of Calcium and Phosphate in Cheese Manufacture: A Review. J Dairy Sci 1993, 76, 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harboe, M.; Broe, M.L.; Qvist, K.B. The production, action and application of rennet and coagulants. In Technology of Cheesemaking; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 98–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, L.F.; Zapata, P.; Ruiz-Tirado, L. Agro-industrial waste enzymes: Perspectives in circular economy. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 34, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Hassan, S.S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. A review on bioconversion of Agro-industrial wastes to industrially important enzymes. Bioengineering (Basel) 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murlidhar, M.; Anusha, R.; Bindhu, O.S. Plant-based coagulants in cheese making: Review. In Dairy Engineering, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: Waretown, NJ; Apple Academic Press, 2017; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.; Belo, A.T.; Alvarenga, N.; Dias, J.; Lage, C.; Pinheiro; Pinto-Cruz, C.; Brás, T.; Duarte, M.F.; Martins, A.P. Characterization of Cynara cardunculus L. flower from Alentejo as a coagulant agent for cheesemaking. Int. Dairy J. 2019, 91, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazorra-Manzano, M.A.; Martin, J.C.M.-H.J.; Ramírez-Suarez; de Jesús, A.F.T.-L.M.; González-Córdova; Vallejo-Córdoba, B. Sour orange Citrus aurantium L. flowers: A new vegetable source of milk-clotting proteases. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2013, 54, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.D.T.; Leite, H.B.; João, J.L.O.; P, B; Amaral; Egito, A.S.; Vairo-Cavalli, S.; Lobo, M.D.P.; Monteiro-Moreira, A.C.O.; Ramos, M.V. Insights into milk-clotting activity of latex peptidases from Calotropis procera and Cryptostegia grandiflora. Food Res. Int. 2016, 87, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitu, S.; Geicu-Cristea, M.; Matei, F. MILK-CLOTTING ENZYMES OBTAINED FROM PLANTS IN CHEESEMAKING - A REVIEW. Scientific Bulletin Series F. Biotechnologies 2021, 25, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Roa; Belén, L.M.; Javier, M.F. Residual clotting activity and ripening properties of vegetable rennet from Cynara cardunculus in La Serena cheese. Food Res. Int. 1999, 32, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Levels | |

|---|---|---|

| -1 | +1 | |

| pH | 5 | 9 |

| Temperature (°C) | 30 | 60 |

| Homogenization time (min) | 1 | 3 |

| DTT (mM) | 0 | 10 |

| Triton X-100 (%v/v) | 0 | 5 |

| CaCl2 (mM) | 0 | 10 |

| Variable | Levels | |

|---|---|---|

| -1 | +1 | |

| pH | 5 | 10 |

| Temperature (°C) | 20 | 60 |

| CaCl2 (mM) | 0 | 20 |

| Run | pH | T (°C) | Homogenization time (min) | Triton (%v/v) | DTT (mM) | CaCl2 (mM) | CA (U mL-1) | Protein concentration (mg mL-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 30 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 0.80 |

| 2 | 9 | 60 | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 1.60 |

| 3 | 5 | 60 | 3 | 0.0 | 10 | 0 | 31 | 1.00 |

| 4 | 9 | 30 | 3 | 5.0 | 0 | 10 | 83 | 0.90 |

| 5 | 9 | 60 | 1 | 5.0 | 10 | 0 | 43 | 1.30 |

| 6 | 9 | 60 | 3 | 0.0 | 10 | 10 | 65 | 1.20 |

| 7 | 5 | 60 | 3 | 5.0 | 0 | 10 | 45 | 1.50 |

| 8 | 5 | 30 | 3 | 5.0 | 10 | 0 | 33 | 0.60 |

| 9 | 5 | 30 | 1 | 5.0 | 10 | 10 | 51 | 0.55 |

| 10 | 9 | 30 | 1 | 0.0 | 10 | 10 | 82 | 0.75 |

| 11 | 5 | 60 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 10 | 50 | 0.85 |

| 12 | 5 | 30 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 0.35 |

| 13 | 7 | 45 | 2 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 55 | 0.95 |

| 14 | 7 | 45 | 2 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 51 | 1.10 |

| 15 | 7 | 45 | 2 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 60 | 0.90 |

| Run | pH | T (°C) | CaCl2 (mM) | CA (U mL-1) | Protein concentration (mg mL-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 20 | 10 | 50 | 0.82 |

| 2 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 70 | 0.12 |

| 3 | 5 | 60 | 10 | 45 | 1.38 |

| 4 | 10 | 60 | 10 | 51 | 0.99 |

| 5 | 5 | 40 | 0 | 49 | 1.03 |

| 6 | 10 | 40 | 0 | 55 | 0.48 |

| 7 | 5 | 40 | 20 | 45 | 0.87 |

| 8 | 10 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 0.39 |

| 9 | 7.5 | 20 | 0 | 75 | 0.66 |

| 10 | 7.5 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 1.87 |

| 11 | 7.5 | 20 | 20 | 65 | 1.08 |

| 12 | 7.5 | 60 | 20 | 53 | 1.95 |

| 13 | 7.5 | 40 | 10 | 85 | 1.08 |

| 14 | 7.5 | 40 | 10 | 90 | 1.38 |

| 15 | 7.5 | 40 | 10 | 80 | 1.22 |

| CA | Protein concentration | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.9 | 7.0 |

| T (°C) | 33 | 60 |

| CaCl2 (mM) | 9 | Non significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).