1. Introduction

In recent years, solar energy has emerged as the fastest-growing renewable energy technology[

1].A common method of utilizing solar energy is through solar thermal concentration systems, which convert solar energy into thermal energy. These systems can be classified based on their focusing method into point-focusing systems (tower systems and dish systems) and line-focusing systems (parabolic trough systems and linear Fresnel systems)[

2].The parabolic trough solar thermal power generation system is currently one of the most prominent solar thermal power systems. This technology is the most commercially mature, and has been tested in a variety of practical situations and is also the most widely used[

3,

4].

The line-focusing trough solar energy system mainly includes a tracking system, receiver and reflector. There are two types of tracking systems: Dual-Axis Tracking System (DAT) and Single-Axis Tracking System (SAT). The single-axis tracking system can be further divided into the North-South tracking system (NS), East-West tracking system (EW) and polar tracking system based on the position of the rotation axis[

5].Early trough systems used flat receivers, which had a low concentration ratio and were later replaced by tube receivers[

6]. The reflector typically employs a parabolic trough mirror, which efficiently reflects and concentrates the solar radiation towards the receiver. However, the trough reflectors are challenging to manufacture, often resulting in significant slope errors in the mirror surface. Therefore, it is possible to consider using spliced cylindrical mirrors instead of complete trough mirrors, which can reduce the process difficulty of manufacturing and reduce the mirror slope errors.

Solar trough collector systems with cylindrical trough collectors have been studied for a long time. Hassan and Refaie [

7]studies examined cylindrical parabolic solar collector defining their ideal performance as a benchmark for intermediate-temperature reflectors. It identified optimal target widths for maximizing the energy concentration in different solar collector configurations, observing a continuous energy increase for the backside solar collector. Evans[

8]provided an integral expression to calculate the concentration ratios of flat receivers with cylindrical parabolic solar collectors by incorporating rim angles, solar models, and mirror reflectivity. Ruben[

9]compared five line-focusing solar trough collectors and found that the cylindrical-parabolic solar collector attained the best-focusing factor. Further studies of Ruben evaluated four solar-disk models (square, uniform, real, and Gaussian) and found that the real model was the most accurate, significant differences in local concentration factors appeared only when solar concentrator imperfections were small and non-concentrators were also considered, for practical applications, all models were sufficient for concentration calculations with typical imperfections, but precise local calculations required careful model selection[

10] Nijegorodov[

11]presented an optimized design for cylindrical solar collector, designed at a rim angle of 45°which offered a good balance between cost, performance, less sensitivity to solar ray deviations and provided consistent efficiency for thermal application. Other focusing solar collectors, such as the dish solar concentrators, use segmented mirrors instead of complete mirrors. Previously, we proposed a novel composite dish concentrator comprising 249 spherical mirrors with a concentration ratio of approximately 2000, which achieved a net thermal efficiency of 85.87% and an intercept factor of 98.60%[

12].

In 2003, the Australian National University (ANU) proposed a dish concentrator that employed an array of equilateral triangular spherical mirrors, the 400 m² composite spherical mirrors were configured in a parabolic shape to assess their optical performance, feasibility in paraboloidal dish concentrators and compared with conventional multi-facet solar collectors. The study suggested that utilizing identical spherical reflector sub-components oriented paraboloidal on a space frame structure could simplify the manufacturing process and lower the costs, with optical performance similar to traditional designs, while simplifying mirror panel production[

13]. Australian National University subsequently designed and built a 500m² composite dish solar system with 390 spherical mirrors, each measuring 1.17 m × 1.17 m[

14].

Furthermore, Liu[

15] in 2012 proposed a dish solar collector as a model for a parabolic surface using square flat facets supported by a parabolic frame, optimized it to achieve specific flux characteristics at the focal plane through Monte Carlo ray-tracing analysis. Key findings included the design and optimization of a 164-facet concentrator delivering up to 8.15 kW of radiative power over a 15 cm radius disk, achieving an average concentration ratio exceeding 100. This design offered a cost-effective alternative to traditional parabolic dish concentrators for industrial applications. When employing circular mirrors such as cylindrical mirrors as replacements for parabolic mirrors, the critical issue to address is the spherical aberration, for example of a circular mirror because of its constant curvature that is , light rays hitting different parts of the mirror do not focus at the same point, rays converge on the focal plane instead of the focal line resulting in aberration. Aberration theory states that, in Kleopalova’s "Research and Inspection of Optical Systems" page 175[

16], the relative aperture of a spherical reflector as the primary mirror should not exceed 1:10.8 that means, the ratio of the reflector aperture to the focal length is ⩽1/10.8 which is then converted to the ratio of the reflector aperture to the spherical radius ⩽1/21.6. In the field of solar energy concentration, optical systems are mainly used for concentration and the requirements are much lower than those for optical imaging.

The receiver is one of the most critical components of a parabolic trough concentrator. When optimizing a parabolic trough solar collector, one of the essential parameters of the receiver is the concentration ratio (CR) defined as the ratio of the area of the light collection region to the location of the light absorption region[

17]and also the concentration ratio is inversely related to the efficiency loss caused by thermal losses[

18].The relatively high concentration ratio design allows the parabolic trough system to operate at a higher temperature. Since the heat loss per unit area of the receiver is large, and the tube receiver has a large heat dissipation area and a low concentration ratio, the efficiency loss caused by heat loss is large. Compared with traditional receivers, cavity receivers have lower heat loss and higher efficiency and can operate at higher temperatures, improving the efficiency of the thermoelectric system and the overall system efficiency [

19,

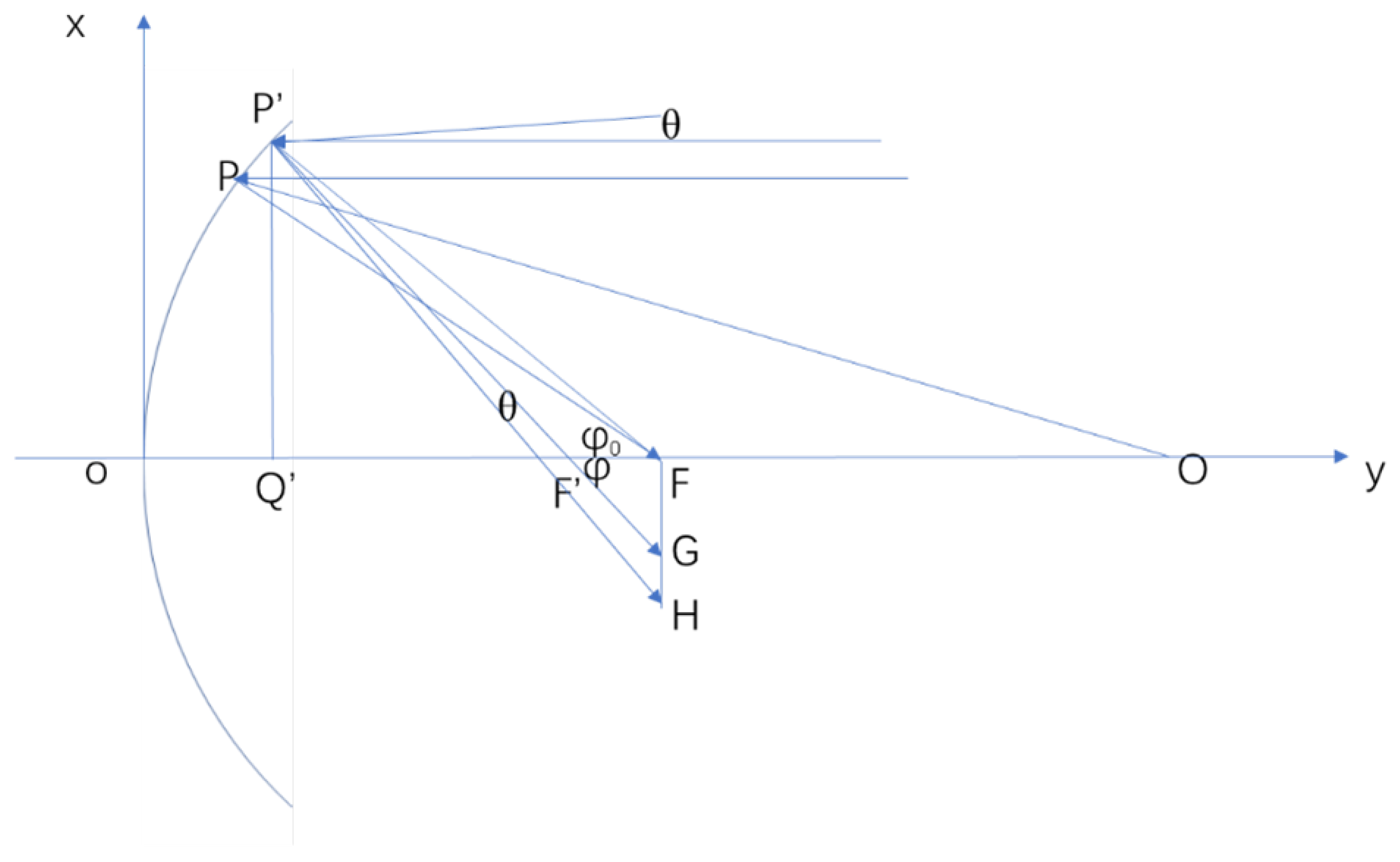

20]. The main methods for analyzing and optimizing trough solar collectors include the cone optics method [

21,

22,

23], the ray tracing method[

24,

25] and the semi-infinite method [

26]. The cone optics method treats the sunlight beam as a cone with the incident point as the vertex and to calculate the energy absorbed at each point on the receiver, the entire surface of the reflector must be integrated. The semi-infinite method has accurate physical characteristics, but due to its complex formulas, it still requires a large amount of computation. The ray tracing method is a widely used microscopic approach that is easy to code, but because it involves the calculation of a large number of rays, it brings a significant computational burden. This method simulates the process of sunlight being incident on the solar collector and then reflected onto the receiver, with each ray representing a portion of the energy incident on the receiver [

24,

27]. Daly proposed a reverse ray tracing method to calculate the performance of parabolic trough systems [

24], which was later improved by several researchers. Grena developed a three-dimensional model based on a recursive ray tracing algorithm [

27]. Jiang and others proposed a parabolic trough hybrid photovoltaic/thermal system and used the ray tracing method to establish a three-dimensional optical model for the system [

25]. Zou and others considered the impact of ray escape on parabolic trough systems, studying the system using the Monte Carlo ray tracing method and theoretical analysis [

28]. Houcine[

29] proposed a detailed calculation method based on ray tracing, called Ray Tracing 3Dimensions-4Rays (RT3D-4R) and studied the total intercepted solar energy and daily solar gain for parabolic trough solar collector systems under different concentration ratios and rim angles, using different tracking systems. One of the main drawbacks of the traditional ray tracing method is the large computational demand, making it difficult to use for performance optimization analysis.

This paper proposes a new cylindrical mirror spliced trough solar thermal collection system, which is similar to the conventional trough solar system, but uses multiple cylindrical mirrors to form a reflector to simulate a parabolic reflector. This paper also proposes a new line focusing system ray tracing method that can be used to calculate the performance of various line focusing solar systems. We use this model to analyze the performance of the cylindrical spliced solar system, including the performance under different error conditions and propose an optimized design. We also combine the trough reflector and the cylindrical mirror spliced reflector with the cavity receiver and the tube receiver, respectively, we calculate and compare the performance of these types of trough systems.

3. Results

Solar trough collector systems using tube receivers and cavity receivers were considered, the maximum rim angles of the solar collectors are 90° and 45° respectively and the focal lengths of the solar collectors configured with the two receivers are calculated to be 2m and 4.8m, respectively. We calculated and optimized the new cylindrical mirror-spliced solar trough system. The tube receiver and cavity receivers were considered separately and compared with the conventional parabolic trough concentrator. The data of the spliced cylindrical mirror trough solar collector used in the test are shown in the following table:

3.1. Model Validation

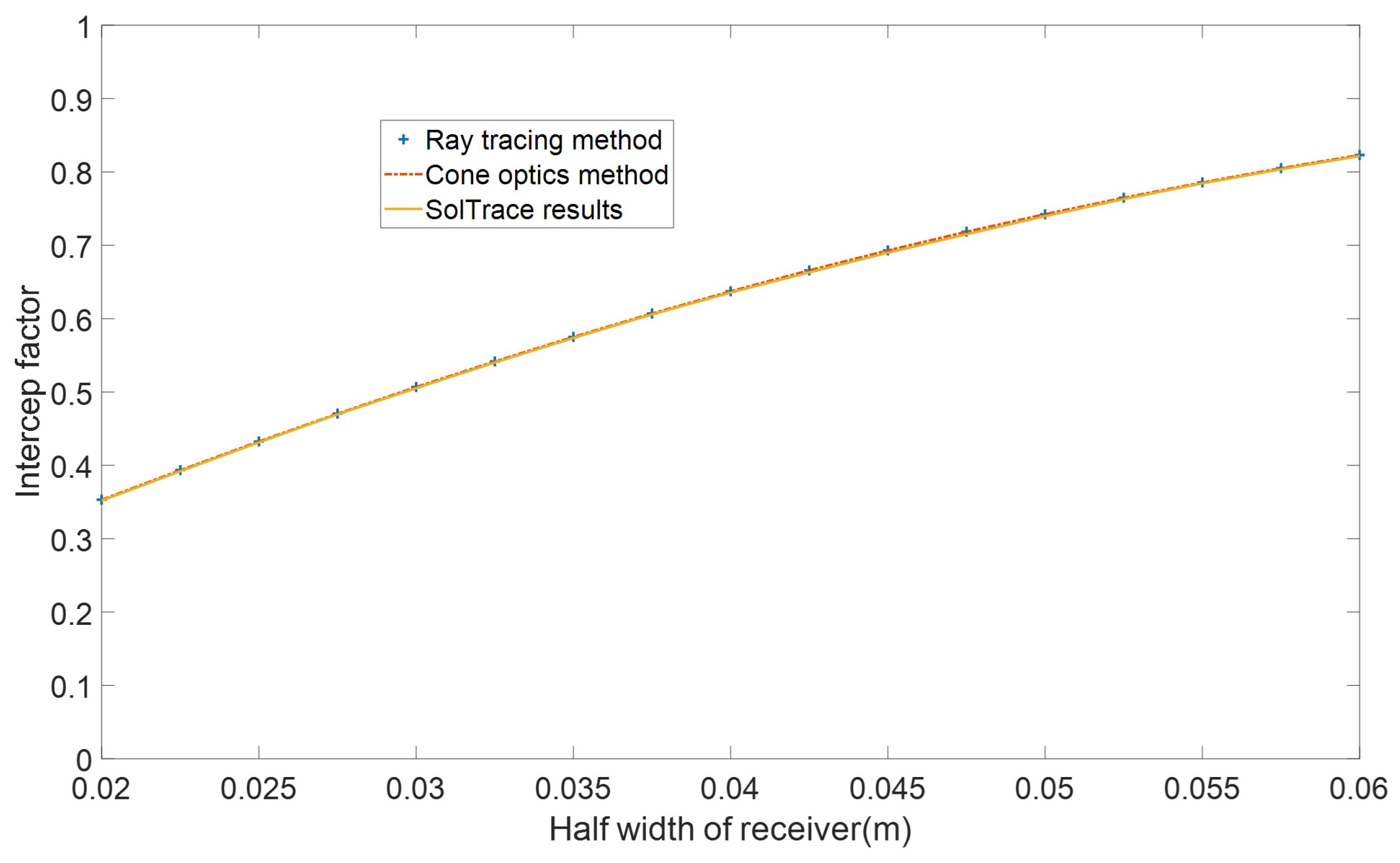

It is quite challenging to verify the model of the cylindrical spliced trough system because there are currently very few articles discussing and researching this type of trough system and no similar systems are in operation. In this paper, we use the ray-tracing method for calculations, which differs significantly from the cone optics method we used previously. Since the intercept factor is a key parameter determining the efficiency of the parabolic trough system, to verify the accuracy of this method, we used the ray-tracing method mentioned in this paper, the cone optics method[

22] and SolTrace software[

34] to calculate the intercept factor of the parabolic trough system at different receiver half-widths, as shown in

Figure 2.We used the same trough system data for all methods, with the sun’s half-angle set at 4.65 mrad and modelled as a Gaussian distribution. The optical errors in the x and y directions were 6 mrad, and the trough half-width was set to 4m. To simplify the model, we assumed that light rays were incident perpendicularly and that all rays incident on the mirror surface were fully reflected.

The calculation results showed that the average intercept factors obtained from the ray-tracing method, cone method and SolTrace simulation were 61.86%, 61.86% and 61.68%, respectively. The differences between the two calculation methods were minimal, with the maximum intercept factor error in the calculations being less than 0.026%. Additionally, the simulation results closely matched the SolTrace test results, with the maximum absolute deviation between the two methods being less than 0.31%. Therefore, the optical model used in this paper can effectively simulate the performance of a parabolic trough solar system.

3.2. Optimization of the Cylindrical Mirror Spliced Trough

The biggest challenge when using spliced cylindrical mirrors instead of parabolic trough mirrors as reflectors is the significant aberration present in cylindrical mirrors. It is necessary to control the width of the cylindrical mirror to reduce the effects of spherical aberrations. The requirements for optical imaging are that the ratio of mirror aperture to focal length should be less than 1/10.8 and the requirements for solar collectors are more moderate. In this study, the width of the cylindrical mirror should not exceed 1/5 of the trough width, when using tube receivers and cavity receivers, this value corresponds to a mirror width to focal length ratio of 1/2.5 and 1/6 respectively, which is well below the requirements for optical imaging. Cylindrical mirrors’ slope error is lower under the same manufacturing conditions as trough mirrors because usually the slope error of spherical mirrors for solar energy applications is approximated to be 1-2mrad[

35,

36] while the slope error for conventional parabolic trough mirrors is about 3-4 mrad. Therefore, using cylindrical mirrors instead of convectional parabolic trough mirrors as reflectors can effectively reduce manufacturing complexity and lower slope errors, making the performance almost indistinguishable from that of conventional trough solar collector systems with similar slope errors.

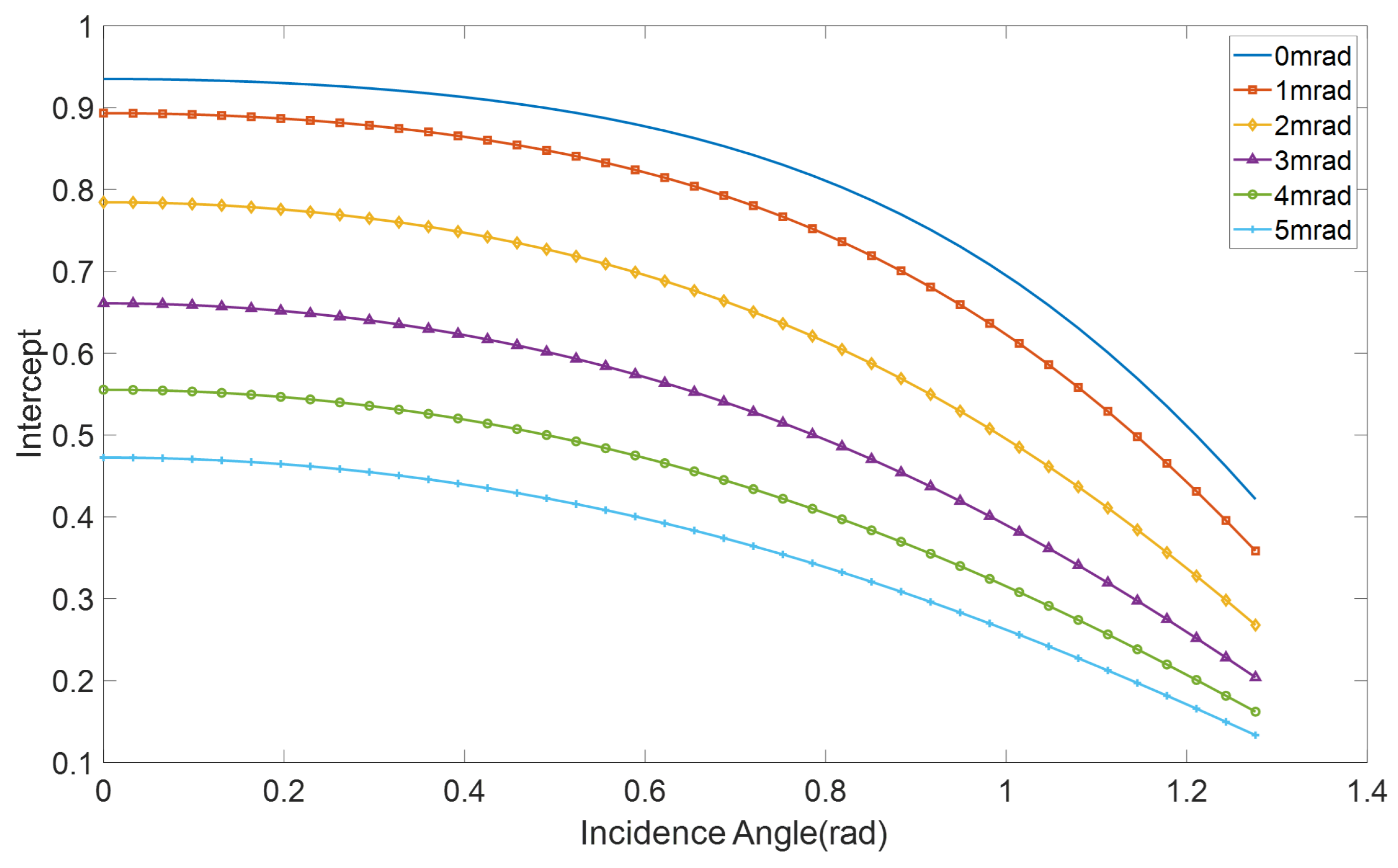

In

Figure 3, we calculated the intercept factor of the cylindrical mirror spliced solar collector system with a cavity receiver as the incident angle changes under different mirror slope errors. When the incident angle is 0.2rad and the slope error is 1mrad, the system intercept factor is 88.6%. When it reached 3mrad, the intercept factor decreased to 65.2% reduction of 26.4%. When the mirror slope error increases from 1mrad to 3mrad, the intercept factor will be significantly affected, coinciding with the slope error difference between spliced cylindrical mirrors and trough mirrors. Therefore, spliced cylindrical mirrors, instead of trough mirrors, can dramatically improve solar trough performance.

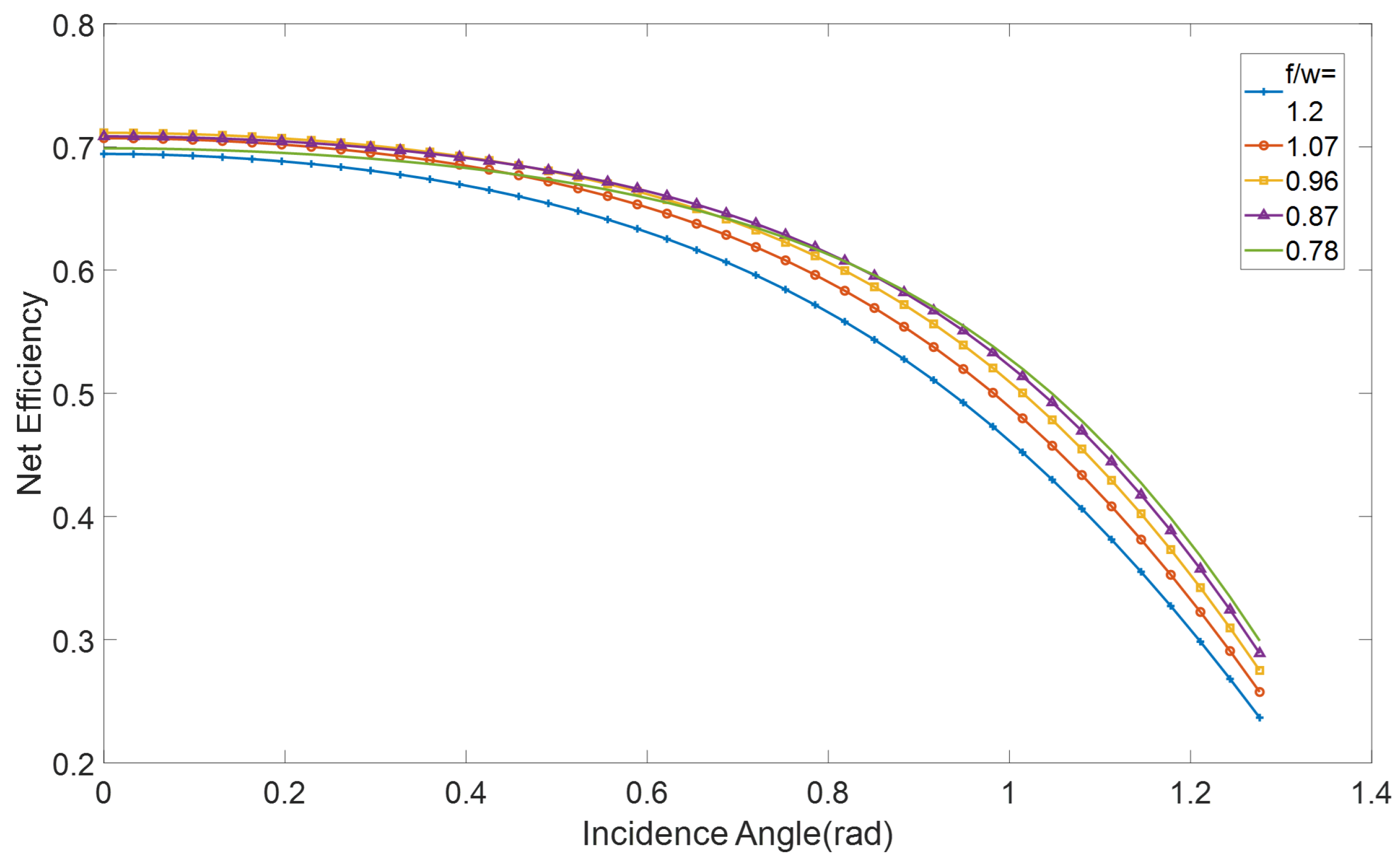

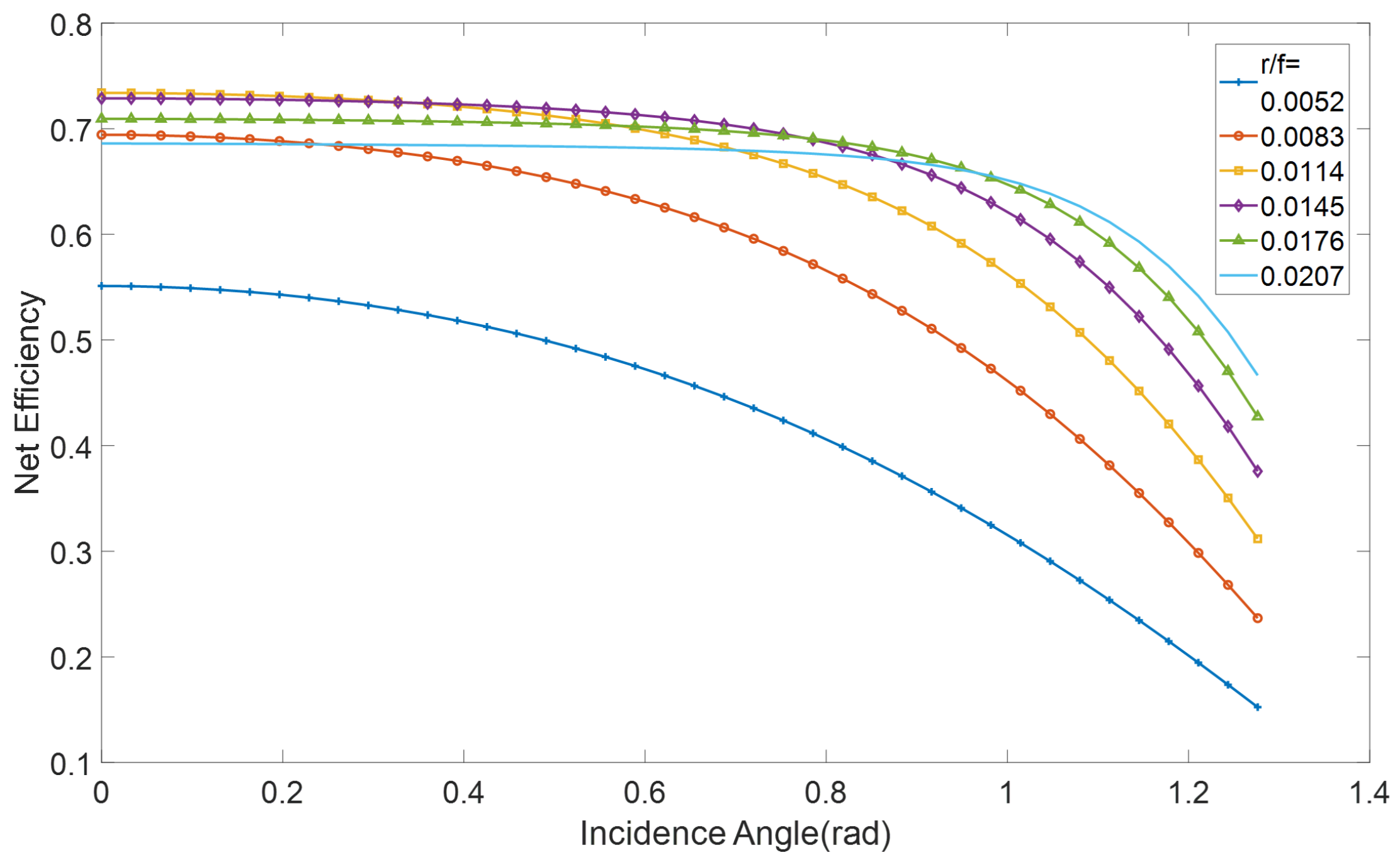

For conventional trough solar collector systems, the ratio of focal length to trough width (f/w) and the ratio of the receiver to focal length (r/f) are critical parameters in the numerical design and optimization of the solar collector systems. In

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, we calculated the net efficiency of the spliced cylindrical mirror solar collector system with different f/w and r/f parameters as the incident angle changes. The solar collector’s system net efficiency will change significantly at various incident angles due to the f/w and r/f impact. For example, when f/w was 0.78, the solar collector system efficiency was low when the incident angle was still low, after the incident angle was increased, the solar collector system efficiency began to be higher than the other types. When the incident angle is less than 0.9 rad, the solar trough collector system efficiency with an f/w of 0.87 performs best. After exceeding 0.9rad, the solar trough collector efficiency with f/w of approximately 0.78 is the highest. The net efficiency of the trough increases with r/f. When the r/f value is higher than a certain level, the benefits brought by the increase in concentration ratio are no longer advantageous over higher heat losses, and the net efficiency of the solar trough collector begins to decline.

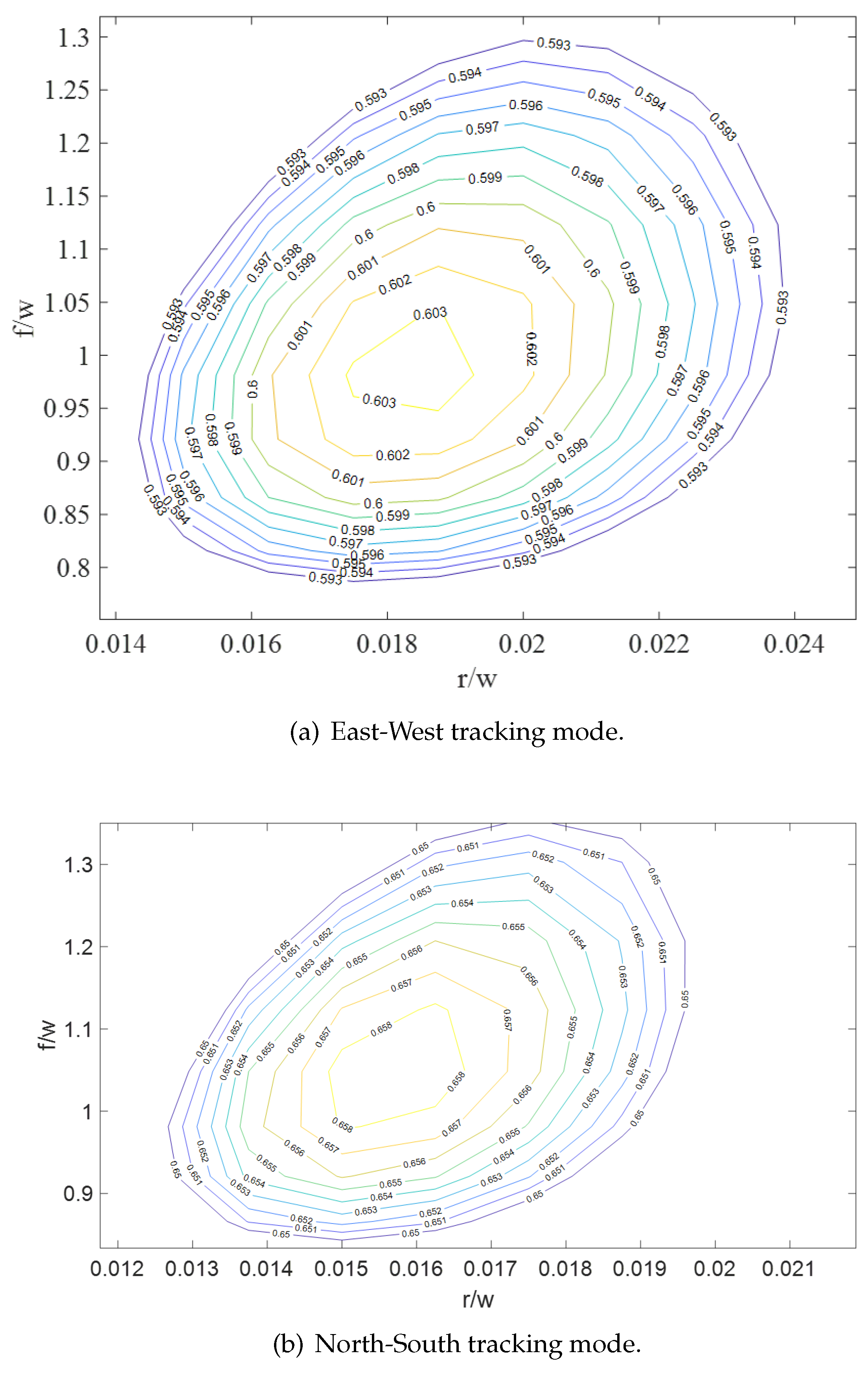

In

Figure 6, the solar trough collector is optimized and the changes in the annual average net efficiency of the cylindrical mirror spliced trough using a cavity receiver under different focal length ratios to half trough width (f/w) and radius of receiver ratios to half trough width (r/w) parameters in the NS and EW tracking modes are calculated. In the NS and EW tracking modes, the optimal net efficiency of the cylindrical spliced mirror trough is 65.8% and 60.3%, respectively. The optimal f/w and r/w values of the NS tracking mode are 1 and 0.018, respectively, and the optimal f/w and r/w in the EW tracking mode are 1.05 and 0.016. When the appropriate solar trough collector design parameters are selected, we achieve the maximum net energy value. Here, the annual average net efficiency is taken as the optimization target, the atmospheric transparency is taken as 0.8, the latitude and longitude are taken as 37.21° and 117° respectively, and the trough width is taken as a fixed value of 4m in the optimization calculation.

3.3. Optimization of the Cylindrical Mirror Spliced Trough

In this paper, we considered three trough solar collector systems using tube receivers and cavity receivers, respectively. The cavity receiver radius is set to match that of the tube receiver. We combined different receivers and mirror types to calculate three different trough collector systems The manufacturing of conventional trough solar collectors with mirrors is more challenging than that of cylindrical mirrors spliced solar collectors. Under the same manufacturing conditions, the slope error of a trough mirror can be three times greater than that of a cylindrical mirror. Given that the slope error of cylindrical mirrors is lower than that of trough mirrors under the same conditions, we set the cylindrical mirror spliced slope error to 1 mrad and the conventional trough mirror slope error to 3 mrad, with other system parameters as shown in

Table 1.

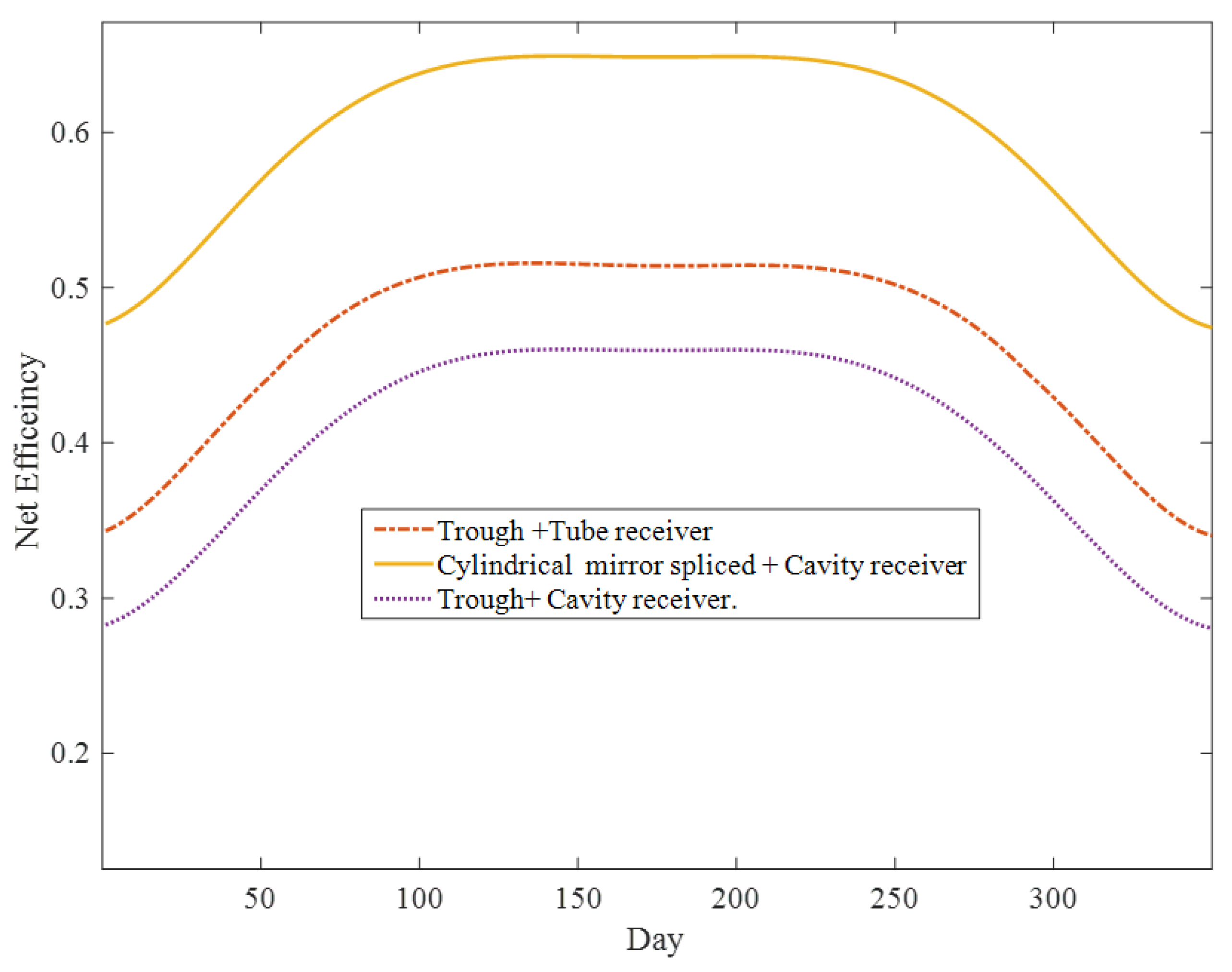

Figure 7 shows the daily average and annual average of intercept factor, optical efficiency, and net efficiency of the three trough solar collector systems during the spring equinox day, summer solstice day, and winter solstice day in the north-south tracking mode. We observed that reducing the mirror slope error brought significant performance improvements with all other parameters unchanged, the trough solar collector systems using trough mirrors performed significantly worse than those using segmented cylindrical mirrors, with a system performance reduction of 28.00%. Therefore, using spliced cylindrical mirrors can significantly improve system performance.

The trough solar collector system with cavity receivers has a lower intercept rate than that of trough collector with tube receiver of the same aperture width and vacuum tube diameter. On the spring equinox day , the intercept factor of the trough system with tube receiver was 92.04% and when we switched it to a cavity receiver, the intercept factor dropped to 61.05% resulting in a reduction of 33.67% and when the trough mirror system was replaced with cylindrical mirror spliced system the intercept dropped to 88.34% resulting in a reduction of 4.00%. However, considering that cavity receivers have lower heat loss and do not require accounting for the receiver’s absorptivity, systems with cavity receivers typically have better net efficiency. In NS tracking systems, among the three combinations, the trough solar collector system with cylindrical mirrors spliced with cavity receivers showed the best net efficiency. On the spring equinox day, its net efficiency was as high as 63.00%. When switched to trough mirror with tube receivers, the net efficiency dropped to 48.89%, a reduction of 22.39% and when switched to trough mirrors with cavity receivers, the net efficiency dropped to 42.37%, a reduction of 41.52%.

The trough solar collector systems with tube receivers require a larger rim angle, which makes them more affected by the incident angle effect, leading to lower system mirror reflectivity and thus lower performance. We evaluated the optical efficiency performance of the three solar collector systems on the spring equinox day and found that the optical efficiency of the cylindrical mirror spliced system was reduced by 1.88% in comparison with the trough mirror system with tube receiver and 24.05% reduction when we switched to trough mirror with cavity receivers. Clearly, when considering factors like reflectivity and transmittance, trough collector systems with cavity receivers are less affected.

In

Figure 7, we calculated the average annual net efficiency of these three trough solar collector systems in 2020 under the north-south horizontal axis tracking mode. Due to the lower mirror slope error of the spliced cylindrical mirror system, spherical and coma aberrations were reduced to negligible levels through system adjustments, resulting in a higher intercept factor compared to conventional trough systems. The combination of cylindrical mirrors spliced with cavity receivers had the highest annual average net efficiency of about 59.24% followed by the combination of trough with tube receivers, with an annual average net efficiency of about 45.97%. From the calculation data, it is evident that the combination of trough mirrors and cavity receivers performed poorly in all cases, indicating that this is not a suitable combination.

In our calculations, the cylindrical mirror spliced trough solar system with cavity receivers showed excellent net efficiency due to lower mirror slope errors, lower incident angle error, and lower heat loss. However, in practical applications, compared to trough systems, cylindrical mirrors spliced systems require rotation and pointing towards the center, resulting in a lower intercept area for spliced cylindrical mirrors of the same width. For a solar system with 16 cylindrical mirrors, when using tube receivers, the actual intercept area is 96.97% due to the larger maximum rim angle. Therefore, in practical use, the impact on intercept area must be considered when using tube receivers. Meanwhile, the intercept area when using cavity receivers is about 99.33% of that of a trough solar system, with the impact being almost negligible.

Table 2.

Daily average intercept factor, optical efficiency and net efficiency of four parabolic trough solar systems at different times in 2020 under the north-south horizontal axis tracking mode.

Table 2.

Daily average intercept factor, optical efficiency and net efficiency of four parabolic trough solar systems at different times in 2020 under the north-south horizontal axis tracking mode.

| |

|

Spring Equinox |

Summer Solstice |

Winter solstice |

Annual average |

Cylindrical spliced

+

Cavity receiver |

Intercept factor |

85.34% |

88.31% |

70.31% |

82.57% |

| |

Optical efficiency |

72.46% |

75.05% |

59.53% |

70.09% |

| |

Net efficiency |

63.00 % |

64.86 % |

47.27 % |

59.24 % |

Trough

+

cavity receiver |

Intercept factor |

61.05% |

64.72% |

46.16% |

58.46% |

| |

Optical efficiency |

51.92% |

55.11% |

39.13% |

49.7% |

| |

Net efficiency |

42.37 % |

45.96 % |

27.91 % |

39.87 % |

Trough

+

cavity receiver |

Intercept factor |

92.04% |

94.12% |

79.21% |

89.61% |

| |

Optical efficiency |

73.85% |

75.81% |

62.7% |

71.77% |

| |

Net efficiency |

48.89 % |

51.4 % |

33.87 % |

45.97 % |

4. Conclusion

In conventional parabolic trough solar collector , the reflector is a complete parabolic trough mirror. This type of mirror tends to have significant fabrication errors, leading to larger focal spots and reduced optical efficiency. In this study, we proposed a novel spliced cylindrical mirror trough solar system. Building on the previously developed parabolic trough system model, we introduced a new ray-tracing method to investigate the system’s performance. By adjusting system parameters, we reduced spherical and coma aberrations, making their impact on the system almost negligible. This new spliced system consists of multiple strip-like cylindrical mirror reflectors, each aligned along a parabola line. The normal vector of each cylindrical mirror is consistent with the parabola normal vector at its installation point. The receiver is placed at the focal point formed by the centers of the cylindrical mirrors. Compared to trough mirrors, cylindrical mirrors are easier to manufacture and have lower surface slope errors under similar production conditions. Although cylindrical mirrors introduce some aberration in the reflected light, the efficiency loss is significantly outweighed by the benefits of reduced slope errors. Overall, the novel cylindrical mirror spliced system outperforms conventional trough systems in terms of performance.

Building on the method previously used to evaluate the performance of parabolic trough systems, we introduced a new ray-tracing method and developed a MATLAB code based on the relevant equations. By comparing it with the cone method and SolTrace software, we validated the accuracy of the method. Using the MATLAB program, we performed calculations and optimizations for the spliced cylindrical system with a cavity receiver, determining the optimal values of r/w and f/w for maximum net efficiency. We combined conventional trough mirrors and cylindrical mirrors with both tube and cavity receivers, and evaluated the performance of three different systems by calculating their intercept factor, optical efficiency, and net efficiency. The conclusions of this study are as follows:

Under NS tracking modes, the optimal net efficiencies for the spliced cylindrical solar trough system with a cavity receiver is 60.3%. The optimal f/w ratios is 1 and the optimal r/w values is 0.018.

The trough system with a cavity receiver generally has lower intercept factors and optical efficiency compared to systems with tube receivers. However, due to reduced heat loss from the receiver and lower incident angle errors, the net efficiency is higher. The annual net efficiency of the segmented cylindrical mirror system with a cavity receiver is 18.74% higher than that of the trough with a tube receiver, although the optical efficiency is 2.00% lower.

The spliced mirror must always point toward the center of the cylindrical surface, the effective intercept area changes with the incident angle during solar tracking. The effective intercept area for systems with tube receivers is 96.97%, while for systems with cavity receivers, it is approximately 99.33% of the effective reflective area of conventional mirrors, resulting in minimal impact on performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B. and H.W.; methodology, L.B.and H.W.; software, L.B.and VIAN, M.; validation, L.B. and VIAN, M.; formal analysis, L.B. and VIAN, M.; resources, H.W.; data curation, L.B. and VIAN, M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B. and VIAN, M.; writing—review and editing, L.B. and VIAN, M.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W.