1. Introduction

The importance of using solar energy has increased in order to find solutions to the increasing energy needs and to eliminate the damage caused by fossil fuels to the environment [

1,

2]. Just as electricity can be produced from solar energy through solar panels, which are increasingly used in industrial applications [

3], heat energy production is also possible through solar collectors. Solar collectors, which have become widespread in recent years, play a very important role in converting the sun's radiant energy into thermal energy [

4,

5]. Incident rays and reflected rays are important factors that determine the efficiency of solar collector-based system. Incident ray constitutes the original ray beam emitted from the sun and reaching the collector surface. This energy-carrying ray hits the surface at an incidence angle. The intensity of the incident ray expresses the amount of energy per unit area and varies depending on factors such as the position of the sun and the atmospheric conditions. The reflected ray is the part of the incident ray that returns after hitting the surface. Reflection can be specular or diffuse depending on the properties of the surface. In specular reflection, the ray is reflected in a single direction, while in diffuse reflection, it is scattered in different directions. According to the laws of reflection, the reflection angle is equal to the incidence angle, and the incident ray, reflected ray and surface normal are in the same plane.

Studies on new generation solar collectors have increased in recent years to benefit more efficiently from solar energy. Improvement studies on the generally used flat plate solar collectors are ongoing [

6]. However, studies on concentrator systems for higher efficiency are also gaining importance and parabolic trough collectors stand out in this field [

7,

8,

9]. Apart from the development of new approaches in the design of these collectors [

10,

11], various methods are also being investigated to improve the performance of parabolic trough collectors. Improvement of absorber surface designs [

12,

13], use of nanofluids [

14,

15,

16] and examination of different heat transfer fluids [

17,

18] are among these methods. In addition to studies on increasing solar collector efficiency using different materials, there are also solar collector design studies with different geometric structures. Fractal structured solar collectors, which have been increasingly used in recent years and are the leading design studies, are based on structural theory [

19,

20]. Application of the basic principles of fractal geometry to the design of solar collectors [

21] and the presentation of a new fractal solar collector design based on structural theory [

22] are examples of theoretical studies. These studies show that fractal structured collectors can be more efficient than flat collectors. Absorbers and their locations in the aperture region of the collectors are main problems of the design of solar collectors. A fractal solar collector is obtained by fractal placement of absorbers on a parabolic concentrator plane in the form of toroidal tubes. Studies have been reported that heat transfer and fluid flow properties are increased in solar collectors with fractal geometric structures compared to flat-structure collectors [

23,

24,

25]. Other studies on solar collectors with fractal geometric structures have reported an increased thermal efficiency [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Studies to improve thermal performance and to reduce the cost of fractal solar collectors through innovative production techniques based on advanced materials have increased in recent years [

30,

31,

32].

In addition to parabolic concentrators, compound parabolic concentrators (CPC) [

33] and Fresnel lens technology [

34] also play an important role in solar energy applications. Linear Fresnel reflectors are also being investigated for increased efficiency [

35]. Performance analysis of parabolic trough collectors under non-uniform solar flux conditions has been conducted [

36,

37]. Parabolic-based fractal structured solar collectors have the potential to offer higher efficiency compared to traditional designs. Such designs increase the heat transfer surface area and optimize the fluid flow [

38]. As a result, studies to increase the efficiency of solar energy systems focus on fractal structured collectors, advanced parabolic concentrators, nanofluids and innovative materials. The development of concave-based fractal structured solar collectors with different absorber surface designs is an important research topic in this field. Radiative thermal analyses and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations [

39] play a critical role in evaluating the performance of these new generation collectors.

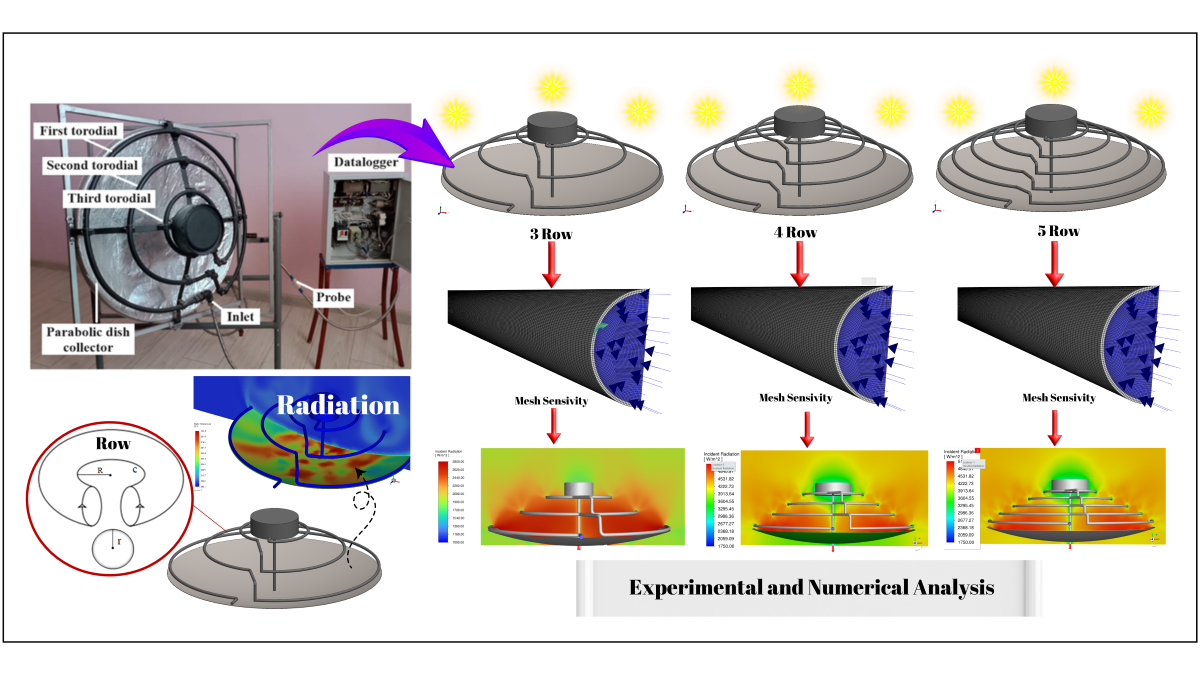

In this study, the thermal properties of improved toroidal fractal solar collectors with parabolic dish were evaluated. In addition, it is investigated how different numbers of toroidal absorbers in the fractal arrangement on the parabolic concentrator affect the efficiency of the proposed solar collector. In the experimental study conducted by [

40], positive results were observed in obtaining hot water at low solar radiation thanks to the fractal arrangement of 3-row toroidal absorbers on a parabolic concentrator. The methodological basis for determining the transmission-absorption capacity in the study was taken as the basis of the power balance equation in the solar radiation heating mode with zero water consumption. It was found that the obtained energy indicators and the maximum water temperature significantly depend on the dimensions of the fractal absorbers. It was stated that in the spring and autumn periods, it is necessary to increase the absorption area in order to heat the water to higher temperatures and to provide the desired hot water flow. In order to increase the radiation surface absorption area stated in the experimental findings of the 3-row fractal structure, firstly the experimental results of the 3-row fractal structure were compared with the numerical analysis data. The 96.84% surface absorption area obtained from the 3-row toroidal fractal structure was also applied to the 4-row and 5-row toroidal fractal structures and the numerical results obtained were presented comparatively in tables and graphs. When the numerical analysis results were compared, it was seen that the highest temperature increase was in the 5-row toroidal structure. With this proposed study, it was revealed that the dish-integrated fractal solar collector design can provide high efficiency in solar water heating applications.

2. Design and Analysis

The goal of thermal solar collectors is to absorb as much of the incoming light as possible and minimize the reflection. For this reason, absorber surfaces are usually provided with special coatings, usually black or dark in color. However, some light is inevitably reflected, and the amount and direction of the reflected light affects the collector's efficiency. Designers use a variety of techniques to reduce or redirect the reflected light. For example, selective surface coatings minimize heat loss while absorbing light. Some advanced designs use secondary reflectors or concentrators to recapture the reflected light. Concentrators direct incoming sunlight to a point or line, and one of the main types of concentrators, a parabolic dish-shaped reflector, can be used to focus the rays to a single point. The brightness and roughness of an object's surface directly affect how light is reflected. For example, a matte surface reflects the incoming light evenly in all directions, while shiny surfaces provide a more focused reflection. Therefore, directing the incoming and reflected rays is of critical importance in optimizing solar collectors. Thus, maximum energy conversion can be achieved, and the overall efficiency of the system can be increased.

In this section, the design, working principle and radiative thermal analysis of the solar collector developed in the concave dish-based fractal structure are reported. The design criteria are based on the experimental thermal behavior results of the 3-row fractal structure collector with a concave dish reported in [

40], and their numerical analysis is carried out as 4-row and 5-row structures. In the radiative thermal performance analyses, radiative heat flux, radiation temperature data and flow dynamics are obtained using the ANSYS-Fluent program.

2.1. Experimental Setup

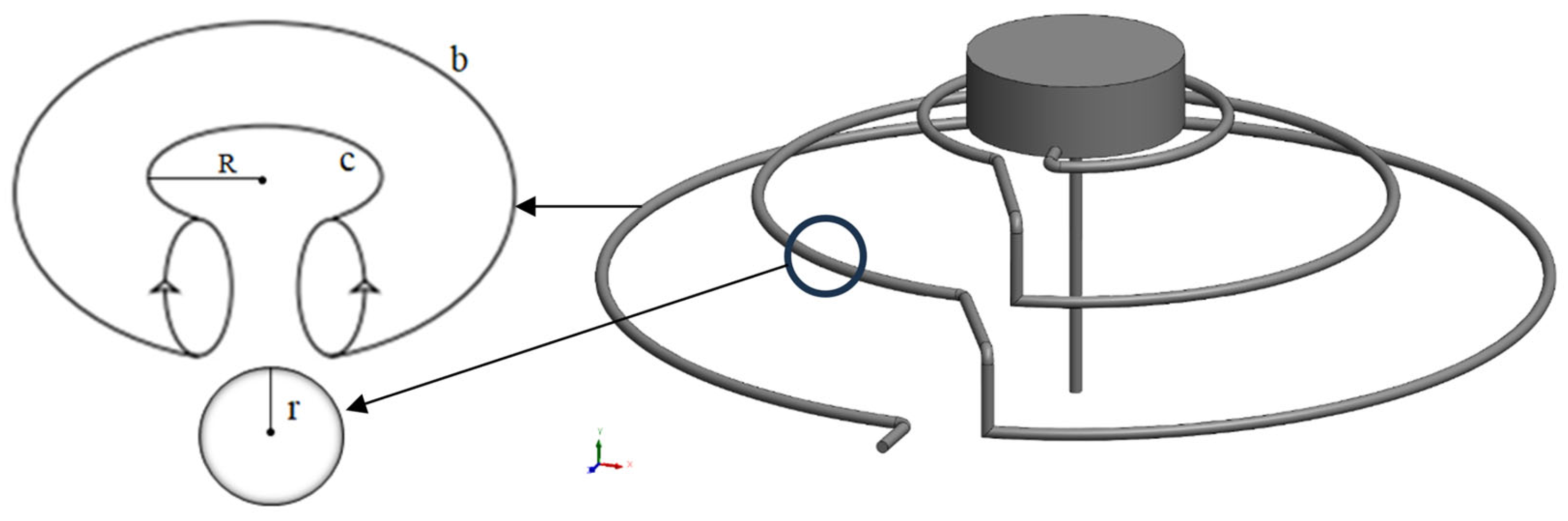

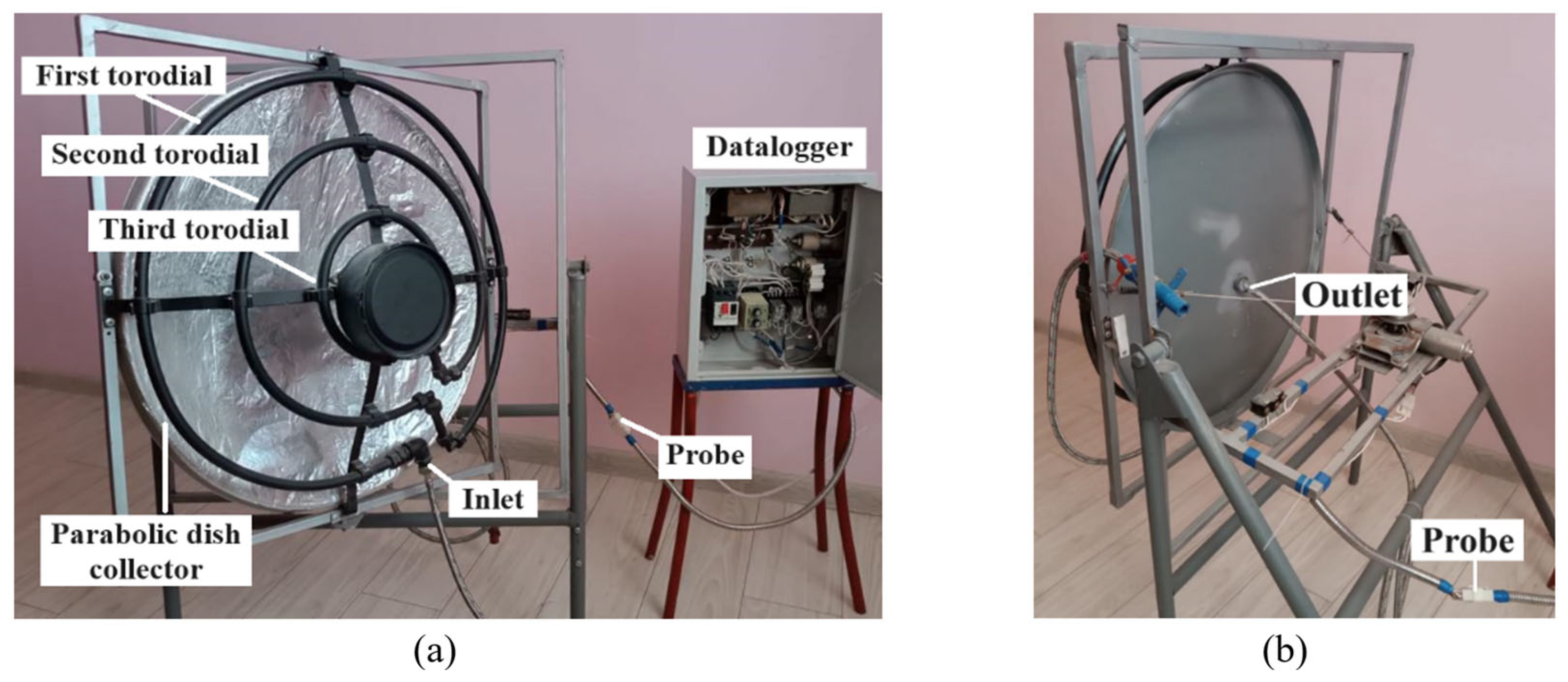

Experimental studies were carried out in Kazakhstan/Turkestan (68.23° latitude and 43.3051° longitude) under the climatic conditions of 1-March 2023, using a 3-row toroidal fractal structure. The collector with a 3-row toroidal fractal array used in the experiments (shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) was designed with an absorber structure with a highly selective coating [

41]. In the design phase, the formula for the surface area of the absorber depending on the radius was calculated with equation (1). In equations (1-5),

R is the distance from the center of the circle to the axis of rotation of the absorber;

r is the radius of the absorber;

c is the inner diameter; and

b is the outer circle. As seen from equation (1), the system capacity can be changed depending on the number of fractal arrays according to the circle dimensions of the toroidal structure [

40].

After calculating the radii along the circles of the absorber, the surface area (

A) and volume (

V) of the absorber are calculated by equations (6) and (7), respectively, by substituting the expressions obtained for the radii in the standard formulas.

The water transferred to the system is heated by the sun rays while passing through the first toroidal fractal. In this case, the heat losses of the first fractal increase, while reaching the second fractal by convection and providing an additional thermal energy source. Thus, the heat losses of the first and second toroids serve as an additional thermal energy source for the third toroidal. The heating water is removed from the system by rising from the toroidal fractal pipes, so the water temperature in each fractal absorber is different. Meanwhile, the parabolic dish concentrates the sun rays falling on the surface area to the focal points on the fractal, causing thermal losses to decrease. In this way, the thermal energy obtained is transferred from the focusing region to the working fluid and sent to the thermodynamic circulation. The speed of the water entering the toroidal pipe is 0.3 m/s at 20 ℃ temperature and the pipe is coated with a 10 mm galvanized layer in the experimental setup. In the experiment, the temperature data of the water entering and leaving the collector were transmitted to the datalogger for each minute with a K-type temperature sensor and the data were recorded for 60 minutes.

2.2. Numerical setup

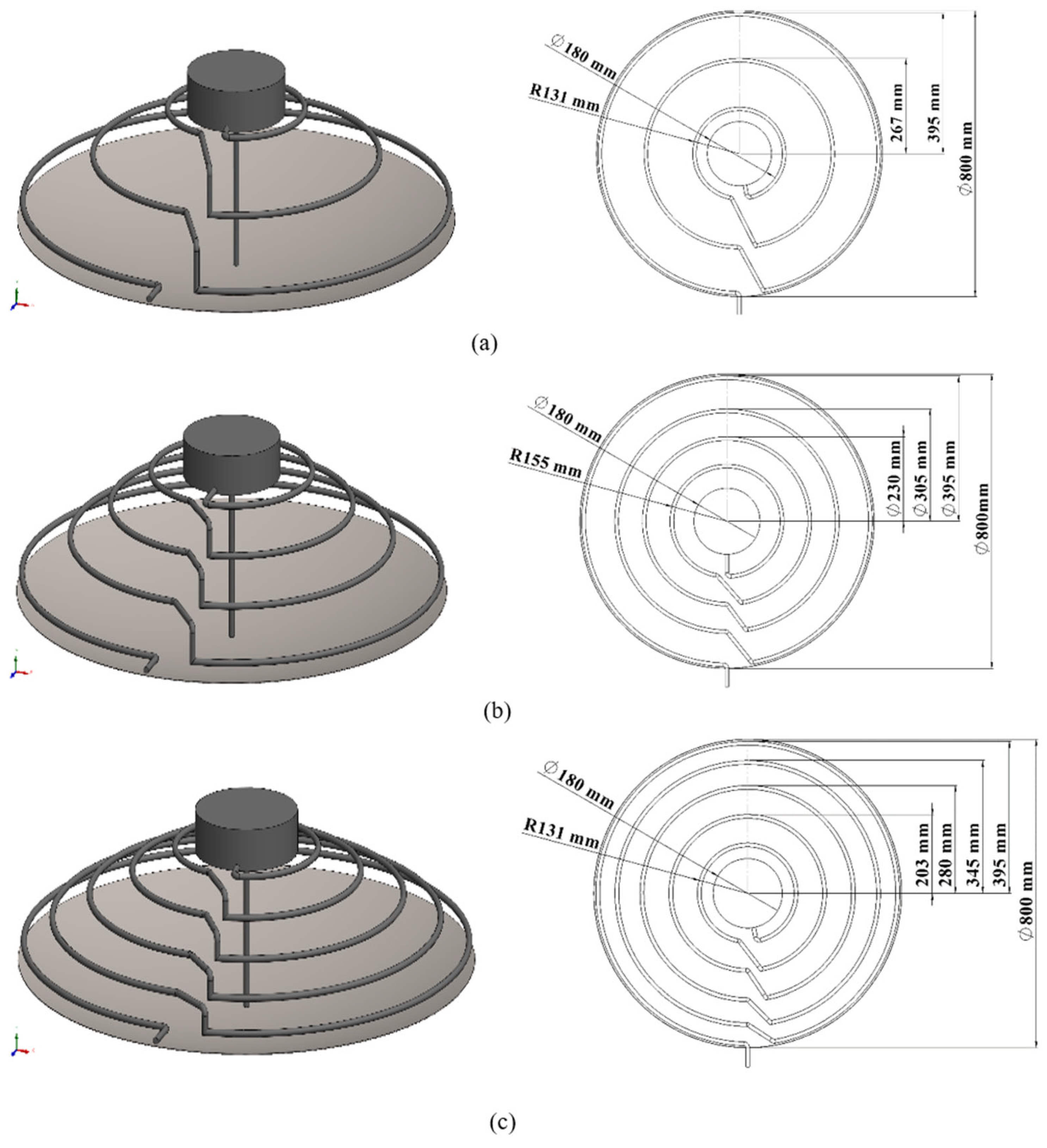

In the proposed study, a parabolic dish was placed so that the thermal solar collector in the fractal array could benefit more from the reflected light. The radiative heat transfer analysis results of the 10 mm diameter 3-row, 4-row and 5-row toroidal absorbers designed on the parabolic concentrator were compared in the study. The Spaceclaim program was used while modeling the geometry of the design. The dimetric and upper section views of the model designed as 3-row, 4-row and 5-row structure are given in

Figure 3.

ANSYS Fluent software was used to solve radiation heat transfer within the scope of numerical analysis. It is known that ANSYS Fluent software offers various radiation models to simulate radiation heat transfer including Discrete Transfer Radiation (DTR), P-1, Rosseland, Surface to Surface (S2S) and DO Radiation Model. While DO Radiation model was preferred for the analysis due to its capabilities and advantages, the turbulent terms of the flow equations were solved using k-omega SST viscous model. In the modeling, solar radiation values were automatically used according to the conditions in which the experiments were conducted. As previously stated, the experiments were conducted in the climatic conditions of March 1, 2023, at 68.23° latitude and 43.3051° longitude of Kazakhstan. Thermophysical properties of the materials used in the analysis are given in

Table 1.

2.3. Discrete ordinates radiation model

The Discrete Ordinates Radiation Model is a powerful and widely applicable model for simulating radiative heat transfer and can work over a wide range of optical thicknesses, including optically thin and thick media. Another key advantage is that it can also handle anisotropic scattering and non-gray radiation. The radiative transfer equation (RTE) is solved for a finite number of discrete solid angles, each associated to a fixed vector direction in the global cartesian system. It can accurately model the directional nature of radiation and the wavelength dependence of radiative properties, which is desirable for many engineering applications. It can also consider the effects of participating media, such as gases and particles, on radiative heat transfer. The model is based on the discretization of the RTE into a set of interconnected equations for a finite number of discrete solid angles. The accuracy of the DO model depends on the number of discrete ordinates used; higher numbers generally provide better accuracy but increase computational cost. However, although it generally requires more computational power than some other radiation models, it offers superior accuracy and flexibility in a wide range of applications [

43,

44].

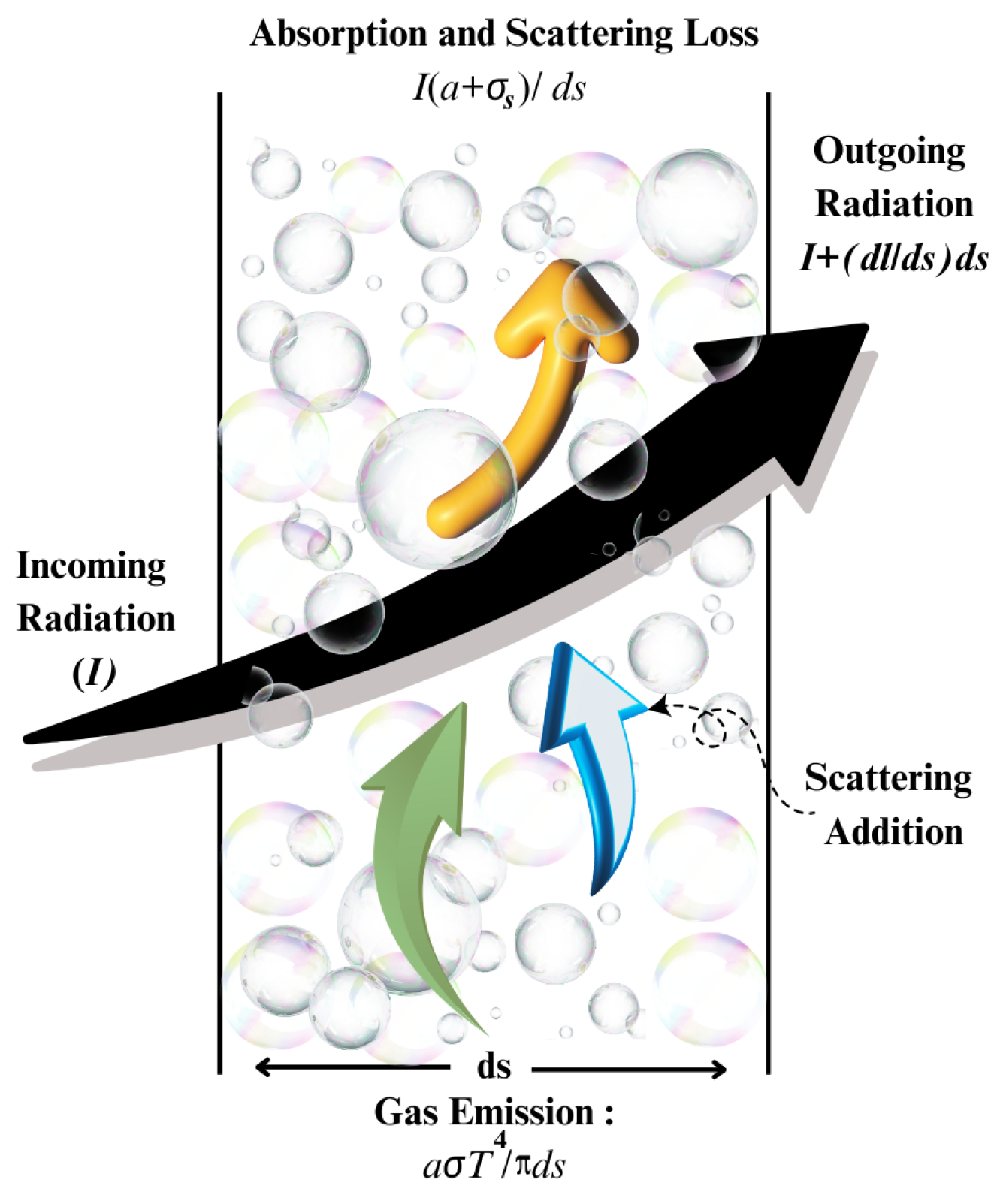

In an absorbing, emitting and scattering medium, the

position in the

direction is given in equation (8). In the equation, σ represents the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.669 x 10⁻⁸ W/m² K⁴). Here,

T is local temperature,

Φ is phase function,

a is absorption coefficient,

is solid angle,

position vector,

is direction vector,

is scattering coefficient,

is scattering direction vector,

s is path length and (

a+

) is optical thickness or opacity of the medium.

The refractive index

n is an important parameter when considering radiation in semi-transparent media.

I defines the radiation intensity, which depends on the

position and

direction. This index is a fundamental factor affecting the speed and direction of light propagation in the medium.

Figure 4 visualizes the process of heat transfer by radiation in detail. In this representation, the radiation intensity, expressed by the symbol

I, attracts attention with its spatial and directional dependence. In particular, the dependence of

I on the

position and

direction shows how the radiation propagates and changes in three-dimensional space. This dependency contributes to more accurate modeling of heat transfer in complex geometries and heterogeneous environments by examining how radiation behaves at different points and in different directions.

The solution technique used in DO radiation model is similar to the methods applied in the fields of fluid dynamics and energy transfer. The distinctive feature of this model is that it evaluates the RTE in the

direction as a field equation and does not use the ray tracing technique. Instead, RTE uses a limited number of discrete solid angles while solving equations (9). Each solid angle is matched to a specific

vector direction in the cartesian coordinate system (x, y, z). Thus, by solving a transport equation for each direction, the total number of solved equations is equal to the number of determined directions. Therefore, this method makes the solution of the problem more systematic and organized and offers the flexibility to balance the sensitivity and computational load of the model. Therefore, it significantly increases the adaptability of the DO model to various geometric structures and complex radiation scenarios, thus expanding the application area of the model.

Equation (10) is used to calculate the spectral intensity

for RTE. Here

represents the black body intensity given by the Planck function. In addition,

is the spectral absorption coefficient and λ is the wavelength. When calculating the scattering coefficient, it is assumed that

n is independent of the wavelength and the scattering phase function. (a σ T

4 /

)

The fraction of the radiant energy emitted by a black body,

, is given in equation (11). Here, in a medium with a refractive index of

n, at a temperature of

T, the wavelength range is between λ

1 and λ

2 are the wavelength limits of the band. The total intensity

in the

direction at the

position is calculated using equation (12).

The energy matching of the DO model is shown in equation (13). where

,

, κ is the absorption coefficient and

is the control volume. The coefficient

and the source term

are due to the discretization of the convection and diffusion terms and the non-radiative source terms.

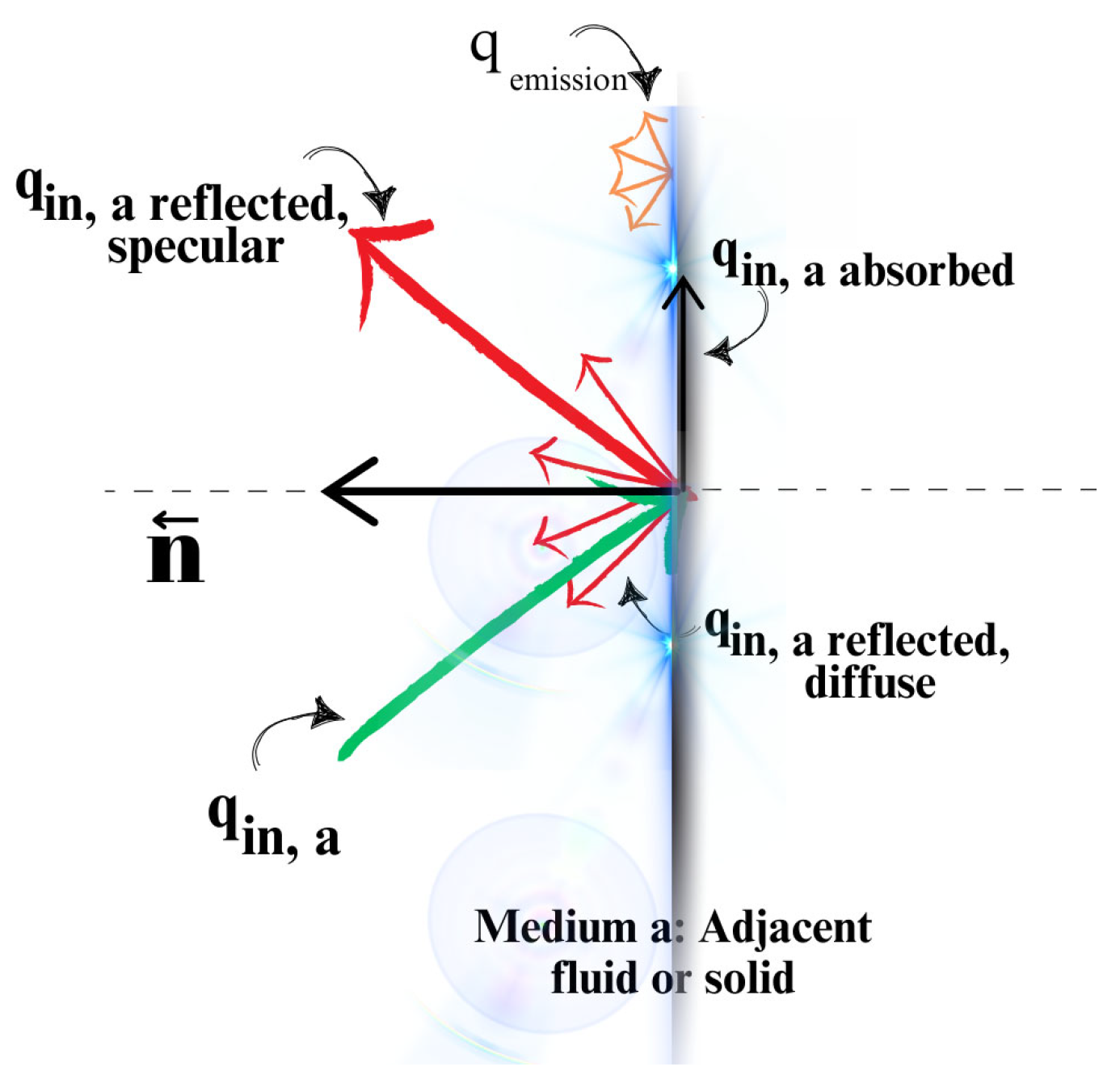

As seen in

Figure 5, a schematic representation of the radiation on an opaque wall is presented. The DO model allows opaque walls to be modeled under various conditions. The model can consider walls in two different scenarios; first, walls located inside a space and surrounded by liquid or solid regions on both sides; second, walls located outside the space and in contact with a liquid or solid region on only one side. Another important feature of the DO model is that it can evaluate the properties of walls in different ways in radiation calculations. If gray radiation calculation is performed, the walls are considered gray, i.e. they are assumed to exhibit the same radiation properties at all wavelengths. However, if the non-gray DO model is used, the walls are considered non-gray, which means that the radiation properties can vary depending on the wavelength. This flexibility allows the DO model to perform realistic simulations considering various radiation problems and different material properties.

3. Results and Discussions

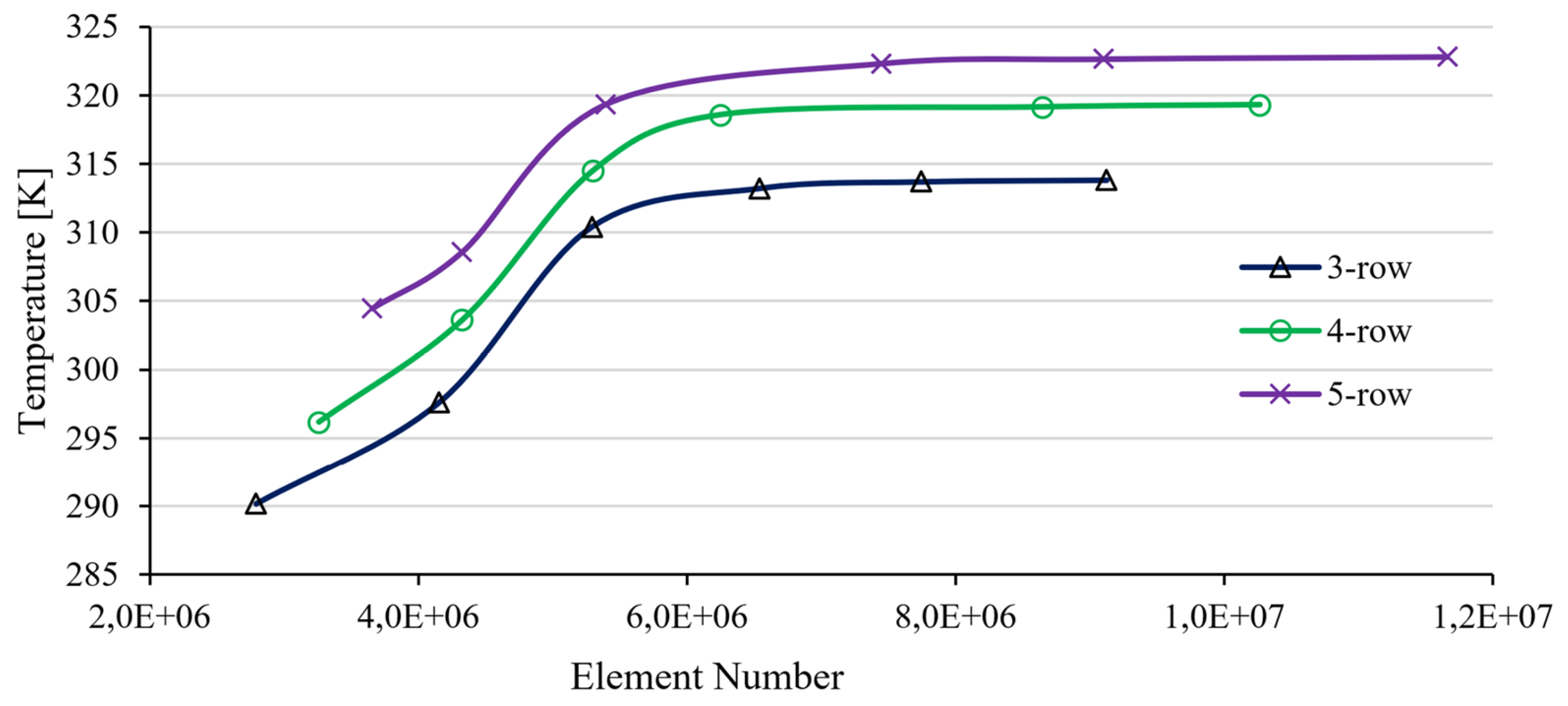

In this study, the thermal behavior of an improved fractal solar collector integrated with a parabolic dish was investigated both experimentally and numerically. In experiments conducted in the Turkestan region of Kazakhstan, the fractal structure was fed with mains water and the effects of heat transfer by radiation and convection were observed. The collector used in the experiment consists of a 3-toroidal structure. While modeling the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) of the system, a fully structured computational grid was created in order to correctly define the collector geometry together with the inlet and outlet pipes. Mesh sensivity analysis was performed to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the numerical analysis. This analysis was performed to show that the solution was independent of the mesh density and that the results did not change significantly according to the mesh quality. Analyses were performed with six different mesh densities using ANSYS Fluent. The outlet temperature parameter was examined to evaluate mesh sensitivity. As seen from

Figure 6, the results become more sensitive as the number of elements of the mesh structures is increased. However, after a certain point, the effect of increasing the number of elements on the results decreases. This shows that the mesh structure is sufficient for the optimum solution between computational cost and result accuracy. During the creation of the computational grid, special attention was paid to the regions near the solid walls where the inlet-outlet and flow are located and where thermal changes are expected.

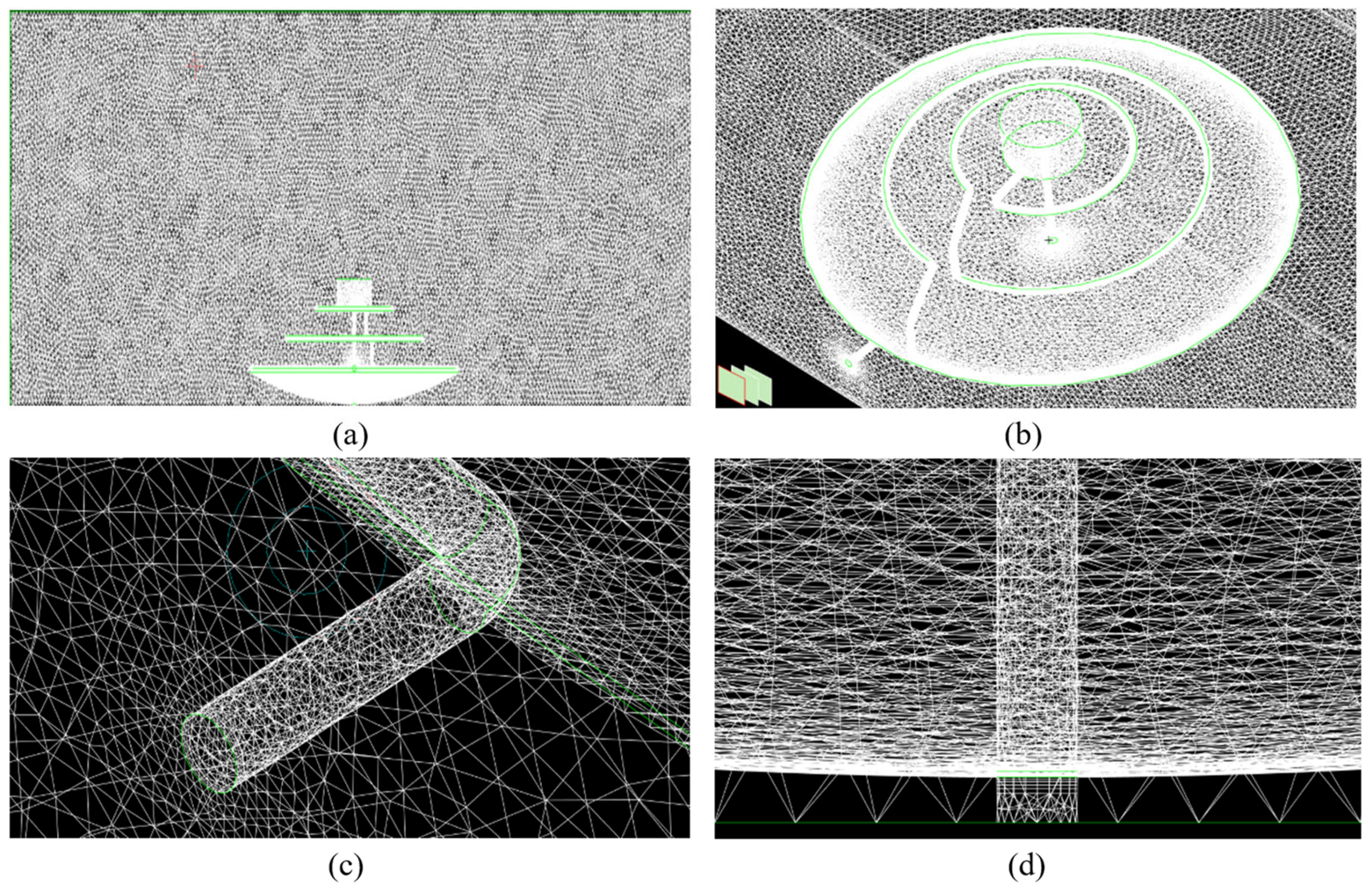

The model mesh network of the 3-raws fractal collector defines (a) air and liquid flow dynamics, (b) the collector area with parabolic dish (c) and (d) specifically the inlet and outlet pipe regions as seen in

Figure 7. The number of tetrahedral and hexagonal elements created in these grids was seen to be 7.7 million, 8.6 million and 9.1 million elements for 3-row, 4-row and 5-row toroidal structures, respectively.

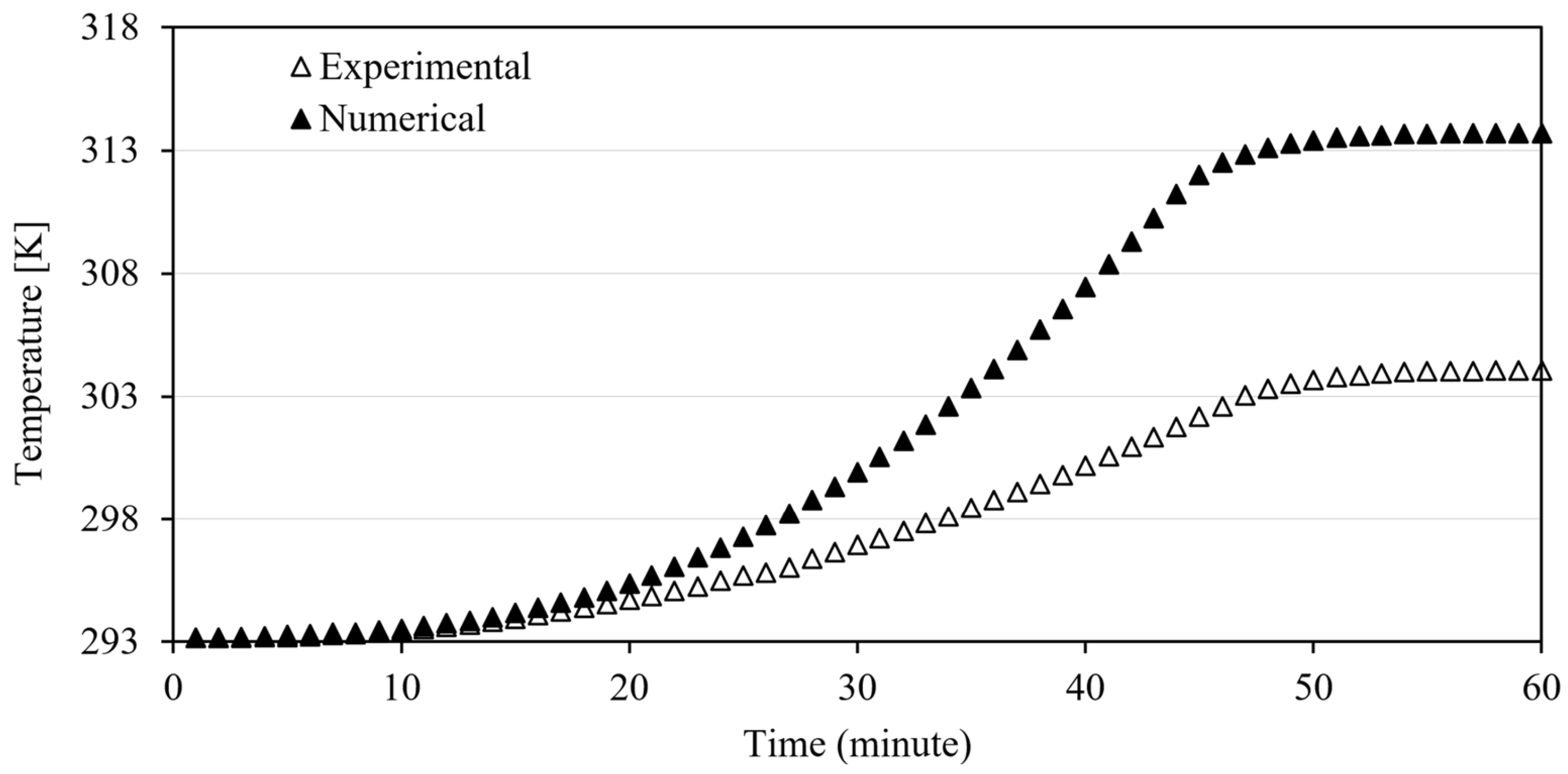

The experimental and numerical analyze results of one hourly data of the outlet water temperatures of the proposed design were compared and the distributions of these data depending on time are given in

Figure 8. In both curves, it is seen that the increase rate is quite slow at the beginning and approximately 20 minutes later the increase rate starts to rise significantly. In the third quarter, it is seen that the increase rate starts to slow down and the increase is almost asymptotic towards the last minute. This situation shows that the heat transfer rate coming from radiation is effective alone until the first 20 minutes and then the parabolic dish effect has a positive contribution. The reasons for the resistance in the temperature increase seen in the third quarter can be listed as; cold weather conditions in March, the fact that infrared radiation (direct IR) can be more than visible light, especially in winter months or when the sun angle is low, and the effect of wind speed on heat loss. It was calculated that there is a 3.16% difference between the outlet water temperatures. This increase seen in the numerical results is due to the neglect of wind speed, radial and other thermal losses in the simulations. In particular, it is assumed that the parabolic dish focuses on the sun rays and that there is no loss in radiation values. In line with these assumptions, the dish surface is modeled as opaque and smooth, and the internal emissivity and diffuse fraction values are assumed to be zero. Being opaque means that the material does not allow light to pass through, but either reflects or absorbs it. Smoothness indicates that the surface does not contain any protrusions or indentations even at the micro level. A zero internal emissivity indicates that the dish does not emit any heat from the inside, while a zero diffuse fraction indicates that the surface does not scatter the incoming light at all but reflects it all regularly. These features allow the parabolic dish to direct the light precisely towards the focal point. In addition, the direct visible and direct infrared (IR) values are also entered as zero within the absorptivity topic. A zero direct visible absorptivity indicates that the dish does not absorb any incoming light in the visible light spectrum, but completely reflects it. However, in real conditions the high "Direct IR" absorptivity means that the collector can capture the infrared energy from the sun and convert it into heat. This indicates that the dish can use some of the radiation to heat itself, but this effect is neglected in the simulations. As a result, these idealized assumptions allow us to analyze the maximum potential performance of the system, although the performance in real conditions deviates slightly from the ideal case.

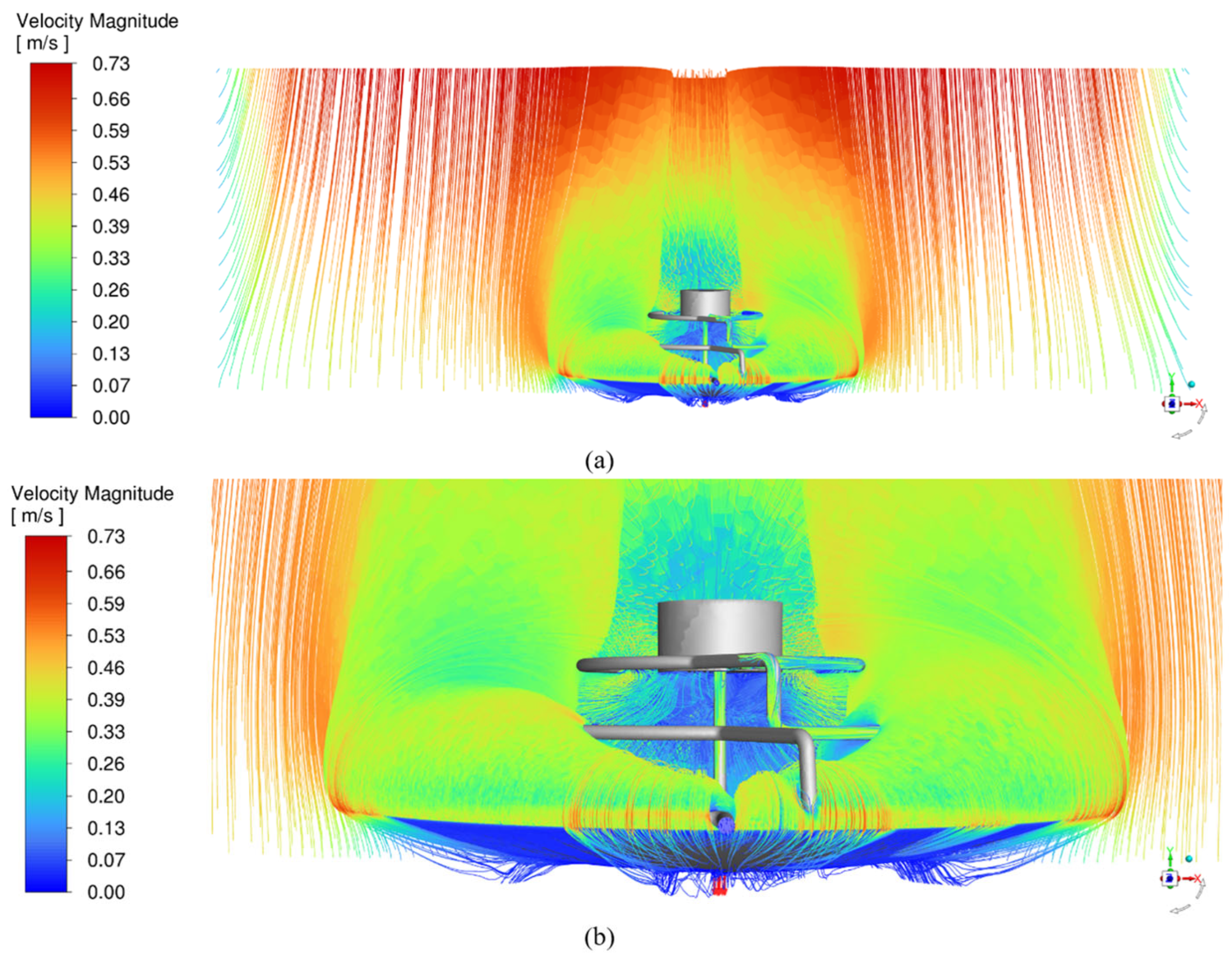

The hydrodynamic performance of the fractal collector system is given in

Figure 9.

Figure 9(a) shows the entire modeled domain. When the flow velocity dynamics experienced around the system and the dish are examined in detail in

Figure 9(b), it is seen that the fluid velocity varies between 0 m/s and 0.73 m/s. This wide velocity range reflects the complex flow dynamics in the system. In the inner parts of the fractal collector, especially in the lower and middle fractals, the blue and light blue colors, where the velocity is generally low, are observed between 0-0.20 m/s. These low velocity regions increase heat transfer by allowing the water to absorb heat for a longer period of time. Higher velocities are observed at the outer edges of the fractal structure and especially at the upper parts, in green and yellow colors, between 0.33-0.53 m/s. These high velocity regions indicate that the heated water moves rapidly upwards, which confirms the principle of natural convection. At the bottom of the system, at the entry point, yellow and orange colors are between 0.46-0.66 m/s, and relatively high velocities are observed. This situation shows that cold water enters the system rapidly. Similarly, high velocities are observed at the top, in other words, at the exit point, which means that the heated water is effectively removed from the system. Complex flow patterns and vortices are observed around the fractal structure, especially in the lower and middle toroidal. This turbulent flow contributes to the efficiency of the system by increasing heat transfer. The high velocity values observed in orange and red colors between 0.59-0.73 m/s in the regions close to the inner surface of the parabolic dish, and the air currents created by the dish, are understood to affect the overall heat transfer performance of the system. As a result, the numerical velocity distribution analysis shows that the fractal collector system operates effectively from a hydrodynamic point of view. The low velocity regions optimize the heat transfer, while the high velocity regions provide efficient transport of heated water. In addition, the observed turbulence and vortices further increase the heat transfer and contribute to the overall efficiency of the system. system.

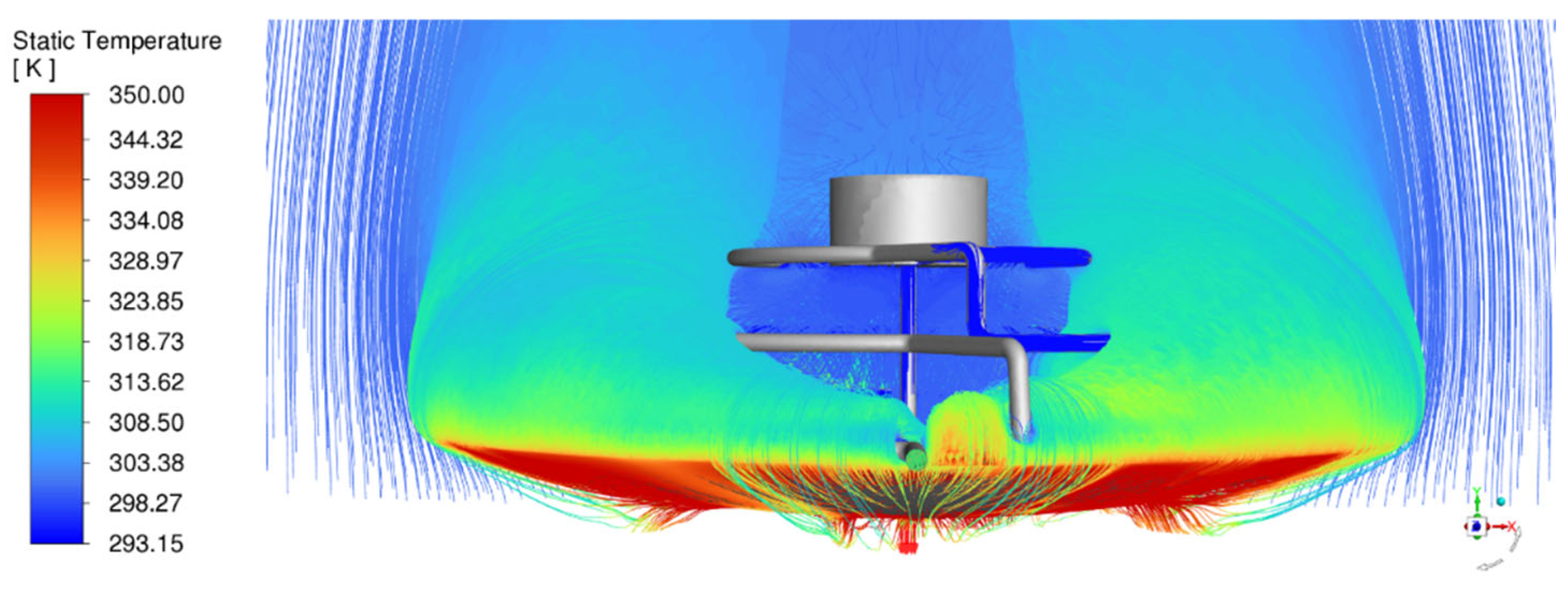

Figure 10 shows the temperature distribution in the collector system consisting of a parabolic dish and three toroidal fractals, as a result of the numerical analysis. The red region (around 350 K) seen on the parabolic dish surface indicates the area where the sun rays are concentrated. The simulation results show that the low internal emissivity value increases the heat retention capacity of the dish and the temperature at the focal point increases up to 350 K. This finding is consistent with the high temperature increase in the experimental study and confirms the energy efficiency of the system. However, the diffuse fraction effect shows that the dish surface scatters the incident light minimally and mostly reflects specular. The intense red region (around 350 K) at the bottom of the parabolic dish confirms that the rays are effectively focused. This is consistent with the high heat transfer rate observed in the experimental study and proves the optical efficiency of the system. In the simulation, it is understood that the dish minimally absorbs and mostly reflects the incoming visible and infrared radiation. Simulation results show that these low absorptivity values prevent the dish from heating up and a large portion of the incoming energy is directed to the fractal collector. Therefore, it is understood that it is consistent with the high energy transfer rate observed in the experimental study. However, the temperature distribution in the collector clearly shows that the gradual temperature increases from the lower fractal to the upper fractal (approximately from 293 K to 350 K) confirms the heat transfer mechanism observed in the experimental study. This supports that each fractal level provides additional thermal energy to the next level. The flow lines show the movement of water in the system. Starting from the lower fractal, the water moving upwards heats up at each fractal level. This flow model confirms the thermodynamic circulation observed in the experimental study. The blue regions around the parabolic dish show the heat exchange with the environment. However, the high temperature at the focal point (350 K) shows that the dish minimizes thermal losses. As a result, the optical properties of the parabolic dish (low internal emissivity, diffuse fraction and absorptivity) and the thermal performance of the fractal collector are consistent with the experimental study.

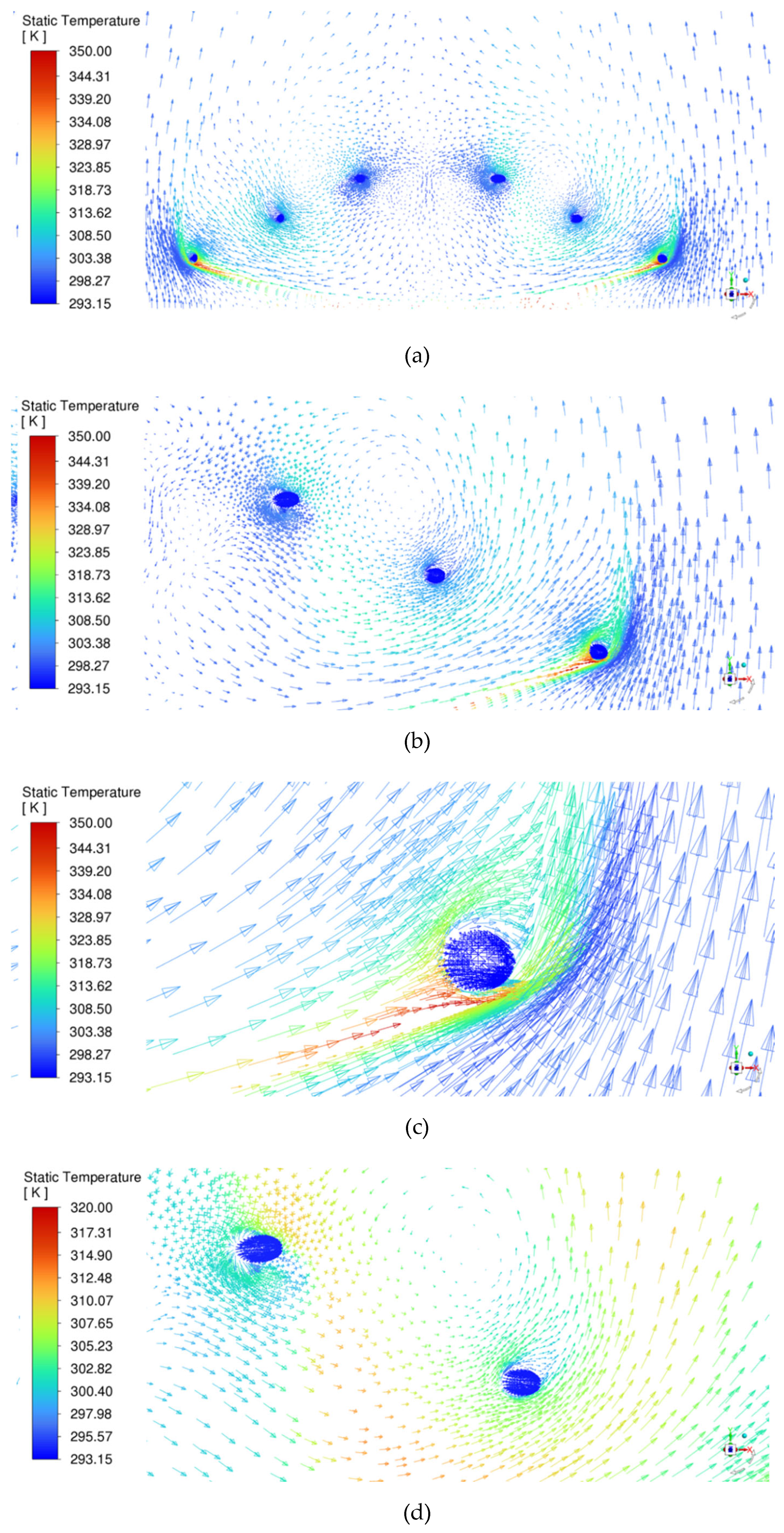

The velocity vectors colored according to the static temperature in the middle plane are given in

Figure 11(a).

Figure 11(b) allows us to understand the thermal and hydrodynamic properties of the fluid motion and temperature distribution in the middle plane of the fractal collector system in an integrated manner. The temperature scale varies between 293.15 K and 350 K. This shows that the system can increase the water temperature by approximately 57 K. In addition, the velocity vectors clearly show the complex flow patterns in the system. The highest temperatures are observed in the red-orange areas in the regions corresponding to the focal points of the parabolic dish. This confirms that the dish effectively concentrates the sun rays. In general, it is observed that the flow velocity also increases in the red and orange high temperature regions. This shows that the heated water moves faster and thus the heat transfer capacity of the system increases. In

Figure 11(c), where the velocity vectors and temperature distribution are given for the first toroidal, it is seen that there are vortices and turbulence regions around the system. Significant temperature gradients are observed inside and around the fractal structures. These gradients indicate that heat transfer is continuous and there is an effective heat distribution in different regions of the system. The complex structure of the fractal geometry causes the fluid to spread in different directions and to merge again. This provides a large surface area for heat transfer and increases the overall efficiency of the system. In

Figure 11 (d), the flow dynamics, temperature distribution and micro-level operation of the system around the fractal collector top and middle toroids are given in detail. The temperature scale between 293.15 K and 320 K allows us to understand the micro-level thermal and hydrodynamic properties of the system. This shows that there is a temperature increase of approximately 27 K around the toroid and confirms the effective heat transfer capability of the system. The velocity vectors show that complex and regular flow patterns are formed around the toroid. In particular, the vortices formed around each toroid represent the turbulent flow that increases heat transfer. In the center of both toroidal structures, low temperature is observed in blue. This shows that cold water passes through the toroidal and heats up. In addition, towards the outer surface of the toroidals, the temperature increases with green and yellow colors and upward moving vectors are observed in the upper parts. This shows that the heated water rises with natural convection and confirms the effectiveness of the passive heat transfer mechanism in the system as hydrodynamic movement. In the vicinity of the toroidals, it is observed that the temperature gradually decreases from yellow to green and blue. This distribution shows that the heat is spread to the environment and the system is constantly transferring heat. When the flow rate and temperature relationship is evaluated, it is generally observed that the flow rate increases in high temperatures (yellow and orange areas). This shows that the heated water moves faster and thus the heat transfer capacity of the system increases. Complex flow patterns are observed in the region between the two toroidal structures. This shows that the toroidals affect each other's flow and heat transfer properties. This interaction contributes additionally to the overall efficiency of the system. A boundary layer is observed right next to the toroidal, where the flow rate decreases and the temperature increases. This shows the region where heat transfer is most intense. As a result, the complex geometry of the toroidal optimizes fluid motion and heat transfer. The vortices and turbulence that form increase heat transfer, while the natural convection currents ensure passive operation of the system. These findings reveal that the fractal collector design can provide high efficiency in solar water heating applications.

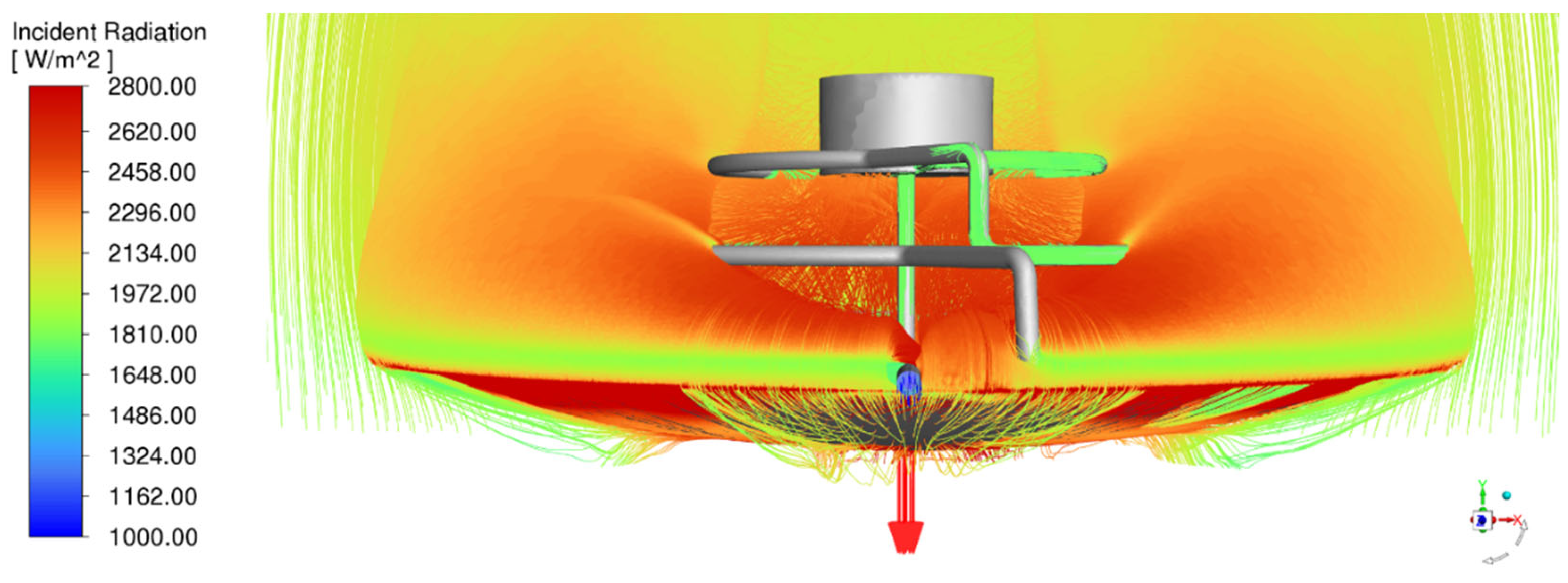

The radiation distribution analysis of the parabolic dish integrated fractal solar collector was performed and the velocity vectors colored according to the incident radiation in the middle plane are given in

Figure 12. The system exhibited a radiation intensity spectrum ranging from 1000 W/m

2 to 2800 W/m

2. The maximum radiation intensity was observed at the focal point of the parabolic dish, and this region was represented by red. It was observed that the fractal collector with a three-layer toroidal structure effectively collected the rays reflected from the dish and the radiation intensity was at medium-high levels represented by yellow and orange colors on the collector surface. The ray paths were shown with green and yellow lines, clearly showing the distribution of radiation within the system. The peripheral radiation levels were shown with colors ranging from green to yellow and were determined to be lower in intensity compared to the center. This analysis proved the effectiveness of the parabolic dish and toroidal collector combination in concentrating and collecting solar rays. It was concluded that the system was designed to optimize the incoming radiation and that the parabolic geometry of the dish effectively focused the beams onto the toroidal collector.

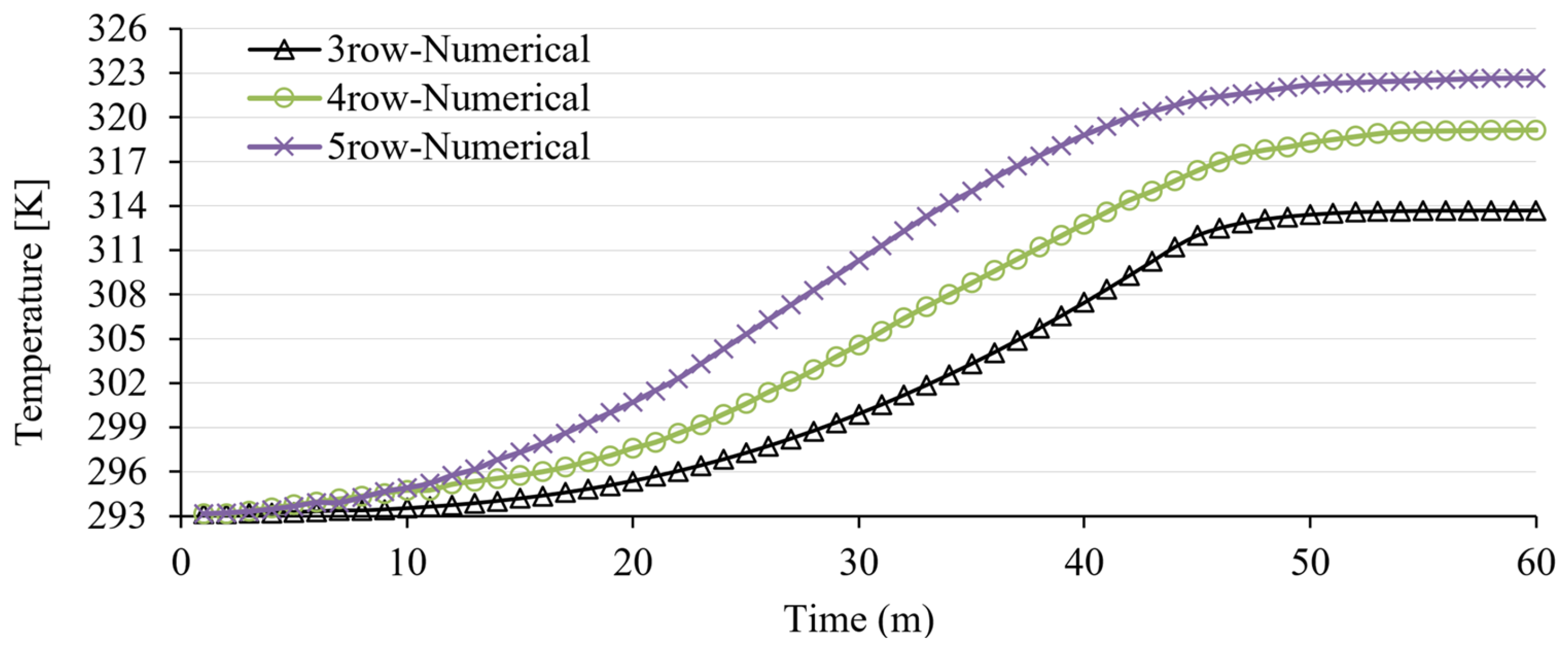

The time-dependent temperature distributions of 3-row, 4-row and 5-row toroidal fractal array solar collectors integrated with parabolic dish are comparatively presented in

Figure 13. In the 3-row structure, it is observed that the parabolic dish starts to concentrate the sun rays in the first 20 minutes and the temperature reaches approximately 314 K at the end of the 60-minute period. However, due to the thermal mass of the system in the 3-row structure, heat transfer is initially slow. Between 20-40 minutes, internal emissivity and diffuse fraction values minimize heat loss and rapidly increase the temperature at the focal point. It is observed that turbulent flows and vortices begin to form between the toroidal structures after 20 minutes, and with the increasing heat transfer rate, the overall temperature of the system reaches thermal stability between 50-60 minutes. In each of these stages, the interaction of the parabolic dish and the fractal structure determines the overall performance of the system. The heat transfer, which is slow at the beginning, accelerates over time and eventually reaches thermal equilibrium. The fact that the 3-row structure reaches a lower maximum temperature compared to other configurations is explained by the fact that it contains less toroidal structure and therefore has less heat transfer surface. In the 4-row structure, the effect of the parabolic dish is seen to start to concentrate the rays in a similar way to the 3-row structure within the first 10 minutes. However, it was observed that the heat transfer started a little faster in the 4-row structure. The reason for this is that, thanks to the additional toroidal structure and the dish, more heat transfer surface is provided, and faster heating is observed in the initial phase compared to the 3-row structure. Between 35-60 minutes, the system approaches thermal equilibrium and reaches a higher temperature (around 319 K) compared to the 3-row structure. This can be explained by the increased heat transfer capacity provided by the additional toroidal structure. In the 5-row structure, the dish operates similarly to other configurations in the first 10 minutes and faster heating is experienced because it provides the largest heat transfer surface. A rapid increase was observed between 10-30 minutes as the increasing turbulent flow and vortices maximized the heat transfer and between 30-60 minutes the system approached thermal equilibrium and reached the highest temperature (around 323 K).

As the number of toroidal structures increases, the heat transfer surface and convection currents become stronger, which increases turbulence and vortices and improves heat transfer. In addition, each additional toroidal structure increases the thermal mass of the system and provides a more homogeneous distribution of heat within the system. Thus, it is seen that the 5-row structure has a more stable and high temperature profile. As a result, it is seen that the heat collection capacity of the system increases with the increase in the number of toroidal row. The 5-row structure provides the highest temperature increase and the fastest heating rate. This analysis shows that the integration of the number of toroidal structures and the parabolic dish in the solar collector design significantly increases the overall performance of the system.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the thermal and hydrodynamic behaviors of 3-row, 4-row and 5-row toroidal fractal solar collectors integrated with a parabolic dish are comprehensively investigated. The study will make significant contributions to the development of innovative solar energy systems by combining theoretical modeling, experimental verification and numerical simulation methods. When the hydrodynamic performance of the proposed system is examined, it is observed that the air flow velocity around the system varies between 0 m/s and 0.73 m/s. It is determined that the complex geometry of the fractal structure increases the heat transfer by creating turbulence and vortices and contributes to the overall efficiency of the system. As a result of the radiation distribution analysis of the parabolic dish integrated fractal solar collector, it is observed that the system exhibits a radiation intensity spectrum varying between 1000-2800 W/m2. The maximum radiation intensity is determined at the focal point of the parabolic dish. It was determined that the fractal collector in the 3-row toroidal structure effectively collected the rays reflected from the dish and that medium-high radiation density (yellow and orange colors) was formed on the collector surface. This analysis revealed that the proposed design (parabolic dish and toroidal collector combination) showed high performance in concentrating and collecting solar rays. In the study, the experimental and numerical analysis data of the 3-row toroidal structure were compared. As a result of the comparison, it was seen that the numerical analysis results converged to the experimental results by 96.84%. The reason why the numerical results were higher than the experimental results is that wind speed, radiative and other thermal losses, etc. were neglected depending on the climatic conditions in which the experiment was conducted. This difference emphasizes the factors affecting the performance of the system in real conditions. In addition, when the thermal and hydrodynamic numerical analysis results of the toroidal structure in the 3-row, 4-row and 5-row fractal array were compared with each other, it was observed that the best performance was obtained in the 5-row structure. When the effect of environmental factors is examined, it is observed that factors such as cold weather conditions in March, seasonal infrared radiation amount and wind speed affect the system performance. These factors are considered among the reasons for the resistance to the temperature increase, especially after the 45th minute of the temperature.

When the proposed system is evaluated within the scope of geometric design, the proposed geometry of the fractal collector optimizes fluid movement and heat transfer. It is observed that each toroidal provides additional thermal energy to the toroidal above it. It is determined that the heat collection capacity of the system increases with the increase in the number of toroidal row and that the 5-row structure provides the highest temperature increase and the fastest heating rate. Within the scope of these results, it is revealed that the fractal solar collector design integrated with a parabolic dish can provide high efficiency in solar water heating applications in terms of system integration and applicability. Experimental and numerical analysis data showed that the novel geometry of the fractal structure increases the heat transfer and hydrodynamic performance of the proposed system by creating turbulence and vortices.

We believe that more work should be done on fractal solar collectors, which allow for more energy collection surfaces to be created in limited areas by scaling in the vertical plane. For example; studies can be conducted on increasing the system performance by using different dish geometries and reflective materials, and studies can be conducted on different fractal geometries and flow directors to further optimize the flow dynamics. In addition, more comprehensive numerical models that include the effects of wind speed, humidity and other environmental factors can be developed. It is recommended that long-term field tests should be conducted to evaluate the performance of the system in different climatic conditions and throughout the year.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and N.R.; methodology, A.K. N.R. and N.G.; software, G.A.K.; validation, N.G., G.A.K, N.R and A.K.; formal analysis, N.G. ; investigation, A.K.; resources, A.K. and N.R.; data curation, A.K.; writing—N.G and G.A.K., X.X.; writing—N.G., A.K.; visualization, G.A.K. and N.G.; supervision, A.K. and N.G.; project administration, A.K. and N.R.; funding acquisition, A.K. and N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maka, A. O. and Alabid, J. M. Solar energy technology and its roles in sustainable development. Clean Energy, 2022, 6(3), 476-483. [CrossRef]

- Haji, D., and Genc, N. Dynamic behaviour analysis of ANFIS based MPPT controller for standalone photovoltaic systems. International journal of renewable energy research, 2020, 10(1), 101-108.

- Kumar, K. R., Chaitanya, N. K., Kumar, N. S. Solar thermal energy technologies and its applications for process heating and power generation–A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, 282, 125296. [CrossRef]

- Borzuei, D., Moosavian, S. F., Ahmadi, A., Ahmadi, R., Bagherzadeh, K. An experimental and analytical study of influential parameters of parabolic trough solar collector. Journal of Renewable Energy and Environment, 2021, 8(4), 52-66. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, M., Li, J., Wang, H., Zhao, Y. Improving thermal energy storage and transfer performance in solar energy storage: Nanocomposite synthesized by dispersing nano boron nitride in solar salt. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 2021, 232, 111378. [CrossRef]

- El-Sebaey, M. S., Mousavi, S. M., Sathyamurthy, R., Panchal, H., Essa, F. A. A detailed review of various design and operating parameters affecting the thermal performance augmentation of flat-plate solar collectors. International Journal of Ambient Energy, 2024, 45(1), 2351100. [CrossRef]

- Goel, A., & Manik, G. Solar thermal system—an insight into parabolic trough solar collector and its modeling. In Renewable Energy Systems, 1st ed.; Ahmad, T.A., Nashwa, A.K., Academic Press: 2021; pp. 309-337. [CrossRef]

- Kaneesamkandi, Z., and Sayeed, A. Performance of Solar Hybrid Cooling Operated by Solar Compound Parabolic Collectors under Weather Conditions in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(12), 7343. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J., Kim, Y. J., Shin, H. S., Kim, K. J., Shin, B. H., Lee, S. W., Kim B.W., Kim, W. C. Optical Module for Simultaneous Crop Cultivation and Solar Energy Generation: Design, Analysis, and Experimental Validation. Applied Sciences, 2024, 14(11), 4758. [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E. and Tzivanidis, C. Alternative designs of parabolic trough solar collectors. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 2019, 71, 81-117. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, G., Di Nicola, G., Colla, L., Fedele, L., Scattolini, M. Adoption of nanofluids in low-enthalpy parabolic trough solar collectors: Numerical simulation of the yearly yield. Energy Conversion and Management, 2016, 118, 306-319. [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, E. H., Emran, M., Elsamni, O., Rashad, M., Mokhiamar, O. Parabolic dish collector as a new approach for biochar production: an evaluation study. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(24), 12677. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J. H., Wang, J., Lund, P. D., Zhao, D. D., Xu, J. W., Jin, Y. H. Comparative study of heat transfer enhancement using different fins in semi-circular absorber tube for large-aperture trough solar concentrator. Renewable Energy, 2021, 169, 1229-1241. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Abed, A. M., Beemkumar, N., Kumar, A. V., Ayed, H., Mouldi, A., Shamel, A. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic analysis of application of hybrid nanofluid in a parabolic solar trough collector. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 2024, 160(19), 194701. [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T., and Boukraa, M. Thermal efficiency enhancement of parabolic trough collectors: a review. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2022, 147(20), 10923-10942. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M., Padhi, B. N., Mishra, I. Numerical simulation of solar parabolic trough collector with arc-plug insertion. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 2021, 43(21), 2635-2655. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y., Xu, Y., Li, Q., Wang, J., Wang, Q., Liu, B. Efficiency enhancement of a solar trough collector by combining solar and hot mirrors. Applied Energy, 2021, 299, 117290. [CrossRef]

- Panduro, E. A. C., Finotti, F., Largiller, G., Lervåg, K. Y. A review of the use of nanofluids as heat-transfer fluids in parabolic-through collectors. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2022, 211, 118346. [CrossRef]

- Del Aghenese, A. P., Naldi, C., Rocha, L. A. O., Isoldi, L. A., Prolo Filho, J. F., Biserni, C., dos Santos, E. D. Geometrical investigation of forced convective flows over staggered arrangement of cylinders employing constructal design. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 2024, 155, 107553. [CrossRef]

- Rafat, E., Babaelahi, M., and Arabkoohsar, A. Design and analysis of a hybrid solar power plant for co-production of electricity and water: a case study in Iran. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2022, 147, 1469-1486. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Z., Shaikh, P. H., Zhang, S., Lashari, A. A., Leghari, Z. H., Baloch, M. H., ... & Caiming, C. A review on design parameters and specifications of parabolic solar dish Stirling systems and their applications. Energy Reports, 2022, 8, 4128-4154. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Li, J., Chen, Y. Improving the energy discharging performance of a latent heat storage (LHS) unit using fractal-tree-shaped fins. Applied Energy, 2020, 259, 114102. [CrossRef]

- Dannelley, D., and Baker, J. Radiant fin performance using fractal-like geometries. Journal of heat transfer, 2013, 135(8), 081902. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C. K., Christian, J. M., Yellowhair, J., Ortega, J., Andraka, C. Fractal-like receiver geometries and features for increased light trapping and thermal efficiency. In AIP Conference Proceedings, May-2016, (Vol. 1734, No. 1). AIP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Budanov, P., Kyrysov, I., Brovko, K., Rudenko, D., Vasiuchenko, P., Nosyk, A. Development of a solar element model using the method of fractal geometry theory. Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, 2021, 3(8), 111. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Jiang, J., Hong, Y., Du, J. Numerical investigation of thermal management performances in a solar photovoltaic system by using the phase change material coupled with bifurcated fractal fins. Journal of Energy Storage, 2022, 56, 106156. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C. K., Christian, J. M., Ortega, J. D., Yellowhair, J., Mosquera, M. J., Andraka, C. E. Reduction of radiative heat losses for solar thermal receivers. In High and Low Concentrator Systems for Solar Energy Applications, 2014, IX (vol. 9175, pp. 19-28). SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, A., Enayati, M., Beigi, N., Ahmadi, A., Pourmohamadian, H., Sadeghi, S., ... & Golzar, A. Comparison of the effect of using helical strips and fines on the efficiency and thermal–hydraulic performance of parabolic solar collectors. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 2022, 52, 102254. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B., Yang, Y., Chen, L. Developing a novel form of thermal conductivity of nanofluids with Brownian motion effect by means of fractal geometry. Powder Technology, 2013, 239, 409-414. [CrossRef]

- Kant, K., Sibin, K. P., Pitchumani, R. Novel fractal-textured solar absorber surfaces for concentrated solar power. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 2022, 248, 112010. [CrossRef]

- Arasu, A. V., and Sornakumar, T. Design, manufacture and testing of fiberglass reinforced parabola trough for parabolic trough solar collectors. Solar Energy, 2007, 81(10), 1273-1279. [CrossRef]

- Solak, E. K., and Irmak, E. Advances in organic photovoltaic cells: A comprehensive review of materials, technologies, and performance. RSC advances, 2023, 13(18), 12244-12269. [CrossRef]

- Tian, M., Su, Y., Zheng, H., Pei, G., Li, G., and Riffat, S. A review on the recent research progress in the compound parabolic concentrator (CPC) for solar energy applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2018, 82, 1272-1296. [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, A., Babar, H., Ali, H. M., Jamil, F., Janjua, M. M., Fattah, I. R., ... & Li, C. Concentrated photovoltaics as light harvesters: Outlook, recent progress, and challenges. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 2021, 46, 101199. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Zhang, Z., Wang, L., Zhang, Z., Wei, J. Comprehensive review of line-focus concentrating solar thermal technologies: parabolic trough collector (PTC) vs linear Fresnel reflector (LFR). Journal of Thermal Science, 2020, 29, 1097-1124. [CrossRef]

- Bayareh, M., and Usefian, A. Simulation of parabolic trough solar collectors using various discretization approaches: A review. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, 2023, 153, 126-137. [CrossRef]

- Merchán, R. P., Santos, M. J., Medina, A., Hernández, A. C. High temperature central tower plants for concentrated solar power: 2021 overview. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2022, 155, 111828. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F., Ji, J., Cai, J. and Yu, B. Experimental and numerical study of the freezing process of flat-plate solar collector. Applied thermal engineering, 2017, 118, 773-784. [CrossRef]

- Murugan, M., Saravanan, A., Elumalai, P. V., Kumar, P., Saleel, C. A., Samuel, O. D., ... & Afzal, A. An overview on energy and exergy analysis of solar thermal collectors with passive performance enhancers. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2022, 61(10), 8123-8147. [CrossRef]

- Rustamov, N., Kibishov, Genc, N., A., Babakhan, S., and Kamal, E. Thermal Conductivity of a Vacuum Fractal Solar Collector. International Journal of Renewable Energy Research (IJRER), 2023, 13(2), 612-618. [CrossRef]

- Msomi, V. and Nemraoui, O. Improvement of the performance of solar water heaters based on nanotechnology. In 2017 IEEE 6th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Nov-2017, (pp. 524-527).

- Incropera, F.P., DeWitt, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 5th ed., Wiley, 2002, p. 917.

- ANSYS Inc., ANSYS FLUENT User’s Guide (2003) Fluent, Netherland, Lebanon, ANSYS Press.

- Coelho, P. J. Advances in the discrete ordinates and finite volume methods for the computation of radiative heat transfer in non-gray absorbing, emitting, and anisotropically scattering media. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, 2014, 113(8), 637-657. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).