Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

26 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

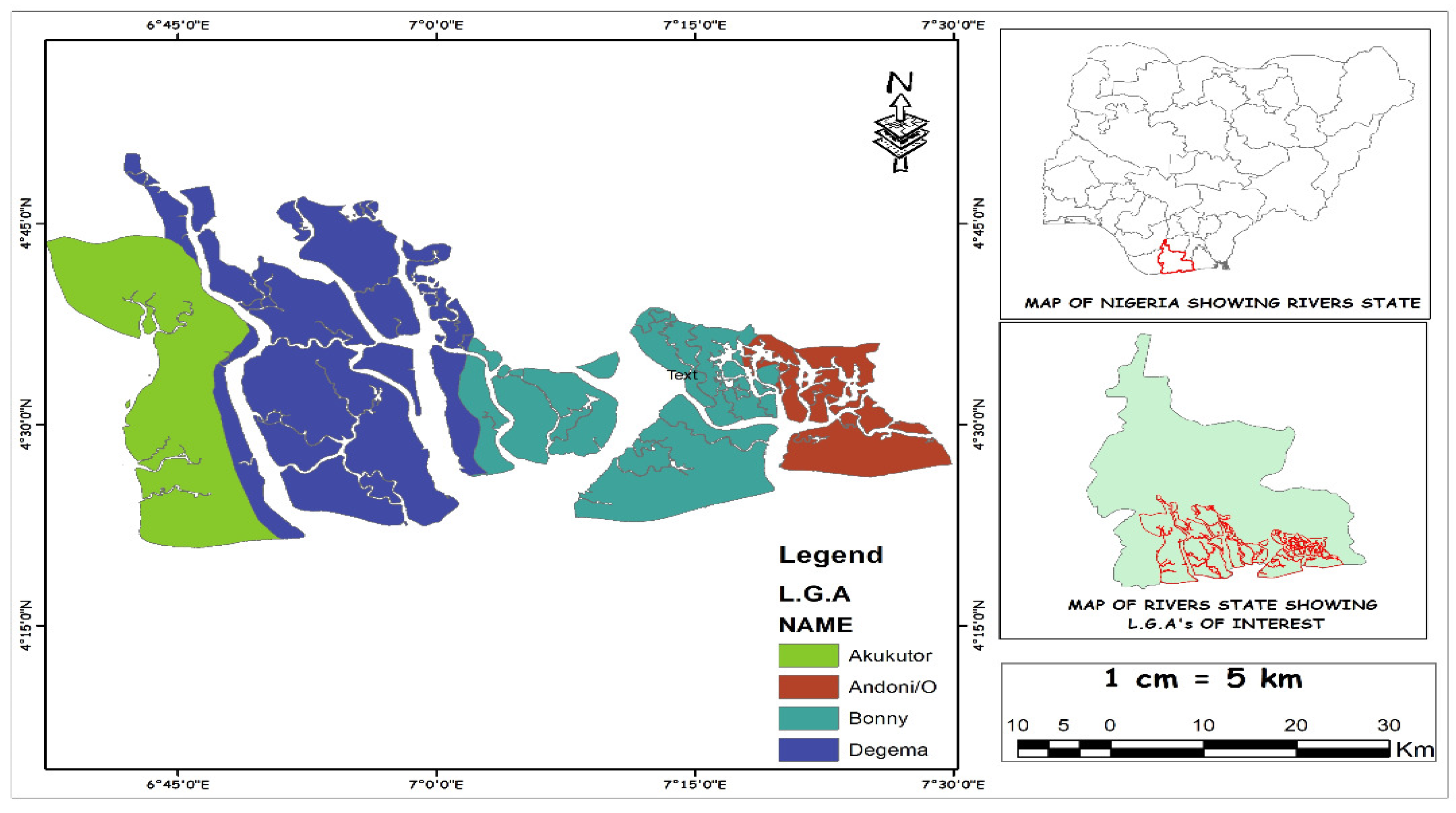

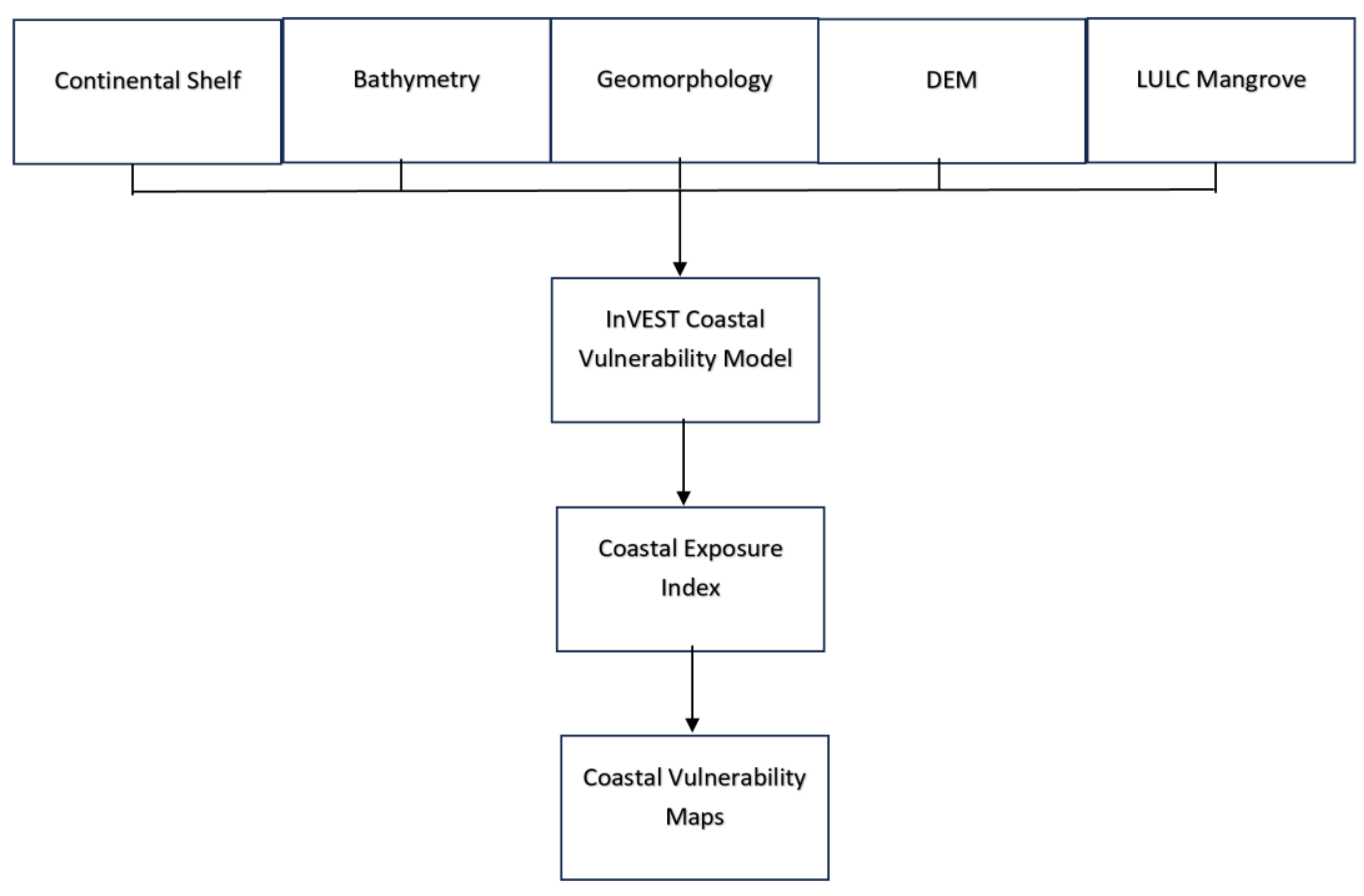

2. Materials and Methods

Coastal Exposure

Coastal Exposure Index

3. Results

3.1. Exposure with Current Habitat Conditions

3.2. Exposure with Habitat Scenario

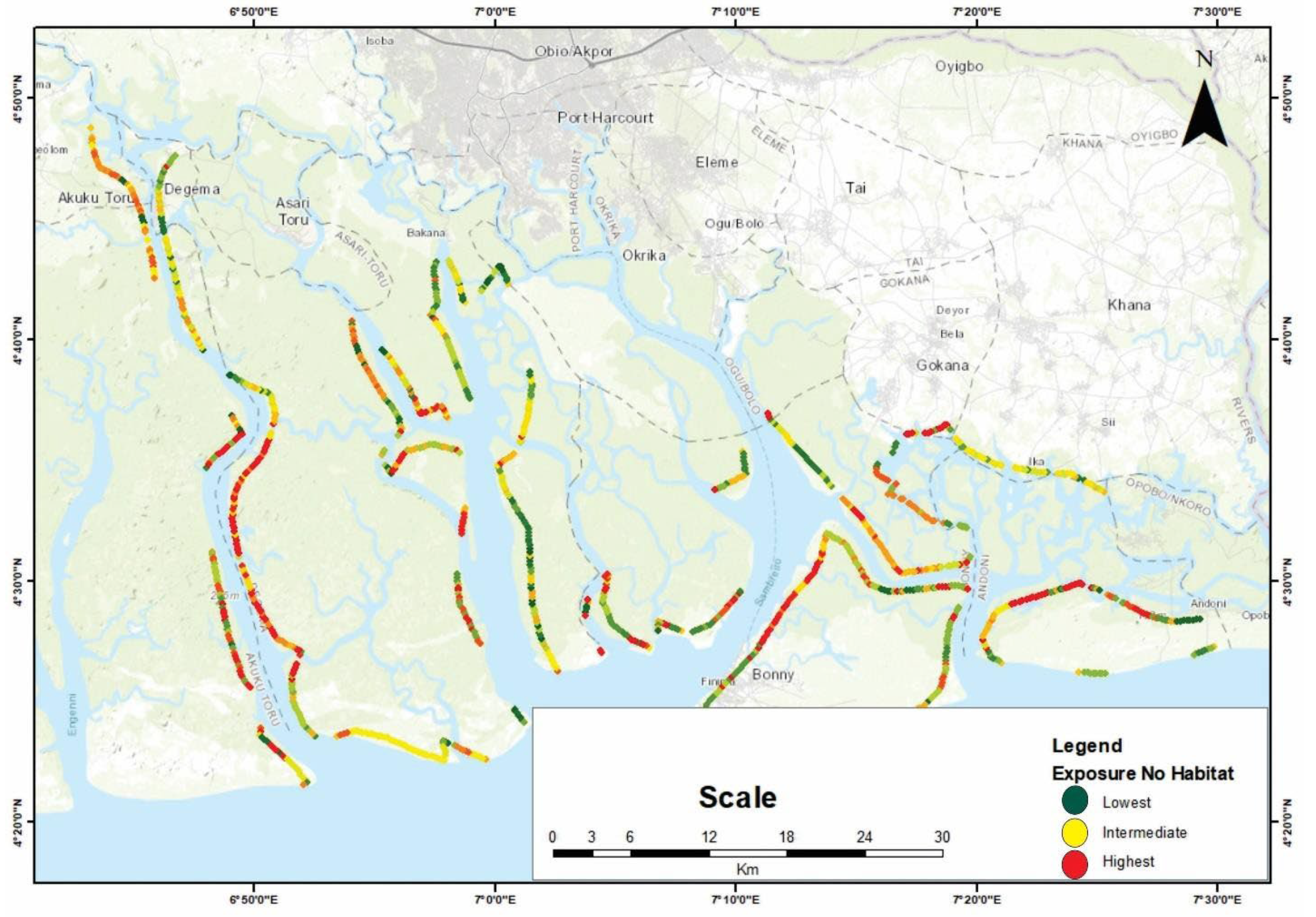

3.3. Exposure without Habitat Scenario

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- [1] Adopted IPCC, (2014). Climate change 2014 synthesis report. IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1059- 1072.

- [2] Ai, B., Tian, Y., Wang, P., Gan, Y., Luo, F., & Shi, Q., (2022). Vulnerability Analysis of Coastal Zone Based on InVEST Model in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Sustainability, 14(11), 6913. [CrossRef]

- [3] Arkema, K.K., Guannel, G., Verutes, G., Wood, S.A., Guerry, A., Ruckelshaus, M., & Silver, J.M., (2013). Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nature climate change, 3(10), 913-918.

- [4] Artmann, M., & Breuste, J., (2015). Cities built for and by residents: Soil sealing management in the eyes of urban dwellers in Germany. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 141(3), A5014004.

- [5] Assessment, M.E., (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends.

- [6] Balian, E., Eggermont, H., & Le, Roux, X., (2014). Outputs of the strategic foresight workshop ‘‘nature-based solutions in a BiodivERsA context’’. In Brussels: BiodivERsA Workshop Report.

- [7] Bauduceau, N., Berry, P., Cecchi, C., Elmqvist, T., Fernandez, M., Hartig, T., & Tack, J., (2015). Towards an EU research and innovation policy agenda for nature-based solutions & re-naturing cities: Final report of the horizon 2020 expert group on nature-based solutions and re-naturing cities.

- [8] Bayani, N., & Barthélemy, Y., (2016). Integrating ecosystems in risk assessments: Lessons from applying InVEST models in data-deficient countries. Ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction and adaptation in practice, 227-254.

- [9] Beck, M., Gilmer, B., Ferdana, Z., Raber, G.T., Shepard, C., Meliane, I, & Newkirk, S., (2013). Increasing the resilience of human and natural communities to coastal hazards: supporting decisions in New York and Connecticut. The role of ecosystems in disaster risk reduction, 140-163.

- [10] CBD, (2019). Voluntary guidelines for the design and effective implementation of EbA to climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction and supplementary information. In: CBD Technical Series No.93 Secretariat the Convention on Biological Diversity(93). https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-93-en.pdf.

- [11] Cohen-Shacham, E., Walters, G., Janzen, C., & Maginnis, S. (2016). Nature-based solutions to address global societal challenges. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 97, 2016-2036.

- [12] Daily, G.C,, Kareiva, P.M., Polasky, S., Ricketts, T.H., & Tallis, H. (2011). Mainstreaming natural capital into decisions. In: Kareiva P, Tallis, H., Ricketts, T.H., Daily, G.C., Polasky, S., (eds). Natural capital: theory and practice of mapping ecosystem services. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Kindle Edition.[13] DeFries, R., Pagiola, S., Adamowicz, W.L., Akcakaya, H.R., Arcenas, A., Babu, S., ... & Thönell, J., (2005). Analytical approaches for assessing ecosystem condition and human well-being. Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends, 1, 37-71.[1][1]9.

- [14] Desa, UN. World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision. United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs. Population Division: New York, NY, USA. 2015;41.

- [15] Durotoye, A., 2000. "The Nigerian State at a Critical Juncture: The Dilemma of a Confused Agenda". University of Leipzig Paper on Africa, Politics and Economic Series (38):1-28.

- [16] EME, [Evaluacio´n de los Ecosistemas del Milenio de Espa~na] (2011) Sı´ntesis de resultados. Fundacio´n Biodiversidad. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino. Madrid: Spain.

- [17] Estrella, M., Renaud, F.G., & Sudmeier-Rieux, K., (2013). Opportunities, challenges, and future perspectives for ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction.

- [18] European Commission, (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy. Official Journal of the European Communities L 327: 1–72.

- [19] European Environment Agency, (2012). Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2012: an indicator-based report. Office for Official Publ. of the Europ. Union.

- [20] European Union, (2014). Mapping and assessment of ecosystems and their services: indicators for ecosystem assessments under Action 5 of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. 2nd Report. February 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/knowledge/ecosystem_assessment/pdf/2ndMAESWorkingPaper.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2015.

- [21] Fadairo, O., Olajuyigbe, S., & Adelakun, O., (2023). Drivers of vulnerability to climate change and adaptive responses of forest-edge farming households in major agro-ecological zones of Nigeria. GeoJournal 88, 2153–2170 (2023). [CrossRef]

- [22] FAO, 1997. Management and Utilization of the Mangroves in Asia and the Pacific. FAO. Rome, pp: 319.

- [23] GFDRR, [Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery] (2014). Review of open source and open access software packages available to quantify risk from natural hazards. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- [24] Goddard, M.A., Dougill, A.J., & Benton, T.G., (2010). Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(2):90-98. [CrossRef]

- [25] Gornitz, V., (1990). Vulnerability of the East Coast, USA to future sea level rise. Journal of Coastal research, 201-237.

- [26] Guannel, G., Ruggiero, P., Faries, J., Arkema, K., Pinsky, M., Gelfenbaum, G., & Kim, C.K., (2015). Integrated modeling framework to quantify the coastal protection services supplied by vegetation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(1), 324-345.

- [27] Guerry, A.D., Ruckelshaus, M.H., Arkema, K.K., Bernhardt, J.R., Guannel, G., Kim, C.K, & Spencer, J., (2012). Modeling benefits from nature: using ecosystem services to inform coastal and marine spatial planning. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 8(1-2), 107-121.

- [28] Hammar-Klose, E.S., & Thieler, E.R., (2001). Coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise: a preliminary database for the US Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf of Mexico coasts (No. 68). US Geological Survey.

- [29] Harley, C.D., Randall, Hughes, A., Hultgren, K.M., Miner, B.G., Sorte, C.J., Thornber, C.S., & Williams, S.L., (2006). The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecology letters, 9(2), 228-241.

- [30] Kabisch, N., Frantzeskaki, N., Pauleit, S., Naumann, S., Davis, M., Artmann, M., & Bonn, A., (2016a). Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecology and society, 21(2).

- [31] Kabisch, N., Frantzeskaki, N., Pauleit, S., Naumann, S., Davis, M., Artmann, M., & Bonn, A., (2016b). Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecology and society, 21(2).

- [32] Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., & Bonn, A., (2017). Nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation in urban areas: Linkages between science, policy, and practice. Springer Nature.

- [33] Kamalu, O.J., & Wokocha, C.C., (2011). Land resource inventory and ecological vulnerability: Assessment of Onne area in Rivers State, Nigeria. Research journal of environmental and earth sciences, 3(5), 438-447.

- [34] Langridge, S.M., Hartge, E.H., Clark, R., Arkema, K., Verutes, G.M., Prahler, E.E., ... & O'Connor, K., (2014). Key lessons for incorporating natural infrastructure into regional climate adaptation planning. Ocean Coastal Management, 95, 189-197.

- [35] McKenzie, E., Irwin, F., Ranganathan, J., Hanson, C., Kousky, C., Bennett, K., ... & Paavola, J., (2011). Incorporating ecosystem services in decisions. Natural capital: theory and practice of mapping ecosystem services. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 339-355.

- [36] Mmom, P.C., & Arokoyu, S.B., (2010). Mangrove Forest depletion, biodiversity loss and traditional resources management practices in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 2(1), 28-34.

- [37] Mooney, P.F., (2011). The effect of human disturbance on site habitat diversity and avifauna community composition in suburban conservation areas. Ecosystems and Sustainable Development, 13- 26.

- [38] United Nations, (2014). World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision, highlights. department of economic and social affairs. Population Division, United Nations, 32.

- [39] Natural Capital Project, (2014). InVEST coastal vulnerability model 3.0.0 documentation http://www.naturalcapitalproject.org/models/coastal_vulnerability.html.

- [40] Ologunorisa, T.E., (2004). An assessment of flood vulnerability zones in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. International journal of environmental studies, 61(1), 31-38.

- [41] Oloyede, M.O., Williams, A.B., Ode, G.O., & Benson, N. U., (2022). Coastal vulnerability assessment: A case study of the Nigerian coastline. Sustainability, 14(4), 2097.

- [42] Omo-Irabor, O, Olobaniyi, S.B. Akunna, J., Venus, V., Maina, J.M., & Paradzayi, C., (2011). Mangrove vulnerability modelling in parts of Western Niger Delta, Nigeria using satellite images, GIS techniques and Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis (SMCA). Environmental monitoring and assessment, 178(1-4), 39- 33.

- [43] Peduzzi, P., Velegrakis, A., Estrella, M. & Chatenoux, B. (2013). Integrating the role of ecosystems in disaster risk and vulnerability assessments: Lessons from the Risk and Vulnerability Assessment Methodology Development Project (RiVAMP) in Negril, Jamaica. The role of ecosystems in disaster risk reduction, 109-139.

- [44] PLOS ONE Staff, (2015). Correction: future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding-a global assessment. PloS one, 10(6), e0131375.

- [45] Savo, V., Lepofsky, D., Benner, J.P., Kohfeld, K.E., Bailey, J., & Lertzman, K., (2016). Observations of climate change among subsistence-oriented communities around the world. Nature Climate Change, 6(5), 462-473.

- [46] Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, (CBD) (2019). Voluntary Guidelines for the Design and Effective Implementation of Ecosystem-based Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster risk Reduction and Supplementary Information. CBD Technical Series No. 93.

- [47] Seddon, N., Smith, A., Smith, P., Key, I., Chausson, A., Girardin, C. & Turner, B., (2021). Getting the message right on nature- based solutions to climate change. Global change biology, 27(8), 1518-1546.

- [48] Seto, K. C., Fragkias, M., Güneralp, B., & Reilly, M. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of global urban land expansion. PloS one, 6(8), e23777.

- [49] Shah, M.A.R., Renaud, F.G., Anderson, C.C., Wild, A., Domeneghetti, A., Polderman, A, & Zixuan, W., (2020). A review of hydro-meteorological hazard, vulnerability, and risk assessment frameworks and indicators in the context of nature-based solutions. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 50, 101728.

- [50] Silver, J.M., Arkema, K.K., Griffin, R.M., Lashley, B., Lemay, M., Maldonado, S., Moultrie, S.H., Ruckelshaus, M., Schill, S., Thomas, A., Wyatt, K., & Verutes, G., (2019). Advancing Coastal Risk Reduction Science and Implementation by Accounting for Climate, Ecosystems, and People. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 556. [CrossRef]

- [51] Silver, J.M., Arkema, K.K., Griffin, R.M., Lashley, B., Lemay, M., Maldonado, S., Moultrie, S.H., Ruckelshaus, M., Schill, S., Thomas, A., Wyatt, K., & Verutes. G., (2019). Advancing Coastal Risk Reduction Science and Implementation by Accounting for Climate, Ecosystems, and People. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 556. [CrossRef]

- [52] Singh, S., & Singh, J.S., (1995). Microbial biomass associated with water-stable aggregates in forest, savanna and cropland soils of a seasonally dry tropical region, India. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 27(8), 1027-1033.

- [53] Sutton-Grier, A.E. & Sandifer, P.A., (2019). Conservation of wetlands and other coastal ecosystems: a commentary on their value to protect biodiversity, reduce disaster impacts, and promote human health and well-being. Wetlands, 39(6), 1295-1302.

- [54] Tallis, H.T., Ricketts, T., Guerry, A.D., Nelson, E., Ennaanay, D., Wolny, S., ... & Sharp, R., (2011). InVEST 2.1 beta user’s guide. Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs.

- [55] Thieler, E.R., Hammar-Klose, S., (1999). National assessment of coastal vulnerability to future sea-level rise: preliminary results for the US Atlantic Coast [Internet]. US Geological Survey. Open-File Report. Available from: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/of99-593/.

- [56] Thomas, A.S., Mangubhai, S., Vandervord, C., Fox, M., & Nand, Y., (2018). Impact of tropical cyclone Winston on women mud crab fishers in Fiji. Climate and Development 11, 699–709. doi:10.1080/17565529. 2018.1547677.

- [57] Turner, I.L., Harley, M.D., & Drummond, C.D., (2016). UAVs for coastal surveying. Coastal Engineering, 114, 19-24.

- [58] UNFCCC, (2011). National Adaptation Programmes of Action. (http://unfccc.int/national_reports/napa/items/2719.php. [20 January 2014]).

- [59] UNISDR, C., (2015). The human cost of natural disasters 2015: A global perspective Umechuruba, C.I. (2005). Health impact assessment of mangrove vegetation in an oil spilled site at the Bodo West field in Rivers State, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 9(1), 69-73. Agency for International Development.

- [60] Watson, R., Albon, S., Aspinall, R., Austen, M, Bardgett, B, Bateman, I., ... & Winter, M., (2011). UK National Ecosystem Assessment: understanding nature's value to society. Synthesis of key findings.

- [61] Yang, M.G.M., Hong, P., & Modi, S.B., (2011). Impact of lean manufacturing and environmental management on business performance: An empirical study of manufacturing firms. International Journal of production economics, 129(2), 251-261.

| Model inputs | Year | Extent | Resolution (m) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Natural habitats (LULC Mangroves accessed in 2020) |

2020 | Rivers State | 30 | http://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/lulc-global-mangrove-forests-distribution-2000 |

|

Digital Elevation Model (DEM) |

2022 | Global | 30 | (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) |

| Wind/ Wave data | 2005-2010 | Global | - | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

|

Coastal Geomorphology (Shoreline type) |

2022 | Rivers State | 30 | NGSA (Nigeria Geological Survey Agency) |

|

Global land mass polygon shapefile |

2016 | Global | 30 | Made with Natural Earth. Free vector and raster map data @ naturalearthdata.com (Wessel and Smith, 1996) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).