Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

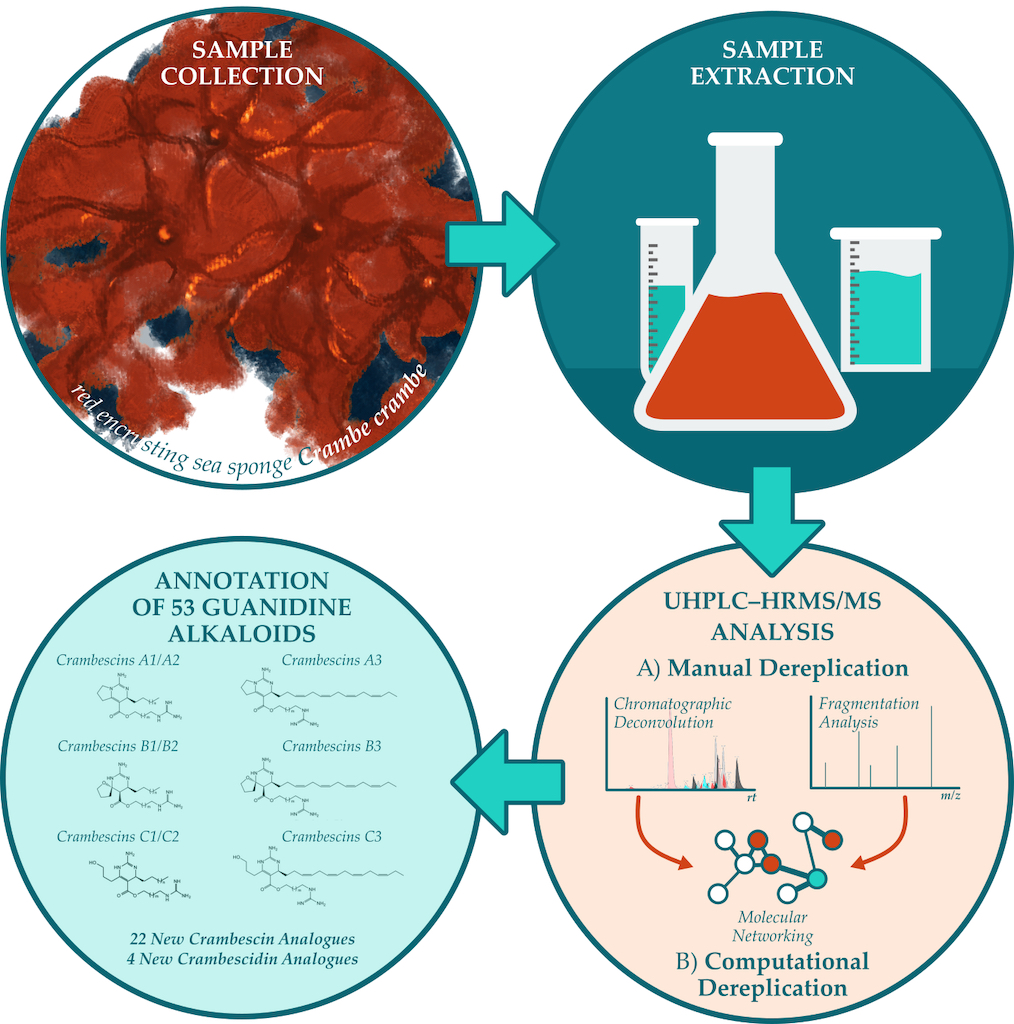

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

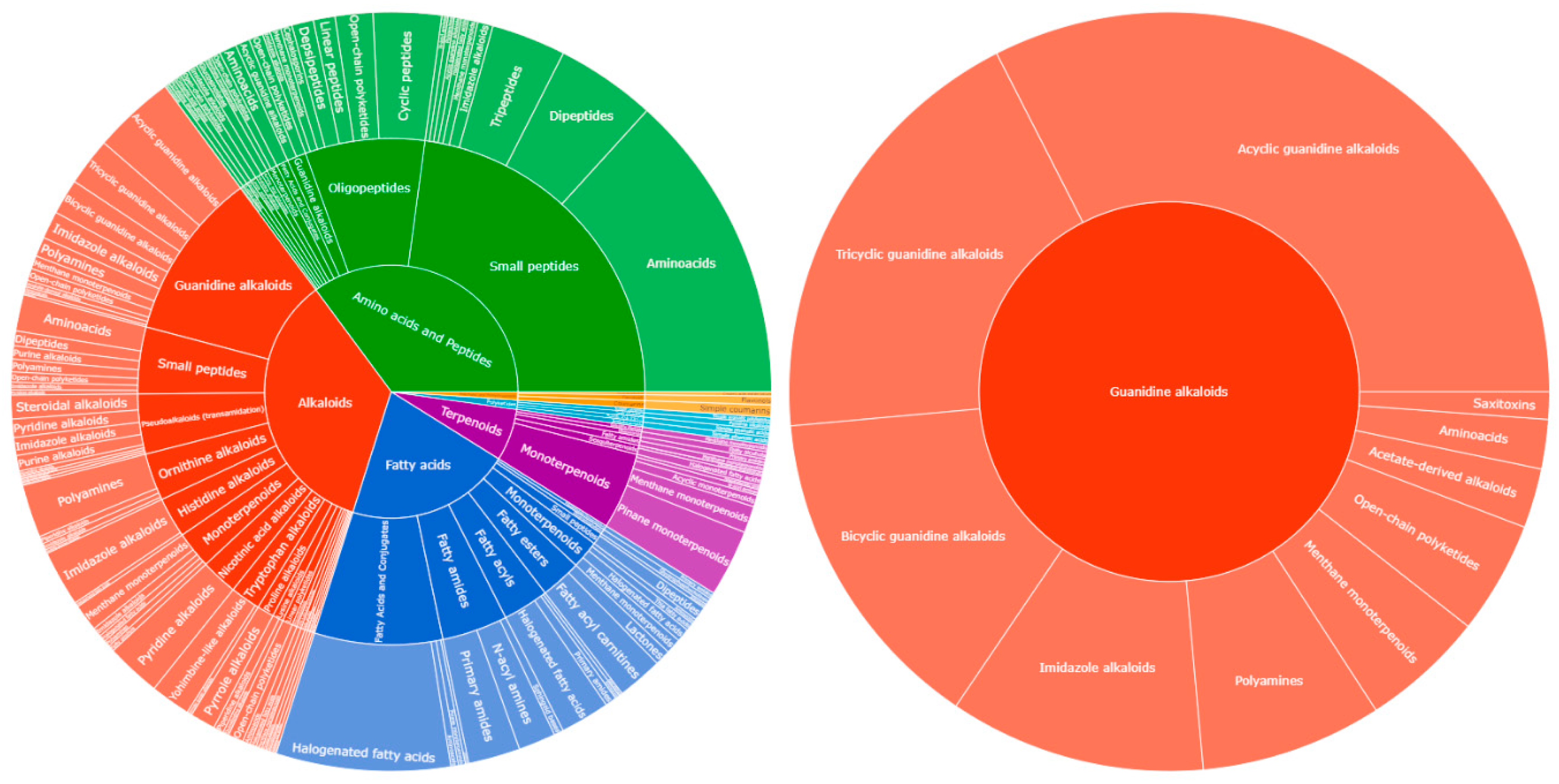

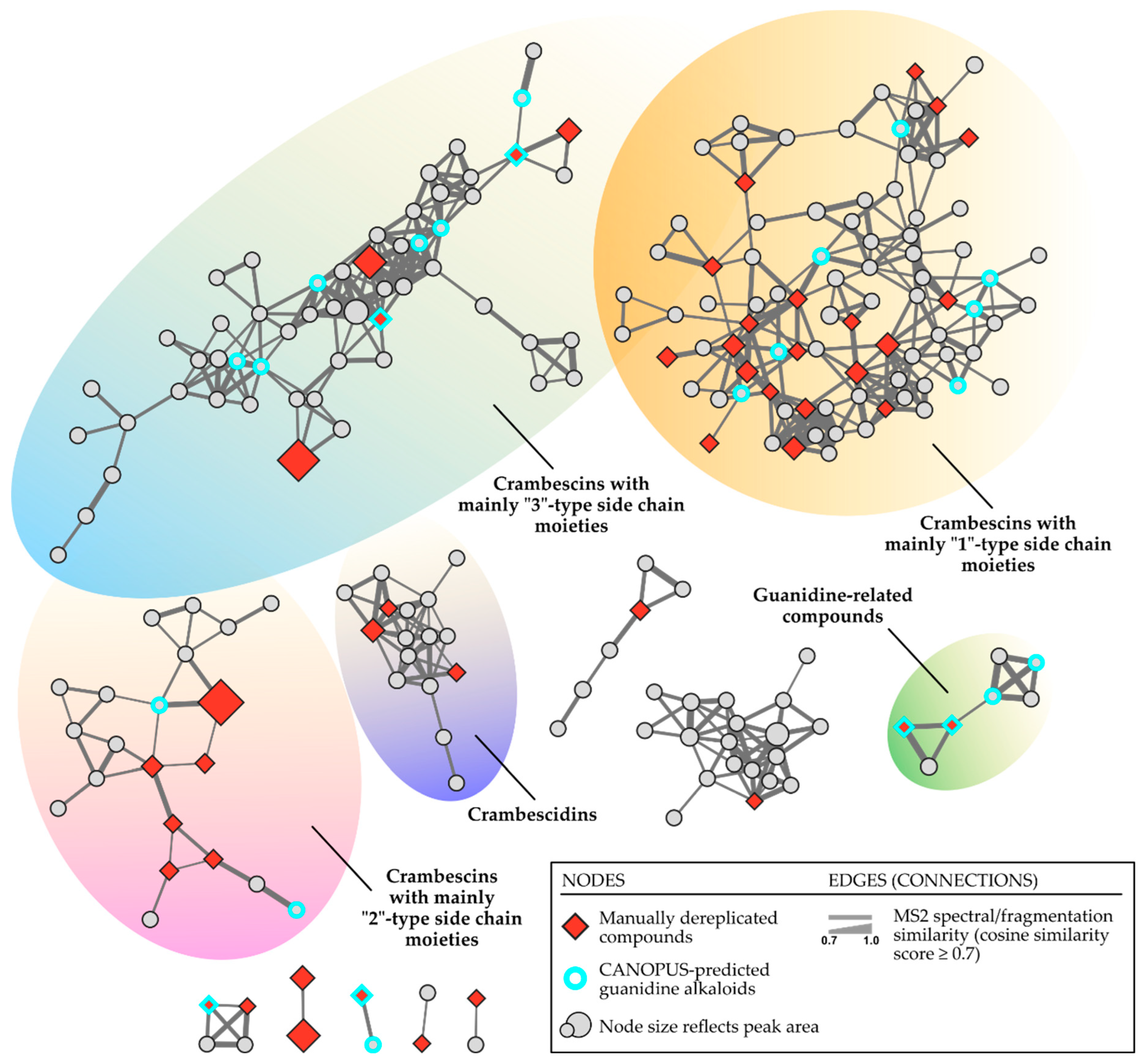

2. Results and Discussion

| # | m/z | Rt | Charge state, z |

Mw exp.a | Proposed Formula |

Δ(ppm)b | Major MS/MS fragments: m/z (charge state, z) | Proposed Identification |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 282.1806 | 8.16 | 1 | 281.1728 | C14H23N3O3 | -2.28 | 246.1587 (1); 264.1706 (1); 114.9612 (1); 60.0562 (1) | guanidine related compound (C14H23N3O3) |

|

| 2 | 282.1806 | 9.34 | 1 | 281.1728 | C14H23N3O3 | -2.13 | 114.9611 (1); 60.0562 (1); 223.1323 (1) | guanidine related compound (C14H23N3O3) |

|

| 3 | 264.1704 | 9.66 | 1 | 263.1626 | C14H21N3O2 | -0.99 | 246.1604 (1); 60.0562 (1) | guanidine related compound (C14H21N3O2) |

|

| IS | 355.2012 | 9.80 | 1 | 354.1934 | C21H26N2O3 | -0.75 | 144.0807 (1); 212.1274 (1) | Yohimbine | |

| 4 | 296.1964 | 10.44 | 1 | 295.1886 | C15H25N3O3 | -1.52 | 237.1476 (1); 205.1217 (1); 60.0562 (1); 159.1160 (1) | guanidine related compound (C15H25N3O3) |

|

| 5 | 227.1803 | 10.46 | 2 | 452.3450 | C23H44N6O3 | -3.31 | 174.1600 (1); 148.6021 (2) | crambescin C 452 homologue (m=5, n=4) |

|

| 6 | 234.1884 | 10.77 | 2 | 466.3612 | C24H46N6O3 | -1.93 | 188.1756 (1); 155.6100 (2) | crambescin C 466 homologue (m=6, n=4) |

|

| 7 | 174.1600 (1); 148.6021 (2) | crambescin C 466 homologue (m=5, n=5) |

|||||||

| 8 | 218.1757 | 10.87 | 2 | 434.3357 | C23H42N6O2 | -0.65 | 197.1646 (2); 174.1600 (1); 148.1095 (2); 220.1689 (1) | crambescin A 434 homologue (m=5, n=4) |

|

| 9 | 227.1803 | 10.88 | 2 | 452.3450 | C23H44N6O3 | -3.32 | 128.1431 (1); 174.1599 (1); 111.0442 (1); 284.1956 (1) | crambescin B 452 homologue (m=5, n=4) |

|

| 10 | 234.1884 | 10.98 | 2 | 466.3612 | C24H46N6O3 | -1.91 | 160.1441 (1); 141.5942 (2) | crambescin C1 466 (m=4, n=6) | [11] |

| 11 | 241.1961 | 11.14 | 2 | 480.3765 | C25H48N6O3 | -2.42 | 188.1756 (1); 155.6096 (2) | crambescin C 480 homologue (m=6, n=5) |

|

| 12 | 225.1835 | 11.16 | 2 | 448.3514 | C24H44N6O2 | -0.45 | 204.1722 (2); 188.1756 (1); 155.1178 (2); 220.1689 (1) | crambescin A 448 homologue (m=6, n=4) |

|

| 13 | 292.8887 | 11.18 | 3 | 875.6426 | C44H87N6O11 | 1.73 | 246.1587 (1); 139.0751 (1); 162.1598 (1); 381.3460 (1) | crambescidin 875 | |

| 14 | 234.1884 | 11.18 | 2 | 466.3612 | C24H46N6O3 | -1.93 | 128.1432 (1); 111.0443 (1); 188.1757 (1); 298.2129 (1) | crambescin B 466 homologue (m=6, n=4) |

|

| 15 | 279.2133 | 11.19 | 3 | 834.6166 | C45H82N6O8 | -1.01 | 246.1586 (1); 264.1707 (1); 70.0657 (1); 139.0750 (1) d | crambescidin 834 | |

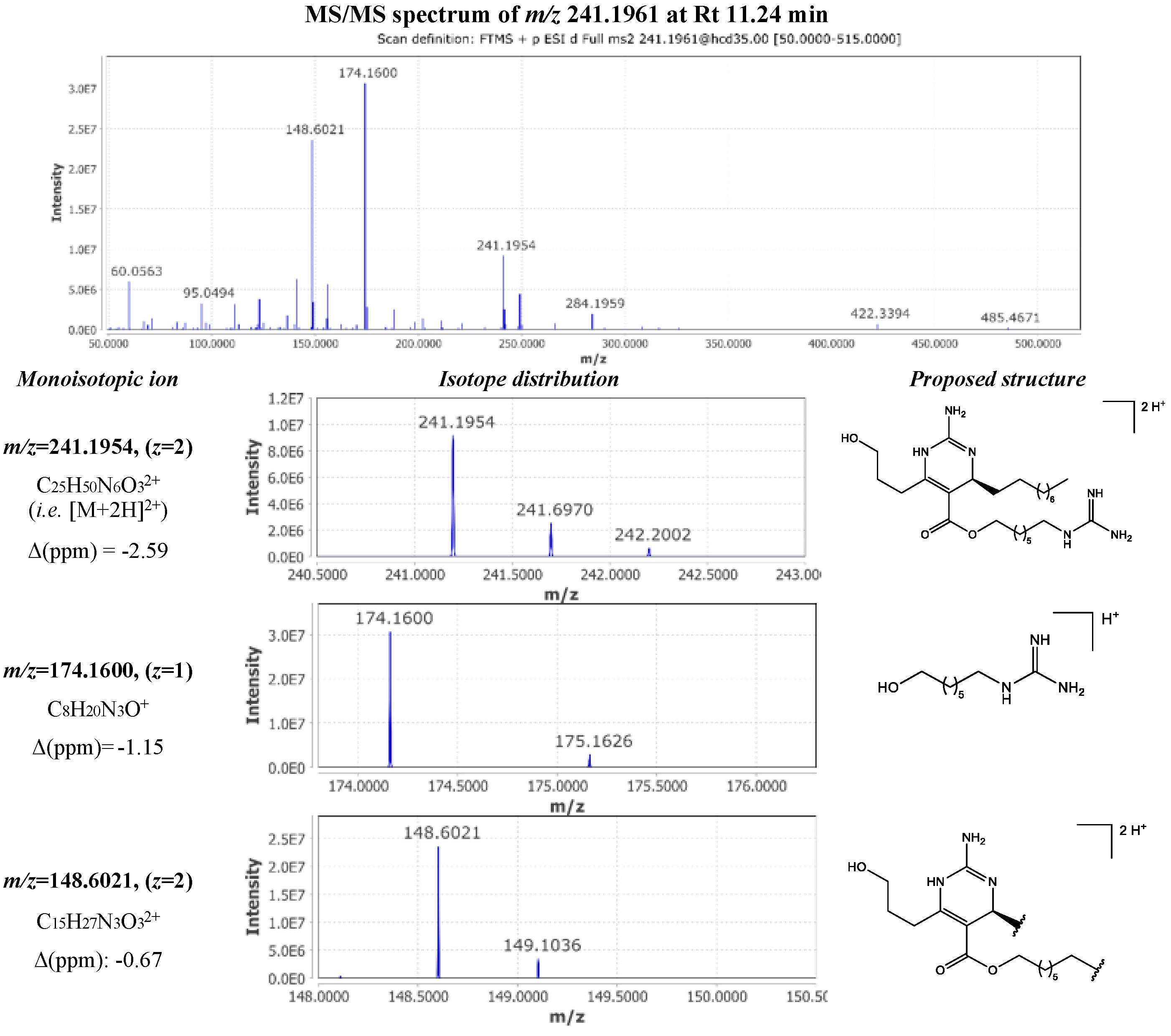

| 16 | 241.1961 | 11.24 | 2 | 480.3765 | C25H48N6O3 | -2.46 | 174.1600 (1); 148.6021 (2) | crambescin C1 480 (m=5, n=6) |

[11] |

| 17 | 218.1757 | 11.27 | 2 | 434.3357 | C23H42N6O2 | -0.58 | 127.0864 (2); 197.1646 (2); 132.1130 (1); 262.2150 (1) | crambescin A2 434 (m=2, n=7) |

|

| 18 | 249.1829 | 11.33 | 2 | 496.3502 | C28H44N6O2 | -2.79 | 114.1028 (1); 384.2650 (1); 132.1131 (1); 228.1724 (2) | crambescin A3 496 (m=2) (cis) |

|

| 19 | 225.1834 | 11.36 | 2 | 448.3513 | C24H44N6O2 | -0.78 | 204.1722 (2); 141.1018 (2); 160.1441 (1); 248.2002 (1) | crambescin A1 448 (m=4, n=6) |

|

| 20 | 234.1884 | 11.43 | 2 | 466.3612 | C24H46N6O3 | -1.93 | 132.1131 (1); 127.5783 (2) | crambescin C2 466 (m=2, n=8) |

|

| 21 | 156.1748 (1); 111.0443 (1); 160.1441 (1) | crambescin B1 466 (m=4, n=6) |

[11] | ||||||

| 22 | 248.2038 | 11.49 | 2 | 494.3921 | C26H50N6O3 | -2.46 | 188.1756 (1); 155.6091 (2) | crambescin C1 494 (m=6, n=6) |

[11] |

| 23 | 238.1909 | 11.51 | 2 | 474.3662 | C26H46N6O2 | -2.02 | 188.1756 (1); 217.1806 (2); 155.1178 (2); 170.1650 (1) | didehydrocrambescin A1 474 (m=6, n=6) | |

| 24 | 241.1960 | 11.55 | 2 | 480.3765 | C25H48N6O3 | -2.58 | 142.1585 (1); 111.0443 (1); 188.1756 (1); 298.2106 (1) | crambescin B 480 homologue (m=6, n=5) |

|

| 25 | 256.1910 | 11.55 | 2 | 510.3664 | C29H46N6O2 | -1.57 | 128.1178 (1); 384.2652 (1); 235.1809 (2); 146.1287 (1) | crambescin A3 510 (m=3) (cis) |

|

| 26 | 249.1829 | 11.62 | 2 | 496.3502 | C28H44N6O2 | -2.73 | 132.1131 (1); 114.1028 (1); 127.0864 (2); 384.2638 (1) | crambescin A3 496 (m=2) (trans) |

|

| 27 | 232.1909 | 11.62 | 2 | 462.3663 | C25H46N6O2 | -1.99 | 211.1798 (2); 174.1599 (1); 148.1093 (1); 248.2003 (1) | crambescin A1 462 (m=5, n=6) |

[11] |

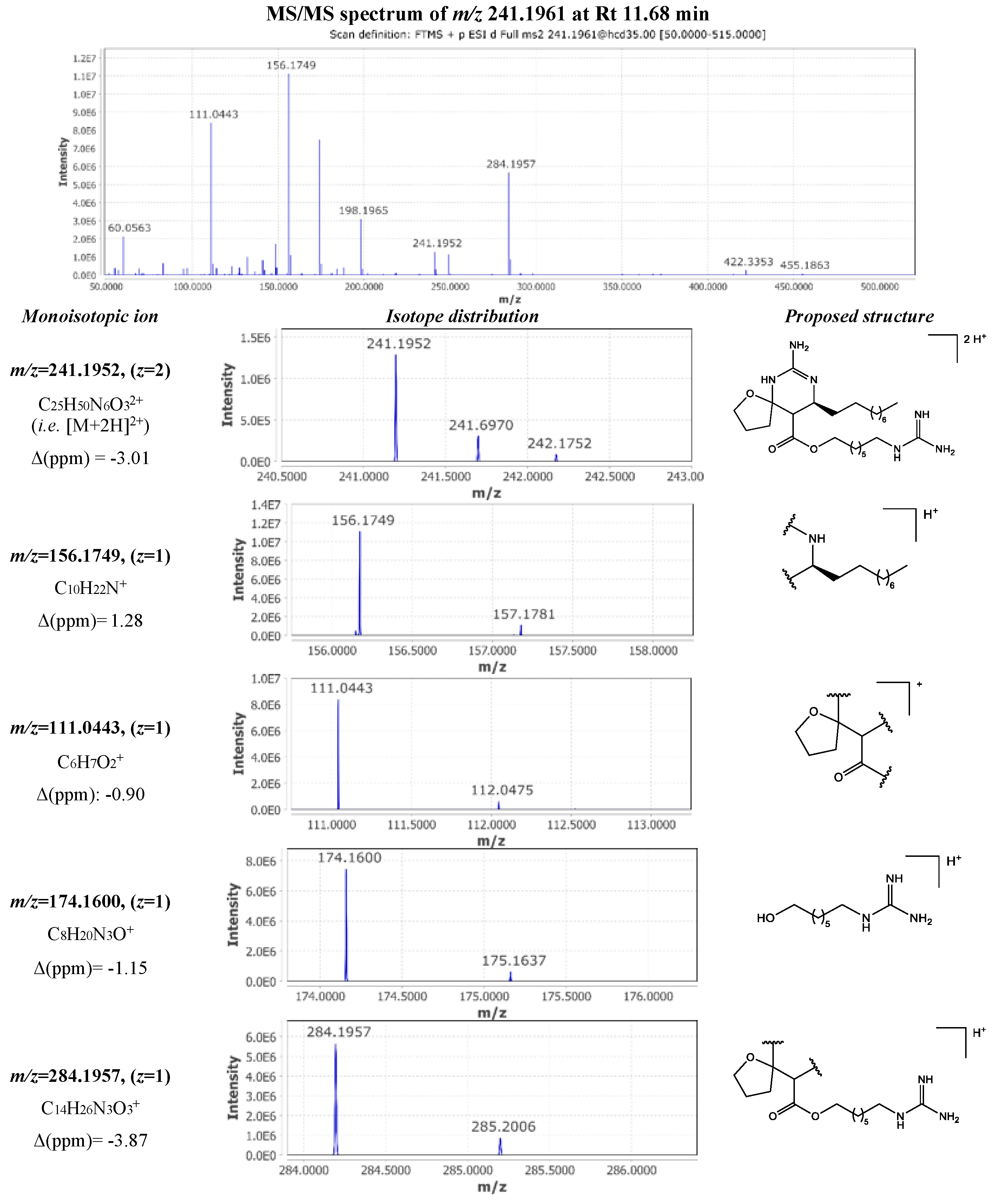

| 28 | 241.1961 | 11.68 | 2 | 480.3765 | C25H48N6O3 | -2.46 | 156.1749 (1); 111.0443 (1); 174.1600 (1); 284.1957 (1) | crambescin B1 480 (m=5, n=6) |

[11] |

| 29 | 248.2039 | 11.68 | 2 | 494.3921 | C26H50N6O3 | -2.40 | 132.1131 (1); 127.0865 (2); 114.1026 (1) | crambescin C2 494 (m=2, n=10) |

|

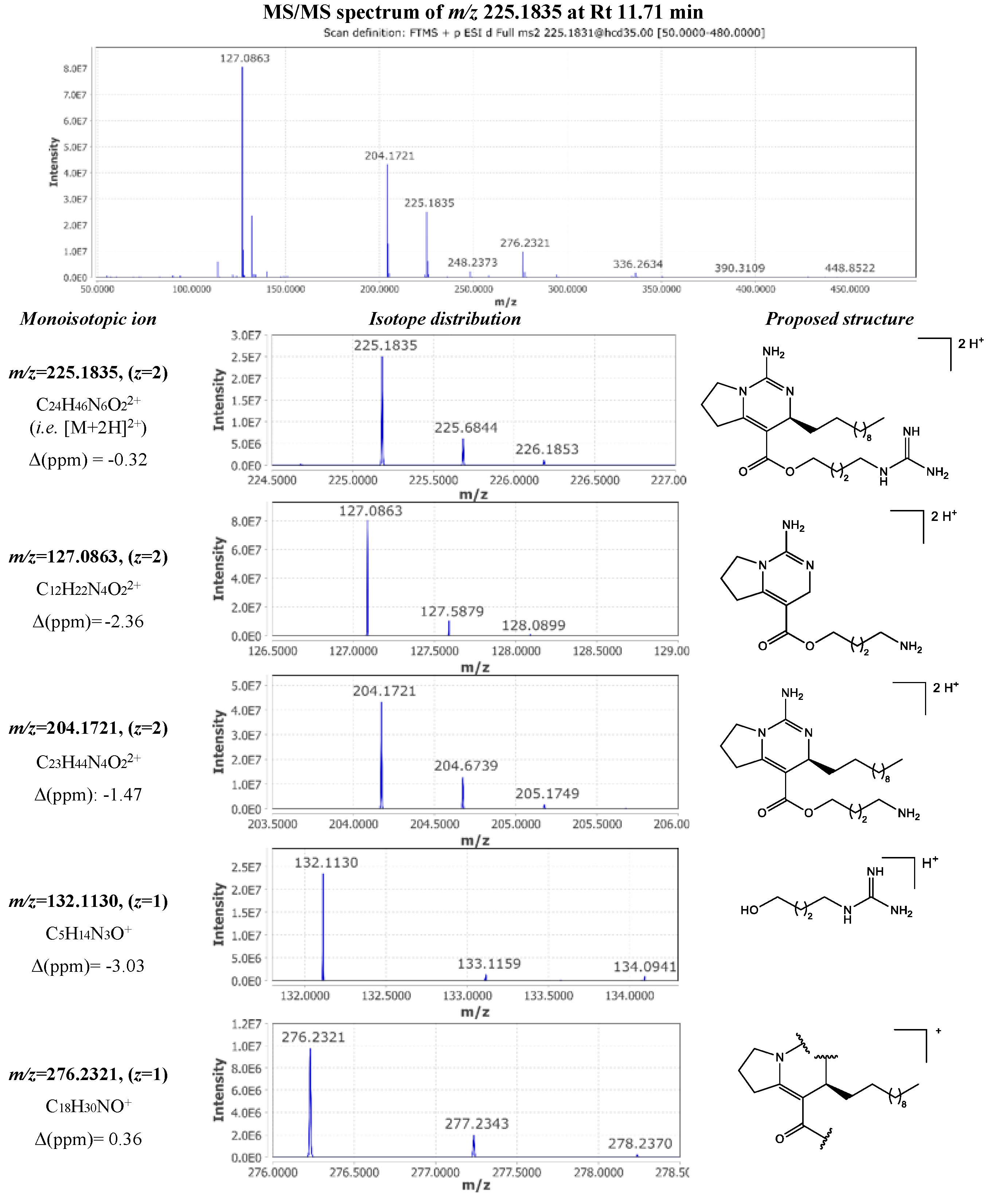

| 30 | 225.1835 | 11.70 | 2 | 448.3513 | C24H44N6O2 | -0.64 | 127.0863 (2); 204.1721 (2); 132.1130 (1); 276.2321 (1) | crambescin A2 448 (m=2, n=8) |

[11] |

| 31 | 272.2038 | 11.71 | 2 | 542.3920 | C30H50N6O3 | -2.40 | 160.1441 (1); 142.1335 (1) | crambescin C3 542 (m=4) |

[12] |

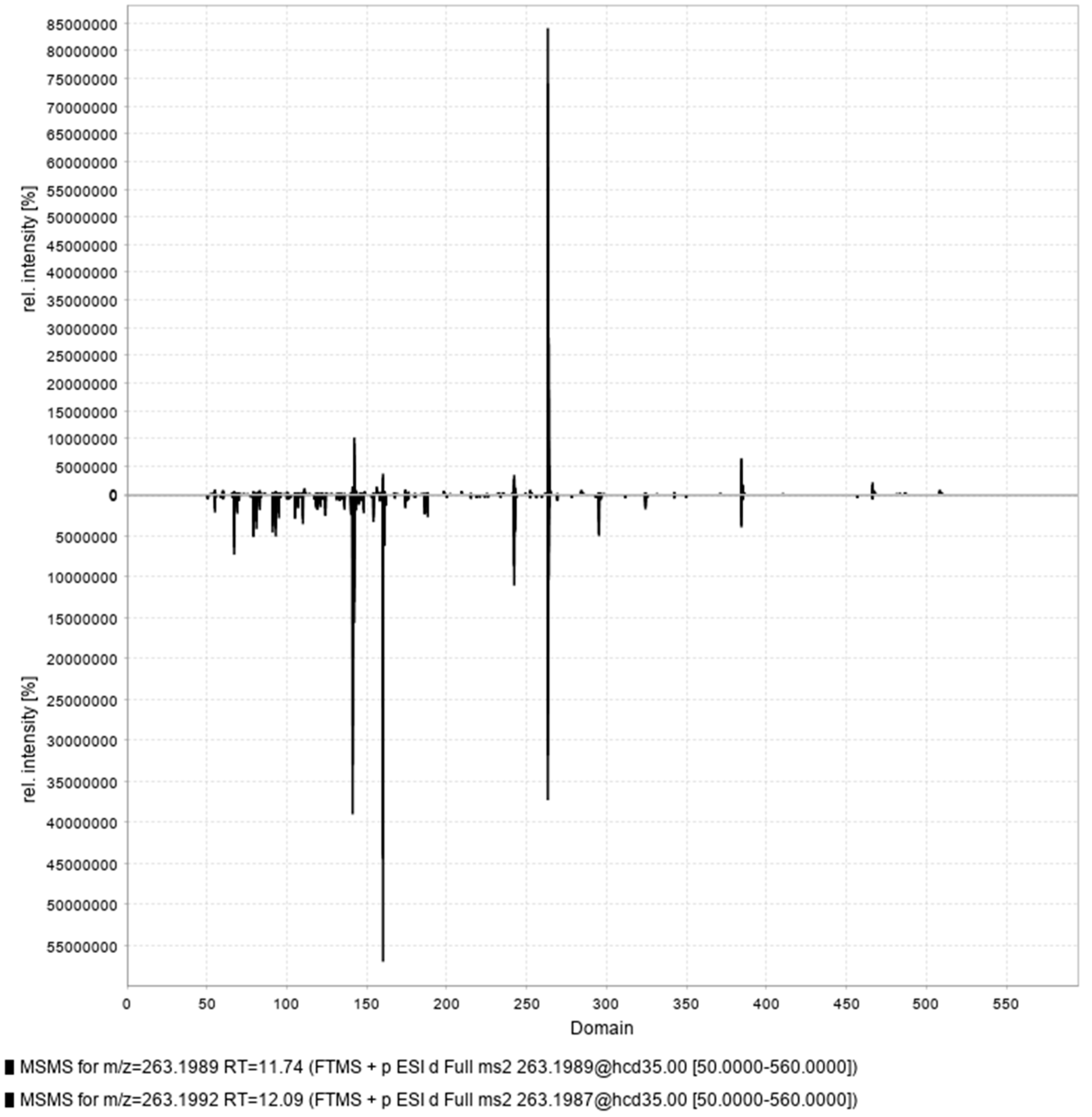

| 32 | 267.8778 | 11.73 | 3 | 800.6100 | C45H80N6O6 | -2.50 | 70.0657 (1); 349.2648 (2); 206.1536 (1); 392.3078 (2) d | crambescidin 800 or isocrambescidin 800 | [13,14] |

| 33 | 263.1990 | 11.79 | 2 | 524.3824 | C30H48N6O2 | -0.76 | 142.1334 (1); 384.2649 (1); 160.1440 (1); 242.1875 (2) | crambescin A3 524 (m=4) (cis) |

[12] |

| 34 | 256.1910 | 11.81 | 2 | 510.3664 | C29H46N6O2 | -1.65 | 146.1287 (1); 134.0943 (2); 128.1178 (1); 235.1805 (2) | crambescin A3 510 (m=3) (trans) |

|

| 35 | 286.8851 | 11.83 | 3 | 857.6318 | C44H85N6O10 | 1.41 | 264.1703 (1); 139.0749 (1); 246.1602 (1); 381.3456 (1) | crambescidin 857 | |

| 36 | 273.2094 | 11.84 | 3 | 816.6048 | C45H80N6O7 | -2.53 | 264.1707 (1); 246.1587 (1); 139.0751 (1); 70.0657 (1) d | crambescidin 816 | [14] |

| 37 | 234.1884 | 11.88 | 2 | 466.3613 | C24H46N6O3 | -1.77 | 184.2054 (1); 132.1131 (1); 114.1028 (1); 242.1484 (1) | crambescin B2 466 (m=2, n=8) |

|

| 38 | 239.1989 | 11.90 | 2 | 476.3821 | C26H48N6O2 | -1.39 | 188.1756 (1); 156.174 (1); 111.0443 (1); 218.1873 (2) | crambescin A1 476 (m=6, n=6) |

|

| 39 | 281.5530 | 11.94 | 3 | 841.6355 | C44H85N6O9 | -0.20 | 263.1982 (1); 70.0657 (1); 116.1071 (1); 139.0751 (1) | crambescidin 841 | |

| 40 | 267.8778 | 11.94 | 3 | 800.6099 | C45H80N6O6 | -2.58 | 70.0657 (1); 349.2647 (2); 392.3078 (2); 206.1537 (1) d | crambescidin 800 or isocrambescidin 800 | [13,14] |

| 41 | 248.2039 | 11.94 | 2 | 494.3921 | C26H50N6O3 | -2.34 | 156.1749 (1); 111.0444 (1); 188.1756 (1); 298.2130 (1) | crambescin B1 494 (m=6, n=6) |

[11] |

| 42 | 232.1910 | 11.98 | 2 | 462.3664 | C25H46N6O2 | -1.73 | 211.1799 (2); 134.0942 (2); 146.1287 (1); 276.2325 (1) | crambescin A 462 homologue (m=3, n=8) |

|

| 43 | 238.1908 | 11.98 | 2 | 474.3659 | C26H46N6O2 | -2.74 | 127.0864 (2); 132.1131 (1); 217.1807 (2); 114.1028 (1) | didehydrocrambescin A2 474 (m=2, n=10) | |

| 44 | 270.2066 | 12.03 | 2 | 538.3977 | C31H50N6O2 | -1.36 | 497.3828 (1); 384.2652 (1); 522.3766 (1); 174.1602 (1) c | crambescin A3 538 (m=5) (cis) |

[12] |

| 45 | 263.1990 | 12.03 | 2 | 524.3825 | C30H48N6O2 | -0.63 | 160.1441 (1); 141.1018 (2); 242.1877 (2); 384.2650 (1) | crambescin A3 524 (m=4) (trans) |

[12] |

| 46 | 232.1910 | 12.11 | 2 | 462.3664 | C25H46N6O2 | -1.82 | 127.0864 (2); 211.1799 (2); 132.113 (1); 290.2473 (1) | crambescin A2 462 (m=2, n=9) |

[11] |

| 47 | 416.3195 | 12.16 | 2 | 830.6233 | C46H82N6O7 | 0.98 | 264.1707 (1); 246.1587 (1); 70.0657 (1); 139.0751 (1) | crambescidin 830 | [14] |

| 48 | 272.2037 | 12.18 | 2 | 542.3917 | C30H50N6O3 | -2.92 | 160.1441 (1); 111.0443 (1); 232.2046 (1); 274.2275 (1) | crambescin B3 542 (m=4) |

[12] |

| 49 | 270.2066 | 12.27 | 2 | 538.3976 | C31H50N6O2 | -1.49 | 174.1597 (1); 148.1098 (2); 249.1955 (2); 156.1493 (1) | crambescin A3 538 ( m=5) (trans) |

[12] |

| 50 | 404.2534 | 12.32 | 1 | 403.2463 | C22H33O4N3 | -1.74 | 360.2640 (1); 206.1536 (1); 342.2542 (1); 60.0562 (1) | crambescidin acid | [37] |

| 51 | 239.1988 | 12.51 | 2 | 476.3820 | C26H48N6O2 | -1.65 | 127.0864 (2); 218.1873 (2); 132.113 (1); 304.2617 (1) | crambescin A2 476 (m=2, n=10) |

[11] |

| 52 | 254.2221 | 12.51 | 1 | 253.2148 | C14H27N3O | -1.97 | 195.1740 (1); 97.0651 (1); 60.0562 (1); 111.0442 (1) | crambescin 253 | [37] |

| IS | 609.2800 | 12.59 | 1 | 608.2722 | C33H40N2O9 | -0.22 | 195.0642 (1); 174.0913; 397.2098 (1); 448.1952 (1) | reserpine | |

| 53 | 282.2534 | 13.77 | 1 | 281.2460 | C16H31N3O | -1.42 | 114.9612 (1); 223.2051 (1); 97.0651 (1); 60.0562 (1) | crambescin 281 | [37] |

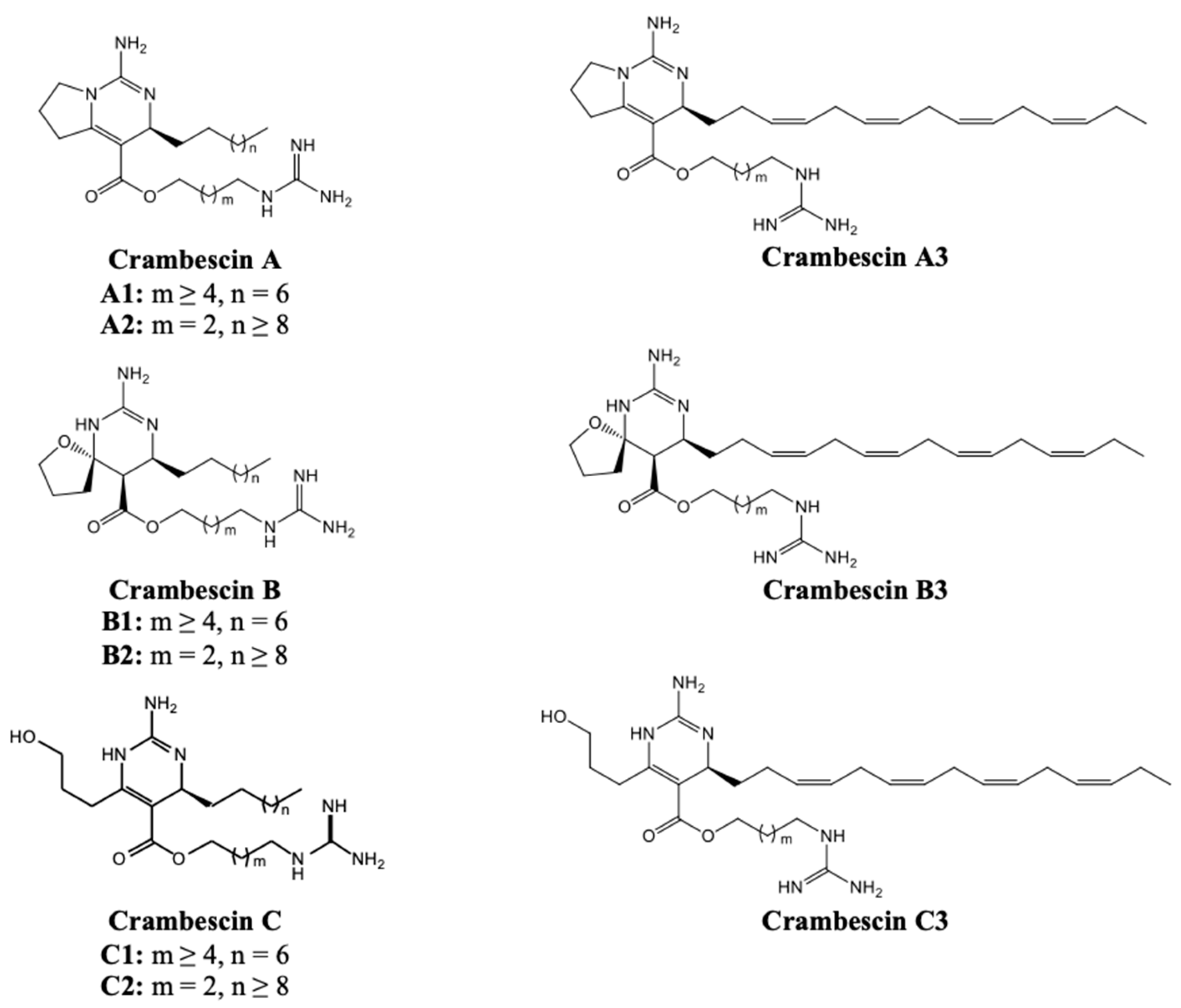

2.1. Crambescins A

2.2. Crambescins B and C

2.3. Crambescindins and Other Guanidine Alkaloids

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Sample Preparation

3.3. UHPLC-HRMS/MS Analysis

3.4. Molecular Networking/Computational Chemical Dereplication

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duran, S.; Pascual, M.; Estoup, A.; Turon, X. Strong Population Structure in the Marine Sponge Crambe Crambe (Poecilosclerida) as Revealed by Microsatellite Markers. Molecular Ecology 2004, 13, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfecci, E.; Lacour, T.; Amade, P.; Mehiri, M. Polycyclic Guanidine Alkaloids from Poecilosclerida Marine Sponges. Marine Drugs 2016, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.B.L.; Oberhänsli, F.; Tribalat, M.-A.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Teyssié, J.-L.; Dechraoui-Bottein, M.-Y.; Gallard, J.-F.; Evanno, L.; Poupon, E.; Thomas, O.P. Insights into the Biosynthesis of Cyclic Guanidine Alkaloids from Crambeidae Marine Sponges. Angewandte Chemie 2019, 131, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternon, E.; Perino, E.; Manconi, R.; Pronzato, R.; Thomas, O.P. How Environmental Factors Affect the Production of Guanidine Alkaloids by the Mediterranean Sponge Crambe Crambe. Mar Drugs 2017, 15, E181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarieva, T.; Shubina, L.; Kurilenko, V.; Isaeva, M.; Chernysheva, N.; Popov, R.; Bystritskaya, E.; Dmitrenok, P.; Stonik, V. Marine Bacterium Vibrio Sp. CB1-14 Produces Guanidine Alkaloid 6-Epi-Monanchorin, Previously Isolated from Marine Polychaete and Sponges. Mar Drugs 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, B.; de Jaeger, L.; Smidt, H.; Sipkema, D. Culture-Dependent and Independent Approaches for Identifying Novel Halogenases Encoded by Crambe Crambe (Marine Sponge) Microbiota. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerro, M.A.; Lopez, N.I.; Turon, X.; Uriz, M.J. Antimicrobial Activity and Surface Bacterial Film in Marine Sponges. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 1994, 179, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovio, E.; Sfecci, E.; Poli, A.; Gnavi, G.; Prigione, V.; Lacour, T.; Mehiri, M.; Varese, G.C. The Culturable Mycobiota Associated with the Mediterranean Sponges Aplysina Cavernicola, Crambe Crambe and Phorbas Tenacior. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croué, J.; West, N.J.; Escande, M.-L.; Intertaglia, L.; Lebaron, P.; Suzuki, M.T. A Single Betaproteobacterium Dominates the Microbial Community of the Crambescidine-Containing Sponge Crambe Crambe. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipkema, D.; Caralt, S. de; Morillo, J.A.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Smidt, H.; Uriz, M.J. Similar Sponge-Associated Bacteria Can Be Acquired via Both Vertical and Horizontal Transmission. Environmental Microbiology 2015, 17, 3807–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondu, S.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Leirόs, M.; Vale, C.; Guigonis, J.-M.; Botana, L.M.; Thomas, O.P. Additional Bioactive Guanidine Alkaloids from the Mediterranean Sponge Crambe Crambe. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternon, E.; Zarate, L.; Chenesseau, S.; Croué, J.; Dumollard, R.; Suzuki, M.T.; Thomas, O.P. Spherulization as a Process for the Exudation of Chemical Cues by the Encrusting Sponge C. Crambe. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 29474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jares-Erijman, E.; Ingrum, A.L.; Carney, J.; Rinehart, K.; Sakai, R. Polycyclic Guanidine-Containing Compounds from the Mediterranean Sponge Crambe Crambe: The Structure of 13,14,15-Isocrambescidin 800 and the Absolute Stereochemistry of the Pentacyclic Guanidine Moieties of the Crambescidins. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Jares-Erijman, E.A.; Sakai, R.; Rinehart, K.L. Crambescidins: New Antiviral and Cytotoxic Compounds from the Sponge Crambe Crambe. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/jo00019a049 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Rinehart, K.L.; Jares-Erijman, E.A. Antiviral and Cytotoxic Compounds from the Sponge Crambe Crambe 1999.

- Aoki, S.; Kong, D.; Matsui, K.; Kobayashi, M. Erythroid Differentiation in K562 Chronic Myelogenous Cells Induced by Crambescidin 800, a Pentacyclic Guanidine Alkaloid. Anticancer Research 2004, 24, 2325–2330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Demerdash, A.; Metwaly, A.M.; Hassan, A.; Abd El-Aziz, T.M.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Eissa, I.H.; Arafa, R.K.; Stockand, J.D. Comprehensive Virtual Screening of the Antiviral Potentialities of Marine Polycyclic Guanidine Alkaloids against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Biomolecules 2021, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Demerdash, A.; Petek, S.; Debitus, C.; Al-Mourabit, A. Crambescidin Acid from the French Polynesian Monanchora n. Sp. Marine Sponge. Chem Nat Compd 2020, 56, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmiati, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Ojika, M. New Crambescidin-Type Alkaloids from the Indonesian Marine Sponge Clathria Bulbotoxa. Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, V.; Vale, C.; Bondu, S.; Thomas, O.P.; Vieytes, M.R.; Botana, L.M. Differential Effects of Crambescins and Crambescidin 816 in Voltage-Gated Sodium, Potassium and Calcium Channels in Neurons. Chem Res Toxicol 2013, 26, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, A.G.; Juncal, A.B.; Silva, S.B.L.; Thomas, O.P.; Martín Vázquez, V.; Alfonso, A.; Vieytes, M.R.; Vale, C.; Botana, L.M. The Marine Guanidine Alkaloid Crambescidin 816 Induces Calcium Influx and Cytotoxicity in Primary Cultures of Cortical Neurons through Glutamate Receptors. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roel, M.; Rubiolo, J.A.; Guerra-Varela, J.; Silva, S.B.L.; Thomas, O.P.; Cabezas-Sainz, P.; Sánchez, L.; López, R.; Botana, L.M. Marine Guanidine Alkaloids Crambescidins Inhibit Tumor Growth and Activate Intrinsic Apoptotic Signaling Inducing Tumor Regression in a Colorectal Carcinoma Zebrafish Xenograft Model. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 83071–83087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Sorolla, A.; Fromont, J.; Blancafort, P.; Flematti, G.R. Crambescidin 800, Isolated from the Marine Sponge Monanchora Viridis, Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, J.E.H.; Nitcheu, J.; Mahmoudi, N.; Ibana, J.A.; Mangalindan, G.C.; Black, G.P.; Howard-Jones, A.G.; Moore, C.G.; Thomas, D.A.; Mazier, D.; et al. Antimalarial Activity of Crambescidin 800 and Synthetic Analogues against Liver and Blood Stage of Plasmodium Sp. The Journal of Antibiotics 2006, 59, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.Y.; Sanchez, L.M.; Rath, C.M.; Liu, X.; Boudreau, P.D.; Bruns, N.; Glukhov, E.; Wodtke, A.; De Felicio, R.; Fenner, A.; et al. Molecular Networking as a Dereplication Strategy. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1686–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.T.; Gentry, E.C.; McPhail, K.L.; Nothias, L.-F.; Nothias-Esposito, M.; Bouslimani, A.; Petras, D.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Sikora, N.; Vargas, F.; et al. Reproducible Molecular Networking of Untargeted Mass Spectrometry Data Using GNPS. Nat Protoc 2020, 15, 1954–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nothias, L.-F.; Petras, D.; Schmid, R.; Dührkop, K.; Rainer, J.; Sarvepalli, A.; Protsyuk, I.; Ernst, M.; Tsugawa, H.; Fleischauer, M.; et al. Feature-Based Molecular Networking in the GNPS Analysis Environment. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, V.F.; Gubiani, J.R.; Spencer, T.M.; Hajdu, E.; Ferreira, A.G.; Ferreira, D.A.S.; De Castro Levatti, E.V.; Burdette, J.E.; Camargo, C.H.; Tempone, A.G.; et al. Feature-Based Molecular Networking Discovery of Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from the Marine Sponge Agelas Dispar. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khushi, S.; Salim, A.A.; Capon, R.J. Case Studies in Molecular Network-Guided Marine Biodiscovery. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluskal, T.; Castillo, S.; Villar-Briones, A.; Orešič, M. MZmine 2: Modular Framework for Processing, Visualizing, and Analyzing Mass Spectrometry-Based Molecular Profile Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Fleischauer, M.; Ludwig, M.; Aksenov, A.A.; Melnik, A.V.; Meusel, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. SIRIUS 4: A Rapid Tool for Turning Tandem Mass Spectra into Metabolite Structure Information. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Shen, H.; Meusel, M.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. Searching Molecular Structure Databases with Tandem Mass Spectra Using CSI:FingerID. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, 12580–12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Nothias, L.-F.; Fleischauer, M.; Reher, R.; Ludwig, M.; Hoffmann, M.A.; Petras, D.; Gerwick, W.H.; Rousu, J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; et al. Systematic Classification of Unknown Metabolites Using High-Resolution Fragmentation Mass Spectra. Nat Biotechnol 2021, 39, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and Community Curation of Mass Spectrometry Data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat Biotechnol 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, M.T.; Molinski, T.F. Antipodal Crambescin A2 Homologues from the Marine Sponge Pseudaxinella Reticulata. Antifungal Structure–Activity Relationships. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachou, P.; Le Goff, G.; Alonso, C.; Álvarez, P.A.; Gallard, J.-F.; Fokialakis, N.; Ouazzani, J. Innovative Approach to Sustainable Marine Invertebrate Chemistry and a Scale-Up Technology for Open Marine Ecosystems. Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, D.S.; McDonald, A.I.; Overman, L.E.; Rabinowitz, M.H.; Renhowe, P.A. A Practical Entry to the Crambescidin Family of Guanidine Alkaloids. Enantioselective Total Syntheses of Ptilomycalin A, Crambescidin 657 and Its Methyl Ester (Neofolitispates 2), and Crambescidin 800. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4893–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkscape Project 2021.

- de Laeter, J.R.; Böhlke, J.K.; De Bièvre, P.; Hidaka, H.; Peiser, H.S.; Rosman, K.J.R.; Taylor, P.D.P. Atomic Weights of the Elements. Review 2000 (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2003, 75, 683–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genta-Jouve, G.; Croué, J.; Weinberg, L.; Cocandeau, V.; Holderith, S.; Bontemps, N.; Suzuki, M.; Thomas, O.P. Two-Dimensional Ultra High Pressure Liquid Chromatography Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Semi-Targeted Natural Compounds Identification. Phytochemistry Letters 2014, 10, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.M. Understanding Mass Spectra: A Basic Approach; 2nd ed.; Wiley Interscience: Hoboken, N.J, 2004; ISBN 978-0-471-42949-4. [Google Scholar]

- WoRMS Editorial Board World Register of Marine Species. Available from Https://Www.Marinespecies.Org at VLIZ. Accessed Yyyy-Mm-Dd. 2024.

- Chambers, M.C.; Maclean, B.; Burke, R.; Amodei, D.; Ruderman, D.L.; Neumann, S.; Gatto, L.; Fischer, B.; Pratt, B.; Egertson, J.; et al. A Cross-Platform Toolkit for Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics. Nat Biotechnol 2012, 30, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusumilli, R.; Mallick, P. Data Conversion with ProteoWizard msConvert. In Proteomics; Comai, L., Katz, J.E., Mallick, P., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2017; Vol. 1550, pp. 339–368 ISBN 978-1-4939-6745-2.

- Treviño, V.; Yañez-Garza, I.-L.; Rodriguez-López, C.E.; Urrea-López, R.; Garza-Rodriguez, M.-L.; Barrera-Saldaña, H.-A.; Tamez-Peña, J.G.; Winkler, R.; Díaz de-la-Garza, R.-I. GridMass: A Fast Two-Dimensional Feature Detection Method for LC/MS: GridMass: 2D Feature Detection for LC/MS. J. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 50, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Wang, M.; Leber, C.A.; Nothias, L.-F.; Reher, R.; Kang, K.B.; Van Der Hooft, J.J.J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Gerwick, W.H.; Cottrell, G.W. NPClassifier: A Deep Neural Network-Based Structural Classification Tool for Natural Products. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotly Technologies Inc. Collaborative Data Science 2015.

- yWorks yFiles Layouts in Cytoscape 3.6.0. 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).