Introduction

During the 20th century were established the foundations of modern cosmology. The field equations of general relativity were formulated by Einstein [

1]. The definition of new metrics based on the cosmological principle with the properties of homogeneity and isotropy allowed the physicists the application of Einstein’s field equations to the universe. While Einstein defined a static metric, Friedmann [

2] deduced mathematically a non-stationary model with a time-dependent factor

. The solution was independently derived by Lemaître [

3] interpreting a(t) as a scale factor of an expanding universe. The work was completed by Robertson[

4] and Walker [

5] in what is known as the

Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric.

Contemporaneously to these achievements, a correlation between redshifts and distances for extragalactic sources was found by Hubble [

6]. The origin of this correlation was subject of intense debate between proponents of static and expanding universes on the 1930s ([

7]). The fault of the Einstein’s static universe to explain the redshift of galaxies leaned the balance to the FLRW metric, whose time dependent factor

can directly explain the cosmological redshift ([

8]). The FLRW model describes a solutions to the Einstein’s field equations for a homogeneous and isotropic universe. The evolution and fate of the Universe depends on the nature of different density components, i.e., radiation, matter, curvature and dark energy. But as shown below, the FLRW metric also support a non-expanding universe accounting for the observed cosmological redshift.

Different cosmological tests were proposed to probe whether the Universe is expanding or remains static. Tolman [

9] predicted that in an expanding universe, the surface brightness of a receding source with redshift

z will be dimmed by

. Consequently to Tolman’s prediction, the equation

, with

was established between

luminosity distance and

angular diameter distance for a expanding universe. There are contradictory studies, some of them claim for expansion ([

10,

11]) while other ([

12,

13,

14]) are advocating for a static universe. Nevertheless, neither expanding nor static studies are conclusive, since they depend on an uncertain possible galaxy evolution. On the other hand, the time dilation of Type Ia supernovae light curves suggested by Wilson [

15], and confirmed by Goldhaber[

16], are assumed in favor of cosmological expansion though the same phenomenon can be described in a non-expanding universe as shown below. An extensive review of theories and results supporting a non-expanding universe can be found elsewhere [

17]. In this work, we show that the FLRW metric admits a non-expanding interpretation, different from the Einstein’s static universe, therefore stable, and with a feasible cosmological redshift explanation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 1 describes the foundations of the expanding universe.

Section 2 shows some weakness of the expanding interpretation of FLRW metric. A non-expanding interpretation of FLRW metric is given in

Section 3.

Section 4 explores the variable magnetic permeability as a possible explanation of the redshift within a non-expanding universe. The conclusions are presented in

Section 5.

1. Foundations of the Expanding Universe

The expanding universe rest on the Einstein’s field equation given by

where

is the Ricci curvature tensor,

is the scalar curvature,

is the energy momentum tensor and

metric tensor. The form of

for a homogeneous and isotropic universe is know as the FLRW metric and is given by

being

where k describes the curvature, while a(t) is a time-dependent factor commonly interpreted as the scale factor of an expanding universe. There are different distance ladders relating theory and observations. Let us to provide a brief summary of some distance definitions and their relations with normalized densities (

,

,

,

), corresponding to matter, radiation, cosmological constant and curvature ([

18]) respectively. The first Friedmann equation can be expressed from the Hubble parameter

H at any time, and the Hubble constant

today as

where

By integrating Equation

2 along with Equation

4 one can obtain the line of sight

comoving distance as

where

is the

Hubble distance. From the same equations one can get the

transverse comoving distance as

With respect to observable quantities, the

angular diameter distance is defined as the ratio between the object physical size

S and its angular size

The

angular diameter distance is related to the

transverse comoving distance by

where z is the redshift. On the other hand, the

luminosity distance defines the relation between the bolometric flux energy

f received at earth from an object, to its bolometric luminosity L by means of

or finding

The relation between

and

is given by

and taking into account Equation

9

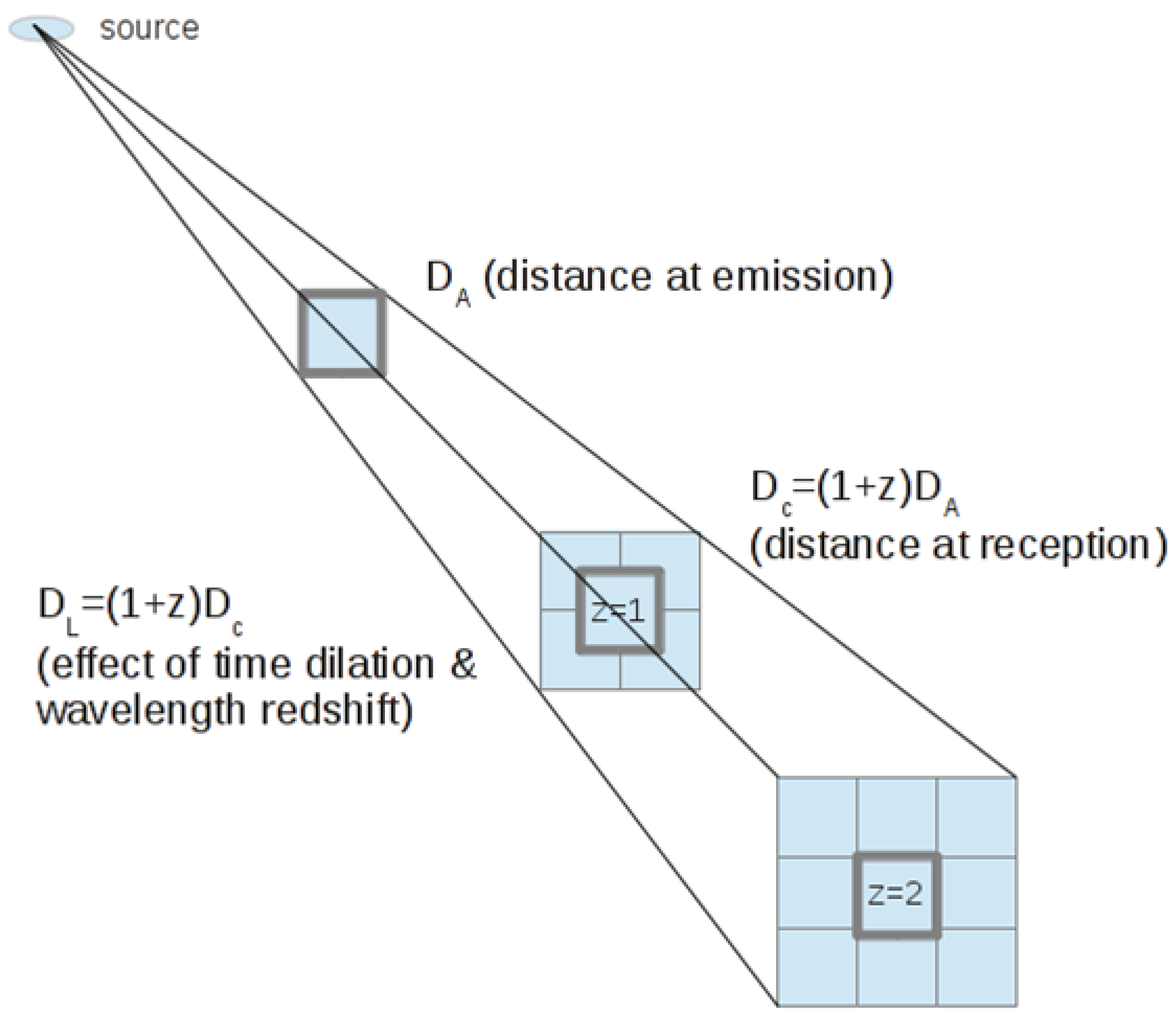

There are four (1+z) factors affecting to flux energy diminution (

Figure 1). Two come from the elongation of the initial distance

by a factor of

due to universe expansion according to the inverse square law. Another factor comes from the time dilation due to universe expansion that reduces the photon emission/reception rate by

. The last factor comes from the cosmological wavelength redshift that decrease the energy of photons by

. Therefore, a relevant relation is established between the

angular diameter distance and the

luminosity distance in the

expanding universe as

Equation

14 is commonly known as Etherington distance-duality relation.

2. Weakness of the Expanding Interpretation of FLRW Metric

Let us to focus on the expanding interpretation of the FLRW metric. The radial coordinate

r in Equation

2 is commonly interpreted as a comoving radial coordinate and hence the base for comoving distance (

) computation, rather than luminosity distance

. Thus, note the observable luminosity distance

given by Equation

11, which depends on the flux of energy, is not related with the energy momentum tensor

in spite of both treat with energy. It is required to define an additional equation

to relate the luminosity distance

with the comoving distance

, and hence with Einstein’s field equation. Note that it is not

, but the consideration of

r in FLRW metric as a radial comoving coordinate, that push the FLRW model to be interpreted as an expanding one.

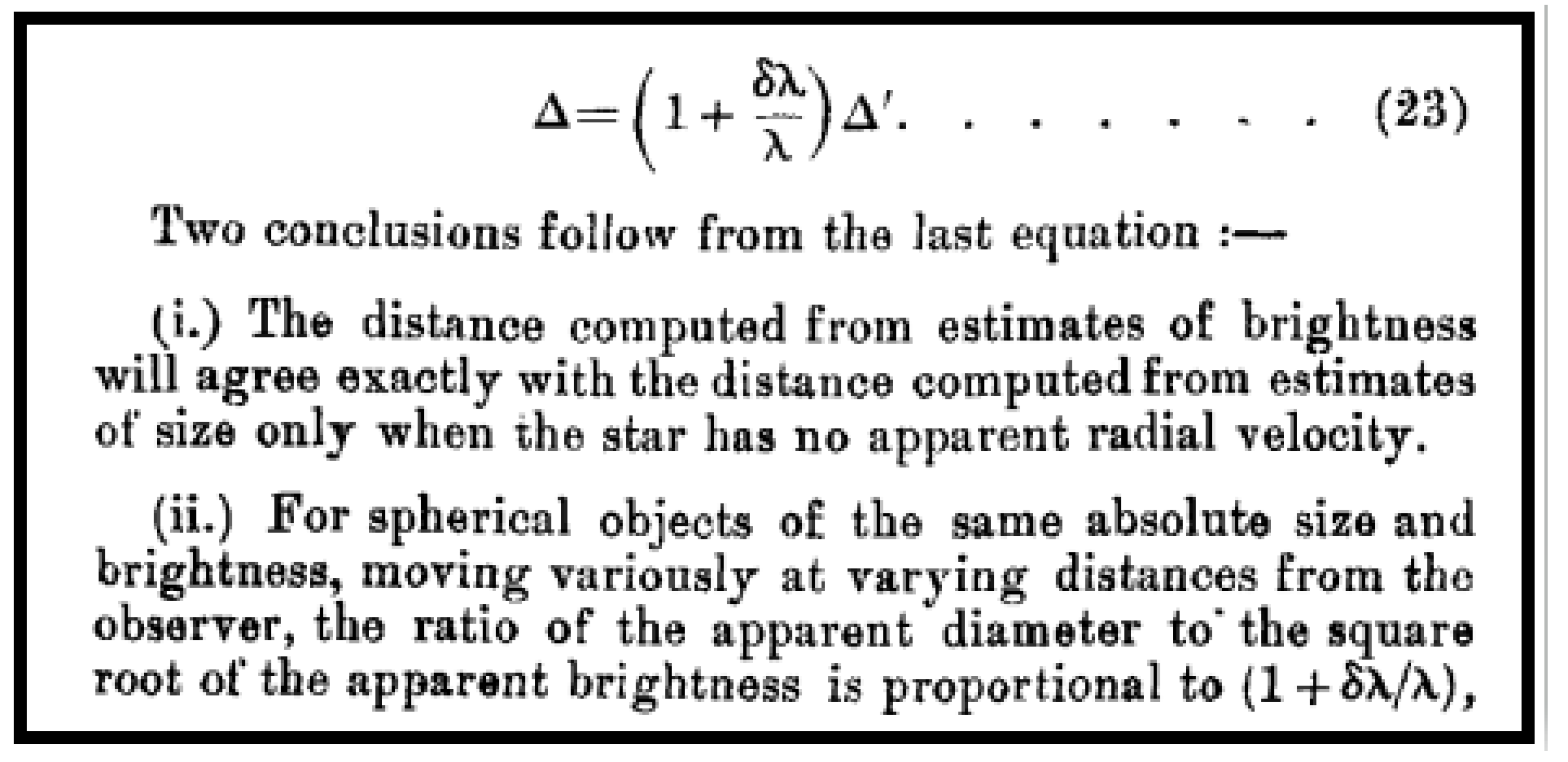

A similar question arise with respect to Etherington relation.

Figure 2 shows the relation between the luminosity distance

and the angular diameter distance

derived by Etherington from general relativity. Thus, the Etherington equation is the reciprocity theorem for a local (i.e. non-expanding) universe:

Note that this equation can be adapted for an expanding universe by the introduction of an additional intermediate variable

(comoving distance), that through equations Equation

9 and Equation

15, gives the Equation

14, known as Etherington distance-duality relation. Therefore, it is by the definition of these two intermediate external equations (Equation

9 and Equation

15), that the expanding paradigm is supported.

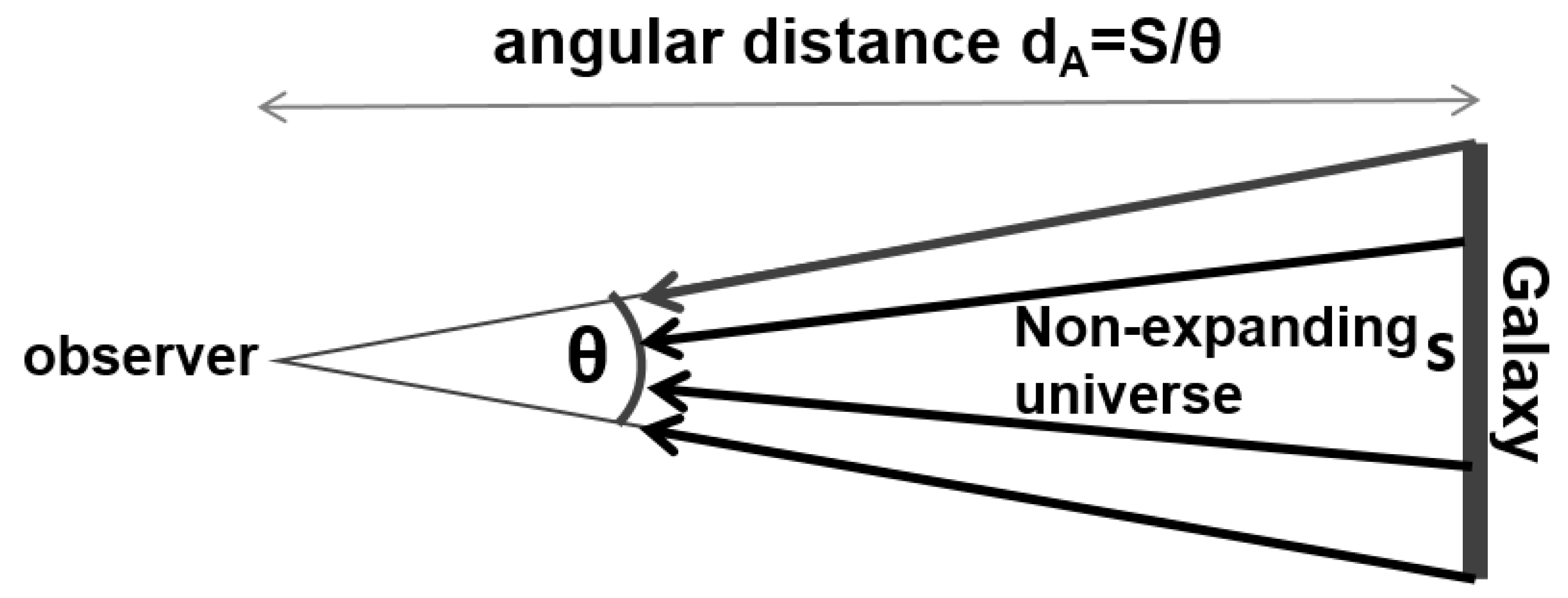

3. Non-Expanding Interpretation of FLRW Metric

Let us reflect on the same FLRW metric considered in the previous section given by

and let us to analyze the behavior of light rays considering a non-expanding universe (

Figure 3). Let the origin of coordinates be at the observer O, and considers an extended cosmological object (galaxy) initially located at a distance

from O at time of emission

. According to general relativity, light rays follow null geodesics where

. Substituting this value in Equation

17, light rays follow the equation

Note from

Figure 3 that the light rays propagate on the radial direction (leaving apart non pure cosmological effects as gravitational lensing or astrophysical events). Therefore

,

,

,

in Equation

3, and hence

. Substituting

in Equation

18, the light rays that will arrive to the observer meet

Now, integrating Equation

19 from time of emission

to time of observation

, and considering r simply as the radial coordinate rather than the radial comoving coordinate, the integration limit becomes directly the luminosity distance, dropping out the intermediate comoving distance concept. Thus, in this case we obtain

rather than

Note that in a non-expanding universe, the comoving distance

loose its meaning and it should be substituted by the luminosity distance

in all equations.

As a consequence, the radial comoving coordinate

r of the expanding FLRW model, should be interpreted as the radial coordinate on the non-expanding FLRW model. In the simplest case of a flat non-expanding universe (

), we would have

where

still would be the factor responsible of time dilation and cosmological redshift in a non-expanding universe, but with another meaning.

On the other hand, since the comoving concept disappear, we can substitute Equation

22 on Equation

7, obtaining

that directly relates the first Friedmann equation with the observable luminosity distance

, without the need to define additional intermediate equations.

In an expanding universe, the Friedmann equations constraints the form of the scale factor with the different species of the universe as radiation, matter, curvature and cosmological constant. In the non-expanding interpretation of the FLRW model, also depends exactly in the same way on the relative content of these species along cosmic time. Even more, the stability of the FLRW non-expanding universe resides on the same argumentation given for the expanding universe, but with a different interpretation, since is not related to the size of the universe. The standard model demonstrates that the geodesics for a free particle (galaxy) corresponds to fixed FLRW comoving coordinates. The same demonstration applies to non-expanding-FLRW by interpreting the radial comoving coordinate simply as the radial coordinate. Thus, geodesics for a free particle in a non-expanding universe corresponds to fixed FLRW coordinates. Therefore, it is the own FLRW metric that ensure the stability of the non-expanding universe.

Let us to consider an alternative view of the FLRW metric dividing both sides of Equation

17 by

. In this case we have

In this view, we see that a(t) may affect not only to the spatial coordinates of the FLRW metric, but alternatively to temporal behaviour or to the speed of light. In the case of constant speed of light,

, a(t) affects to the temporal behaviour as a time down-scaling rather than a space scaling. From Equation

23, we can define

in such a way that

and

, and therefore

which would explain the redshift as a time dilation.

In the next section, we explore the case of a feasible variable speed of light with cosmic time.

4. Exploring Variable Magnetic Permeability with Cosmic Time as a Possible Cause of Cosmological Redshift

In this section, we explore the possibility of variable speed of light (VSL) with cosmic time as a feasible cause of the redshift. The cosmological principle assumes a universe spatially homogeneous and spatially isotropic. It does not state that the universe is the same over time. Thus, according to the cosmological principle, we can allow a space property to change overtime. That is the case of the scale factor in the expanding universe or the speed of light in the non-expanding one. There are different VSL theories as those addressing the horizon problem ([

19,

20]) or the ones allowing the variation of speed of light between free-falling observers ([

21]). Other depart from FLRW metric as the one that assumes both expansion and VLS ([

22])(which would requires a value of

) or those assuming photons emitted at higher speed of light at earlier times, but maintaining such high velocities up to earth ([

23]), events not observed experimentally.

Though less known, there is a plausible alternative explanation to redshift based on variable speed of light with cosmic time ([

24]). Such approach would still require a spatially constant speed of light among all free falling observes as the general relativity demands. In this case, from Equation

23 we can write

where

The process of photon redshift based on a speed of light decreasing with cosmic time can be described as follow: a galaxy emits a photon at speed due to an electron transition between atomic levels at its corresponding energy , being lambda stretched out at emission due to the equation . In the travel of the photon to earth, remains constant, while the frequency decrease up to due to speed of light drop .

Such behaviour would agree with the observed redshift.

Given that the speed of light is

some of the vacuum properties, either dielectric permittivity

or magnetic permeability

, have to change with cosmic time. Since the gross atomic structure of redshifted galaxies and its corresponding energy levels depend on

, it should remain constant. Thus, we assume

being

in such a way that only magnetic fields and the fine structure constant would be affected along cosmic time. Therefore, in this case the time dependent function

defined in

metric would not correspond to an expansion, but to the square root of an increasing magnetic permeability. Consequently, the speed of light would decreases with cosmic time àccording to Equation

31, while the electric permittivity

remains constant allowing the observed atomic structures. The model can be denominated

to differentiate it from other possible alternatives.

Note that universe does not change the FLRW equation, but reinterpreted it. Thus, may assumes the main ideas of the standard model as that the early universe was hotter and dominated by radiation. But in this case, the cause of the drop in the temperature of the universe would not be expansion, but the drop of the speed of light with cosmic time. Thus, the cosmic microwave background would have been emitted at the same energy as in the standard model with values , and , and is received as c, and .

In the same sense, would meet the Friedmann equations, being the value of modulated by the same cosmological species as radiation, matter, curvature or dark energy.

5. Conclusions

The FLRW metric is a solution of the Einstein’s field equations for a homogeneous and isotropic universe. The FLRW metric is characterized by a time varying factor , which is considered as the scale factor of an expanding universe. Even more, is related through Friedman equations with the different constituents of the universe as radiation, matter, curvature or dark energy.

In this work, we show that may affect not only to the spatial part of the metric, but alternatively to the temporal behaviour or to the speed of light, whenever the FLRW radial comoving coordinate is considered simply as a radial coordinate. Consequently, the cosmological redshift can be explained by a time downscaling or a variable magnetic permeability with cosmic time respectively, rather that by a space scaling, while maintaining the main principles of the standard model.

Finally remark that the relation between the luminosity distance and the angular diameter distance is the key to elucidate between the different alternatives. Much experimental work should be focused on this topic.

Acknowledgments

Funding support for this work was provided by the Autonomous Community of Madrid through the project TEC2SPACE-CM (S2018/NMT-4291).

References

- Einstein, A. Die feldgleichungen der gravitation. Sitzung der physikalische-mathematischen Klasse 1915, 25, 844–847. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, A. Über die krümmung des raumes. Zeitschrift fur Physik 1922, 10, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G. Lemaître, G., 1927, Ann. Soc. Sci. Bruxelles, Ser. 1 47, 49. Ann. Soc. Sci. Bruxelles, Ser. 1 1927, 47, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, H.P. Relativistic cosmology. Reviews of modern Physics 1933, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.G. On Milne’s Theory of World-Structure. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1937, 2, 90–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubble, E. A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1929, 15, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kragh, H. Is the universe expanding? Fritz Zwicky and early tired-light hypotheses. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 2017, 20, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, R. Relativity, thermodynamics, and cosmology. Clarendon, 1934.

- Tolman, R.C. On the estimation of distances in a curved universe with a non-static line element. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1930, 16, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubin, L.M.; Sandage, A. The Tolman surface brightness test for the reality of the expansion. IV. A measurement of the Tolman signal and the luminosity evolution of early-type galaxies. The Astronomical Journal 2001, 122, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandage, A. The Tolman surface brightness test for the reality of the expansion. V. Provenance of the test and a new representation of the data for three remote Hubble space telescope galaxy clusters. The Astronomical Journal 2010, 139, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, E.J. Evidence for a Non-Expanding Universe: Surface Brightness Data From HUDF. AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics, 2006, Vol. 822, pp. 60–74.

- Crawford, D.F. Observational evidence favors a static universe. arXiv preprint arXiv:1009.0953, arXiv:1009.0953 2010.

- Brynjolfsson, A. Surface brightness in plasma-redshift cosmology. arXiv preprint arXiv:astro-ph/0605599.

- Wilson, O. supernovae clock. The Astrophysical Journal 1939, 90, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber, G.; Groom, D.; Kim, A.; Aldering, G.; Astier, P.; Conley, A.; Deustua, S.; Ellis, R.; Fabbro, S.; Fruchter, A.; others. Timescale stretch parameterization of type Ia supernova B-band light curves. The Astrophysical Journal 2001, 558, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Corredoira, M. Fundamental Ideas in Cosmology: Scientific, philosophical and sociological critical perspectives; IoP Publishing, 2022.

- Hogg, D.W. Distance measures in cosmology. arXiv preprint arXiv:astro-ph/9905116.

- Moffat, J.W. Superluminary universe: A Possible solution to the initial value problem in cosmology. International Journal of Modern Physics D 1993, 2, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.; Magueijo, J. Time varying speed of light as a solution to cosmological puzzles. Physical Review D 1999, 59, 043516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, R.H. Gravitation without a principle of equivalence. Reviews of Modern Physics 1957, 29, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Royen, J. General Relativity: Varying Speed of Light from the Friedmann Equation. Journal of Cosmology 2021, 27, 15389–15406. [Google Scholar]

- Pipino, G. Variable Speed of Light with Time and General Relativity. Journal of High Energy Physics, Gravitation and Cosmology 2021, 7, 742–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, P.I. On the redward shift of spectral lines of nebulae. Physical Review 1935, 47, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).