1. Introduction

Bauxite residue, also known as red mud, is a byproduct of processing bauxite ore to produce alumina (Al2O3) through the Bayer process. This process involves heating bauxite in caustic soda (NaOH) at high temperature and pressure to form sodium aluminate. The residual material consists of about 4% liquor and 55% solid, ranging from 0.3 to 2.5 tonnes per tonne of alumina produced. Worldwide, approximately 120 millions of tons of bauxite residue are generated annually. Primary concerns in bauxite residue disposal include salinity, alkalinity, physical properties, and the presence of potentially toxic metals, posing significant environmental hazards. Therefore, the need to find ways to repurpose this waste and rehabilitate existing disposal sites is crucial.

The pH of the bauxite residue is between 10 and 13, a consequence of the caustic soda used in the Bayer process. The elevated salinity and sodicity induce toxic effects on plants and animals. Consequently, if revegetation is contemplated, the neutralization of bauxite residue becomes a priority. Rai et al. [

1] have explored various techniques, including the use of mineral acids, acidic waste (pickling liquor waste), superphosphate and gypsum, coal dust, CO2, silicate material, and seawater. Concerning their physical properties, bauxite residues exhibit low structural stability, rendering spreading deposits impermeable to rainwater percolation and hindering the development of vegetation root system. This is attributed to their silty nature and the salinity that impedes particle aggregation [

2]. In terms of mineralogical and chemical composition, bauxite residue varies across refinery plant but typically contains elevated concentrations of iron oxides (goethite, hematite, magnetite) in addition to un-dissolved alumina, and titanium oxide (anatase, rutile, perovskite). The major elements present in bauxite residue are Fe (20-45%), Ti (5-30%), Al (10-22%), Si (20-45%), and to a lesser extent Mn, Ca, Na, Cr, V, La, Sc, Y [

3]. Other elements are present at trace level, such as As, Be, Cd, Cu, Gl, Pb, Hg, Ni, Th, U, V, Zn, Ce, Nd, Sm. Some of these elements, like Sc and REE rare earths are recoverable [

4]. Non-metallic and non-metaloïd elements such as P and S may also be present in bauxite residue [

5]. Regarding radioelements, bauxite residue typically exhibits radioactive activity around 0.03 to 0.06 Bq g-1 due to 238U and 0.03 to 0.76 Bq g

−1 due to 232Th, both originating from the bauxite ore [

5]. This may limit the use of bauxite residu as building material [

6] or can be a source of danger in red mud dams [

7].

Due to the substantial volumes of bauxite residue and the adverse environmental impact associated to simple disposal methods like ocean dumping, landfilling, or settling ponds, numerous efforts have been undertaken to explore environmentally sustainable and economically viable approaches for bauxite residue management. Reuse applications, including building materials, recovery of valuable chemicals, cement production, road and levee construction, and environmental remediation [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] have been proposed, potentially consuming more than 500.000 t y

−1 [

13]. While this volume is substantial, it falls short of addressing the entirety of residues generated annually, necessitating consideration of alternative disposal methods. Landspreading has historically been a cost-effective and widely employed disposal technique. However, a crucial condition for its application is to facilitate the successful revegetation of the spreading area [

14,

15], thereby mitigating the risk of wind and water erosion on the surface. Various techniques have been implemented to enhance revegetation, primarily focusing on reducing pH and improving the physical properties of the residue, resulting in a modified bauxite residue (MBR). Common practices include washing with a filter press [

16], gypsum amendment [

17,

18,

19], or the addition of coarse materials such as sand [

20]. Even in areas where MBR deposits have been successfully revegetated through spreading, concerns persist regarding major elements and particularly toxic trace elements such as Cd, necessitating ongoing monitoring of leaching by groundwater.

Bauxite residue exhibits the capability to immobilize elements that may be mobile in aqueous solutions, encompassing both cationic and anionic species. Examples include phosphate from used water [

21] and potentially toxic metal cations in applications such as remediating acid mine tailings (AMT) or addressing acid mine drainage (AMD). Acid mine drainage occurs when sulfides, particularly pyrite and pyrrhotite in AMT, oxidize upon exposure to air and water, generating sulfated acidic solutions with a pH below 6. Conventionally, alkaline chemicals like CaO or calcite are introduced to neutralize AMD and induce hydroxide precipitation [

22]. Interestingly, bauxite residue can serve the same purpose and can also be mixed with AMT to inert it and foster revegetation.

In a prior study, we explored this process by examining the long-term behavior of a mixture comprising Modified Bauxite Residue (MBR) and Acid Mine Tailings (AMT) [

23]. In the current study, our focus is directed towards delineating the impact of the design of MBR spreading on the emission of potentially toxic elements: with or without revegetation, with a sand or a soil capping. We also characterized the emissions from a previously utilized MBR (UMBR), which had been employed in the depollution of Acid Mine Drainage (AMD). Utilizing nine lysimeters established for a duration of five years, we systematically examined the emission of sulfate and 12 potentially toxic elements in aqueous solutions from both MBR and UMBR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modified Bauxite Residue (MBR) and Used Modified Bauxite Residue (UMBR)

Bauxaline

® from ALTEO is bauxite residue washed and partially dried in a filter press in order to form of a shovelable material. The MBR used in the present study is Bauxaline

® treated with atmospheric CO

2 with 5% gypsum (hydrated calcium sulfate) in order to precipitate the alkalinity of soda into calcium carbonate, at a pH of 8.5. Soluble sodium sulfate remained. The MBR has a variable composition depending on the ore used in the Al

2O

3 production process. The

Table 1 gives the usual range of major and potentially toxic trace elements in the Bauxaline and the values for the MBR used in this study, which are for most metal and metalloids above the limits for admission to Inert waste storage facility (IWSF) or Non-hazardous waste storage facility (NHWSF) [

24]. The UMBR used in the present study is the MBR described above which was used to bind contaminants from acid mine drainage rich in As, Pb, Cd, Cr and Zn [

25].

The treatment of acid mine drainage – AMD - (pH 2.2, As 57 mg L−1, Cd 1.05 mg L−1, Zn 117 mg L−1) of Saint-Félix was carried out in two pilot trials of 50 kg granulated MBR (not presented here) at the rate of 30 L of AMD per kg of granulated MBR with a residence time of one hour. The depollution yield was 99.89% and 99.63% for the two trials. The loading of As, Cd and Zn measured by difference between the incoming and outgoing effluents was 1710, 38 and 4100 mg kg−1 MBR, respectively.

The objective of the lysimeter tests was to simulate a loaded MBR storage scenario (called used MBR: UMBR), in particular on the mining sites concerned, and to determine with what requirements this storage could be carried out (cover, drainage, etc.).

The MBR were not leached before or during placement, whereas the UMBR was partially leached by the acid mine drainage treatment.

2.2. Lysimeter Conception and Management

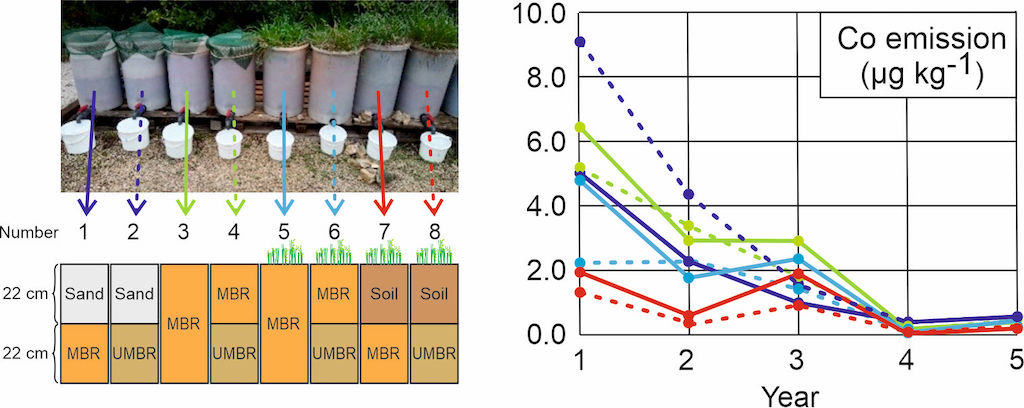

Eight 40-L lysimeters were employed in this study, with varying content including MBR, UMBR, silicate sand, and soil, with a total thickness around 44 cm, as depicted in

Figure 1. Lysimeters #1 to #4 remained unvegetated, while lysimeters #5 to #8 underwent a revegetation process. Additionally, a larger 700-L lysimeter (#16) filled with 66 cm (1087 kg) of MBR was subjected to the same revegetation process, aiming to more accurately simulate real MBR storage conditions. This last lysimeter was started a year after the others. To ensure technical and financial feasibility, we prioritized the collection of dense time series data over an extended period, without repetition. Repetition would have necessitated either sparse time series data or a shorter experimental duration. In this context, the consistency in the evolution of various variables over time ensures the validity of the results. Additionally, the comparison of the nine lysimeters further reinforces the robustness of the findings.

The revegetalisation was made with Dactylis glomerata (orchardgrass) and Onobrychis sativa (common sainfoin). The revegetation procedure encompassed the introduction of compost (1% w/w in the top 20 cm layer), N-P-K fertilizer (at an agronomic dose), forest topsoil (1‰ w/w in the upper 22 cm layer), and seeds (agglomerated cocksfoot and common sainfoin). To address trace element requirements, a supplementary supply of soluble manganese was administered at an agronomic dose during the second and third years. Additionally, an annual application of N-P-K fertilizer, matching the initial dose, was conducted. Lysimeters #5, #6, and #16 underwent an initial watering prior to seeding to facilitate seedbed desalination.

During the summer months, a moderate watering was conducted to sustain plants in a vegetative state. This approach facilitated their swift recovery once rainfall resumed, all while preventing runoff. It is noteworthy that the unvegetated lysimeters underwent the same watering regimen.

In year 4 and 5 of the study, a supplement of fresh forest plant litter was introduced onto the topsoil. Lysimeters #5 to #8 received 5 g each, while lysimeter #16 received 15 g. This deliberate addition aimed to foster the colonization of decomposing organisms, as organic matter had accumulated on the surface, forming a cohesive mat.

Notably, the revegetation efforts proved successful for each lysimeter where it was implemented.

2.3. Sample Collection and Analysis

After each rainfall event, drainage samples were systematically collected, acidified with ultrapure acid, and then stored at 2°C. Each year, an annual composite sample was created, proportional to the annual drained volumes of the raw samples. For each sample, measurements of pH, electrical conductivity, and redox potential were recorded. Analyses were performed using ICP-MS at the Eurofins certified laboratory.

Each sample volume was quantified by weighing, allowing for the calculation of the liquid/solid (L/S) ratio in liters per kilogram of residue. This ratio represents the volume of the leachate sample divided by the mass of the residue. Concentration data were expressed in mg L−1, while quantity data were expressed in mg kg−1 by multiplying the concentration by the sample L/S ratio. Cumulative quantities were calculated by summing the quantities of each sample.

4. Conclusion

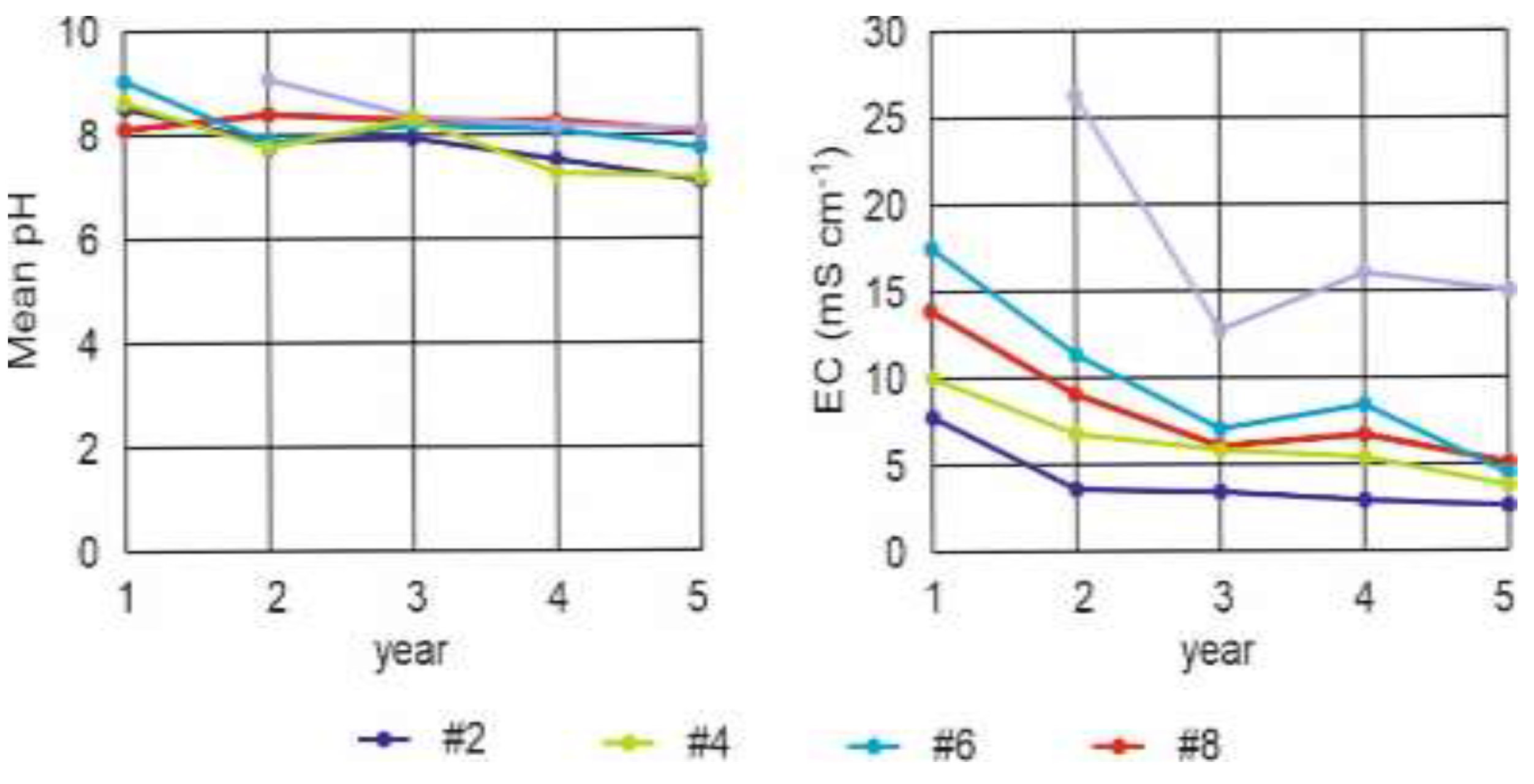

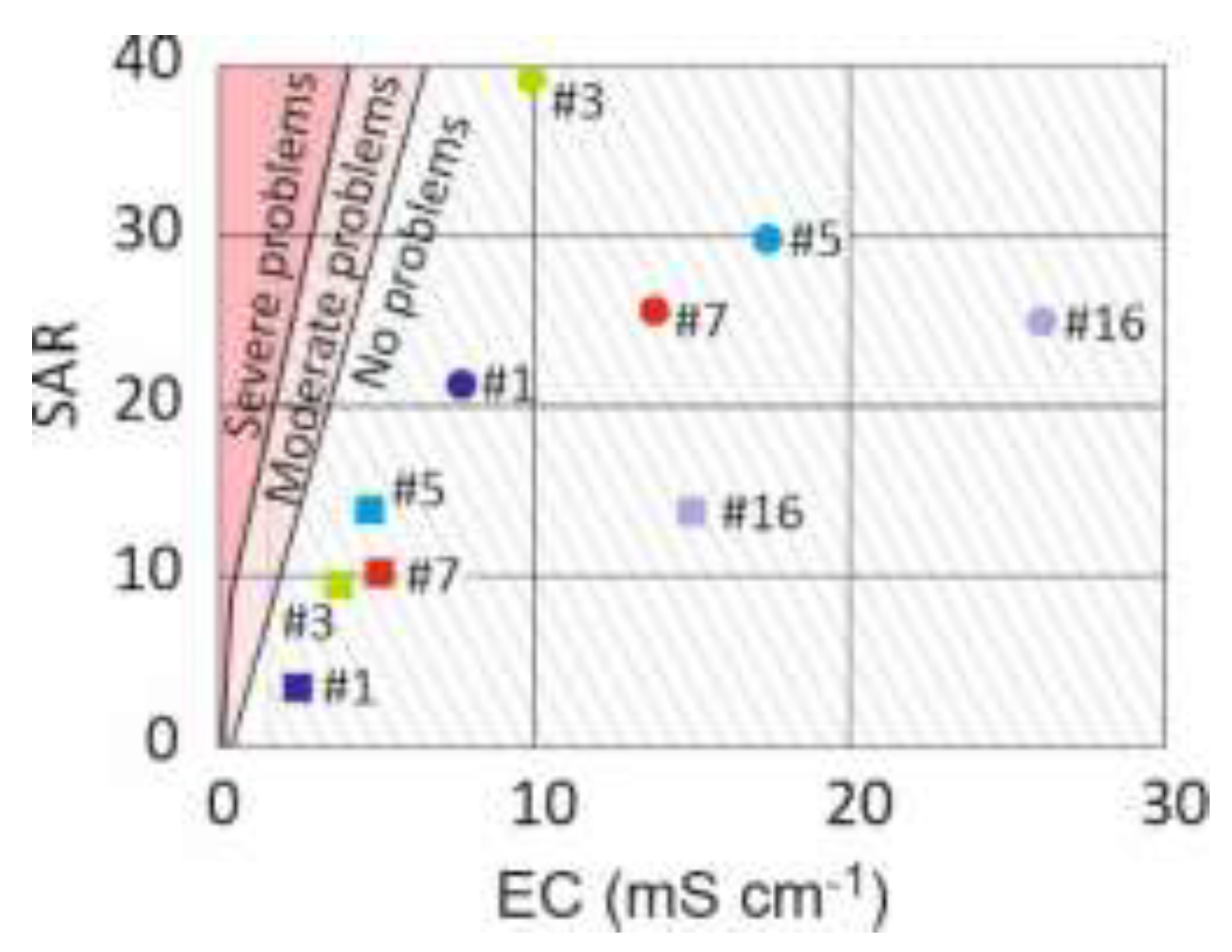

Over the course of the 5-year experiment and across all configurations tested – raw, sand capping, soil capping, and revegetation – the pH of the leachates stabilized between 7 and 8, and their salinity gradually decreased. Although the salinity remained significant in the final year, ranging from 3 to 5 mS cm⁻1, the SAR stayed well below the values that could cause clay dispersion and material clogging. Therefore, in all cases, the material remained suitable for the growth of plants compatible with the observed salinity.

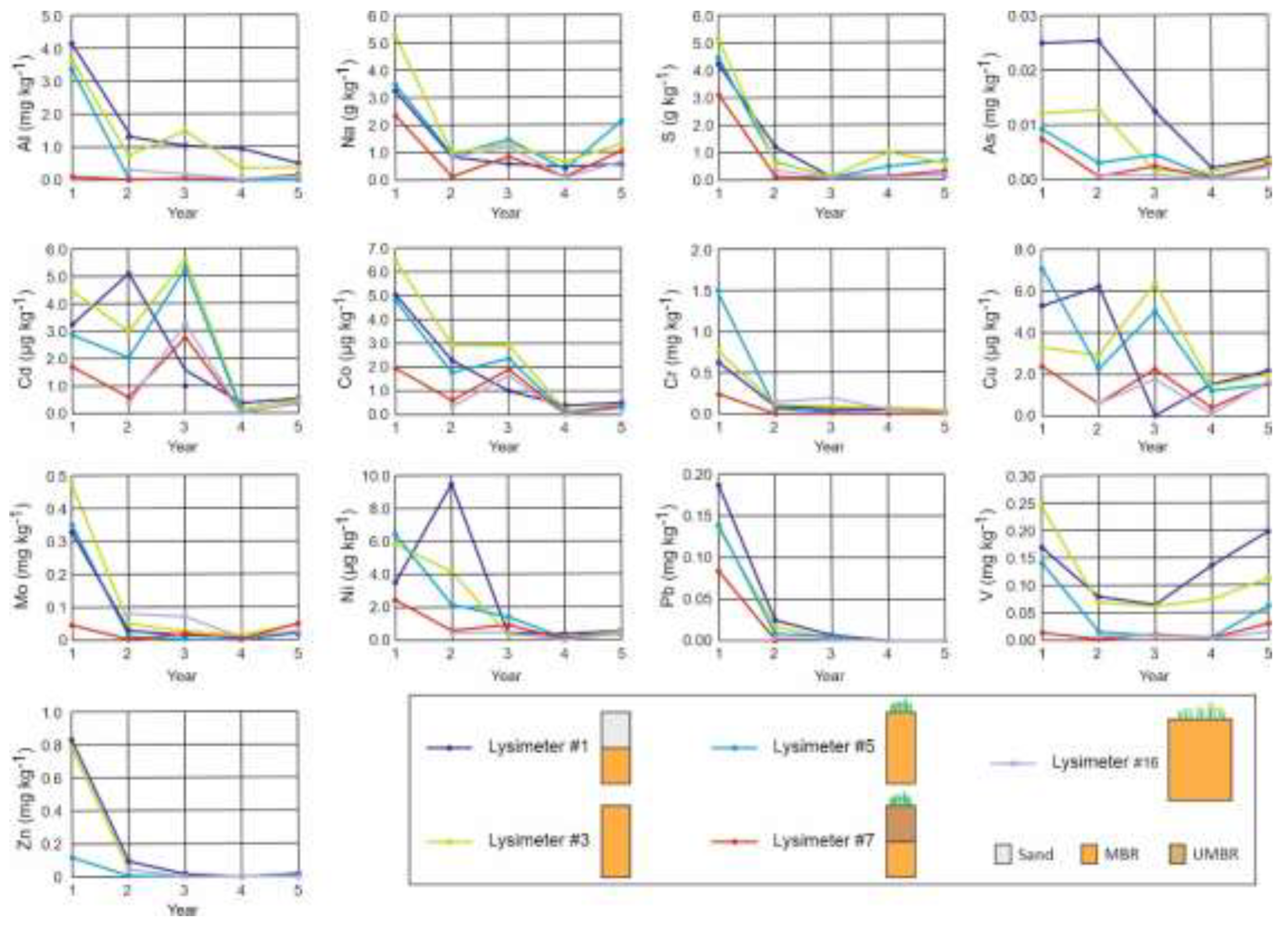

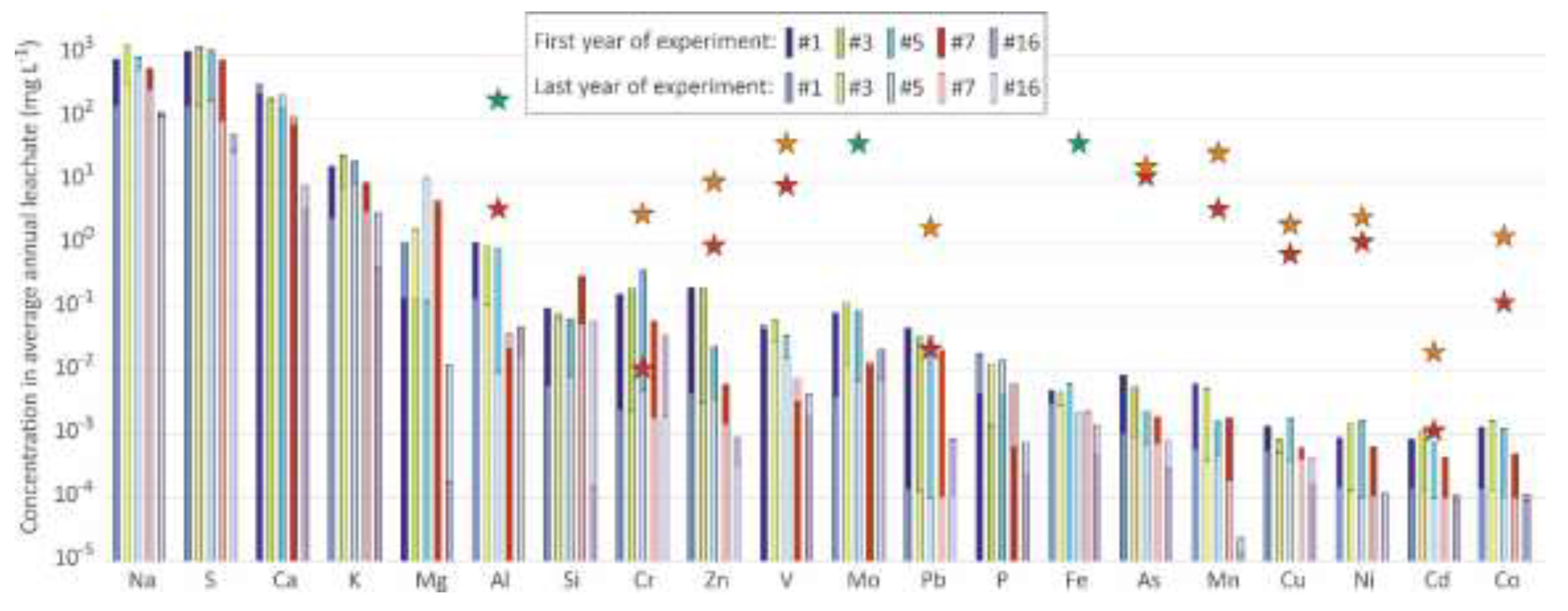

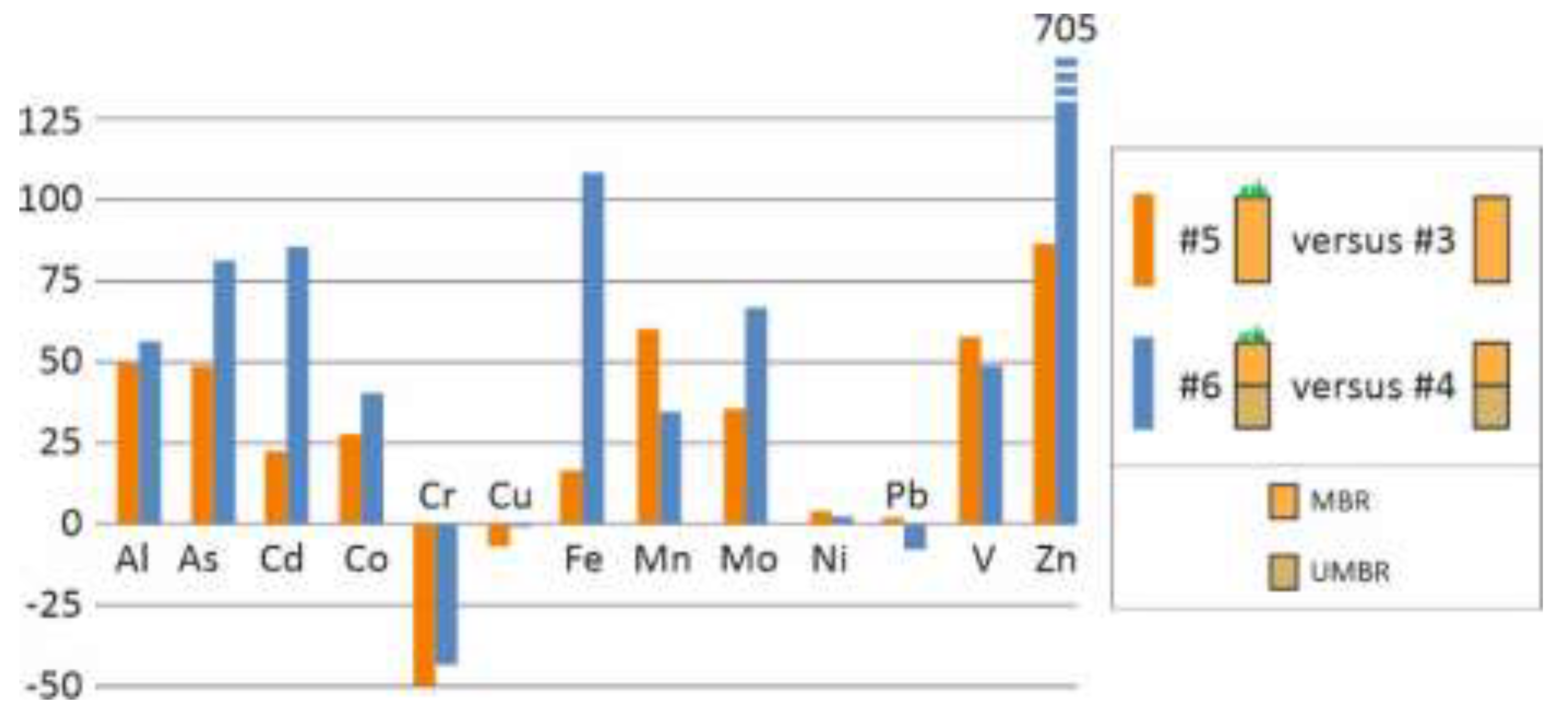

Except for V, the emission of potentially toxic elements from the modified bauxite residue (MBR), whether or not it was used to remediate acid mine drainage, rapidly decreased after the first year, reaching low levels. Except for Cr in the first year, the concentrations in the leachates always remained below the LD50 values and reached levels at least one order of magnitude lower than the LD50 by the end of the experiment. Among the different designs studied, sand capping gave less satisfactory results. Revegetation and soil capping also increased emissions, but this increase became insignificant given the low emission levels observed at the end of the experiment.

In conclusion, the spreading of MBR and its revegetation, which prevents dust dispersion, appears to be an environmentally suitable solution for managing bauxite residues like those studied here. However, it is essential to maintain a pH around 7, as acidification of the material below 6.5 could increase the mobility of most potentially toxic elements. Although progressive acidification over time is unlikely in the Mediterranean environment with low deep drainage, this possibility must be monitored in case of spreading in regions with high rainfall.

Figure 1.

Lysimeters experimental setup. Left: 40-L lysimeters, view and diagram of filling and revegetation; center and right: 700-L lysimeter, shown from the side and from above, respectively.

Figure 1.

Lysimeters experimental setup. Left: 40-L lysimeters, view and diagram of filling and revegetation; center and right: 700-L lysimeter, shown from the side and from above, respectively.

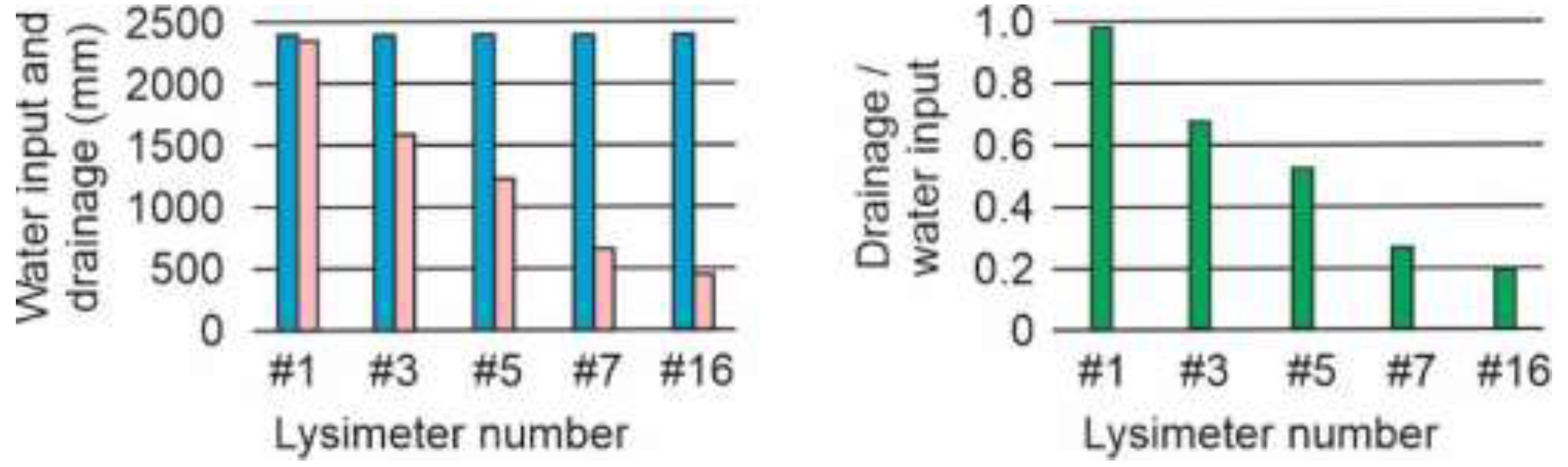

Figure 2.

Water input (rainfall + watering ) (blue columns), drainage (pink columns) and drainage/water input ratio (green columns) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5 and #16.

Figure 2.

Water input (rainfall + watering ) (blue columns), drainage (pink columns) and drainage/water input ratio (green columns) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5 and #16.

Figure 3.

pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5, #7 and #16.

Figure 3.

pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5, #7 and #16.

Figure 4.

Variation of emission by leachates over time of some selected elements (Al, Na, S, As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, V, Zn) in mg kg

−1 of MBR. Sketch of lysimeters, see

Figure 1.

Figure 4.

Variation of emission by leachates over time of some selected elements (Al, Na, S, As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, V, Zn) in mg kg

−1 of MBR. Sketch of lysimeters, see

Figure 1.

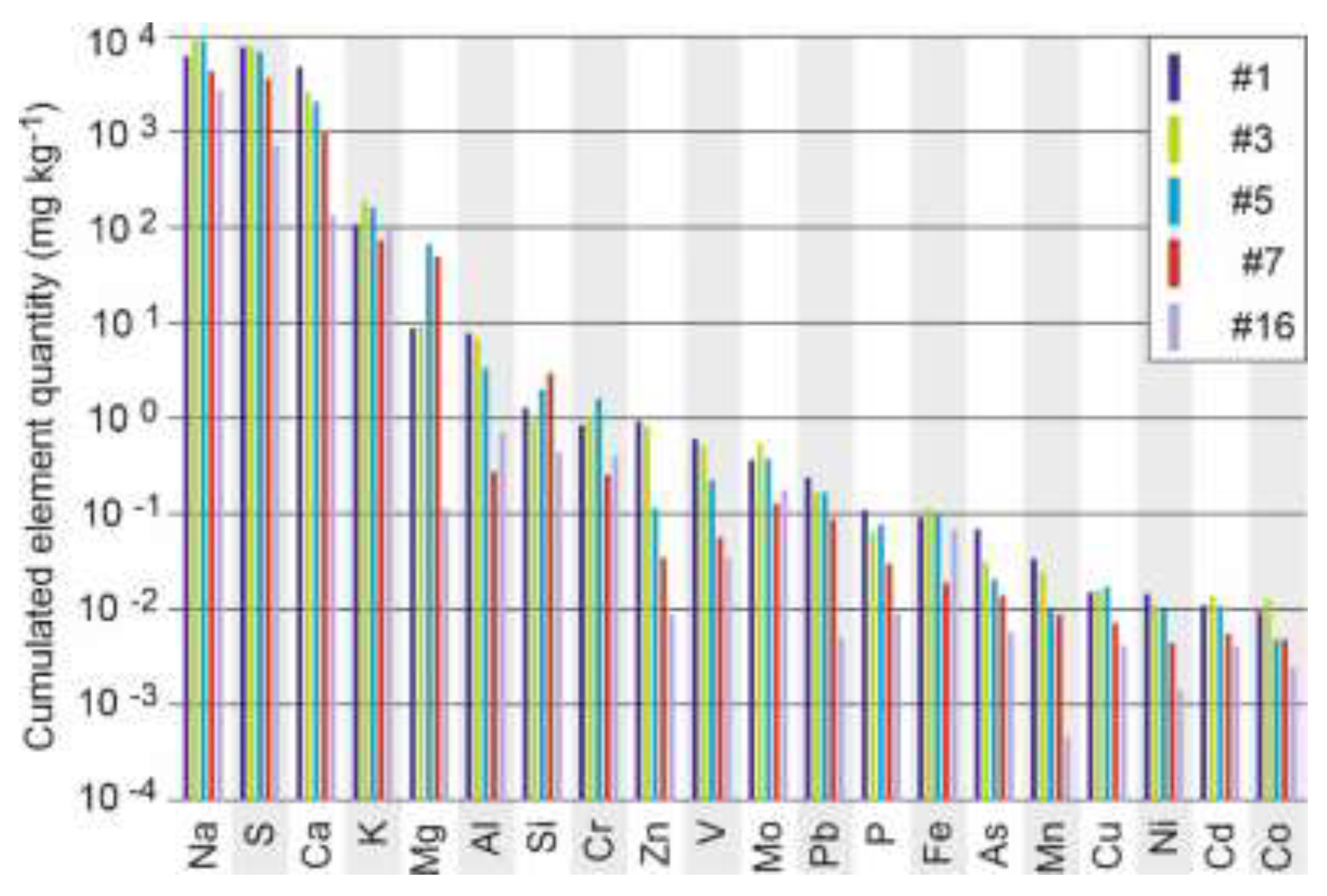

Figure 5.

Cumulated element quantity (mg kg−1 of MBR) emitted by the lysimeters during the 5-years experiment for #1, #3, #5, #7 and the 4-years experiment for #16.

Figure 5.

Cumulated element quantity (mg kg−1 of MBR) emitted by the lysimeters during the 5-years experiment for #1, #3, #5, #7 and the 4-years experiment for #16.

Figure 6.

Concentrations in average annual leachate for the first year and the final year of the experiment. Stars indicate the LD50 concentrations for Hyalella azteca in soft freshwater (hardness 18, red stars) and hard freshwater (hardness 124, orange stars); green stars indicates that the LD50 concentration is over the star value [

28].

Figure 6.

Concentrations in average annual leachate for the first year and the final year of the experiment. Stars indicate the LD50 concentrations for Hyalella azteca in soft freshwater (hardness 18, red stars) and hard freshwater (hardness 124, orange stars); green stars indicates that the LD50 concentration is over the star value [

28].

Figure 7.

SAR and electrical conductivity (EC) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5, #7 and #16. Circles and squares give first and final year values, respectively. Areas related to clay dispersion problems were drawn after Hanson et al. [

31]. Hatched area represents high and very high salinity with regard to plant growth [

32].

Figure 7.

SAR and electrical conductivity (EC) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5, #7 and #16. Circles and squares give first and final year values, respectively. Areas related to clay dispersion problems were drawn after Hanson et al. [

31]. Hatched area represents high and very high salinity with regard to plant growth [

32].

Figure 8.

Emission from a vegetated lysimeter (#5 and #6) as a % of the corresponding non-vegetated lysimeter (#3 and #4, respectively). Cumulative emissions during the 5 years of experimentation.

Figure 8.

Emission from a vegetated lysimeter (#5 and #6) as a % of the corresponding non-vegetated lysimeter (#3 and #4, respectively). Cumulative emissions during the 5 years of experimentation.

Figure 9.

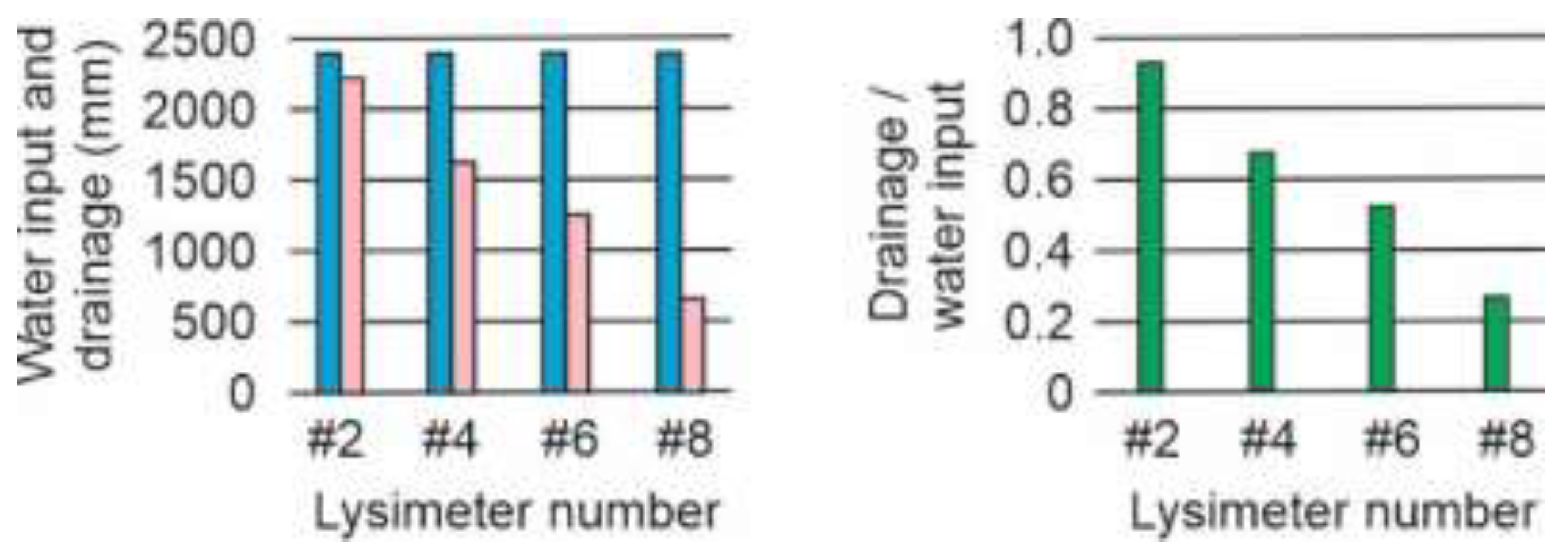

Water input (rainfall + watering ) (blue columns), drainage (pink columns) and drainage/water input ratio (green columns) of lysimeters #2, #4, #6 and #8.

Figure 9.

Water input (rainfall + watering ) (blue columns), drainage (pink columns) and drainage/water input ratio (green columns) of lysimeters #2, #4, #6 and #8.

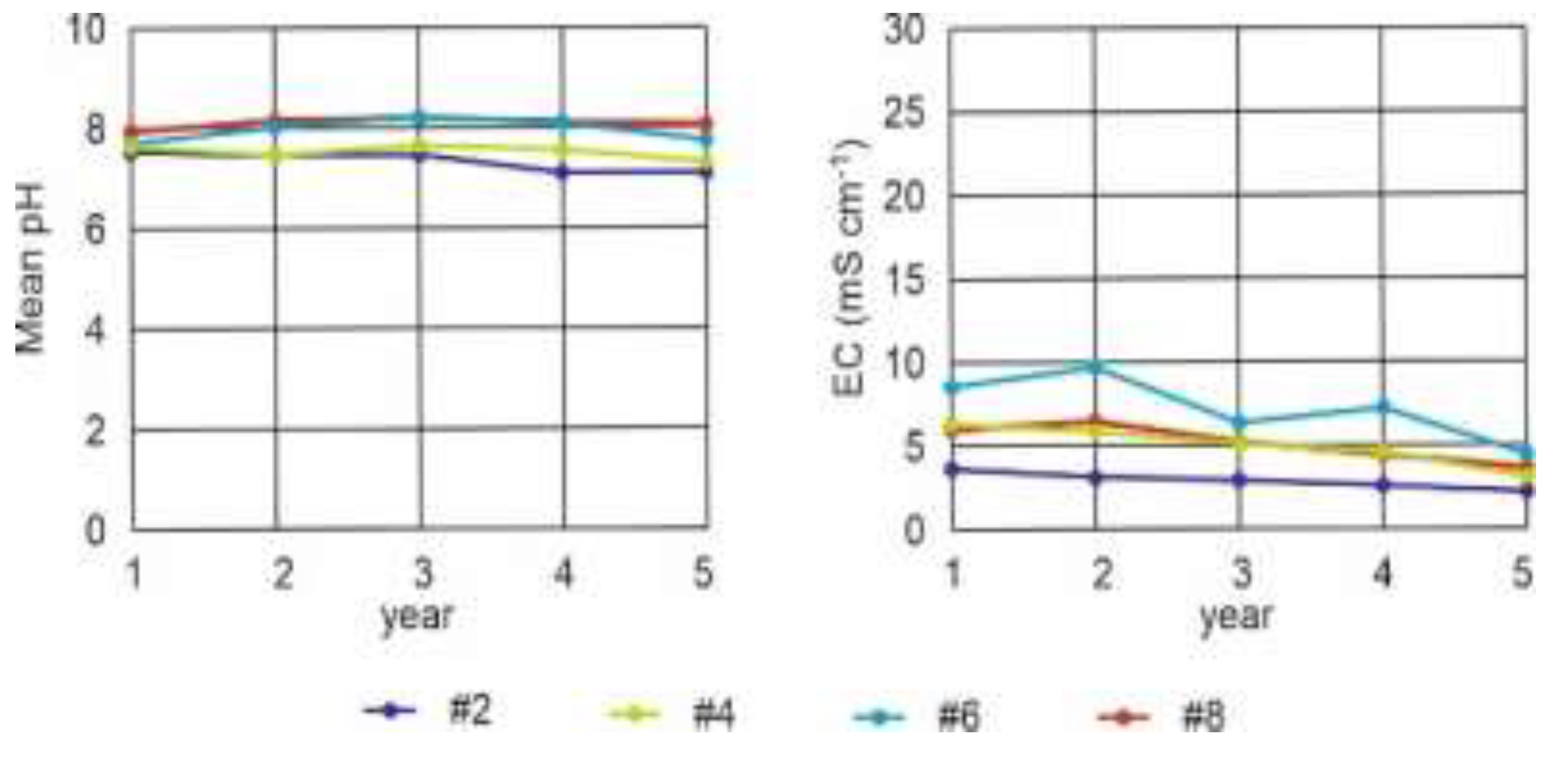

Figure 10.

pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of lysimeters #2, #4, #6 and #8.

Figure 10.

pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of lysimeters #2, #4, #6 and #8.

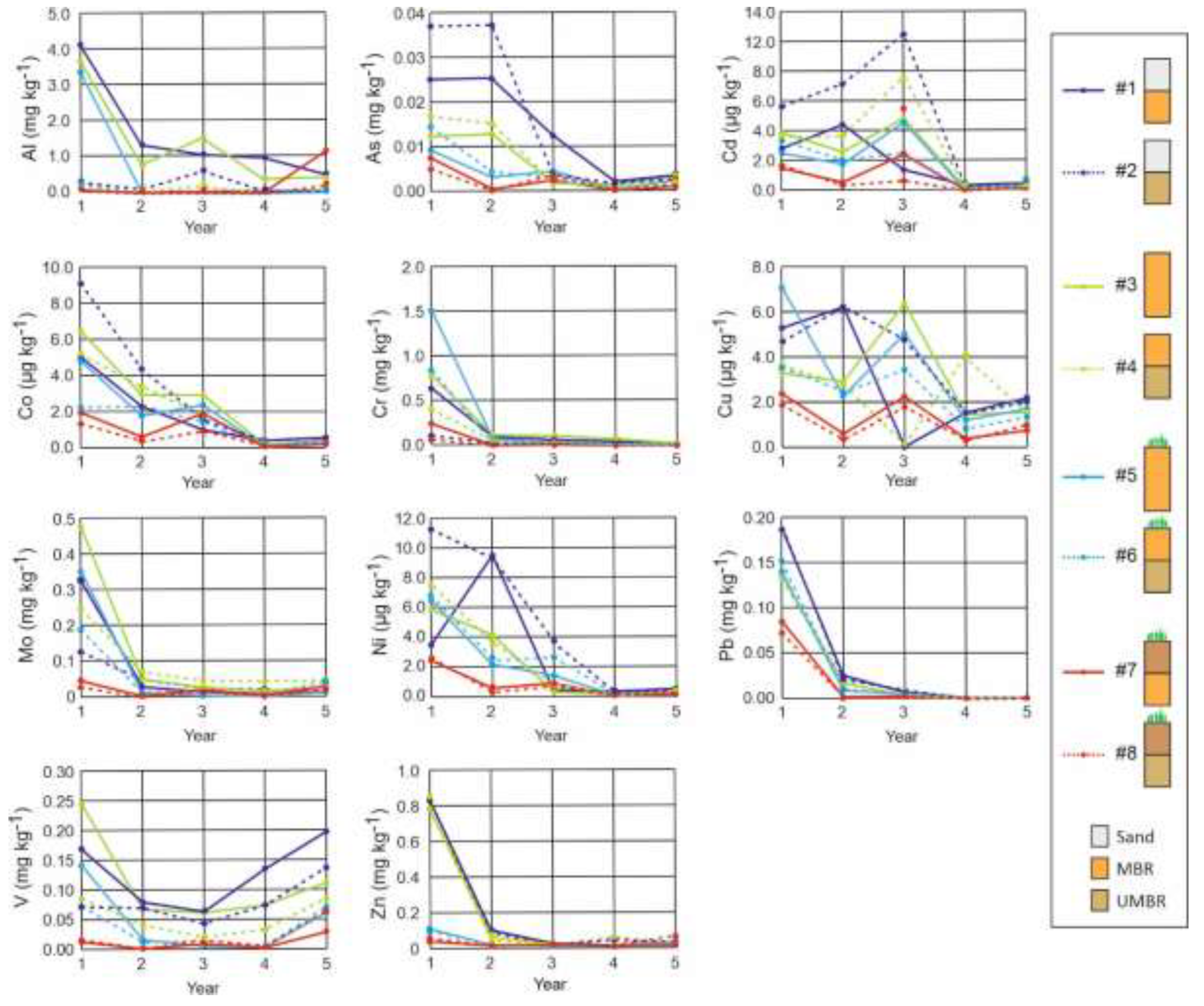

Figure 11.

Variation of emission by leachates over time of potentially toxic elements (Al, As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, V, Zn) in mg kg

−1 of (MBR+UMBR). Sketch of lysimeters, see

Figure 1.

Figure 11.

Variation of emission by leachates over time of potentially toxic elements (Al, As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, V, Zn) in mg kg

−1 of (MBR+UMBR). Sketch of lysimeters, see

Figure 1.

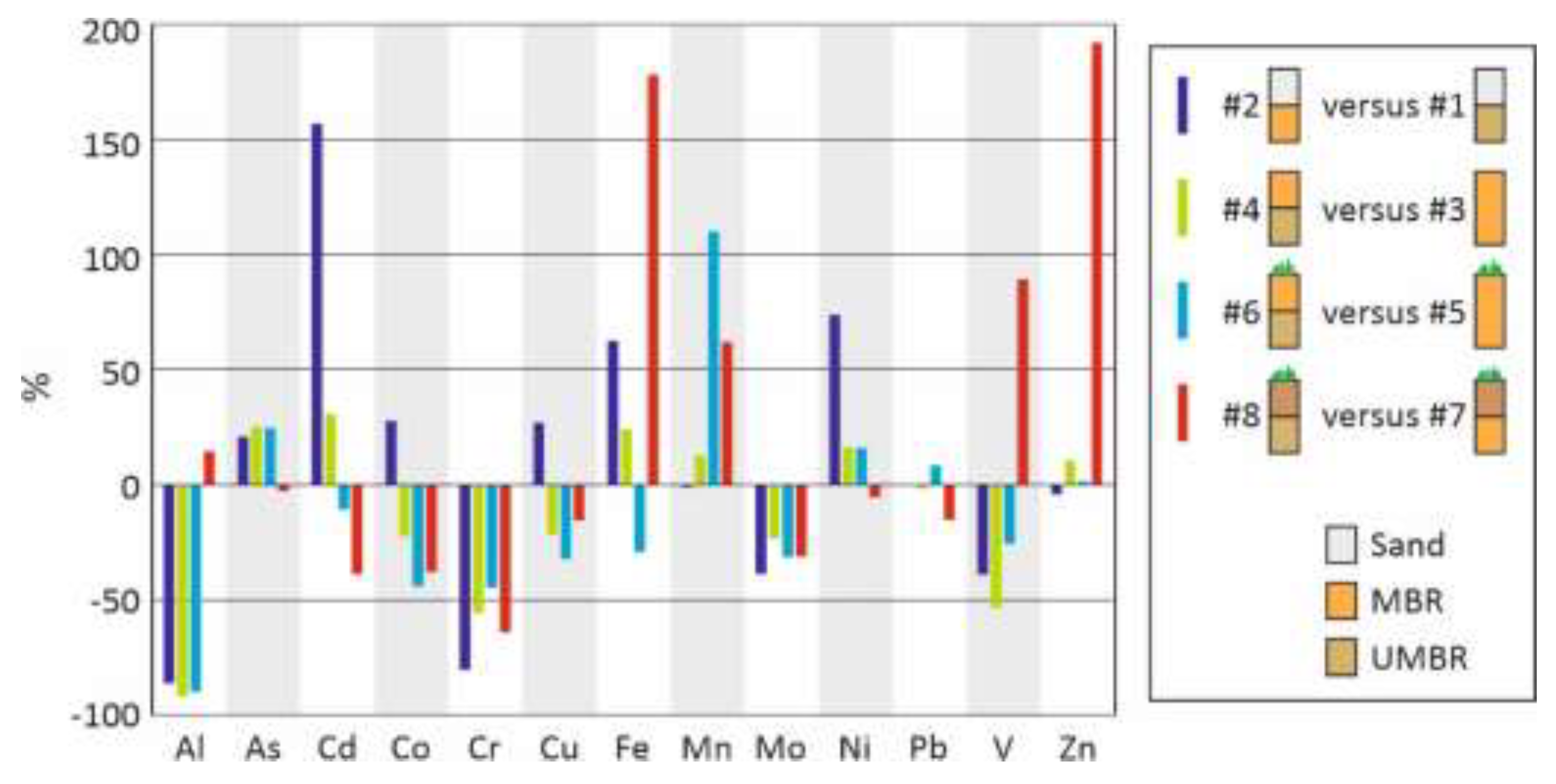

Figure 12.

Emission from lysimeter with UMBR as a % of the corresponding lysimeter without UMBR. Cumulative emissions during the 5 years of experimentation.

Figure 12.

Emission from lysimeter with UMBR as a % of the corresponding lysimeter without UMBR. Cumulative emissions during the 5 years of experimentation.

Table 1.

Usual range of major and potentially toxic elements in the Bauxaline® and composition of the Bauxaline® used in the present study. IWSF and NHWSF: concentration limits of leachable elements for admission to Inert waste storage facility and Non-hazardous waste storage facility, respectively.

Table 1.

Usual range of major and potentially toxic elements in the Bauxaline® and composition of the Bauxaline® used in the present study. IWSF and NHWSF: concentration limits of leachable elements for admission to Inert waste storage facility and Non-hazardous waste storage facility, respectively.

| |

Major elements (%) |

|

Trace elements (ppm) |

|

|

| |

Usual range |

Present study |

|

|

Usual range |

Present study |

IWSF |

NHWSF |

| Al |

1.6 – 8.1 |

7.9 |

|

As |

10 - 200 |

18 |

0.5 |

2 |

| Ca |

1.4 – 4.8 |

4.3 |

|

Cd |

<0.5 - 10 |

0.8 |

0.04 |

1 |

| Fe |

21.0 – 38.0 |

32.2 |

|

Co |

1 – 75 |

35 |

|

|

| Na |

1.5 – 3.0 |

3.0 |

|

Cr |

200 - 2000 |

1638 |

0.5 |

10 |

| Si |

0.9 – 3.9 |

3.3 |

|

Hg |

<1.5 – 2 |

0.2 |

|

|

| Ti |

1.8 – 5.4 |

6.0 |

|

Ni |

5 – 50 |

18 |

0.4 |

10 |

| |

|

|

|

Pb |

10 - 100 |

42 |

0.5 |

10 |

| |

|

|

|

Se |

<1.5 - 50 |

<6 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

| |

|

|

|

V |

200 - 1500 |

968 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Zn |

<20 - 500 |

115 |

4 |

50 |

Table 2.

Cumulated L/S ratio (L kg−1 of MBR) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5, #7 and #16.

Table 2.

Cumulated L/S ratio (L kg−1 of MBR) of lysimeters #1, #3, #5, #7 and #16.

| |

#1 |

#3 |

#5 |

#7 |

#16 |

| Year 1 |

2.68 |

1.16 |

0.88 |

1.02 |

- |

| Year 1 to 2 |

3.85 |

1.45 |

1.02 |

1.08 |

0.09 |

| Year 1 to 3 |

5.12 |

1.85 |

1.33 |

1.60 |

0.26 |

| Year 1 to 4 |

6.67 |

2.22 |

1.46 |

1.72 |

0.30 |

| Year 1 to 5 |

8.89 |

2.99 |

2.31 |

2.48 |

0.46 |

Table 3.

Cumulated L/S ratio (L kg−1 of MBR) of lysimeters #2, #4, #6 and #8.

Table 3.

Cumulated L/S ratio (L kg−1 of MBR) of lysimeters #2, #4, #6 and #8.

| |

#2 |

#4 |

#6 |

#8 |

| Year 1 |

2.55 |

2.39 |

2.20 |

0.85 |

| Year 1 to 2 |

3.68 |

2.99 |

2.53 |

0.89 |

| Year 1 to 3 |

4.95 |

3.74 |

3.19 |

1.40 |

| Year 1 to 4 |

6.38 |

4.55 |

3.37 |

1.51 |

| Year 1 to 5 |

8.39 |

6.15 |

4.76 |

2.54 |