Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

25 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The study of hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication in cell culture is mainly based on cloned viral isolates requiring adaptation for efficient replication in Huh7 hepatoma cells. The analysis of wild type (WT) isolates has been enabled by expression of SEC14L2 and by inhibitors targeting deleterious host factors. Here, we aimed at optimizing cell culture models to allow infection with HCV from patient sera. We used Huh7-Lunet cells ectopically expressing SEC14L2, CD81 and a GFP reporter with nuclear translocation upon cleavage by the HCV protease to study HCV replication, combined with a drug-based regimen for stimulation of non-modified wildtype isolates. RT-qPCR based quantification of HCV infections using patient sera suffered from high background in the daclatasvir treated controls. We therefore established an automated image analysis pipeline based on imaging of whole wells and iterative training of a machine-learning tool, using nuclear GFP localization as a readout for HCV infection. Upon visual validation of hits assigned by the automated image analysis the method revealed no background in daclatasvir treated samples. Thereby, infection events were found for 15 of 34 high titer HCV genotype (gt) 1b sera, revealing a significant correlation of serum titer and successful infection. We further show that transfection of viral RNA extracted from sera can be used in this model as well, albeit with so far limited efficiency. Overall, we generated a robust serum infection assay for gt1b isolates using semi-automated image analysis, which was superior to conventional RT-qPCR based quantification of viral genomes.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture:

Plasmids:

Patient Material and Ethics Statement:

Serum Infection:

Automated Image Analysis (AIA):

Pharmacological Inhibitors and Drugs:

Primers and Probes for RT-qPCR:

Production of Viral Particles:

Cell Viability Assay:

In Vitro Transcription, Electroporation and Luciferase Activity Assay:

RT-qPCR:

Electroporation of HCV RNA from Patient Serum:

Liposome-Based Transfection:

Ultracentrifugation:

TRIzol LS Extraction:

Statistical Analysis:

Results

Establishment of Optimal Conditions for Serum Infection

Establishment of a Quantitative, Semi-Automated Image Analysis Pipeline for Serum Infection

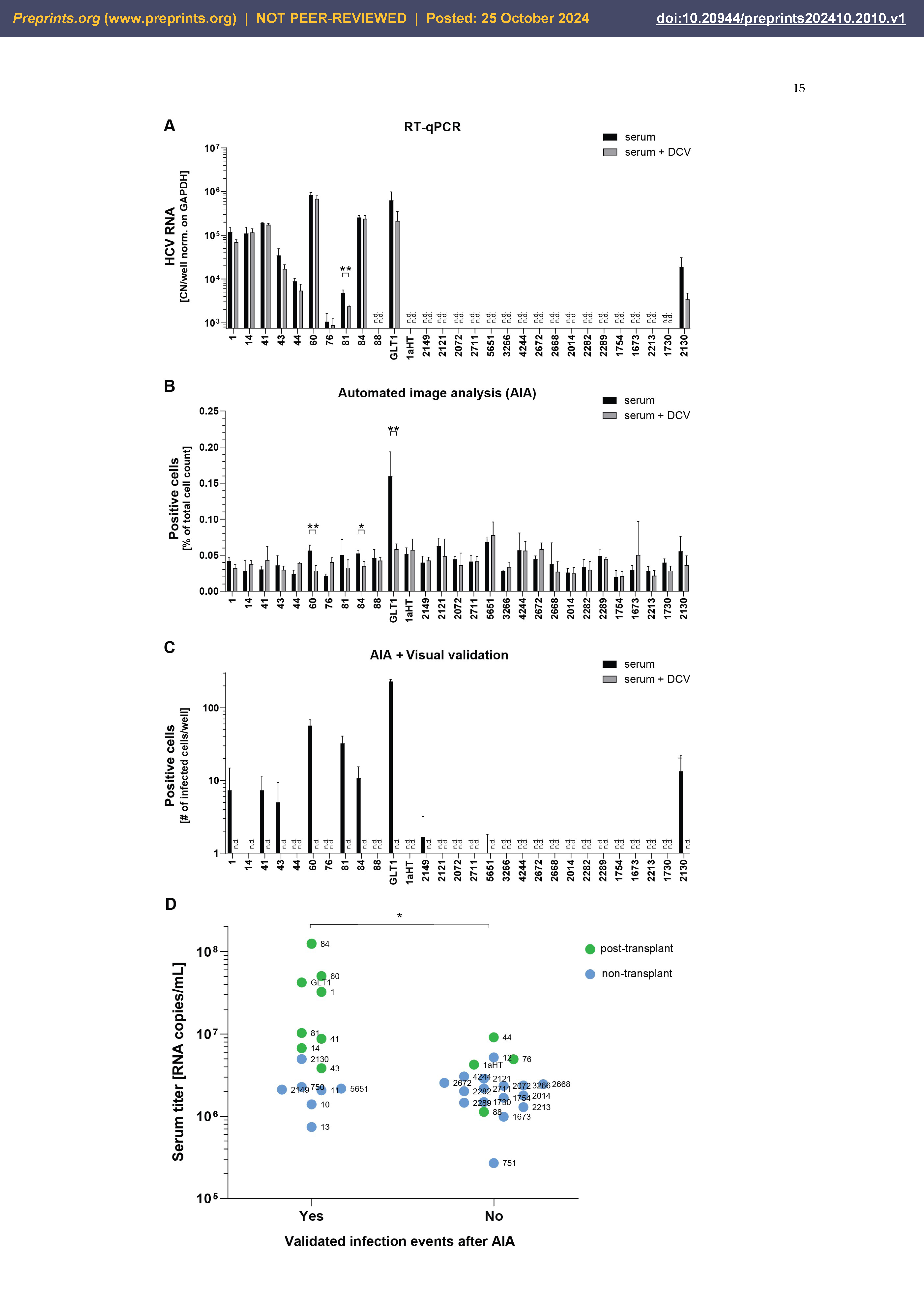

Semi-Automated Image Analysis Revealed More Consistent Results upon Serum Infection than RT-qPCR

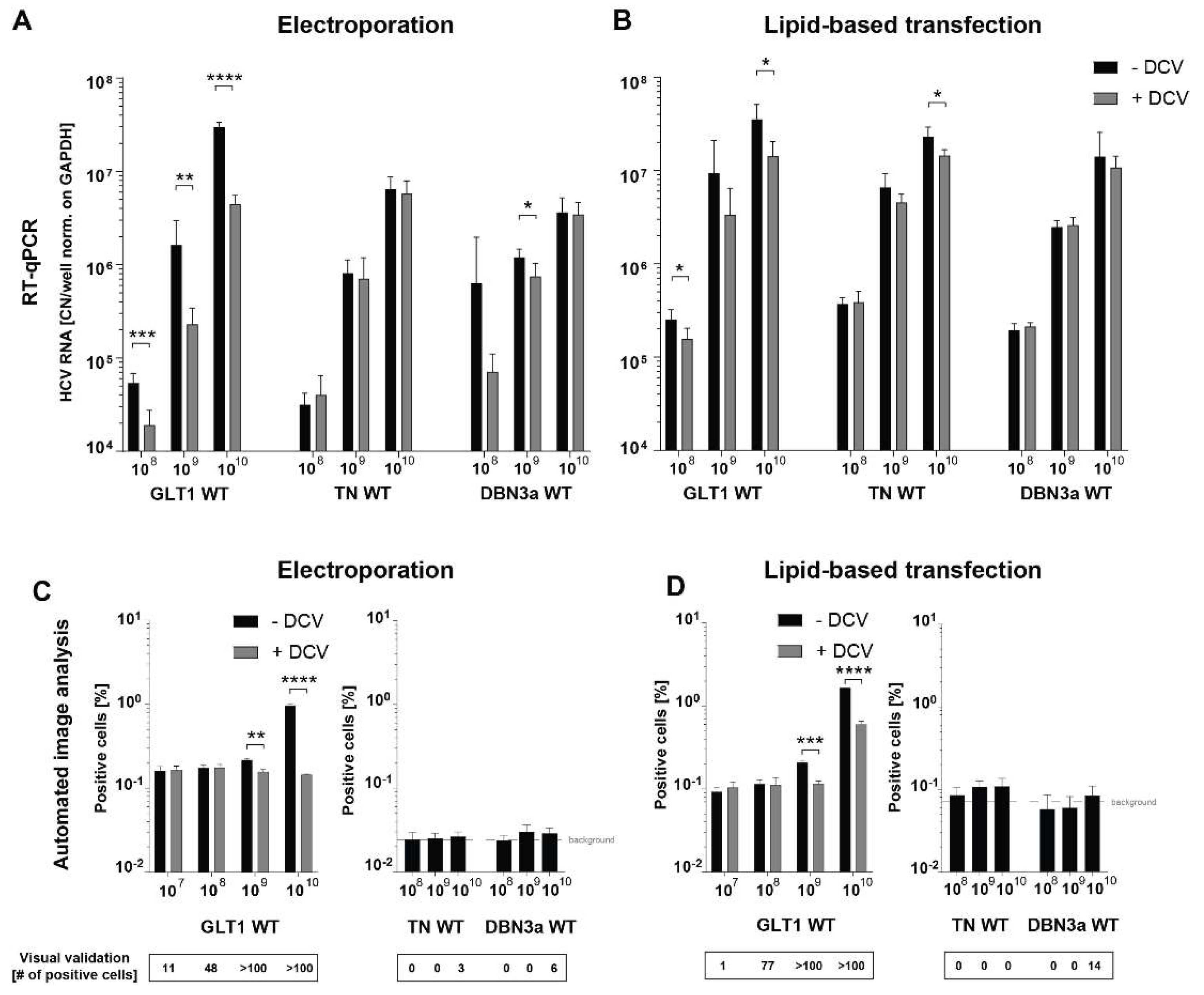

Establishment of Transfection-Based Delivery of Serum-Derived HCV WT RNA

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. 2013. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. [CrossRef]

- Thein H-H, Yi Q, Dore GJ. Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology 2008, 48, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. Journal of Hepatology 2014, 61, S58–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgia SM, Hedskog C, Parhy B. Identification of a Novel Hepatitis C Virus Genotype From Punjab, India: Expanding Classification of Hepatitis C Virus Into 8 Genotypes. J Infect Dis 2018, 218, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukh J, Miller RH, Purcell RH. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies and genotypes. Semin Liver Dis 1995, 15, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds P, Bukh J, Combet C. Consensus proposals for a unified system of nomenclature of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2005, 42, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martell M, Esteban JI, Quer J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) circulates as a population of different but closely related genomes: quasispecies nature of HCV genome distribution. J Virol 1992, 66, 3225–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin C, Zimmermann T, Berg T. [Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of hepatitis-C-virus (HCV) infection: the German guidelines on the management of HCV infection - AWMF-Register-No.: 021/012]. Z Gastroenterol 2018, 56, 756–838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bartenschlager R, Baumert TF, Bukh J. Critical challenges and emerging opportunities in hepatitis C virus research in an era of potent antiviral therapy: Considerations for scientists and funding agencies. Virus Research 2018, 248, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlotsky, J-M. Hepatitis C Virus Resistance to Direct-Acting Antiviral Drugs in Interferon-Free Regimens. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz J, Lohmann V. Therapeutic preparedness: DAA-resistant HCV variants in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology 2023, 78, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann V, Korner F, Koch J. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 1999, 285, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann V, Hoffmann S, Herian U. Viral and cellular determinants of hepatitis C virus RNA replication in cell culture. J Virol 2003, 77, 3007–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Furusaka A, Tokushige K, Mizokami M, Wakita T. 2003. Efficient replication of the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. Gastroenterology 125:1808-1817.

- Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623-626.

- Pietschmann T, Kaul A, Koutsoudakis G, Shavinskaya A, Kallis S, Steinmann E, Abid K, Negro F, Dreux M, Cosset FL, Bartenschlager R. 2006. Construction and characterization of infectious intragenotypic and intergenotypic hepatitis C virus chimeras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:7408-7413.

- Pham LV, Ramirez S, Gottwein JM, Fahnoe U, Li YP, Pedersen J, Bukh J. 2018. HCV Genotype 6a Escape From and Resistance to Velpatasvir, Pibrentasvir, and Sofosbuvir in Robust Infectious Cell Culture Models. Gastroenterology 154:2194-2208 e12.

- Yi M, Villanueva RA, Thomas DL, Wakita T, Lemon SM. 2006. Production of infectious genotype 1a hepatitis C virus (Hutchinson strain) in cultured human hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:2310-5.

- Li YP, Ramirez S, Jensen SB, Purcell RH, Gottwein JM, Bukh J. 2012. Highly efficient full-length hepatitis C virus genotype 1 (strain TN) infectious culture system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:19757-19762.

- Ramirez S, Mikkelsen LS, Gottwein JM, Bukh J. 2016. Robust HCV Genotype 3a Infectious Cell Culture System Permits Identification of Escape Variants With Resistance to Sofosbuvir. Gastroenterology 151:973-985.e2.

- Harak C, Meyrath M, Romero-Brey I, Schenk C, Gondeau C, Schult P, Esser-Nobis K, Saeed M, Neddermann P, Schnitzler P, Gotthardt D, Perez-Del-Pulgar S, Neumann-Haefelin C, Thimme R, Meuleman P, Vondran FW, De FR, Rice CM, Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V. 2016. Tuning a cellular lipid kinase activity adapts hepatitis C virus to replication in cell culture. Nat Microbiol 2:16247.

- Ilboudo A, Nault J-C, Dubois-Pot-Schneider H, Corlu A, Zucman-Rossi J, Samson M, Le Seyec J. 2014. Overexpression of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type IIIα is associated with undifferentiated status and poor prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 14:7.

- Neddermann P, Quintavalle M, Di Pietro C, Clementi A, Cerretani M, Altamura S, Bartholomew L, De Francesco R. 2004. Reduction of hepatitis C virus NS5A hyperphosphorylation by selective inhibition of cellular kinases activates viral RNA replication in cell culture. J Virol 78:13306-13314.

- Heuss C, Rothhaar P, Burm R, Lee JY, Ralfs P, Haselmann U, Stroh LJ, Colasanti O, Tran CS, Schafer N, Schnitzler P, Merle U, Bartenschlager R, Patel AH, Graw F, Krey T, Laketa V, Meuleman P, Lohmann V. 2022. A Hepatitis C virus genotype 1b post-transplant isolate with high replication efficiency in cell culture and its adaptation to infectious virus production in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010472.

- Saeed M, Andreo U, Chung HY. SEC14L2 enables pan-genotype HCV replication in cell culture. Nature 2015, 524, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa R, Todt D, Zapatero-Belinchon F, Schenk C, Anastasiou OE, Walker A, Hertel B, Timmer L, Bojkova D, Ruckert M, Sarrazin C, Timm J, Lohmann V, Manns MP, Steinmann E, von Hahn T, Ciesek S. 2019. SEC14L2, a lipid-binding protein, regulates HCV replication in culture with inter- and intra-genotype variations. J Hepatol 70:603-614.

- Vrolijk JM, Kaul A, Hansen BE, Lohmann V, Haagmans BL, Schalm SW, Bartenschlager R. 2003. A replicon-based bioassay for the measurement of interferons in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Virol Methods 110:201-209.

- Jo J, Aichele U, Kersting N, Klein R, Aichele P, Bisse E, Sewell AK, Blum HE, Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V, Thimme R. 2009. Analysis of CD8+ T-cell-mediated inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication using a novel immunological model. Gastroenterology 136:1391-1401.

- Frese M, Barth K, Kaul A, Lohmann V, Schwarzle V, Bartenschlager R. 2003. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is resistant to tumour necrosis factor-alpha. J Gen Virol 84:1253-1259.

- Gambato M, Gregori J, Quer J, Koutsoudakis G, González P, Caro-Pérez N, García-Cehic D, García-González N, González-Candelas F, Esteban JI, Crespo G, Navasa M, Forns X, Pérez-del-Pulgar S. 2019. Hepatitis C virus intrinsic molecular determinants may contribute to the development of cholestatic hepatitis after liver transplantation. Journal of General Virology 100:63-68.

- Berg S, Kutra D, Kroeger T, Straehle CN, Kausler BX, Haubold C, Schiegg M, Ales J, Beier T, Rudy M, Eren K, Cervantes JI, Xu B, Beuttenmueller F, Wolny A, Zhang C, Koethe U, Hamprecht FA, Kreshuk A. 2019. ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat Methods 16:1226-1232.

- Bojjireddy N, Botyanszki J, Hammond G, Creech D, Peterson R, Kemp DC, Snead M, Brown R, Morrison A, Wilson S, Harrison S, Moore C, Balla T. 2014. Pharmacological and genetic targeting of the PI4KA enzyme reveals its important role in maintaining plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels. J Biol Chem 289:6120-6132.

- Koutsoudakis G, Herrmann E, Kallis S. The level of CD81 cell surface expression is a key determinant for productive entry of hepatitis C virus into host cells. J Virol 2007, 81, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones CT, Catanese MT, Law LMJ, Khetani SR, Syder AJ, Ploss A, Oh TS, Schoggins JW, MacDonald MR, Bhatia SN, Rice CM. 2010. Real-time imaging of hepatitis C virus infection using a fluorescent cell-based reporter system. Nature Biotechnology 28:167-171.

- Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V, Penin F. 2013. The molecular and structural basis of advanced antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:482-496.

- Ferenci P, Scherzer TM, Kerschner H, Rutter K, Beinhardt S, Hofer H, Schöniger–Hekele M, Holzmann H, Steindl–Munda P. 2008. Silibinin Is a Potent Antiviral Agent in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C Not Responding to Pegylated Interferon/Ribavirin Therapy. Gastroenterology 135:1561-1567.

- Esser-Nobis K, Romero-Brey I, Ganten TM, Gouttenoire J, Harak C, Klein R, Schemmer P, Binder M, Schnitzler P, Moradpour D, Bartenschlager R, Polyak SJ, Stremmel W, Penin F, Eisenbach C, Lohmann V. 2013. Analysis of hepatitis C virus resistance to silibinin in vitro and in vivo points to a novel mechanism involving nonstructural protein 4B. Hepatology 57:953-963.

- Coelmont L, Hanoulle X, Chatterji U, Berger C, Snoeck J, Bobardt M, Lim P, Vliegen I, Paeshuyse J, Vuagniaux G, Vandamme AM, Bartenschlager R, Gallay P, Lippens G, Neyts J. 2010. DEB025 (Alisporivir) inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by preventing a cyclophilin A induced cis-trans isomerisation in domain II of NS5A. PLoS One 5:e13687.

- Fernandes F, Ansari I-uH, Striker R. 2010. Cyclosporine Inhibits a Direct Interaction between Cyclophilins and Hepatitis C NS5A. PLOS ONE 5:e9815.

- Hanoulle X, Badillo A, Wieruszeski JM, Verdegem D, Landrieu I, Bartenschlager R, Penin F, Lippens G. 2009. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein is a substrate for the peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase activity of cyclophilins A and B. J Biol Chem 284:13589-13601.

- Wagoner J, Negash A, Kane OJ, Martinez LE, Nahmias Y, Bourne N, Owen DM, Grove J, Brimacombe C, McKeating JA, Pecheur EI, Graf TN, Oberlies NH, Lohmann V, Cao F, Tavis JE, Polyak SJ. 2010. Multiple effects of silymarin on the hepatitis C virus lifecycle. Hepatology 51:1912-1921.

- Guedj J, Dahari H, Pohl RT. Understanding silibinin's modes of action against HCV using viral kinetic modeling. J Hepatol 2012, 56, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaising J, Lévy PL, Gondeau C, Phelip C, Varbanov M, Teissier E, Ruggiero F, Polyak SJ, Oberlies NH, Ivanovic T, Boulant S, Pécheur EI. 2013. Silibinin inhibits hepatitis C virus entry into hepatocytes by hindering clathrin-dependent trafficking. Cell Microbiol 15:1866-82.

- Wu Y, Liao Q, Yang R. A novel luciferase and GFP dual reporter virus for rapid and convenient evaluation of hepatitis C virus replication. Virus Research 2011, 155, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Li C, Yuan P, Cai C, Zhang L, Luo GG, Wei W. 2015. A Dual-Reporter System for Real-Time Monitoring and High-throughput CRISPR/Cas9 Library Screening of the Hepatitis C Virus. Scientific Reports 5:8865.

- Xiao F, Fofana I, Heydmann L. Hepatitis C Virus Cell-Cell Transmission and Resistance to Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents. PLOS Pathogens 2014, 10, e1004128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao F, Zhao T, Deng L, Lv D, Zhang X, Pan X, Xu J, Long G. 2017. Visualizing the Essential Role of Complete Virion Assembly Machinery in Efficient Hepatitis C Virus Cell-to-Cell Transmission by a Viral Infection-Activated Split-Intein-Mediated Reporter System. Journal of Virology 91:10.1128/jvi.01720-16.

- Andreo U, de Jong YP, Scull MA, Xiao JW, Vercauteren K, Quirk C, Mommersteeg MC, Bergaya S, Menon A, Fisher EA, Rice CM. 2017. Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Particle Heterogeneity in Immunodeficient Human Liver Chimeric fah-/- Mice. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology 4:405-417.

- Ball JK, Tarr AW, McKeating JA. The past, present and future of neutralizing antibodies for hepatitis C virus. Antiviral Res 2014, 105, 100–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetris, AJ. 2009. Evolution of hepatitis C virus in liver allografts. Liver Transplantation 15:S35-S41.

- Fafi-Kremer S, Fofana I, Soulier E, Carolla P, Meuleman P, Leroux-Roels G, Patel AH, Cosset F-L, Pessaux P, Doffoël M, Wolf P, Stoll-Keller F, Baumert TF. 2010. Viral entry and escape from antibody-mediated neutralization influence hepatitis C virus reinfection in liver transplantation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 207:2019-2031.

- Schvoerer E, Soulier E, Royer C, Renaudin A-C, Thumann C, Fafi-Kremer S, Brignon N, Doridot S, Meyer N, Pinson P, Ellero B, Woehl-Jaegle M-L, Meyer C, Wolf P, Zachary P, Baumert T, Stoll-Keller F. 2007. Early Evolution of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Quasispecies after Liver Transplant for HCV-Related Disease. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 196:528-536.

- Thomssen R, Bonk S, Thiele A. 1993. Density heterogeneities of hepatitis C virus in human sera due to the binding of beta-lipoproteins and immunoglobulins. Med Microbiol Immunol Berl 182:329-334.

- Kim H, Yi J, Yu J, Park J, Jang SK. 2022. A Simple and Effective Method to Concentrate Hepatitis C Virus: Aqueous Two-Phase System Allows Highly Efficient Enrichment of Enveloped Viruses. Viruses 14.

- Bagaglio S, Messina E, Hasson H, Galli A, Uberti-Foppa C, Morsica G. 2019. Geographic Distribution of HCV-GT3 Subtypes and Naturally Occurring Resistance Associated Substitutions. Viruses 11.

- Fernandez-Antunez C, Wang K, Fahnøe U. Characterization of multi-DAA resistance using a novel hepatitis C virus genotype 3a infectious culture system. Hepatology 2023, 78, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, C. 2021. Treatment failure with DAA therapy: Importance of resistance. Journal of Hepatology 74:1472-1482.

- Smith D, Magri A, Bonsall D, Ip CLC, Trebes A, Brown A, Piazza P, Bowden R, Nguyen D, Ansari MA, Simmonds P, Barnes E. 2019. Resistance analysis of genotype 3 hepatitis C virus indicates subtypes inherently resistant to nonstructural protein 5A inhibitors. Hepatology 69:1861-1872.

- Vo-Quang E, Soulier A, Ndebi M, Rodriguez C, Chevaliez S, Leroy V, Fourati S, Pawlotsky JM. 2023. Virological characterization of treatment failures and retreatment outcomes in patients infected with "unusual" HCV genotype 1 subtypes. Hepatology 78:607-620.

- Mariño Z, Crespo G, D'Amato M, Brambilla N, Giacovelli G, Rovati L, Costa J, Navasa M, Forns X. 2013. Intravenous silibinin monotherapy shows significant antiviral activity in HCV-infected patients in the peri-transplantation period. J Hepatol 58:415-20.

- Bankwitz D, Bahai A, Labuhn M, Doepke M, Ginkel C, Khera T, Todt D, Stroh LJ, Dold L, Klein F, Klawonn F, Krey T, Behrendt P, Cornberg M, McHardy AC, Pietschmann T. 2021. Hepatitis C reference viruses highlight potent antibody responses and diverse viral functional interactions with neutralising antibodies. Gut 70:1734-1745.

- Salas JH, Urbanowicz RA, Guest JD. An Antigenically Diverse, Representative Panel of Envelope Glycoproteins for Hepatitis C Virus Vaccine Development. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, AL. 2020. Challenges and Promise of a Hepatitis C Virus Vaccine. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.

| Serum | Date and cohort | Titer1 | Gt | HCV RNA pi2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4468 | 2016 Frankfurt 2016(DZIF)2016 |

1,02E+07 | 1b | Yes |

| 5342 | 2016 Frankfurt | 5,78E+05 | 1b | No |

| 3617 | 2015 Frankfurt | 3,81E+06 | 1b | Cells died |

| 2054 | 2015 Frankfurt | 4,10E+05 | 1b | No |

| 4695 | 2016 Frankfurt | 2,97E+05 | 1b | No |

| 2823 | 2021 Frankfurt | 9,73E+05 | 1b | No |

| 3260 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,95E+06 | 1b | No |

| 7437 | 2016 Frankfurt | 3,07E+05 | 1b | No |

| 5120 | 2016 Frankfurt | 7,64E+05 | 1b | No |

| 4153 | 2016 Frankfurt | 7,61E+05 | 1b | No |

| 4886 | 2016 Frankfurt | 4,98E+05 | 1b | No |

| 3676 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,00E+06 | 1b | No |

| 6936 | 2017 Frankfurt | 6,52E+05 | 1b | No |

| 6087 | 2017 Frankfurt | 2,90E+05 | 1b | No |

| 4202 | 2016 Frankfurt | 1,72E+04 | 1b | No |

| 5613 | 2017 Frankfurt | 1,89E+05 | 1b | No |

| 1199 | 2014 Frankfurt | 7,24E+03 | 1b | No |

| 1597 | 2015 Frankfurt | 3,01E+06 | 1b | Cells died |

| 521 | 2020 Heidelberg | 7,85E+05 | 1a | No |

| 566 | 2020 Heidelberg | Not detectable | 1b | No |

| 574 | 2020 Heidelberg | 2,72E+06 | 1b | No |

| 572 | 2020 Heidelberg | 4,24E+05 | 1b | No |

| 77 | 2013 Heidelberg | 3,92E+03 | 1b | No |

| 570 | 2020 Heidelberg | 2,98E+05 | 1b | No |

| 579 | 2020 Heidelberg | 8,96E+03 | 1a | No |

| 210 | 2014 Frankfurt (DZIF) | 1,78E+06 | 1b | No |

| GLT1 | 2014 Heidelberg | 4,22E+07 | 1b | Yes |

| Serum | Date and cohort | Titer1 | LTx2y/n | Gt | HCV RNA pi3 | Infected cells4 | Difference to DCV control p<0.05 (RT-qPCR / AIA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1aHT | 2016 Heidelberg | 4,25E+06 | y | 1a | No | No | No / No |

| 1 | 2010 Barcelona | 3,24E+07 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / No |

| 14 | 2011 Barcelona | 6,74E+06 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / No |

| 41 | 2012 Barcelona | 8,74E+06 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / No |

| 43 | 2012 Barcelona | 3,84E+06 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / No |

| 44 | 2012 Barcelona | 9,11E+06 | y | 1b | Yes | No | No / No |

| 60 | 2012 Barcelona | 5,04E+07 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / Yes |

| 76 | 2013 Barcelona | 4,95E+06 | y | 1b | Yes | No | No / No |

| 81 | 2014 Barcelona | 1,03E+07 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | Yes / No |

| 84 | 2014 Barcelona | 1,24E+08 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / Yes |

| 88 | 2014 Barcelona | 1,13E+06 | y | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 1673 | 2015 Frankfurt | 9,88E+05 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 1730 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,49E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 1754 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,68E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2014 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,79E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2072 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,35E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2121 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,87E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2130 | 2015 Frankfurt | 4,97E+06 | n | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / No |

| 2149 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,11E+06 | n | 1b | No | Yes | No / No |

| 2213 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,29E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2282 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,02E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2289 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,46E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2668 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,46E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2672 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,55E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 2711 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,17E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 3266 | 2015 Frankfurt | 2,37E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 4244 | 2015 Frankfurt | 3,06E+06 | n | 1b | No | No | No / No |

| 5651 | 2016 Frankfurt | 2,17E+06 | n | 1b | No | Yes | No / No |

| GLT1 | 2014 Heidelberg | 4,22E+07 | y | 1b | Yes | Yes | No / Yes |

| Serum | Date of aquisition | Serum titer1 | Gt | LTx2 y/n |

Serum volume | Input infection3 | Input epo3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2015 Freiburg | 1,40E+06 | 1b | n | 10 mL* | 1,12E+05 | 9,06E+05 |

| 11 | 2015 Freiburg | 2,07E+06 | 1b | n | 10 mL* | 1,66E+05 | 4,89E+05 |

| 12 | 2015 Freiburg | 5,20E+06 | 1b | n | 10 mL* | 4,16E+05 | 5,67E+06 |

| 13 | 2015 Freiburg | 7,41E+05 | 1b | n | 10 mL* | 5,93E+04 | 1,02E+06 |

| 750 | 2022 Heidelberg | 2,28E+06 | 1b | n | 10 mL* | 1,82E+05 | 2,70E+04 |

| 751 | 2022 Heidelberg | 2,69E+05 | 1b | n | 10 mL* | 2,15E+04 | 2,10E+04 |

| 2130 | 2015 Frankfurt | 4,97E+06 | 1b | n | 1 mL | 3,98E+05 | 1,06E+06 |

| 2213 | 2015 Frankfurt | 1,29E+06 | 1b | n | 1 mL | 1,03E+05 | 7,31E+05 |

| GLT1 | 2014 Heidelberg | 4,22E+07 | 1b | y | 1 mL | 3,38E+06 | 1,22E+06 |

| 1aHT | 2016 Heidelberg | 4,25E+06 | 1a | y | 1 mL | 3,40E+05 | 6,19E+04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).