1. Introduction

Steroids are chemical compounds—derivatives of cyclopentaneperhydrophenanthrene that are utilized in medicine as anti-inflammatory agents, contraceptives, anabolic steroids, hormone therapies, or immunosuppressive drugs [

1,

2]. Their critical role in treating certain autoimmune diseases and specific types of cancer has been recognized [

3], and the steroid market ranks second only to antibiotics [

4]. Testosterone (TS) is considered one of the most medically significant steroids [

5]. In 2023, the global market for TS therapy was valued at approximately

$1.9 billion, with projections suggesting it will reach

$2.5 billion by 2030 [

6]. Current industrial production techniques for TS involve multiple steps of chemical synthesis, resulting in low yields due to stereoisomerism and the formation of byproducts [

7]. These processes are also considered more expensive than biological synthesis methods [

8]. As a result, microbial biotransformation has been employed for several years to obtain novel or modified steroids. Many of these transformations are facilitated by fungal CYP450 enzymes [

9].

The synthesis of steroids is initiated through the biotransformation of phytosterols, which are derived from plants [

10], into molecules such as progesterone (PG) or androstenedione (AD) following the removal of their C17 side chains. This transformation is generally carried out by

Mycobacterium smegmatis [

4]. Subsequent chemical modifications are typically required to synthesize commercially relevant compounds. One of the most important modifications is the introduction of a hydroxyl group at C-11 of the sterane nucleus, which imparts anti-inflammatory properties to the molecule. 11-α-hydroxylation can be achieved through chemical synthesis, a process that is time-consuming and associated with higher environmental and economic costs, or through biotransformation, which is performed by certain species of

Aspergillus and

Rhizopus [

11,

12,

13]. However, the requirement for a second fermentation to hydroxylate primary compounds, which are also obtained in the first fermentation after side-chain removal, necessitates the purification of intermediate products, the addition of further compounds and nutrients, and increased time and costs to obtain the final product. Therefore, cloning the gene encoding 11-α-hydroxylase has been deemed advantageous for generating a microorganism capable of performing both transformations in a single fermentation step.

The steroid 11-α-hydroxylase enzyme was cloned from

Rhizopus (

CYP509c12) some time ago [

13]. This enzyme is capable of hydroxylating several sites within the steroid molecule, including PG. However, the presence of multiple hydroxylation sites complicates its application in industrial processes due to the difficulty of separating the hydroxylated products. Subsequently, our group cloned the gene encoding 11-α-hydroxylase from

Aspergillus nidulans (

CYP68L1) [

14] using the suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) method described by Diatchenko et al. in 1996 [

15]. Similar subtractive protocols have been employed to clone additional genes encoding other CYP450 proteins from

A. nidulans [

16]. The creation of a knockout strain of

A. nidulans lacking 11-α-hydroxylating activity (KO strain) enabled definitive functional testing [

14]. Additionally, a gene previously described and patented as encoding the 11-α-hydroxylase from

Aspergillus ochraceus (

CYP68AQ1, now renamed

CYP68J5) [

17,

18] was expressed in the knockout strain. It has been reported that TS production was achieved by expressing the enzyme 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from

Cochliobolus lunatus (17-β-hydroxysteroid: NADP 17-oxidoreductase, EC 1.1.1.51) in

M. smegmatis [

19].

In this study, the gene from

A. ochraceus (

CYP68L8), an industrial producer of 11-α-hydroxylated steroids, was identified following the cloning of the gene from

A. nidulans. Moreover, the gene previously described and patented as encoding the 11-α-hydroxylase from

A. ochraceus (

CYP68AQ1, now renamed

CYP68J5) was expressed in the knockout strain. Although previous studies indicated that the knockout strain was incapable of hydroxylating TS, 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from

C. lunatus was expressed in this strain to evaluate its potential for TS production via biotransformation (

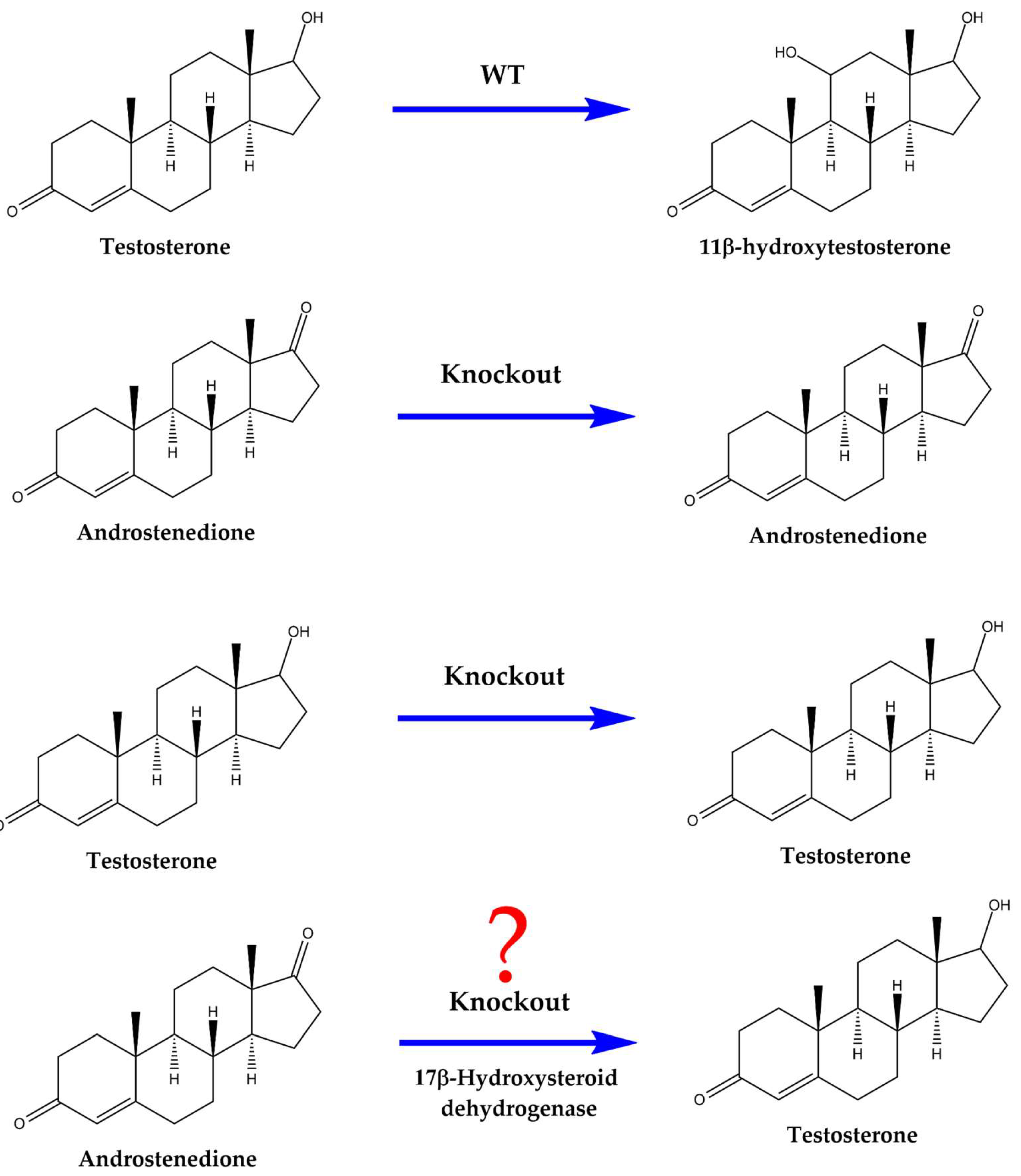

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Biochemical Reagents

The pure steroid compounds were either purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) or received as gifts from Gadea Biopharma (León, Spain). All chemical reagents used for media preparation were supplied by Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA), VWR (USA), and Condalab (Spain). HPLC-grade acetonitrile was provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). Molecular biology reagents were obtained from BioTools (USA) and Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). Oligonucleotides were supplied by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

2.2. Culture Conditions

To obtain spores, the fungal strains (

Table 1) were cultivated on plates containing a complex medium composed of 1.75 g malt extract, 2.75 g dextrins, 2.35 g glycerol, and 0.78 g peptone per liter, along with 15 g agar per liter of water (malt extract agar obtained from Pronadisa, Spain). Spores were spread on the surface of the plates and incubated at the required temperature. The spores were harvested by scraping and resuspended in 0.1% Tween 80. They were then washed and collected by centrifugation (3500 × g) before being resuspended in 0.1 % Tween 80. A chemically defined medium (MM) consisting of KH₂PO₄ 1.36 g/L, (NH₄)₂SO₄ 2 g/L, MgSO₄·7H₂O 0.25 g/L, and Hunter salts 1 mL/L was used [

14,

20]. For fermentations, the potassium phosphate concentration was increased to 100 mM (13.6 g/L) to prevent pH fluctuations during fermentation. For the preparation of solid media, 1.5% (w/v) agar was added.

A. nidulans was cultured at 37°C, while

A. ochraceus,

C. lunatus, and

Rhizopus were grown at 32°C [

20]. All liquid fermentation media were inoculated with 10⁶ spores/mL.

2.3. DNA Manipulation

All DNA manipulations were performed using standard protocols or commercial kits. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin Plasmid Extract kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, DNA fragments from agarose gel and PCR reactions were purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-Up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany).

Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue was used as the host for plasmid propagation and molecular biology manipulations. LB medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics, was used, and cultures were incubated at 37°C.

E. coli cells were transformed by electroporation, following the protocol described by Miller and Nickoloff [

21]. Recombinant strains of

A. nidulans were generated according to established protocols [

14,

22].

RNA extraction was carried out using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) from extracted RNA with oligo dT primers. This cDNA was then used to amplify the target gene with specific primers. These primers included restriction site sequences for a suitable enzyme to facilitate gene cloning into the expression plasmid (p1660). The Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was employed to generate double-stranded cDNA for subtractive hybridization [

14]. When necessary, mRNA was isolated using the Mag-Bind mRNA Kit (VWR Omega, USA) with magnetic bead enrichment.

PCR conditions were optimized according to the primers used (

Table 2). DNA encoding the target protein was isolated from the pBluescript plasmid either by restriction enzyme digestion or by PCR using the appropriate primers. This DNA fragment was cloned into the expression plasmid (p1660) at the

NcoI and

EcoRI restriction sites, and following ligation, sequencing was performed to confirm the absence of mutations. The p1660 plasmid contains the glyceraldehyde Phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD) promoter to drive the expression of cloned genes, and the

pyroA gene serves as the selection marker. The p1660 plasmid was provided by Dr. M. A. Peñalva (Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, CSIC, Madrid, Spain) [

23]. PCR amplifications were routinely performed using Phire Polymerase and Phusion Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with DNase was utilized to obtain double-stranded cDNA. Sanger sequencing of the various constructs was carried out by Secugen S.L. (Madrid, Spain).

2.4. HPLC Analysis

Culture broth analysis was performed as described by Ortega-De los Ríos et al. (2017) [

14]. Samples of culture medium (5 mL) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was then isolated and evaporated, and the resulting pellet was dissolved in an equivalent volume of ethanol. Samples were filtered through a 0.22-μm PTFE syringe filter before HPLC analysis [

14].

HPLC analyses were conducted using an Alliance 2690 HPLC system coupled to a 996 photodiode array detector (Waters). A Kromasil 100 C18 5 µm 25 × 0.46 cm column, along with a Nucleosil C18 5 µm 1 × 0.46 cm precolumn, was employed. Isocratic flow (1.5 mL/min) of acetonitrile and water (60:40 by volume) was used, and data processing was carried out using Empower3 software (Waters) [

14]. Under these conditions, the retention times were as follows (in minutes): AD, 5.3 ± 0.3; 11-α-hydroxylation of AD (11-α-OH-AD), 2.6 ± 0.2; PG, 10.8 ± 0.5; 11-α-hydroxylation of PG (11-α-OH-PG), 3.4 ± 0.3; and TS, 4.3 ± 0.2.

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

BLAST software [

24] and the NCBI Learn page (

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/learn/) were used to search for homologous genes and proteins among the microorganisms studied. The selected sequences were aligned using BioEdit software version 7.2.6.1 (Carlsbad, CA, USA) with native ClustalW (version 1.4, Heidelberg, Germany) [

25]. The results and their graphical representations were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v.6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results

Aspergillus nidulans Exhibit an Inducible Steroid 11-α-Hydroxylase Activity That Is Not Replaced by CYP68J5 from Aspergillus ochraceus

11-α-hydroxylation of steroids has been reported in several members of the

Aspergillus genus. The fermentation media of

A. nidulans and

A. ochraceus in the presence of AD, PG, and TS were analyzed by HPLC [

14], and the presence of 11-α-hydroxylated derivatives of AD, PG, and TS was confirmed.

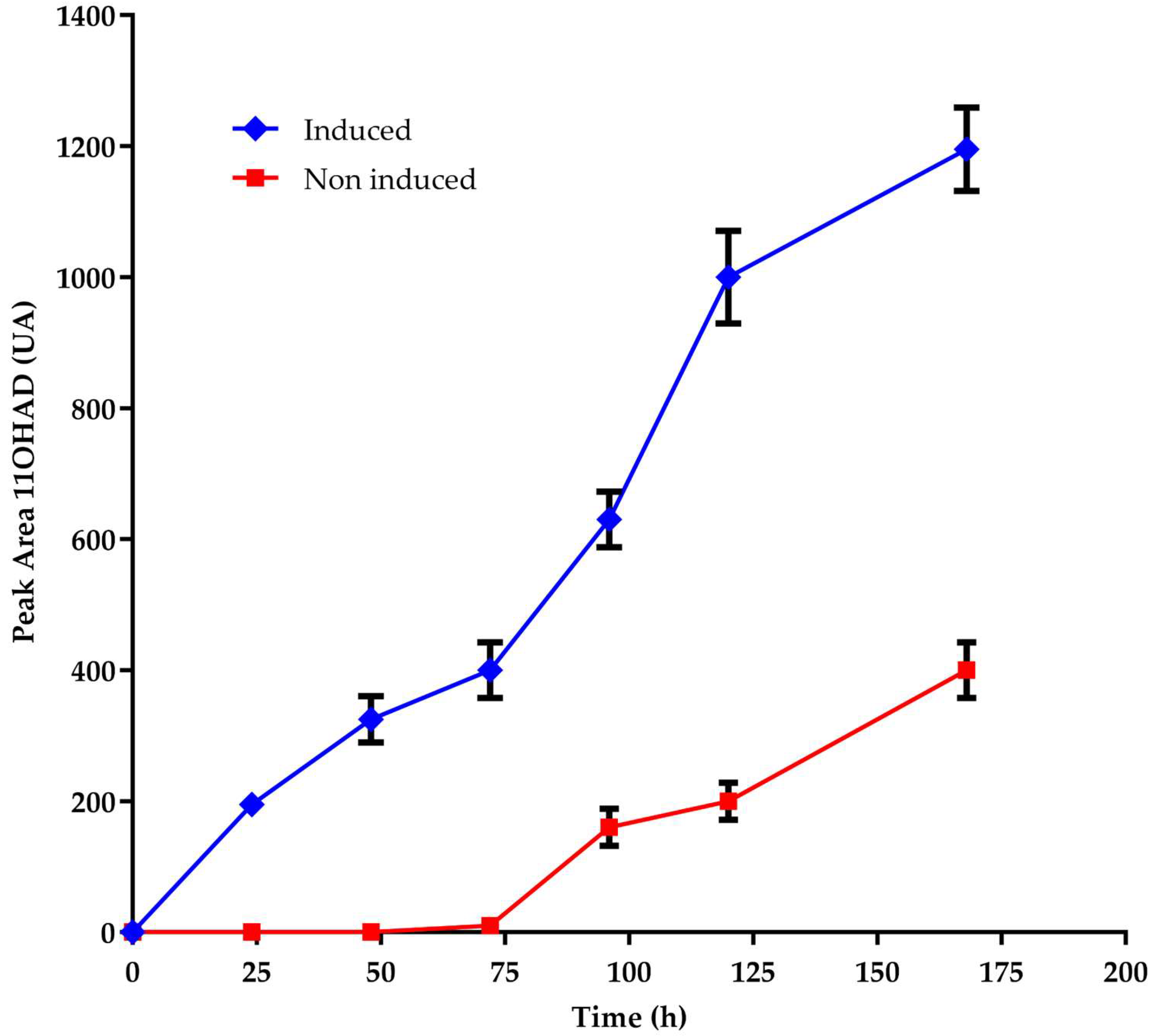

No references to the steroid 11-α-hydroxylase gene were found in existing databases, and no relevant mutants had been described. Therefore, to clone the gene encoding steroid 11-α-hydroxylase, the inducibility of the hydroxylating activity was also investigated. It was found that this activity is rapidly inducible by certain steroid molecules, such as AD, TS, and PG [

14]. When cultures of

A. nidulans were transferred from minimal media, grown with or without 1 g/L AD, to media containing AD, a delayed onset of steroid hydroxylating activity was observed in cultures previously grown without AD. This finding suggests that the induction of specific enzymes is necessary to hydroxylate AD, PG, and TS (

Figure 2).

The 11-α-hydroxylase enzyme was cloned using suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) [

15,

16], leveraging the inducibility of this enzymatic activity. Following SSH, several cDNA clones corresponding to CYP450 enzymes were obtained based on sequence analysis. One of these clones was found to be relatively abundant (4 out of 100). This protein was designated as AN8530 in the databases. The inducibility of this protein (using AD, TS, and PG as inducers) was analyzed by RT-PCR, and it was determined that the protein was induced by all three compounds. Nearly undetectable mRNA expression levels were observed in non-induced cultures grown in the absence of AD, TS, and PG [

14].

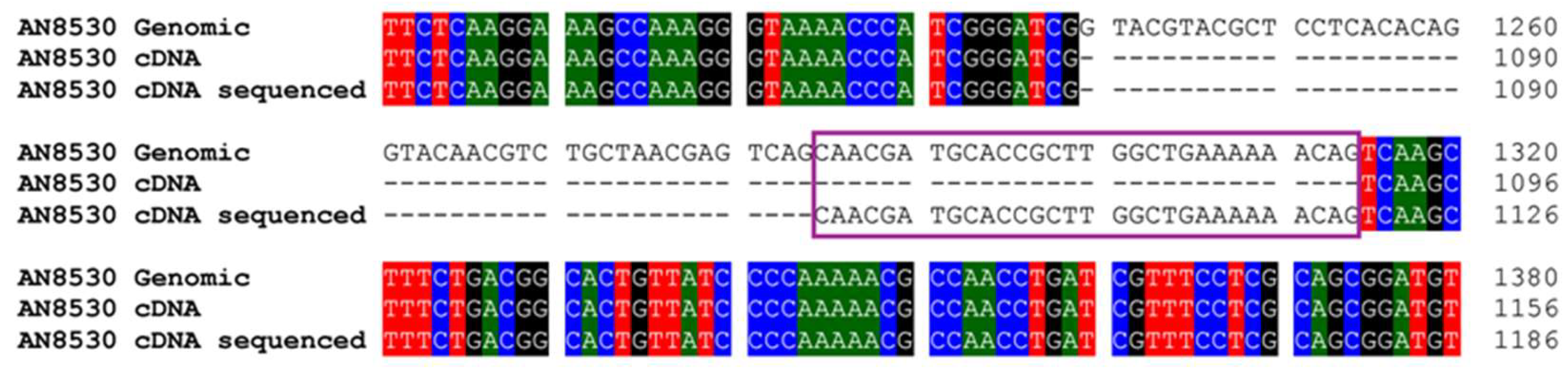

Upon sequencing this cDNA, discrepancies were found compared to the predicted intron structure in the database. Specifically, one intron was shorter than expected, with the subsequent exon beginning 24 nucleotides earlier than predicted (

Figures 3 and S1). After the analysis of this CYP450 cDNA, the gene was cloned for gene disruption, and an

A. nidulans knockout strain for this CYP450 was generated. It was discovered that no 11-α-hydroxylase activity for AD, TS, or PG was present in the knockout strain [

14].

Hydroxylase activity was restored by expressing the gene encoding this CYP450 from

A. nidulans. Additionally, a patented protein with 11-α-hydroxylase activity from

A. ochraceus was identified [

17]. The patented protein (CYP68AQ1, renamed CYP68J5) (GenBank DD180525 for the genomic sequence, QKX96248.1 for the protein, and MN508259.1 for the gene) was expressed in the

A. nidulans knockout strain lacking 11-α-hydroxylase activity. All constructs were placed under the control of the GPD promoter from

A. nidulans. Upon sequencing the CYP450 from

A. nidulans, Dr. David Nelson designated this CYP450 as CYP68L1 (GenBank MF153379) [

26]. The complete sequence of the CYP450 from

A. ochraceus was also obtained and designated as CYP68AQ1 (GenBank DD180525.1) [

17], which was later renamed CYP68J5 (GenBank MN508259.1).

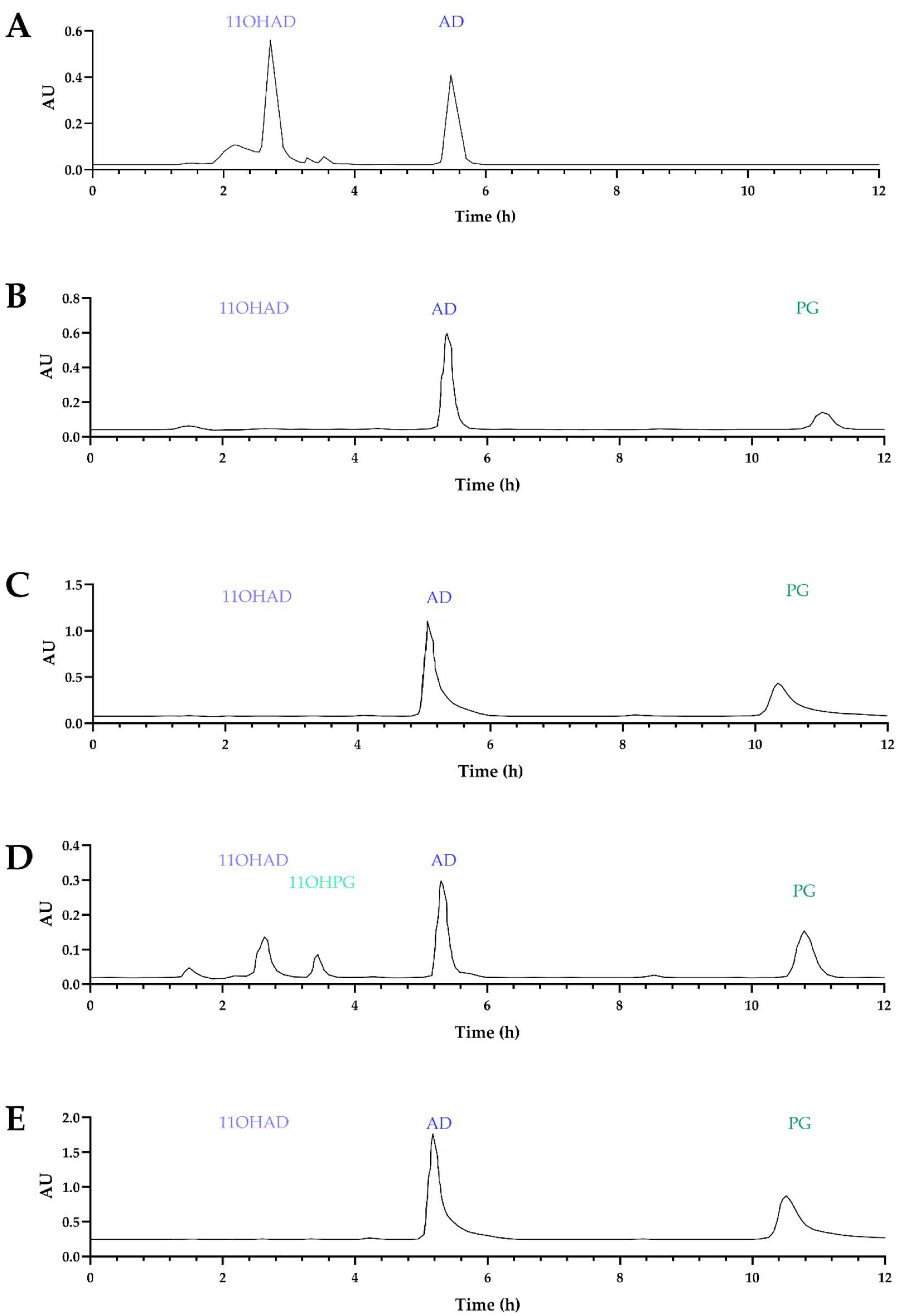

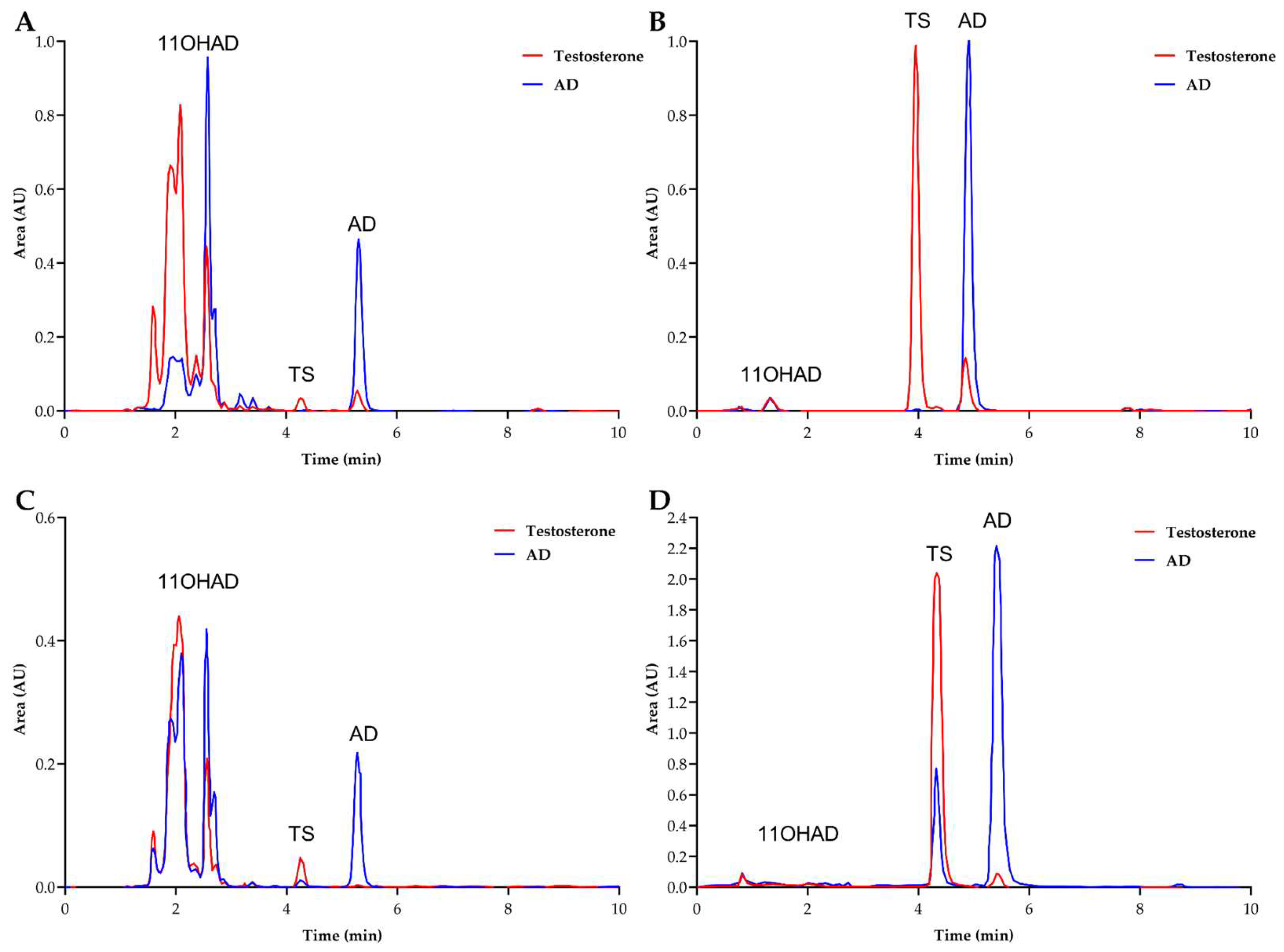

No hydroxylation of AD or PG was detected with the patented protein. As a control, 11-α-hydroxylase enzymes from

A. nidulans and

A. ochraceus cloned by our team were also expressed. Fermentations were conducted at 37°C for

A. nidulans and at 32°C for

A. ochraceus. Chromatograms of fermentation products indicated that hydroxylase activity was restored, except in the case of the patented protein (

Figure 4, A, B, and C). It can be concluded that this protein (CYP68AQ1) is not involved in the hydroxylation of these steroid molecules (AD, TS, and PG), whereas CYP68L1 from

A. nidulans restored this activity for AD.

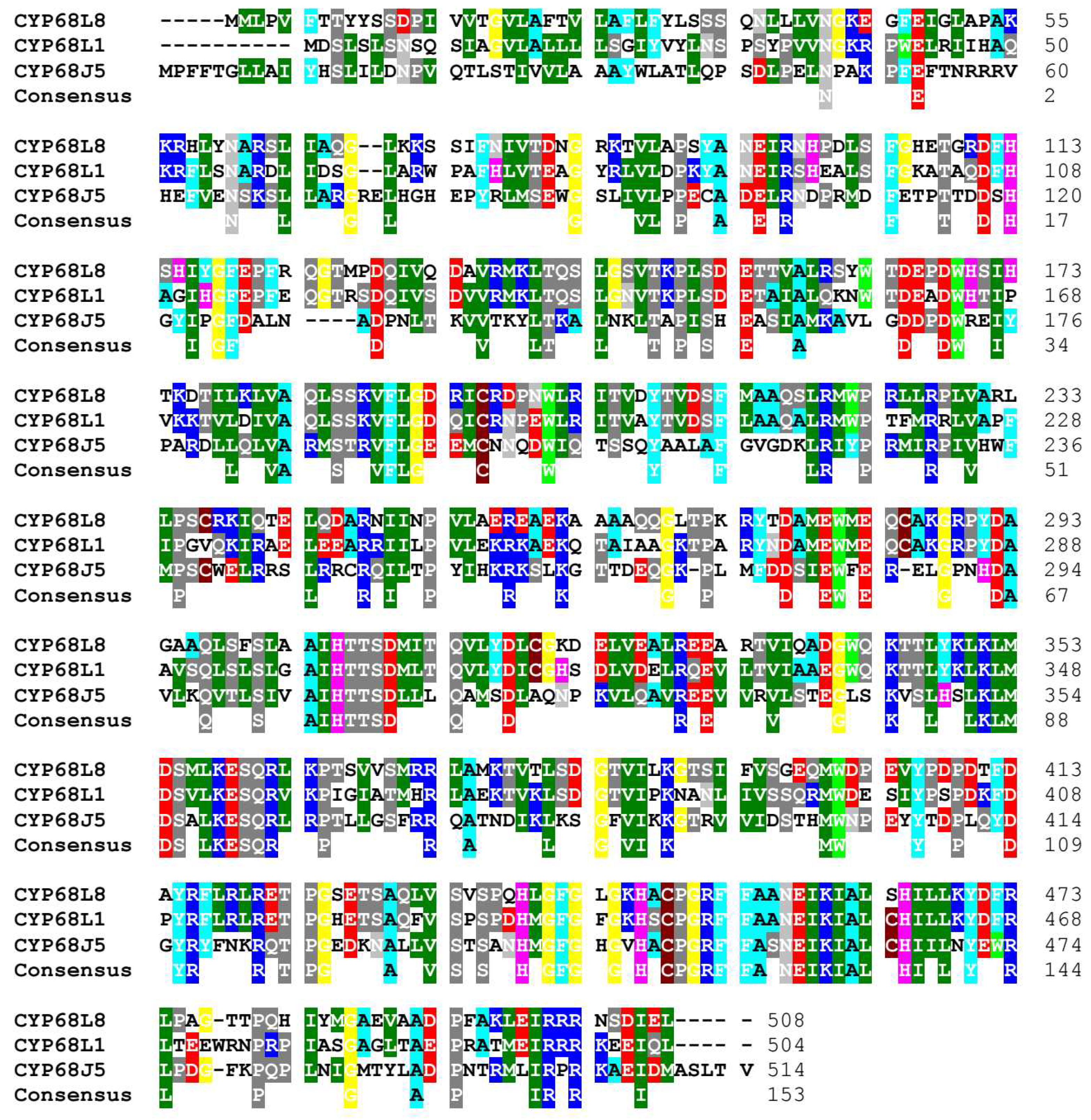

Identification of a New CYP450 with 11-α-Hydroxylase Activity in Aspergillus ochraceus

As shown in previous studies,

A. ochraceus exhibits 11-α-hydroxylase activity [

14]; however, this activity does not appear to be related to the patented CYP450 (CYP68AQ1 or CYP68J5). This prompted an investigation into the genome of

A. ochraceus for the ortholog of

A. nidulans CYP450L1 hydroxylase. A CYP450 with a high identity (62%) to

A. nidulans CYP68L1 was identified, and the complete gene sequence was isolated and sequenced. Dr. Nelson designated this enzyme as CYP68L8 (GenBank MF153380). In contrast, the putative steroid 11-α-hydroxylase (the patented CYP450, CYP68AQ1, renamed CYP68J5) exhibited a lower identity (36%) (

Figure 5). This finding further supports the observation of the lack of hydroxylation of AD and PG when this protein was expressed in the knockout strain (

Figure 4).

Following the identification of the CYP68L8 sequence, cloning was performed in the

A. nidulans knockout strain lacking 11-α-hydroxylase activity. It was observed that CYP68L8 restored 11-α-hydroxylase activity in the mutant strain (

Figure 4, D and E). All constructs were placed under the control of the GPD promoter from

A. nidulans.

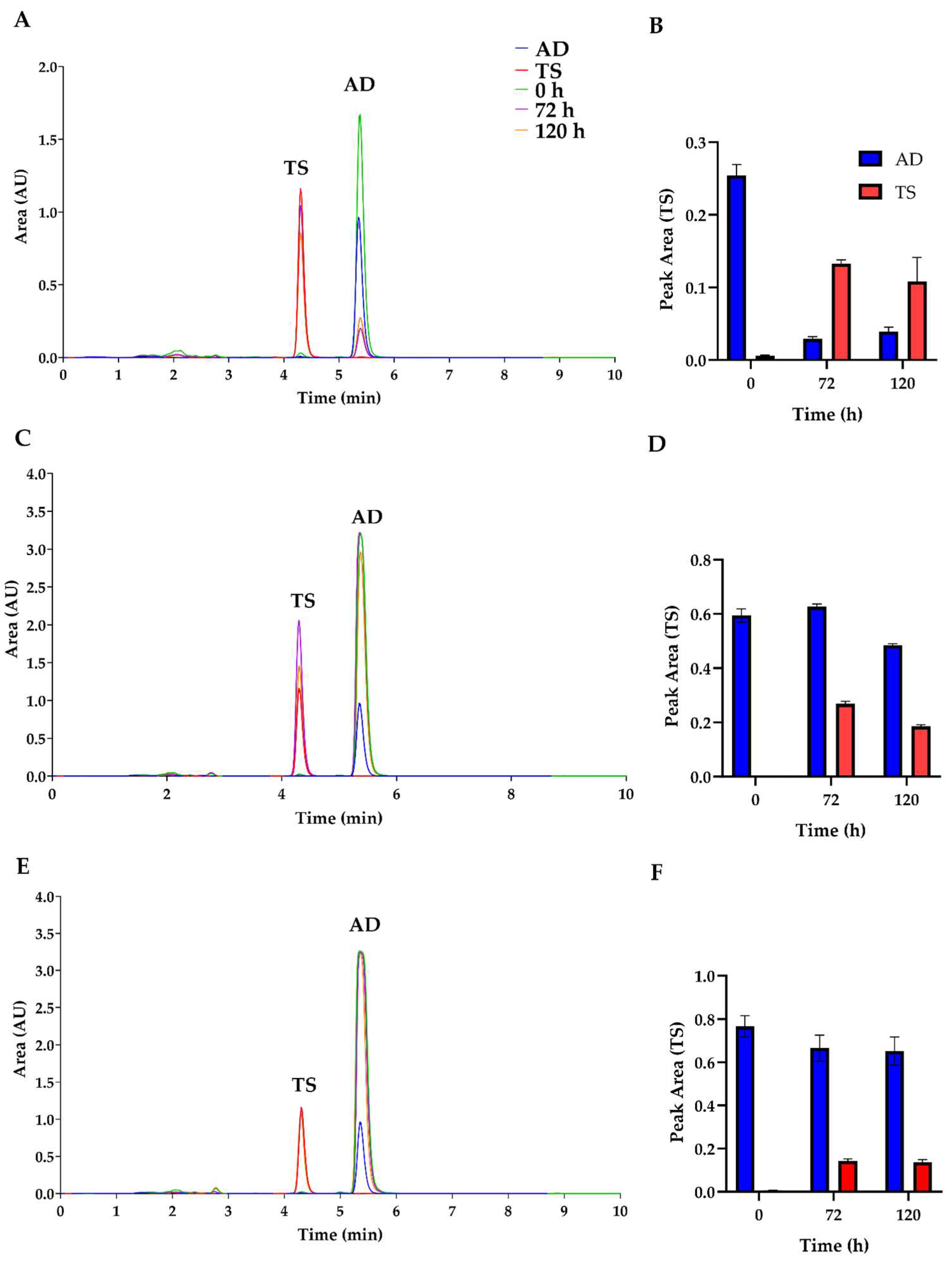

Production of Testosterone from the Steroid 11-α-Hydroxylase Knockout Strain of A. nidulans Expressing the Enzyme 17-β-Hydroxysteroid-Dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.51) from Cochliobolus lunatus (Curvularia lunata)

When TS was used as a substrate, several compounds were identified in the fermentation medium of the wild-type

A. nidulans strain [

14] (

Figure 6A). However, no modification of TS was detected in the 11-α-hydroxylase knockout strain, with only a small amount of AD observed, likely due to the endogenous 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity of

A. nidulans (

Figure 6B).

This suggests that all modified compounds are hydroxylated derivatives of TS. Fernández-Cabezón, L.et al. [

19] demonstrated the production of TS from AD by

M. smegmatis expressing 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from

C. lunatus. For this reason, the 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.51) from

C. lunatus and

A. nidulans was expressed in the knockout strain to obtain pure TS from AD. It was found that the

A. nidulans knockout strain expressing its enzyme was unable to convert AD into TS; however, when the enzyme from

Curvularia was expressed, this knockout strain was able to convert AD into TS with high efficiency (

Figure 6, C and D).

Additionally, fermentations fed with media supplemented with 0.1% AD converted more than 80% of AD into TS, a more valuable compound. However, increasing the amount of AD led to a decrease in TS production, likely due to the toxic effects or retardation of growth caused by high concentrations of AD in the fermentation medium (

Figure 7). At higher concentrations, AD is poorly soluble, resulting in the inability to obtain a representative sample of the total AD present in the broth for HPLC measurements [

27]. This issue could potentially be mitigated when fermentations are conducted with

A. ochraceus, due to its greater resistance or adaptation to higher concentrations of steroids compared to

A. nidulans [

28].

4. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the distinct roles of CYP68L1 from

Aspergillus nidulans and CYP68AQ1 (renamed CYP68J5) from

Aspergillus ochraceus in steroid hydroxylation [

18,

28,

29]. It was confirmed that

A. nidulans exhibits inducible steroid 11-α-hydroxylase activity, which was not complemented by the expression of CYP68J5 in the knockout strain. Overexpression of CYP68J5 in

A. ochraceus strains has been reported to hydroxylate steroids such as D-ethylgonendione and 16,17-α-epoxyprogesterone [

28,

29], while recombinant strains of

Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing this cytochrome were able to hydroxylate D-ethylgonendione and PG [

18]. However, the expression of this gene in the

A. nidulans knockout strain did not exhibit any 11-α-steroid hydroxylase activity. HPLC analysis of the fermentation medium of

A. nidulans revealed the presence of 11-α-hydroxylated derivatives of androstadienedione (AD), PG, and TS by CYP68L1, but not by CYP68J5, further supporting the enzymatic activity of

A. nidulans in steroid transformation [

1,

14].

In this study, it was identified that the hydroxylating activity in

A. nidulans is rapidly inducible by specific steroids such as AD (

Figure 2). Notably, the delayed appearance of hydroxylating activity in cultures transferred to media containing AD suggests that the induction of specific enzymes is crucial for the hydroxylation process [

2]. The successful cloning of the 11-α-hydroxylase gene using SSH underscores the importance of this inducibility in identifying relevant CYP450 genes [

14,

15,

16]. Discrepancies were observed in the cDNA derived from the cloned CYP450 compared to the intron structure predicted in the database, although these findings are supported by the sequence of other CYP450s from different fungi (

Figure 3). The generation of a knockout strain for CYP68L1 revealed a complete lack of hydroxylation activity, reaffirming the role of this enzyme in the hydroxylation of AD, TS, and PG [

14]. In contrast, the expression of the patented CYP68AQ1 did not restore the hydroxylation activity of these steroids, indicating that this enzyme is not involved in the hydroxylation of the studied steroids, despite reports of some hydroxylase activity in other studies [

17] (

Figure 4 A, B, and C).

The identification of a new CYP450 (CYP68L8) in

A. ochraceus, which shares high identity with CYP68L1 (

Figure 5), further supports the notion that distinct hydroxylase activities exist within the genus

Aspergillus (

Figure 4 D and E). The ability of CYP68L8 to restore 11-α-hydroxylase activity in the knockout strain of

A. nidulans demonstrates its potential for industrial applications in steroid biotransformation [

1,

9]. The versatility of

A. nidulans as a model organism for metabolic and genetic studies [

30] and its extensive collection of mutants contribute to its significance in steroid biosynthesis research. Researchers have successfully utilized

A. nidulans to investigate human tyrosinemia and alkaptonuria [

16,

31] as well as the penicillin biosynthesis pathway [

32]. Its capability to introduce hydroxyl groups at specific sites in steroid molecules positions

Aspergillus as a key organism for industrial steroid production [

12].

Cloning the 11-α-hydroxylase gene is a crucial step toward developing an eco-friendly system capable of performing dual transformations in steroid biosynthesis. Previous attempts to clone this enzyme were unsuccessful, and whole-cell biocatalysis remains the preferred method for steroid hydroxylation [

33]. Identifying steroid 11-α-hydroxylase genes represents significant progress toward achieving efficient single-step steroid fermentation.

During the characterization of the strain deficient in 11-α-hydroxylation (KO strain), it was observed that TS was not hydroxylated [

14]. Notably, the KO strain was capable of converting AD into nearly pure TS upon expressing the enzyme 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from

C. lunatus, yielding a valuable product without generating hydroxylated byproducts (

Figure 6). However, increased concentrations of AD resulted in decreased TS production, likely due to toxic effects on

A. nidulans (

Figure 7). This finding suggests that the KO strain could serve as a model to study the production of TS by biotransformation. Future investigations may explore the potential of utilizing

A. ochraceus, which exhibits greater tolerance to elevated steroid concentrations, to enhance production efficiency [

4].

5. Conclusion

Steroid production through microbial biotransformation has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional chemical methods due to its lower environmental impact and greater efficiency. In this study, two CYP450 enzymes with 11-α-hydroxylase activity were cloned and characterized: CYP68L1 from A. nidulans and CYP68L8 from A. ochraceus. Both enzymes demonstrated the ability to hydroxylate steroids such as AD, PG, and TS. Although the patented CYP450 from A. ochraceus (CYP68AQ1 or CYP68J5) did not exhibit hydroxylating activity on these steroids, the characterization of CYP68L8 represents a significant advancement in developing single-step fermentation processes for producing hydroxylated steroids.

Additionally, the mutant strain of A. nidulans lacking 11-α-hydroxylase activity and expressing the 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from C. lunatus was able to efficiently convert AD into TS, thereby opening new opportunities for industrial TS production. The results suggest that using these strains and enzymes can optimize steroid synthesis for therapeutic and commercial applications, reducing costs and increasing production yields.

However, while TS is a valuable steroid compound used in various therapies, A. nidulans is not an ideal industrial producer due to its sensitivity to high steroid concentrations in the medium. In contrast, A. ochraceus has been recognized as an efficient industrial producer of steroids, prompting the cloning of its steroid 11-α-hydroxylase gene. This enzyme possesses similar characteristics and substrate specificity to that of A. nidulans. The next challenge will be to generate a knockout strain of A. ochraceus for this 11-α-hydroxylase enzyme to prevent hydroxylated compounds’ production and assess its feasibility for industrial-scale fermentations aimed at TS production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Alignment of genomic, database cDNA, and sequenced cDNA for CYP68L1 from A. nidulans in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization J.M.F-C, L.O-R, L.G. and A.C-A. Experiments achievement L.O-R. and J.M.F-C. Analysis and discussion of the results, as well as the manuscript writing J.M.F-C, L.G and A.C-A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the company DISBIOTEC for the support received for this work. Thanks to “Ministerio de Universidades, Real Decreto 1059/2021, de 30 de noviembre, por el que se regula la concesión directa de diversas subvenciones a las universidades participantes en el proyecto Universidades Europeas de la Comisión Europea” y “European Education and Culture Executive Agency,” Project: 101124439 — EURECA-PRO 2.0 — ERASMUS-EDU-2023-EUR-UNIV. We are also thankful to Dr. Miguel Ángel Peñalva (Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas Margarita Salas, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Madrid, Spain) for the plasmid p1660 and for technical support and advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Callow, R. The absorption spectra of oestrone and related compounds in alkaline solution. Biochem. J. 1936, 30, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Hamamura, N. Molecular and physiological approaches to understanding the ecology of pollutant degradation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003, 14, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H.; Takahashi, A.; Hotta, H.; Kato, R.; Kunishima, Y.; Takei, F.; Horita, H.; Masumori, N.; Oncology, S.M.U.U. Palonosetron with aprepitant plus dexamethasone to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting during gemcitabine/cisplatin in urothelial cancer patients. Int. J. Urol. 2015, 22, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donova, M.; Egorova, O. Microbial steroid transformations: current state and prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 1423–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambyal, K.; Singh, R. Production aspects of testosterone by microbial biotransformation and future prospects. Steroids 2020, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) - Global Strategic Business Report. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/1824157/testosterone_replacement_therapy_trt_global (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Pendharkar, G.B.; Banerjee, T.; Patil, S.; Dalal, K.S.; Chaudhari, B.L. Biotransformation of Industrially Important Steroid Drug Precursors. In Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology; Verma, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Batth, R.; Nicolle, C.; Cuciurean, I.; Simonsen, H. Biosynthesis and Industrial Production of Androsteroids. Plants-Basel 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballeira, J.; Quezada, M.; Hoyos, P.; Simeó, Y.; Hernaiz, M.; Alcantara, A.; Sinisterra, J. Microbial cells as catalysts for stereoselective red-ox reactions. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Wei, D. Identification and engineering of cholesterol oxidases involved in the initial step of sterols catabolism in Mycobacterium neoaurum. Metab. Eng. 2013, 15, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, A.; Tadra, M.; Hanc, O. Microbial Transformations Of Steroids.21. Microbial preparation of 1,4-androstadiene derivatives. Folia Microbiol. 1963, 8, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P.; Cruz, A.; Angelova, B.; Pinheiro, H.; Cabral, J. Microbial conversion of steroid compounds: recent developments. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2003, 32, 688–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petric, S.; Hakki, T.; Bernhardt, R.; Zigon, D.; Cresnar, B. Discovery of a steroid 11α-hydroxylase from Rhizopus oryzae and its biotechnological application. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 150, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-de los Ríos, L.; Luengo, J.; Fernández-Cañón, J. Steroid 11-Alpha-Hydroxylation by the Fungi Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus ochraceus. Microb. Steroids: Methods Protoc. 2017, 1645, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diatchenko, L.; Lau, Y.; Campbell, A.; Chenchik, A.; Moqadam, F.; Huang, B.; Lukyanov, S.; Lukyanov, K.; Gurskaya, N.; Sverdlov, E.; et al. Suppression subtractive hybridization: A method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 1996, 93, 6025–6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cañon, J.; Peñalva, M. Fungal Metabolic Model For Human Type-I Hereditary Tyrosinemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 1995, 92, 9132–9136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, S.; Clayton, R.; Easton, A.; Engel, L.; Messing, D.; Suzanne, B.L.; Clayton, R.A.; Easton, A.M.; Engel, L.C.; Messing, D.M.; et al. New isolated Aspergillus ochraceus 11 alpha-hydroxylase or oxidoreductase, for bioconversion of steroid substances to their 11 alpha hydroxy counterparts in heterologous cells. WO200246386-A2; AU200241768-A; US2003148420-A1; EP1352054-A2; MX2003003809-A1; CN1531590-A; US2005003473-A1; JP2005512502-W; BR200115245-A; US7033807-B2; IN200300632-P4; US7238507-B2; MX245674-B; WO200246386-A3.

- Qian, M.; Zeng, Y.; Mao, S.; Jia, L.; Hua, E.; Lu, F.; Liu, X. Engineering of a fungal steroid 11α-hydroxylase and construction of recombinant yeast for improved production of 11α-hydroxyprogesterone. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 353, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cabezón, L.; Galán, B.; García, J. Engineering Mycobacterium smegmatis for testosterone production. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Sevillano, F.; Fernández-Cañón, J. Novel phacB-encoded cytochrome P450 monooxygenase from Aspergillus nidulans with 3-hydroxyphenylacetate 6-hydroxylase and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate 6-hydroxylase activities. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.M.; Nickoloff, J.A. Escherichia coli Electrotransformation. In Electroporation Protocols for Microorganisms, Nickoloff, J.A., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 1995; pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Tilburn, J.; Scazzocchio, C.; Taylor, G.; Zabickyzissman, J.; Lockington, R.; Davies, R. Transformation by integration in Aspergillus-nidulans. Gene 1983, 26, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazopoulou, A.; Peñalva, M. Organization and Dynamics of the Aspergillus nidulans Golgi during apical extension and mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 4335–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. 1999, 95-98.

- Cytochrome P450 Homepage: https://drnelson.uthsc. 2024.

- Tang, W.; Xie, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Gong, J. Solubility of androstenedione in lower alcohols. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2014, 363, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Jia, X.; Jin, P.; Wang, Z.; Lu, F.; Liu, X. Determination of steroid hydroxylation specificity of an industrial strain Aspergillus ochraceus TCCC41060 by cytochrome P450 gene CYP68J5. Ann. Microbiol. 2020, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, F.; Hou, X.; Lin, B.; Wang, R.; Lu, F.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, B.; Liu, X. Engineering of industrial Aspergillus ochraceus strains for improved steroid 11-α-hydroxylation efficiency via overexpression of the 11-α-hydroxylase gene CYP68J5. Proceedings Of The Advances In Applied Biotechnology, 2018; 2018-01-01; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, O.P.; Qin, W.M.; Dhanjoon, J.; Ye, J.; Singh, A. Physiology and Biotechnology of Aspergillus. In Advances in Applied Microbiology, Laskin, A.I., Bennett, J.W., Gadd, G.M., Sariaslani, S., Eds.; Academic Press: 2005; Volume 58, pp. 1-75.

- Fernandez-Cañon, J.; Granadino, B.; Beltrán-Valero de Bernabé, D.; Renedo, M.; Fernandez-Ruiz, E.; Peñalva, M.; Rodríguez de Córdoba, S. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat. Genet. 1996, 14, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeso, E.; Tilburn, J.; Arst, H.; Penalva, M. Ph regulation is a major determinant in expression of a fungal penicillin biosynthetic gene. Embo J. 1993, 12, 3947–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristan, K.; Rizner, T. Steroid-transforming enzymes in fungi. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 129, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Reactions with AD and TS using WT, 11-α-hydroxylating knockout, and knockout strains with the 17-β-dehydrogenase gene from C. lunatus cloned into A. nidulans with AD and TS as substrates.

Figure 1.

Reactions with AD and TS using WT, 11-α-hydroxylating knockout, and knockout strains with the 17-β-dehydrogenase gene from C. lunatus cloned into A. nidulans with AD and TS as substrates.

Figure 2.

Appearance of 11-α-hydroxy-AD from AD in A. nidulans cultures previously grown with AD (blue) and without AD (red). The number of biological replicates is 3. The measurements were taken at a wavelength of 240 nm.

Figure 2.

Appearance of 11-α-hydroxy-AD from AD in A. nidulans cultures previously grown with AD (blue) and without AD (red). The number of biological replicates is 3. The measurements were taken at a wavelength of 240 nm.

Figure 3.

Alignment of genomic, database cDNA, and sequenced cDNA for CYP68L1 from A. nidulans in this study. The portion of the exon expansion is shown in this figure.

Figure 3.

Alignment of genomic, database cDNA, and sequenced cDNA for CYP68L1 from A. nidulans in this study. The portion of the exon expansion is shown in this figure.

Figure 4.

Chromatograms obtained from the analysis of fermentation media of the KO strain with the A) KO+CYP68L1, B) KO+CYP68J5 32ºC, C) KO+CYP68J5 37ºC, D) KO+CYP68L8 32ºC, and E) KO+CYP68L8 37ºC. Transformant at various temperatures 37 ºC (A, C, and E) and 32 ºC (B and D). The chromatograms of the culture media containing AD (blue), PG (green), and the KO strain expressing the CYP68L8 and CYP68J5 proteins (from A. ochraceus) were analyzed. The construction of the KO strain expressing CYP68L1 protein was analyzed in media with AD to verify the recovery of activity. New peaks were identified in the chromatogram results, including the 11-α-hydroxylation of AD (11-OHAD) in light blue and the 11-α-hydroxylation of PG (11-OHPG) in light green.

Figure 4.

Chromatograms obtained from the analysis of fermentation media of the KO strain with the A) KO+CYP68L1, B) KO+CYP68J5 32ºC, C) KO+CYP68J5 37ºC, D) KO+CYP68L8 32ºC, and E) KO+CYP68L8 37ºC. Transformant at various temperatures 37 ºC (A, C, and E) and 32 ºC (B and D). The chromatograms of the culture media containing AD (blue), PG (green), and the KO strain expressing the CYP68L8 and CYP68J5 proteins (from A. ochraceus) were analyzed. The construction of the KO strain expressing CYP68L1 protein was analyzed in media with AD to verify the recovery of activity. New peaks were identified in the chromatogram results, including the 11-α-hydroxylation of AD (11-OHAD) in light blue and the 11-α-hydroxylation of PG (11-OHPG) in light green.

Figure 5.

Alignment of CYP68L1 from A. nidulans with CYP68J5 (CYP68AQ1) and CYP68L8 from A. ochraceus. The identity of CYP68L1 with CYP68J5 is 36%. CYP68L1’s identity with CYP68L8 is 62%.

Figure 5.

Alignment of CYP68L1 from A. nidulans with CYP68J5 (CYP68AQ1) and CYP68L8 from A. ochraceus. The identity of CYP68L1 with CYP68J5 is 36%. CYP68L1’s identity with CYP68L8 is 62%.

Figure 6.

Chromatograms obtained from the analysis of fermentation media of A. nidulans WT strains and 11-α-hydroxylase mutant strains transformants expressing 17- β -dehydrogenase from A. nidulans and 11-α-hydroxylase mutants transformed expressing 17-β-hydrogenase from C. lunatus. Measurements of AD to TS transformation (blue) and TS to AD conversion (red). A) WT with 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from A. nidulans; B) KO with 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from A. nidulans; C) WT with 17- β -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from C. lunatus and D) KO with 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from C. lunatus.

Figure 6.

Chromatograms obtained from the analysis of fermentation media of A. nidulans WT strains and 11-α-hydroxylase mutant strains transformants expressing 17- β -dehydrogenase from A. nidulans and 11-α-hydroxylase mutants transformed expressing 17-β-hydrogenase from C. lunatus. Measurements of AD to TS transformation (blue) and TS to AD conversion (red). A) WT with 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from A. nidulans; B) KO with 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from A. nidulans; C) WT with 17- β -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from C. lunatus and D) KO with 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from C. lunatus.

Figure 7.

Chromatograms obtained from the analysis of fermentation media of 11-α-hydroxylase mutant strains transformed to express 17-β-hydrogenase from Cochliobolus lunatus. The transformation of AD to TS was measured at 0 h (green), 72 h (purple), and 120 h (orange). AD (blue) and TS (red) standards are shown. Different initial concentrations of AD were added: A) 1 g/L of AD, C) 8 g/L of AD, and E) 15 g/L of AD. For each initial concentration of AD, the area of TS production was calculated: B) 0.1 g/L of AD, D) 0.8 g/L of AD, and F) 1.5 g/L of AD.

Figure 7.

Chromatograms obtained from the analysis of fermentation media of 11-α-hydroxylase mutant strains transformed to express 17-β-hydrogenase from Cochliobolus lunatus. The transformation of AD to TS was measured at 0 h (green), 72 h (purple), and 120 h (orange). AD (blue) and TS (red) standards are shown. Different initial concentrations of AD were added: A) 1 g/L of AD, C) 8 g/L of AD, and E) 15 g/L of AD. For each initial concentration of AD, the area of TS production was calculated: B) 0.1 g/L of AD, D) 0.8 g/L of AD, and F) 1.5 g/L of AD.

Table 1.

Strains utilized in this study.

Table 1.

Strains utilized in this study.

| Strain |

Description |

Reference |

|

Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 |

Wild-type strain |

Fungal Genetics Stock Center |

|

Aspergillus nidulans ΔCYP68L1 (KO strain) |

ΔnkuA, pyroA4, ΔCYP68L1

|

[14] |

|

Aspergillus ochraceus CECT 2093 |

Wild type strain |

Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo (CECT) |

Cochliobolus lunatus

(Curvularia lunata is the anamorph) CECT2130 |

Wild type strain |

Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo (CECT) |

|

Rhizopus oryzae ATCC10404 |

Wild type strain |

Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo (CECT) |

|

Escherichia coli XL-1 blue |

recA1, endA1, gyrA96, thi-1, hsdR17, supE44, lac, F’, proAB, laclqZΔM15, Tn10, TcR

|

Stratagene |

Table 2.

Primers (red color indicates restriction sites NcoI and EcoRI).

Table 2.

Primers (red color indicates restriction sites NcoI and EcoRI).

| Gen |

Forward |

Reverse |

| CYP68L1 |

5’-cattaccatggatagcctttcgttatcaaactccatggatagcctttcgttatcaaactcc-3´ |

5´-gcgggaattcctataactgaatttcctcttttctgcg-3´ |

| CYP68L8 |

5´-cattaccatggtgctcccagtattcacgacg-3´ |

5´-gcgggaattctcatagttcaatgtcggagttttctccg-3´ |

| CYP68J5 |

5´-cattaccatggccttcttcactgggct-3´ |

5´-gcgggaattctcagcatcctggtattg-3´ |

| AN6450 |

5´-gacttccatggcgctcgccggaaaa-3´ |

5´-gcgggaattcctatgccattcccccgt-3´ |

| 17β-HSDCl

|

5´-gactcccatggcgcacgtggagaacgcct-3´ |

5´-gcgggaattcttaggcggcgccgccgtcca-3´ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).