Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

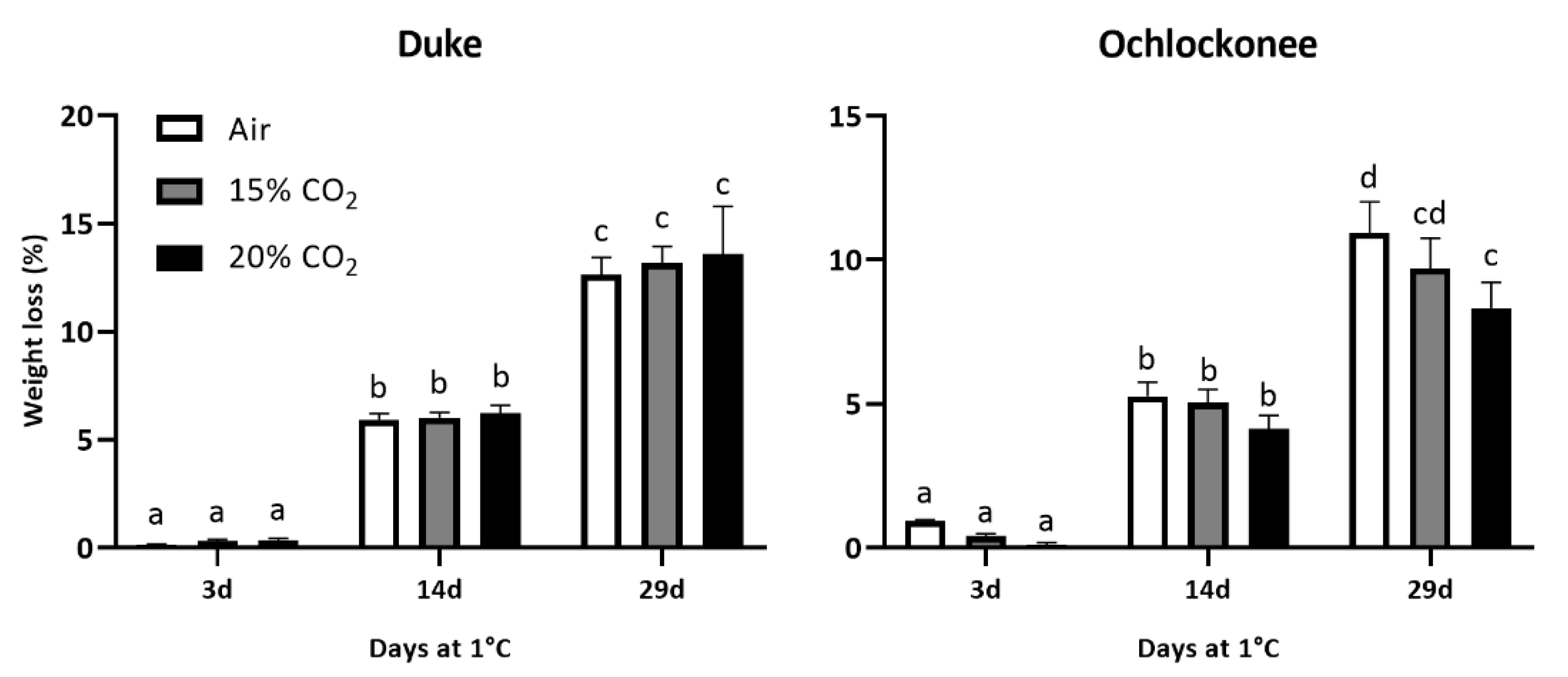

2.1. Effect of Short-Term High CO2 Treatments and Storage at 1 ºC on Blueberry Quality and Weight Losses

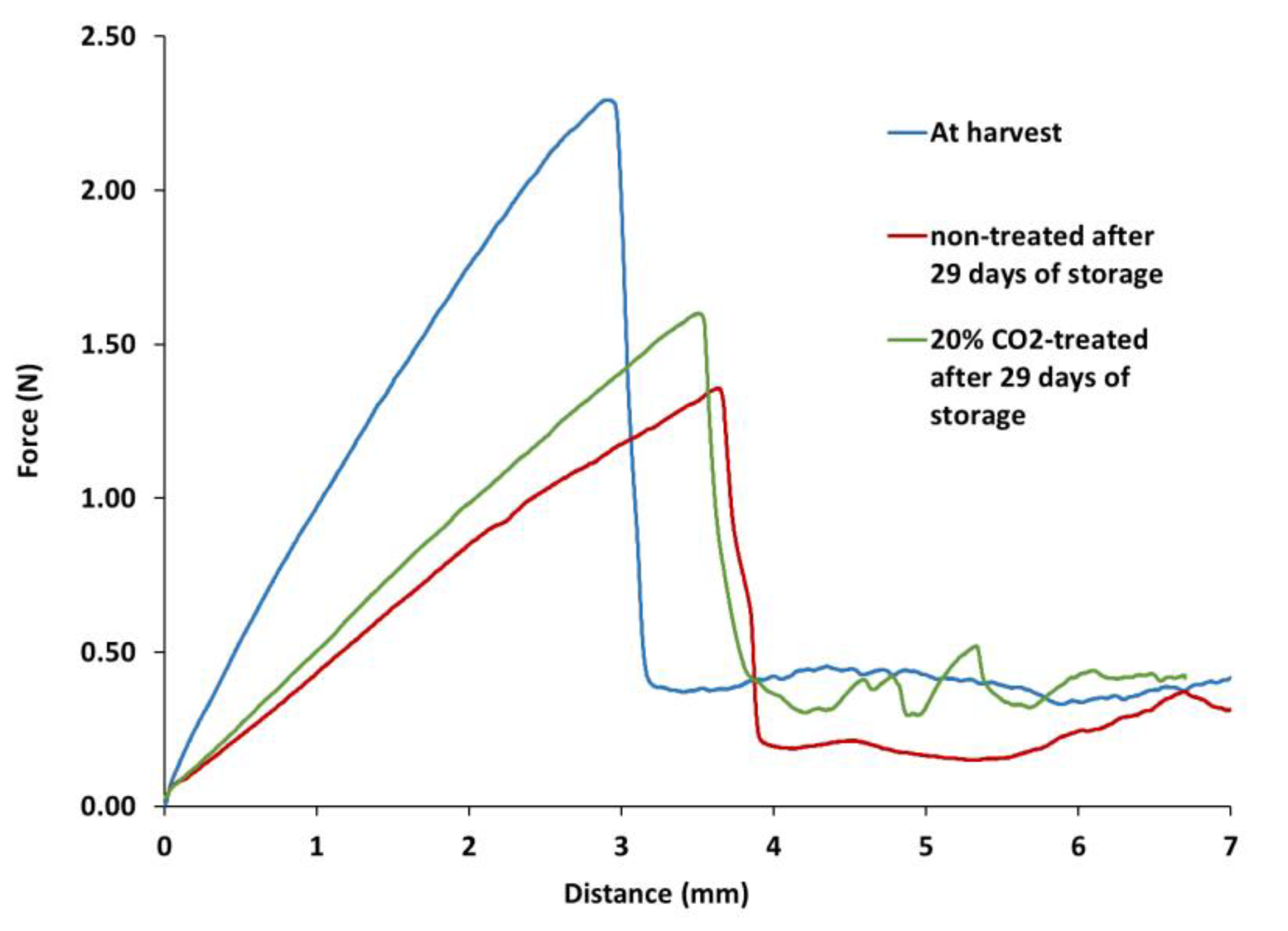

2.2. Mechanical Parameters

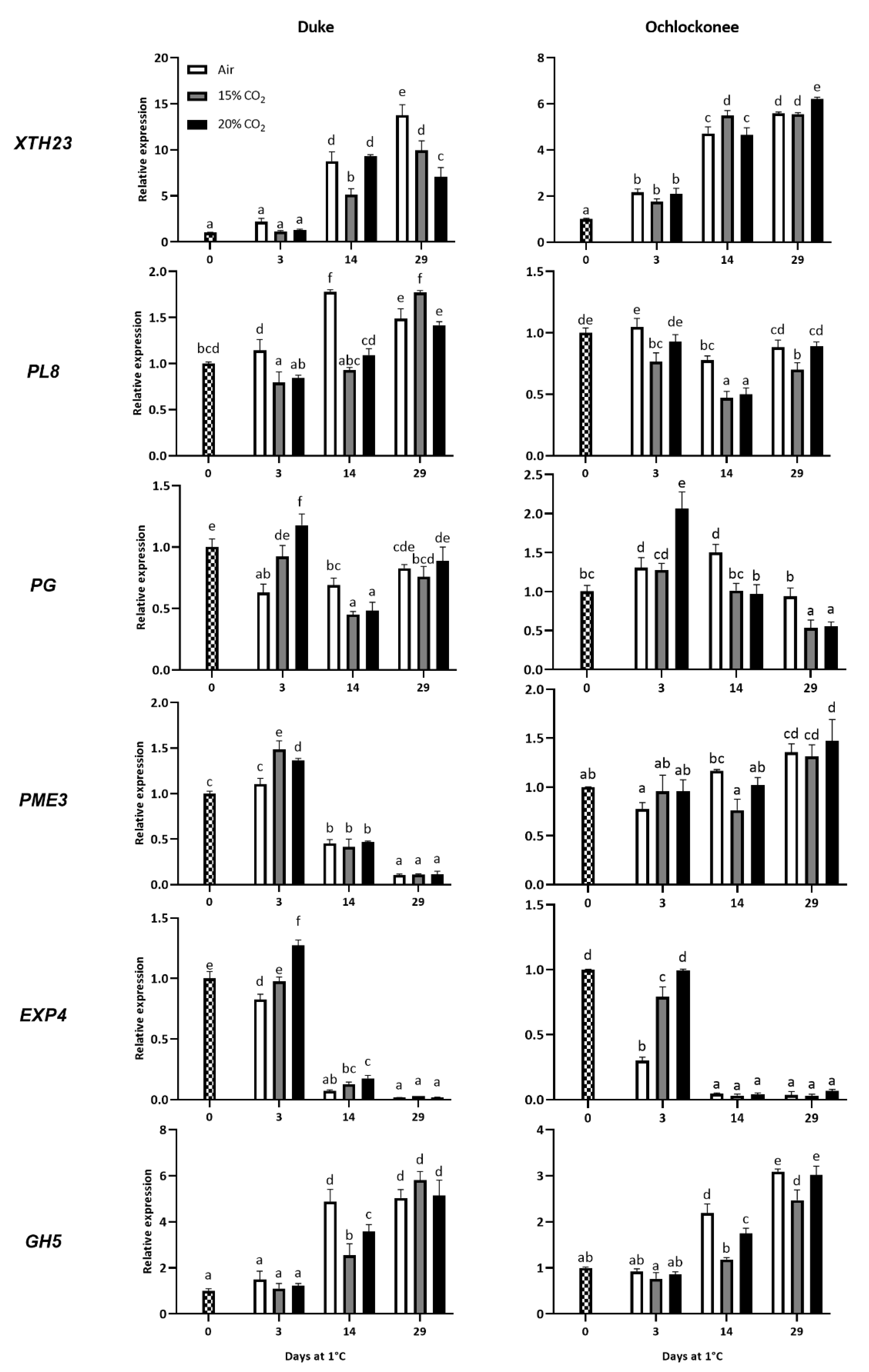

2.3. Relative Expression of Genes Encoding Cell Wall-Modifying Enzymes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Postharvest Treatments

4.2. Quality Assessments

4.3. Mechanical Properties.

4.4. Relative Gene Expression by Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tănase, E.E.; Popa, V.I.; Popa, M.E.; Geicu-Cristea, M.; Popescu, P.; Drăghici, M.; Miteluț, A.C. Identification of the most relevant quality parameters for berries-a review; Scientific Bulletin. Series F. Biotechnologies 2016, Vol XX, 222–233. [Google Scholar]

- Zorzi, M.; Gai, F.; Medana, C.; Aigotti, R.; Morello, S.; Peiretti, P.G. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of small berries. Foods 2020, 9, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvitz, S. Postharvest Handling of Berries. In Postharvest Handling; Kahramanoglu, I., Ed.; IntechOpen, Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, S.; Wei, B.; Liu, X.; Ji, S. Changes in energy metabolism accompanying pitting in blueberries stored at low temperature. Food Chem. 2014, 164, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Ryu, J.A.; Liu, R.H.; Nock, J.F.; Watkins, C.B. Harvest maturity, storage temperature and relative humidity affect fruit quality, antioxidant contents and activity, and inhibition of cell proliferation of strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 49, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, M.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C. Water distribution and ionic balance in response to high CO2 treatments in strawberries (Fragaria vesca L. cv. Mara de Bois). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 73, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Colás-Medà, P.; Abadías, M.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I.; Bobo, G.; Viñas, I. Strategies to reduce microbial risk and improve quality of fresh and processed strawberries: A review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 52, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.S.; Fu, D.Q.; Zhong, C.F.; Zong, J.; Zhou, J.H.; Chang, H.; Wang, B.G.; Wang, Y.X. Transcriptome combined with long non-coding RNA analysis reveals the potential molecular mechanism of high-CO2 treatment in delaying postharvest strawberry fruit ripening and senescence. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2024, 323, 112505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagán, N.; Miclo, T.; Terry, L.A. Graduated controlled atmosphere: A novel approach to increase “Duke” blueberry storage life. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, C.F.; Jordan, M.A.; Pennell, K.M.; Fillmore, S. Controlled atmosphere storage impacts fruit quality and flavor chemistry of five cultivars of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 194, 112073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrke, T.; Cvelbar Weber, N.; Razinger, J.; Medic, A.; Veberic, R.; Hudina, M.; Jakopic, J. Short-term storage in a modified atmosphere affects the chemical profile of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) fruit. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Alvarez, I.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Romero, I. Effect of high CO2 levels and low temperature on stilbene biosynthesis pathway gene expression and stilbenes production in white, red and black table grape cultivars during postharvest storage. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappai, F.; Amadeu, R.R.; Benevenuto, J.; Cullen, R.; Garcia, A.; Grossman, A.; Ferrão, L.F. V.; Munoz, P. High-resolution linkage Map and QTL analyses of fruit firmness in autotetraploid blueberry. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 562171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, S.; Giongo, L.; Cappai, F.; Kerckhoffs, H.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Hutchins, D.; East, A. Blueberry firmness - A review of the textural and mechanical properties used in quality evaluations. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 192, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giongo, L.; Ajelli, M.; Pottorff, M.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Iorizzo, M. Comparative multi-parameters approach to dissect texture subcomponents of highbush blueberry cultivars at harvest and postharvest. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 183, 111696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, C.F.; Jordan, M.A.; Nicholas, K.U.K.G. Effect of CO2 on physical, chemical, and quality changes in “Burlington” blueberries. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae; 2003; 600. 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giongo, L.; Poncetta, P.; Loretti, P.; Costa, F. Texture profiling of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) during fruit development, ripening and storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 76, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.; Kerckhoffs, H.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Hutchins, D.; East, A. Influence of harvest maturity and storage technology on mechanical properties of blueberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 191, 111961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Marti-Anders, C.; Álvarez, M.D.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Romero, I. Are the blueberries we buy good quality? Comparative study of berries purchased from different outlets. Foods 2023, 12, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, P.; Zepeda, B.; Rojas, B.; Silva-Sanzana, C.; Delgado-Rioseco, J.; Fernández, K.; Balic, I.; Arriagada, C.; Moreno, A.A.; Defilippi, B.G.; et al. Cell wall calcium and hemicellulose have a role in the fruit firmness during storage of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.). Plants 2021, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Ma, F.; Shi, S.; Qi, X.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, J. Changes and postharvest regulation of activity and gene expression of enzymes related to cell wall degradation in ripening apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 56, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Lin, M.; Li, H.; Yuan, F.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, J. Effects of paper containing 1-MCP postharvest treatment on the disassembly of cell wall polysaccharides and softening in Younai plum fruit during storage. Food Chem. 2018, 264, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappai, F.; Benevenuto, J.; Ferrão, L.F. V.; Munoz, P. Molecular and genetic bases of fruit firmness variation in blueberry—a review. Agronomy 2018, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.G.; Sutherland, P.W.; Johnston, S.L.; Gunaseelan, K.; Hallett, I.C.; Mitra, D.; Brummell, D.A.; Schröder, R.; Johnston, J.W.; Schaffer, R.J. Down-regulation of POLYGALACTURONASE1 alters firmness, tensile strength and water loss in apple (Malus x domestica) fruit. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paniagua, C.; Blanco-Portales, R.; Barceló-Muñoz, M.; García-Gago, J.A.; Waldron, K.W.; Quesada, M.A.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.; Mercado, J.A. Antisense down-regulation of the strawberry β-galactosidase gene FaβGal4 increases cell wall galactose levels and reduces fruit softening. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Casado, G.; Sánchez-Raya, C.; Ric-Varas, P.D.; Paniagua, C.; Blanco-Portales, R.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.; Pose, S.; Matas, A.J.; Mercado, J.A. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the polygalacturonase FaPG1 gene improves strawberry fruit firmness. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Dai, H.; Wang, S.; Ji, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q. Putrescine treatment delayed the softening of postharvest blueberry fruit by inhibiting the expression of cell wall metabolism key gene VcPG1. Plants 2022, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Hu, W.; Xiu, Z.; Yang, X.; Guan, Y. Integrated transcriptomics-proteomics analysis reveals the regulatory network of ethanol vapor on softening of postharvest blueberry. LWT 2023, 180, 114649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Maldonado, R.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C. Expression of class I chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase genes and postharvest fungal decay control of table grapes by high CO2 pretreatment. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 41, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Suárez Valles, B.; Campa Negrillo, A.; Ferreira Fernández, J.J. Physicochemical characterization of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) juices from 55 cultivars grown in northern Spain. Acta Aliment. 2019, 48, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Kim, H.L.; Kim, S.J.; Park, K.S. Fruit quality, anthocyanin and total phenolic contents, and antioxidant activities of 45 blueberry cultivars grown in Suwon, Korea. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2013, 14, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, R. Blueberry quality characteristics and how they can be optimized. In Annual Report of the Michigan State Horticultural Society, 122nd ed.; 1992; pp. 140–145. Available online: https://www.researchgate. 2857. [Google Scholar]

- Almenar, E.; Samsudin, H.; Auras, R.; Harte, B.; Rubino, M. Postharvest shelf life extension of blueberries using a biodegradable package. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Hu, W.; Jiang, A.; Xiu, Z.; Liao, J.; Yang, X.; Guan, Y.; Saren, G.; Feng, K. Effect of ethanol treatment on the quality and volatiles production of blueberries after harvest. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 6296–6306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiabrando, V.; Giacalone, G. Shelf-life extension of highbush blueberry using 1-methylcyclopropene stored under air and controlled atmosphere. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.; Guerra, M.; Daniel, P.; Camelo, A.L.; Yommi, A. Quality changes of highbush blueberries fruit stored in CA with different CO2 levels. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, S154–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftner, R.; Polashock, J.; Ehlenfeldt, M.; Vinyard, B. Instrumental and sensory quality characteristics of blueberry fruit from twelve cultivars. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 49, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggia, C.; Graell, J.; Lara, I.; González, G.; Lobos, G.A. Firmness at harvest impacts postharvest fruit softening and internal browning development in mechanically damaged and non-damaged highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, R.; Romero, I.; Fernandez-Caballero, C.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T. Low temperature and short-term high-CO2 treatment in postharvest storage of table grapes at two maturity stages: Effects on transcriptome profiling. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I.; Domínguez, I.; Doménech-Carbó, A.; Gavara, R.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T. Effect of high levels of CO2 on the electrochemical behavior and the enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems in black and white table grapes stored at 0 °C. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 6859–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schotsmans, W.; Molan, A.; MacKay, B. Controlled atmosphere storage of rabbiteye blueberries enhances postharvest quality aspects. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 44, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggia, C.; Graell, J.; Lara, I.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Thomas-Valdés, S.; Lobos, G.A. Fruit characteristics and cuticle triterpenes as related to postharvest quality of highbush blueberries. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2016, 211, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A.C.; East, A.R.; Heyes, J.A. Interaction of temperature control deficiencies and atmosphere conditions during blueberry storage on quality outcomes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 95, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.; Kerckhoffs, H.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Hutchins, D.; East, A. Influence of water loss on mechanical properties of stored blueberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 176, 111498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, V.; Giacalone, G.; Rolle, L. Mechanical behaviour and quality traits of highbush blueberry during postharvest storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummell, D.A.; Harpster, M.H. Cell wall metabolism in fruit softening and quality and its manipulation in transgenic plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 47, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chea, S.; Yu, D.J.; Park, J.; Oh, H.D.; Chung, S.W.; Lee, H.J. Fruit softening correlates with enzymatic and compositional changes in fruit cell wall during ripening in ‘Bluecrop’ highbush blueberries. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2019, 245, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posé, S.; Paniagua, C.; Matas, A.J.; Gunning, A.P.; Morris, V.J.; Quesada, M.A.; Mercado, J.A. A nanostructural view of the cell wall disassembly process during fruit ripening and postharvest storage by atomic force microscopy. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 87, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Hao, D.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G.; Pei, J.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effect of chitosan/thyme oil coating and UV-C on the softening and ripening of postharvest blueberry fruits. Foods 2022, 11, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shang, F.; Niu, B.; Wu, W.; Han, Y.; Chen, H.; Gao, H. Melatonin treatment delays the softening of blueberry fruit by modulating cuticular wax metabolism and reducing cell wall degradation. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miedes, E.; Herbers, K.; Sonnewald, U.; Lorences, E.P. Overexpression of a cell wall enzyme reduces xyloglucan depolymerization and softening of transgenic tomato fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5708–5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Bertomeu, J.; Miedes, E.; Lorences, E.P. Expression of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) genes and XET activity in ethylene treated apple and tomato fruits. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witasari, L.D.; Huang, F.C.; Hoffmann, T.; Rozhon, W.; Fry, S.C.; Schwab, W. Higher expression of the strawberry xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase genes FvXTH9 and FvXTH6 accelerates fruit ripening. Plant J. 2019, 100, 1237–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ban, Q.; Li, H.; Hou, Y.; Jin, M.; Han, S.; Rao, J. DkXTH8, a novel xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase in persimmon, alters cell wall structure and promotes leaf senescence and fruit postharvest softening. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Olmo, I.; Romero, I.; Alvarez, M.D.; Tarradas, R.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C. Transcriptomic analysis of CO2-treated strawberries (Fragaria vesca) with enhanced resistance to softening and oxidative stress at consumption. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 983976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Doménech, N.; Jiménez-Bemúdez, S.; Matas, A.J.; Rose, J.K.C.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.; Mercado, J.A.; Quesada, M.A. Antisense inhibition of a pectate lyase gene supports a role for pectin depolymerization in strawberry fruit softening. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2769–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, Q.; Feng, Y.; Tang, P.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Hu, C.; Wang, Y.; Cui, B.; Xie, X.; et al. Gene-specific silencing of SlPL16, a pectate lyase coding gene, extends the shelf life of tomato fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 201, 112368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yeats, T.H.; Uluisik, S.; Rose, J.K.C.; Seymour, G.B. Fruit Softening: Revisiting the Role of Pectin. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, F.; Ji, S. Ethylene plays an important role in the softening and sucrose metabolism of blueberries postharvest. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, B. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing a grass PpEXP1 gene exhibit enhanced tolerance to heat stress. PLoS One 2014, 9, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, G.; An, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Overexpression of the wheat expansin gene TaEXPA2 improves oxidative stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 124, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W. Over-expression of TaEXPB23, a wheat expansin gene, improves oxidative stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 173, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Wu, C.; Ma, L.; Fu, A.; Zheng, Y.; Han, J.; Li, C.; Yuan, S.; Zheng, S.; Gao, L.; et al. Transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provide insights into postharvest ripening and senescence of tomato fruit under low temperature. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittarelli, A.; Santiago, M.; Morales, A.; Meisel, L.A.; Silva, H. Isolation and functional characterization of cold-regulated promoters, by digitally identifying peach fruit cold-induced genes from a large EST dataset. BMC Plant Biol. 2009, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z.; Yu, H.; Chen, Q. Comparison and Improvement of Different Methods of RNA Isolation from Strawberry (Fragria * ananassa). J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 4, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Duke | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSC (⁰Brix) |

TA (% citric acid) |

MI (SSC/TA) |

pH | Decay index (%) |

||

| At harvest | 9.17 ± 0.38 b | 0.87 ± 0.01 b | 10.58 ± 0.51 c | 2.82 ± 0.01 a | 0000 ̶ | |

| Air | 3 d | 8.20 ± 0.17 a | 1.03 ± 0.02 e | 07.96 ± 0.26 a | 2.96 ± 0.06 bc | 0000 ̶ |

| 29 d | 9.60 ± 0.00 b | 0.66 ± 0.01 a | 14.47 ± 0.13 d | 3.24 ± 0.02 d | 5.70 ± 0.04 c | |

| 15% CO2 | 3 d | 8.37 ± 0.32 a | 1.06 ± 0.02 f | 07.92 ± 0.39 a | 2.89 ± 0.04 ab | 0000 ̶ |

| 29 d | 8.30 ± 0.10 a | 0.95 ± 0.01 d | 08.71 ± 0.15 ab | 2.95 ± 0.02 bc | 4.43 ± 0.01 b | |

| 20% CO2 | 3 d | 8.37 ± 0.25 a | 0.92 ± 0.01 c | 09.06 ± 0.32 b | 3.01 ± 0.02 c | 0000 ̶ |

| 29 d | 8.43 ± 0.31 a | 0.85 ± 0.00 b | 09.92 ± 0.36 c | 3.01 ± 0.01 c | 2.35 ± 0.02 a | |

| Ochlockonee | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSC (⁰Brix) |

TA (% citric acid) |

MI (SSC/TA) |

pH | Decay index (%) |

||

| At harvest | 12.67 ± 0.12 a | 0.34 ± 0.02 b | 37.70 ± 1.95 c | 2.81 ± 0.01 b | 0000 ̶ | |

| Air | 3 d | 12.70 ± 0.00 a | 0.45 ± 0.01 e | 28.44 ± 0.37 a | 2.85 ± 0.01 c | 0000 ̶ |

| 29 d | 13.87 ± 0.12 c | 0.44 ± 0.01 de | 31.53 ± 0.96 ab | 2.87 ± 0.02 cd | 2.03 ± 0.02 c | |

| 15% CO2 | 3 d | 13.30 ± 0.10 b | 0.32 ± 0.01 ab | 41.15 ± 1.00 c | 2.87 ± 0.01 cd | 0000 ̶ |

| 29 d | 13.33 ± 0.06 b | 0.30 ± 0.02 a | 45.03 ± 2.55 d | 2.89 ± 0.01 d | 1.62 ± 0.02 b | |

| 20% CO2 | 3 d | 13.20 ± 0.00 b | 0.39 ± 0.02 c | 34.20 ± 1.80 b | 2.76 ± 0.01 a | 0000 ̶ |

| 29 d | 12.70 ± 0.00 a | 0.41 ± 0.01 cd | 30.99 ± 0.76 ab | 2.79 ± 0.03 ab | 0.39 ± 0.01 a | |

| Duke | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Skin Breaking Force (N) |

Slope at Skin Breaking (N/mm) |

Displacement at Skin Breaking (mm) | Skin Breaking Work (mJ) |

||

| At harvest | 1.95±0.18 cd | 0.60±0.05 d | 3.23±0.28 a | 4.97±0.59 bcd | |

| Air | 3 d | 2.07±0.16 d | 0.68±0.06 e | 3.03±0.28 a | 5.39±0.54 d |

| 14 d | 1.91±0.16 cd | 0.63±0.06 de | 3.02±0.29 a | 5.17±0.49 bcd | |

| 29 d | 1.36±0.13 a | 0.29±0.03 a | 4.75±0.79 c | 4.25±0.63 a | |

| 15% CO2 | 3 d | 1.85±0.17 bc | 0.61±0.05 d | 3.02±0.25 a | 5.21±0.39 cd |

| 14 d | 1.69±0.21 b | 0.57±0.05 cd | 2.92±0.28 a | 4.77±0.47 abc | |

| 29 d | 1.69±0.16 b | 0.41±0.04 b | 4.09±0.40 b | 5.08±0.48 bcd | |

| 20% CO2 | 3 d | 1.68±0.13 b | 0.54±0.05 c | 3.04±0.27 a | 4.61±0.45 ab |

| 14 d | 1.77±0.16 bc | 0.54±0.05 c | 3.22±0.28 a | 4.88±0.46 bcd | |

| 29 d | 1.71±0.18 b | 0.40±0.04 b | 4.26±0.44 b | 5.08±0.52 bcd | |

| Ochlockonee | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Skin Breaking Force (N) |

Slope at Skin Breaking (N/mm) |

Displacement at Skin Breaking (mm) | Skin Breaking Work (mJ) |

||

| At harvest | 1.43±0.12 ab | 0.49±0.04 c | 2.91±0.26 a | 3.92±0.40 ab | |

| Air | 3 d | 1.51±0.15 b | 0.56±0.05 d | 2.68±0.28 a | 4.27±0.41 b |

| 14 d | 1.45±0.17 ab | 0.41±0.03 b | 3.51±0.50 b | 3.91±0.52 ab | |

| 29 d | 1.41±0.19 ab | 0.38±0.06 ab | 3.78±0.59 bc | 3.75±0.61 ab | |

| 15% CO2 | 3 d | 1.35±0.13 ab | 0.54±0.05 cd | 2.49±0.24 a | 3.76±0.40 ab |

| 14 d | 1.45±0.19 ab | 0.41±0.06 b | 3.51±0.45 b | 3.76±0.59 ab | |

| 29 d | 1.34±0.23 a | 0.33±0.07 a | 4.15±0.74 c | 3.59±0.71 a | |

| 20% CO2 | 3 d | 1.50±0.15 ab | 0.55±0.05 d | 2.69±0.29 a | 4.23±0.39 b |

| 14 d | 1.39±0.17 ab | 0.39±0.05 ab | 3.56±0.38 b | 3.79±0.59 ab | |

| 29 d | 1.35±0.20 ab | 0.39±0.08 ab | 3.53±0.53 b | 3.61±0.61 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).