1. Introduction

Today, in the rapid development of the industrial era, such as transportation, maritime, aviation, chemical, and others. The use of ferrous-based materials is increasingly varied, making joining dissimilar metals more massive. Welding dissimilar materials is more complicated than welding similar materials because the procedure must be used in areas where specific attributes are to be improved [

1,

2,

3]. AISI 1037 is a carbon steel primarily used for its moderate strength and machinability. AISI 304 is stainless steel well-regarded for its corrosion resistance, making it suitable for various applications where exposure to corrosive elements is a concern. The process of joining these two materials can be classified as dissimilar welding because of the difference in composition [

4].

The main challenge of dissimilar welding is the difference in physical and mechanical properties such as melting point, material composition, filler metal, thermal conductivity, metallurgical structure, and corrosion resistance of the two used materials [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The large variety of elements in the two materials joined will be difficult to avoid the formation of intermetallic compounds [

9] [

6,

10]. The Intermetallic phase of the compound is generally hard and brittle, which causes failure in the welded joint [

6].

Temperature has an important contribution in determining the behaviour of steel. Steel tends to become brittle at low temperatures, resulting in decreased ductility. The "Ductile to Brittle Transition Temperature" is the temperature at which the drop in toughness takes place [

11]. Ductile to Brittle Transition Temperature phenomena can be tested using the notched-bar impact method. Since the fracture is ductile in such a transition, the impact energy becomes quite high at higher temperatures. As the temperature is dropped, the fracture becomes more brittle, and the impact energy decreases across a limited temperature range. The transition can also be detected in the fracture surfaces, exhibiting granular surfaces for completely brittle fracture and fibrous or dull surfaces for completely ductile fracture. The characteristics of both types will be present over the ductile-to-brittle transition.

For many materials, the transition may place across a wide range of temperatures. However, the change can suddenly occur for pure materials at a specific temperature. At transition temperatures, the ferrite steels' fracture toughness significantly changes. Steel cleaves and becomes brittle at low temperatures. Steel is ductile at high temperatures and fails through plastic collapse and micro coalescence. At normal temperatures, dislocation motion causes plastic deformation in metals. The amount of stress required to displace a dislocation depends on factors such as atomic bonding, crystal structure, and obstacles including solute atoms, grain borders, precipitate particles, and other dislocations. Instead, the metal will break into widely spaced cracks, and if the tension needed to realign the dislocation is too great, the failure will be brittle. Thus, depending on which mechanism calls for the lowest applied stress, a ductile failure or crack a brittle failure will occur [

11,

12,

13].

This study aims to investigate the influence of preheating on the mechanical properties of welded joints made from AISI 304 stainless steel and AISI 1037 carbon steel using Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW). Preheating, a commonly employed technique in welding to minimize thermal stress and enhance fusion between dissimilar materials, is expected to significantly affect the weld quality and overall joint performance, particularly when dealing with stainless steel and carbon steel.

To evaluate these effects, two primary mechanical tests will be conducted: hardness testing and impact testing. The hardness test will measure the material's resistance to deformation, providing critical insights into the strength distribution and uniformity across the weld and heat-affected zones. Conversely, the impact test will assess the weld's toughness, determining the amount of energy the material can absorb prior to fracturing. These tests are crucial in determining whether preheating improves the mechanical performance of the joint, particularly regarding its strength, toughness, and durability

Additionally, fracture surface analysis will be performed on the tested specimens to visually assess the quality of the welds and the fracture behaviour. This will allow for the identification of any improvements in fracture consistency, as well as the potential reduction in defects such as cracks, voids, or brittle failures. By integrating the results from these mechanical tests with fracture surface observations, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how preheating affects the performance and reliability of dissimilar metal welds.

2. Literature Review

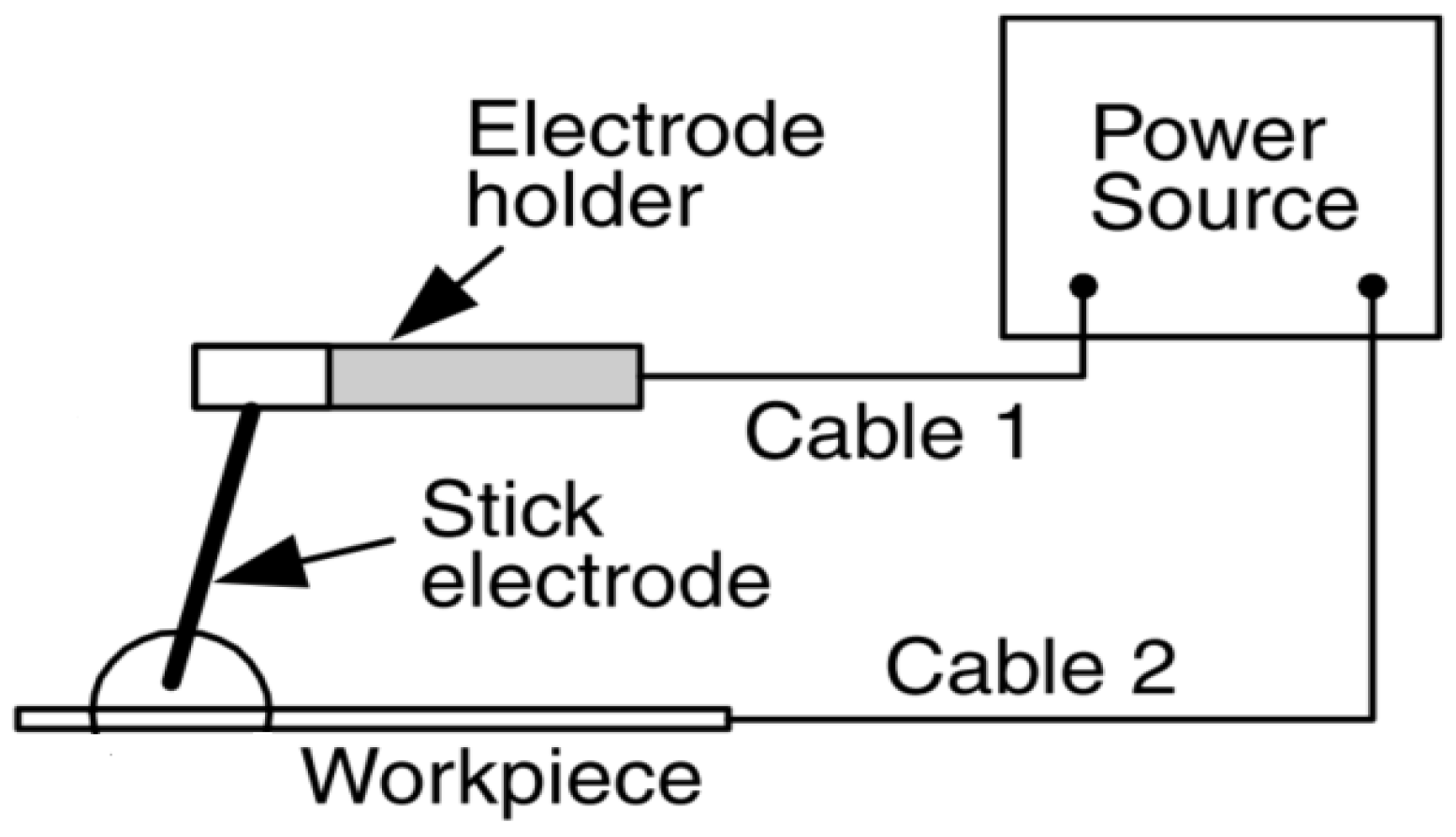

Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW), also known as stick welding, is a manual arc welding process where a consumable electrode, coated in flux, is used to join metals by producing a weld. The flux coating on the electrode serves multiple purposes it shields the molten weld pool from atmospheric contamination, stabilizes the arc, and adds alloying elements to the weld. Recent developments in welding technologies have continued to enhance the capabilities of SMAW, making it even more relevant in today's manufacturing and construction sectors despite the emergence of more advanced processes.

One of the reasons SMAW remains widely used is its versatility and adaptability. It is compatible with a wide range of materials, including carbon steels, stainless steels, and alloyed metals, which makes it a popular choice for various industries. In recent years, improvements in consumable electrode design have expanded its applicability to more complex materials, including high-strength steels and corrosion-resistant alloys. This has allowed SMAW to maintain its relevance even in industries that demand higher-quality and stronger welds, such as in pressure vessel construction, shipbuilding, and pipeline welding.

Furthermore, advancements in portable welding power sources have enhanced the portability of SMAW equipment, making it a preferred option for fieldwork and on-site repairs. Modern inverter-based welding machines are more compact, energy-efficient, and capable of delivering more stable arcs, even in difficult welding positions. This has improved weld quality and consistency in outdoor environments where fluctuating conditions, such as wind or temperature, can otherwise compromise weld integrity.

SMAW's ease of use is another factor that has contributed to its sustained popularity. Recent training programs and certification efforts have focused on enhancing welders’ skills and knowledge, ensuring that even as technology advances, the welding process remains accessible to a wide range of technicians and workers. The development of better safety equipment and personal protective gear has also made SMAW safer and more ergonomic for operators, reducing the risks associated with manual welding processes.

In comparison to newer welding technologies like Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW) or Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), SMAW continues to offer cost-effectiveness. The process does not require external shielding gases, and the equipment and consumables are relatively inexpensive, which is advantageous for smaller operations or field applications with limited resources. This economic advantage, combined with recent developments in electrode technology, welding machines, and safety measures, has allowed SMAW to remain competitive in a market where automation and robotics are increasingly prevalent.

In summary, while more sophisticated and automated welding methods have been developed, SMAW continues to be a vital process due to ongoing improvements in equipment, electrode design, and welder training. These advancements ensure that SMAW remains a reliable, versatile, and cost-effective option for industries requiring durable welds across a variety of materials and conditions. The SMAW schematic can be seen on the

Figure 1.

In Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW), several parameters are crucial for determining the quality of the welding joint [

2,

15,

16]. The welding current must be properly set to ensure adequate penetration and fusion; too high a current can led to excessive spatter and burn-through, while too low a current can cause incomplete fusion and weak joints. The arc length, or the distance between the electrode tip and the workpiece, affects the stability of the arc and the quality of the weld, with a consistent, optimal arc length producing a uniform bead. The electrode angle influences the direction and stability of the arc as well as the shape and penetration of the weld bead; incorrect angles can lead to defects such as undercutting or lack of fusion. The travel speed at which the electrode is moved along the joint affects bead shape and penetration; too fast a speed can result in a narrow, shallow weld, while too slow a speed can produce a wide, convex bead with excessive reinforcement and possible slag inclusion. The correct choice of electrode type and size is essential for achieving the desired weld properties, including strength, toughness, and resistance to cracking. The choice of polarity, whether direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC), affects penetration, bead shape, and arc stability, making it important to select the appropriate polarity for the electrode and base material. Proper cleaning and preparation of the base material, including the removal of rust, paint, oil, and other contaminants, are vital to prevent defects such as porosity and inclusions. Additionally, the total heat input, which is a function of current, voltage, and travel speed, influences the metallurgical properties of the weld and the heat-affected zone (HAZ), requiring careful control to avoid issues such as distortion, cracking, and changes in mechanical properties. Lastly, environmental conditions like wind, humidity, and temperature can impact the welding process; for instance, excessive wind can disrupt the shielding gas, leading to porosity, while extreme temperatures can affect the welder's ability to control the weld pool. By carefully monitoring and controlling these parameters, welders can produce high-quality welds with the desired mechanical properties and minimal defects.

2. Materials and Methods

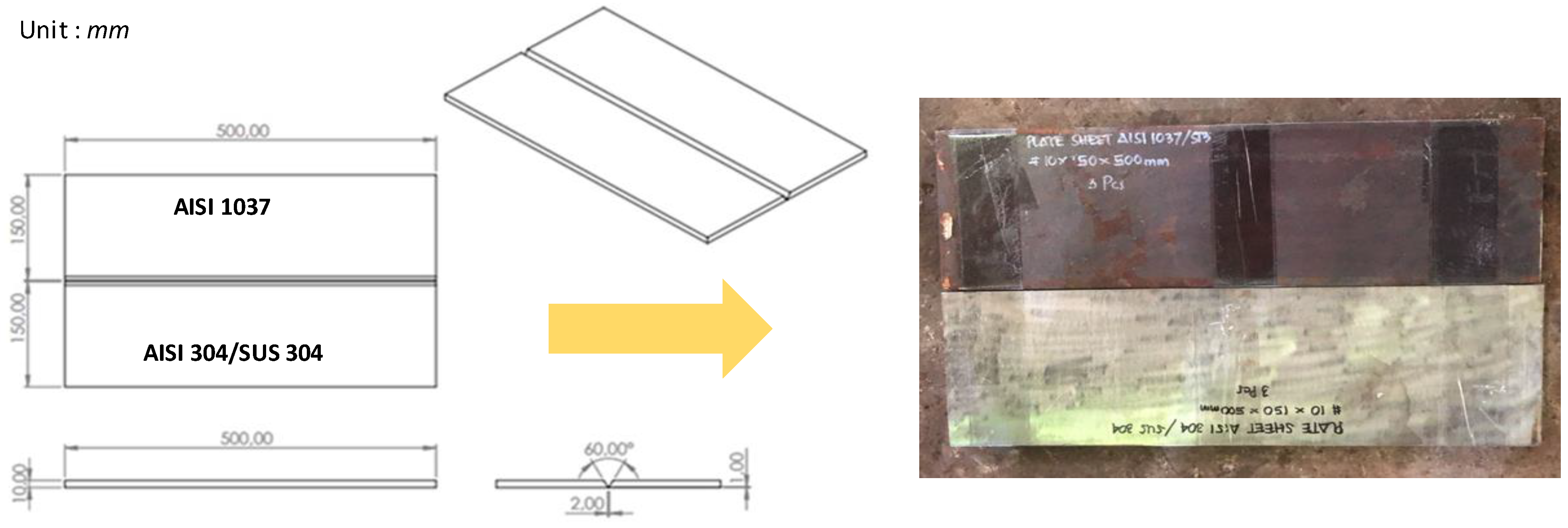

Two types of steel were selected for this study: AISI 304 stainless steel and AISI 1037 carbon steel. Each was provided in plate form with dimensions of 500 mm x 150 mm x 10 mm. The nominal chemical compositions of these materials prior to welding are detailed in Table 1. Careful selection of materials ensures accurate representation of typical industrial welding scenarios. The plates were joined using the Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW) technique. An E309-16 electrode, compatible with dissimilar metal welding of stainless and carbon steels, was employed. The welding operation utilized a current of 115 Amperes. For preparation, a single V-Groove joint configuration was applied to facilitate proper penetration and fusion of the weld metal across the joint interface. To mitigate the risk of thermal stresses and improve the weld quality, preheating was applied uniformly across the joint area. The preheating temperatures varied at 150°C, 200°C, 250°C, and 300°C, with each temperature maintained for a duration of 15 minutes prior to the commencement of welding. This treatment helps in reducing the cooling rate, thereby minimizing the risk of crack formation in the welded zones. Preheating in this experiment was carried out using a torch.

Post-welding, specimens were fabricated from the welded plates to meet the requirements of the JIS Z2242 standard for impact testing. Tests were conducted using a Charpy impact tester, specifically the CL-30 model, under ambient conditions. This analysis was pivotal in assessing the toughness and energy absorption characteristics of the welded joints. The influence of welding and heat exposure on the hardness profile was evaluated using the Vickers hardness method. Measurements were performed with a Vickers hardness tester, the VKH-2E model, across sections of the welded joint. This analysis provided a comprehensive profile of hardness changes induced by the thermal welding cycle. The microstructural properties of the welded joints were characterized through metallographic techniques. Different etchants were applied based on the materials: 3% Nital for AISI 1037 carbon steel and Aqua Regia for the weld zone and AISI 304 stainless steel. These etchants reveal microstructural features by selectively corroding the surfaces. Observations were conducted using a Keyence VH-Z450 optical microscope, as well as a high-resolution Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM), Thermo Scientific Quattro S model, to capture detailed images of the microstructure, aiding in understanding the phase transformations and grain structure modifications post-welding.

Figure 2 shows the size and the welded specimen.

3. Results and Discussion

The test results through X-ray fluorescence (XRF) were carried out to obtain chemical composition in three zones, consisting of AISI 1037 carbon steel base metal, AISI 304 stainless steel base metal, and fusion zone.

The base metal composition of AISI 1037 carbon steel detects five elements, as shown in

Table 1. The main alloying element obtained is Mn (0.631%). The Mn content in carbon steel can contribute to increasing the hardness value of the material. Some elements in the 304 stainless steel base metal zone contain percentages detected by the XRF tool. The main alloying element was obtained is Cr (18.07%). The Cr content significantly influences the corrosion resistance properties of stainless steel. In addition, Cr also increases toughness and the ability to be hardened. The second main alloying element is Ni (8.08%). Nickel itself increases toughness, increases corrosion resistance, and reduces stress corrosion cracking [

17]. Indicates the XRF result in the obtained fusion zone. The amount of Cr content detected is 23.64%, the most significant amount of alloy composition. On the other hand, the minimum alloying element detected is Sb, with the amount (11.59%). The high concentration of chromium alloys is believed to come from the incoming alloying elements due to filler (E309-16) used during welding.

Impact testing on welded joints is carried out to investigate the impact strength or toughness of welded joints by calculating the amount of impact energy absorbed during the test process until a fracture occurs. The toughness of a material represents the material's ability to withstand fractures caused by the presence of a notch or a stress concentration. Temperature changes play an essential role in determining the toughness value of steel [

18]. In this work, Impact testing was carried out at four preheating treatment conditions consisting of 150 ºC, 200 ºC, 250 ºC, 300 ºC, and non-heat treatment before welding was performed.

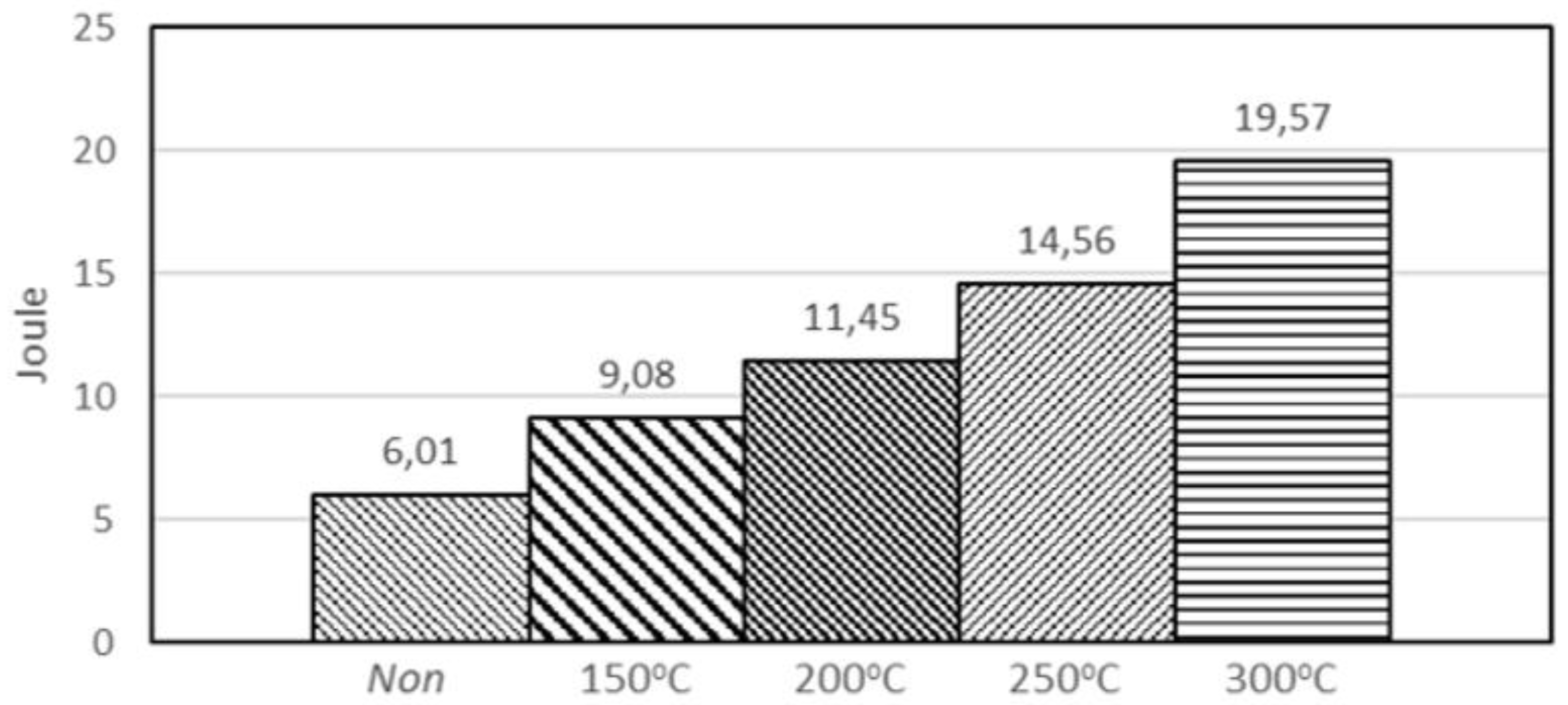

3.1. Impact Strength Weld Joints

The impact testing results through the Charpy method showed that SS304 and AISI 1037 welded joints increased with preheating temperature to 300ºC, as shown in the

Figure 3. The impact test results clearly demonstrate the correlation between preheating temperature and the toughness of the SS 304 and AISI 1037 steel joining. As the preheating temperature increases, the impact energy absorbed by the material also increases, indicating enhanced toughness. This can be explained through the lens of the ductile-to-brittle transition (DBTT) diagram and the concept of impact strength.

Impact strength refers to a material's ability to absorb energy upon sudden impact. A material with higher impact strength can withstand greater impact forces without experiencing significant damage or deformation. The ductile-to-brittle transition diagram illustrates the relationship between a material's temperature and its propensity for ductile or brittle behaviours. At higher temperatures, materials tend to be ductile. They deform plastically before breaking, absorbing significant impact energy. On the other hand, at lower temperatures, materials become brittle. They fracture with minimal deformation, absorbing minimal energy. The impact test results align with the concept of the DBTT diagram. As the preheating temperature increases, the material experiences a shift towards the ductile region of its DBTT. This is reflected in the higher impact energy values observed at higher preheating temperatures.

At non-preheated condition, the low impact energy at the non-preheated state suggests the material is operating in a brittle regime, near its DBTT. On preheated conditions (150°C, 200°C, 250°C): As the preheating temperature rises, the impact energy increases, indicating an increase in ductility. The material is moving towards the ductile region of its DBTT. The highest impact energy observed at 300°C signifies that the material is well within its ductile region, having moved significantly away from its DBTT. This state corresponds to significantly higher toughness. The impact test results provide evidence that increasing preheating temperature enhances the toughness of the SS 304 and AISI 1037 steel joining. This is directly attributed to the material transitioning towards a more ductile state, as depicted by the DBTT diagram. By elevating the preheating temperature, the material gains greater resistance to impact forces, leading to increased impact strength and overall toughness.

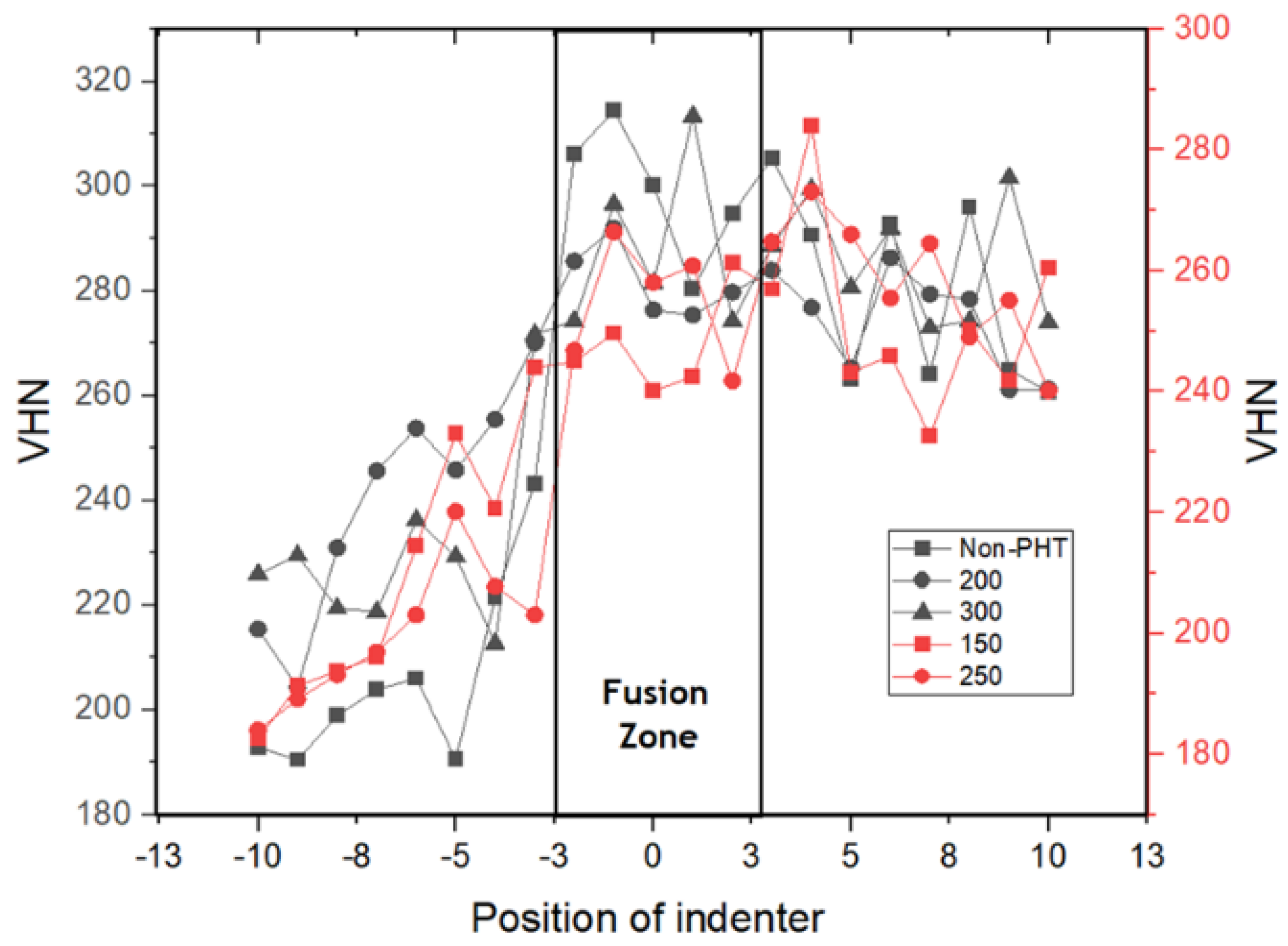

3.2. Hardness Measurements

Analysis of the distribution of hardness values at welded joints is carried out using the Vickers hardness method.

Figure 4 shows the Vickers hardness number (VHN) distribution across different zones of a weld sample. The weld samples were preheated to various temperatures: no preheat (Non-PHT), 150°C, 200°C, 250°C, and 300°C. The x-axis represents the position of the indenter relative to the weld centerline, with the fusion zone marked.

The fusion zone generally exhibits lower hardness compared to the heat-affected zones (HAZ). This is due to the melting and rapid solidification, resulting in coarse grains and a less dense microstructure, leading to reduced hardness. Variations within the fusion zone itself are likely due to cooling rate variations and solute segregation. The exact composition of the fusion zone will be a blend of the SS304 and AISI 1037, with potential formation of intermetallic phases depending on the welding process parameters. Heat-Affected Zones (HAZ) on

Figure 4 shows an increase in hardness relative to the respective base metals. The extent of this increase differs significantly depending on the base material.

In the side of SS304 HAZ, the increase in hardness might be less pronounced compared to the AISI 1037 HAZ. Austenitic stainless steels (like SS304) are less susceptible to significant hardness changes due to heat input because they don't undergo martensitic transformations. Any hardness increase would likely be due to strain hardening from the welding thermal cycle. In the AISI 1037 HAZ, the increase in hardness is more significant. Low-carbon steel (like AISI 1037) is more prone to microstructural changes upon heating and cooling during welding. The hardness increase is linked to the formation of martensite or bainite due to rapid cooling, both of which are significantly harder than the ferrite-pearlite microstructure of the base metal. Moreover, the increasing preheat temperature generally reduces the peak hardness in the HAZ for both base materials. This is because higher preheat temperatures lead to slower cooling rates, suppressing the formation of hard martensitic phases in AISI 1037 and reducing strain hardening in SS304.

3.3. Morphology Surface of Weld Joint

Figure 5 shows the morphology of welded joint surfaces on impact test specimens.

Figure 5(a) Without Preheating: The fracture surface exhibits a brittle fracture pattern, characterized by a rough, uneven surface with a lack of significant ductility. This indicates that the weld metal was unable to absorb the impact energy effectively.

Figure 5(b) 150°C, The fracture surface displays a transition from a brittle to ductile fracture. Some ductile tearing is evident, indicating that the weld metal has gained some toughness due to preheating.

Figure 5(c) 200°C, The fracture surface shows more pronounced ductile tearing, implying that the preheating at this temperature has further enhanced the weld metal's toughness. The fracture surfaces become progressively smoother and display evidence of ductile tearing, indicating that the weld metal is becoming more resilient to impact forces. This positive impact of preheating can be attributed to several metallurgical factors. Firstly, the reduced cooling rate due to preheating promotes the formation of a finer grain structure, which is inherently tougher. Secondly, preheating reduces internal stresses, allowing the material to deform more readily under impact.

Figure 5(d) 250°C shows the weld exhibits a substantial increase in ductility. The fracture surface is characterized by significant ductile tearing and a smoother appearance. On the

Figure 5(e) the weld displays the highest ductility, evidenced by a relatively smooth and even fracture surface with extensive ductile tearing. This indicates that the preheating at these temperatures has effectively mitigated the tendency for brittle fracture, making the welded joint much more resilient to impact loading. The preheating has significantly enhanced the weld metal's toughness, allowing it to absorb and dissipate impact energy more effectively.

The surface analysis highlights the crucial role of preheating in influencing the fracture behavior of welded joints. By controlling the cooling rate and reducing internal stresses, preheating promotes the formation of a finer, more ductile microstructure, leading to improved toughness. The visual evidence presented in these images underscores the importance of proper heat treatment practices in ensuring the safety and reliability of welded structures.

The surface analysis of the fractured welded joints provides valuable information for material scientists, engineers, and manufacturers. This data aids in optimizing preheating protocols for specific materials and applications, ensuring that welds possess the desired impact toughness for safe and reliable service. By understanding the impact of preheating on the fracture behavior of welded joints, we can create more durable and resilient structures that can withstand demanding environments and impact loads.

3.4. Microstructure Observation

Metallographic observations were conducted to investigate the evolution of microstructures that occurred in welded joints. This metallographic analysis uses the Keyence VH-Z450 microscope.

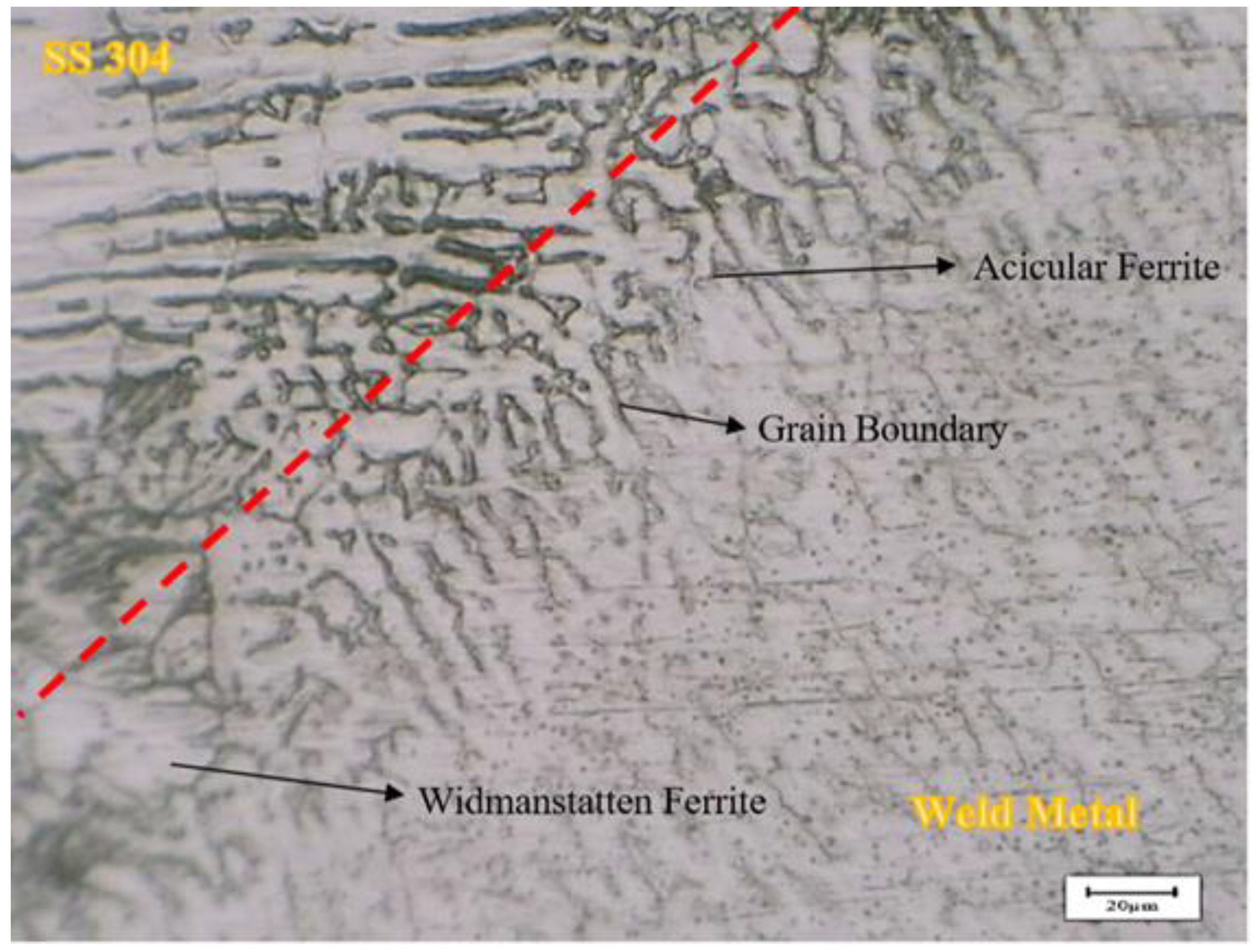

Figure 6 shows the evolution of microstructure experienced by welded joints AISI 1037 and SS AISI 304.

Figure 6(a) shows welded joints of fusion zones, heat-affected zones, and base zones of AISI 1037 and SS AISI 304.

Figure 6(b) shows the typical microstructure of austenitic stainless steel, while

Figure 6(d) shows carbon steel microstructure comprising pearlite and ferrite phases.

Figure 6(e) and 6(f) illustrate the fusion lines that mark the boundaries between the fusion zone and the base metal zone, highlighting the epitaxial growth of weld metal near the fusion line. The existing base metal grains at the fusion line serve as substrates for the nucleation process. The molten metal in the weld pool is in close contact with these substrate grains, fully wetting them. As a result, the molten metal nucleates easily on the grains of the substrate. Epitaxial growth in materials with a face-centred-cubic or body-centred-cubic crystal structure forms columnar dendrites oriented in the <100> direction [

14]. Columnar dendrites and fusion line of SS 304 and weld metal at a preheating temperature of 250 ºC can be seen in

Figure 7.

The Schaeffler diagram is often used to predict phase formation in the fusion zone after the welding process. This is closely related to phase formation in the fusion zone. [

19,

20,

21]. With carbon concentrations as low as 0.12%, the Schaeffler diagram is a suitable method for determining the weld composition of austenitic Cr-Ni steels. The percentage of the total weight is used to denote each composition concentration.

Figure 7 demonstrates the phases that will occur based on the interaction of the alloy composition, as determined by Ni

eq and Cr

eq calculations.

Figure 8 shows the phase prediction optimal parameter for a 304 austenitic stainless steel and AISI 4340 steel weld connection using E309. The welding condition dilution ratio in this operation is around 15%. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the Schaeffler diagram demonstrates that using E309 electrodes to weld AISI 1037 and AISI 304 exhibits austenite microstructure. In this state, hot cracking is frequently a problem in the fusion zone with austenite microstructure. Welds made of stainless steel experience hot cracking due to low-melting eutectics like S and P and alloy elements like Ti and Nb [

22]. In addition, a number of additional conditions, such as residual stress mixed with stress concentrations such as weld defects, can result in brittle failure.

Figure 9. shows a partially melted zone (PMZ) [

23] in the form of grain boundary thickening contained in thickening along the fusion line. The area between the 100% melting in the fusion zone and the 100% solid zone at base metal is the PMZ, a subset of the heat-affected zone (HAZ).

The microstructural analysis of the SS 304 weld zone, preheated to 250°C, revealed distinct features that highlight the impact of preheating and welding on the weld microstructure. The base metal exhibits a typical austenitic microstructure with a fine-grained, random arrangement of austenite grains. The fusion line, marking the interface between the base metal and weld metal, is clearly visible. At the fusion line, a remarkable feature is the presence of dendrites extending from each grain point in a single direction, varying from grain to grain. This is indicative of directional solidification as the weld pool cools, with the dendrites growing preferentially in the direction of heat dissipation.

Additionally, epitaxial growth is observed near the fusion line. This phenomenon, where crystals grow with a specific orientation relative to an existing crystal, is evident in both austenite and ferrite phases across the fusion line. This indicates that the crystallographic orientation of the base metal can influence the growth of the weld metal, leading to a degree of continuity in the microstructure across the interface.

The presence of both acicular and Widmanstatten ferrite phases in the weld metal is a direct consequence of the 250°C preheat temperature and the heat input during welding. The preheat influences the cooling rate of the weld, promoting the formation of Widmanstatten ferrite alongside acicular ferrite. However, the heat input further shapes the microstructure.

The heat input during welding significantly influenced the grain size and phase formation in the fusion zone and the heat-affected zone (HAZ). The HAZ, where the base metal experiences elevated temperatures but does not melt, can be further subdivided into the normalized zone and the overheated zone. The normalized zone, heated to just above A3 (austenite transformation temperature), experiences grain refinement, while the overheated zone, heated significantly above A3, undergoes grain coarsening and can exhibit partially oriented Widmanstätten ferrite patterns.

The presence of these distinct ferrite phases and the observed epitaxial growth have significant implications for the weld's mechanical properties and corrosion resistance. Acicular ferrite contributes to toughness and impact resistance, while Widmanstatten ferrite, depending on its morphology and distribution, can affect the weld's corrosion resistance. The epitaxial growth, while contributing to a degree of continuity in the microstructure, might also influence the stress distribution and crack propagation behavior.

The 250°C preheat temperature serves a crucial purpose in reducing thermal stresses and mitigating the risk of cracking in the weld. The preheat effectively manages the thermal gradients during welding, thereby minimizing the likelihood of hot cracking. This is particularly important for materials like SS 304, which are prone to cracking due to their high thermal conductivity.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties of a dissimilar weld joint between AISI 1037 carbon steel and AISI 304 stainless steel, employing the shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) method with preheating. The analysis focused on understanding the influence of preheat temperature and heat input on the weld microstructure and its potential implications for weld performance, specifically evaluating the impact strength of the joint through Charpy impact testing.

The Charpy impact testing results further emphasized the positive impact of preheating on the weld joint's toughness. The impact strength of the SS304 and AISI 1037 welded joints significantly increased with preheating temperatures up to 300°C, indicating a transition towards more ductile behavior. This improvement in impact strength is likely attributed to the influence of preheating on the weld microstructure, promoting the formation of more ductile phases and reducing the likelihood of brittle fracture.

The presence of epitaxial growth at the fusion line, where both austenite and ferrite phases exhibited a degree of crystallographic continuity across the interface, highlighted the influence of the base metal microstructure on the weld metal formation. This phenomenon could potentially affect the mechanical properties and stress distribution within the weld zone. The preheat temperature and heat input during welding significantly influenced the formation of acicular and Widmanstatten ferrite phases in the weld metal. While acicular ferrite contributes to toughness, Widmanstatten ferrite, depending on its morphology and distribution, can affect corrosion resistance. Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ) was found to be divided into a normalized zone, experiencing grain refinement, and an overheated zone, exhibiting significant grain coarsening and partially oriented Widmanstätten ferrite structures. The results of this study highlight the importance of preheating in dissimilar welding applications. The preheating temperature significantly influenced the microstructure and mechanical properties of the weld joint, leading to improved toughness and reduced susceptibility to brittle fracture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S. and A.A.; methodology, S, G,A.A; formal analysis, S, M.I.R., and G.; investigation, A.A, M.R.Y.A.A.W.; resources, S, G,, and A.A.; data curation, S, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.Y.Q.A.W, L.O.A.B., and A.A.X.; writing—review and editing, S., A.A., and L.O.A.B.; supervision, S, M.I.R., and G.; L.O.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to convey their great appreciation to Sriwijaya University and Halu Oleo University for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. Abdul Karim and Y.-D. Park, "A Review on Welding of Dissimilar Metals in Car Body Manufacturing," Journal of Welding and Joining, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 8-23, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Pratiwi, A. Arifin, Gunawan, A. Mardhi, and Afriansyah, "Investigation of Welding Parameters of Dissimilar Weld of SS316 and ASTM A36 Joint Using a Grey-Based Taguchi Optimization Approach," Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 39, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A. Arifin, A.B.Sulong, Z. Zulkarnain, B. Santoso, A. Mardhi, H.R. Vihardi, and S. Oktaviani, "Microstructures and mechanical analysis of friction welded carbon steel and stainless-steel using friction welding", AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 2689, No. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Raj and P. Biswas, "Effect of induction preheating on microstructure and mechanical properties of friction stir welded dissimilar material joints of Inconel 718 and SS316L," CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, vol. 41, pp. 160-179, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fang, X. Jiang, D. Mo, D. Zhu, and Z. Luo, "A review on dissimilar metals’ welding methods and mechanisms with interlayer," The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, vol. 102, no. 9-12, pp. 2845-2863, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Dak and C. Pandey, "A critical review on dissimilar welds joint between martensitic and austenitic steel for power plant application," Journal of Manufacturing Processes, vol. 58, no. May, pp. 377-406, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Khan and R. Chhibber, "Effect of filler metal on solidification, microstructure and mechanical properties of dissimilar super duplex/pipeline steel GTA weld," Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 803, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Ben Salem, E. Héripré, P. Bompard, S. Chapuliot, A. Blouin, and C. Jacquemoud, "Mechanical Behavior Characterization of a Stainless Steel Dissimilar Metal Weld Interface : In-situ Micro-Tensile Testing on Carburized Martensite and Austenite," Experimental Mechanics, vol. 60, no. 8, pp. 1037-1053, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chu et al., "Interfacial microstructure and mechanical properties of titanium/steel dissimilar joining," Materials Letters, vol. 307, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Dokme, M. Kulekci, and U. Esme, "Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Dissimilar Metal Welding of Inconel 625 and AISI 316L," Metals, vol. 8, no. 10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Gunawan and A. Arifin, "Intergranular Corrosion and Ductile-Brittle Transition Behaviour in Martensitic Stainless Steel," Indonesian Journal of Engineering and Science, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 031-041, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. D. Callister and D. G. Rethwisch, Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, 9th Edition: Ninth Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Incorporated, 2013.

- V. Dudko, J. Borisova, and R. Kaibyshev, "Ductile-Brittle Transition in Martensitic 12%Cr Steel," Acta Physica Polonica A, vol. 134, no. 3, pp. 649-652, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Kou, Welding Metallurgy. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2003. [CrossRef]

- B. K. Khamari, S. S. Dash, S. K. Karak, and B. B. Biswal, "Effect of welding parameters on mechanical and microstructural properties of GMAW and SMAW mild steel joints," Ironmaking & Steelmaking, vol. 47, no. 8, pp. 844-851, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Qazi, R. Akhtar, M. Abas, Q. S. Khalid, A. R. Babar, and C. I. Pruncu, "An Integrated Approach of GRA Coupled with Principal Component Analysis for Multi-Optimization of Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW) Process," Materials, vol. 13, no. 16, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Lippold, Welding Metallurgy and Weldability. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Anoop et al., "A Review on Steels for Cryogenic Applications," Materials Performance and Characterization, vol. 10, no. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Pouranvari and S. P. H. Marashi, "Dissimilar Spot Welds of AISI 304/AISI 1008: Metallurgical and Mechanical Characterization," steel research international, vol. 82, no. 12, pp. 1355-1361, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Brandi and C. G. Schön, "A Thermodynamic Study of a Constitutional Diagram for Duplex Stainless Steels," Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 268-275, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Guiraldenq and O. Hardouin Duparc, "The genesis of the Schaeffler diagram in the history of stainless steel," Metallurgical Research & Technology, vol. 114, no. 6, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Shankar, T. P. S. Gill, S. L. Mannan, and S. Sundaresan, "Solidification cracking in austenitic stainless steel welds," Sadhana, vol. 28, 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Rao, G. M. Reddy, and K. P. Rao, "Studies on partially melted zone in aluminium–copper alloy welds—effect of techniques and prior thermal temper," Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 403, no. 1-2, pp. 69-76, 2005. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).