Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Site

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Source of Experimental Materials

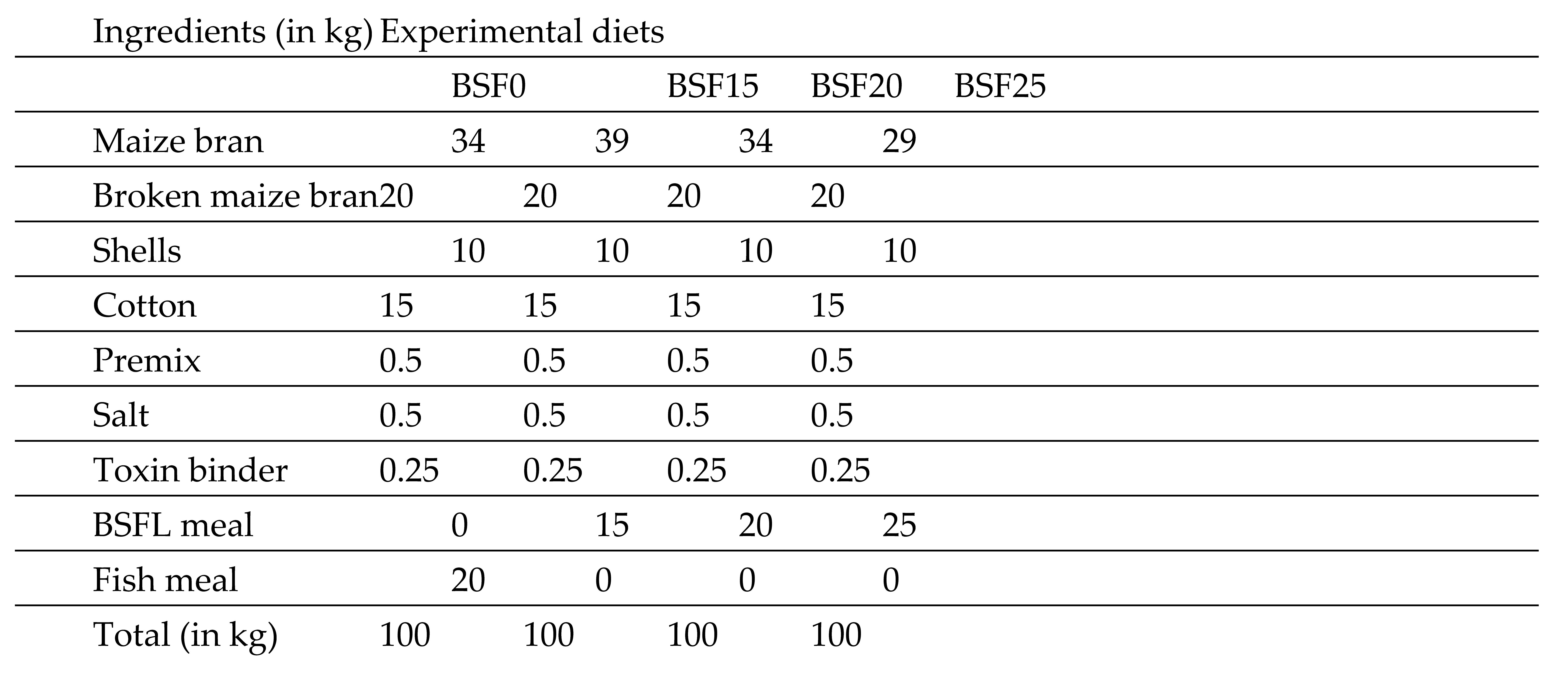

2.4. Experimental Treatments

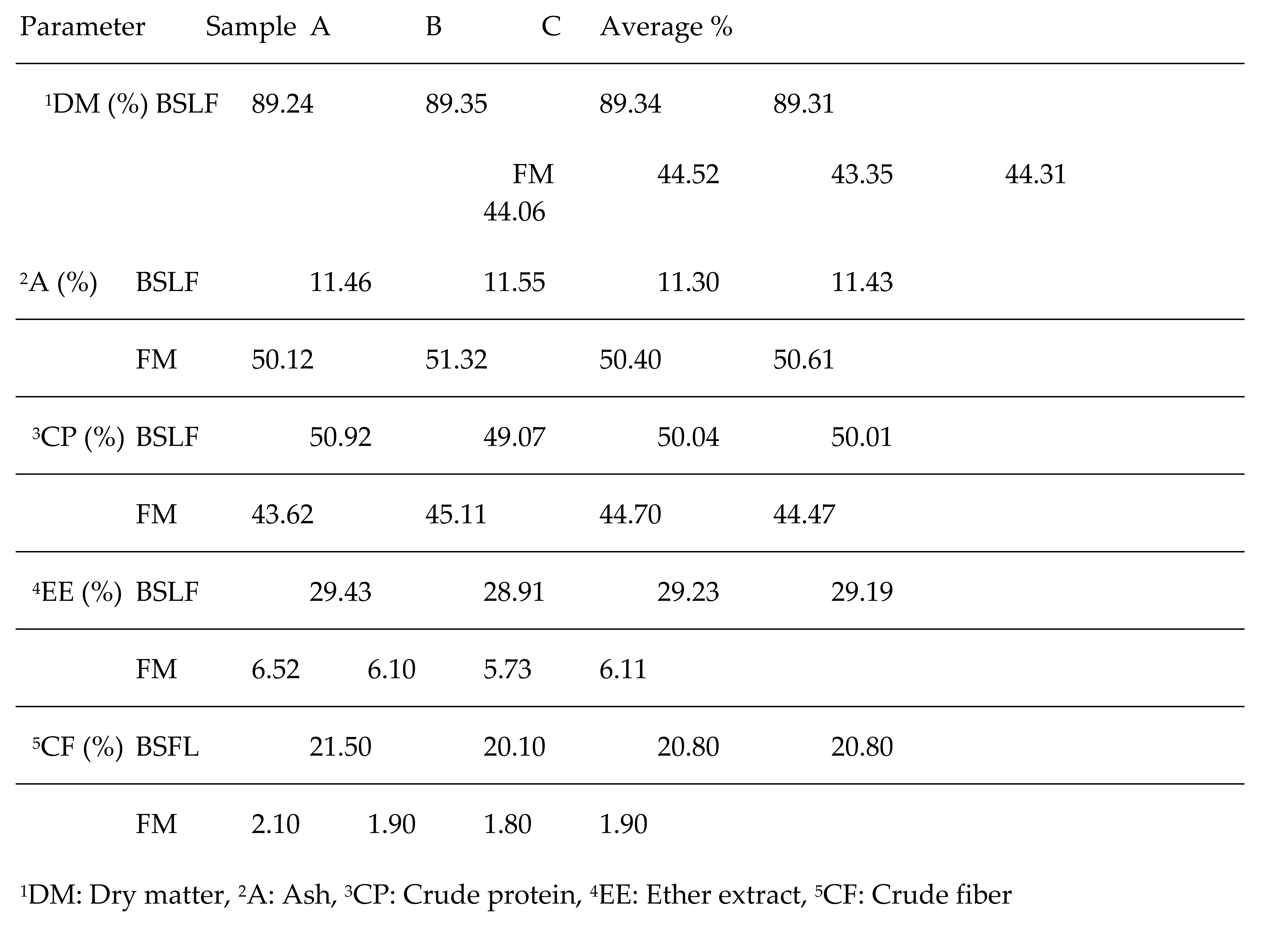

2.5. Nutrient Proximate Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Proximate Analysis of BSFL and FM

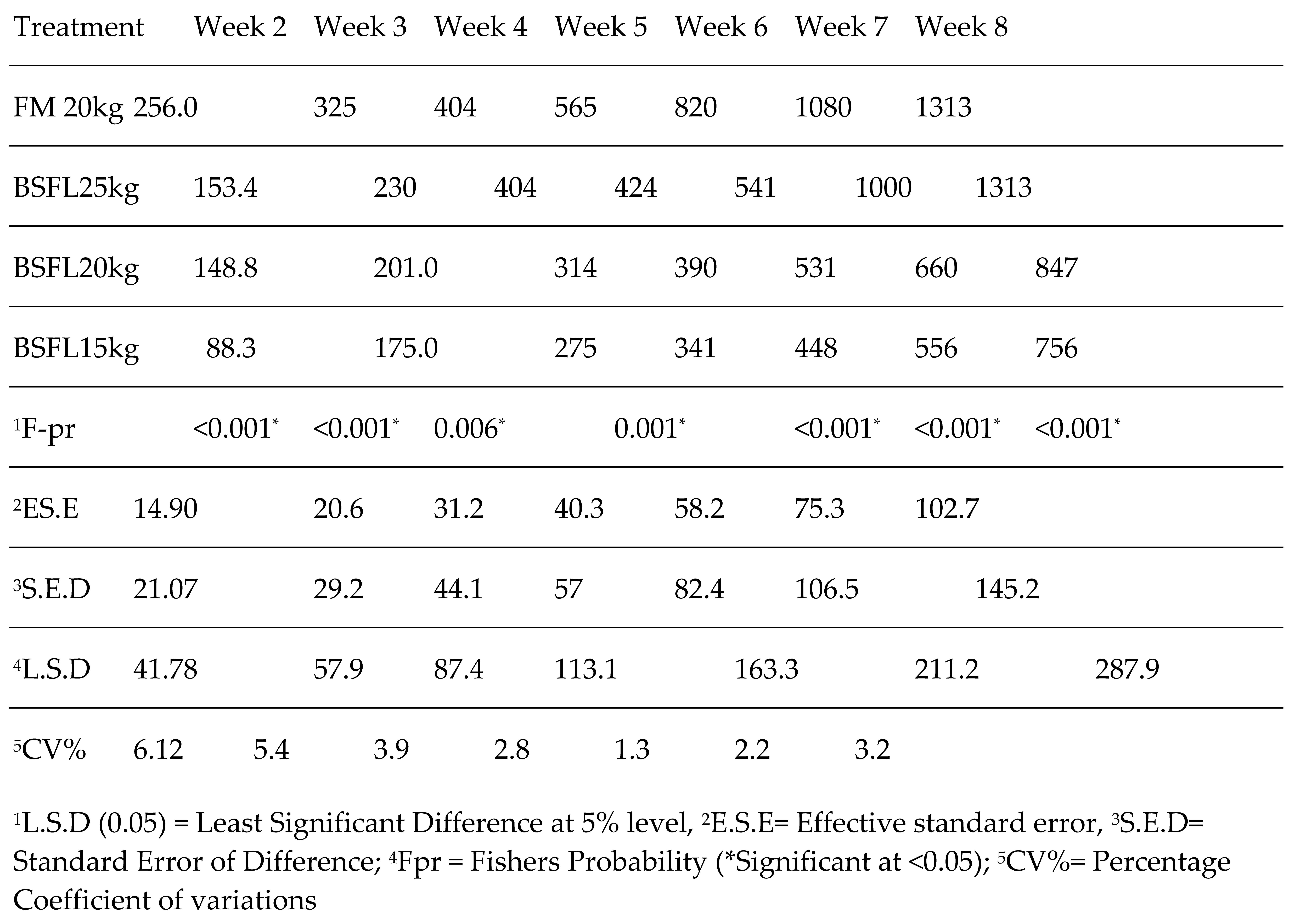

3.2. The effect of Substitution with BSFL Meal on Weight Gain

3.3. Effect of BSFL on Carcass Characteristics

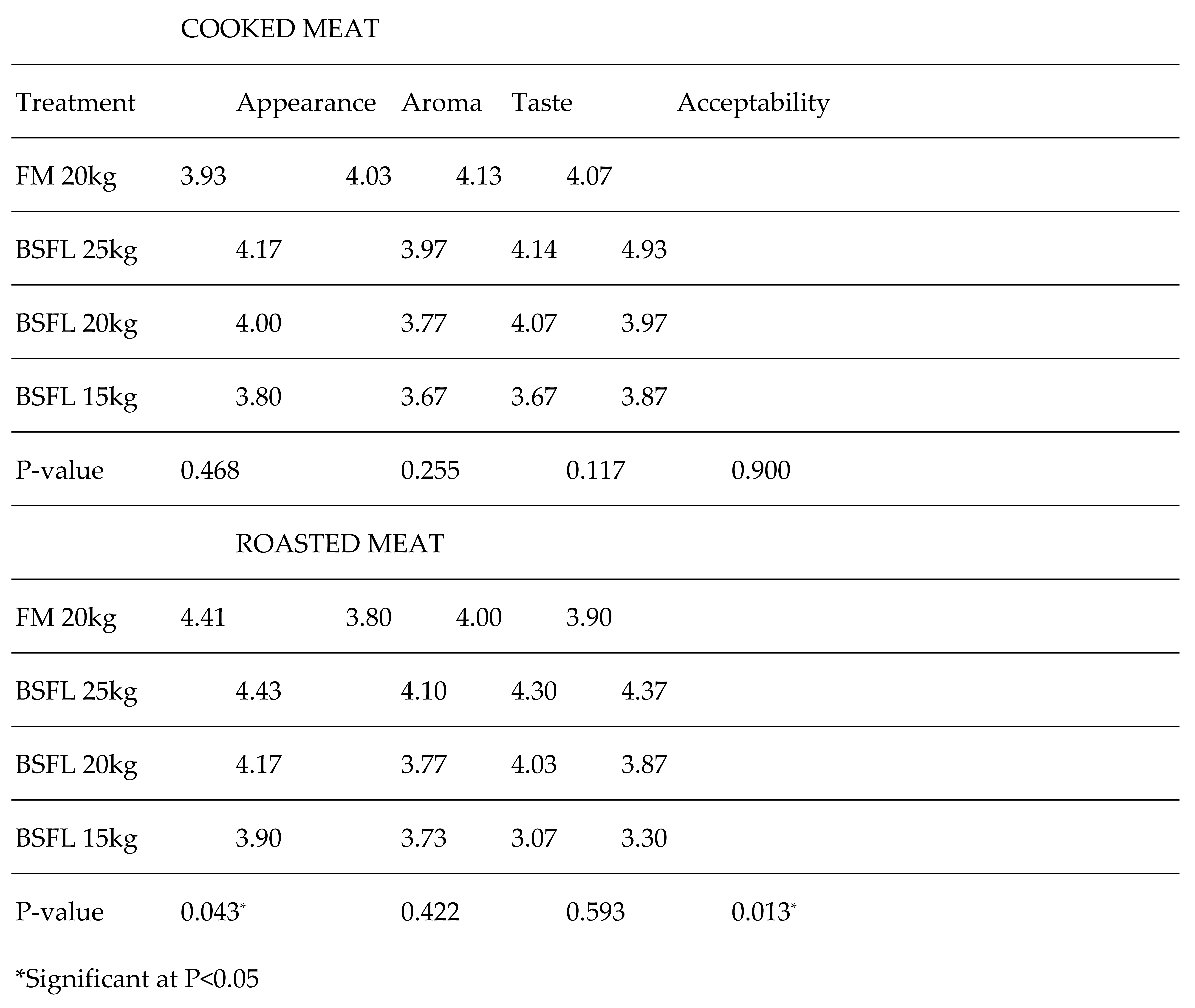

3.4. Organoleptic Taste Of Both Cooked and Roasted Meat of Broiler Birds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayohan S, Susanto I, Permata D et al. (2022) Effect of dietary inclusion of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) on broiler performance: A meta-analysis. E3S Web of Conferences 335: 00013. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M, Alagawany, M, FaragM, and Dhama K. 2015. Use of maize distiller’s dried grains with soluble (DDGS) in laying hen diets: Trends and advances. Asian J. Animal. Veterinary. Advance.10, 690-707 https://scialert.net/fulltext/?doi=ajava.2015.690.

- Thirumalaisamy G, Purushothaman MR, Kumar PV, Selvaraj P, Natarajan A, Senthilkumar S, Visha P, Kumar DR, Thulasiraman P (2016). Nutritive and feeding value of cottonseed meal in broilers – A review. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 4(8): 398-404. [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P., Muduli, K., Biswal, J. N., & Pumwa, J. (2020). Broiler Poultry Feed Cost Optimization Using Linear Programming Technique. Journal of Operations and Strategic Planning, 3(1), 31-57. [CrossRef]

- Verbeke W., Spranghers T., Patrick De Clercq P., De Smet S., Sas B., Eeckhout M., (2015) Insects in animal feed: Acceptance and its determinants among farmers, agriculture sector stakeholders and citizens, Animal Feed Science and Technology, 204, 72-87. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G., Bazer, F. W., Dai, Z., Li, D., Wang, J., & Wu, Z. (2014). Amino acid nutrition in animals: Protein synthesis and beyond. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 2, 387–417. [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Park, S.H.; Jung, H.J.; You, S.J.; Kim, B.G. Effects of Drying Methods and Blanching on Nutrient Utilization in Black Soldier Fly Larva Meals Based on In Vitro Assays for Pigs. Animals 2023, 13, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haasbroek, P.C. (2016). The use of Hermetia illucens and Chrysomya chloropyga larvae and pre-pupae meal in ruminant nutrition. Thesis (MSc), Stellenbosch University https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:87876144.

- Ravindran, V. (2017). Poultry feed availability and nutrition in developing countries. Poultry Development Review. FAO of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/4/al705e/al705e00.

- Mahmud, A T B A., Santi, Rahardja, DP., Bugiwati, RRSRA., Sari, DK. (2020). The nutritional value of black soldier flies (Hermetia illucen) as poultry feed. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 492/1 012129. [CrossRef]

- Belluco S, Losasso C, Maggioletti M, Alonzi CC, Paoletti MG, Ricci A (2013). Edible insects in a food safety and nutritional perspective: A critical review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety.12 (3): 296-313. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-S, Shelomi M. (2017). Review of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) as Animal Feed and Human Food. Foods. 6(10):91. [CrossRef]

- Smetana, S., Palanisamy, M., Mathys, A., (2016). Sustainability of insect use for feed and food: Life Cycle Assessment perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 137; 741-751. [CrossRef]

- Allegretti, G., Talamini, E., Schmidt, V., and. Bogorni, P. C. (2018). Insects as feed: an energy assessment of insect meal as a sustainable protein source for the Brazilian poultry industry. J. Clean Prod. 171:403– 412. [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G. Bellezza Oddon, S. Gasco, L. van Huis, A. Spranghers, T. Mancini, S. (2023). Review: Recent advances in insect-based feeds: from animal farming to the acceptance of consumers and stakeholders. J. Animal 17; 100904. [CrossRef]

- Dabbou, S., Gai, F., Biasato, I., Capucchio, M T., Biasibetti, E., Dezzutto, D., Meneguz, M., Plachà, I., Gasco, L., Schiavone, A., (2018). Black soldier fly defatted meal as a dietary protein source for broiler chickens: Effects on growth performance, blood traits, gut morphology and histological features. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 9, 49. [CrossRef]

- Bava, L.; Jucker, C.; Gislon, G.; Lupi, D.; Savoldelli, S.; Zucali, M.; Colombini, S. Rearing of Hermetia Illucens on Different Organic By-Products: Influence on Growth, Waste Reduction, and Environmental Impact. Animals 2019, 9, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, G.D.P., Hesselberg, T. A Review of the Use of Black Soldier Fly Larvae, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), to Compost Organic Waste in Tropical Regions. Neotrop Entomol 49, 151–162 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. C., Kelts, K., & Eric Odada. (2000). The Holocene History of Lake Victoria. Ambio, 29(1), 2–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4314987.

- AOAC. (2017). Standard Method Performance Requirements (SMPRs) for Identification and Quantitation of Free Alpha Amino Acids in Dietary Ingredients and Supplements. AOAC International. https://www.aoac.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SMPR202017_011.

- Jayasena D, Ahn D, Nam K, Jo C. Flavour Chemistry of Chicken Meat: A Review Anim Biosci 2013; 26(5):732-742. [CrossRef]

- Manurung R, Supriatna A and Esyanthi R R. Bioconversion of rice straw waste by black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens L.): Optimal feed rate for biomass production. J Entomol Zool Stud 2016; 4(4):1036-1041. https://www.entomoljournal.com/archives/2016/vol4issue4/PartK/4-3-163-796.

- Govorushko, S., Global status of insects as food and feed source: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019 91; 436-445. [CrossRef]

- Tschirner, M. and Simon, A. (2015) Influence of Different Growing Substrates and Processing on the Nutrient Composition of Black Soldier Fly Larvae Destined for Animal Feed. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 1, 249-259. [CrossRef]

- Barroso, F.G.; de Haro, C.; Sánchez-Muros, M.-J.; Venegas, E.; Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Pérez-Bañón, C. The potential of various insect species for use as food for fish. Aquaculture 2014, 422-423; 193–201. [CrossRef]

- Oonincx DGAB, van Broekhoven S, van Huis A, van Loon JJA (2019) Correction: Feed Conversion, Survival and Development, and Composition of Four Insect Species on Diets Composed of Food By-Products. PLOS ONE 14(10): e0222043. [CrossRef]

- Spranghers T, Ottoboni M, Klootwijk C, Ovyn A, Deboosere S, De Meulenaer B, Michiels J, Eeckhout M, De Clercq P, De Smet S. Nutritional composition of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) prepupae reared on different organic waste substrates. J Sci Food Agric. 2017. 97(8): 2594-2600. [CrossRef]

- Diener S, Zurbrügg C, Tockner K. Conversion of organic material by black soldier fly larvae: establishing optimal feeding rates. Waste Management & Research. 2009;27(6):603-610. [CrossRef]

- XiaoMing, C., XiaoMing, C., Feng Ying, Feng Ying, Zhang Hong, Zhang Hong, ZhiYong, C., ZhiYong, C., Durst, P. B., Johnson, D. V., Leslie, R. N., Shonoeditors, K., 20103207745, English, Book chapter Conference paper, Italy, 9789251064887, Rome, Forest insects as food: humans bite back. Proceedings of a workshop on Asia-Pacific resources and their potential for development, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 19-21 February, 2008, (85–92), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Review of the nutritive value of edible insects., (2010). https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20103207745.

- Bukkens, S. G. F. (1997). The nutritional value of edible insects. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 36(2–4), 287–319. [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Tran, G.; Heuzé, V.; Ankers, P. State-of-the-art on use of insects as animal feed. Anim. FeedSci. Technol. 2014, 197, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, M.,Martà nez, S.,Hernandez, F.,Madrid, J.,Gai, F., Rotolo, L., Belforti, M., Bergero, D., Katz, H., Dabbou, S., Kovitvadhi, A., Zoccarato, I., Gasco, L., Schiavone, A. Nutritional value of two insect larval meals (Tenebrio molitor and Hermetia illucens) for broiler chickens: Apparent nutrient digestibility, apparent ileal amino acid digestibility and apparent metabolizable energy. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2015, 209; 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, G., Ruiz, R., & Vélez, H. (2004). Compositional, Microbiological and Protein Digestibility Analysis of the Larva Meal of Hermetia illuscens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyiidae) at Angelópolis—Antioquia, Colombia. Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín, 57, 2491-2500. http://www.scielo.unal.edu.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0304-2847200400.

- Mulyono, M. Bioconversion of fermented tofu waste into high protein alternative feed using black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). Journal of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine. 2022:7(6): 185-188. [CrossRef]

- Miron, L.,Montevecchi, G., Bruggeman, G., Macavei, L I.,Maistrello, L.,Antonelli, A., Thomas, M. Functional properties and essential amino acid composition of proteins extracted from black soldier fly larvae reared on canteen leftovers. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2023. 87; 103407. [CrossRef]

- Müller A, Wolf D, Gutzeit HO. The black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens - a promising source for sustainable production of proteins, lipids and bioactive substances. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2017 ;72(9-10):351-363. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/znc-2017-0030/html.

- Pretorius, Q. (2011) The Evaluation of Larvae of Musca domestica (Common House Fly) as Protein Source for Broiler Production. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/6667.

- Okah, U.; Onwujiariri, E. B., 2012. Performance of finisher broiler chickens fed maggot meal as a replacement for fish meal. J. Agric. Technol., 8 (2): 471-477. http://www.ijat-aatsea.com/Past_v8_n2.

- Awoniyi T. A. M., V. A. Aletor and J. M. Aina, 2003. Performance of Broiler - Chickens Fed on Maggot Meal in Place of Fishmeal. International Journal of Poultry Science, 2: 271-274. https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=ijps.2003.271.274.

- Adeniji, A. A., 2007. Effect of Replacing Groundnut Cake with Maggot Meal in the Diet of Broilers. International Journal of Poultry Science, 6: 822-825. https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=ijps.2007.822.825.

- Téguia,A. and Mpoame,M. and Okourou Mba,J. A., 20033005775, English, Journal article, Belgium, 2295-8010 0771-3312, 20, (4), Brussels, Tropicultura, (187–192), AGRI-Overseas, The production performance of broiler birds as affected by the replacement of fish meal by maggot meal in the starter and finisher diets., (2002) https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:89537148.

- Sheppard D. C. Newton G. L. . 2000. Valuable by-products of a manure management system using the black soldier fly - a literature review with some current results. Proceedings, 8th International Symposium - Animal, Agricultural and Food Processing Wastes, 9–11 Octoer 2000. Des Moines, IA. American Society of Agricultural Engineering, St. Joseph, MI.

- Hwangbo, J. ; Hong, E. C. ; Jang, A. ; Kang, H. K. ; Oh, J. S. ; Kim, B. W. ; Park, B. S., 2009. Utilization of house fly-maggots, a feed supplement in the production of broiler chickens. J. Environ Biol., 30 (4): 609–614 http://www.jeb.co.in/index.php?page=issue_toc&issue=200907_jul09.

- Shi H, Ho CT. 1994. The flavour of poultry meat. Flavour of Meat and Meat Products. Shahidi F, editorBlackie Academic and Professional; Glasgow: p. 52–69.

- Sealey, W. M. ; Gaylord, T. G. ; Barrows, F. T. ; Tomberlin, J. K. ; McGuire, M. A. ; Ross, C. ; St-Hilaire, S., 2011. Sensory analysis of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, fed enriched black soldier fly prepupae, Hermetia illucens. J. World Aquacult. Soc., 42 (1): 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Atela J. A. , Ouma P. O., Tuitoek J., Onjoro P. A. and Nyangweso S. E. A comparative performance of indigenous chicken in Baringo and Kisumu Counties of Kenya for sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Pol. Res. 2016. 4(6) 97-104. [CrossRef]

- Mlaga, K.G., Agboka, K., Attivi, K., Tona, K., Osseyi, E. Assessment of the chemical characteristics and nutritional quality of meat from broiler chicken fed black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae meal. Heliyon (2022). [CrossRef]

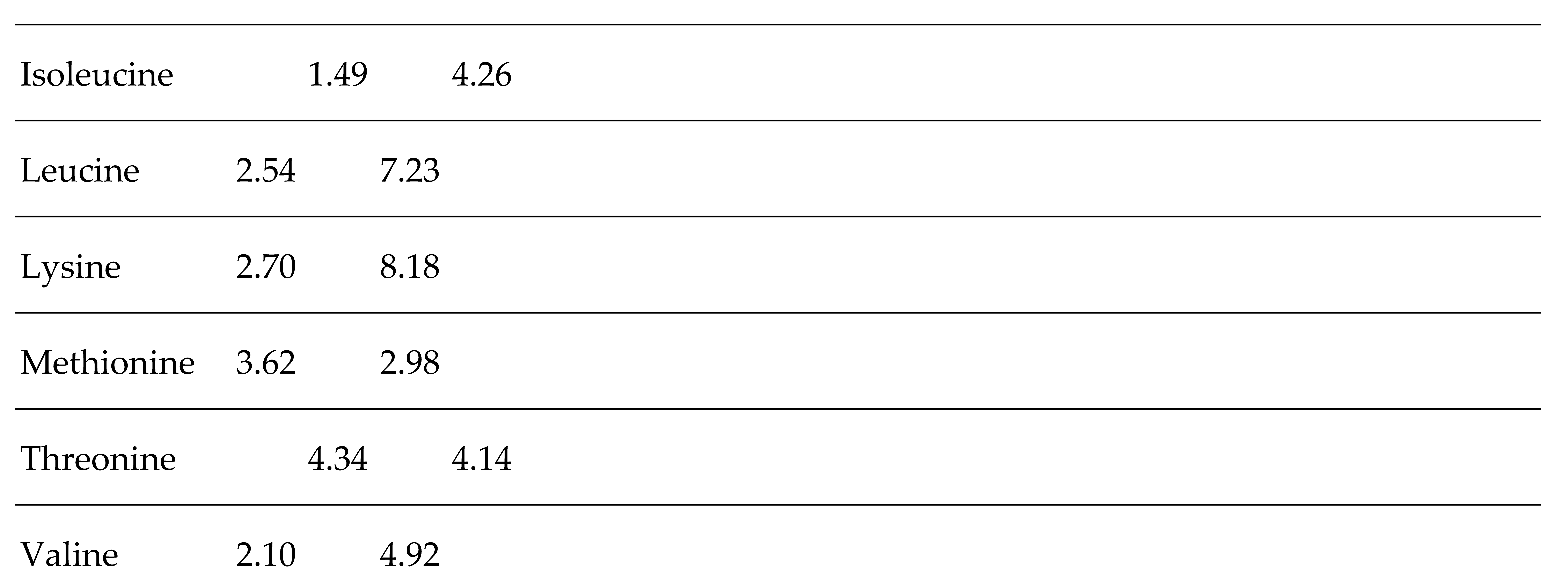

Tables

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).