1. Introduction

Affective polarization is a significant phenomenon in Western democracies. Iyengar et al. (2012), in their foundational study focusing on the USA, describe the growing division between supporters of the Democratic and Republican parties. This divide is marked by mutual distrust, discrimination, and acceptance of violence, with society split into in-groups and out-groups. Affective polarization undermines the willingness of citizens to engage with opposing views and accept democratic demands. Recent research shows this phenomenon also exists in other countries, often with stronger expressions than in the USA, and varies across regions (Allcott et al., 2020).

This study examines the role of radical right-wing populist parties in fostering affective polarization. These parties, particularly successful and controversial in recent decades, have reshaped how citizens perceive their political opponents, both among their supporters and detractors. Research links radical right-wing parties to exceptional levels of emotional polarization (Gidron et al., 2023). This study aims to explore how populism deepens hostile discourse, especially in the context of digital media, where such discourse thrives.

The study focuses on young Portuguese social media users, aged 18-21, who voted for the first time in the April 2024 national elections. Key questions include the relationship between populist sentiments and emotional polarization, the influence of radical right ideology, and the role of social networks in shaping polarization. The hypothesis suggests a significant connection between supporters of a radical right party and populist sentiments, with discourse emphasizing negativity and polarization. Based on a survey of 130 first-time voters, it assesses the association between radical right-wing arguments, populist sentiments, and emotional polarization, while exploring variations based on social network use.

2. Literature Review

Affective Polarization

Affective polarization can be considered as one of the dimensions of political polarization (Gidron et al., 2023). It works like this: instead of looking at the configuration of a given issue or the heterogeneity of online groups, affective polarization associates individuals' attitudes with a feeling of party belonging. Understood in this way, affective polarization occurs when individuals use negative signals to define those with whom they do not identify socially (tastes, preferences, sexuality, religion, race, among other topics are used in this judgment). An increasingly negative view of those who are outside of “my group” contributes, on the other hand, to characterizing in a more favorable way those with whom I identify and who are within “my group”. At more advanced levels of development, affective polarization assumes itself as the tendency that supporters of an idea or party must disapprove of, or even hate, supporters of different ideas (Gidron et al., 2023). It translates into animosity and social distancing between individuals (Iyengar et al., 2012), with consequences in terms of individuals' attitudes towards those designated as external members.

The consequences of this phenomenon have a significant impact, as they promote progressive social distancing. In terms of civic life, democratic discussion and the ability to reach compromises tend to be inhibited by placing supporters of one perspective in systematic opposition to supporters of another perspective – in a logic that equates a person’s partisanship with their personal identity. Understood in this way, and to the extent that partisanship is an important form of social identity, supporters of different perspectives tend to be averse to entering close interpersonal relationships with opponents (Iyengar et al., 2024). It is from this understanding that some authors consider the possibility of identifying the existence of affective polarization, and even of verifying different gradations, based on the existence of certain mechanisms of social distancing.

Social Networks and Populism

The connection between media, populism, and emotional polarization is well established. Initially, populists relied on mass media to communicate directly with the public, bypassing traditional political channels like speeches or parliamentary debate. However, they still had to adhere to journalistic standards and routines (Reese & Shoemaker, 2016). With the rise of the Internet, these barriers have diminished, enabling more direct communication. This new media landscape has fueled "anti-media populism" across the West (Fawzi & Krämer, 2021; Krämer, 2014), where populists promote distrust in professional media, portraying them as antagonists aligned with elites. Research combining selective exposure and media skepticism indicates that those with populist sentiments increasingly avoid mainstream media, accusing it of dishonesty and collusion with elites (Schulz et al., 2018; Stroud, 2008).

Social media has since become a dominant force in shaping political opinions, taking on roles previously held by traditional media, such as providing information and diverse perspectives on political issues. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter allow individuals and political actors, including populists, to express views freely without the constraints of journalistic ethics. This unrestricted communication often emphasizes a divide between the virtuous "ordinary" people and external "antagonists." Studies demonstrate the impact of populist messaging on public attitudes. For example, Hameleers & Schmuck (2017) found that populist rhetoric blaming political elites negatively influenced citizens' views of the political system, while Harteveld et al. (2022) showed that populist messages blaming immigrants and minorities fostered negative attitudes toward these groups.

Polarization in Social Networks

The analysis of affective polarization has gained significant attention in recent years, especially with the growing use of social media. Settle (2018) highlights how platforms like Facebook facilitate emotional polarization by enabling users to infer political identities from shared content, even if non-political. The process of segmenting individuals into groups based on social and political identities contributes to polarization. Research confirms that platforms like Facebook and YouTube, through algorithms and personalized content (Cho et al., 2020), promote emotional polarization by amplifying extreme views and engaging users with emotionally charged posts (Suhay et al., 2017; Allcott et al., 2020). In contrast, platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, which are visually focused, tend to foster less direct political content and thus lower levels of polarization (Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021; Colleen McClain et al., 2024).

The structure of each platform plays a critical role in how polarization develops. For instance, Facebook’s emphasis on personal connections creates information bubbles, while X (formerly Twitter) facilitates the rapid spread of polarizing opinions through short, emotionally charged messages. The anonymity on X further increases the potential for aggressive behavior, exacerbating polarization (Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021). Conversely, Instagram’s aesthetic focus and lighter content foster fewer polarizing discussions, although it can still reinforce social divisions based on lifestyle and identity.

Young adults, the focus of this study, increasingly use social media as their primary source of political information (Anderson et al., 2024). While these platforms can promote political engagement, they also expose young people to misinformation and emotional polarization, which can have broader consequences for their perception of political and social issues (Wu et al., 2019). Therefore, it is important to consider how these platforms shape not only political participation but also affective polarization among young users.

The Populist Radical Right

Radical right-wing political parties have gained significant relevance in contemporary politics, as their discourse is strongly associated with affective polarization. These parties, often referred to in academic literature as the "far right" or "populist right," generally adhere to democratic norms and operate within the rule of law, but they often challenge and exploit the fundamental values of democracy, potentially undermining its foundations. Despite ideological differences, right-wing populist movements across Europe and beyond share core beliefs, particularly the division between "the people" and "the elites”, where the former is portrayed as betrayed by the latter. Their political agenda typically emphasizes nativism and nationalism, using ethnic, religious, or linguistic minorities as scapegoats, while promoting an anti-intellectual and exclusionary narrative.

The increasing electoral success of these parties across Europe—from about 5% support two decades ago to over 15% today (Harteveld et al., 2022)—can be attributed to a specific "political style." This style is marked by a high level of emotionalization, with these parties appealing to the electorate's emotions while resisting rational debate and factual discourse (Davis et al., 2024; Engesser et al., 2017; Krämer, 2014; Mazzoleni, 2008). Emotional polarization is particularly heightened when these parties focus on cultural issues rather than economic ones, as cultural debates often align with deeply held moral convictions (Gidron et al., 2023; Johnston & Wronski, 2015). As a result, individuals tend to express more hostility towards those with differing views on immigration, national identity, or gender roles.

Radical right-wing populist parties capitalize on these cultural "wars," combining populist rhetoric with nativist ideals, positioning themselves as defenders of the "true people" against morally corrupt elites. This focus on cultural polarization explains the increasing prominence of these issues in contemporary political discourse, particularly as instigated by far-right movements.

In the Portuguese political context, several studies have positioned the Chega Party as an example of radical right-wing populism, showing how this party adopts an anti-elitist and nationalist narrative, typical of this political spectrum. Although Cas Mudde has not specifically studied the Chega Party, his theoretical framework has been used by several researchers (Marchi & Zúquete, 2024) to analyze this party, highlighting its similarities with other movements such as the Rassemblement National in France or Vox in Spain. This paper also adopts this characterization.

Gender Ideology as a Topic

As explained above, right-wing populist forces promote a sharp distinction between groups of “normal people” and the “corrupt elite”. The latter are often represented by enemies of “normal” people: feminists; LGBTQI people and rights activists; racial minorities, migrants; and, ultimately, those who are their main opponents – liberal and left-wing political groups (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2015). These enemy groups are the target of exclusionary political communication actions, which not only incite fear and the search for the enemy, but also call for a radical change in the social order, which involves reversing the equality rights and standards based on plurality that these enemy groups represent and defend.

In this context, there is now a rich and constantly growing body of scholarship on the links between the claims of radical right-wing ideologists and social debates on gender issues. These debates essentially address gender as a social versus biological construct, assess social practices shaped by gender roles and hierarchies, and contribute to or critique the formation of struggles for the idea of equality. Gender also serves as a metalanguage for negotiating different axes and practices of social and political power, for shaping struggles around cultural and moral hegemony, and for sustaining visions that make sense of supposed contemporary experiences of crisis (Dietze & Roth, 2020). Issues of gender equality have thus become a central theme for many populist radical right parties. These parties often adopt positions that are contrary to gender equality policies and feminist advances, and these issues are often framed in terms that appeal to social conservatism, traditionalism, and the defense of nativist values.

One of the key themes is opposition to the concept of “gender ideology”. Many of these parties use the term “gender ideology” to criticize and delegitimize policies and movements that promote gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights and sexual diversity. This term is often used to mobilize conservative voters, while accusing progressives of trying to impose an “agenda” that runs counter to traditional values. In terms of polarization dynamics, gender issues are used as symbols in the cultural battle between the radical right and the progressive left, as part of the right’s effort to draw a clear dividing line between “true patriots” or “ordinary people” and a liberal elite, perceived as out of touch and decadent. To this extent, the critique of “gender ideology” emerges as a defining characteristic of populist radical right parties (Dietze & Roth, 2020; Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2015), and as a tool to create a conservative political identity (Iyengar et al., 2012).

3. Hypotheses, Methods and Results

Hypotheses. The study tests three hypotheses: (1) youth with populist sentiments are more likely to exhibit higher levels of affective polarization, (2) those who endorse far-right causes have higher affective polarization, and (3) users of the X platform (formerly Twitter) have higher levels of polarization compared to Instagram users.

Methodology and findings. As an exploratory study, the sample was non-probabilistic and based on convenience, recruited through email lists and disseminated via personal contacts and communication networks, including social media and email. Two conditions were required for participation: respondents had to be users of at least one social network and eligible to vote for the first time in the 2024 Portuguese legislative elections, which took place on March 10, 2024, for the 16th Legislature of the Third Portuguese Republic. The online questionnaire was administered between February 26 and March 5, 2024, yielding 130 valid responses. The sample was expected to have distinctive characteristics, such as high media use, greater attention to civic and social issues, and gender balance. Data analysis utilized descriptive statistics, with simple and bivariate analysis of frequencies and qualitative variables through contingency tables.

Demographic control variables. Two demographic control variables were included, gender and age, which are also considered to be factors in the political participation process. In terms of age, all individuals were between 18 and 21 years old. It was found that 43.1% of respondents were male and 56.9% were female.

Political attitude. To assess populist sentiments, the questionnaire included instruments measuring key components of populism, based on widely used academic tools (Newman et al., 2019; Schulz et al., 2017). Two questions were posed: Q1, “I believe that most political leaders do not care about what people like me think,” and Q2, “I believe that ordinary people should be consulted whenever important decisions have to be made, particularly through popular referendums.” These questions aimed to capture core populist ideas, such as the antagonism between the people and elites, dissatisfaction with elite actions, and the value of popular sovereignty. Respondents answered on a 5-point scale, from “I completely disagree” to “I completely agree.” Following previous methodologies, the responses were combined into a single variable with two categories: individuals agreeing with both statements were classified as having populist attitudes, while all others were categorized as having mainstream attitudes. The results showed that 52 individuals (40%) expressed populist attitudes, while 72 (60%) held mainstream attitudes, with a balanced gender distribution (

Table 1).

Radical Right Populist Party. Based on the above characterization, in this study, we considered as the object of analysis one of the most prominent, divisive and polarizing electoral debate themes of the Chega party, which we adopted in this study as a representative of the Populist category: the argument that "

Gender ideology is killing schools and putting our children at risk. We must stop this! ", uttered by the party leader and expanded to a campaign theme and

slogan (

Figure 1). Respondents were asked to express their agreement with this statement, which was transcribed in full, and the responses were aggregated into two categories, of adherence or non-adherence to this perspective.

The data obtained show that 56.2% of respondents reject this argument, which was accepted by 43.8% of the individuals studied. If we cross-reference this data with the feelings associated with populism, mentioned above, we see that the respondents who reject the need to combat gender ideology have, for the most part, mainstream feelings (71.2% vs 28.8%); in turn, most young people who consider it necessary to combat gender ideology are classified as having populist feelings (54.4%) (see

Table 2).

In this study, affective polarization focuses on individuals' attitudes toward fellow citizens, rather than toward political elites, migrants, or other "outsiders." Unlike some research that uses sentiment thermometers to gauge feelings toward political parties or leaders (Iyengar et al., 2012), this study examines adolescents' social distancing attitudes. Affective polarization is known to hinder democratic dialogue and compromise by fostering antagonism between community members, especially when political affiliation becomes part of one's social identity (Iyengar et al., 2024; Turner-Zwinkels et al., 2023). This approach helps to identify whether hostile attitudes toward those with different ideological views are formed as early as adolescence. To measure affective polarization, participants were asked to rate their agreement with the statement: "I think it's okay to be friends with people who have different political beliefs" on a scale from 1 to 8 (Oden & Porter, 2023). Responses were grouped into two categories: scores of 1 to 4 were classified as "not polarized," while scores of 5 to 8 were considered "polarized." The results showed that 103 respondents (79.2%) were "not polarized," while 27 respondents (20.8%) were "polarized."

It was presented, as a hypothesis to be verified (H2), the fact that levels of affective polarization tend to be higher among young people who accept causes defended by the radical right-wing populist parties. In fact, the data obtained allow us to observe that those who adhere to the cause of the radical populist right are more polarized (24.6% versus 17.8% of those who do not adhere, which means a difference in magnitude of approximately 27.64%); to this extent, these data confirm Hypothesis 2.

Considering the data collected and Hypothesis 1, which suggests that levels of polarization tend to be higher among young people who have populist sentiments, a contingency table (

Table 4) was drawn up to compare the percentage of individuals classified as “polarized” in the “mainstream” and “populist” categories. While in the category of non-polarized individuals the percentage of populists is 37.9, in the polarized category it is 48.1, i.e. 10.2 percentage points higher, with a difference in magnitude of 26.91%. These data allow us to validate Hypothesis 1.

Social networks. The relevance of using social networks as a source of information as a factor with an impact on polarization dynamics was described above. However, as shown above, social networks are not homogeneous in terms of their impact on affective polarization. Several factors, related to the platforms themselves and the uses made of them, play a crucial role in how they affect affective polarization. We have seen, however, that networks that emphasize emotional involvement and content personalization tend to amplify these effects, and that network X tends to generate and amplify this polarization, while Instagram, by valuing the visual dimension and being composed of lighter content, generates a less polarizing environment. We therefore consider hypothesis (H3) that polarization levels tend to be higher among users of network X than among those of Instagram.

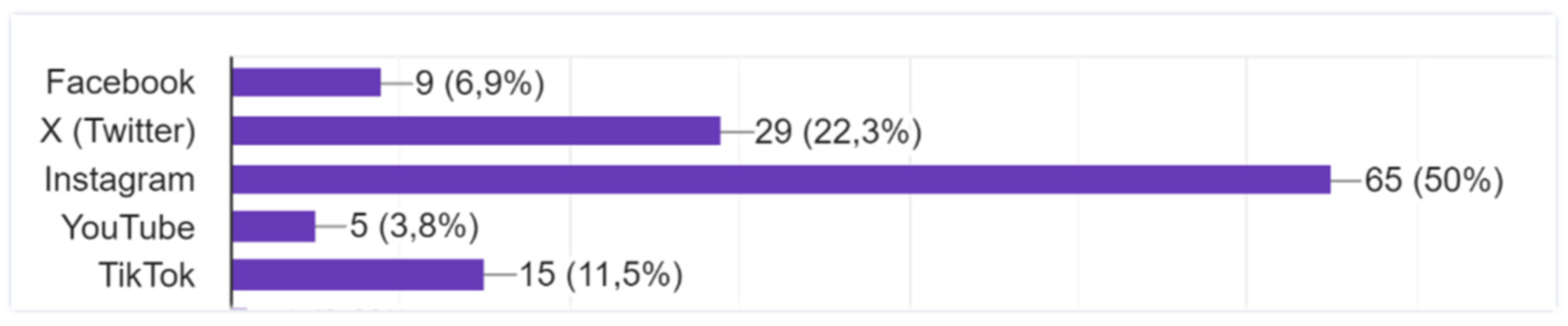

Respondents were asked which social network they used to obtain information on election-related matters. The following results were obtained (

Figure 2):

The small number of users of some social networks, as a source of information, does not allow them to be considered in this study, so we will focus our analysis on the levels of polarization in the two networks with the most significant volume of responses, which are, simultaneously, the object of one of the hypotheses we formulated above, H3: we therefore consider Instagram and X, platforms chosen by 50% and 22.3% of respondents, respectively (

Table 5). Thus, we see that the individuals who reveal that they choose Instagram are in line with the overall values of “polarization” (80%-20%). However, when we check the value of “polarized” individuals in the case of preferred users of network X (72.4%-27.6%), we see that it is higher - with a relative difference of 38% compared to Instagram users. This data allows to validate H3, insofar as the levels of polarization of users of network X are higher than those who prefer Instagram.

4. Discussion and Key Findings

This study investigated the interplay between populism, radical right-wing discourse, and emotional polarization among young voters during the 2024 Portuguese legislative elections. By examining the behavior and attitudes of the sample, the research explored how populist sentiments and social media usage contribute to political polarization. The findings highlight the complex dynamics between populist ideologies, far-right rhetoric, and the role of different social media platforms in shaping political identities and emotional responses. Below are four key findings that elucidate the relationship between these variables and their broader implications for democratic engagement.

Association Between Populism and Emotional Polarization: The study identifies a significant correlation between the presence of populist sentiments and heightened levels of emotional polarization among young voters. Individuals who express populist views are more likely to display emotional hostility towards opposing political groups, reinforcing in-group and out-group distinctions, a phenomenon that has been extensively documented in previous research.

Impact of Social Media Platforms on Polarization: The analysis reveals that different social media platforms contribute variably to emotional polarization. Platforms such as X, characterized by rapid, emotionally charged content and short-form communication, tend to amplify polarizing effects. In contrast, Instagram, with its focus on visual content and lighter interactions, is associated with lower levels of emotional polarization among its users.

Radical Right Discourse and Gender Ideology: The study highlights the role of specific far-right discourses, particularly surrounding "gender ideology," as a polarizing factor. A notable portion of young respondents who align with populist views also support arguments related to the rejection of gender ideology, reflecting the alignment of far-right populist rhetoric with cultural issues that foster emotional polarization.

Implications for Democratic Engagement: The findings underscore the potential threat of emotional polarization to democratic processes. As emotional hostility intensifies, the capacity for civil discourse and compromise diminishes, particularly among younger voters who are frequent users of social media. This polarization, exacerbated by far-right populist discourse and the structure of social media platforms, may erode social cohesion and democratic norms, making political dialogue increasingly adversarial and less constructive.

Indicators of affective polarization among young European adults are part of a broader and more complex process involving increasing animosity and distrust between opposing political groups. They translate into strong feelings of aversion among those who support different parties and are particularly associated with discursive practices affecting radical right parties. Most research shows that affective polarization has been growing among young Europeans since 2006 and is linked to factors such as the crisis of confidence in democratic institutions. In party-political terms, this is reflected in increased support for parties at the extremes of the party spectrum.

Among the main determinants of this phenomenon, alongside dissatisfaction with the political system and the increase in social inequalities (topics that are very present in populist discourse), is the growing use of social networks as sources of information and debate – but among their various effects is the suspicion that they serve as an amplifier of polarized discourses. These factors have a direct impact on electoral behavior, by influencing voting for radical parties and, to that extent, contributing to a weakening of democratic principles. Studies also indicate that emotional polarization affects young people more intensely, especially regarding voting for extremist right-wing parties, compared to other age groups. Looking at the election that took place a few days after the data for this study was collected, we can see a large-scale rise on the part of the Chega Party, supported significantly by young voters - an exit poll indicates that the Chega Party came in second place, with 25%, in the 18 to 34 age group.

In summary, this study contributes to the growing body of research on political polarization, populism, and the influence of social media among young voters. The findings underscore the significant role that populist sentiments and radical right-wing discourse play in fostering emotional polarization, particularly through the amplification mechanisms of certain social media platforms. The differentiation between platforms like X and Instagram in terms of their impact on polarization further highlights the importance of platform architecture and content dissemination in shaping political attitudes.

It demonstrates that emotional polarization, fueled by populist rhetoric, not only divides young voters but also undermines the potential for constructive democratic engagement. As these polarized emotional responses intensify, they erode the possibility of dialogue and compromise, posing a risk to the democratic fabric. Given the increasing reliance of young people on social media as a primary source of political information, addressing the factors that contribute to emotional polarization is crucial for the health of democratic discourse and participation.

Future research should focus on expanding the sample size and exploring the long-term effects of this polarization on political behavior. Additionally, policy interventions aimed at fostering media literacy and promoting balanced political discourse on social media could be valuable in mitigating the divisive impact of populism and radical right-wing ideologies among younger generations. This vicious cycle creates an environment in which public debate becomes less about the exchange of ideas and more about emotional loyalty to a group or ideology, exacerbating social and political divisions. For young people, this scenario can generate superficial political engagement, based on strong emotions but often uninformed and without room for dialogue.

5. Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the impact of populism and emotional polarization among young people, several limitations warrant attention in future research: Sample Size and Representativeness: The sample of 130 individuals, limited to a specific age group (18-21 years), constrains the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should include larger, more diverse samples spanning different age ranges and geographic regions to provide a broader understanding of polarization dynamics across various contexts. Geographic Limitation: This study focuses exclusively on Portugal during a specific election, offering a detailed local analysis but limiting the ability to generalize the results to other countries or cultural contexts. Comparative studies across different nations or electoral systems could deepen the understanding of how populism, social media, and emotional polarization interact in different settings. Mediators Between Social Media and Polarization: Although the study highlights significant differences between platforms (e.g., X vs. Instagram), it does not explore the underlying mechanisms, such as algorithms, content-sharing patterns, or influencer profiles, that may drive or mitigate polarization. A deeper investigation into these platform-specific factors could clarify the elements that contribute to or alleviate emotional polarization. Socioeconomic Factors: The study does not account for the influence of socioeconomic factors, such as education or financial status, on the relationship between populism, emotional polarization, and social media use. These factors could significantly shape how young people engage with populist discourse and experience political polarization. Addressing these gaps in future research would provide a more robust, generalizable understanding of the phenomenon and help develop more effective strategies to combat emotional polarization in democratic societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.F; Methodology, G.B.F; Investigation, G.B.F.; Writing—original draft preparation, G.B.F.; Writing—review and editing, G.B.F. The author have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & Yang, D. (2020). Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104254. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M., Faverio, M., & Park, E. (2024). How Teens and Parents Approach Screen Time. Pew Research Center. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep58219.

- Bennett, W. L., & Manheim, J. B. (2006). The One-Step Flow of Communication. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 608 (1), 213–232. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J., Ahmed, S., Hilbert, M., Liu, B., & Luu, J. (2020). Do Search Algorithms Endanger Democracy? An Experimental Investigation of Algorithm Effects on Political Polarization. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64 (2), 150–172. [CrossRef]

- Colleen McClain, B., Anderson, M., Gelles-Watnick, R., McClain, C., Nolan, H., & Manager, C. (2024). How Americans Navigate Politics on TikTok, X, Facebook and Instagram FOR MEDIA OR OTHER INQUIRIES (Vol. 12). https://www.pewresearch.org/pew-knight/.

- Davis, B., Goodliffe, J., & Hawkins, K. (2024). The Two-Way Effects of Populism on Affective Polarization. Comparative Political Studies. [CrossRef]

- Dietze, G., & Roth, J. (2020). Right-Wing Populism and Gender: A Preliminary Cartography of an Emergent Field of Research. In G. Dietze & J. Roth (Eds.), Right-Wing Populism and Gender (1st ed., pp. 7–22). transcript Verlag. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv371cn93.3.

- Engesser, S., Fawzi, N., & Larsson, A.O. (2017). Populist online communication: introduction to the special issue. Information Communication and Society, 20 (9), 1279–1292. [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N., & Krämer, B. (2021). The Media as Part of a Detached Elite? Exploring Antimedia Populism Among Citizens and Its Relation to Political Populism. In International Journal of Communication (Vol. 15). http://ijoc.org.

- Fenoll, V., Gonçalves, I., & Bene, M. (2024). Divisive Issues, Polarization, and Users' Reactions on Facebook: Comparing Campaigning in Latin America. Politics and Governance, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gidron, N., Adams, J., & Horne, W. (2023). Who Dislikes Whom? Affective Polarization between Pairs of Parties in Western Democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 53 (3), 997–1015. [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, M., & Schmuck, D. (2017). It's us against them: a comparative experiment on the effects of populist messages communicated via social media. Information Communication and Society, 20 (9), 1425–1444. [CrossRef]

- Harteveld, E., Mendoza, P., & Rooduijn, M. (2022). Affective Polarization and the Populist Radical Right: Creating the Hating? Government and Opposition, 57 (4), 703–727. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2024). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76 (3), 405–431. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C. D., & Wronski, J. (2015). Personality Dispositions and Political Preferences Across Hard and Easy Issues. Political Psychology, 36 (1), 35–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43783833.

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N., Baden, C., & Yarchi, M. (2020). Interpretative Polarization across Platforms: How Political Disagreement Develops Over Time on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Social Media and Society, 6 (3). [CrossRef]

- Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: A conceptual clarification and some theories on its effects. Communication Theory, 24 (1), 42–60. [CrossRef]

- Kubin, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45 (3), 188–206. [CrossRef]

- Marchi, R., & Zúquete, J. P. (2024). Far-right populism in Portugal: the political culture of Chega members. Social Analysis, 59 (251), e22116. [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J. (2022). Social Media and the Political Engagement of Young Adults: Between Mobilization and Distraction. 1 (1), 6–22. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, G. (2008). Populism and the Media. In Twenty-First Century Populism (pp. 49–64). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C.R. (2015). Vox populi or vox masculini? Populism and gender in Northern Europe and South America. Patterns of Prejudice, 49 (1–2), 16–36. [CrossRef]

- Oden, A., & Porter, L. (2023). The Kids Are Online: Teen Social Media Use, Civic Engagement, and Affective Polarization. Social Media and Society, 9 (3). [CrossRef]

- Reese, S. D., & Shoemaker, P. J. (2016). A Media Sociology for the Networked Public Sphere: The Hierarchy of Influences Model. Mass Communication and Society, 19 (4), 389–410. [CrossRef]

- Riel, J., & Washington, B. A. (2012). THE DIGITALLY LITERATE CITIZEN: HOW DIGITAL LITERACY EMPOWERS MASS PARTICIPATION IN THE UNITED STATES.

- Schulz, A., Wirth, W., & Müller, P. (2018). We Are the People and You Are Fake News: A Social Identity Approach to Populist Citizens' False Consensus and Hostile Media Perceptions. Communication Research, 47 (2), 201–226. [CrossRef]

- Settle, J. E. (2018). Frenemies: How Social Media Polarizes America. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Stroud, N. J. (2008). Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior, 30 (3), 341–366. [CrossRef]

- Suhay, E., Bello-Pardo, E., & Maurer, B. (2017). The Polarizing Effects of Online Partisan Criticism: Evidence from Two Experiments. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23 (1), 95–115. [CrossRef]

- Turner-Zwinkels, F.M., van Noord, J., Kesberg, R., García-Sánchez, E., Brandt, M.J., Kuppens, T., Easterbrook, M.J., Smets, L., Gorska, P., Marchlewska, M.., & Turner-Zwinkels, T. (2023). Affective Polarization and Political Belief Systems: The Role of Political Identity and the Content and Structure of Political Beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Morstatter, F., Carley, K. M., & Liu, H. (2019). Misinformation in social media: Definition, manipulation, and detection. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter, 21 (2), 80–90.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).