1. Introduction: The Open Society and the New Digital Ecosystem

The open society, as conceptualized by Karl Popper, is based on transparency, critical thinking, and the plurality of ideas. It prioritizes freedom of expression and rational debate as fundamental pillars for societal progress, ensuring that decisions are informed by deliberation and the contestation of opposing viewpoints. According to Popper (1945), "the open society cannot flourish without freedom of thought and the possibility of freely discussing opposing ideas" (p. 165). The free circulation of knowledge, supported by strong and independent institutions, enables continuous adaptation and protects against authoritarianism and dogmatism. Popper warns that "the greatest enemy of the open society is not error, but the refusal to correct error" (1945, p. 217), emphasizing the importance of mechanisms that encourage scrutiny and critical review. Historically, the functioning of this model relied on a robust press and structured public debates, where traditional media acted as gatekeepers of information, ensuring a level of factuality and responsibility in public discourse (López, 2024).

Over time, transformations in the public sphere have posed increasing challenges to the open society. In the post-war period, the expansion of the free press reinforced rational deliberation and respect for democratic norms, as journalism played a central role in informing citizens and fostering a public sphere where diverse perspectives could be debated (Lebovic, 2019). The emergence of television and mass media in the latter half of the 20th century introduced new dynamics, facilitating broad dissemination of political discourse while also simplifying complex issues and shifting political communication toward entertainment-driven formats (Postman, 1985). Despite these changes, traditional media adhered to editorial and ethical standards that maintained a certain degree of regulation over information dissemination. However, in the digital era, the structure of public debate has fundamentally shifted, becoming increasingly decentralized, fragmented, and emotionally charged. Social media platforms have radically transformed the public sphere, enabling any individual or group to produce and distribute content, often without factual verification. The algorithmic design of these platforms amplifies sensationalist content, prioritizing engagement-driven interactions over rational analysis. This results in a fragmented public space where polarization is reinforced by media consumption patterns that validate preexisting beliefs rather than fostering debate and critical reflection (Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021).

The survival of the open society depends on its ability to confront the challenges posed by affective polarization and digital populism. In an environment where information circulates freely but lacks traditional verification filters, democratic institutions must adapt to the new dynamics of communication (Allcott et al., 2019). The increasing dominance of private platforms in shaping public discourse has undermined the role of traditional gatekeepers, allowing misinformation, propaganda, and radical narratives to spread without effective countermeasures. Unlike previous media structures, where information was evaluated based on veracity and relevance, contemporary digital platforms prioritize engagement, often at the expense of accuracy and diversity of perspectives. The logic of algorithmic content curation fosters emotional responses, reinforcing biases and intensifying polarization rather than promoting balanced discourse (Boulianne & Larsson, 2023).

As Levy (2021) argues, the rise of affective polarization and informational fragmentation in online spaces directly challenges the principles of the open society by reducing common spaces for debate and eroding trust in democratic institutions. In this context, it is crucial to examine how digital transformations are reshaping the public sphere, amplifying populist and polarizing dynamics, and redefining the very foundations of contemporary democracy. Affective polarization, a growing phenomenon across Western democracies, is particularly concerning. Iyengar et al. (2012) highlight the deepening divide in the United States, where partisans increasingly distrust and avoid interacting with those from opposing political groups. This dynamic manifests as an "us versus them" mentality, weakening democratic cohesion and fostering animosity between political factions. While the severity of this phenomenon varies across nations, studies indicate that affective polarization is increasing in multiple political contexts (Allcott et al., 2020).

This study examines the role of radical right populist parties (RDPs) in fostering affective polarization within the public sphere. RDPs have emerged as the most controversial and electorally successful party family in recent decades, fundamentally altering political narratives and perceptions. Their rise has intensified polarization not only among their supporters but also among their detractors. Some scholars argue that RDPs exhibit a unique form of polarization, marked by particularly high levels of antagonism (Gidron et al., 2023). This study seeks to contribute to the growing body of research investigating these mechanisms, both theoretically and empirically. It explores the extent to which populism deepens hostile political discourse and assesses the suitability of digital media platforms for amplifying these dynamics.

Given the increasing role of social networks in shaping public opinion, this study focuses on a highly relevant demographic—young Portuguese voters aged 18 to 21—who primarily consume political information through digital platforms rather than conventional media. These first-time voters participated in the April 2024 legislative elections, presenting an opportunity to analyze their engagement with political discourse and polarization. Key research questions include: Is populist sentiment associated with heightened affective polarization? Is there a correlation between populist attitudes, radical right ideology, and increased polarization? Do different social media platforms contribute to varying levels of polarization? To address these questions, the study hypothesizes that (i) supporters of RDPs are more likely to exhibit populist sentiments; (ii) their discourse is characterized by negativity and hostility toward external groups; and (iii) social media platforms, due to their internal logic and structural features, play a significant role in shaping these discursive patterns.

In the context of the Portuguese early parliamentary elections of April 2024, this study analyzes a sample of 130 first-time voters. Using data collected through an online questionnaire, it assesses the relationship between support for radical right arguments, populist attitudes, and affective polarization. Additionally, it explores variations in polarization levels among individuals based on their preferred social media platforms for political information.

This research is part of a broader reflection on the evolution of the open society in the digital age, aiming to understand how transformations in the public sphere influence the foundations of contemporary democracy. The increasing mediatization of political interactions and the centrality of social networks in shaping public opinion raise essential questions about the limits of rational deliberation and the resilience of democratic institutions in the face of digital populism. By examining the impact of new forms of political communication and algorithmic content curation on public discourse, this study contributes to the ongoing debate on how to preserve democratic values in an era of fragmented and rapidly evolving information ecosystems.

2. Literature Review

Affective Polarization and the Erosion of Democratic Debate

Affective polarization can be considered one of the dimensions of political polarization, manifested in the way individuals associate their party identity with an emotional feeling towards other groups (Gidron et al., 2023). In this context, it is not just about disagreement over specific political ideas, but about the creation of emotional barriers that reinforce a sense of belonging to one group and rejection of the other. The dynamics generated by this process result in the use of negative social signals to define those who are perceived as political opponents, which can include factors such as tastes, preferences, sexuality, religion and race. This negative view of "others" simultaneously helps to reinforce the positive valuation of the group to which they belong, creating a self-affirming effect (Gidron et al., 2023).

In advanced states, affective polarization manifests itself in active hostility between political groups, translating into animosity and social distancing (Iyengar et al., 2012). This phenomenon not only affects the willingness for democratic dialogue but also reduces society's ability to find political and social compromises. As Popper (1945) argues, an open society depends on critical scrutiny, a plurality of ideas and a willingness to accept divergent views. However, as partisanship merges with deeper social identities, the space for rational and constructive debate diminishes. Iyengar et al. (2024) emphasize that this phenomenon leads to a weakening of interpersonal relationships between individuals with different political perspectives, generating greater social fragmentation. The emergence of social media has amplified this dynamic, accelerating affective polarization and transforming the way individuals relate to politics (Cinelli et al., 2021). In particular, the algorithmic logic of digital platforms plays a decisive role in the formation of information bubbles and the segmentation of public discourse. Networks like Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) favor content that maximizes engagement, while YouTube and TikTok prioritize viewing time, which favors repeated exposure to homogenous narratives (Allcott et al., 2019). This process reinforces group identities and reduces the willingness to consider divergent perspectives, creating an environment conducive to populist rhetoric and the reinforcement of prejudices (Cinelli et al., 2021).

In the context of Open Society 2.0, digital transformation presents a fundamental paradox: while it democratizes access to information and public participation, it also creates new challenges for democratic deliberation. The fragmentation of the digital public space and the growing polarization of online interactions puts the very notion of the open society defended by Popper at risk. Recent studies indicate that affective polarization is not restricted to the political arena, but affects news consumption, trust in institutions and the perception of reality (Levy, 2021). Highly polarized individuals tend to reject sources of information associated with the opposing group, regardless of their factual accuracy, which reinforces cognitive biases and deepens institutional distrust. The growing segmentation of public discourse on social media challenges the fundamental principles of an open society by reducing common spaces for debate and making it difficult to build social consensus. As Popper argues, democracy requires an environment in which competing ideas can be tested and debated rationally. However, in the current digital ecosystem, the increase in affective polarization weakens this principle and undermines the resilience of democratic institutions. In this sense, understanding the impact of social networks on affective polarization is essential for rethinking strategies that preserve democratic values and ensure the continuity of an open society in the digital age.

Digital Populism and the Crisis of Truth

Reflecting on the concept of the open society in the age of social media becomes particularly pertinent when examining the growing role of digital populism and the crisis of truth. The concept of the open society, as outlined by Karl Popper, advocated a model of society in which ideas could be freely debated and contested, promoting an environment of rational criticism and evolution. However, in the context of social media, this ideal faces new challenges, especially in relation to the spread of disinformation and affective polarization, driven by the logic of algorithms that favor emotional and controversial content. The relationship between the media, populism and, consequently, affective polarization is not new. Historically, the mass media have provided populists with a more direct channel to the public, more effective than traditional methods of political communication, such as speeches and manifestos. However, even with greater access, populists were subject to journalistic filters, criteria and news production routines, which limited their messages (Reese & Shoemaker, 2016). With the advent of the Internet, these filters have been diluted, allowing for more direct communication, characteristic of the "one-step flow of communication" model described by Bennett & Manheim (2006).

This "free" social media environment has favored the rise of anti-media populism (Fawzi & Krämer, 2021; Krämer, 2014), reflecting a general feeling of distrust in traditional media. For populist citizens, healthy skepticism has evolved into a distorted view in which the media are seen as enemies of the people, aligned with political elites, something that has been strengthened by studies on selective exposure and media skepticism (Stroud, 2008). In this context, social networks take center stage, acting as a new forum for the formation of political opinions by providing a platform where individuals and politicians (populist or otherwise) can disseminate their ideas without the limits imposed by the professional media. As Allcott et al. (2019) state, social networks have become a breeding ground for populist and polarizing discourses, leveraged by algorithmic dynamics that prioritize emotional and polarizing content.

Social networks allow citizens and politicians to express themselves directly, often creating divisions between the "ordinary, virtuous individual" and the guilty "other", be they part of the elites or minority groups. The proliferation of such guilt-laden discourses has been described in various studies as having profound impacts on public opinion, with concrete effects on attitudes towards politics and social groups. Examples include the research by Hameleers & Schmuck (2017), which showed how populist messages blaming political elites negatively influenced citizens' perceptions of the political system, or the study by Harteveld et al. (2022), which revealed how populist discourses directed against immigrants and minorities contributed to strengthening hostile attitudes towards these groups.

Digital populism thrives in an environment where the authority of traditional media is constantly questioned and where disinformation spreads easily. The fragmentation of information and the algorithmic logic of social networks create parallel realities, in which objective truth is replaced by polarizing, often emotional and misleading narratives (Guess et al., 2019). Recent examples of the spread of conspiracy theories, such as allegations of rigged elections in the US and Brazil, show how social media can amplify such narratives, resulting in serious consequences such as the storming of the Capitol in 2021 and attacks on democratic institutions in Brasilia in 2023. These events demonstrate how populist leaders exploit the dynamics of social media to promote simplified messages that resonate with great force, exacerbating distrust in democratic institutions and contributing to the crisis of truth.

In short, digital populism represents a significant challenge to Popper's open society, since social networks, far from being a forum for rational and constructive debate, fuel divisions and the spread of disinformation, resulting in a crisis of truth that threatens the foundations of democracy.

The Paradox of Digital Participation

The phenomenon of affective polarization has received increasing attention, especially with the intensive use of social media. Settle (2018) emphasizes that platforms such as Facebook play a crucial role in the formation of political identities by allowing individuals to transmit signals about their preferences in a tangible way. Sharing content on social media, even without explicit political intent, serves as an indication of users' political orientations, which makes it easier to infer their political identities. This perception mechanism contributes to affective polarization, as it segments individuals into groups and reinforces their social and political identities.

Several studies corroborate the idea that social networks can foster affective polarization. Recommending videos on YouTube (Cho et al., 2020) and exposure to hostile comments on social media (Suhay et al., 2017) increase polarization. Conversely, deactivating Facebook accounts has been shown to reduce polarization (Allcott et al., 2020). The literature suggests that the structure of social media platforms, including their algorithms and interaction dynamics, influences affective polarization (Cho et al., 2020; Fenoll et al., 2024). Social networks such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have varying impacts, depending on factors such as platform design, algorithms and user profiles. Recommendation algorithms play a key role, promoting content that generates "engagement", often prioritizing emotional and controversial posts. These dynamics favor the formation of information bubbles, further segmenting individuals into ideological groups. Facebook, with its emphasis on personal relationships, tends to create an environment prone to polarization. Twitter (now X), on the other hand, with its format of short, public messages, facilitates the rapid dissemination of polarizing opinions. Short, intense interactions in this environment amplify conflicts, which contribute to affective polarization. Visual platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, which focus on images and videos, have different dynamics. Although they don't directly promote polarizing political content, they can still create bubbles of homogenous thinking and social exclusion. The visual nature of Instagram reduces exposure to intense discussions, which decreases affective polarization, but still contributes to divisions on topics related to lifestyle and identity.

It's clear that social networks don't have homogenous effects on affective polarization. Platform design, content personalization and interactions between users all play crucial roles. Social networks that emphasize emotional involvement and personalization tend to amplify polarization, while those with a greater diversity of interactions tend to have a smaller impact. The business model of social networks, centered on "engagement", favors emotional and divisive content, creating isolated digital communities. A study by the Pew Research Center (2022) indicates that 62% of 18–24-year-olds trust social networks more than traditional sources, which makes them more vulnerable to manipulation and polarizing narratives. In this context, analyzing the impact of social media on young adults is crucial. Social media has become one of the main sources of political information for this group, especially on visually orientated platforms such as Instagram and TikTok (Anderson et al., 2024). While they increase access to information and facilitate political mobilization, they also favor radicalization and cognitive manipulation of voters (Allcott et al., 2019). Concerns about the physical and mental well-being of young people, exacerbated by disinformation, call for critical reflection on the effects of social media on affective polarization, especially in political and social contexts.

The Populist Radical Right and the Enemies of the Open Society

Radical right-wing political parties have become increasingly important in today's political landscape, particularly because of their links to forms of discourse that promote affective polarization (Vanagt et al., 2024). Analyzing these movements, especially in the context of the open society and its enemies, allows us to understand how such forces not only question fundamental democratic principles, but also seek to destabilize the foundations of the democratic political space. In academic literature, these groups are often described as "far right", "populist right" or sometimes simply "far right". In general terms, these parties operate within the democratic framework, accepting electoral processes and the rule of law, but they often challenge and instrumentalize the values of democratic politics, which can compromise the very essence of liberal democracy (Moffitt, 2018). These movements share a vision of division between the "people" and the "elites", with the former portrayed as betrayed by the latter. By taking a nativist and nationalist stance, these parties, instead of promoting an open and pluralist society, defend a political agenda that calls for exclusion, using ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities as scapegoats. This rhetoric is echoed in by anti-intellectual criticism, which suggests a dissociation between the people and the academic or cultural elites, fueling a dangerous ideological divide (Pappas, 2019).

The rise of radical right populist parties in Europe (Harteveld et al., 2022) can be seen as a response to the crisis of the open society, as described by Karl Popper. These movements, instead of promoting inclusive dialogue, resort to "culture war" as a strategy to foment affective polarization. Polarization is not just a matter of political disagreement, but an existential struggle to define what constitutes the "true society", as opposed to a cosmopolitan and inclusive vision. As Gidron et al. (2023) state, when cultural issues are prioritized, they create deeper and more emotional divisions, reflecting a battlefield where the notion of an open society is constantly under attack. The defense of a closed national identity against a pluralist vision emerges as one of the main characteristics of radical right populist rhetoric. In relation to the emotional structure of these movements, the "political style" that exploits emotions stands out, fueling resentment against the elites and constructing an imaginary in which the virtue of the "true people" is constantly threatened by external forces. The use of affective polarization, as observed in several studies (Davis et al., 2024; Engesser et al., 2017), demonstrates how this style mobilizes the electorate based on feelings of distrust and fear towards those who are seen as enemies of national identity. The focus on cultural rather than economic issues intensify polarization, as these issues are deeply linked to individuals' moral and existential beliefs, making them particularly divisive (Johnston & Wronski, 2015).

Looking at the Portuguese political context, the Chega Party is a good example of the articulation between radical right-wing populism and the denial of an open society. The party adopts a rhetoric that, instead of integrating and promoting a plurality of opinions and cultures, excludes and marginalizes groups, based on an anti-elite and nationalist narrative. Although Cas Mudde did not analyze the Chega Party specifically, his theory on far-right movements has been used to understand the similarities with other populist movements, such as Rassemblement National in France and Vox in Spain (Marchi & Zúquete, 2024). This comparison reveals how such parties are aligned with the enemies of the open society, attacking plurality and the acceptance of differences, with the aim of consolidating an exclusive domain of a homogeneous "true people". This scenario, in which affective polarization is amplified by radical right-wing parties, reinforces the dynamics that challenge the idea of an open society. Hate speech, the marginalization of social groups and the promotion of a "pure national identity" not only divide society, but also weaken the foundations of the democratic space, contributing to a scenario where the enemies of the open society gain strength.

Gender Ideology as a Theme

As explained above, contemporary populist dynamics promote a sharp distinction between groups of "normal people" and the "corrupt elite". In the context of the open society, as outlined by Popper (1945), this dichotomy represents a fundamental challenge: the tension between pluralism and the forces that seek to restrict it. Through social media, these polarizing narratives have acquired a new breadth, facilitating the dissemination of exclusionary discourses and the segmentation of audiences based on ideological affinities. The targets of these dynamics often include groups that symbolize pluralistic and inclusive values, such as human rights activists, racial minorities, feminists and LGBTQI movements (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2015). They are presented as threats to a supposedly "natural" social order and are the target of communication strategies that foster fear and promote the perception of crisis.

In this context, the open society faces increased challenges due to the structure of social media, which facilitates both free debate and the spread of disinformation and polarizing discourses. The debate on gender issues illustrates this tension, as the definition of gender as a social versus biological construct has become one of the axes of confrontation between progressive and conservative views. Social media serves as a space of dispute where these interpretations are reinforced, being used both to promote equality and to consolidate traditional hierarchies (Dietze & Roth, 2020). As Popper warned, the survival of the open society depends on the ability to resist movements aimed at reversing advances in the recognition of plurality and individual rights.

One of the central themes of this dispute is the notion of "gender ideology". This expression has been used by conservative movements to criticize and delegitimize equality policies, LGBTQ+ rights and sexual diversity. On social media, this rhetoric finds fertile ground for amplification, using strategies to misinform and mobilize conservative voters against a supposedly progressive "agenda". By framing the critique of "gender ideology" as a struggle between "true patriots" and liberal elites perceived as decadent, right-wing populist movements seek to undermine the pillars of an open and plural society (Dietze & Roth, 2020; Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2015). These dynamics reflect a fundamental challenge for the open society in the digital age: how to balance freedom of expression and public debate with the need to contain the spread of polarizing discourses that threaten the very essence of pluralism (Iyengar et al., 2012)

Comparison with Other Studies

Affective polarization and the impact of social networks on the formation of political opinions are not phenomena exclusive to Portugal. Several international studies have analyzed how these dynamics manifest themselves in different political and cultural contexts, allowing for a comparison that helps to situate the results obtained in this research. In the United States, research such as that by Iyengar et al. (2012) indicates that the affective polarization between Democrats and Republicans is not limited to ideological differences, but reflects an increase in interpersonal animosity. This phenomenon is amplified by partisan media such as Fox News and MSNBC, which reinforce ideological segregation by creating "echo chambers" (Stroud, 2008). In Portugal, although polarization is growing, the role of traditional media in ideological segmentation is less relevant, with social networks being the main vector of this division.

In Western Europe, the growth of the radical right has been accompanied by an increase in political polarization. Studies show that parties such as Rassemblement National in France, AfD in Germany and Vox in Spain use discursive strategies like those of Chega in Portugal, mobilizing popular discontent and promoting narratives of opposition between the "people" and the "elites" (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2015; Harteveld et al., 2022). However, while in countries like France this polarization has been consolidated for decades, in Portugal it is a more recent phenomenon, associated with the rise of the far right and the intensive use of social media to amplify populist discourses.

Brazil presents another interesting case, where the role of social media in political polarization has been particularly intense. Guess et al. (2019) show that disinformation spread via WhatsApp and YouTube played a crucial role in the 2018 and 2022 presidential elections, reinforcing ideological divisions and leading to episodes of political radicalization, such as the invasion of the Capitol in Brazil in 2023. Unlike Portugal, where networks such as X and Instagram are predominant in the consumption of political information among young people, in Brazil private messaging platforms have been central to the formation of information bubbles and polarizing discourses.

3. Hypotheses, Methods and Results

Hypotheses

Based on the literature review developed on the previous pages, the following hypotheses can be formulated:

Hypothesis 1: Young people with populist sentiments show higher levels of polarization in social media interactions. This hypothesis is in line with the open society framework because it reflects how populism can foster polarization and restrict rational debate, creating ideological bubbles that hinder pluralism.

Hypothesis 2: Young people who support causes defended by right-wing populist parties have higher levels of affective polarization. This hypothesis is related to the challenge of an open society to maintain a space for balanced debate, as affective polarization can lead to intolerance and the perception of political opponents as enemies, threatening the principle of pluralism.

Hypothesis 3: Users of the X network show higher levels of polarization compared to users who favor the Instagram network. This hypothesis highlights the role of digital platforms in shaping public opinion, suggesting that certain digital environments can amplify polarization. This reinforces the challenge for the open society, because if certain social media favor the fragmentation of discourse, they become obstacles to an informed and diverse debate.

Methodology and Data Collected

Given the exploratory nature of this study, the sample is non-probabilistic and was obtained through convenience sampling, using mailing lists and dissemination via personal contacts and digital communication networks, including email and social media. While this approach has limitations in terms of generalizability to the broader population of young voters, it was appropriate for conducting an initial survey shortly after the legislative elections. The timing of data collection allowed for the capture of impressions, attitudes, and patterns of affective polarization during a period of heightened political engagement, providing insights into the role of social networks and populist discourse in shaping youth political opinions. The data collected serve as a preliminary basis for examining how different social networks influence polarization levels, supporting future research that may adopt larger and more representative samples.

Two criteria were established for inclusion in the study: respondents had to be users of at least one social network and within the age range eligible to vote for the first time in national elections – in this case, the 2024 Portuguese legislative elections, held on March 10, 2024, to elect members of the Assembly of the Republic for the 16th Legislature of the Third Portuguese Republic. An online questionnaire was administered between February 26 and March 5, 2024, yielding 130 valid responses. This sample was deemed to exhibit key distinguishing characteristics, such as high media consumption, increased attention to civic and social issues, and a balanced gender representation. The data were analyzed and interpreted using descriptive statistics, with simple and bivariate frequency analysis of qualitative variables through contingency tables.

Demographic control variables. Two demographic control variables were included, gender and age, which are also considered to play a role in the political participation process. In terms of age, all the individuals were between 18 and 21 years old. It was found that 43.1 per cent of respondents were male and 56.9 per cent female.

Political attitudes. To assess the existence of populist sentiments, the questionnaire included some instruments to measure core components of populism. Taking as a reference instruments consistently used in academic studies on the same subject (Newman et al., 2019; Schulz et al., 2017), the following questions were formulated: Q1: "I think that most politicians don't care what people like me think" and Q2: "I think that ordinary people should be consulted whenever important decisions have to be made, namely through popular referendums." Both measures were intended to capture the central ideas associated with the populist ideology, namely those that reflect the antagonism between the people and the elites, the dissatisfaction with the actions of these same elites, and the importance attributed to the perspective of popular sovereignty. Each question had a 5-point response scale, the first two of which were contrary to statements Q1 and Q2 ("totally disagree" and "partially disagree"), a neutral center point ("neither agree nor disagree") and two points of agreement ("partially agree” and “totally agree" and "totally agree"). Following the methodology applied by previous studies, these two questions were combined into a single variable with two categories. Individuals who answered that they agreed that most politicians don't care what people think and that ordinary people should be consulted whenever important decisions must be made, namely through popular referendums, were categorized as having populist attitudes; all the rest were categorized as having mainstream attitudes.

The results show the following distribution: 52 individuals (40 per cent) with populist attitudes and 72 individuals (60 per cent) with mainstream attitudes, with a similar distribution in terms of gender (

Table 1).

Radical Right Populist Party. Based on the above characterization, in this paper we have considered as the object of analysis one of the most prominent, fractious and polarizing electoral debate themes of the Chega party, which we have adopted in this study as representative of the RDP category: the argument that "Gender ideology is killing schools and putting our children at risk. We must stop it!", uttered by the party leader and expanded into a campaign theme and slogan (

Figure 1). Respondents were asked to express their agreement with this statement, which was transcribed in full, and the answers were grouped into two categories, adherence or non-adherence to this perspective.

The data obtained shows that 56.2 per cent of respondents reject this argument, which was accepted by 43.8 per cent of the individuals studied. If we cross-reference this data with the feelings associated with populism, mentioned above, we see that the respondents who reject the need to combat gender ideology mostly have mainstream feelings (71.2% vs 28.8%); on the other hand, the majority of young people who consider it necessary to combat gender ideology are classified as having populist feelings (54.4%) (see

Table 2).

In this study, affective polarization focuses on individuals' attitudes toward fellow citizens, rather than toward political elites, migrants, or other "outsiders." Unlike some research that uses sentiment thermometers to gauge feelings toward political parties or leaders (Iyengar et al., 2012), this study examines adolescents' social distancing attitudes. Affective polarization is known to hinder democratic dialogue and compromise by fostering antagonism between community members, especially when political affiliation becomes part of one's social identity (Iyengar et al., 2024; Turner-Zwinkels et al., 2023). This approach helps to identify whether hostile attitudes toward those with different ideological views are formed as early as adolescence. To measure affective polarization, participants were asked to rate their agreement with the statement: "I think it's okay to be friends with people who have different political beliefs" on a scale from 1 to 8 (Oden & Porter, 2023). Responses were grouped into two categories: scores of 1 to 4 were classified as "not polarized," while scores of 5 to 8 were considered "polarized." The results showed that 103 respondents (79.2%) were "not polarized," while 27 respondents (20.8%) were "polarized."

It was presented, as a hypothesis to be verified (H2), the fact that levels of affective polarization tend to be higher among young people who accept causes defended by the radical right-wing populist parties. In fact, the data obtained allow us to observe that those who adhere to the cause of the radical populist right are more polarized (24.6% versus 17.8% of those who do not adhere, which means a difference in magnitude of approximately 27.64%); to this extent, these data confirm Hypothesis 2.

Considering the data collected and Hypothesis 1, which suggests that levels of polarization tend to be higher among young people who have populist sentiments, a contingency table (

Table 4) was drawn up to compare the percentage of individuals classified as “polarized” in the “mainstream” and “populist” categories. While in the category of non-polarized individuals the percentage of populists is 37.9, in the polarized category it is 48.1, i.e. 10.2 percentage points higher, with a difference in magnitude of 26.91%. These data allow us to validate Hypothesis 1.

The findings indicate that adolescents with populist inclinations exhibit greater affective polarization aligning with theoretical expectations but warrant a nuanced interpretation. While populist sentiments often amplify in-group and out-group dynamics, as suggested by Mudde (2004), it is equally important to consider the role of negative perceptions directed toward populist right parties themselves. Research, such as Harteveld et al. (2022), has demonstrated that these parties are often more intensely disliked than other political groups, evoking strong negative emotions across the political spectrum. This dual dynamic—where populist inclinations foster hostility toward opposing groups while simultaneously attracting animosity from the broader electorate—may intensify polarization among adolescents who align with these ideologies.

To contextualize the results, it is possible that the heightened polarization observed among adolescents with populist sentiments reflects a compounded effect: on one hand, the antagonistic rhetoric inherent to populism emphasizes divisions, and on the other, the social and political stigma associated with populist parties may reinforce feelings of hostility both within and outside these groups. This interplay suggests a bidirectional process, where the polarization attributed to populist inclinations is not only a product of ideological alignment but also of the societal reactions these alignments provoke. Future research could explore this complexity further, potentially disentangling the contributions of internal group dynamics and external perceptions in shaping affective polarization.

Social networks. The relevance of using social networks as a source of information as a factor with an impact on polarization dynamics was described above. However, as shown above, social networks are not homogeneous in terms of their impact on affective polarization. Several factors, related to the platforms themselves and the uses made of them, play a crucial role in how they affect affective polarization. We have seen, however, that networks that emphasize emotional involvement and content personalization tend to amplify these effects, and that network X tends to generate and amplify this polarization, while Instagram, by valuing the visual dimension and being composed of lighter content, generates a less polarizing environment. We therefore consider hypothesis (H3) that polarization levels tend to be higher among users of network X than among those of Instagram.

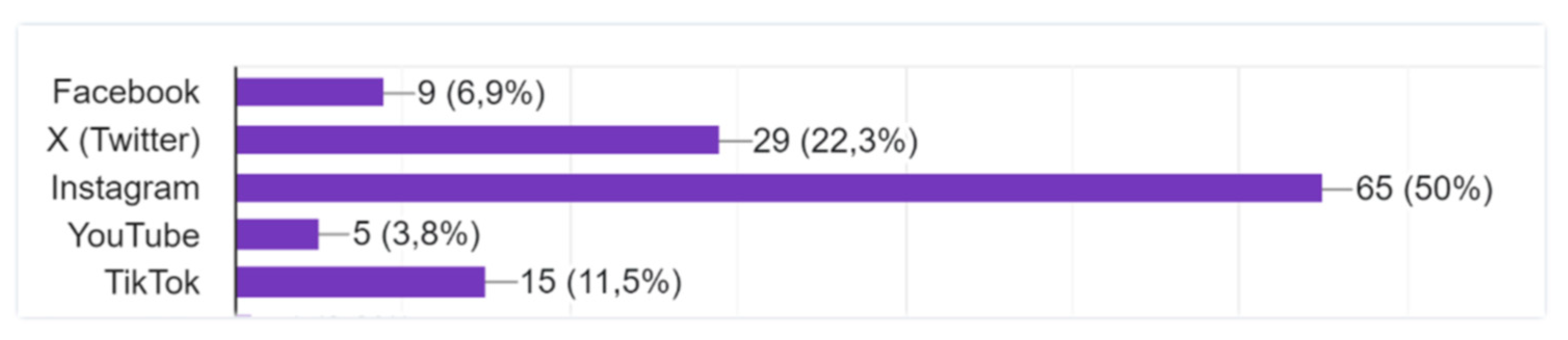

Respondents were asked which social network they used to obtain information on election-related matters. The following results were obtained (

Figure 2):

The small number of users of some social networks, as a source of information, does not allow them to be considered in this study. So, we will focus our analysis on the levels of polarization in the two networks with the most significant volume of responses, which are, simultaneously, the object of one of the hypotheses we formulated above, H3. We therefore consider Instagram and X, platforms chosen by 50% and 22.3% of respondents, respectively (

Table 5). Thus, we see that the individuals who reveal that they choose Instagram are in line with the overall values of “polarization” (80%-20%). However, when we check the value of “polarized” individuals in the case of preferred users of network X (72.4%-27.6%), we see that it is higher - with a relative difference of 38% compared to Instagram users. provides a more comprehensive analysis, the results were expanded to include statistical metrics. The correlation between social media use and affective polarization was calculated (

r=0.45,

p<0.01 r=0.45,p<0.01), indicating a moderate relationship. Effect size (Cohen’s

d) was calculated for the comparison between X and Instagram users, yielding a value of 0.62, suggesting a moderate effect. Furthermore, the confidence intervals for the mean difference in polarization between these platforms ranged from 0.32 to 0.92, underscoring the robustness of the findings. This data allows to validate H3, insofar as the levels of polarization of users of network X are higher than those who prefer Instagram.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that affective polarization among young voters is influenced by both their populist sentiments and their preferred social media platforms. While the convenience-based sample limits broad generalizations, the data reveal consistent patterns that align with previous research on digital polarization. Notably, respondents who expressed populist sentiments exhibited higher levels of affective polarization, reinforcing the notion that populist narratives contribute to the segmentation of political discourse. Additionally, the choice of social media platform played a significant role, with users of X (formerly Twitter) showing greater polarization compared to those who relied on Instagram for political information. These results suggest that digital environments, shaped by algorithmic curation and user interaction dynamics, may reinforce ideological divisions and contribute to the fragmentation of public debate.

Although these findings provide valuable insights into the relationship between digital participation and political polarization, they should be interpreted with caution. Given the non-representative nature of the sample, future research with larger and more diverse datasets is necessary to confirm and expand upon these observations. Nevertheless, this study contributes to the ongoing discussion on how social media platforms influence democratic engagement, underscoring the need for further exploration into the mechanisms that drive affective polarization in the digital age.

The comparison with various international contexts reveals that, although affective polarization is a phenomenon present in Western democracies, its expression and intensity vary according to political and media contexts. Portugal follows trends observed in the US and Europe, particularly regarding the impact of social networks on the fragmentation of public debate, but also exhibits distinct characteristics, such as the recent rise of the radical right and the lesser influence of traditional media on ideological division. These differences underscore the importance of research to assess whether polarization in Portugal will continue to escalate or if it can be mitigated through media education and digital regulation strategies. The defense of an open society, as proposed by Karl Popper, requires a continuous commitment to critical scrutiny and the revision of democratic structures, ensuring that informational pluralism is reinforced, not undermined, by the digital environment.

This study goes beyond merely describing patterns of media behavior and affective polarization among young voters; it contributes to the broader debate on the contemporary challenges facing the open society. The empirical findings engage directly with recent studies on the impact of algorithmic architecture on political opinion formation (Cinelli et al., 2021) and the relationship between digital populism and institutional delegitimization (Engesser et al., 2017). By examining how young voters interact with different digital platforms and how these interactions influence their political perceptions and affective polarization, this study enhances the conversation on the impact of social media on democracy and the erosion of open society principles. Consistent with Popper's theory (1945), it demonstrates how the contemporary information landscape constrains the capacity for critical correction, exacerbating mistrust and antagonism between political groups. Thus, this research not only broadens our understanding of the effects of algorithmic mediation and digital populism but also suggests potential directions for future studies and strategies to mitigate these phenomena.

Indicators of affective polarization in young European adults are part of a broader process of increasing animosity and distrust between opposing political groups. Polarization manifests itself in aversion between supporters of different parties, being particularly associated with the discursive practices of the radical right. Since 2006, this phenomenon has been on the rise, linked to the crisis of confidence in democratic institutions and the rise of parties at the extremes of the political spectrum. Dissatisfaction with the political system and the increase in social inequalities are identified as determining factors in this dynamic, while the role of social networks as amplifiers of polarized discourse is also highlighted. The direct impact on electoral behavior is evident, especially among young people, who are more likely to vote for right-wing extremist parties (Times, 2024; Hickman, 2025). The analysis of the electoral act following the data collection in this study reveals a significant increase in support for the Chega Party among young people, reflecting this trend. The results confirm that the existence of populist sentiments tends to be associated with the acceptance of radical right-wing discourses and higher levels of affective polarization. The study also reveals significant differences between individuals who prioritize different social media platforms: some encourage a more balanced debate, while others, due to their architecture and algorithmic dynamics, reinforce antagonism and emotional polarization.

From the perspective of an open society, these results represent a central challenge. Democracy depends on the possibility of critical review, continuous scrutiny of institutions, and the acceptance of contradiction as an essential part of the political construction process. However, the contemporary digital environment has encouraged the fragmentation of the public sphere, where algorithmic logic prioritizes emotional and polarizing content over informational diversity. When rational debate gives way to the reaffirmation of pre-existing beliefs and hostility towards divergent perspectives, the democratic structure itself can be weakened. As emphasized in the Popperian conception, the survival of an open society requires that institutions and citizens cultivate criticism, promote reflective thinking, and prevent freedom of expression from becoming a vehicle for the erosion of democratic pluralism. In this scenario, it is essential to reflect on strategies that strengthen democratic resilience, ensuring that information circulates in a pluralistic manner and that citizens develop media literacy that enables them to discern between reasoned argument and emotional manipulation.

In short, affective polarization and digital populism represent concrete challenges for maintaining an open society, requiring solutions that promote a more balanced information space consistent with democratic values. The vitality of democracy cannot be taken for granted; on the contrary, it requires continuous effort to preserve critical debate, pluralism, and freedom of expression within limits that prevent their own destruction. The construction of a more rational and tolerant public space depends on a collective commitment between civil society, democratic institutions, and the technology sector, ensuring that political dialogue is not reduced to an identity struggle but rather to a constant process of exchanging and improving ideas, as Popper argued when emphasizing that democracy is, above all, a system of continuous correction, not an end state to be reached.

References

- Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & Yang, D. C. (2020). Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104254. [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2019). Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media. Research and Politics, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M., Faverio, M., & Park, E. (2024). How teens and parents approach screen time. Pew Research Center.

- Bennett, W. L., & Manheim, J. B. (2006). The one-step flow of communication. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 608(1), 213-232. [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S., & Larsson, A. O. (2023). Engagement with candidate posts on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook during the 2019 election. New Media & Society, 25(1), 119-140. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J., Ahmed, S., Hilbert, M., Liu, B., & Luu, J. (2020). Do search algorithms endanger democracy? An experimental investigation of algorithm effects on political polarization. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64(2), 150-172. [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9). [CrossRef]

- Davis, B., Goodliffe, J., & Hawkins, K. (2024). The two-way effects of populism on affective polarization. Comparative Political Studies. [CrossRef]

- Dietze, G., & Roth, J. (2020). Right-wing populism and gender: A preliminary cartography of an emergent field of research. In G. Dietze & J. Roth (Eds.), Right-Wing Populism and Gender (1st ed., pp. 7-22). Transcript Verlag. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv371cn93.3.

- Engesser, S., Fawzi, N., & Larsson, A. O. (2017). Populist online communication: Introduction to the special issue. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1279-1292. [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N., & Krämer, B. (2021). The media as part of a detached elite? Exploring anti-media populism among citizens and its relation to political populism. International Journal of Communication, 15. http://ijoc.org.

- Fenoll, V., Gonçalves, I., & Bene, M. (2024). Divisive issues, polarization, and users' reactions on Facebook: Comparing campaigning in Latin America. Politics and Governance, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gidron, N., Adams, J., & Horne, W. (2023). Who dislikes whom? Affective polarization between pairs of parties in Western democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 997-1015. [CrossRef]

- Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances. Available online: http://advances.sciencemag.org/.

- Hameleers, M., & Schmuck, D. (2017). It's us against them: A comparative experiment on the effects of populist messages communicated via social media. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1425-1444. [CrossRef]

- Harteveld, E., Mendoza, P., & Rooduijn, M. (2022). Affective polarization and the populist radical right: Creating the hating? Government and Opposition, 57(4), 703-727. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2024). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science.

- Johnston, C. D., & Wronski, J. (2015). Personality dispositions and political preferences across hard and easy issues. Political Psychology, 36(1), 35-53. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43783833.

- Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: A conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Communication Theory, 24(1), 42-60. [CrossRef]

- Levy, R. (2021). Social media, news consumption, and polarization: Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Review, 111(3), 831-870. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, G. (2008). Populism and the media. In Twenty-First Century Populism (pp. 49-64). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2015). Vox populi or vox masculini? Populism and gender in Northern Europe and South America. Patterns of Prejudice, 49(1-2), 16-36. [CrossRef]

- Postman, N. (1985). Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the age of show business. Viking Penguin.

- Popper, K. (1945). The open society and its enemies. Routledge.

- Reese, S. D., & Shoemaker, P. J. (2016). A media sociology for the networked public sphere: The hierarchy of influences model. Mass Communication and Society, 19(4), 389-410. [CrossRef]

- Settle, J. E. (2018). Frenemies: How social media polarises America. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Stroud, N. J. (2008). Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior, 30(3), 341-366. [CrossRef]

- The Times. (2024). German election: TikTok generation back 'anti-system' parties. Available online: https://www.thetimes.com/world/europe/article/german-election-tiktok-generation-back-anti-system-parties-kmgcrsh06.

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., van Noord, J., Kesberg, R., García-Sánchez, E., Brandt, M. J., Kuppens, T., Easterbrook, M. J., Smets, L., Gorska, P., Marchlewska, M., C Turner-Zwinkels, T. (2023). Affective Polarization and Political Belief Systems: The Role of Political Identity and the Content and Structure of Political Beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Morstatter, F., Carley, K. M., C Liu, H. (2019). Misinformation in social media: Definition, manipulation, and detec-tion. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter, 21(2), 80-90. Available online: https://www.public.asu.edu/~huanliu/papers/Misinformation_LiangWu2019.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).