Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Materials

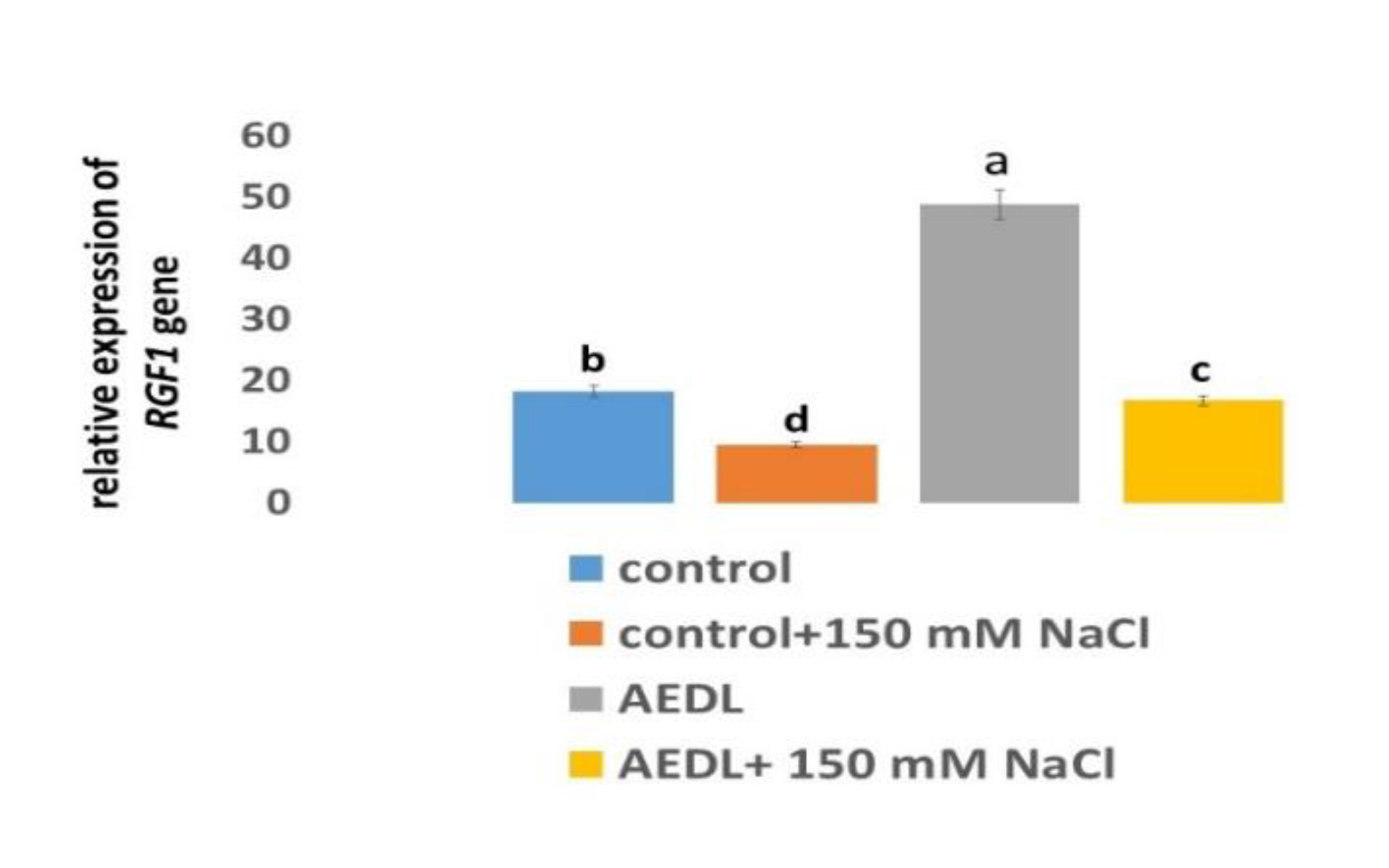

2.2. Expression of RGF1 Gene

2.3. ROS Content

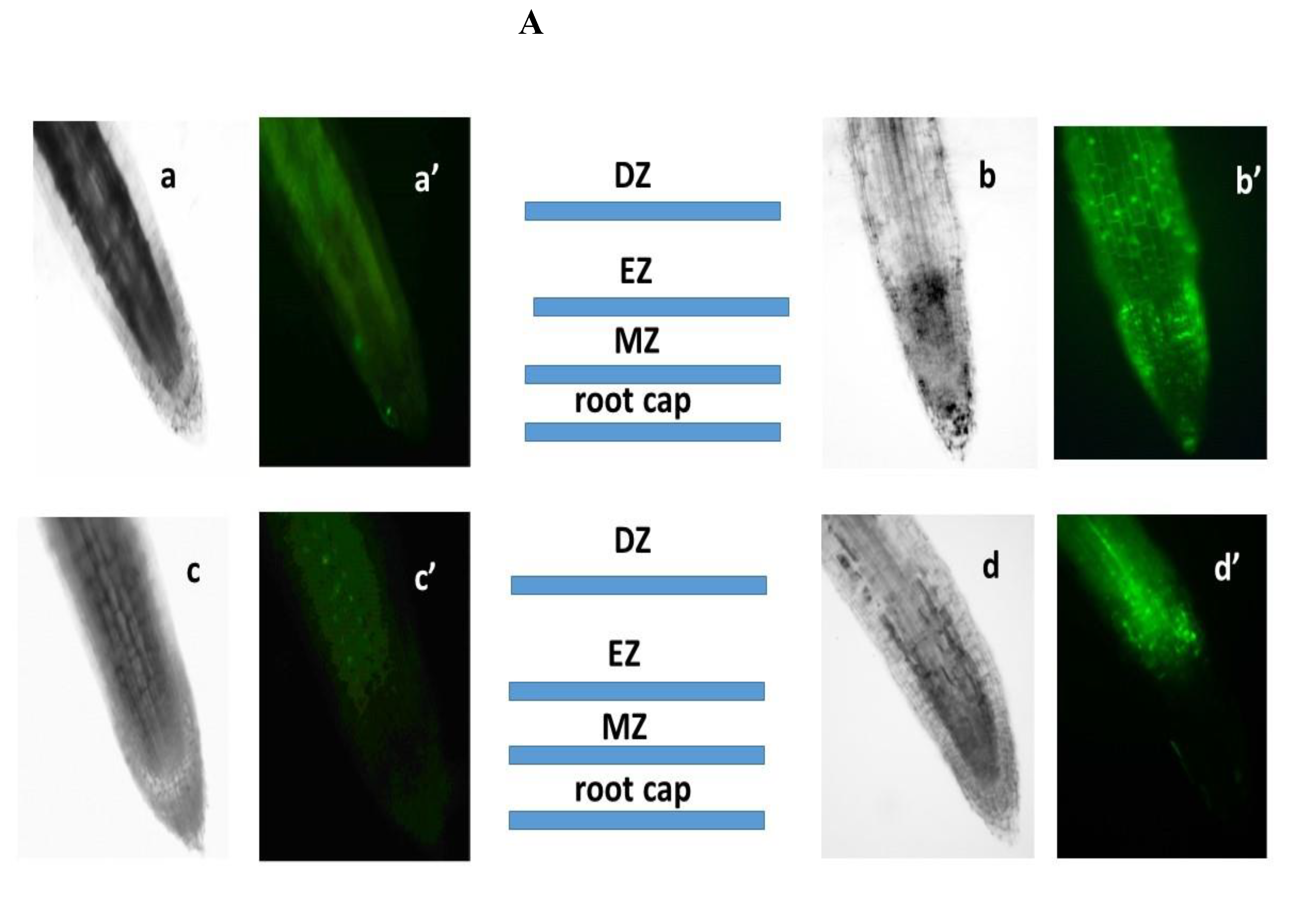

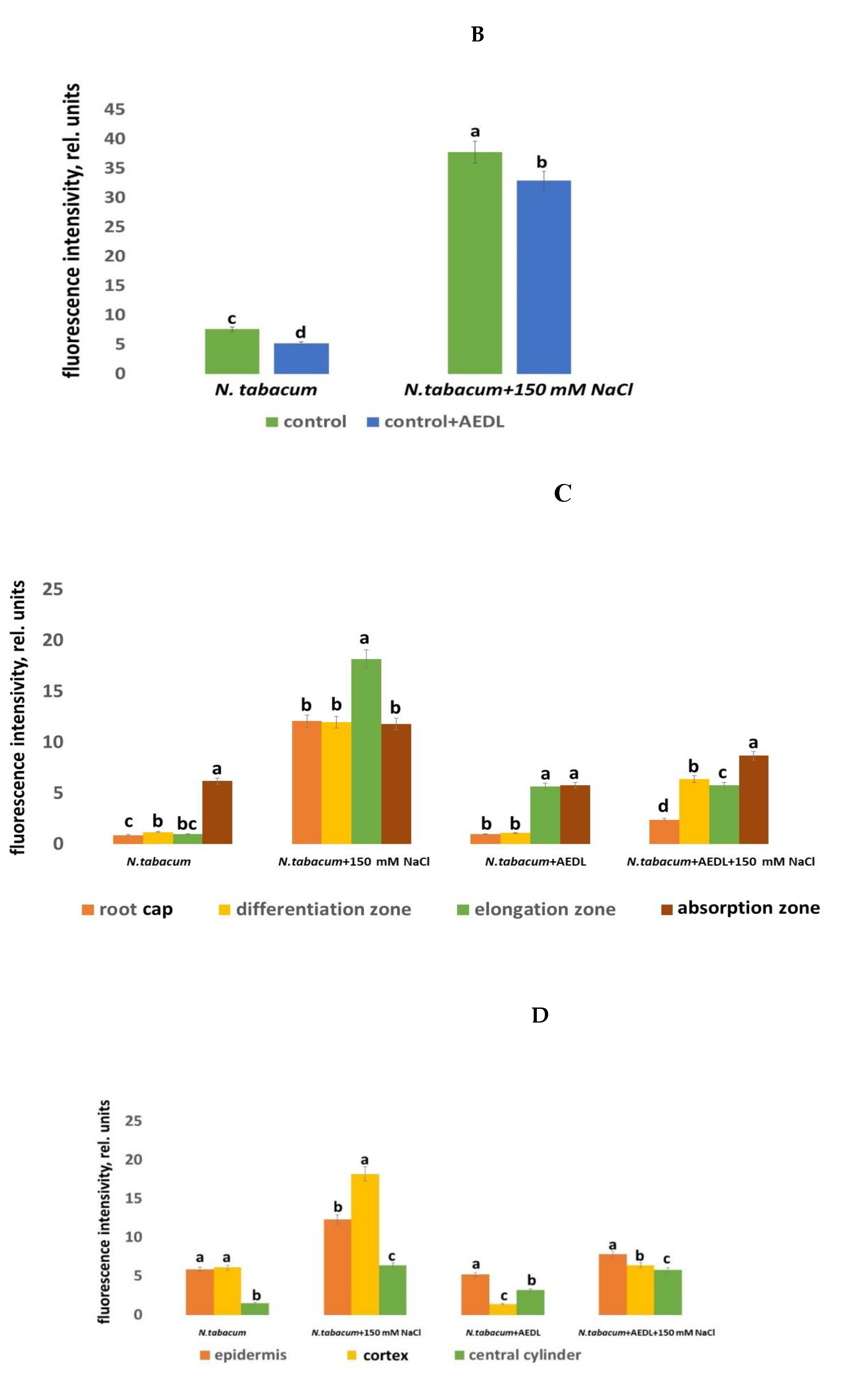

2.3.1. H2O2 content

2.4. Antioxidant Activity

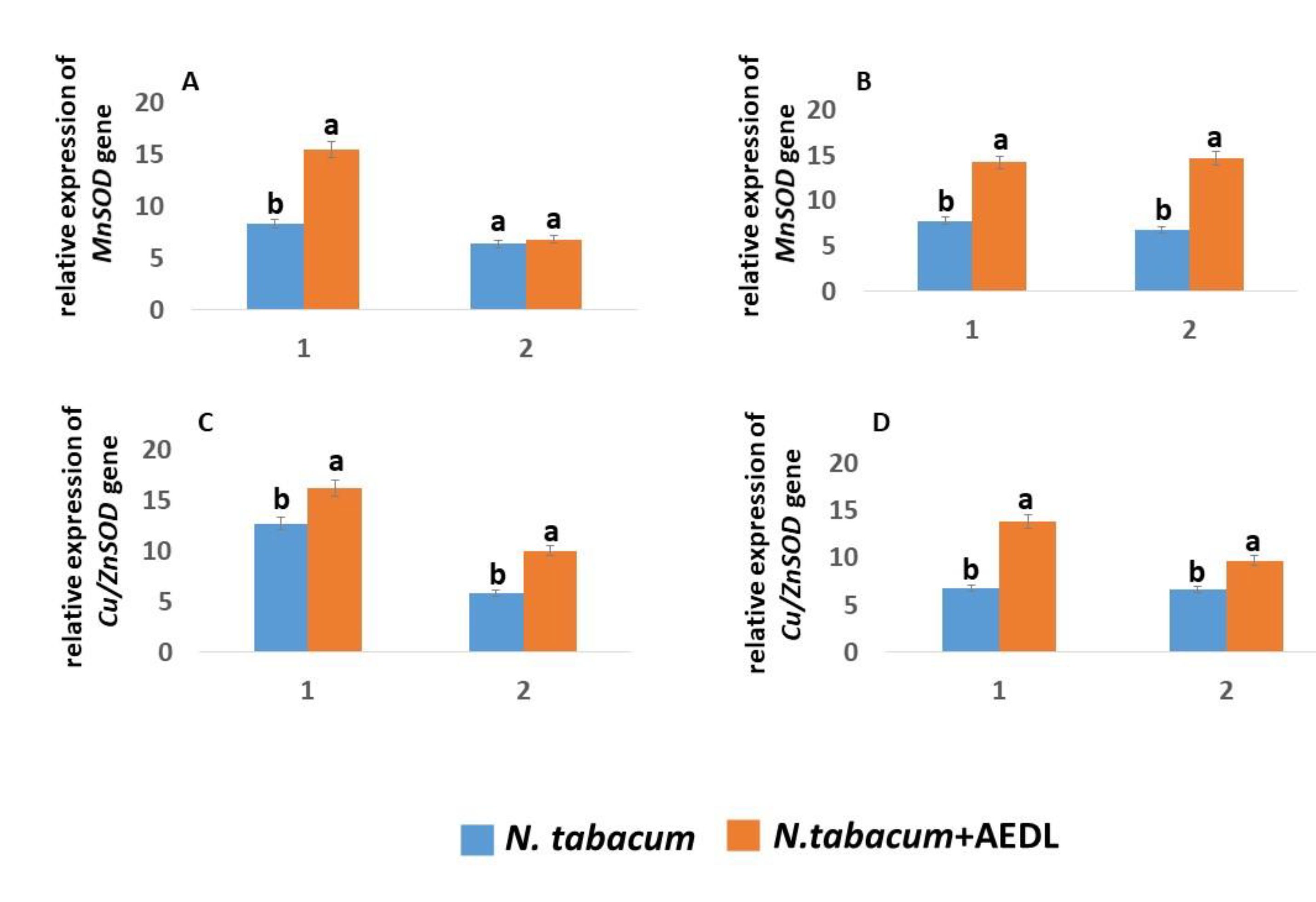

2.4.1. Expression of MnSOD and Сu/ZnSOD Genes

2.4.2. GSH Content

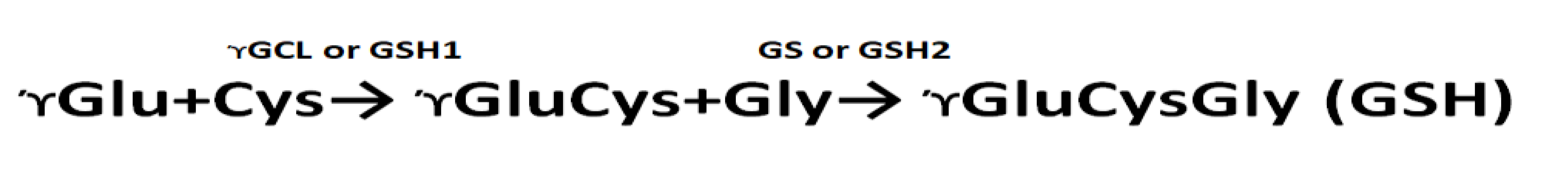

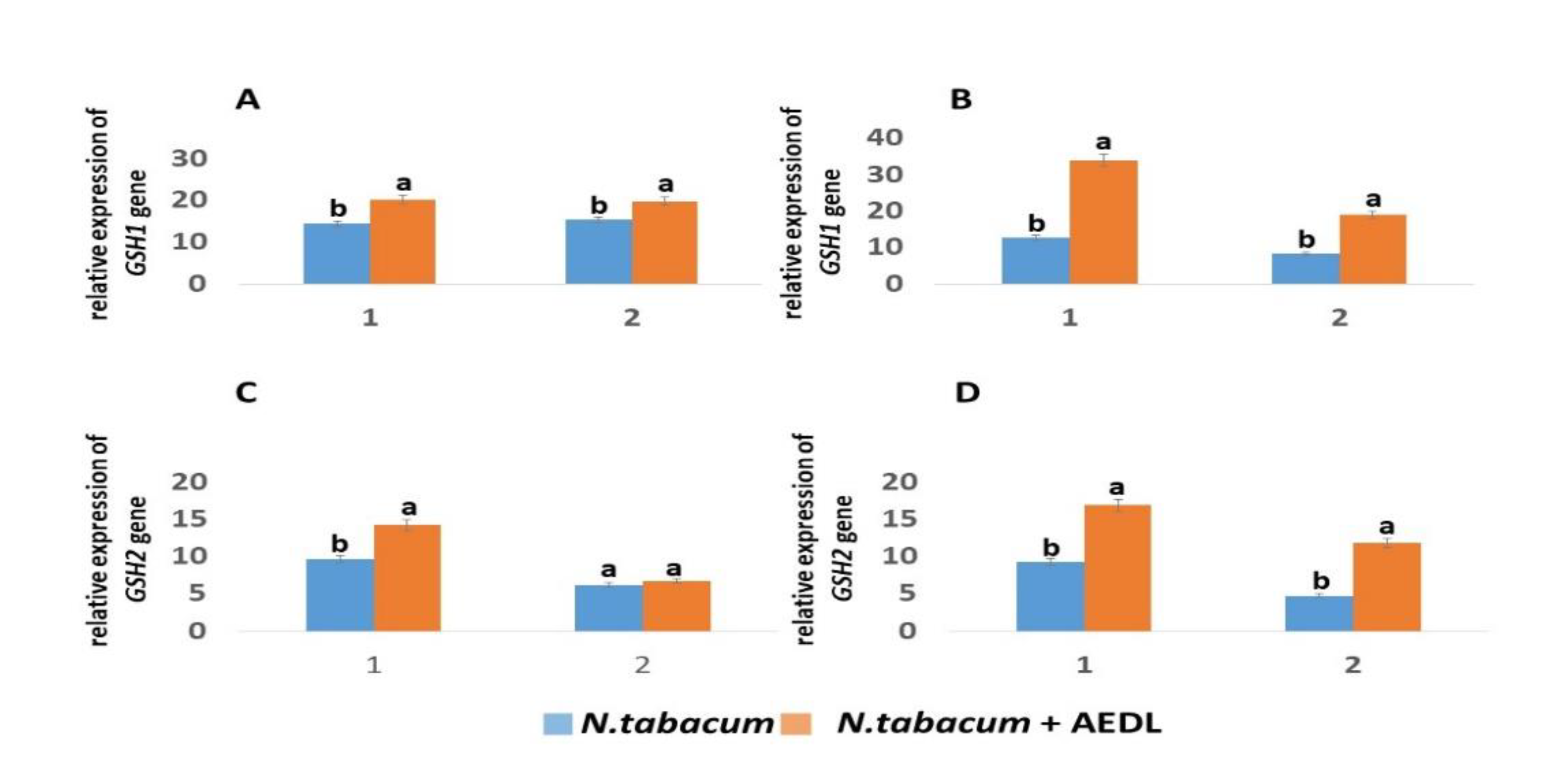

2.4.3. Biosynthesis of GSH, Expression of GSH1 and GSH2 Genes

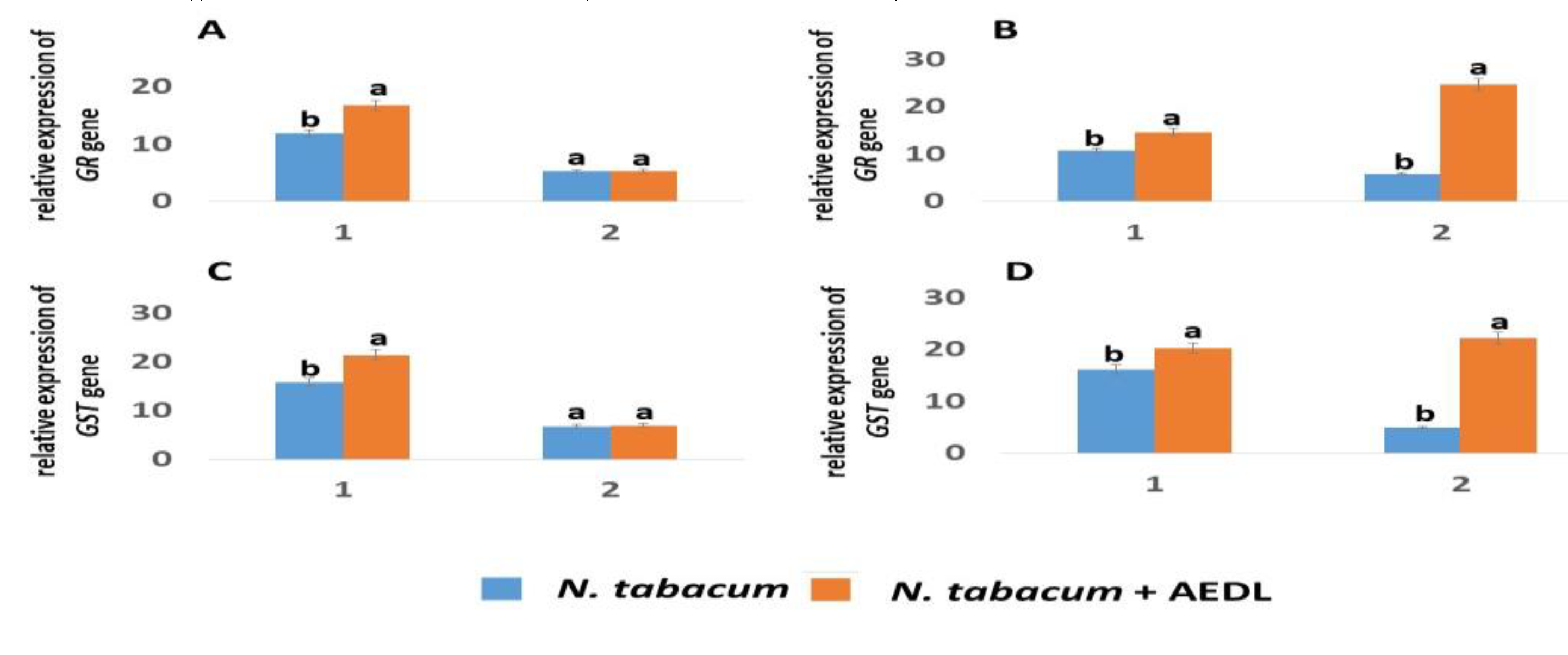

2.4.4. Expression of GR and GST Genes

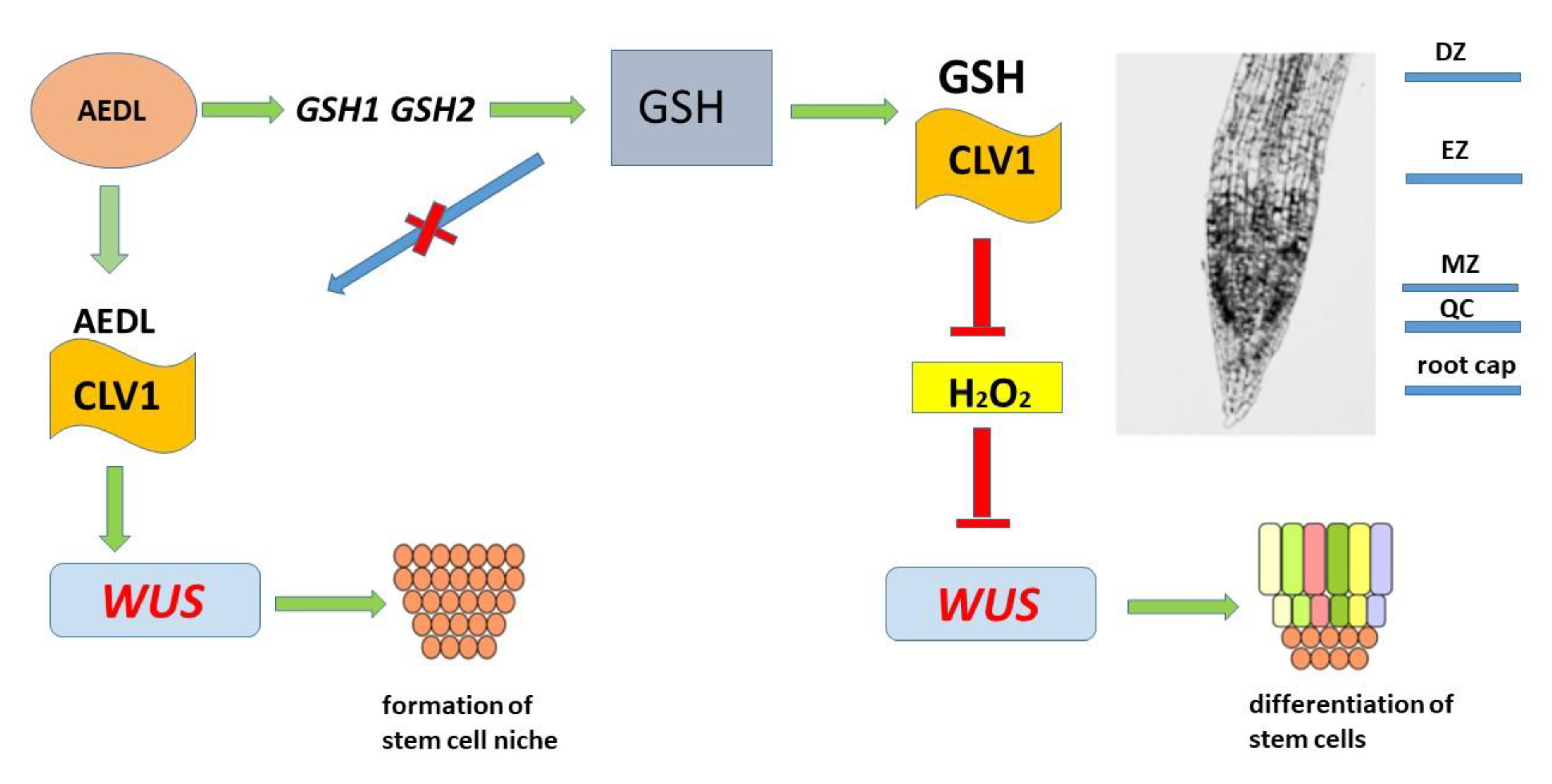

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Fluorescence Microscopy

4.3. Biochemical Analysis

4.4. Total RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

4.5. Statistical Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem., 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, V.; Majeed, U.; Kang, H.; Andrabi, K.I.; John, R. Abiotic stress: Interplay between ROS, hormones and MAPKs. Environ. Exp. Bot., 2017, 137, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, M.M.; Talukder, M.Z.A.; Hossain, M.G.; Uddin, M.S.; Amiruzzaman, M.; Biswas, A.; Ahsan, A.F.M.S.; Chowdhury, M.A.Z. Saline sensitivity leads to oxidative stress and increases the antioxidants in presence of proline and betaine in maize (Zea mays L. ) inbred. Plant Omics. J., 2016, 9, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor, G.; Reichheld, J.-P.; Foyer, C.H. ROS-related redox regulation and signaling in plants. Stem Cell Dev. Biol., 2018, 80, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; van Aken, O.; Schwarzländer, M.; Belt, K.; Millar, A.H. The roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cellular signaling and stress response in plants. Plant Physiol., 2016, 171, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidchik, V. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in plants: From classical chemistry to cell biology. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 109, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, L. A. ROS and RNS in plant physiology: an overview. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015, 66, 2827–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorion, S.; Ouellet, J.C.; Rivoal, J. Glutathione metabolism in plants under stress: beyond reactive oxygen species detoxification. Metabolites, 11.

- Navrot, N.; Finnie, C.; Svensson, B.; Hägglund, P. Plant redox proteomics. J Proteomics, 2011, 12, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Ou, S.; Lu, Q. ; Zhong, Differential responses of antioxidative system to chilling and drought in four rice cultivars differing in sensitivity, Plant Physiol. Biochem., 2006, 44, 828-836. , 44.

- Noctor, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Chaouch, S.; Jenni, Han Y. ; Neukermans, J.; Marquez –Garcia B.; Foyer C.H. Glutathione in plants: an integrated overview. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2012, 35, 454–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, N.G.; Pasternak, M.; Wachter, A.; Cobbett, C.S.; Meyer, A.J. Maturation of Arabidopsis seeds is dependent on glutathione biosynthesis within the embryo. Plant Physiology, 2006, 141, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechmann, B.; Mauch, F.; Sticher, L.; Müller, M. Subcellular immunocytochemical analysis detects the highest concentrations of glutathione in mitochondria and not in plastids. Journal of Experimental Botany, 4017. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Vivancos, P.; Wolff, T.; Markovic, J.; Pallard, O.F.V.; Foyer, C.H. A nuclear glutathione cycle within the cell cycle. Biochemical Journal, 2010, 431, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noctor, G.; Arisi, A.; Jouanin, L.; Kunert, K.; Rennenberg, H.; Foyer, C. Glutathione: biosynthesis, metabolism and relationship to stress tolerance explored in transformed plants. J. Exp. Bot., 1998, 49, 623–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouch, S.; Queval, G.; Vanderauwera, S.; Mhamdi, A.; Vandorpe, M.; Langlois-Meurinne, M.; Van Breusegem, F.; Saindrenan, P.; Noctor. G. Peroxisomal hydrogen peroxide is coupled to biotic defense responses by isochorismate synthase 1 in a daylength-related manner. Plant Physiology, 2010, 153, 1692–1705.

- Queval, G.; Thominet, D.; Vanacker, H.; Miginiac-Maslow, M.; Gakière, B.; Noctor, G. H2O2-activated up-regulation of glutathione in Arabidopsis involves induction of genes encoding enzymes involved in cysteine synthesis in the chloroplast. Molecular Plant, 2009, 2, 344–356.

- Mhamdi, A.; Hager, J.; Chaouch, S. Arabidopsis GLUTATHIONE REDUCTASE 1 plays a crucial role in leaf responses to intracellular H2O2 and in ensuring appropriate gene expression through both salicylic acid and jasmonic acid signaling pathways. Plant Physiology, 2010, 153, 1144–1160.

- Zámocky, M.; Furtmüller, P.G.; Obinger, C. Evolution of structure and function of Class I peroxidases. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2010, 500, 45–57.

- Cosio, C.; Dunand, C. Specific functions of individual class III peroxidase genes. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2009, 60, 391–408.

- Ding, S.; Jiang, R.; Lu, Q.; Wen, X.; Lu, C. Glutathione reductase 2 maintains the function of photosystem II in Arabidopsis under excess light. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg, 2016, 6, 665–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Halliwell, B. The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: a proposed role in ascorbic acid metabolism. Planta, 1976, 133, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Schüssele, S.J.; Wang, R.; Gütle, D.D.; Romer, J.; Rodriguez-Franco, M.; Scholz, M.; Buchert, F.; Lüth, V.M.; Kopriva, S.; Dörmann, P.; Schwarzländer, M.; Reski, R.; Hippler, M.; Meyer, A.J. Chloroplasts require glutathione reductase to balance reactive oxygen species and maintain efficient photosynthesis. Plant J., 2020, 103, 1140–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty, L.; Bausewein, D.; Müller, C.; Bangash, S.A.K.; Moseler, A.; Schwarzländer, M.; Müller-Schüssele, S.J.; Zechmann, B.; Riondet, C.; Balk, J.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R.; Reichheld, J.-P.; Meyer, A.J. Arabidopsis glutathione reductase 2 is indispensable in plastids, while mitochondrial glutathione is safeguarded by additional reduction and transport systems. New Phytol., 2019, 224, 1569–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataya, A.M.R.; Reumann, S. Arabidopsis glutathione reductase 1 is dually targeted to peroxisomes and the cytosol. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2010, 5, 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.H.; Lu, Q.T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.P.; Wen, X.G.; Zhang, L.X.; Lu, C.M. Enhanced sensitivity to oxidative stress in transgenic tobacco plants with decreased glutathione reductase activity leads to a decrease in ascorbate pool and ascorbate redox state. Plant Molecular Biology, 2009, 69, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, P.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Effect of salinity stress on plants and its tolerance strategies: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 2015, 22, 4056–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ausz, M.; Sircelj, H.; Grill D. The glutathione system as a stress marker in plant ecophysiology: is a stress-response concept valid? Journal of Experimental Botany, 2004, 55, 1955–1962.

- Ogawa, K. Glutathione-associated regulation of plant growth and stress responses Antioxid Redox Signal, 2005, 7, 973-81.

- Kranner, I.; Birtic, S.; Anderson, K.M.; Pritchard, H.W. Glutathione half-cell reduction potential: a universal stress marker and modulator of programmed cell death. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 2165. [Google Scholar]

- Kranner, I.; Beckett, R.P.; Wornik, S.; Zorn, M.; Pfeifhofer, H.W. Revival of a resurrection plant correlates with its antioxidant status. The Plant Journal,.

- Enyedi, B.; Várnai, P.; Geiszt, M. Redox state of the endoplasmic reticulum is controlled by Ero1L-alpha and intraluminal calcium. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2010, 13, 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Feldman, L. Positioning of the auxin maximum affects the character of cells occupying the root stem cell niche. Plant Signaling and Behavior, 2010, 5, 1–3.

- Dinneny, J.R.; Long, T.A.; Wang, J.Y.; Mace, D.; Pointer, S.; Barron, C.; Brady. S.M.; Schiefelbein, J.; Benfey, P.N. Cell identity mediates the response of Arabidopsis roots to abiotic stress. Science, 2008, 32, 942–945.

- Cazalé, A.C.; Clemens, S. Arabidopsis thaliana expresses a second functional phytochelatin synthase. FEBS Letters, 2001, 507, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobbett, C.; Goldsbrough, P. Phytochelatins and metallothioneins: roles in heavy metal detoxifaction and homeostasis. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2002, 53, 159–182.

- Alfenito, M.R.; Souer, E.; Goodman, C.D.; Buell, R.; Mol, J.; Koes, R.; Walbot, V. Functional complementation of anthocyanin sequestration in the vacuole by widely divergent glutathione S-transferases. Plant Cell, 1998, 10, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, D.P.; Edwards, R. (2010) Glutathione S-transferases. The Arabidopsis Book, 2010, 8, e0131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.P.; Davis, B.G.; Edwards, R. Functional divergence in the glutathione transferase superfamily in plants. Identification of two classes with putative functions in redox homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2002, 277, 30859–30869.

- Queval, G.; Thominet, D.; Vanacker, H.; Miginiac-Maslow, M.; Gakière, B.; Noctor, G. H2O2-activated up-regulation of glutathione in Arabidopsis involves induction of genes encoding enzymes involved in cysteine synthesis in the chloroplast. Molecular Plant, 2009, 2, 344–356.

- Csiszár, J.; Horváth, E.; Bela, K.; Gallé, Á. Glutathione-related enzyme system: Glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione transferases (GSTs) and glutathione reroxidases (GPXs) In: Gupta DK, Palma JM, Corpas FJ, editors. Redox state as a central regulator of plant-cell stress responses. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016, 137–158.

- Wachter, A.; Wolf, S.; Steininger, H.; Bogs, J.; Rausch, T. Differential targeting of GSH1 and GSH2 is achieved by multiple transcription initiation: implications for the compartmentation of glutathione biosynthesis in the Brassicaceae. Plant J., 2005, 41, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Gomez, L.; Vanacker, H.; Foyer, C.H. Interactions between biosynthesis, compartmentation and transport in the control of glutathione homeostasis and signalling. J. Exp. Bot., 2002, 53, 1283–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisy, V.; Poinssot, B.; Owsianowski, L.; Buchala, A.; Glazebrook, J.; Mauch, F. Identification of PAD2 as a γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase highlights the importance of glutathione in disease resistance of Arabidopsis. Plant J., 2007, 49, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creissen, G.; Firmin, J.; Fryer, M.; Kular, B.; Leyland, N.; Reynolds, H.; Pastori, G.; Wellburn, F.; Baker, N.; Wellburn, A.; Mullineaux, P. Elevated glutathione biosynthetic capacity in the chloroplasts of transgenic tobacco paradoxically causes increased oxidative stress. The Plant Cell, 1999, 11, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Werner, B.L.; Christensen, E.M.; Oliver, D.J. The biological functions of glutathione revisited in Arabidopsis transgenic plants with altered glutathione levels. Plant Physiology, 2001, 126, 564–574.

- Liedschulte, V.; Wachter, A.; Zhigang, A.; Rausch, T. Exploiting plants for glutathione (GSH) production: uncoupling GSH synthesis from cellular controls results in unprecedented GSH accumulation. Journal of Plant Biotechnology, 2010, 8, 807–820.

- Rennenberg, H.; Herschbach, C.; Haberer, K.; Kopriva, S. Sulfur metabolism in plants: are trees different? Plant Biol. (Stuttg.), 2007, 9, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höller, K.; Király, L.; Künstler, A.; Müller, M.; Gullner, G.; Fattinger, M.; Zechmann, B. Enhanced glutathione metabolism is correlated with sulfur-induced resistance in tobacco mosiac virus-infected genetically susceptible Nicotiana tabacum plants. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 1459. [Google Scholar]

- Bick, J.A.; Setterdahl, A.T.; Knaff, D.B.; Chen, Y.; Pitcher, L.H.; Zilinskas, B.A.; Leustek, T. Regulation of the plant-type 5′-adenylyl sulfate reductase by oxidative stress. Biochemistry, 9040. [Google Scholar]

- Fedoreyeva, L.I. Molecular Mechanisms of Regulation of Root Development by Plant Peptides. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M. Peptides as triggers of plant defence. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5269–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruta, M.; Sabat, G.; Stecker, K.; Minkoff, B.B. , Sussman, M.R. A peptide hormone and its receptor protein kinase regulate plant cell expansion. Science 2014, 343, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grienenberger, E.; Fletcher, J.C. Polypeptide signaling molecules in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 23, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiers, M.; Golemiec, E; van der Schors, R. ; van der Geest, L.; Li, K. W.; Stiekema, W. J.; Liu C.-M. The CLAVATA3/ESR motif of CLAVATA3 is functionally independent from the nonconserved flanking sequences. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, J.; Denay, G.; Wink, R.; Gustavo Pinto, K.; Stahl, Y.; Schmid, J.; Blümke, P.; Simon, R. G.W. Control of Arabidopsis shoot stem cell homeostasis by two antagonistic CLE peptide signalling pathways eLife. 2021, 10, e70934.

- Fedoreyeva,L. I.; Baranova, E.N.;Chaban, I.A.; Dilovarova, T.A.; Vanyushin,B.F.; Kononenko,N.V. Elongating Effect of the Peptide AEDL on the Root of Nicotiana tabacum under Salinity. Plants (Basel), 2022, 11, 1352–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Poliushkevich, L.O.; Gancheva, M.S.; Dodueva, I.E.; Lutova, L.A. Receptors of CLE peptides in plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 67, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolzblasz, A.; Nardmann, J.; Clerici, E.; Causier, B.; van der Graaff, E.; Chen, J.; Devies, B.; Werr, W.; Laux, N. Stem cell regulation by Arabidopsis WOX genes. Mol Plant. 2016, 9, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol., 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L; Buchanan, B. B.; Feldman, L.J.; Luan, S. CLE-like (CLEL) peptides control the pattern of root growth and lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, R.; Fernandez, A.; Tejos, R.; Pérez, A.C.; Kleine-Vehn, J.; Vanneste, S.; Drozdzecki, A.; Leitner, J.; Abas, L.; Aerts, M.; .Hoogewijs, K.; Baster, P.; De Groodt, R.; Lin, Y.-C.; Storme, V.; Van de Peer, Y.; Beeckman, T.; Madder, A.; Devreese, B; Luschnig, C. ; Friml, J.; Hilson, P. GOLVEN secretory peptides regulate auxin carrier turnover during plant gravitropic responses. Dev Cell 2012, 22, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Drozdzecki, A.; Hoogewijs, K.; Nguyen, A.; Beeckman, T.; Madder, A.; Hilson, A. Transcriptional and functional classification of the GOLVEN/ROOT GROWTH FACTOR/CLE-like signaling peptides reveals their role in lateral root and hair formation. Plant Physiol 2013, 161, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. : Vanderauwera, S.: Suzuki, N.: Miller, G.: Tognett,i V.B.: Vandepoele, K.: Gollery, M.: Shulaev, V.: Van Breusegem, F. ROS signaling: The new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 2011. 16, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H. , Noctor G. Redox signaling in plants. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2087–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: Revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wei, L.; Xu, J.; Zhai, Q.; Jiang, H.; Chen, R.; Chen, Q.; Sun, J.; Chu, J.; Zhu, L. , Liu, C.-M.; Li, C. Arabidopsis Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase acts in the auxin/PLETHORA pathway in regulating postembryonic maintenance of the root stem cell niche. Plant Cell. 2010, 22, 3692–3709. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, T.; Shinohara, H.; Tanaka, M.; Baba, K.; Ogawa-Ohnishi, M.; Matsubayashi, Y. A peptide hormone required for Casparian strip diffusion barrier formation in Arabidopsis roots. Science 2017, 355, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noctor, G.; Strohm, S.; Jouanin, L.; Kunert, K.J.; Foyer, C.H.; Rennenberg, H. Synthesis of glutathione in leaves of transgenic poplar overexpressing γ−glutamylcysteine synthetase. Plant Physiology, 1996, 112, 1071–1078.

- Rennenberg, H.; Herschbach, C.; Haberer, K.; Kopriva, S. Sulfur metabolism in plants: are trees different? Plant Biol. (Stuttg.), 2007, 9, 620–637. 9.

- Herschbach, C.; Rizzini, L.; Mult, S.; Hartmann, T.; Busch, F.; Peuke, A.D.; Kopriva, S.; Ensminger , I. Over-expression of bacterial γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (GSH1) in plastids affects photosynthesis, growth and sulphur metabolism in poplar (Populus tremula × Populus alba) dependent on the resulting γ-glutamylcysteine and glutathione levels. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2009, 33, 1138–1151.

- Ivanova, L.A.; Ronzhina, D.A.; Ivanov, L.A.; Stroukova, L.V.; Peuke, A.D.; Rennenberg, H. Overexpression of gsh1 in the cytosol affects the photosynthetic apparatus and improves the performance of transgenic poplars on contaminated soil. Plant Biology, 2011, 13, 649–659.

- Zeng, J.; Dong, Z.; Wu, H.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z. Redox regulation of plant stem cell fate EMBO J. , 2017, 36, 2844–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Adesanwo, J.K.; Makinde, O.O.; Obafemi, C.A. Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of methanol extract and betulinic acid isolated from the roots of Tetracera potatoria. J. of Pharmacy Research, 2013, 6, 903 907.

- Zalutskaya, Zh.M.; Skryabina, U.S.; Ermilova, E. V. Hydrogen peroxide generation and transcription regulation of antioxidant enzyme expression Chlamydomonas reinbardtii under hypothermia. Plant Physiology (Rus), 2019, 66, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, G. L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 1959, 82, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Varieties growth condition H2O2 mkg/g | |||||||

| N.tabacum control | 12.1±0.60 с | ||||||

| root | +AEDL | 8.93±0.45 d | |||||

| +NaCl | 17.8±0.89 a | ||||||

| +AEDL+NACL | 16.1±0.80 b | ||||||

| N.tabacum | control | 2.72±0.14 c | |||||

| shoot | +AEDL | 2.51±0.12 d | |||||

| +NaCl | 7.98±0.40 a | ||||||

| +AEDL+NACL | 5.23±0.26 b | ||||||

| Varieties growth condition | AOA | |||||||

| %, inhibitory | ||||||||

| N.tabacum control | 37.91±1.89 b | |||||||

| root | +AEDL | 53.70±2.68 a | ||||||

| +NaCl | 11.90±0.59 c | |||||||

| +AEDL+NACL | 38.10±1.90 b | |||||||

| N.tabacum | control | 23.13±1.16 b | ||||||

| shoot | +AEDL | 28.40±1.42 a | ||||||

| +NaCl | 14.71±0.73 d | |||||||

| +AEDL+NACL | 21.96±1,10 c |

| varieties growth condition GSH, mM/g | |||||||

| N.tabacum control | 0.80±0.04 c | ||||||

| root | +AEDL | 2.59±0.13 a | |||||

| +NaCl | 0.68±0.03 d | ||||||

| +AEDL+NACL | 1.38±0.07 b | ||||||

| N.tabacum | control | 0.28±0.01 b | |||||

| shoot | +AEDL | 0.38±0.,02 a | |||||

| +NaCl | 0.13±0.01 c | ||||||

| +AEDL+NACL | 0.30±0.01 b | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).