1. Introduction

Converting between electromagnetically induced absorption (EIA) and electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) allows the sign of the dispersion slope to be manipulated, which provides exceptional control over the properties of the medium in a coherent manner. However, many studies on how the polarizations [

1,

2,

3,

4] of the probe and coupling beams depend on the conversion between EIT and EIA have not considered the effects of the neighboring transitions (ENT).

The conversion between the EIA and EIT can be controlled in many ways [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Reversing the sign of EIT with respect to the polarization ellipticity for the

transition of

87Rb has been investigated without accounting for ENT [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, the total absorption of the D2 line incorporating the Doppler effect could not be determined [

13]. Gozzini et al. [

1] confirmed that the EIT can be tuned continuously to the EIA by choosing right-handedness of the circular polarization and appropriate propagation direction of the coupling and probe beams.

In addition, a theoretical model for a graphene metastructure featuring switchable properties between EIT and EIA within a three-resonator system has been developed [

10]. Chanu et al. [

14] showed that an N-type formation using two control beams enabled to the conversion from EIT to EIA. Depending on the various polarization combinations, EIT or EIA can be formed such that it is possible to make a convert between EIA and EIT. Moreover, the angle dependence of the polarization axes of the coupling and probe beams on EIA and EIT in

85Rb atoms caused by ENT [

20] (in which EIT or EIA can occur) has been reported. However, the switching mechanism for alkali-metal atoms is still not well known. The ENT in adjacent multi-level systems, combined with a change in the angles between the polarization axes of the coupling and probe beams, is important in the mechanisms that convert between EIT and EIA.

In this study the ENT and angle between the polarization axes of the coupling and probe beams in the transitions of 87Rb are investigated. The critical angle was measured and calculated in cases in which EIT could be converted into EIA. We also found that the ENT can be derived from the critical angles obtained by artificially varying the spacings of the excited states of 87Rb because the conversion between EIA and EIT strongly depends on the ENT. We also found that by adjusting the frequency spacings in the excited state of 87Rb, it becomes possible to predict ENT and the competition between EIT and EIA in alkali-metal atoms including 87Rb atom.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 derives the theoretical calculation for

87Rb.

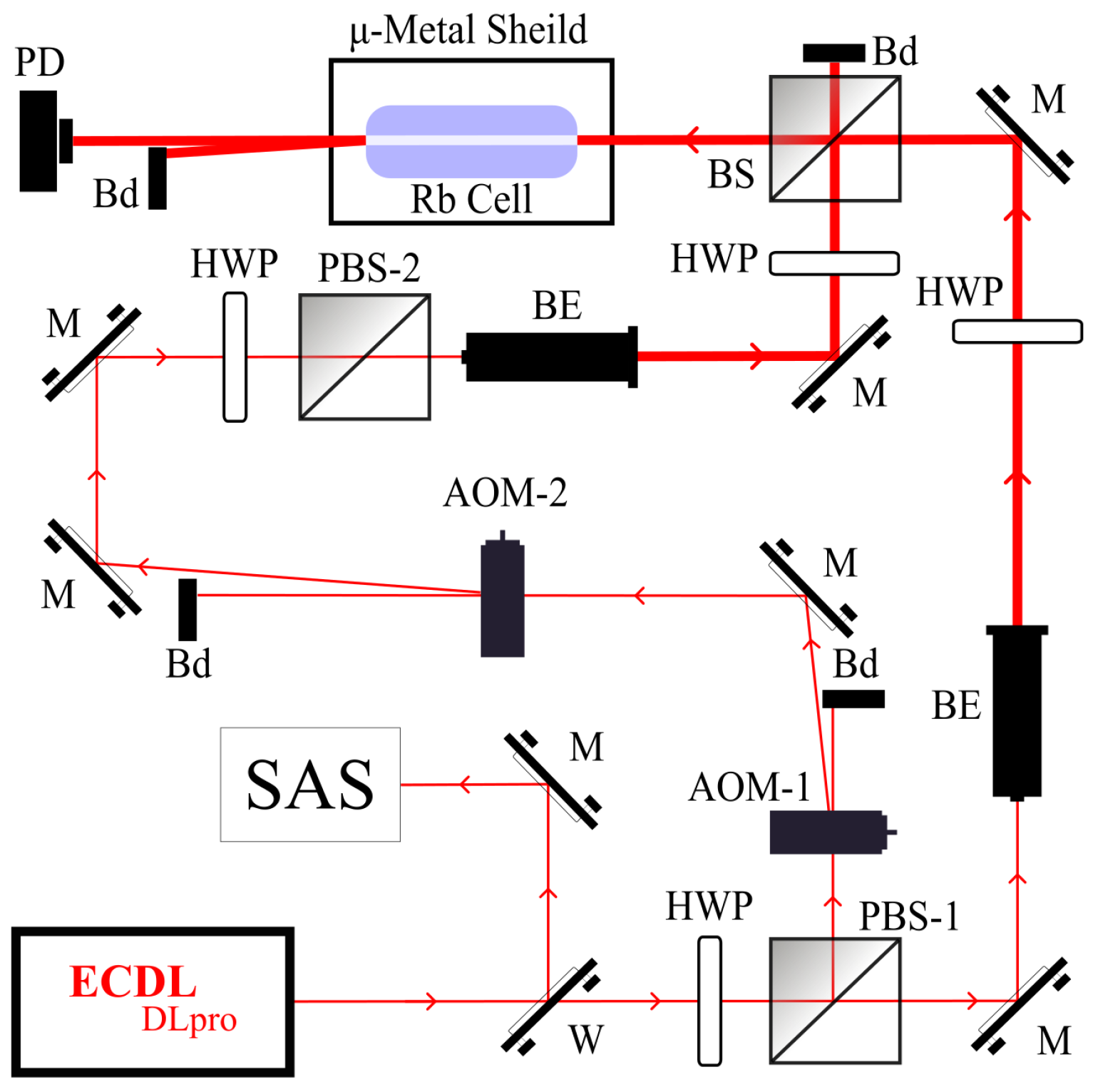

Section 3 describes the experimental setup.

Section 4 presents the experimental and calculated results.

Section 5 discusses the results, and

Section 6 contains the conclusion.

2. Theoretical Calculation

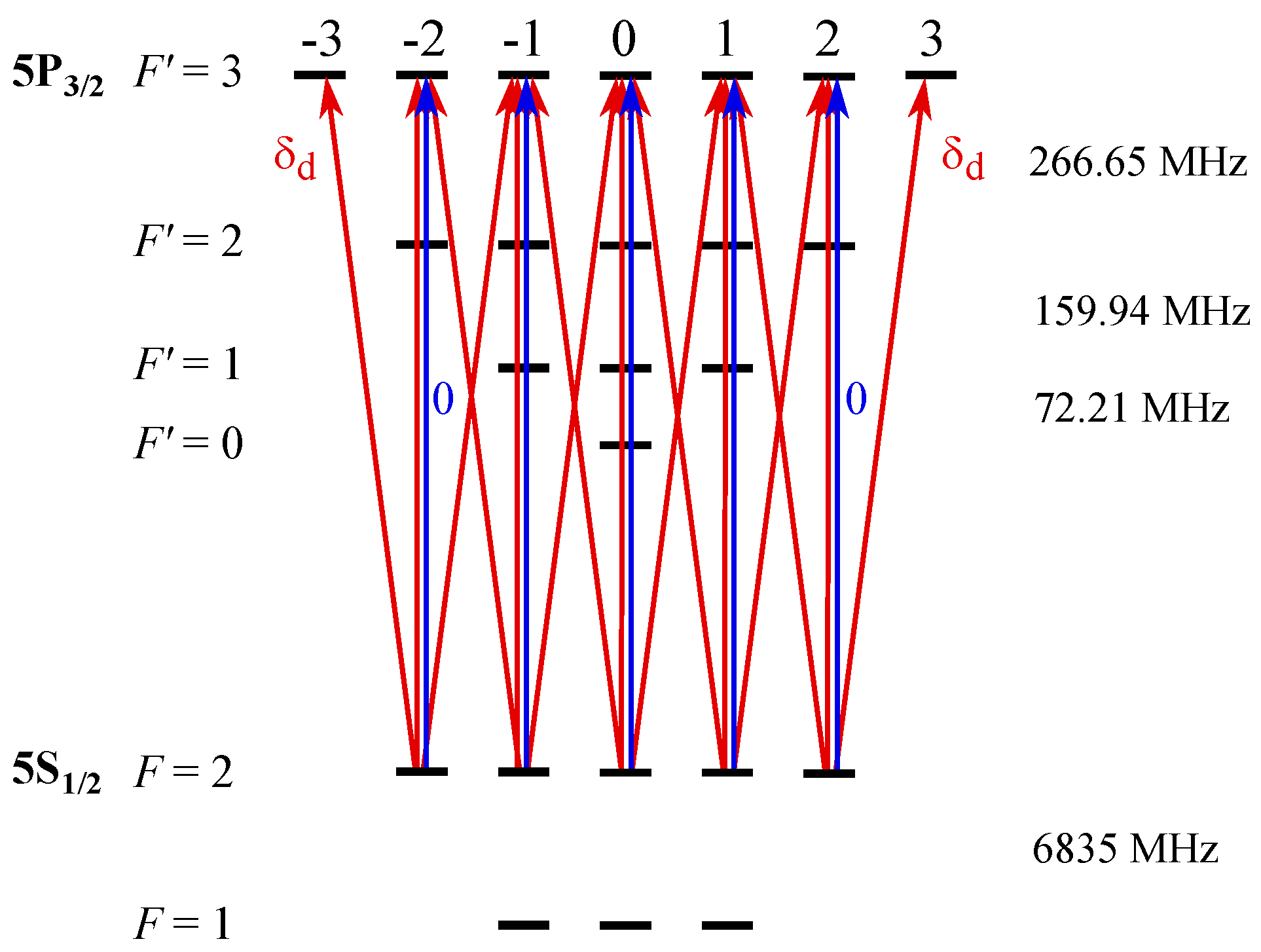

The energy level diagram for

87Rb is shown in

Figure 1, in which the blue (red) arrow and “0” (“

”) represent the transitions excited by the coupling (probe) beam and its relative frequency, respectively (

is defined below). To examine the ENT in the EIA or EIT spectra, we intentionally varied the frequency spacings in the excited state. In this case, the frequency spacings shown in

Figure 1 vary by a common factor defined as the ratio (see

Figure 7 in

Section 5).

Both the coupling and probe beams were linearly polarized, and their polarization axes differed by an angle

. Because the power of the coupling beam was larger than that of the probe beam by a factor of 3.3 in the experiment, we selected the polarization axis of the coupling beam as the quantization axis. Selecting the polarization axis of the probe beam as the quantization axis is also possible, but in this case, we need to use higher interactions than the three photons, normally used in the calculation, can provide to guarantee sufficient accuracy. In the spherical bases, the polarization axes of the coupling and probe beams are given by

and

, respectively, where

Therefore, the coupling beam excited the transitions with

, whereas the probe beam excites the transitions with

and

, as shown in

Figure 1.

The density matrix equation for the

, and 3 transitions of the

87Rb D2 line is given by

where

is the density operator,

is the term associated with the relaxation phenomena [

21]. The Hamiltonian (

H) in Equation (

2) is expressed as

where

,

,

(

) is the detuning of the coupling (probe) beam,

k is the wave vector,

v is the velocity of an atom, and

is the frequency spacing between the states

and

. In Equation (

3),

(

) is the Rabi frequency of the probe (coupling) beam, h.c. represents the Hermitian conjugate, and

is the normalized transition strength between the states

and

[

22].

The density matrix elements should be expanded into several terms that oscillate at different oscillation frequencies. The expansions of the density matrix elements between the excited and ground states, the excited and excited states (and the ground and ground states), and the populations are given by Eqs. (5)–(7) and Eqs. (8) and (9), and Eq. (10) in [

20], respectively

A series of coupled time-dependent differential equations, obtained by inserting the Hamiltonians and expanded density matrix elements into Equation (

2), was solved for the steady-state regime. Then, the final absorption coefficient, averaged over the Maxwell–Boltzmann velocity distribution, is given by

where

is the wavelength of the laser,

is the most probable speed of the atoms, and

is the atomic density in the cell.

is the decomposed matrix element of

oscillating as

. To perform a quantitative analysis of the ENT on the spectra, we performed two types of calculations: degenerate two-level system (DTLS) calculation and degenerate multi-level system (DMLS) calculation. In the DMLS (DTLS) calculation, all neighboring hyperfine states were taken into account (neglected).

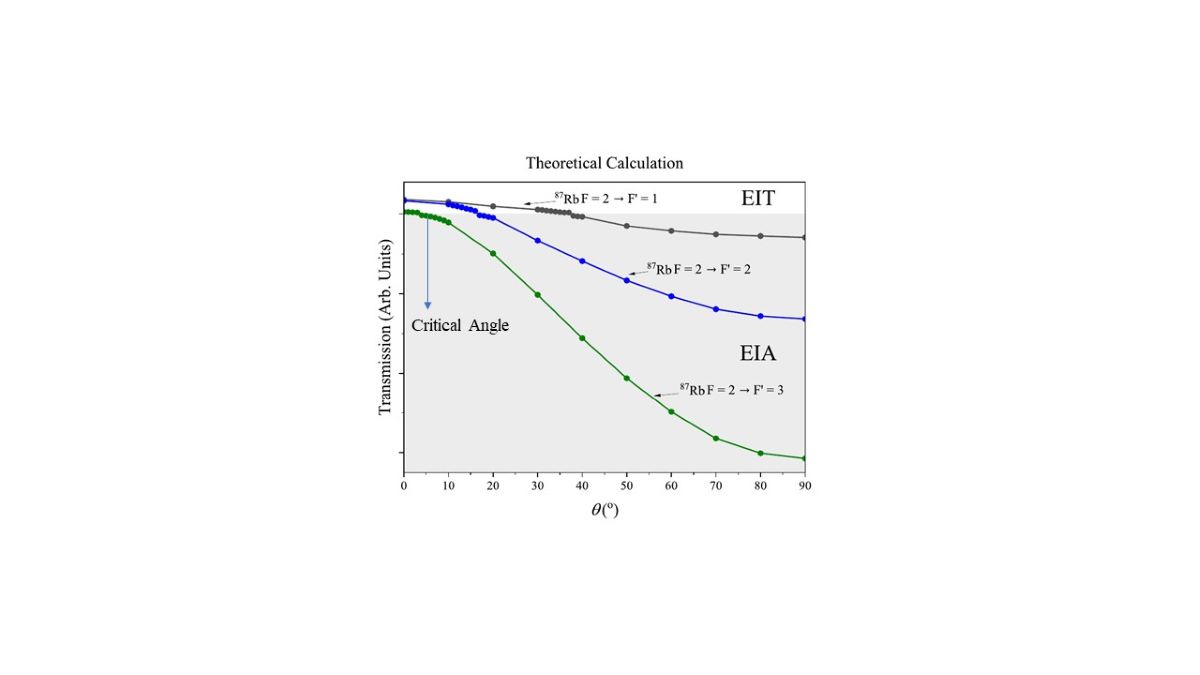

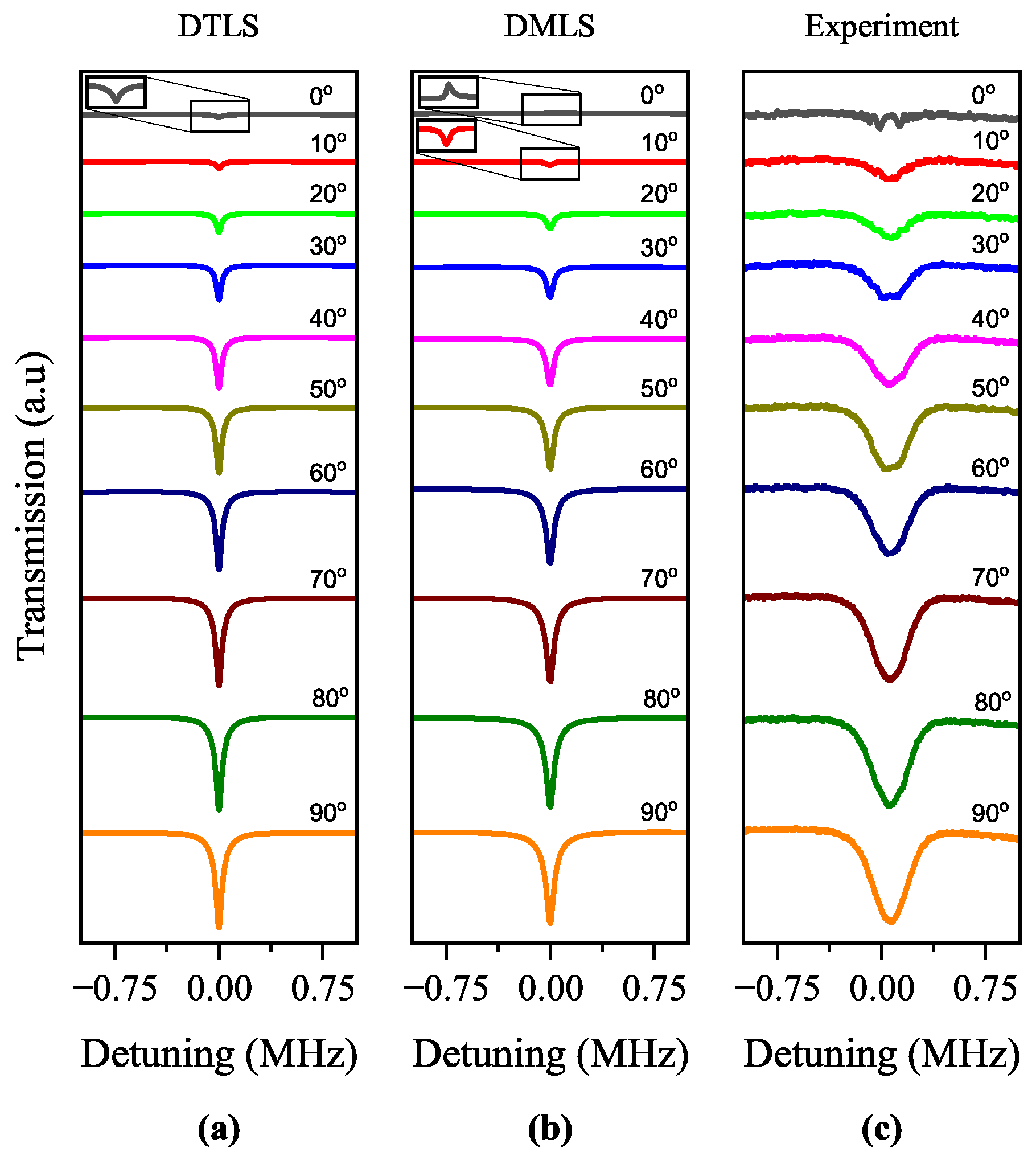

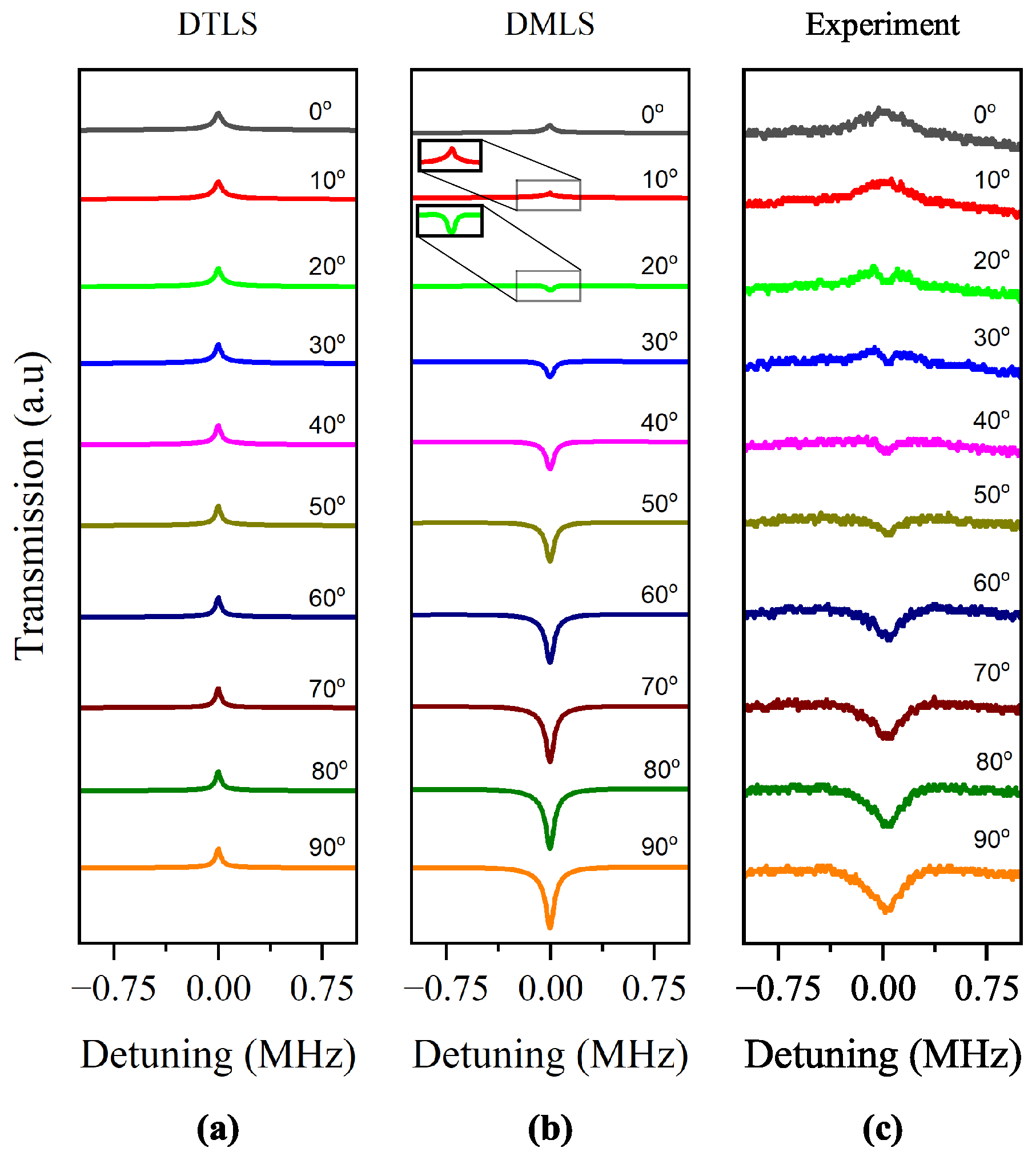

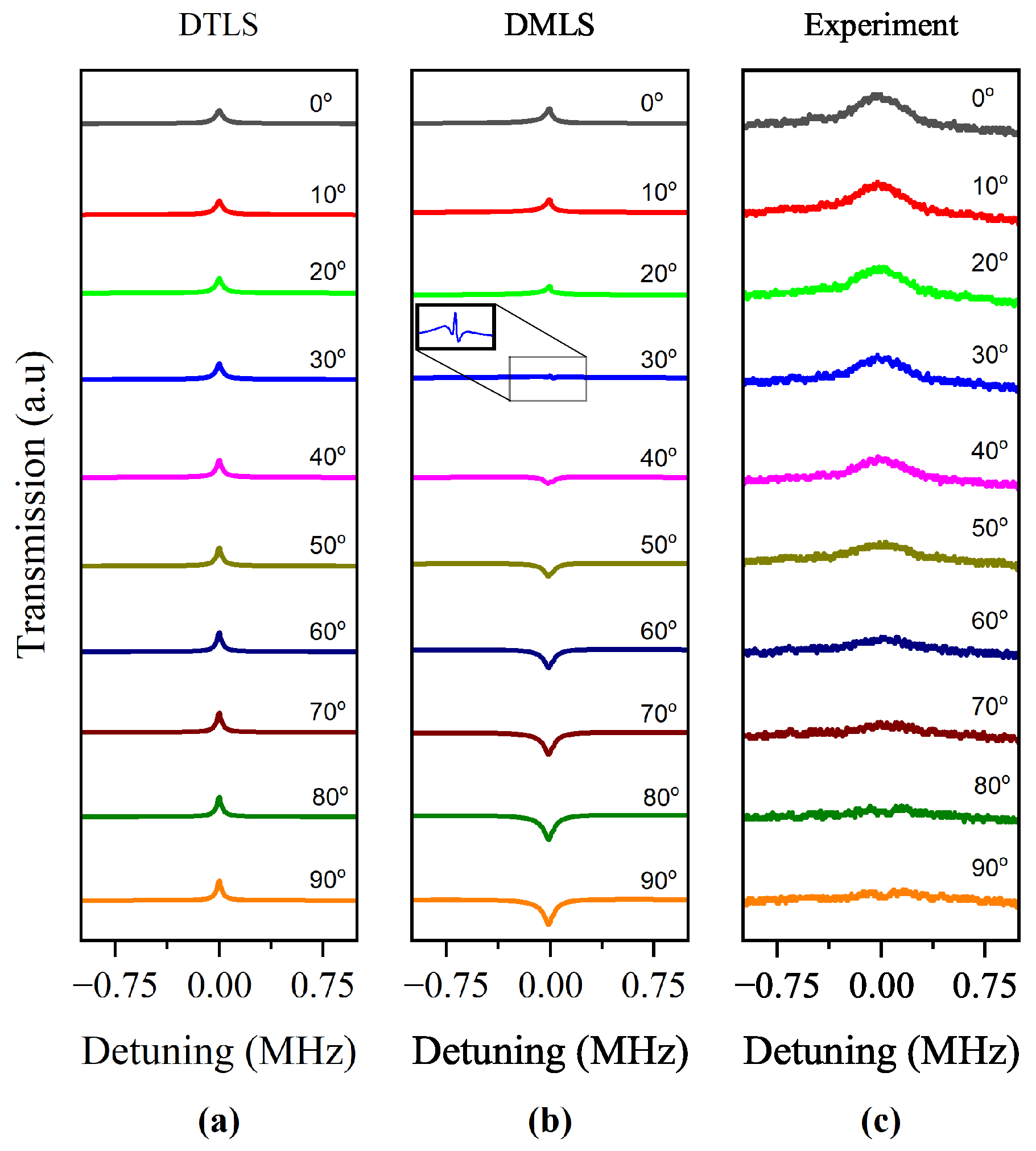

4. Experimental and Calculated Results

The calculated spectra for the DTLS and DMLS and the experimental spectra for the transitions from the upper-ground hyperfine energy level

F = 2 of the D2 line of

87Rb are shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, respectively. The closed

transition exhibited EIT instead of EIA at

. However, the open

and

transitions exhibited EIAs at larger

, as shown in

Figure 3c,

Figure 4c, and

Figure 5c.

The calculated spectra for the DTLS and DMLS and experimental spectra for the closed

= 3 transition are shown in

Figure 3a–c, respectively. Instead of EIA, EIT appeared at

. The EIT switched to EIA at

. After the switch to EIA, the amplitudes of the EIA increased as

increased. The maximum EIA amplitude appeared at

, as shown in

Figure 3c. The experimental spectra were consistent with the calculated spectra for the DMLS, as shown in

Figure 3b, with EIT at

. The influence of the open

= 2 and

= 1 transitions resulted in EIT at

. This was why the calculated spectra for the DTLS that neglected the contributions from neighboring transitions for the closed

= 3 transition had EIAs at all

, as shown in

Figure 3a. The calculated EIA spectra for the DTLS also increased in amplitude as

increased.

For the open

transition, the amplitudes of the EIT increased as

increased for the DTLS calculation with relatively small amplitudes, as shown in

Figure 4a. Because of the dominance of the closed

= 3 transition, the calculated EIT spectra for the DMLS switched to EIA at

, as shown in

Figure 4b. Similarly, the experimental spectra shown in

Figure 4c reflect the conversion of EIT to EIA. After switching, the EIA amplitude increased as

increased, and the maximum amplitude occurred at

. The EIT, in contrast, had a maximum amplitude at

for both calculated spectra for the DMLS and experimental spectra.

For the

transition, the amplitude of the EIT increased as

increased for the calculated spectra for the DTLS, as shown in

Figure 5a. This transition is further away from the

transition because hyperfine splitting was large, which was why the EIT switched to EIA at a larger

compared to the

transition for the calculated spectra for the DMLS shown in

Figure 5b. The EIT switched to EIA at a larger angle, as shown in

Figure 5c, and was not consistent with the DMLS spectra. A plausible reason for this discrepancy is given in

Section 5 using a small variation of the transmission at

.

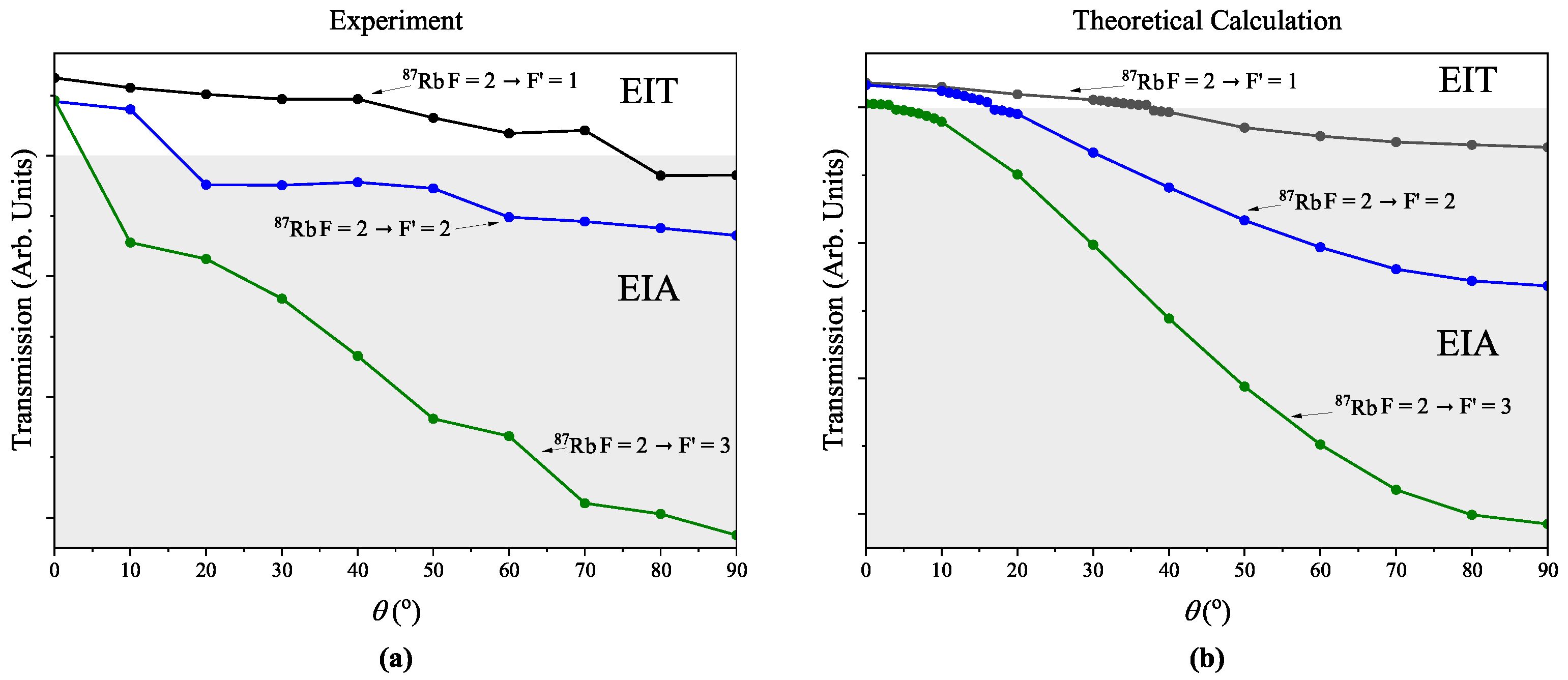

5. Discussion

To accurately determine the critical

, the line-center transmission with respect to the transmission of the broad spectrum was plotted as a function of

. The experimental and calculated results are shown in

Figure 6a,b, respectively. The experimental values of the critical angle for the

, and 1 transitions were measured to be

,

, and

, respectively. To accurately determine the theoretical critical

, a

interval near the critical angle was used instead of a

interval. The calculated values were

,

, and

, respectively. Thus, the experimental and calculated results were in good agreement, except for the

transition. In the experiment, the line-center transmission values gradually increased as

increased, and this trend was also observed in the calculated results. The experimental line-center transmission of the

transition line deviated from the theoretical expectation. This discrepancy can be explained as follows: as is readily seen in

Figure 6b, the variation in the transmission at

for the

transition was very small compared to those for the

transitions. Thus, the critical angle may have been inaccurately determined.

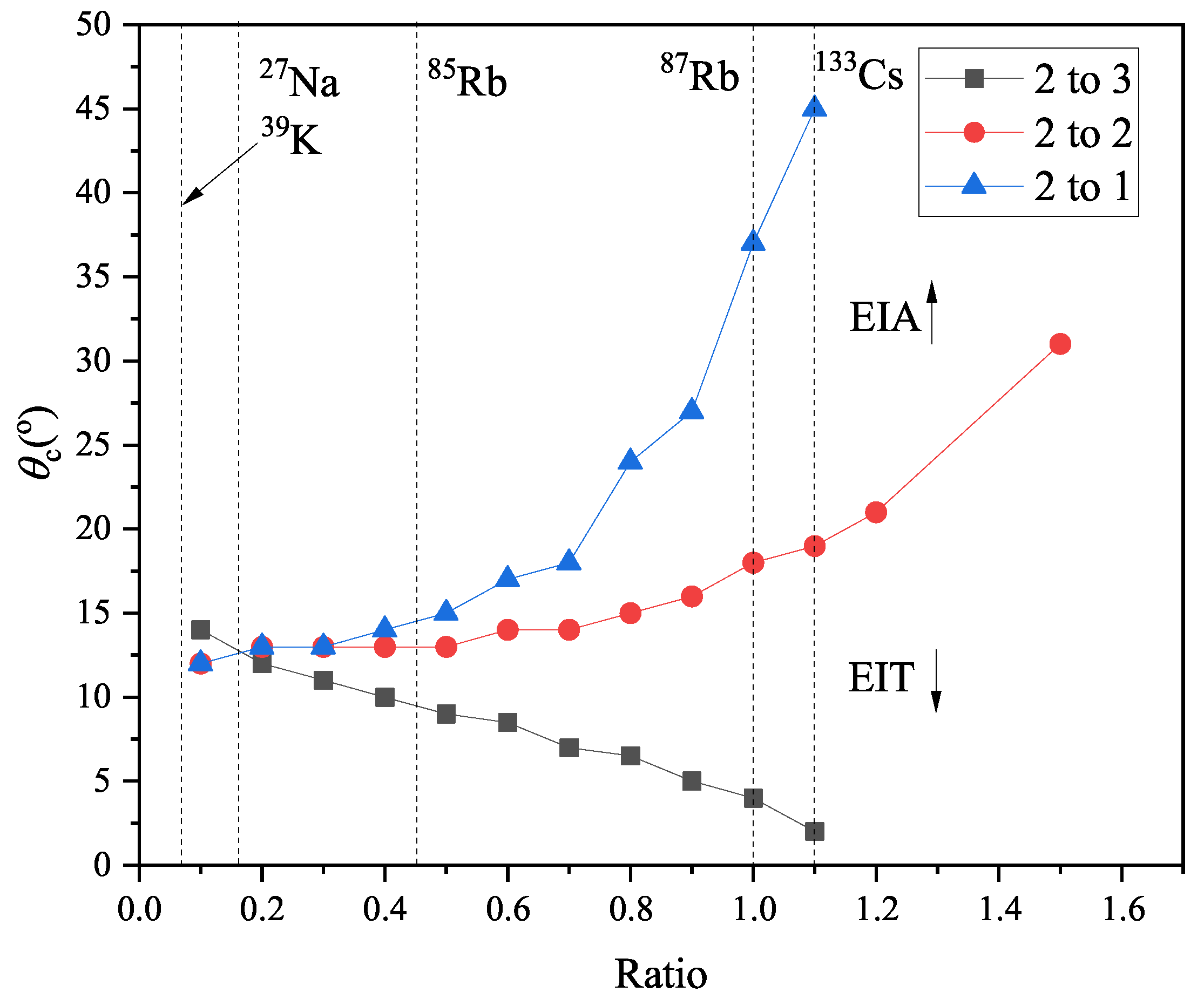

The critical angles

displayed in

Figure 7 show the strength of the ENTs in the EIA and EIT spectra. Compared to the results for

85Rb reported in [

20], the critical angles for the

transitions of

87Rb were larger than those of

85Rb, and vice versa for the

transition. In this work to investigate this phenomenon more systematically, we calculated the critical angles by intentionally varying the frequency spacings in the excited state of

87Rb using a factor called the ratio. For example, if the ratio was unity, the critical angles corresponded to the values for pure

87Rb, as shown in

Figure 7. In contrast, if the ratio was to 0.5, the frequency spacings were reduced to half that of

87Rb. In this case, the neighboring effect increased compared to the case of

87Rb.

Figure 7.

Critical angles () versus the strength of the ENT on the EIA and EIT spectra.

Figure 7.

Critical angles () versus the strength of the ENT on the EIA and EIT spectra.

The calculated results are presented in

Figure 7. The critical angles for the

, and 3 transitions are displayed from top to bottom as a function of the ratio. As the ratio increased, the critical angles for the

transitions (

transition) increased (decreased) monotonically. The calculation of

was not accurate, unlike in typical critical phenomena. This occurred because, when the EIT was converted into the EIA, the introduction of the EIA was gradual rather than radical. However, because our aim was to determine only the overall trend of the transmissions, an inaccurate determination of

did not impact the results of this study.

Because the conversion between the EIA and EIT strongly depends on the ENT rather than the energy level structure, the behavior of other atomic species can be easily predicted by changing the frequency spacings. More accurately, the ENT depends on the frequency spacing divided by the natural linewidth of the transition, which is regarded as the effective frequency spacing. In

Figure 7 the values

are presented as vertical dotted lines. For example, the critical angles for

133Cs were larger (smaller) for the

transitions (

transition) than those for

87Rb. We expect that the conversion between EIA and EIT occurs for other atomic species in a similar way.

For the

transition, as

changed from 0 to

, the strong transitions between the

and

states began to produce the EIA signal. The EIT was converted to the EIA at

. If the ratio was decreased (i.e., the ENT was increased) while

was fixed at

, then the effect of the

transition on the

transition increased, and the signal changed to EIT accordingly. Thus,

increased as the ratio decreased as shown in

Figure 7.

For the and transitions, the conversion from EIT to EIA occurred at a larger value of because of the off-resonant contribution of the strong transition. In this case, as the ratio decreased (i.e. as the ENT increased), the signal changed to EIA owing to the effect of the transition. Thus, decreased as the ratio decreases, in contrast to the case of the transition.

For the transition, only the EIA could be observed when the ratio was larger than approximately 1.2. In this case, the ENT was not sufficient to convert EIA into EIT. When the ratio was very large, which corresponded to the case in which the ENT was absent, only the EIA for the transition and the EIT for the and transitions could be observed. This corresponded exactly to the calculation for the DTLS.

In

Figure 7, the inversion of

can be observed for ratio values smaller than approximately 0.1, (i.e., a larger

was observed for the

transition than the

transitions.) This phenomenon may have resulted from the interplay between the strength of the EIA owing to the transitions between the

and

states and that of the EIT owing to the

transitions when the ENT increased. To examine this phenomenon more quantitatively, we calculated the spectra for the

transition when the ratios were

and

accounting for all the ENT and excluding the effect of the

transition.

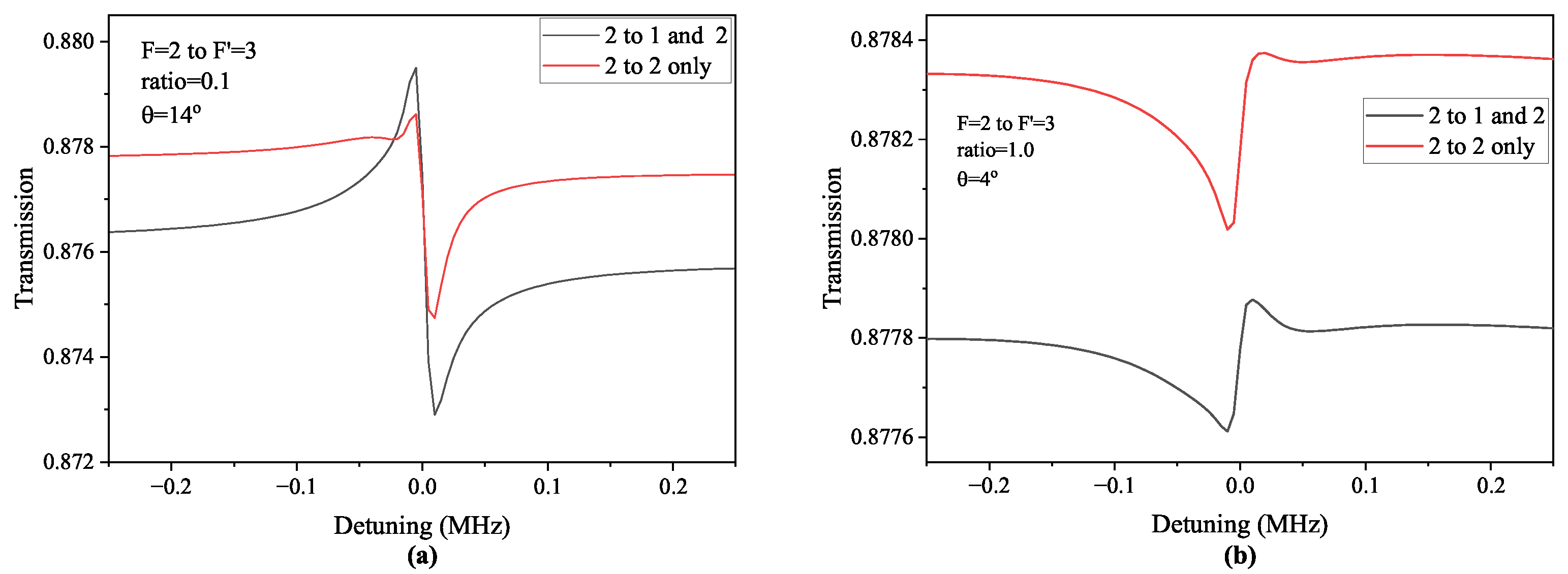

The results for the ratios of

and

at

are shown in

Figure 8a,b, respectively. In

Figure 8, the black curves represent the spectra accounted for all the neighboring transitions and the red curves represent the spectra that considered only the

transition (i.e., neglected the

transition). The angles were

and

, as shown in

Figure 8a,b, respectively. In

Figure 8a, the strengths of the EIT and EIA were comparable for the black curve, and the effect of the EIT was weaker than that of the EIA for the red curve. In contrast, as shown in

Figure 8b, the effect of the

transition was very weak because of the larger hyperfine spacing. Thus, when the ratio was

, the effect of the EIT was enhanced owing to the neighboring transitions associated with the EIT, and a larger

needed to be converted from EIT to EIA. Thus, we could observe larger

for the

transition when the ratio was smaller than approximately

.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the ENT on EIA, EIT, and the conversion between EIA and EIT in 87Rb atoms were investigated in terms of the angle between the polarization axes of the coupling and probe beams. The observed spectral profiles were compared to the calculated absorption profiles by considering the ENT. The results were consistent with the observed spectra for all the transitions. The slight quantitative disagreement for the transition was explained by accounting for the weak variation in the transmission for .

EIT (instead of EIA) occurred at smaller for the upper hyperfine ground state of 87Rb, and the amplitude of the EIA increased as increased for all the and 3 transitions after the transformation from EIT to EIA. The theoretical critical , at which EIT is converted to EIA, was consistent with the experimentally measured critical values except for the transition. Compared to 85Rb, the critical angles for the transitions in 87Rb were greater, whereas for the transition, the critical angles were smaller. We observed an inversion of the critical angle when the ratio was smaller than 0.1, resulting in a larger for the transition compared to the and transitions. This phenomenon was explained by accounting for the competition between the strengths of the EIA and EIT as the ENT varied. The results of this study can deepen our understanding of the ENT on EIA and EIT spectra, and can support useful predictions of the spectra for alkali-metal atoms other than 87Rb atoms.